Submitted:

08 September 2025

Posted:

09 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

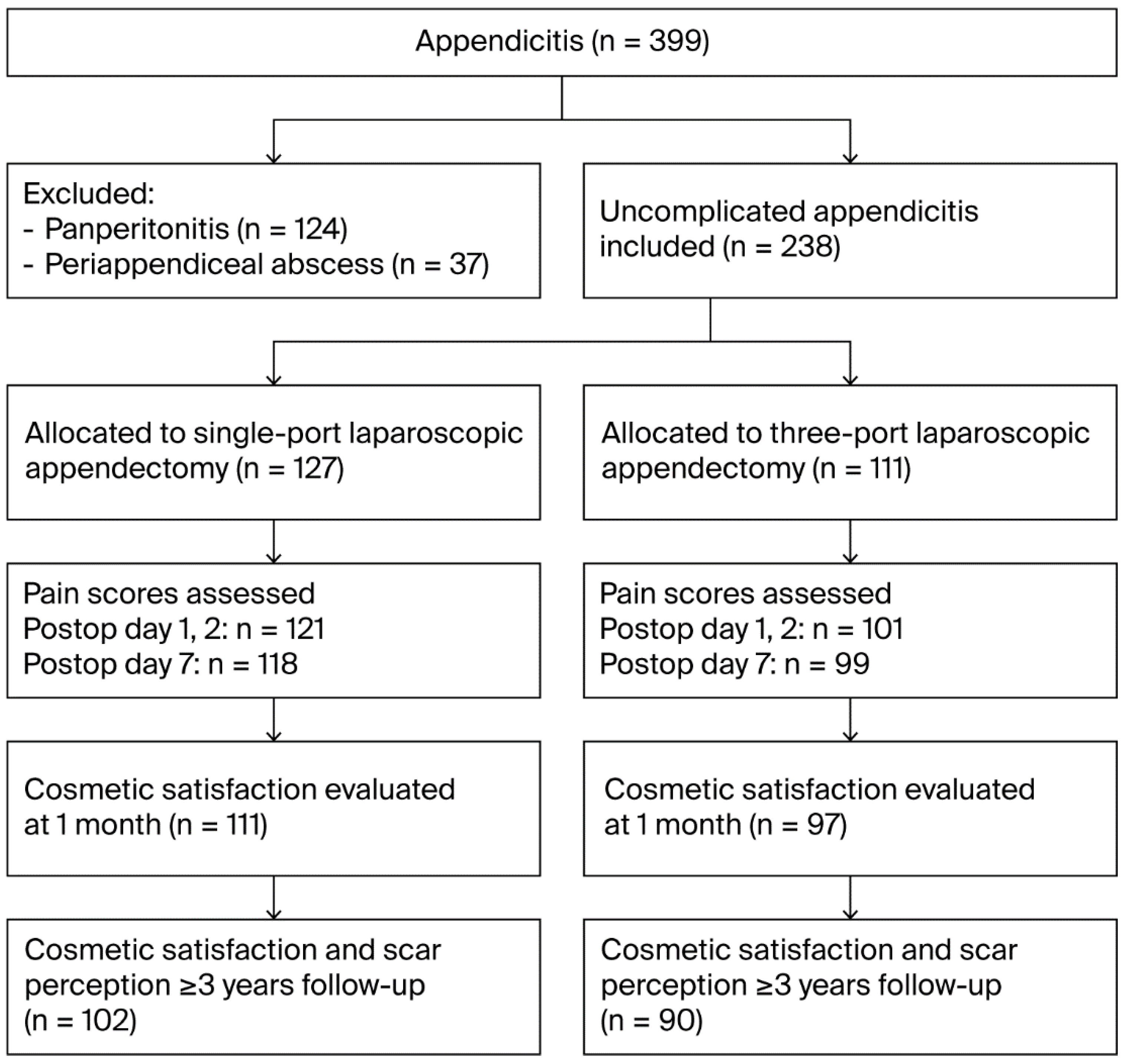

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Surgical Techniques

2.3. Postoperative Care and Follow-Up

2.4. Outcome Measurements

2.5. Sample Size Calculation

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics and Surgical Outcomes

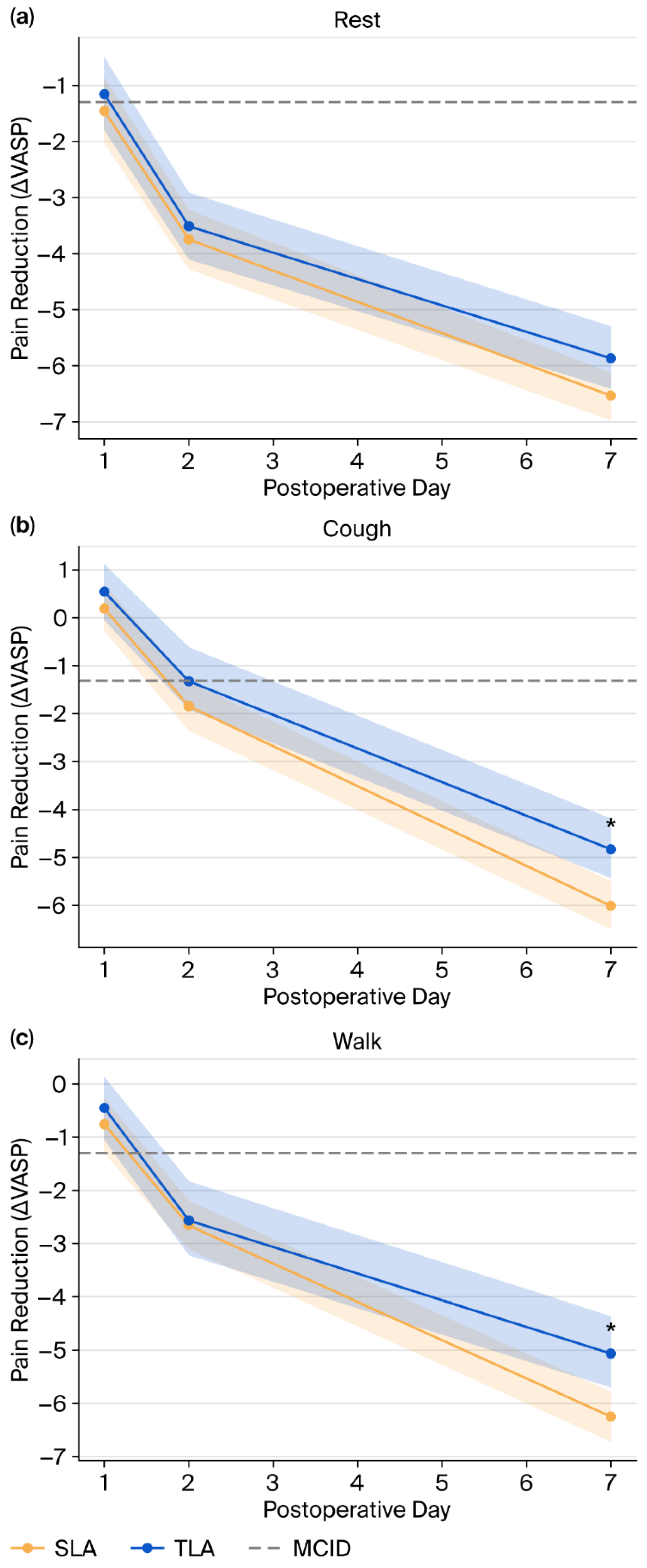

3.2. Pain Outcomes

- deltaPOD7_walk: SLA showed greater pain reduction (−6.46 ± 2.28 vs. −4.80 ± 3.06, MD: −1.66, 95% CI: −2.49 to −0.83, p = 0.000)

- deltaPOD7_cough: SLA demonstrated superior pain reduction (−6.10 ± 2.22 vs. −4.77 ± 3.35, MD: −1.33, 95% CI: −2.20 to −0.46, p = 0.003)

- deltaPOD7_rest: The difference became statistically significant (−6.96 ± 2.30 vs. −5.95 ± 2.73, MD: −1.01, 95% CI: −1.78 to −0.24, p = 0.011)

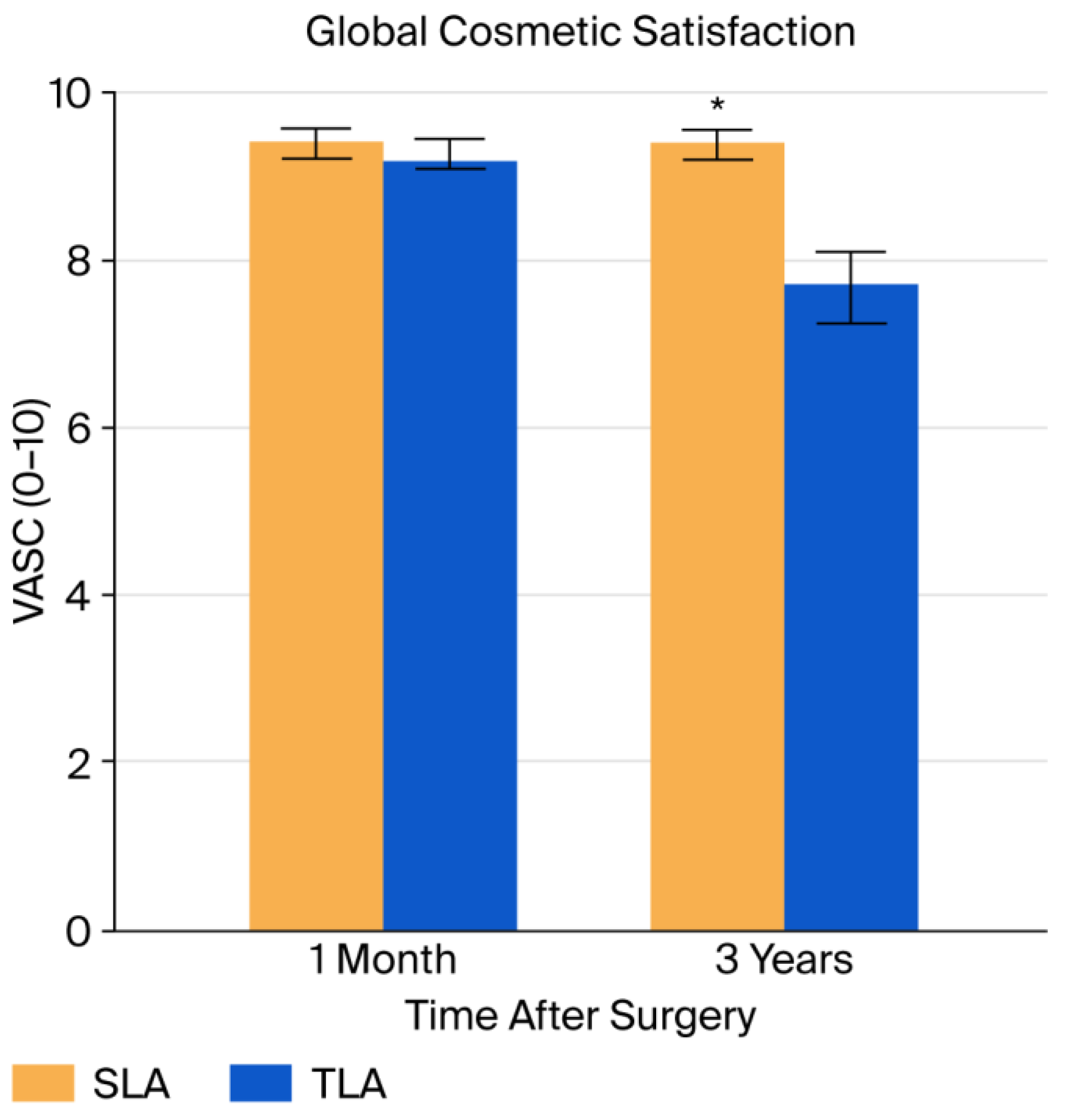

3.3. Cosmetic Satisfaction Outcomes

- One month: A significant difference emerged that was not apparent in the unmatched analysis (9.57 ± 0.82 vs. 9.16 ± 1.12, MD: 0.41, 95% CI: 0.07 to 0.76, p = 0.020)

- Three years: The difference remained highly significant and clinically meaningful (9.56 ± 0.56 vs. 7.71 ± 1.63, MD: 1.84, 95% CI: 1.42 to 2.27, p = 0.000)

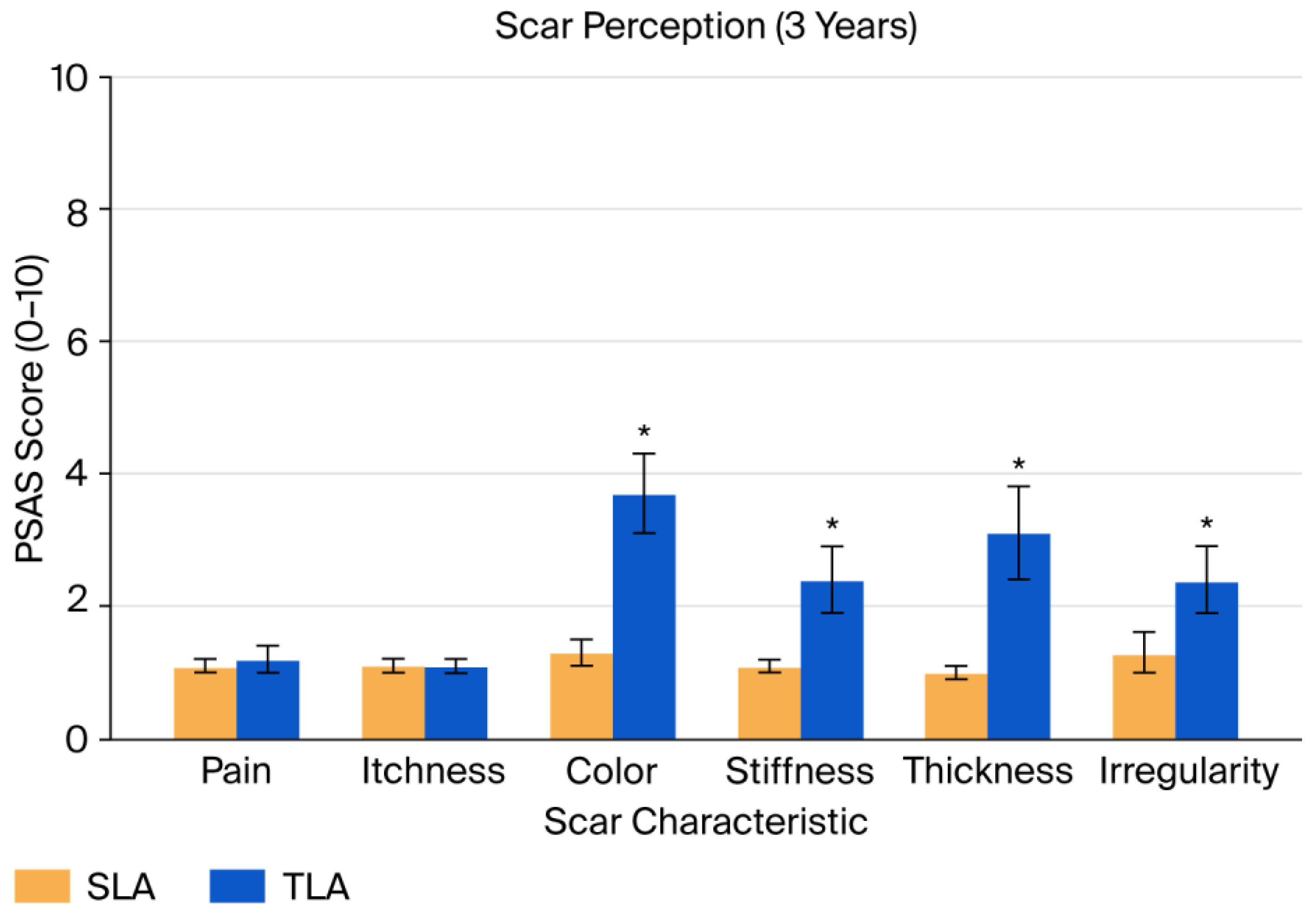

3.4. Scar Perception Outcomes

- Color: 1.28 ± 0.65 vs. 3.67 ± 2.75 (p = 0.000);

- Stiffness: 1.14 ± 0.40 vs. 2.32 ± 2.13 (p = 0.000);

- Thickness: 1.04 ± 0.24 vs. 3.08 ± 2.91 (p = 0.000);

- Irregularity: 1.36 ± 1.15 vs. 2.34 ± 2.33 (p = 0.000).

- Color: Difference of −2.02 (95% CI: −2.56 to −1.47, p = 0.000);

- Stiffness: Difference of −0.89 (95% CI: −1.38 to −0.40, p = 0.001);

- Thickness: Difference of −1.48 (95% CI: −2.07 to −0.88, p = 0.000);

- Irregularity: Difference of −0.86 (95% CI: −1.38 to −0.34, p = 0.002);

- Total PSAS: Difference of −5.11 (95% CI: −6.87 to −3.36, p = 0.000).

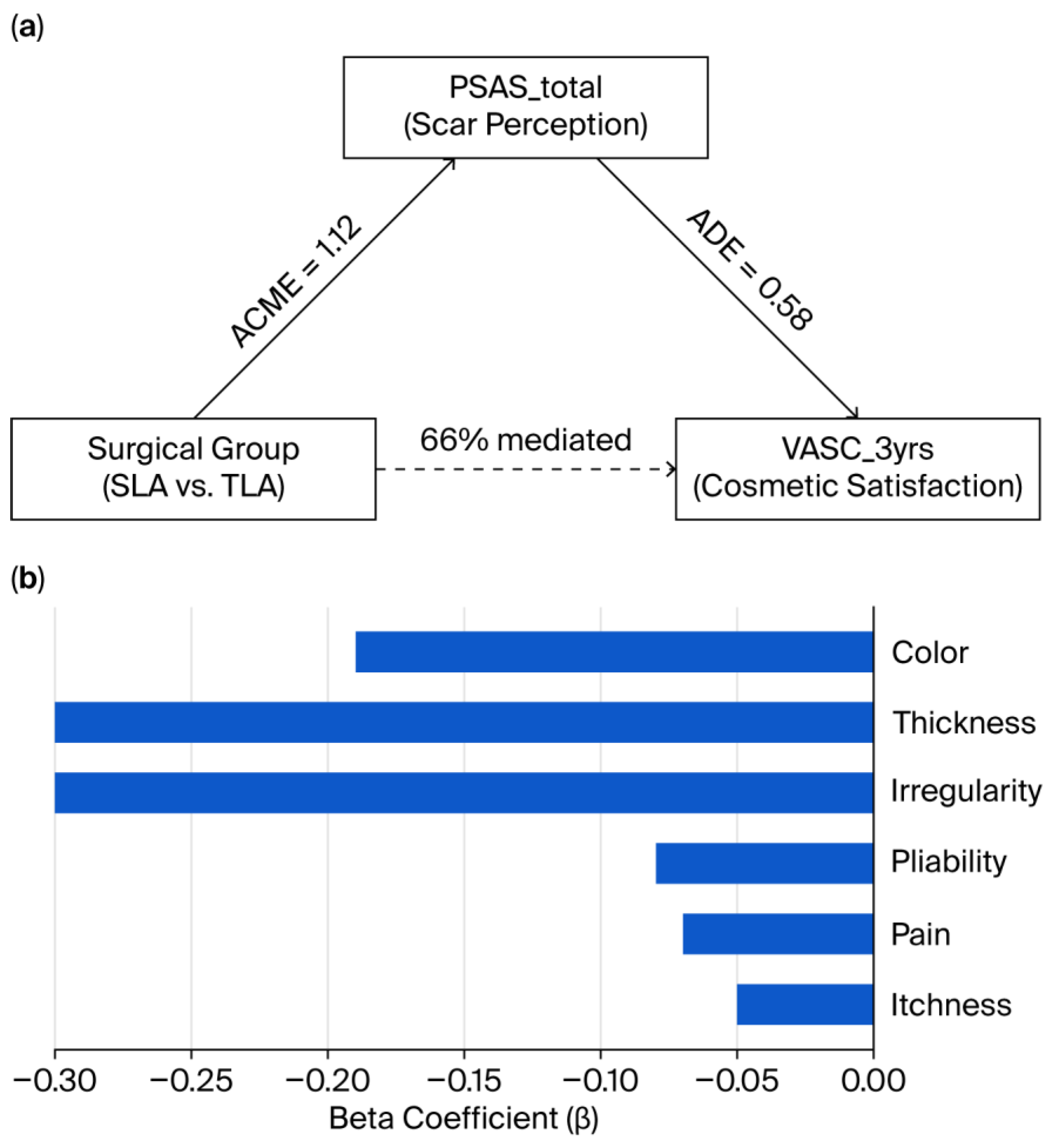

3.5. Mediation Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SLA | Single-port laparoscopic appendectomy |

| TLA | Three-port laparoscopic appendectomy |

| POD | Postoperative days |

| VASP | Visual Analog Scale for Pain |

| VASC | Visual Analog Scale for Cosmesis |

| PSAS | Patient and Parental Scar Assessment Scale |

| PSM | Propensity score matching |

| MCID | Minimal clinically important difference |

| ACME | Average causal mediation effect |

| ADE | Average direct effect |

Appendix A

| Patient and Parental Scar Assessment Scale | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No complaint | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | Worst imaginable | |

| Is the scar painful? | |||

| Is the scar itching? | |||

| As normal skin | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | Very different | |

| Is the color of the scar different? | |||

| Is the scar stiffer? | |||

| Is the thickness of the scar different? | |||

| Is the scar irregular? | |||

| Variable | SLA (Mean, SD) |

SLA (n) |

TLA (Mean, SD) |

TLA (n) |

MD (95% CI) |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VASPpreop_rest | 6.87 ± 2.42 | 121 | 6.46 ± 2.57 | 101 | 0.41 (−0.25 to 1.07) | 0.221 |

| VASP1_rest | 5.39 ± 2.56 | 121 | 5.31 ± 2.60 | 101 | 0.09 (−0.59 to 0.77) | 0.803 |

| VASP2_rest | 3.13 ± 2.10 | 121 | 2.95 ± 1.99 | 101 | 0.18 (−0.36 to 0.72) | 0.509 |

| VASP7_rest | 0.38 ± 0.92 | 118 | 0.53 ± 1.16 | 99 | −0.14 (−0.43 to 0.14) | 0.321 |

| VASPpreop_cough | 6.90 ± 2.47 | 121 | 6.32 ± 2.68 | 101 | 0.58 (−0.10 to 1.27) | 0.094 |

| VASP1_cough | 7.09 ± 2.06 | 121 | 6.86 ± 2.14 | 101 | 0.23 (−0.33 to 0.78) | 0.419 |

| VASP2_cough | 5.07 ± 1.92 | 121 | 5.00 ± 2.00 | 101 | 0.07 (−0.45 to 0.59) | 0.803 |

| VASP7_cough | 0.94 ± 1.60 | 118 | 1.41 ± 2.24 | 99 | −0.47 (−1.00 to 0.05) | 0.080 |

| VASPpreop_walk | 6.94 ± 2.50 | 121 | 6.54 ± 2.65 | 101 | 0.40 (−0.28 to 1.08) | 0.253 |

| VASP1_walk | 6.18 ± 2.26 | 121 | 6.10 ± 2.11 | 101 | 0.08 (−0.49 to 0.66) | 0.781 |

| VASP2_walk | 4.30 ± 1.99 | 121 | 3.99 ± 1.98 | 101 | 0.31 (−0.22 to 0.83) | 0.250 |

| VASP7_walk | 0.77 ± 1.40 | 118 | 1.41 ± 1.67 | 99 | −0.64 (−1.06 to −0.23) | 0.002 |

| deltaVASP1_rest | −1.48 ± 3.35 | 121 | −1.15 ± 3.34 | 101 | −0.33 (−1.21 to 0.56) | 0.468 |

| deltaVASP2_rest | −3.74 ± 3.10 | 121 | −3.50 ± 3.25 | 101 | −0.24 (−1.08 to 0.60) | 0.577 |

| deltaVASP7_rest | −6.53 ± 2.48 | 118 | −5.86 ± 2.82 | 99 | −0.68 (−1.39 to 0.04) | 0.065 |

| deltaVASP1_cough | 0.19 ± 2.77 | 121 | 0.54 ± 3.00 | 101 | −0.36 (−1.12 to 0.41) | 0.361 |

| deltaVASP2_cough | −1.84 ± 2.81 | 121 | −1.32 ± 3.30 | 101 | −0.53 (−1.34 to 0.29) | 0.207 |

| deltaVASP7_cough | −6.01 ± 2.75 | 118 | −4.83 ± 3.35 | 99 | −1.18 (−2.01 to −0.35) | 0.005 |

| deltaVASP1_walk | −0.76 ± 2.88 | 121 | −0.45 ± 3.03 | 101 | −0.32 (−1.10 to 0.46) | 0.427 |

| deltaVASP2_walk | −2.65 ± 2.72 | 121 | −2.55 ± 3.56 | 101 | −0.10 (−0.95 to 0.75) | 0.820 |

| deltaVASP7_walk | −6.22 ± 2.60 | 118 | −5.06 ± 3.23 | 99 | −1.16 (−1.95 to −0.37) | 0.004 |

| VASC_1month | 9.47 ± 0.86 | 111 | 9.29 ± 1.03 | 97 | 0.18 (−0.08 to 0.44) | 0.177 |

| VASC_3yrs | 9.39 ± 0.83 | 102 | 7.47 ± 1.98 | 90 | 1.93 (1.48 to 2.37) | 0.000 |

| PSAS_pain | 1.14 ± 0.35 | 102 | 1.24 ± 0.75 | 90 | −0.11 (−0.28 to 0.06) | 0.218 |

| PSAS_itchiness | 1.09 ± 0.29 | 102 | 1.12 ± 0.39 | 90 | −0.03 (−0.13 to 0.06) | 0.498 |

| PSAS_color | 1.28 ± 0.65 | 102 | 3.67 ± 2.75 | 90 | −2.38 (−2.96 to −1.80) | 0.000 |

| PSAS_stiffness | 1.14 ± 0.40 | 102 | 2.32 ± 2.13 | 90 | −1.18 (−1.63 to −0.74) | 0.000 |

| PSAS_thickness | 1.04 ± 0.24 | 102 | 3.08 ± 2.91 | 90 | −2.04 (−2.64 to −1.44) | 0.000 |

| PSAS_irregularity | 1.36 ± 1.15 | 102 | 2.34 ± 2.33 | 90 | −0.98 (−1.51 to −0.45) | 0.000 |

| PSAS_total | 7.05 ± 1.69 | 102 | 13.11 ± 8.37 | 90 | −6.06 (−7.82 to −4.30) | 0.000 |

| Variable | SLA (Mean, SD) |

SLA (n) |

TLA (Mean, SD) |

TLA (n) |

MD (95% CI) |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VASPpreop_rest | 7.26 ± 2.34 | 82 | 6.37 ± 2.54 | 82 | 0.89 (0.14 to 1.64) | 0.020 |

| VASP1_rest | 5.01 ± 2.47 | 82 | 5.02 ± 2.62 | 82 | −0.01 (−0.79 to 0.77) | 0.975 |

| VASP2_rest | 3.23 ± 2.27 | 82 | 3.07 ± 2.02 | 82 | 0.16 (−0.50 to 0.82) | 0.637 |

| VASP7_rest | 0.29 ± 0.90 | 82 | 0.41 ± 0.87 | 82 | −0.12 (−0.39 to 0.15) | 0.378 |

| VASPpreop_cough | 6.95 ± 2.45 | 82 | 6.20 ± 2.63 | 82 | 0.76 (−0.02 to 1.53) | 0.058 |

| VASP1_cough | 6.76 ± 1.97 | 82 | 6.62 ± 2.14 | 82 | 0.13 (−0.50 to 0.76) | 0.676 |

| VASP2_cough | 4.67 ± 1.85 | 82 | 4.95 ± 2.14 | 82 | −0.28 (−0.89 to 0.33) | 0.370 |

| VASP7_cough | 0.85 ± 1.63 | 82 | 1.43 ± 2.29 | 82 | −0.57 (−1.18 to 0.03) | 0.066 |

| VASPpreop_walk | 7.10 ± 2.42 | 82 | 6.27 ± 2.63 | 82 | 0.83 (0.06 to 1.60) | 0.037 |

| VASP1_walk | 5.54 ± 2.29 | 82 | 5.89 ± 2.17 | 82 | −0.35 (−1.04 to 0.33) | 0.312 |

| VASP2_walk | 3.87 ± 1.88 | 82 | 4.09 ± 1.99 | 82 | −0.22 (−0.81 to 0.37) | 0.468 |

| VASP7_walk | 0.63 ± 1.27 | 82 | 1.46 ± 1.57 | 82 | −0.83 (−1.27 to −0.39) | 0.000 |

| deltaVASP1_rest | −2.24 ± 3.64 | 82 | −1.34 ± 3.35 | 82 | −0.90 (−1.97 to 0.17) | 0.100 |

| deltaVASP2_rest | −4.02 ± 3.40 | 82 | −3.29 ± 3.18 | 82 | −0.73 (−1.74 to 0.27) | 0.156 |

| deltaVASP7_rest | −6.96 ± 2.30 | 82 | −5.95 ± 2.73 | 82 | −1.01 (−1.78 to −0.24) | 0.011 |

| deltaVASP1_cough | −0.20 ± 2.73 | 82 | 0.43 ± 3.10 | 82 | −0.62 (−1.52 to 0.27) | 0.174 |

| deltaVASP2_cough | −2.28 ± 2.72 | 82 | −1.24 ± 3.39 | 82 | −1.04 (−1.98 to −0.10) | 0.032 |

| deltaVASP7_cough | −6.10 ± 2.22 | 82 | −4.77 ± 3.35 | 82 | −1.33 (−2.20 to −0.46) | 0.003 |

| deltaVASP1_walk | −1.56 ± 2.87 | 82 | −0.38 ± 3.08 | 82 | −1.18 (−2.09 to −0.27) | 0.011 |

| deltaVASP2_walk | −3.23 ± 2.77 | 82 | −2.18 ± 3.46 | 82 | −1.05 (−2.01 to −0.09) | 0.033 |

| deltaVASP7_walk | −6.46 ± 2.28 | 82 | −4.80 ± 3.06 | 82 | −1.66 (−2.49 to −0.83) | 0.000 |

| VASC_1month | 9.57 ± 0.82 | 63 | 9.16 ± 1.12 | 63 | 0.41 (0.07 to 0.76) | 0.020 |

| VASC_3yrs | 9.56 ± 0.56 | 63 | 7.71 ± 1.63 | 63 | 1.84 (1.42 to 2.27) | 0.000 |

| PSAS_pain | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 63 | 1.10 ± 0.39 | 63 | −0.10 (−0.19 to 0.00) | 0.057 |

| PSAS_itchiness | 1.06 ± 0.25 | 63 | 1.06 ± 0.30 | 63 | 0.00 (−0.10 to 0.10) | 1.000 |

| PSAS_color | 1.25 ± 0.59 | 63 | 3.27 ± 2.14 | 63 | −2.02 (−2.56 to −1.47) | 0.000 |

| PSAS_stiffness | 1.22 ± 0.52 | 63 | 2.11 ± 1.92 | 63 | −0.89 (−1.38 to −0.40) | 0.001 |

| PSAS_thickness | 1.10 ± 0.43 | 63 | 2.57 ± 2.37 | 63 | −1.48 (−2.07 to −0.88) | 0.000 |

| PSAS_irregularity | 1.25 ± 0.54 | 63 | 2.11 ± 2.03 | 63 | −0.86 (−1.38 to −0.34) | 0.002 |

| PSAS_total | 6.89 ± 1.84 | 63 | 12.00 ± 6.86 | 63 | −5.11 (−6.87 to −3.36) | 0.000 |

| (a) | |

| Effect | Estimate |

| ACME (indirect) | 1.12 |

| ADE (direct) | 0.58 |

| Total Effect | 1.70 |

| Proportion Mediated | 0.66 |

| (b) | |

| PSAS Subitem | Beta Coefficient (β) Predicting VASC_3yrs |

| Color | −0.19 |

| Thickness | −0.30 |

| Irregularity | −0.30 |

| Pliability | −0.08 |

| Pain | −0.07 |

| Itchiness | −0.05 |

References

- Addiss, D.G.; Shaffer, N.; Fowler, B.S.; Tauxe, R.V. The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in the United States. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1990, 132, 910–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, O.; Athanasiou, T.; Tekkis, P.P.; Purkayastha, S.; Haddow, J.; Malinovski, V.; Paraskeva, P.; Darzi, A.; Heriot, A.G. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy in children: A meta-analysis. Ann. Surg. 2006, 243, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauerland, S.; Jaschinski, T.; Neugebauer, E.A. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for suspected appendicitis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 11, CD001546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Sang, L.; Zhang, W.; Chu, Z.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. Laparoscopic versus conventional appendectomy--a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010, 10, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelosi, M.A.; Pelosi, M.A. , 3rd. Laparoscopic appendectomy using a single umbilical puncture (minilaparoscopy). J. Reprod. Med. 1992, 37, 588–594. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, T.H.; Kim, H.L.; Lee, Y.S.; Kim, J.J.; Lee, K.H.; You, Y.K.; Oh, S.J.; Park, S.M. Transumbilical single-port laparoscopic appendectomy (TUSPLA): Scarless intracorporeal appendectomy. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. A 2009, 19, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, S.A.; Koch, O.O.; Antoniou, G.A.; Pointner, R.; Granderath, F.A. Meta-analysis of randomized trials on single-incision laparoscopic versus conventional laparoscopic appendectomy. Am. J. Surg. 2014, 207, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clerveus, M.; Morandeira-Rivas, A.; Moreno-Sanz, C.; Tadeo-Ruiz, G.; Picazo-Yeste, J.S.; Tadeo-Ruiz, G. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing single incision versus conventional laparoscopic appendectomy. World J. Surg. 2014, 38, 1937–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sozutek, A.; Colak, T.; Dirlik, M.; Ocal, K.; Turkmenoglu, O.; Dag, A. A prospective randomized comparison of single-port laparoscopic procedure with open and standard 3-port laparoscopic procedures in the treatment of acute appendicitis. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. Percutan. Tech. 2013, 23, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, E.A.; Piper, H.; Burkhalter, L.S.; Fischer, A.C. Single-incision laparoscopic surgery in children: A randomized controlled trial of acute appendicitis. Surg. Endosc. 2013, 27, 1367–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.E.; Choi, Y.S.; Kim, B.G.; Rah, H.; Choi, S.K.; Hong, T.H. Single-port laparoscopic appendectomy in children using glove port and conventional rigid instruments. Ann. Surg. Treat. Res. 2014, 86, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, G.; Mao, X.; Shi, M.; Zhang, J.; Jin, S.; Yao, L. Single-incision laparoscopic appendectomy versus traditional three-hole laparoscopic appendectomy for acute appendicitis in children by senior pediatric surgeons: A multicenter study from China. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1224113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Liao, Z.; Feng, S.; He, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Li, K. Single-incision versus conventional laparoscopic appendicectomy in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2015, 31, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imren, C.; IJsselstijn, H.; Vermeulen, M.J.; Wijnen, R.H.M.; Rietman, A.B.; Keyzer-Dekker, C.M.G. Scar perception in school-aged children after major surgery in infancy. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2024, 59, 161659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinvall, I.; Kennedy, S.; Karlsson, M.; Ellabban, M.A.; Sjöberg, F.; Andersson, C.; Elmasry, M.; Abdelrahman, I. Evaluating scar outcomes in pediatric burn patients following skin grafting. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasior, A.C.; Knott, E.M.; Holcomb, G.W., 3rd; Ostlie, D.J.; St Peter, S.D. Patient- and parent-reported scar satisfaction after single incision versus standard 3-port laparoscopic appendectomy: Long-term follow-up from a prospective randomized trial. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2014, 49, 120–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGlothlin, A.E.; Lewis, R.J. Minimal clinically important difference: Defining what really matters to patients. JAMA 2014, 312, 1342–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srouji, R.; Ratnapalan, S.; Schneeweiss, S. Pain in children: Assessment and nonpharmacological management. Int. J. Pediatr. 2010, 2010, 474838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearmonti, R.; Bond, J.; Erdmann, D.; Levinson, H. A review of scar scales and scar measuring devices. Eplasty 2010, 10, e43. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, P.C. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav. Res. 2011, 46, 399–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, C.V.; Kelly, A.M.; Williams, A. Determining the minimum clinically significant difference in visual analog pain score for children. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2001, 37, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandathil, C.K.; Cordeiro, P.G.; Matros, E. Minimal Clinically Important Difference of the Standardized Cosmesis and Health Nasal Outcomes Survey. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2019, 144, 86e–93e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draaijers, L.J.; Tempelman, F.R.; Botman, Y.A.; Tuinebreijer, W.E.; Middelkoop, E.; Kreis, R.W.; van Zuijlen, P.P. The Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale: A Reliable and Feasible Tool for Scar Evaluation. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2004, 113, 1960–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Kar, A.L.; Corion, L.U.; Smeulders, M.J.; Draaijers, L.J.; van der Horst, C.M.; van Zuijlen, P.P. Reliable and feasible evaluation of linear scars by the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2005, 116, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boo, Y.J.; Lee, S.J.; Yoon, H.R.; Kim, J.S.; Hong, T.H.; Choi, S.K. Comparison of transumbilical laparoscopic-assisted appendectomy versus single incision laparoscopic appendectomy in children: Which is the better surgical option? J. Pediatr. Surg. 2016, 51, 1288–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.I.; Woo, I.T.; Bae, S.U.; Yang, C.S. Single-incision versus conventional laparoscopic appendectomy: A multi-center randomized controlled trial (SCAR trial). Ann. Surg. 2018, 267, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, N.M.; Danielson, P.D. Single-incision laparoscopic appendectomy vs multiport laparoscopic appendectomy in children: A retrospective comparison. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2010, 45, 2186–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, A.Y.; Chiu, P.W.; Wong, T.C.; Wong, S.K.; Lai, P.B.; Ng, E.K. A double-blinded randomized controlled trial of laparoendoscopic single-site access versus conventional 3-port appendectomy. Ann. Surg. 2012, 256, 909–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, J.T.; Kaplan, J.A.; Nguyen, J.N.; Lin, M.Y.; Rogers, W.K.; Harris, H.W. A prospective, randomized controlled trial of single-incision laparoscopic vs conventional 3-port laparoscopic appendectomy for treatment of acute appendicitis. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2014, 218, 950–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frutos, M.D.; Abrisqueta, J.; Luján, J.; Abellan, I.; Parrilla, P. Randomized prospective study to compare laparoscopic appendectomy versus umbilical single-incision appendectomy. Ann. Surg. 2013, 257, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Baeyer, C.L. Children’s self-reports of pain intensity: Scale selection, limitations, and interpretation. Pain Res. Manag. 2006, 11, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinson, J.N.; Kavanagh, T.; Yamada, J.; Gill, N.; Stevens, B. Systematic review of the psychometric properties, interpretability, and feasibility of self-report pain intensity measures for use in clinical trials in children and adolescents. Pain 2006, 125, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamill, J.K.; Liley, A.; Hill, A.G. Intraperitoneal local anesthetic for laparoscopic appendectomy in children: A randomized controlled trial. Ann. Surg. 2015, 262, 1051–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, O.E.; Black, D.H.; Rehman, H.; Ahmed, I. Single incision laparoscopic appendicectomy versus conventional three-port laparoscopic appendicectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Surg. 2016, 35, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St Peter, S.D.; Adibe, O.O.; Juang, D.; Sharp, S.W.; Garey, C.L.; Laituri, C.A.; Murphy, J.P.; Snyder, C.L.; Holcomb, G.W., 3rd; Ostlie, D.J. Single incision versus standard 3-port laparoscopic appendectomy: A prospective randomized trial. Ann. Surg. 2011, 254, 586–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, R.; Zhao, L.; Liu, N.; Li, J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of single-incision versus conventional laparoscopic appendectomy in children. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2015, 50, 1600–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostlie, D.J.; Sharp, N.E.; Thomas, P.; Ostlie, M.M.; St Peter, S.D. Patient scar assessment after single-incision versus four-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Long-term follow-up from a prospective randomized trial. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. A 2013, 23, 553–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustoe, T.A.; Cooter, R.D.; Gold, M.H.; Hobbs, F.D.; Ramelet, A.A.; Shakespeare, P.G.; Stella, M.; Téot, L.; Wood, F.M.; Ziegler, U.E. International clinical recommendations on scar management. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2002, 110, 560–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, J.; Duncan, J.A.; Bond, J.S.; Durani, P.; So, K.; Mason, T.; O’Kane, S.; Ferguson, M.W. Scar-improving efficacy of avotermin administered into the wound margins of skin incisions as evaluated by a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II clinical trial. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2010, 126, 1604–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, J.A.; Bond, J.S.; Mason, T.; Ludlow, A.; Cridland, P.; O’Kane, S.; Ferguson, M.W. Visual analogue scale scoring and ranking: A suitable and sensitive method for assessing scar quality? Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2006, 118, 909–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsuno, G.; Fukunaga, M.; Nagakari, K.; Yoshikawa, S.; Azuma, D.; Kohama, S. Short-term and long-term outcomes of single-incision versus multi-port laparoscopic appendectomy for appendicitis: A propensity-score-matched analysis of a single-center experience. Surg. Today 2016, 46, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Lee, J.I.; Lee, Y.S.; Lee, I.K.; Park, J.H.; Lee, S.K.; Kang, W.K.; Cho, H.M.; You, Y.T.; Oh, S.T. Single-port transumbilical laparoscopic appendectomy: 43 consecutive cases. Surg. Endosc. 2010, 24, 2765–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, J.B.; Longaker, M.T.; Lorenz, H.P. Scarless fetal wound healing: A basic science review. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010, 6, CD001546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borges, A.F. Relaxed skin tension lines (RSTL) versus other skin lines. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1984, 73, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayat, A.; McGrouther, D.A.; Ferguson, M.W. Skin scarring. BMJ 2003, 326, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bock, O.; Schmid-Ott, G.; Malewski, P.; Mrowietz, U. Quality of life of patients with keloid and hypertrophic scarring. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2006, 297, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, L.; Jones, D.J. Silicone gel sheeting for preventing and treating hypertrophic and keloid scars. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013(9), CD003826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butzelaar, L.; Ulrich, M.M.; Mink van der Molen, A.B.; Niessen, F.B.; Beelen, R.H. Currently known risk factors for hypertrophic skin scarring: A review. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2016, 69, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwyn, G.; Frosch, D.; Thomson, R.; Joseph-Williams, N.; Lloyd, A.; Kinnersley, P.; Cording, E.; Tomson, D.; Dodd, C.; Rollnick, S.; et al. Shared decision making: A model for clinical practice. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2012, 27, 1361–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, D.; Harijan, A. Overview of surgical scar prevention and management. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2014, 29, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, N. Patient-reported outcome measures could help transform healthcare. BMJ 2013, 346, f167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | SLA, n = 127 | TLA, n = 111 | MD or OR [95% CI] | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, year | 10.1 ± 3.0 | 9.8 ± 3.1 | 0.34 [−0.46, 1.14] | 0.407 |

| Sex, male (%) | 53 (40.9) | 40 (36.0) | 1.27 [0.75, 2.15] | 0.425 |

| Weight, kg | 39.2 ± 14.6 | 38.3 ± 14.8 | 0.93 [−2.83, 4.69] | 0.629 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 18.6 ± 3.8 | 18.5 ± 3.8 | 0.09 [−0.96, 1.13] | 0.871 |

| WBC, ×103 | 14.1 ± 5.1 | 14.4 ± 4.8 | −0.31 [−1.59, 0.97] | 0.632 |

| Neutrophil, % | 77.7 ± 11.7 | 79.0 ± 12.2 | −1.32 [−4.37, 1.73] | 0.397 |

| CRP | 21.7 ± 29.5 | 20.5 ± 33.2 | 1.24 [−7.06, 9.54] | 0.770 |

| Operation time, min | 41.3 ± 18.1 | 43.4 ± 17.0 | −2.09 [−6.58, 2.39] | 0.360 |

| Postoperative days | 1.9 ± 0.17 | 1.9 ± 0.10 | −0.01 [−0.04, 0.02] | 0.717 |

| Wound seroma | 3 (2.3%) | 3 (2.7%) | 0.87 [0.17, 4.41] | 0.871 |

| Postoperative ileus | 3 (2.3%) | 2 (1.8%) | 1.32 [0.22, 8.04] | 1.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).