1. Introduction

Research on historical energy transitions has emphasized the central role of energy services—the benefits derived from energy use rather than the raw energy inputs themselves—as key drivers of change. Energy services shape the pace of technological adoption, the learning curve, conversion efficiency, and ultimately the cost of emerging energy technologies (Fouquet, 2010; Grubler, 2012). In this view, the transition to a hydrocarbon-based society is best understood not as a single process, but as a series of overlapping transitions in lighting, power, heating, and transportation.

However, focusing only on energy services leaves aside certain energy-intensive industries where “service” is not the primary driver. A notable example is the iron industry, where production itself constitutes the service. In such cases, the main forces behind energy transitions were not services, but new products that met shifting societal needs.

In the iron industry the new products that spurred the demand for more energy were the production of wrought iron, mostly in rolled form, for the supply of structural materials, railroad infrastructure and equipment. As explained further ahead, this transformation entailed product changes in quantity and quality and additionally regime shifts in the industry. Briefly, innovations in iron products fueled higher coal consumption.

To discover the connection between coal consumption and expanded material (iron and steel) usage, we look specifically at the United States nineteenth century iron industry. Important though America’s iron and steel became to the world economy, its development pattern was in any case atypical. Borrowing the concept of exceptionalism from U.S. political and cultural studies, we use it here to highlight the distinctiveness of America’s industrial trajectory, compared to the European path (See Ayres,1989; Warde, 2013).

Two things stand out: First, while European nations generally moved from wood to a single fossil fuel—bituminous coal—the U.S. experienced two separate transitions: first to anthracite coal, then to bituminous coal. This meant dual starting points, parallel technological pathways, and a geographical dispersal of resources. Second, exceptionalism entails another meaning related to the specificities of the New World economy: during the nineteenth century the United States was a nation with a moving frontier, driven by the Westward settlement of new settlers. As Turner ([1893] 1920, 3) remarked: “The American frontier is sharply distinguished from the European frontier — a fortified boundary line running through dense populations. The most significant thing about the American frontier is, that it lies at the hither edge of free land “, creating cycles of settlement and resource usage. This westward expansion stimulated iron and steel consumption while imposing new demands for scale that far exceeded those of European producers. For this reason, American industrialization is largely influenced by cycles of expansion, slowdown and stoppage in West frontier advancement. Given the extension of the territory from the Atlantic to the Pacific, the iron industry had to cope with giant scale economies.

Taken together, these factors show that the U.S. did not undergo a single, linear energy transition. Instead, it experienced multiple, overlapping transitions—one country, many regimes—defined by shifting relationships between iron production and energy use.

3. The Rust Belt History

3.1. Eastern Pennsylvania - the Hybrid Frontier

The modern U.S. coal iron industry first emerged in the rugged mountainous country of eastern Pennsylvania. Throughout the first half of the nineteenth-century, these innermost unpopulated territories began attracting labour, capital and technology to work the coal fields in the mountains and manufacturing in the cities and valleys. Stretching fifty miles long and five miles wide Pennsylvania’s anthracite coalfields comprised three distinct areas of production: Schuylkill, Lehigh and Wyoming. To reach customers required getting the bulky coal commodity to urban centers (especially Philadelphia, New Jersey and New York) located 100 to 130 miles away through the Tidewater region.

Early attempts to transport goods by horse-drawn wagons or by navigating the treacherous rivers proved unsuccessful. According to contemporary accounts, the energy shortage triggered by the War of 1812 and the subsequent blockade of British and Virginia bituminous coal supplies to major Mid-Atlantic cities spurred entrepreneurial efforts to improve the navigation along the Schuylkill, Lehigh, Delaware, and Raritan rivers. The goal was to make anthracite coal readily available to the energy-starved regions of Philadelphia and New York. However, historical data on firewood prices indicates that this crisis nevertheless persisted with wood prices remaining elevated in major cities into the 1820s (Bezanson,1936, p.381).

Between 1818 and 1832, anthracite transport waterways were completed and coal was shipped to the eastern seaboard. Private merchants and firms combined to establish the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company, the Schuylkill Navigation Company, and the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company and successfully raised the necessary capital to build canals and improve navigation. The catalogue of technical solutions was both vast and innovative given the overall scarcity of engineering expertise at that time. Extensive construction works strove to create smooth means of water transport combining the partial usage of the rivers with the building of artificial canals. Furthermore, the water flow needed regulating by building a succession of dams to form slack water pools that ensured adequate water depth for shipping to pass. These passages were thus regulated by locks and canals to bypass dams, falls and rapids. Above all, the rush to improve continued long after the first inaugurations: subsequently installing gravity railroads to get the coal from the mines to waterways; completing a towpath along the extent of the canals; deepening them to allow for the circulation of larger boats; replacing the initial, capital investment saving, descending-only navigation system with a full canal system for both descending and ascending navigation as well as upgrading the dockage facilities (Jones,1914, Jones, 2014).

All of these transport improvements brought about clear impacts with prices falling: canals were able to deliver coal to Philadelphia, in contrast to the $20/ton wagon transport price, at price of $5.50 per ton in 1830; with the same amount bought for $4.75 eight years later before an all-time low price was finally reached in 1844 at $3.20/ton (Taylor, 1848, p.125; Munsell,1881). Competition likewise kept prices low as several private companies competed for the same market all the while public enterprises grouped in the Pennsylvania State Works opened up their own anthracite canals with very low tolls to counterbalance the power of private business (Adams, 2004, p.112-117).

Despite such supply side dynamics, with canals fostering new sources of demand for coal, other factors also came into play: consumers initially displayed a bias against anthracite, somehow reflected in the expression “stone coal”. Unlike bituminous coal or charcoal, anthracite is almost pure carbon (generally above 92%), thus a dense material with little volatile matter. Consequently, anthracite is difficult to ignite and attempts to start fires in open fireplaces often end unsuccessfully. Hence, it was necessary to prove it worked. This task was undertaken by promotional campaigns and bolstered by entrepreneurs and scientific societies. Blacksmiths consuming large amounts of energy in the value of their products also became powerful allies. Over the years, low prices and the security of supply triggered a cascade of innovations with the most important including the multiple inventions for stoves able to heat homes with anthracite. Particularly between 1830 and 1840, the stove industry made headway in cities including Reading, Philadelphia and New York and turning residential demand into the largest market for coal and liberating the main seaport cities from energy constraints. Jones (2014, p.62) estimates that at least nine out of ten homes in these cities were heated mainly by anthracite coal at the outbreak of the Civil War. Thanks to this new material resource, urban population growth could henceforth proceed apace (Harris, 2008; Jones, 2011). Anthracite shipments from Eastern Pennsylvania impacted even on remote areas such as Boston. Above all, the new energy flows changed Philadelphia’s metabolism. Supplementing the residential market for coal, the Quaker city attracted several energy-intensive industries, namely glass, distilling, sugar refining, instrument production and hardware manufacturing. Energy flows delivered by canal transformed this region into the industrial commonwealth of the USA. Summing up this transition from a colonial state into a newly industrialized state, Stevens (1955, p. 56) acknowledged how, in the mid-nineteenth century, “almost everything that was being manufactured in the United States was made in some form somewhere in Pennsylvania”.

Table 1 sets out a statistical portrayal of the pace of events with anthracite mining reaching over one million tons in as early as 1837. To appropriately gauge these supply side dynamics, we need to explain how the early historical coal statistics only report the records of shipments carried on canals and, somewhat later, on railroads. The mining statistics are otherwise absent. To address this gap, we adopted Vera Eliasberg's (1966) suggestion about distinguishing between coal shipped and coal produced by increasing the recorded shipment figures by an additional 20% (

Table 1, Total Production column). However, this nevertheless represents an utterly conservative estimate. At least 10%-12% of all coal mined was consumed on site, powering the steam engines pumping water, cooking meals for colliers and heating their homes; (Jones,1914, p. 58), while another at least 10% fueled the corporate railways and ships transporting coal to the loading ports.

The comparison between the amounts shipped primarily for home heating and the deliveries supplied to blast furnaces (

Table 1 column Consumption Blast Furnaces) identifies the iron industry’s lack of significance to overall coal demand (4-10% ). In other words, during the early stages of Pennsylvania’s energy transition, it was the growth and maturity of the residential coal market, brought about by lower transport costs, that enabled the conditions for the development of the iron industry. The causal relationship flows from coal to iron and not the other way around. In entrepreneurial terms, this assumption is further confirmed by mining and distribution companies figuring among the leading investors in anthracite blast furnaces (Bartholomew,1988). With the expansion of canals and the spread of anthracite usage, a world of business opportunities was there to be seized.

And so it continued: from 1836 onwards, several businessmen and ironmasters independently attempted to smelt iron ores with anthracite. Despite the many claims to this discovery, the technical blueprint for the region was set down by the Welshman David Thomas on 4 July, 1840, in a blast furnace near Allentown on the Lehigh River. To compensate for anthracite’s high density, ignition problems and clogging risks, Thomas’ furnace was larger and taller than the traditional wood-based charcoal furnaces. He also incorporated the recently invented hot-blast stove (James Neilson’s 1828 British patent), which preheated air and blew it into the furnace. By this means, the British technology and machinery patented by James Neilson, was transplanted into America (Yates, 1974).

Widely recognized as one of the key nineteenth-century ironmaking technological innovations, the hot blast enhanced the overall efficiency by two means: on the one hand, it halved the amount of coal spent per ton of pig iron produced, thus cutting costs; on the other hand, it raised the weekly production volume of each furnace. The rapid growth of Pennsylvania pig iron production correlates with the claim that the industry both benefited from hot blast technology and was competitive from the outset. Nevertheless, doubts then remained as to whether American anthracite furnaces would be able to pursue the hot blast efficiency path over the long haul (Belford, 2013, p. 34).

To conclude, the beginning of coal-based blast furnaces did not mean the arrival of any fossil fuel civilization but rather introduced a hybrid economy still moored in the old agrarian society. First and foremost, blast furnaces provided the commodities for the settler’s agrarian regime. They made stoves, grates, pots, and skillets, shovels, axles and forks, by running the hot metal directly from the crucible into molds to produce finished cast iron. Such cast iron could be brittle but was adapted to consumer needs and enjoyed stable demand in rural milieus. About 11-25% of the molten metal was directed to castings (Childs, 1947, p.17; Temin, 1964, p. 29). The remaining was poured into cavities to make pigs. Molten metal in pig form was not a final commodity but an intermediate good, often sold in bars to the traditional charcoal powered forges and to blacksmiths. To enhance metal ductility and tensile resistance, the forges placed the pig iron in a refinery fire before beating it on an anvil with a hammer. These operations removed the excess carbon to produce a higher quality “wrought iron” that could withstand wearing, compressive strength, and abrasion. Therefore, this productive process was hybrid, partly coal-based in blast furnaces, partly wood-based in forges and bloomeries. This hybridization was also described by O’Connor and Cleveland (2014, 7975): “the early launch phase of [coal] ascendancy was clearly powered by the nation’s forests”. Obsolescent productive processes may therefore experience a last gasp. In Pennsylvania, modern coal technologies ended up extending both the market for traditional charcoal technologies and the demand for wood. The hybrid anthracite iron industry appealed to the agrarian-solar energy regime ingrained in forests and with high energy transportation costs. The industry's success was closely tied to its adaptation to the local environment, particularly in the South Atlantic, which was among the most densely populated regions in the early nineteenth century. Along with New England and the Middle Atlantic, Eastern Pennsylvania and the South Atlantic formed the core of early American settlement, dating back to the colonial era (Otterstrom,1997; 2002). In this context, the natural resource frontier intersected with the frontier of human settlement. Farmers and residents of nearby merchant cities generated sufficient demand to support and sustain the industry within its immediate surroundings.

3.1. Western Pennsylvania and Ohio – the Big Frontier

It was only in the 1850s that the iron industry took root in the known bituminous coal fields of western Pennsylvania, thereby moving the production frontier westwards. This region extended into the discontinuous seams running from Ohio into Alabama and from the western counties of Virginia into western Kentucky. Following this relocation, the US economy tapped a huge energy store that doubled the amount of energy available in the Eastern Pennsylvania anthracite coal fields. In the end, the high energy demanding society built up by American settlers was able to persist and endure through exploiting a new stream of non-renewable resources (Schurr, Netschert,1960). This added frontier comprised the stronghold of the traditional charcoal iron industry scattered along the Monongahela and Youghiogheny Rivers. When the old industry collapsed due to both the depletion of woodlands and intensified price competition from British iron imports, new opportunities emerged to fill the market void. The mineral bituminous economy replaced the renewable forest economy and often directly through reconverting existing charcoal furnaces to bituminous fuel. Hybridization gave way to creative destruction.

Thus, the adoption of new fuels by proprietors of long-established wood-based furnaces appears to represent the initial stage in the bituminous/coke iron diffusion process (Gordon, 1996, p.165-166; Swank, 1892, p.458). The statistical profile of this evolution is sharply depicted by geologist J. Peter Lesley in his historical survey of the iron industry. Observing the abandoning of traditional production, Lesley (1859, p.752) concludes: “the charcoal regions in western Pennsylvania and Ohio have been invaded … by the raw bituminous coal process”. The complementarity of wood-coal vanished.

Most of all, the changeover to the huge bituminous coal reserves occurred at a moment of imbalance in the productive cycle: henceforth, both pig iron and wrought iron resorted to the mineral fuel technology. The final stage in coal decarbonization was obtained not just by boiling molten metal in charcoal forges and hammering it but also by re-heating and stirring in puddling mills fueled by bituminous coal. America adopted the British reverberatory puddling furnace technology in which the heat was conveyed to the molten iron without direct contact between the fuel and the metal, thereby avoiding the hazards of incorporating any of chemical impurities present in fuels (especially phosphorus that embrittles wrought iron).

Iron making across the Western Pennsylvania-Ohio frontier entailed higher coal consumption as it became omnipresent throughout the entire production cycle, from smelting ore to refining iron bars, replacing the traditional wrought iron industry. Still furthermore, the final stages – refining into bars and rails acquired an overriding centrality in the overall business dynamics. The network of small forges with tiny wrought iron production and little capital investment was swept aside by large mills with overwhelming outputs imbued with fresh capital. Usually, coal fueled puddling mills fed several furnaces and soon began integrating rolling mills for finishing and shaping wrought iron: this technology required two grooved rolls driven either by waterpower or steam engines, facing towards each other to squeeze out the semi-solid iron form. Multiple passages through ever smaller rolls could transform iron bar into finished rails. The production of final goods for a vibrant market made investing in economies of scale attractive.

In broad terms, there was a threefold difference in the productive capacity of coal-based rolling mills rails (average productive capacity of 17,836 tons/year) and traditional mills, specialized in nails (6,963 tons/year), merchant iron (7,620 tons/year) and iron plate (6,320 tons/year) (Dunlap,1874).

The emergence of economies of scale in wrought iron partly derived from the availability of the capital necessary to respond to the large orders commissioned by railroad companies. Given the scale of railway operations and inventories, some wrought iron mills could transform themselves into reasonably big businesses through specializing in rail production. The surge in demand from railroad corporations reached its peak over the 1851-1856 period and later on in the 1880s. Furthermore, it is important to recall that the bulk of rail mileage was met by British imports (187,488 metric tons in 1856) rather than by American production (158,540 metric tons) (Lesley, 1866). It would take another three decades to complete the process of import substitution. In any case, the iron industry entered a new phase characterized by economies of scale and large bulk orders as pioneers crossed the Mississippi River and settled in the prairies of Iowa and the forests of Minnesota (Billington, Ridge, 2001; Bazzi, Fiszbein, and Gebresilasse,2020) . With the westward expansion of the American frontier, integrated national markets began to replace the earlier, more localized Atlantic regional markets. Once again, the movement of the settlement frontier drove the productive frontier further west.

In overall terms, this period marks the reversal in the previously observed coal/iron causality: from this point onwards, the expansion of iron production drives increased coal consumption. Achieving economies of scale in puddling and rolling mills required new coal resources, furthermore replacing part of the traditional wood-based wrought iron technology. Moreover, a constellation of innovations with the stamp of American ingenuity yielded a continuing improvement and leveraged productivity gains over time. To mention only the key examples: the installation of double puddling furnaces with enlarged hearths, allowing two puddlers to simultaneously work the furnace; the standardization of industrial processes through the production of “T rails”; the invention of the three-high mill by putting an extra roll on top of the grooved roll train, enabling the iron to be rolled both on its way forward and immediately on its way back (Davis, 1922, Gordon 1986, p.125-164 ). All of these innovations increased both the output of iron and coal consumption. Overall, a noteworthy push to achieve economies of scale came when rolling mills took the initiative to buy blast furnaces and integrate the complete business cycle. According to Peter Temin (1964, p.109-112), wrought iron producers with sufficient economies of scale sought to control their supply chains, ensuring a steady flow of pig iron and castings through interfirm transactions with their own blast furnaces. However, the economic rationale behind this integration remains somewhat perplexing as there were only limited technical complementarities and/or energy savings to be achieved. In truth, business integration might not have been the success story envisaged by Peter Temin. We would rather characterize this trend as integration but falling short of concentration. The author pinpoints how the largest iron firms as of 1860 were all integrated rail mills: the Montour Works in Danville and the Phoenix Works in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania; the Trenton Iron Works, New Jersey and the Cambria Iron Works in Johnstown, Pennsylvania. These firms certainly represent the leading industrial forerunners with outstanding achievements in new production techniques, more complex machinery and product innovation (Albright, 1988; Peterson, 1980; Hunter, 2005). However, just ten years later, only the last, the Cambria Iron Works in Johnstown, the only plant that consumed coke as a fuel, still held its place among the top-ranking firms (Dunlap, 1874).

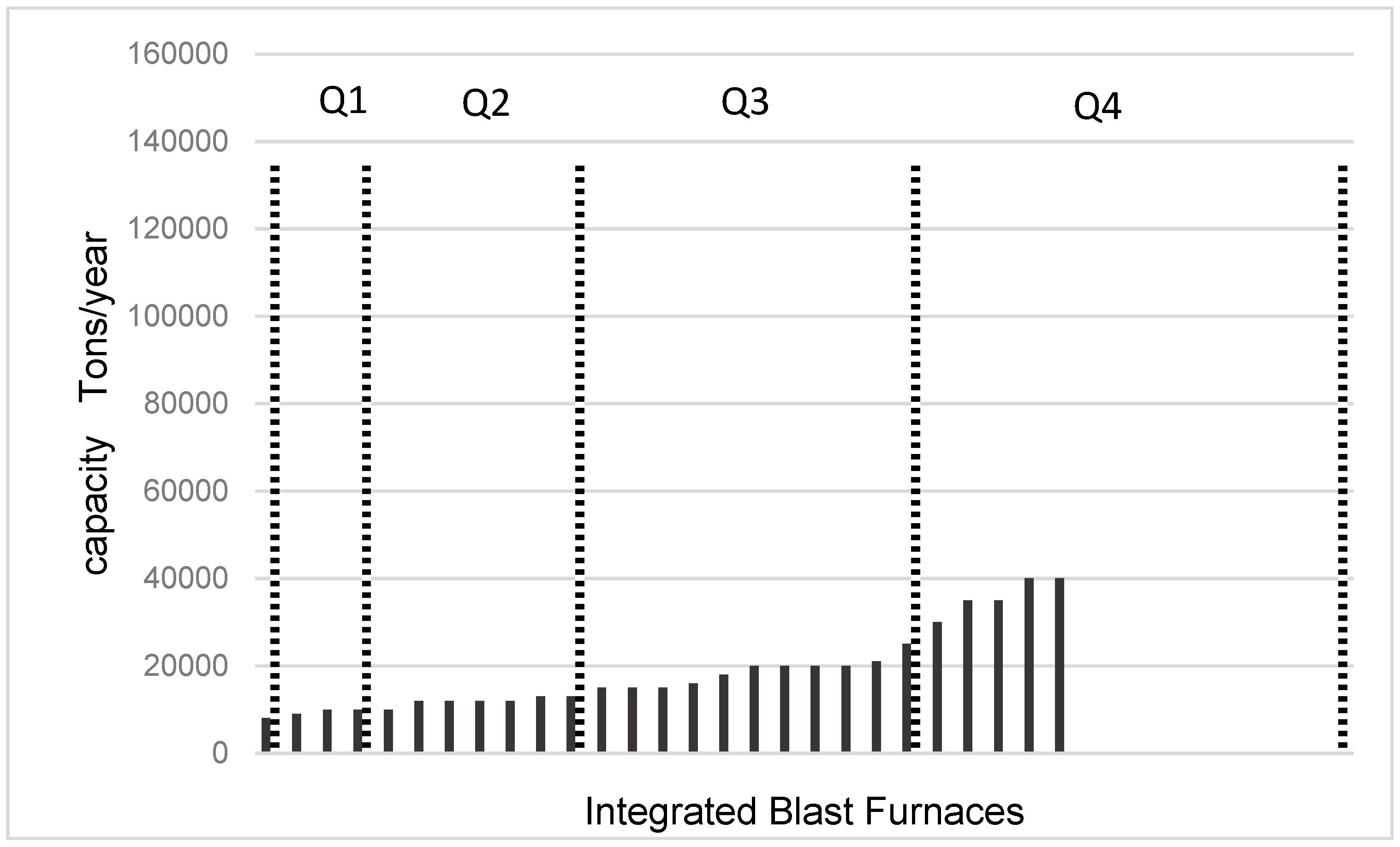

Graph 1 illustrates the concept of integration short of concentration by plotting the position of integrated blast furnaces among the capacity range of all working blast furnaces2. The vast majority of producers in these conditions are located below Q3, the upper quartile, reflecting how the uppermost integrated companies are not ranked in the top productive capacity but below 75% of the entire distribution of furnace capacity (below the third quartile). In other words, although they fared well, they did not become the mammoths of the iron industry.

Graph 1.

Quartile Distribution of Blast Furnaces with Integrated Puddling/Rolling Mills, 1873.

Graph 1.

Quartile Distribution of Blast Furnaces with Integrated Puddling/Rolling Mills, 1873.

Sources Dunlap, Thomas. Wiley's American iron trade manual of the leading iron industries of the United States, with a description of the iron ore regions, blast furnaces, rolling mills, Bessemer steel works. New York: J. Wiley and Son, 1874.

Irrespective of the alluring appeal of the large orders placed by railroad companies, there was a highly competitive market for basic pig iron sales. This was so competitive that even some blast furnaces that fed their own rolling mills with semifinished products, chose to sell the remaining pig iron output in the open market. Paradoxically, some integrated blast furnaces continued to behave like merchant furnaces – a curious epochal category applied to iron producers operating in decentralized business markets (Bennett, 1996, p.30-32).

Post-1864, another factor entered this equation and began swelling the tide: in Great Britain (Henry Bessemer) and in the USA (William Kelly), there arose a new process for making steel at high temperature by blowing air into a molten iron filled cauldron. In one fell swoop, steel producers popped up in Pennsylvania, Ohio and Illinois and replacing wrought iron in the production of rails, iron plate, iron sheets and barbed wire as well as cast iron in beams for building, bridges and subways and also in agricultural hardware (Misa,1995). Adjusting to this cheap and hardened metal, American industry took a notable turn: the final stages of the wrought iron industry then either specialized in new classes of goods or started working for Bessemer plants refining the shapes of steel products. A new era was on the horizon. Blast furnaces, on the other hand, renewed the high demand for pig iron needed by the Bessemer plants. As steel plants working with two converters could produce as much as 60,000 tons a year, steel imparted a tremendous impetus to blast furnaces. The extended pig iron market ensured owners could generate greater revenues from a single plant. Therefore, the second half of the nineteenth-century witnessed an unprecedented advance in economies of scale. To put it bluntly, the upscaling of blast furnaces attained distinctive plateaus in the American industrial landscape and dragging with it the demand for coal. Great fortunes were in the offing. In comparative terms, this trend was even more groundbreaking than the previous upscaling of rolling mills.

Responding to technological and scientific improvements in the blast furnace engineering developed in Cleveland, Middlesborough, Great Britain, American entrepreneurs then rapidly adopted taller and superheated furnaces and soon overtaking European thresholds in every respect. The British size became gigantic business on the other side of the Atlantic (Berck,1978). The long tradition of building exterior stone walls was shattered by the arrival of cast-iron shells and wrought iron bands supported by columns or mantles built upon the customary masonry arches. Owing to the light but reinforced structure of cast-iron columns and mantles, furnaces could withstand the weight of increasingly tall plants. The paramount height of 50-60 feet structures achieved by the leading furnaces in 1860 had grown to 75 feet twenty years later. Named cupola furnaces after their shape, these furnaces could take a larger burden of iron and limestone and yield increasing volumes of pig iron because they were blown by two, and then three and finally four regenerative hot blast stoves. The regenerative capacity meant the flow of escaping gases was reversed into heat stacked bricks that then conveyed the heat to incoming air. This procedure saved energy while the patented Cowper-Siemens stove adopted in America increased the blast temperature from the customary 600- 700 degrees to 1,200-1,300 degrees (Bennett, 1996,p. 81-83). Likewise, the blast of old type furnaces of around four pounds per square inch was now raised to a maximum of nine pounds per inch.

Pushing the technological conditions still further, in the 1880s, American pioneers introduced the techno-entrepreneurial vision of hard-driving: a method of increasing furnace outputs by driving the equipment faster and with greater loads. Despite some initial accidents and shutdowns for repairs, the results were soon forthcoming: whilst the best old charcoal and coke furnaces could reach a volume of 60-70 tons of pig iron a week, jumbo hard driving furnaces attained 1,000-1,200 metric tons per week (Swank, 1892, p.456-458; Bennett, 1996, p.177, 181). Bituminous coal converted into coke became the chosen fuel for these lucrative improvements. Still, despite the many successful entrepreneurial stories some businesses held reservations regarding the harmful impacts of large production yields on the hearth and walls of cupola furnaces as well as on the lifespan of the refractory lining. The generally prevailing feeling was that blast furnaces were on the verge of diseconomies of scale. The varying interpretations paved the way for distinctively different scientific-management strategies: in broad terms the Pittsburgh hard-driving model coexisted both with the Illinois-Chicago slow-driving outline and with the Alabama slower-driving standard (Woodward II, 1940; Bennett, 1996, pp.136-142; 172-178,185-186). Compared with former practices, there was an overall drop in the amount of fuel consumed per ton of pig iron delivered. However, the effects were not of a piece: differences in fuel savings varied from one location to another (Appendix 1: input technical coefficients).

In this competitive environment, firms were compelled to integrate backwards in order to secure steady supplies of iron ore, coke and coal. The extraordinary upscaling at the close of the nineteenth-century reinforced the linkages between iron furnaces, coke ovens and coal mines. Given the scale of industrial change, consolidation rather than integration became the business byword. Ultimately, the attempt to obtain secure inputs of raw materials for blast furnaces and steel plants opened the door to the formation of industrial empires through vertical and horizontal consolidation. Among the most prominent cases are the agreement signed in December 1881 by Andrew Carnegie, then owner of several blast furnaces and the Bessemer steel works with their assets thereby combined into the giant Carnegie Steel Company and, on the other hand, Henry Clay Frick, the largest U.S. coke producer controlling over 1,020 coke ovens located at nine different plants served by several coal fields (Warren, 2001, p.61-62; Berglund,1907, p.277-278). Carnegie would later go on to control ample supplies of ores in the Great Lakes region. Likewise, another consolidation, in May 1889, brought the management of five large rolling mills, blast furnaces and steel plants under the joint control of the Illinois Steel Company. Collectively, the five industrial companies making up the new Chicago-based empire owned 4,500 acres of coal land and 1,150 coke ovens. In partnership with the Elgin, Joliet, and Eastern Railroad Company, they later formed the Federal Steel Company (Cope,1890, p.24-28). The association of iron/steel and coal/coke and ore interests formed part of a race to the bottom for the control for natural resources. Basic raw materials and semifinished products became concentrated in just a few hands. Unsurprisingly, the economies of scale that ravaged pig iron and Bessemer steel production snowballed into the formation of consolidated empires. Fuels and metals were now two sides of the same coin. The beginning of a cycle of new products based on better quality rolled iron pushed the whole industry to higher heights, dragging along coal demand.

The foregoing discussion portrays how the dislocation of the iron frontier to Western Pennsylvania and Ohio enhanced the role of the iron industry in driving coal demand. This process unfolded over two stages: firstly, in the 1850s, with the upscaling of wrought iron production in puddling and rolling mills; secondly, in the 1880s, with the upscaling of blast furnaces. Managerial and technological innovations further extended the demand for bituminous coal with its quality and vast reserves constituting the bedrock of the successful American industry. In fact, from a certain point of view, it was the excellence of the natural resources, the outstanding quality of coke made with bituminous coal (0.821% sulphur) from the Connellsville region, 40 miles southeast of Pittsburgh, that pushed demand for fuel still higher (Platt, Pearse, 1876; Warren, 2001,p. 21-22). This “big” frontier reversed the earlier coal→iron causality turning it into an iron→coal connection.

3.4. Great Lakes – the Blurred Frontier

The shift in the iron frontier in a northeast-central direction towards the Great Lakes represented a displacement similar to the colonization by American settlers. The 1845 opening of the first ore mine took place amidst a vast wilderness covered with glacial drift, where farmers had to cope with land exposed to the natural adversities of sand, clay and boulders. Whilst the indigenous populations, the Anishinaabe nations, were being dispossessed of their lands, an ore rush flooded the region with people and capital resulting in mining centers and large cities, mostly built around modernized shipping ports (Duluth – Superior, Two Harbors, Ashland, Marquette and Escanaba). A dense railroad network, operated by competing companies, underpinned the connections between the Great Lakes and the entire American territory. Owing to the efficiency of the transportation system, the Great Lakes became a blurred frontier with its lands yielding good iron ore to feed distant industrial clusters in Ohio and Pennsylvania. On top of that, perfect Bessemer grade ore, available at a low cost from the Michigan and Minnesota mines also supplied the steel industry. The overall impact was so large that 35,000,000 tons of ore were shipped between 1880 and 1889 before rising to 104,000,000 tons in the next decade (Mussey, 1968, p.42). Altogether, these shipments overtook production from the traditional ore regions of New York, New Jersey and Ohio. The establishment of the Hull-Rust Mine in Minnesota, one of the largest open-pit mines in the world, provides a clear indication of the expansive entrepreneurial vision then prevailing.

The speed and success of these mining operations stirred the golden dream of building a fresh manufacturing district in the Great Lakes. Nonetheless, the installation of iron mills in the vicinity of mines proved unrewarding. Indeed, in the early twentieth century the scenery was desolate with many contemporary observers believing the region was doomed to turning into a string of ghost towns (McNeill and Vrtis, 2017, p.200).

However, extending beyond the strictly mining regions to consider the Great Lakes coast at large, a rather different scenario surfaces: steel and iron manufactures thrived along the shores of Lake Michigan, Lake Erie and Lake Ontario: Cleveland, Chicago-Gary, Buffalo, Tonawanda, Milwaukee County and northern Indiana all became key industrial centers. Benefiting from their proximity to the iron ore mines along with a strategic position in the railroad network, these cities pivoted the iron industry towards northeast-central supremacy: in a sign of the times, local pig iron production in 1907 supplanted the volume of Pennsylvania, the Atlantic Coast, or Alabama districts (Miller, 1914,p. 907).

The Great Lakes iron deposits occur in six major ranges near the western and southern shores in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. The chronological order of their discovery prevailed in the entire exploration as the largest and best deposits, the Mesabi Range in north-east Minnesota, were the last to be exploited. With the opening of high grade ore pits in this region, in around 1890-1892, the economy and population of the Great Lakes experienced a second revival. Firstly, unlike other deposits, the Mesabi range was a labor-saving field with most of the deposits at a depth of not more than 200 feet making open-pit mining with steam shovels feasible. Likewise, the ore was loaded directly onto the railroad car in the mine. These low production costs aligned with premium quality: Mesabi ores contained few chemical impurities (phosphorus, sulfur, manganese) aiding the work of iron masters. As regards the metallic iron percentage, the figures often mounted to 60-70% of metallic iron, compared to the average of 54% (New York iron ores) and 53.7% (New Jersey iron ores) (Leith,1903, p.214-226). To put it simply, Mesabi ores turbocharged the iron industry economy. . The timing of this exploration runs against the neoclassical theory of natural resources whose basic assumptions are that low-cost deposits are the first to be worked (Solow, 1974 p.4-5). On the contrary, In the USA the best iron ores appeared at mature stages of industrial development. Such fortuitous course of action provided an additional productivity spurt when most technological achievements had already been consolidated.

In effect, Robert Allen (1977, p.631) ascribes the spurt of productivity growth that improved USA iron and steel production at the close of the nineteenth-century to the energy savings enabled by recourse to Great Lakes ores: “with the substitution of Lake Superior ores for eastern ores, the attainable level of fuel economy rose to the European level and productivity grew rapidly”. This hypothesis is tested against alternative explanations, specifically that the core factor driving the competitiveness of the iron industry stemmed from the adoption of management practices and technologies based on economies of scale and speed. Resorting to regression analysis, the author concludes that hard driving methods generated little causal impact while consumption of Great Lakes ores and fuel economies were able to explain half of the total productivity growth (Allen, 1977, p.613-621).

Overhanging all of these considerations is the fact that high-grade ores contain low levels of chemical impurities. In the 17th century, ironmasters adopted the practice of adding limestone to iron furnaces after discovering that limestone flux, at high temperatures, could absorb any undesirable substances in the ore, thereby producing waste slag for discarding. This process helped reduce the chemical contamination of molten iron. Drawing on nineteenth-century metallurgical science, Robert Allen emphasizes how the chemical purity of Great Lakes ores required less limestone, less heat to melt the limestone, and, consequently, lower quantities of coal to feed the furnace. On top of that, less ore was needed in blast furnaces owing to this high metallic content. The Great Lakes Frontier ushered the industry into an age of fuel economy.

Likewise, other technical advantages opened multiple pathways to cutting costs: rich ores were able to speed up blast furnaces operations by fast-moving iron oxides converting into metallic iron, inducing a kind of spontaneous fast-driving; finally, as less flux and fuel were required, the labor costs of handling raw materials were also lowered.

As it turned out, the dynamics of the Western Pennsylvania and Ohio big frontier, characterized by iron upscaling innovations driving coal consumption, came to a halt. With the Great Lakes frontier, there was a complete inversion: now, iron innovations conserved coal, meaning the same amount of pig iron would be produced with less flux and less fuel. In sum, the USA coal-iron building block entered a stage of dematerialization. One might apparently conclude that the extractivist civilization was receding as the productive system required less inputs from the earth’s crust to satisfy ongoing industrial requirements. However, it remains to be seen whether the trend towards dematerialization represents a widespread phenomenon capable of shaping various technologies, production systems, and regions.

Thanks to Oren W. Weaver, the U.S. Commissioner of Labor, we are able to examine the scope of dematerialization through analysis of the input and output coefficients. Under a provision contained in the Act of Congress approved on June 13, 1888, the Commissioner of Labor undertook an inquiry into the prevailing conditions in the iron industry, encapsulating the cost of producing goods, the cost of living and the living conditions of the working class. Deploying a national team of surveyors, the inquiry undertook the “… delicate matter to ask manufacturers to give all the facts and figures relating to the cost of producing his goods” (Commissioner of Labor, 1891, p.5).

Table 2 presents a summary of this information gathered directly from the accountancy books of iron works.

Thus, there is a remarkable rapprochement between the historical production technologies. From this viewpoint, the survey corroborates contemporary observations about how Great Lakes ores penetrated markets across America. Previously distinct iron markets and their geographies became leveled out by the commonality of high-quality natural resources. Indeed, the context would seem to have benefited anthracite furnaces just as much as coke furnaces (and likely also the traditional charcoal furnaces). Limestone consumption, along with rock bottom fuel consumption per ton of pig iron, constitute the industrial benchmarks (for a comparative long haul outlook, see Appendix 1: input technical coefficients). In particular, as Robert Allen (1977) and Douglas Irwin (2003) noted, this dematerialization coincided with a cycle of productivity growth and a surge in America’s industrial exports.

Overall, how significant was this relief of pressure upon coal resources? We would here point out how the conclusions drawn so far are grounded on interpretations based on analyzing the physical quantities: production with lower material inputs is the very essence of the dematerialization concept. However, monetary factors may also impact on dematerialization given the physical savings commonly lead to cost reductions. As products become cheaper, demand for materials such as iron and its various applications tends to rise, which in turn boosts production and further fuels consumption. In simple terms, energy-saving innovations often spark increased energy consumption: less can result in more. This paradox, known as the Jevons Paradox, was first proposed by the British economist William Stanley Jevons in 1865. To illustrate his point, Jevons applied the example of blast furnaces: 'If the quantity of coal used in a blast furnace, for instance, is reduced relative to its yield, the increased number of furnaces will more than compensate for the reduced consumption of each' (Jevons, 1866, p. 125). Greater efficiency lowers the price of energy with two major consequences: raising profitability, thereby attracting more capital into the industrial sector, and cutting the price of goods, thus fostering overall demand. Ultimately, the gains from energy efficiency might be completely taken back by the escalation in supply and demand. When this happens, the circumstances are described as a rebound effect or take-back effect (for convenience of exposure we just mention the direct rebound effect).

Hence, the point arising is that there is no certainty around whether iron dematerialization at the company level produces a macroeconomic impact on overall coal consumption. Regarding the American iron industry, our suspicions nonetheless tend towards dematerialization occurring with null take-back effects on the macroeconomy. Cheaper pig iron did encourage greater recourse to iron but not on a large enough scale to erase the efficiency gains in fuel consumption. The industry achieved a form of dematerialization (using less coal per ton of pig iron) without triggering a surge in total coal burned – with the Jevons Paradox therefore not applying. This finding stems from observing the pig iron time series prices, which display a downward trend through to 1898, followed by a surge in price increases thereafter (Temin, 1964, p.284-285). Examining this issue more closely, our estimates demonstrate how, irrespective of ongoing fuel-saving practices, a blast furnace paid the price of USD 3.365 in 1880-85 for the coke needed to produce one ton of pig iron and ten years later paid $USD 4.731 (American Iron and Steel Association, 1913; Appendix 1: input technical coefficients). Advances in smelting ores with less fuel were therefore cancelled out by the rise in coal prices. Producers faced a cost floor that prevented unlimited expansion with the outcome being a zero-rebound effect.

It is certainly no coincidence that the abrupt rise in coal prices was preceded by public warnings over mineral exhaustion and coal shortages (Bennett, 1996, p.210-212; Warren, 2001, p.p.126,129, 226-230). These warnings should not be read literally, over the depletion of physical reserves, but rather as the concerns over the long-term diminishing returns from mature coalfields. In this sense, coal exhaustion often meant extending the mining beyond the difficult sections in old basins and towards new districts, such as those in Upper Connellsville, Lower Connellsville and Eastern Kentucky, where mining conditions were different and often producing poorer quality coal (Warren, 2001, p.120-152). Placing theit words in the historical context, these commentators were getting off their chest concerns over the exhaustion of good quality coking coal for the iron industry.

While business was thriving, the times were not easy. Blast furnace owners had to cope with mixed economic signals: on the one hand, unprecedented conditions for efficiency, speed and raw material savings; on the other hand, price volatility with the inversion in the long-term low energy prices and the dominance of a few giant consolidated firms. Fuel then became a limiting factor: the more the industry attempted to expanded, the more it pushed on the availability of energy, undermining the incentives for expansion. For a better understanding of this peculiar manufacturing environment and the null rebound effect, table 3 depicts the cross-correlation between the price of pig iron made with Great Lakes ores and the quantities of pig iron produced in blast furnaces with coke and bituminous coal.

The cross-correlation of these time series, the prices, and quantities, in

Table 3, provides the correlation between the series values at different points in time. By this means, we may not only ascertain the direction of the changes but also the timeframe of their occurrence. The first column indicates time lags, ranging from -10 years to +10 years. A positive lag means Q is shifted forward relative to P. In other words, lag 5 correlates Price(t) with Quantities(t+5). Inversely, lag -5 correlates Price(t) with Quantities(t-5). The cross-correlation function is normalized to obtain a time-dependent Pearson correlation coefficient of the two series in the presence of time lags. Accordingly, an r close to ±1 indicates a very strong relationship while an r verging on 0 means there is no effective linear connection. Similarly, a positive r means that when one series increases, the other follows suit while a negative r portrays an increase in one series producing a decrease in the other (an inverse relationship). The results set out in table 3 display a predominantly negative r, signaling an inverse relationship as duly expected. However, the timing matters greatly. When both series are simultaneous (lag 0), changes in Prices and Quantities tend to head in opposite directions even though the correlation remains weak or even incidental r = (-0.404). In the ensuing years, decreases in Prices continue to be trailed by increases in Quantities increasing even if the relationship remains weak up to lag +4. In other words, annually falling prices only correspond to a modest immediate rise in output or, in the other direction, year-to-year price rises only correspond to modest output decreases. Thus, the null rebound effect argument aligns with these results. During this period, U.S. pig iron production did expand markedly, roughly doubling every decade. However, this output growth was a slow, multi-decade expansion. Cross-correlation confirms how one-year price changes only produced a weak effect on output, refuting any notion of an immediate rebound. In sum, table 3 seems to illustrate a “wait and see” attitude: the R values only attain greater significance between lag 6 and lag 10: Price(t) Quantities(t+6); Price(t) Quantities(t+10). Even though a minimal interpretation might maintain the decline in Prices and the rise in Quantities is phased over time by medium term lags, this might furthermore convey how price signals need reinforcing over a sequence of years before triggering a transformation in quantities: thus, a “wait and see” attitude. Rather than immediately expanding output whenever prices dropped, businessmen sat through several years of favorable prices before investing in new capacity (and in keeping with the positive correlation conjecture). Several reasons serve to explain this lag. First, expanding iron production, building new blast furnaces or enlarging mines, requires additional time to plan, particularly in conjunctures when the most favorable locations near transportation facilities are already occupied. Secondly, the iron industry was undergoing structural changes that encouraged caution. Dematerialization took place against a backdrop of increasing concentration in the industry; the number of blast furnaces decreased but those in production increased in size. With fewer companies, producers wanted to avoid over expansion. If any company boosted its output too quickly, it might flood the market with disappointing results and face takeover threats. Businessmen were conscious of over-expansion with this economic hazard fostering disincentives to immediately exploit price changes. “Wait and see” translated the competitive risks of raising production further in an industry with ever bigger players. Growing uncertainty impacted on time preferences (Allais and Hagen, 1979¸ Kahneman and Tversky,1979) On the other hand, with giants like U.S. Steel on the horizon, informal collusion or understandings among large producers likely prevented excessive competition. Should prices fall too low, firms would cut back production to avoid ruinous competition or even price wars. Additionally, the railroad boom ended in the 1890s and the Panic of 1893 sent scary signals that upset demand for iron. Hence, factors including economic cycles and limits on demand kept potential rebound effects in check.

The cross correlation delay is furthermore consistent with investment lead times and strategic caution. All external pressures – rising input costs, cautious corporate behaviors, Darwinian competition, the cooling of the railroad boom and sporadic business cycle panics – shaped a context in which no strong rebound effect could take hold. Overall, the statistical results depict a consistent picture: price and quantities moving in opposite directions but with a non-instantaneous impact of price on output. Most of the Confidence Intervals lie below zero thereby confirming the inverse correlation. The only exception occurs at lag -4 where the 95% Confidence Interval is about [-0.620, 0.003], reflecting a lack of reliability in the correlation at lag -4. All positive lags display p-values below 0.05, reporting the correlations that are statistically significant and not due to random chance.

To resume, dematerialization was ingrained in the north-east moving frontier because this erased the very idea of technological boundaries: the Great Lake ores wiped out the distinctions among charcoal, anthracite and coke furnaces through the diffusion of common smelting practices and similar results. The borderless industry at the close of the nineteenth-century cut the linkages with the traditional hallmarks: confronted with rising levels of wood depletion, charcoal furnaces resorted to blended fuels mixing charcoal with coke. Similarly, in around 1880, anthracite and coke furnaces began gaining recognition as distinct technologies on their own. As the title here pinpoints, the boundaries between technologies became increasingly blurred (Bennett, 1996, p151-152; Warren, 2001, p.31, 38)

4. Concluding Remarks

These findings return us to the central question posed in Chapter 1: what drives energy transitions in complex, resource-rich societies?

American industrialization has disclosed different patterns in the relationship between fuels and metals. Three industrial transitions correspondingly stand out: in the first, coal generates incentives for iron production through low energy prices; in the second, iron production sparks ever further coal exploration through upscaling and vertical integration, finally, in the third, iron conserves coal through dematerialized production. America’s entry into the fossil fuel age was a phase-dependent progression. The “exceptionalism” of this path, with its threefold “Rust Belt history,” underscores the value of detailed historical and regional analysis , and was rendered feasible by the vastness of America: if the iron industry underwent a triple renaissance, this stemmed from the moving frontier that displaced huge reserves of natural resources: the Anthracite boom on the Atlantic Coast was followed by the bituminous coal breakthrough in the Appalachian Mountains and then by iron ore pouring out of the Great Lakes. The co-relationship between coal and iron shifted across each of these frontiers. Looking at the way people felt at different historical times, the idea of a threefold rust belt is corroborated by contemporary insights regarding the cycles of city peaks and declines: Philadelphia, Pittsburgh and then Chicago.

"In the beginning was the Price.” Much like John 1:1, the lesson drawn from the first emergence of the coal and iron industry in Eastern Pennsylvania singles out the determinant factor of lower fuel prices as the precondition for this industrial take-off. Considering the local history context, one might conclude that the development of anthracite blast furnaces was part and parcel of an overarching investment in transportation improvements, whose ultimate result was the drop in coal prices along with the regularity of supply. Strikingly, the pace of events in Pennsylvania’s energy transition quite closely resembles events in the British industrial revolution. In both cases, the progress in manufacturing was preceded by growth in the household market for energy and the capacity to cut coal prices. Perhaps the scarcity of wood, the alternative fuel, may even be added to this parallelism. The energy transition was led by fuels prices and infrastructure improvements, validating the “energy services” perspective to a point, but also highlighting the role of material supply and market creation. Much of the current debate around decarbonization and energy transition might benefit from the historical perspective provided by Pennsylvania’s iron industry: energy transitions are triggered by prices and transportation improvements. In other words, fuels along with energy services lead the way.

Once the energy transition is actually underway, everything changes. In the second moving frontier in Western Pennsylvania and Ohio, technology (iron) rather than fuel (coal) lead the way. Iron innovations took place in two periods: in the middle of the century, coal forged into wrought iron production with the establishment of puddling and rolling mills. In one fell swoop, these technologies reached production volumes of incomparable dimension (incomparable with the existing forges and bloomeries), advancing economies of scale throughout the whole productive cycle and exploring markets for new products like rails, agricultural hardware and sheet iron. Twenty years later, a unit scale frontier was also attained in pig iron production with a new dominant cupola furnace design entailing reinforced structures of cast-iron walls, columns and mantles. These taller plants operated by multiple blowing engines enabling a larger capacity of iron ore and flux yielding larger volumes of pig iron in less time. The double upscaling dragged coal consumption along two pathways: because scale economies lowered the average cost of iron goods; because they introduced disequilibria into the productive cycle (pig iron/wrought iron) fostering extra investments and vertical integration, particularly between manufacturing and the supply of raw materials. Finally, the growth of industrial establishments generated additional investment in coal mining. Earlier mid-century attempts at integration (common ownership of rolling mills and blast furnaces) promoted operational efficiencies but did not result in industrial giants. However, by the 1880s–90s, the full consolidation of mines, coke ovens, furnaces, and mills under companies including Carnegie Steel and Illinois Steel did produce giant ‘empires’, firmly bonding coal and iron interests. True dominance stemmed from the consolidation of resources rather than simple integration. As aforementioned, in this stage, technology leads the way.

It is tempting to explain the rapid occupation and colonization of the third frontier, the Great Lakes, as a response to the production boom generated by iron upscaling and the ensuing pressure upon coal and coke resources. In fact, fuel savings and fuel conservation explain the overwhelming domination of Great Lake ores in a short period of time. Iron production processes must thereafter conserve coal.

Most integrated firms and the large, consolidated empires fastened their eyes on the iron mines of northeast-central America. Following intensive exploration, the frozen wilderness was turned into civilization. More specifically, this endowed a dense network with cornucopias of railroads and steamships. Once again, mining centers attracted the installation of manufacturers. However, the Great Lakes, became not just an iron-based industrial center but, and primarily, a steel magnet.

Regarding the consequences of the high-quality Great Lake ores upon the whole iron and steel industry, the present text confirms the perception of benefits arising from dematerialization, efficiency gains and productivity growth. However, we would also add a brief note that raw material savings did encourage more use of iron but not enough to wipe out the efficiency gains obtained in fuel usage. Thus, we put forward a nuanced perspective that might provide a hopeful message for contemporary policy: supply-side effects like energy costs, cautious investment, demand saturation and business cycle downturns might keep rebound effects in check.

Overall, this essay reinforced the introductory claim that new products, as much as new services, can drive transformative shifts in energy use.

To be fair, any description of the American iron industry should guard a place of honor for the men who pushed forward the vision, the technology, through entrepreneurship and reciprocal collaboration that steered decades of economic improvements and resilience. Fortunately, we know who they are.

Through the “moving frontier” concept, the current article instead picks out the land of riches as the key actor, emphasizing the quality and abundance of natural resources in the vast American landscape. Cheap energy, technological innovation, and resource quality operated in conjunction. Moreover, it was these resources that furthered the triple resurrection of the industry: the historical layers of the Rust Belt.