Submitted:

08 September 2025

Posted:

09 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction to the Gut Microbiome and Cardiovascular Health

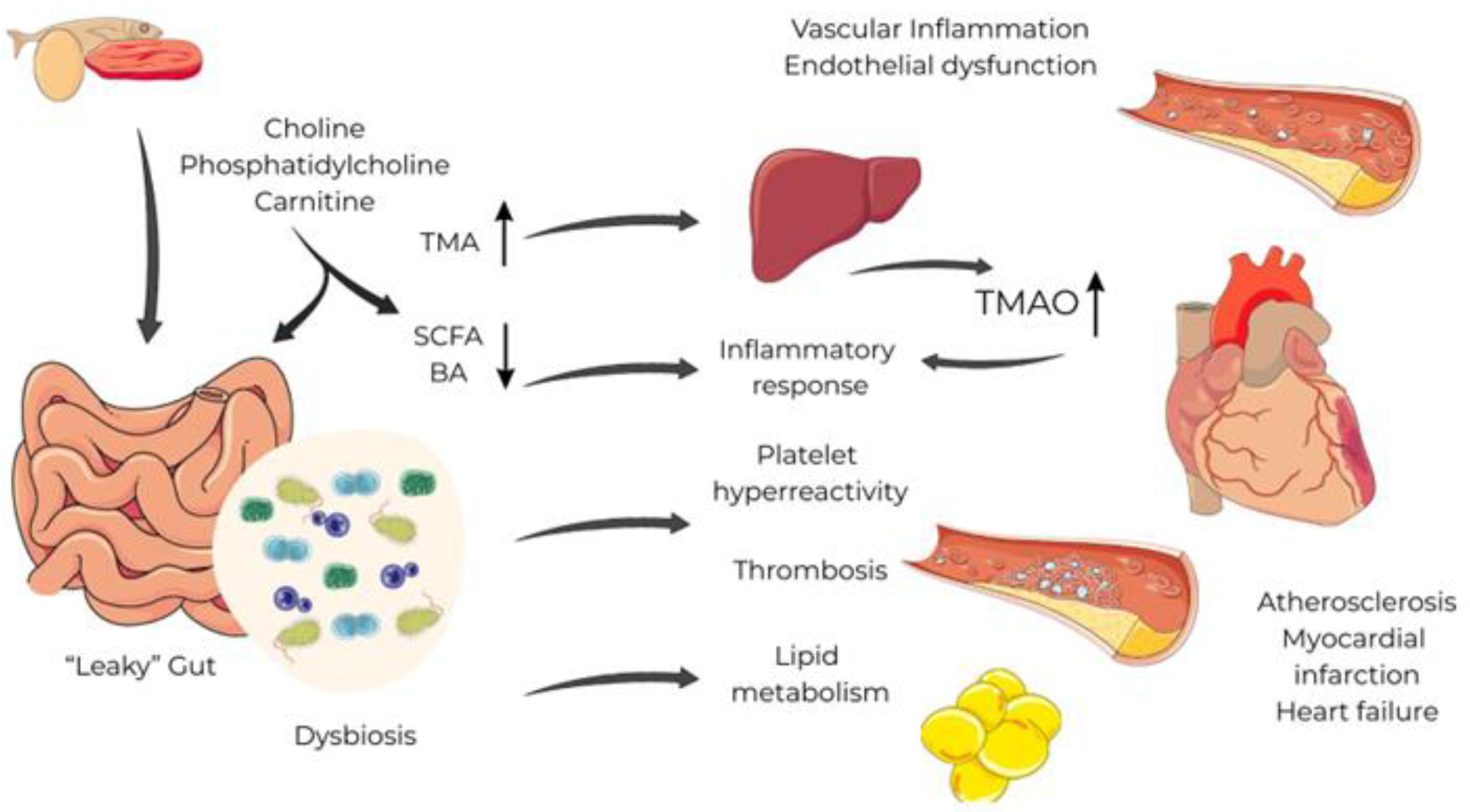

2. The Gut-Heart Axis, Dysbiosis and Systemic Inflammation

3. Role of the Key Gut-Derived Metabolites

3.1. Trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO)

3.2. Short Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs)

3.3. Secondary Bile Acids (SBAs)

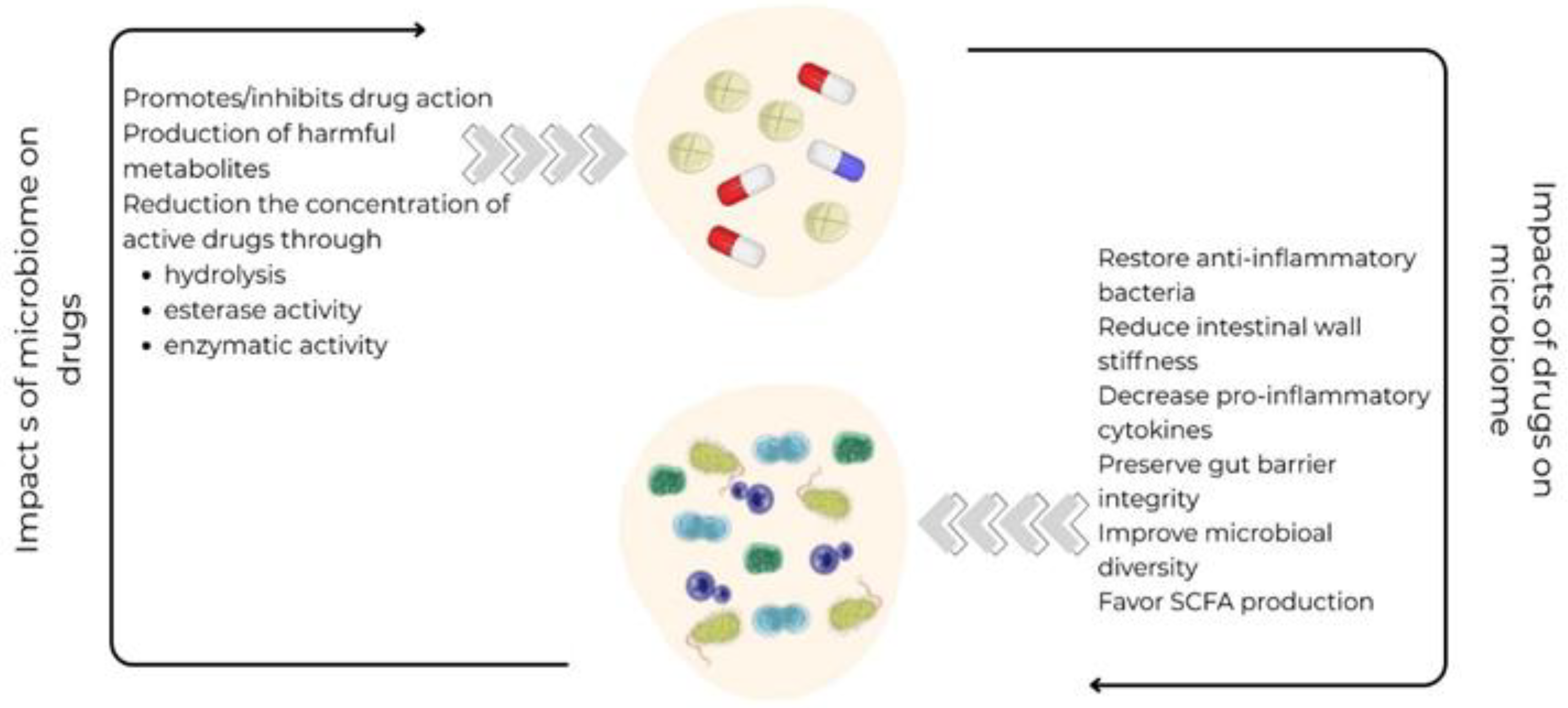

4. Impact of CVD Drugs on the Gut Microbiome - Pharmacomicrobiomics

4.1. Statins

4.2. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors/ Angiotensin Receptor Blockers

4.3. Cardiac Glycosides

4.4. Antiplatelets

4.5. Beta Blockers

4.6. Other Classes of Heart Failure Drugs

5. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| MetaHIT | Metagenomics of the Human Intestinal Tract |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alfa |

| IFN-γ | Interferon gamma |

| TMAO | Trimethylamine-N-oxide |

| SCFAs | Short-chain fatty acids |

| SBAs | Secondary bile acids |

| MACE | Major Adverse Cardiac Events |

| BNP | B-type natriuretic peptide |

| FXR | Farnesoid X receptor |

| TGR5 | Takeda G protein-coupled receptor 5 |

| LDL | Low-Density Lipoprotein |

| HDL | High-Density Lipoprotein |

| RAAS | Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system |

| AT1R | Angiotensin 1 receptor |

| AT2R | Angiotensin 2 receptor |

| ARBs | Angiotensin receptor blockers |

| ACEIs | Angiotensin receptor inhibitors |

References

- Longoria CR, Guers JJ, Campbell SC. The Interplay between Cardiovascular Disease, Exercise, and the Gut Microbiome. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2022;23(11):365. Published 2022 Oct 27. [CrossRef]

- Astudillo AA, Mayrovitz HN. The Gut Microbiome and Cardiovascular Disease. Cureus. 2021;13(4):e14519. Published 2021 Apr 16. [CrossRef]

- Li, X. , Ma, Y., Zhang, C., Liu, C., Shi, Y., Wang (2024). Genome-wide association analysis of gut microbiome and serum metabolomics identifies heart failure therapeutic targets.

- Du Y, Li X, Su C, Wang L, Jiang J, Hong B. The human gut microbiome - a new and exciting avenue in cardiovascular drug discovery. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2019;14(10):1037-1052. [CrossRef]

- Vieira-Silva S, Falony G, Belda E, et al. Statin therapy is associated with lower prevalence of gut microbiota dysbiosis. Nature. 2020;581(7808):310-315. [CrossRef]

- Mishima E, Abe T. Role of the microbiota in hypertension and antihypertensive drug metabolism. Hypertens Res. 2022;45(2):246-253. [CrossRef]

- Xiong Y, Zhu P, et al. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Hypertension Pathogenesis and the Efficacy of Antihypertensive Drugs. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2021;23(8):40. Published 2021 Sep 6. [CrossRef]

- Li W, Li C, Ren C, et al. Bidirectional effects of oral anticoagulants on gut microbiota in patients with atrial fibrillation. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023;13:1038472. Published 2023 Mar 24. [CrossRef]

- Novakovic M, Rout A, Kingsley T, et al. Role of gut microbiota in cardiovascular diseases. World J Cardiol. 2020;12(4):110-122. [CrossRef]

- Zhou W, Cheng Y, Zhu P, Nasser MI, Zhang X, Zhao M. Implication of Gut Microbiota in Cardiovascular Diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020:5394096. Published 2020 Sep 26. [CrossRef]

- Battson ML, Lee DM, Weir TL, Gentile CL. The gut microbiota as a novel regulator of cardiovascular function and disease. J Nutr Biochem. 2018;56:1-15. [CrossRef]

- Morrison, Mark, Murtaza, Nida Talley, Nicholas J. Pimentel, Mark Mathur, Ruchi Barlow, Gillian M. 2023, Clinical Understanding of the Human Gut Microbiome, The Importance of the Microbiome in the Gut p 1- 11, Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Papadopoulos PD, Tsigalou C, Valsamaki PN, Konstantinidis TG, Voidarou C, Bezirtzoglou E. The Emerging Role of the Gut Microbiome in Cardiovascular Disease: Current Knowledge and Perspectives. Biomedicines. 2022;10(5):948. Published 2022 Apr 20. [CrossRef]

- Abdulrahim AO, Doddapaneni NSP, Salman N, et al. The gut-heart axis: a review of gut microbiota, dysbiosis, and cardiovascular disease development. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2025;87(1):177-191. Published 2025 Jan 9. [CrossRef]

- Witkowski M, Weeks TL, Hazen SL. Gut Microbiota and Cardiovascular Disease. Circ Res. 2020;127(4):553-570. [CrossRef]

- Cheng CK, Huang Y. The gut-cardiovascular connection: new era for cardiovascular therapy. Med Rev (2021). 2021 Oct 21;1(1):23-46.

- Rahman MM, Islam F, -Or-Rashid MH, et al. The Gut Microbiota (Microbiome) in Cardiovascular Disease and Its Therapeutic Regulation. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:903570. Published 2022 Jun 20. [CrossRef]

- Lewis CV, Taylor WR. Intestinal barrier dysfunction as a therapeutic target for cardiovascular disease. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2020;319(6):H1227-H1233. [CrossRef]

- Duttaroy AK. Role of Gut Microbiota and Their Metabolites on Atherosclerosis, Hypertension and Human Blood Platelet Function: A Review. Nutrients. 2021;13(1):144. Published 2021 Jan 3. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Klipfell E, Bennett BJ, et al. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2011;472(7341):57-63. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad AF, Dwivedi G, O'Gara F, Caparros-Martin J, Ward NC. The gut microbiome and cardiovascular disease: current knowledge and clinical potential. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2019;317(5):H923-H938. [CrossRef]

- Tang WHW, Bäckhed F, Landmesser U, Hazen SL. Intestinal Microbiota in Cardiovascular Health and Disease: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(16):2089-2105. [CrossRef]

- Matter CM, Stähli BE, Scharl M. The Gut–Heart Axis: Effects of Intestinal Microbiome Modulation on Cardiovascular Disease—Ready for Therapeutic Interventions? International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024; 25(24):13529. [CrossRef]

- Tang WHW, Hazen SL. Unraveling the Complex Relationship Between Gut Microbiome and Cardiovascular Diseases. Circulation. 2024;149(20):1543-1545. [CrossRef]

- Dharmarathne G, Kazi S, King S, Jayasinghe TN. The Bidirectional Relationship Between Cardiovascular Medications and Oral and Gut Microbiome Health: A Comprehensive Review. Microorganisms. 2024;12(11):2246. Published 2024 Nov 6. [CrossRef]

- Jansen VL, Gerdes VE, Middeldorp S, van Mens TE. Gut microbiota and their metabolites in cardiovascular disease. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;35(3):101492. [CrossRef]

- Avery EG, Bartolomaeus H, Maifeld A, et al. The Gut Microbiome in Hypertension: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives. Circ Res. 2021;128(7):934-950. [CrossRef]

- BNF (British Nutrition Foundation), Sara Stanner, Sarah Coe, Keith N. Frayn, Cardiovascular Disease: Diet, Nutrition and Emerging Risk Factors, 2nd Edition, December 2018, Wiley-Blackwell, pages 276-277.

- Lupu VV, Adam Raileanu A, Mihai CM, et al. The Implication of the Gut Microbiome in Heart Failure. Cells. 2023;12(8):1158. Published 2023 Apr 14. [CrossRef]

- Cao H, Zhu Y, Hu G, Zhang Q, Zheng L. Gut microbiome and metabolites, the future direction of diagnosis and treatment of atherosclerosis?. Pharmacol Res. 2023;187:106586. [CrossRef]

- Zaher A, Elsaygh J, Peterson SJ, Weisberg IS, Parikh MA, Frishman WH. The Interplay of Microbiome Dysbiosis and Cardiovascular Disease. Cardiol Rev. Published online April 26, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Oniszczuk A, Oniszczuk T, Gancarz M, Szymańska J. Role of Gut Microbiota, Probiotics and Prebiotics in the Cardiovascular Diseases. Molecules. 2021;26(4):1172. Published 2021 Feb 22. [CrossRef]

- Rajendiran E, Ramadass B, Ramprasath V. Understanding connections and roles of gut microbiome in cardiovascular diseases. Can J Microbiol. 2021;67(2):101-111. [CrossRef]

- Al Samarraie A, Pichette M, Rousseau G. Role of the Gut Microbiome in the Development of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(6):5420. Published 2023 Mar 12. [CrossRef]

- Branchereau M, Burcelin R, Heymes C. The gut microbiome and heart failure: A better gut for a better heart. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2019;20(4):407-414. [CrossRef]

- Gao K, Wang PX, Mei X, Yang T, Yu K. Untapped potential of gut microbiome for hypertension management. Gut Microbes. 2024;16(1):2356278. [CrossRef]

- Chen HQ, Gong JY, Xing K, Liu MZ, Ren H, Luo JQ. Pharmacomicrobiomics: Exploiting the Drug-Microbiota Interactions in Antihypertensive Treatment. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;8:742394. Published 2022 Jan 19. [CrossRef]

- Weersma RK, Zhernakova A, Fu J. Interaction between drugs and the gut microbiome. Gut. 2020;69(8):1510-1519. [CrossRef]

- Stepanov, M. S. (2024). Influence of intestinal microbiota on the metabolism of main cardiotropic drugs. Perm Medical Journal, 41(5), 54-65. [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann F, Roessler J, Schmidt D, et al. Impact of the Gut Microbiota on Atorvastatin Mediated Effects on Blood Lipids. J Clin Med. 2020;9(5):1596. Published 2020 May 25. [CrossRef]

- Wilmanski T, Kornilov SA, Diener C, et al. Heterogeneity in statin responses explained by variation in the human gut microbiome. Med. 2022;3(6):388-405.e6. [CrossRef]

- Dias AM, Cordeiro G, Estevinho MM, et al. Gut bacterial microbiome composition and statin intake-A systematic review. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2020;8(3):e00601. [CrossRef]

- Sun B, Li L, Zhou X. Comparative analysis of the gut microbiota in distinct statin response patients in East China. J Microbiol. 2018;56(12):886-892. [CrossRef]

- Eid HM, Wright ML, Anil Kumar NV, et al. Significance of Microbiota in Obesity and Metabolic Diseases and the Modulatory Potential by Medicinal Plant and Food Ingredients. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:387. Published 2017 Jun 30. [CrossRef]

- Shi L, Liu X, Li E, Zhang S, Zhou A. Association of lipid-lowering drugs with gut microbiota: A Mendelian randomization study. J Clin Lipidol. 2024;18(5):e797-e808. [CrossRef]

- Tian Y, Wu G, Zhao X, et al. Probiotics combined with atorvastatin administration in the treatment of hyperlipidemia: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103(21):e37883. [CrossRef]

- Suresh, Mithil Gowda1; Mohamed, Safia2; Yukselen, Zeynep1; Hatwal, Juniali3; Venkatakrishnan, Abhinaya4; Metri, Aida5; Bhardwaj, Arshia6; Singh, Arshdeep6; Bush, Nikhil7; Batta, Akash8. Therapeutic Modulation of Gut Microbiome in Cardiovascular Disease: A Literature Review. Heart and Mind 9(1):p 68-79, Jan–Feb 2025. [CrossRef]

- Khan TJ, Ahmed YM, Zamzami MA, et al. Atorvastatin Treatment Modulates the Gut Microbiota of the Hypercholesterolemic Patients. OMICS. 2018;22(2):154-163. [CrossRef]

- Kummen M, Solberg OG, Storm-Larsen C, et al. Rosuvastatin alters the genetic composition of the human gut microbiome. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):5397. Published 2020 Mar 25. [CrossRef]

- Kaddurah-Daouk R, Baillie RA, Zhu H, et al. Enteric microbiome metabolites correlate with response to simvastatin treatment [published correction appears in PLoS One. 2013;8(5). https://doi.org/10.1371/annotation/8e8e95ca-1ac3-4acf-abcb-223cd11ac1c1]. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e25482. [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Wang Y, Wang H, et al. The influence of the intestinal microflora to the efficacy of Rosuvastatin. Lipids Health Dis. 2018;17(1):151. Published 2018 Jun 30. [CrossRef]

- Lucas SE, Walton SL, Mirabito Colafella KM, Mileto SJ, Lyras D, Denton KM. Antihypertensives and Antibiotics: Impact on Intestinal Dysfunction and Hypertension. Hypertension. 2023;80(7):1393-1402. [CrossRef]

- González-Correa C, Moleón J, Miñano S, et al. Differing contributions of the gut microbiota to the blood pressure lowering effects induced by first-line antihypertensive drugs. Br J Pharmacol. 2024;181(18):3420-3444. [CrossRef]

- Dong Y, Wang P, Jiao J, Yang X, Chen M, Li J. Antihypertensive Therapy by ACEI/ARB Is Associated With Intestinal Flora Alterations and Metabolomic Profiles in Hypertensive Patients. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:861829. Published 2022 Mar 23. [CrossRef]

- Kyoung J, Atluri RR, Yang T. Resistance to Antihypertensive Drugs: Is Gut Microbiota the Missing Link?. Hypertension. 2022;79(10):2138-2147. [CrossRef]

- Yang T, Mei X, Tackie-Yarboi E, et al. Identification of a Gut Commensal That Compromises the Blood Pressure-Lowering Effect of Ester Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors. Hypertension. 2022;79(8):1591-1601. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Han Y, Huang W, Jin M, Gao Z. The influence of the gut microbiota on the bioavailability of oral drugs. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;11(7):1789-1812. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Baeza Y, Callewaert C, Debelius J, et al. Impacts of the Human Gut Microbiome on Therapeutics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2018;58:253-270. [CrossRef]

- Steiner HE, Gee K, Giles J, Knight H, Hurwitz BL, Karnes JH. Role of the gut microbiome in cardiovascular drug response: The potential for clinical application. Pharmacotherapy. 2022;42(2):165-176. [CrossRef]

- Haiser HJ, Seim KL, Balskus EP, Turnbaugh PJ. Mechanistic insight into digoxin inactivation by Eggerthella lenta augments our understanding of its pharmacokinetics. Gut Microbes. 2014;5(2):233-238. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Q, Chen Y, Huang W, Zhou H, Zhang W. Drug-microbiota interactions: an emerging priority for precision medicine. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):386. Published 2023 Oct 9. [CrossRef]

- Curini L, Amedei A. Cardiovascular Diseases and Pharmacomicrobiomics: A Perspective on Possible Treatment Relevance. Biomedicines. 2021;9(10):1338. Published 2021 Sep 28. [CrossRef]

- Alhajri N, Khursheed R, Ali MT, et al. Cardiovascular Health and The Intestinal Microbial Ecosystem: The Impact of Cardiovascular Therapies on The Gut Microbiota. Microorganisms. 2021;9(10):2013. Published 2021 Sep 23. [CrossRef]

- Tuteja S, Ferguson JF. Gut Microbiome and Response to Cardiovascular Drugs. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2019;12(9):421-429. [CrossRef]

- Li T, Ding N, Guo H, et al. A gut microbiota-bile acid axis promotes intestinal homeostasis upon aspirin-mediated damage. Cell Host Microbe. 2024;32(2):191-208.e9. [CrossRef]

- Romano KA, Nemet I, Prasad Saha P, et al. Gut Microbiota-Generated Phenylacetylglutamine and Heart Failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2023;16(1):e009972. [CrossRef]

- Authors/Task Force Members:; McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, Burri H, Butler J, Čelutkienė J, Chioncel O, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, Crespo-Leiro MG, Farmakis D, Gilard M, Heymans S, Hoes AW, Jaarsma T, Jankowska EA, Lainscak M, Lam CSP, Lyon AR, McMurray JJV, Mebazaa A, Mindham R, Muneretto C, Francesco Piepoli M, Price S, Rosano GMC, Ruschitzka F, Kathrine Skibelund A; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). With the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail. 2022 Jan;24(1):4-131.

- Shearer J, Shah S, Shen-Tu G, Schlicht K, Laudes M, Mu C. Microbial Features Linked to Medication Strategies in Cardiometabolic Disease Management. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2024;7(4):991-1001. Published 2024 Feb 5. [CrossRef]

- Zheng T, Marques FZ. Gut Microbiota: Friends or Foes for Blood Pressure-Lowering Drugs. Hypertension. 2022 Aug;79(8):1602-1604. [CrossRef]

- Deng X, Zhang C, Wang P, et al. Cardiovascular Benefits of Empagliflozin Are Associated With Gut Microbiota and Plasma Metabolites in Type 2 Diabetes [published correction appears in J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022 Nov 23;107(11):e4330. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgac506.]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107(7):1888-1896. [CrossRef]

- González-Correa C, Moleón J, Miñano S, et al. Mineralocorticoid receptor blockade improved gut microbiota dysbiosis by reducing gut sympathetic tone in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;158:114149. [CrossRef]

- Wang P, Guo R, Bai X, et al. Sacubitril/Valsartan contributes to improving the diabetic kidney disease and regulating the gut microbiota in mice. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:1034818. Published 2022 Dec 16. [CrossRef]

- Cuervo L, McAlpine PL, Olano C, Fernández J, Lombó F. Low-Molecular-Weight Compounds Produced by the Intestinal Microbiota and Cardiovascular Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(19):10397. Published 2024 Sep 27. [CrossRef]

- Schiattarella GG, Sannino A, Esposito G, Perrino C. Diagnostics and therapeutic implications of gut microbiota alterations in cardiometabolic diseases. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2019;29(3):141-147. [CrossRef]

- Tang WHW, Li DY, Hazen SL. Dietary metabolism, the gut microbiome, and heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2019;16(3):137-154. [CrossRef]

- Vich Vila A, Collij V, Sanna S, et al. Impact of commonly used drugs on the composition and metabolic function of the gut microbiota. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):362. Published 2020 Jan 17. [CrossRef]

- Paraskevaidis I, Briasoulis A, Tsougos E. Oral Cardiac Drug-Gut Microbiota Interaction in Chronic Heart Failure Patients: An Emerging Association. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(3):1716. Published 2024 Jan 31. [CrossRef]

- Mamic P, Chaikijurajai T, Tang WHW. Gut microbiome - A potential mediator of pathogenesis in heart failure and its comorbidities: State-of-the-art review. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2021;152:105-117. [CrossRef]

- Trøseid M, Andersen GØ, Broch K, Hov JR. The gut microbiome in coronary artery disease and heart failure: Current knowledge and future directions. EBioMedicine. 2020;52:102649. [CrossRef]

- Vallianou NG, Geladari E, Kounatidis D. Microbiome and hypertension: where are we now?. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2020;21(2):83-88. [CrossRef]

- Muralitharan RR, Buikema JW, Marques FZ. Minimizing gut microbiome confounding factors in cardiovascular research. Cardiovasc Res. 2024;120(15):e60-e62. [CrossRef]

- Mamic P, Snyder M, Tang WHW. Gut Microbiome-Based Management of Patients With Heart Failure: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;81(17):1729-1739. [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann M, Zimmermann-Kogadeeva M, Wegmann R, Goodman AL. Mapping human microbiome drug metabolism by gut bacteria and their genes. Nature. 2019;570(7762):462-467. [CrossRef]

| Drug effect | Microbial strain |

|---|---|

| Statins |

↑Lactobacillus ↑Bifidobacterium ↑Faecalibacterium ↑Eubacterium |

| ACEI/ARB |

↓Enterobacter ↓Klebsiella ↑Odoribacter |

| Aspirin |

↓Parabacteroides goldsteinii ↓Prevotella ↓Ruminococcaceae ↓Bacteroides ↓Barnesiella |

| Beta-blockers |

↑Streptococcus ↑Lactobacillus ↓Akkermansia muciniphila ↓Eggerthella lenta |

| Beta-blockers+aspirin/diuretics |

↑Roseburia |

| Empagliflozin |

↑Roseburia ↑Eubacterium ↑Faecalibacterium |

| Spironolactone |

↑Bacteroides ↑Prevotella ↓Eubacteriacea ↓Clostridiales |

| Sacubitril/Valsartan |

↓Escherichia ↓Shigella ↑Lactobacillus ↑Bacteroides ↑Parabacteroides |

| Study | Year of publication | Study design | Results |

Future insights |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sun et al. [43] | 2018 | Clinical trial involving hypercholesterolemic patients treated with atorvastatin. It compares the composition of gut microbiota between statin sensitive and resistant groups. |

Gut microbiota composition differs significantly between statin sensitive and statin resistant patients. The statin sensitive group exhibited higher biodiversity compared to resistant group. Increased Lactobacillus, Eubacterium, Faecalibacterium, and Bifidobacterium. Decreased proportion of Clostridium. |

The impact of genetic polymorphisms on statin pharmacodynamics remains a significant area of research. Further studies could assess how different bacterial taxa influence statin efficacy and dosage adjustments. |

| Shi et al. [45] | 2024 | A Mendelian randomization two-sample design, which utilizes genetic variants to estimate the impact of lipid-lowering medication on gut microbiota diversity. |

Different genetic proxies for lipid-lowering drugs affects the abundance of gut microbiota. Some has been associated with an increase in the genus Eggerthella. Others were linked to the order Pasteurellales and the genus Haemophilus. |

Studies using individual-level data are needed for comprehensive insights on associations. Investigating the effects of lipid-lowering drugs across different patient subgroups is necessary. |

| Tian et al. [46] | 2024 | A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial aimed to assess the role of probiotics in treating hyperlipidemia. |

Probiotics reduced total cholesterol, triglycerides, and LDLc- levels in patients with hyperlipidemia. Probiotics increased Tenericutes and reduced Proteobacteria at the phylum level. Increased the abundance of Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, and Akkermansia genus, and decreased Escherichia, Eggerthella, and Sutterella. |

Future research should explore different probiotic strains and long-term effects. Larger, multi-center clinical trials are warranted to confirm findings. |

| Suresh et al. [47] | 2024 | A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials including clinical and observational studies, focusing on the gut microbiome and SCFAs. |

SCFAs are identified as beneficial in decreasing CVD risk factors. |

Investigating the long-term impacts of microbiome manipulation on cardiovascular health is essential. Understanding the interactions between cardiovascular medications and the gut microbiome has potentials to optimize treatment efficacy. |

| Khan et al. [48] | 2018 | A cross-sectional observational study that compares gut microbiota analyses among three groups: untreated hypercholesterolemic patients, atorvastatin-treated patients, and healthy subjects. |

Atorvastatin treatment increased anti-inflammatory bacteria, A. muciniphila and F. prausnitzii, and decreased the levels of proinflammatory taxa, such as members of Proteobacteria phylum, in hypercholesterolemic patients. |

Future studies should focus on the specific mechanisms by which gut microbiota influences lipid metabolism and inflammation. |

| Kummen et al. [49] | 2020 | A randomized controlled trial assessing the effects of rosuvastatin on gut microbiome composition. |

Rosuvastatin treatment showed no significant changes in gut microbial diversity. Reduced potential to metabolize TMAO precursors. |

Re-analyzing TMAO-related metabolites in previous statin trials could provide valuable insights. Exploring the mechanisms behind the pleiotropic effects of statins may enhance understanding of their impact on the microbiome. |

| Kaddurah-Daouk et al. [50] | 2011 | Clinical investigation aiming to elucidate variability in statin response through metabolomic profiling. |

Increased simvastatin levels correlated with higher BAs concentrations. |

Further research should focus on the interactions between genome, microbiome, and environmental factors in cardiovascular disease management. |

| Wang L et al. [51] | 2018 | An experimental investigation involving rat models to analyze the effects of intestinal microflora on lipid-reduction efficacy of rosuvastatin. |

Intestinal microflora significantly alters the lipid-reduction efficacy of rosuvastatin. Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium populations were markedly reduced when antibiotics were associated to rosuvastatin treatment. Microbiome diversity recovered four weeks post-antibiotic treatment, restoring the efficacy of statin treatment. |

Investigating the long-term effects of antibiotic treatment on intestinal microflora diversity and lipid metabolism is essential. The role of specific probiotics in enhancing the efficacy of rosuvastatin call for further investigation. |

| Dong et al. [54] | 2022 | A cross-sectional analysis including patients with hypertension to evaluate the effects of ACEI/ARBs on gut microbiome and metabolites. |

ACEI/ARBs therapy reduces pathogenic bacteria like Enterobacter and Klebsiella while increasing beneficial ones such as Odoribacter. |

Research is needed to monitor dynamic changes in microbial and metabolic features between well-controlled hypertensive patients and healthy subjects using ACEI/ARBs. |

| Yang et al. [56] | 2022 | Preclinical research using spontaneously hypertensive rats to assess the effects of gut microbiota on antihypertensive medications. |

Gut microbiome can reduce the antihypertensive effect of quinapril in spontaneously hypertensive rats treated with antibiotics. Coprococcus comes catabolizes ester ACE inhibitors, lowering their effectiveness. |

In vivo researches are needed to investigate the impact of gut microbiota on antihypertensive medication effects. Identifying specific gut microbes could unveil new therapeutic strategies for resistant hypertension. |

| Steiner et al. [59] | 2022 | The paper discusses guidelines for reporting gut microbiome analysis in experimental hypertension. |

Various cardiovascular drugs, like captopril and aspirin, interact with gut microbiota, affecting their pharmacokinetics. |

Research should assess the impact of microbiome alterations on drug response variability across demographics and comorbidities. Advanced sequencing and computational techniques may better characterize the relationship of microbiome and cardiovascular drug therapy. |

| Haiser et al. [60] | 2014 | The research integrates gut microbiome studies into personalized medicine through various experimental approaches, involving human intervention studies and gnotobiotic mouse experiments. | The study identified a cytochrome-encoding operon in Eggerthella lenta, activated by digoxin, serving as a microbial biomarker for drug inactivation |

Investigating the predictive value of specific operon abundance on digoxin pharmacokinetics in diverse patient populations is essential. Human intervention trials are needed to explore co-therapy strategies. The application of this framework to other drugs influenced by gut microbiota is also suggested. |

| Li et al. [65] | 2024 | The study is a combination of clinical and experimental research, utilizing both human cohorts and animal models. |

Aspirin treatment significantly decreased the abundance of Parabacteroides, particularly Parabacteroides goldsteinii, in healthy individuals. Mice supplemented with Parabacteroides goldsteinii showed reduced aspirin-mediated intestinal damage. |

Future research should focus on exploring the function of specific genes found in the genomes of various microorganisms. Understanding the mechanisms by which Parabacteroides species contribute to BAs metabolism and gut health. |

| Shearer et al. [68] | 2024 | A population-based cohort study, involving 134 middle-aged adults diagnosed with cardiometabolic disease, focusing on the relationship between medication use and gut microbiota composition. |

46 associations were identified between microbial composition and single medications, including β-blockers and statins depleting Akkermansia muciniphila. Increasing medication use correlated negatively with α-diversity in gut microbiota among participants. |

Future research could utilize fecal metabolomics profiling to confirm functional changes in gut microbiota. Further exploration of the relationship between medications and gut microbiota at genus and species levels is warranted. |

| Deng et al. [70] | 2022 | Randomized, open-label, two-arm clinical trial which included treatment-naive patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular risk factors. |

Significant reductions were found in glycated hemoglobin levels in both empagliflozin and metformin groups. Empagliflozin increased beneficial SCFA-producing bacteria and reduced harmful strains. |

Larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods are needed to investigate the underlying mechanisms of empagliflozin related microbiome changes. Different SGLT2 inhibitors might have as well impact on gut microbiome composition. |

| González-Correa et al. [71] | 2023 | Experimental research on animal models, investigating the effects of spironolactone on gut microbiome and hypertension. |

Spironolactone improved gut dysbiosis in spontaneously hypertensive rats by restoring Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes proportions and acetate-producing bacteria populations to normal levels. |

Exploring the long-term effects of spironolactone treatment on gut dysbiosis and overall health in hypertensive models. |

| Wang P et al. [72] | 2022 | Preclinical investigation involving male mice, aimed to explore the effects of Sacubitril/Valsartan on diabetic kidney disease. |

Sacubitril/Valsartan treatment increased beneficial SCFAs-producing bacteria. |

Future research should verify the findings of this preliminary study in clinical experiments. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).