1. Introduction

SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, has evolved substantially since its emergence in late 2019 [

1], with the omicron lineage emerging in 2022 and markedly diversifying into a series of sublineages [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Ongoing mutations in the spike protein are central to the classification of sublineages and are associated with increased transmissibility, immune evasion and receptor binding [

6,

7]. Other SARS-CoV-2 genes [

8] are also undergoing evolutionary changes [

9] that impact a range of virus-host interactions [

10,

11,

12]. Omicron lineage viruses were characterized by increased replication in the upper (versus the lower) respiratory track [

12] and a great capacity to infect ciliated epithelial cells [

13,

14] when compared with earlier lineage viruses. Targeting these cells facilitates viral transit across the mucus layer, as well as disrupting mucocilary clearance [

15,

16].

SARS-CoV-2 infection is generally diagnosed by RT-PCR or protein-based diagnostic tests performed on material collected from patients via nasopharyngeal swabs [

17,

18]. Such sampling collects not only viral RNA and protein, but also host cells and cellular debris from the nasopharyngeal track. Such swabs thus provide a readily available source of both viral RNA and human cellular mRNA from a major site of infection in COVID-19 patients [

19]. We thus sought to determine what information might be gleaned by RNA-Seq analysis of nasopharyngeal swabs, correlating the data with patient information, with the aim of increasing the understanding of nasopharyngeal infections by omicron sublineages in humans.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics and Regulatory Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all patients involved in the study. Nasopharyngeal swabs were collected from 49 COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU of the Royal Adelaide Hospital from October 2022 to August 2023. Swabs were placed into TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen) and stored at -80°C prior to transport to QIMR Berghofer. Approval was obtained from the Central Adelaide Local Health Network (CALHN) Human Research Ethics Committee (CALHN13050). Approval was also obtained from the QIMR Berghofer Human Research Ethics Committee (Ref: P3600), with all samples and patient data deidentified prior to being sent to QIMR Berghofer. Research at QIMR Berghofer was approved by the Institutional Safety Committee.

2.2. RNA-Seq and Bioinformatics

RNA was extracted from TRIzol according to manufacturer’s instructions. DNAse I treatment (New England Biolabs) and RNA clean-up was undertaken using RNeasy MinElute Cleanup Kit (QIAGEN), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The Agilent 4200 Tape Station was used to provide RIN scores. Library preparations and ribosomal RNA depletions were undertaken using TrueSeq Stranded Total RNA Sample Preparation Kit, with Ribo-Zero (Illumina). Tape Station D1000 Screen Tape was used to assess the fragment size of the completed libraries; samples where cDNA amplicons could not be detected did not progress to sequencing. ThermoFisher Qubit 4 Fluorometer was used to measure the concentration of the completed libraries. Sequencing was performed using NextSeq 2000 using the flow cell P3 Reagent (200 cycles), providing 76 bp paired-end reads. All samples were run in a single sequencing run; Q30 was 89.97%.

STAR aligner was used to align the RNA-Seq reads to a combined SARS-CoV-2 BA.5 (GenBank: OP604184.1) and human (GRCh38, version 38) reference genome [

20]. Samtools v1.16 [

21] was used to generate viral read counts expressed as viral reads per million reads (RPM). RSEM v1.3.1 was used to generate read counts for host genes; differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using DESeq2 v1.40.2 [

22]. DEGs were analyzed using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA, v84978992) (QIAGEN). Relative abundance of specific cell types was estimated via cellular deconvolution using the SpatialDecon package in R [

23,

24], with cell-type expression matrices obtained from the human lung cell atlas [

25] (

https://data.humancellatlas.org/explore/projects/c4077b3c-5c98-4d26-a614-246d12c2e5d7).

2.3. RT-qPCR of Nasopharyngeal Samples

cDNA synthesis (from the purified RNA from the nasopharyngeal swab samples) was undertaken using ProtoScript II First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (New England Biolabs). RT-qPCR was performed using iTaq Universal Probes Supermix (Bio-Rad) and SARS-CoV-2 (Sarbeco-E) primers; Forward: 5′-ACAGGTACGTTAATAGTTAATAGCGT-3′, Reverse: 5′-ATATTGCAGCAGTACG CACACA -3’ [

26]. The florescent probe was 5’-FAM-ACACTAGCCATCCTTACTGCGCTTCG- ZEN™/Iowa Black® FQ-3’ (Integrated DNA Technologies Australia). BioRad CFX96 was used to perform RT-qPCR with the following cycling conditions: incubation at 50°C for 10 min, followed by 3 min at 95°C, then 40 cycles of 15 secs at 95°C and 30 secs at 60°C.

2.4. Phylogenetic Tree Generation

The Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV; v.2.9.4) [

27] was used to align the viral sequences retrieved from RNA-Seq to the original SARS-CoV-2 strain. Consensus spike sequences were extracted from IGV, followed by translation via Expasy (online tool:

https://web.expasy.org/translate/). MegaX (v.11) was used to generate the phylogenetic tree. Sublineages were classified further based on their spike mutations using GISAID.

2.5. Statistics

Correlations were undertaken using SPSS Statistics (v23) (IBM). Fischer’s exact tests were performed using JNP Pro (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Omicron Sublineages and Viral Read Counts from COVID-19 ICU Patients

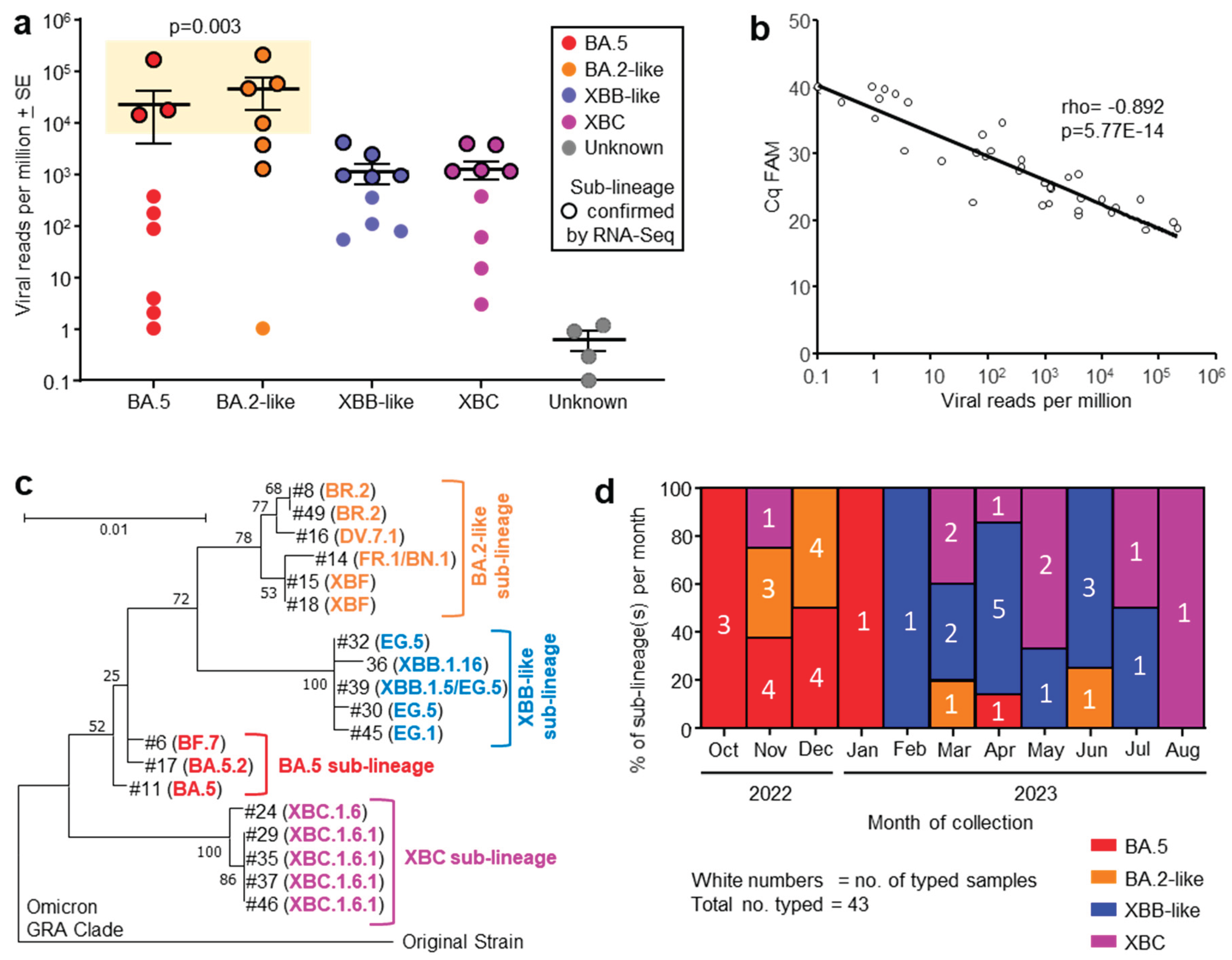

Human nasopharyngeal swab samples were obtained from consented COVID-19 patients admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) at the Royal Adelaide Hospital between October 2022 and August 2023. The virus sublineages from patients were classified by the diagnostic laboratory at the hospital using RT-PCR of nasopharyngeal swab samples, with viral infections grouped into four omicron sublineages (

Figure 1a, x axis).

Nasopharyngeal swab samples from 49 patients were collected into TRIzol® reagent and were transported to QIMR Berghofer. RNA was isolated, with 38 patient samples yielding sufficient RNA (

>100 ng) for library preparation and RNA-Seq (

Table S1). Viral read counts, expressed as viral reads per million (RPM), for this patient cohort ranged across >5 logs, with levels >5000 viral RPM only seen in patients infected with BA.5 and BA.2-like sublineage viruses (

Figure 1a, yellow box). These higher viral loads were associated with age

> 64 years (see below).

RNA-Seq of 19/38 patient samples yielded sufficient spike sequence data to confirm the prior RT-PCR-based sublineage identification (

Figure 1a, black circle outlines). The variant or sublineage for four samples could not be established by either RNA-Seq (insufficient reads) or by the hospital diagnostic laboratory (

Figure 1a, Unknown).

3.2. Quantitation by RT-qPCR Correlated Well with Viral read Counts

The same purified RNA samples that were used for RNA-Seq were also analyzed by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) using the standard SARS-CoV-2 Sarbeco-E primers [

26]. Viral RPM obtained from RNA-Seq correlated well with Cq values from RT-qPCR; viral RNA quantitation by these two methods thus provided highly comparable results.

3.3. Phylogenetic Tree of Omicron Sublineages

Of the 38 samples analyzed by RNA-Seq, 19 provided sufficient spike sequence data to allow construction of a phylogenetic tree (

Figure 1c). Clear clustering of the sublineages was evident, reflecting the groupings applied in

Figure 1a. As might be expected, XBF, a recombinant of BA.5.2 and BA.2.75 [

28], grouped with the BA.2-like viruses.

3.4. Progression of Omicron Sublineages from Oct 2022 to Aug 2023

The number of patients infected with an identified sublineage was tracked month by month from Oct 2022 to Aug 2023, and is illustrated as a percentage of each sublineage per month (

Figure 1d). A clear progression was evident from BA.5 to BA.2-like to XBB-like and finally XBC (

Figure 1d), consistent with the global evolution of omicron sublineages [

2,

3,

4,

5,

29].

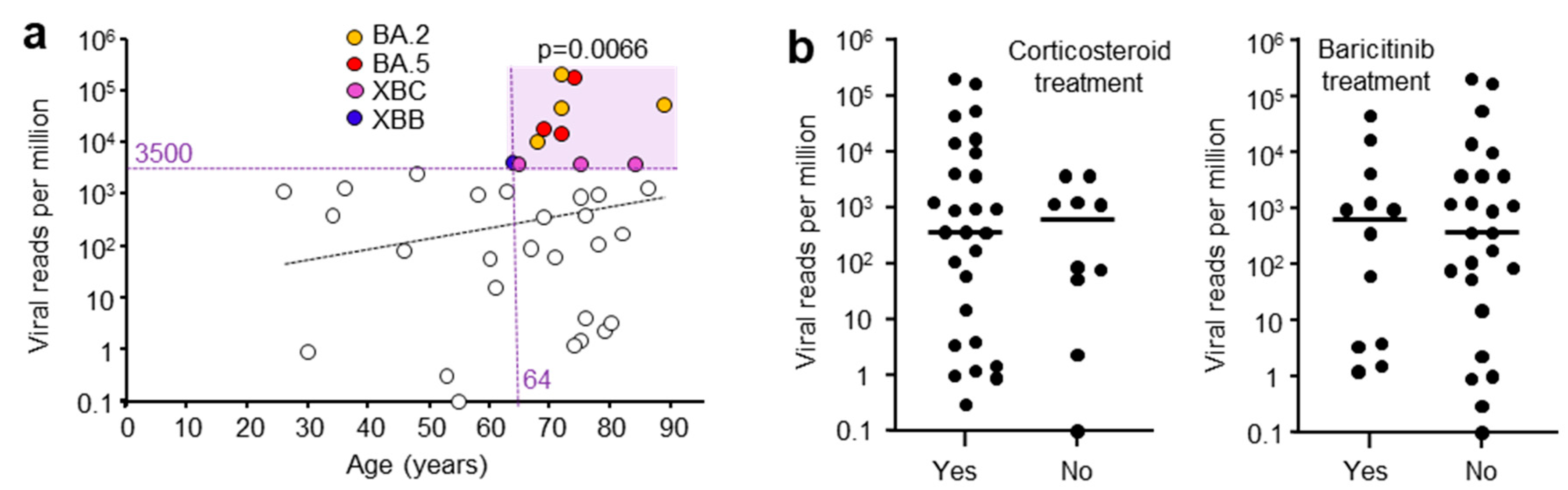

3.5. Correlations of Viral Read Counts with Age and Other Patient Data

A range of patient data were collected and potential correlates sought. High viral RPM were significantly associated with patients who were

> 64 years of age (

Figure 2a), in agreement with previous reports [

30,

31]. Corticosteroid and baricitinib (JAK inhibitor) treatment showed no significant effect on viral RPM. Corticosteroid treatment is well established for reducing mortality [

32], although a delay in viral clearance has been reported in some [

33], but not other studies [

34]. Baricitinib treatment also reduces mortality [

35] and has been reported not to affect viral clearance [

36]. All patients were treated with Remdesivir (SARS-CoV-2 antiviral).

A series of other correlations failed to show significance. Whether the patients had received a COVID-19 vaccine did not significantly influence the mean viral RPM; however, only 3 patients did not receive a vaccine (

Figure S1a). High viral RPM were associated with patients that had one or more comorbidities; however this did not reach significance, with only 5 patients free of comorbidities (

Figure S1b). Previous studies have shown that patients with high viral loads often have comorbidities [

37]. The length of stay in ICU or in hospital also did not correlate with viral RPM (

Figure S1c), consistent with previous studies [

38]. The viral RPM were not significantly different between males and females (

Figure S1d). Viral loads are generally reported to be higher in females [

39].

3.5. RNA-Seq Analysis of Human Gene Expression

There was sufficient RNA (

>100 ng) in 38/49 samples for RNA-Seq. RNA integrity number (RIN) scores ranged from 2.3 to 7.8 (mean 5.4

+ SD 1.4), illustrating that RNA in the nasopharynx, as might be expected, often suffers from a level of degradation. This is a recognized issue in many clinical samples, and can be ameliorated by depletion of ribosomal RNA, rather than enriching by poly(A) capture, prior to library generation [

40,

41]. Approximately 30 million reads were obtained for each sample with a mean of 75% aligning to the human reference genome (

Table S1), illustrating that human gene expression data can be obtained from most nasopharyngeal swabs.

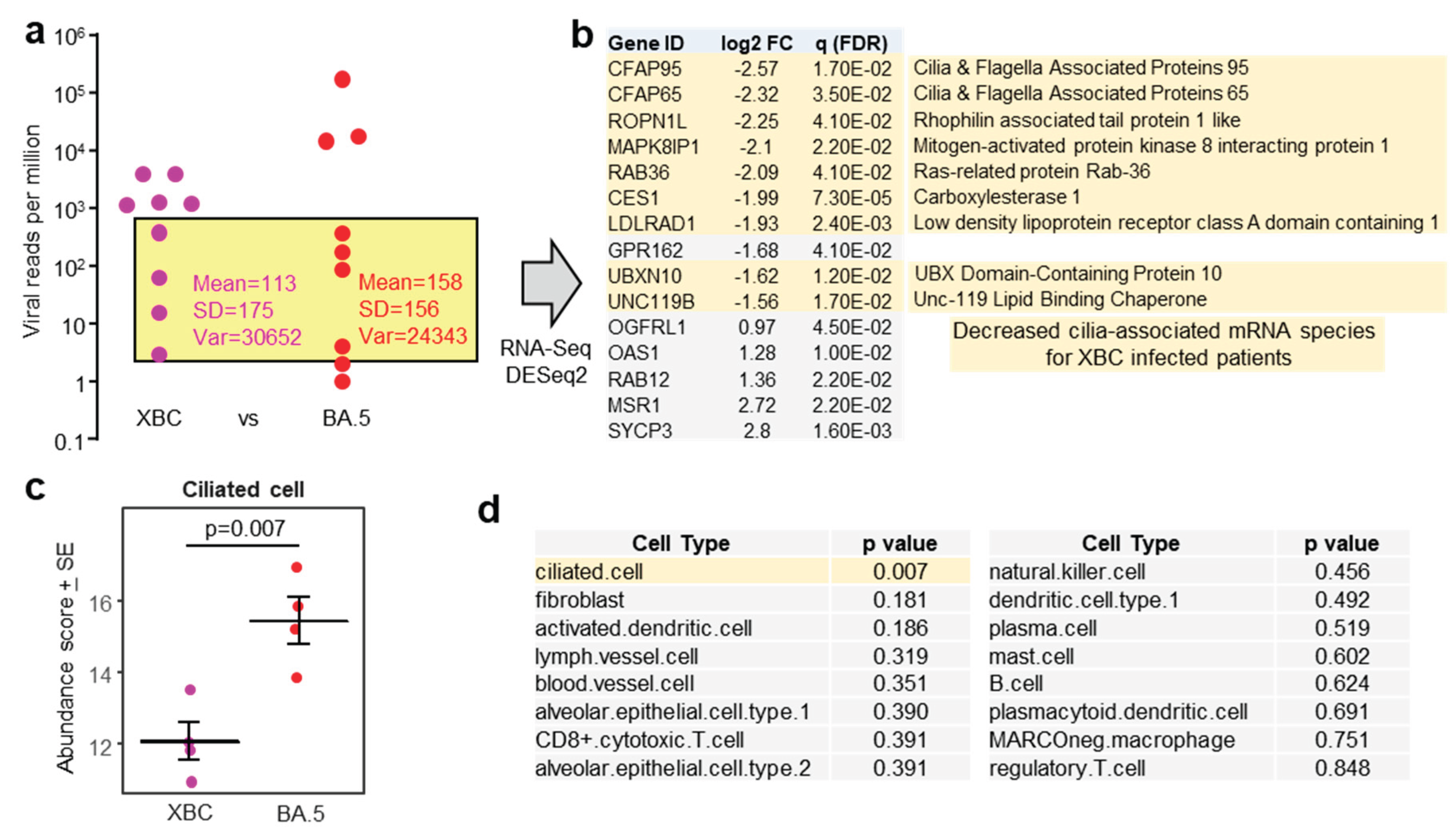

DeSeq2 was used to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) using pairwise comparisons between samples from patients infected with the different sublineages. This approach provided only a small number of DEGs for each comparison, with BA.5 vs. XBC providing the largest number of DEGs (n=43 DEGs with gene name annotations) (

Table S2). No cogent pathways were identified by

inter alia Ingenuity Pathway analysis (IPA) [

23,

42,

43]. However, the top upregulated gene was Growth and differentiation factor 15 (GDF15) (

Table S2) (a member of the TGF-β superfamily), which in COVID-19, increases with tissue damage [

44]. As the mean viral RPM was ≈17 times higher in BA.5 compared with XBC (

Figure 1a), more tissue damage might be envisioned in the BA.5-infected cohort.

To mitigate against the influence of large differences in viral loads, patient samples with comparable viral RPM were compared for human gene expression (

Figure 3a, yellow shaded box). The exclusion of samples with high and very low viral RPM, left four XBC and four BA.5 samples (

Figure 3a). These 8 samples had slightly higher RIN scores (range 3.8 - 7.8, mean 5.6

+ SD 1.2). DeSeq2 again only identified a small number of DEGs; however 9/10 of the mRNA species that were down-regulated in XBC samples were associated with cilia (

Figure 3b). This analysis argues that more ciliated epithelial cells were infected and disrupted in the nasopharynx of XBC-infected patients than in BA.5-infected patients. The genes were the cilia-associated protein CFAP95 [

45] and CFAP65 (expressed in lung [

46]), ROPN1L [

47], MAPK8IP1 [

48], RAB36 (paralog of RAB34) [

49], CES1 (highly expressed in ciliated epithelium [

50]), LDLRAD1 [

51], UBXN10 [

52] and UNC119 [

53].

Using the data from the same samples (

Figure 3a, yellow shading), but using the entire expression matrices (rather than just DEGs), cellular deconvolution analysis was undertaken to estimate the relative abundance of different cell types. Cell-type expression matrices for cells from the human nasopharynx (upper respiratory track) are not available, so cell-type expression matrices for human lung (lower respiratory track) were used. The abundance of ciliated cells emerged as significantly lower in XBC vs. BA.5 samples (

Figure 3c), consistent with the analysis of individual DEGs in

Figure 3b. Of all the cell types identified by cellular deconvolution, only the abundance of ciliated cells was significantly different between XBC and BA.5 samples (

Figure 3d).

4. Discussion

Herein we present viral and human gene expression data derived from nasopharyngeal swabs using RNA-Seq. Ribosomal depletion rather than poly(A) capture was used to ameliorate the problem of lower RNA quality (lower RIN scores, indicating some RNA degradation) [

35,

36]. The viral RPM correlated well with standard RT-qPCR viral load quantitation, providing a level of cross-validation of RT-qPCR and RNA-Seq data. High viral RPM were significantly associated with age

>64, and patients with high viral RPM also often had comorbidities, data consistent with previous studies [

30,

31,

37]. Immunosuppression with corticosteroids and/or baricitinib did not significantly influence viral RPM, results again consistent with previous studies [

34,

36]. Taken together, these data illustrate that viral RPM obtained via RNA-Seq provides reliable information on viral loads in the upper respiratory track. However, in this context RT-qPCR is currently clearly cheaper and more accessible and unlikely to be replaced by RNA-Seq.

The advantage of RNA-Seq is that it also provides gene expression data for the human host, with the data presented herein illustrating that a very respectable number of human mRNA reads can be obtained from nasopharyngeal swabs (

Table S1). The very large range in viral loads may be due to a number of factors including sampling at different times during the course of the infections, differing effectiveness of anti-viral treatment or anti-viral immunity, and/or differing levels of the initial infectious viral inoculum. Although perhaps to be expected in any cohort of virus-infected patients, such large variability complicates the ability to generate salient comparisons of human gene expression between samples from patients infected with different sublineages. Large differences in the level of virus infection will have a much greater effect on gene expression than the more subtle differences that might emerge between infections with different subvariants of the same virus. Nevertheless, we illustrate that choosing patient samples with comparable viral RPM, allows generation of human differential gene expression data that reveals information about the biology of omicron sublineages. Specifically, that XBC infection in the nasopharynx resulted in significantly lower ciliated epithelial cell mRNA signatures when compared with BA.5 infection. Conceivably, the reduction in ciliated cell signatures might be associated, at least in part, with reprograming of gene expression in the infected cells [

13]. However, XBC may simply infect and ultimately kill ciliated epithelial cells (via virus-induced cytopathic effects [

54,

55]) more efficiently than BA.5, leaving fewer of these cells available to be collected by the nasopharyngeal swabs.

5. Conclusions

RNA-Seq of human nasopharyngeal swabs provided evidence that the omicron sublineage XBC targets ciliated epithelial cells in the human upper respiratory track more effectively than BA.5. A key difference between the omicron lineage viruses and previous SARS-CoV-2 lineages was increased infection of ciliated epithelial cells in the upper respiratory track [

13,

14]. The data presented herein suggest that this evolutionary trend of increased targeting of ciliated cells continued as the omicron sublineage evolved from BA.5 to XBC.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Figure S1: Non-significant correlations with viral RPM; Table S1: RNA-Seq read data; Table S2. DEGs for pairwise comparisons between samples from different sublineages.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S., D.R.; methodology, A.S., C.R.B., M.P.P.; software, C.R.B.; formal analysis, C.R.B., A.S. A.C. ; investigation, A.C., M.P.P., E.R., S.C.B., C.M.H.; resources, B.G-B, M.P.P., A.S., D.J.R.; data curation, C.R.B., A.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.; writing—review and editing, A.S.; visualization, A.C., A.S.; supervision, D.R., A.S., B.G-B, M.P.P., W.N.; project administration, A.S., D.R., B.G-B, M.P.P.; funding acquisition, A.S., D.R., B.G-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by philanthropic donations for COVID-19 research from the Brazil Family Foundation, Australia, grant funding from The Hospital Research Foundation Group, Adelaide, Australia, and The Health Services Charitable Gifts Board, Adelaide, Australia. Prof A Suhrbier was awarded an Investigator grant by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia (APP1173880). Agnes Carolin was a recipient of a PhD scholarship & fee waiver from the Faculty of Health, Medicine and Behavioral Sciences, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Approval was obtained from the Central Adelaide Local Health Network (CALHN) Human Research Ethics Committee and CALHN Research Governance (CALHN13050). Approval was also obtained from the QIMR Berghofer Human Research Ethics Committee (Ref: P3600). All sample and patient data was deidentified.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The RNA-Seq fastq files are available from NCBI SRA BioProject ID: PRJNA1313398.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr Gunter Hartel (QIMR Berghofer) for his help with statistics. The authors wish to thank Ms Kathleen Glasby, Ms Sarah Dohery, Ms Nerissa Brown, Ms Mahni Foster, Mr Connor Christie and Ms Paola Arce-Arango for biospecimen and data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| COVID-19 |

Coronavirus Disease of 2019 |

| SARS-CoV-2 |

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| RT-qPCR |

Reverse transcriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| RNA-Seq |

Ribonucleic acid sequencing |

| mRNA |

Messenger RNA |

| RIN |

RNA integrity number |

| DEGs |

Differentially expressed genes |

| RPM |

Reads per million |

| FDR |

False discovery rate (q) |

| FC |

Fold change |

References

- Markov, P. V.; Ghafari, M.; Beer, M.; Lythgoe, K.; Simmonds, P.; Stilianakis, N. I.; Katzourakis, A., The evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2023, 21, 361-379. [CrossRef]

- Roemer, C.; Sheward, D. J.; Hisner, R.; Gueli, F.; Sakaguchi, H.; Frohberg, N.; Schoenmakers, J.; Sato, K.; O’Toole, Á.; Rambaut, A., et al., SARS-CoV-2 evolution in the Omicron era. Nature Microbiology 2023, 8, 1952-1959. [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Chan, J. F.-W.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Chen, Y.-X.; Shuai, H.; Hu, Y.-F.; Hartnoll, M.; Chen, L.; Xia, Y., et al., Divergent trajectory of replication and intrinsic pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron post-BA.2/5 subvariants in the upper and lower respiratory tract. eBioMedicine 2024, 99, 104916. [CrossRef]

- Velavan, T. P.; Ntoumi, F.; Kremsner, P. G.; Lee, S. S.; Meyer, C. G., Emergence and geographic dominance of Omicron subvariants XBB/XBB.1.5 and BF.7 - the public health challenges. Int J Infect Dis 2023, 128, 307-309. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, R. M.; Ho, J.; Mohri, H.; Valdez, R.; Manthei, D. M.; Gordon, A.; Liu, L.; Ho, D. D., Antibody neutralisation of emerging SARS-CoV-2 subvariants: EG.5.1 and XBC.1.6. Lancet Infect Dis 2023, 23, e397-e398. [CrossRef]

- Carabelli, A. M.; Peacock, T. P.; Thorne, L. G.; Harvey, W. T.; Hughes, J.; Peacock, S. J.; Barclay, W. S.; de Silva, T. I.; Towers, G. J.; Robertson, D. L., SARS-CoV-2 variant biology: immune escape, transmission and fitness. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023, 21, 162-177. [CrossRef]

- Dadonaite, B.; Brown, J.; McMahon, T. E.; Farrell, A. G.; Figgins, M. D.; Asarnow, D.; Stewart, C.; Lee, J.; Logue, J.; Bedford, T., et al., Spike deep mutational scanning helps predict success of SARS-CoV-2 clades. Nature 2024, 631, 617-626. [CrossRef]

- Steiner, S.; Kratzel, A.; Barut, G. T.; Lang, R. M.; Aguiar Moreira, E.; Thomann, L.; Kelly, J. N.; Thiel, V., SARS-CoV-2 biology and host interactions. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2024, 22, 206-225. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Gupta, D.; Bhatnagar, S., Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 genome evolutionary patterns. Microbiology Spectrum 2024, 12, e02654-23. [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, K. I.; Yang, H.; Sun, R.; Li, C.; Guo, D., The emerging role of SARS-CoV-2 nonstructural protein 1 (nsp1) in epigenetic regulation of host gene expression. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 2024, 48, fuae023. [CrossRef]

- Garcia Lopez, V.; Plate, L., Comparative Interactome Profiling of Nonstructural Protein 3 Across SARS-CoV-2 Variants Emerged During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Viruses 2025, 17, 447. [CrossRef]

- Takada, K.; Orba, Y.; Kida, Y.; Wu, J.; Ono, C.; Matsuura, Y.; Nakagawa, S.; Sawa, H.; Watanabe, T., Genes involved in the limited spread of SARS-CoV-2 in the lower respiratory airways of hamsters may be associated with adaptive evolution. Journal of Virology 2024, 98, e01784-23. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-T.; Lidsky, P. V.; Xiao, Y.; Cheng, R.; Lee, I. T.; Nakayama, T.; Jiang, S.; He, W.; Demeter, J.; Knight, M. G., et al., SARS-CoV-2 replication in airway epithelia requires motile cilia and microvillar reprogramming. Cell 2023, 186, 112-130.e20. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, B. F.; Robinot, R.; Michel, V.; Mendez, A.; Lebourgeois, S.; Chivé, C.; Jeger-Madiot, R.; Vaid, R.; Bondet, V.; Maloney, E., et al., Stealth replication of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron in the nasal epithelium at physiological temperature. bioRxiv 2025, 2025.05.03.652024. [CrossRef]

- Dumenil, T.; Le, T. T.; Rawle, D. J.; Yan, K.; Tang, B.; Nguyen, W.; Bishop, C.; Suhrbier, A., Warmer ambient air temperatures reduce nasal turbinate and brain infection, but increase lung inflammation in the K18-hACE2 mouse model of COVID-19. Sci Total Environ 2023, 859, 160163. [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Xu, R.; Li, N., The Interplay between Airway Cilia and Coronavirus Infection, Implications for Prevention and Control of Airway Viral Infections. Cells 2024, 13, 1353. [CrossRef]

- El-Daly, M. M., Advances and Challenges in SARS-CoV-2 Detection: A Review of Molecular and Serological Technologies. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 519. [CrossRef]

- Pollak, N. M.; Rawle, D. J.; Yan, K.; Buckley, C.; Le, T. T.; Wang, C. Y. T.; Ertl, N. G.; van Huyssteen, K.; Crkvencic, N.; Hashmi, M., et al., Rapid inactivation and sample preparation for SARS-CoV-2 PCR-based diagnostics using TNA-Cifer Reagent E. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 14, 1238542. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Guo, Z.; Yuan, J.; Cao, G.; Wang, Y.; Gao, P.; Liu, J.; Liu, M., Duration of viable virus shedding and polymerase chain reaction positivity of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant in the upper respiratory tract: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2023, 129, 228-235. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, R.; Yan, K.; Ellis, S. A.; Bishop, C. R.; Dumenil, T.; Tang, B.; Nguyen, W.; Larcher, T.; Parry, R.; Sng, J. J., et al., SARS-CoV-2 omicron BA.5 and XBB variants have increased neurotropic potential over BA.1 in K18-hACE2 mice and human brain organoids. Front Microbiol 2023, 14, 1320856. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Marth, G.; Abecasis, G.; Durbin, R.; Genome Project Data Processing, S., The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078-2079. [CrossRef]

- Love, M. I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S., Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome biology 2014, 15, 550. [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C. R.; Yan, K.; Nguyen, W.; Rawle, D. J.; Tang, B.; Larcher, T.; Suhrbier, A., Microplastics dysregulate innate immunity in the SARS-CoV-2 infected lung. Frontiers in Immunology 2024, 15, 1382655. [CrossRef]

- Danaher, P.; Kim, Y.; Nelson, B.; Griswold, M.; Yang, Z.; Piazza, E.; Beechem, J. M., Advances in mixed cell deconvolution enable quantification of cell types in spatial transcriptomic data. Nature Communications 2022, 13, 385. [CrossRef]

- Madissoon, E.; Wilbrey-Clark, A.; Miragaia, R. J.; Saeb-Parsy, K.; Mahbubani, K. T.; Georgakopoulos, N.; Harding, P.; Polanski, K.; Huang, N.; Nowicki-Osuch, K., scRNA-seq assessment of the human lung, spleen, and esophagus tissue stability after cold preservation. Genome biology 2019, 21, 1. [CrossRef]

- Vogels, C. B. F.; Brito, A. F.; Wyllie, A. L.; Fauver, J. R.; Ott, I. M.; Kalinich, C. C.; Petrone, M. E.; Casanovas-Massana, A.; Catherine Muenker, M.; Moore, A. J., et al., Analytical sensitivity and efficiency comparisons of SARS-CoV-2 RT–qPCR primer–probe sets. Nature Microbiology 2020, 5, 1299-1305. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J. T.; Thorvaldsdottir, H.; Turner, D.; Mesirov, J. P., igv.js: an embeddable JavaScript implementation of the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV). Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btac830. [CrossRef]

- Scarpa, F.; Locci, C.; Azzena, I.; Casu, M.; Fiori, P. L.; Ciccozzi, A.; Giovanetti, M.; Quaranta, M.; Ceccarelli, G.; Pascarella, S., et al., SARS-CoV-2 recombinants: Genomic comparison between XBF and its parental lineages. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1824. [CrossRef]

- Chhoung, C.; Ko, K.; Ouoba, S.; Phyo, Z.; Akuffo, G. A.; Sugiyama, A.; Akita, T.; Sasaki, H.; Yamamoto, T.; Takahashi, K., et al., Sustained applicability of SARS-CoV-2 variants identification by Sanger Sequencing Strategy on emerging various SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variants in Hiroshima, Japan. BMC Genomics 2024, 25, 1063. [CrossRef]

- To, K. K.-W.; Tsang, O. T.-Y.; Leung, W.-S.; Tam, A. R.; Wu, T.-C.; Lung, D. C.; Yip, C. C.-Y.; Cai, J.-P.; Chan, J. M.-C.; Chik, T. S.-H., et al., Temporal profiles of viral load in posterior oropharyngeal saliva samples and serum antibody responses during infection by SARS-CoV-2: an observational cohort study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2020, 20, 565-574. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Yang, X.; Jiang, X.; Duan, Z.; Wang, W.; Sun, Z.; Chen, W.; Zhang, W.; Xu, J.; Cheng, J., et al., Factors associated with prolonged viral shedding in older patients infected with Omicron BA.2.2. Frontiers in Public Health 2023, 10, 1087800. [CrossRef]

- Johns, M.; George, S.; Taburyanskaya, M.; Poon, Y. K., A Review of the Evidence for Corticosteroids in COVID-19. Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2021, 35, 626-637. [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Zhu, C.; Jian, W.; Xue, L.; Li, C.; Yan, X.; Huang, S.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, L.; Xu, T., et al., Corticosteroid therapy is associated with the delay of SARS-CoV-2 clearance in COVID-19 patients. European Journal of Pharmacology 2020, 889, 173556. [CrossRef]

- Spagnuolo, V.; Guffanti, M.; Galli, L.; Poli, A.; Querini, P. R.; Ripa, M.; Clementi, M.; Scarpellini, P.; Lazzarin, A.; Tresoldi, M., et al., Viral clearance after early corticosteroid treatment in patients with moderate or severe covid-19. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 21291. [CrossRef]

- Patanwala, A. E.; Xiao, X.; Hills, T. E.; Higgins, A. M.; McArthur, C. J.; Alexander, G. C.; Mehta, H. B.; on behalf of National Covid Cohort Collaborative, C., Comparative Effectiveness of Baricitinib Versus Tocilizumab in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19: A Retrospective Cohort Study of the National Covid Collaborative. Critical Care Medicine 2025, 53, e29-41. [CrossRef]

- Viermyr, H.-K.; Tonby, K.; Ponzi, E.; Trouillet-Assant, S.; Poissy, J.; Arribas, J. R.; Dyon-Tafani, V.; Bouscambert-Duchamp, M.; Assoumou, L.; Halvorsen, B., et al., Safety of baricitinib in vaccinated patients with severe and critical COVID-19 sub study of the randomised Bari-SolidAct trial. eBioMedicine 2025, 111, 105511. [CrossRef]

- Maltezou, H. C.; Raftopoulos, V.; Vorou, R.; Papadima, K.; Mellou, K.; Spanakis, N.; Kossyvakis, A.; Gioula, G.; Exindari, M.; Froukala, E., et al., Association Between Upper Respiratory Tract Viral Load, Comorbidities, Disease Severity, and Outcome of Patients With SARS-CoV-2 Infection. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 2021, 223, 1132-1138. [CrossRef]

- Cocconcelli, E.; Castelli, G.; Onelia, F.; Lavezzo, E.; Giraudo, C.; Bernardinello, N.; Fichera, G.; Leoni, D.; Trevenzoli, M.; Saetta, M., et al., Disease Severity and Prognosis of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Hospitalized Patients Is Not Associated With Viral Load in Nasopharyngeal Swab. Frontiers in Medicine 2021, 8, 714221. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wen, R.; Wang, N.; Li, G.; Xu, P.; Li, X.; Zeng, X.; Liu, C., A retrospective study on COVID-19 infections caused by omicron variant with clinical, epidemiological, and viral load evaluations in breakthrough infections. International Journal of Medical Sciences 2024, 21, 454. [CrossRef]

- Ura, H.; Niida, Y., Comparison of RNA-Sequencing Methods for Degraded RNA. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 6143. [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, Y., Impact of RNA degradation on next-generation sequencing transcriptome data. Genomics 2022, 114, 110429. [CrossRef]

- Carolin, A.; Frazer, D.; Yan, K.; Bishop, C. R.; Tang, B.; Nguyen, W.; Helman, S. L.; Horvat, J.; Larcher, T.; Rawle, D. J., et al., The effects of iron deficient and high iron diets on SARS-CoV-2 lung infection and disease. Frontiers in Microbiology 2024, 15, 1441495. [CrossRef]

- Carolin, A.; Yan, K.; Bishop, C. R.; Tang, B.; Nguyen, W.; Rawle, D. J.; Suhrbier, A., Tracking inflammation resolution signatures in lungs after SARS-CoV-2 omicron BA.1 infection of K18-hACE2 mice. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0302344. [CrossRef]

- Rochette, L.; Zeller, M.; Cottin, Y.; Vergely, C., GDF15: an emerging modulator of immunity and a strategy in COVID-19 in association with iron metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2021, 32, 875-889. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J. S.; Vijayakumaran, A.; Godbehere, C.; Lorentzen, E.; Mennella, V.; Schou, K. B., Uncovering structural themes across cilia microtubule inner proteins with implications for human cilia function. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 2687. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Tu, C.; Nie, H.; Meng, L.; Li, Y.; Yuan, S.; Zhang, Q.; Du, J.; Wang, J.; Gong, F., et al., Biallelic mutations in CFAP65 lead to severe asthenoteratospermia due to acrosome hypoplasia and flagellum malformations. J Med Genet 2019, 56, 750-757. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, T.; Ruan, L.; Zhu, D.; He, Y.; Jia, J.; Chen, Y., Cilia Plays a Pivotal Role in the Hypersecretion of Airway Mucus in Mice. Current Molecular Pharmacology 2024, 17, E18761429368288. [CrossRef]

- Verhey, K. J.; Hammond, J. W., Traffic control: regulation of kinesin motors. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2009, 10, 765-777. [CrossRef]

- Ganga, A. K.; Kennedy, M. C.; Oguchi, M. E.; Gray, S.; Oliver, K. E.; Knight, T. A.; De La Cruz, E. M.; Homma, Y.; Fukuda, M.; Breslow, D. K., Rab34 GTPase mediates ciliary membrane formation in the intracellular ciliogenesis pathway. Curr Biol 2021, 31, 2895-2905.e7. [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Liclican, A.; Xu, Y.; Pitts, J.; Niu, C.; Zhang, J.; Kim, C.; Zhao, X.; Soohoo, D.; Babusis, D., et al., Key Metabolic Enzymes Involved in Remdesivir Activation in Human Lung Cells. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2021, 65, 10.1128/aac.00602-21. [CrossRef]

- Geremek, M.; Bruinenberg, M.; Ziętkiewicz, E.; Pogorzelski, A.; Witt, M.; Wijmenga, C., Gene expression studies in cells from primary ciliary dyskinesia patients identify 208 potential ciliary genes. Human Genetics 2011, 129, 283-293. [CrossRef]

- Raman, M.; Sergeev, M.; Garnaas, M.; Lydeard, J. R.; Huttlin, E. L.; Goessling, W.; Shah, J. V.; Harper, J. W., Systematic proteomics of the VCP–UBXD adaptor network identifies a role for UBXN10 in regulating ciliogenesis. Nature Cell Biology 2015, 17, 1356-1369. [CrossRef]

- Jean, F.; Pilgrim, D., Coordinating the uncoordinated: UNC119 trafficking in cilia. European Journal of Cell Biology 2017, 96, 643-652. [CrossRef]

- Tanneti, N. S.; Patel, A. K.; Tan, L. H.; Marques, A. D.; Perera, R. A. P. M.; Sherrill-Mix, S.; Kelly, B. J.; Renner, D. M.; Collman, R. G.; Rodino, K., et al., Comparison of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern in primary human nasal cultures demonstrates Delta as most cytopathic and Omicron as fastest replicating. mBio 2024, 15, e03129-23. [CrossRef]

- Zaderer, V.; Abd El Halim, H.; Wyremblewsky, A.-L.; Lupoli, G.; Dächert, C.; Muenchhoff, M.; Graf, A.; Blum, H.; Lass-Flörl, C.; Keppler, O. T., et al., Omicron subvariants illustrate reduced respiratory tissue penetration, cell damage and inflammatory responses in human airway epithelia. Frontiers in Immunology 2023, 14, 1258268. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).