Submitted:

07 September 2025

Posted:

09 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. INTRODUCTION

A. BACKGROUND

B. OBJECTIVES

2. RESEARCH METHOD

A. FLUID FLOW EQUATIONS

B. ELECTRIC FIELDS EQUATIONS

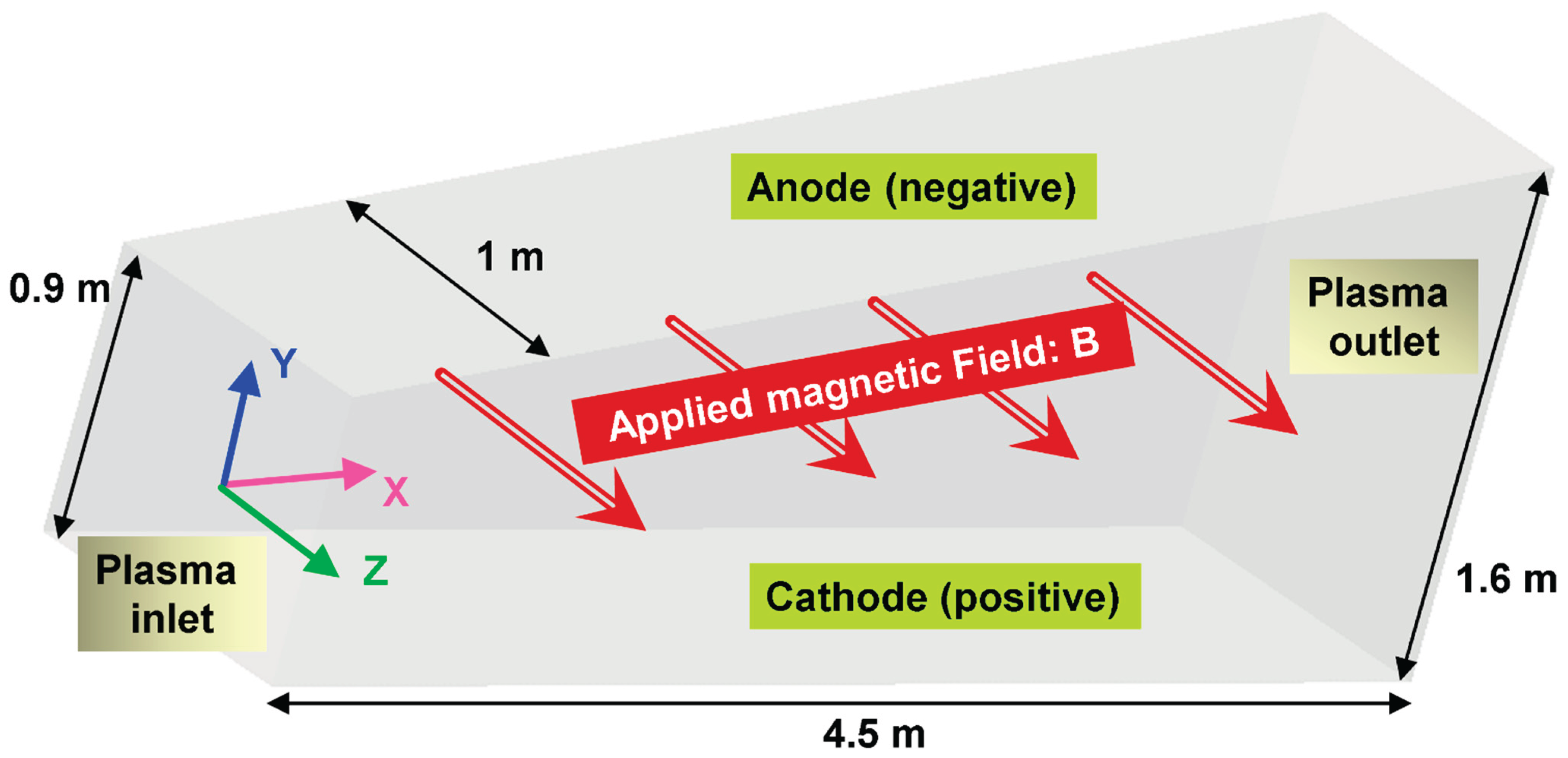

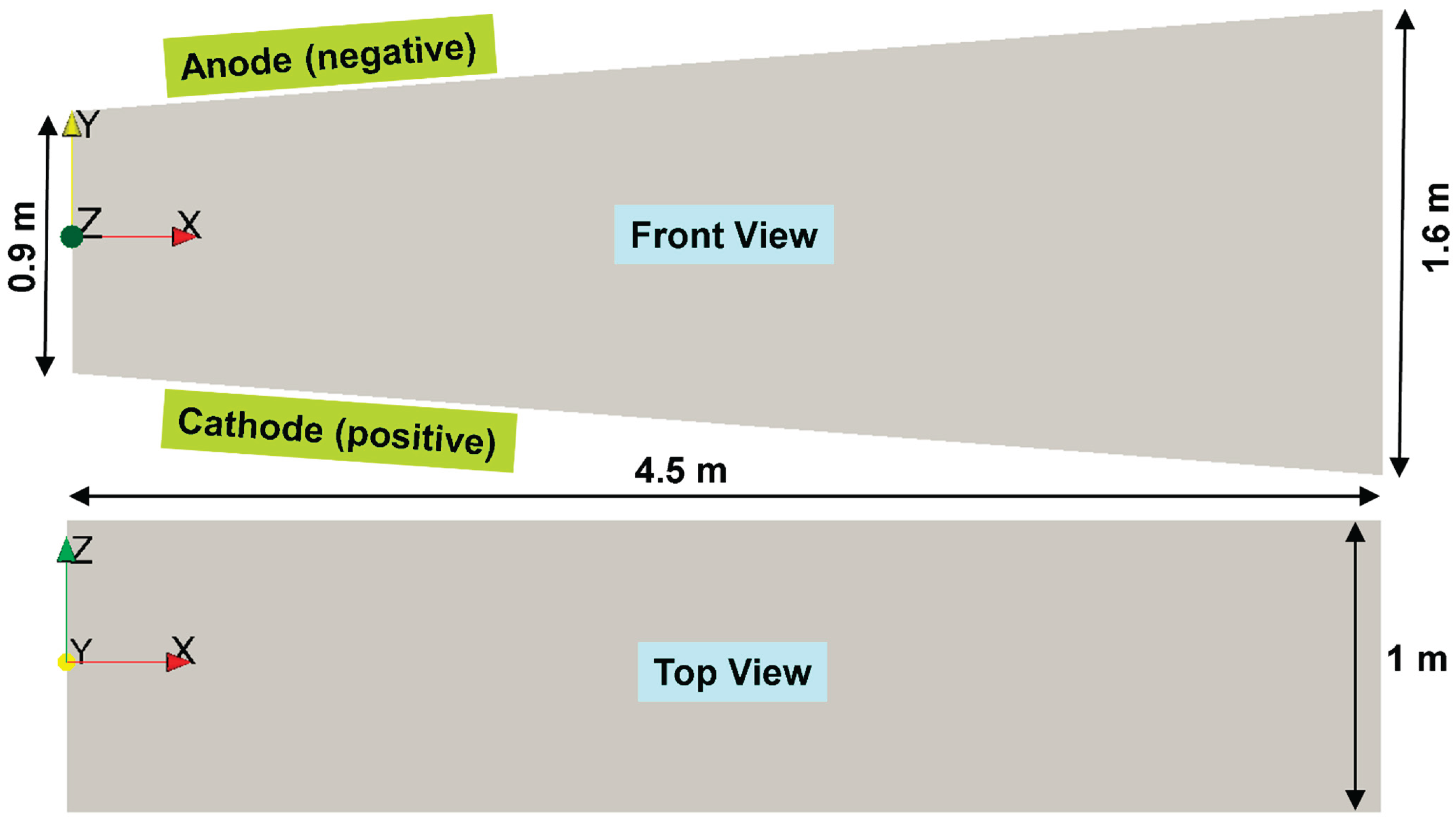

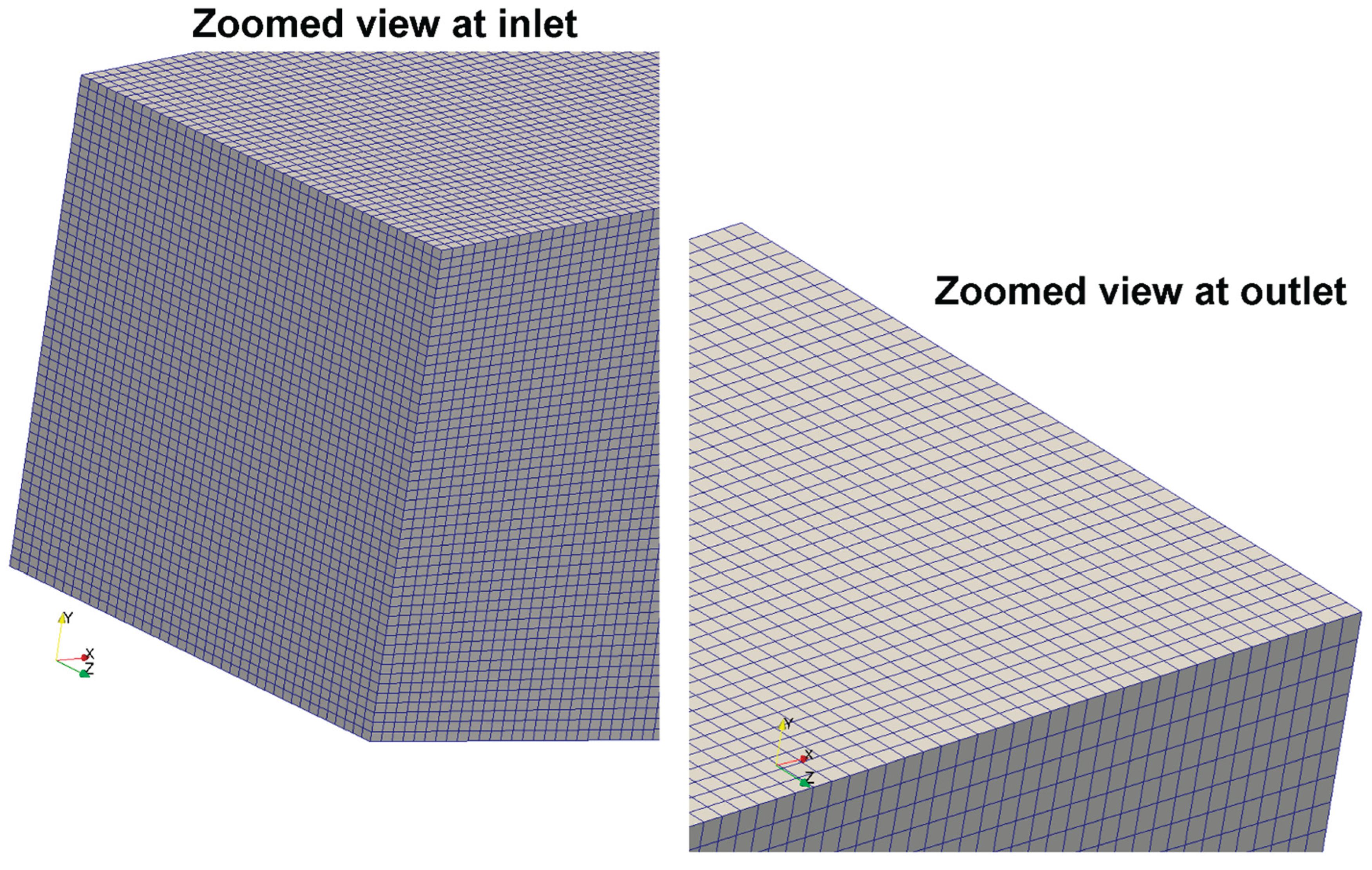

C. GEOMETRY AND MESH OF THE SAKHALIN MHD CHANNEL

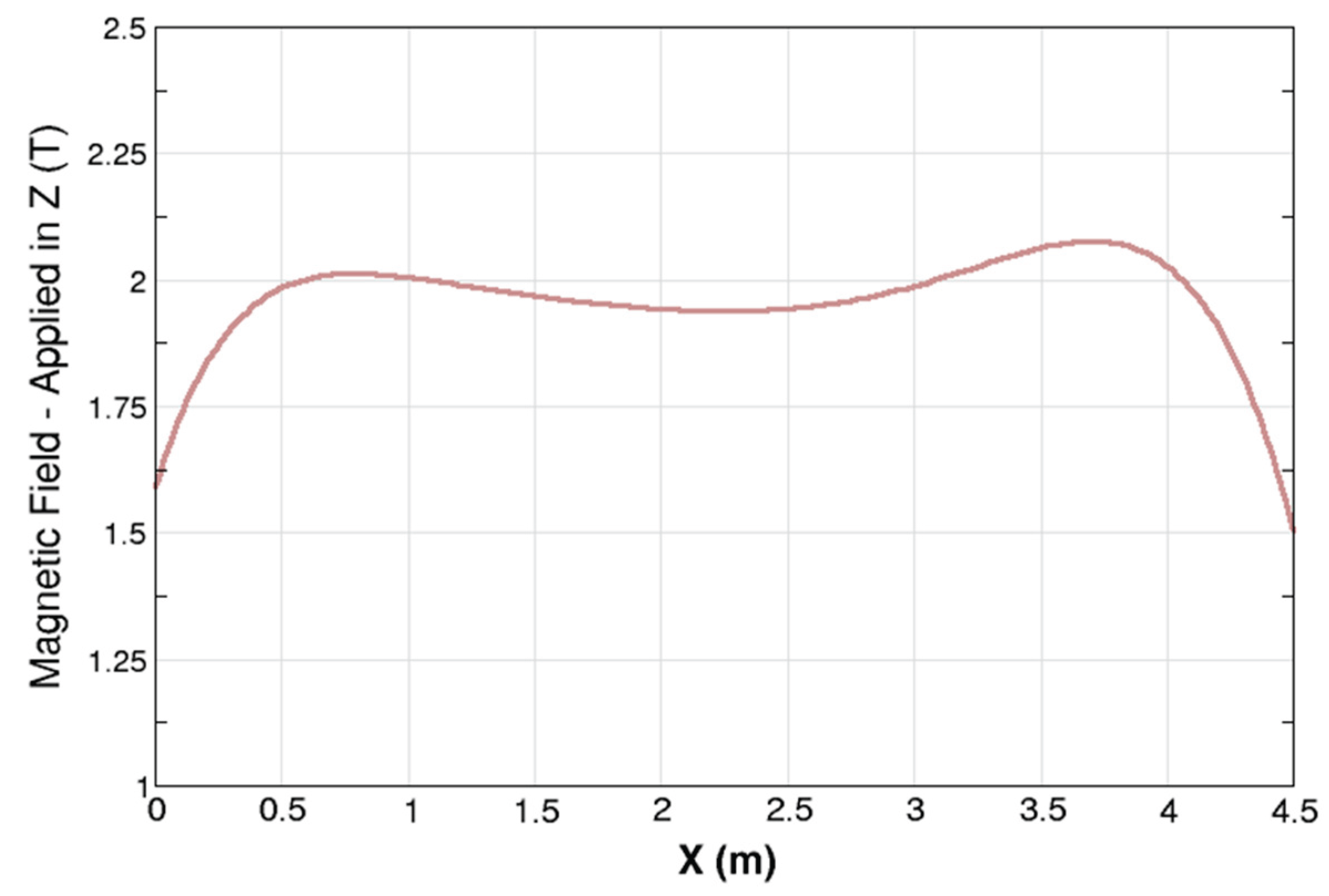

D. EMPIRICAL EXPRESSIONS FOR SAKHALIN

E. COMPUTATIONAL SETTINGS

3. VALIDATION AND VERIFICATION

4. RESULTS

Scalar Values at the MHD Channel Outlet

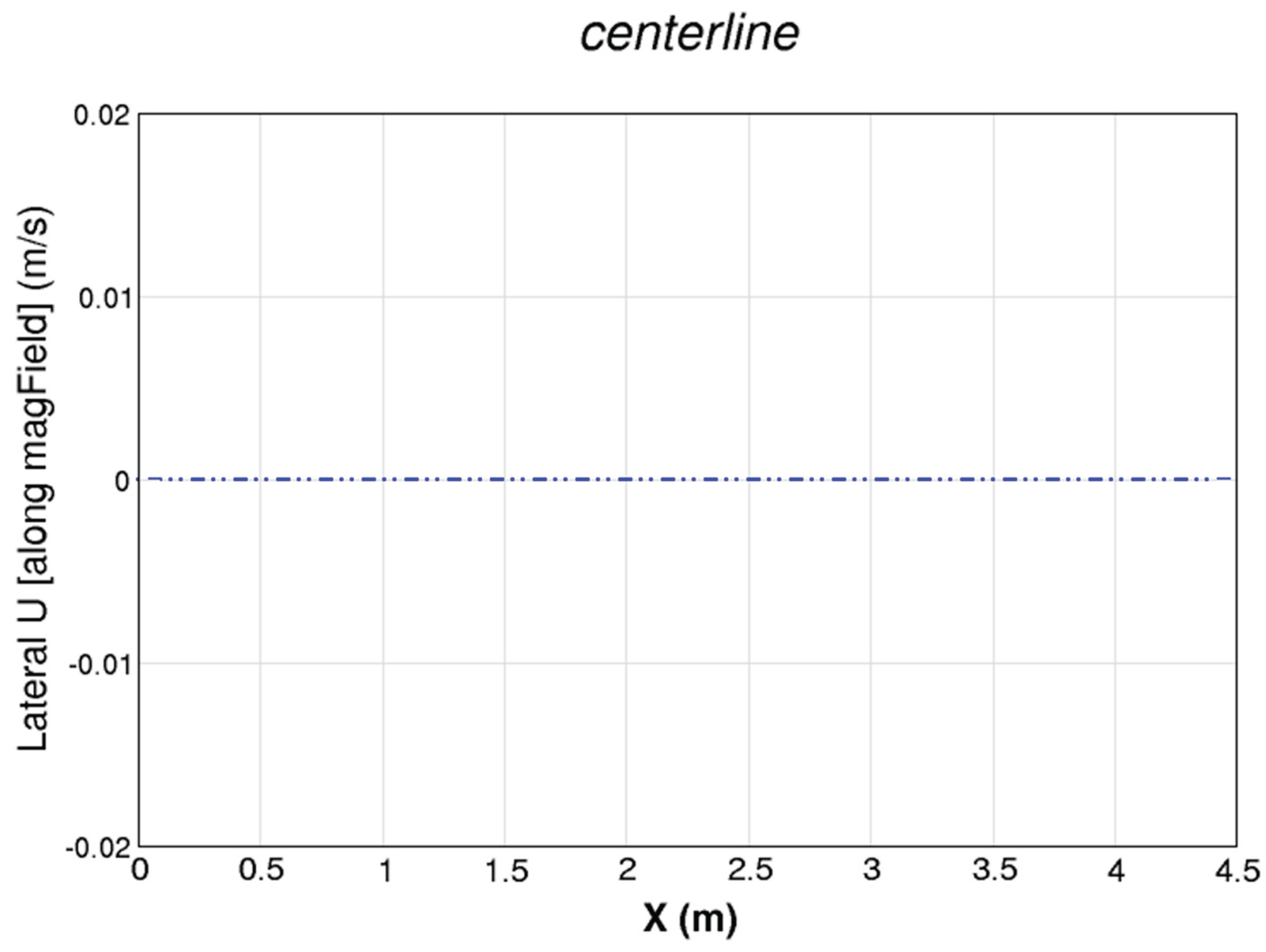

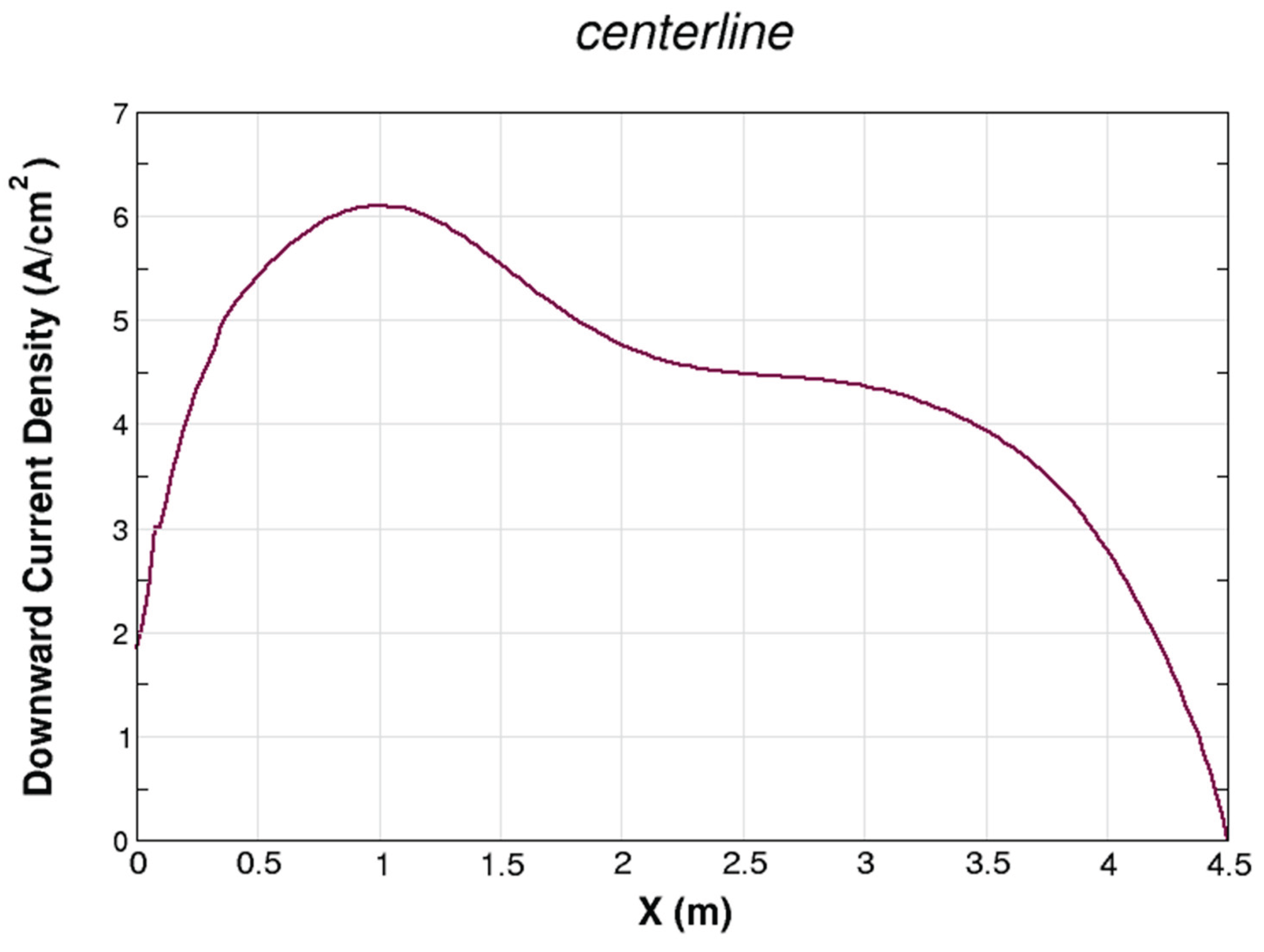

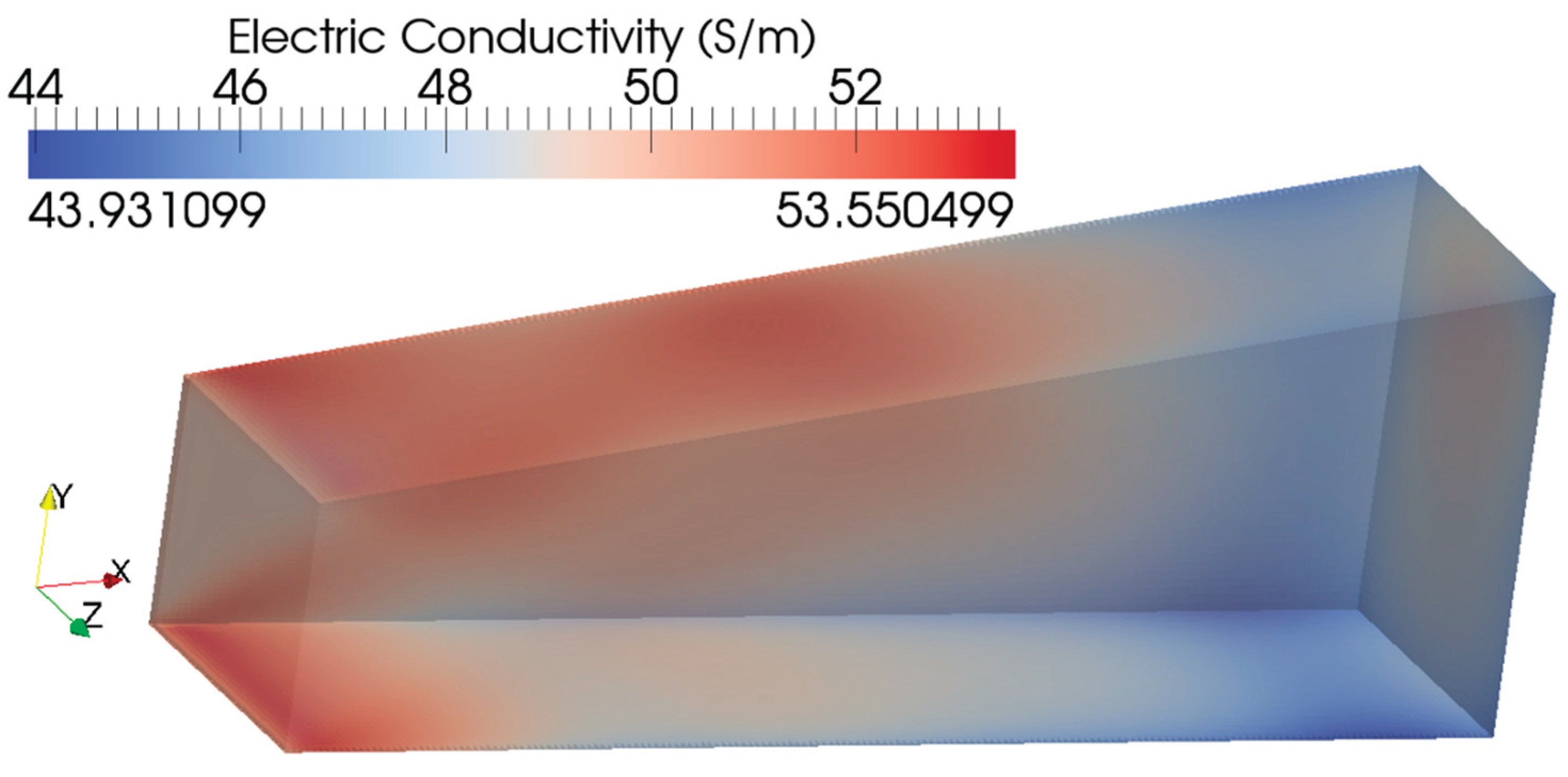

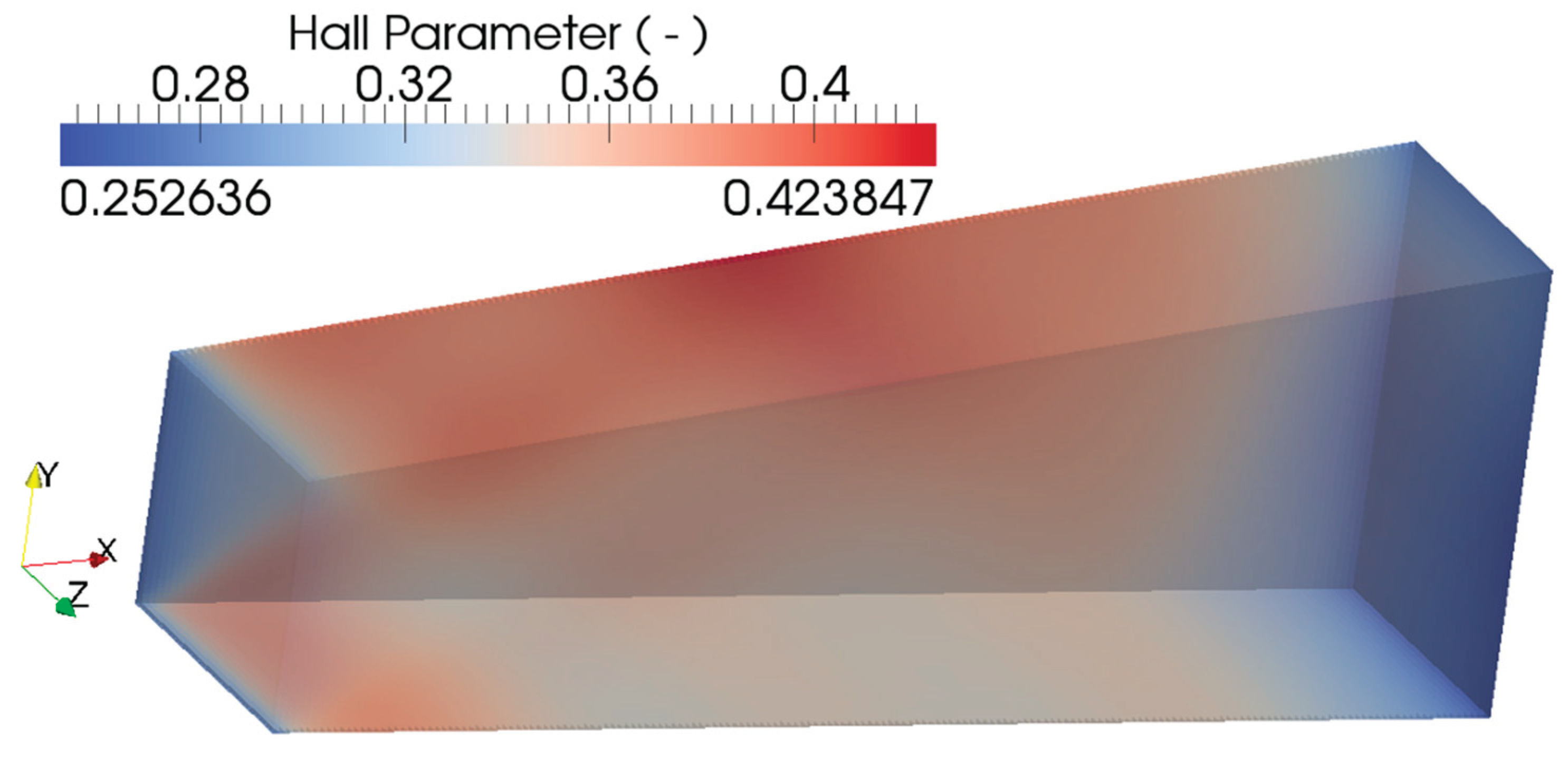

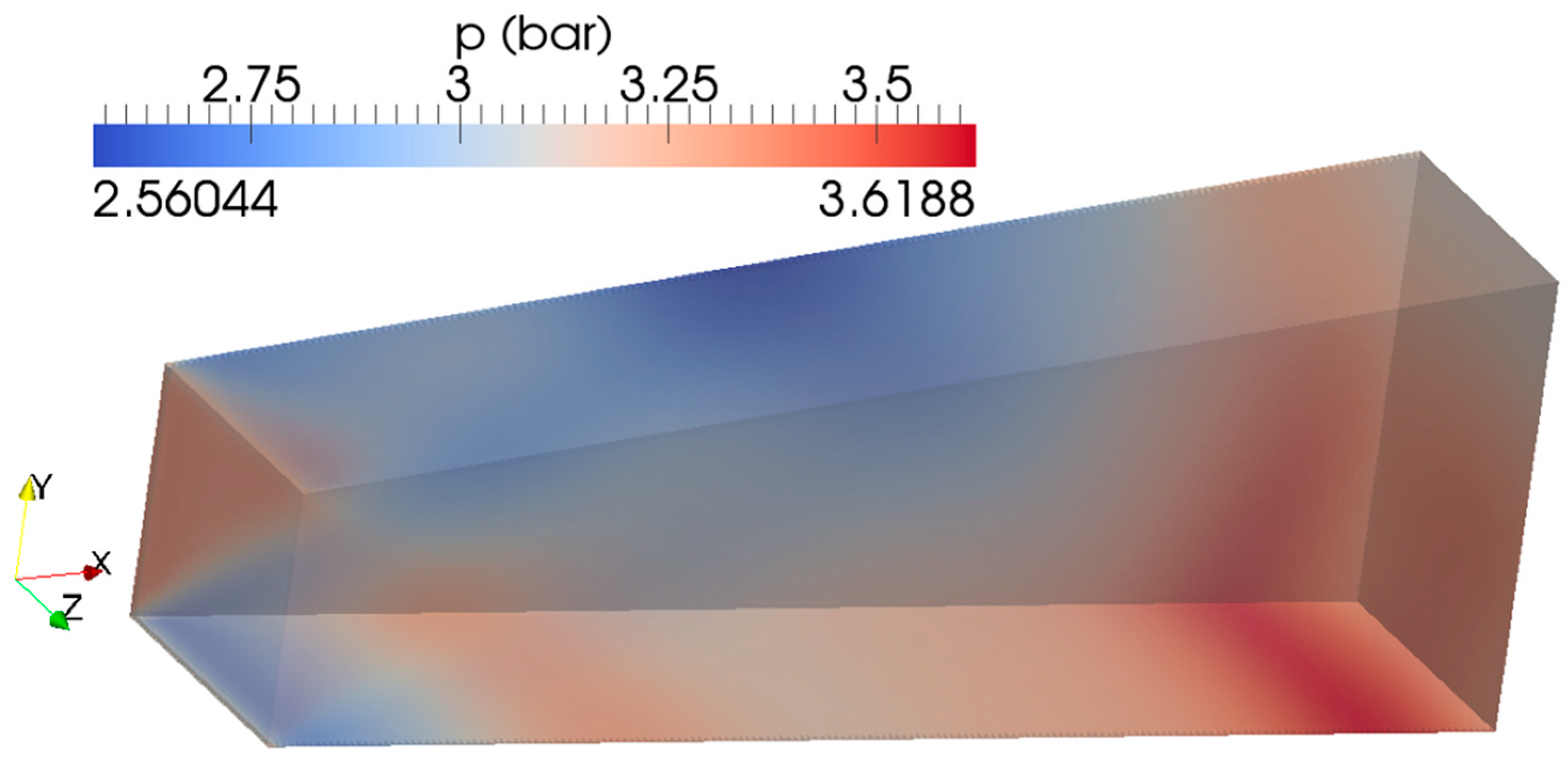

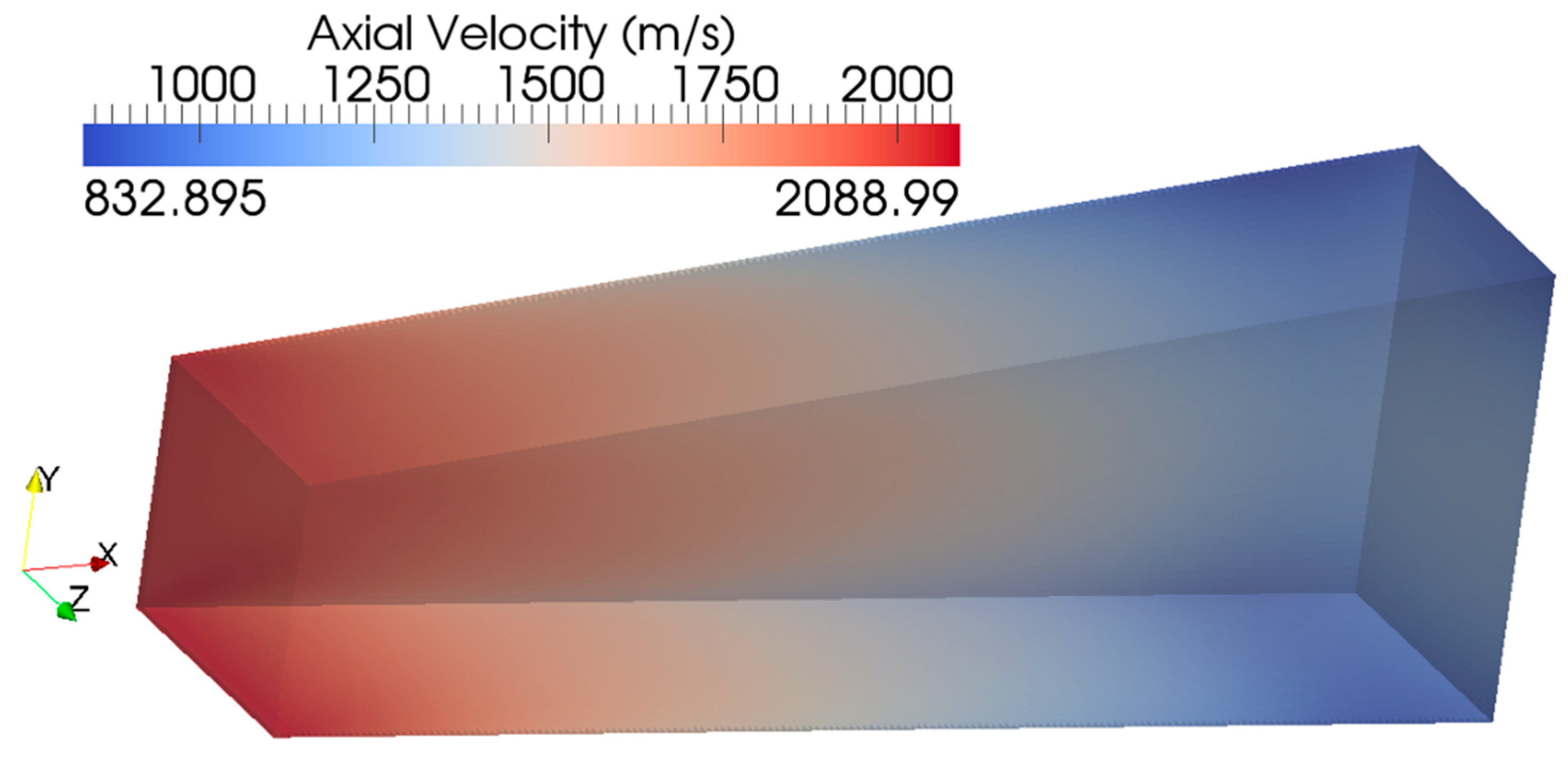

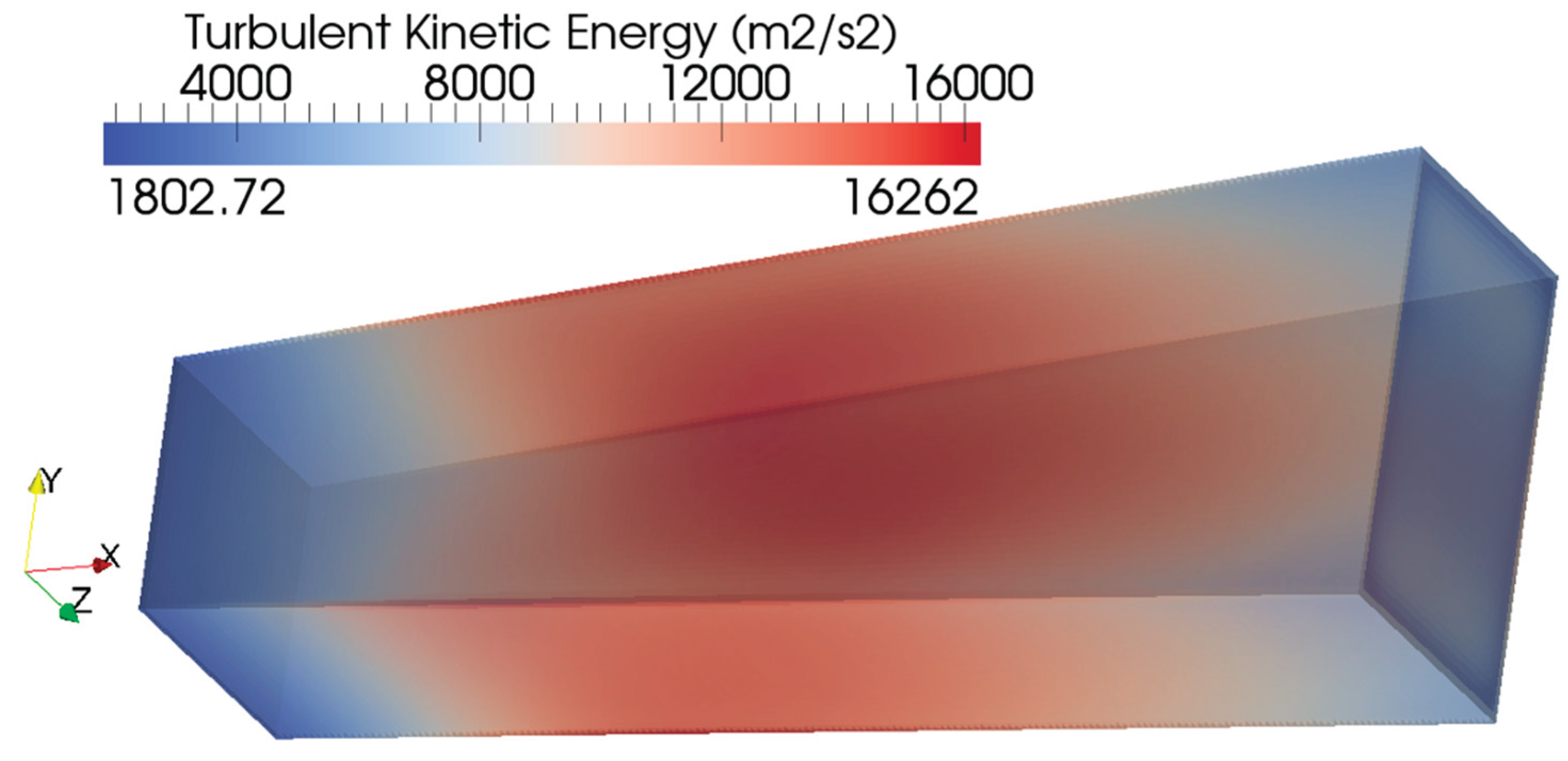

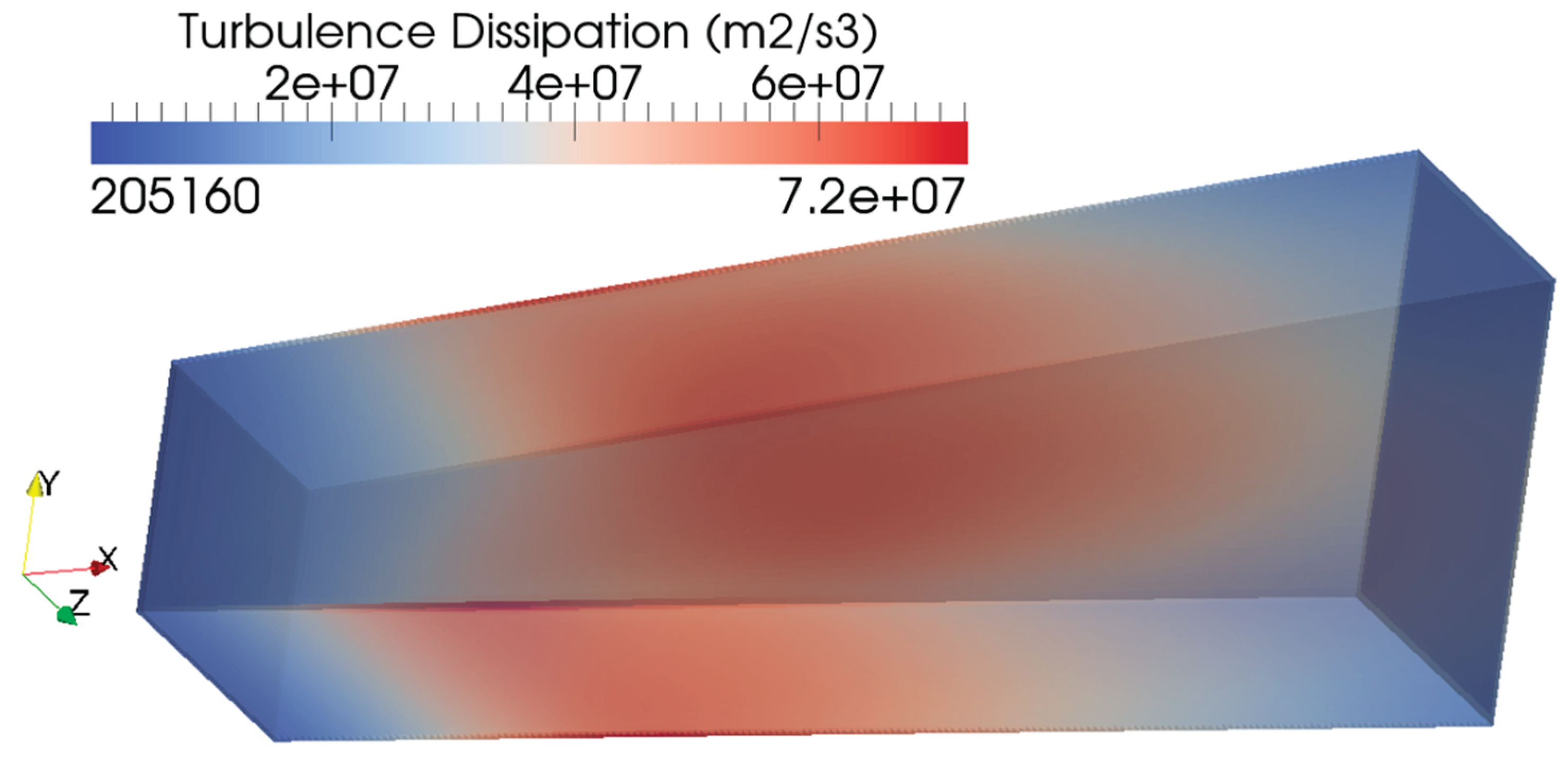

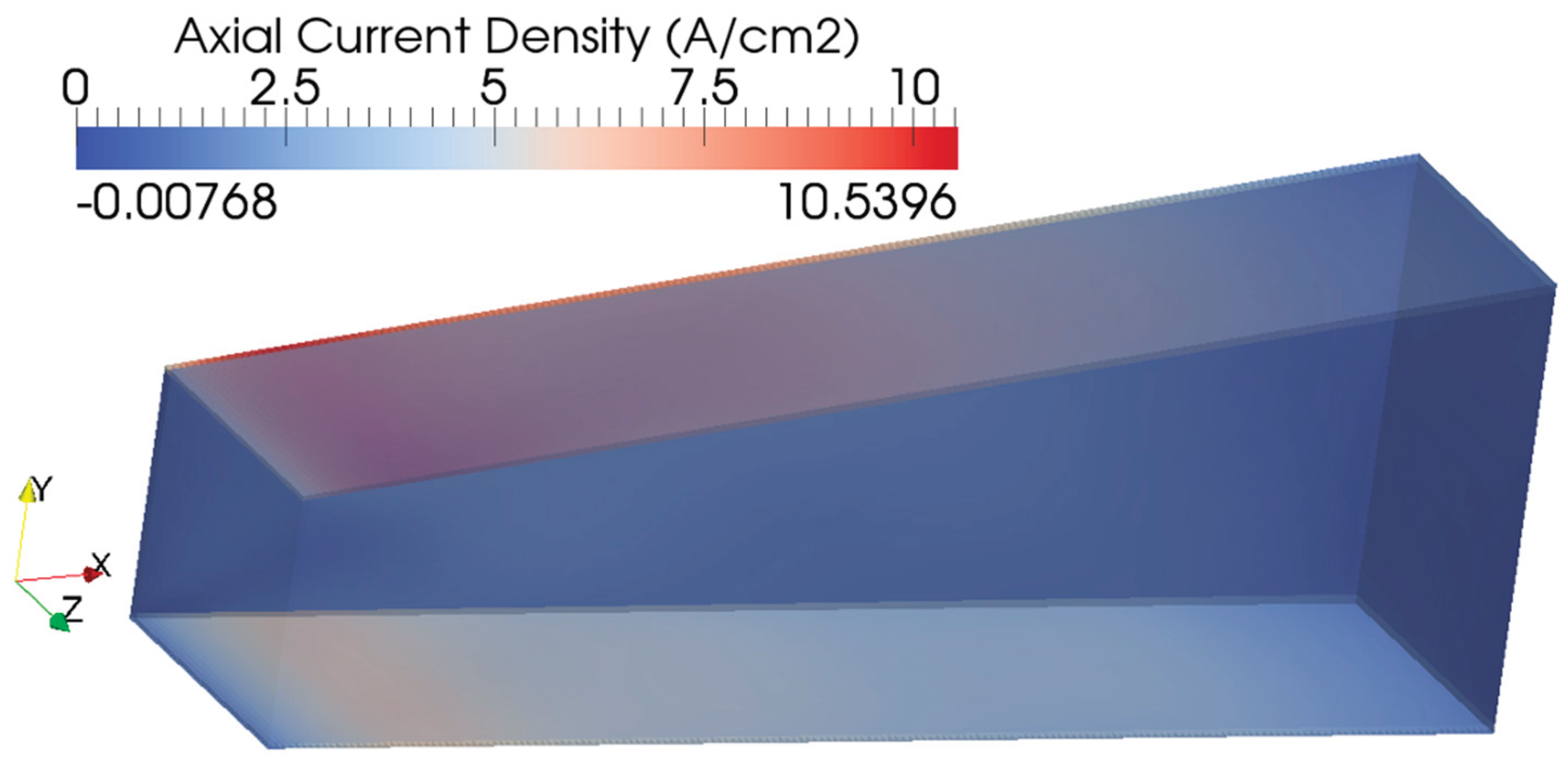

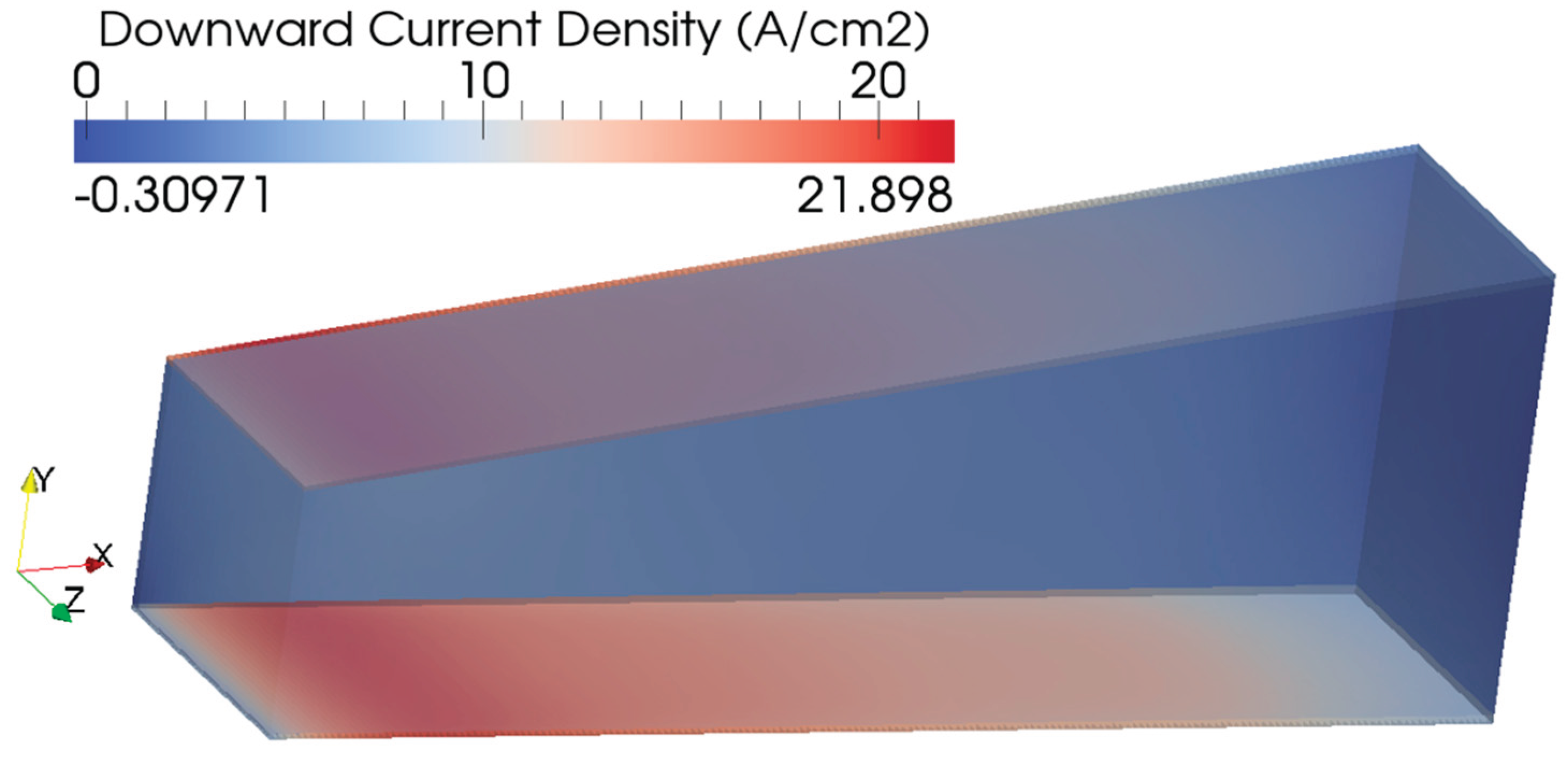

B. THREE-DIMENSIONAL DISTRIBUTIONS

5. CONCLUSIONS

- A review of real examples of pulsed MHG generators (PMHD) was made, with emphasis on the Sakhalin model that was described with quantitative values and empirical regression models for its operational settings that help in modeling it by others. A large number of literature research articles were used in preparing this review.

- A mathematical/computational model is proposed for simulating the three-dimensional fluid dynamic and electric fields for linear continuous-electrode MHD channels. The proposed solver was found to yield satisfactory outputs when compared to other independent studies. The ability of the solver to give resolution-independent results was verified.

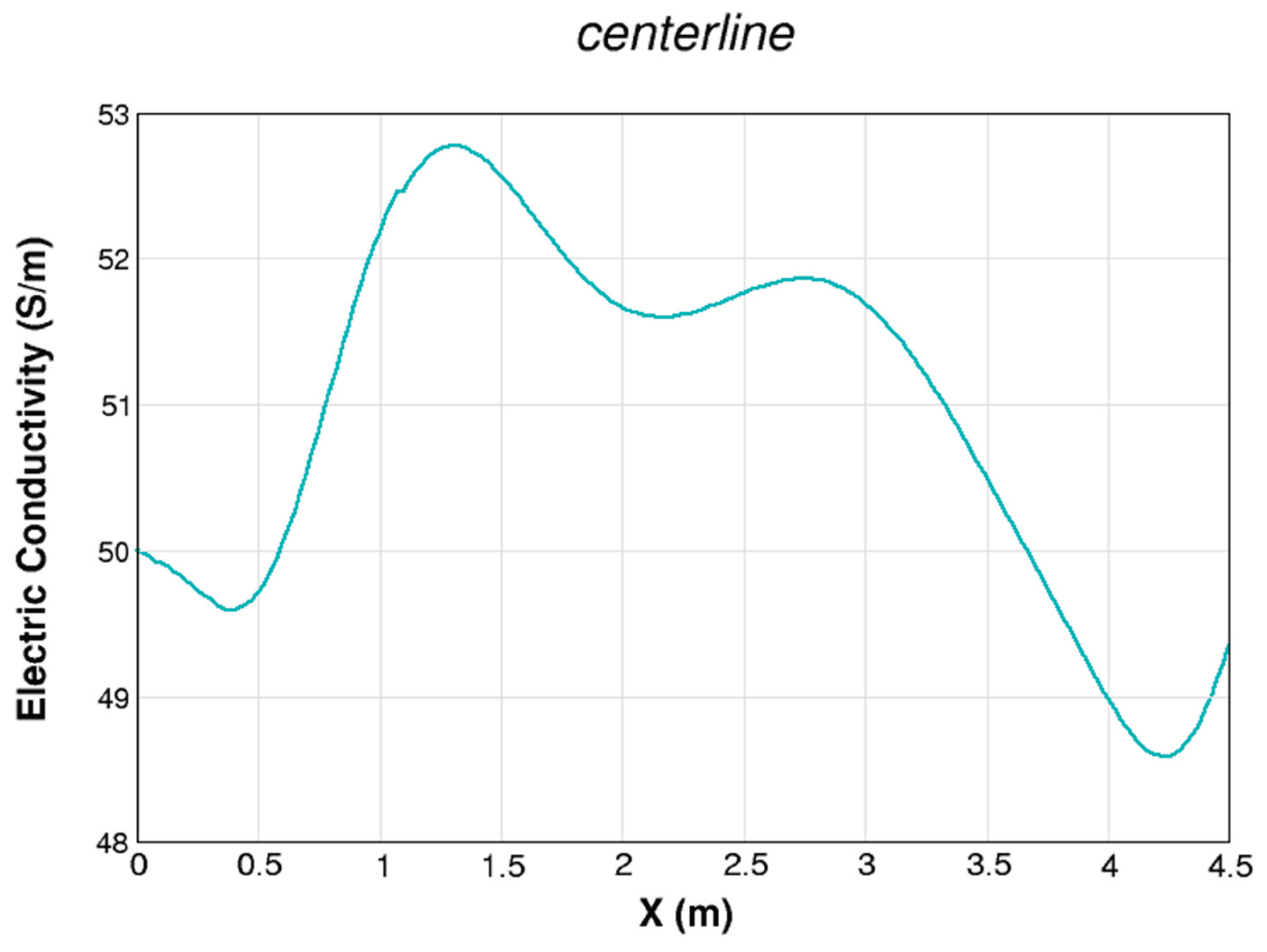

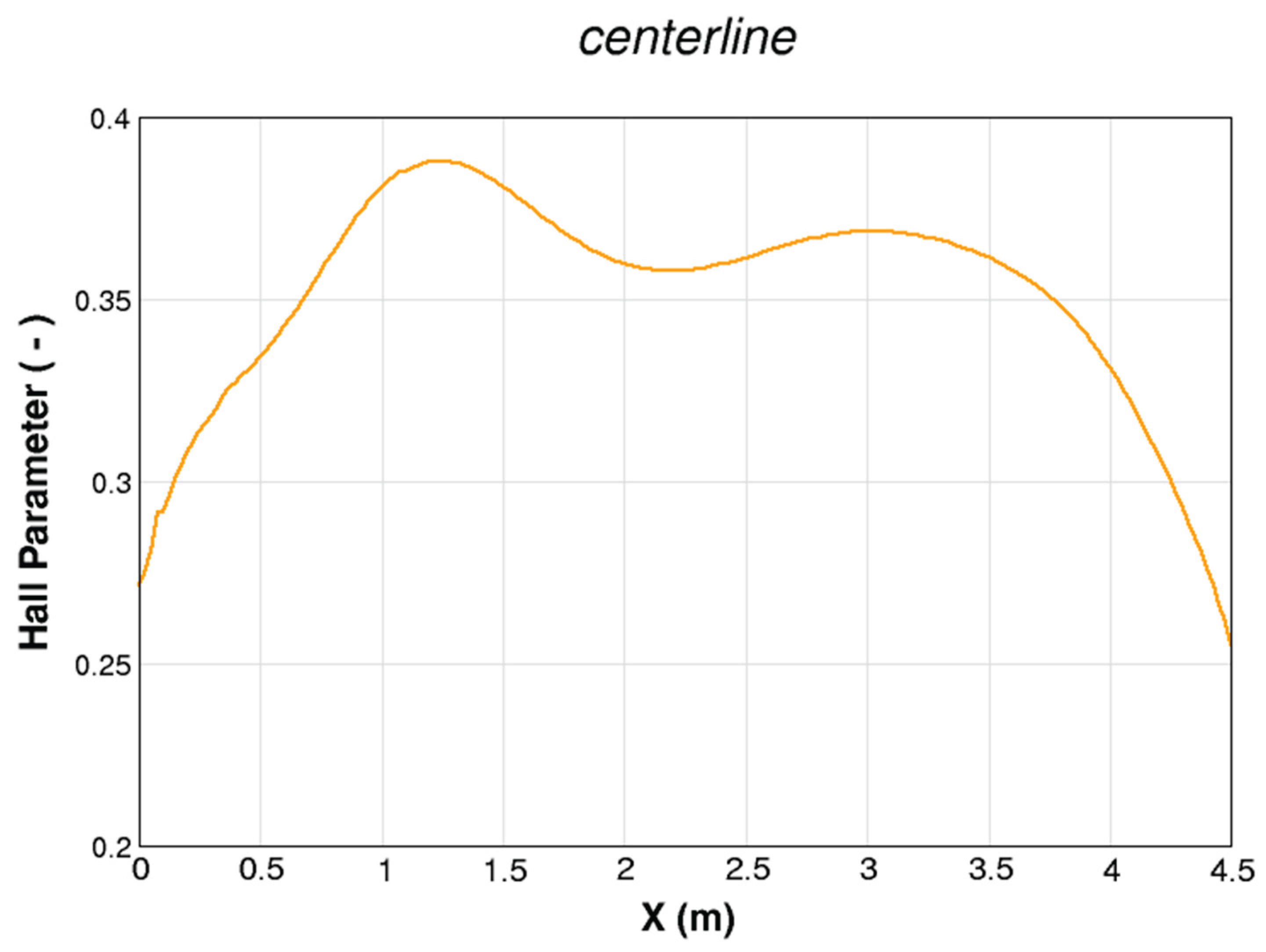

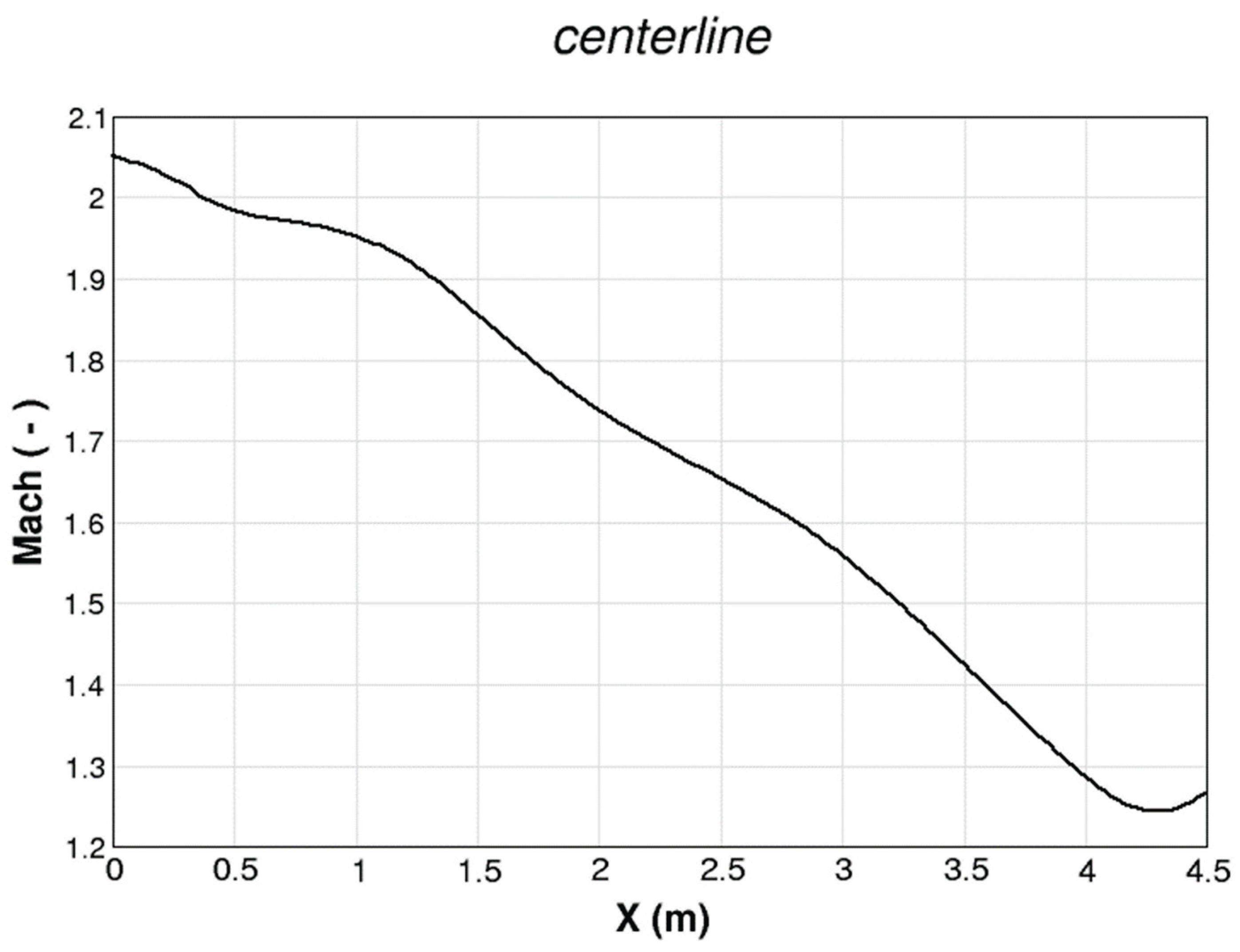

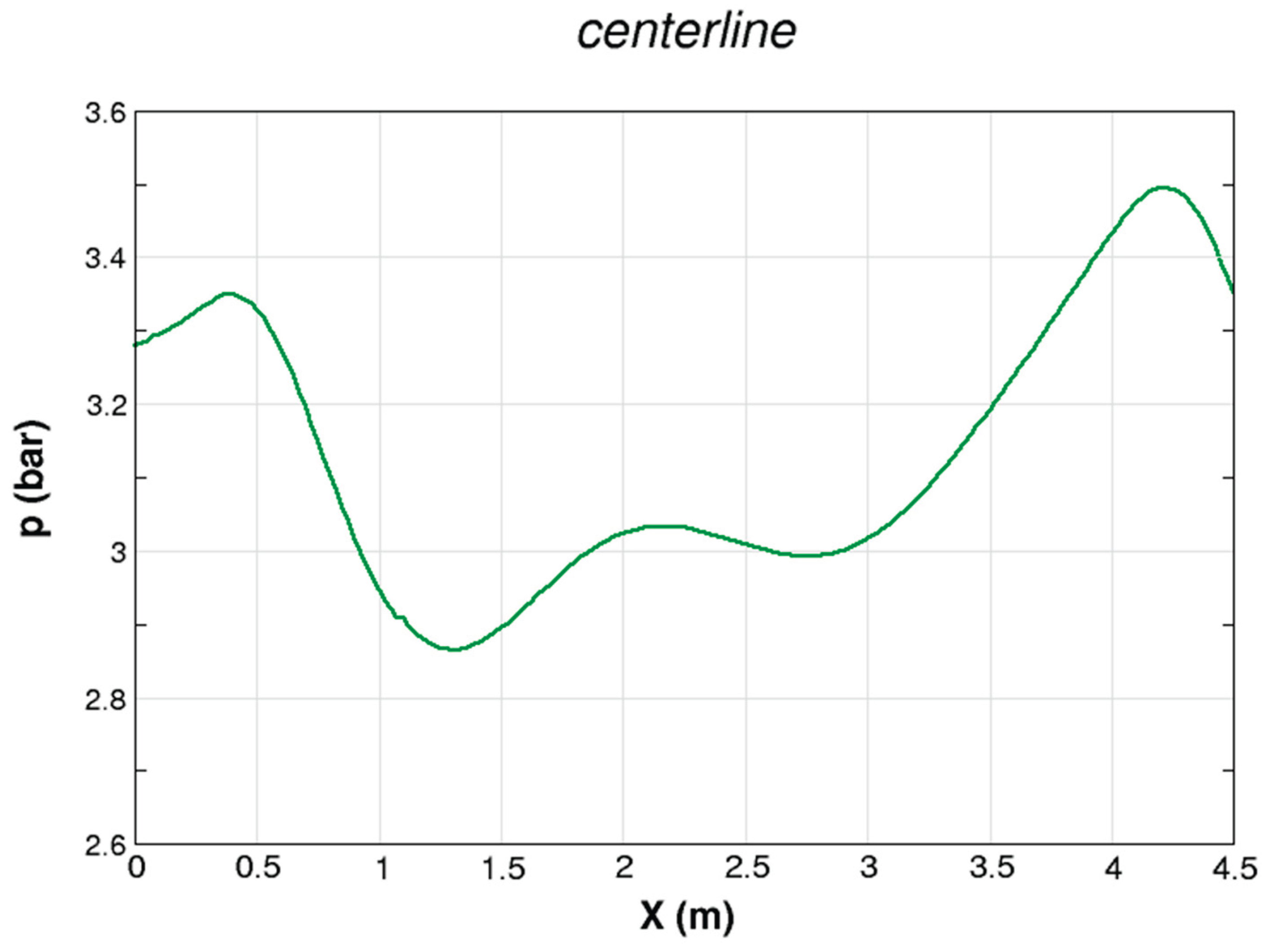

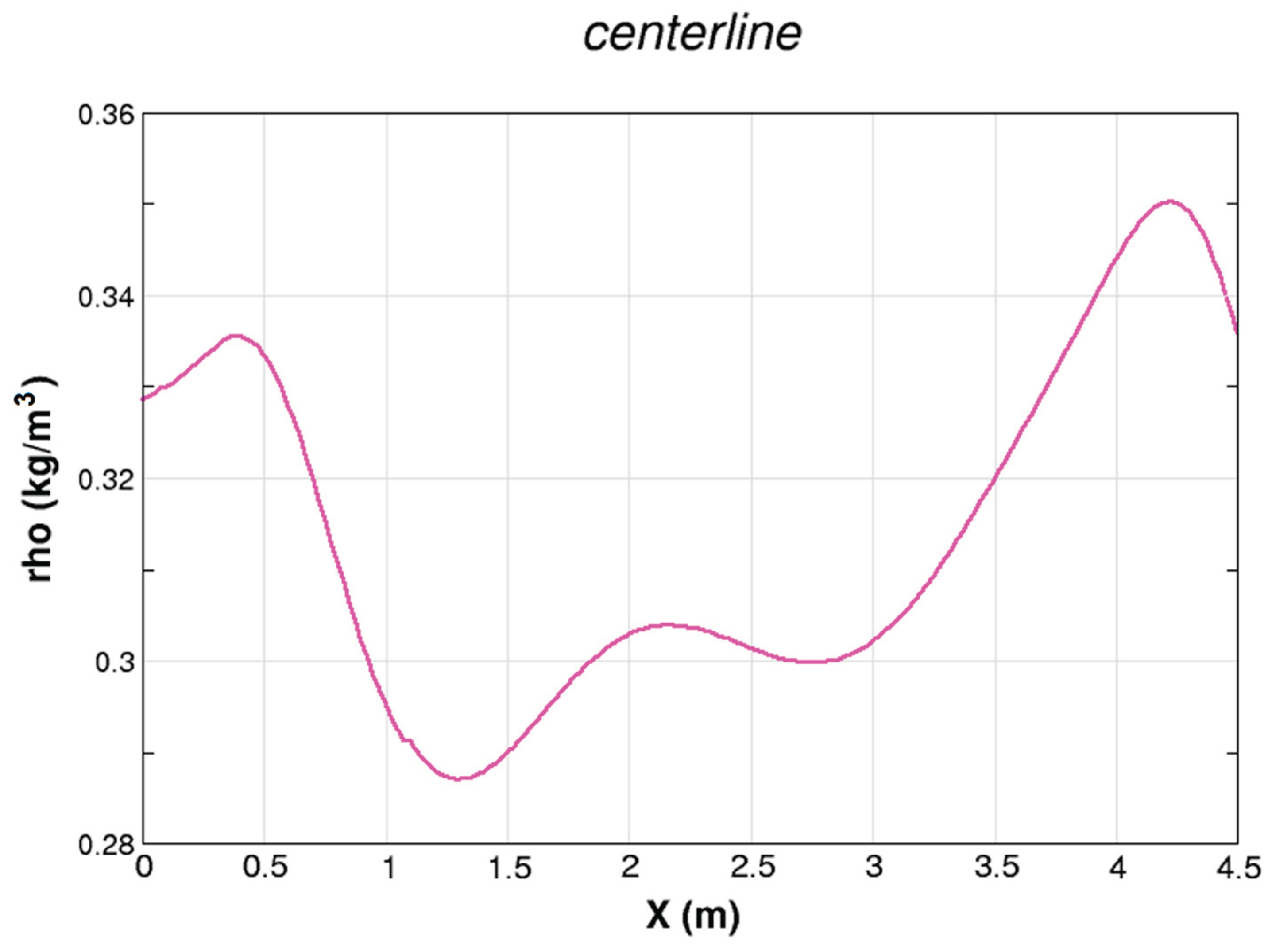

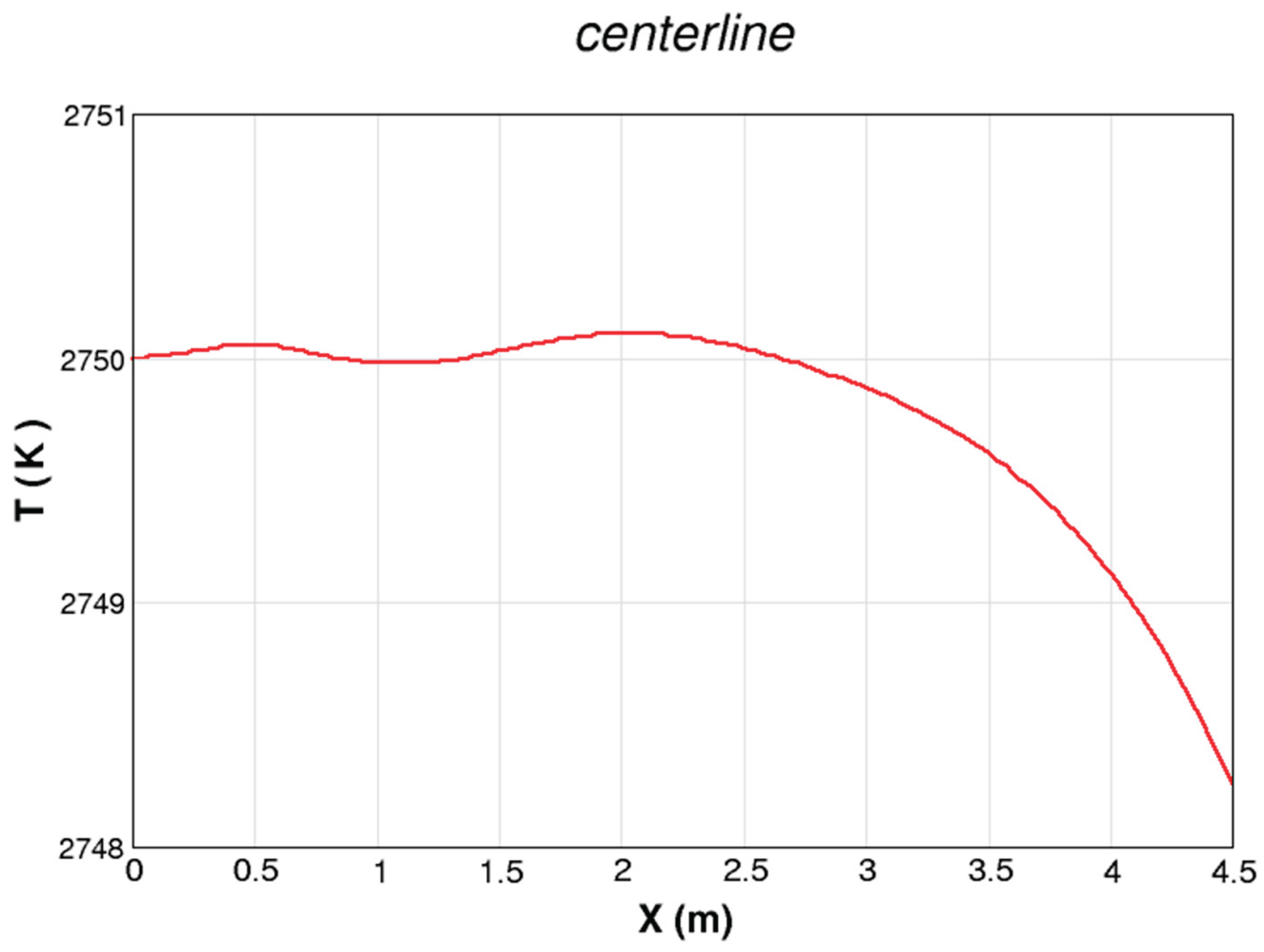

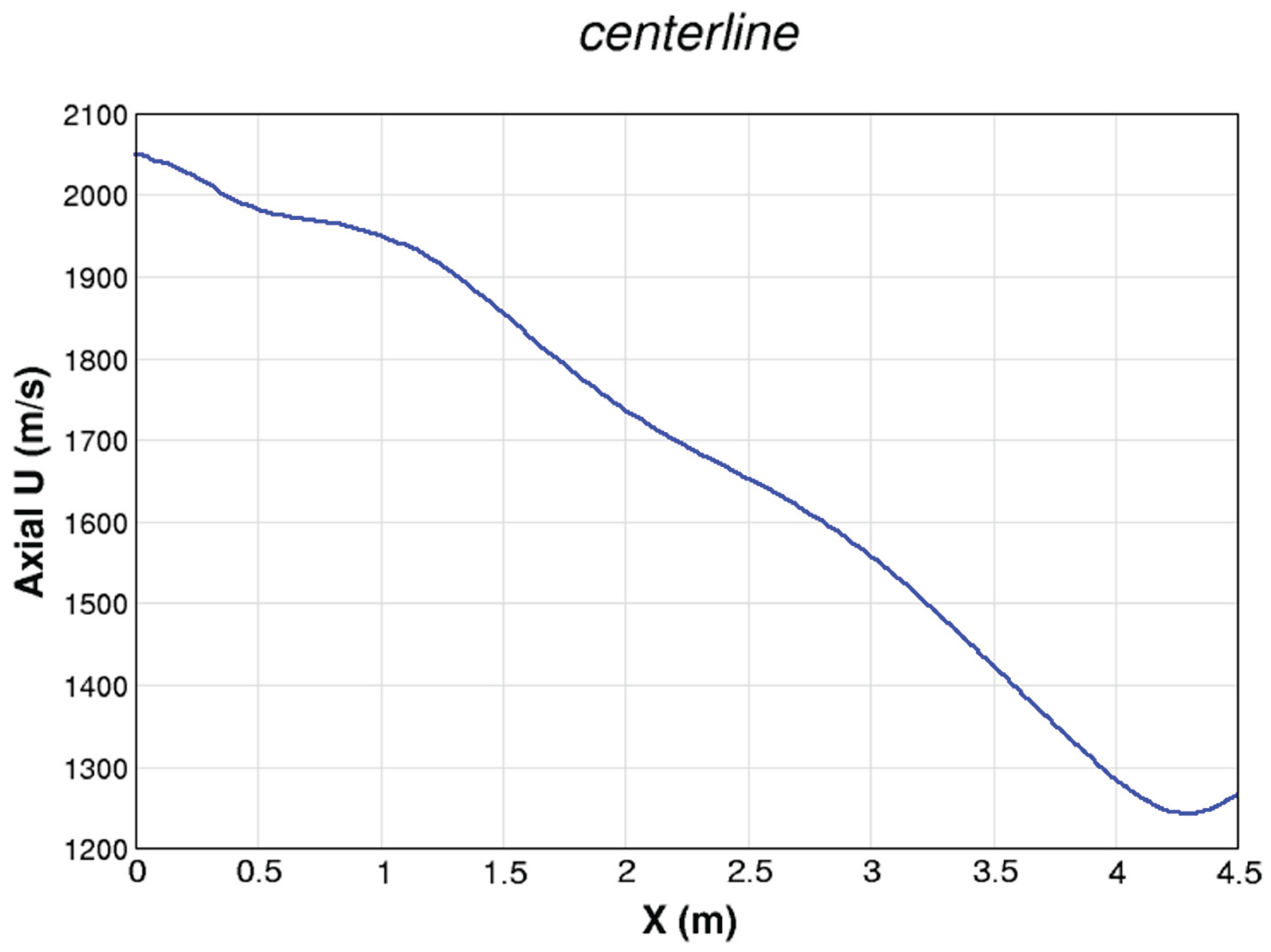

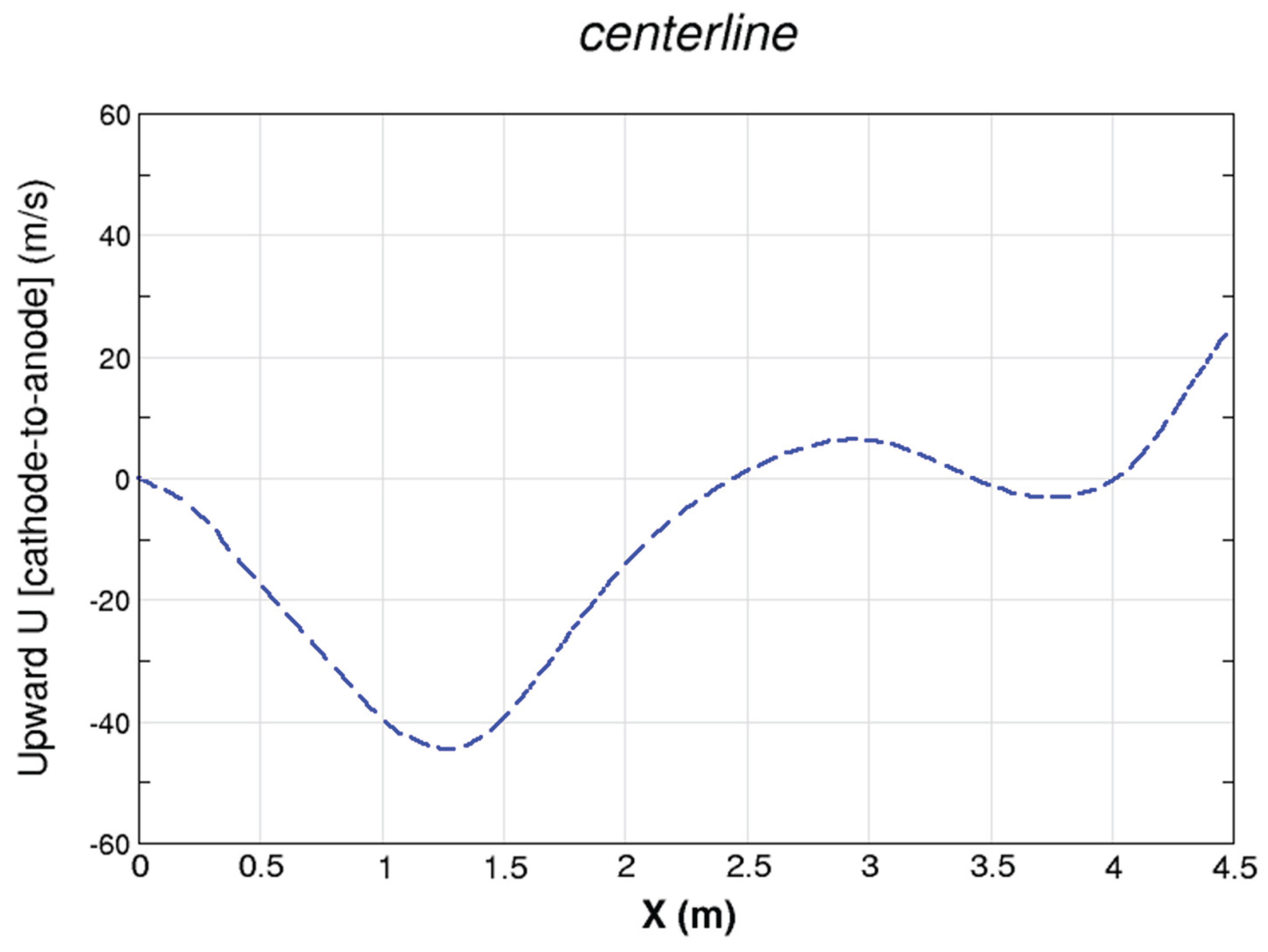

- Selected results from our CFD simulation for the Sakhalin MHD channel were presented and discussed. Using the power of CFD and data post-processing, it was possible to reveal various attributes of the channel of the Sakhalin PMHDG, such as the nearly-isothermal operation, the extraction of energy mainly from the kinetic energy of the plasma (rather than the thermal or the pressure energies), the unusual deceleration (opposite to the conventional situation) of supersonic flow despite flowing in a divergent channel, the weak change in the electric conductivity, and the pressure recovery phenomenon.

Funding

DECLARATION OF COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT

Nomenclature (in Alphabetical Order)

| CAD | Computer-aided design |

| CCGT | Combined-cycle gas turbine |

| CFD | Computational fluid dynamics |

| DC | Direct current |

| DPE | Direct power extraction |

| ECE | External combustion engine |

| FANS | Favre-averaged Navier-Stokes equations |

| FSI | Fluid-structure interaction |

| FVM | Finite volume method |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| HRSG | Heat recovery steam generator |

| ICE | Internal combustion engine |

| MHD | Magnetohydrodynamics |

| OFCC | Oxy-fuel carbon capture |

| OOP | Object-oriented programming |

| PG | Plasma generator |

| PMHDG | Pulsed magnetohydrodynamic generator |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| RANS | Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes equations |

| SPP | Solid-propellant plasma |

| TEG | Thermoelectric generator |

| USSR | Union of Soviet Socialist Republics |

References

- Gruzdeva, E. J. The Linguistic Situation on Sakhalin Island. In Atlas of Languages of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas: Vol I: Maps. Vol II: Texts; Wurm, S. A., Mühlhäusler, P., Tryon, D. T., Eds.; De Gruyter Mouton, 2011; pp 1007–1012. [CrossRef]

- Syrbu, N.; Kholmogorov, A.; Stepochkin, I.; Lobanov, V.; Shkorba, S. Formation of Abnormal Gas-Geochemical Fields and Dissolved Gases Transport at the Shallow Northeastern Shelf of Sakhalin Island in Warm Season: Expedition Data and Remote Sensing. Water 2024, 16 (10), 1434. [CrossRef]

- Afonin, A. G.; Butov, V. G.; Panchenko, V. P.; Sinyaev, S. V.; Solonenko, V. A.; Shvetsov, G. A.; Yakushev, A. A. Powerful Pulsed Magnetohydrodynamic Generator Fueled by a Solid (Powder) Propellant of a New Generation. J Appl Mech Tech Phy 2018, 59 (6), 1024–1035. [CrossRef]

- Panchenko, V. P. Peculiarities of Two-Phase Flow in Pulsed MHD Generators. In 12th International Conference on MHD Electrical Power Generation; Yokohama, Japan, 1996; Vol. 1, pp 972–980.

- Yuhara, M.; Fujino, T.; Ishikawa, M. Numerical Analysis of Effects of Liquid Particles on Plasmadynamics in a Large-Scale Pulsed MHD Generator. In 35th AIAA Plasmadynamics and Lasers Conference; AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics]: Portland, Oregon, USA, 2004; p AIAA-2004-2369. [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, M.; Koshiba, Y. 52. Preliminary Analysis of Large Pulsed MHD Generator. In 3th Workshop on Magnetoplasma Aerodynamics for Aerospace Applications; Moscow, Russia, 2001; pp 276–281.

- Marzouk, O. A. Combined Oxy-Fuel Magnetohydrodynamic Power Cycle. In Conference on Energy Challenges in Oman (ECO’2015); DU [Dhofar University]: Salalah, Dhofar, Oman, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Angrist, S. W. Direct Energy Conversion, 4. ed.; Allyn and Bacon series in mechanical engineering and applied mechanics; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, Massachusetts, USA, 1982.

- Marzouk, O. A. Thermoelectric Generators versus Photovoltaic Solar Panels: Power and Cost Analysis. Edelweiss Applied Science and Technology 2024, 8 (5), 406–428. [CrossRef]

- Panchenko, V. P. 55. Preliminary Analysis of the “Sakhalin” World Largest Pulsed MHD Generator. In 4th Workshop on Magnetoplasma Aerodynamics for Aerospace Applications; Moscow, Russia, 2002; pp 322–331.

- Yakushev, A. A.; Panchenko, V. P.; Dyogtev, Yu. G.; Dogadayev, R. V.; Gomozov, V. A.; Ivanenko, A. A. Recent Experimental Researches of Combustion Products Plasma of Combined (Pyrotechnic) Propellant for Pulsed MHD Generators. In 13th International Conference on MHD Electrical Power Generation and High Temperature Technologies; Beijing, China, 1999; Vol. 2, pp 423–434.

- Ishikawa, M.; Koshiba, Y.; Matsushita, T. Effects of Induced Magnetic Field on Large Scale Pulsed MHD Generator with Two Phase Flow. Energy Conversion and Management 2004, 45 (5), 707–724. [CrossRef]

- Dogadayev, R. V.; Koroleva, L. A.; Martinov, B. M.; Panchenko, V. P.; Yakushev, A. A.; Bukhteyev, L. A. Experimental and Numerical Investigations of the Pulsed Solid Propellant Diagonal Type MHD Generator “Pamir-06.” In 12th International Conference on MHD Electrical Power Generation; Yokohama, Japan, 1996; Vol. 1, pp 61–70.

- Marzouk, O. A. Estimated Electric Conductivities of Thermal Plasma for Air-Fuel Combustion and Oxy-Fuel Combustion with Potassium or Cesium Seeding. Heliyon 2024, 10 (11), e31697. [CrossRef]

- Bong, H. K.; Selvarajoo, A.; Arumugasamy, S. K. Stability of Biochar Derived from Banana Peel through Pyrolysis as Alternative Source of Nutrient in Soil: Feedforward Neural Network Modelling Study. Environ Monit Assess 2022, 194 (2), 70. [CrossRef]

- Brockmeier, U.; Koch, M.; Unger, H.; Schütz, W. Volatile Fission Product and Sodium Release from Liquids. Nuclear Engineering and Design 1994, 148 (2), 499–507. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, J.; Jia, C.; Lv, Y.; Liu, Y. Co-Pyrolysis of Cyanobacteria and Plastics to Synthesize Porous Carbon and Its Application in Methylene Blue Adsorption. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2021, 39, 101753. [CrossRef]

- Pasi S.r.l. Instruments for Earth Resistivity Measurement of the Subsoil. https://www.pasisrl.it/c/en/earth-resistivity/geoelectrical-prospecting-electrical-imaging (accessed 2025-02-08).

- Vorobev, V.; Safarov, I.; Mostovoy, P.; Shakirzyanov, L.; Fagereva, V. Best Practices of Exploration: Integration of Seismic and Electrical Prospecting; OnePetro, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Mogilatov, V.; Balashov, B. A New Method of Geoelectrical Prospecting by Vertical Electric Current Soundings. Journal of Applied Geophysics 1996, 36 (1), 31–41. [CrossRef]

- Afonin, A. G.; Butov, V. G.; Sinyaev, S. V.; Solonenko, V. A.; Shvetsov, G. A.; Stankevich, S. V. Rail Electromagnetic Launchers Powered by Pulsed MHD Generators. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2017, 45 (7), 1208–1212. [CrossRef]

- Esposito, N.; Raugi, M.; Tellini, A. MHD Generators as Pulse Power Sources for Arc-Driven Railguns. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 1995, 31 (1), 47–51. [CrossRef]

- Harada, Nob.; Hamada, R. Preparations for Studies on Space Application of MHD Generation and Acceleration. In 39th Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit; AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics]: Reno, Nevada, USA, 2001; p AIAA-2001-0797. [CrossRef]

- Zeigarnik, V. A.; Novikov, V. A.; Okunev, V. I.; Rickman, V. Yu. Potentialities of Application of Pulsed MHD Generators for Power Supply of Reusable Transport Space Systems with Horizontal Launching of Aerospace Plane. In 33rd Plasmadynamics and Lasers Conference; AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics]: Maui, Hawaii, USA, 2002; p AIAA 2002-2190. [CrossRef]

- Litchford, R.; Jones, J. E.; Dobson, C. C.; Cole, J. W.; Thompson, B. R.; Plemmons, D. H.; Turner, M. W. Pulse Detonation Rocket MHD Power Experiment. In 33rd Plasmadynamics and Lasers Conference; AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics]: Maui, Hawaii, USA, 2002; p AIAA 2002-2231. [CrossRef]

- Saurabh, A.; Turan, A. Computational Analysis of 3D-Flows in Rocket Produced H2/H2O Plasma Based MHD Generators for Space Applications. International Journal of Space Science and Engineering 2013, 1 (3), 290–310. [CrossRef]

- Sugita, H.; Matsuo, T.; Inui, Y.; Ishikawa, M. Two-Dimensional Analysis of Gas-Particle Two Phase Flow in Pulsed MHD Channel. In 30th Plasmadynamic and Lasers Conference; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Norfolk, Virginia, USA, 1999; p AIAA-99-3483. [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, T.; Sugita, H.; Ishikawa, M.; Zeigarnik, V. A. Boundary-Layer Separation and Generator Performance of Self-Excited Pulsed MHD Channel with Strong MHD Interaction. In 13th International Conference on MHD Electrical Power Generation and High Temperature Technologies; Beijing, China, 1999; Vol. 2, pp 399–408.

- Babakov, Ju.; Eremenko, V.; Krivosheev, N.; Kuzmin, R.; Poljakov, V.; Pisakin, A. Powerful Self-Contained Solid Propellant Fueled MHD Generator “Sojuz” for Area and Deep Geoelectrical Prospecting. In 12th International Conference on MHD Electrical Power Generation; Yokohama, Japan, 1996; Vol. 1, pp 445–450.

- Novikov, V. A.; Okunev, V. I.; Rickman, V. Yu. 51. Feasibility Study of Application of Pulsed MHD Generators for Power Supply of Nasa Maglev Launch-Assist Electromagnetic Tracks. In 3th Workshop on Magnetoplasma Aerodynamics for Aerospace Applications; Moscow, Russia, 2001; pp 273–275.

- Velikhov, E. P.; Panchenko, V. P. Large-Scale Geophysical Surveys of the Earth’s Crust Using High-Power Electromagnetic Pulses. In Handbook of Geophysical Exploration: Seismic Exploration; Elsevier, 2010; Vol. 40, pp 29–53. [CrossRef]

- Sugita, H.; Matsuo, T.; Inui, Y.; Ishikawa, M. Two-Dimensional Behavior of Gas-Particle Two-Phase Flow under Strong MHD Interaction. In 13th International Conference on MHD Electrical Power Generation and High Temperature Technologies; Beijing, China, 1999; Vol. 2, pp 453–462.

- Kayukawa, N. Open-Cycle Magnetohydrodynamic Electrical Power Generation: A Review and Future Perspectives. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 2004, 30 (1), 33–60. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Hydrogen Utilization as a Plasma Source for Magnetohydrodynamic Direct Power Extraction (MHD-DPE). IEEE Access 2024, 12, 167088–167107. [CrossRef]

- WILSON, W. W.; SINGH, J. P.; YUEH, F. Y.; BAUMAN, L. E.; GEORGE, A.; COOK, R. L.; LEE, J. J.; LINEBERRY, J. T. Comparison of Velocity and Temperature Measurements in an MHD Topping Cycle Environment With Flow Field Model Calculations. Combustion Science and Technology 1995, 109 (1–6), 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Hustad, C.-W.; Coleman, D. L.; Mikus, T. Technology Overview for Integration of an MHD Topping Cycle with the CES Oxyfuel Combustor; Final Report; CO2-Global, 2009. https://co2.no/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/MHD_Report-Final.pdf (accessed 2011-06-12).

- Marzouk, O. A. Power Density and Thermochemical Properties of Hydrogen Magnetohydrodynamic (H2MHD) Generators at Different Pressures, Seed Types, Seed Levels, and Oxidizers. Hydrogen 2025, 6 (2), 31. [CrossRef]

- Bünde, R.; Muntenbruch, H.; Raeder, J.; Volk, R.; Zankl, G. MHD Power Generation: Selected Problems of Combustion MHD Generators; Raeder, J., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, 1975.

- Marzouk, O. A. Temperature-Dependent Functions of the Electron–Neutral Momentum Transfer Collision Cross Sections of Selected Combustion Plasma Species. Applied Sciences 2023, 13 (20), 11282. [CrossRef]

- Mori, Y.; Ohtake, K.; Yamamoto, M.; Imani, K. Thermodynamic and Electrical Properties of Combustion Gas and Its Plasma : 1st Report, Theoretical Calculation. Bulletin of JSME 1968, 11 (44), 241–252. [CrossRef]

- Kittijungjit, T.; Klamrassamee, T.; Laoonual, Y.; Sukjai, Y. Comprehensive Study on Waste Heat Recovery from Gas Turbine Exhaust Using Combined Steam Rankine and Organic Rankine Cycles. Energy Conversion and Management: X 2025, 25, 100825. [CrossRef]

- Boretti, A. Combined Cycle Gas Turbine (CCGT) Plants Utilizing Methane-Hydrogen Blends Represent a Significant Element in Australia’s Journey toward Achieving Net-Zero Emissions. Fuel 2025, 381, 133339. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Cantera-Based Python Computer Program for Solving Steam Power Cycles with Superheating. International Journal of Emerging Technology and Advanced Engineering 2023, 13 (3), 63–73. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Al Kamzari, A. A.; Al-Hatmi, T. K.; Al Alawi, O. S.; Al-Zadjali, H. A.; Al Haseed, M. A.; Al Daqaq, K. H.; Al-Aliyani, A. R.; Al-Aliyani, A. N.; Al Balushi, A. A.; Al Shamsi, M. H. Energy Analyses for a Steam Power Plant Operating under the Rankine Cycle. In First International Conference on Engineering, Applied Sciences and Management (UoB-IEASMA 2021); Al Kalbani, A. S., Kanna, R., EP Rabai, L. B., Ahmad, S., Valsala, S., Eds.; IEASMA Consultants LLP: Virtual, 2021; pp 11–22. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Assessment of Global Warming in Al Buraimi, Sultanate of Oman Based on Statistical Analysis of NASA POWER Data over 39 Years, and Testing the Reliability of NASA POWER against Meteorological Measurements. Heliyon 2021, 7 (3), e06625. [CrossRef]

- Meinshausen, M.; Meinshausen, N.; Hare, W.; Raper, S. C. B.; Frieler, K.; Knutti, R.; Frame, D. J.; Allen, M. R. Greenhouse-Gas Emission Targets for Limiting Global Warming to 2 °C. Nature 2009, 458 (7242), 1158–1162. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Chronologically-Ordered Quantitative Global Targets for the Energy-Emissions-Climate Nexus, from 2021 to 2050. In 2022 International Conference on Environmental Science and Green Energy (ICESGE); IEEE [Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers]: Shenyang, China (and Virtual), 2022; pp 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Zero Carbon Ready Metrics for a Single-Family Home in the Sultanate of Oman Based on EDGE Certification System for Green Buildings. Sustainability 2023, 15 (18), 13856. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Evolution of the (Energy and Atmosphere) Credit Category in the LEED Green Buildings Rating System for (Building Design and Construction: New Construction), from Version 4.0 to Version 4.1. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development 2024, 8 (8), 5306. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, T.; Lee, I.; Park, J. Liquid Air Energy Storage System with Oxy-Fuel Combustion for Clean Energy Supply: Comprehensive Energy Solutions for Power, Heating, Cooling, and Carbon Capture. Applied Energy 2025, 379, 124937. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Technical Review of Radiative-Property Modeling Approaches for Gray and Nongray Radiation, and a Recommended Optimized WSGGM for CO2/H2O-Enriched Gases. Results in Engineering 2025, 25, 103923. [CrossRef]

- Raho, B.; Giangreco, M.; Colangelo, G.; Milanese, M.; de Risi, A. Technological, Economic, and Emission Analysis of the Oxy-Combustion Process. Applied Energy 2025, 378, 124821. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Radiant Heat Transfer in Nitrogen-Free Combustion Environments. International Journal of Nonlinear Sciences and Numerical Simulation 2018, 19 (2), 175–188. [CrossRef]

- Ork, K.; Masuda, R.; Okuno, Y. Fundamental Experiment and Numerical Simulation of Ne/Xe Plasma Magnetohydrodynamic Electrical Power Generation. Journal of Propulsion and Power 2024, 40 (3), 368–379. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Adiabatic Flame Temperatures for Oxy-Methane, Oxy-Hydrogen, Air-Methane, and Air-Hydrogen Stoichiometric Combustion Using the NASA CEARUN Tool, GRI-Mech 3.0 Reaction Mechanism, and Cantera Python Package. Engineering, Technology & Applied Science Research 2023, 13 (4), 11437–11444. [CrossRef]

- Bian, J.-Y.; Guo, X.-Y.; Lee, D. H.; Sun, X.-R.; Liu, L.-S.; Shao, K.; Liu, K.; Sun, H.-N.; Kwon, T. Non-Thermal Plasma Enhances Rice Seed Germination, Seedling Development, and Root Growth under Low-Temperature Stress. Appl Biol Chem 2024, 67 (1), 2. [CrossRef]

- Guragain, R. P.; Kierzkowska-Pawlak, H.; Fronczak, M.; Kędzierska-Sar, A.; Subedi, D. P.; Tyczkowski, J. Germination Improvement of Fenugreek Seeds with Cold Plasma: Exploring Long-Lasting Effects of Surface Modification. Scientia Horticulturae 2024, 324, 112619. [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, H.; Mahmoudi, M.; Ghodusinejad, M. H. Modeling and Sensitivity Analysis of a Supersonic Inductive Magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) Generator. futech 2024, 3 (2), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Energy Generation Intensity (EGI) for Parabolic Dish/Engine Concentrated Solar Power in Muscat, Sultanate of Oman. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2022, 1008 (1), 012013. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cheng, K.; Xu, J.; Jing, W.; Huang, H.; Qin, J. Thermodynamic and Mass Analysis of a Novel Two-Phase Liquid Metal MHD Enhanced Energy Conversion System for Space Nuclear Power Source. Energy 2024, 308, 132860. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Land-Use Competitiveness of Photovoltaic and Concentrated Solar Power Technologies near the Tropic of Cancer. Solar Energy 2022, 243, 103–119. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Wind Speed Weibull Model Identification in Oman, and Computed Normalized Annual Energy Production (NAEP) From Wind Turbines Based on Data From Weather Stations. Engineering Reports 2025, 7 (3), e70089. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Shi, X. J.; Lu, X. Q.; Sun, W.; Liu, K. P.; Fei, Y. F. Study on Scuffing Failure of Gas Turbine Ball Bearing Based on 3D Mixed Lubrication and Dynamics. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part J: Journal of Engineering Tribology 2024, 238 (8), 897–911. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. One-Way and Two-Way Couplings of CFD and Structural Models and Application to the Wake-Body Interaction. Applied Mathematical Modelling 2011, 35 (3), 1036–1053. [CrossRef]

- Gbashi, S. M.; Olatunji, O. O.; Adedeji, P. A.; Madushele, N. From Academic to Industrial Research: A Comparative Review of Advances in Rolling Element Bearings for Wind Turbine Main Shaft. Engineering Failure Analysis 2024, 163, 108510. [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Lozoya, J. C.; Domínguez-Lozoya, D. R.; Cuevas, S.; Ávalos-Zúñiga, R. A. MHD Generation for Sustainable Development, from Thermal to Wave Energy Conversion: Review. Sustainability 2024, 16 (22), 10041. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Lookup Tables for Power Generation Performance of Photovoltaic Systems Covering 40 Geographic Locations (Wilayats) in the Sultanate of Oman, with and without Solar Tracking, and General Perspectives about Solar Irradiation. Sustainability 2021, 13 (23), 13209. [CrossRef]

- P., R.; Barik, D.; S, S. K.; M., A. M.; Praveenkumar, S. Experimental Analysis on the Thermoelectric Effect of Various Solid-State Devices Used for Direct Conversion of Thermal Energy into Electrical Energy. Results in Engineering 2024, 23, 102752. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Tilt Sensitivity for a Scalable One-Hectare Photovoltaic Power Plant Composed of Parallel Racks in Muscat. Cogent Engineering 2022, 9 (1), 2029243. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Facilitating Digital Analysis and Exploration in Solar Energy Science and Technology through Free Computer Applications. Engineering Proceedings 2022, 31 (1), 75. [CrossRef]

- DEMIRBAS, A.; MEYDAN, F. Utilization of Biomass as Alternative Fuel for External Combustion Engines. Energy Sources 2004, 26 (13), 1219–1226. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Urban Air Mobility and Flying Cars: Overview, Examples, Prospects, Drawbacks, and Solutions. Open Engineering 2022, 12 (1), 662–679. [CrossRef]

- AERL, [Avco Everett Research Laboratory]. MHD Generator Component Development. Quarterly Report, January--March 1977; FE-2519-1, 5224888; Avco Everett Research Laboratory, Inc.: USA, 1977; p FE-2519-1, 5224888. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Jatropha Curcas as Marginal Land Development Crop in the Sultanate of Oman for Producing Biodiesel, Biogas, Biobriquettes, Animal Feed, and Organic Fertilizer. Reviews in Agricultural Science 2020, 8, 109–123. [CrossRef]

- Palmer, H.; Beér, J. M. Combustion Technology: Some Modern Developments; Elsevier: New York City, New York, USA, 2012.

- Marzouk, O. A. Energy Generation Intensity (EGI) of Solar Updraft Tower (SUT) Power Plants Relative to CSP Plants and PV Power Plants Using the New Energy Simulator “Aladdin.” Energies 2024, 17 (2), 405. [CrossRef]

- Patonia, A. Green Hydrogen and Its Unspoken Challenges for Energy Justice. Applied Energy 2025, 377, 124674. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Compilation of Smart Cities Attributes and Quantitative Identification of Mismatch in Rankings. Journal of Engineering 2022, 2022, 5981551. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Expectations for the Role of Hydrogen and Its Derivatives in Different Sectors through Analysis of the Four Energy Scenarios: IEA-STEPS, IEA-NZE, IRENA-PES, and IRENA-1.5°C. Energies 2024, 17 (3), 646. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Levelized Cost of Green Hydrogen (LCOH) in the Sultanate of Oman Using H2A-Lite with Polymer Electrolyte Membrane (PEM) Electrolyzers Powered by Solar Photovoltaic (PV) Electricity. E3S Web of Conferences 2023, 469, 00101. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. 2030 Ambitions for Hydrogen, Clean Hydrogen, and Green Hydrogen. Engineering Proceedings 2023, 56 (1), 14. [CrossRef]

- SCHMIDT, H.; LINEBERRY, J.; CRAWFORD, L. Design Criteria for High Performance MHD Generator Utilizing Energetic Fuels. In 25th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reno, Nevada, USA, 1987. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Portrait of the Decarbonization and Renewables Penetration in Oman’s Energy Mix, Motivated by Oman’s National Green Hydrogen Plan. Energies 2024, 17 (19), 4769. [CrossRef]

- Chapman, J.; Erb, D.; Crawford, L.; Johanson, N. Use of Natural Gas as Fuel for MHD Central Power Generation. In Intersociety Energy Conversion Engineering Conference; AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics]: Monterey, California, USA, 1994; p AIAA-94-3907-CP. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Performance Analysis of Shell-and-Tube Dehydrogenation Module. International Journal of Energy Research 2017, 41 (4), 604–610. [CrossRef]

- Way, S.; DeCorso, S. M.; Hundstad, R. L.; Kemeny, G. A.; Stewart, W.; Young, W. E. Experiments With MHD Power Generation. Journal of Engineering for Power 1961, 83 (4), 397–408. [CrossRef]

- Brogan, T. R.; Louis, J. F.; Ros, R. J.; Stekly, Z. J. J. A Review of Recent MHD Generator Work at the Avco-Everett Research Laboratory. In Third Symposium on the Engineering Aspects of Magnetohydrodynamics; Armed Services Technical Information Agency: Rochester, New York, USA, 1962; pp 1–20.

- Ibberson, V. J.; Beér, J. M.; Swithenbank, J.; Taylor, D. S.; Thring, M. W. A Combustion Oscillator for MHD Energy Conversion. Symposium (International) on Combustion 1971, 13 (1), 565–572. [CrossRef]

- Rosa, R. J. MHD Power Generation: State of the Art and Prospects for Advanced Nuclear Applications; Thom, K., Schneider, R. T., Eds.; NASA [United States National Aeronautics and Space Administration]: Gainesville, Florida, USA, 1970; pp 315–326.

- Galanga, F. L.; Lineberry, J. T.; Wu, Y. C. L.; Scott, M. H.; Baucum, W. E.; Clemons, R. W. Experimental Results of the UTSI Coal-Fired MHD Generator and Investigations of Various Power Take-off Schemes. In 19th Aerospace Sciences Meeting; AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics]: St. Louis, Missouri, USA, 1981. [CrossRef]

- Im, K. H.; Ahluwalia, R. K. Convective and Radiative Heat Transfer in MHD Radiant Boilers. Journal of Energy 1981, 5 (5), 308–314. [CrossRef]

- Donev et al, J. M. K. C. Energy Education │ Boiler slag. https://energyeducation.ca/encyclopedia/Boiler_slag (accessed 2025-02-10).

- Pintana, P.; Tippayawong, N.; Nuntaphun, A.; Thongchiew, P. Characterization of Slag from Combustion of Pulverized Lignite with High Calcium Content in Utility Boiler. Energy Exploration & Exploitation 2014, 32 (3), 471–482. [CrossRef]

- Greenshields, C. OpenFOAM v12 User Guide. CFD Direct. https://doc.cfd.direct/openfoam/user-guide-v12/programming-language-openfoam (accessed 2025-02-18).

- Greenshields, C. OpenFOAM User Guide; The OpenFOAM Foundation: London, UK, 2024; Vol. 12.

- OpenCFD. OpenFOAM® Documentation. https://www.openfoam.com/documentation/overview (accessed 2024-11-19).

- Jasak, H. OpenFOAM: Open Source CFD in Research and Industry. International Journal of Naval Architecture and Ocean Engineering 2009, 1 (2), 89–94. [CrossRef]

- Weller, H. G.; Tabor, G.; Jasak, H.; Fureby, C. A Tensorial Approach to Computational Continuum Mechanics Using Object-Oriented Techniques. Computer in Physics 1998, 12 (6), 620–631. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Reduced-Order Modeling (ROM) of a Segmented Plug-Flow Reactor (PFR) for Hydrogen Separation in Integrated Gasification Combined Cycles (IGCC). Processes 2025, 13 (5), 1455. [CrossRef]

- Lysenko, D. A.; Ertesvåg, I. S.; Rian, K. E. Modeling of Turbulent Separated Flows Using OpenFOAM. Computers & Fluids 2013, 80, 408–422. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Huckaby, E. D. Modeling Confined Jets with Particles and Swril. In Machine Learning and Systems Engineering; Ao, S.-I., Rieger, B., Amouzegar, M. A., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2010; Vol. 68, pp 243–256. [CrossRef]

- Robertson, E.; Choudhury, V.; Bhushan, S.; Walters, D. K. Validation of OpenFOAM Numerical Methods and Turbulence Models for Incompressible Bluff Body Flows. Computers & Fluids 2015, 123, 122–145. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Huckaby, E. D. Assessment of Syngas Kinetic Models for the Prediction of a Turbulent Nonpremixed Flame. In Fall Meeting of the Eastern States Section of the Combustion Institute 2009; College Park, Maryland, USA, 2009; pp 726–751. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L. F.; Zang, J.; Hillis, A. J.; Morgan, G. C. J.; Plummer, A. R. Numerical Investigation of Wave–Structure Interaction Using OpenFOAM. Ocean Engineering 2014, 88, 91–109. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Wang, M.; Gan, F.; Tian, W.; Qiu, S.; Su, G. H. Numerical Investigation of Flow and Heat Transfer Characteristics in Plate-Type Fuel Channels of IAEA MTR Based on OpenFOAM. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2021, 141, 103963. [CrossRef]

- Cockburn, B.; Coquel, F.; LeFloch, P. G. Convergence of the Finite Volume Method for Multidimensional Conservation Laws. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 1995, 32 (3), 687–705. [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekar, P.; Garg, A. Vertex-Centroid Finite Volume Scheme on Tetrahedral Grids for Conservation Laws. Computers & Mathematics with Applications 2013, 65 (1), 58–74. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Nayfeh, A. H. Control of Ship Roll Using Passive and Active Anti-Roll Tanks. Ocean Engineering 2009, 36 (9), 661–671. [CrossRef]

- Shahidian, A.; Ghassemi, M. Effect of Magnetic Flux Density and Other Properties on Temperature and Velocity Distribution in Magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) Pump. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 2009, 45 (1), 298–301. [CrossRef]

- Sriram, A. T.; Chakraborty, D. Numerical Exploration of Staged Transverse Injection into Confined Supersonic Flow behind a Backward-Facing Step. Defence Science Journal 2011, 61 (1), 3–11.

- Marzouk, O. A. Flow Control Using Bifrequency Motion. Theoretical and Computational Fluid Dynamics 2011, 25 (6), 381–405. [CrossRef]

- Pirumov, U. G. Three-Dimensional Sub- and Supersonic Flows in Nozzles and Channels of Varying Cross Section: PMM Vol. 36, N≗2, 1972, Pp.239–247. Journal of Applied Mathematics and Mechanics 1972, 36 (2), 220–229. [CrossRef]

- Nibedita, B.; Irfan, M. Energy Mix Diversification in Emerging Economies: An Econometric Analysis of Determinants. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2024, 189, 114043. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Globalization and Diversity Requirement in Higher Education. In The 11th World Multi-Conference on Systemics, Cybernetics and Informatics (WMSCI 2007) - The 13th International Conference on Information Systems Analysis and Synthesis (ISAS 2007); IIIS [International Institute of Informatics and Systemics]: Orlando, Florida, USA, 2007; Vol. III (3), pp 101–106.

- Marzouk, O. A. In the Aftermath of Oil Prices Fall of 2014/2015–Socioeconomic Facts and Changes in the Public Policies in the Sultanate of Oman. International Journal of Management and Economics Invention 2017, 3 (11), 1463–1479. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Benchmarking the Trends of Urbanization in the Gulf Cooperation Council: Outlook to 2050. In 1st National Symposium on Emerging Trends in Engineering and Management (NSETEM’2017); WCAS [Waljat College of Applied Sciences], Muscat, Oman, 2017; pp 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Lineberry, J. T.; Schmidt, H. J.; Chapman, J. N. Experimental Program for Investigation of High Power Density MHD. In Proceedings of the 24th Intersociety Energy Conversion Engineering Conference; 1989; pp 1085–1090 vol.2. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H. J.; Lineberry, J. T.; Chapman, J. N. An Innovative Demonstration of High Power Density in a Compact MHD (Magnetohydrodynamic) Generator; DOE/PC/79678-T4; Tennessee Univ., Tullahoma, TN (USA). Space Inst., 1990. [CrossRef]

- SCHMIDT, H.; LINEBERRY, J.; CHAPMAN, J. High-Power Density MHD Experiments. In 28th Aerospace Sciences Meeting; AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics]: Reno, Nevada, USA, 1990. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Aerial E-Mobility Perspective: Anticipated Designs and Operational Capabilities of eVTOL Urban Air Mobility (UAM) Aircraft. Edelweiss Applied Science and Technology 2025, 9 (1), 413–442. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Growth in the Worldwide Stock of E-Mobility Vehicles (by Technology and by Transport Mode) and the Worldwide Stock of Hydrogen Refueling Stations and Electric Charging Points between 2020 and 2022. In Construction Materials and Their Processing; Key Engineering Materials; Trans Tech Publications Ltd: Baech (Bäch), Switzerland, 2023; Vol. 972, pp 89–96.

- Marzouk, O. A. Toward More Sustainable Transportation: Green Vehicle Metrics for 2023 and 2024 Model Years. In Intelligent Sustainable Systems; Nagar, A. K., Jat, D. S., Mishra, D. K., Joshi, A., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2024; Vol. 817, pp 261–272. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Recommended LEED-Compliant Cars, SUVs, Vans, Pickup Trucks, Station Wagons, and Two Seaters for Smart Cities Based on the Environmental Damage Index (EDX) and Green Score. In Innovations in Smart Cities Applications Volume 7; Ben Ahmed, M., Boudhir, A. A., El Meouche, R., Karaș, İ. R., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Vol. 906, pp 123–135. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Summary of the 2023 (1st Edition) Report of TCEP (Tracking Clean Energy Progress) by the International Energy Agency (IEA), and Proposed Process for Computing a Single Aggregate Rating. E3S Web of Conferences 2025, 601, 00048. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Status of ABET Accreditation in the Arab World. Global Journal of Educational Studies 2019, 5 (1), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Accrediting Artificial Intelligence Programs from the Omani and the International ABET Perspectives. In Intelligent Computing; Arai, K., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Vol. 285, pp 462–474. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Utilizing Co-Curricular Programs to Develop Student Civic Engagement and Leadership. The Journal of the World Universities Forum 2008, 1 (5), 87–100. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. English Programs for Non-English Speaking College Students. In 1st Knowledge Globalization Conference 2008 (KGLOBAL 2008); Sawyer Business School, Suffolk University: Boston, Massachusetts, USA, 2008; pp 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. University Role in Promoting Leadership and Commitment to the Community. In Inaugural International Forum on World Universities; Davos, Switzerland, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Benchmarking Retention, Progression, and Graduation Rates in Undergraduate Higher Education Across Different Time Windows. Cogent Education 2025, 12 (1), 2498170. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Detailed Derivation of the Scalar Explicit Expressions Governing the Electric Field, Current Density, and Volumetric Power Density in the Four Types of Linear Divergent MHD Channels Under a Unidirectional Applied Magnetic Field. Contemporary Mathematics 2025, 6 (4), 4060–4100. [CrossRef]

- Choubey, G.; Tiwari, M. Chapter Six - Pedagogy for the Computational Approach in Simulating Supersonic Flows. In Scramjet Combustion; Choubey, G., Tiwari, M., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann, 2022; pp 163–181. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Rodriguez, L. F.; Alonso, D. H.; Silva, E. C. N. Turbulence Effects in the Topology Optimization of Compressible Subsonic Flow. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Fluids 2025, 97 (1), 44–68. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Nayfeh, A. H. Reduction of the Loads on a Cylinder Undergoing Harmonic In-Line Motion. Physics of Fluids 2009, 21 (8), 083103. [CrossRef]

- Lodares, D.; Manzanero, J.; Ferrer, E.; Valero, E. An Entropy–Stable Discontinuous Galerkin Approximation of the Spalart–Allmaras Turbulence Model for the Compressible Reynolds Averaged Navier–Stokes Equations. Journal of Computational Physics 2022, 455, 110998. [CrossRef]

- Blazek, J. Chapter 7 - Turbulence Modeling. In Computational Fluid Dynamics: Principles and Applications (Third Edition); Blazek, J., Ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, 2015; pp 213–252. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Nayfeh, A. H. Characterization of the Flow over a Cylinder Moving Harmonically in the Cross-Flow Direction. International Journal of Non-Linear Mechanics 2010, 45 (8), 821–833. [CrossRef]

- Baker, C.; Johnson, T.; Flynn, D.; Hemida, H.; Quinn, A.; Soper, D.; Sterling, M. Chapter 4 - Computational Techniques. In Train Aerodynamics; Baker, C., Johnson, T., Flynn, D., Hemida, H., Quinn, A., Soper, D., Sterling, M., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann, 2019; pp 53–71. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Simulation, Modeling, and Characterization of the Wakes of Fixed and Moving Cylinders. PhD in Engineering Mechanics, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (Virginia Tech), Blacksburg, Virginia, USA, 2009. http://hdl.handle.net/10919/26316 (accessed 2024-11-26).

- Majda, A. Compressible Fluid Flow and Systems of Conservation Laws in Several Space Variables; Springer Science & Business Media, 2012.

- Marzouk, O. A. Direct Numerical Simulations of the Flow Past a Cylinder Moving With Sinusoidal and Nonsinusoidal Profiles. Journal of Fluids Engineering 2009, 131 (12), 121201. [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, C. A. J. Computational Techniques for Fluid Dynamics - Volume II: Specific Techniques for Different Flow Categories, 2nd ed.; Scientific Computation; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1991. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Characteristics of the Flow-Induced Vibration and Forces With 1- and 2-DOF Vibrations and Limiting Solid-to-Fluid Density Ratios. Journal of Vibration and Acoustics 2010, 132 (4), 041013. [CrossRef]

- Rothan, Y. A. Thermal Management of Nanofluid Flow through Porous Container with Impose of Lorentz Force. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering 2024, 60, 104779. [CrossRef]

- Bereanu, C. Interactions in the Lorentz Force Equation. Calc. Var. 2024, 63 (2), 29. [CrossRef]

- Mansour, K.; Khorsandi, M. The Drag Reduction in Spherical Spiked Blunt Body. Acta Astronautica 2014, 99, 92–98. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Nayfeh, A. H. A Study of the Forces on an Oscillating Cylinder. In ASME 2007 26th International Conference on Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering (OMAE 2007); ASME [American Society of Mechanical Engineers]: San Diego, California, USA, 2009; pp 741–752. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, J.; Xie, C.; Zhao, H. CFD-DEM Simulation on the Main-Controlling Factors Affecting Proppant Transport in Three-Dimensional Rough Fractures of Offshore Unconventional Reservoirs. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2024, 12 (12), 2117. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Contrasting the Cartesian and Polar Forms of the Shedding-Induced Force Vector in Response to 12 Subharmonic and Superharmonic Mechanical Excitations. Fluid Dynamics Research 2010, 42 (3), 035507. [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Dasi, L. P.; Sotiropoulos, F.; Yoganathan, A. P. Characterization of Hemodynamic Forces Induced by Mechanical Heart Valves: Reynolds vs. Viscous Stresses. Ann Biomed Eng 2008, 36 (2), 276–297. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Nayfeh, A. H. New Wake Models With Capability of Capturing Nonlinear Physics. In ASME 2008 27th International Conference on Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering (OMAE 2008); ASME [American Society of Mechanical Engineers]: Estoril, Portugal, 2009; pp 901–912. [CrossRef]

- Grosse, A. V. The Reduced Dynamic (Absolute) and Kinematic Viscosities of the Metals—Mercury, Sodium and Potassium—over Their Entire Liquid Range, i.e., from the Melting Point to the Critical Point, and a Comparison with van Der Waals’ Substances. Journal of Inorganic and Nuclear Chemistry 1965, 27 (5), 979–987. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Nayfeh, A. H. Loads on a Harmonically Oscillating Cylinder. In ASME 2007 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference (IDETC-CIE 2007); ASME [American Society of Mechanical Engineers]: Las Vegas, Nevada, USA, 2009; pp 1755–1774. [CrossRef]

- Smith, J. D.; Lorra, M.; Hixson, E. M.; Eldredge, T. 5 CFD in Burner Development. In Industrial Burners Handbook; Baukal, J., Charles E., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, Florida, USA, 2003; pp 145–188.

- Weinert, U. Spherical Tensor Representation. Arch. Rational Mech. Anal. 1980, 74 (2), 165–196. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Nayfeh, A. H. Hydrodynamic Forces on a Moving Cylinder with Time-Dependent Frequency Variations. In 46th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit; AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics]: Reno, Nevada, USA, 2008; p AIAA 2008-680. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Kozul, M.; Li, W.; Sandberg, R. D. Eddy-Viscosity-Improved Resolvent Analysis of Compressible Turbulent Boundary Layers. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2024, 983, A46. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. A Nonlinear ODE System for the Unsteady Hydrodynamic Force - A New Approach. World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology 2009, 39, 948–962. [CrossRef]

- Kosker, M.; Yilmaz, F. The Cross-Sectional Curvature Effect of Twisted Tapes on Heat Transfer Performance. Chemical Engineering and Processing - Process Intensification 2020, 154, 108008. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Nayfeh, A. H. Fluid Forces and Structure-Induced Damping of Obliquely-Oscillating Offshore Structures. In The Eighteenth (2008) International Offshore and Polar Engineering Conference (ISOPE-2008); ISOPE [International Society of Offshore and Polar Engineers]: Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, 2008; Vol. 3, pp 460–468.

- Hu, X. Y.; Adams, N. A. A SPH Model for Incompressible Turbulence. Procedia IUTAM 2015, 18, 66–75. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Nayfeh, A. H. A Parametric Study and Optimization of Ship-Stabilization Systems. In 1st WSEAS International Conference on Maritime and Naval Science and Engineering (MN’08); WSEAS [World Scientific and Engineering Academy and Society]: Malta, 2008; pp 169–174. [CrossRef]

- Linke, A. A Divergence-Free Velocity Reconstruction for Incompressible Flows. Comptes Rendus Mathematique 2012, 350 (17), 837–840. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Nayfeh, A. H. Mitigation of Ship Motion Using Passive and Active Anti-Roll Tanks. In ASME 2007 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference (IDETC-CIE 2007); ASME [American Society of Mechanical Engineers]: Las Vegas, Nevada, USA, 2009; pp 215–229. [CrossRef]

- Ashwin Ganesh, M.; John, B. Concentrated Energy Addition for Active Drag Reduction in Hypersonic Flow Regime. Acta Astronautica 2018, 142, 221–231. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. A Two-Step Computational Aeroacoustics Method Applied to High-Speed Flows. Noise Control Engineering Journal 2008, 56 (5), 396. [CrossRef]

- Camberos, J. Energy Analysis Applied to External Aerodynamics of High-Speed Flow. In 9th AIAA/ASME Joint Thermophysics and Heat Transfer Conference; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: San Francisco, California, USA, 2006; p AIAA 2006-2943. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Directivity and Noise Propagation for Supersonic Free Jets. In 46th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit; AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics]: Reno, Nevada, USA, 2008; p AIAA 2008-23. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Accurate Prediction of Noise Generation and Propagation. In 18th Engineering Mechanics Division Conference of the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE-EMD); Zenodo: Blacksburg, Virginia, USA, 2007; pp 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Foundations to Heat Transfer, 6. ed., internat. student version.; Incropera, F. P., DeWitt, D. P., Bergman, T. L., Lavine, A. S., Eds.; Wiley: Singapore, 2013.

- Schlichting, H.; Gersten, K. Boundary-Layer Theory; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2000. [CrossRef]

- Schwab, A.; Fuchs, C.; Kistenmacher, P. Semantics of the Irrotational Component of the Magnetic Vector Potential, A. IEEE Antennas and Propagation Magazine 1997, 39 (1), 46–51. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Airfoil Design Using Genetic Algorithms. In The 2007 International Conference on Scientific Computing (CSC’07), The 2007 World Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering, and Applied Computing (WORLDCOMP’07); CSREA Press: Las Vegas, Nevada, USA, 2007; pp 127–132. [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, T. Electrostatic Field. In Electricity and Magnetism: New Formulation by Introduction of Superconductivity; Matsushita, T., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp 3–32. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Detailed and Simplified Plasma Models in Combined-Cycle Magnetohydrodynamic Power Systems. International Journal of Advanced and Applied Sciences 2023, 10 (11), 96–108. [CrossRef]

- Laney, C. B. Computational Gasdynamics, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: USA, 1998. [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, J. F.; Barnard, J. A. Flame and Combustion, 3rd ed.; Routledge: Boca Raton, Florida, USA, 1995.

- Marzouk, O. A. Noise Emissions from Excited Jets. In 22nd National Conference on Noise Control Engineering (NOISE-CON 2007); INCE [Institute of Noise Control Engineering]: Reno, Nevada, USA, 2007; pp 1034–1045. [CrossRef]

- Zucker, R. D.; Biblarz, O. Fundamentals of Gas Dynamics; John Wiley & Sons: USA, 2019; Vol. 3.

- Marzouk, O. A. Investigation of Strouhal Number Effect on Acoustic Fields. In 22nd National Conference on Noise Control Engineering (NOISE-CON 2007); INCE [Institute of Noise Control Engineering]: Reno, Nevada, USA, 2007; pp 1056–1067. [CrossRef]

- Struchtrup, H. Thermodynamics and Energy Conversion, 1st ed.; Thermodynamics and Energy Conversion; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2014.

- Marzouk, O. A. Changes in Fluctuation Waves in Coherent Airflow Structures with Input Perturbation. WSEAS Transactions on Signal Processing 2008, 4 (10), 604–614. [CrossRef]

- Poinsot, T.; Veynante, D. Theoretical and Numerical Combustion, 2nd ed.; Edwards: Philadelphia, 2005.

- Warnatz, J.; Maas, U.; Dibble, R. W. Combustion - Physical and Chemical Fundamentals, Modeling and Simulation, Experiments, Pollutant Formation, 4th ed.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Germany, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Assessment of Three Databases for the NASA Seven-Coefficient Polynomial Fits for Calculating Thermodynamic Properties of Individual Species. International Journal of Aeronautical Science & Aerospace Research 2018, 5 (1), 150–163. [CrossRef]

- Kuo, K. K. Principles of Combustion, 2nd ed.; John Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, 2005.

- Sultanian, B. K.; Sultanian, B. K. Potential Flow. In Fluid Mechanics and Turbomachinery; CRC Press: Boca Raton, Florida, USA, 2021.

- Durst, F. Potential Flows. In Fluid Mechanics: An Introduction to the Theory of Fluid Flows; Durst, F., Ed.; Springer: Germany, 2022; pp 327–363. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Evolutionary Computing Applied to Design Optimization. In ASME 2007 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference (IDETC-CIE 2007), (4–7 September 2007); ASME [American Society of Mechanical Engineers]: Las Vegas, Nevada, USA, 2009; Vol. 2, pp 995–1003. [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, M. Potential Flow Theory. In Theoretical and Experimental Aerodynamics; Kaushik, M., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp 107–126. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Multi-Physics Mathematical Model of Weakly-Ionized Plasma Flows. American Journal of Modern Physics 2018, 7 (2), 87–102. [CrossRef]

- Cappelli, M.; Meezan, N.; Gascon, N. Transport Physics in Hall Plasma Thrusters. In 40th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting & Exhibit; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reno, Nevada, USA, 2002; p AIAA-2002-0485. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, B. P.; Wardle, M. Hall Magnetohydrodynamics of Partially Ionized Plasmas. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2008, 385 (4), 2269–2278. [CrossRef]

- Meezan, N. B.; Hargus, W. A.; Cappelli, M. A. Anomalous Electron Mobility in a Coaxial Hall Discharge Plasma. Phys. Rev. E 2001, 63 (2), 026410. [CrossRef]

- Levy-Nathansohn, T. Studies of the Generalized Ohm’s Law. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 1997, 241 (1), 166–172. [CrossRef]

- Parent, B.; Shneider, M. N.; Macheret, S. O. Generalized Ohm’s Law and Potential Equation in Computational Weakly-Ionized Plasmadynamics. Journal of Computational Physics 2011, 230 (4), 1439–1453. [CrossRef]

- Knaepen, B.; Moreau, R. Magnetohydrodynamic Turbulence at Low Magnetic Reynolds Number. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 2008, 40 (Volume 40, 2008), 25–45. [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Choi, H. Magnetohydrodynamic Turbulent Flow in a Channel at Low Magnetic Reynolds Number. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2001, 439, 367–394. [CrossRef]

- Khan, O.; Hoffmann, K.; Dietiker, J.-F. Validity of Low Magnetic Reynolds Number Formulation of Magnetofluiddynamics. In 38th Plasmadynamics and Lasers Conference; AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics]: Miami, Florida, USA, 2007; p AIAA 2007-4374. [CrossRef]

- Oeveren, S. B. van; Gildfind, D.; Wheatley, V.; Gollan, R.; Jacobs, P. Numerical Study of Magnetic Field Deformation for a Blunt Body with an Applied Magnetic Field During Atmospheric Entry. In AIAA SCITECH 2024 Forum; AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics]: Orlando, Florida, USA, 2024; p AIAA 2024-1646. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, P. A. An Introduction to Magnetohydrodynamics; Cambridge University Press: USA, 2001.

- Rosa, R. J.; Krueger, C. H.; Shioda, S. Plasmas in MHD Power Generation. IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science 1991, 19 (6), 1180–1190. [CrossRef]

- Smolentsev, S.; Cuevas, S.; Beltrán, A. Induced Electric Current-Based Formulation in Computations of Low Magnetic Reynolds Number Magnetohydrodynamic Flows. Journal of Computational Physics 2010, 229 (5), 1558–1572. [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, C. D.; Demetriades, S. T. Initial Tests of a Lightweight, Self-Excited MHD Power Generator. Journal of Propulsion and Power 1986, 2 (5), 474–480. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S. V. Redefining the Base Units. In Mass Metrology: The Newly Defined Kilogram; Gupta, S. V., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp 365–384. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. X. J.; Hoshino, K. Chapter 3 - Microfluidics and Micro Total Analytical Systems. In Molecular Sensors and Nanodevices; Zhang, J. X. J., Hoshino, K., Eds.; William Andrew Publishing: Oxford, 2014; pp 103–168. [CrossRef]

- NIST, [United States National Institute of Standards and Technology]. CODATA [Committee on Data for Science and Technology] Value: vacuum magnetic permeability. https://physics.nist.gov/cgi-bin/cuu/Value?mu0 (accessed 2025-02-16).

- ALPINIERI, L. J. Turbulent Mixing of Coaxial Jets. AIAA Journal 1964, 2 (9), 1560–1567. [CrossRef]

- Purcell, E. M. Life at Low Reynolds Number. In Physics and Our World; WORLD SCIENTIFIC, 2012; pp 47–67. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Al Badi, O. R. H.; Al Rashdi, M. H. S.; Al Balushi, H. M. E. Proposed 2MW Wind Turbine for Use in the Governorate of Dhofar at the Sultanate of Oman. Science Journal of Energy Engineering 2019, 7 (2), 20–28. [CrossRef]

- Messerle, H. K. Magnetohydrodynamic Electrical Power Generation; Unesco energy engineering series Energy engineering learning package; Wiley: Chichester, England, UK, 1995.

- Aithal, S. M. Characteristics of Optimum Power Extraction in a MHD Generator with Subsonic and Supersonic Inlets. Energy Conversion and Management 2009, 50 (3), 765–771. [CrossRef]

- Tillack, M. S.; Morley, N. B. Magnetohydrodynamics. In Standard Handbook for Electrical Engineers; Fink, D. G., Beaty, H. W., Eds.; McGraw Hill: New York, USA, 2000; p 11.109-11.144.

- Koshiba, Y.; Yuhara, M.; Ishikawa, M. Two-Dimensional Analysis of Effects of Induced Magnetic Field on Generator Performance of a Large-Scale Pulsed MHD Generator. In 35th AIAA Plasmadynamics and Lasers Conference; AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics]: Portland, Oregon, USA, 2004; p AIAA-2004-2368. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, K. A.; Chiang, S. T. Computational Fluid Dynamics - Volume 1, 4. ed., 2. print.; Engineering Education System: Wichita, Kansas, USA, 2004.

- Marzouk, O.; Nayfeh, A. Differential/Algebraic Wake Model Based on the Total Fluid Force and Its Direction, and the Effect of Oblique Immersed-Body Motion on `Type-1’ and `Type-2’ Lock-In. In 47th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting including The New Horizons Forum and Aerospace Exposition; AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics]: Orlando, Florida, USA, 2009; p AIAA 2009-1112. [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, C. A. J. Computational Techniques for Fluid Dynamics - Volume I: Fundamental and General Techniques, 2nd ed.; Springer series in computational physics; Springer-Verlag: Berlin Heidelberg New York, 1991.

- Faust, E.; Schlüter, A.; Müller, H.; Steinmetz, F.; Müller, R. Dirichlet and Neumann Boundary Conditions in a Lattice Boltzmann Method for Elastodynamics. Comput Mech 2024, 73 (2), 317–339. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.; Nayfeh, A. Physical Interpretation of the Nonlinear Phenomena in Excited Wakes. In 46th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit; AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics]: Reno, Nevada, USA, 2008; p AIAA 2008-1304. [CrossRef]

- Le, M. Global Existence of Solutions in Some Chemotaxis Systems with Sub-Logistic Source under Nonlinear Neumann Boundary Conditions in 2d. Nonlinear Analysis 2024, 241, 113491. [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, J. F.; Johnson, C. R. Hexahedral Mesh Generation Constraints. Engineering with Computers 2008, 24 (3), 195–213. [CrossRef]

- Biswas, R.; Strawn, R. C. Tetrahedral and Hexahedral Mesh Adaptation for CFD Problems. Applied Numerical Mathematics 1998, 26 (1), 135–151. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Cao, Y.; Okaze, T. Comparison of Hexahedral, Tetrahedral and Polyhedral Cells for Reproducing the Wind Field around an Isolated Building by LES. Building and Environment 2021, 195, 107717. [CrossRef]

- Das, A. K.; Acharyya, K.; Sarma, S.; Saha, U. K. Hybrid Double-Divergent Nozzle as a Novel Alternative for Future Rocket Engines. Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets 2022, 59 (3), 761–772. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Nayfeh, A. H. Detailed Characteristics of the Resonating and Non-Resonating Flows Past a Moving Cylinder. In 49th AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference; AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics]: Schaumburg, Illinois, USA, 2008; p AIAA 2008-2311. [CrossRef]

- Lyra, P. R. M.; Almeida, R. C. A Preliminary Study on the Performance of Stabilized Finite Element CFD Methods on Triangular, Quadrilateral and Mixed Unstructured Meshes. Communications in Numerical Methods in Engineering 2002, 18 (1), 53–61. [CrossRef]

- Smith, R. A PDE-Based Mesh Update Method for Moving and Deforming High Reynolds Number Meshes. In 49th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting including the New Horizons Forum and Aerospace Exposition; AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics]: Orlando, Florida, USA, 2011; p AIAA 2011-472. [CrossRef]

- Koo, J.; Kleinstreuer, C. A New Thermal Conductivity Model for Nanofluids. J Nanopart Res 2004, 6 (6), 577–588. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Nayfeh, A. H. Simulation, Analysis, and Explanation of the Lift Suppression and Break of 2:1 Force Coupling Due to in-Line Structural Vibration. In 49th AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference; AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics]: Schaumburg, Illinois, USA, 2008; p AIAA 2008-2309. [CrossRef]

- Karataev, R. N. Modelling of Gas Streams Taking Account of Viscosity. Meas Tech 2005, 48 (2), 171–174. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Thermo Physical Chemical Properties of Fluids Using the Free NIST Chemistry WebBook Database. Fluid Mechanics Research International Journal 2017, 1 (1). [CrossRef]

- Hardianto, T.; Sakamoto, N.; Harada, N. Three-Dimensional Flow Analysis in a Faraday-Type MHD Generator. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2008, 44 (4), 1116–1123. [CrossRef]

- SciPy. scipy.optimize.curve_fit. https://docs.scipy.org/doc/scipy/reference/generated/scipy.optimize.curve_fit.html (accessed 2025-02-15).

- SciPy. Optimization and root finding (scipy.optimize) — SciPy v1.15.1 Manual. https://docs.scipy.org/doc/scipy/reference/optimize.html#module-scipy.optimize (accessed 2025-02-15).

- Himawan, M.; Sadrawi, M. Development of Long QT Syndrome Detection Using SciPy. Indonesian Journal of Life Sciences 2023, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Huckaby, E. D. Nongray EWB and WSGG Radiation Modeling in Oxy-Fuel Environments. In Computational Simulations and Applications; Zhu, J., Ed.; IntechOpen, 2011; pp 493–512. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Huckaby, E. D. New Weighted Sum of Gray Gases (WSGG) Models for Radiation Calculation in Carbon Capture Simulations: Evaluation and Different Implementation Techniques. In 7th U.S. National Technical Meeting of the Combustion Institute; Atlanta, Georgia, USA, 2011; Vol. 4, pp 2483–2496. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Jul, W. A. M. H. R.; Al Jabri, A. M. K.; Al-ghaithi, H. A. M. A. Construction of a Small-Scale Vacuum Generation System and Using It as an Educational Device to Demonstrate Features of the Vacuum. International Journal of Contemporary Education 2018, 1 (2), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Dataset of Total Emissivity for CO2, H2O, and H2O-CO2 Mixtures; over a Temperature Range of 300-2900 K and a Pressure-Pathlength Range of 0.01-50 Atm.m. Data in Brief 2025, 59, 111428. [CrossRef]

- Foust Iii, H. C. Thermodynamics, Gas Dynamics, and Combustion; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. Problems and Solutions in Thermal Engineering: With Multiple-Choice Type Questions; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Coupled Differential-Algebraic Equations Framework for Modeling Six-Degree-of-Freedom Flight Dynamics of Asymmetric Fixed-Wing Aircraft. International Journal of Applied and Advanced Sciences 2025, 12 (1), 30–51. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. A Flight-Mechanics Solver for Aircraft Inverse Simulations and Application to 3D Mirage-III Maneuver. Global Journal of Control Engineering and Technology 2015, 1, 14–26. [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wen, C.; Yang, Y. Performance of Supercritical Carbon Dioxide (sCO2) Centrifugal Compressors in the Brayton Cycle Considering Non-Equilibrium Condensation and Exergy Efficiency. Energy Conversion and Management 2024, 299, 117849. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. InvSim Algorithm for Pre-Computing Airplane Flight Controls in Limited-Range Autonomous Missions, and Demonstration via Double-Roll Maneuver of Mirage III Fighters. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 23382. [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, A. T. Fluid Flow in Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Systems. In Introduction to Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Systems: Theory and Applications; Kirkpatrick, A. T., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; pp 65–89. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Huckaby, E. D. Simulation of a Swirling Gas-Particle Flow Using Different k-Epsilon Models and Particle-Parcel Relationships. Engineering Letters 2010, 18 (1).

- Darbandi, M.; Zakyani, M.; Schneider, G. Evaluation of Different K-Omega and k-Epsilon Turbulence Models in a New Curvilinear Formulation. In 17th AIAA Computational Fluid Dynamics Conference; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2005; p AIAA 2005-5101. [CrossRef]

- Kurganov, A.; Petrova, G. Central Schemes and Contact Discontinuities. ESAIM: Mathematical Modelling and Numerical Analysis 2000, 34 (6), 1259–1275. [CrossRef]

- Kurganov, A.; Tadmor, E. New High-Resolution Central Schemes for Nonlinear Conservation Laws and Convection–Diffusion Equations. Journal of Computational Physics 2000, 160 (1), 241–282. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. The Sod Gasdynamics Problem as a Tool for Benchmarking Face Flux Construction in the Finite Volume Method. Scientific African 2020, 10, e00573. [CrossRef]

- Kurganov, A.; Tadmor, E. New High-Resolution Semi-Discrete Central Schemes for Hamilton–Jacobi Equations. Journal of Computational Physics 2000, 160 (2), 720–742. [CrossRef]

- Sparrow, E. M.; Gregg, J. L. Heat Transfer From a Rotating Disk to Fluids of Any Prandtl Number. Journal of Heat Transfer 1959, 81 (3), 249–251. [CrossRef]

- Li, D. Turbulent Prandtl Number in the Atmospheric Boundary Layer - Where Are We Now? Atmospheric Research 2019, 216, 86–105. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Validating a Model for Bluff-Body Burners Using the HM1 Turbulent Nonpremixed Flame. Journal of Advanced Thermal Science Research 2016, 3 (1), 12–23. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Huckaby, E. D. A Comparative Study of Eight Finite-Rate Chemistry Kinetics for CO/H2 Combustion. Engineering Applications of Computational Fluid Mechanics 2010, 4 (3), 331–356. [CrossRef]

- Oberkampf, W. L.; Trucano, T. G. Verification and Validation in Computational Fluid Dynamics. Progress in Aerospace Sciences 2002, 38 (3), 209–272. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Benchmarks for the Omani Higher Education Students-Faculty Ratio (SFR) Based on World Bank Data, QS Rankings, and THE Rankings. Cogent Education 2024, 11 (1), 2317117. [CrossRef]

- Wüthrich, B. Simulation and Validation of Compressible Flow in Nozzle Geometries and Validation of OpenFOAM for This Application. Master Thesis, Institute of Fluid Dynamics, ETH [Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich], Zürich, Switzerland, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Ishikwa, M.; Yuhara, M.; Fujino, T. Three-Dimensional Computation of Magnetohydrodynamics in a Weakly Ionized Plasma with Strong MHD Interaction. Journal of Materials Processing Technology 2007, 181 (1–3), 254–259. [CrossRef]

- Ayeleso, A. O.; Kahn, M. T. E.; Raji, A. K. Computational Fluid Domain Simulation of MHD Flow of an Ionised Gas inside a Rectangular Duct (August 2016). In 2016 International Conference on the Industrial and Commercial Use of Energy (ICUE); 2016; pp 84–91.

- Swallom, D. W.; Goldfarb, V. M.; Gibbs, J. S.; Sadovnik, I.; Zeigarnik, V. A.; Kuzmin, R. K.; Aitov, N. L.; Okunev, V. I.; Novikov, V. A.; Rickman, V. J.; Blokh, A. G.; Pisakin, A. V.; Egorushkin, P. N.; Tkachenko, B. G.; Babakov, J. P.; Olson, A. M.; Anderson, R. E.; Fedun, M. A.; Hill, G. R. Results from the Pamir-3U Pulsed Portable MHD Power System Program. In 12th International Conference on MHD Electrical Power Generation; Yokohama, Japan, 1996; Vol. 1, pp 186–195.

- Velikhov, E. P.; Pismenny, V. D.; Matveenko, O. G.; Panchenko, V. P.; Yakushev, A. A.; Pisakin, A. V.; Blokh, A. G.; Tkachenko, B. G.; Sergienko, N. M.; Zhukov, B. B.; Zhegrov, E. F.; Babakov, Yu. P.; Polyakov, V. A.; Glukhikh, V. A.; Manukyan, G. Sh.; Krylov, V. A.; Vesnin, V. A.; Parkhomenko, V. A.; Sukharev, E. M.; Malashko, Ya. I. Pulsed MHD Power System “Sakhalin” - The World Largest Solid Propellant Fueled MHD Generator of 500MWe Electric Power Output. In 13th International Conference on MHD Electrical Power Generation and High Temperature Technologies; Beijing, China, 1999; Vol. 2, pp 387–398.

- Panchenko, V. P. Preliminary Analysis of the “Sakhalin” World Largest Pulsed MHD Generator. In 33rd Plasmadynamics and Lasers Conference; AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics]: Maui, Hawaii, USA, 2002; p AIAA-2002-2147. [CrossRef]

- Makinde, O. D.; Sandeep, N.; Ajayi, T. M.; Animasaun, I. L. Numerical Exploration of Heat Transfer and Lorentz Force Effects on the Flow of MHD Casson Fluid over an Upper Horizontal Surface of a Thermally Stratified Melting Surface of a Paraboloid of Revolution. International Journal of Nonlinear Sciences and Numerical Simulation 2018, 19 (2), 93–106. [CrossRef]

- Khrapak, S. A.; Khrapak, A. G. On the Conductivity of Moderately Non-Ideal Completely Ionized Plasma. Results in Physics 2020, 17, 103163. [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, B. M. Transport Processes in Gas Discharge Plasma. In Theory of Gas Discharge Plasma; Smirnov, B. M., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; pp 151–196. [CrossRef]

- AML, [Ames Aeronautical Laboratory]. Equations, Tables, and Charts for Compressible Flow; Technical Report NACA-TR-1135; NACA [United States National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics]: Moffett Field, California, USA, 1953; pp 612–681. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/19930091059/downloads/19930091059.pdf (accessed 2025-02-17).

- Moroz, L.; Burlaka, M.; Frolov, B.; Dyzenko, T. Supersonic Convergent-Divergent Vaned Nozzles Design Algorithm and Respective Discharge Coefficient Model; American Society of Mechanical Engineers Digital Collection, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Puzach, S. V. Effect of Supersonic Diffuser Geometry on Operation Conditions. Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science 1992, 5 (1), 124–128. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Subcritical and Supercritical Rankine Steam Cycles, under Elevated Temperatures up to 900°C and Absolute Pressures up to 400 Bara. Advances in Mechanical Engineering 2024, 16 (1), 16878132231221065. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Condenser Pressure Influence on Ideal Steam Rankine Power Vapor Cycle Using the Python Extension Package Cantera for Thermodynamics. Engineering, Technology & Applied Science Research 2024, 14 (3), 14069–14078. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Huckaby, E. D. Effects of Turbulence Modeling and Parcel Approach on Dispersed Two-Phase Swirling Flow. In World Congress on Engineering and Computer Science 2009 (WCECS 2009); IAENG [International Association of Engineers]: San Francisco, California, USA, 2009; Vol. II, pp 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Yang, F.; Wu, K.; Ma, Y.; Peng, C.; Liu, T.; Wang, L.-P. Estimation of the Dissipation Rate of Turbulent Kinetic Energy: A Review. Chemical Engineering Science 2021, 229, 116133. [CrossRef]

- Apostolidis, A.; Laval, J. P.; Vassilicos, J. C. Scalings of Turbulence Dissipation in Space and Time for Turbulent Channel Flow. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2022, 946, A41. [CrossRef]

| Power System (Ordered by Power) | Pamir-0-KT | Pamir-1 | Pricaspiy | Pamir 3U | Soyuz | Ural | Khybiny | Sakhalin |

| Maximum electric power demonstrated (with an unmatched load), MW | 0.1 | 20 | 20 | 30 | 31 | 40 | 120 | 500 |

| Maximum electric power demonstrated (with a matched load), MW | - | 10 | 10 | 15 | 16 | 30 | 60 | 400 |

| Mobility | - | In containers | Mobile on a track | In containers | Mobile on a trailer | - | In containers | In containers |

| Number of MHD channels | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Length of MHD channel(s), m | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.8 | - | 1.17 | 4.5 |

| Operating duration for the load (duration of the pulse), s | Up to 3.6 | 3-7 | 3-7 | 2.5-10 | Up to 10 | 6 | 7-10 | Up to 7 |

| Minimum pause between two runs, h | - | 12 | 12 | - | 12 | - | 12 | 24 |

| Approximate maximum possible mass flow rate of working fluid (plasma), kg/s | 2 | 50 | 50 | 24 | 40 | 100 | 200 | 1,000 |

| Overall mass of the power system, tonne | - | 8 | 12 | 18 | 25 | 16 | 34 | 50 |

| Overall dimensions of the power system, m | - | 4 × 1.5 × 2 | 4 × 1.5 × 2 | - | 7 × 2 × 2 | - | 8 × 7 × 1.5 | 13.5 × 3.7 × 2.7 |

| Quantity | Unit | Expression or Value | Remarks |

| Specific heat capacity at constant pressure, | J/(kg.K) |

|

|

| Magnetic-field flux density magnitude, | T (tesla) |

|

|

| Hall parameter, | - |

|

|

| Scalar electric conductivity, | S/m (siemens per meter) |

|

|

| Cathode voltage, | V (volt) | 2,550 |

|

| Plasma molecular weight, | kg/kmol | 22.905 |

|

| Plasma specific gas constant, | J/(kg.K) | 362.978 | |

| Inlet temperature, | K (kelvin) | 2,750 |

|

| Inlet pressure, | bar | 3.28 |

|

| Inlet axial velocity, | m/s | 2,050 |

|

| Inlet specific heat capacity at constant pressure, | J/(kg.K) | 2,357.426 | |

| Inlet specific heat capacity at constant volume, | J/(kg.K) | 1,994.448 |

|

| Inlet specific heat ratio, | - | 1.1820 |

|

| Inlet speed of sound, | m/s | 999.5 |

|

| Inlet Mach number, | - | 2.05 |

|

| Inlet Plasma density, | kg/m3 | 0.32859 | |

| Inlet cross-section area, | m2 | 0.9 |

|

| Mass flow rate, | kg/s | 606.2 |

|

| Outlet cross-section area, | m2 | 1.6 |

|

| Condition | Adopted Setting |

| Turbulence model | Standard k-epsilon 247,248,247 |

| Flow solver | Density-based, nearly explicit |

| Upwind scheme | Kurganov central 249–252 |

| Prandtl number (Pr) | 0.72 253,254 |

| Time-step | 5 × 10–6 s (5 μs) |

| Completed time steps | 8000 |

| Simulated time | 0.04 s |

| Quantity | Our Value | Benchmarking Value | Remarks |

| Electric power output | 488.1 MW | 476 MW 261 |

|

| Electric current from electrodes | 191.4 kA | 200 kA 263 |

|

| Plasma speed at channel exit | 1,156 m/s | 1,306 m/s 264 |

|

| Quantity | Nominal Resolution | Finer Resolution |

| Number of cells | 376,380 | 1,235,250 |

| Time step | 5 × 10–6 s | 2.5 × 10–6 s |

| Electric power output | 488.1 MW | 480.3 MW |

| Volume-average pressure | 3.128 bar | 3.011 bar |

| Volume-average Lorentz force density vector | [–89.12, 28.83, 0] kN/m3 | [–85.86, 28.75, 0] kN/m3 |

| Volume-average electric-current density vector | [1.462, –4.517, 0] A/cm2 | [1.457, –4.351, 0] A/cm2 |

| Quantity | Outlet Value | Inlet Value |

| Temperature (K) | 2,738.4 | 2,750 |

| Pressure (bar) | 3.294 | 3.28 |

| Axial velocity (m/s) | 1,156 | 2,050 |

| Mach number ( - ) | 1.161 | 2.051 |

| Electric conductivity (S/m) | 48.4 | 50 |

| Hall parameter ( - ) | 0.2555 | 0.2715 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).