Introduction

As we go deeper into understanding the word ‘cognition’, you could stumble upon some interesting revelations about the word. The term cognition, rooted in the Latin cognitio (from cognoscere, “to know”), refers to the ensemble of mental processes involved in acquiring, processing, and applying knowledge. In contemporary psychology, it encompasses a broad spectrum of functions, including perception, memory, reasoning, and decision-making, all of which are integral to human understanding and adaptive behavior (Neisser, 1967).

A compelling parallel emerges when we consider the Sanskrit root ज्ञ (jñā), which similarly denotes knowledge, awareness, and insight. This root forms the basis of several key concepts in Indian philosophical and psychological traditions, such as ज्ञान (jñāna)—knowledge, प्रज्ञा (prajñā)—wisdom or intuitive insight, and अज्ञ (ajña)—ignorance. These terms represent consciousness and its various features that have been central to Indic thought since ancient times, particularly in Vedānta, Buddhist Abhidharma, and Jain epistemological frameworks (Dasgupta, 1991; Matilal, 1986). The phonetic complexity and semantic alignment of these forms—each oriented toward the act of knowing—suggest not merely a coincidental resemblance but a shared linguistic and conceptual heritage.

Beyond their etymological convergence, these traditions also reflect parallel epistemological concerns. In the Latin West, cognitio informed medieval scholastic debates about perception, abstraction, and intellectual apprehension, particularly in the works of Augustine and Aquinas (Kenny, 2010). In India, theories of pramāṇa (valid means of knowledge) provided a systematic account of perception (pratyakṣa), inference (anumāna), and testimony (śabda) as channels of reliable cognition (Matilal, 1986). Both traditions, in their own ways, sought to clarify how human beings come to know truth and distinguish it from error.

From Cognition to Metacognition

This cross-cultural concern with knowing naturally extends into the domain of metacognition, or the capacity to reflect on and regulate one’s own cognitive processes. Modern psychology defines metacognition as “thinking about thinking,” encompassing both monitoring (awareness of one’s cognitive states) and control (strategically guiding thought and learning) (Flavell, 1979; Nelson & Narens, 1990).

Intriguingly, premodern traditions anticipated this higher-order awareness. Several thinkers have emphasized the mind’s capacity to turn inward and recognize its own acts of knowing. Indic traditions distinguish between jñāna as knowledge and prajñā as higher discernment or wisdom—a faculty that not only knows but also evaluates and transforms knowing (Sharma S, 1998). In Buddhist thought, prajñā entails insight into the impermanent and conditioned nature of cognition itself (Dreyfus, 1997). However, in this paper, there is an effort to orient the readers with the ideas of Meta Cognition & Mindfulness and bridge their concepts and theories and see if there is any coherence with the verses from the Indian text of Shrimad Bhagvad Gita.

Meta Cognition:

Metacognition is defined as the awareness and regulation of one’s own thought processes. In simple words, its “thinking about thinking”. Martinez, M. E. (2006) in his article mentions that Metacognition serves many diverse functions. He further identified three major categories of metacognition: metamemory and metacomprehension, problem solving, and critical thinking. Although he did not limit the types of Meta Cognition to these three categories, it does communicate the broad role of the process in important cognitive endeavors. As per Lai, E (2011) Metacognition consists of two components: Knowledge and Regulation wherein Metacognitive knowledge includes knowledge about oneself as a learner and the factors that might impact performance, knowledge about strategies, and knowledge about when and why to use strategies. Metacognitive regulation is the monitoring of one’s cognition and includes planning activities, awareness of comprehension and task performance, and evaluation of the efficacy of monitoring processes and strategies.

John Flavell is believed to have coined the term Metacognition. In his paper titled Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive–developmental inquiry. Flavell, J. H. (1979) conveys that Metacognitive knowledge is one's stored knowledge or beliefs about oneself and others as cognitive agents, about tasks, about actions or strategies, and about how all these interact to affect the outcomes of any sort of intellectual enterprise. Metacognitive experiences are conscious cognitive or affective experiences that occur during the enterprise and concern any aspect of it—often, how well it is going.

Over the time, the idea of metacognition has remained close to its original meaning, though researchers describe it in slightly different ways. In cognitive psychology, it is often defined as the ability to recognize and guide one’s own thinking and learning. For example, Cross and Paris (1988) highlight it as children’s knowledge and control of their learning processes, while Hannessey (1999) emphasizes active monitoring of thoughts, regulating them for better learning, and applying strategies to solve problems. Other definitions are more concise, such as Kuhn and Dean’s (2004) description of metacognition as awareness and management of thought, or Martinez’s (2006) framing of it as the monitoring and control of thought.

Kuhn and Dean (2004) further explain that metacognition is what allows learners to apply strategies taught in one situation to a different but related context. In this way, it is frequently understood as a form of executive control involving both monitoring and self-regulation (McLeod, 1997; Schneider & Lockl, 2002). Schraw (1998) adds that metacognition consists of a broad set of skills that are not tied to one specific domain, and these skills are distinct from general intelligence. In fact, they can sometimes help learners overcome weaknesses in prior knowledge or cognitive ability when solving problems.

Key Elements of Metacognition

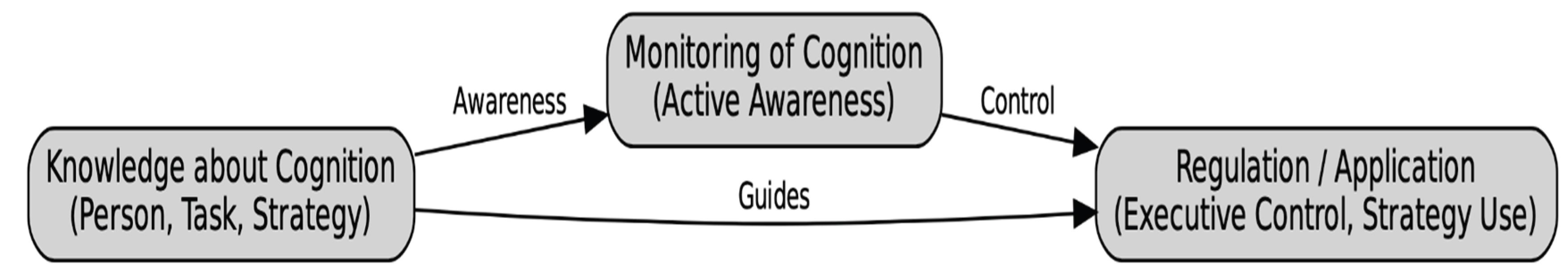

Most researchers agree that metacognition consists of two main components: knowledge about cognition and regulation of cognition (Cross & Paris, 1988; Flavell, 1979; Paris & Winograd, 1990; Schraw & Moshman, 1995; Schraw et al., 2006; Whitebread et al., 1990). Flavell (1979) explains that knowledge about cognition involves understanding one’s strengths and weaknesses as a thinker and recognizing the factors that affect performance. He divides this knowledge into three categories: (1) person knowledge, or beliefs about oneself and others as thinkers; (2) task knowledge, or awareness of the demands of different tasks; and (3) strategy knowledge, or knowing which approaches are most useful for particular tasks. These categories often overlap—for example, knowing that one should use a certain strategy for one type of problem but not another.

Figure 1.

Exhibits the framework of knowledge, monitoring and application.

Figure 1.

Exhibits the framework of knowledge, monitoring and application.

Mindfulness:

Mindfulness has traveled a fascinating journey—from ancient contemplative practices in Buddhist and Vedic traditions to its current place in psychology labs, therapy rooms, and even boardrooms. At its simplest, mindfulness is the practice of intentionally paying attention to one’s experiences in the present moment, without judgment (Kabat-Zinn, 1990). Sounds simple, almost obvious—yet research repeatedly shows that this deliberate awareness can reshape how we think, feel, and act.

Mindfulness refers to a state of focused awareness in which one pays attention to present-moment experiences with openness and non-judgment. Bishop et al. (2004) describe it as involving two key components: regulation of attention(sustained, flexible focus) and orientation toward experience (acceptance, curiosity, and openness). Creswell (2017) further emphasizes that mindfulness practices strengthen executive functions, reduce stress, and improve emotional balance

What makes mindfulness exciting is its ability to balance two worlds: the soft art of presence and the hard science of measurable outcomes. Studies suggest it enhances emotional regulation, reduces stress, and even improves working memory (Tang, Hölzel, & Posner, 2015). In clinical psychology, mindfulness-based interventions have become evidence-based tools for addressing anxiety, depression, and relapse prevention.

And here’s the beautiful paradox: mindfulness is not about “achieving” anything—it’s about noticing. Noticing the breath, the fleeting thought, the body’s signals. This humble noticing, however, has profound consequences. Neuroscientific research shows that mindfulness practice can alter the structure and function of brain regions linked to attention, compassion, and self-awareness (Hölzel et al., 2011).

In a way, mindfulness invites us to become curious tourists of our own minds—exploring without rushing, judging, or overpacking with expectations. That jovial curiosity, grounded in centuries of tradition and decades of science, makes mindfulness less of a trend and more of a timeless skill for human flourishing.

Merging Mindfulness with Metacognition

Apart from both the words starting from the alphabet M, there are different ways how Metacognition & Mindfulness are interrelated. Hussain, D. (2015) in his article published in Psychological Thought explores the conceptual relationship between meta-cognition and mindfulness, showing how both traditions, though developed independently, share common mechanisms like meta-awareness. In his article, he argues that integrating insights from each can enrich theoretical understanding and improve applied practices such as psychotherapy. Ultimately, the paper suggests that meta-cognition and mindfulness are complementary, and their integration may strengthen approaches to human well-being. Kudesia, R. S. (2019) reframes mindfulness as a metacognitive practice—a flexible process of adjusting information processing to fit situational demands, supported by specific beliefs cultivated through training. At the organizational level, this practice can either amplify collective transformation or contribute to fragmentation, depending on how it is enacted.

There are more studies integrating mindfulness and meta cognition. One of the remarkable exploration by Norman, E. (2017) is how mindfulness involves a special kind of metacognitive experience known as fringe consciousness—vague, transient feelings like familiarity, novelty, or rightness that reflect unconscious cognitive processes. It argues that mindfulness practice may heighten sensitivity to such subtle experiences and reshape one’s attitude toward them, making unconscious material more accessible. The study also highlights how feelings of novelty, often central to mindfulness, can be understood within this framework, offering deeper insight into its mechanisms and effects.

Integrating Meta-Cognitive and Mindfulness Approaches - from the lens of Shrimad Bhagvad Gita

The above studies clearly emphasizes that mindfulness and metacognition, though historically developed in separate traditions, share profound commonalities such as meta-awareness, cognitive decentering, and reflective regulation. While the scientific tradition of mindfulness has often drawn from Buddhist meditative practices, it is equally important to recognize that the Indian philosophical tradition, particularly the Shrimad Bhagavad Gītā, offers a profound integration of these ideas. The Gītā anticipates the very principles that modern psychology associates with mindfulness and metacognition such as presence (sākṣibhāva), regulation (yukti), detachment (vairāgya), cognitive reflection (buddhi), novelty (nava-darśana), and intentionality (saṅkalpa). To deepen this dialogue, it is illuminating to turn to the Shrimad Bhagavad Gita. The Gita’s philosophical discourse between Lord Krishna and Arjuna exemplifies how mindfulness (sākṣibhāva, present awareness) and metacognition (buddhi–manas regulation, or thinking about thinking) are not merely abstract constructs but practical tools for psychological balance and spiritual growth. Here are a few perspectives that could validate this point of view.

1. Meta-Awareness and Witness Consciousness (साक्षिभावः – sākṣibhāvaḥ)

Modern psychology defines meta-awareness as the ability to recognize the content of one’s own mind from a detached standpoint. Studies show that people often catch themselves mind-wandering, and this “noticing” is considered meta-awareness. When executive control fails, thoughts arise automatically and carry our attention away. The corrective mechanism is meta-awareness — the ability to notice that wandering. The higher and more stable form of meta-awareness is evident in the form of witness consciousness. Witness consciousness in Indian philosophy is essentially a cultivated and sustained form of that meta-awareness. Instead of just catching lapses, it is a deeper stance of observing all mental activity — thoughts, emotions, sensations — without identification or attachment. The Gītā articulates this as sākṣibhāva, the cultivation of a witness consciousness that observes mental fluctuations without being absorbed in them.

श्लोकः (Bhagavad Gītā 13.23):

उपद्रष्टानुमन्ता च भर्ता भोक्ता महेश्वरः।

परमात्मेति चाप्युक्तो देहेऽस्मिन्पुरुषः परः॥

Upadraṣṭānumantāca bhartābhoktāmaheśvaraḥ,

Paramātmeti cāpy ukto dehe’smin puruṣaḥ paraḥ.

Translation:

“Within the body also resides the Supreme, who is the observer, the permitter, the supporter, the experiencer, the great Lord, and ultimately the Supreme Self.”

In the above Shloka from Chapter 13 The word उपद्रष्टा (upadraṣṭā) — the observer — aligns directly with the idea of witness consciousness, where one becomes aware of mental processes without judgment. In psychological terms, this corresponds to meta-awareness: the recognition that thoughts, emotions, and actions are occurring, while simultaneously knowing that one is distinct from them. This mirrors mindfulness’s observing stance and metacognition’s self-monitoring function, both of which rely on the ability to witness inner processes rather than be consumed by them.

2. Cognitive Regulation and Cognitive Balance (युक्तता – yuktatā)

In contemporary psychology, metacognition is often described as a higher-order process that enables individuals to plan, monitor, and regulate their own cognitive activities. It allows a person to set intentions, track mental performance, and adjust strategies to maintain efficiency and clarity of thought. Similarly, in the practice of mindfulness, regulation takes the form of maintaining balance—neither suppressing thoughts and emotions nor being overwhelmed by them, but sustaining an even awareness that fosters harmony between inner states and external demands.

The Bhagavad Gītā offers a striking parallel through the concept of युक्तता (yuktatā), which can be translated as harmonious regulation, balance, and disciplined integration. This principle is not limited to isolated mental exercises but is envisioned as a comprehensive framework for living—balancing work, rest, diet, social duties, and spiritual practices. Such regulation is portrayed as the foundation of yoga and, by extension, of self-mastery.

One of the most illustrative verses is:

श्लोकः(Bhagavad Gītā6.17):युक्ताहारविहारस्य युक्तचेष्टस्य कर्मसु।

युक्तस्वप्नावबोधस्य योगो भवति दुःखहा॥

Yuktāhāra-vihārasya yukta-ceṣṭasya karmasu,

Yukta-svapnāvabodhasya yogo bhavati duḥkha-hā.

“For one who is regulated in eating, recreation, work, and sleep, yoga becomes the destroyer of sorrow.”

This verse captures the essence of mindful regulation and metacognitive balance. Regulation here is not rigid control but a flexible self-monitoring that prevents extremes and nurtures stability. In cognitive terms, it parallels the idea of executive functioning, where metacognitive strategies help maintain equilibrium in thought and action. In mindfulness terms, it represents the cultivation of moderation and intentionality across all spheres of life, which protects the practitioner from the mental turbulence of excess or deficiency.

Another complementary verse reinforces this principle:

श्लोकः(Bhagavad Gītā5.7):

योगयुक्तो विशुद्धात्मा विजितात्मा जितेन्द्रियः।

सर्वभूतात्मभूतात्मा कुर्वन्नपि न लिप्यते॥

Yoga-yukto viśuddhātmā vijitātmā jitendriyaḥ,

Sarva-bhūtātma-bhūtātmākurvann api na lipyate.

“One who is harmonized by yoga, whose self is pure, who has mastered the self and conquered the senses, who sees the Self in all beings—though acting, such a one is never entangled.”

This verse extends the meaning of yuktatā beyond lifestyle moderation to inner mastery—regulation of the senses, purification of the self, and maintaining cognitive-emotional balance even amidst worldly action. It is a sophisticated articulation of cognitive regulation: while engaging fully in external duties (kurvan api), the practitioner does not become cognitively or emotionally entangled (na lipyate). Thus, yuktatā in the Gītā provides a framework remarkably similar to the dual functions of mindfulness and metacognition

3. Detachment and Cognitive Decentering (वैराग्यम् – vairāgyam)

One of the core contributions of modern cognitive-behavioral and metacognitive therapies is the concept of decentering—the ability to step back and perceive thoughts not as absolute truths, but as passing mental events. This shift in perspective reduces over-identification with cognitive content and allows individuals to respond to situations with greater flexibility rather than rigid reactivity. In parallel, mindfulness emphasizes a non-judgmental stance: thoughts and emotions are observed as temporary phenomena, neither clung to nor resisted.

The Bhagavad Gītā articulates this very principle through the doctrine of वैराग्यम् (vairāgyam), or detachment. Detachment here does not imply indifference or disengagement from life, but rather a balanced state in which one performs duties wholeheartedly while relinquishing undue attachment to their outcomes. This attitude fosters psychological resilience, emotional regulation, and inner clarity.

A key verse that captures this principle is:

श्लोकः(Bhagavad Gītā2.48):

योगस्थः कुरु कर्माणि सङ्गं त्यक्त्वा धनञ्जय।

सिद्ध्यसिद्ध्योः समो भूत्वा समत्वं योग उच्यते॥

Yogasthaḥkuru karmāṇi saṅgaṃtyaktvādhanañjaya,

Siddhy-asiddhyoḥsamo bhūtvāsamatvaṃyoga ucyate.

Translation:

“Be steadfast in yoga, O Arjuna. Perform your duty, abandoning attachment, and remain balanced in success and failure. Such equanimity is called yoga.”

Here, the Gītā emphasizes योगस्थः (yogasthaḥ)—remaining established in yoga, which can be understood as a mindful, present-centered awareness. The instruction to abandon attachment (सङ्गं त्यक्त्वा) reflects a metacognitive stance: recognizing that outcomes are not fully within one’s control and reframing one’s relationship to them. The call to be equanimous in success and failure (सिद्ध्यसिद्ध्योः समो भूत्वा) resonates with mindfulness’s non-judgmental awareness—allowing both pleasant and unpleasant experiences to arise without over-identification or aversion.

Another verse resonating this principle:

श्लोकः (Bhagavad Gītā 2.47)

कर्मण्येवाधिकारस्ते मा फलेषु कदाचन।

मा कर्मफलहेतुर्भूर्मा ते सङ्गोऽस्त्वकर्मणि॥

Karmaṇy-evādhikāras te māphaleṣhu kadācana,

Mākarma-phala-hetur bhūr māte saṅgo’stvakarmaṇi.

Translation:

“You have a right to perform your prescribed duties, but never to the fruits of your actions. Let not the fruits of action be your motive, nor let your attachment be to inaction.”

The verse teaches the principle of acting without clinging to results, which aligns with the cognitive-behavioral idea of decentering—shifting focus from outcome-driven thinking to process-oriented engagement. मा फलेषु कदाचन (mā phaleṣhu kadācana) — “never to the fruits” — reflects the mindful practice of observing outcomes without over-identification. मा ते सङ्गः अस्तु अकर्मणि (mā te saṅgaḥ astu akarmaṇi) — “do not get attached to inaction” — warns against avoidance, highlighting that detachment is not withdrawal but balanced participation.

This is a psychological reminder that thoughts, outcomes, and judgments are transient events; one must act with awareness but avoid being consumed by the mental projections of success or failure.

In mindfulness, detachment is cultivated by observing thoughts and emotions as passing experiences. This develops equanimity (samatva), reducing reactivity. In metacognition, decentering allows one to recognize thoughts as “mental events” rather than facts. This fosters flexibility, reduces cognitive distortions, and promotes adaptive coping. In the Gītā’s vairāgyam, detachment does not mean passivity—it is an active engagement with life coupled with inner freedom from overdependence on results.

Thus, the Gītā extends the psychological notion of decentering into a broader existential framework: by anchoring oneself in yoga (awareness + discipline), one engages fully in action while remaining liberated from the bondage of outcomes. This represents a sophisticated integration of mindfulness and metacognition—a way of acting consciously in the world while maintaining cognitive and emotional balance within.

Conclusion

This paper set out to move toward an Indian-inspired framework of self-regulation by integrating insights from metacognition, mindfulness, and the Shrimad Bhagavad Gītā. The analysis has demonstrated that while mindfulness and metacognition emerged as distinct constructs within modern psychology, they share foundational mechanisms such as meta-awareness, regulation, decentering, and reflective intentionality. When examined through the lens of the Bhagavad Gītā, these constructs find not only conceptual parallels but also a deeper, value-oriented grounding that situates them within a larger vision of self-mastery and liberation.

At the heart of this integration lies the principle of self-regulation. In contemporary psychology, self-regulation is understood as the ability to monitor, manage, and adapt cognitive, emotional, and behavioral processes in alignment with personal goals. Mindfulness contributes to this process by cultivating non-judgmental awareness of present experience, while metacognition provides the tools for reflective monitoring and control of thought processes. The Gītā enriches this model by offering indigenous categories that map onto these functions: साक्षिभाव (sākṣibhāva – witness consciousness) reflects meta-awareness, युक्तता (yuktatā – cognitive regulation and balance) mirrors mindful self-monitoring, and वैराग्यम् (vairāgyam – detachment) captures the spirit of cognitive decentering. Together, these principles form a robust framework for self-regulation that is both scientifically grounded and philosophically expansive.

The Bhagavad Gītā’s contribution is particularly significant in extending the scope of self-regulation beyond therapeutic and cognitive outcomes to include ethical action and existential clarity. Krishna’s repeated injunctions to act without attachment (BG 2.47, 2.48) exemplify how regulation is not merely about controlling mental states but about cultivating a way of being in which action is harmonized with awareness and guided by higher intention. This emphasis situates self-regulation not just as a psychological competence but as a spiritual discipline that integrates mind, behavior, and purpose.

An Indian-inspired framework of self-regulation therefore contributes two critical elements to contemporary discourse: wholeness and transcendence. Wholeness emerges from the Gītā’s insistence on balance (yuktatā) across domains of life—work, rest, relationships, and contemplation. Transcendence arises from its vision of detachment (vairāgyam), where the individual is not enslaved by thoughts, outcomes, or desires, but operates from a space of freedom and clarity. These principles resonate with but also extend beyond Western psychological constructs, offering a more integrative approach that acknowledges both the functional and existential dimensions of human growth.

In conclusion, this paper proposes that the integration of mindfulness, metacognition, and the philosophical insights of the Bhagavad Gītā offers a culturally rooted yet universally relevant model of self-regulation. Such a framework provides a balanced synthesis: mindfulness cultivates presence, metacognition refines reflection, and the Gītā anchors both within a vision of disciplined, purposeful, and liberated action. By bridging modern psychological science with Indian philosophical wisdom, this framework not only deepens our understanding of self-regulation but also opens pathways for developing practices and interventions that honor cultural traditions while addressing contemporary challenges of mental health, resilience, and flourishing.

References

- Bishop, S. R.; Lau, M.; Shapiro, S.; Carlson, L.; Anderson, N. D.; Carmody, J.; Devins, G. Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical psychology: Science and practice 2004, 11(3), 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidbhavananda, Swami. The Bhagavad Gita, 1st ed.; Sri Ramakrishna Tapovanam, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. D. Mindfulness interventions. Annual Review of Psychology 2017, 68, 491–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, D. R.; Paris, S. G. Developmental and instructional analyses of children’s metacognition and reading comprehension. Journal of Educational Psychology 1988, 80(2), 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, S. A History of Indian Philosophy; 1991; Vol. 1, Original work published 1922. [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfus, G. Recognizing Reality: Dharmakīrti’s Philosophy and Its Tibetan Interpretations; SUNY Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Flavell, J. H. Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive–developmental inquiry. American Psychologist 1979, 34(10), 906–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, D. Meta-cognition in mindfulness: A conceptual analysis. Psychological Thought 2015, 8(2), 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessey, M. G. Probing the dimensions of metacognition: Implications for conceptual change teaching-learning. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching, Boston, MA; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hölzel, B. K.; Lazar, S. W.; Gard, T.; Schuman-Olivier, Z.; Vago, D. R.; Ott, U. How Does Mindfulness Meditation Work? Proposing Mechanisms of Action From a Conceptual and Neural Perspective. In a journal of the Association for Psychological Science; Perspectives on psychological science, 2011; Volume 6, 6, pp. 537–559. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Full catastrophe living; New York, NY; Delta Publishing, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, D.; Dean, D. A bridge between cognitive psychology and educational practice. Theory into Practice 2004, 43(4), 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, A. A New History of Western Philosophy; Oxford University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, E. Metacognition: A Literature Review Research Report, 2011.

- McLeod, L. Young children and metacognition: Do we know what they know they know? And if so, what do we do about it? Australian Journal of Early Childhood 1997, 22(2), 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matilal, B. K. Perception: An Essay on Classical Indian Theories of Knowledge; Oxford University Press, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, M. E. What is Metacognition? Phi Delta Kappan 2006, 87(9), 696–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neisser, U. Cognitive Psychology; Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, T. O.; Narens, L. Metamemory: A theoretical framework and new findings. The Psychology of Learning and Motivation 1990, 26, 125–173. [Google Scholar]

- Paris, S. G.; Winograd, P. Promoting metacognition and motivation of exceptional children. Remedial and Special Education 1990, 11(6), 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraw, G. Promoting general metacognitive awareness. Instructional Science 1998, 26(1-2), 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraw, G.; Moshman, D. Metacognitive theories. Educational Psychology Review 1995, 7(4), 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraw, G.; Crippen, K. J.; Hartley, K. Promoting self-regulation in science education: Metacognition as part of a broader perspective on learning. Research in Science Education 2006, 36, 111–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, W.; Lockl, K. Perfect, T., Schwartz, B., Eds.; The development of metacognitive knowledge in children and adolescents. In Applied metacognition; Cambridge, UK; Cambridge University Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Brahmavarchas. Chetan, Achetan evam Super Chetan Man. Pandit Shriram Sharma Acharya samagra vangamaya, revised ed.; Mathura, Uttar Pradesh, India; Akhand Jyoti Sansthan, 2012; volume 22. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y. Y.; Hölzel, B. K.; Posner, M. I. The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nature reviews. Neuroscience 2015, 16(4), 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitebread, David; Coltman, Penny; Pino-Pasternak, Deborah; Sangster Jokić, Claire; Grau, Valeska; Bingham, Sue; Almeqdad, Qais; Demetriou, Demetra. The development of two observational tools for assessing metacognition and self-regulated learning in young children. Metacognition and Learning 2008, 4, 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).