Submitted:

04 September 2025

Posted:

05 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation and Labeling of Formulations

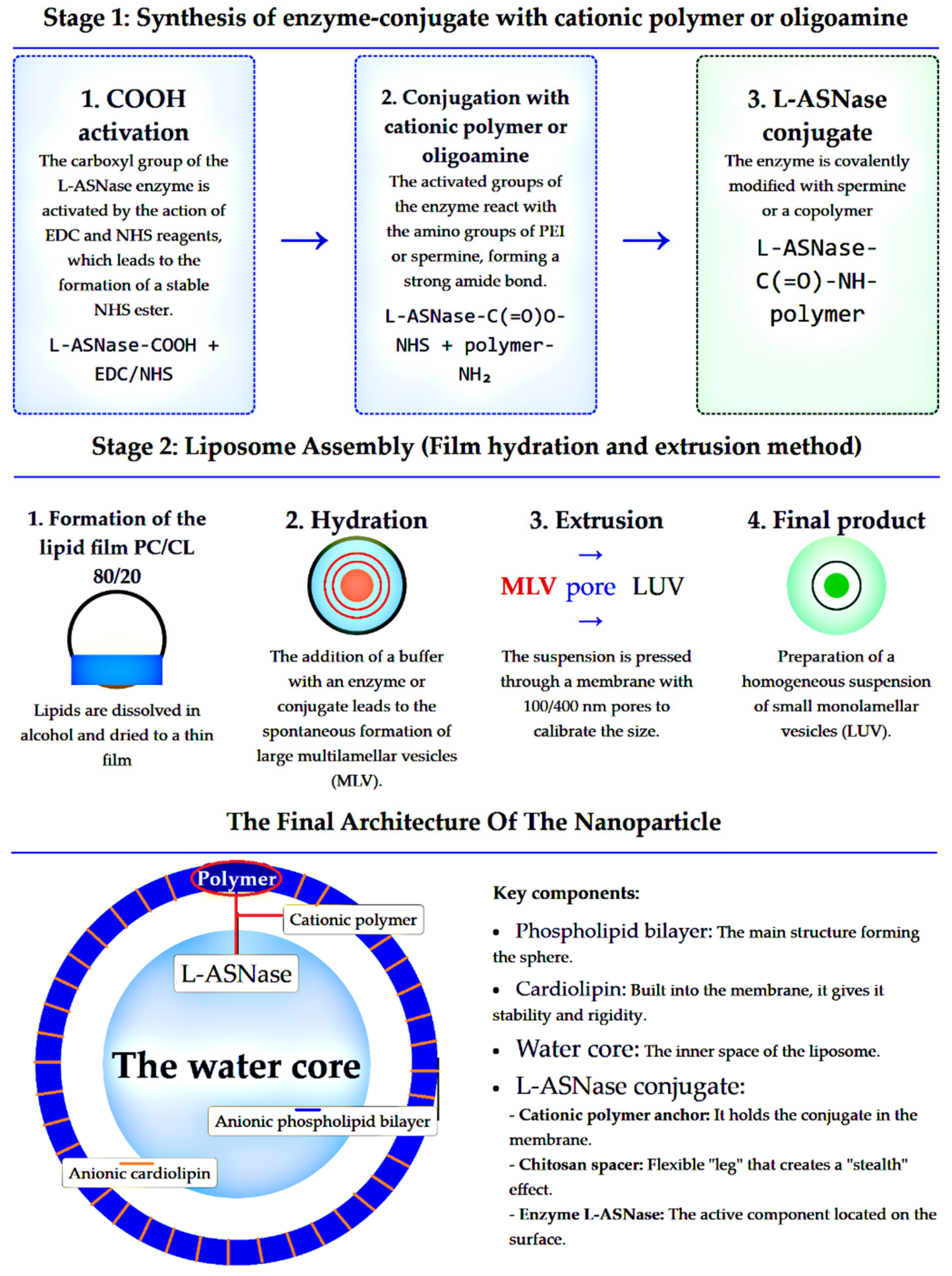

2.2.1. L-ASNase Covalent Conjugation

2.2.2. Fluorescent Labeling of L-ASNase

2.2.3. Liposome Preparation

2.3. FTIR Spectroscopy

2.4. In Vitro Release Study

2.5. Cell Culture and Viability Assay

2.6. Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM)

2.7. CLSM Image Quantification

3. Results and Discussion

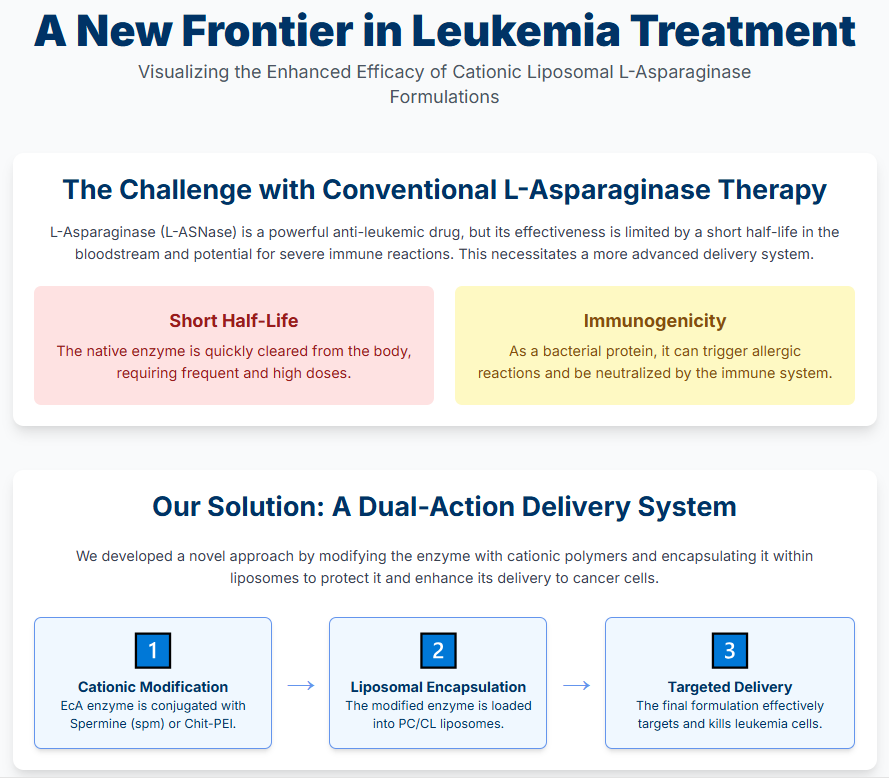

3.1. Design Rationale: Conjugate Synthesis and Liposomal Formulation

3.2. Physicochemical Characterization of Formulation

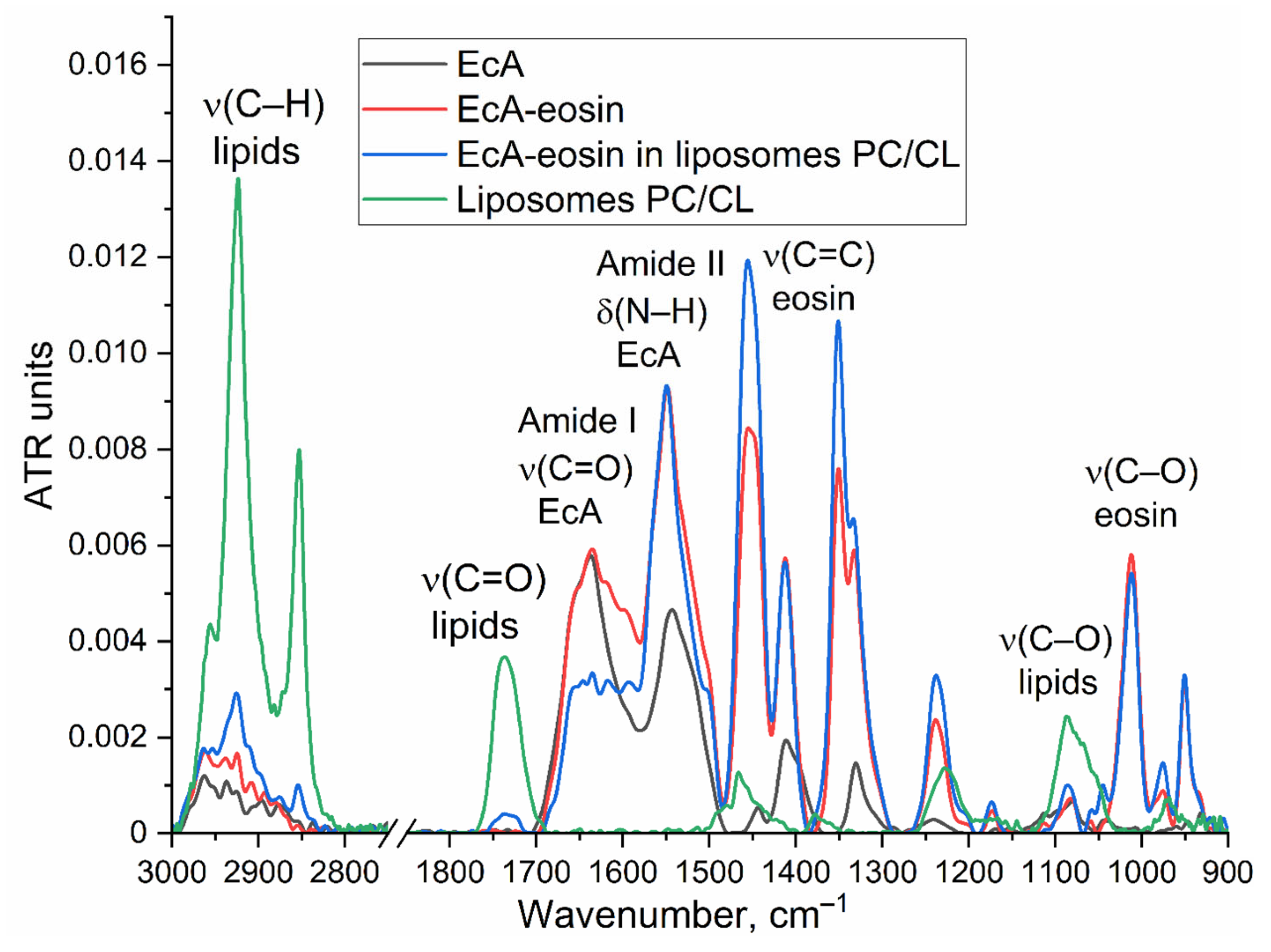

3.2.1. FTIR Spectroscopy

3.2.2. Loading Degree and Activity Studies

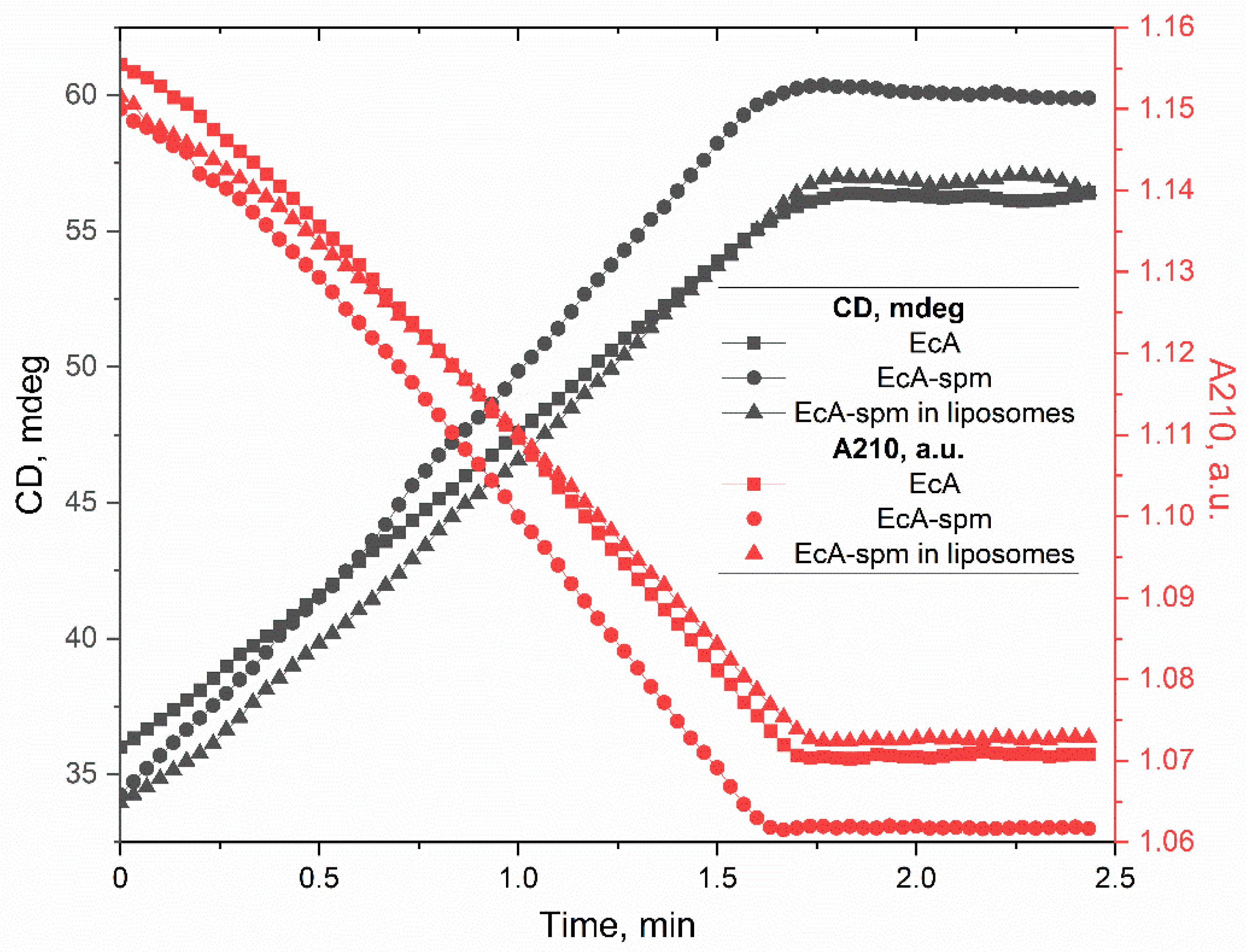

3.2.3. Circular Dichroism Spectra and Secondary Structure Analysis of EcA Formulations

3.3. In Vitro L-ASNase Release Kinetics

3.5. Cytotoxicity Evaluation of Liposomal Formulations of EcA and Its Conjugates

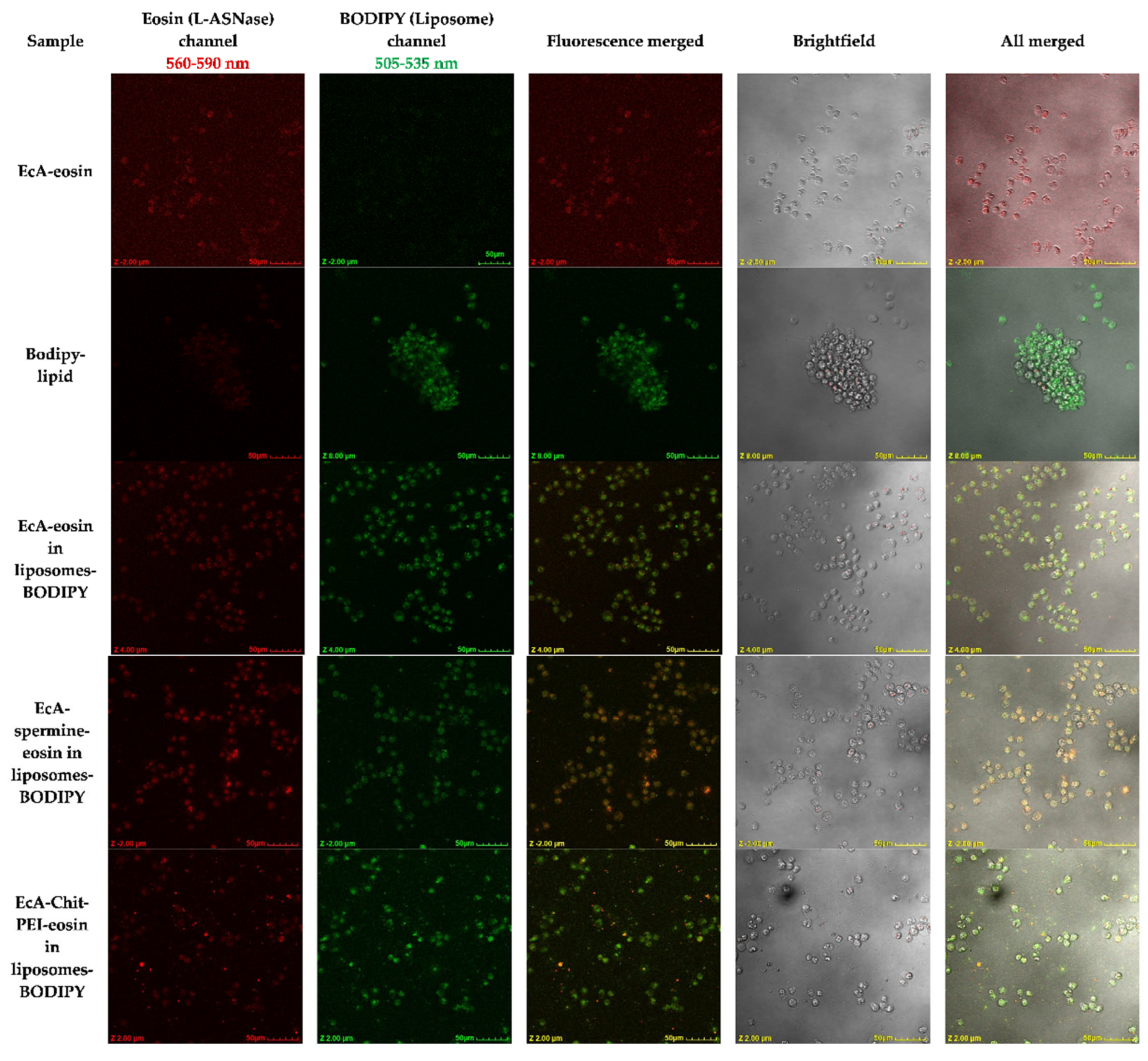

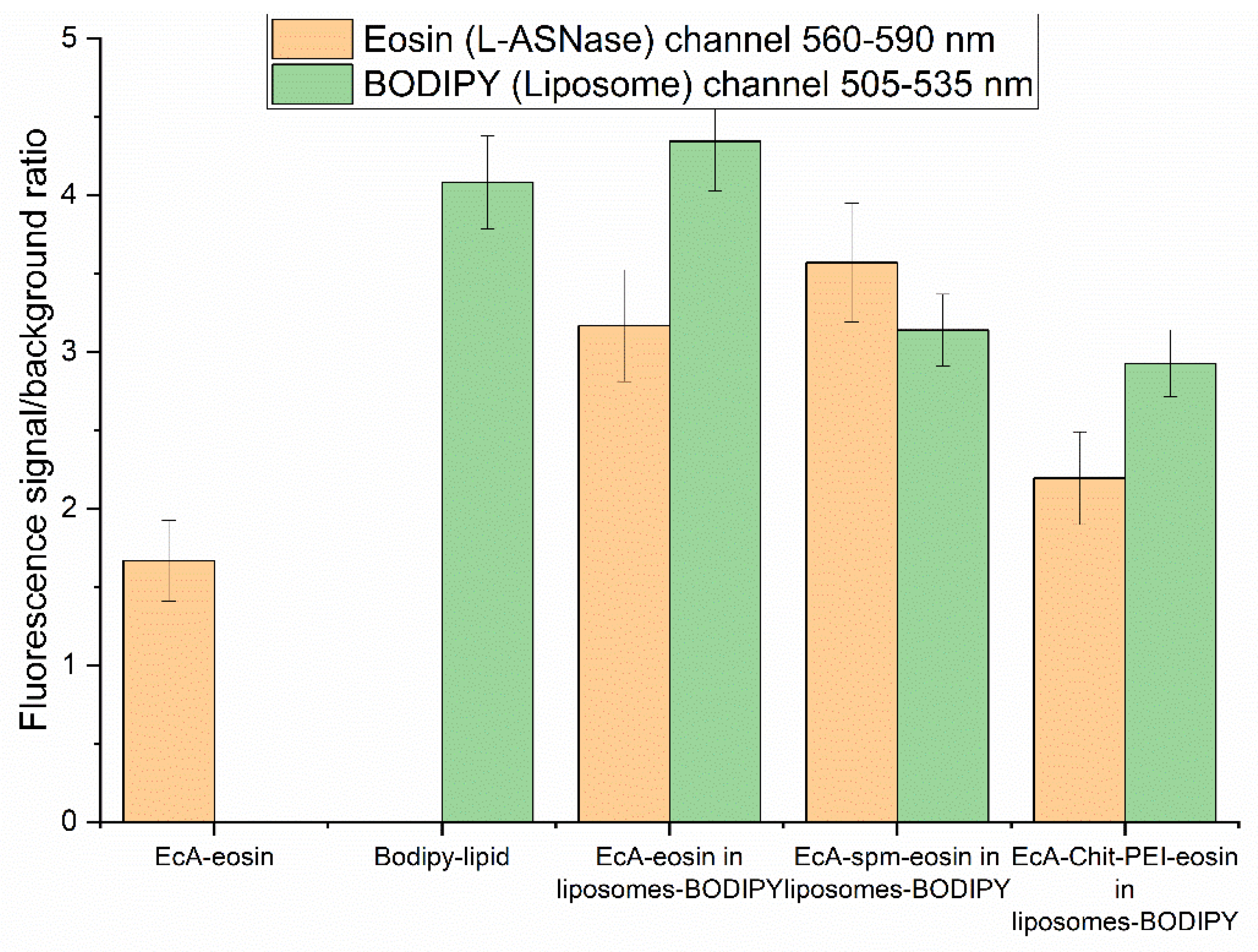

3.5. Cellular L-ASNase and Liposome Uptake and Colocalization by CLSM

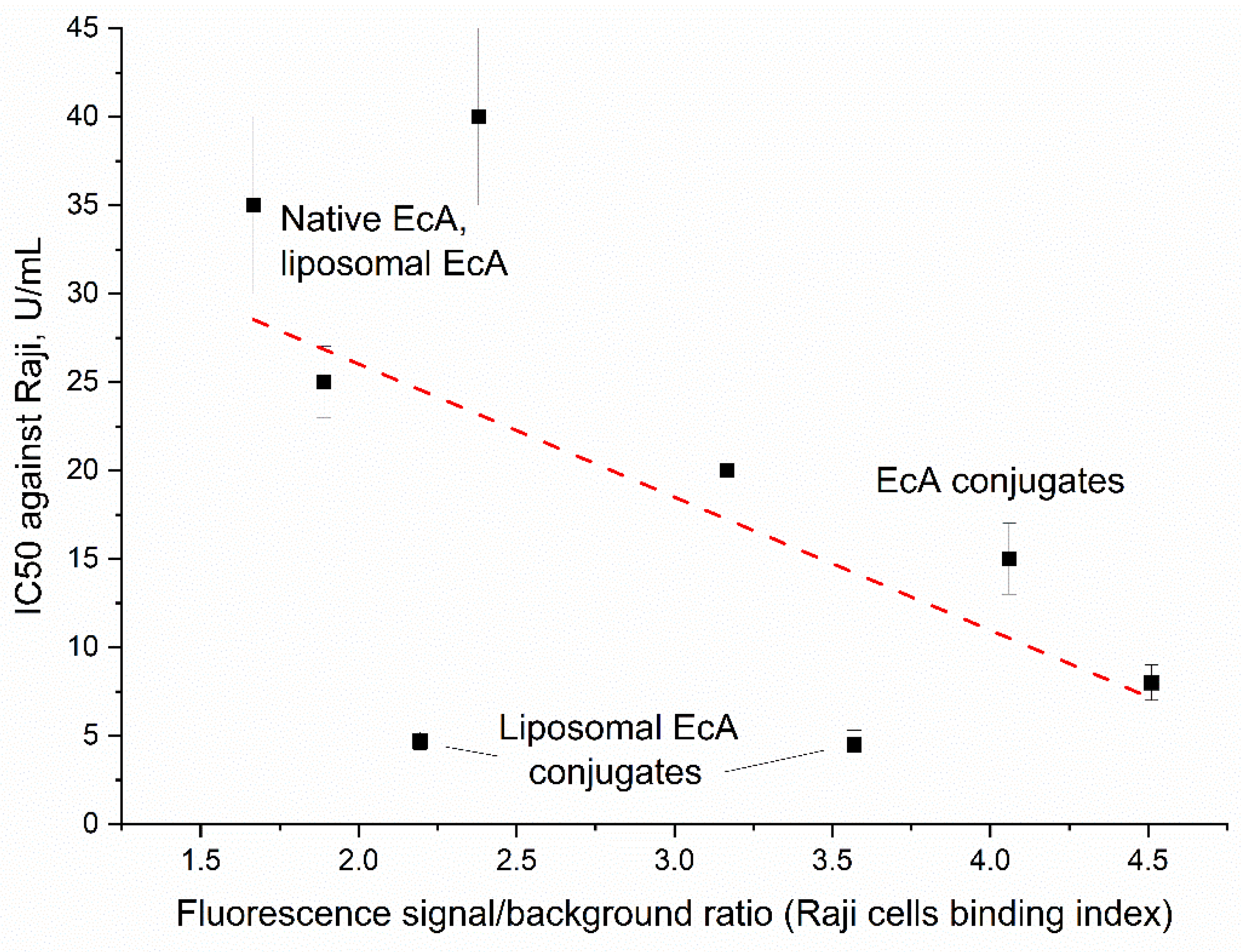

3.6. Correlation Between Binding to Raji Cells and Cytotoxicity of L-ASNase Formulations

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALL | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia |

| CD | Circular dichroism |

| CL | Cardiolipin |

| FTIR | Fourier-transform infrared |

| L-ASNase | L-asparaginase |

| PC | Phosphatidylcholine |

| PEG | Polyethylene glycol |

| spm | spermine |

References

- Wriston, J.C.; Yelln, T.O. L-Asparaginase : A Review. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol. 1973, 39, 185–248. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, M.P.; Ivanov, A.V.; Coriu, D.; Miron, I.C. L-Asparaginase Toxicity in the Treatment of Children and Adolescents with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Kudryashova, E. V A Novel Approach for the Activity Assessment of L-Asparaginase Formulations When Dealing with Complex Biological Samples. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piek, C.J.; Putteman, G.R.; Teske, E. Evaluation of the Results of a L-Asparaginase-Based Continuous Chemotherapy Protocol versus a Short Doxorubicin-Based Induction Chemotherapy Protocol in Dogs with Malignant Lymphoma. Vet. Q. 1999, 21, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, C.A.; Cai, X.; Elozory, A.; Liu, C.; Panetta, J.C.; Jeha, S. High-Throughput Asparaginase Activity Assay in Serum of Children with Leukemia. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2013, 6, 478–487. [Google Scholar]

- Simas, R.G.; Krebs Kleingesinds, E.; Pessoa Junior, A.; Long, P.F. An Improved Method for Simple and Accurate Colorimetric Determination of L-Asparaginase Enzyme Activity Using Nessler’s Reagent. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2021, 96, 1326–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsakova, D. V.; Sinauridze, E.I. L-Asparaginase: New Approaches to Improve Pharmacological Characteristics. Pediatr. Hematol. Immunopathol. 2018, 17, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moura, W.A.F.; Schultz, L.; Breyer, C.A.; de Oliveira, A.L.P.; Tairum, C.A.; Fernandes, G.C.; Toyama, M.H.; Pessoa-Jr, A.; Monteiro, G.; de Oliveira, M.A. Functional and Structural Evaluation of the Antileukaemic Enzyme L-Asparaginase II Expressed at Low Temperature by Different Escherichia Coli Strains. Biotechnol. Lett. 2020, 42, 2333–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juluri, K.R.; Siu, C.; Cassaday, R.D. Asparaginase in the Treatment of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Adults: Current Evidence and Place in Therapy. Blood Lymphat. Cancer Targets Ther. 2022, 12, 55–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakhova, M.A.; Pokrovskaya, M. V.; Alexandrova, S.S.; Sokolov, N.N.; Kudryashova, E. V. Regulation of Catalytic Activity of Recombinant L-Asparaginase from Rhodospirillum Rubrum by Conjugation with a PEG-Chitosan Copolymer. Moscow Univ. Chem. Bull. 2018, 73, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holcenberg, J.S.; Ericsson, L.; Roberts, J. Amino Acid Sequence of the Diazooxonorleucine Binding Site of Acinetobacter and Pseudomonas 7A Glutaminase--Asparaginase Enzymes. Biochemistry 1978, 17, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottobre, M.; Colitto, L.; Marcone, M.I.; Krystal, E.; Moran, L.; Wittmund, L.E.; Gimenez, V.; Makiya, M. A Pediatric Laboratory Experience: Measurement of L-Asparaginase Activity in Patients with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. a Multicentric Study. Blood 2024, 144, 2826–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubkowski, J.; Wlodawer, A. Structural and Biochemical Properties of L-Asparaginase. FEBS J. 2021, 288, 4183–4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrman, M.; Cedar, H.; Schwartz, J.H. L-Asparaginase II of Escherichia Coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1971, 246, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mashburn, L.T.; Wriston, J.C. Tumor Inhibitory Effect of L-Asparaginase from Escherichia Coli. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1964, 105, 450–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinndorf, P.A.; Gootenberg, J.; Cohen, M.H.; Keegan, P.; Pazdur, R. FDA Drug Approval Summary: Pegaspargase (Oncaspar) for the First-Line Treatment of Children with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL). Onkologist 2007, 12, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, H.J.; Beier, R.; Da Palma, J.; Lanvers, C.; Ahlke, E.; Von Schütz, V.; Gunkel, M.; Horn, A.; Schrappe, M.; Henze, G.; et al. PEG-Asparaginase (Oncaspar) 2500 u/M2 BSA in Reinduction and Relapse Treatment in the ALL/NHL-BFM Protocols. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2002, 49, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Würthwein, G.; Lanvers-Kaminsky, C.; Hempel, G.; Gastine, S.; Möricke, A.; Schrappe, M.; Karlsson, M.O.; Boos, J. Population Pharmacokinetics to Model the Time-Varying Clearance of the PEGylated Asparaginase Oncaspar® in Children with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2017, 42, 955–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinndorf, P.A.; Gootenberg, J.; Cohen, M.H.; Keegan, P.; Pazdur, R. FDA Drug Approval Summary: Pegaspargase (Oncaspar®) for the First-Line Treatment of Children with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL). Oncologist 2007, 12, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oncaspar, P.; Ettinger, A.R. Pharmacology. 1995, 46–48. [Google Scholar]

- Borghorst, S.; Hempel, G.; Poppenborg, S.; Franke, D.; König, T.; Baumgart, J. Comparative Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Characterisation of a New Pegylated Recombinant E. Coli L-Asparaginase Preparation (MC0609) in Beagle Dog. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2014, 74, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Ezhov, A.A.; Kudryashova, E. V. Receptor-Mediated Internalization of L-Asparaginase into Tumor Cells Is Suppressed by Polyamines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorselen, D.; Piontek, M.C.; Roos, W.H.; Wuite, G.J.L. Mechanical Characterization of Liposomes and Extracellular Vesicles, a Protocol. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukyanov, A.N.; Elbayoumi, T.A.; Chakilam, A.R.; Torchilin, V.P. Tumor-Targeted Liposomes: Doxorubicin-Loaded Long-Circulating Liposomes Modified with Anti-Cancer Antibody. J. Control. Release 2004, 100, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Guimarães, M.; Cachumba, J.J.M.; Bueno, C.Z.; Torres-Obreque, K.M.; Lara, G.V.R.; Monteiro, G.; Barbosa, L.R.S.; Pessoa, A.; Rangel-Yagui, C. de O. Peg-Grafted Liposomes for L-Asparaginase Encapsulation. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harijan, M.; Singh, M. Zwitterionic Polymers in Drug Delivery: A Review. J. Mol. Recognit. 2022, 35, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barenholz, Y. Doxil® - The First FDA-Approved Nano-Drug: Lessons Learned. J. Control. Release 2012, 160, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arranja, A.G.; Pathak, V.; Lammers, T.; Shi, Y. Tumor-Targeted Nanomedicines for Cancer Theranostics. Pharmacol. Res. 2017, 115, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, N.K.; Mishra, V.; Mehra, N.K. Targeted Drug Delivery to Macrophages. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2013, 10, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, M.E.M.; Gaspar, M.M.; Lopes, F.; Jorge, J.S.; Perez-Soler, R. Liposomal L-Asparaginase: In Vitro Evaluation. Int. J. Pharm. 1993, 96, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge, J.C.S.; Perez-Soler, R.; Morais, J.G.; Cruz, M.E.M. Liposomal Palmitoyl-L-Asparaginase: Characterization and Biological Activity. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 1994, 34, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, M.M.; Perez-Soler, R.; Cruz, M.E.M. Biological Characterization of L-Asparginase Liposomal Formulations. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 1996, 38, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, A.; Venkatesh, D.N. Design and Evaluation of Liposomal Delivery System for L-Asparaginese. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 2, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobryakova, N. V.; Zhdanov, D.D.; Sokolov, N.N.; Aleksandrova, S.S.; Pokrovskaya, M. V.; Kudryashova, E. V. Improvement of Biocatalytic Properties and Cytotoxic Activity of L-Asparaginase from Rhodospirillum Rubrum by Conjugation with Chitosan-Based Cationic Polyelectrolytes. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukhoverkov, K. V.; Sokolov, N.N.; Abakumova, O.Y.; Podobed, O. V.; Kudryashova, E. V. The Formation of Conjugates with PEG–Chitosan Improves the Biocatalytic Efficiency and Antitumor Activity of L-Asparaginase from Erwinia Carotovora. Moscow Univ. Chem. Bull. 2016, 71, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Kudryashova, E. V Targeted Polymeric Micelles System, Designed to Carry a Combined Cargo of L-Asparaginase and Doxorubicin, Shows Vast Improvement in Cytotoxic Efficacy. Polymers (Basel). 2024, 16, 2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobryakova, N. V.; Zhdanov, D.D.; Sokolov, N.N.; Aleksandrova, S.S.; Pokrovskaya, M. V.; Kudryashova, E. V. Rhodospirillum Rubrum L-Asparaginase Conjugates with Polyamines of Improved Biocatalytic Properties as a New Promising Drug for the Treatment of Leukemia. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; W. Lam, J.K. Endosomal Escape Pathways for Non-Viral Nucleic Acid Delivery Systems. Mol. Regul. Endocytosis 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Shishparyonok, A.N.; Pokrovskaya, M. V; Alexandrova, S.S.; Zhdanov, D.D.; Kudryashova, E. V Structural Features Underlying the Mismatch Between Catalytic and Cytostatic Properties in L-Asparaginase from Rhodospirillum Rubrum. Catalysts 2025, 15, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudryashova, E. V.; Sukhoverkov, K. V. “Reagent-Free” l-Asparaginase Activity Assay Based on CD Spectroscopy and Conductometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2016, 408, 1183–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| L-ASNase entrapment efficiency, % | EcA | EcA-spm | EcA-PEI-g-PEG |

| In PC/Cl 80/20 100 nm liposomes | 63±2 | 89±1 | 82±2 |

| In PC/Cl 80/20 400 nm liposomes | 70±5 | 97±1 | 94±1 |

| Final L-ASNase / lipid ratio, µg/µmol | EcA | EcA-spm | EcA-PEI-g-PEG |

| In PC/Cl 80/20 100 nm liposomes | 85±3 | 120±2 | 111±3 |

| In PC/Cl 80/20 400 nm liposomes | 95±7 | 131±2 | 127±2 |

| L-ASNase activity, U/mg | EcA | EcA-spm | EcA-PEI-g-PEG |

| Non liposomal | 330±20 | 380±14 | 327±15 |

| In PC/Cl 80/20 100 nm liposomes | 355±18 | 365±13 | 306±22 |

| In PC/Cl 80/20 400 nm liposomes | 364±23 | 370±25 | 350±18 |

| L-ASNase residual activity after a month of storage at +4 °C in PBS, U/mg | EcA | EcA-spm | EcA-PEI-g-PEG |

| Non liposomal | 208 (63% from initial) | 315 (83% from initial) | 245 (75% from initial) |

| In PC/Cl 80/20 100 nm liposomes | 298 (84% from initial) | 339 (93% from initial) | 278 (91% from initial) |

| In PC/Cl 80/20 400 nm liposomes | 280 (77% from initial) | 333 (90% from initial) | 284 (81% from initial) |

| Parameter | EcA | EcA in liposomes | EcA-spm in liposomes | EcA-PEI-g-PEG in liposomes |

| T50%, min | 24±2 | 45±5 | 56±7 | 70±5 |

| T80%, min | 52±5 | 240±20 | 330±35 | 420±50 |

| IC50, U/mL | EcA | EcA-spm | EcA-Chit-PEI |

| Non liposomal | 35±5 | 8±1 | 7±1 |

| In PC/Cl 80/20 100 nm liposomes | 20±5 | 4.5±0.8 | 4.7±0.5 |

| In PC/Cl 80/20 400 nm liposomes | 9±2 | 11±1 | 13±2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).