1. Introduction

Depression and anxiety disorders are among the most common mental health illnesses: around 3–4% of the world’s population suffers from each at any given time [

1] and together they are responsible for 8% of years lived with disability globally [

2]. Mental disorders can have significant negative impacts on socioeconomic outcomes, such as employment and productivity [

3,

4]. These impacts are likely even stronger in fragile, and conflict affected parts of the world, particularly among populations exposed to collective violence and forced displacement. Conflict and displacement can adversely impact mental health and psychosocial well-being [

5,

6]. Exposure to stressful and potentially traumatic events and multiple interpersonal losses greatly increases the risk of developing mental disorders such as depression, anxiety disorders and post-traumatic stress [

7]. Increased rates of mental health conditions among refugees are also fuelled by post-forced displacement conditions such as poor socioeconomic conditions, lack of basic rights (such as the rights to work, open bank accounts, register for a mobile phone), lack of legal documentation, difficulty to get jobs or access to higher education, as well as separation from family and supportive community [

2,

8,

9,

10].

One in five persons living in conflict affected areas are estimated to suffer from mental health conditions, such as depression, anxiety and/or psychosis and one in ten displaced individuals are living with moderate or severe forms of such mental health conditions [

7]. Recent evidence indicates that depression rates among refugees rose more significantly than those of host populations during the COVID-19 pandemic [

11]. Surveys in Uganda found that 50% of refugees reported experiencing depression symptoms during the pandemic vs. 5% of nationals [

8]. This highlights the urgent need for better tracking of mental health statistics among displaced populations and hosts, especially in times of shocks [

7].

A growing literature has documented how poverty is also associated with mental health, though limited evidence exists for refugee and host communities on the interaction between poverty and mental health. Within a given location, those with the lowest incomes are typically 1.5 to 3 times more likely to experience depression or anxiety compared to those who are better off [

12,

13]. Rates of depression, anxiety, and suicide correlate negatively with income [

12,

13,

14,

15] and employment [

16,

17]. Although comparable poverty data are scarce, available evidence shows that refugee populations generally experience higher poverty rates than nationals, regardless of the policy environment [

18]. This can be especially salient where refugees lack freedom of movement and are relegated to camps. In such situations, refugees tend to be concentrated in poorer areas where locals are disproportionately poor compared to the national average.

Recent findings on poverty within refugee households and groups underscore the need for further research to comprehend the heterogeneous poverty outcomes among refugees. A recent report tracking refugee poverty in Jordan where refugees have the choice to live either in camps or out of camps amongst host communities finds that those who live in camps are less likely to be poor (42%) than those who choose to live out of camp (62%) [

19]. Given some 80% of the refugee population in Jordan live outside of camps the authors posit that freedom may be an overlooked dimension of welfare in refugee settings. Recent evidence indicates that within households in Kenya and Uganda, poverty is not equally distributed among all members. Refugee children are up to three times more likely to experience poverty compared to adults. [

20]. This evidence highlights the need for further research to understand the diverse nature of poverty among refugee groups, which will aid in effectively targeting assistance to the most vulnerable.

Having a disability is a high-risk factor for developing mental health conditions, including depression or anxiety [

21,

22]. According to the WHO, disability arises from the interaction between individuals with health conditions and various personal and environmental factors, such as negative attitudes, inaccessible transportation and public buildings, and limited social support. The existing literature also highlights that individuals with physical disabilities have higher rates of depression and poor mental health outcomes, particularly women [

23,

24]. A U.S. study finds adults with disabilities report experiencing mental distress almost five times as often as adults without disabilities [

25]. There is limited evidence on the incidence of disability among refugees and its correlation with mental health and poverty. Additionally, comparative data on disability between refugees and host communities in the same setting is scarce. The evidence that does exist, suggests that refugees tend to have higher burdens of disabilities than host communities [

26,

27] and can face more difficulties in accessing services due to their limited rights in a country of asylum and/or relative levels of poverty (and diminished ability to pay for health services) compared to host community.

We also innovate by looking at different measures including loneliness and pessimistic life views to see how they correlate with depression, anxiety, disability and financial security. “Loneliness has been characterized as an epidemic in modern society, impacting one-third of individuals in developed countries [

28]. It is defined as an ‘unpleasant experience that arises when a person’s social network is deficient in some significant way, either quantitatively or qualitatively [

29].’ Research indicates that loneliness tends to be more prevalent and intense among individuals with severe mental illness [

30]. Personality has been identified as a significant predictor of depressive symptoms [

31,

32,

33]. In particular, dispositional optimism and pessimism are noted as key predictors of depression risk in numerous studies [

34,

35,

36,

37], as these traits are closely linked to the absence of positive emotions, a core symptom of depression [

38]. Limited work to date has evaluated additional measures associated with mental health, such as loneliness and pessimistic life views, in low-income settings. This study adds to the literature by looking at a forced displacement context for impoverished refugees and hosts in Mozambique and is one of the first studies to assess how loneliness and pessimism bias correlates with mental health and disability outcomes.

More broadly, understanding the levels of mental health outcomes among poor refugees and host communities and how mental health relates to poverty and disability is critical to inform evidence-based (and differentiated) programming as needed. This paper examines the causal relationship across measures of mental health, disability, loneliness, pessimism bias and financial security (a proxy for welfare) among the poorest segments of both refugees and host communities in in a forced displaced setting in Mozambique. This paper offers a pioneering exploration into the interconnectedness of mental health, disability, and financial security (used as a welfare indicator) among the most impoverished groups within both refugee and host communities in Mozambique. By focusing on these specific populations, the study provides unique insights into the compounded challenges faced by the poorest segments of forcibly displaced populations, which have been underrepresented in existing literature. The findings are expected to significantly contribute to the academic discourse by highlighting the intricate causal relationships between these critical factors, thereby informing more effective policy interventions and support mechanisms for vulnerable populations in similar settings.

Poverty and Displacement in Mozambique

The World Bank estimates that 63% of the population in Mozambique are living in poverty. Mozambique’s protracted civil war (1977−1992) forced more than a third of the population at the time—more than four million civilians of the then 12 million total population—to flee to the countryside, to cities, and to refugee camps and settlements in neighbouring countries, leaving long-lasting socio-economic impacts on society. A recent study revealed that individuals displaced to cities, smaller towns, or rural settlements invested significantly more in education compared to children who stayed in the countryside or were displaced to refugee camps in neighbouring countries. At the same time, those who were displaced exhibited significantly lower social capital and worse mental health, even three decades after the war ended. These findings suggest that displacement shocks in Mozambique triggered positive human capital investments, breaking links with subsistence agriculture, but also caused long-lasting, social, and psychological consequences [

39].

Mozambique hosts over 24,000 refugees as of end January 2025 [

40]. Long asylum procedures and generalized rural poverty have posed formidable obstacles to socioeconomic integration. The Maratane refugee settlement is in one of the most populous provinces in Mozambique. The site has evolved from a traditional refugee camp into a more open settlement, reflecting the Mozambican government’s policy shift towards promoting local integration and sustainable solutions. The Maratane Refugee Settlement is home to about 13,190 refugees and asylum seekers, primarily from the Democratic Republic of Congo, Burundi, Rwanda, and Somalia. About 16,390 Mozambican nationals from the surrounding community directly depend on the settlement for services (e.g., health, education, etc.) provided by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), NGO partners and the government. Many Mozambican nationals (99%) living near the settlement are Makua (or Makhua), a Bantu-speaking ethnic group. The Makua live in an extensive area that covers the northern parts of Mozambique and includes the Cabo Delgado, Niassa, Zambézia and Nampula provinces. Their traditional livelihoods are based on small-scale subsistence farming.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Aims

We obtained measures of depression and anxiety, pessimistic life views and loneliness, socio-economic outcomes and disability for both refugees and host communities in a low-income setting, and among the poorest segments of the population. This allows us to help build an evidence base on comparable mental health and socio-economic outcomes for ultra-poor refugees and hosts.

2.2. Survey Data

The data are drawn from a set of surveys covering a range of thematic areas such as housing characteristics, employment and livelihood, education, finance and assets, health, social capital, social norms, consumption expenditure and food security. These surveys was part of a wider impact evaluation of the Graduation Programme [

41] targeting poor refugees and host community members living in and around Maratane Settlement [

42]. The graduation programme in Maratane, includes assistance in the following areas: consumption support, instructions on resume-writing, core skills training, language and financial literacy classes, market-oriented skills and vocational training, job support, asset transfer and coaching services to provide encouragement and improve self-esteem as well as personalize interventions to individual needs. The programme also includes support for self or wage employment including a paid apprenticeship to improve linkages to jobs so that participants with limited experience could increase their employability. All measures included in this study were taken prior to the main intervention associated with a large cash transfer and employment support that was provided in August 2021 [

42].

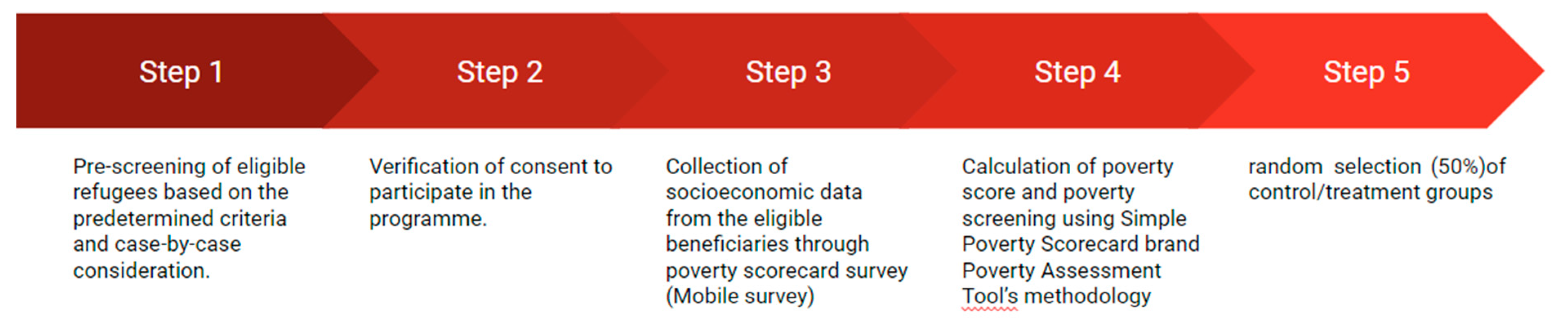

The selection of ultra-poor households was designed based on a poverty score card employed by the World Bank for the targeting of Government social protection programs. The selection of refugee beneficiaries followed five key steps summarized in

Figure 1, namely: 1) pre-screening of eligible refugees to identify those who were not engaged in regular employment, 2) verification of consent to participate in the programme, 3) collection of socioeconomic data through a poverty scorecard survey which contained basic questions about their family, language skills, housing and household assets, 4) calculation of poverty score and poverty screening, and 5) random selection (50%) of control/treatment groups. Refugees and Mozambicans who reported an interest in participating in the program and met the basic pre-screening criteria were administered a questionnaire that used 10 indicators to identify ultra-poor households. The poverty scorecard was based on the Government of Mozambique’s Simple Poverty Scorecard [

43]. Annex 1 provides more details on the questionnaire and scoring approach. In total, 448 individuals (18 years and older) were selected with 134 being refugees and 314 belonging to the Mozambican host community. In addition, of the 448 some 166 were randomly selected to participate in the graduation programme while 282 remained in the control group. Because the survey wave which we exploit for this paper took place prior to the main intervention, we utilize the 448 sample to generate the descriptive results outlined in this paper.

2.3. Enumerator Training and Procedure

Two surveys were employed for this analysis. The baseline survey was conducted from Sept-December 2019 while the first follow-up survey- Wave 2- took place from May to July 2021. Both surveys took place in person and prior to the main component of the project- the large unconditional cash intervention.

The questionnaire was designed in both English and Portuguese. Only 44% of refugees and 52% of nationals spoke Portuguese, Mozambique’s national language. The primary languages spoken by refugees include Swahili (96%) and French (53%) while nationals spoke primarily Emakua (99%). For respondents who did not understand English or Portuguese, the questions were asked in Emakua or Swahili by the enumerators during the interview.

The survey was administered by six enumerators who were fluent in Portuguese and either Emakua (three) or Swahili (three). Enumerators were selected based on their proficiency in Makua or Swahili, and on their experience in data collection. All enumerator candidates were subject to a rigorous in-person language proficiency test administered by official translators in each language hired by the project team. Before the start of the data collection, the enumerators underwent an intensive three-day training to ensure that the questionnaire was well-understood and correctly administered. The interviews were done via Computer Assisted Personal Interviewing (CAPI).

2.4. Measures

Depression: symptoms of depression were measured with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), a common self-reported measure for depressive symptoms [

44]. Its nine items ask how often the respondent has been bothered over the last two weeks by: i) little interest or pleasure in doing things; ii) feeling down, depressed or hopeless; iii) trouble falling asleep, staying asleep or sleeping too much; iv) feeling tired or having little energy; v) poor appetite or overeating; vi) feeling bad about yourself—or that you are a failure or have let yourself or your family down; vii) trouble concentrating on things, such as reading the newspaper or watching television; viii) Moving or speaking so slowly that other people could have noticed; or, the opposite—being so fidgety or restless that you have been moving around a lot more than usual; and ix) Thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way. The overall score can range from 0 to 27, with scores of 0–4 indicating no depression, 5–9 = mild depression, 10–14 = moderate depression, 15–19 = moderately severe depression and ≥20 = severe depression. The PHQ-9 has been validated for use in Mozambique [

45] and has been used in research with Mozambican populations [

46,

47].

Anxiety: symptoms of anxiety were measured using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7), a standardized tool screening for anxiety symptoms, in particular generalized anxiety disorder. The seven questions explore how often over the last two weeks the respondent has been bothered by: i) feeling nervous, anxious or on edge; ii) not being able to stop or control worrying; iii) worrying too much about different things; iv) trouble relaxing; v) being so restless that it is hard to sit still; vi) becoming easily annoyed or irritable; vii) feeling afraid as if something awful might happen. The GAD-7 score is calculated by assigning scores of 0, 1, 2, and 3, to the response categories of “not at all,” “several days,” “more than half the days,” and “nearly every day,” respectively. The total score ranges from 0 to 21. The tool has been validated for use in Mozambican populations [

48] and has been used in research in Mozambique [

46,

47] and among Swahili speaking populations in the region [

49,

50]. For this research we use a score of 10 as cut off point for a likely anxiety disorder [

51].

Self-esteem: To measure one’s self-worth we used seven questions from the ten-item Rosenberg Self-Esteem scale [

52]; i) I am able to do things as well as most other people; ii) I feel useless at times; iii) I feel that I am a person of worth, at least on an equal plane with others; iv) I feel that I have a number of good qualities; v) I feel I do not have much to be proud of; vi) I take a positive attitude toward myself, and viii) I am satisfied with my life. This scale measures both positive and negative feelings about oneself, and questions are answered using a 4-point scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Questions that ask about negative feeling about oneself are reversely scored. Scores from each question are then aggregated, with a higher score indicating a higher self-esteem. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale has been very widely used including in Sub-Saharan Africa including in Mozambique and among Swahili speaking populations. To assess the relationship between low self-esteem we examine the prevalence of the lowest quartile and depression and anxiety.

Loneliness: To measure subjective feelings of loneliness, four questions were asked that were drawn from the UCLA loneliness scale [

29]. The questions selected : i) how often do you feel that there is no one you can turn to?; ii) how often do you feel isolated from others? ; iii) how often do you feel that your interests and ideas are not shared by those around you?; and 4) how often do you feel you have a lot in common with the people around you? Questions that ask about negative feeling about loneliness are reversely scored. Scores from each question are then aggregated, with a higher score indicating a higher sense of loneliness. Respondents rated each question on a scale of 0 (Never) to 3 (Often), based on which we generate an adapted total loneliness score from the four questions by summing the numerical values assigned to each of the responses.

Pessimism: We measured value-based questions reflecting pessimism by asking respondents how they rank their life at the time the survey was implemented and how they expect it to be in five years’ time, with 0 being the worst and 10 being the best. Individuals are ranked as being “chronically pessimistic” if they rank their life as a 3 or below both now and in five years’ time.

Disability: We assessed self-reported disability using the Washington Group on Disability Statistics- Short Set on Functioning (WG-SS) consisting of six questions measuring difficulties a person may have in undertaking basic functioning activities including difficulties seeing, hearing, walking or climbing stairs, remembering or concentrating, self-care, and communication (expressive and receptive). Respondents are considered as having a disability if they report ‘having a lot of difficulties’ or ‘cannot do at all’ in at least one of the six questions. The tool is widely used in population surveys including in humanitarian settings [

53].

Financial security: To measure financial security we generated a Financial Security Index which is an index of four proxies for financial security (ease of paying a surprise bill, percent of income saved last month, take home monthly pay, and whether the respondent is employed), constructed by first equally weighting the average z-scores of each indicator that composes each dimension and then averages across the four measures once standardized.

2.5. Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

All data was collected using a Computer Assisted Personal Interviewing (CAPI) using ODK, an open-source mobile data collection platform. Plausibility checks were performed, and data completeness was assured prior to analyses. The presence of missing values did not pose a significant issue. We present the means for each score for refugees and Mozambicans, and for men and women within each population group. We use t-test to test the equality of the means between the population groups and report the statistical significance for the p-values. To determine if refugees and host community members with significant depression or anxiety symptoms are more or less financially secure than those without these conditions, we employ Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression analysis. We regress the likelihood of suffering from Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) or Depression on the financial security index, incorporating socio-demographic control variables such as age, sex, years of education, household size, housing type, Portuguese fluency, and refugee status.

3. Results

3.1. Description of Demographics

Table 1 shows the characteristics of refugees and Mozambicans at the baseline survey. Notably there are statistically significant differences across the refugee and Mozambican communities including that refugees are slightly older with an average age of 39 vs. 36 years of age for hosts, generally have higher levels of schooling than locals while Mozambicans are more likely to be married- 76% vs. 47%.

3.2. Anxiety

We find similar rates of anxiety for both refugees and hosts: one out of four respondents are likely to experience anxiety symptoms. This figure is slightly higher among women than men, but these differences are not statistically significant (

Figure 2). Considering how anxiety varies across age groups, among refugees and hosts, heads of household who are above 54 years are slightly more likely to suffer from anxiety disorder compared to younger heads of households though results not significantly significant.

Source: Mozambique Impact Monitoring First Follow-up Survey (2021); Notes: A non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test of the null hypothesis that for randomly selected values of each population (refugees and hosts), the probability of the value for refugees being greater than the value for Mozambicans is equal to the probability of the value for Mozambicans being greater than the value for refugees yields the following p-values: all comparison between refugees and Mozambicans (p = 1); refugee men vs. Mozambican men (p = 0.96) and refugee female vs. Mozambican female (p = 0.80).

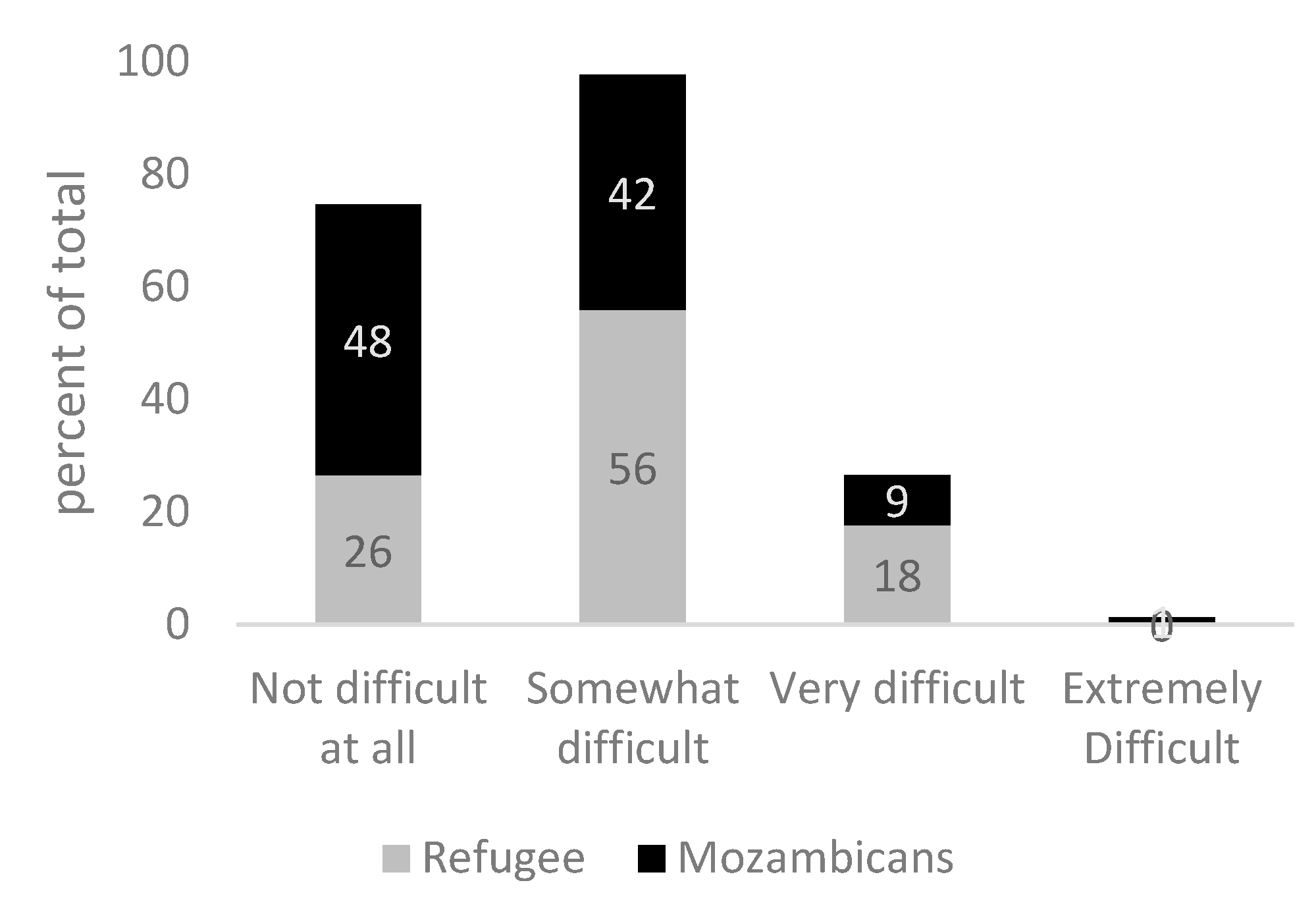

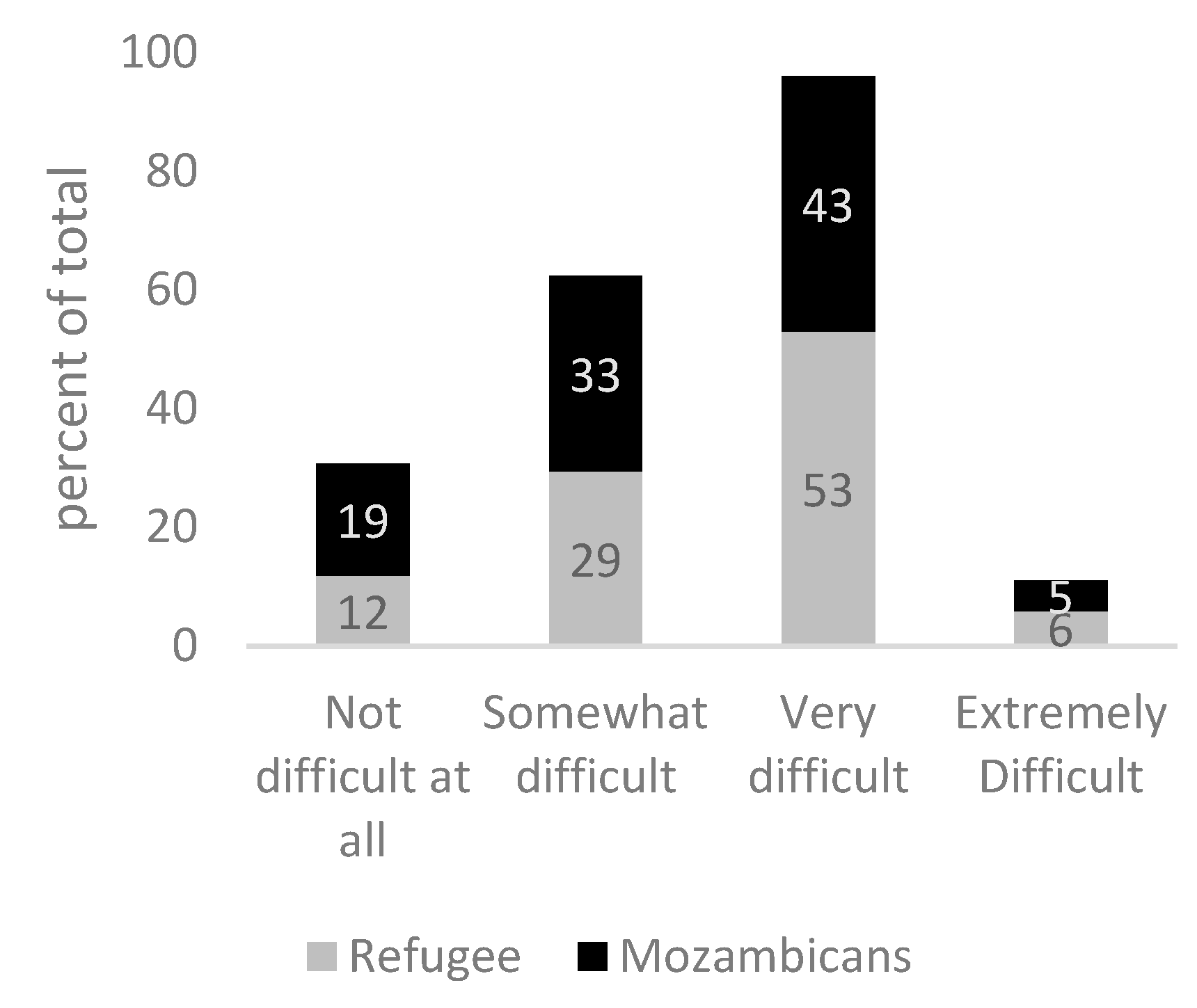

GAD can cause serious distress and interfere with one’s daily functioning such as work, school, social activities and relationships. When asked “how difficult have these problems (related to anxiety) made it for you to do your work, take care of things at home or get along with other people”- 74% of refugees and 52% of Mozambicans who are likely to experience GAD cite this is somewhat to extremely difficult (

Figure 3). When asked “how difficult have these problems (related to anxiety) made it for you to get along with other people,”- 59% of refugees and 48% of Mozambicans report ‘very difficult to extremely difficult’, highlighting the possibility of anxiety underpinning social tension (

Figure 4). There are no statistically significant differences in the across Mozambicans and refugees in the outcomes displayed in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4.

Source: Mozambique Impact Monitoring First Follow-up Survey (2021) Notes: A non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test of the null hypothesis that for randomly selected values of each population (refugees and hosts), the probability of the value for refugees being greater than the value for hosts is equal to the probability of the value for hosts being greater than the value for refugees yields the following p-values: p = 0.71.

Source: Mozambique Impact Monitoring First Follow-up Survey (2021)Notes: A non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test of the null hypothesis that for randomly selected values of each population (refugees and hosts), the probability of the value for refugees being greater than the value for hosts is equal to the probability of the value for hosts being greater than the value for refugees yields the following p-values: p = 0.33

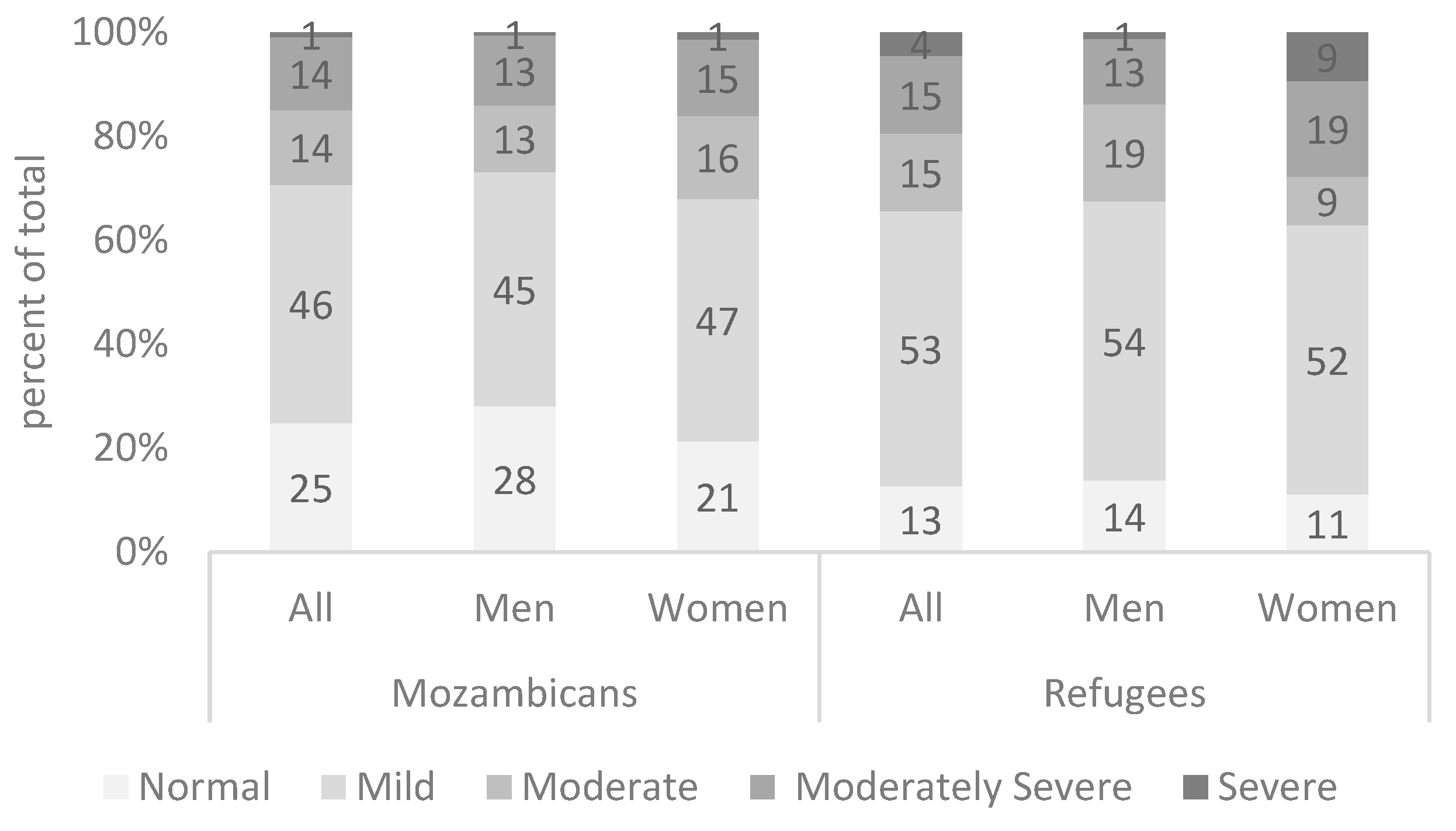

3.3. Depression

Some 34 percent of refugees in the Maratane settlement report experiencing moderate or severe depression disorder, compared to 29 percent hosts (5). A non-parametric test suggests that these differences are significant with refugees exhibiting slightly higher prevalence of symptoms of depression.

Every 28 out of 100 Refugee women suffer from moderately severe (19) or severe depression (9), compared to 14 out of 100 refugee men (p < 0.04). We further find that 53 percent of refugees and 46 percent of Mozambicans suffer from mild depressive episodes.

Figure 5.

Prevalence of symptoms of depression. Source: Mozambique Impact Monitoring First Follow-up Survey (2021) Notes: A non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test of the null hypothesis that for randomly selected values of each population (refugees and hosts), the probability of the value for refugees being greater than the value for hosts is equal to the probability of the value for hosts being greater than the value for refugees yields the following p-values: p = 0.02 (refugee versus hosts), p = 0.06 (men refugee vs. men hosts) and p = 0.08 (women refugee vs. women host).

Figure 5.

Prevalence of symptoms of depression. Source: Mozambique Impact Monitoring First Follow-up Survey (2021) Notes: A non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test of the null hypothesis that for randomly selected values of each population (refugees and hosts), the probability of the value for refugees being greater than the value for hosts is equal to the probability of the value for hosts being greater than the value for refugees yields the following p-values: p = 0.02 (refugee versus hosts), p = 0.06 (men refugee vs. men hosts) and p = 0.08 (women refugee vs. women host).

3.4. Self-Esteem

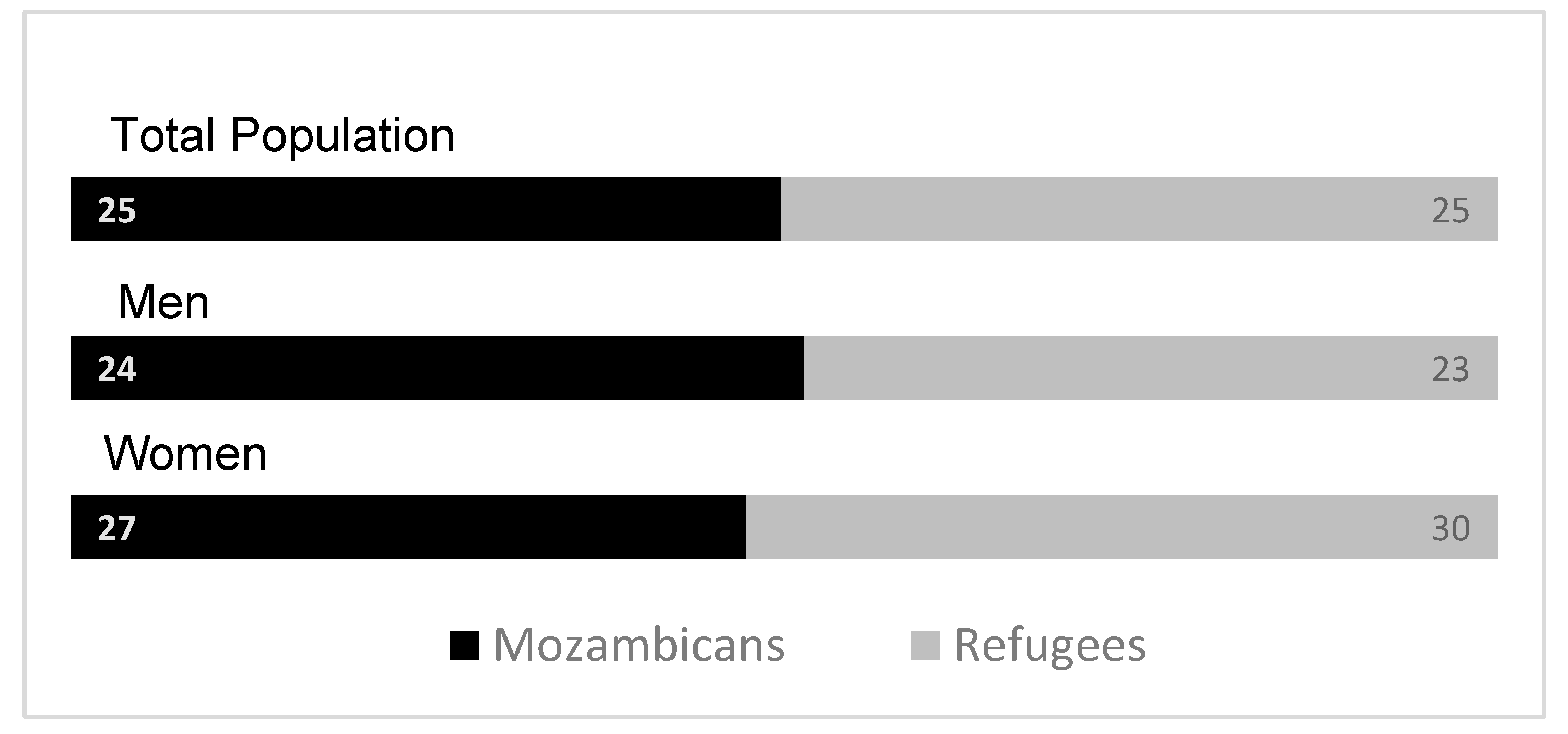

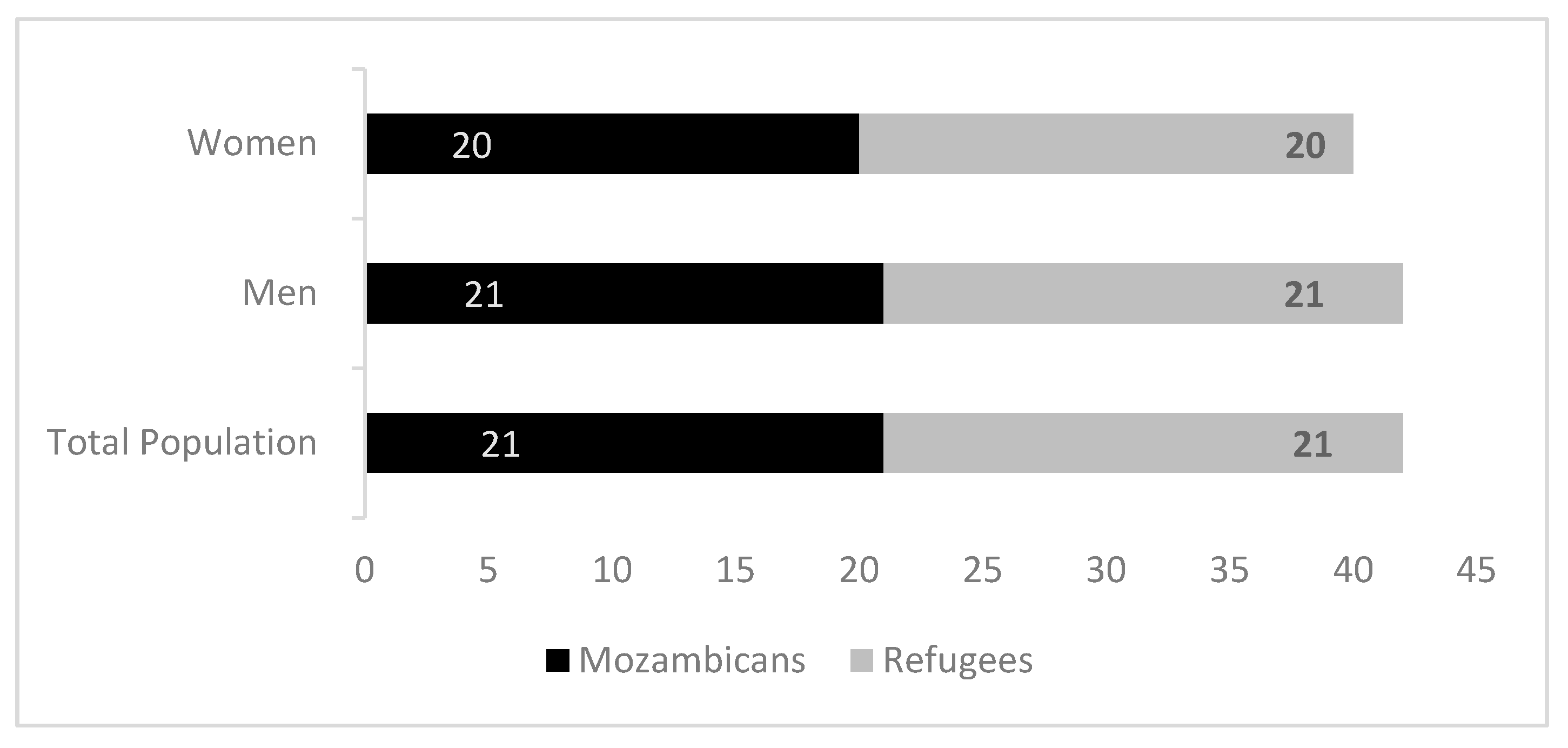

The mean of measure of self-esteem are the same for both refugees and host populations with the mean of 21 for both populations (

Figure 6). There are no statistical differences between men and women. The bottom quartile has a score from 14–19 and the upper quartile from 23–27.

We find that self-esteem is a good predictor of depression and anxiety. Having low self-esteem (bottom quartile of the index) more than doubles the likelihood of the prevalence of Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Depression. Similarly having high self-esteem (upper quartile of the index) lowers the likelihood of the prevalence of Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Depression by a factor of 8 (

Table 2).

3.5. Loneliness

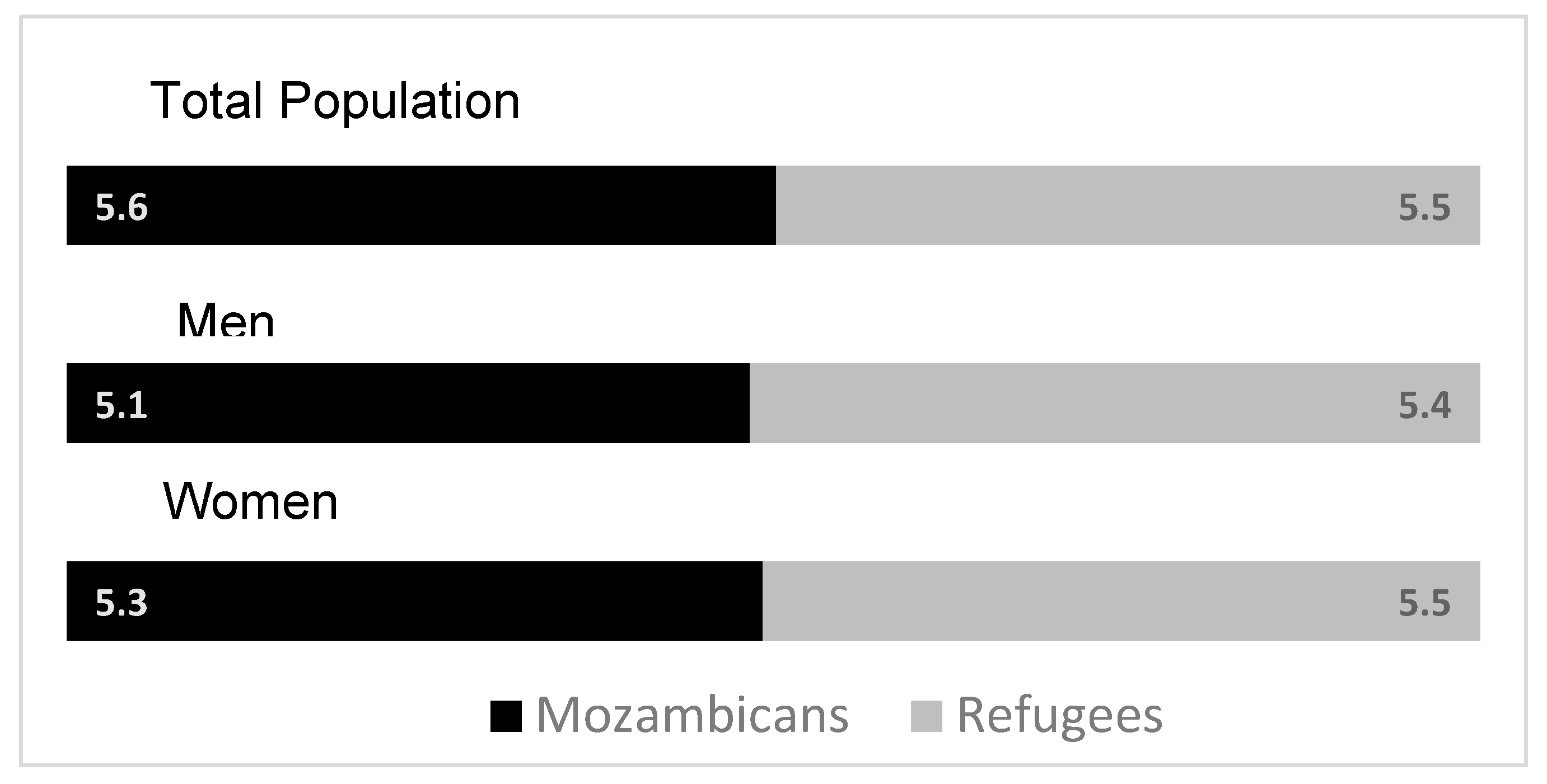

Both refugees and hosts report similar levels of loneliness- 5.6 for Mozambicans and 5.5 out of 10 for refugees (

Figure 7). There are no statistical differences between men and women. The bottom quartile has a score from 1–4.5 and the upper quartile from 7–10.

We find that loneliness is not a good predictor for the prevalence of Generalized Anxiety Disorder or Depression (

Table 3).

3.6. Pessimism Bias

We assess whether pessimistic perceptions of one’s life are correlated with anxiety or depression in the community studied. Some 78% of refugees and 75% of Mozambicans believe their life is a 3 out of 10 or below at present. Some 28% of refugees and 34% of Mozambicans believe that in 5 years their life will be a 3 out of 10 or below.

Source: Mozambique Impact Monitoring First Follow-up Survey (2021); Notes: A non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test of the null hypothesis that for randomly selected values of each population (refugees and hosts), the probability of that value for refugees being greater than the value for hosts is equal to the probability of the value for hosts being greater than the value for refugees yields the following p-values: p = 0.06

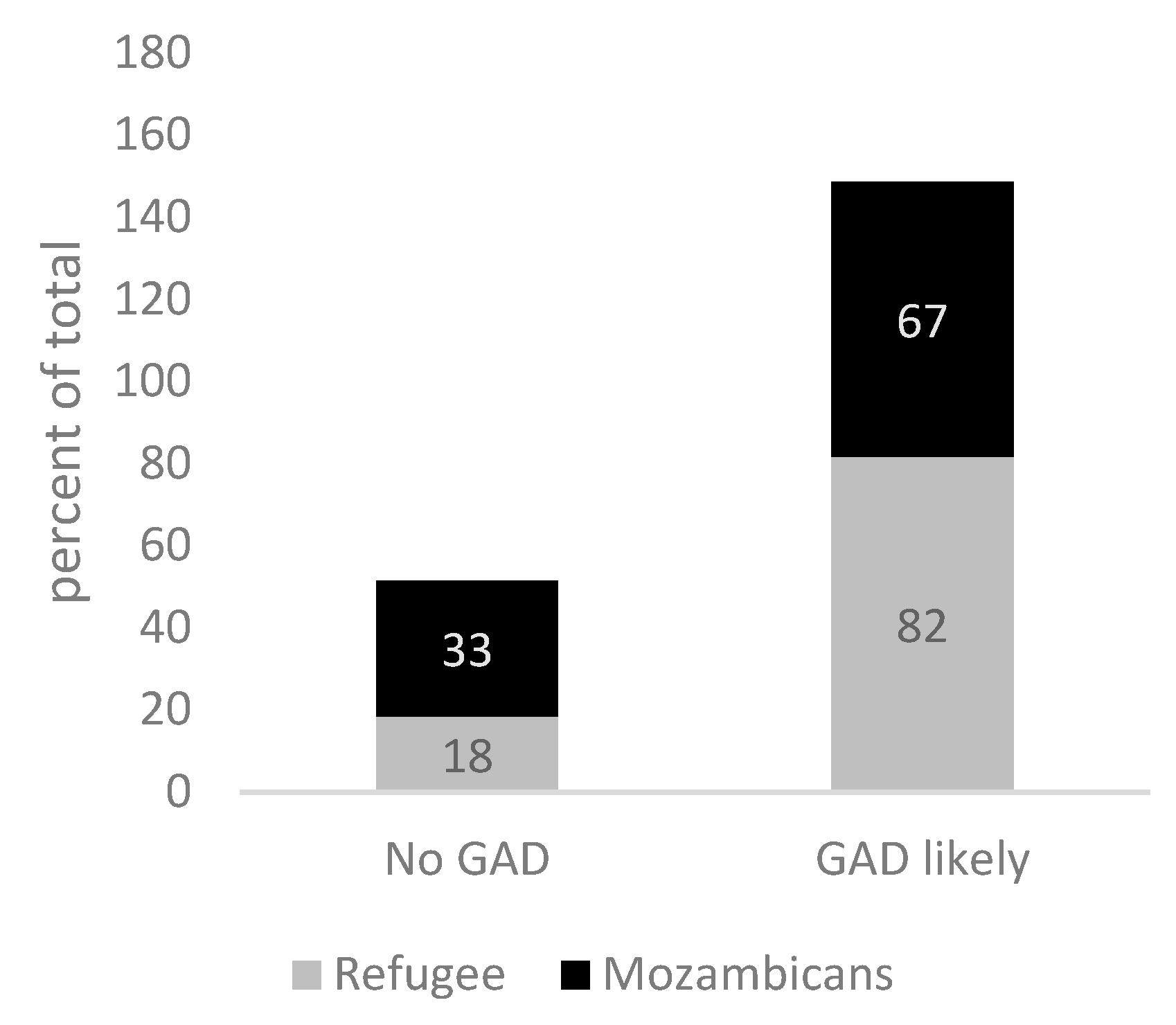

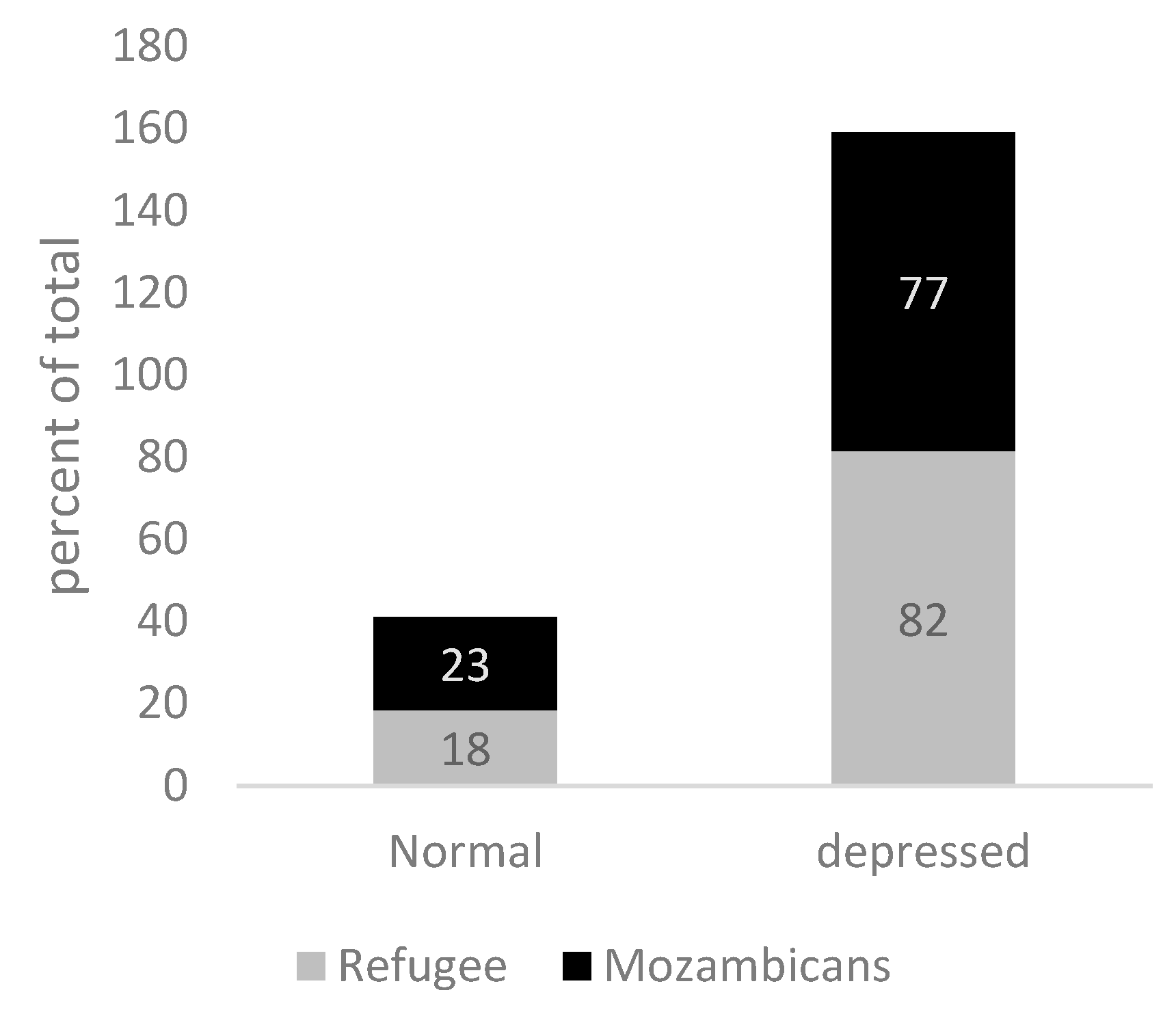

For individuals identified as ‘chronically pessimistic,’ the prevalence of Generalized Anxiety Disorder is 82% among refugees and 67% among Mozambicans (

p < 0.10). The prevalence of Depression is 82% for refugees and 77% for Mozambicans (

p < 0.00), which is more than 2.5 times the population rate (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9).

3.7. Financial Security

To examine whether refugees and host community members who are depressed or anxious are more or less financially secure compared to those who are not, we regress those who score as likely to suffer from Generalized Anxiety Disorder (Depression) on the financial security index alongside socio-demographic control variables (including age, sex, years of education, household size, housing type, whether the individual reports fluency in Portuguese, and if they are a refugee).

Table 4 shows the pooled, refugee and host community results. The pooled sample of refugees and hosts who are classified as anxious are less financially secure at baseline. This result is statistically significant at the 5% level. Similarly, the pooled result for refugees and hosts who are classified as depressed are also relatively more financially insecure at baseline, significant at the 1% level. We find financial security is inversely related to mental health issues: a one-unit increase in financial security corresponds to a 0.069 unit decrease in anxiety (

p < 5%) and a 0.069 unit decrease in depression (

p < 1%). Consistent with our findings above, refugees are more likely to be depressed than hosts and women are more likely overall to be depressed, as are individuals with less education. Notably the results are driven by the host community. Although refugees likely to be depressed exhibit a negative coefficient for the financial security index, it is not significant, nor is it for anxiety.

3.8. Disability

Both refugees and hosts report high levels of disabilities compared to global averages and those suffering from disabilities are more likely to suffer from depression or anxiety. In our sample, 25% of refugees and 22% of Mozambicans report having a disability as measured by the Washington Group on Disability Statistics- Short Set on Functioning (WG-SS). Refugees and Mozambicans with disabilities are more than twice as likely to suffer from depression and three times as likely to suffer from anxiety compared to respondents without disabilities.

4. Discussion

Our results show that levels of depression, anxiety, loneliness, pessimism and disability are both high and relatively similar across refugees and host Mozambicans, though refugees have a higher likelihood of experiencing moderate or severe depression, especially women. Furthermore, the incidence of both depression (over 7 times) and anxiety (over 6 times) is significantly higher than the estimated global average for low- and middle-income countries [

54] and the world population average of 3–4% experiencing either condition at any given time [

12]. Consistent with global evidence, we find that those who suffer from depressive symptoms also experience anxiety symptoms. In our sample, eight out of ten persons with moderate or severe depressive disorder are also likely to be suffering from anxiety disorder, with the figures being slightly higher among women.

A growing literature has established links between exposure to conflict and trauma and poor mental health outcomes. It is well documented in the literature that refugees are exposed to various stress factors which can negatively affect their mental health and well-being during the time of forced displacement including exposure to armed conflict, violence, trauma and persecution as well as after becoming refugees [

55]. Compared to refugees we show that nationals are suffering nearly as high rates of depression, the same level of anxiety, similar levels of loneliness and only moderately lower levels of pessimism as refugees. What could be contributing to the extremely high levels of poor mental health reported among impoverished Mozambicans? One possible factor is the long-term impact of trauma from the Mozambican civil war (1977–1992), compounded by ongoing poverty. There is growing evidence that the effects of exposure to violence and forced displacement can be long (19,35). It is also possible that host community members feel detached from the Mozambican identity. Very few reported having friends or knowing anyone in the nearest city and less than 50% speak the official language of Portuguese. Finally, proximity to refugees who are often perceived as having privileged access to humanitarian aid, may further deteriorate the mental health of host community members. High levels of mental health burden across both refugees and hosts- if left unaddressed- can potentially limit the economic and social integration of refugees, which is critical to economic growth and stability necessary to provide long-term solutions for refugees

Women have unequal mental health burdens. We find women in the poor refugee communities in Mozambique are twice as likely to suffer from moderately severe or severe depression than men. This is in line with previous research that suggests that women and girls in conflict settings face biological and socioeconomic factors that make them more vulnerable to mental health disorders (40). Further, women can tend to suffer from lack of agency prevalent in most societies due to patriarchal tendencies which limit women’s choices and can engender more poor mental health outcomes.

We further examine the role of cognitive bias of pessimism, subjective feelings of loneliness and self-esteem on depression and anxiety rates in our sample. Among our sample, ‘Chronic Pessimists’ have a prevalence of Generalized Anxiety Disorder that is more than three times higher for refugees and more than 2.5 times higher for hosts. Additionally, the prevalence of depression is more than 2.5 times higher for both groups. This is consistent with evidence that finds patients suffering from Major Depressive Disorder lack optimistic bias in beliefs [

56]. Although evidence shows that asylum seekers and refugees frequently experience loneliness and isolation due to factors like language barriers, poverty and lack of social support, among others [

57], loneliness is not a good predictor of depression and anxiety in our sample. Self-esteem, or lack thereof, is a positive predictor of depression and anxiety for both refugees and hosts, doubling the likelihood of these conditions. Evidence to date confirms that low self-esteem and depression and anxiety are strongly related though more is needed to learn on the causality of the relationship- i.e., whether depression causes poor self-esteem, or vice versa. A meta review of the literature indicates that self-esteem has a significantly stronger impact on depression than depression has on self-esteem. In contrast, the effects of self-esteem and anxiety on each other are relatively balanced [

58]. This result indicates that in the studied refugee and host communities, mental health services would be more effective if they were integrated with programs aimed at improving self-esteem.

Being financially secure predicts a lower likelihood of experiencing both anxiety and depression symptoms. This is consistent with recent research that has established a bidirectional causal relationship between poverty and mental illness [

12]. These findings raise important questions about the drivers of poor mental health outcomes across refugee and host communities. Given the associated economic benefits of improved mental health, interventions to improve mental health should be part of the antipoverty toolkit alongside more traditional economic interventions.

The negative association between depression or anxiety and financial insecurity was driven by the host community, while the association between depression and anxiety for refugees was not statistically significant. Considering the evidence to date shows that refugees are consistently poorer than host communities [

18], this result is counter intuitive

. However, this could be at least partially due to the relatively small sample size of the refugee population, which limits the power to detect a relationship. On the other hand, refugees have higher levels of schooling than hosts, highlighting the low education outcomes among Mozambicans and their susceptibility to poverty.

Another important conclusion from the link between financial security and reduced mental health burdens, is that, for both impoverished refugees and Mozambicans, mental health and poverty appear to be interlinked. This finding is crucial for policymakers suggesting that in Mozambique (and potentially other contexts) poor host community members should be included in development programming aimed at improving mental health and reducing poverty.

Both refugees and Mozambicans with disabilities are more than three times as likely to suffer from anxiety and more than twice as likely to suffer from depression compared to those without disabilities. The disproportionate prevalence of anxiety and depression among persons with disabilities underscores the need for policy action to improve access to health services for both refugee and host communities in Mozambique. This would help to reduce the overall burden of treatable disabilities, such as eye conditions like Trachoma and Cataracts [

59] and enhance the overall health of individuals living with disabilities. Additionally, employment programs should prioritize the inclusion of individuals living with disabilities to improve mental health among both refugees and hosts

.

Limitations

Given limitations of interview time we had to shorten the full scale of the UCLA Loneliness scale Survey. In future assessments it would be useful to administer this full scale as well as the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire and particularly the Adverse Childhood Experiences Scale to understand more fully the causal relationship between daily life stressors, trauma, and adverse childhood experiences and mental health and disability outcomes.

Further future work is needed on this topic to better understand a more granular outcome for different segments of poor refugee and host community members and map heterogeneity of poverty among particularly refugee communities. We are limited by our sample size in our ability to undertake analysis based on age groups as well as cannot disaggregate for adolescent mental health outcomes, nor different household configurations such as households headed by female headed households. These questions are important to be able to target limited resources efficiently.

While the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7) questionnaires are standard questionnaires used in Mozambique and many global contexts, the measures of probability to be depressed or anxious that are produced are likely to be noisy compared to the gold standard clinical interviews diagnosing depression and anxiety. Future studies should make greater efforts to validate the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 questionnaires against clinical psychologist interviews, which provide the gold standard diagnosis among refugee and host communities. This will help understand the correlation between the measures and the relative noise of the PHQ-9 and GAD-7.

5. Conclusions

Our findings confirm the link between poverty and mental health, introducing disability as another contributing factor among poor refugees and host communities in Mozambique. Both refugees and host Mozambicans experience high levels of depression, anxiety, loneliness, pessimism, and disability with refugees, especially women, being more likely to suffer from moderate or severe depression. Notably, the incidence of depression and anxiety among these groups is significantly higher than the global average for low and middle-income-countries. Our results reinforce that exposure to conflict, trauma and ongoing poverty are major contributors to mental health among both refugees and hosts communities. This underscores the need for enhanced mental health and public health services for both refugees and hosts, with a particular focus on women.

Pessimism and low self-esteem are strong predictors of depression and anxiety. Mental health services should integrate programs aimed at improving self-esteem. Further, financial security is linked to lower likelihoods of anxiety and depression, suggesting that mental health interventions should be part of antipoverty programs.

Persons with disabilities are significantly more likely to suffer from anxiety and depression, highlighting the need for improved access to health services and inclusive employment programs. Additionally, poor mental health outcomes can hinder the economic and social integration of refugees, which is essential for the economic growth and stability needed for long-term solutions. Development programs should include both refugees and poor community members to effectively address mental health and poverty.

This paper is the first that we know of to examine the causal relationship across measures of mental health, disability burden, cognitive bias of pessimism, subjective feelings of loneliness and self-esteem, and socio-economic factors including financial security among the poorest segments of both refugees and host communities in in a forced displaced setting in Mozambique. We find comparably high levels of symptoms of depression, anxiety, loneliness, pessimism and disability across both poor refugees and surrounding host communities in Northern Mozambique.

Our findings also confirm the relationship between poor mental health and poverty, aligning with recent research that has established a directional relationship between the two. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis show that psychosocial interventions for common mental disorders, such as depression and anxiety, improve labour market outcomes, including employment, time spent working, capacity to work, and engagement in job search [

60]. Despite this growing evidence, few livelihoods and employment programmes are combined with interventions to reduce depression and anxiety, in particular for forcibly displaced populations. It is crucial to gather more empirical data on the effects of inclusive development programs aimed at reducing both poverty and mental health conditions for both displaced and host populations.

Author Contributions

T.B. and S.S. designed the study with inputs from F. N. and P. V.. F.N. led the statistical analysis supported by T.B. and S.S.. All authors assisted in interpretation of results. T.B. wrote a first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed substantially to revising the manuscript and approved submission.

Funding

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the International Growth Center, UNHCR, the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration (BPRM) who funded the cash transfer and employment support program evaluated and Sandra Sequeira acknowledges financial support from the European Research Council Starting Grant (REFUGEDEV). Finally, we thank the refugee and host community beneficiaries themselves for their willingness to respond to several surveys without which this project would not have been possible. This study was registered in the AEA RCT Registry as AEARCTR-0006902.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Research has been conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the LSE (REC ref. 000764) on October 8, 2018. Mozambique did not have an accredited local IRB committee that could assess external research projects when we started our project. To ensure the most rigorous standards of human subjects’ approval, this project was further approved by an independent ethics advisor (Andrew George, former Chair of the UK’s National Research Ethics Advisors’ Panel co-chair of the UK Committee on Research Integrity) as part of an assessment of ethical research practices for this project, required by the European Research Council. The randomized controlled trial (RCT) from which the reported data were obtained was registered on the American Economics Association RCT Registry- file number AEARCTR-0006902-(

https://www.socialscienceregistry.org/trials/6902). In line with both the IRB requirements at LSE and recommendations by the independent ethics advisor, due to limited literacy in the area studied, consent was obtained by each participant verbally.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data set and survey questionnaire will be made publicly available on the UNHCR Microdata Library in 2026.

Acknowledgments

We thank Anton Grahed, Rafael Frade and especially Matthew OBrien for excellent research assistance. We also thank Adaiana Lima, Luiz Fernando Rocha, Irene Omondi, Irchard Mohamed and Yara Ribeiro for their invaluable support with the data collection. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no competing interests.

References

- GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators, ‘Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017′, Lancet Lond. Engl., vol. 392, no. 10159, pp. 1789–1858, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- V. Patel et al., ‘The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development’, Lancet Lond. Engl., vol. 392, no. 10157, pp. 1553–1598, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- G. Müller et al., ‘Socio-economic consequences of mental distress: quantifying the impact of self-reported mental distress on the days of incapacity to work and medical costs in a two-year period: a longitudinal study in Germany’, BMC Public Health, vol. 21, no. 1, p. 625, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. L. Ettner, R. G. Frank, and R. C. Kessler, ‘The Impact of Psychiatric Disorders on Labor Market Outcomes’, Ind. Labor Relat. Rev., vol. 51, no. 1, pp. 64–81, 1997. [CrossRef]

- N. Morina, A. Akhtar, J. Barth, and U. Schnyder, ‘Psychiatric Disorders in Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons After Forced Displacement: A Systematic Review’, Front. Psychiatry, vol. 9, p. 433, 2018. [CrossRef]

- ‘Toxic Stress and PTSD in Children: Adversity in childhood is linked to mental and physical health throughout life—PMC’. Accessed: Feb. 29, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7592151/.

- F. Charlson, M. van Ommeren, A. Flaxman, J. Cornett, H. Whiteford, and S. Saxena, ‘New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis’, The Lancet, vol. 394, no. 10194, pp. 240–248, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Atamanov, Aziz, T. Beltramo, Reese, Benjamin Christopher, L. A. Rios Rivera, and Waita, Peter, ‘One year in the pandemic: Results from the High-Frequency Phone Surveys for Refugees in Uganda’. World Bank, 2021. [Online]. Available: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/36127.

- D. Silove, P. Ventevogel, and S. Rees, ‘The contemporary refugee crisis: an overview of mental health challenges’, World Psychiatry Off. J. World Psychiatr. Assoc. WPA, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 130–139, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. E. Klabbers et al., ‘Mental disorders and lack of social support among refugees and Ugandan nationals screening for HIV at health centers in Nakivale Refugee Settlement in southwestern Uganda’, J. Glob. Health Rep., vol. 6, p. e2022053, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Tanner, H. Mugera, D. Tabasso, M. Lazić, and B. Gillsäter, ‘ANSWERING THE CALL: FORCIBLY DISPLACED DURING THE PANDEMIC’.

- M. Ridley, G. Rao, F. Schilbach, and V. Patel, ‘Poverty, depression, and anxiety: Causal evidence and mechanisms’, Science, vol. 370, no. 6522, p. eaay0214, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Lund et al., ‘Poverty and common mental disorders in low and middle income countries: A systematic review’, Soc. Sci. Med. 1982, vol. 71, no. 3, pp. 517–528, Aug. 2010. [CrossRef]

- J. Sareen, T. O. Afifi, K. A. McMillan, and G. J. G. Asmundson, ‘Relationship Between Household Income and Mental Disorders: Findings From a Population-Based Longitudinal Study’, Arch. Gen. Psychiatry, vol. 68, no. 4, pp. 419–427, Apr. 2011. [CrossRef]

- E. J. Lenze and J. L. Wetherell, ‘A lifespan view of anxiety disorders’, Dialogues Clin. Neurosci., vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 381–399, Dec. 2011. [CrossRef]

- D. Frasquilho et al., ‘Mental health outcomes in times of economic recession: a systematic literature review’, BMC Public Health, vol. 16, no. 1, p. 115, Feb. 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. Lai, C. Due, and A. Ziersch, ‘The relationship between employment and health for people from refugee and asylum-seeking backgrounds: A systematic review of quantitative studies’, SSM—Popul. Health, vol. 18, p. 101075, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- UNHCR, ‘2023 Global Compact on Refugees Indicator Report’, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.unhcr.org/what-we-do/reports-and-publications/data-and-statistics/indicator-report-2023.

- J. Hoogevan and C. Obi, A Triple Win: Fiscal and Welfare Benefits of Economic Participation by Syrian Refugees in Jordan. World Bank, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://hdl.handle.net/10986/41574.

- T. P. Beltramo, R. Calvi, G. De Giorgi, and I. Sarr, ‘Child poverty among refugees’, World Dev., vol. 171, p. 106340, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Brunes, W. D. Flanders, and L. B. Augestad, ‘Physical activity and symptoms of anxiety and depression in adults with and without visual impairments: The HUNT Study’, Ment. Health Phys. Act., vol. 13, pp. 49–56, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- D. A. Pinals, L. Hovermale, D. Mauch, and L. Anacker, ‘Persons With Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities in the Mental Health System: Part 1. Clinical Considerations’, Psychiatr. Serv., vol. 73, no. 3, pp. 313–320, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Steptoe and G. Di Gessa, ‘Mental health and social interactions of older people with physical disabilities in England during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal cohort study’, Lancet Public Health, vol. 6, no. 6, pp. e365–e373, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J.-W. Noh, Y. D. Kwon, J. Park, I.-H. Oh, and J. Kim, ‘Relationship between Physical Disability and Depression by Gender: A Panel Regression Model’, PLoS ONE, vol. 11, no. 11, p. e0166238, Nov. 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Cree, ‘Frequent Mental Distress Among Adults, by Disability Status, Disability Type, and Selected Characteristics — United States, 2018′, MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep., vol. 69, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Kaur, L. Kamalyan, D. Abubaker, R. Alheresh, and T. Al-Rousan, ‘Self-reported Disability Among Recently Resettled Refugees in the United States: Results from the National Annual Survey of Refugees’, J. Immigr. Minor. Health, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 434–442, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- ‘Thematic note—Vision challenges for refugees and host communities in Kenya’, UNHCR. Accessed: Jul. 07, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.unhcr.org/media/thematic-note-vision-challenges-refugees-and-host-communities-kenya.

- D. V. Jeste, E. E. Lee, and S. Cacioppo, ‘Battling the Modern Behavioral Epidemic of Loneliness: Suggestions for Research and Interventions’, JAMA Psychiatry, vol. 77, no. 6, pp. 553–554, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Perlman, D. and Peplau, L.A., ‘Personal Relationships in Disorder’, in Toward a Social Psychology of Loneliness, vol. In: Duck, S.W. and Gilmour, R., London: Academic Press, 1981.

- G. M. L. Eglit, B. W. Palmer, A. S. Martin, X. Tu, and D. V. Jeste, ‘Loneliness in schizophrenia: Construct clarification, measurement, and clinical relevance’, PloS One, vol. 13, no. 3, p. e0194021, 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. A. Allen, B. E. Carey, C. McBride, R. M. Bagby, C. G. DeYoung, and L. C. Quilty, ‘Big Five aspects of personality interact to predict depression’, J. Pers., vol. 86, no. 4, pp. 714–725, 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. Hakulinen, M. Elovainio, L. Pulkki-Råback, M. Virtanen, M. Kivimäki, and M. Jokela, ‘Personality and Depressive Symptoms: Individual Participant Meta-Analysis of 10 Cohort Studies’, Depress. Anxiety, vol. 32, no. 7, pp. 461–470, 2015. [CrossRef]

- F. Nouri, A. Feizi, H. Afshar, A. Hassanzadeh Keshteli, and P. Adibi, ‘How Five-Factor Personality Traits Affect Psychological Distress and Depression? Results from a Large Population-Based Study’, Psychol. Stud., vol. 64, no. 1, pp. 59–69, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. Armbruster, L. Pieper, J. Klotsche, and J. Hoyer, ‘Predictions get tougher in older individuals: a longitudinal study of optimism, pessimism and depression’, Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol., vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 153–163, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Karhu, J. Veijola, and M. Hintsanen, ‘The bidirectional relationships of optimism and pessimism with depressive symptoms in adulthood—A 15-year follow-up study from Northern Finland Birth Cohorts’, J. Affect. Disord., vol. 362, pp. 468–476, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Karlsson et al., ‘Low Level of Optimism Predicts Initiation of Psychotherapy for Depression: Results from the Finnish Public Sector Study’, Psychother. Psychosom., vol. 80, no. 4, pp. 238–244, Apr. 2011. [CrossRef]

- F. A. R. Uribe, S. B. de Oliveira, A. G. Junior, and J. da Silva Pedroso, ‘Association between the dispositional optimism and depression in young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis’, Psicol. Reflex. E Crítica, vol. 34, no. 1, p. 37, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. E. Blackwell et al., ‘Optimism and mental imagery: A possible cognitive marker to promote well-being?’, Psychiatry Res., vol. 206, no. 1, pp. 56–61, Mar. 2013. [CrossRef]

- G. Chiovelli, S. Michalopulos, E. Papaioannou, and S. Sequeira, Forced displacement and human capital : evidence from separated siblings. in Discussion papers/CEPR. London : Centre for Economic Policy Research, 2021.

- UNHCR, ‘Country—Mozambique’. Accessed: Feb. 21, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://data.unhcr.org/en/country/moz.

- Banerjee et al., ‘A multifaceted program causes lasting progress for the very poor: Evidence from six countries’, Science, vol. 348, no. 6236, p. 1260799, May 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Sequiera, T. Beltramo, F. Nimoh, and M. O’Brien, ‘Financial Security, Climate Shock and Social Cohesion’, CEPR Discuss. Pap. No19296, 2024, [Online]. Available: https://cepr.org/publications/dp19296.

- M. Schreiner, ‘Simple Poverty Scorecard® Poverty-Assessment Tool Mozambique’.

- K. Kroenke, R. L. Spitzer, and J. B. W. Williams, ‘The PHQ-9′, J. Gen. Intern. Med., vol. 16, no. 9, pp. 606–613, Sep. 2001. [CrossRef]

- V. F. J. Cumbe et al., ‘Validity and item response theory properties of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for primary care depression screening in Mozambique (PHQ-9-MZ)’, BMC Psychiatry, vol. 20, no. 1, p. 382, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Di Gennaro et al., ‘High Prevalence of Mental Health Disorders in Adolescents and Youth Living with HIV: An Observational Study from Eight Health Services in Sofala Province, Mozambique’, AIDS Patient Care STDs, vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 123–129, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Pengpid, K. Peltzer, and B. Efraime, ‘Suicidal behaviour, depression and generalized anxiety and associated factors among female and male adolescents in Mozambique in 2022–23’, Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health, vol. 18, no. 1, p. 142, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. L. Lovero et al., ‘Leveraging Stakeholder Engagement and Virtual Environments to Develop a Strategy for Implementation of Adolescent Depression Services Integrated Within Primary Care Clinics of Mozambique’, Front. Public Health, vol. 10, p. 876062, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. K. Nyongesa et al., ‘Psychosocial and mental health challenges faced by emerging adults living with HIV and support systems aiding their positive coping: a qualitative study from the Kenyan coast’, BMC Public Health, vol. 22, no. 1, p. 76, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Mwita, E. Shemdoe, E. Mwampashe, D. Gunda, and B. Mmbaga, ‘Generalized anxiety symptoms among women attending antenatal clinic in Mwanza Tanzania; a cross-sectional study’, J. Affect. Disord. Rep., vol. 4, p. 100124, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. L. Spitzer, K. Kroenke, J. B. W. Williams, and B. Löwe, ‘A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7’, Arch. Intern. Med., vol. 166, no. 10, pp. 1092–1097, May 2006. [CrossRef]

- M. Rosenberg, Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton University Press, 1965. Accessed: Feb. 22, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt183pjjh.

- Sloman and M. Margaretha, ‘The Washington Group Short Set of Questions on Disability in Disaster Risk Reduction and humanitarian action: Lessons from practice’, Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct., vol. 31, pp. 995–1003, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators, ‘Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017’, Lancet Lond. Engl., vol. 392, no. 10159, pp. 1789–1858, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- F. Charlson, M. van Ommeren, A. Flaxman, J. Cornett, H. Whiteford, and S. Saxena, ‘New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis’, The Lancet, vol. 394, no. 10194, pp. 240–248, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. W. Korn, T. Sharot, H. Walter, H. R. Heekeren, and R. J. Dolan, ‘Depression is related to an absence of optimistically biased belief updating about future life events’, Psychol. Med., vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 579–592, Feb. 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Hynie, ‘The Social Determinants of Refugee Mental Health in the Post-Migration Context: A Critical Review’, Can. J. Psychiatry, vol. 63, no. 5, pp. 297–303, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- Julia Sowislo and Ulrich Orth, ‘Does Low Self-Esteem Predict Depression and Anxiety? A Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies’, Pyschological Bull., vol. 139, pp. 213–240, 2012. [CrossRef]

- K. L. Armstrong, M. Jovic, J. L. Vo-Phuoc, J. G. Thorpe, and B. L. Doolan, ‘The global cost of eliminating avoidable blindness’, Indian J. Ophthalmol., vol. 60, no. 5, pp. 475–480, 2012. [CrossRef]

- C. Lund et al., ‘The Effects of Mental Health Interventions on Labor Market Outcomes in Low- and Middle-Income Countries’, 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).