1. Introduction

Apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide 3B (APOBEC3B) is a member of the 11-protein APOBEC family of cytidine deaminases. All APOBEC family members share a conserved cytidine deaminase domain [

1], characterized by the conserved His-X-Glu-X

23-28-Pro-Cys-X

2-4-Cys consensus sequence [

2,

3], and are believed to have evolved through a series of duplication events and subsequent diversifications [

1]. The seven member APOBEC3 sub-family is clustered in tandem on chromosome 22q13.1 [

1], and consists of both single-domain (APOBEC3A, APOBEC3C, APOBEC3H) and double-domain (APOBEC3B, APOBEC3DE, APOBEC3F, APOBEC3G) proteins [

4]. While the C-terminal deaminase domain (CTD or CD2) catalyzes cytidine deamination, the N-terminal deaminase domain (NTD or CD1), though catalytically inactive, enhances substrate binding and deamination efficiency [

1,

5,

6].

The APOBEC3 sub-family gained prominence in the early 2000s when it was discovered that they can function as intrinsic antiviral factors against Human Immunodeficiency Virus infection [

7]. Initially, this anti-HIV function was primarily thought to result from the catalytic cytosine-to-uracil mutations on HIV cDNA [

8], but it was later determined that APOBEC3s have both deamination-dependent and deamination-independent mechanisms for restricting retro-viral infection [

9]. Additionally, it soon became clear that, in addition to HIV, APOBEC3s played a role in restricting other retroviruses and para-retroviruses such as Human T Cell Lymphotropic Virus 1 [

10,

11], and Hepatitis B Virus [

12,

13]; single-stranded DNA viruses such as Parvovirus [

14,

15]; and double-stranded DNA viruses such as Human Papillomavirus [

16,

17]. Herpes viruses such as Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) [

18], Kaposi’s Sarcoma Herpes Virus [

19], Cytomegalovirus [

20,

21], and Herpes Simplex virus [

22] have all been shown to upregulate APOBEC expression. Moreover, several herpesviruses (such as EBV) use the viral-encoded ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) large subunit to bind to A3B active site, leading to the inactivation of A3B deaminase activity and the relocalization from the nucleus to the cytoplasm [

23].

While APOBEC3s are known for their antiviral roles, APOBEC3-mediated mutation of viral DNA in polyomavirus and HIV is reported to provide evolutionary fuel for the viruses, allowing them to escape immune detection in vivo [

24,

25]. Recently, cell culture experiments have shown that APOBEC3A-mediated mutations of viral RNA promote Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) infectivity and fitness [

26]. However, no studies have yet described a deamination-independent, proviral role for APOBEC proteins.

Recently, a study showed that APOBEC3B (A3B) uses a deaminase-independent anti-viral mechanism to restrict Sendai virus (SeV) [

27]. After SeV infection, A3B was shown to activate protein kinase R that phosphorylates eIF2⍺ to repress protein translation [

28]. By doing so, A3B promotes a cellular anti-viral pathway that down-regulates total protein synthesis to reduce the expression of viral proteins [

29]. Interestingly, previous studies have shown that several viruses, including SARS-CoV-2 [

30,

31,

32], Zika and Dengue viruses [

33], are able to take advantage of non-canonical translation initiation pathways, allowing these viruses to avoid translation repression caused by PKR-induced eIF2⍺ phosphorylation.

In addition to PKR-mediated translational repression, SARS-CoV-2 has been shown to hijack host nucleotide biosynthesis and inflammatory response pathways to promote viral infectivity [

34]. Qin et al. [

34] showed that SARS-CoV-2 NSP9 promotes

de novo purine synthesis, building upon a previous finding that SARS-CoV-2 infection dysregulates purine metabolism and is significantly associated with cytokine release in COVID-19 patients [

35]. More specifically, they found that COVID-19 patients had significantly increased serum AMP levels and that these were positively correlated with Cytokine Release Syndrome (CRS)-related cytokines IL-10 and IL-18, which displayed progressive increases from healthy controls to mild and severe patients [

35]. From these studies, it appears that SARS-CoV-2 hijacks host metabolism to increase flux through the purine

de-novo biosynthesis pathway while altering purinergic signaling to increase pro-inflammatory cytokine release.

Geneformer [

36,

37] is a context-aware, attention-based deep learning model, representing a state-of-the-art tool in the burgeoning field of context-specific network biology. Leveraging a massive pre-training database of over 95 million single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-Seq) transcriptomes across diverse cellular and pathological contexts [

37], Geneformer predicts gene network dynamics under previously unseen conditions. The model can either be fine-tuned on new datasets for specialized predictive tasks or used “out of the box” for multiple analyses. One of its most powerful features is its in-silico perturbation analysis, in which a gene’s expression can be up- or down-regulated (in silico) within a specific experimental or clinical context. Using its pretraining knowledge, Geneformer predicts transcriptome-wide changes in gene embeddings, where larger shifts in cosine similarity indicate stronger regulatory effects. This function was previously used to predict genes whose perturbation could shift diseased cardiomyocytes toward a healthy state [

36]. Subsequent CRISPR-mediated knockouts validated these predictions, demonstrating restoration of cardiomyocyte contractility and disease phenotype rescue [

36].

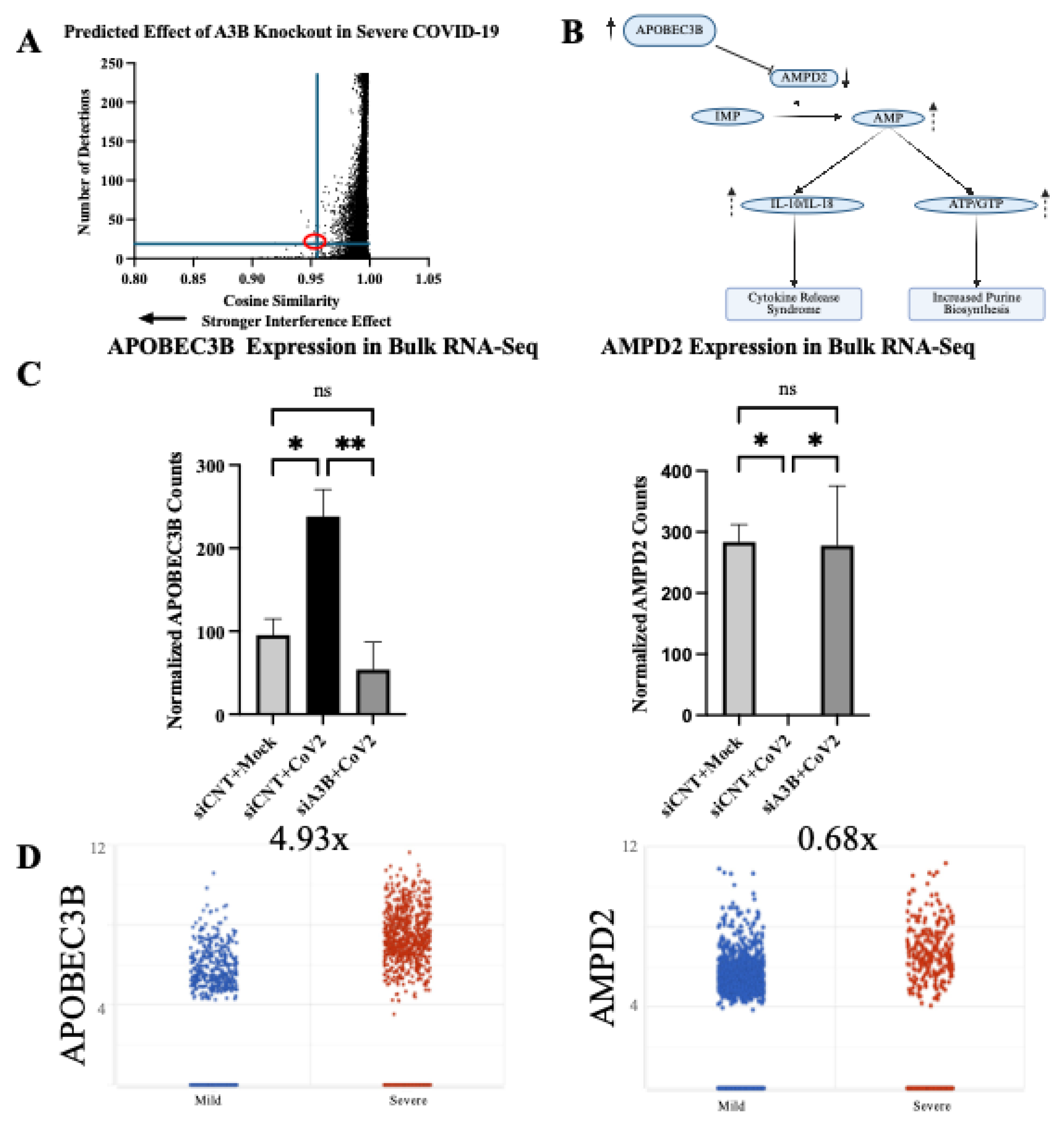

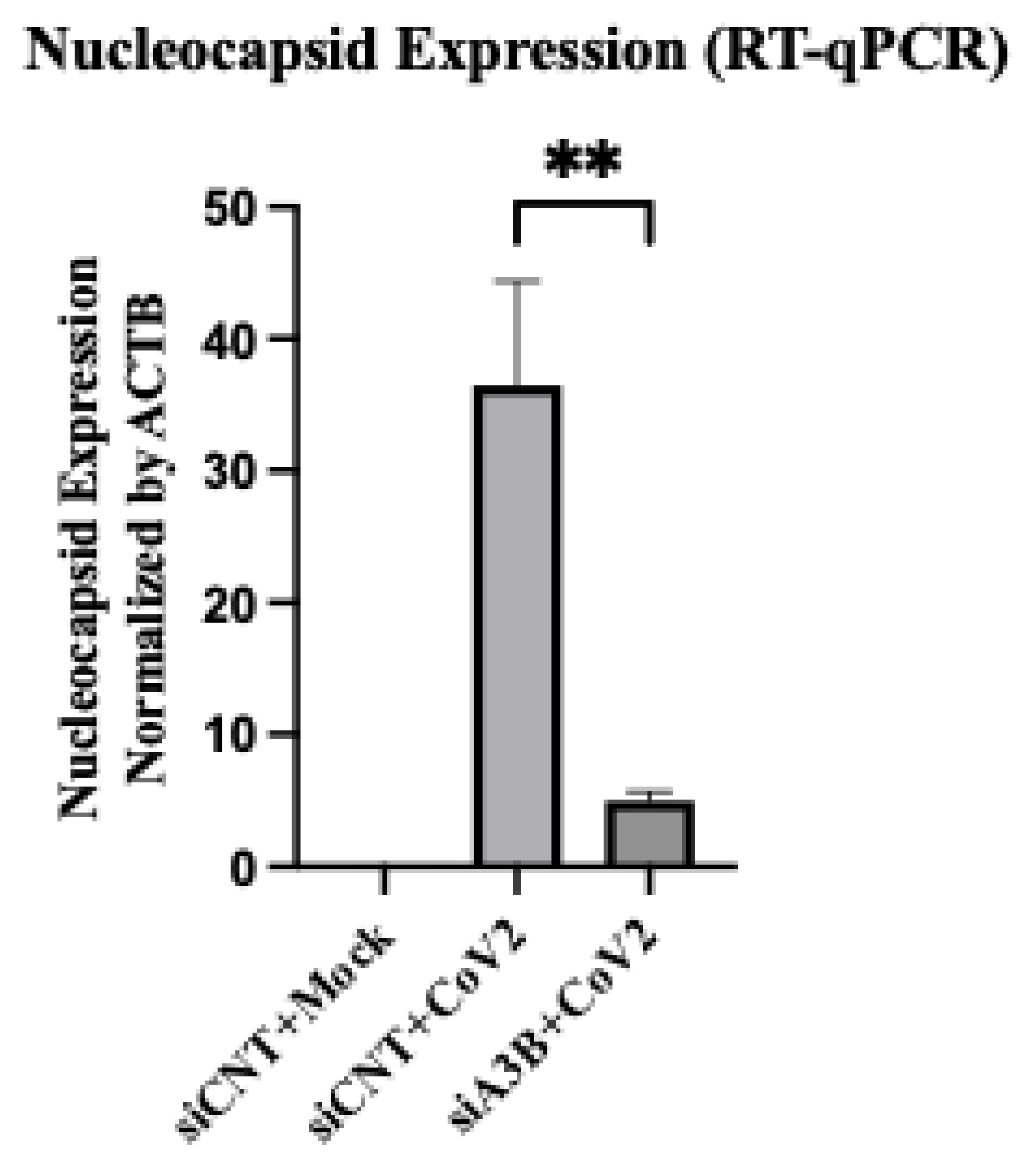

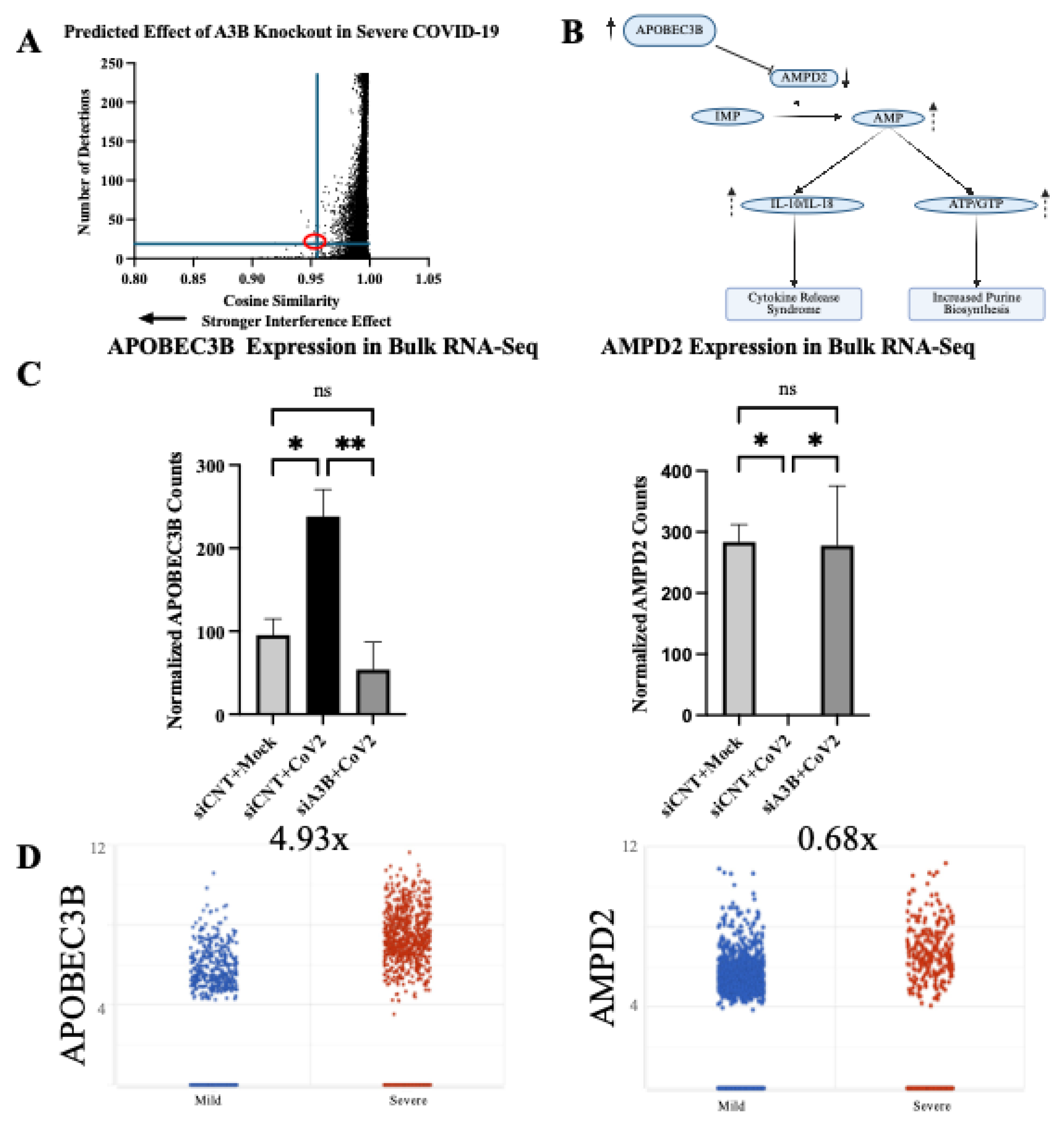

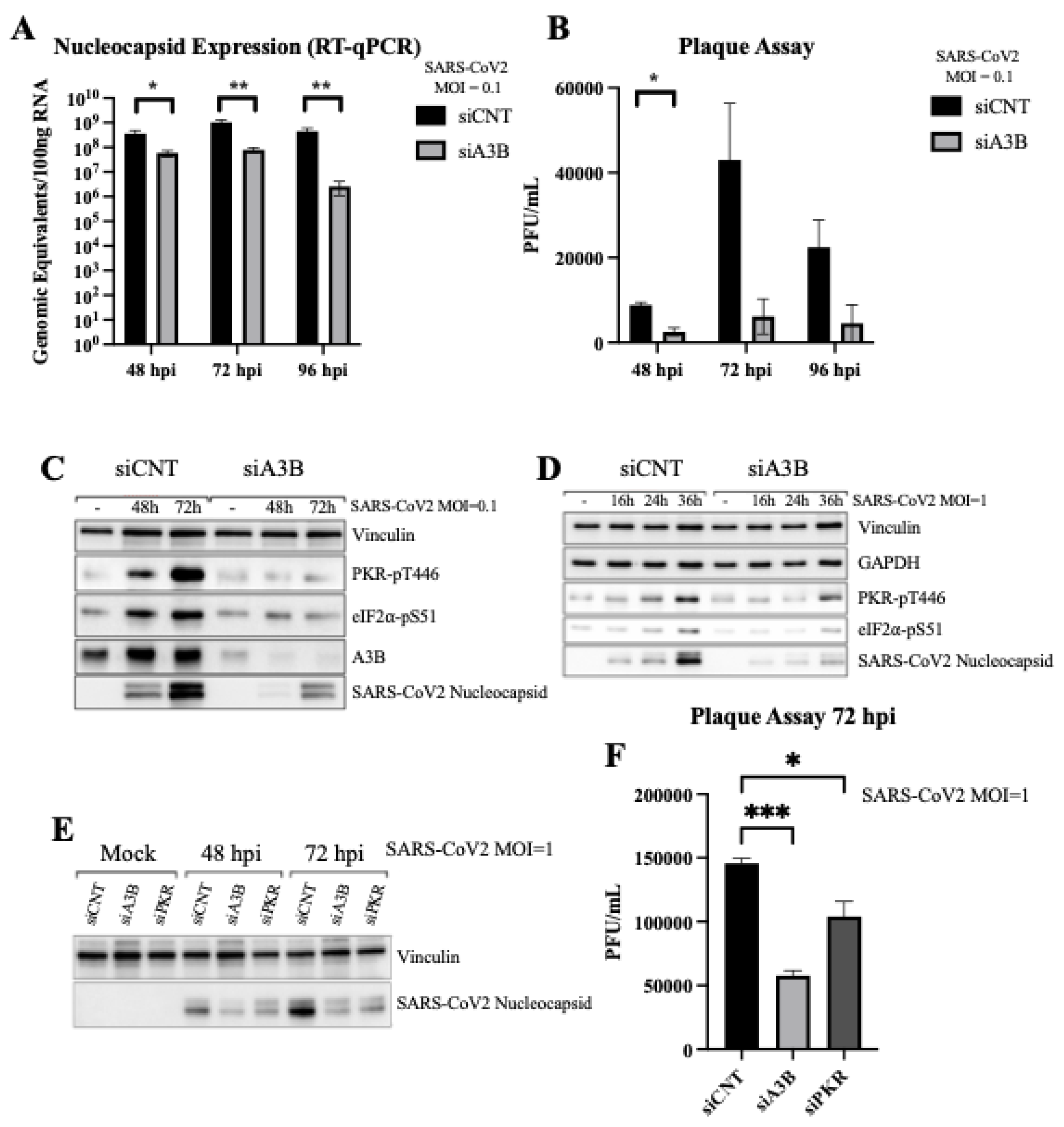

In this study, we present the first evidence of a proviral role for endogenous A3B, demonstrating that it enhances SARS-CoV-2 infectivity in two different cell lines, proposing two distinct mechanisms for the proviral activity of A3B. Specifically, we show that 1) SARS-CoV-2 infection activates the PKR/eIF2⍺ pathway in Caco-2 cells, and this activation of PKR/eIF2⍺ pathway is A3B dependent, resulting in promoting viral replication. 2) Using Geneformer, we predict a potential mechanism in which A3B knockdown triggers a compensatory upregulation of Adenosine Monophosphate Deaminase 2 (AMPD2), thereby possibly altering purinergic inflammatory signaling and purine nucleotide biosynthesis, reducing SARS-CoV-2 infectivity. These findings provide a potential paradigm shift in our understanding of A3B’s role in viral pathogenesis and suggest potential new therapeutic strategies targeting A3B-related translational, inflammatory, and metabolic pathways.

3. Discussion

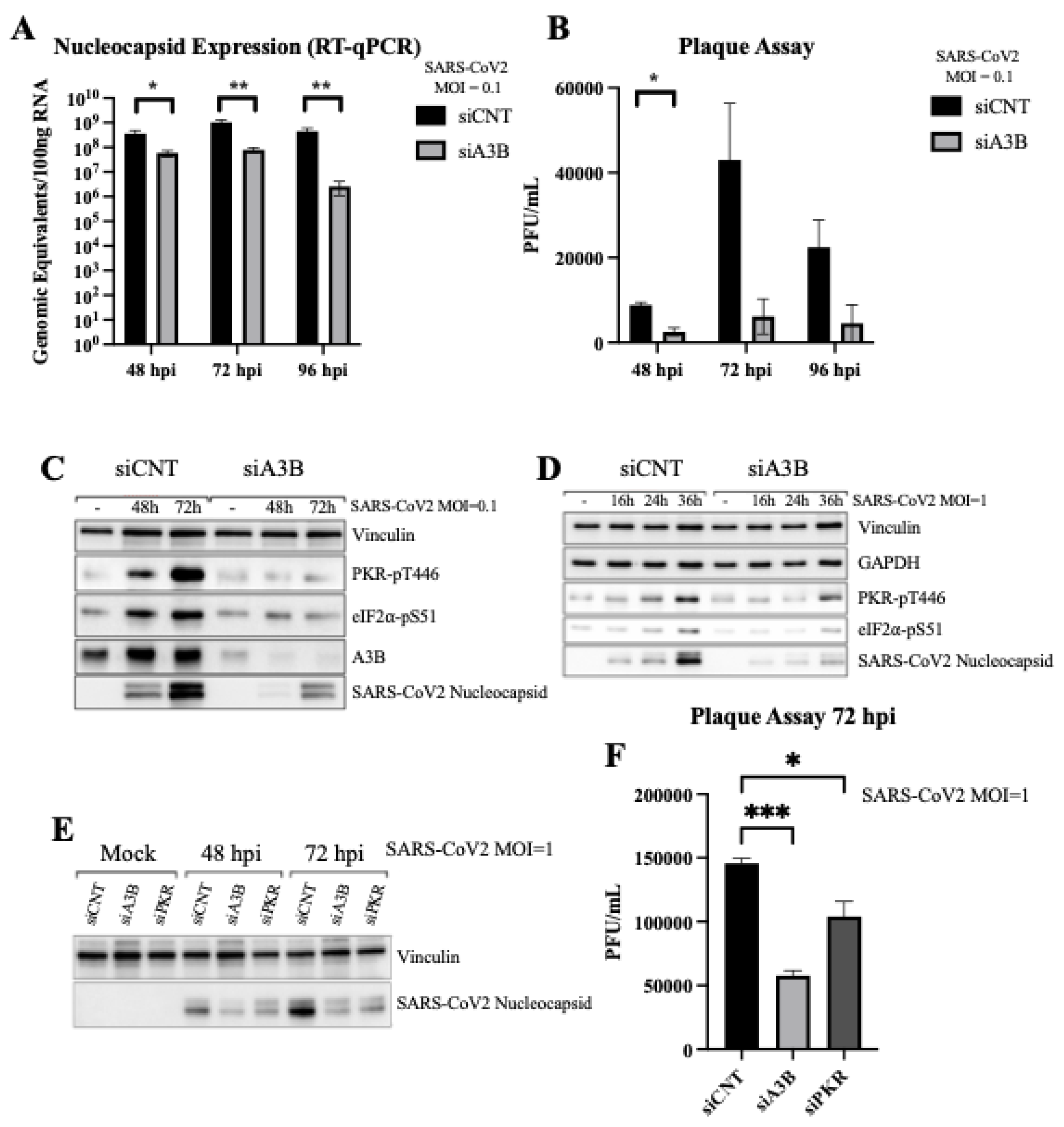

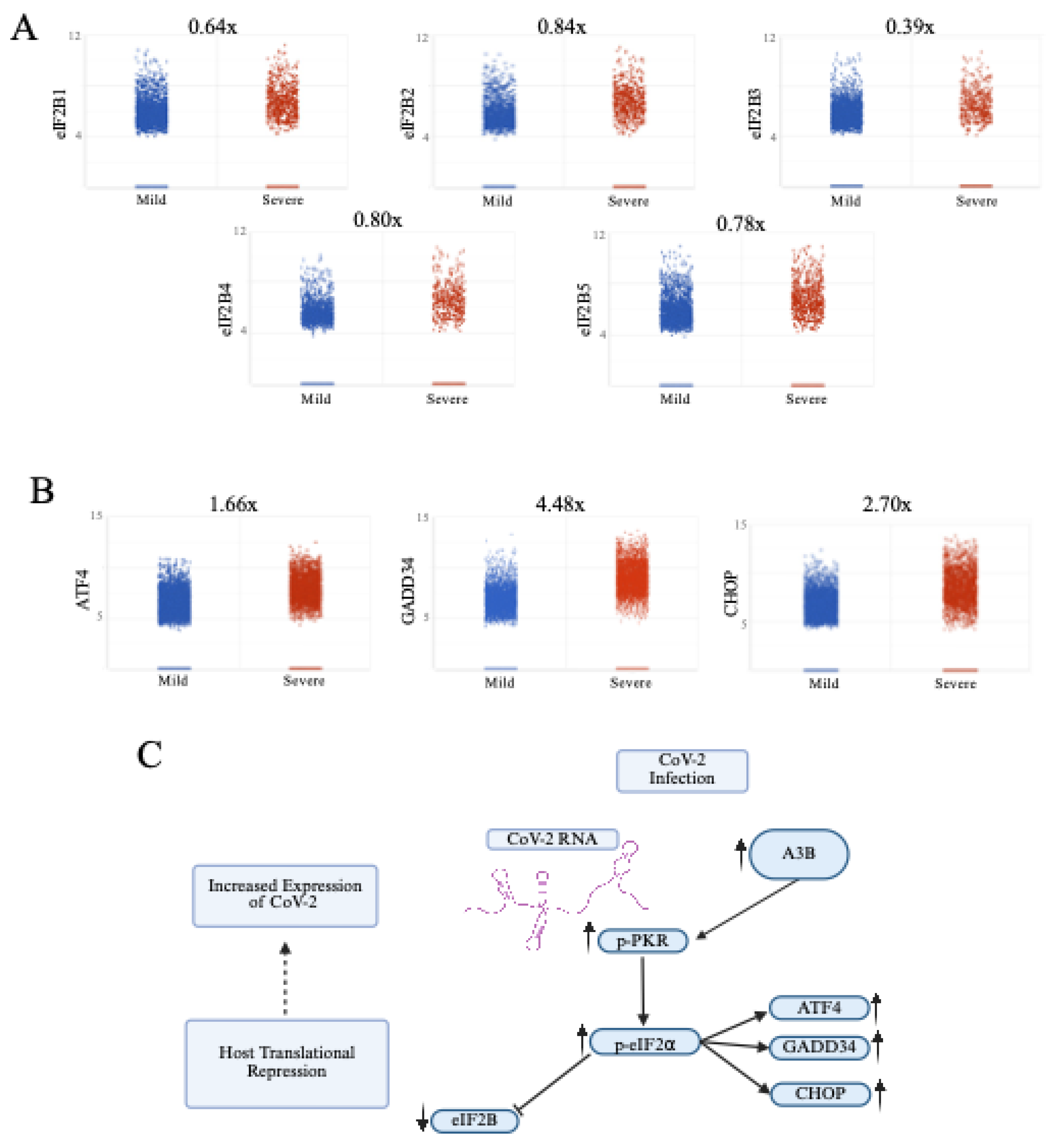

Previously, endogenous A3B has only been shown to play an antiviral role. We report here that SARS-CoV-2 infection upregulates A3B expression, which in turn enhances the viral replication and infectivity. The mechanisms for the proviral activity of A3B for SARS-CoV-2 infection are cell-type dependent, which showed either PKR/eIF2⍺ pathway dependent in Caco-2 or independent in A549-ACE2. Our studies suggest two possible mechanisms: (1) In Caco-2, increased A3B drives the activation of the PKR/eIF2⍺ pathway to downregulate host protein translation, which is considered a classical antiviral response [

27]. However, SARS-CoV-2 infection is not inhibited with the activation of this pathway, instead SARS-CoV-2 exploits this pathway, likely to selectively enhance translation of its own viral proteins [

30]. (2) In A549-ACE2, infection-mediated increased A3B did not activate PKR/eIF2⍺ pathway. Rather, it appears to suppress AMPD2 expression, possibly leading to the elevated purine nucleotide synthesis and altered anti-inflammatory purinergic signaling, contributing to cytokine release syndrome and worsening disease severity in COVID-19 patients.

Our finding that SARS-CoV-2 infection induces high levels of A3B expression, driving the activation of the p-PKR/p-eIF2⍺ stress response which is hijacked by the virus for its own benefit provides an example of novel APOBEC/virus interaction. Here, we demonstrate that A3B’s ability to drive p-PKR/p-eIF2⍺ [

27], is actually co-opted by SARS-CoV-2 to promote viral infectivity and gene expression, likely through the use of SARS-CoV-2’s non-canonical translation initiation pathways [

30,

31]. Because new viral strains are emerging frequently, it is important to identify host proviral factors whose inhibition may be used as an antiviral pharmacological treatment strategy in multiple cases. This study identifies A3B as a potentially druggable target for treating SARS-CoV-2 and potentially other viruses, yet to be discovered, that rely on the same mechanism to promote infectivity.

Notably, we utilized Geneformer to generate a hypothesis in a scenario where the underlying mechanism remained elusive. Geneformer predicted that A3B knockout in the context of severe SARS-CoV-2 infection would dysregulate AMPD2 expression. Previous studies [

34,

35] support the role of AMPD2 and purine biosynthesis in SARS-CoV-2 infection and disease severity. To validate Geneformer’s prediction, we performed bulk RNA-Sequencing and differential gene expression analysis, comparing mock-infected, control-infected, and A3B knockdown-infected cells. We found that SARS-CoV-2 infection significantly reduced AMPD2 expression, supporting previous findings demonstrating an increased flux through the

de novo purine biosynthesis pathway during SARS-CoV-2 infection [

34]. Validating Geneformer’s prediction, A3B knockdown restored AMPD2 expression during SARS-CoV-2 infection.

AMPD2 is an anti-inflammatory gene previously shown to be downregulated during severe COVID-19 infection [

42]. AMPD2 catalyzes the conversion of extra-cellular adenosine-monophosphate (AMP), a molecule implicated in inflammation, into inosine monophosphate (IMP) [

43]. Given that elevated AMP levels correlate with increased inflammatory cytokines (IL-10 and IL-18) during COVID-19 infection [

35], decreased AMPD2 may exacerbate disease pathology by allowing AMP accumulation [

34], thereby driving excessive cytokine release. We propose that high A3B expression induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection may suppress AMPD2 expression, given A3B’s role in inflammation modulation. Specifically, elevated A3B expression occurs in response to viral infection and inflammatory signaling, potentially repressing AMPD2 to further increase AMP accumulation and subsequent cytokine release. This mechanism suggests a potential positive-feedback loop wherein SARS-CoV-2 infection elevates A3B via inflammatory signaling (such as JAK1/STAT3/NF-κB) [

44,

45,

46], resulting in further amplification of the cytokine storm observed in severe COVID-19 cases. Such feedback loop aligns with previous studies showing the IL-6/JAK1/STAT3 pathway enhance A3B expression [

47], which itself stabilizes IL-6 mRNA [

48], intensifying inflammatory signaling pathways and functioning to help drive a pro-inflammatory response.

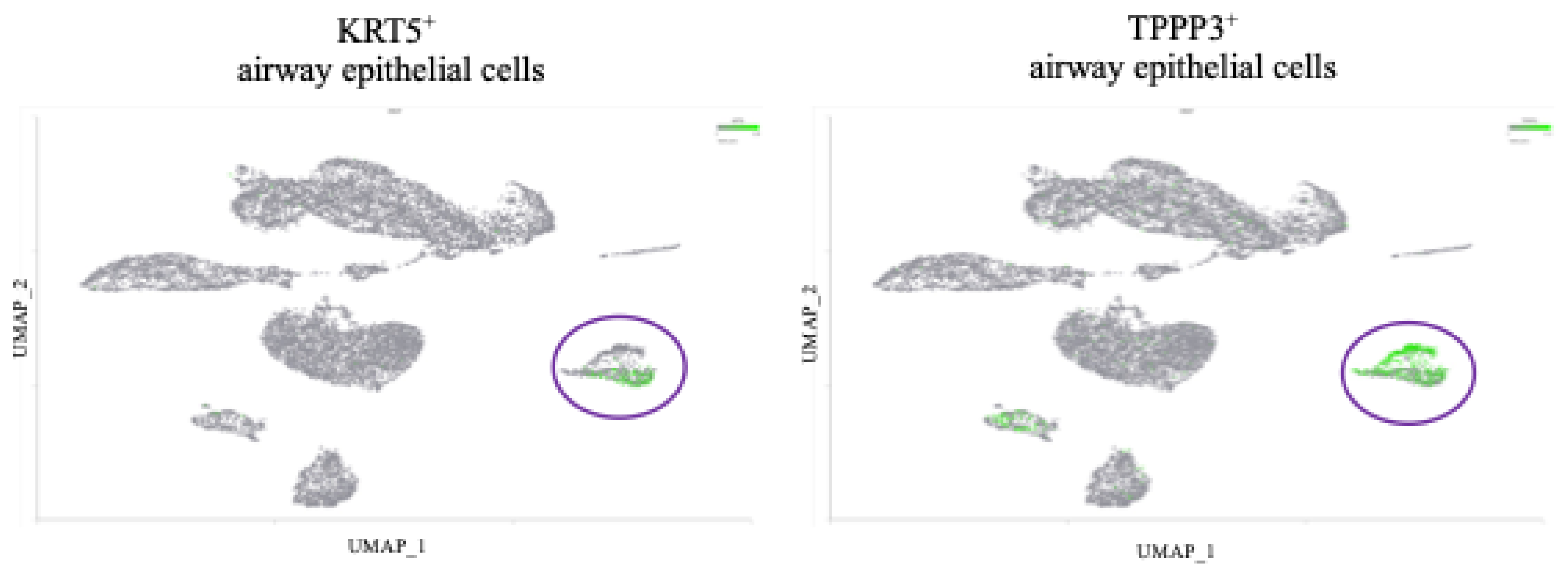

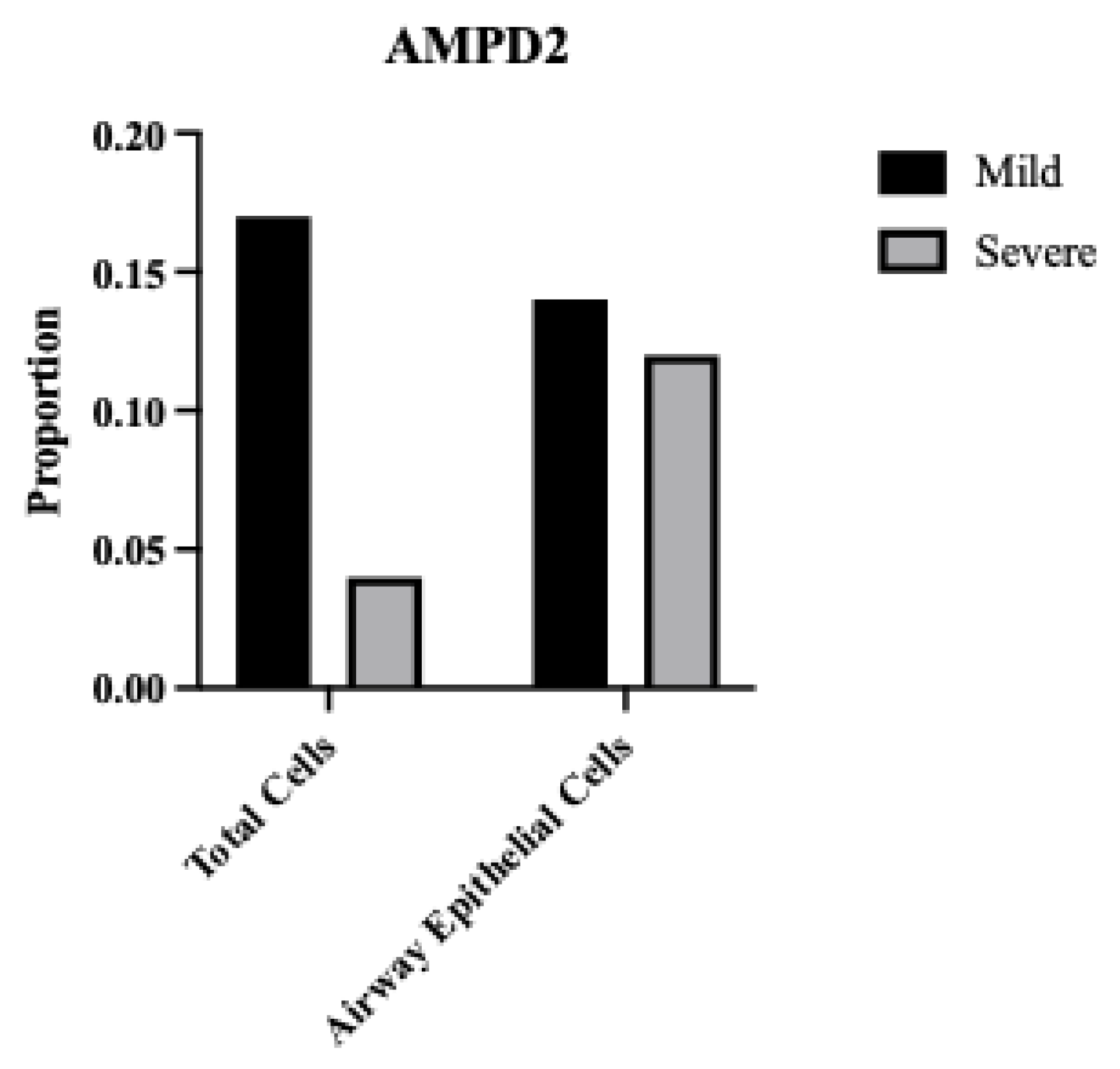

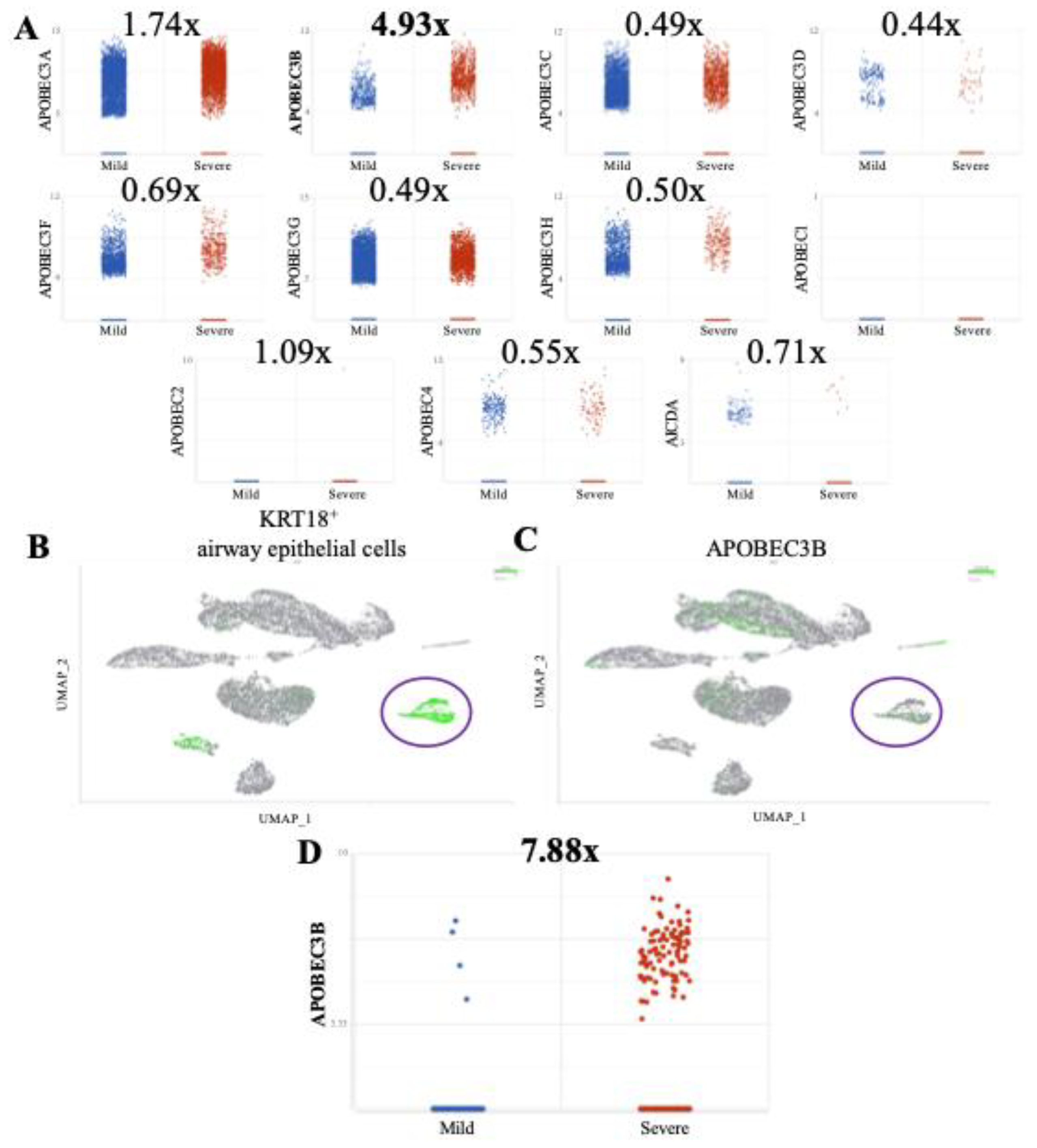

To explore a potential relationship between A3B and AMPD2, we examined scRNA-Sequencing data from BALF of severe and mild COVID-19 patients. We observed a trend toward elevated A3B expression and reduced AMPD2 expression in severe cases relative to mild infection. While this pattern does not establish causality, it raises the hypothesis of a possible inverse relationship between these two genes in the context of SARS-CoV-2 infection. By applying Geneformer, we generated preliminary insights into a candidate gene network that would have been challenging to identify using traditional next generation sequencing analysis methods. However, the underlying mechanisms driving this putative relationship remain unclear and will require future experimental validation and mechanistic investigation.

Given our novel finding that SARS-CoV-2 infection induces A3B expression, which in turn promotes SARS-CoV-2 infectivity, we speculate on its potential implications for long-haul COVID-19 patients. A3B is a well-established source of DNA mutagenesis and is implicated in tumor evolution [

49,

50,

51]. Prolonged A3B expression, particularly in the setting of chronic inflammation, can result in clustered hypermutation signatures known as

kataegis [

52,

53]

, a mutational process associated with cancer progression. Because of the known risks of prolonged A3B activity, long COVID-19 patients should be monitored for potential immune cell and lung cancers displaying the A3B mutational signature [

50,

54]. Future studies should investigate whether persistent A3B upregulation in post-COVID-19 patients contributes to an increased risk of malignancy and whether targeting A3B activity could serve as a potential therapeutic intervention in severe COVID-19 patients.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture

Cells were cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere using a ThermoScientific™ Forma Series II Water Jacket CO2 Incubator. Caco-2 (ATCC-#HTB-37) were maintained in Eagle’s Minimum Essential Media (EMEM) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (PS) (Gibco-#15140122). A549-ACE2 (BEI-#NR53821) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) containing 4.5g/L glucose, L-glutamine, and sodium pyruvate; supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% P/S, and 100µg/µL blasticidin. Vero-e6-ACE2 cells were cultured in DMEM containing 4.5g/L glucose, L-glutamine, and sodium pyruvate; supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% P/S, and 2.5µg/mL puromycin.

4.2. RNA Interference

Small-interfering RNA (siRNA) was purchased from ThermoFisher under the

Silencer-Select product line (siRNA sequences and catalog numbers are available in

Supplementary Table S3). For each gene knockdown, two siRNAs were used per target gene to ensure effective knockdown. Cells were seeded into 6- or 12-well plates and transfected with 10µM siRNA using Lipofectamine RNAiMax (Thermo Fisher, #13778150) in Opti-MEM™ and antibiotic-free media 2 days prior to infection. After 1 day, media was replaced with standard culture media, and cells were incubated until infection.

4.3. SARS-CoV-2 Virus Infections

SARS-CoV-2 USA-WA1/2020 was obtained from University of Southern California (BSL3 Core) and was originally gifted from BEI Resources (NR-52281). All SARS-CoV-2 stock virus production, infection, and titration were performed as previously described, [

26] with some modifications. All work with SARS-CoV-2 was conducted within the BSL-3 Laboratories at USC. Vero E6-hACE2 cells were used for SARS-CoV-2 stock propagation. Cells were seeded at 3x10 [

6] cells in a T75 flask for 24 hours before infection with SARS-CoV-2 (plaque isolate USA-WA1/2020) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.005. Virus-containing supernatant was collected approximately 72 hours post infection (hpi).

Virus was titrated by plaque assay, as previously described. [

26] Vero E6-hACE2 cells were seeded in 6-well plates, and once cultures reached 100% confluence, they were infected with serially diluted SARS-CoV-2 virus stock (500µL per well). After 60 minutes of incubation on a gentle shaker in the cell-culture incubator, the media was removed, and the cells were overlaid with a medium containing FBS-free DMEM and 1% low-melting-point agarose (Gibco #12100-046). After plaque formation around 72 hpi, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) overnight at room temperature. Solid DMEM-agarose was removed, and cells were stained with 0.2% crystal violet. Plaques were counted on a lightbox to determine viral titers.

Caco-2, A549-ACE2, and Vero-e6-ACE2 cells were infected with SARS-CoV-2 in serum-free media (250µL or 500µL per well for 12- or 6-well plates, respectively) at 37°C, 5%CO2 on a gentle shaker at the indicated MOI for 60 minutes to allow for viral adsorption. After adsorption, infection media was replaced with standard culture media, and infections were continued for the indicated duration of infection.

4.4. Reverse Transcription-Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

Total RNA was extracted from SARS-CoV-2 or mock-infected cells using TRIzol™ Reagent (Thermo Fisher, #15596026). The purity and concentration of extracted RNA was measured with a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo #ND-ONEC-W). 100ng of total RNA was reverse transcribed into complementary cDNA using Protoscript II (New England Biolabs, #M0368S) in a 20µL reaction containing: 1µL of 100µM gene-specific reverse primer or 2µL of 100µM random hexamer primers (NEB #S1330S), 4µL 1x Protoscript II buffer, 1µLof 10 mM dNTP, 1µL of 0.1 M DTT, 8U RNase Inhibitor (NEB #M0314S), and 200U Protoscript II reverse transcriptase. Reverse transcription was performed at 42 °C for 60 minutes, followed by enzyme inactivation at 65°C for 25 minutes.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed using SYBR Green-based detection in a Bio-Rad™ FGX Opus 96 Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad #12011319). Reactions were prepared in 20µL volume per well containing: 2µL of cDNA, 1µL of forward and reverse primers (10µM each), 10µL of 2x SYBR Green Master Mix (Bio-Rad #1725120), 7µL nuclease-free water. PCR cycling conditions were set as follows: (95C x 30s, ((95C x 5s, 60C x 30s) x 39)). Gene expression levels were quantified using either: standard curve quantification based on SARS-CoV-2 N gene standard (IDT #10006625), or by relative quantification using the 2^-ΔΔCt method, and normalized to β-Actin expression. qPCR data were analyzed using Bio-Rad CFX Maestro v2.3. Primer sequences used in this study are listed in

Supplementary Table S1.

4.5. Western-Blots

Samples were subjected to a standard SDS-PAGE protocol and were subsequently transferred onto a PVDF membrane (Sigma, #IPVH00010). The membrane was then blocked for 1 hour at room temperature using a blocking buffer composed of TSB-T (1× TBS and 0.05% Tween-20, and 5% milk. The membrane was then incubated overnight at 4°C in the blocking buffer containing the primary antibody. After incubation, the membrane was washed three times with TBS-T, then incubated for 1 hour with a rabbit/mouse-HRP conjugated secondary antibody diluted in TBS-T and washed thrice with TBS-T again. Protein signals were detected using the SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate (Thermo Scientific, #34075) and visualized using a ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad).

4.6. Immunofluorescence

Paraformaldehyde was used to fix the cells (3% paraformaldehyde and 2% sucrose in 1× PBS) for 20 minutes, followed by two washes with 1× PBS. Permeabilization was carried out with a buffer containing 1× PBS and 0.2% Triton X-100 for 5 minutes. Next, cells were washed twice with 1× PBS and blocked for 1 hour in PBS-T (1× PBS and 0.05% Tween-20) supplemented with 2% BSA and 10% milk. Primary antibody incubation was performed at room temperature for 2 hours in 1× PBS containing 2% BSA and 10% milk. Coverslips were washed thrice with PBS-T before being incubated for 1 hour with the appropriate fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies (Alexa-488 or Cy3). Following three additional washes with PBS-T, cells were stained with DAPI (5 µg/mL, MilliporeSigma #D9542), and coverslips were mounted using slow-fade mounting media (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #S36936). Imaging was conducted using a Leica DMi8 THUNDER microscope.

4.7. Bulk RNA Sequencing

A549-ACE2 were harvested 3 days post-infection using TRIzol™ Reagent (Thermo Fisher, #15596026). Frozen TRIzol lysates were shipped to a commercial sequencing facility for library preparation (poly-A selection) and RNA sequencing.

4.8. Bulk RNA Sequencing Analysis

All bulk RNA sequencing analyses were performed using Partek Flow™ (version 10). [

55] The analysis pipeline included base trimming from both ends (min QS=30); filtering contaminants (rDNA, tRNA, mtDNA) using

Bowtie 2.2.5; adapter trimming using

Cutadapt 1.12; alignment to hg38-CoV-2WA1 hybrid genome using

STAR 2.7.8a; filtering low quality alignments (minimum quality =20); quantifying to the annotation model

(Partek E/M); noise reduction (maximum count >10); count normalization using median ratio; and differential gene expression (DGE) analysis using DeSeq2.

4.9. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Analysis and Cell Type Identification

All single-cell RNA-sequencing data analyses were performed using Partek Flow™ (version 10). The analysis pipeline included filtering counts (<10% mitochondrial counts, <20% ribosomal counts, retaining 58368/108230 cells); noise reduction (exclude genes whose counts=0 in 100% of cells); and count normalization (Counts-Per-Million (CPM) +1 Log2 transformation). For DGE analysis, Severe COVID-19 samples were then down-sampled to 1053 cells/sample to allow fair comparison with mild COVID-19 samples; DGE analysis was completed using GSA and Hurdle Model.

To identify cell types, we performed the following steps after normalization: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) using the top 3000 most variable features; graph-based-clustering; UMAP was the run using the top 10 PCs. Epithelial Airway cells were defined by expression of KRT18, KRT5, and TPPP3.

4.10. Geneformer

Geneformer [

36,

37] was executed on Google Colab using an NVIDIA A100 GPU for transcriptome tokenization, in-silico deletion, and statistical analysis. The code used to run Geneformer will be made publicly available on the first author’s Github repository (

https://github.com/bfixman) upon publication.

Table 1.

Primer Sequences.

Table 1.

Primer Sequences.

| Primer |

Sequence |

Company |

| Actin - Forward |

CTGGCACCCAGCACAATG |

IDT DNA |

| Actin - Reverse |

GCCGATCCACACGGAGTACT |

IDT DNA |

| CoV-2 N1 - Forward |

GGACCCCAAAATCAGCGAAAT |

IDT DNA |

| CoV-2 N1 - Reverse |

TTCTGGTTACTGCCAGTTGAATCTG |

IDT DNA |

4.11. Antibodies

The antibodies used in this study are listed in

Table 2.

Table 2.

Antibodies.

| Antibody |

Isotype |

Company |

Catalog Number |

| SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid |

Rabbit monoclonal |

Cell Signaling technology |

86326 |

| GAPDH |

Rabbit polyclonal |

EMD Millipore |

ABS16 |

| Vinculin |

Mouse monoclonal |

Sigma |

V9264 |

| PKR |

Mouse monoclonal |

BD Biosciences |

610764 |

| PKR-pT446 |

Rabbit monoclonal |

Abcam |

ab32036 |

| eIF2ab |

Rabbit monoclonal |

Cell Signaling technology |

5324T |

| eIF2a-pS51 |

Rabbit monoclonal |

Abcam |

32157 |

| A3B |

Rabbit monoclonal |

Abcam |

184990 |

Table 3.

siRNA Sequences.

Table 3.

siRNA Sequences.

| siRNA |

Sequence |

Company |

Catalog Number |

| Control |

|

Thermo Fisher Scientific |

4390843 |

| APOBEC3B |

CCUCAGUACCACGCAGAAATT |

Thermo Fisher Scientific |

s18411 |

| APOBEC3B |

GAGAUUCUCAGAUACCUGATT |

Thermo Fisher Scientific |

s18412 |

| PKR |

GGUGAAGGUAGAUCAAAGATT |

Thermo Fisher Scientific |

s11187 |

| PKR |

GACGGAAAGACUUACGUUATT |

Thermo Fisher Scientific |

s11185 |

4.12. Statistical Analysis and Plotting

All data visualization was performed with Partek Flow™ (version 10) or GraphPad Prism™ (v10.4.0, Macintosh). Statistical significance was assessed by ANOVA followed by pairwise comparison with Student’s t-test with correction for multiple comparisons; scRNA-seq differential expression analysis was conducted using Gene-Specific-Analysis in Partek, while bulk RNA-seq differential expression analysis was conducted using DeSeq2. For immunofluorescence image quantification, CellProfiler™ (Broad Institute) was used for automated image analysis and fluorescence intensity measurements. FIJI™ was used to overlay multiple channels for the representative images.

Figure 1.

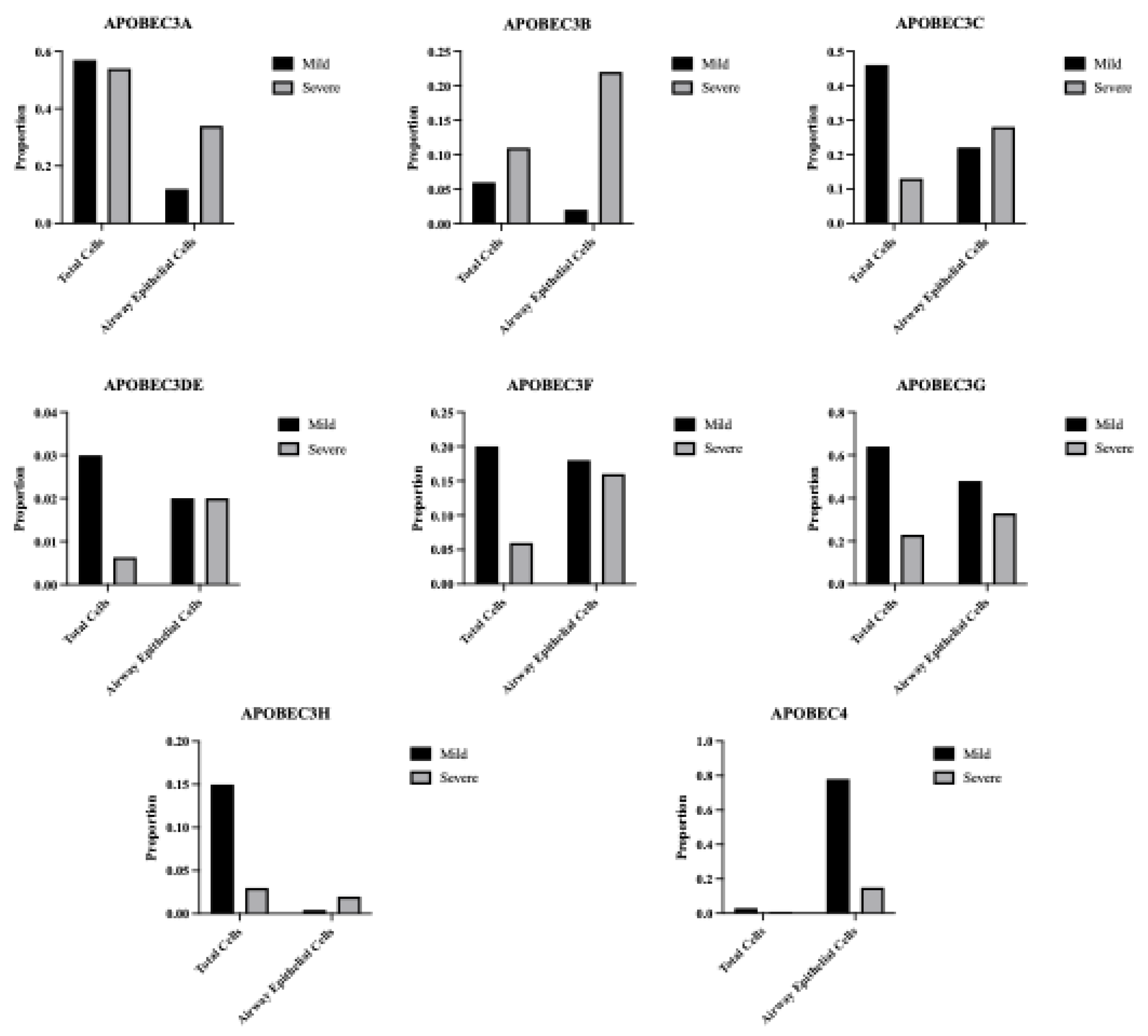

APOBEC3B is overexpressed in severe relative to mild COVID patient BALF. (A) Scatter plots showing log2 Normalized CPM+1 of APOBEC gene expression in mild (blue) and severe (red) COVID patients. Mean expression ratio (severe:mild) is shown above each plot. Cell counts were down-sampled to c=6318 (severe) to allow fair visual comparison with mild (c=6316). FDR<0.001 for all comparisons except APOBEC1 and APOBEC2. (B) UMAP plot showing distribution of cells from all samples and colored for epithelial airway marker KRT18 (green). Identified airway epithelial cells are circled in purple. (C) UMAP plot marked for A3B expression (green). Airway epithelial cells are circled. (D) Scatter plot showing log2 Normalized CPM+1 of APOBEC3B gene expression in airway epithelial cells, mild (blue) and severe (red) COVID patients.

Figure 1.

APOBEC3B is overexpressed in severe relative to mild COVID patient BALF. (A) Scatter plots showing log2 Normalized CPM+1 of APOBEC gene expression in mild (blue) and severe (red) COVID patients. Mean expression ratio (severe:mild) is shown above each plot. Cell counts were down-sampled to c=6318 (severe) to allow fair visual comparison with mild (c=6316). FDR<0.001 for all comparisons except APOBEC1 and APOBEC2. (B) UMAP plot showing distribution of cells from all samples and colored for epithelial airway marker KRT18 (green). Identified airway epithelial cells are circled in purple. (C) UMAP plot marked for A3B expression (green). Airway epithelial cells are circled. (D) Scatter plot showing log2 Normalized CPM+1 of APOBEC3B gene expression in airway epithelial cells, mild (blue) and severe (red) COVID patients.

Figure 2.

APOBEC3B knockdown reduces SARS-CoV-2 infectivity in Caco-2 through attenuation of p-PKR/p-eIF2⍺. (A) Genomic equivalents of SARS-CoV-2 at 2-, 3-, and 4-days post-infection with 8000pfu. (B) Plaque forming units/mL of media collected at 2-, 3-, and 4-days post infection (C) Western blot showing the levels of Vinculin, PKR, eIF2⍺, A3B, and SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid at 2- and 3-days post infection (MOI = 0.1) in siCNT and siA3B treated cells. (D) Western blot showing the levels of Vinculin, GAPDH, PKR, eIF2⍺, and SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid at 16, 24, and 36h post infection (MOI = 1) in siCNT and siA3B treated cells. (E) Western blot showing the levels of Vinculin and intracellular SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid at 2- and 3-days post infection in siCNT, siA3B, and siPKR treated cells. (F) Plaque forming units/mL of media collected at 3 days post infection in siCNT, siA3B, and siPKR treated cells. Bar graphs show mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was calculated by Student’s T Test: Statistical analyses are calculated from data obtained from 3 experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Figure 2.

APOBEC3B knockdown reduces SARS-CoV-2 infectivity in Caco-2 through attenuation of p-PKR/p-eIF2⍺. (A) Genomic equivalents of SARS-CoV-2 at 2-, 3-, and 4-days post-infection with 8000pfu. (B) Plaque forming units/mL of media collected at 2-, 3-, and 4-days post infection (C) Western blot showing the levels of Vinculin, PKR, eIF2⍺, A3B, and SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid at 2- and 3-days post infection (MOI = 0.1) in siCNT and siA3B treated cells. (D) Western blot showing the levels of Vinculin, GAPDH, PKR, eIF2⍺, and SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid at 16, 24, and 36h post infection (MOI = 1) in siCNT and siA3B treated cells. (E) Western blot showing the levels of Vinculin and intracellular SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid at 2- and 3-days post infection in siCNT, siA3B, and siPKR treated cells. (F) Plaque forming units/mL of media collected at 3 days post infection in siCNT, siA3B, and siPKR treated cells. Bar graphs show mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was calculated by Student’s T Test: Statistical analyses are calculated from data obtained from 3 experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Figure 3.

Severe COVID-19 patient BALF cells show signs of p-PKR/p-eIF2⍺ activation. (A) Increased eIF2⍺ phosphorylation (p-eIF2⍺) leading to translational repression leads to a decrease in expression of eIF2B, and (B) an upregulation of ATF4, GADD34, and CHOP expression. (C) Pathway overview in which SARS-CoV-2 infection induces an upregulation of APOBEC3B, driving an increase in p-PKR and p-eIF2⍺, leading to a decrease in eIF2B and increases in ATF4, GADD34, and CHOP.

Figure 3.

Severe COVID-19 patient BALF cells show signs of p-PKR/p-eIF2⍺ activation. (A) Increased eIF2⍺ phosphorylation (p-eIF2⍺) leading to translational repression leads to a decrease in expression of eIF2B, and (B) an upregulation of ATF4, GADD34, and CHOP expression. (C) Pathway overview in which SARS-CoV-2 infection induces an upregulation of APOBEC3B, driving an increase in p-PKR and p-eIF2⍺, leading to a decrease in eIF2B and increases in ATF4, GADD34, and CHOP.

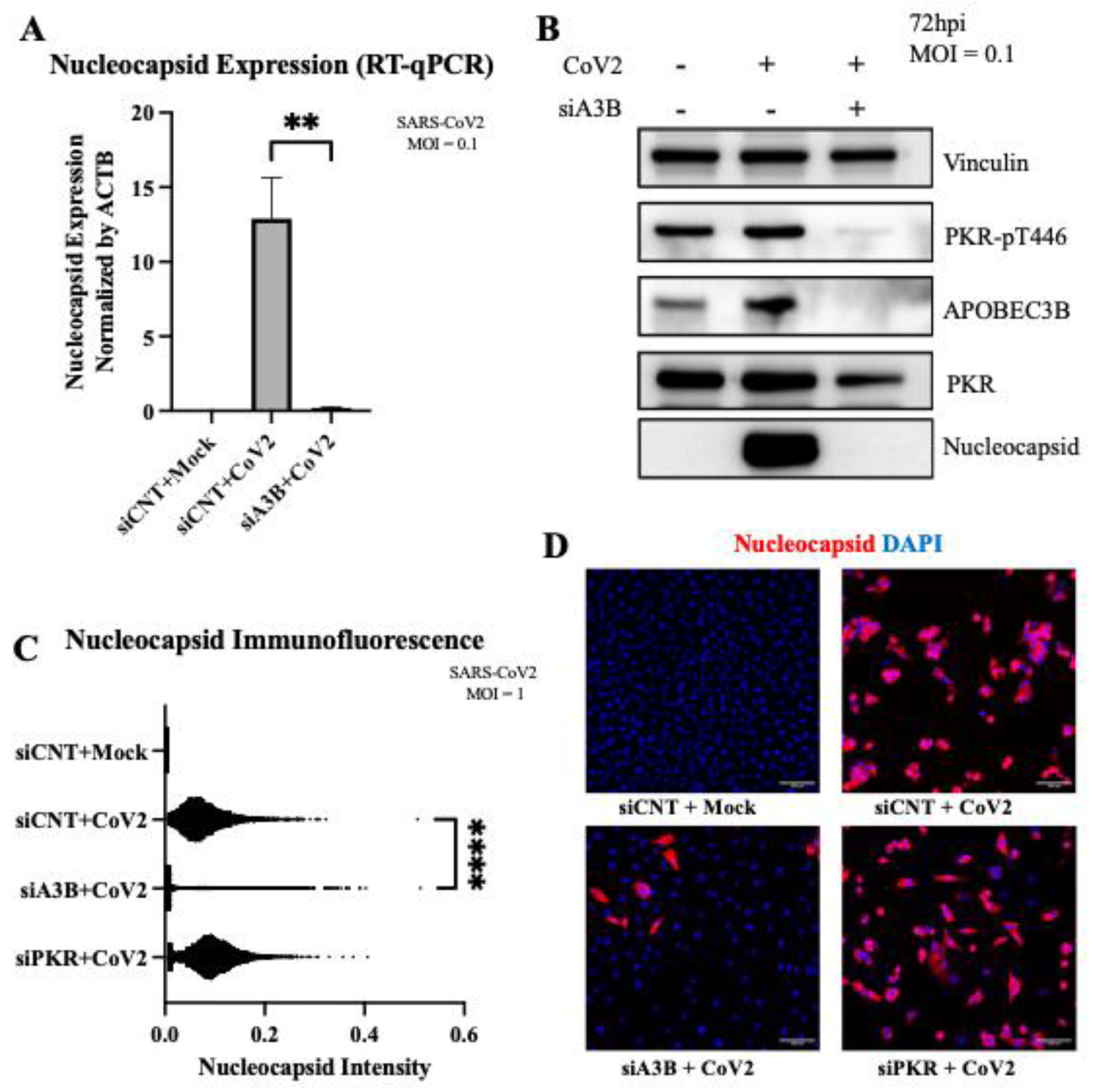

Figure 4.

APOBEC3B knockdown reduces SARS-Cov-2 Infectivity in A549-ACE2 independent of p-PKR/p-eIF2⍺. (A) A549-ACE2 cells were infected at MOI=0.1 and RNA was harvested 3-days post infection for quantification by RT-qPCR. Bar graph shows mean ± SEM. (B) Western blot showing a decrease of intracellular SARS-Cov-2 Nucleocapsid at 3-days post infection with APOBEC3B knockdown, but no clear sign of PKR activation with infection. (C) Quantification of intracellular nucleocapsid intensity per cell as stained by immunofluorescence 3-days post infection (MOI=1) showing decreased nucleocapsid with APOBEC3B knockdown only. (D) Representative images showing nuclei (blue), CoV-2 Nucleocapsid (red). Statistical significance was calculated by ANOVA followed by pairwise comparison with correction. Statistical analysis for qPCR was completed on 3 experiments. Statistical analysis on immunofluorescence was completed on 1 experiment. **P<0.01, ****P<0.0001.

Figure 4.

APOBEC3B knockdown reduces SARS-Cov-2 Infectivity in A549-ACE2 independent of p-PKR/p-eIF2⍺. (A) A549-ACE2 cells were infected at MOI=0.1 and RNA was harvested 3-days post infection for quantification by RT-qPCR. Bar graph shows mean ± SEM. (B) Western blot showing a decrease of intracellular SARS-Cov-2 Nucleocapsid at 3-days post infection with APOBEC3B knockdown, but no clear sign of PKR activation with infection. (C) Quantification of intracellular nucleocapsid intensity per cell as stained by immunofluorescence 3-days post infection (MOI=1) showing decreased nucleocapsid with APOBEC3B knockdown only. (D) Representative images showing nuclei (blue), CoV-2 Nucleocapsid (red). Statistical significance was calculated by ANOVA followed by pairwise comparison with correction. Statistical analysis for qPCR was completed on 3 experiments. Statistical analysis on immunofluorescence was completed on 1 experiment. **P<0.01, ****P<0.0001.

Figure 5.

Geneformer predicts AMPD2 is dysregulated by APOBEC3B knockout in severe COVID-19 infection. (A) In-Silico deletion of APOBEC3B in airway epithelial cells of severe COVID patients revealed gene embedding predictions on 14498 genes. AMPD2 is circled in red.

(B) Pathway through which AMPD2 dysregulation could impact SARS-CoV-2 pathology.

(C) Bulk RNA Seq shows that APOBEC3B expression is induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection and knocked down by siA3Bs (left). AMPD2 is knocked out with SARS-CoV-2 infection, and has expression restored with APOBEC3B knockdown (right).

(D) AMPD2 expression is reduced in severe relative to mild COVID-19 BALF (right); corresponding increase in APOBEC3B in severe relative to mild COVID (from

Figure 1A, left). Bar graphs show mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was calculated by Student’s T Test, corrected for multiple comparisons: Statistical analyses are calculated from data obtained from 3 experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01.2.7. AMPD2 Is Down-Regulated in Severe COVID-19 Infection.

Figure 5.

Geneformer predicts AMPD2 is dysregulated by APOBEC3B knockout in severe COVID-19 infection. (A) In-Silico deletion of APOBEC3B in airway epithelial cells of severe COVID patients revealed gene embedding predictions on 14498 genes. AMPD2 is circled in red.

(B) Pathway through which AMPD2 dysregulation could impact SARS-CoV-2 pathology.

(C) Bulk RNA Seq shows that APOBEC3B expression is induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection and knocked down by siA3Bs (left). AMPD2 is knocked out with SARS-CoV-2 infection, and has expression restored with APOBEC3B knockdown (right).

(D) AMPD2 expression is reduced in severe relative to mild COVID-19 BALF (right); corresponding increase in APOBEC3B in severe relative to mild COVID (from

Figure 1A, left). Bar graphs show mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was calculated by Student’s T Test, corrected for multiple comparisons: Statistical analyses are calculated from data obtained from 3 experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01.2.7. AMPD2 Is Down-Regulated in Severe COVID-19 Infection.