1. Introduction

The popularity of martial arts in modern times is evident both as a competitive sport and as a form of exercise and physical conditioning [

1]. Martial arts allow individuals to use the entire body or a specific weapon when applying attack, control, and submission techniques against another person [

1]. In recent decades, there has been a shift in the standards of martial arts, moving from negative connotations against violence to a perception as an activity of self-improvement, physical fitness, recreation, and logical competition [

2]. Among the sports modalities of martial arts is Muay Thai (MT), which is characterized as a percussion fight with the objective of striking the opponent to score points [

3]. MT is a percussion modality of an intermittent or interval nature, which has already been shown to be beneficial for aerobic fitness both acutely and after training [

4,

5].

Heart rate (HR) is a measure of cardiac activity and varies according to several factors, including age, fitness level, and type of physical activity [

6]. The autonomic nervous system plays an important role in cardiac autonomic modulation (CAM), and its behavior can be tracked by analyzing CAM, which reflects sympathetic or parasympathetic modulations [

7]. Exercise contributes to changes that involve neural changes, including changes in the command center, the reflex action of baroreceptors, and the neural reflex derived from muscle contraction [

6]. A critical factor in promoting CAM benefits is the intensity of training, which can be achieved through martial arts [

8]. Importantly, low CAM has been associated with the development of chronic cardiovascular disease and higher prevalence of mortality [

9]. Indeed, neural adaptations to physical training, as occurs in MT athletes, can decrease cardiac sympathetic modulation and increase parasympathetic modulation at rest, and thus are important cardioprotective factors, as sympathetic hyperactivity is an integral part of the pathophysiology of several cardiac diseases [

10].

Martial arts schools not only teach MT fighting techniques, but are also training centers where practitioners receive nutritional advice under the supervision of trainers [

1]. Indeed, nutrition is an important aspect of MT as it can affect the performance, recovery, and overall health of fighters. To this end, it is essential to have a correct intake of not only fluids, but also carbohydrates, proteins, and fats [

11]. In MT, some nutritional supplements may be useful, such as whey protein, which promotes muscle recovery/growth, creatine, which increases muscle strength/endurance, and beta-alanine, which increases endurance and the ability to train with intensity [

12]. In addition to adequate nutritional status, nutrient intake is important because MT competitors are usually paired based on key characteristics, including body mass. In this sense, official weigh-ins are conducted prior to each competition to verify that the athlete's body mass is consistent with their chosen weight class [

13]. A recent study in mixed martial arts athletes showed a negative energy balance and an inability to achieve the suggested levels of macronutrient intake according to the classification, recommending that these athletes receive attention regarding nutritional strategies [

14].

Although exercise is important for improving cardiovascular performance, it is unclear whether MT can confer benefits on CAM and body composition in this population. In this sense, the assessment of CAM by indirect measures, such as heart rate variability (HRV), has gained popularity in the evaluation of martial arts athletes to provide information on cardiac regulation as well as neural adaptations to training [

10]. Therefore, the effects of training in MT athletes to increase HRV, i.e., to increase parasympathetic modulation, should be investigated. On the other hand, dietary habits are directly related to competitive performance, although there is a great lack of information on amateur or professional MT athletes regarding this aspect [

14]. Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the effects of an 8-week strength training and nutritional counseling intervention on performance, CAM, and nutritional status.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This was a longitudinal and interventional study. It included the results of baseline assessment and an intervention study.

2.2. Participants

Between March and November 2024, male amateur Muay Thai fighters from the AAZIZ Academy, Curitiba, Brazil, were evaluated. The following inclusion criteria were used: age ≥18 years and a minimum training period of 24 weeks. The following exclusion criteria were used: individuals with a history of cardiac arrhythmia or arterial hypertension, individuals with severe orthopedic disease that prevented them from practicing martial arts, use of alcohol or drugs, and inability to perform the performance tests.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Centro Universitário Augusto Motta (UNISUAM) (CA-AE-77325224.4.0000.5235; March 14, 2024). This trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT06338501, March 29, 2024). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects enrolled in the study.

2.3. Training Program and Intervention

A standard 8-week training program was performed in conjunction with a specific conditioning and strength training program based on the specifics of MT. These programs were performed three times per week, on non-consecutive days, and lasted approximately 90 minutes. Each session consisted of 15 minutes of stretching, 10 minutes of warm-up, 60 minutes of specific martial arts training, and 5 minutes of cool-down with stretching. The MT training consisted of kicks, knees, punches (jab, straight, cross, and elbow), dodges, and defenses. Finally, kicks (circular thigh and front height), knees, and defenses were performed both at rest and in motion. In this study, load control and inter-set interval adjustments were used with 3 days of the full-body method, combining specific combat exercises with functional exercises [

3,

12].

A nutritional protocol based on the individual needs of each athlete was also used. One of the central points of this protocol was the diet, which should be based on a variety of healthy foods such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins and healthy fats according to the food pyramid. In this sense, nutritional guidance was provided on the nutritional adjustments that the athletes should make, as well as metabolic tracking before and after training [

15].

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Ten Seconds Frequency Speed of Kick Test (FSKT-10s)

First, the athlete stood 90 cm away from the bag. Then the athlete started the FSKT-10s using a technique called bandal tchagui. After the sound signal, the participant performed as many kicks as possible, alternating between the right and left leg. The intensity was controlled by the coach's instruction to the athlete (maximum effort). The number of blows delivered was recorded in blows per minute [

16].

2.4.2. Multiple Frequency Speed of Kick Test (FSKT-mult)

After a 1-minute rest, the athlete began the FSKT-mult test. This test consists of 5 sets of 10 s separated by 10 s of passive recovery. In each 10-set, the number of kicks was counted and added at the end of the sequence [

16,

17]. Performance was determined by the total number of kicks, i.e., the sum of the number of kicks in each set.

2.4.3. Bioimpedance Analysis (BIA)

Prior to the performance tests, BIA was performed with a whole-body tetrapolar device (Sanny®, BIA 1010, Brazil) using an electrical frequency of 50 kHz. Prior to the test, the athlete was instructed to fast for 4 hours and avoid physical activity for 12 hours. In addition, the athlete was asked to remove any metal objects he/she was wearing. The athlete was then placed in the supine position for the placement of 4 electrodes on the right side, 2 detector electrodes placed in line between the radial and ulnar styloid processes on the dorsum of the wrist and in line between the medial and lateral malleoli on the dorsum of the foot. Another 2 source electrodes were placed overlapping the head of the third metacarpal on the dorsum of the hand and the third metatarsal on the dorsum of the foot [

18].

2.4.4. Cardiac Autonomic Modulation (CAM)

To assess CAM, participants were instructed not to consume alcohol or stimulants such as coffee, tea, and chocolate for at least 12 h prior to the assessment so that there would be no direct influence on CAM at the time of collection [

19]. CAM was assessed using a heart rate monitor (V800, Polar Electro Oy, Finland). Before and during the exercise tests, RR interval signals were obtained from the heart rate monitor. These signals were exported to Kubios HRV software (Biosignal Analysis and Medical Image Group, Department of Physics, University of Kuopio, Finland) for HRV analysis using time domain, frequency domain, and Poincaré plot nonlinear analysis measures. Time domain analysis measures were as follows: (1) mean RR intervals (RR mean); (2) maximum HR; (3) standard deviation of RR intervals (SDNN), which captures overall HRV and reflects circadian heart rhythm; (4) square root of mean squared differences of consecutive RR intervals (rMSSD), which correlates with parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) activity; (5) percentage of adjacent RR intervals with a difference in duration greater than 50 ms (pNN50), which primarily represents vagal activity; and (6) triangular interpolation of RR interval histogram (TINN), which represents global autonomic activity. Frequency domain analysis measures were as follows: (1) low frequency range, which represents an index of sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activity; (2) high frequency range, which reflects modulation of efferent PNS activity; and (3) LF/HF ratio, which is an indicator of sympathetic-vagal balance, with an increase possibly related to sympathetic predominance and a decrease indicating greater parasympathetic modulation. The power of the LF and HF components was evaluated in normalized units (nu). Finally, the following nonlinear Poincaré plot measures were evaluated: (1) the standard deviation measuring the dispersion of points in the plot perpendicular to the line of identity (SD1), which represents parasympathetic modulation; (2) the standard deviation measuring the dispersion of points along the line of identity (SD2), which represents global HRV variability; (3) the ratio SD2/SD1, which represents PNS action; and (4) the approximate entropy (ApEn), which takes into account the complex dynamics of biological systems in series of RR intervals, where ApEn values close to 0 are considered highly regular and higher values imply greater complexity. We also evaluated the PNS index, calculated in the Kubios HRV software from measures of RR interval mean, rMSSD, and Poincaré plot index SD1, and the SNS index, calculated in the Kubios HRV software from measures of mean HR, a geometric measure of HRV reflecting cardiovascular system load, and Poincaré plot index SD2. Previously published recommendations [

20] were followed.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Normality of data distribution was checked using the Shapiro-Wilk test and graphical analysis of histograms. Data were expressed using measures of central tendency and dispersion appropriate for numerical data. Inferential analysis consisted of the Student's t-test for paired samples or the Wilcoxon signed-rank test to assess the variation between the pre- and post-intervention moments in the pre-fight rest and fight conditions. The 5% level was used as the criterion for determining significance. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

Of the 34 male MT fighters eligible for the study, 13 were excluded because they did not return for the post-intervention assessment. The mean age of the participants was 29.2 ± 8.1 years. The median number of kicks on the FSKT-10 was 20 (16-24) and 30 (20-34) at pre- and post-intervention, respectively (

p = 0.0008). The median number of kicks on the FSKT-mult was 92 (80.5-111) and 108 (92-134) at pre- and post-intervention, respectively (

p = 0.032). On BIA, there was a significant decrease in fat-free mass (FFM, 68 (62-85) vs. 71 (62-84) kg,

p = 0.031) and a significant increase in basal metabolic rate (BMR, 1878 (1748-2125) vs. 2063 (1806-2414 kcal),

p = 0.020) between pre- and post-intervention measurements. Comparisons of body composition between pre- and post-intervention are shown in

Table 1.

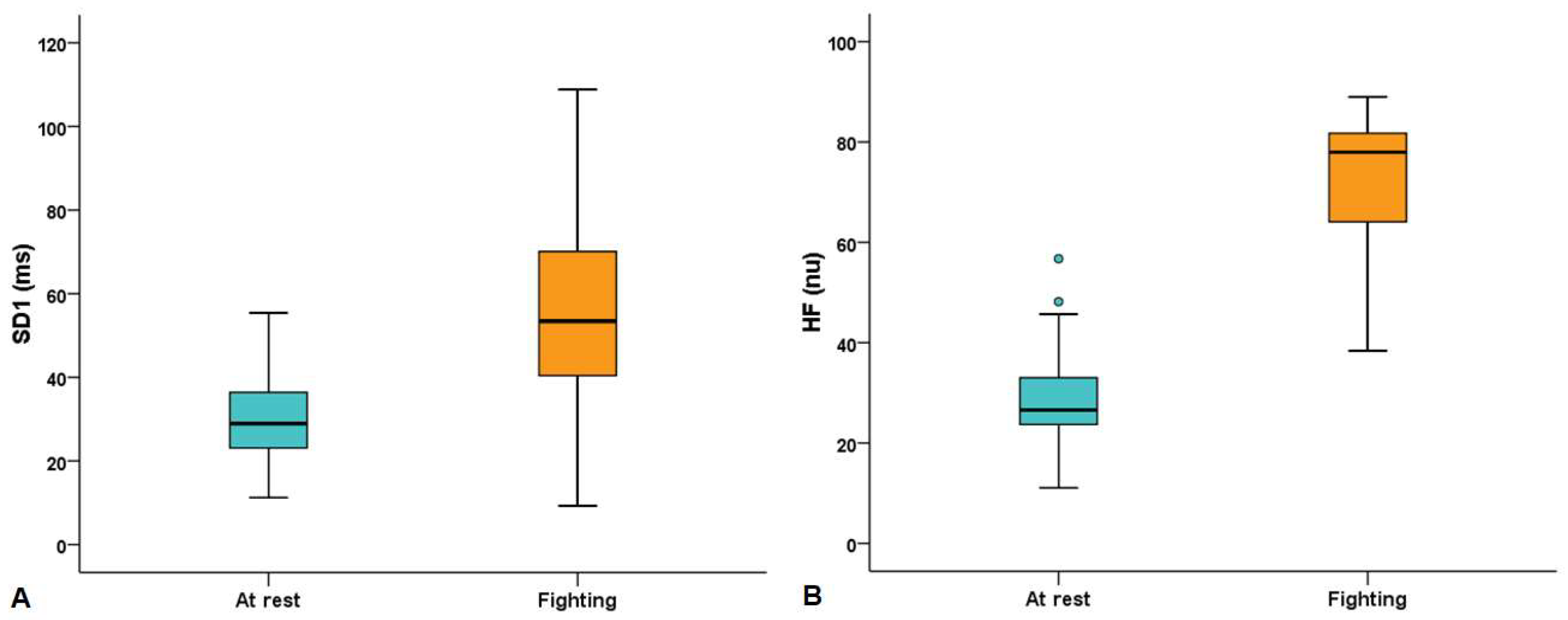

When comparing HRV indices obtained during the fight between pre- and post-intervention, an increase in HF [26.6 (23.2-34.8) vs. 78 (62.9-82) ms, p < 0.0001] and SD1 [28.9 (22.9-36.8) vs. 53.4 (40-77.8) ms, p = 0.001] was observed. There was a trend towards an increase in the LF/HF ratio [1.47 (0.73-2.69) vs. 1.07 (0.61-1.27), p = 0.073]. Comparisons of HRV indices obtained at rest before fighting between pre- and post-intervention are shown in

Table 2 and

Figure 1.

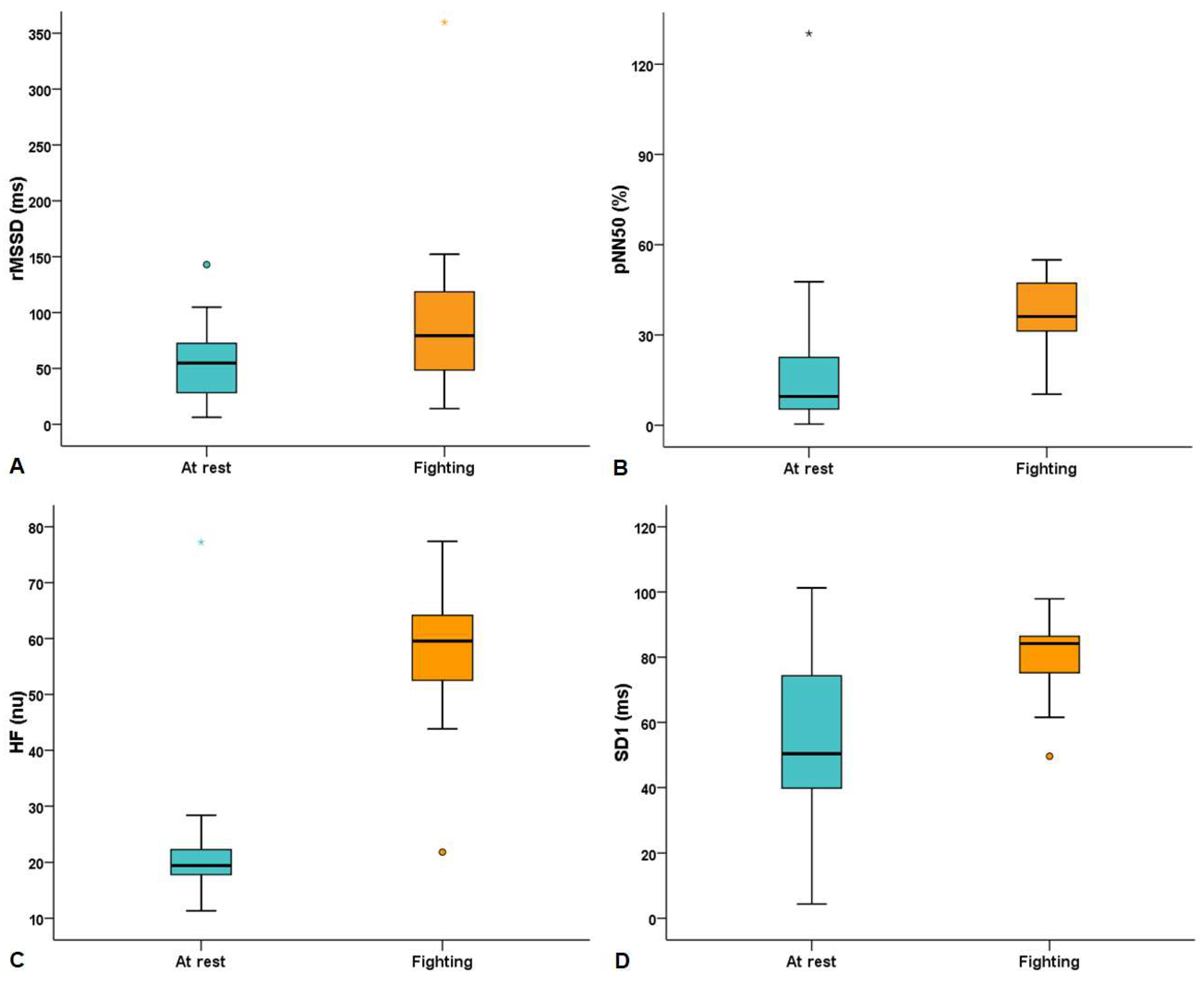

When comparing the HRV indices obtained in the fight between pre- and post-intervention, significant increases were observed in the following variables: rMSSD [55 (27-76) vs. 79 (47-131) ms, p = 0. 005]; pNN50 [9.6 (5-26.1) vs. 36.2 (24.4-48) %, p = 0.002]; HF [19.5 (16.9-22.5) vs. 59.5 (51.5-65.6) nu, p < 0.0001]; and SD1 [50.4 (39.4-79.5) vs. 84.2 (74.8-88.1) ms, p = 0.004]. Comparisons of HRV indices obtained during the fight between pre- and post-intervention are shown in

Table 3 and

Figure 2.

4. Discussion

Combat sports athletes are traditionally profiled based on anthropometrics and physiological capabilities, such as limb strength and cardiovascular fitness [

21]. Thus, understanding the changes that occur in body composition and CAM after an intervention program with strength training and nutritional guidance is essential to assess performance and adequately guide exercise prescription. The main findings of the present study were that, after an 8-week intervention in amateur MT fighters, there was an improvement in performance assessed by an increase in the number of strikes applied. In these athletes, there was an improvement in body composition assessed by FFM. Furthermore, the CAM assessed between the 2 pre-combat rest periods (pre- and post-intervention) showed a vagal withdrawal assessed by the elevation of HF and SD1. This parasympathetic activation became more evident when the 2 exercise periods were compared (pre- and post-intervention), with an increase in rMSSD, pNN50, HF and SD1. To our knowledge, this is the first study that evaluated CAM in MT fighters after an intervention based on strength training and nutritional guidance.

Kicking is a fundamental aspect of martial arts such as MT, where kick velocity and impact force are determined by several factors, including technical skill, lower body strength and flexibility, effective mass, and target factors [

22]. Using the FSKT-10s and FSKT-mult techniques, which are among the most frequently used techniques in official competition [

23], we observed a significant increase in the number of strikes applied in both FSKT-10s and FSKT-mult. Mechanisms proposed to determine kick velocity and impact force include superior utilization of proximal-to-distal movement, effective use of body mass, increased muscle activation, and improved coordination. Lower body strength and flexibility also influence kicking performance, with hip muscle strength, jumping performance, and flexibility all identified as factors influencing kicking performance [

24]. Therefore, we believe that an 8-week intervention in MT fighters should be promoted, as lower body strength likely exerts its effect by increasing the athlete's ability to generate ground reaction forces, thereby increasing final foot velocity and impact force, while flexibility improves muscle length-tension relationships, thereby increasing kicking effectiveness [

25].

In MMA athletes, Anyżewska and colleagues [

26] reported insufficient energy intake from carbohydrates, as well as decreased minerals (iodine, potassium, calcium) and vitamins (D, folate, C, E) throughout a training day. Using a nutritional protocol based on the individual needs of each athlete, we observed an increase in FFM and BMR. In line with our findings, Cha and Jee [

27] showed that Wushu Nanquan training—which is also another type of martial art—is effective not only in improving cardiac function, but also in improving body composition, which is accompanied by an increase in BMR. In this sense, it is worth highlighting the debate about rapid weight loss (RWL) and rapid weight gain (RWG). Despite the potential health and performance risks associated with RWL, many athletes believe that RWL followed by RWG provides a competitive advantage. Interestingly, a recent study showed that MT competition winners have greater RWL and RWG than losers, and rapid weight change in women appears to be associated with competitive success in this group [

13].

In the present study, we assessed HRV using both linear methods to quantify sympathovagal balance and nonlinear methods to assess the complexity of the interaction of biological systems in the heart [

28]. In the present study, we observed greater vagal activation after the intervention. Interestingly, this greater PNS activity was more pronounced when comparing the combat periods (rMSSD, pNN50, HF, SD1) with the pre-combat rest periods (HF and SD1). Interval or intermittent training has been shown to promote improvements in CAM, especially at higher intensities [

29]. In contrast to our findings, Saraiva and colleagues [

4] recently evaluated the effects of 12 weeks of functional training and MT on CAM in elderly individuals and showed no significant changes between time points in either group of individuals. These authors showed a reduction in diastolic blood pressure in MT athletes compared to functional training in older individuals. Some possible explanations for the differences in results between the 2 studies may be the type of population evaluated and the methodology used. In line with our findings, Borghi-Silva and colleagues [

30] showed that short-term rehabilitation (6 weeks) was effective enough to positively modify important CAM outcomes in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. These authors also observed that after 12 weeks, the SD1 index showed an additional improvement compared to 6 weeks (

p < 0.05). Thus, we believe that the assessment of CAM before and after intervention may be an important parameter for monitoring cardiovascular health.

The strength of this study is that it demonstrated important effects on performance, CAM, and nutritional status following an 8-week protocol of strength training and nutritional counseling in amateur MT athletes. However, several limitations should be highlighted. First, the sample is relatively small and there is no control group for either habitual physical activity or dietary intake. Second, martial arts have specificities such as physical confrontation, frequent intervals, and plyometrics, which limit the ways to monitor the intensity of this type of training [

31]. Third, the nutritional protocol, although based on the individual needs of each athlete, was not monitored; however, this is a condition that is carried out in real life. Despite these limitations, our study can serve as a starting point for randomized controlled trials with a larger number of athletes from different modalities, with the application of long-term intervention.

5. Conclusions

In amateur MT athletes, an 8-week intervention of strength training and nutritional counseling is able to improve CAM, particularly through parasympathetic activation. This greater PNS activity is better seen in HRV measurements taken during competition than during rest before competition. In these athletes, there is a better performance after the intervention as assessed by the FSKT. In addition, there is an improvement in body composition as indicated by an increase in both FFM and BMR. Based on these results, the use of an 8-week intervention is highly recommended for amateur MT athletes, and this should be kept in mind by coaches and physical trainers of this type of martial art.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B.A.J. and A.J.L.; methodology, A.B.A.J. and G.R.S..; formal analysis, A.J.L.; investigation, A.B.A.J., E.M.P.R.A., and G.R.S.; data curation, A.J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.J.L.; writing—review and editing, A.B.A.J., E.M.P.R.A., G.R.S., and A.J.L.; supervision, A.B.A.J. and E.M.P.R.A.; project administration, A.J.L.; funding acquisition, A.J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) under Grant numbers #301967/2022-9 and #401633/2023-3, Brazil, the Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ) under Grant number #E-26/200.929/2022, Brazil, and the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) under Grant number Finance Code 001, Brazil.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Centro Universitário Augusto Motta (UNISUAM) (CAAE-77325224.4.0000.5235; 14 March 2024). This trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT06338501, 29 March 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the conclusions of this article can be made available by the authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ApEn |

Approximate entropy |

| BIA |

Bioimpedance analysis |

| CAM |

Cardiac autonomic modulation |

| FSKT-10s |

Ten seconds frequency speed of kick test |

| FSKT-multi |

Multiple frequency speed of kick test |

| HF |

High frequency range |

| HR |

Heart rate |

| HRV |

Heart rate variability |

| LF |

Low frequency range |

| MT |

Muay Thai |

| pNN50 |

Percentage of adjacent RR intervals with a difference in duration greater than 50 ms |

| PNS |

Parasympathetic nervous system |

| rMSSD |

square root of mean squared differences of consecutive RR intervals |

| RR mean |

Mean RR intervals |

| SD1 |

The standard deviation measuring the dispersion of points in the plot perpendicular to the line of identity |

| SD2 |

The standard deviation measuring the dispersion of points along the line of identity |

| SDNN |

Standard deviation of RR intervals |

| SNS |

Sympathetic nervous system |

| TINN |

Triangular interpolation of RR interval histogram |

| UNISUAM |

Centro Universitário Augusto Motta |

References

- Prasetyo, Y.T.; Cahigas, M.M.L.; Patrick, E.; Rodney, M.; Nadlifatin, R.; Persada, S.F. Indonesian martial artists' preferences in martial arts schools: Sustaining business competitiveness through conjoint analysis. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0301229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monterrosa Quintero, A.; Rios, A.R.E; Fuentes-Garcia, J.P.; Sanchez, J.C.G. Levels of physical activity and psychological well-being in non-athletes and martial art athletes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, B.T.C.; Ritti-Dias, R.M.; Farah, B.Q.; Suetake, V.Y.B.; Diniz, T.A.; Costa Júnior, P.; Milanez, V.F.; Christofaro, D.G.D. Cardiovascular effects of 16 weeks of martial arts training in adolescents. Rev. Bras. Med. Esporte 2018, 24, 212–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, B.T.C.; Franchini, E.; Ribeiro, A.S.; Gobbo, L.A.; Correia, M.A.; Vanderlei, L.C.M.; Ferrari, G.; Tebar, W.R.; Christofaro, D.G.D. Effects of 12 weeks of functional training vs. Muay Thai on cardiac autonomic modulation and hemodynamic parameters in older adults: a randomized clinical trial. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2024a, 24, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, B.T.C.; Franchini, E.; Vanderlei, L.C.M.; Milanez, V.F.; Tebar, W.R.; Beretta, V.S.; Ritti-Dias, R.M.; Christofaro, D.G.D. Effects of 16-week Muay Thai practice on cardiovascular parameters in children and adolescents with overweight/obesity. Sport Sci. Health 2024, 20, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suetake, V.Y.B.; Franchini, E.; Saraiva, B.T.C.; Da Silva, A.K.F.; Bernardo, A.F.B.; Gomes, R.L.; Vanderlei, L.C.M.; Christofaro, D.G.D. Effects of 9 months of martial arts training on cardiac autonomic modulation in healthy children and adolescents. Scopus, 2018, 30, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catai, A.M.; Pastre, C.M.; de Godoy, M.F.; da Silva, E.; de Takahashi, A.C.M.; Vanderlei, L.C.M. Heart rate variability: are you using it properly? Standardisation checklist of procedures. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2020, 24, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapkiewicz, J.A.; Nunes, J.P.; Mayhew, J.L.; Ribeiro, A.S.; Nabuco, H.C.; Favero, M.T.; Franchini, E.; Do Nascimento, M.A. Effects of Muay Thai training frequency on body composition and physical fitness in healthy untrained women. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness, 2018, 58, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hämmerle, P.; Eick, C.; Blum, S.; Schlageter, V.; Bauer, A.; Rizas, K.D.; Eken, C.; Coslovsky, M.; Aeschbacher, S.; Krisai, P.; et al. Heart rate variability triangular index as a predictor of cardiovascular mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e016075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, R.M.; Rehder-Santos, P.; Simões, R.P.; Catai, A.M. Can high-intensity interval training change cardiac autonomic control? A systematic review. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2019, 23, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, L.M.A. , de Medeiros, K.C.M. Perfil nutricional de praticantes de Muay Thai. RBNE 2017, 11, 558–569. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, S.B.C.D.; Oliveira, E.B.; Júnior, A.G.B. Teoria e Prática do Treinamento para MMA, Ed. Phorte: São Paulo, Brazil, 2017.

- Doherty, C.S. , Fortington, L.V.; Barley, O.R. Rapid weight changes and competitive outcomes in Muay Thai and mixed martial arts: a 14-month study of 24 combat sports events. Sports (Basel) 2024, 12, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bueno, J.C.A.; Aoki, M.S.; Coswig, V.S.; Silveira, E.P.; Alves, R.C.; Andrade, A.; Souza Junior, T.P. Anthropometric profile and dietary intake of amateurs and professional mixed martial arts athletes. RAMA 2024, 19, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, L.C.; Cezar, T.M. Avaliação de sinais e sintomas através do rastreamento metabólico em grupo de emagrecimento realizado com colaboradores de um centro universitário do oeste do Paraná. FAG Journal of Health 2019, 20–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouergui, I.; Delleli, S.; Messaoudi, H.; Chtourou, H.; Bouassida, A.; Bouhlel, E.; Franchini, E.; Ardigò, L.P. Acute effects of different activity types and work-to-rest ratio on post-activation performance enhancement in young male and female taekwondo athletes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, C.H.; Chen, C.H.; Yang, T.J.; Chou, K.M.; Chen, B.W.; Lin, Z.Y.; Lin, Y.C. Carbohydrate mouth rinsing decreases fatigue index of taekwondo frequency speed of kick test. Chin. J. Physiol. 2022, 65, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheli, M.L.; Pagani, L.; Marella, M.; Gulisano, M.; Piccoli, A.; Angelini, F.; Burtscher, M.; Gatterer. H. Bioimpedance and impedance vector patterns as predictors of league level in male soccer players. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2014, 9, 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, E.; Vanderlei, L.; Ramos, D.; Teixeira, L.; Pitta, F.; Veloso, M. Influence of pursed-lip breathing on heart rate variability and cardiorespiratory parameters in subjects with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2009, 13, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Circulation 1996, 93, 1043–1065. [Google Scholar]

- Slimani, M.; Chaabene, H.; Miarka, B.; Franchini, E.; Chamari, K.; Cheour, F. Kickboxing review: Anthropometric, psychophysiological and activity profiles and injury epidemiology. Biol. Sport. 2017, 34, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, D.; Climstein, M.; Whitting, J.; Del Vecchio, L. Impact force and velocities for kicking strikes in combat sports: a literature review. Sports (Basel) 2024, 12, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouergui, I.; Delleli, S.; Messaoudi, H.; Bridge, C.A.; Chtourou, H.; Franchini, E.; Ardigò, L.P. Effects of conditioning activity mode, rest interval and effort to pause ratio on post-activation performance enhancement in taekwondo: a randomized study. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1179309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, K.R.; Wang, H.; Shankar, K.; Fien, A. A new method for the measurement and analysis of biomechanical energy delivered by kicking. Sports Eng. 2018, 21, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Yu, Y.; Wilde, B.; Shan, G. Biomechanical characteristics of the Axe Kick in Tae Kwon-Do. Arch. Budo. 2012, 8, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyżewska, A. , Dzierżanowski, I., Woźniak, A., Leonkiewicz, M., Wawrzyniak, A. Rapid weight loss and dietary inadequacies among martial arts practitioners from Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, J.Y.; Jee, Y.S. Wushu Nanquan training is effective in preventing obesity and improving heart function in youth. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2018, 14, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, F.; Ginsberg, J.P. An overview of heart rate variability metrics and norms. Front. Public Health 2017, 28, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granero-Gallegos, A.; González-Quílez, A.; Plews, D.; Carrasco-Poyatos, M. HRV-based training for improving VO2max in endurance athletes. A systematic review with meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 7999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghi-Silva, A. , Mendes, R.G.; Trimer, R.; Oliveira, C.R; Fregonezi, G.A.; Resqueti, V.R.; Arena, A.; Sampaio-Jorge, L.M.; Costa, D. Potential effect of 6 versus 12-weeks of physical training on cardiac autonomic function and exercise capacity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2015, 51, 211–221. [Google Scholar]

- Slimani, M.; Davis, P.; Franchini, E.; Moalla, W. Rating of perceived exertion for quantification of training and combat loads during combat sport-specific activities: a short review. J. Strength Cond. Res. 31, 2889–28902. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).