Submitted:

04 August 2025

Posted:

08 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Study Design

2.2. Matching

2.3. Outcomes

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

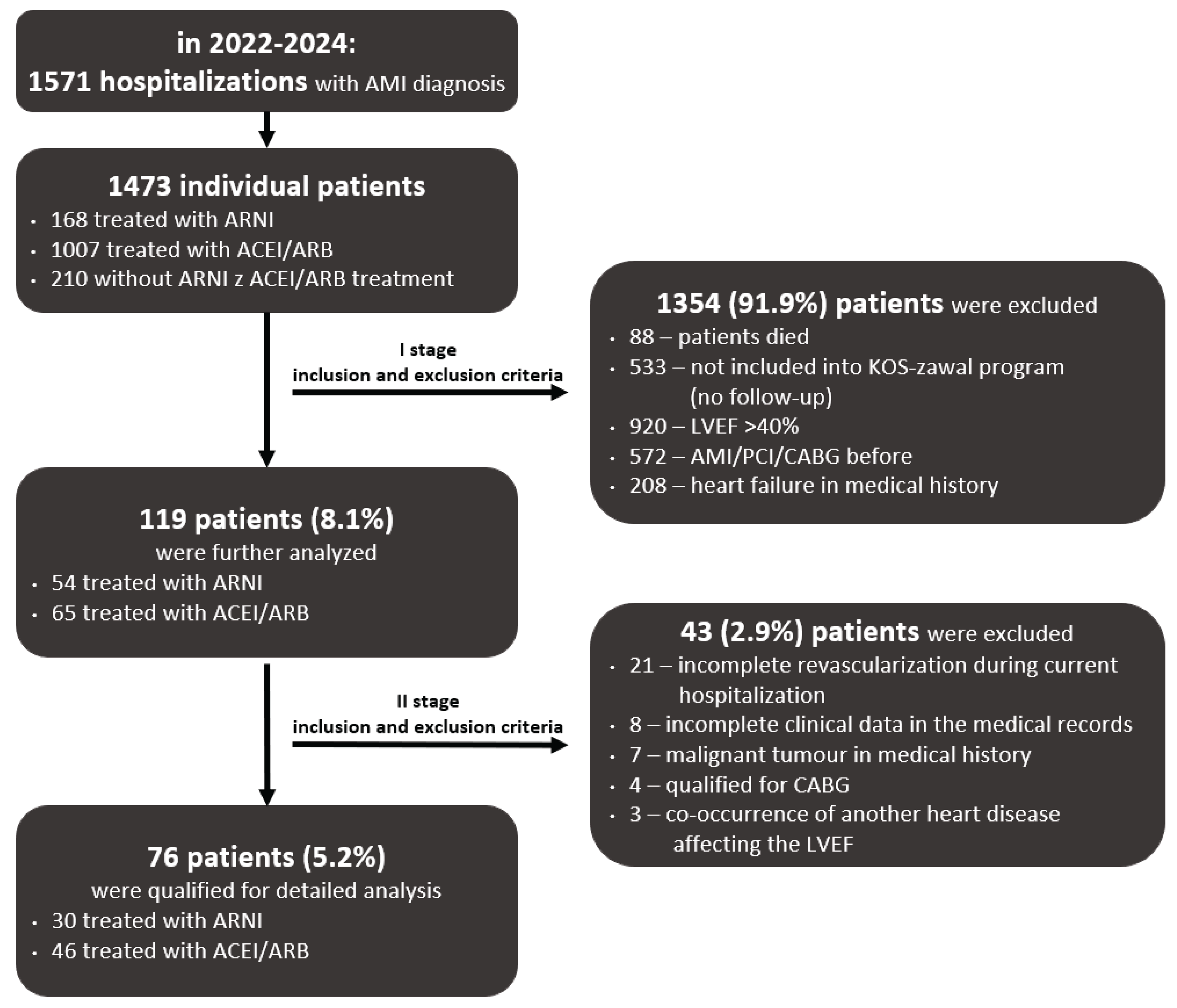

3.1. Study Population, Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

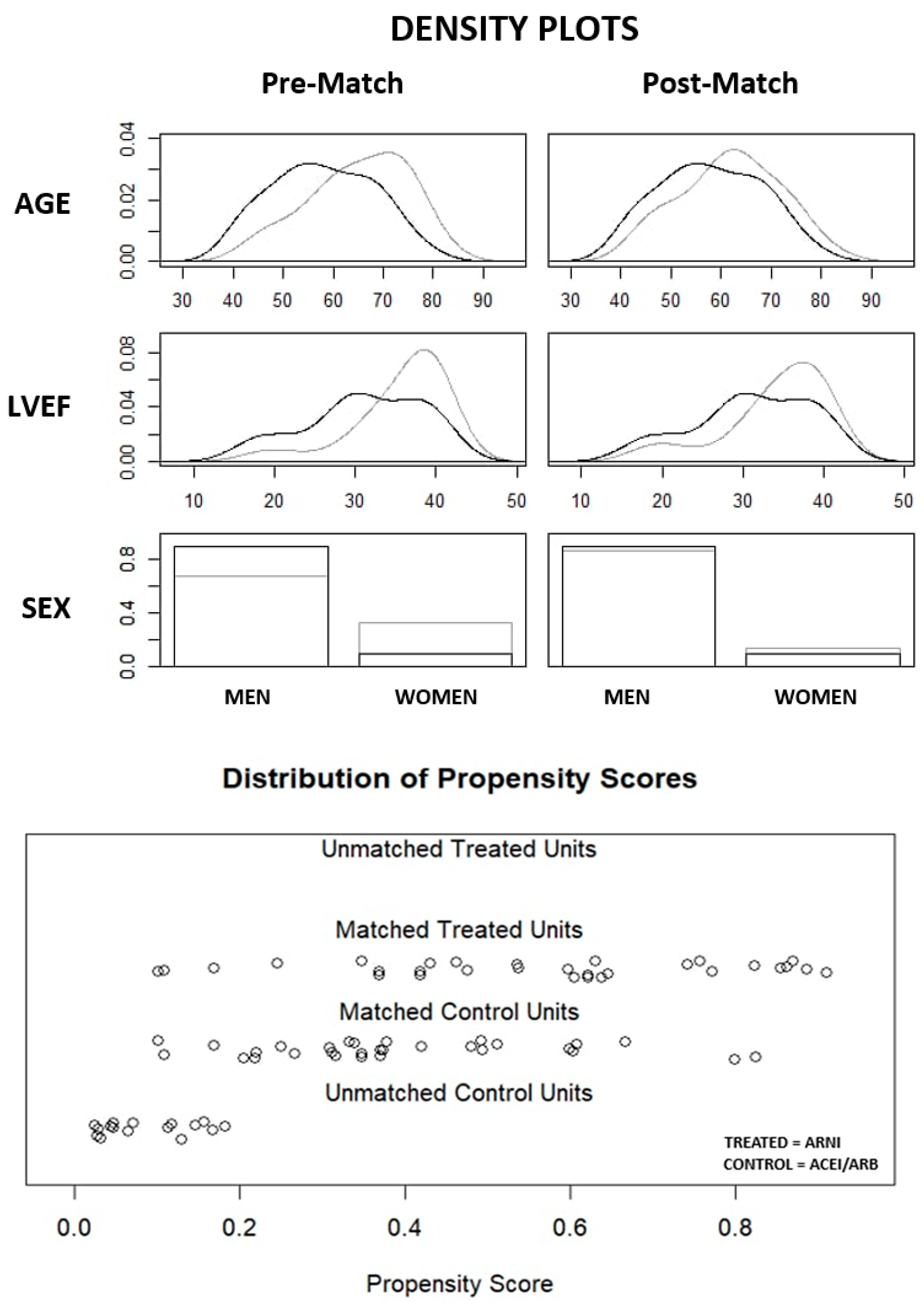

3.2. Matching Results

3.3. Comparison of Baseline Characteristics of ARNI and ACEI/ARB Subgroups

|

Factor |

ARNI subgroup n=30 n (%) or mean ± SD or median (1-3 quartile) |

ACEI/ARB subgroup n=30 n (%) or mean ± SD or median (1-3 quartile) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic characteristic | |||

| Age (years) | 58 ± 10 | 62 ± 10 | 0.14 |

| Sex – men (n%) | 27 (90%) | 26 (86.7%) | 0.69 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29 ± 4.5 | 28.7 ± 4.2 | 0.8 |

| Type of myocardial infarction | |||

| STEMI (n%) | 24 (80%) | 23 (76.7%) | 0.756 |

| Anterior wall (n%) | 17 (56.7%) | 13 (43.3%) | - |

| Inferior wall (n%) | 4 (13.3%) | 6 (20%) | - |

| Anterior and lateral wall (n%) | 3 (10%) | 3 (10%) | - |

| Inferior and lateral wall (n%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.3%) | - |

| NSTEMI (n%) | 6 (20%) | 7 (23.3%) | 0.756 |

| Laboratory tests | |||

| Serum creatinine level (mg/dl) | 0.83 (0.75; 1.03) | 1.0 ± 0.25 | 0.1 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73) | 66.5 ± 12.8 | 67.8 ± 14.98 | 0.819 |

| eGFR <60 (ml/min/1.73) | 2 (6.7%) | 5 (16.7%) | 0.232 |

| Troponin max. level (ng/ml) | 3.46 (0.64; 5.12) | 1.03 (0.15; 3.48) | 0.085 |

| Hemoglobin level (g/dl) | 14.71 ± 1.33 | 14.86 ± 1.55 | 0.681 |

| Echocardiographic parameters | |||

| LVEF (%) | 30 (28; 38) | 36 (33; 39) | 0.076 |

| LVEDD (mm) | 52 (50; 59) | 53.18 ± 6.85 | 0.212 |

| LVESD (mm) | 40.12 ± 10.38 | 37.25 ± 7.8 | 0.257 |

| LVIVSd (mm) | 11.27 ± 1.71 | 12.1 ± 1.8 | 0.085 |

| LVPWd (mm) | 9.61 ± 1.47 | 10 (9; 11) | 0.204 |

| LAarea (cm2) | 21.86 ± 6.69 | 22.1 ± 4.57 | 0.927 |

| LAwidth (mm) | 40.72 ± 5.8 | 40 (38; 44.5) | 0.67 |

| Mitral regurgitation (II or III) (n%) | 3 (10%) | 2 (6.7%) | 1.0 |

| Tricuspid regurgitation (II or III) (n%) | 4 (13.3%) | 1 (3.3%) | 0.353 |

| Aortic regurgitation (n%) | 0 0 (%) | 2 (6.7%) | 0.492 |

| Aortic stenosis (n%) | 0 0 (%) | 1 (3.3%) | 1.0 |

| Concomitant diseases | |||

| Atrial fibrillation (n%) | 6 (20%) | 7 (23.3%) | 0.756 |

| Chronic kidney disease (n%) | 1 (3.3%) | 2 (6.7%) | 1.0 |

| Hypertension (n%) | 21 (70%) | 23 (76.7%) | 0.563 |

| Diabetes (n%) | 6 (20%) | 12 (40%) | 0.093 |

| Lipid disorders (n%) | 23 (76.7%) | 25 (83.3%) | 0.522 |

| Smoke history (n%) | 18 (60%) | 18 (60%) | 1.0 |

| History of stroke (n%) | 0 0 (%) | 1 (3.3%) | 1.0 |

| Asthma (n%) | 0 0 (%) | 2 (6.7%) | 0.492 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (n%) | 1 (3.3%) | 3 (10%) | 0.612 |

| Medicinal treatment | |||

| ARNI (n%) |

24/26 mg – 29 (99.7%) 49/51mg – 1 (0.3%) |

- |

|

| ACEI/ARB (n%) | - | ACEI – 28 (93.3%) ARB – 2 (6.7%) |

|

| SGLT-2 inhibitor (n%) | 21 (70%) | 11 (36.7%) | 0.01 |

| Beta-blocker (n%) | 28 (93.3%) | 25 (83.3%) | 0.232 |

| Mineralocorticoid-receptor antagonist (n%) | 26 (86.7%) | 21 (70%) | 0.12 |

| Loop diuretic (n%) | 15 (50%) | 8 (26.7%) | 0.065 |

| Calcium channel blockers (n%) | 1 (3.3%) | 5 (16.7%) | 0.195 |

| Statin (n%) | 30 (100%) | 30 (100%) | 1.0 |

| Ezetimibe (n%) | 11 (36.7%) | 7 (23.3%) | 0.264 |

| Fibrate (n%) | 0 (%) | 2 (6.7%) | 0.492 |

| GLP-1 receptor agonists (n%) | 1 (3.3%) | 2 (6.7%) | 1.0 |

| Metformin (n%) | 2 (6.7%) | 8 (26.7%) | 0.08 |

| Sulfonylureas (n%) | 0 (%) | 4 (13.3%) | 0.112 |

| Insulin (n%) | 1 (3.3%) | 1 (3.3%) | 1.0 |

| Acetylsalicylic acid (n%) | 30 (100%) | 30 (100%) | 1.0 |

| P2Y12 inhibitors (n%) | 30 (100%) | 30 (100%) | 1.0 |

| NOAC (n%) | 6 (20%) | 7 (23.3%) | 0.756 |

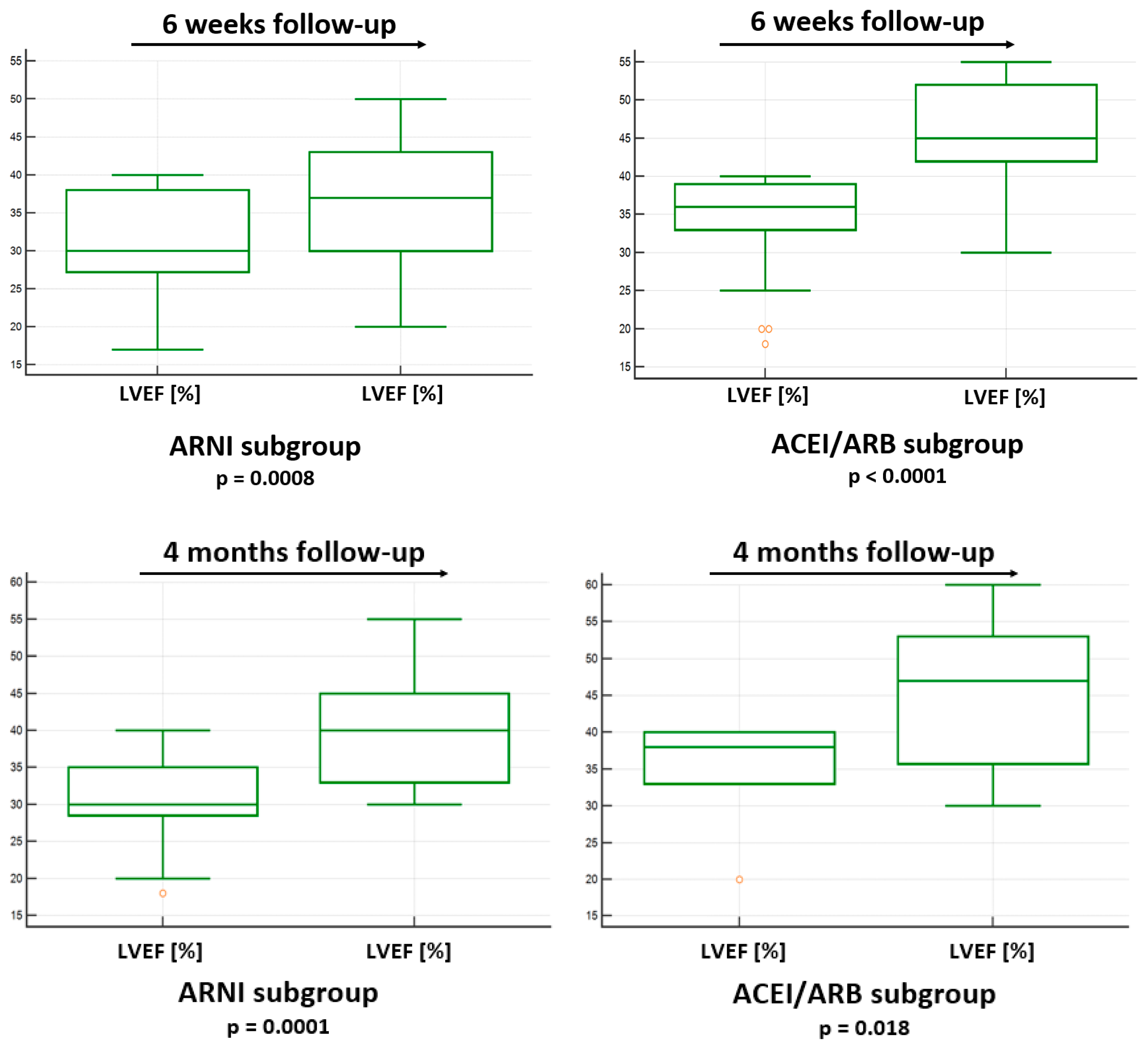

3.4. LVEF Improvement in 6 Weeks Follow-Up in ARNI and ACEI/ARB Subgroups

3.5. LVEF Improvement in 4 Months Follow-Up in ARNI and ACEI/ARB Subgroups

| Subgroup | baselineLVEF (%) median (1-3 quartile) |

LVEF (%) in 6 weeks median (1-3 quartile) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ARNI n=29 | 30 (27.3; 38) | 37 (30; 43) | 0.0008 |

| ACEI/ARB n=30 | 36 (33; 39) | 45 (42; 52) | <0.0001 |

| Factor | ARNI subgroup n=29 median (1-3 quartile) |

ACEI/ARB subgroup n=30 median (1-3 quartile) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| baseline LVEF (%) | 30 (27.3; 38) | 36 (33; 39) | 0.072 |

| LVEF (%) in 6 weeks | 37 (30; 43) | 45 (42; 52) | 0.003 |

| ΔLVEF (%) | 6 (2; 10.25) | 10 (6; 12) | 0.018 |

| relative ΔLVEF (%) | 17.5 (7; 31.9) | 30 (15.4; 40) | 0.047 |

| Subgroup | baselineLVEF (%) n (%) or mean ± SD |

LVEF (%) in 6 weeks n (%) or mean ± SD |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ARNI n=20 | 30.5 ± 5.9 | 40.2 ± 7.8 | 0.0001 |

| ACEI/ARB n=7 | 34.9 ± 7.3 | 44.6 ± 10.9 | 0.0313 |

|

Factor |

ARNI subgroup n=20 n (%) or mean ± SD |

ACEI/ARB subgroup n=7 n (%) or mean ± SD |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| baseline LVEF (%) | 30.5 ± 5.9 | 34.85 ± 7.27 | 0.073 |

| LVEF (%) in 4-months | 40.2 ± 7.7 | 44.6 ± 10.9 | 0.025 |

| ΔLVEF (%) | 9.65 ± 8.6 | 9.71 ± 8.01 | 0.986 |

| relative ΔLVEF (%) | 35.6 ± 34.07 | 30.11 ±27.8 | 0.705 |

3.6. Clinical Outcomes in ARNI and ACEI/ARB Subgroups

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations:

| 6-WMT | 6-minute walk test |

| ACS | acute coronary syndrome |

| AMI | acute myocardial infarction |

| ARNI | angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor |

| CABG | coronary artery bypass grafting |

| CAD | coronary artery disease |

| DCM | dilated cardiomyopathy |

| ESC | European Society of Cardiology |

| HF | heart failure |

| HFrEF | heart failure with reduced ejection fraction |

| LAV | left atrial volume |

| LVEF | left ventricular ejection fraction |

| MACE | major adverse cardiovascular events |

| MACCE | major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events |

| MI | myocardial infarction |

| MR | mitral regurgitation |

| MRA | mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist |

| NN | nearest neighbour |

| RAAS | renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system |

| SGLT-2 inhibitors | sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors |

| STEMI | ST-elevation myocardial infarction |

References

- McMurray, J.J.; Packer, M.; Desai, A.S.; et al. PARADIGM-HF Investigators and Committees. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2014, 371, 993–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2023 Focused Update of the 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart, J. 2023, 44, 3627–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, M.A.; Claggett, B.; Lewis, E.F.; et al. PARADISE-MI Investigators and Committees. Angiotensin Receptor-Neprilysin Inhibition in Acute Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2021, 385, 1845–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.M.; Claggett, B.; Prasad, N.; et al. Impact of Sacubitril/Valsartan Compared With Ramipril on Cardiac Structure and Function After Acute Myocardial Infarction: The PARADISE-MI Echocardiographic Substudy. Circulation. 2022, 146, 1067–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, R.A.; Rossello, X.; Coughlan, J.J.; et al. ESCScientific Document Group. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart, J. 2023, 44, 3720–3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Falguera, D.; Aranyó, J.; Teis, A.; et al. Antiarrhythmic and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Sacubitril/Valsartan on Post-Myocardial Infarction Scar. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2024, 17, e012517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, J.; Wang, Y.; Deng, Y.; et al. Sacubitril/valsartan ameliorates cardiac function and ventricular remodeling in CHF rats via the inhibition of the tryptophan/kynurenine metabolism and inflammation. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 12377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, N.; Qiu, Y.; Zhang, K.; et al. Sacubitril/valsartan alleviates myocardial infarction-induced inflammation in mice by promoting M2 macrophage polarisation via regulation of PI3K/Akt pathway. Acta Cardiol. 2024, 79, 768–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Fan, Z.; Sun, G.; et al. Sacubitril/valsartan (LCZ696) reduces myocardial injury following myocardial infarction by inhibiting NLRP3-induced pyroptosis via the TAK1/JNK signaling pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2021, 24, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, P.C.; Wo, H.T.; Lee, H.L.; et al. Sacubitril/Valsartan Therapy Ameliorates Ventricular Tachyarrhythmia Inducibility in a Rabbit Myocardial Infarction Model. J Card Fail. 2020, 26, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Guo, Y.; Wu, Y.; et al. Protective Effects of Sacubitril/Valsartan on Cardiac Fibrosis and Function in Rats With Experimental Myocardial Infarction Involves Inhibition of Collagen Synthesis by Myocardial Fibroblasts Through Downregulating TGF-β1/Smads Pathway. Front Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 696472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, C.; et al. Lcz696 Alleviates Myocardial Fibrosis After Myocardial Infarction Through the sFRP-1/Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway. Front Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 724147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, J.; et al. Early Application of Sacubitril Valsartan Sodium After Acute Myocardial Infarction and its Influence on Ventricular Remodeling and TGF-β1/Smad3 Signaling Pathway. Altern Ther Health Med. 2024, 30, 98–103. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Su, Y.; Shen, J.; et al. Improved heart function and cardiac remodelling following sacubitril/valsartan in acute coronary syndrome with HF. ESC Heart Fail. 2024, 11, 937–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. Effect of Emergency Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Combined with Sacubitril and Valsartan on the Cardiac Prognosis in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction. Int J Gen Med. 2023, 16, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Ma, L.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Efficacy of early administration of sacubitril/valsartan after coronary artery revascularization in patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by moderate-to-severe mitral regurgitation: a randomized controlled trial. Heart Vessels. 2024, 39, 673–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezq, A.; Saad, M.; El Nozahi, M. Sacubitril/valsartan versus ramipril in patients with ST-segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction and cardiogenic SHOCK (SAVE-SHOCK): a pilot randomized controlled trial. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2021, 11, 734–742. [Google Scholar]

- Rezq, A.; Saad, M.; El Nozahi, M. Comparison of the Efficacy and Safety of Sacubitril/Valsartan versus Ramipril in Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2021, 143, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurray, J.V.; Solomon, S.D.; Inzucchi, S.E.; et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019, 381, 1995–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, M.; Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with empagliflozin in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2020, 383, 1414–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; et al. Empagliflozin in heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2021, 385, 1451–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.D.; McMurray, J.V.; Claggett, B.; et al. Dapagliflozin in heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2022, 387, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J.; Jones, W.S.; Udell, J.A.; et al. Empagliflozin after Acute Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2024, 390, 1455–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Lewinski, D.; Kolesnik, E.; Tripolt, N.J.; et al. Empagliflozin in acute myocardial infarction: the EMMY trial. Eur Heart J. 2022, 43, 4421–4432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Januzzi, J.J.; Prescott, M.F.; Butler, J.; et al. PROVE-HF Investigators Association. of Change in N-Terminal Pro-B-Type Natriuretic Peptide Following Initiation of Sacubitril-Valsartan Treatment With Cardiac Structure Function in Patients With Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. J.A.M.A. 2019, 322, 1085–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, A.S.; Solomon, S.D.; Shah, A.M.; et al. EVALUATE-HF Investigators Effect of Sacubitril-Valsartan vs Enalapril on Aortic Stiffness in Patients With Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. A.M.A. 2019, 322, 1077–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.M.; Kim, K.H.; Park, J.S.; et al. Beneficial Effect of Left Ventricular Remodeling after Early Change of Sacubitril/Valsartan in Patients with Nonischemic Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021, 57, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Dai, W. Effect of sacubitril-valsartan on left ventricular remodeling in patients with acute myocardial infarction after primary percutaneous coronary intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1366035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhu, H.; Zheng, Y.; et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of sacubitril-valsartan in the treatment of ventricular remodeling in patients with heart failure after acute myocardial infarction. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022, 9, 953948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Li, C.; Zhang, X. Sacubitril/valsartan improves the prognosis of acute myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis. Coron Artery Dis. 2024, 35, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- –, A.; Rashid, M.; Soto, C.J.; et al. The Safety and Efficacy of the Early Use of Sacubitril/Valsartan After Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Cureus. 2024, 16, e53784. [Google Scholar]

- She, J.; Lou, B.; Liu, H.; et al. ARNI versus ACEI/ARB in Reducing Cardiovascular Outcomes after Myocardial Infarction. ESC Heart Fail. 2021, 8, 4607–4616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Age ≥ 18 years | 1) A history of previous myocardial infarction or coronary revascularization |

| First diagnosis of MI | 2) A history of HF or angioedema |

| Percutaneous revascularization of the infarct-related coronary artery and complete revascularization during current hospitalization | 3) Co-occurrence of another heart disease affecting the left ventricular ejection fraction |

| Post-infarction left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVEF ≤ 40%) | 4) Severe hepatic or renal dysfunction |

| Patients enrolled into coordinated specialist care after a MI (‘’KOS zawał’’ program) | 5) Coexisting severe diseases of the immune, hematopoietic, or respiratory systems, or systemic diseases |

| Presence of a malignant tumour | |

| Death of a patient during hospitalization | |

| Incomplete clinical data in the medical records |

|

Variable |

Pre-Match n (%) or mean ± SD or median (1-3 quartile) |

Post-Match n (%) or mean ± SD or median (1-3 quartile) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARNI subgroup n = 30 |

ACEI/ARB subgroup n = 46 |

Std. Mean Diff. |

ARNI subgroup n = 30 |

ACEI/ARB subgroup n = 30 |

Std. Mean Diff. |

|

| Age (years) | 58 ± 10 | 65 ± 10 | 0.708 | 58 ± 10 | 62 ± 10 | 0.388 |

| Men (%) | 27 (90%) | 31 (67.4%) | 0.567 | 27 (90%) | 26 (86.7%) | 0.102 |

| LVEF (%) | 30 (28;38) | 38 (33;40) | 0.704 | 30 (28;38) | 36 (33;39) | 0.451 |

|

Clinical outcome |

ARNI subgroup n=30 n (%) or mean ± SD or median (1-3 quartile) |

ACEI/ARB subgroup n=30 n (%) or mean ± SD or median (1-3 quartile) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deaths (n%) | 1 (3.3%) | 2 (6.7%) | 1.0 |

| Number of rehospitalizations (n%) | 0 | 3 (10%) | 0.24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).