Submitted:

07 September 2025

Posted:

09 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

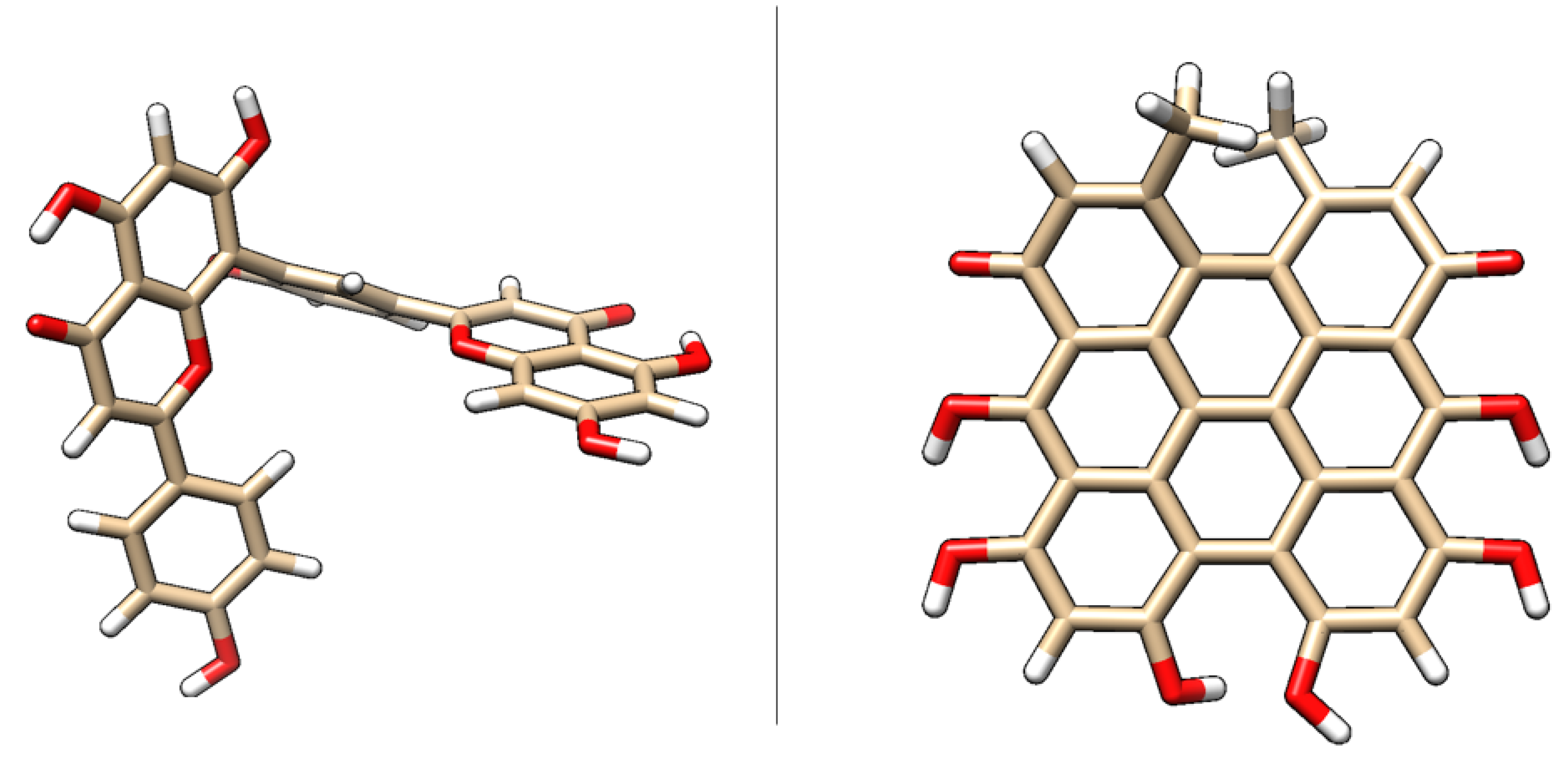

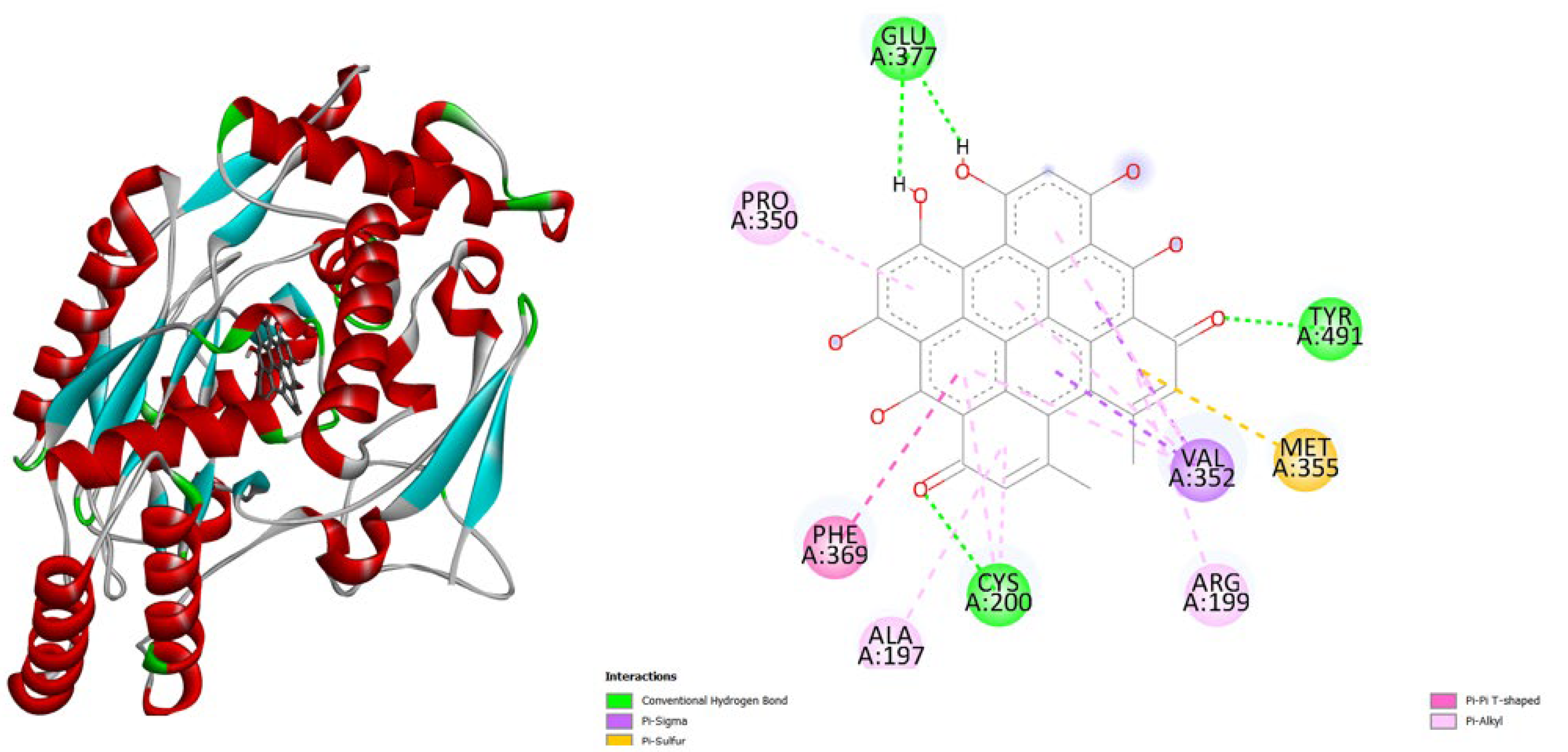

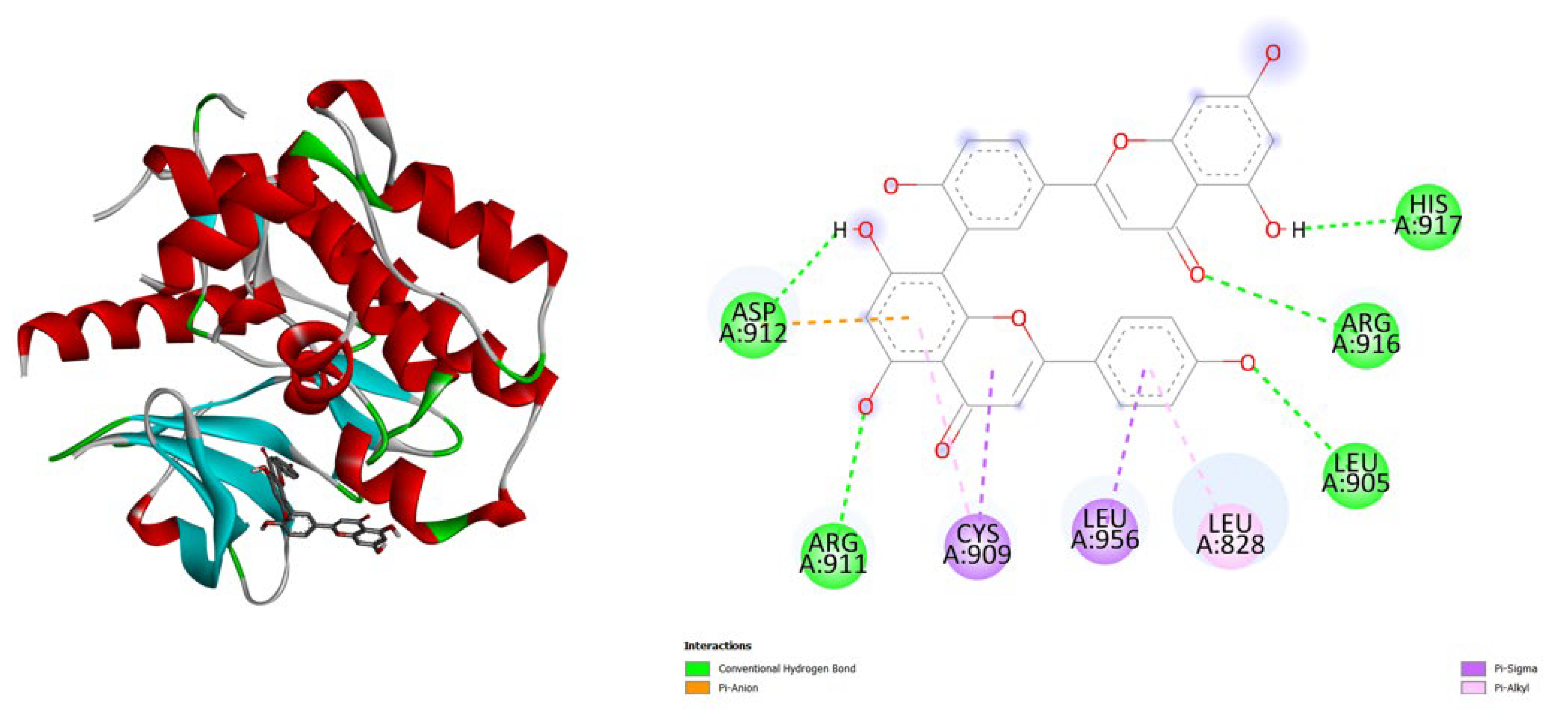

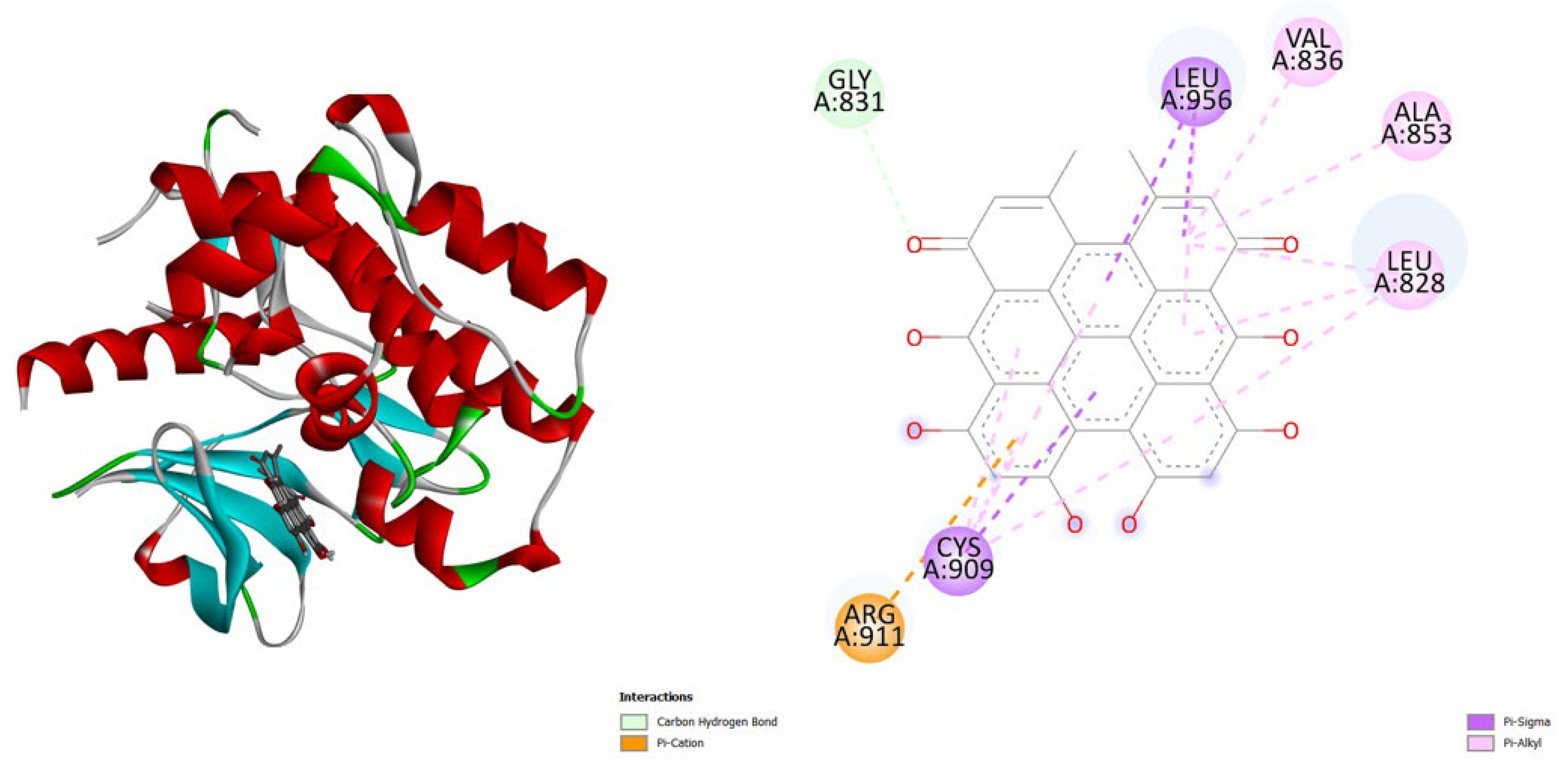

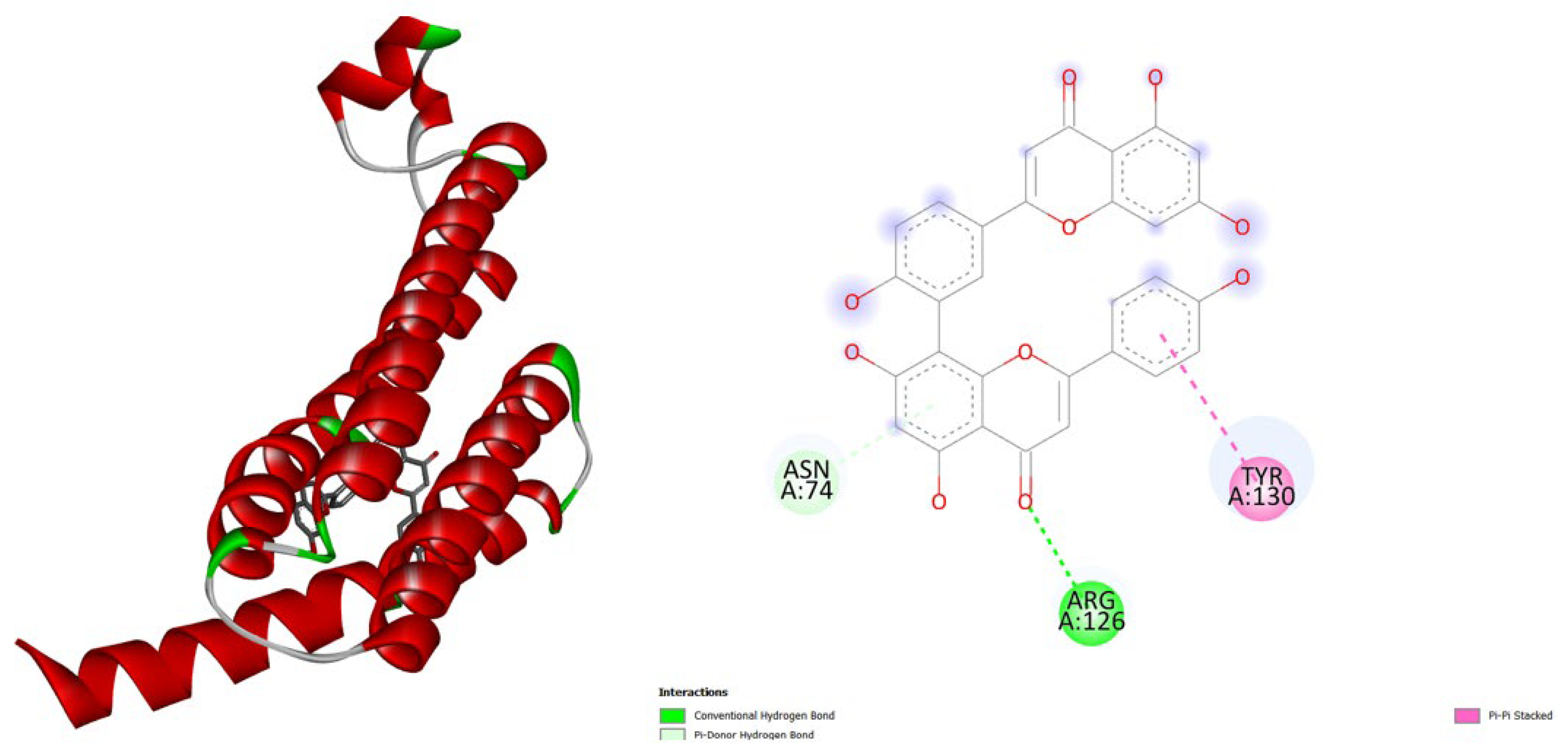

Multiple signaling pathways, including cytokine regulation, nitric oxide production, and prostaglandin biosynthesis, drive chronic inflammation. Natural polyphenolic compounds are promising therapeutic candidates due to their multitarget potential and favorable safety profiles. Here, we performed molecular docking of amentoflavone and hypericin against key inflammatory targets: TNF-α (PDB: 2AZ5), inducible nitric oxide synthase – iNOS (PDB: 3E7G), tyrosine-protein kinase JAK3 (PDB: 6HZV), prostaglandin E synthase (PDB: 4AL1), and prostaglandin reductase 3 (PDB: 7ZEJ). Both compounds exhibited strong binding affinities, in several cases surpassing native ligands. Amentoflavone showed the highest affinity for iNOS and prostaglandin reductase, while hypericin strongly targeted JAK3 and TNF-α. Overall, both natural products demonstrate the ability to bind with higher affinity and potentially greater stability than the native ligands, making them promising candidates for further experimental validation. Our findings suggest that Amentoflavone and Hypericin are potential multi-target anti-inflammatory agents that could serve as natural therapeutic options for chronic inflammatory diseases, although further in vitro and in vivo studies are required.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Computational Methods

Protein Targets

- TNF-α (PDB: 2AZ5)

- iNOS (PDB: 3E7G)

- JAK3 (PDB: 6HZV)

- Prostaglandin E synthase (PDB: 4AL1)

- Prostaglandin reductase 3 (PDB: 7ZEJ)

Docking Protocol

Ligand Preparation

Center Grid Box Settings for AutoDock Vina Using PyRx

- Center Coordinates: X = -18.7515057672, Y = 74.8086603805, Z = 34.290280357

- Grid Box Size: X = 18.920029768, Y = 17.3964637205, Z = 20.1995711195

- Exhaustiveness: 8

- Center Coordinates: X = 55.4997858867, Y = 21.4642422109, Z = 78.9058415436

- Grid Box Size: X = 19.4004780461, Y = 19.4004780461, Z = 19.4004780461

- Exhaustiveness: 8

- Center Coordinates: X = 10.2267815987, Y = 25.1838265236, Z = 3.38777306213

- Grid Box Size: X = 18.8755088683, Y = 20.0250877888, Z = 16.9945448487

- Exhaustiveness: 8

- Center Coordinates: X = 55.4997858867, Y = 21.4642422109, Z = 78.9058415436

- Grid Box Size: X = 19.4004780461, Y = 19.4004780461, Z = 19.4004780461

- Exhaustiveness: 8

- Grid Box Size: X = 15.6470506825, Y = 15.6470506825, Z = 15.6470506825

- Exhaustiveness: 8

- Grid Box Size: X = 17.7910383025, Y = 17.8825350772, Z = 17.8825350772

- Exhaustiveness: 8

3. Results and Discussion

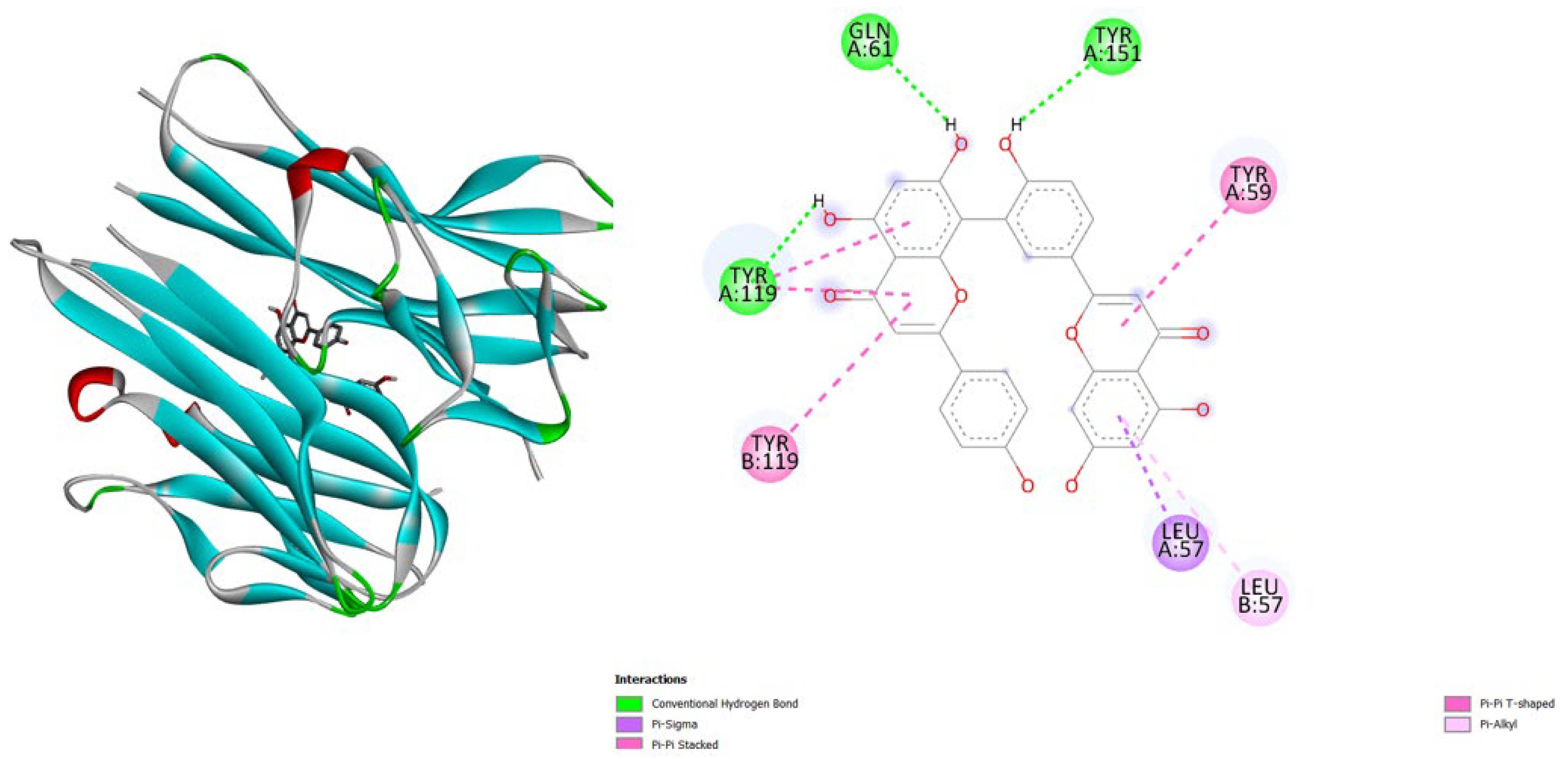

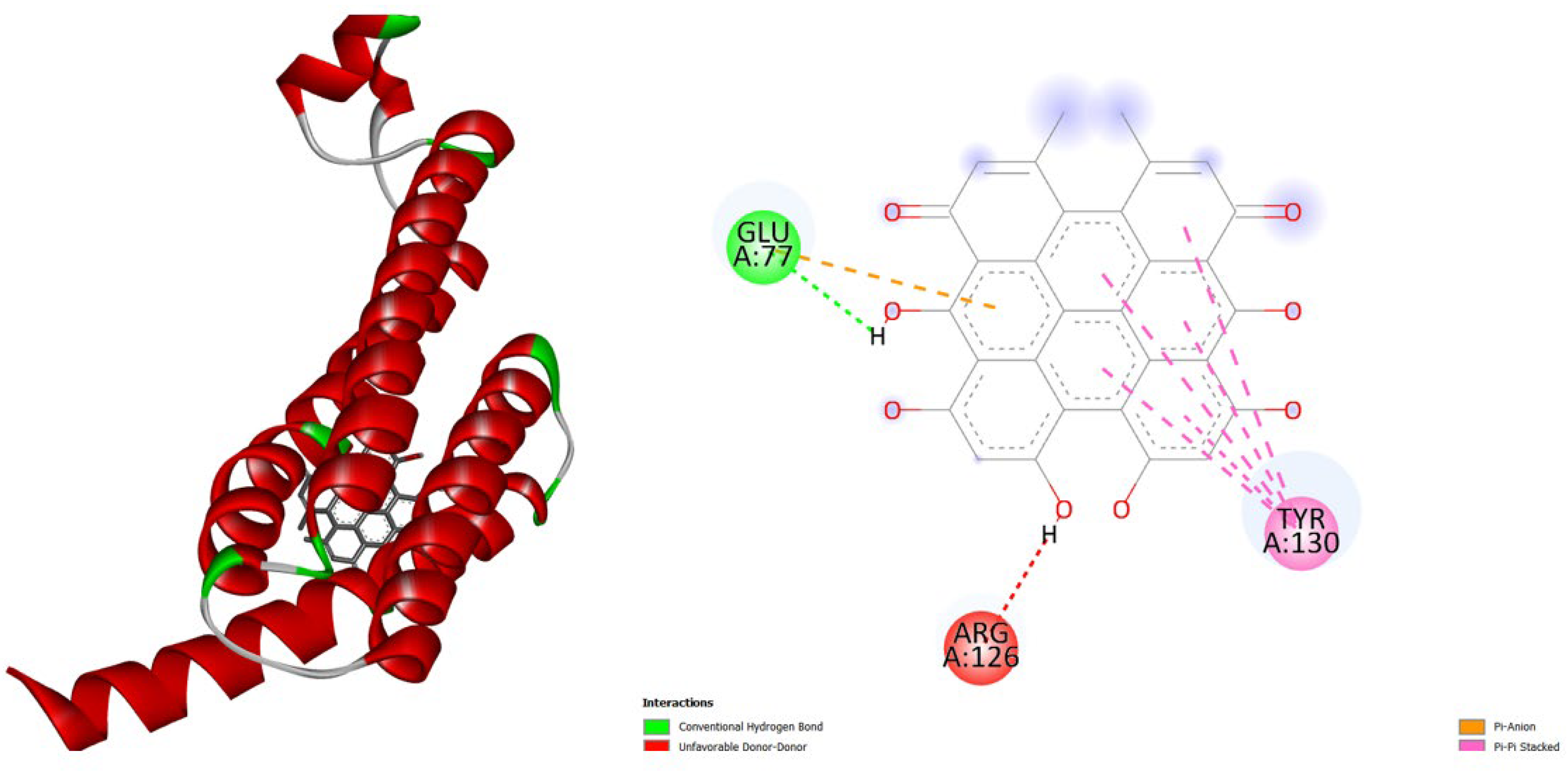

- TNF-α (2AZ5): Hypericin binds slightly stronger (-9.9) than Amentoflavone (-9.5) and both outperform the native ligand (-8.8).

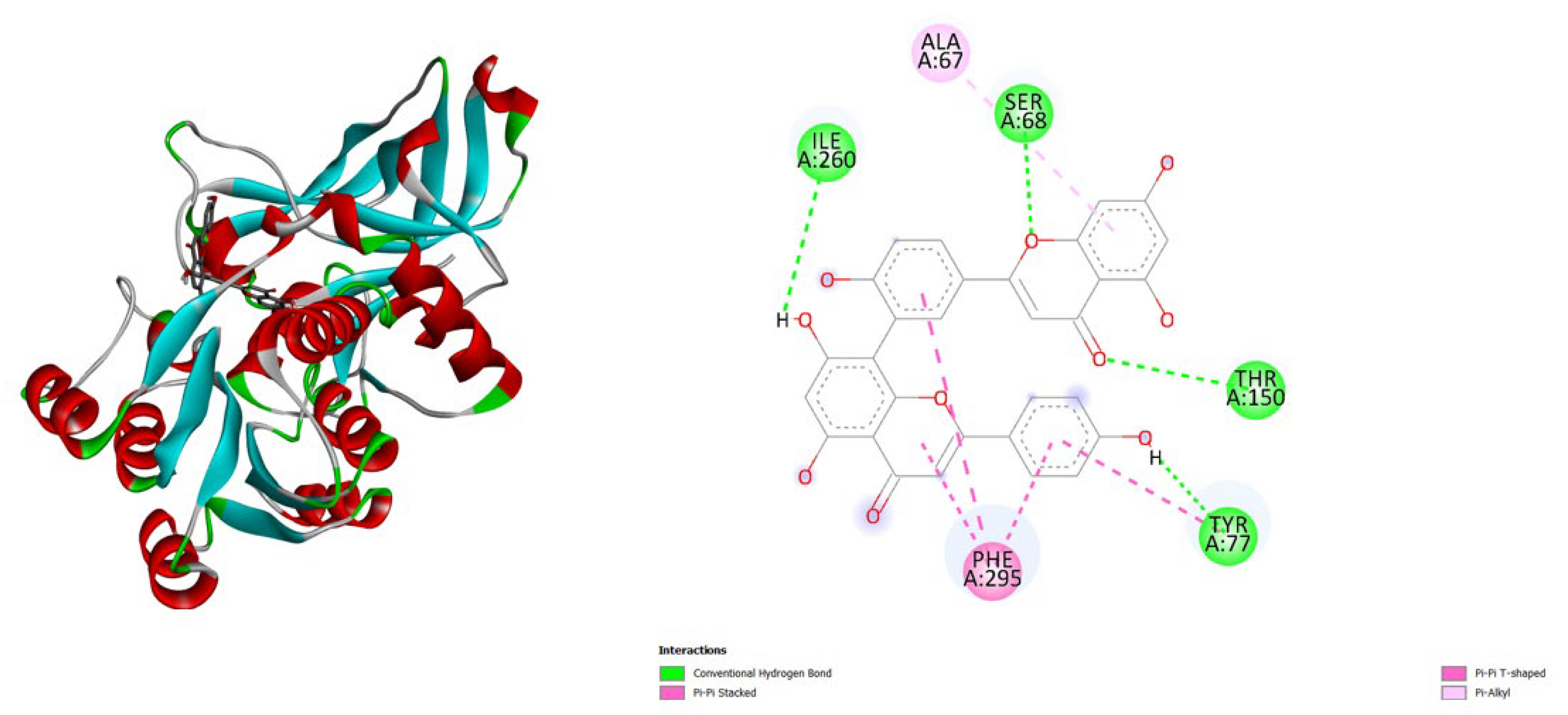

- iNOS (3E7G): Amentoflavone shows the strongest binding (-11.3), followed by Hypericin (-10.4), both much better than the native ligand (-6.9).

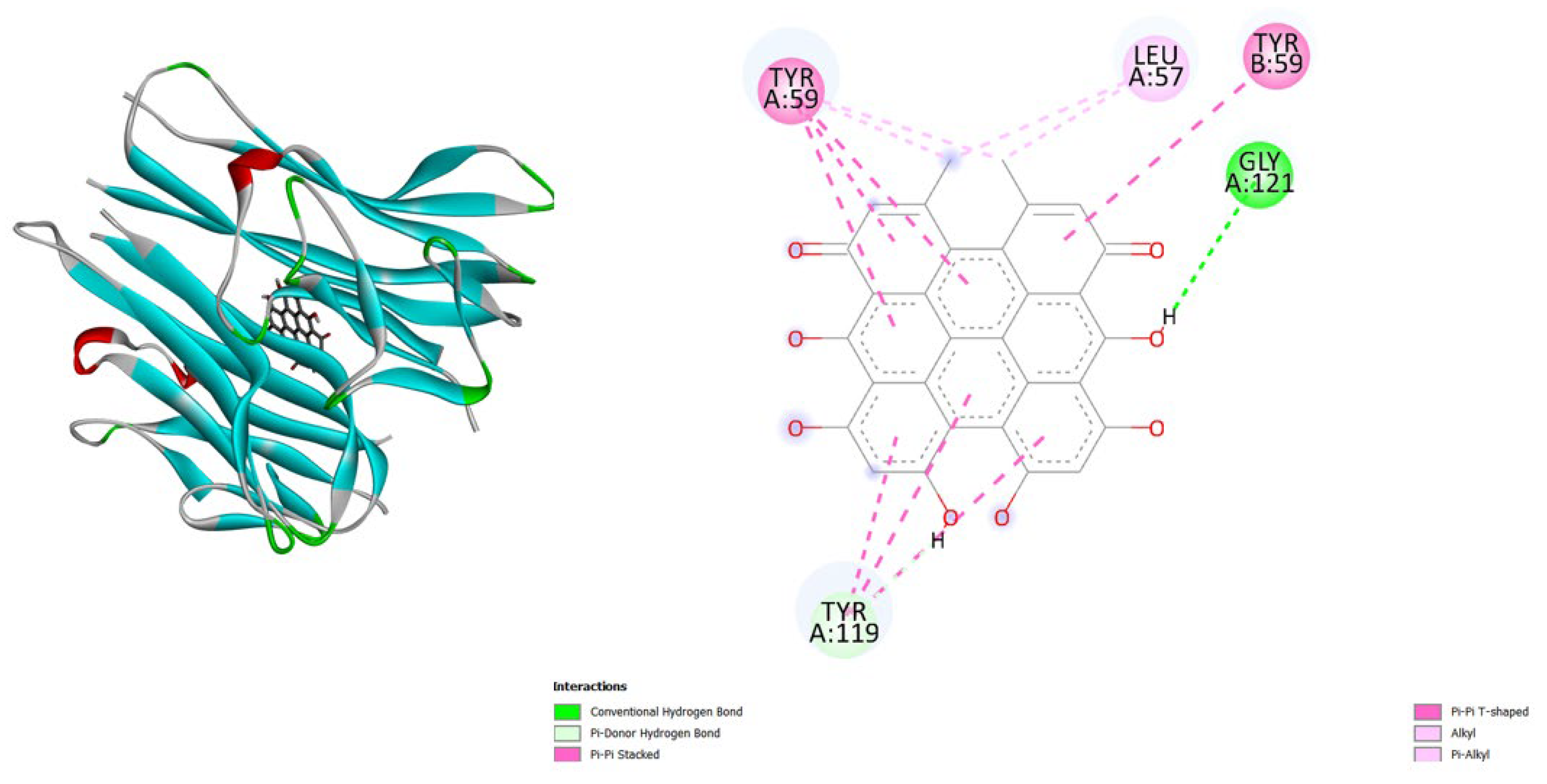

- JAK3 (6HZV): Hypericin has the strongest predicted affinity (-11.4), surpassing Amentoflavone (-9.5) and the native ligand (-9.2).

- PGE synthase (4AL1): Amentoflavone (-7.7) binds slightly better than Hypericin (-7.1), both stronger than the native ligand (-5.9).

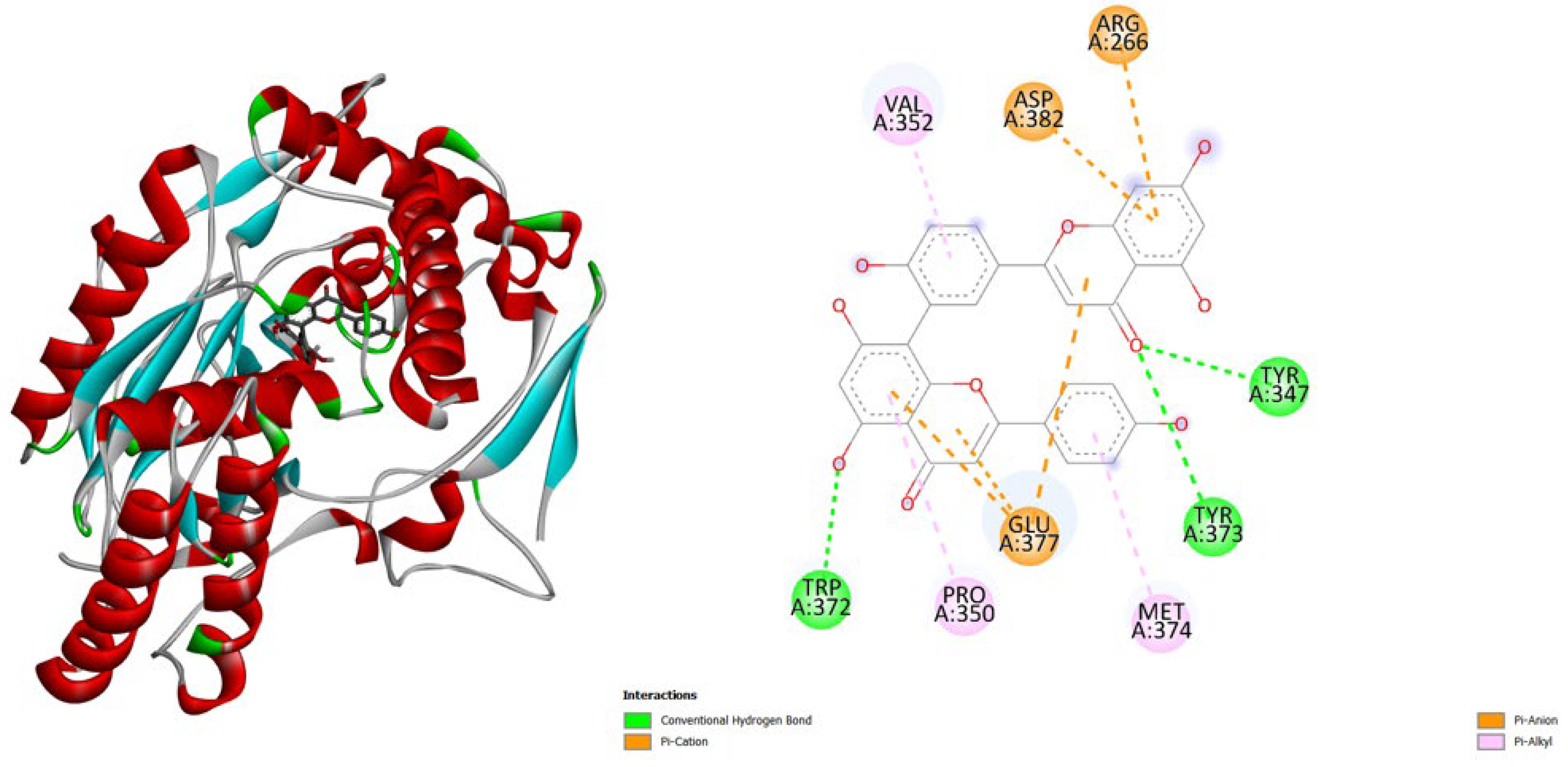

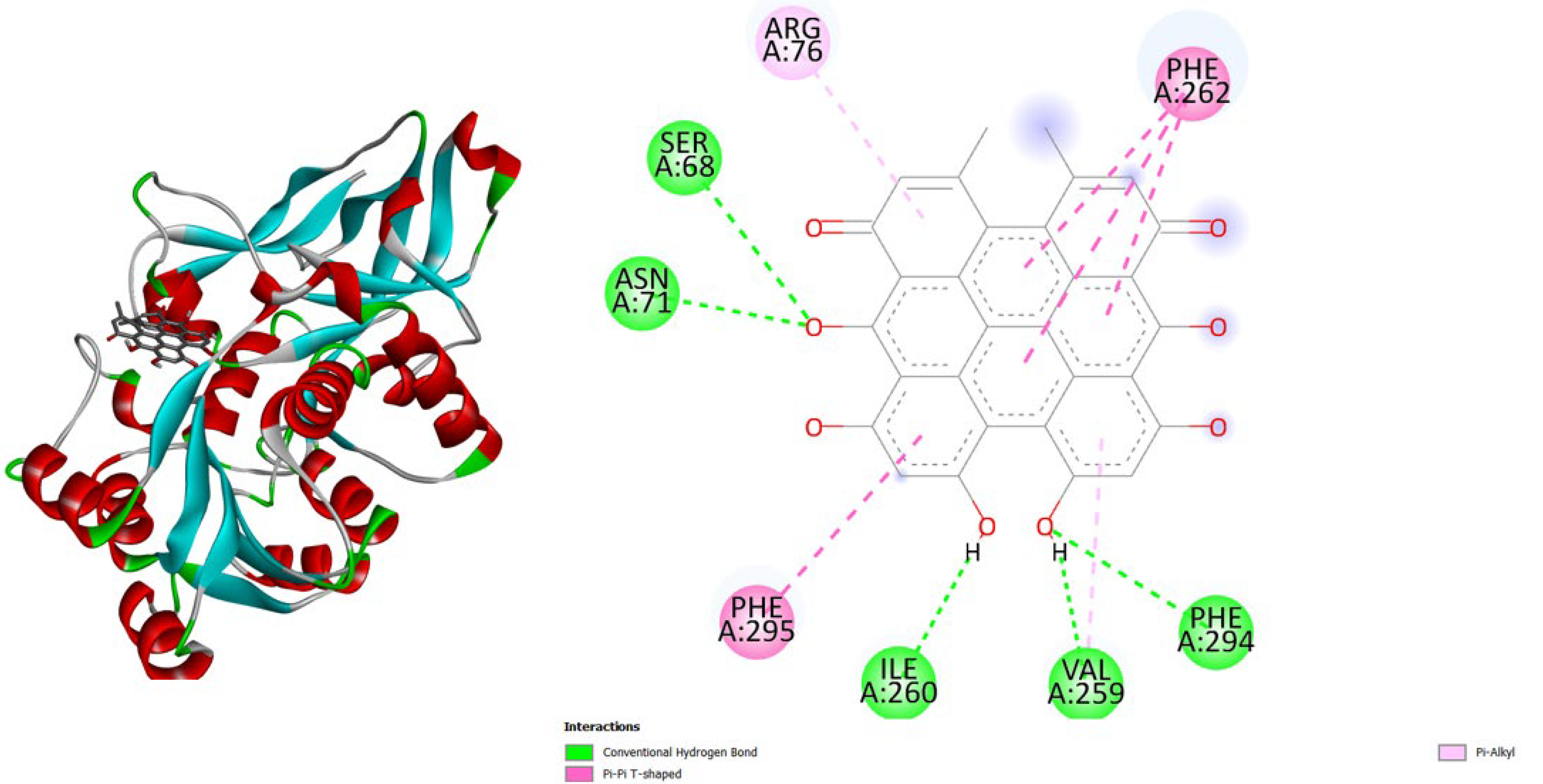

- PG reductase 3 (7ZEJ): Amentoflavone (-11.0) has the strongest binding, followed by Hypericin (-9.6) and the native ligand (-8.7).

4. Conclusions

References

- Schmid-Schönbein, G.W. Analysis of inflammation. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2006, 8, 93–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan, C.N.; Ward, P.A.; Gilroy, D.W. (Eds.). Fundamentals of inflammation. Cambridge University Press: 2010.

- Nathan, C. Points of control in inflammation. Nature 2002, 420, 846–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medzhitov, R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature 2008, 454, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popa, C.; Netea, M.G.; Van Riel, P.L.; Van Der Meer, J.W.; Stalenhoef, A.F. The role of TNF-α in chronic inflammatory conditions, intermediary metabolism, and cardiovascular risk. Journal of lipid research 2007, 48, 751–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nussler, A.K.; Billiar, T.R. Inflammation, immunoregulation, and inducible nitric oxide synthase. Journal of leukocyte biology 1993, 54, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malaviya, R.; Laskin, D.L.; Malaviya, R. Janus kinase-3 dependent inflammatory responses in allergic asthma. International immunopharmacology 2010, 10, 829–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, T.J. Prostaglandin E2, prostaglandin I2 and the vascular changes of inflammation. British Journal of Pharmacology 1979, 65, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciotti, E.; FitzGerald, G.A. Prostaglandins and inflammation. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 2011, 31, 986–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, K.A.; Maity, A.; Roy, S.D.; Pramanik, S.D.; Das, P.P.; Shaharyar, M.A. (2023). Insight into the mechanism of steroidal and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. In How synthetic drugs work (pp. 61–94). Academic Press.

- Xiong, X. , Tang, N., Lai, X., Zhang, J., Wen, W., Li, X.,... & Liu, Z. Insights into amentoflavone: A natural multifunctional biflavonoid. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2021, 12, 768708. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hammer, K.D.; Birt, D.F. Evidence for contributions of interactions of constituents to the anti-inflammatory activity of Hypericum perforatum. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 2014, 54, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakhar, R.; Dangi, M.; Khichi, A.; Chhillar, A.K. Relevance of molecular docking studies in drug designing. Current Bioinformatics 2020, 15, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. Journal of computational chemistry 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dallakyan, S.; Olson, A.J. (2014). Small-molecule library screening by docking with PyRx. In Chemical biology: methods and protocols (pp. 243–250). New York, NY: Springer New York.

- Baroroh, U.; Biotek, M.; Muscifa, Z.S.; Destiarani, W.; Rohmatullah, F.G.; Yusuf, M. Molecular interaction analysis and visualization of protein-ligand docking using Biovia Discovery Studio Visualizer. Indonesian Journal of Computational Biology (IJCB) 2023, 2, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Protein (PDB) | Amentoflavone | Hypericin | Native ligand |

|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α (2AZ5) | -9.5 | -9.9 | -8.8 |

| iNOS (3E7G) | -11.3 | -10.4 | -6.9 |

| JAK3 (6HZV) | -9.5 | -11.4 | -9.2 |

| PGE synthase (4AL1) | -7.7 | -7.1 | -5.9 |

| PG reductase 3 (7ZEJ) | -11.0 | -9.6 | -8.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).