1. Introduction

The global diabetes mellitus prevalence is high and rising, in 2024 there were about 589 million diabetic patients (20-79 years) representing 1 in 9 people. Their number is expected to reach 853 million by 2050 [

1]. According to International working group of diabetic foot, diabetes related foot disease is related to a person current or previously diagnosed with diabetes mellitus that include one or more of the following: peripheral neuropathy, peripheral arterial disease (PAD), infection, ulcer(s), neuro-osteoarthropathy, gangrene or amputation [

2]. Diabetic foot has high disability and mortality rates and it is considered as one of the main health-related killers. Life time incidence of foot ulceration is 19 to 34 % with a recurrence rate of 40% in one year and 65 % at 3 years [

3]. They are also related to 75% of the major amputations of the lower limb. Worldwide, an amputation for a diabetic foot related disease is performed every 20 seconds, and 70% of these patients are going to die in the next 5 years resulting in a mortality rate higher that the most malignant tumors. Furthermore, the economic impact of diabetic foot related diseases is substantial; annually billions of dollars are needed for treatment of these patients.

Diabetic foot lesions need a multidisciplinary approach. The aim of the treatment is wound healing by infection control and prevention of the recurrence, thus avoiding major amputation. Besides glycemic control, offloading and revascularization a local intervention is often necessary: debridement, drainage of abscesses and phlegmons and even minor amputations [

4]. These methods may be considered the standard wound care but the persistent challenge in achieving timely wound healing encouraged the advance in finding new modalities of wound care.

Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) is a technique that uses under-atmospheric pressure to help promote and optimize the wound healing. The main mechanisms of NPWT are: to reduce the inflammatory exudate keeping the wound moist, to inhibit bacterial growth and to promote the granulation tissue [

5,

6]. Additional advantages include: improving wound blood perfusion; promoting cell proliferation, angiogenesis and wound tissue repair and regulating the signaling pathway to modulate cytokine expression [

7].

Ever since its introduction in 1993 by the German physician Fleischmann, its advantages have been recognized. Today, this type of therapy is used practically in all surgical specialties, both for the treatment of chronic or difficult wounds, as well as for acute closed wounds. The diabetic foot is not an exception; European and American guidelines recommend NPWT for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) [

8].

2. Materials and Methods

The aim of this paper was to appreciate the role of NPWT to avoid a major amputation in diabetic patients with foot lesions of soft tissue infection of the lower limb and comparing with the existing literature.

We retrospectively analyzed the patients with diabetic foot related disease treated by negative pressure wound therapy by a single team in the last 15 years in the 1st Department of Surgery of „Dr. I Cantacuzino” Clinical Hospital from Bucharest. Inclusion criteria were: adult diabetic patients with soft tissue infections or foot lesions for which NPWT was used in the treatment.

Negative pressure wound therapy was initiated after primary intervention in which a minor amputation, collection drainage or wound debridement were performed. The therapy was continued for 7 to 10 days (3 changes of the dressing). First dressing was changed after 2 days and the second and the third after 3 to 4 days. If necessary, an additional wound debridement was performed at every change.

The outcome was appreciated as favorable if a fully granulated wound was obtained and unfavorable if a major amputation became necessary.

The patient`s data was extracted from hospital data base and from patient`s record sheet. Informed consent was obtained from all patients in accordance with standard medical practices.

3. Results

We identified 30 patients over a period of 15 years. The indication for negative pressure therapy was represented by large and difficult wounds associated with sepsis (24 cases) or by chronic wounds associated with ischemia. The primary goal of this treatment was to avoid a major amputation. Data regarding average age, sex ratio, type of the lesions, treatment duration and outcome are summarized in

Table 1.

24 patients had a favorable outcome and 6 unfavorable. Out of the last ones 1 patient died and 5 needed a major amputation. There were 27 lesions of the foot and 3 soft tissue extensive infections of the lower limb.

Figure 1

A classification of the lesions was made using WIFI, IWGDF classification and also the therapeutic prognostic index (TPI) [

9] was calculated. No association between outcome and this classification was found in the group. In 26 out of 30 patients regarding WIFI classification the risk of amputations was high, and 12 patients out of 30 were grade 4 in IWGDF. 10 patients had a TPI higher than 6, which stands for an increased probability of a major amputation indication. There were no association find between the infection grade or TPI with the failure of NPWT to avoid a major amputation.

Clinically, the wounds ranged in size, shape and location, from small wounds after a radius amputation to large foot and calf wounds after extensive infections (

Figure 1). There were performed 14 ray amputations involving 1 to 3 toes, 4 trans metatarsal amputations, 11 debridement operations associate with fasciectomies and drainage, and one extensive wound after an above knee amputation with extensive debridement for gas gangrene (

Figure 2). These makes comparison and standardization of therapy very difficult.

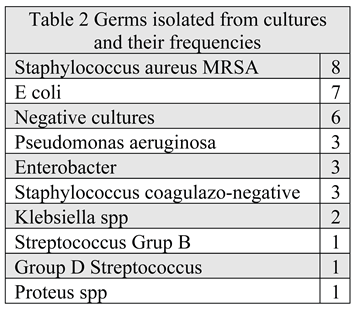

Infection was demonstrated by germ isolation from cultures in 24 cases (Table 2), in 7 of which 2 germs were identified. The most frequent germ implied was Staphylococcus aureus (SA) MRSA followed by E. coli. SA was also found in 5 out of 7 the cultures with 2 germs. In 6 cases culture were negative mostly due to previous antibiotic therapy. In 3 out of 7 cases of infection caused by Staphylococcus Aureus MRSA avoiding major amputation failed. Antibiotherapy was initially empiric and after the germ identification accordingly with antibiogram and extended on the entire period of negative pressure therapy.

From the 24 cases with favorable outcome only 6 patients were complete healed at the moment of discharge: 3 cases with skin graft and another 3 in which the wound was sutured. The other 18 were discharged with a granulated wound.

In the 5 (16,6%) cases in which major amputations were needed to obtain healing 4 were below knee and only 1 above knee amputations. 4 of them were in patients with arteriopathy and one with mixt, neuro-ischemic diabetic foot.

4. Discussion

In our series of cases NPWT was used as backup solution, in order to avoid a major amputation. Even if this goal has been accomplished in 80% of cases, it is hard to find a conclusion based only on these data, so we have conducted a literature review.

The main therapeutic principles for diabetic foot wounds are the control of infection, improvement of local tissue perfusion, offloading and promotion of tissue repair. NPWT has become an important asset in the therapeutically arsenal used in the management of diabetic foot wounds due to its effects of enhancing local perfusion, promoting granulation tissue growth and improving wound healing [

10].

Given the clinical complexities and the variety of available treatment options for diabetic foot lesions, it is essential to generate robust evidence regarding the comparative effectiveness of NPWT versus standard wound treatment. Previous studies comparing NPWT and standard wound care for DFUs have reported mixed outcomes [

11].

From the late 1990s when the product became commercially available until now, a large number of papers and basic studies have suggested the positive effects of NPWT on wound healing. Meanwhile, other series of studies and meta-analyses have found little evidence that NPWT provides better results than the standard wound care.

The first randomized clinical trial on diabetic foot postoperative wounds was published in 2005 by Armstrong et al. and included 162 patients from 18 centers with diabetes and wounds after partial amputation of the foot treated until complete healing or up to a period of 16 weeks. Results showed a better rate of complete healing and a faster granulation and healing time in the group treated with NPWT [

12].

A second study appeared 3 years later with the largest the number of patients (342) with chronic diabetic foot ulcers, published by Blume et al. It compared NPWT with advanced moist wound therapy in patients with DFUs and found that NPWT is more efficacious and equally safe in healing DFUs. A complete ulcer closure was obtained in 43,2% with NPWT versus 28.9% with moist dressings. Secondary the amputation rates were significantly lower in the group of negative pressure than advanced moist therapy (4.1% vs. 10.2%); both minor and major amputations were considered [

13].

A more recent publication is „German DiaFu RCT”, which compared NPWT with standard moist wound care (SMWC) on diabetic foot ulcer in a real-life clinical practice. This study included diabetic patients with foot lesions regardless of their neuropathic or angiopathic etiology without excluding concomitant diseases negatively impacting wound healing. Therapy application was at the discretion of the attending physician. This corresponds with the patient’s real-life situation, so the results can be generalized and applied in current clinical practice. German DiaFu RCT found that there is no significant superiority in wound closure rate or time to complete wound closure for NPWT or SMWC. Large number of patients lost at the end of the study and document missing also limited the validity of the analysis [

14].

Two large meta-analyses proved that there are a large number of published studies, but the evidence of negative pressure wound therapy efficiency is still low. First meta-analysis was published in 2018 and included eleven RCTs with 972 participants. 9 studies included patients with DFUs and the other 2 analyzed the post amputation wounds. Ten of these studies compared NPWT with dressing and one compared the effect of NPWT at two different pressure setting. According to these criteria, authors found that conclusions and results of the studies are imprecise and with risk of bias. Therefore, there is low-certainty evidence to suggest that NPWT may increase the proportion of wounds healed and reduce the time to healing for postoperative foot wounds and ulcers of the foot in people with DM [

15].

The second meta-analysis reviewed almost 400 articles and included only 9, with a total number of patients very similar – 943 patients. These studies were published in the last 10 years and had a better description of the randomization method. Wound healing rate, granulation tissue formation time, incidence of adverse reactions, and amputation rate were statistical analyzed. The results showed that NPWT can promote and accelerate the wound healing, with similar rate of adverse events and amputations rate like conventional moist therapy [

16].

Clinical data from RCTs and non-RCTs recommend the use of NPWT in the treatment of diabetic foot lesions, although data obtained from meta-analyses do not seem to specifically favor NPWT over standard treatment. At the same time, their revision in the clinical practice guidelines for the diabetic foot is also important [

17].

The largest general diabetes guidelines published annually by the American Diabetes Association do not mention specifically NPWT therapy, but acknowledges it as a treatment option for diabetic foot ulcers. NPWT is recommended when wound infection is controlled, bleeding risk is managed, and ischemia is addressed [

18,

19].

European Wound management association published in 2017 an extensive summary on the use of NPWT in different clinical situations, including diabetes foot wounds. They suggested that complication as ischemia and infection must be treated before applying NPWT. The technical progress in NPWT devices development over recent years was pointed and concluded that NPWT is an important adjuvant therapy in the management of DFUs, and that one may expect its increasing use in this field [

20].

International Working Group on the Diabetic foot released the last guidelines in 2023. They recommend the use of NPWT as an adjunct therapy to standard of care for the healing of postsurgical diabetes-related foot wounds, but to do not use it in non-surgically related diabetes foot ulcers. Also, it is not recommended for treating the diabetic foot related infection [

21,

22,

23].

5. Conclusions

Even is still very hard to obtain an undeniable statistical proof of the efficiency of NPWT in diabetic foot lesions and its capacity to avoid a major amputation, NPWT remains a very useful tool for these patients’ treatment. A correct use of NPWT combined with ethological treatment may offer a maximum chance to avoid a major amputation and obtain the healing of the wound for the patients with diabetic related foot diseases. Due to better collection of data and improvement of randomization methods, it is likely that the new RCTs will prove beyond doubt the potential benefit of NPWT in healing and wound area reduction, outcomes that are essential in the prevention of amputation in patients with diabetic foot lesions.

Author Contributions

All authors made significant contributions to the conception and critical revision of the manuscript. Each author reviewed and approved the final version and assumes responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of the scientific content. Conceptualization, O.M. and H.D.; methodology, F.B. and P.M.; software, D.-C.L and A.B.B.; validation, L.S., T.P. and O.M.; formal analysis, E.C.; investigation, O.M.; resources, A.B.B.; data curation, P.M.; writing—original draft preparation, O.M.; writing—review and editing, L.S.; visualization, D.-C.L.; supervision, T.P.; project administration, F.B.; funding acquisition, O.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of “DR. I. CANTACUZINO” CLINICAL HOSPITAL BUCHAREST (protocol code 14918 and 15.07.2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

Publication of this paper was supported by the University of Medicine and Pharmacy Carol Davila, through the institutional program Publish not Perish

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NPWT |

Negative Pressure Wound Therapy |

| DFU / DFUs |

Diabetic Foot Ulcer(s) |

| DM |

Diabetes Metillius |

| PAD |

Peripheral Arterial Disease |

| WIFI |

Wound, Ischemia, and foot Infection classification |

| IWGDF |

International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot |

| TPI |

Therapeutic Prognostic Index |

| RCT(s) |

Randomized Controlled Trial(s) |

| SMWC |

Standard Moist Wound Care |

| SA/ MRSA |

Staphylococcus aureus/ Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

References

- Federation., International Diabetes. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 11th edn. Brussels,. Belgium: 2025. Available at: https://diabetesatlas.org. (Accessed on 09/07/2025).

- Bus, S.A.; Apelqvist, J.; Chen, P.; Chuter, V.; Fitridge, R.; Game, F.; Hinchliffe, R.J.; et al. Definitions and criteria for diabetes-related foot disease (IWGDF 2023 update). Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2024, 40, e3654. Epub 2023 May 15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, D. G.; Boulton, A. J.; Bus, S. A. Diabetic foot ulcers and their recurrence. N. Engl. J. Med 2017, 376, 2367–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellomo, T.R.; Lee, S.; McCarthy, M.; Tong, K.P.S.; Ferreira, S.S.; et al. Management of the diabetic foot. Semin Vasc Surg. 2022, 35, 219-227. Epub 2022 Apr 12. [CrossRef]

- StatPearls – Negative Pressure Wound Therapy. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK576388/ (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Weed, T.; Ratliff, C.; Drake, D.B. Quantifying bacterial bioburden during negative pressure wound therapy: does the wound VAC enhance bacterial clearance? Ann Plast Surg. 2004, 52, 276–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Rong, G.C.; Wu, Q.N. Diabetic foot ulcer: Challenges and future. World J Diabetes. 2022, 13, 1014–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shizhao, J.; Xiaobin, L.; Jie, H.; et al. Consensus on the application of negative pressure wound therapy of diabetic foot wounds. Burns & Trauma. 2021, 9. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bobirca, F.; Mihalache, O.; Georgescu, D.; Patraescu, T. The new prognostic-therapeutic index for diabetic foot surgery-extended analysis. Chirurgia. 2016, 111, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.; Lv, G.; Cheng, X.; Ma, X.; Wang, W.; Gui, J.; et al. Guidelines on multidisciplinary approaches for the preventionand management of diabetic foot disease. Burns Trauma. 2020, 8, tkaa017. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q. Comparison and evaluation of negative pressure wound therapy versus standard wound care in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. BMC Surg. 2025, 25, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, D.G.; Lavery, L.A. Negative pressure wound therapy after partial diabetic foot amputation: a multicentre, randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2005, 366, 1704–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blume, P.A.; Walters, J.; Payne, W.; Ayala, J.; Lantis, J. Comparison of negative pressure wound therapy using vacuum- assisted closure with advanced moist wound therapy in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care. 2008, 31, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidel, D.; Storck, M.; Lawall, H.; et al. Negative pressure wound therapy compared with standard moist wound care on diabetic foot ulcers in real-life clinical practice: results of the German DiaFu-RCT. BMJ Open 2020, 10: e026345. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Dumville, J.C.; Hinchliffe, R.J.; Cullum, N.; Game, F.; Stubbs, N.; Sweeting, M.; Peinemann, F. Negative pressure wound therapy for treating foot wounds in people with diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, S.; Da, J.; Wu, W.; Ma, F.; Tang, C.; Li, G.; Zhong, D.; Liao, B. A systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy and safety of negative pressure wound therapy in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcer. Ann Palliat Med. 2021, 10, 10830–10839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borys, S.; Hohendorff, J.; Frankfurter, C.; Kiec, W.B.; Malecki, M.T. Negative pressure wound therapy use in diabetic foot syndrome-from mechanisms of action to clinical practice. Eur J Clin Invest. 2019, 49, (4): e13067. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrew, J.M.B.; David, G.A.; Magnus, Löndahl.; Robert, G.F.; et al. New Evidence-Based Therapies for Complex Diabetic Foot Wounds. ADA Clinical Compendia 1 February 2022. 2022, 2, 1–23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Committee, American Diabetes Association Professional Practice, 12. Retinopathy, Neuropathy, and Foot Care: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care 1 January 2024 and https://doi.org/10.2337/dc24-S012, 47 (Supplement_1): S231–S243. [CrossRef]

- Apelqvist, J.; Willy, C.; Fagerdah, A.M.; et al. Negative Pressure Wound Therapy – overview, challenges and perspectives. J Wound Care. 2017, 26, 3, S1–S113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senneville É, Albalawi Z, van Asten SA, Abbas ZG, Allison G, Aragón-Sánchez J, Embil JM, Lavery LA, Alhasan M, Oz O, Uçkay, I.; Urbančič, R.V.; Xu, Z.R.; Peters, E.J.G. WGDF/IDSA guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of diabetes-related foot infections (IWGDF/IDSA 2023). Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2024, 40, (3):e3687. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaper, N.C.; van Netten, J.J.; Apelqvist, J.; Bus, S.A.; Fitridge, R.; Game, F. et al. IWGDF Editorial Board. Practical guidelines on the prevention and management of diabetes-related foot disease (IWGDF 2023 update). Metab Res Rev. 2024, 40, e3657. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Vilorio, N.C.; Dhatariya, K.; Jeffcoate, W.; Lobmann, R.; et al. Guidelines on interventions to enhance healing of foot ulcers in people with diabetes (IWGDF 2023 update). Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2024, 40, e3644. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee, 12. Retinopathy, Neuropathy, and Foot Care: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care. 2024, 47, S231–S243. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).