Submitted:

27 January 2025

Posted:

27 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Patients and Cohorts

2.2. Sample Collection and Preparation

2.3. 16S rRNA Microbiome Sequencing Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

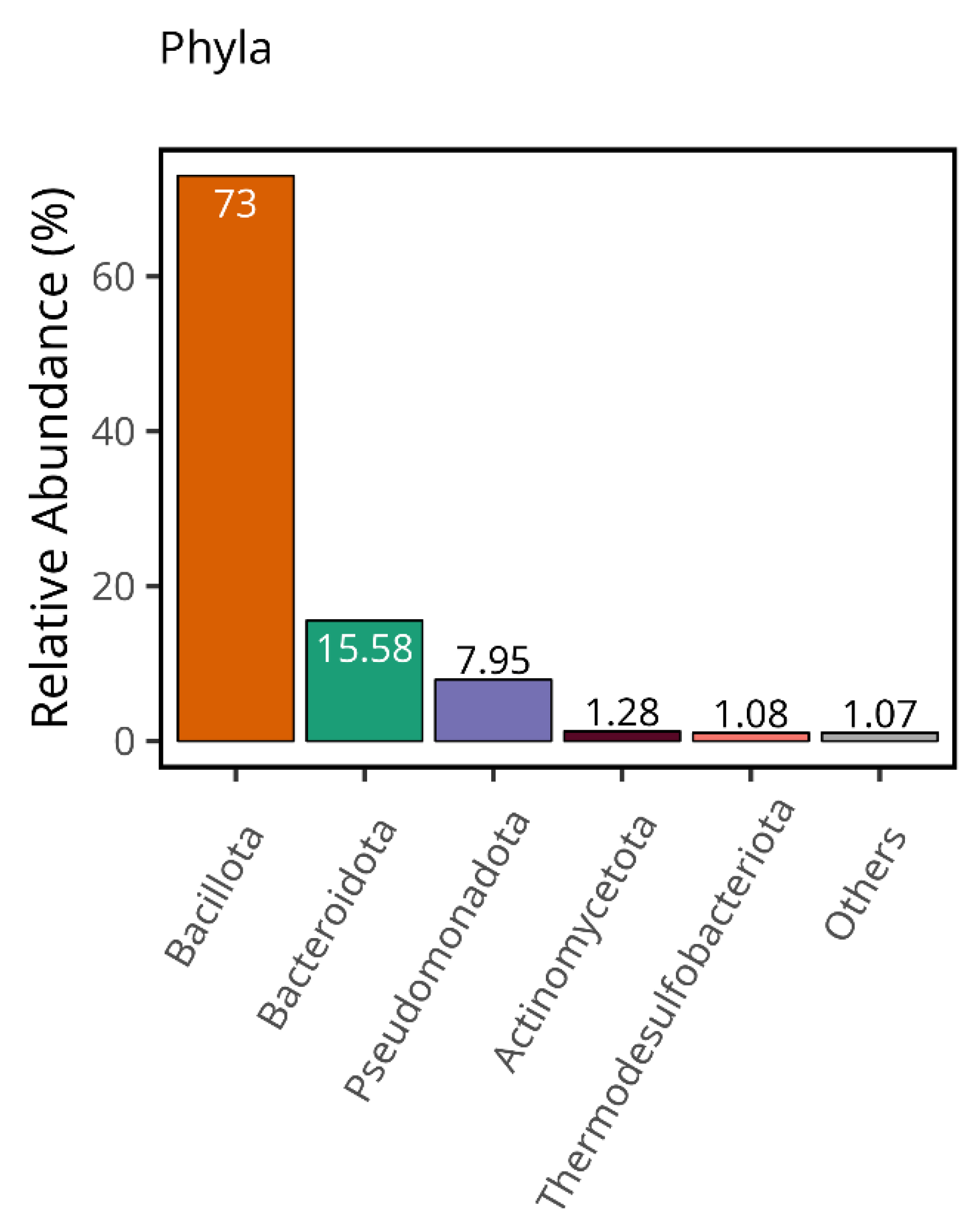

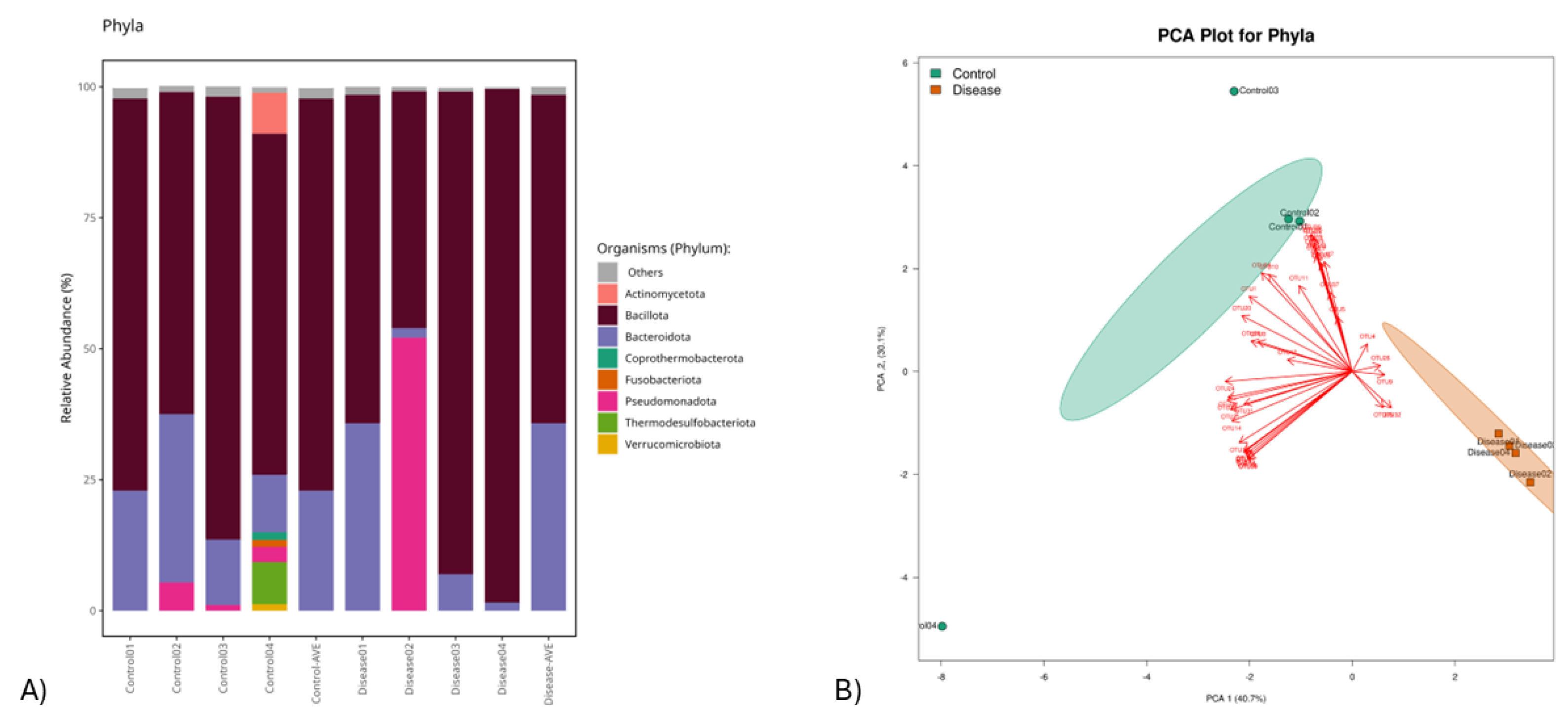

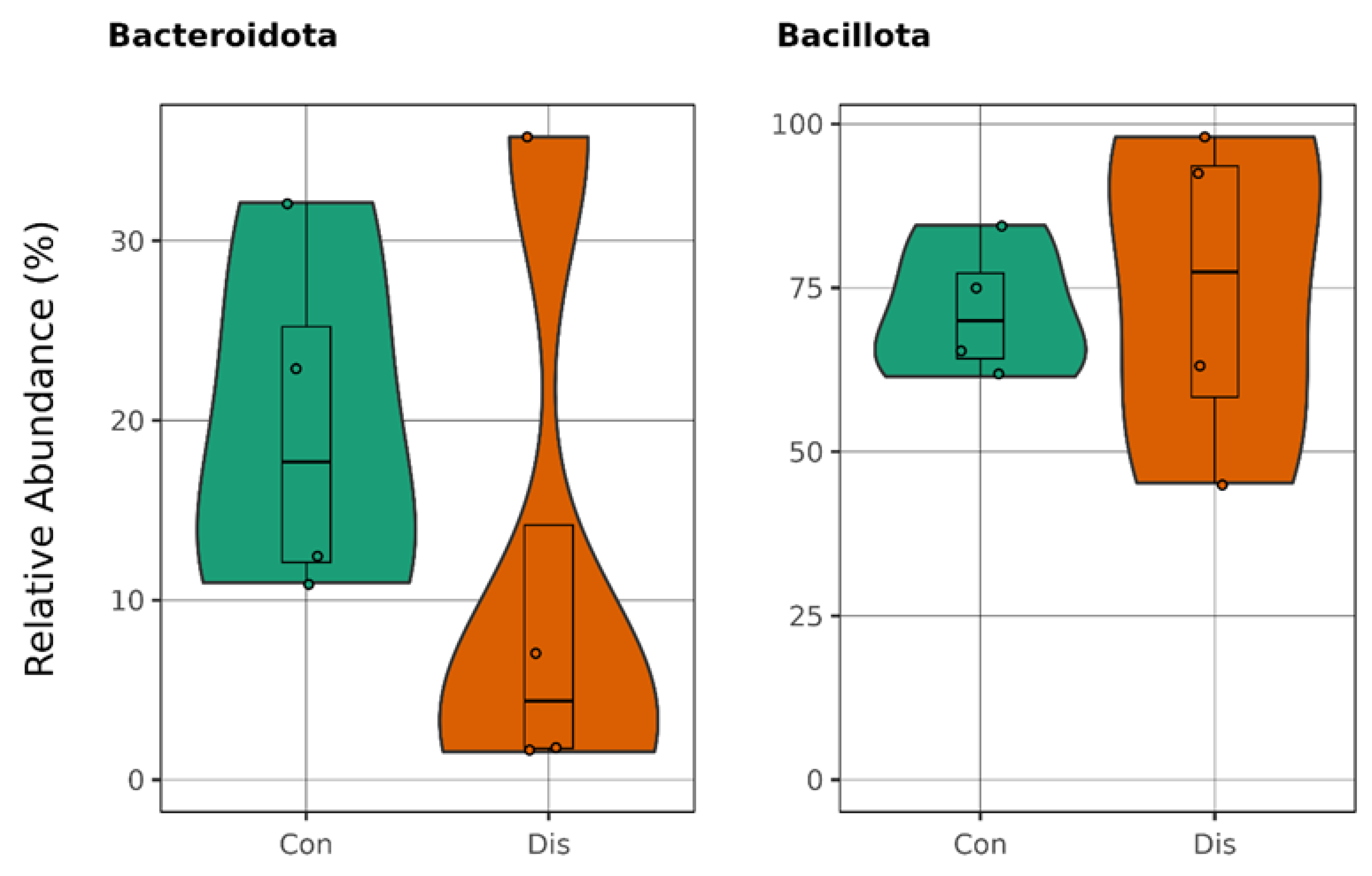

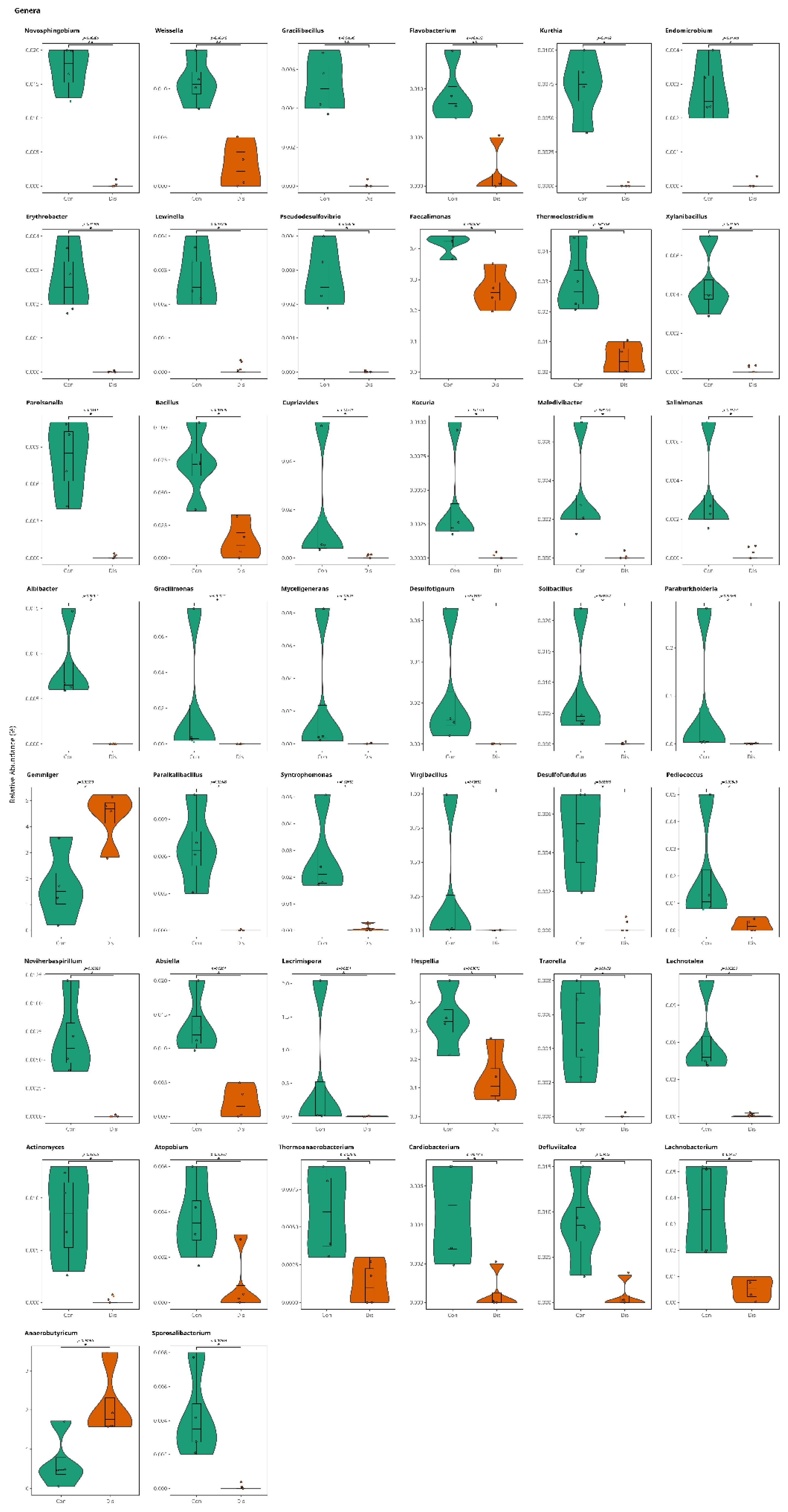

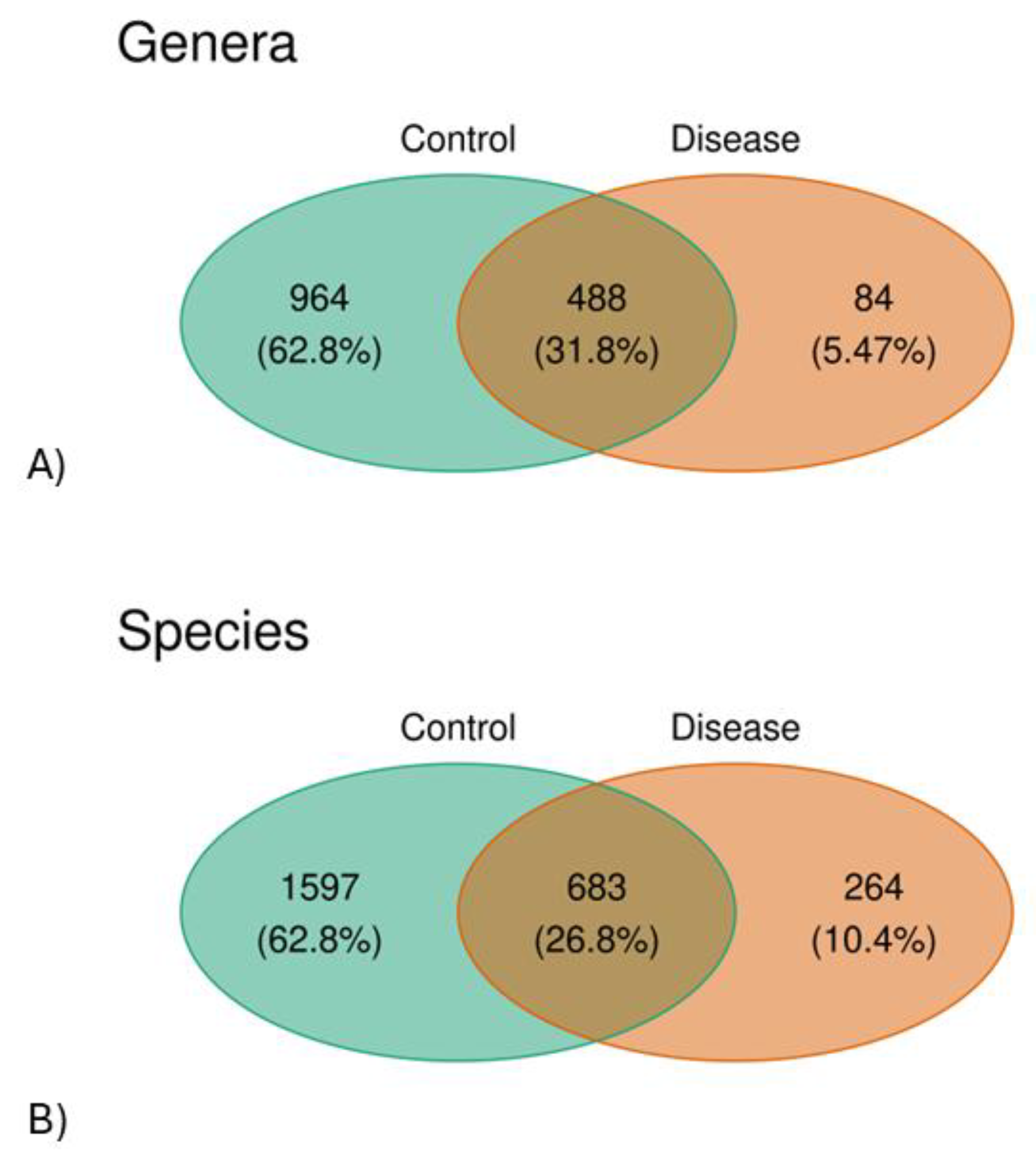

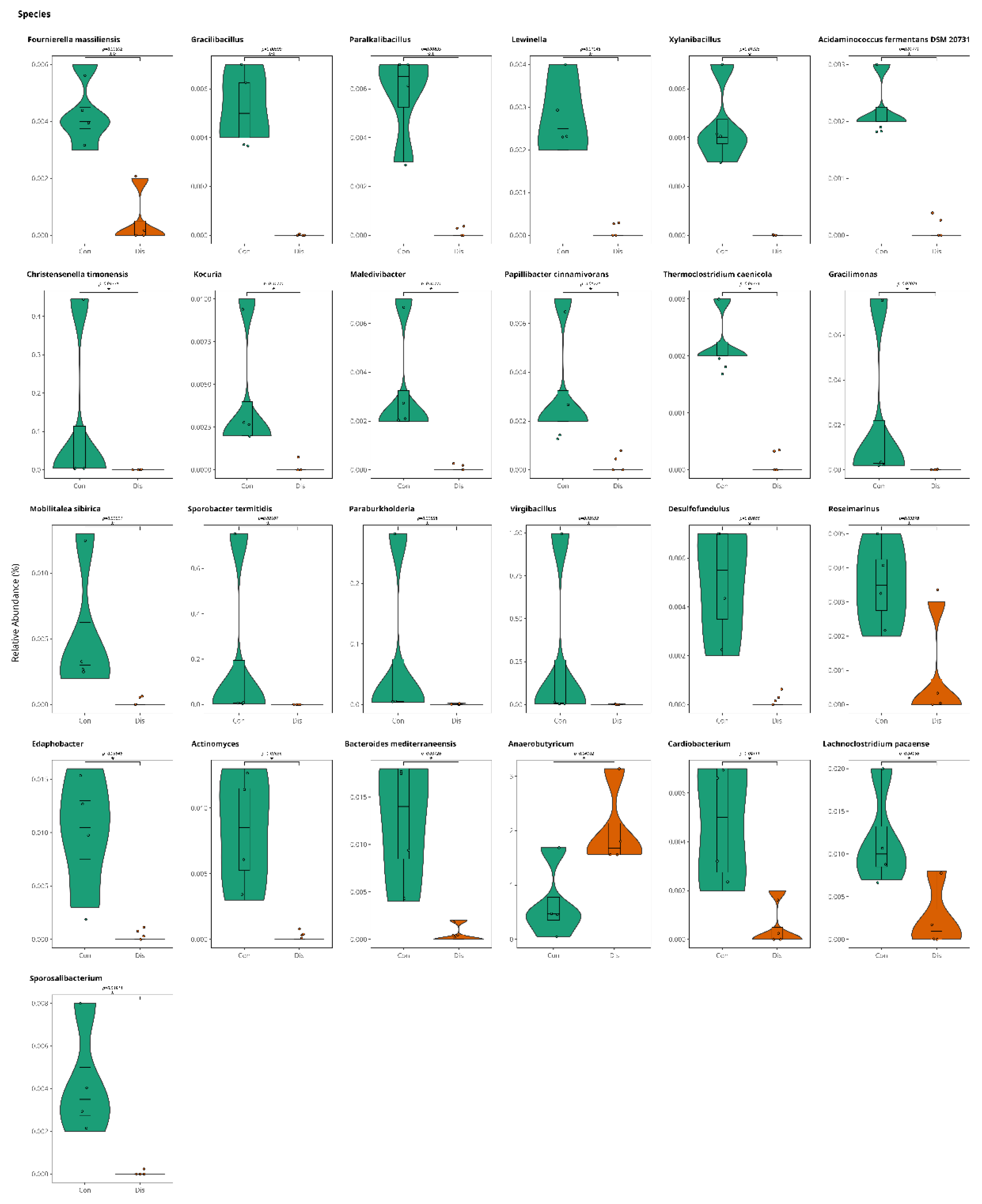

3.1. This Gut Microbiota Differences Between CSFP Patients and Control

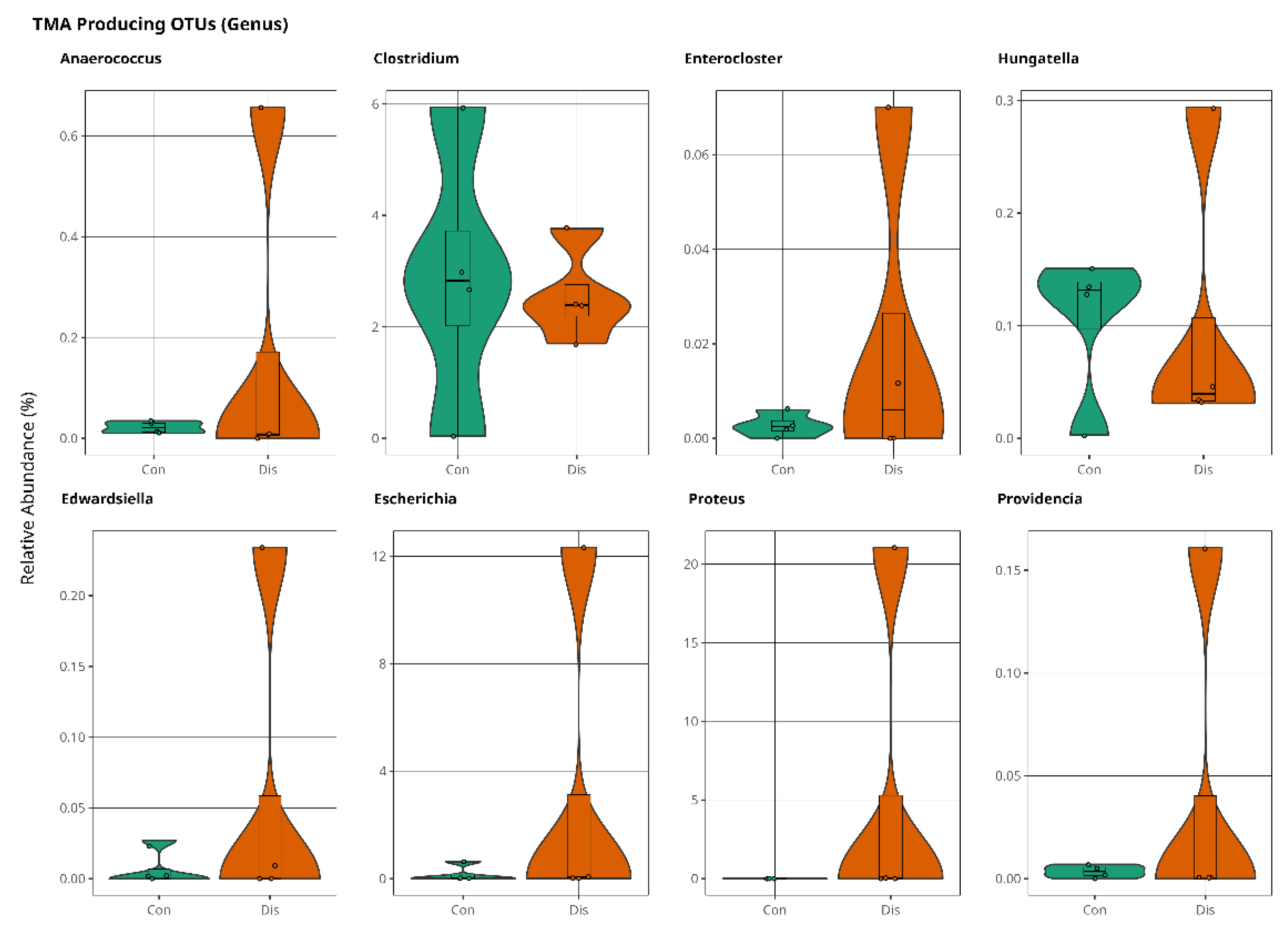

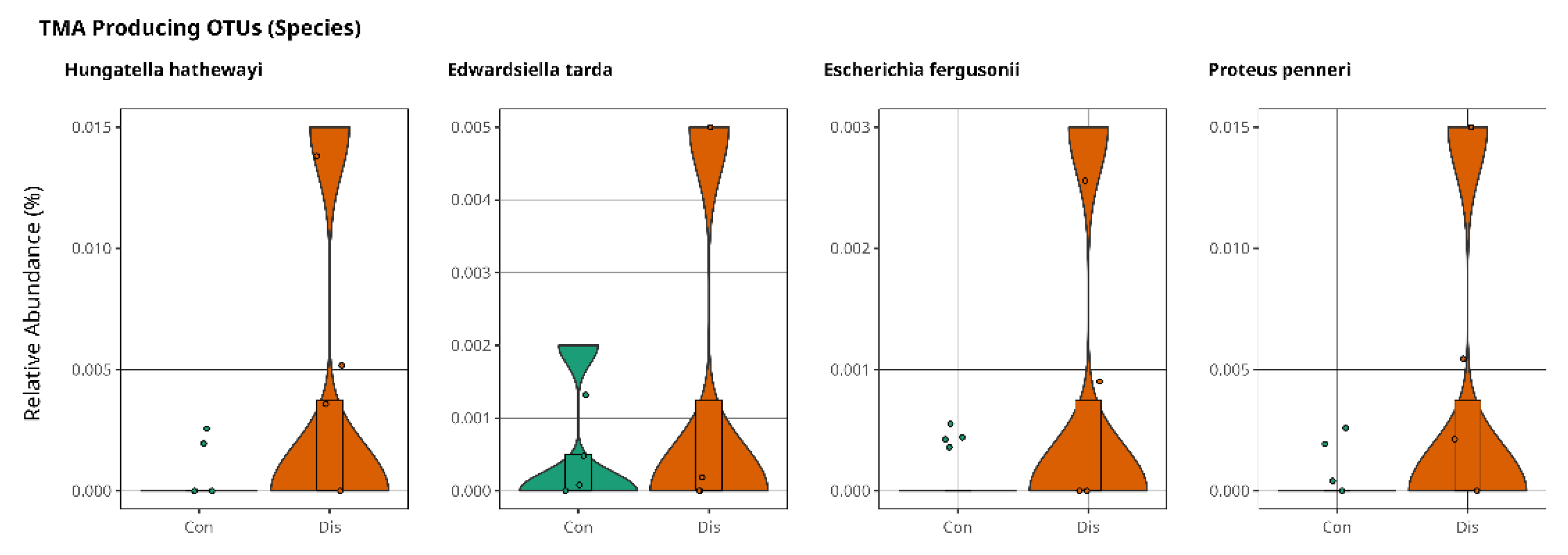

3.2. Trimethylamine Produced from Microbial Organisms and Its Potential Effect on CSFP Disease

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CSFP | Coronary Slow Flow Phenomenon |

| TMA | Trimethylamine |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| TSS | Total Sum Scaling |

| TMAO | Trimethyl-N-Oxide |

References

- Alvarez, C.; Siu, H. Coronary Slow-Flow Phenomenon as an Underrecognized and Treatable Source of Chest Pain: Case Series and Literature Review. J. Investig. Med. High Impact Case Rep. 2018, 6, 2324709618789194. [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, B. M.; Stavrakis, S.; Rousan, T. A.; Abu-Fadel, M.; Schechter, E. Coronary Slow Flow: – Prevalence and Clinical Correlations –. Circ. J. 2012, 76 (4), 936–942. [CrossRef]

- Vane JR, Botting RM. Secretory functions of the vascular endothelium. J Physiol Pharmacol. 1992 Sep;43(3):195-207. [PubMed]

- Hadi HA, Carr CS, Al Suwaidi J. Endothelial dysfunction: cardiovascular risk factors, therapy, and outcome. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2005;1(3):183-98. [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fosse, J. H.; Haraldsen, G.; Falk, K.; Edelmann, R. Endothelial Cells in Emerging Viral Infections. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 619690. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z. Gut Microbiome and Cardiovascular Disease. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2020, 35 (3), 207–218. [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Ye, L.; Li, J.; Jin, L.; Wang, W.; Li, S.; Bao, M.; Wu, S.; Li, L.; Geng, B.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, J.; Cai, J. Metagenomic and Metabolomic Analyses Unveil Dysbiosis of Gut Microbiota in Chronic Heart Failure Patients. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8 (1), 635. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhao, F.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Tao, J.; Tian, G.; Wu, S.; Liu, W.; Cui, Q.; Geng, B.; Zhang, W.; Weldon, R.; Auguste, K.; Yang, L.; Liu, X.; Chen, L.; Yang, X.; Zhu, B.; Cai, J. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis Contributes to the Development of Hypertension. Microbiome 2017, 5 (1), 14. [CrossRef]

- Jie, Z.; Xia, H.; Zhong, S.-L.; Feng, Q.; Li, S.; Liang, S.; Zhong, H.; Liu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, D.; Su, Z.; Fang, Z.; Lan, Z.; Li, J.; Xiao, L.; Li, J.; Li, R.; Li, X.; Li, F.; Ren, H.; Huang, Y.; Peng, Y.; Li, G.; Wen, B.; Dong, B.; Chen, J.-Y.; Geng, Q.-S.; Zhang, Z.-W.; Yang, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Madsen, L.; Brix, S.; Ning, G.; Xu, X.; Liu, X.; Hou, Y.; Jia, H.; He, K.; Kristiansen, K. The Gut Microbiome in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8 (1), 845. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Nie, S.-P. The Coronary Slow Flow Phenomenon: Characteristics, Mechanisms and Implications. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2011, 1 (1).

- Mangieri, E.; Macchiarelli, G.; Ciavolella, M.; Barillà, F.; Avella, A.; Martinotti, A.; Dell’Italia, L. J.; Scibilia, G.; Motta, P.; Campa, P. P. Slow Coronary Flow: Clinical and Histopathological Features in Patients with Otherwise Normal Epicardial Coronary Arteries. Cathet. Cardiovasc. Diagn. 1996, 37 (4), 375–381. [CrossRef]

- Beltrame, J. F.; Limaye, S. B.; Horowitz, J. D. The Coronary Slow Flow Phenomenon – A New Coronary Microvascular Disorder. Cardiology 2002, 97 (4), 197–202. [CrossRef]

- Goel, P. K.; Gupta, S. K.; Agarwal, A.; Kapoor, A. Slow Coronary Flow: A Distinct Angiographic Subgroup in Syndrome X. Angiology 2001, 52 (8), 507–514. [CrossRef]

- Tambe, A. A.; Demany, M. A.; Zimmermcln, H. A.; Muscnrenhns, E.; Ohio, C. Angina Pectoris and Slow Flow Velocity of Dye in Coronary Arteries-A New Angiograpbic Finding.

- Saya, S.; Hennebry, T. A.; Lozano, P.; Lazzara, R.; Schechter, E. Coronary Slow Flow Phenomenon and Risk for Sudden Cardiac Death Due to Ventricular Arrhythmias: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Clin. Cardiol. 2008, 31 (8), 352–355. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2013.

- Shi, X.-R.; Chen, B.-Y.; Lin, W.-Z.; Li, Y.-L.; Wang, Y.-L.; Liu, Y.; Huang, J.-J.; Zhang, W.-W.; Ma, X.-X.; Shao, S.; Li, R.-G.; Duan, S.-Z. Microbiota in Gut, Oral Cavity, and Mitral Valves Are Associated With Rheumatic Heart Disease. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 643092. [CrossRef]

- Amiri, P.; Hosseini, S. A.; Ghaffari, S.; Tutunchi, H.; Ghaffari, S.; Mosharkesh, E.; Asghari, S.; Roshanravan, N. Role of Butyrate, a Gut Microbiota Derived Metabolite, in Cardiovascular Diseases: A Comprehensive Narrative Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 12, 837509. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M. S.; Fernandez, M. L. Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO), Diet and Cardiovascular Disease. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2021, 23 (4), 12. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dai, M. Trimethylamine N-Oxide Generated by the Gut Microbiota Is Associated with Vascular Inflammation: New Insights into Atherosclerosis. Mediators Inflamm. 2020, 2020, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; He, J.-Q. Pathogenic Mechanisms of Trimethylamine N-Oxide-Induced Atherosclerosis and Cardiomyopathy. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2022, 20 (1), 29–36. [CrossRef]

- Rath, S.; Rud, T.; Pieper, D. H.; Vital, M. Potential TMA-Producing Bacteria Are Ubiquitously Found in Mammalia. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 2966. [CrossRef]

- Rath, S.; Heidrich, B.; Pieper, D. H.; Vital, M. Uncovering the Trimethylamine-Producing Bacteria of the Human Gut Microbiota. Microbiome 2017, 5 (1), 54. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, Md. M.; Islam, F.; -Or-Rashid, Md. H.; Mamun, A. A.; Rahaman, Md. S.; Islam, Md. M.; Meem, A. F. K.; Sutradhar, P. R.; Mitra, S.; Mimi, A. A.; Emran, T. B.; Fatimawali; Idroes, R.; Tallei, T. E.; Ahmed, M.; Cavalu, S. The Gut Microbiota (Microbiome) in Cardiovascular Disease and Its Therapeutic Regulation. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 903570. [CrossRef]

- Sawicka-Smiarowska, E.; Bondarczuk, K.; Bauer, W.; Niemira, M.; Szalkowska, A.; Raczkowska, J.; Kwasniewski, M.; Tarasiuk, E.; Dubatowka, M.; Lapinska, M.; Szpakowicz, M.; Stachurska, Z.; Szpakowicz, A.; Sowa, P.; Raczkowski, A.; Kondraciuk, M.; Gierej, M.; Motyka, J.; Jamiolkowski, J.; Bondarczuk, M.; Chlabicz, M.; Bucko, J.; Kozuch, M.; Dobrzycki, S.; Bychowski, J.; Musial, W. J.; Godlewski, A.; Ciborowski, M.; Gyenesei, A.; Kretowski, A.; Kaminski, K. A. Gut Microbiome in Chronic Coronary Syndrome Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10 (21), 5074. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Tang, Y.; Zhan, Q.; Lai, W.; Ao, L.; Meng, X.; Ren, H.; Xu, D.; Zeng, Q. The Intestinal Microbiota Associated with Cardiac Valve Calcification Differs from That of Coronary Artery Disease. Atherosclerosis 2019, 284, 121–128. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A. F.; Dwivedi, G.; O’Gara, F.; Caparros-Martin, J.; Ward, N. C. The Gut Microbiome and Cardiovascular Disease: Current Knowledge and Clinical Potential. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2019, 317 (5), H923–H938. [CrossRef]

- Astudillo, A. A.; Mayrovitz, H. N. The Gut Microbiome and Cardiovascular Disease. Cureus 2021. [CrossRef]

- Toya, T.; Corban, M. T.; Marrietta, E.; Horwath, I. E.; Lerman, L. O.; Murray, J. A.; Lerman, A. Coronary Artery Disease Is Associated with an Altered Gut Microbiome Composition. PLOS ONE 2020, 15 (1), e0227147. [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, N.; Yamashita, T.; Hirata, K. Gut Microbiome and Cardiovascular Diseases. Diseases 2018, 6 (3), 56. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, X.; Hu, X.; Niu, H.; Tian, R.; Wang, H.; Pang, H.; Jiang, L.; Qiu, B.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Tang, S.; Li, H.; Feng, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, C. Alterations in the Gut Microbiome and Metabolism with Coronary Artery Disease Severity. Microbiome 2019, 7 (1), 68. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R. L. U.; Sena-Evangelista, K. C. M.; De Azevedo, E. P.; Pinheiro, F. I.; Cobucci, R. N.; Pedrosa, L. F. C. Selenium in Human Health and Gut Microflora: Bioavailability of Selenocompounds and Relationship With Diseases. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 685317. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Meng, S.; Yu, Y.; Bi, L.; Tian, J.; Zhang, L. Associations of Dietary Selenium Intake with the Risk of Chronic Diseases and Mortality in US Adults. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1363299. [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Su, W.; Chen, X.; Zheng, H. Advances in the Study of Selenium and Human Intestinal Bacteria. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1059358. [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y. J.; Gan, H. Y.; Li, X.; Huang, Y.; Li, Z. C.; Deng, H. M.; Chen, S. Z.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, L. S.; Han, Y. P.; Tan, Y. F.; Song, Y. J.; Du, Z. M.; Liu, Y. Y.; Wang, Y.; Qin, N.; Bai, Y.; Yang, R. F.; Bi, Y. J.; Zhi, F. C. Correlation of Diet, Microbiota and Metabolite Networks in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Dig. Dis. 2019, 20 (9), 447–459. [CrossRef]

- Koh, A.; De Vadder, F.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Bäckhed, F. From Dietary Fiber to Host Physiology: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Bacterial Metabolites. Cell 2016, 165 (6), 1332–1345. [CrossRef]

- Flores-Mateo, G.; Navas-Acien, A.; Pastor-Barriuso, R.; Guallar, E. Selenium and Coronary Heart Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 84 (4), 762–773. [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Wu, Q.; Yao, Q.; Jiang, K.; Yu, J.; Tang, Q. Short-Chain Fatty Acid Metabolism and Multiple Effects on Cardiovascular Diseases. Ageing Res. Rev. 2022, 81, 101706. [CrossRef]

- Modrego, J.; Ortega-Hernández, A.; Goirigolzarri, J.; Restrepo-Córdoba, M. A.; Bäuerl, C.; Cortés-Macías, E.; Sánchez-González, S.; Esteban-Fernández, A.; Pérez-Villacastín, J.; Collado, M. C.; Gómez-Garre, D. Gut Microbiota and Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids Are Linked to Evolution of Heart Failure Patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24 (18), 13892. [CrossRef]

- Canyelles, M.; Borràs, C.; Rotllan, N.; Tondo, M.; Escolà-Gil, J. C.; Blanco-Vaca, F. Gut Microbiota-Derived TMAO: A Causal Factor Promoting Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24 (3), 1940. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; He, J.-Q. Pathogenic Mechanisms of Trimethylamine N-Oxide-Induced Atherosclerosis and Cardiomyopathy. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2022, 20 (1), 29–36. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ke, B.; Du, J. TMAO: How Gut Microbiota Contributes to Heart Failure. Transl. Res. 2021, 228, 109–125. [CrossRef]

- Rath, S.; Heidrich, B.; Pieper, D. H.; Vital, M. Uncovering the Trimethylamine-Producing Bacteria of the Human Gut Microbiota. Microbiome 2017, 5 (1), 54. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-C.; Liu, Y.-W.; Chang, K.-C.; Wu, Y.-W.; Chen, Y.-M.; Chao, Y.-K.; You, M.-Y.; Lundy, D. J.; Lin, C.-J.; Hsieh, M. L.; Cheng, Y.-C.; Prajnamitra, R. P.; Lin, P.-J.; Ruan, S.-C.; Chen, D. H.-K.; Shih, E. S. C.; Chen, K.-W.; Chang, S.-S.; Chang, C. M. C.; Puntney, R.; Moy, A. W.; Cheng, Y.-Y.; Chien, H.-Y.; Lee, J.-J.; Wu, D.-C.; Hwang, M.-J.; Coonen, J.; Hacker, T. A.; Yen, C.-L. E.; Rey, F. E.; Kamp, T. J.; Hsieh, P. C. H. Gut Butyrate-Producers Confer Post-Infarction Cardiac Protection. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14 (1), 7249. [CrossRef]

- Shimada, B. K.; Alfulaij, N.; Seale, L. A. The Impact of Selenium Deficiency on Cardiovascular Function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22 (19), 10713. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zeng, Q.; Liu, X.; He, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, S.; Hu, H. Association of Blood Selenium Levels with Diabetes and Heart Failure in American General Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study of NHANES 2011–2020 Pre. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2024, 202 (8), 3413–3424. [CrossRef]

- Leszto, K.; Biskup, L.; Korona, K.; Marcinkowska, W.; Możdżan, M.; Węgiel, A.; Młynarska, E.; Rysz, J.; Franczyk, B. Selenium as a Modulator of Redox Reactions in the Prevention and Treatment of Cardiovascular Diseases. Antioxidants 2024, 13 (6), 688. [CrossRef]

- Jaworska, K.; Hering, D.; Mosieniak, G.; Bielak-Zmijewska, A.; Pilz, M.; Konwerski, M.; Gasecka, A.; Kapłon-Cieślicka, A.; Filipiak, K.; Sikora, E.; Hołyst, R.; Ufnal, M. TMA, A Forgotten Uremic Toxin, but Not TMAO, Is Involved in Cardiovascular Pathology. Toxins 2019, 11 (9), 490. [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Jiang, H.; Zhuo, C.; Jiang, W. Trimethylamine/Trimethylamine-N-Oxide as a Key Between Diet and Cardiovascular Diseases. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2021, 21 (8), 593–604. [CrossRef]

- Roncal, C.; Martínez-Aguilar, E.; Orbe, J.; Ravassa, S.; Fernandez-Montero, A.; De Pipaon, G. S.; Ugarte, A.; Estella-Hermoso De Mendoza, A.; Rodriguez, J. A.; Fernández-Alonso, S.; Fernández-Alonso, L.; Oyarzabal, J.; Paramo, J. A. Trimethylamine (Tma) And Trimethylamine-N-Oxide (Tmao) As Predictors Of Cardiovascular Mortality In Peripheral Artery Disease. Atherosclerosis 2019, 287, e233. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Chen, S.; Xue, Y.; Lu, H.; Li, Z.; Jia, X.; Ning, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Wang, S. Analysis of Alterations in Intestinal Flora in Chinese Elderly with Cardiovascular Disease and Its Association with Trimethylamine. Nutrients 2024, 16 (12), 1864. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).