Introduction

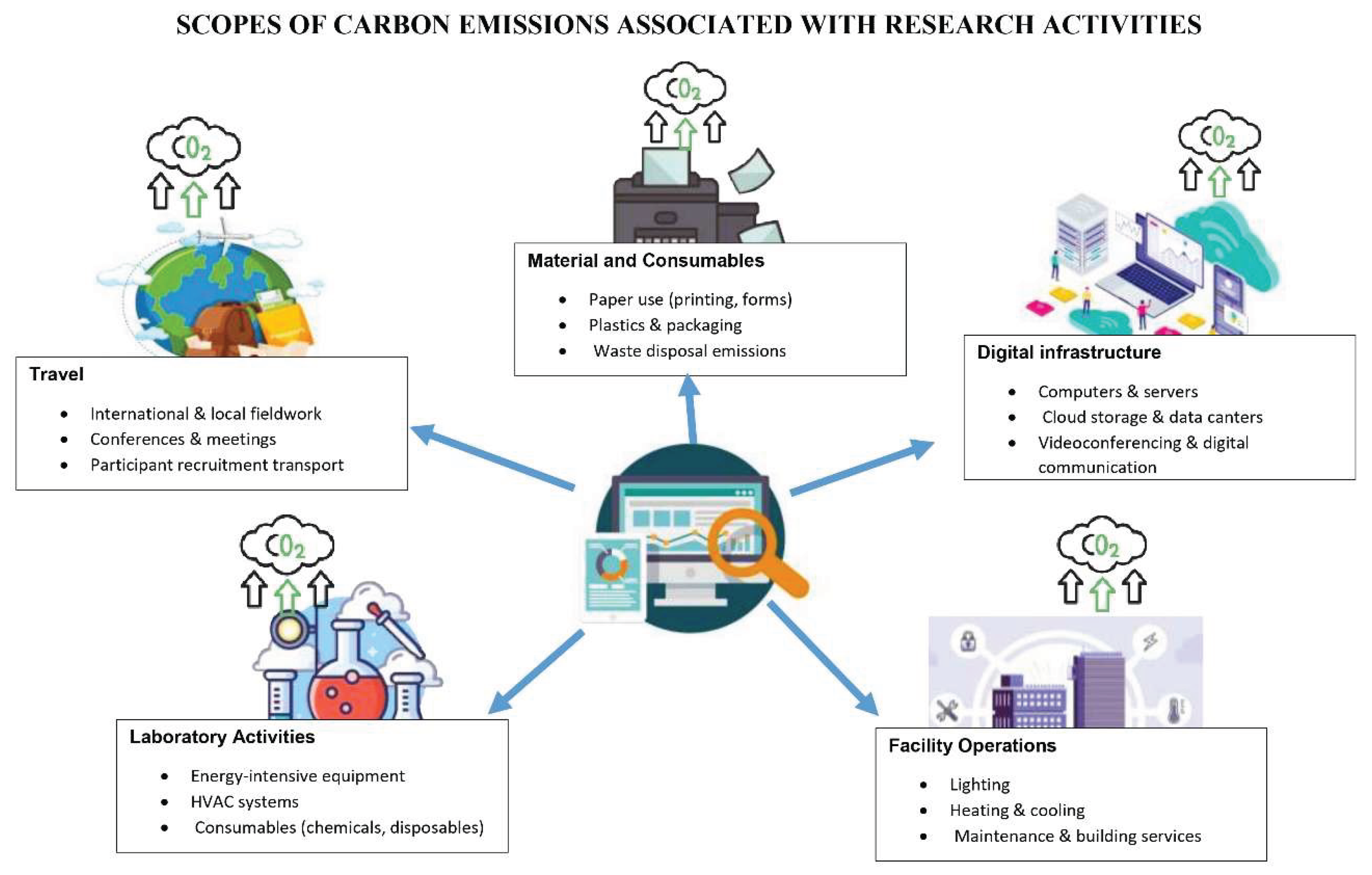

Scientific research is one of the most reliable way to find solutions to some of the World’s most pressing issues from health challenges to climate change itself. The process of delivering research studies particularly those of international scope, carries a significant environmental burden, primarily arising from activities embedded within the research lifecycle (

Figure 1). These include, but are not limited to, international travel for fieldwork and conferences, energy-intensive laboratory processes, material usage such as paper and plastic, and the increasingly pervasive reliance on digital infrastructures [

1,

2]. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) without urgent reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, temperatures could rise by an additional

4°C this century and increase the adverse impacts on ecosystems, Human health and overall planetary stability [

3]. As the climate crisis intensifies, the carbon footprint associated with academic research has emerged as a pressing concern within scholarly and policy-making spheres. This aligns with broader global commitments such as the Paris Agreement and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 13 (Climate Action) and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) [

4].

A carbon footprint refers to the total volume of greenhouse gases (GHGs), notably carbon dioxide (CO

2), methane (CH

4), and nitrous oxide (N

2O), released into the atmosphere as a direct or indirect result of human activity [

5]. These emissions accumulate across different components of research practice, and although individual contributions may appear minor, their cumulative effect is substantial, particularly when considering large-scale or multi-site studies. International collaborations, while critical for generating representative and impactful scientific evidence, often carry disproportionately high environmental costs. The academic community is now being called upon to reconcile the demands of rigorous, inclusive research with the imperative to reduce environmental harm [

6]. For example, a single return flight between London and Kuala Lumpur emits roughly two tonnes of CO

2 per passenger, which approximates the annual per capita emissions in several low-income countries. Field activities in geographically dispersed or hard-to-reach areas further increase the carbon intensity of studies, especially when multiple site visits or shipment of equipment is involved.

Recent literature suggests that the quantification of research-related carbon emissions has increased markedly in recent years, indicating growing awareness of the ecological cost of academic enterprise. Yet, much of this work remains centred on high-level estimations or institution-wide assessments. Few studies have undertaken project-specific evaluations that scrutinise the carbon implications of individual research practices, particularly recruitment strategies [

7]. Given that many global health studies span multiple geographies, require multilingual coordination, and depend heavily on diverse recruitment channels, a more granular understanding of emissions tied to specific activities is urgently needed.

Paper use, often perceived as a minor contributor, plays a significant role in administrative, recruitment, and data collection processes. Printing participant information sheets, consent forms, and mailing questionnaires results in a steady, cumulative environmental impact, particularly when participant numbers are high—as is often the case in epidemiological or public health research.

Recruitment methods are another underexplored source of emissions. Traditional in-person recruitment often involves physical travel, resource-heavy printing, and extended face-to-face interactions. Conversely, digital recruitment, while potentially reducing emissions from travel and printing, introduces its own challenges. Cloud-based data management, videoconferencing, and digital advertising all require substantial computational power, typically driven by electricity sourced from fossil fuels. These “invisible” emissions have become more relevant in the era of remote and hybrid research models.

The need for targeted strategies to mitigate these emissions is growing. Solutions such as virtual conferencing, hybrid recruitment models, and the use of energy-efficient digital tools are increasingly being explored. Nonetheless, sustainable research demands more than ad hoc adjustments. It requires a proactive reconfiguration of how studies are designed, funded, and executed embedding sustainability into every phase of the research lifecycle.

Scientific Rationale

There is a need to explore principal sources of emissions such as travel, paper use, and recruitment methods. These were identified as areas where researchers and institutions can exercise control and implement environmentally responsible alternatives. Travel, particularly long-haul flights for conferences, coordination meetings, or fieldwork. constitutes a major source of emissions.

Understanding how different recruitment strategies contribute to carbon output is critical for establishing more sustainable research protocols. This is especially pertinent for international studies that operate across regions with varying access to digital infrastructure, logistical constraints, and environmental regulations. By quantifying emissions linked to paper-based, digital, and in-person recruitment methods, we aim to provide evidence-based recommendations for optimising participant engagement in a manner that aligns with SDG targets. As research funders increasingly require sustainability considerations in grant applications and institutional audits, this work offers an important contribution to policy and operational planning. It provides a replicable framework for other research programmes, particularly those in global health to evaluate and reduce their environmental impact without compromising scientific integrity or inclusivity.

We examined the carbon footprint of recruitment methods used within the

MARIE Project’s work-package 2a (WP2a) to generate actionable insights for future research design [

8,

9,

10]. The rationale stems from an urgent scientific and ethical responsibility to reduce emissions within academic practice and align research conduct with climate goals.

Methods

Study Design

This comparative carbon emissions analysis was embedded within an Exploration of the Mental Health impact among Menopausal Women (MARiE) Project, a multi-country women’s health research study. The study evaluated the environmental impact of three recruitment modalities: (i) traditional (in-person), (ii) digital (online), and (iii) hybrid approaches. The assessment included eight data gathered from Malaysia, Brazil, Sri Lanka, India, United Kingdom, Nigeria, Ghana, and Singapore with heterogeneous digital infrastructure and health system capacities.

Data Sources and Assumptions

Emission estimates were derived using current published standardised, publicly available emission factors from authoritative sources, including:

Where exact usage data were unavailable, estimations were made using contextual averages, with device usage, travel distance, and electricity consumption standardised per participant. All countries’ activities were compared across equivalent parameters to maintain internal validity.

Carbon Emissions Estimation

Emissions were calculated in kgCO2e using activity-specific formulas:

-

Material Usage:

- ○

Paper: CO2e = weight of paper (kg) × EF (1.0 kg CO2e/kg)

- ○

Toner: CO2e = number of printed pages × 1g CO2/page

-

Electricity Consumption:

- ○

CO2e = kWh used × country-specific emission factor

-

Transport:

- ○

CO2e = Σ (travel distance per participant × emission factor per km × number of participants × proportion using transport mode)

-

IT Devices:

- ○

CO2e = device type × energy usage/hour × hours used × national carbon intensity

Assumptions about transport type, travel distance, and recruitment times were kept conservative to avoid overestimation. Public transport was excluded where unavailable or minimal. Devices reused or recharged outside the project scope were excluded from emissions attribution.

Statistical Analysis

All emissions data were entered into Microsoft Excel and R (v4.3.1) for comparative summary statistics. Descriptive analyses included frequency distributions and mean CO2e emissions by recruitment modality and country. One-way ANOVA was used to assess differences in total CO2e across recruitment types. Post-hoc Tukey’s HSD test identified pairwise differences. A Kruskal-Wallis test was additionally conducted as a non-parametric sensitivity check due to non-normality in some emission categories (notably transport emissions in India and Malaysia). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Limitations

The study’s limitations included variations in the quality and completeness of data provided by investigators across different countries.

Data Collection

Data were collected from primary investigators involved in the MARIE project, a global research initiative with participation from multiple countries. The collection process incorporated both primary and secondary data sources to ensure a comprehensive assessment:

Primary Data

Primary data were collected through structured surveys and questionnaires administered to research teams across the participating countries. These instruments were designed to capture detailed information on paper usage, including the volume of materials printed and the types of printing equipment utilised. Respondents were also asked to specify the methods of participant recruitment whether paper-based, digital, or a combination of both. In addition, data were gathered on travel distances and modes of transportation used by participants to access recruitment locations, allowing for calculation of transport-related emissions. The surveys further captured the types of digital tools employed in recruitment activities, such as tablets, computers, and mobile phones, providing a comprehensive overview of the technological footprint associated with each method.

Secondary Data

Secondary data were drawn from a range of authoritative sources to support and contextualise the primary findings. These included published reports and peer-reviewed scientific literature addressing emissions, carbon accounting, and sustainability in health research. Emission factors were applied based on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) guidelines [

14], ensuring standardised and internationally accepted metrics for estimating carbon outputs. Additionally, country-specific carbon emission statistics and environmental databases were consulted to align the emissions estimates with local energy profiles and socio-economic conditions, thereby enhancing the accuracy and relevance of cross-country comparisons.

Data Analysis

Emissions Sources

The emission sources related to MARIE project activities are estimated in the following methodology of Carbon footprint are the following: Direct emissions from participant recruitment methods, including the use of paper and digital tools, indirect emissions from electricity consumption during research activities, Transportation and printable deliverables. A detailed description of the methodology used (activity data, statistics, emissions factors) for the CF calculations of each emission source is presented in the following subsections.

Results

Recruitment Modality and Emissions Burden

Across the 3,875 participants recruited, digital methods dominated (67.1%), reducing overall emissions from material usage and participant travel. Notably, countries using in-person recruitment in India, Malaysia, Sri Lanka recorded significantly higher emissions due to paper use, printer energy, and transportation. Conversely, countries using digital-only recruitment such as the UK, Brazil, Nigeria, and Ghana recorded near-zero emissions from travel and material use but small emissions from IT device use.

Table 2.

Total carbon emissions (kg CO2e) associated with different recruitment methods across countries, highlighting the substantial variation in emissions between digital, hybrid, and in-person approaches.

Table 2.

Total carbon emissions (kg CO2e) associated with different recruitment methods across countries, highlighting the substantial variation in emissions between digital, hybrid, and in-person approaches.

| Country |

Recruitment Method |

Total Emissions (kgCO2e) |

| Brazil |

Digital |

0.227 |

| UK |

Digital |

0.396 |

| Nigeria |

Digital |

0.437 |

| Ghana |

Digital |

0.362 |

| Singapore |

Digital |

769.628 |

| Sri Lanka |

Hybrid |

125.958 |

| Malaysia |

In-person |

4260.314 |

| India |

In-person |

27070.063 |

In-person recruitment methods, used in India and Malaysia, generated the highest carbon emissions, with totals exceeding 4,000 kgCO2e and 27,000 kgCO2e, respectively. Hybrid recruitment in Sri Lanka resulted in moderate emissions of approximately 126 kgCO2e, reflecting mixed paper use and transport impact. In contrast, digital recruitment across Brazil, UK, Nigeria, Ghana, and Singapore produced negligible emissions ranging from 0.227 kgCO2e to 769.628 kgCO2e underscoring the environmental benefits of virtual participant engagement (Table 1; supplement 1).

Material Usage Disparities

Countries using in-person recruitment produced measurable CO2e from virgin paper and toner. Malaysia generated the highest emissions (31.387 kgCO2e), driven by a higher number of printed pages (n=4487) and the exclusive use of virgin paper. Sri Lanka and India followed with identical paper quantities (2,000 sheets), each producing ~14 kgCO2e (supplement 1). In contrast, digitally recruiting countries produced no emissions from printed materials, demonstrating a clear carbon-saving advantage.

Electricity Consumption

Electricity emissions mirrored material use, arising exclusively from printer operations. Malaysia again led (2.367 kgCO2e), followed by India (1.863 kgCO2e) and Sri Lanka (1.078 kgCO2e) (supplement 1). This variation was due to emission factor differences and printer operation durations. Countries relying on digital methods reported zero emissions from printer electricity, highlighting the ancillary environmental benefits of digitisation.

Digital Recruitment and Device Emissions

Although often perceived as “carbon neutral,” digital recruitment generates measurable emissions primarily through device use, network data transfer, and supporting cloud infrastructure. These contributions were determined by combining activity data such as the duration of videoconferencing, estimated data transfer volumes, and device operating hours with country-specific electricity grid emission factors. The resulting figures highlight that device electricity consumption, while modest relative to transport in in-person recruitment, remains a minor but non-negligible contributor to total emissions.

Among the digital-only countries, Nigeria exhibited the highest digital carbon footprint (0.437 kgCO2e), followed closely by the UK (0.396 kgCO2e) and Ghana (0.362 kgCO2e). Brazil reported a lower footprint (0.227 kgCO2e), reflecting the predominance of hydroelectricity in its national energy mix, which substantially reduces the carbon intensity of electricity consumption. Singapore, in contrast, recorded the lowest footprint (0.118 kgCO2e), attributable to a smaller participant cohort and the application of lower per-unit grid intensities for electricity consumption.

Crucially, while these values demonstrate that digital recruitment is not emission-free, they remain orders of magnitude lower than emissions associated with hybrid or in-person approaches. This provides strong evidence that virtual participant engagement offers a markedly more sustainable pathway for large-scale research recruitment.

To assess whether

participant recruitment modality of in-person versus digital, and hybrid approaches significantly influenced the

total carbon emissions across countries (

Table 3) participating in the MARIE project, we conducted both

parametric and

non-parametric statistical analyses.

The emissions associated with in-person methods were orders of magnitude higher, primarily due to travel-related emissions. However, digital methods, despite using electronic devices, remained consistently low in emissions across all countries. We conducted a one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to determine if mean emissions differed significantly between recruitment modalities with a null hypothesis (H0) with a mean total emissions are equal across all recruitment methods with a test statistic, F(2,5) of 3.46 and a p-value of 0.114. This is statistically insignificant although the conventional alpha (0.05) is moderate F-value indicating potential differences in group. This suggestive trend indicating that recruitment modality may impact carbon emissions, but the small number of countries per group limited statistical power.

Kruskal-Wallis Test (Non-Parametric Alternative)

Given the small group sizes (n=2–5 per method) and non-normality of emissions data particularly the extreme values for India and Malaysia, the Kruskal-Wallis H test, a rank-based non-parametric alternative showed the null hypothesis (H0) indicating the distributions of emissions are the same across recruitment methods with a test statistic (H) 4.45 and a p-value of 0.108 (supplement 2).

Similar to ANOVA, this test showed no statistically significant difference in emissions by recruitment method. However, the trend remains consistent in-person methods result in higher emissions compared to hybrid and digital methods. Statistical significance was not achieved, the magnitude of difference in carbon emissions particularly between digital (mean ≈ 0.3 kgCO2e) and in-person methods (mean ≈ 15,600 kgCO2e) is stark and practically important (supplement 2). Even with conservative estimates, digital recruitment methods appear to offer a ten-thousand-fold reduction in carbon impact. These findings offer strong empirical justification for adopting digital or hybrid recruitment strategies in global health research not only for cost and accessibility, but also for environmental sustainability.

Discussion

This comparative carbon emissions analysis, conducted as part of the MARIE study, evaluated the environmental impact of participant recruitment methods across eight countries. The findings demonstrate substantial differences in carbon footprint depending on the modality of recruitment. In-person recruitment methods, utilised in India and Malaysia, generated markedly high emissions dominated by transport-related CO2e due to participant and staff travel. India alone accounted for over 27,000 kgCO2e, while Malaysia contributed more than 4,200 kgCO2e. In contrast, digital recruitment methods used in Brazil, the UK, Nigeria, Ghana, and Singapore resulted in negligible emissions, with the highest among them being Singapore at 770 kgCO2e due to a mix of digital and low-emission transport modes. The hybrid model implemented in Sri Lanka produced moderate emissions (~126 kgCO2e), primarily from modest paper use and short-distance travel. Statistical analyses, while not reaching significance due to small sample size, consistently showed directionally robust trends favouring digital methods as environmentally sustainable alternatives.

Improving Carbon Emissions by Using Digital Recruitment

LMICs often prefer face-to-face recruitment methods, particularly during baseline visits in research studies, due to several interrelated factors. First, personal interactions are critical in these settings to build trust and rapport between researchers and participants. Face-to-face recruitment allows researchers to address concerns directly, explain study objectives clearly, and ensure participants feel valued and understood. This approach frequently results in higher participation rates and more reliable data collection.

Digital recruitment methods offer significant potential to reduce the carbon footprint of health research, particularly by eliminating emissions associated with paper use and travel [

15]. Our findings reveal that in-person recruitment contributes disproportionately to total emissions, with travel alone accounting for over 90% of emissions in countries like India. In contrast, digital recruitment minimised emissions to under 1 kgCO

2e in most cases, driven only by low-energy device usage. From a scientific standpoint, the advantages of digital recruitment extend beyond environmental considerations; it enables rapid participant outreach, scalability, and standardisation of recruitment materials. However, digital methods also face notable limitations. In low-resource settings, digital access remains unequal, with infrastructural barriers such as unreliable internet, digital illiteracy, and power supply inconsistencies. Moreover, certain populations such as older adults or those with low literacy may be systematically excluded from digital participation, raising ethical concerns regarding inclusivity and sampling bias. Thus, while digital recruitment is environmentally superior, its deployment must be adapted to contextual realities to ensure both equity and efficacy.

Practical Implications

Implementing carbon-reducing strategies in global health research is fraught with practical, cultural, and infrastructural challenges. In many LMICs such as India, Sri Lanka, and Nigeria, underdeveloped public transport systems compel researchers and participants to depend on high-emission private vehicles. Simultaneously, the routine use of virgin paper and toner reflects institutional procurement practices that often prioritise convenience over sustainability. Addressing these issues demands a nuanced and locally grounded approach. Investment in digital infrastructure, coupled with digital literacy initiatives, can facilitate a transition to more sustainable virtual recruitment. However, the solution is not as simple as switching to digital platforms. Technological access and literacy remain substantial barriers in LMICs. In such contexts, face-to-face recruitment plays a vital role in bridging digital divides and ensuring that all potential participants, regardless of their technological proficiency, can be included.

The benefits of in-person recruitment also extend to ethical and cultural dimensions. Personal interactions enable researchers to explain study protocols verbally, addressing literacy gaps and ensuring informed consent is truly understood. Cultural sensitivity is better achieved in face-to-face settings, where verbal communication allows for real-time adaptation to social norms and expectations. Data quality tends to improve with in-person recruitment, as researchers can immediately clarify misunderstandings and establish trust. These practical realities necessitate that carbon reduction strategies be both ethically sound and contextually adaptable. Rather than imposing a rigid digital-first model, global health research must promote hybrid strategies that blend the environmental efficiency of digital methods with the ethical and logistical strengths of in-person engagement. Where digital recruitment is feasible, its environmental advantages should be maximised. Where face-to-face recruitment is essential, it should be supplemented with low-emission transport options, recycled materials, and carbon-conscious planning.

Sustainability and the SDGs

Our findings carry significant implications for national and global commitments to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), and SDG 13 (Climate Action). The MARIE project reveals that high-emission recruitment practices, particularly in-person approaches reliant on travel and paper are misaligned with these sustainability targets. If scaled across global research programmes, such practices would substantially undermine efforts to decarbonise health systems and public health research. Conversely, digital methods align with low-carbon development goals and offer a pragmatic avenue for reducing environmental impact without compromising research quality. For countries already investing in e-health and digital infrastructure, research recruitment offers a synergistic opportunity to leverage these systems for environmental gains. However, realising this potential requires national strategies that integrate health research into broader climate action plans. Importantly, sustainability must be viewed not just as a technological transition, but as a systems-level responsibility involving ethics committees, funders, institutions, and local communities.

The recommendations (

Table 4) emphasise the importance of transitioning towards environmentally sustainable recruitment practices in global health research. Prioritising digital and hybrid methods can substantially reduce emissions associated with travel and paper use, while maintaining research integrity. However, equitable access must be ensured by developing inclusive digital tools and investing in infrastructure within low-resource settings. Embedding carbon impact assessments into funding and ethical approval processes will support accountability and align research activities with national and global sustainability goals.

Strengths and Limitations

Only eight observations were included, with unequal group sizes. This severely limits inferential power and increases the likelihood of Type II error. Country-level clustering was not controlled for; future work should use multilevel modelling to adjust for between-country variance. The ANOVA assumes normality and homogeneity of variances, both of which are likely violated here, further justifying non-parametric approaches. India’s emissions were disproportionately high due to long average travel distances and large participant volume, which skewed group means.

Conclusion

This study highlights that recruitment methods for global health research vary substantially in their carbon footprint, with in-person approaches generating disproportionately high emissions. Digital recruitment offers the most sustainable pathway, producing negligible emissions and aligning closely with global commitments. However, equity and contextual realities such as digital divides, literacy gaps, and cultural considerations necessitate flexible hybrid models rather than rigid digital-only strategies. Embedding carbon impact assessments into research design, funding, and governance will be essential to ensure that sustainability goals are achieved without compromising inclusivity or research integrity.

Author contributions

GD developed the ELEMI program and embedded the MARIE project. GD conceptualised the methodology. MARIE chapter teams in Malaysia (led by TTH), Singapore (led by IMA), Sri Lanka (led by NR), India (led by PKM), UK (led by PP), Brazil (led by CBP), Ghana (led by FKT) and Nigeria (led by GUE) conducted the recruitment. First draft was written by GD and furthered by all other authors. TTH, TM, IM, completed data collection. GD, AS and JQS conducted the analysis. All authors critically appraised, reviewed and commented on all versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

NIHR Research Capability Fund

Availability of data and material

The data shared within this manuscript is publicly available.

Code availability

Not applicable

Ethics approval

Not applicable

Consent to participate

No participants were involved within this paper

Consent for publication

All authors consented to publish this manuscript

Acknowledgements

MARIE collaboration MARIE COLLABORATIVES Aini Hanan binti Azmi, Alyani binti Mohamad Mohsin, Arinze Anthony Onwuegbuna, Artini binti Abidin, Ayyuba Rabiu, Chijioke Chimbo, Chinedu Onwuka Ndukwe, Choon-Moy Ho, Chinyere Ukamaka Onubogu, Diana Chin-Lau Suk, Divinefavour Echezona Malachy, Emmanuel Chukwubuikem Egwuatu, Eunice Yien-Mei Sim, Farhawa binti Zamri, Fatin Imtithal binti Adnan, Geok-Sim Lim, Halima Bashir Muhammad, Ifeoma Bessie Enweani-Nwokelo, Ikechukwu Innocent Mbachu, Jinn-Yinn Phang, John Yen-Sing Lee, Joseph Ifeanyichukwu Ikechebelu, Juhaida binti Jaafar, Karen Christelle, Kathryn Elliot, Kim-Yen Lee, Kingsley Chidiebere Nwaogu, Lee-Leong Wong, Lydia Ijeoma Eleje, Min-Huang Ngu, Noorhazliza binti Abdul Patah, Nor Fareshah binti Mohd Nasir, Kathleen Riach, Norhazura binti Hamdan, Nnanyelugo Chima Ezeora, Nnaedozie Paul Obiegbu, Nurfauzani binti Ibrahim, Nurul Amalina Jaafar, Odigonma Zinobia Ikpeze, Obinna Kenneth Nnabuchi, Pooja Lama, Puong-Rui Lau, Rakshya Parajuli, Rakesh Swarnakar, Raphael Ugochukwu Chikezie, Rosdina Abd Kahar, Safilah Binti Dahian, Sapana Amatya, Sing-Yew Ting, Siti Nurul Aiman, Sunday Onyemaechi Oriji, Susan Chen-Ling Lo, Sylvester Onuegbunam Nweze, Damayanthi Dasanayaka, Nimesha Wijayamuni, Prasanna Herath, Thamudi Sundarapperuma, Jeevan Dhanasiri, Vaitheswariy Rao, Xin-Sheng Wong, Xiu-Sing Wong, Yee-Theng Lau, Heitor Cavalini, Jean Pierre Gafaranga, Emmanuel Habimana, Chigozie Geoffrey Okafor, Assumpta Chiemeka Osunkwo, Gabriel Chidera Edeh, Esther Ogechi John, Kenechukwu Ezekwesili Obi, Oludolamu Oluyemesi Adedayo, Odili Aloysius Okoye, Chukwuemeka Chukwubuikem Okoro, Ugoy Sonia Ogbonna, Chinelo Onuegbuna Okoye, Babatunde Rufus Kumuyi, Onyebuchi Lynda Ngozi, Nnenna Josephine Egbonnaji, Oluwasegun Ajala Akanni, Perpetua Kelechi Enyinna, Yusuf Alfa, Theresa Nneoma Otis, Catherine Larko Narh Menka, Kwasi Eba Polley, Isaac Lartey Narh, Bernard B. Borteih, Kingsley Emeka Ekwuazi, Michael Nnaa Otis, Jeremy Van Vlymen, Chidiebere Agbo, Francis Chibuike Anigwe, Kingsley Chukwuebuka Agu, Chiamaka Perpetua Chidozie, Chidimma Judith Anyaeche, Clementine Kanazayire, Jean Damascene Hanyurwimfura, Nwankwo Helen Chinwe, Stella Matutina Isingizwe, Jean Marie Vianney Kabutare, Dorcas Uwimpuhwe, Melanie Maombi, Ange Kantarama, Uchechukwu Kevin Nwanna, Benedict Erhite Amalimeh, Theodomir Sebazungu, Elius Tuyisenge, Yvonne Delphine Nsaba Uwera, Emmanuel Habimana, Nasiru Sani and Amarachi Pearl Nkemdirim, Ramiya Palanisamy, Victoria Corkhill, Kingshuk Majumder, Bernard Mbwele, Om Kurmi, Irfan Muhammad, Rabia Kareem, Lamiya Al-Kharusi, Nihal Al-Riyami, Olisaemeka Nnaedozie Okonkwo, Bethel Chinonso Okemeziem, Bethel Nnaemeka Uwakwe, Ifeoma Francisca Ndubuisi, Rukshini Puvanendran, Farah Safdar, Rajeswari Kathirvel, Manisha Mathur, Raksha Aiyappan

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflict of interest. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research, the Department of Health and Social Care or the Academic institutions.

References

- Gokus A, Jahnke K, Woods PM, Moss VA, Ossenkopf-Okada V, Sacchi E, et al. Astronomy’s climate emissions: Global travel to scientific meetings in 2019. Zhang J, editor. PNAS Nexus. 2024, 3, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capet X, Aumont O. Decarbonization of academic laboratories: On the trade-offs between CO2 emissions, spending, and research output. Cleaner Environmental Systems. 2024, 12, 100168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change (Ipcc). Climate Change 2021 – The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Internet]. 1st ed. Cambridge University Press; 2023. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/9781009157896/type/book (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Action on Climate and SDGs | UNFCCC [Internet]. Available online: https://unfccc.int/topics/cooperative-activities-and-sdgs/action-on-climate-and-sdgs (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Durojaye O, Laseinde T, Oluwafemi I. A Descriptive Review of Carbon Footprint. In: Ahram T, Karwowski W, Pickl S, Taiar R, editors. Human Systems Engineering and Design II [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 960–8. (Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; vol. 1026). Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-27928-8_144 (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Sweke R, Boes P, Ng N, Sparaciari C, Eisert J, Goihl M. Transparent reporting of research-related greenhouse gas emissions through the scientific CO2nduct initiative. Commun Phys. 2022, 5, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aujoux C, Kotera K, Blanchard O. Estimating the carbon footprint of the GRAND project, a multi-decade astrophysics experiment. Astroparticle Physics. 2021, 131, 102587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathiraja V, Kurmi O, Toh TH, Eleje GU, Tweneboah-Koduah F, Mbwele B, et al. Exploring the Availability and Acceptability of Hormone Replacement Therapy in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Insights of Pharmacists Using a Cross-Sectional Study (MARIE-Sri Lanka WP2a) [Internet]. 2025. Available online: https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202505.0167/v1 (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Delanerolle G, Cavalini H, Taylor J, Hinchliff S, Talaulikar V, Zingela Z, et al. An Exploration of the Mental Health impact among Menopausal Women: The MARIE Project Protocol (International Arm) [Internet]. 2023. Available online: http://medrxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2023.11.26.23299012 (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Delanerolle G, Phiri P, Elneil S, Talaulikar V, Eleje GU, Kareem R, et al. Menopause: a global health and wellbeing issue that needs urgent attention. The Lancet Global Health. 2025, 13, e196–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenhouse gas reporting: conversion factors 2024 [Internet]. GOV.UK. 2024. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/greenhouse-gas-reporting-conversion-factors-2024 (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Global Carbon Project (GCP) [Internet]. Global Carbon Project (GCP). Available online: https://www.globalcarbonproject.org/ (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Clim’Foot | [Internet]. Available online: https://www.climfoot-project.eu/ (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- IPCC Emissions Factor Database | GHG Protocol [Internet]. Available online: https://ghgprotocol.org/Third-Party-Databases/IPCC-Emissions-Factor-Database (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Domingo A, Singer J, Cois A, Hatfield J, Rdesinski RE, Cheng A, et al. The Carbon Footprint and Cost of Virtual Residency Interviews. Journal of Graduate Medical Education. 2023, 15, 112–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).