2.3. Syntheses of Allyldiamidinium and Diamidinium Salts

N-Methyl-

N-[1,3,3-tris(dimethylamino)-2-propenylidene]methanaminium chloride ([

1a]Cl): C

3Cl

5H (6.91 mL, 49 mmol) was added dropwise to a stirred solution of Me

2NH (40% water) (44 g, 392 mmol) at 0 °C for an hour. The solution was stirred overnight at ambient temperature to give a product mixture of [

1a]

+, [C

3(NMe

2)

3)]

+ (in a 1:4 ratio) and [Me

2NH

2]

+. After removing the solvent, the mixture was dissolved in acetonitrile:toluene (2:1) and kept in the freezer overnight to crystallize out the ammonium salts. [C

3(NMe

2)

3)]Cl was removed by acidification with aqueous HCl and extraction with CHCl

3. The solvent from the remaining solution was removed in vacuo, dissolved in acetone, and kept in a freezer to crystallize colorless crystals of [(Me

2N)

2CCHC(NMe

2)

2]Cl.2CHCl

3 (2.44 g, 10%) [

17]. EI-MS: Found m/z 213.2075 (M

+); Calcd: 213.2074 (M

+).

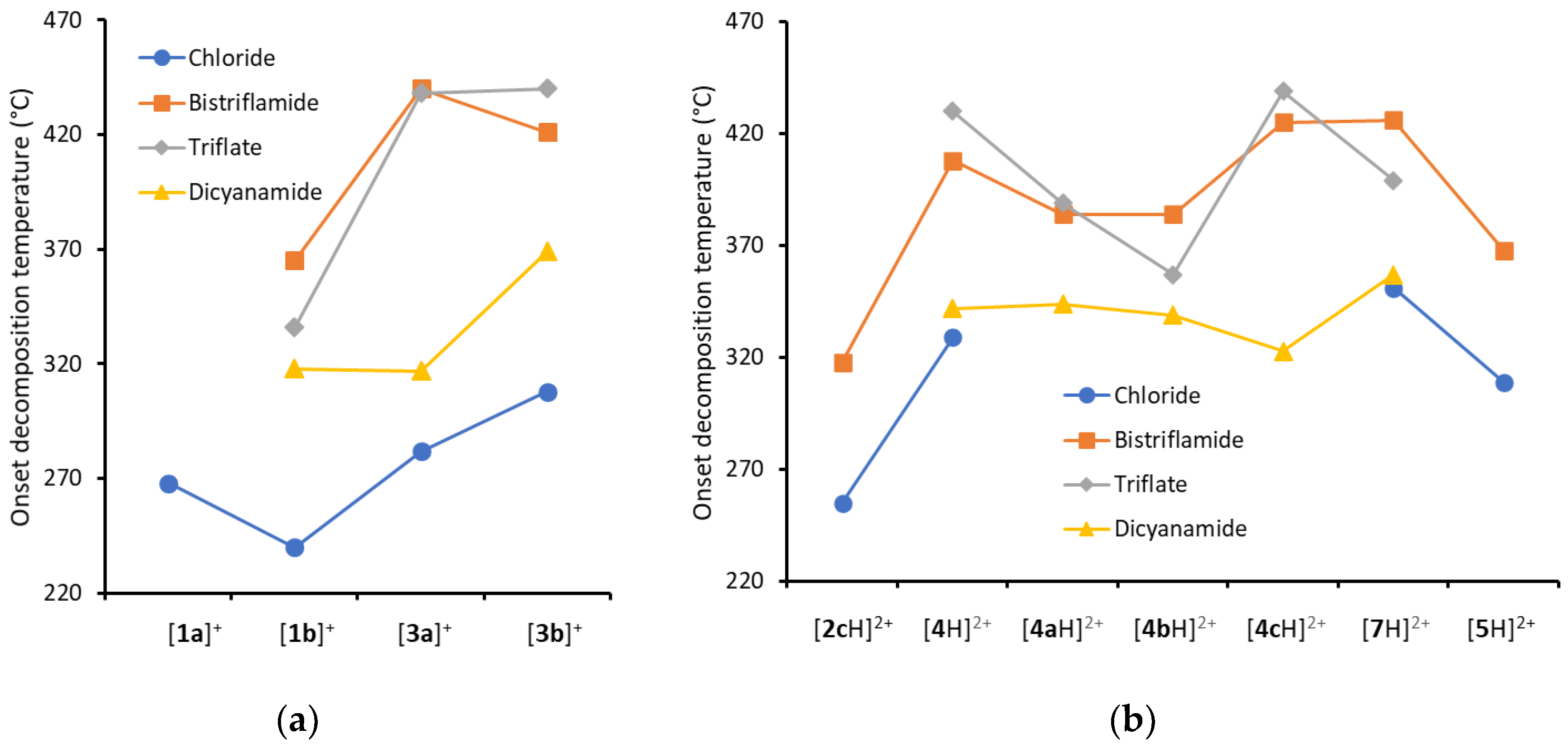

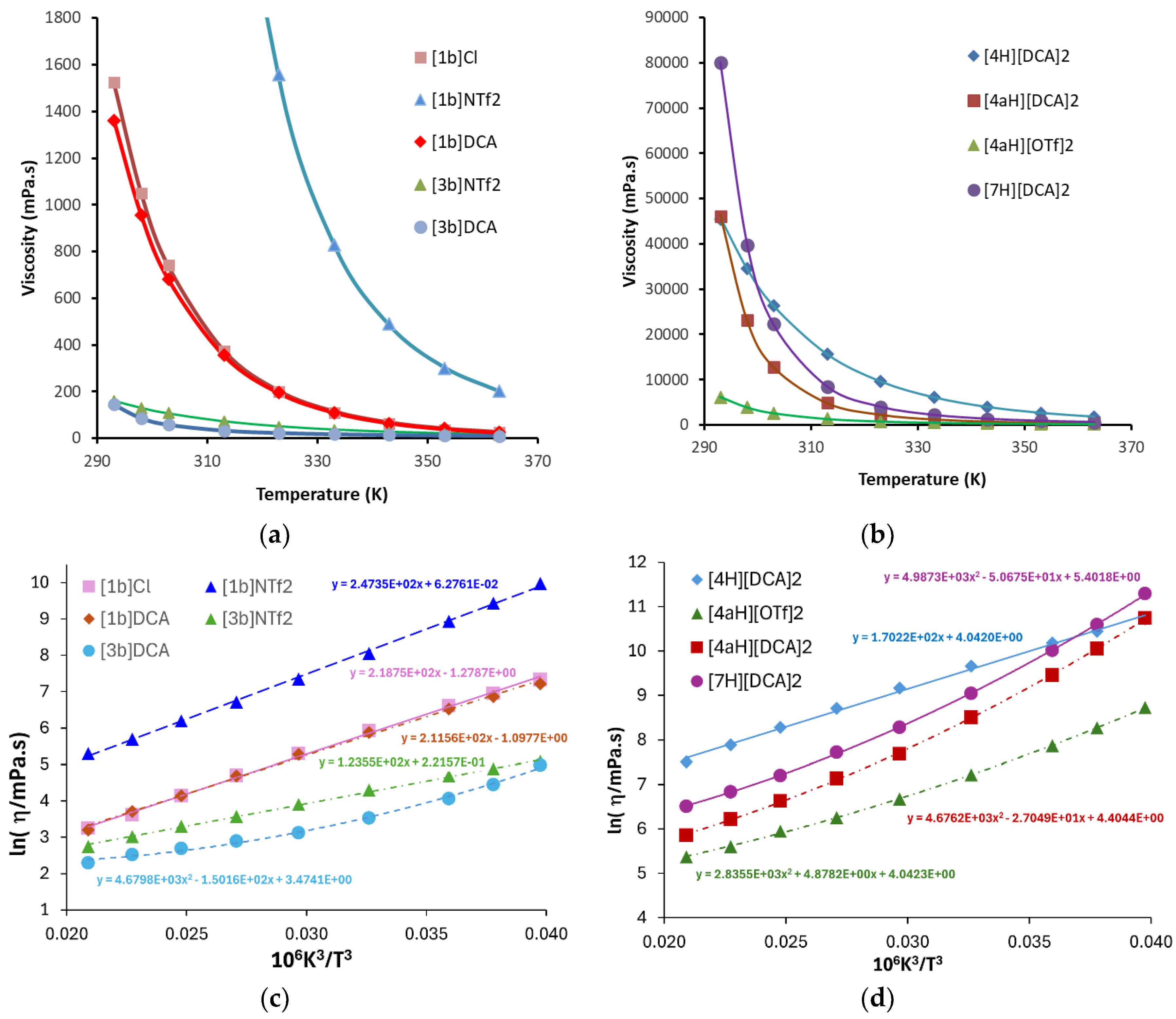

N-Ethyl-N-[1,3,3-tris(ethylmethylamino)-2-propenylidene]methanaminium chloride ([1b]Cl): C3Cl5H (4.312 g, 20.14 mmol) was dissolved in dichloromethane (150 mL) and cooled to 0 °C. Triethylamine (16.49 g, 163 mmol) and N-ethylmethylamine (6.024 g, 102 mmol) were added dropwise and the solution was then stirred overnight at ambient temperature. The reaction mixture was heated to reflux 5 h before removing the dichloromethane and excess amine in vacuo. Acetone 150 mL was added to the solution, the precipitated ammonium salt was filtered off, and acetone was removed in vacuo. Distilled water (50 mL) was added to the product and the pH adjusted to 9–10.5 by adding aqueous NaOH. The product was washed using diethylether (3 × 100 mL) to remove the excess amine and the solution was neutralized with HCl(aq). The closed-ring product was extracted with chloroform. The aqueous layer was acidified to pH 1–2 and the expected product extracted with dichloromethane. The removal of dichloromethane in vacuo yielded a dark red viscous liquid (4.8 g, 78.0%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 3.63 (s, 1H, CCHC), 3.29 (m, 8H, NCH2CH3), 2.97 (s, 12H, NCH3), 1.77 is H2O, 1.23 (t, 3JHH = 7.2 Hz, 12H, NCH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): 169.32 (CCHC), 48.22 (NCH2CH3), 38.13 (NCH2CH3), 13.36 (NCH3). EI MS: Found m/z 269.2708 (100%, M+), calcd 269.2705 (100%, M+).

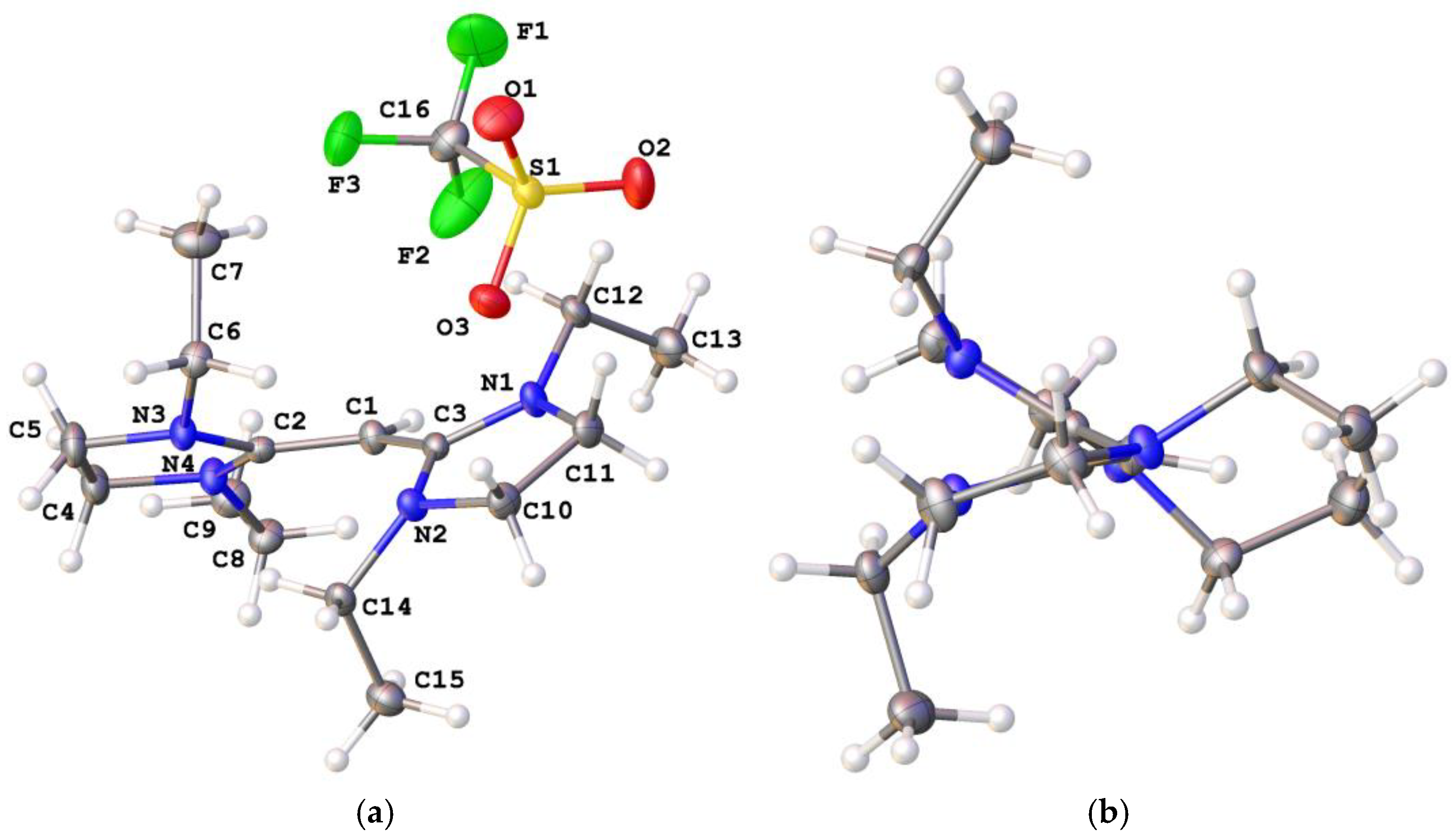

N-Ethyl-N-[1,3,3-tris(ethylmethylamino)-2-propenylidene]methanaminium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)amide ([1b]NTf2): [1b]Cl (1.701 g, 5.58 mmol) was stirred with LiNTf2 (9.801 g, 34.13 mmol) in 100 mL of water for 1 hour. The product was extracted using diethyl ether (3 × 75 mL), the organic layer was washed with water (3 × 100 mL), and the solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a dark-orange liquid (1.5 g, 88.23%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 3.62 (s, 1H, CCHC), 3.24 (m, 8H, NCH2CH3), 2.91 (s, 12H, NCH3), 1.56 is H2O, 1.22 (t, 3JHH = 7.2 Hz, 12H, NCH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): 169.51 (CCHC), 120.84 (q, 3JCF = 324 Hz, CF3), 48.18 (NCH2CH3), 37.85 (NCH2CH3), 13.15 (NCH3). EI MS: Found m/z 269.2708 (100%, M+), calcd 269.2705 (100%, M+). Microanalysis: calcd for C17H33F6N5O4S2 C, 37.15, H 6.05, N 12.74%; found C 37.30, H 6.05, N 12.56%.

N-Ethyl-N-[1,3,3-tris(ethylmethylamino)-2-propenylidene]methanaminium dicyanamide ([1b]DCA): [1b]Cl (1.46 g, 4.79 mmol) was stirred with NaDCA (0.854 g, 9.59 mmol) in distilled water (100 mL) for 4 hours. The product was extracted with dichloromethane (3 × 50 mL). The organic layer was washed with water (3 × 50 mL) and the solvent was removed in vacuo to give yellow liquid (0.956 g, 59.5%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 3.62 (s, 1H, CCHC), 3.42 (q, 3JHH = 7.0 Hz, 8H, NCH2CH3), 3.14 (s, 12H, NCH3), 1.29 (t, 3JHH = 7.0 Hz, 12H, NCH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 169.53 (CCHC), 50.33 (NCH3), 39.38 (NCH2CH3), 38.07 (CCHC), 13.17 (NCH2CH3). EI MS: Found m/z 269.2712 (M+), calcd 269.2705 (M+). Microanalysis: calcd for C17H33N7: C, 60.86, H 9.91, N 29.23%, found C 59.87, H 10.15, N 29.09%.

N-Ethyl-N-[1,3,3-tris(ethylmethylamino)-2-propenylidene]methanaminium trifluoromethanesulfonate ([1b]OTf): [1b]Cl (2.38 g, 7.81 mmol) was dissolved in 100 mL of distilled water. LiCF3SO3 (8.53 g, 54.67 mmol) was added to the solution and stirred for 1 hour. The product was extracted with dichloromethane (3 × 75 mL), washed with water (5 × 100 mL) and the organic layer was dried in vacuo to yield a yellow solid (2.14 g, 65.4%). 1H NMR (DMSO, 400 MHz): δ 3.64 (s, 1H, CCHC), 3.17 (q, 3JHH = 7.2 Hz, 8H, NCH2CH3), 3.16 is H2O, 2.84 (s, 12H, NCH3), 1.13 (t, 3JHH = 7.2 Hz, 12H, NCH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (DMSO, 100 MHz): 169.20 (CCHC), 47.89 (NCH2CH3), 37.86 (NCH2CH3), 13.38 (NCH3). EI MS: Found m/z 269.2708 (100%, M+), calcd 269.2705 (100%, M+). Microanalysis: Calcd for C16H33N4O3SF3: C, 45.51; H, 7.80; N, 13.27%. Found: C, 44.49; H, 7.83; N, 12.29%.

N,N′-[1,3-Bis(

t-butylamino)-1,3-propanediylidene]bis[

t-butanaminium] chloride ([

2cH]Cl

2):

n-butylamine (4.57 g, 62.48 mmol) was added dropwise to a stirred solution of C

3Cl

5H (3.34 g, 15.62 mmol) in dichloromethane (150 mL) at 0 °C and the reaction stirred overnight followed by reflux for 5 h. After removing the dichloromethane

in vacuo, the mixture was dissolved in aqueous NaOH and washed using diethyl ether (4 × 75 mL) to remove excess amine. The solvent was then removed in vacuo, and the mixture was dissolved in ethanol and filtered to remove NaCl. Removal of ethanol gives a brown viscous liquid (1.57 g, 25.3%). Characterization was consistent with previous work [

10]. Anal. calcd for C

19H

43N

4O

0.5Cl

2: C 56.12, H 10.65, N 13.78%; found C 55.65, H 10.72, N 13.82%.

N,N′-[1,3-Bis(t-butylamino)-1,3-propanediylidene]bis[t-butanaminium] bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)amide ([2cH][NTf2]2): [2cH]Cl2 (2.15 g, 5.41 mmol) was stirred with LiNTf2 (4.99 g, 17.4 mmol) in 100 mL water. The product was extracted using the diethyl ether (3 × 75 mL). The organic layer was collected and washed using water (4 × 50 mL) and the product dried in vacuo to yield a dark brown viscous liquid (3.00 g, 62.5%). 1H, 13C NMR and MS are similar to [C3H2(NHBu)4]Cl2 however, typical additional peaks for NTf2– were seen in the 13C{1H} NMR. Anal. calcd for C23H42N6O8F12S4: C 31.15, H 4.77, N 9.48%, found C 31.86, H 4.91, N 9.26%.

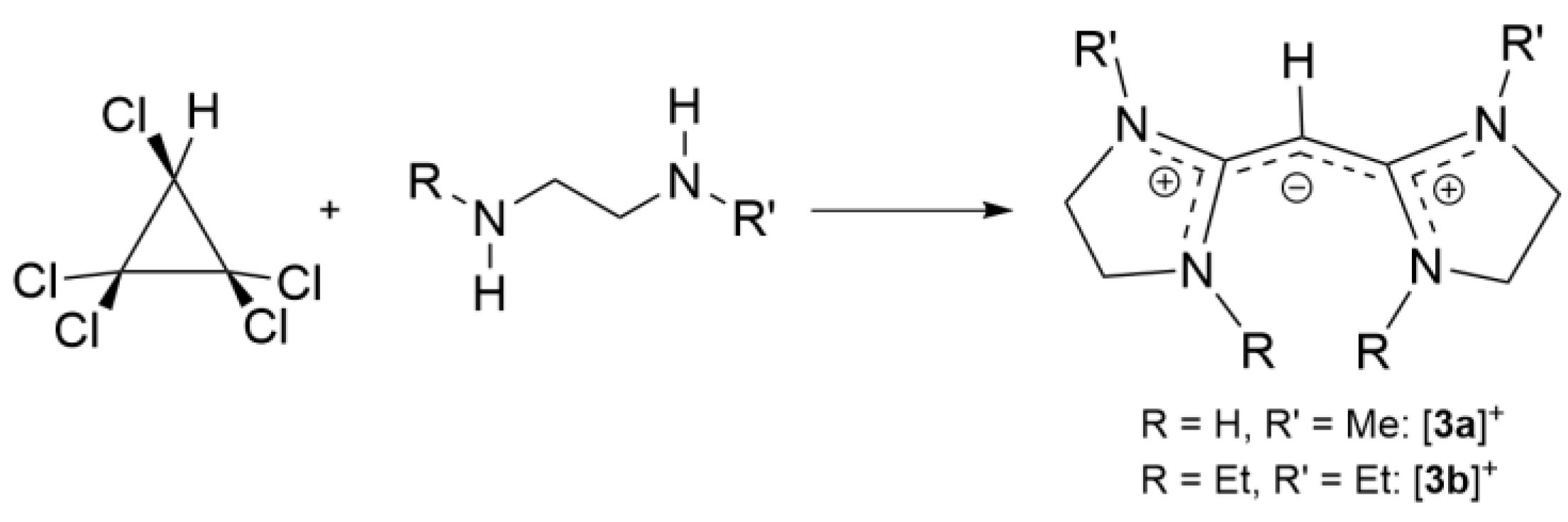

2-[(1-methyl-2-imidazolidinylidene)methyl]-4,5-dihydro-1-methyl-1H-imidazolium chloride ([3a]Cl): C3Cl5H (4.309 g, 20.11 mmol) was stirred with dichloromethane (100 mL) and cooled to 0 °C. N-methylethylendiamine (5.96 g, 80.40 mmol) was added dropwise to the ice-cold mixture and stirred for 2 h. Removed the precipitated salt and removed the solvent. Dilute NaOH was added and then washed using diethyl ether. The aqueous layer was neutralized and the product extracted using dichloromethane (3 × 75 mL). The solvent was removed and the product dried in vacuo to yield a light-yellow solid (2.32 g, 53.3%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): 8.79 (s, 2H, NH), 3.70 (t, 3JHH = 8 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2), 3.66 (s, 1H, CCHC), 3.51 (t, 3JHH = 8 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2), 2.85 (s, 6H, NCH3). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): 161.85 (CCHC), 55.72 (CCHC), 50.52 (NCH2CH2), 42.04 (NCH2CH2), 32.99 (NCH3). EI MS m/z found 181.1479 (100%, M+); calcd 181.1453 (100%, M+).

2-[(1-methyl-2-imidazolidinylidene)methyl]-4,5-dihydro-1-methyl-1H-imidazolium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonylamide)amide ([3a]NTf2): [3a]Cl (2.32 g, 10.71 mmol) was stirred with LiNTf2 (4.22 g, 14.7 mmol) in 100 mL water. The product was extracted using the diethyl ether (3 × 75 mL). The organic layer was washed with water (3 × 100 mL) and the product is dried in vacuo to yield a brown solid (2.28 g, 46.1%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 6.09 (s, 2H, NH), 3.72 (s, 1H, CCHC), 3.68 (t, 3JHH = 8 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2), 3.59 (t, 3JHH = 8 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2), 2.90 (s, 6H, NCH3). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): 163.54 (CCHC), 119.84 (q, 3JCF = 324 Hz, CF3), 55.98 (CCHC), 50.74 (NCH2CH2), 42.12 (NCH2CH2), 32.92 (NCH3). EI-MS: Found m/z 181.1457 (M+); calcd 181.1448 (M+). Microanalysis: calcd for C11H17F6N5O4S2: C, 28.63, H 3.71, N 15.18%; found C 28.43, H 3.67, N 14.96%.

2-[(1-methyl-2-imidazolidinylidene)methyl]-4,5-dihydro-1-methyl-1H-imidazolium dicyanamide ([3a]DCA): [3a]Cl (1.14 g, 5.26 mmol) was stirred with NaDCA (0.622 g, 6.99 mmol) in distilled water (50 mL) for 4 h. The product was extracted with dichloromethane (4 × 75 mL). The organic layer was washed with water (3 × 50 mL) and the solvent was removed in vacuo to give a light-yellow oil (0.753 g, 57.9%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 7.98 (s, 2H, NH), 3.70 (t, 3JHH = 7.5 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2), 3.68 (s, 1H, CCHC), 3.55 (t, 3JHH = 7.5 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2), 2.88 (s, 6H, NCH3). 13C{1H} NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 161.85 (CHCC), 50.55 (CCHC), 50.52 (NCH2CH2), 42.10 (NCH2CH2), 32.98 (NCH3). EI-MS: Found m/z 181.1446 (M+), calcd 181.1448 (M+). Microanalysis: calcd for C11H17N7: C 53.42, H 6.93, N 39.65%; found C 52.26, H 7.27, N 39.72%.

2-[(1-methyl-2-imidazolidinylidene)methyl]-4,5-dihydro-1-methyl-1H-imidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate ([3a]OTf): [3a]Cl (3.073 g, 14.18 mmol) was stirred with LiCF3SO3 (3.043 g, 19.50 mmol) in 100 mL water. The product was extracted using the diethyl ether (3 × 75 mL). The organic layer was washed with water (3 × 100mL) and the product dried in vacuo to yield a brown solid (1.374 g, 29.3%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 7.01 (s, 2H, NH), 3.70 (t, 3JHH = 8 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2), 3.67 (s, 1H, CCHC), 3.55 (t, 3JHH = 8 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2), 2.88 (s, 6H, NCH3). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): 161.54 (CCHC), 119.84 (q, 3JCF = 324 Hz, CF3), 55.98 (CCHC), 50.76 (NCH2CH2), 42.13 (NCH2CH2), 32.94 (NCH3). EI MS: Found m/z 181.1457 (M+), calcd 181.1448 (M+). Microanalysis: calcd for C10H17F3N4O3S: C, 36.36, H 5.19, N 16.96%; found C 36.09, H 5.11, N 16.96%.

2-[(1,3-diethyl-2-imidazolidinylidene)methyl]-4,5-dihydro-1,3-diethyl-1H-imidazolium chloride ([3b]Cl): N,N’-diethylethylenediamine (2.16 g, 18.66 mmol) and triethylamine (1.94 mL, 13.98 mmol) were added dropwise to C3HCl5 (1.04 g, 4.85 mmol) in chloroform at 0 °C and the reaction stirred overnight under an inert atmosphere. The precipitated salt was filtered off and excess solvent was removed in vacuo. The product was dissolved in slightly basic water (50 mL) and the product was washed with diethyl ether (4 × 75 mL). The aqueous layer was neutralized and extracted the product using the chloroform (4 × 50 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo. The crude product was dissolved in chloroform/ethanol (1:3) and passed through a silica column. The product was collected and the solvent removed to give a yellow liquid (0.861 g, 59.0%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 3.67 (s, 8H, NCH2CH2), 3.49 (s, 1H, CCHC), 3.20 (q, 3JHH = 7.2 Hz, 8H, NCH2CH3), 1.14 (t, 3JHH = 7.2 Hz, 12H NCH2CH3). 13C {1H} NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 163.27 (CHCC), 52.71 (CCHC), 46.67 (NCH2CH2), 43.04 (NCH2CH3), 11.93 (NCH2CH3). EI-MS: Found m/z 265.2383 (M+), calcd 265.2392 (M+).

2-[(1,3-diethyl-2-imidazolidinylidene)methyl]-4,5-dihydro-1,3-diethyl-1H-imidazolium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)amide ([3b]NTf2): [3b]Cl (0.221 g, 0.735 mmol) was stirred with LiNTf2 (0.337 g, 1.17 mmol) in distilled water (50 mL) for 4 hours. The product was extracted with dichloromethane (4 × 75 mL). The organic layer was washed with water (3 × 50 mL) and the solvent was removed in vacuo to give a light-yellow oil (0.212 g, 52.9%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 3.60 (s, 8H, NCH2CH2), 3.49 (s, 1H, CCHC), 3.20 (q, 3JHH = 7.2 Hz, 8H, NCH2CH3), 1.15 (t, 3JHH = 7.2 Hz, 12H, NCH2CH3). 13C {1H} NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 163.39 (CHCC), 120.04 (q, 1JCF = 321.6 Hz, CF3), 52.70 (CCHC), 46.40 (NCH2CH2), 42.98 (NCH2CH3), 11.75 (NCH2CH3). EI MS: Found m/z 265.2445 (M+), calcd 265.2392 (M+). Microanalysis: calcd for C17H29F6N5O4S2: C 37.43, H 5.36, N 12.84%; found C 36.87, H 5.35, N 13.09%.

2-[(1,3-diethyl-2-imidazolidinylidene)methyl]-4,5-dihydro-1,3-diethyl-1H-imidazolium dicyanamide ([3b]DCA): [3b]Cl (0.371 g, 1.23 mmol) was stirred with NaDCA (0.175 g, 1.97 mmol) in distilled water (50 mL) for 4 h. The product was extracted with dichloromethane (4 × 75 mL). The organic layer was washed with water (3 × 50 mL) and the solvent was removed in vacuo to give a light-yellow oil (0.261 g, 64.0%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 3.65 (s, 8H, NCH2CH2), 3.56 (s, 1H, CCHC), 3.26 (q, 3JHH = 7.2 Hz, 8H, NCH2CH3), 1.19 (t, 3JHH = 7.2 Hz, 12H, NCH2CH3). 13C {1H} NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 163.43 (CHCC), 120.06 (CN), 52.87 (CCHC), 46.52 (NCH2CH2), 43.09 (NCH2CH3), 11.92 (NCH2CH3). EI MS: Found m/z 265.2424 (M+), calcd 265.2392 (M+). Microanalysis: calcd for C17H29N7: C 61.60, H 8.82, N 29.58%; found C 60.94, H 8.60, N 28.80%.

2-[(1,3-diethyl-2-imidazolidinylidene)methyl]-4,5-dihydro-1,3-diethyl-1H-imidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate ([3b]OTf): [3b]Cl (0.27 g, 0.898 mmol) was stirred with LiOTf (0.22 g, 1.41 mmol) in distilled water (50 mL) for 4 h. The product was extracted with dichloromethane (4 × 75 mL). The organic layer was washed with water (3 × 50 mL) and the solvent was removed in vacuo to give a yellow solid (0.259 g, 69.6%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 3.64 (s, 8H, NCH2CH2), 3.51 (s, 1H, CCHC), 3.21 (q, 3JHH = 7.2 Hz, 8H, NCH2CH3), 1.16 (t, 3JHH = 7.2 Hz, 12H, NCH2CH3). 13C {1H} NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 163.36 (CHCC), 121.04 (q, 1JCF = 322.6 Hz, CF3), 52.69 (CCHC), 46.47 (NCH2CH2), 43.00 (NCH2CH3), 11.83 (NCH2CH3). EI-MS: Found m/z 265.2397 (M+); Calcd: 265.2392 (M+). Microanalysis: calcd for C16H29F3N4O3S: C 46.36, H 7.05, N 13.52%; found C 45.57, H 7.06, N 13.70%.

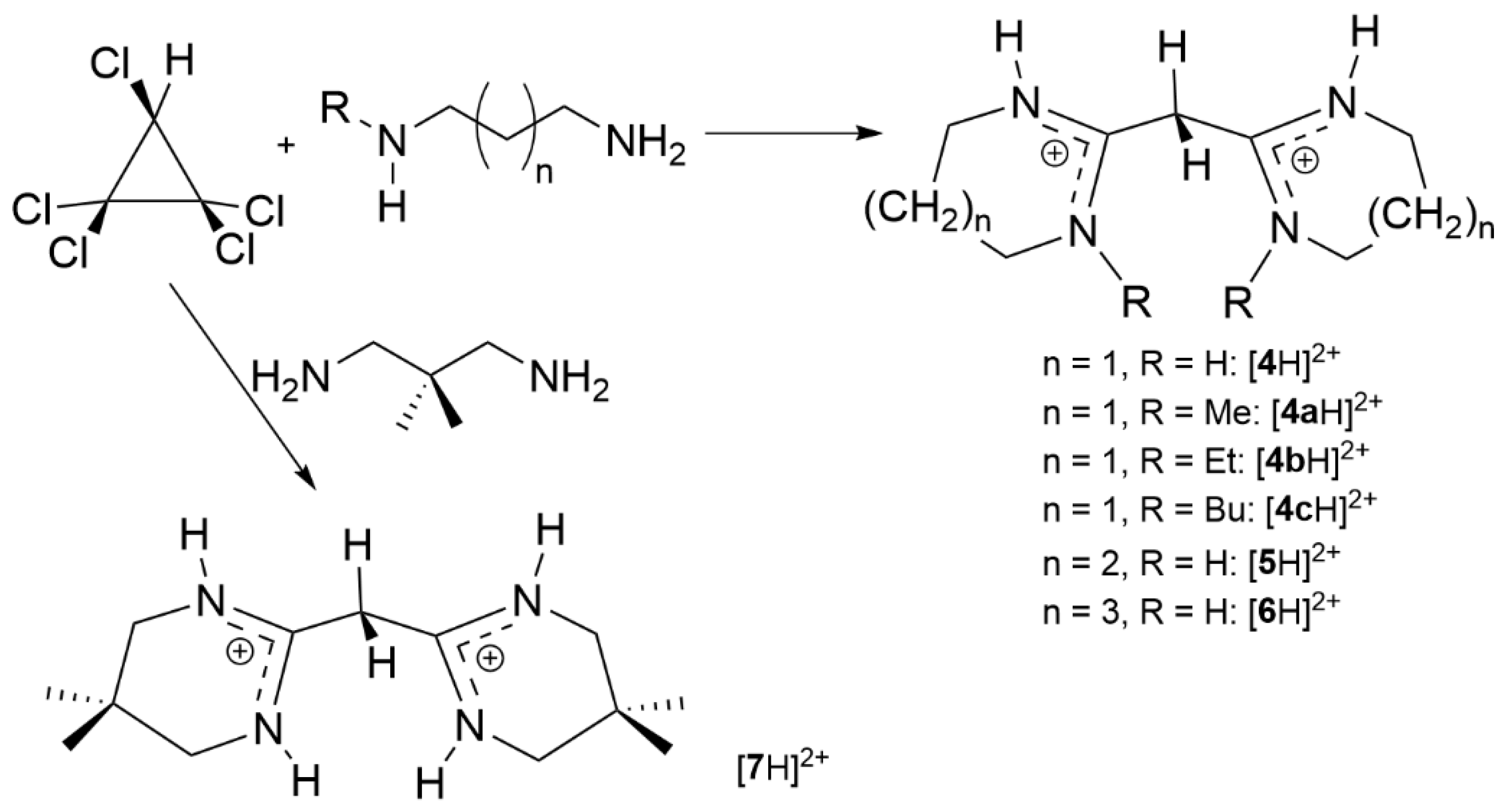

2,2′-Methylenebis [3,4,5,6-tetrahydropyrimidinium] chloride ([4H]Cl2): Propane-1,3-diamine (2.22 g, 30.01 mmol) was added dropwise to C3Cl5H (1.60 g, 7.503 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (150 mL) at 0 °C and the reaction stirred for 1 hour. After filtering off the precipitated salt, the solution was washed using distilled water (3 × 75 mL). The CH2Cl2 was removed to yield a highly-hygroscopic light-orange solid (1.14 g, 71%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): 11.17 (s, NH, 4H), 4.36 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.51 (t, 3JHH = 4 Hz, 8H, NCH2CH2CH2), 2.16 is H2O, 2.00 (q, JHH = 4 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): 156.90 (CCHC), 39.14 (HNCH2CH2CH2NH), 38.13 (CCH2C), 32.48 (HNCH2CH2CH2NH), 17.79 (HNCH2CH2CH2NH). ES+ m/z found: 91.0766 (100%, M2+). Calcd. 91.0760 (100%, M2+).

2,2′-Methylenebis[3,4,5,6-tetrahydropyrimidinium] bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)amide ([4H][NTf2]2): [4H]Cl2 (0.66 g, 2.6 mmol) was stirred with AgNO3 (0.445 g, 2.6 mmol) in 100 mL of distilled water. The precipitated AgCl was removed and LiNTf2 was added (1.16 g, 4.04 mmol). The solution was stirred for 2 h. The product was extracted using diethyl ether (4 × 75 mL) and washed with distilled water (4 × 50 mL) to remove excess salt. The organic layer was dried to yield a brown solid (1.30 g, 67%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): 11.16 (s, NH, 4H), 4.36 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.51 (t, 3JHH = 4 Hz, 8H, NCH2CH2CH2), 2.00 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2).13C NMR (CDCl3): 156.90 (CCHC), 39.14 (HNCH2CH2CH2NH), 38.4 (CCH2C), 32.48 (HNCH2CH2CH2NH), 17.79 (HNCH2CH2CH2NH). ES+ m/z found: 91.0772 (100%, M2+). Calcd. 91.0760 (100%, M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C13H18F12N6O8S4: C, 21.03, H 2.44, N 11.32%; found C 21.12, H 2.30, N 11.45%.

2,2′-Methylenebis[3,4,5,6-tetrahydropyrimidinium] dicyanamide ([4H][DCA]2): [4H]Cl2 (1.98 g, 7.82 mmol) was stirred with AgNO3 (1.32 g, 7.82 mmol) in 100 mL of distilled water. The precipitated AgCl was removed and NaDCA (0.905 g, 10.16 mmol) was added. The solution was stirred for 4 h and the product was extracted with chloroform (4 × 75 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield an orange liquid (1.67 g, 68%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 11.08 (s, 4H, NH), 4.33 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.51 (m, 8H, NCH2CH2CH2), 2.00 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2).13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, DMSO): δ 157.03 (CCH2C), 39.27 (NCH2CH2CH2), 32.52 (CCH2C), 17.81 (NCH2CH2CH2). EI MS: Found m/z 91.0755 (M2+); Calcd: 91.0760 (M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C13H18N10: C, 49.67, H 5.77, N 44.56%; found C 47.45, H 6.30, N 44.40%.

2,2′-Methylenebis[3,4,5,6-tetrahydropyrimidinium] trifluoromethylsulfonate ([4H][OTf]2): [4H]Cl2 (1.89 g, 7.46 mmol) was stirred with AgNO3 (1.28 g, 7.46 mmol) in 100 mL of distilled water. The precipitated AgCl was filtered off and LiOTf (1.51 g, 9.68 mmol) was added. The solution was stirred for 4 h and the product was extracted using chloroform (4 × 75 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to give an orange solid (0.974 g, 42%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 9.91 (s, 4H, NH), 3.75 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.31 (m, 8H, NCH2CH2CH2), 1.83 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2).13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, DMSO): δ 156.41 (CCHC), 121.15, 39.04 (NCH2CH2CH2), 35.09 (NCH2CH2CH2), 17.51 (NCH2CH2CH2). EI MS: Found m/z 91.0764 (M2+); Calcd: 91.0760 (M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C11H18F6N4O6S2: C, 27.50, H 3.78, N 11.66%; found C 26.60, H 3.30, N 11.45%.

2,2′-Methylenebis[3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-1-methylpyrimidinium] chloride ([4aH]Cl2): N-methyl-1,3-propanediamine (1.30 g, 14.8 mmol) was added dropwise to C3HCl5 (0.99 g, 4.62 mmol) in chloroform (150 mL) at 0 ℃ and the reaction stirred overnight under an inert atmosphere. The precipitated salt was filtered off and the solvent was removed in vacuo. The product was dissolved in distilled water and washed several times with diethyl ether to remove unreacted amine. The product was extracted with chloroform and the organic layer washed with distilled water (4 × 50 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a yellow solid (1.1 g, 85%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 11.31 (s, 2H, NH), 4.60 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.67 (t, 3JHH = 6.0 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2), 3.60 (t, 3JHH = 5.5 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2), 3.37 (s, 6H, NCH3), 2.11 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 156.71 (CCH2C), 49.63 (NCH2CH2CH2), 40.47 (NCH2CH2CH2), 38.92 (NCH3), 33.35 (CCH2C), 18.92 (NCH2CH2CH2). EI-MS: Found m/z 105.0917 (M2+); Calcd: 105.0917 (M2+).

2,2′-Methylenebis[3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-1-methylpyrimidinium] bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)amide ([4aH][NTf2]2): [4aH]Cl2 (0.984 g, 3.50 mmol) was stirred with LiNTf2 (1.27 g, 4.42 mmol) in 100 mL of distilled water. The product was extracted with chloroform (4 × 75 mL) and washed with distilled water (3 × 50 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a yellow solid (1.47 g, 86.3%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 9.46 (s, 2H, NH), 4.04 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.45 (t, 3JHH = 6.0 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2), 3.09 (s, 6H, NCH3), 1.92 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 156.20 (CCH2C), 119.92 (q, 1JCF = 324 Hz, CF3), 49.15 (NCH2CH2CH2), 38.97 (NCH2CH2CH2), 34.29 (NCH2CH2CH2), 33.47 (CCH2C), 19.68 (NCH3). EI MS: Found m/z 105.0916 (M2+); Calcd: 105.0915 (M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C15H22F12N6O8S4: C, 23.38, H 2.88, N 10.91%; found C 24.58, H 2.28, N 10.44%.

2,2′-Methylenebis[3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-1-methylpyrimidinium] dicyanamide ([4aH][DCA]2): [4aH]Cl2 (0.984 g, 3.50 mmol) was stirred with NaDCA (0.498 g, 5.60 mmol) in 100 mL of distilled water. The product was extracted with chloroform and ethanol mixture (4 × 75 mL). Then, washed with distilled water (3 × 50 mL) and the solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a brown liquid (0.784, 82%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 10.22 (s, 2H, NH), 4.65 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.99 (t, 3JHH = 6.0 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2), 3.83 (t, 3JHH = 6.0 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2) overlapping with water peak, 3.63 (s, 6H, NCH3), 2.45 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2 CH2). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, DMSO): δ 156.20 (CCH2C), 49.15 (NCH2CH2CH2), 38.97 (NCH2CH2CH2), 34.22 (NCH2CH2CH2), 33.47 (CCH2C), 19.68 (NCH3). EI MS: Found m/z 105.0912 (M2+); Calcd: 105.0915 (M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C15H22N10: C, 52.62, H 6.48, N 40.91%; found C 52.36, H 7.32, N 39.30%.

2,2′-Methylenebis[3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-1-methylpyrimidinium] triflate ([4aH][OTf]2): [4aH]Cl2 (0.794 g, 2.81 mmol) was stirred with LiOTf (0.571 g, 3.65 mmol) in 100 mL of distilled water. The product was extracted with chloroform (4 × 75 mL) and washed with distilled water (3 × 50 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a yellow solid (0.975 g, 65%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 9.46 (s, 2H, NH), 4.04 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.45 (t, 3JHH = 6.0 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2), 3.09 (s, 6H, NCH3), 1.92 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 156.20 (CCH2C), 119.92 (q, 1JCF = 324 Hz, CF3), 49.15 (NCH2CH2CH2), 38.97 (NCH2CH2CH2), 34.29 (NCH2CH2CH2), 33.47 (CCH2C), 19.68 (NCH3). EI MS: Found m/z 105.0916 (M2+); Calcd: 105.0915 (M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C15H26F6N4O6S2: C, 33.58, H 4.88, N 10.44%; found C 32.69, H 4.45, N 10.40%.

2,2′-Methylenebis[3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-1-ethylpyrimidinium] chloride ([4bH]Cl2): N-ethyl-1,3-propanediamine (3.85 mL, 31.17 mmol) was added dropwise to C3Cl5H (1.67 g, 7.79 mmol) in chloroform (150 mL) at 0 °C and the reaction stirred overnight under an inert atmosphere. The solvent was removed in vacuo after filtering the precipitated salt. The product was dissolved in distilled water and washed several times with diethyl ether to remove unreacted amine. The product was extracted using chloroform and the organic layer was washed with distilled water (4 × 50 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a brown solid (1.4 g, 84%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3CN): δ 10.25 (s, 2H, NH), 4.30 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.48 (t, 3JHH = 6.0 Hz, 8H, NCH2CH2CH2) (overlapping with CH2 in ethyl group), 3.54 (t, 3JHH = 7.8 Hz, NCH2CH2CH2), 2.10 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2), 1.12 (t, 3JHH = 7.3 Hz, 6H, NCH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CD3CN): δ 155.43 (CCH2C), 52.83 (NCH2CH2CH2), 47.23 (NCH2CH2CH2), 29.27 (CCH2C), 20.03 (NCH2CH3), 13.84 (NCH2CH3). EI-MS: Found m/z 119.1072 (M2+); Calcd: 119.1073 (M2+).

2,2′-Methylenebis[3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-1-ethylpyrimidinium] bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)amide ([4bH][NTf2]2): [4bH]Cl2 (1.46 g, 5.63 mmol) was stirred with LiNTf2 (2.51 g, 8.74 mmol) in 100 mL of distilled water. The product was extracted with dichloromethane (4 × 75 mL) and washed with distilled water (3 × 50 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a white solid (1.29 g, 88%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 9.48 (s, 2H, NH), 4.12 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.53 (t, 3JHH = 6.0 Hz, 8H, NCH2CH2CH2) (overlapping with CH2 in ethyl group), 3.54 (t, 3JHH = 7.8 Hz, NCH2CH2CH2), 1.85 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2), 1.12 (t, 3JHH = 7.3 Hz, 6H, NCH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CD3CN): δ 155.75 (CCH2C), 119.92 (q, 1JCF = 324 Hz, CF3), 52.22 (NCH2CH2CH2), 46.87 (NCH2CH2CH2), 33.56 (CCH2C), 29.29 (NCH2CH3), 18.52 (NCH2CH2CH2), 14.18 (NCH2CH3). EI MS: Found m/z 119.1072 (M2+); calcd 119.1073 (M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C17H26F12N6O8S4: C, 25.57, H 3.28, N 10.52%; found C 25.52, H 3.26, N 10.50%.

2,2′-Methylenebis[3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-1-ethylpyrimidinium] dicyanamide ([4bH][DCA]2): [4bH]Cl2 (1.34 g, 4.33 mmol) was stirred with NaDCA (0.698 g, 7.84 mmol) in 100 mL of distilled water. The product was extracted with chloroform and ethanol mixture (4 × 75 mL) and then washed with distilled water (3 × 50 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a white solid (1.08 g, 74%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 10.25 (s, 2H, NH), 4.30 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.48 (t, 3JHH = 6.0 Hz, 8H, NCH2CH2CH2) (overlapping with CH2 in ethyl group), 3.54 (t, 3JHH = 7.8 Hz, NCH2CH2CH2), 2.10 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2), 1.12 (t, 3JHH = 7.3 Hz, 6H, NCH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CD3CN): δ 155.43 (CCH2C), 52.83 (NCH2CH2CH2), 47.23 (NCH2CH2CH2), 29.27 (CCH2C), 20.03 (NCH2CH3), 13.84 (NCH2CH3). EI-MS: Found m/z 119.1072 (M2+); calcd 119.1073 (M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C17H26N10: C, 55.12, H 7.07, N 37.81%; found C 53.78, H 7.25, N 37.56%.

2,2′-Methylenebis[3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-1-ethylpyrimidinium] trifluoromethylsulfonate ([4bH][OTf]2): [4bH]Cl2 (1.73 g, 6.32 mmol) was stirred with LiOTf (1.57 g, 10.06 mmol) in 100 mL of distilled water. The product was extracted with chloroform and ethanol mixture (4 × 75 mL) and washed with distilled water (3 × 50 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a brown solid (1.21 g, 45%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 10.25 (s, 2H, NH), 4.30 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.48 (t, 3JHH = 6.0 Hz, 8H, NCH2CH2CH2) (overlapping with CH2 in ethyl group), 3.54 (t, 3JHH = 7.8 Hz, NCH2CH2CH2), 2.10 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2), 1.12 (t, 3JHH = 7.3 Hz, 6H, NCH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CD3CN): δ 155.75 (CCH2C), 119.92 (q, 1JCF = 324 Hz, CF3), 52.22 (NCH2CH2CH2), 46.87 (NCH2CH2CH2), 33.56 (CCH2C), 29.29 (NCH2CH3), 18.52 (NCH2CH2CH2), 14.18 (NCH2CH3). EI MS: Found m/z 119.1072 (M2+); calcd: 119.1073 (M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C15H26F6N4O6S2: C, 33.58, H 4.88, N 10.44%; found C 33.46, H 4.56, N 10.40%.

2,2′-Methylenebis[3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-1-butylpyrimidinium] chloride ([4cH]Cl2): N-butyl-1,3-propanediamine (4.56 mL, 28.7 mmol) was added dropwise to C3HCl5 (1.50 g, 7.00 mmol) in chloroform (150 mL) at 0 °C and the reaction stirred overnight under an inert atmosphere. The solvent was removed in vacuo after filtering the precipitated salt. The product was dissolved in distilled water and washed several times with diethyl ether to remove unreacted amine. The product was extracted using chloroform and the organic layer was washed with distilled water (4 × 50 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a brown solid (1.2 g, 47%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 11.30 (s, 2H, NH), 4.47 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.67 (t, 3JHH = 6.0 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2), 3.63 (m, 4H, HNCH2), 3.54 (t, 3JHH = 7.8 Hz, NCH2CH2CH2), 2.10 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2), 1.65 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 1.37 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 0.97 (t, 3JHH = 7.3 Hz, 6H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 155.43 (CCH2C), 52.83 (NCH2CH2CH2), 47.23 (NCH2CH2CH2), 39.27 (NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 29.27 (CCH2C), 20.03 (NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 18.82 (NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 13.84 (NCH2CH2CH2CH3). EI MS: Found m/z 147.1388 (M2+); Calcd 147.1386 (M2+).

2,2′-Methylenebis[3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-1-butylpyrimidinium] bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)amide ([4cH][NTf2]2): [4cH]Cl2 (1.67 g, 4.56 mmol) was stirred with LiNTf2 (1.99 g, 6.93 mmol) in 100 mL of distilled water. The product was extracted with dichloromethane (4 × 75 mL) and washed with distilled water (3 × 50 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a white solid (1.35 g, 46%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 9.44 (s, 2H, NH), 4.04 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.49 (t, 3JHH = 5.5 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2), 3.36 (t, 3JHH = 7.3 Hz, NCH2CH2CH2), 1.92 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2), 1.54 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 1.26 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 0.89 (t, 3JHH = 7.32 Hz, 6H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 155.73 (CCH2C), 119.92 (q, 1JCF = 324 Hz, CF3), 52.28 (NCH2CH2CH2), 46.95 (NCH2CH2CH2), 33.66 (NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 29.33 (CCH2C), 19.69 (NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 18.53 (NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 14.16 (NCH2CH2CH2CH3). EI MS: Found m/z 147.1383 (M2+); Calcd 147.1386 (M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C21H34F12N6O8S4: C, 29.51, H 4.01, N 9.83%; found C 30.44, H 4.10, N 10.03%.

2,2′-Methylenebis[3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-1-butylpyrimidinium] dicyanamide ([4cH][DCA]2): [4cH]Cl2 (1.67 g, 4.56 mmol) was stirred with NaDCA (1.99 g, 22.35 mmol) in 100 mL of distilled water. The product was extracted with chloroform and ethanol mixture (4 × 75 mL). Then, washed with distilled water (3 × 50 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a white solid (1.35 g, 69.4%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 9.44 (s, 2H, NH), 4.04 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.48 (t, 3JHH = 5.5 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2), 3.35 (t, 3JHH = 7.3 Hz, NCH2CH2CH2) 3.30 (s, H2O), 1.92 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2), 1.54 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 1.27 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 0.89 (t, 3JHH = 7.32 Hz, 6H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3).13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 155.75 (CCH2C), 119.92 (s, CN), 52.22 (NCH2CH2CH2), 46.87 (NCH2CH2CH2), 33.56 (CCH2C), 29.29 (NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 19.71 (NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 18.52 (NCH2CH2CH2),14.18 (NCH2CH2CH2CH3). EI MS: Found m/z 147.1383 (M2+); Calcd: 147.1386 (M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C21H34N10: C, 59.13, H 8.03, N 32.84%. Calc found C 58.99, H 8.98, N 32.58%.

2,2′-Methylenebis[3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-1-butylpyrimidinium] trifluoromethylsulfonate ([4cH][OTf]2): [4cH]Cl2 (1.67 g, 4.56 mmol) was stirred with LiOTf (1.26 g, 8.08 mmol) in 100 mL of distilled water. The product was extracted with chloroform and ethanol mixture (4 × 75 mL) and washed with distilled water (3 × 50 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a brown solid (1.47 g, 61%).1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 9.89 (s, 2H, NH), 4.16 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.49 (t, 3JHH = 5.5 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2), 3.32 (t, 3JHH = 7.3 Hz, NCH2CH2CH2) 3.30 (s, H2O ), 1.91 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2), 1.54 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 1.27 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 0.87 (t, 3JHH = 7.32 Hz, 6H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 155.75 (CCH2C), 119.92 (q, 1JCF = 324 Hz, CF3), 52.22 (NCH2CH2CH2), 46.87 (NCH2CH2CH2), 33.56 (CCH2C), 29.29 (NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 19.71 (NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 18.52 (NCH2CH2CH2), 14.18 (NCH2CH2CH2CH3). EI-MS: Found m/z 147.1384 (M2+) Calcd 147.1386 (M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C19H34F6N4O6S2: C, 38.51, H 5.78, N 9.45%; found C 38.94, H 5.67, N 10.05%.

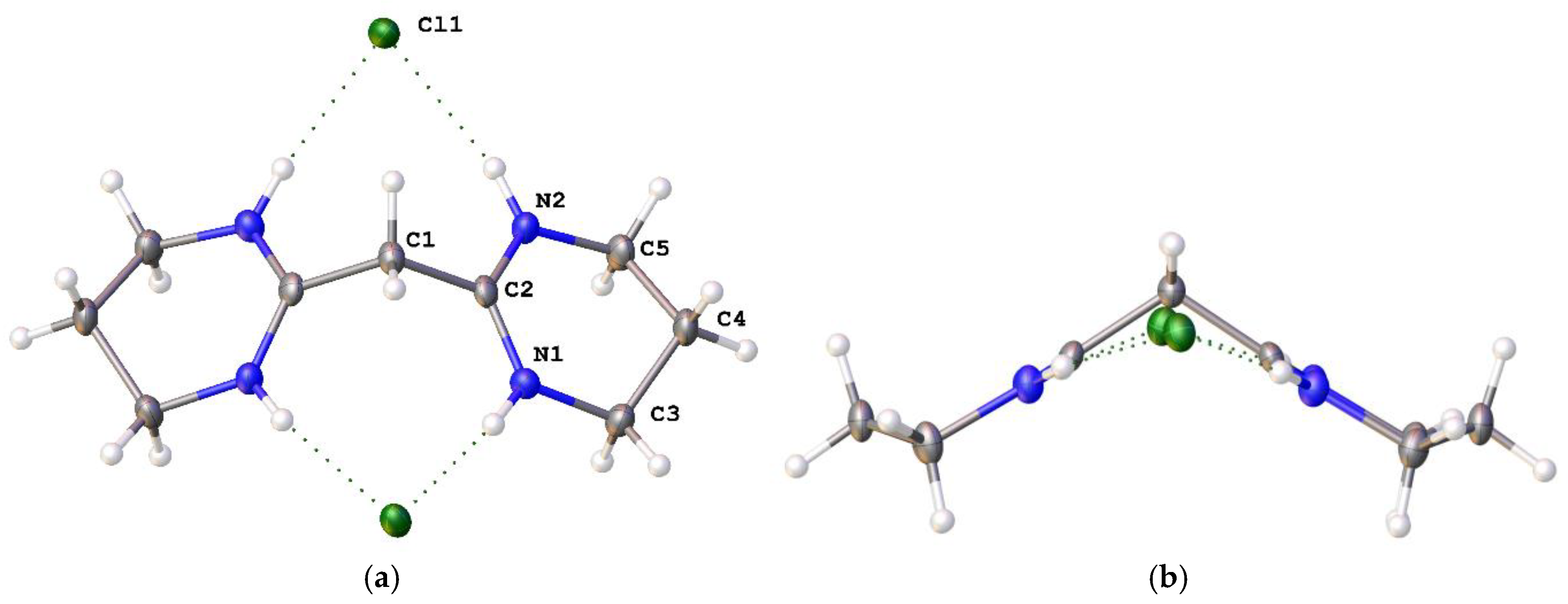

2,2′-Methylenebis[4,5,6,7-tetrahydrodiazepinium] chloride ([5H]Cl2): 1,4-Butanediamine (2.92 g, 33.12 mmol) was added dropwise to C3Cl5H (1.77 g, 8.26 mmol) in dichloromethane (150 mL) at 0 °C and the solution stirred for one hour. After filtering the precipitated salt and removing the solvent, the residual salt was removed by dissolving in dichloromethane (100 mL) and washing with water (4 × 50 mL). Removal of dichloromethane in vacuo yielded a light-yellow solid (1.56 g, 67.2%). The solid was recrystallized using a vapour diffusion technique to give colourless crystals. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): 11.05 (s, NH, 4H), 4.24 (s, CCH2C, 2H), 3.65 (m, NCH2CH2CH2CH2, 8H) 2.04 (m, NCH2CH2CH2CH2, 8H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): 161.13 (CCHC), 44.14 (NCH2CH2CH2CH2), 35.73 (CCH2C), 26.16 (NCH2CH2CH2CH2). ES+ m/z: found 105.0921 (100%, M2+). Calcd. 105.0916 (100%, M2+).

2,2′-Methylenebis[4,5,6,7-tetrahydrodiazepinium] bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)amide ([5H][NTf2]2): [5H]Cl2 (1.608 g, 5.72 mmol) was stirred with AgNO3 (0.971 g, 5.72 mmol) in distilled water (100 mL). The precipitated AgCl was removed and LiNTf2 (2.55 g, 8.88 mmol) added. The solution was stirred for 2 h. The product was extracted with diethyl ether (4 × 75 mL) and washed with distilled water (4 × 50 mL) to remove excess salt. The organic layer was dried to yield a red solid (1.12 g, 32.7%). 1H NMR (DMSO, 400 MHz): 9.43 (s, NH, 4H), 3.59 (s, CCH2C, 2H), 3.30 is H2O, 3.51 (m, NCH2CH2CH2CH2, 8H), 1.92 (m, NCH2CH2CH2CH2, 8H). 13C NMR (DMSO, 100 MHz): 161.13 (CCHC), 35.73 (CCH2C), 44.14 (NCH2CH2CH2CH2), 26.16 (NCH2CH2CH2CH). ES+ m/z found: 105.0919 (100%, M2+). Calcd 105.0916 (100%, M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C15H22F12N6O8S4: C, 23.38, H 2.88, N 10.91%; found C 23.28, H 2.28, N 10.44%.

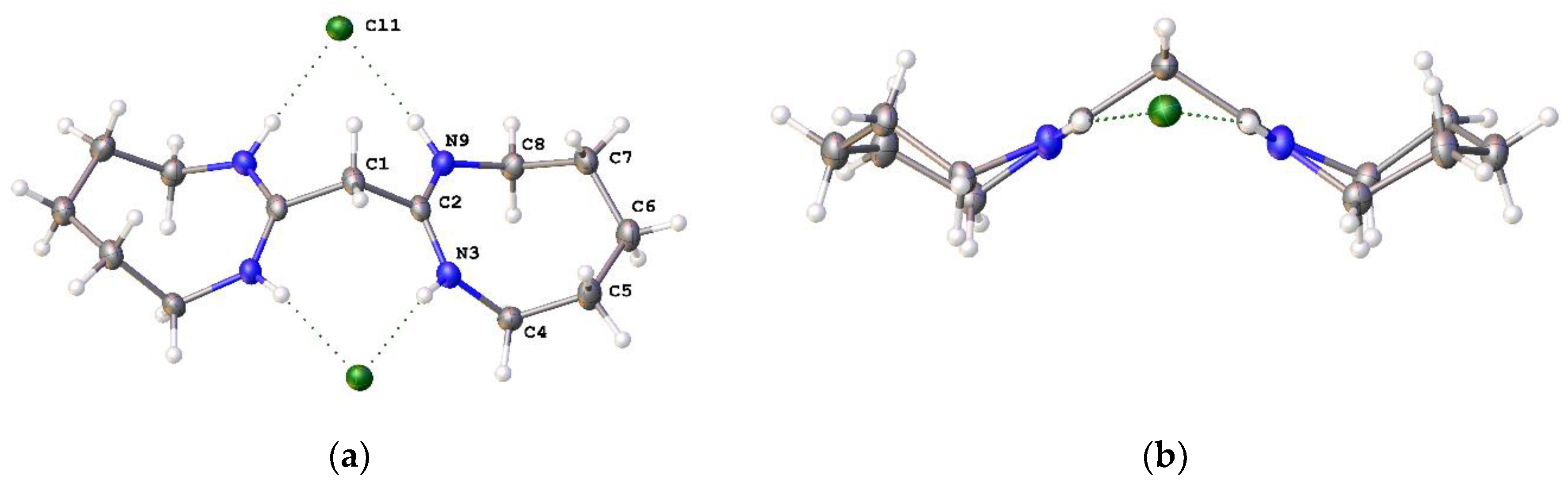

2,2′-Methylenebis[3,4,5,6,7,8-hexahydrodiazocinium] chloride ([6H]Cl2): 1,5-pentanediamine (2.86 g, 28.0 mmol) was added dropwise to C3HCl5 (1.50 g, 7.00 mmol) in chloroform (150 mL) at 0 °C and the reaction stirred overnight under an inert atmosphere. The precipitated salt was filtered and the solvent was removed in vacuo. The product was dissolved in distilled water and washed several times with diethyl ether to remove unreacted amine. The product was extracted with chloroform and the organic layer washed with distilled water (4 × 50 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a yellow solid (1.31 g, 60.5%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 11.00 (s, 4H, NH), 4.29 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.73 (q, JHH = 6.4 Hz, 8H, NCH2(CH2)3CH2), 1.98 (m, 8H, N(CH2)2(CH2)2CH2), 1.65 (m, 4H, N(CH2)2(CH2)2CH2). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 160.21 (CCH2C), 42.13 (NCH2(CH2)3CH2), 36.63 (CCH2C), 29.48 (N(CH2)2(CH2)2CH2), 20.27 (N(CH2)2(CH2)2CH2). EI-MS: Found m/z 119.1073 (M2+); Calcd 119.1073 (M2+). Td at 10 °C/min = 330 °C.

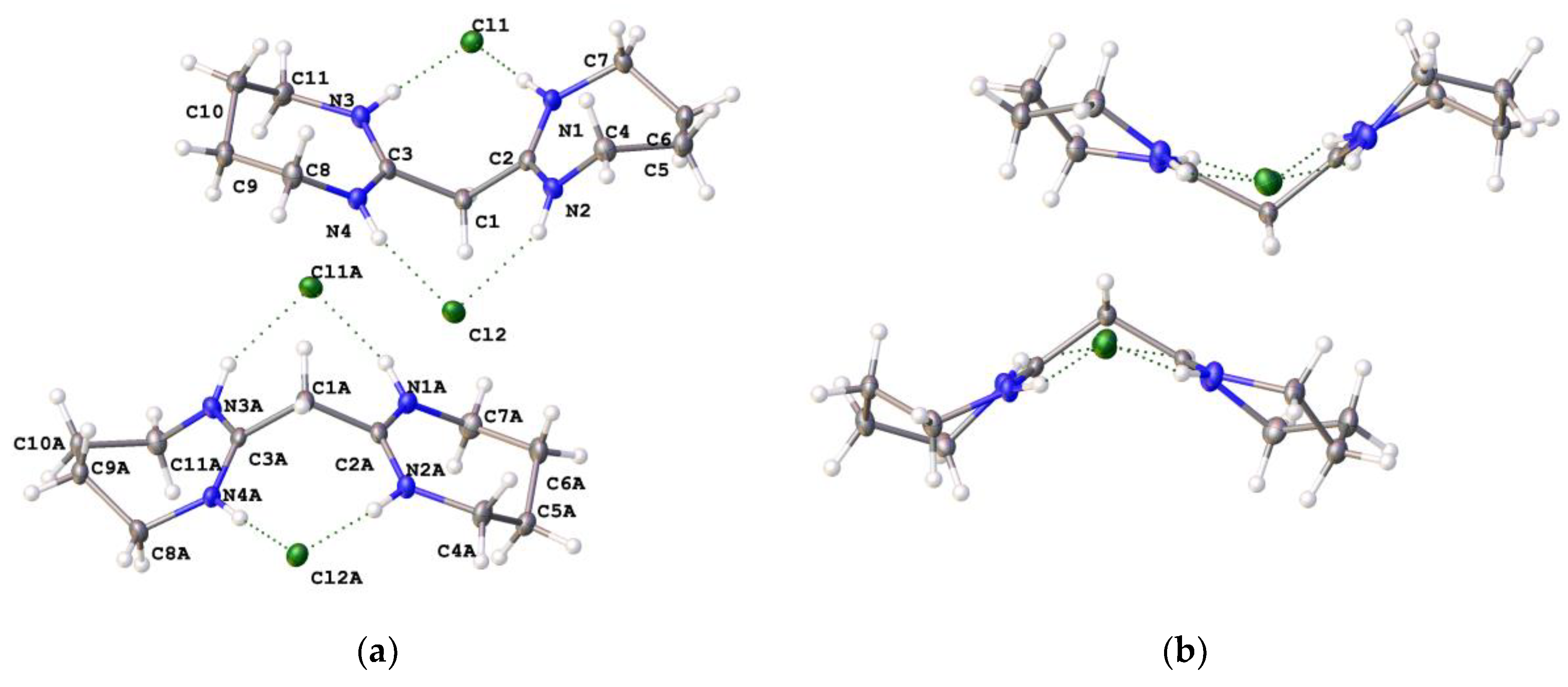

2,2′-Methylenebis[3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-5,5-dimethylpyrimidinium] chloride ([7H]Cl2): 2,2-Dimethyl-1,3-propanediamine (8.21 g, 80.4 mmol) was added dropwise to C3Cl5H (4.30 g, 20.10 mmol) in dichloromethane (150 mL) at 0 ℃ and the reaction stirred for one hour. After filtering the precipitated salt and removing the solvents, the residual salt was removed by dissolving in dichloromethane (100 mL) and washing with water (4 × 50 mL). Removal of dichloromethane in vacuo yielded a light-yellow liquid which solidified overnight (2.41 g, 56%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): 11.24 (s, NH, 4H), 4.44 (s, CCH2C, 1H), 3.15 (s, NCH2C(CH3)2CH2, 8H), 1.05 (s, CH3, 12H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): 156.37 (CCH2C), 50.41 (NCH2 CH2), 49.49 (CCH2C), 25.49 (C(CH3)2), 24.17 (C(CH3)2. ES+ m/z: found 119.1070 (100 %, M2+); calcd 119.1073 (100 %, M2+).

2,2′-Methylenebis[3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-5,5-dimethylpyrimidinium] bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)amide ([7H][NTf2]2): [7H]Cl2 (1.08 g, 3.49 mmol) was stirred with AgNO3 (0.592 g, 3.49 mmol) in distilled water (100 mL). The precipitated AgCl was removed and LiNTf2 (1.53 g, 5.33 mmol) was added. The solution was stirred for 2 h. The product was extracted using diethyl ether (4 × 75 mL) and washed with distilled water (4 × 50 mL) to remove excess salt. The organic layer was dried to yield a brown solid (1.968 g, 71.0%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): 9.79 (s, NH, 4H), 3.72 (s, CCH2C, 2H), 3.04 (s, NCH2C(CH3)2CH2, 8H), 0.96 (s, CCH3, 12H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): 156.37 (CCH2C), 50.41 (NCH2C(CH3)2CH2), 49.49 (CCH2C), 25.49 (C(CH3)2), 24.17 (C(CH3)2). ES+ m/z found: 119.1076 (100%, M2+), calcd 119.1073 (100%, M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C17H26F12N6O8S4: C 25.57, H 3.28, N 10.52%; found C 25.50, H 3.26, N 10.51%.

2,2′-Methylenebis[3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-5,5-dimethylpyrimidinium] dicyanamide ([7H][DCA]2): [7H]Cl2 (2.41 g, 7.79 mmol) was stirred with AgNO3 (1.32 g, 7.79 mmol) in 100 mL of distilled water. The precipitated AgCl was removed and NaDCA (1.17 g, 10.27 mmol) was added. The solution was stirred for 4 h and the product was extracted with chloroform (4 × 75 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield an orange liquid (1.23 g, 51%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.22 (s, 4H, NH), 4.34 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.15 (s, 8H, NCH2C(CH3)2CH2), 1.05 (s, 12H, CCH3). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 156.58 (CCH2C), 50.49 (NCH2C(CH3)2CH2), 49.45 (CCH2C), 25.49 (C(CH3)2), 24.21 (C(CH3)2). EI MS: Found m/z 119.1074 (M2+); Calcd: 119.1073 (M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C17H26N10: C 55.12, H 7.07, N 37.81%; found C 54.57, H 7.08, N 37.16%.

2,2′-Methylenebis[3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-5,5-dimethylpyrimidinium] trifluoromethanesulfonate ([7H][OTf]2): [7H]Cl2 (2.33 g, 7.53 mmol) was stirred with AgNO3 (1.27 g, 7.53 mmol) in 100 mL of distilled water. The precipitated AgCl was removed and LiOTf (1.94 g, 12.4 mmol) was added. The solution was stirred for 4 h and the product was extracted with chloroform (4 × 75 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield an orange solid (1.56 g, 47%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 10.96 (s, 4H, NH), 4.29 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.15 (s, 8H, NCH2C(CH3)2CH2), 1.04 (s, 12H, CCH3). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 156.58 (CCH2C), 50.49 (NCH2C(CH3)2CH2), 49.45 (CCH2C), 25.49 (C(CH3)2), 24.21 (C(CH3)2). EI MS: Found m/z 119.1072 (M2+); Calcd: 119.1073 (M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C15H26F6N4O6S2: C, 33.58, H 4.88, N 10.44%; found C 32.69, H 4.45, N 10.40%.