1. Introduction

Optimizing performance is the focus of every athlete through a balanced cycle of training and recovery phases. Resistance training has emerged as a crucial component in athletic development, demonstrating significant benefits across various performance metrics in elite athletes [

1]. Research has shown that resistance training programs which are properly structured can lead to substantial improvements in muscle strength, power, and sport-specific performance, with effect sizes ranging from small to very large (~ 0.15 - 6.80) [

2]. Female athletes, in particular, have shown remarkable adaptations to resistance training, with studies documenting significant improvements in strength, power output, and sport-specific skills observed in tennis serve velocity, volleyball performance, and soccer-specific capabilities [

3]. These adaptations extend beyond mere strength gains, encompassing important physiological changes including enhanced fat-free mass, optimized muscle fiber composition, and improved neural activation patterns [

4].

In men, metabolic stress (i.e., metabolic load) during strength training is directly related to muscle growth and strength gains. Elevated lactate levels (a marker of metabolic stress), in particular, are seen as a possible trigger for anabolic signaling processes [

5]. These processes are associated with an increase in testosterone (T), cortisol, and growth hormone (GH) in the blood, which in turn can promote anabolic and metabolic processes and therefore also muscle adaptation.

The scientific interest in the capacity of resistance training to elicit acute hormonal responses, particularly regarding transient changes in anabolic hormones and their metabolites has grown in recent years [4,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Especially in men, several studies have demonstrated a positive effect of strength training on androgenic hormones, most notably T, following resistance training [

6,

11,

19,

20,

21,

22]. However, these findings have not been consistently replicated, with other studies reporting minimal or no changes in hormonal concentrations in male athletes in the acute post-exercise phase [

23,

24] or after several weeks of resistance training [

4,

16,

25].

In women, the endocrine response to resistance training has been even more variable. Acute responses involving key hormones such as cortisol, T, GH, and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) have been examined across a wide range of female populations, differing in training status and age with the exercise protocol ranging from low-volume single-set circuits to high-volume multiple-set training [

9,

11,

12,

13,

14,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44].

Despite extensive research, it remains unclear whether resistance exercise reliably triggers acute endocrine responses in women, particularly with regard to anabolic androgens. The existing body of literature shows marked inconsistencies, which can be categorized into studies reporting either hormonal changes following resistance training or no hormonal changes. Several investigations have observed acute significant increases in androgens [12,14,45] following resistance training, where others show

only marginal or statistically non-significant acute elevations in androgen levels [46,47]. Other research has documented sustained elevations in androgen levels with long-term increases in androgen levels in female athletes [

7,

13,

48], reflecting potentially an endocrine adaptation over time. By contrast, other studies have found acute decreases [

9] or long-term decreases. Nevertheless, a substantial portion of the literature shows no measurable acute or chronic change in androgen levels in response to resistance training in women [

4,

6,

8,

10,

11,

15,

16,

17,

18,

26,

30,

33,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53]. Moreover, this inconsistent literature raises the question whether potential hormonal fluctuations influenced by training contribute in a functionally relevant way to cellular adaptations such as protein synthesis and muscle remodeling in the female population.

Most studies examining acute hormonal responses to resistance exercise in women have relied on immunoassays [

9,

11,

12,

13,

14,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. However, these methods often show coefficients of variation between 5% and 20%, depending on the hormone and assay conditions. Small fluctuations may therefore fall within analytical variability, which is problematic for hormones present at low concentrations such as T in women, where assay precision is frequently insufficient due to a lack of specificity [

54]. These observations underscore the methodological and physiological complexity involved in assessing hormonal responses to resistance training in women. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) offers a promising alternative to immunoassays with better specificity and sensitivity.

Velocity-based training (VBT) has emerged as an effective approach to regulate training intensity for enhancing muscle strength and athletic performance across various populations. Recent research demonstrates that VBT protocols, typically utilizing velocity loss thresholds of 15-30% and intensities of 70-80 % of one repetition maximum (1RM) [

55], can lead to significant improvements in strength and performance measures [

56]. Studies involving trained female athletes have shown remarkable results, with improvements in one-repetition maximum strength ranging from 8-23% [

57] and enhanced performance in measures such as countermovement jump and sprint performance [

58]. Notably, young females have shown substantial improvements in strength measures, with one study reporting a 27.87 % increase in squat 1RM using VBT compared to traditional training approaches [

59]. While most research has focused on trained athletes, emerging evidence suggests that VBT may be effective across different training statuses, though direct comparisons between trained and untrained populations remain limited [

60]. In VBT, the velocity of each repetition can be monitored using different devices [

61,

62]. It has been shown that the velocity is related to fatigue, repetitions in reserve, and 1RM and as such allows for monitoring training progress [

63].

Therefore, this study aimed to examine the acute endocrine response to resistance training in elite female athletes using comprehensive steroid profiling via LC-MS, and in parallel, to assess strength-related performance parameters using VBT. Furthermore, this research endeavored to address the existing gap in literature regarding the correlation between VBT approaches and hormonal changes. We hypothesized that resistance training induces acute changes in endocrine markers, particularly androgens and their related metabolites. The primary endpoint of this study was the change in dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) post-exercise. Secondary endpoints included changes in other androgens, including novel adrenal markers such as 11KT (11-ketotestosterone), 11OHA4 (11β-hydroxyandrostenedione), 11OHT (11β-hydroxytestosterone), 11KA4 (11-ketoandrostenedione), and performance metrics assessed by VBT-derived parameters, which likewise enables examination of potential menstrual cycle effects.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Nineteen healthy, female elite athletes experienced with resistance training were recruited for this study. Participants were screened based on predefined exclusion criteria, which included chronic diseases, pregnancy, breastfeeding, physical complaints (injuries or ongoing rehabilitation of injuries), endocrine disorders (e.g., type II diabetes, polycystic ovarian syndrome, endogenous androgen deficiency). All participants provided both oral and written informed consent after receiving a comprehensive explanation of the study`s objectives, methodology, potential risks, and safety precautions. The Ethics Committee of the canton Bern, Switzerland, reviewed and approved the study protocol (Project-ID: 2024-00895). The study was conducted in full compliance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki [

64].

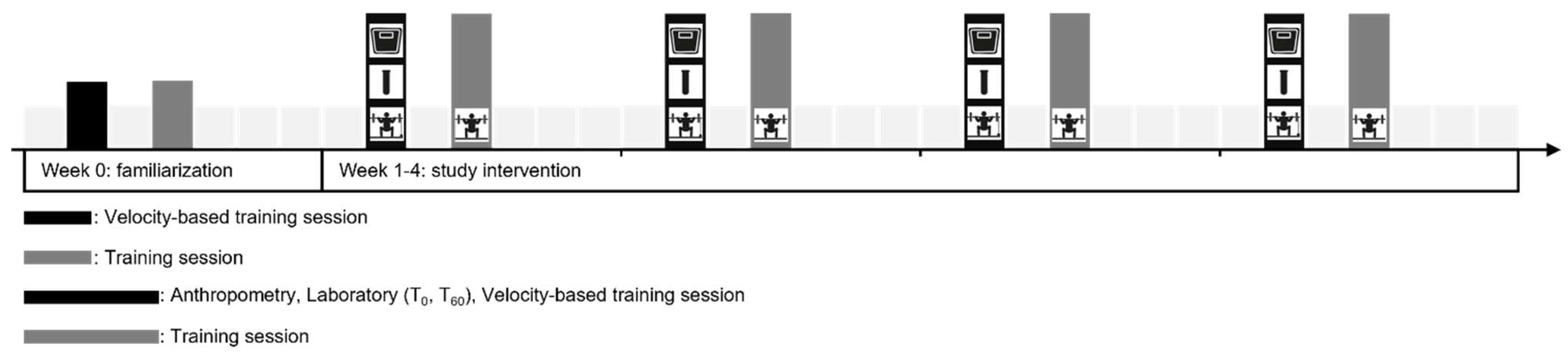

2.2. Study Design

This was a monocentric, prospective observational study investigating the acute hormonal response to resistance training in elite female athletes. The resistance training was part of the athletes’ regular training schedule and was not modified or prescribed by the study protocol. All participants engaged in resistance training twice a week over a four-week period, with laboratory assessments performed once a week, both before and after training (

Figure 1). A one-week familiarization phase preceded the intervention to ensure the standardization of testing procedures and the execution of training. The sample size was estimated based on the sample sizes reported in comparable studies [

12,

48,

65] and an assumption regarding the expected testosterone response, which is subject to uncertainty. Specifically, we assumed that an average increase of 1.25 nmol/l from a baseline of 2.5 nmol/l (Cohen’s

d ≈ 0.5) would represent a meaningful effect. Based on these considerations, a total of 34 paired pre- and post-training measurements was considered adequate to detect a statistically significant difference at an alpha level of 0.05 with 80 % power.

2.3. Measurements

2.3.1. Testing Procedures

To evaluate the acute endocrine response after strength training, blood sampling was performed during the first training session of each week over a four-week resistance training protocol; with measurements taken immediately before exercise (T0) and 60 minutes post-exercise (T60) (

Figure 1).

2.3.2. Anthropometric Measurements

Height was measured to the nearest 0.5 cm using a wall-mounted stadiometer (Seca 217, Seca, Hamburg, Germany). Body mass was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a medical scale (Seca 803, Seca, Hamburg, Germany).

2.3.3. Estimated One Repetition Maximum and Intra-Set Velocity Loss of the Back Squat Exercise

Load-velocity profiles were assessed using the average of the mean propulsive velocities (MPV) and corresponding loads during the back squat exercises [

66]. The load for the estimated 1RM for the back squat for each VBT session was determined by fitting a linear regression model and using a velocity threshold of 0.3 m/s for the first VBT session [

67,

68]. The difference in MPV between the first and the last repetition within each set was defined as the absolute velocity loss. For each athlete, the velocity losses from all sets performed within a training session were averaged to obtain a single representative value per athlete per session. Relative values were normalized to the maximal mean velocity. A linear encoder unit using a string attached to the barbell was set up for the measurements of the MPV (Vitruve, Madrid, Spain). An individualized box height was used to standardize the individual depth of the back squat (at least 90° knee angle). The height of the box was not changed during the study period. Participants were encouraged to execute the concentric phase of each repetition with maximal velocity. All calculations were conducted using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

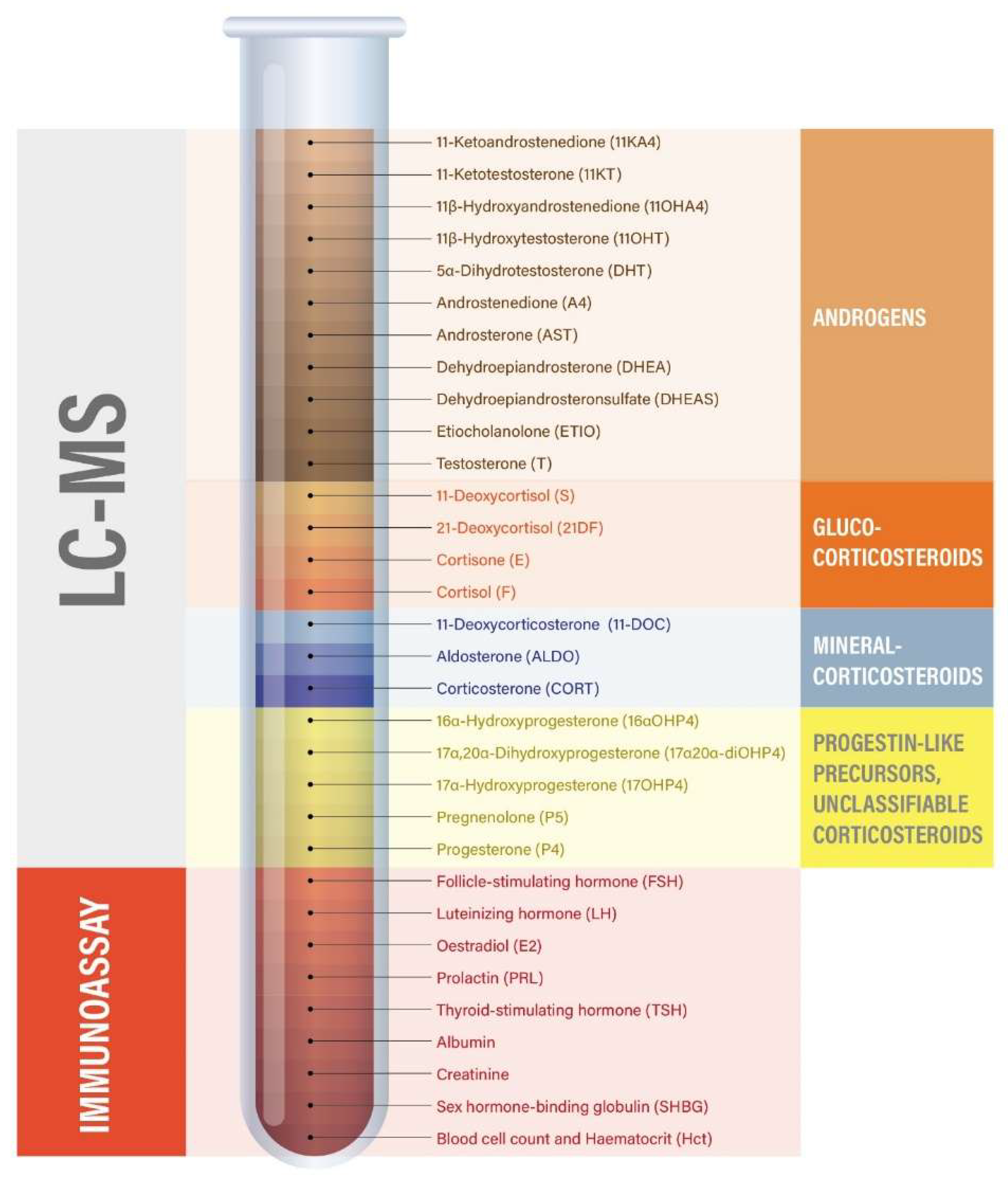

2.3.4. Blood Samples and Biochemical Analyses

Venous blood samples were collected on-site into EDTA-Plasma tubes before (T0) and 60 minutes after training (T60) by venipuncture from the antecubital vein. Samples were left at room temperature to coagulate for 10 min, after which the samples were centrifuged at 4° for 10 minutes at 1`000-2`000 xg. Thereafter, 500 µL of plasma were aliquoted into labelled 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes and stored at -20°C until analysis was initiated. Transport of samples was at room temperature. Steroid profiling (

Figure 2) was performed using a validated LC-MS method [

69]. Briefly, steroids were extracted from plasma after spiking with 38 μL of a mixture of internal standards, a protein precipitation step using zinc sulfate and methanol, and solid-phase extraction with an OasisPrime HLB 96-well plate (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA). Samples were resuspended in 100 μL 33% methanol in water, and 20 μL was injected into the LC-MS instrument (Vanquish UHPLC coupled to a QExactive Orbitrap Plus, Thermo Fisher Scientific) using an Acquity UPLC HSS T3 column (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA). Accuracy and precision have been validated to be below 15% relative standard deviation (RSD) and relative error for both inter- and intra-day validation runs tested at high, medium, low, and lower limit of accurate quantification concentration levels. In addition, analyte recovery was validated as >80% in all cases. Serum estradiol, progesterone, luteinizing hormone (LH), follicular-stimulating hormone (FSH), prolactin, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) were additionally measured by electrochemiluminescence immunoassays on a Roche Cobas 8000 automated analyzer (Roche, Rotkreuz, Switzerland). Steroid hormone binding globulin (SHBG) was measured by a solid-phase two-site chemiluminescent immunometric assay (Siemens, IMMULITE

® 2000 SHBG). Likewise, plasma albumin (bromocresol purple method) and creatinine (enzymatic method) were analyzed on a Roche Cobas 8000 automated analyzer (Roche, Rotkreuz, Switzerland). Additional parameters included complete blood count and haematocrit, which were measured on a Sysmex XR-9000 hematologic analzyer (Sysmex Suisse AG, Horgen, Switzerland). Steroid pathway involvement was estimated by grouping steroids into subcategories based on their biochemical origin (e.g., adrenal-only androgens, ovarian- and adrenal androgens, corticosteroids, mineralocorticoids), summing and weighting their concentrations to approximate the hormonal output of distinct biochemical pathways and tissue sources (see

Table 4) [

70].

2.4. Menstrual Cycle Phase Determination

The individual menstrual cycle phase was determined based on the combination of serum hormones and the calendar-based counting method [

71]. Therefore blood samples were taken before the training session, and participants were additionally asked to report the date of their last menstrual period. Classification into three phases was based on hormone concentrations of luteinizing hormone (LH), progesterone (P4), and estradiol (E2): follicular phase (LH: 2.0–14.0 U/L; P4: < 0.7 nmol/L; E2: 80–2000 pmol/L), periovulatory phase (LH: 15.0–96.0 U/L; P4: 1–7 nmol/L; E2: > 500 pmol/L), and luteal phase (LH: 1.0–11.4 U/L; P4: > 7 nmol/L; E2: 180–800 pmol/L). The classification was based on lab-specific reference ranges. In cases where classification was inconclusive, final assessment was performed by an experienced endocrinological gynecologist.

2.5. Resistance Training

The resistance training was performed in a real-world setting. The training program was planned in coordination with coaches and athletes to ensure that it fitted into the athletes’ long-term athletic development as well as short-term competition planning. The first training sessions of each week for each group of athletes are summarized in

Table 1. For football athletes, the progression of the MPV and corresponding loads over the four weeks aimed to develop maximum strength in the back squat exercise [

57,

72]. Other exercises targeting lower body muscle groups focused on power development (i.e., single leg jumps), muscular endurance (i.e., hip thrust), injury prevention (i.e., calf raises and Nordic hamstring curls), and hypertrophy (i.e., exercises targeting the upper body). For track and field athletes, regarding the progressions of repetitions, MPV, and % 1RM the emphasis of the four-week training program was on maximum strength development [

57,

72,

73]. Other exercises focused on performing over a longer set duration (i.e., hip thrust and exercises targeting the upper body) and sports specific injury prevention (i.e., eccentric leg press calf raises).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All parameters are evaluated descriptively. For continuous data, the statistical characteristics are specified: mean, standard deviation (SD), median, quartiles, and extrema. Frequency tables are calculated for ordinal and nominal data. Changes over time (pre-post) are evaluated using non-parametric Wilcoxon tests, indicated by wil. The t-test is also used for sensitivity analysis. The Mann-Whitney U test (indicated by U), also supplemented by a t-test, is used to compare two subgroups. The comparison of data from four visits was evaluated using the Friedman test. The effect sizes according to Cohen’s d (d) are calculated for changes and for group comparisons. The laboratory results after training are normalised in comparison to those before training on the basis of the change in haematocrit. Therefore, the results for each measurement are multiplied by the factor with which the pre-post hematocrit results correspond. Missing data for a visit are replaced for each subject by the mean value of available data from the other visits. Correlations are performed non-parametrically according to Spearman-Rho, indicated by SR. Linear regression equations are determined to adjust hormone concentrations, whereby the hormone with the greatest correlation to the sum of the concentrations within the profile is selected as the dependent variable. In this way, the measurement results of different hormones are equalized (weighted values). To determine the relative changes, the post value is calculated as a percentage of the pre-value (corresponding to 100%). For profile evaluation, the arithmetic and geometric mean of the relative changes in the individual hormone concentrations are determined in addition to the relative change based on their sums. To compare velocity loss between the follicular and the luteal phase in both football and track and field, Wilcoxon rank sum exact tests were conducted. Comparisons were made for both relative and absolute velocity loss between the two phases. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, but without consideration of multiple testing, and analyses were performed using SPSS version 19.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

Nineteen healthy elite female athletes (n=19) participated in the study, including eight elite football players (mean age: 18.9 ± 0.8 years) and eleven track and field athletes (mean age: 25.0 ± 3.5 years). A summary of subject demographic characteristics can be found in

Table 2. After the completion of the 4-week training program, there were no significant changes in body weight for all elite female athletes (p

wil = 0.078). Seven out of 19 athletes reported the use of hormonal contraception, including combined oral contraceptive pills (n = 2), hormonal intrauterine devices (IUDs) (n = 4), and a copper IUD (n = 1). No cases of amenorrhea were present at the time of data collection. Menarche occurred between ages 10 and 15 in 16 participants (84.2 %), while three reported onset after age 15 (15.8 %), meeting the criterion for primary amenorrhea and consistent with previous findings in elite female athletes [

74]. The two groups differed significantly in weekly training volume, with footballers training fewer hours per week than track and field athletes (p

t < 0.001).

3.2. Hormonal Responses to Resistance Training

In our study, we profiled 19 elite female athletes and compared their steroid panels pre- and post-training. In total, twenty-three steroids were quantified by the LC-MS method, and changes were compared from pre- to 60 minutes post-training. In addition to absolute differences in steroid concentrations, we also calculated the relative changes (post/pre ratio) to account for inter-individual baseline variation and to better characterize proportional hormonal shifts induced by acute resistance exercise, as summarized in

Table 3.

3.2.1. Acute Post-Exercise Alteration in the Composite Androgen Profile

While not all androgens demonstrated significant changes, several trends were observed with a significant decrease in 11OHA4 post-exercise (- 0.707 nmol/l; p = 0.01; effect size d = 0.65; - 21.1%; p = 0.01; d = 0.64), a significant increase in 11KA4 (+ 0.079 nmol/l; p = 0.02; d = 0.57; + 24.3 %), a significant decrease in AST (- 0.2 nmol/l, p < 0.05; d = 0.34, - 14.8 %), a significant decrease in DHEA (- 3.813 nmol/l; p = 0.006; d = 0.60, - 17.1 %), a non-significant increase of DHEAS (+ 350.7 nmol/l, p = 0.14, d = 0.22, + 9.9 %), a non-significant small absolute and relative decrease in ETIO (- 0.129 nmol/l; p = 0.49, d = 0.29, - 4.9 %), and a statistically non-significant reduction in total T (- 0.046 nmol/l; p = 0.080; d = 0.41, - 6.2 %). To guess the total “androgen activity / response” a sum of all androgenic hormones was built (

Table 4) out of 11OHA4, 11OHT, 11KA4, 11KT, dihydrotestosterone (DHT), androstenedione (A4), androsterone (AST), DHEA, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), T and etiocholanolone (ETIO). Summing the concentrations of these 11 androgenic hormones did not yield a statistically significant absolute change (+ 345 nmol/l; SD ± 1582.5 nmol/l, p = 0.145, d = 0.22) (

Table 3), primarily due to high variability driven by high circulatory concentration hormones such as DHEAS, which is strongly correlated with the total sum (r = 0.998; pSR < 0.001), and due to opposing directional changes among individual hormones. Using the sum of the relative change, a trend toward significance could be shown (+ 9.7%, SD ± 18.9%, p = 0.055, d = 0.51). The weighted androgen hormone profile (11OHA4, 11OHT, 11KA4, 11KT, DHT, A4, AST, DHEA, DHEAS, T, and ETIO) showed a significant increase shift post-training (p = 0.002, d = 0.86) - based on a linear regression model - indicating a hormonal reaction in female elite athletes. When excluding DHEAS due to its negligible bioactivity [

75] and calculating the total androgen profile without it, a significant decrease was observed (- 4.996 nmol/l, p = 0.01, d = 0.61), driven by the acute reduction in DHEA.

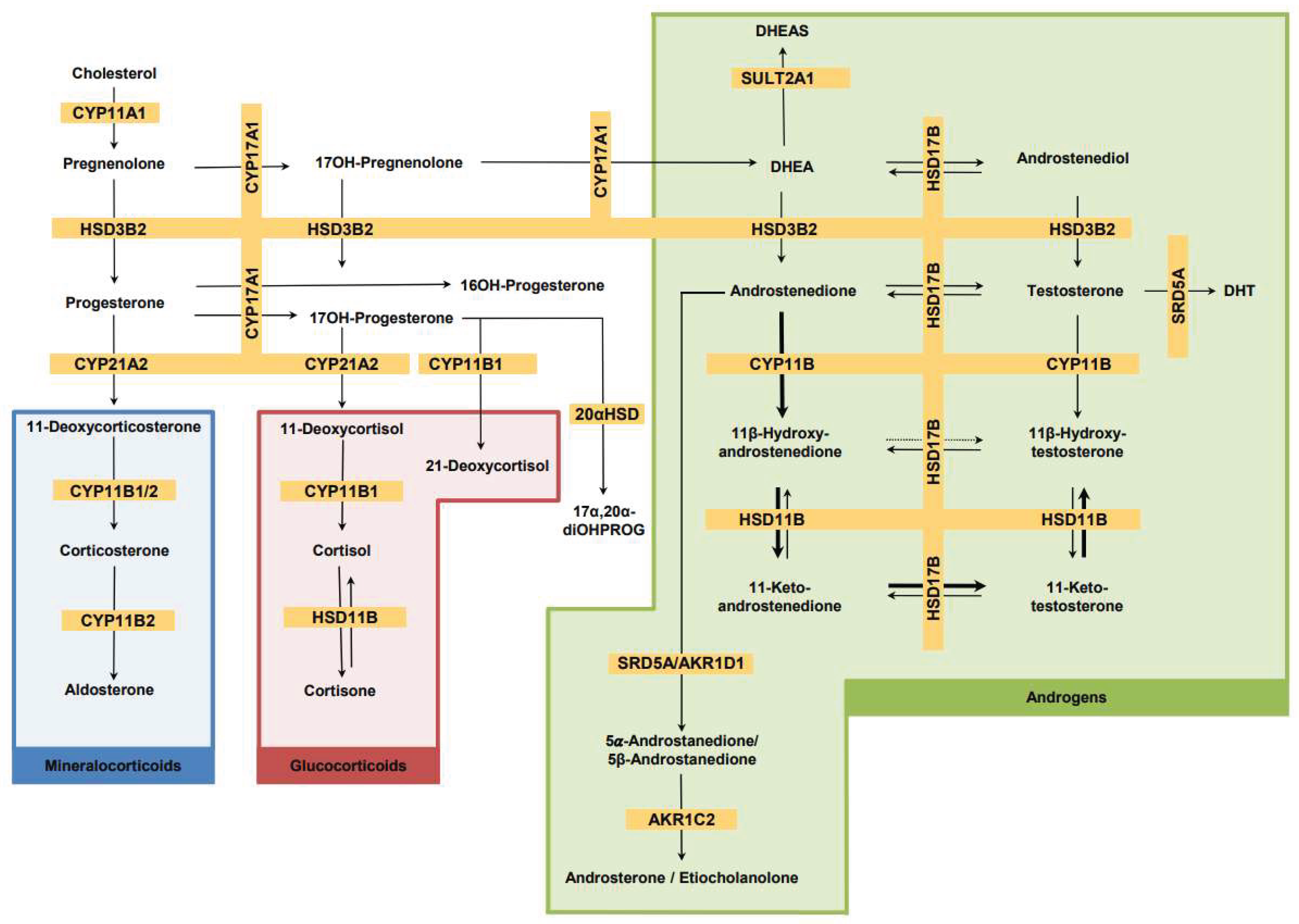

Figure 3.

Steroid biosynthetic pathways

. Description: Steroids in grey were not included in our analysis. Bold arrows show preferred conversion. Dotted arrow represents negligible conversion. See

Table 3 for steroid abbreviations. CYP11A1, Cytochrome P450 cholesterol side chain cleavage; 3βHSD2, 3β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2; CYP17A1, Cytochrome P450 17α-hydroxylase,17,20-lyase; CYP21A2, Cytochrome P450 steroid 21-hydroxylase; CYP11B1, Cytochrome P450 11β-hydroxylase; CYP11B2, Cytochrome P450 aldosterone synthase; HSD11B, 11β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase; HSD17B, 17β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase; SRD5A, Steroid- 5α-reductase; AKR1D1, aldo-keto reductase family 1 member D1; SULT2A1, sulfotransferase; AKR1C2, aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C2; 20

αHSD, 20

α-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase.

Figure 3.

Steroid biosynthetic pathways

. Description: Steroids in grey were not included in our analysis. Bold arrows show preferred conversion. Dotted arrow represents negligible conversion. See

Table 3 for steroid abbreviations. CYP11A1, Cytochrome P450 cholesterol side chain cleavage; 3βHSD2, 3β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2; CYP17A1, Cytochrome P450 17α-hydroxylase,17,20-lyase; CYP21A2, Cytochrome P450 steroid 21-hydroxylase; CYP11B1, Cytochrome P450 11β-hydroxylase; CYP11B2, Cytochrome P450 aldosterone synthase; HSD11B, 11β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase; HSD17B, 17β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase; SRD5A, Steroid- 5α-reductase; AKR1D1, aldo-keto reductase family 1 member D1; SULT2A1, sulfotransferase; AKR1C2, aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C2; 20

αHSD, 20

α-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase.

3.2.2. Acute Post-Exercise Alteration in Adrenal-Derived Androgens

Considering the entire androgen profile, it is worth examining those androgens that originate exclusively from the adrenal, mainly: 11OHA4, 11OHT, 11KA4, 11KT, and DHEAS (

Table 4). The unweighted sum of these hormone concentrations increased non-significantly post-exercise (+ 349 nmol/l; p = 0.145; d = 0.22, + 9.8 %). The dominating steroid DHEAS showed a comparable non-significant increase (+ 349.8 nmol/l, p = 0.14). Significant changes were observed for 11OHA4 (- 0.707 nmol/l; p = 0.01) and 11KA4 (+ 0.079 nmol/l; p = 0.02) (

Table 3). These divergent trends within individual androgens reflect the interconnected nature of steroid biosynthesis. When applying a weighted summation model, both statistical significance could be reached and effect size increased, confirming this tendency of an increase in androgens post-training, which exclusively originates from the adrenal (p < 0.001; d = 1.21) (

Table 3). For DHEA, which originates from both the adrenal glands and the ovaries (theca cells), a significant decrease (- 3.813 nmol/l; p = 0.006) is also worth mentioning here (

Table 3).

3.2.3. Acute Post-Exercise Alteration of Androgen Metabolites Depending on the Androgen Biosynthesis Pathway

Androgen metabolites were further categorized and examined according to their respective androgen biosynthetic pathways (

Table 4), including the classic androgen pathway, 11-oxy pathway, 11-oxy pathway including their direct precursors, and the backdoor pathway. The arithmetic sum of the classic androgen pathway, consisting of six metabolites (DHEA, A4, AST, ETIO, T and DHT) showed a significant absolute decrease in total androgen concentrations post-exercise (- 4.515 nmol/l; p = 0.005, d = 0.66) and also a significant relative decrease (- 15.4%; p = 0.005; d = 0.78). The primary androgen precursors DHEA (- 3.813 nmol/l; d = 0.006) and A4 (- 0.260 nmol/l; p = 0.080) contributed substantially to this reduction (

Table 3). A weighted summation through linear regression amplified the effect size significantly (p < 0.001, d = 1.72), confirming the acute downregulation of the classic androgen biosynthesis pathway in response to resistance training. In the 11-oxy pathway, the simple sum of six metabolites (11OHA4, 11OHT, 11KA4, 11KT, A4, and T) did not reach significance due to opposing directional changes (− 0.787 nmol/l; p = 0.096). However, the weighted profile revealed a significant post-exercise decline (p = 0.001; d = 0.97) (

Table 3), primarily driven by the marked decrease in 11OHA4 (p = 0.012). In the backdoor pathway (17OHP4, DHT, AST, P4), the unweighted profile showed no significant absolute change (+ 0.040 nmol/l; p = 0.953), again reflecting divergent hormone dynamics. Nevertheless, the weighted summation resulted in a statistically significant decline (p = 0.007; d = 0.72) (

Table 3).

3.2.4. Acute Post-Exercise Alteration in Adrenal 11-Oxygenated Adrenal Steroids

11-oxygenated steroids are presented in order of their accepted biosynthesis through the 11-oxy-pathway (1st: 11OHA4; 2nd: 11KA4, 3rd: 11KT; 4th: 11OHT. Among these, the 1st metabolite 11OHA4 decreased significantly 60 minutes post-training in the total group (- 0.707 nmol/l, SD = 1.08; p = 0.012; d = 0.65), whereas the 2nd metabolite, 11KA4 increased significantly (+ 0.079 nmol/l; SD = 0.13; p = 0.023; d = 0.57) whereas the other metabolites 11OHT and 11KT showed no significant alterations (

Table 3). The unweighted sum of these four metabolites showed no significant change (p = 0.134). Due to the individual strongly intercorrelated hormonal levels, a weighted approach revealed a significant overall decline (p = 0.002, d = 0.92), reflecting a coordinated pathway-specific and here especially adrenal-specific acute response to acute resistance exercise.

3.2.5. Acute Post-Exercise Alteration in Glucocorticoids and Mineralocorticoids

The glucocorticoid profile (11-deoxycortisol, 21-deoxycortisol, cortisol, and cortisone) and the mineralocorticoid profile (11-deoxycorticosterone, corticosterone, and aldosterone) (

Table 4) exhibited a consistent and statistically significant post-exercise decline in each hormone (

Table 3). This was reflected in a significant overall reduction in total glucocorticoid concentrations (- 107.39 nmol/l; p

< 0.001; d = 1.22) and total mineralocorticoid concentrations (- 5.058 nmol/l, p = 0.001, d = 0.87) (

Table 3). The most pronounced absolute decrease was observed in cortisol, (- 102.72 nmol/l, - 30.9 %, p < 0.001; d = 1.11) and contributed strongly to the overall decline in glucocorticoids. Within the mineralocorticoids, corticosterone emerged as the leading hormone in both absolute and relative terms (- 5.01 nmol/l, p = 0.001, d = 0.87). The weighted summation model further increased the effect sizes for both glucocorticoids (p < 0.001, d = 2.12) and mineralocorticoids (p < 0.001, d = 1.47), indicating a coordinated suppression of adrenal glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid steroid output in response to resistance training.

Table 4.

Classification of hormones in biochemical subgroups.

Table 4.

Classification of hormones in biochemical subgroups.

| Metabolite |

Androgens

(exclusively adrenal androgens marked by xx) |

Miner-

alcorti-coids

|

Gluco-

corticoids

|

Progestins,

unclassi-fiable

steroids

|

Classical

pathway

|

11-oxy pathway

|

11-oxy-

pathway

with their direct precursors

|

Backdoor

pathway

|

| 11-DOC |

|

x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| S |

|

|

x |

|

|

|

|

|

| 11KA4 |

xx |

|

|

|

|

x |

x |

|

| 11KT |

xx |

|

|

|

|

x |

x |

|

| 11OHA4 |

xx |

|

|

|

|

x |

x |

|

| 11OHT |

xx |

|

|

|

|

x |

x |

|

| 16αOHP4 |

|

|

|

x |

|

|

|

|

| 17α20α-diOHP4 |

|

|

|

x |

|

|

|

|

| 17OHP4 |

|

|

|

x |

|

|

|

x |

| 21DF |

|

|

x |

|

|

|

|

|

| DHT |

x |

|

|

|

x |

|

|

x |

| ALDO |

|

x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| A4 |

x |

|

|

|

x |

|

x |

|

| AST |

x |

|

|

|

x |

|

|

x |

| E |

|

|

x |

|

|

|

|

|

| CORT |

|

x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| F |

|

|

x |

|

|

|

|

|

| DHEA |

x |

|

|

|

x |

|

|

|

| DHEAS |

xx |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ETIO |

x |

|

|

|

x |

|

|

|

| P5 |

|

|

|

x |

|

|

|

|

| P4 |

|

|

|

x |

|

|

|

x |

| T |

x |

|

|

|

x |

|

x |

|

3.2.6. Alterations in Additional Hormonal Related Parameters

SHBG levels showed a non-significant reduction from pre- to post-training over the four-week period (p = 0.065), with no significant differences across pre- or post-training time points or between athlete groups. Prolactin levels were not statistically different between the four weeks (p = 0.823). LH, FSH and estradiol levels were determined before the training (T0) over the four weeks training period and supported the categorization of the athletes into their menstrual cycle phases. However, progesterone levels, measured via immunoassay, served as the main hormonal parameter to categorize the athletes into either the follicular phase (< 0.7 nmol/l) or the luteal phase (> 0.7 nmol/l) at T0. TSH levels (T0) were measured within the normal reference range for all athletes over the four weeks training period. A statistically significant change in albumin levels was observed from pre- to post-training (Z = - 2.360, p = 0.016), reflecting a slight overall increase in mean values (from 40.5 g/l to 41.3 g/l). Creatinine did not differ in comparison of the four pre-measurements (T0) over the four weeks training period (p = 0.839).

3.3. Velocity-Based Training Measures

No significant changes in movement velocity or estimated 1RM were observed over the 4-week intervention. Phase-related differences in relative (football: W = 18, p = 0.25; track and field: W = 17, p = 0.14) and absolute (football: W = 19, p = 0.17; track and field: W = 20, p = 0.25) velocity loss were not significant. No phase-related difference were observed for the estimated 1RM or the load-velocity profile.

4. Discussion

In the current study we show that resistance training in healthy elite female athletes leads to a significant and coordinated acute decrease in adrenal-synthesized steroid hormones, including glucocorticoids, mineralocorticoids, and classic and 11-oxygenated androgens such as DHEA (DHEA) (- 3.813 nmol/l; p = 0.006, -17.1 %) and 11OHA4 (- 0.707 nmol/l; p = 0.012, - 20 %). Hormonal responses were interpreted and characterized by classifying steroids into biochemical subgroups: androgenic steroids, exclusively adrenal-synthesized androgens, mineralocorticoids, and glucocorticoids. In addition, classification was also based on the known biosynthetic pathways (classic pathway, 11-oxy pathway, 11-oxy pathway with their direct precursors and the backdoor pathway) to enable a more comprehensive analysis of the adrenal steroidogenic response following resistance training.

4.1. Post-Exercise Change in Androgens

Overall, the acute hormone response was strongly characterized by the dominance and acute decline in DHEA concentrations. DHEA is predominantly synthesized in the zona reticularis of the adrenal cortex and, to a lesser extent, in the ovary. As an early product of the classic androgen pathway, it is derived from cholesterol via pregnenolone and subsequently converted by cytochrome P450 17A1 (CYP17A1) into DHEA [

76,

77]. DHEA is therefore a steroid hormone in the sense that it is produced rapidly in response to physiological stress, such as cortisol and corticosterone. Although DHEA primarily acts as a prohormone for more potent androgens such as testosterone and DHT, its rapid regulation makes it a sensitive marker of adrenal activity and acute physiological stress. Interestingly, there is little literature about the dynamic of DHEA after resistance training. Some previous studies also reported a decrease in DHEA one hour after resistance training, although it was not statistically significant [

78], whereas others found an acute increase in DHEA [

12,

38,

45,

65,

79,

80]. In addition to the acute decrease in DHEA as a result of resistance training in our study, there is another aspect to DHEA worth mentioning. The growing body of evidence suggests that DHEA plays a role in modulating oxidative stress. It is well documented that regular resistance training reduces the risk of developing various types of cancer (e.g., breast cancer), and thereby exerting a preventive effect on tumorigenesis. Although DHEA acutely decreases following resistance training, it is generally assumed that regular resistance training leads to a long-term increase in basal levels of IGF-1, SHBG and DHEA in both male and females over 40 years of age [

81]. DHEA in turn, has antioxidant properties. It acts as a non-competitive inhibitor of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD), thereby reducing the availability of NADPH. Since NADPH is a central substrate for the activity of NADPH oxidases (NOX), this inhibition leads to reduced production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [

82]. In this way, repetitively secreted DHEA could contribute to cancer-preventive [

83], anti-inflammatory and immunomodulating effects to reduce the risk of age-related diseases such as cancer, atherosclerosis, and neurodegenerative disorders. Of particular interest are the androgen presursors synthesized exclusively by the adrenal gland and the metabolites of the 11-oxy pathway, which correlate directly with the adrenal response.

4.2. Post-Exercise Change in Glucocorticoids

In this study, a coordinated and statistically significant decrease in both glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids was observed following resistance training.

Cortisol showed the most pronounced absolute decline (- 102.7 nmol/l, - 30.9 %, p < 0.001), contributing substantially to the overall reduction in total glucocorticoids (- 107.3 nmol/l, d = 1.22). Within the mineralocorticoids, corticosterone demonstrated the strongest decrease (- 5.01 nmol/l; p = 0.001), driving the observed reduction in total mineralocorticoids (d = 0.87). The large effect sizes in the weighted summation model (d = 2.12 for glucocorticoids; d = 1.47 for mineralocorticoids) point to a systemic suppression of adrenal steroid output in response to acute resistance exercise. These findings are in line with previous research on hormonal responses to resistance training in women. In a controlled crossover study, resistance-trained women performed hypertrophy (70 % 1RM), strength (90 % 1RM), and power-type (45 % 1RM) protocols. All modalities led to a significant post-exercise decrease in serum cortisol (p < 0.05), with the hypertrophy protocol eliciting the most pronounced endocrine response [

84], which has also been confirmed in other studies [

85]. Similar cortisol decreases 60 minutes post-exercise have been reported by Nakamura et al. [

41] in female athletes across different menstrual phases, as well as in middle-aged inactive women, where an approximate 17 % decline in cortisol was observed immediately after resistance training [

86] and likewise in resistance-trained women [

84]. Although testosterone levels in women often remain unchanged following resistance training, the concurrent acute decrease in cortisol leads to an increase in the testosterone-to-cortisol ratio, which has been described in other studies as indicative of a more anabolic environment [

84]. Other studies showed a cortisol spike 15 minutes [

46,

85], 30 minutes [

46] or 60 minutes after resistance exercise [

87]. Uchida et al. reported an acute post-exercise decrease in cortisol, but more importantly, a long-term reduction in resting cortisol levels as an adaptation to repeated training stimuli, resulting in an increased testosterone-to-cortisol ratio [

88].

4.3. Post-Exercise Change in Mineralocorticoids

The zona glomerulosa of the human adrenal cortex is the site of biosynthesis of the main mineralocorticoid aldosterone [

89]. Aldosterone plays a crucial role in maintaining fluid and electrolyte balance, as well as regulating blood pressure through sodium (Na

+) retention. Its secretion by the adrenal cortex is regulated via the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS). Physical stressors such as resistance training activate the RAAS through increased sympathetic activity and renal hypoperfusion, leading to renin release, the formation of angiotensin II, and subsequent aldosterone secretion [

90]. In addition, aldosterone secretion is triggered by neuroendocrine stress signals during resistance training through the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, where corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) from the hypothalamus triggers the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) in the pituitary, which enhances aldosterone production in the adrenal. The time course of mineralocorticoid changes, particularly aldosterone, has been well documented. Studies in male athletes show a rapid activation of the RAAS during resistance training, with elevated aldosterone concentrations occurring within 10–15 minutes and returning to baseline within 30–60 minutes post-exercise [

91]. However, data on the acute mineralocorticoid response to resistance training in female athletes are limited. Our analysis 60 minutes post-exercise revealed a significant decline in both glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid steroid concentrations. Specifically, the mineralocorticoid profile including 11-deoxycorticosterone, corticosterone, and aldosterone showed a consistent and statistically significant decrease, with corticosterone demonstrating the most pronounced absolute and relative reduction (- 5.01 nmol/l; p = 0.001;

d = 0.87) 60 minutes post-training. These results align with the reported time frame in which aldosterone typically returns to baseline after acute physical stress. While most previous studies have focused on aldosterone alone and were conducted in male athletes, our data implicate a broader decrease of the mineralocorticoid steroid pathway 60 minutes post-training. Our findings, showing a decrease in mineralocorticoid concentrations 60 minutes post-training, may reflect the recovery phase of adrenal steroid regulation in female athletes. This aligns with previous literature indicating that mineralocorticoids, particularly aldosterone, rise acutely during resistance training due to RAAS activation but return to baseline following exercise cessation [

92].

4.4. Mechanism of Hormonal Change

The specific mechanism by which the decline in adrenal steroid hormone occurs is unclear from the current data. However, we speculate that one possibility is via the upregulation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway [

93], as this pathway has been shown to inhibit adrenal steroidogenesis [

94]. Concurrently, resistance exercise training is known to increase Wnt/β-catenin activity (i.e., content), for example, in the muscle [

95]. Granted, though, research on Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and exercise has almost exclusively been studied in skeletal muscle tissue. Our participants were elite female athletes who were experienced in resistance training regimens; hence, whether such a hormonal response would be observed in neophyte engaging in such exercise is unclear. However, it is well recognized that chronic exercise training results in reduced adrenal glucocorticoid responses to an exercise session as an adaptation in the endocrine system [

96]. Finally, adrenal steroid hormones can be viewed as part of the components of the internal milieu that create a positive environment for facilitating androgenic influences of skeletal muscle plasticity, which is critical for the athlete to improve performance. That said, it could be viewed that the decline in adrenal steroid hormones post-exercise is counter-productive. However, exercise training, particularly resistance training, can upregulate the internal mTOR signaling pathway and enhance skeletal muscle anabolic activity, thereby promoting alternative means of adaptive responses within the muscle, as reported in the literature [

97].

4.5. Intra-Set Velocity Measures of the Back Squat Exercise During Menstrual Cycle

Our findings indicate no phase-specific differences in estimated 1RM and velocity loss, indicating no menstrual cycle-specific performance variation. Based on elevated progesterone and reduced estrogen levels during the luteal phase, which may impair neuromuscular efficiency and increase perceived exertion [

98,

99], a phase-specific difference would have been expected. A recent systematic review by Colenso-Semple et al. observed mixed findings across several studies with no consistent pattern whether menstrual cycle phase affects performance or not, whereby menstrual cycle verification was methodologically insufficient in the majority of cases [

100]. Hence, our results underscore the importance of further investigating how to integrate menstrual cycle tracking into the athletic programming of female athletes. Whether such integration improves performance and recovery remains unclear, as current evidence is inconsistent and requires further assessment.

4.6. Methodological Considerations

This study applied the gold-standard LC-MS method to accurately quantify low-concentration steroid hormones, which is particularly important in female subjects [

101]. To our knowledge, only a few studies have investigated the acute response to DHEA following resistance training. Moreover, this is the first study to perform comprehensive steroid profiling in female athletes, allowing a broader and more integrated interpretation of acute adrenal response one hour after resistance training. We further included two participants using combined oral contraceptives (COCs), as current evidence indicates, that COC typically result in blunted rather than amplified endocrine responses. Therefore, a general exclusion was not deemed necessary according to current data [

102]. A separate subgroup analysis excluding COC users (n = 17) confirmed the robustness of our results, demonstrating that the overall findings remained unchanged (see Supplemental

Table 1).

4.7. Limitations

Since the football players were younger, less experienced in resistance training, and trained less than the track and field athletes, a potential association between age, training load and hormonal responses could not be analyzed in this study and should be addressed in future studies also to clarify potential benefits of early resistance training in young female athletes. Additionally, time course analysis following minutes to hours to days after resistance training could, in the future, reveal the steroid dynamics in response to resistance training in women. To better understand a possible influence of menstrual cycle phase on performance outcomes, data collection of VBT metrics across a longer period, including multiple menstrual cycle phases, would be beneficial.

5. Conclusions

By applying comprehensive steroid profiling 60 minutes post-training using LC-MS in a cohort of elite female athletes, we demonstrated a coordinated decline in adrenal-derived steroids, including androgens (notably DHEA), glucocorticoids (cortisol), and mineralocorticoids (corticosterone), suggesting a post-exercise suppression or recovery phase of adrenal steroidogenesis. However, analysis of VBT data showed no differences in velocity metrics, indicating no menstrual phase-specific effects on strength or fatigue.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the scientific research presented. All authors read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors without undue reservation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the track and field athletes of Swiss Athletics and the football players of the U21 team of BSC Young Boys (YB), Bern, Switzerland, for their participation and collaboration in this study. The study was financially supported by the research fund of the National Sports Association (Swiss Olympic). The funder had no role in the conception of study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The results of the study are presented clearly, honestly, and without fabrication, falsification, or inappropriate data manipulation.

References

- Makaruk, H.; Starzak, M.; Tarkowski, P.; Sadowski, J.; Winchester, J. The Effects of Resistance Training on Sport-Specific Performance of Elite Athletes: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. J. Hum. Kinet. 2024, 91, 135–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zouita, A.; Darragi, M.; Bousselmi, M.; Sghaeir, Z.; Clark, C.C.T.; Hackney, A.C.; Granacher, U.; Zouhal, H. The Effects of Resistance Training on Muscular Fitness, Muscle Morphology, and Body Composition in Elite Female Athletes: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2023, 53, 1709–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, W.J.; Hakkinen, K.; Triplett-Mcbride, N.T.; Fry, A.C.; Koziris, L.P.; A Ratamess, N.; E Bauer, J.; Volek, J.S.; McConnell, T.; Newton, R.U.; et al. Physiological Changes with Periodized Resistance Training in Women Tennis Players. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staron, R.S.; Karapondo, D.L.; Kraemer, W.J.; Fry, A.C.; Gordon, S.E.; Falkel, J.E.; Hagerman, F.C.; Hikida, R.S. Skeletal muscle adaptations during early phase of heavy-resistance training in men and women. J. Appl. Physiol. 1994, 76, 1247–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, G.; Qin, S.; Yan, B.; Girard, O. Metabolic and hormonal responses to acute high-load resistance exercise in normobaric hypoxia using a saturation clamp. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1445229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poderoso, R.; Cirilo-Sousa, M.; Júnior, A.; Novaes, J.; Vianna, J.; Dias, M.; Leitão, L.; Reis, V.; Neto, N.; Vilaça-Alves, J. Gender Differences in Chronic Hormonal and Immunological Responses to CrossFit®. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2019, 16, 2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arazi, H.; Khanmohammadi, A.; Asadi, A.; Haff, G.G. The effect of resistance training set configuration on strength, power, and hormonal adaptation in female volleyball players. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2018, 43, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyröläinen, H.; Hackney, A.C.; Salminen, R.; Repola, J.; Häkkinen, K.; Haimi, J. Effects of Combined Strength and Endurance Training on Physical Performance and Biomarkers of Healthy Young Women. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018, 32, 1554–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libardi, C.A.; Nogueira, F.R.D.; Vechin, F.C.; Conceição, M.S.; Bonganha, V.; Chacon-Mikahil, M.P.T. Acute hormonal responses following different velocities of eccentric exercise. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 2013, 33, 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haff GG, Jackson JR, Kawamori N, Carlock JM, Hartman MJ, Kilgore JL, et al. Force-time curve characteristics and hormonal alterations during an eleven-week training period in elite women weightlifters. J Strength Cond Res. 2008;22(2):433-46.

- Linnamo, V.; Pakarinen, A.; Komi, P.V.; Kraemer, W.J.; Häkkinen, K. Acute Hormonal Responses to Submaximal and Maximal Heavy Resistance and Explosive Exercises in Men and Women. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2005, 19, 566–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, J.L.; Consitt, L.A.; Tremblay, M.S. Hormonal Responses to Endurance and Resistance Exercise in Females Aged 19-69 Years. Journals Gerontol. Ser. A 2002, 57, B158–B165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, J.O.; Ratamess, N.A.; Nindl, B.C.; Gotshalk, L.A.; Volek, J.S.; Dohi, K.; Bush, J.A.; Gómez, A.L.; Mazzetti, S.A.; Fleck, S.J.; et al. Low-volume circuit versus high-volume periodized resistance training in women. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2001, 33, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consitt, L.A.; Copeland, J.L.; Tremblay, M.S. Hormone Responses to Resistance vs. Endurance Exercise in Premenopausal Females. Can. J. Appl. Physiol. 2001, 26, 574–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häkkinen, K.; Pakarinen, A.; Kraemer, W.J.; Newton, R.U.; Alen, M. Basal concentrations and acute responses of serum hormones andstrength development during heavy resistance training in middle-aged andelderly men and women. Journals Gerontol. Ser. A 2000, 55, B95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickson, R.C.; Hidaka, K.; Foster, C.; Falduto, M.T.; Chatterton, R.T. Successive time courses of strength development and steroid hormone responses to heavy-resistance training. J. Appl. Physiol. 1994, 76, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraemer WJ, Fleck SJ, Dziados JE, Harman EA, Marchitelli LJ, Gordon SE, et al. Changes in hormonal concentrations after different heavy-resistance exercise protocols in women. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1993;75(2):594-604.

- Häkkinen, K.; Pakarinen, A.; Kallinen, M. Neuromuscular adaptations and serum hormones in women during short-term intensive strength training. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 1992, 64, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, K.; Iemitsu, M.; Matsutani, K.; Kurihara, T.; Hamaoka, T.; Fujita, S. Resistance training restores muscle sex steroid hormone steroidogenesis in older men. FASEB J. 2014, 28, 1891–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahtiainen, J.P.; Pakarinen, A.; Kraemer, W.J.; Hakkinen, K. Acute Hormonal Responses to Heavy Resistance Exercise in Strength Athletes Versus Nonathletes. Can. J. Appl. Physiol. 2004, 29, 527–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raastad, T.; Bjøro, T.; Hallén, J. Hormonal responses to high- and moderate-intensity strength exercise. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2000, 82, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buresh, R.; Berg, K.; French, J. The Effect of Resistive Exercise Rest Interval on Hormonal Response, Strength, and Hypertrophy With Training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2009, 23, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migiano, M.J.; Vingren, J.L.; Volek, J.S.; Maresh, C.M.; Fragala, M.S.; Ho, J.-Y.; A Thomas, G.; Hatfield, D.L.; Häkkinen, K.; Ahtiainen, J.; et al. Endocrine Response Patterns to Acute Unilateral and Bilateral Resistance Exercise in Men. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2010, 24, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, D.W.D.; Phillips, S.M. Associations of exercise-induced hormone profiles and gains in strength and hypertrophy in a large cohort after weight training. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2011, 112, 2693–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, G.J.; Syrotuik, D.; Martin, T.P.; Burnham, R.; Quinney, H.A. Effect of concurrent strength and endurance training on skeletal muscle properties and hormone concentrations in humans. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2000, 81, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benini, R.; Nunes, P.R.P.; Orsatti, C.L.; Barcelos, L.C.; Orsatti, F.L. Effects of acute total body resistance exercise on hormonal and cytokines changes in men and women. 2015, 55, 337–344.

- Kraemer, W.J.; A Ratamess, N. Hormonal Responses and Adaptations to Resistance Exercise and Training. Sports Med. 2005, 35, 339–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häkkinen, K.; Newton, R.U.; Walker, S.; Häkkinen, A.; Krapi, S.; Rekola, R.; Koponen, P.; Kraemer, W.J.; Haff, G.G.; Blazevich, A.J.; et al. Effects of Upper Body Eccentric versus Concentric Strength Training and Detraining on Maximal Force, Muscle Activation, Hypertrophy and Serum Hormones in Women. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2022, 21, 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häkkinen, K.; Pakarinen, A.; Kraemer, W.J.; Häkkinen, A.; Valkeinen, H.; Alen, M. Selective muscle hypertrophy, changes in EMG and force, and serum hormones during strength training in older women. J. Appl. Physiol. 2001, 91, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häkkinen, K.; Pakarinen, A.; Kyröläinen, H.; Cheng, S.; Kim, D.; Komi, P. Neuromuscular Adaptations and Serum Hormones in Females During Prolonged Power Training. Int. J. Sports Med. 1990, 11, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häkkinen, K.; Pakarinen, A. Acute Hormonal Responses to Heavy Resistance Exercise in Men and Women at Different Ages. Int. J. Sports Med. 1995, 16, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Häkkinen, K.; Kraemer, W.J.; Pakarinen, A.; Tripleltt-Mcbride, T.; Mcbride, J.M.; Häkkinen, A.; Alen, M.; Mcguigan, M.R.; Bronks, R.; Newton, R.U. Effects of Heavy Resistance/Power Training on Maximal Strength, Muscle Morphology, and Hormonal Response Patterns in 60-75-Year-Old Men and Women. Can. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002, 27, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heavens, K.R.; Szivak, T.K.; Hooper, D.R.; Dunn-Lewis, C.; Comstock, B.A.; Flanagan, S.D.; Looney, D.P.; Kupchak, B.R.; Maresh, C.M.; Volek, J.S.; et al. The Effects of High Intensity Short Rest Resistance Exercise on Muscle Damage Markers in Men and Women. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2014, 28, 1041–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keizer, H.; Beckers, E.; de Haan, J.; Janssen, G.; Kuipers, H.; van Kranenburg, G.; Geurten, P. Exercise-Induced Changes in the Percentage of Free Testosterone and Estradiol in Trained and Untrained Women*. Int. J. Sports Med. 1987, 08, S151–S153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keizer, H.; Kuipers, H.; de Haan, J.; Beckers, E.; Habets, L. Multiple Hormonal Responses to Physical Exercise in Eumenorrheic Trained and Untrained Women*. Int. J. Sports Med. 1987, 08, S139–S150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemmler, W.; Wildt, L.; Engelke, K.; Pintag, R.; Pavel, M.; Bracher, B.; Weineck, J.; Kalender, W. Acute hormonal responses of a high impact physical exercise session in early postmenopausal women. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2003, 90, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostka, T.; Patricot, M.C.; Mathian, B.; Lacour, J.-R.; Bonnefoy, M. Anabolic and catabolic hormonal responses to experimental two-set low-volume resistance exercise in sedentary and active elderly people. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2003, 15, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Panse, B.; Labsy, Z.; Baillot, A.; Vibarel-Rebot, N.; Parage, G.; Albrings, D.; Lasne, F.; Collomp, K. Changes in steroid hormones during an international powerlifting competition. Steroids 2012, 77, 1339–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luk, H.-Y.; Levitt, D.E.; Boyett, J.C.; Rojas, S.; Flader, S.M.; McFarlin, B.K.; Vingren, J.L. Resistance exercise-induced hormonal response promotes satellite cell proliferation in untrained men but not in women. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2019, 317, E421–E432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merrigan, J.J.; Tufano, J.J.; Fields, J.B.; Oliver, J.M.; Jones, M.T. Rest Redistribution Does Not Alter Hormone Responses in Resistance-Trained Women. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 1867–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, Y.; Aizawa, K.; Imai, T.; Kono, I.; Mesaki, N. Hormonal Responses to Resistance Exercise during Different Menstrual Cycle States. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 967–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramadan, W.; Xirouchaki, C.E.; El-Gilany, A.-H. The Comparative Effects of High-Intensity Interval Training and Traditional Resistance Training on Hormonal Responses in Young Women: A 10-Week Intervention Study. Sports 2025, 13, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, W.; Noor, R.; Bashir, M.S. Effects of exercise on sex steroid hormones (estrogen, progesterone, testosterone) in eumenorrheic females: A systematic to review and meta-analysis. BMC Women's Heal. 2024, 24, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umlauff, L.; Weil, P.; Zimmer, P.; Hackney, A.C.; Bloch, W.; Schumann, M. Oral Contraceptives Do Not Affect Physiological Responses to Strength Exercise. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021, 35, 894–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nindl, B.C.; Kraemer, W.J.; Gotshalk, L.A.; Marx, J.O.; Volek, J.S.; Bush, J.A.; Häkkinen, K.; Newton, R.U.; Fleck, S.J. Testosterone Responses after Resistance Exercise in Women: Influence of Regional Fat Distribution. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2001, 11, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming DC, Wall SR, Galbraith MA, Belcastro AN. Reproductive hormone responses to resistance exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1987;19(3):234-8.

- Weiss, L.W.; Cureton, K.J.; Thompson, F.N. Comparison of serum testosterone and androstenedione responses to weight lifting in men and women. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 1983, 50, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraemer, W.J.; Staron, R.S.; Hagerman, F.C.; Hikida, R.S.; Fry, A.C.; Gordon, S.E.; Nindl, B.C.; Gothshalk, L.A.; Volek, J.S.; Marx, J.O.; et al. The effects of short-term resistance training on endocrine function in men and women. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 1998, 78, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borst, S.E.; Vincent, K.R.; Lowenthal, D.T.; Braith, R.W. Effects of Resistance Training on Insulin-Like Growth Factor and its Binding Proteins in Men and Women Aged 60 to 85. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2002, 50, 884–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosco, C.; Colli, R.; Bonomi, R.; VON Duvillard, S.P.; Viru, A. Monitoring strength training: neuromuscular and hormonal profile. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2000, 32, 202–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraemer, W.J.; Gordon, S.E.; Fleck, S.J.; Marchitelli, L.J.; Mello, R.; Dziados, J.E.; Friedl, K.; Harman, E.; Maresh, C.; Fry, A.C. Endogenous Anabolic Hormonal and Growth Factor Responses to Heavy Resistance Exercise in Males and Females. Int. J. Sports Med. 1991, 12, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, R.R.; Heleniak, R.J.; Tryniecki, J.L.; Kraemer, G.R.; Okazaki, N.J.; Castracane, V.D. Follicular and luteal phase hormonal responses to low-volume resistive exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1995, 27, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, M.; Ibañez, J.; González-Badillo, J.J.; Häkkinen, K.; Ratamess, N.A.; Kraemer, W.J.; French, D.N.; Eslava, J.; Altadill, A.; Asiain, X.; et al. Differential effects of strength training leading to failure versus not to failure on hormonal responses, strength, and muscle power gains. J. Appl. Physiol. 2006, 100, 1647–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Herold, D.; Fitzgerald, R.L. Immunoassays for Testosterone in Women: Better than a Guess? Clin. Chem. 2003, 49, 1250–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Feng, S.; Peng, R.; Li, H. The Role of Velocity-Based Training (VBT) in Enhancing Athletic Performance in Trained Individuals: A Meta-Analysis of Controlled Trials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 9252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Włodarczyk, M.; Adamus, P.; Zieliński, J.; Kantanista, A. Effects of Velocity-Based Training on Strength and Power in Elite Athletes—A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 5257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, J.T.; Loturco, I.; Cheesman, N.; Thiel, J.; Alvarez, M.; Miller, N.; Carpenter, N.; Barakat, C.; Velasquez, G.; Stanjones, A.; et al. Similar Strength and Power Adaptations between Two Different Velocity-Based Training Regimens in Collegiate Female Volleyball Players. Sports 2018, 6, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalvo-Pérez, A.; Alejo, L.B.; Valenzuela, P.L.; Gil-Cabrera, J.; Talavera, E.; Lucia, A.; Barranco-Gil, D. Traditional Versus Velocity-Based Resistance Training in Competitive Female Cyclists: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, C.; Vasiljevic, I.; Manojlovic, M.; Trivic, T.; Ranisavljev, M.; Stajer, V.; Thomas, E.; Bianco, A.; Drid, P. Optimizing strength training protocols in young females: A comparative study of velocity-based and percentage-based training programs. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermes, M.J.; Fry, A.C. Intentionally Slow Concentric Velocity Resistance Exercise and Strength Adaptations: A Meta-Analysis. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2023, 37, e470–e484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzetti, S.; Lamparter, T.; Lüthy, F. Validity and reliability of simple measurement device to assess the velocity of the barbell during squats. BMC Res. Notes 2017, 10, 707–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achermann, B.; Oberhofer, K.; Ferguson, S.J.; Lorenzetti, S.R. Velocity-Based Strength Training: The Validity and Personal Monitoring of Barbell Velocity with the Apple Watch. Sports 2023, 11, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jukic, I.; Prnjak, K.; Helms, E.R.; McGuigan, M.R. Modeling the repetitions-in-reserve-velocity relationship: a valid method for resistance training monitoring and prescription, and fatigue management. Physiol. Rep. 2024, 12, e15955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Declaration of Helsinki [Available from: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects.

- Consitt, L.A.; Copeland, J.L.; Tremblay, M.S. Endogenous Anabolic Hormone Responses to Endurance Versus Resistance Exercise and Training in Women. Sports Med. 2002, 32, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banyard, H.G.; Nosaka, K.; Haff, G.G. Reliability and Validity of the Load–Velocity Relationship to Predict the 1RM Back Squat. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 1897–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, A.G. Resistance Training Intensity Prescription Methods Based on Lifting Velocity Monitoring. Int. J. Sports Med. 2023, 45, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareja-Blanco, F.; Walker, S.; Häkkinen, K. Validity of Using Velocity to Estimate Intensity in Resistance Exercises in Men and Women. Int. J. Sports Med. 2020, 41, 1047–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrieu, T.; du Toit, T.; Vogt, B.; Mueller, M.D.; Groessl, M. Parallel targeted and non-targeted quantitative analysis of steroids in human serum and peritoneal fluid by liquid chromatography high-resolution mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2022, 414, 7461–7472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liimatta, J.; du Toit, T.; Voegel, C.D.; Jääskeläinen, J.; Lakka, T.A.; Flück, C.E. Multiple androgen pathways contribute to the steroid signature of adrenarche. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2024, 592, 112293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janse De Jonge X, Thompson B, Han A. Methodological Recommendations for Menstrual Cycle Research in Sports and Exercise. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2019;51(12).

- Mann, JB. Developing Explosive Athletes: Use of Velocity Based Training in Athletes2016.

- Suchomel, T.J.; Nimphius, S.; Bellon, C.R.; Stone, M.H. The Importance of Muscular Strength: Training Considerations. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 765–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, S.; Bitterlich, N.; Geboltsberger, S.; Neuenschwander, M.; Matter, S.; Stute, P. Contraception, female cycle disorders and injuries in Swiss female elite athletes—a cross sectional study. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1232656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Af, T.; J, R.; Rj, A.; We, R. 8.20 11-Oxygenated androgens in health and disease. Yearb. Paediatr. Endocrinol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auchus, R.J. Overview of Dehydroepiandrosterone Biosynthesis. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2004, 22, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naamneh Elzenaty R, du Toit T, Flück CE. Basics of androgen synthesis and action. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;36(4):101665.

- Heaney, J.L.J.; Carroll, D.; Phillips, A.C. DHEA, DHEA-S and cortisol responses to acute exercise in older adults in relation to exercise training status and sex. AGE 2011, 35, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Panse, B.; Vibarel-Rebot, N.; Parage, G.; Albrings, D.; Amiot, V.; De Ceaurriz, J.; Collomp, K. Cortisol, DHEA, and testosterone concentrations in saliva in response to an international powerlifting competition. Stress 2010, 13, 528–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riechman, S.E.; Fabian, T.J.; Kroboth, P.D.; Ferrell, R.E. Steroid sulfatase gene variation and DHEA responsiveness to resistance exercise in MERET. Physiol. Genom. 2004, 17, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouhal, H.; Jayavel, A.; Parasuraman, K.; Hayes, L.D.; Tourny, C.; Rhibi, F.; Laher, I.; Ben Abderrahman, A.; Hackney, A.C. Effects of Exercise Training on Anabolic and Catabolic Hormones with Advanced Age: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2021, 52, 1353–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, AG. Dehydroepiandrosterone, Cancer, and Aging. Aging Dis. 2022;13(2):423-32.

- Fang, Z.; Jiang, C.; Feng, Y.; Chen, R.; Lin, X.; Zhang, Z.; Han, L.; Chen, X.; Li, H.; Guo, Y.; et al. Effects of G6PD activity inhibition on the viability, ROS generation and mechanical properties of cervical cancer cells. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Cell Res. 2016, 1863, 2245–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TaheriChadorneshin H, Motameni S, Golestani A. Effects of resistance exercise type on cortisol and androgen cross talk in resistance-trained women. Journal of Exercise & Organ Cross Talk. 2021;1(1):8-14.

- Kotikangas, J.; Walker, S.; Toivonen, S.; Peltonen, H.; Häkkinen, K. Acute Neuromuscular and Hormonal Responses to Power, Strength, and Hypertrophic Protocols and Training Background. Front. Sports Act. Living 2022, 4, 919228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dote-Montero M, De-la OA, Jurado-Fasoli L, Ruiz JR, Castillo MJ, Amaro-Gahete FJ. The effects of three types of exercise training on steroid hormones in physically inactive middle-aged adults: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2021;121(8):2193-206.

- Szivak, T.K.; Hooper, D.R.; Dunn-Lewis, C.; Comstock, B.A.; Kupchak, B.R.; Apicella, J.M.; Saenz, C.; Maresh, C.M.; Denegar, C.R.; Kraemer, W.J. Adrenal Cortical Responses to High-Intensity, Short Rest, Resistance Exercise in Men and Women. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2013, 27, 748–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchida MC, Bacurau R, Navarro F, Pontes F, Tessutti V, Moreau R, et al. Alteration of testosterone: Cortisol ratio induced by resistance training in women. Revista Brasileira de Medicina do Esporte. 2004;10.

- Turcu A, Smith JM, Auchus R, Rainey WE. Adrenal androgens and androgen precursors-definition, synthesis, regulation and physiologic actions. Compr Physiol. 2014;4(4):1369-81.

- Baffour-Awuah B, Man M, Goessler KF, Cornelissen VA, Dieberg G, Smart NA, et al. Effect of exercise training on the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system: a meta-analysis. J Hum Hypertens. 2024;38(2):89-101.

- Boone CH, Hoffman JR, Gonzalez AM, Jajtner AR, Townsend JR, Baker KM, et al. Changes in Plasma Aldosterone and Electrolytes Following High-Volume and High-Intensity Resistance Exercise Protocols in Trained Men. J Strength Cond Res. 2016;30(7):1917-23.

- Patlar, S.; Ünsal, S. RAA System and Exercise Relationship. Turk. J. Sport Exerc. 2019, 21, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xiao, Q.; Xiao, J.; Niu, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Shu, G.; Yin, G. Wnt/β-catenin signalling: function, biological mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walczak, E.M.; Kuick, R.; Finco, I.; Bohin, N.; Hrycaj, S.M.; Wellik, D.M.; Hammer, G.D. Wnt Signaling Inhibits Adrenal Steroidogenesis by Cell-Autonomous and Non–Cell-Autonomous Mechanisms. Mol. Endocrinol. 2014, 28, 1471–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spillane, M.; Schwarz, N.; Willoughby, D.S. Upper-body resistance exercise augments vastus lateralis androgen receptor–DNA binding and canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling compared to lower-body resistance exercise in resistance-trained men without an acute increase in serum testosterone. Steroids 2015, 98, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackney, A.C. Stress and the neuroendocrine system: the role of exercise as a stressor and modifier of stress. Expert Rev. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 1, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Moore, D.R.; Hodson, N.; Ward, C.; Dent, J.R.; O’lEary, M.F.; Shaw, A.M.; Hamilton, D.L.; Sarkar, S.; Gangloff, Y.-G.; et al. Resistance exercise initiates mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) translocation and protein complex co-localisation in human skeletal muscle. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meignié, A.; Duclos, M.; Carling, C.; Orhant, E.; Provost, P.; Toussaint, J.-F.; Antero, J. The Effects of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Elite Athlete Performance: A Critical and Systematic Review. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNulty, K.L.; Elliott-Sale, K.J.; Dolan, E.; Swinton, P.A.; Ansdell, P.; Goodall, S.; Thomas, K.; Hicks, K.M. The Effects of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Exercise Performance in Eumenorrheic Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2020, 50, 1813–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colenso-Semple, L.M.; D'SOuza, A.C.; Elliott-Sale, K.J.; Phillips, S.M. Current evidence shows no influence of women's menstrual cycle phase on acute strength performance or adaptations to resistance exercise training. Front. Sports Act. Living 2023, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolken, J.K.; Peterson, M.M.; Cao, W.; Challoner, K.; Jin, Z. Sensitive LC-MS/MS Assay for Total Testosterone Quantification on Unit Resolution and High-Resolution Instruments. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervasio, J.; Zheng, S.; Skrotzki, C.; Pachete, A. The effect of oral contraceptive use on cortisol reactivity to the Trier Social Stress Test: A meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2022, 136, 105626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).