Submitted:

03 September 2025

Posted:

05 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Understanding the success of romantic relationships remains a complex scientific challenge with significant implications for modern Western societies. In particular, the mechanisms underlying successful relationships —those that are both long-term and emotionally fulfilling— are still not fully understood, especially regarding the role of psychological and environmental factors in shaping their evolution. This gap is partly due to the limited availability of long-term data on marital quality. In this paper, we use a differential game model to replicate the long-term dynamics of successful relationships. We analytically characterize how variations in each partner's subjective evaluation of emotional rewards and costs influence key relational outcomes, such as equilibrium effort levels, overall happiness, and relationship quality. Through numerical simulations, we further explore how asymmetries in emotional processing between partners affect optimal effort policies and individual happiness. Notably, our results suggest that one’s own emotional traits exert a stronger influence on relationship satisfaction than those of one’s partner, aligning with findings from relationship science.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

Differential Love Games: Theoretical Model

A Computational Feedback Model of Differential Love Games

3. Results and Discussion

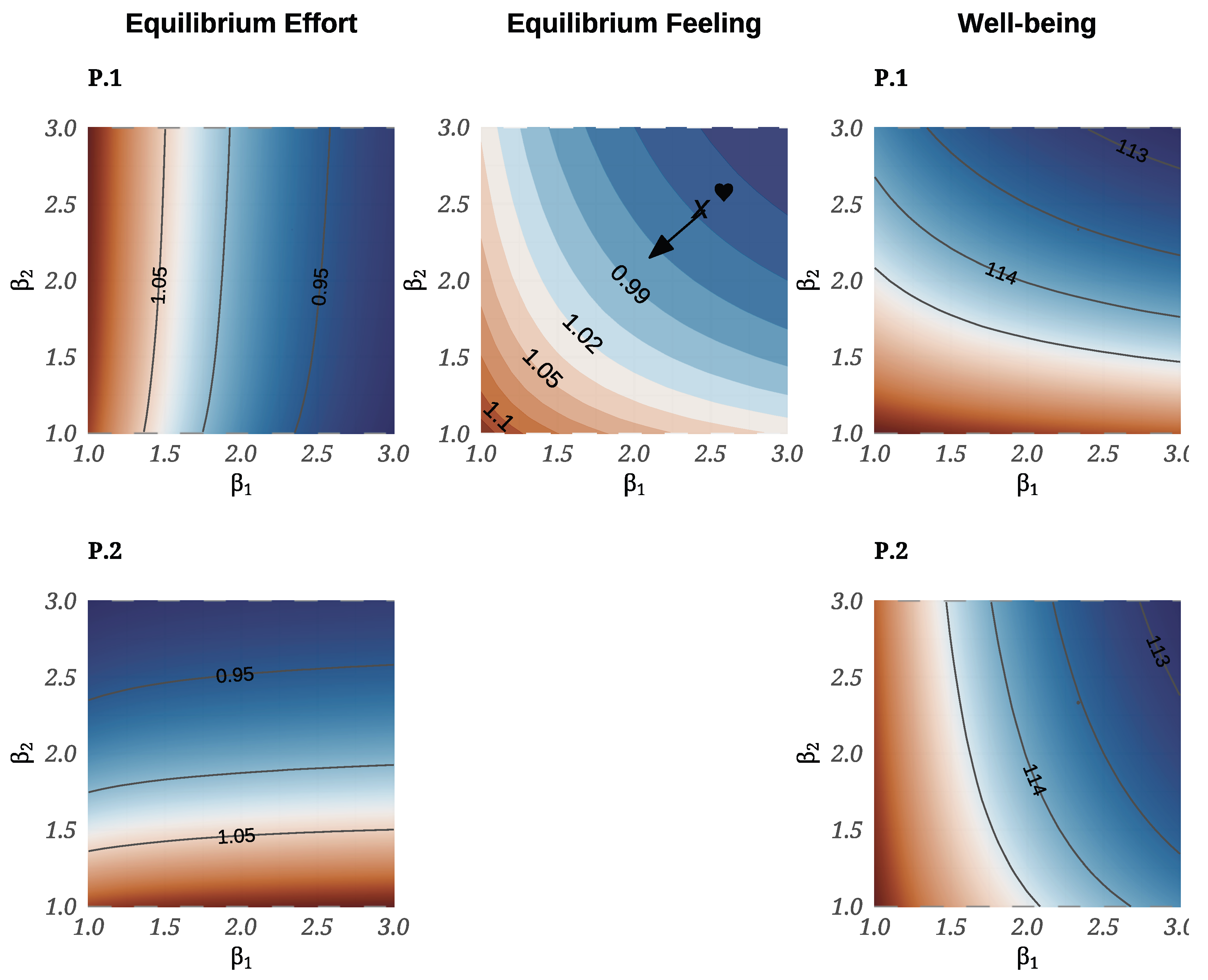

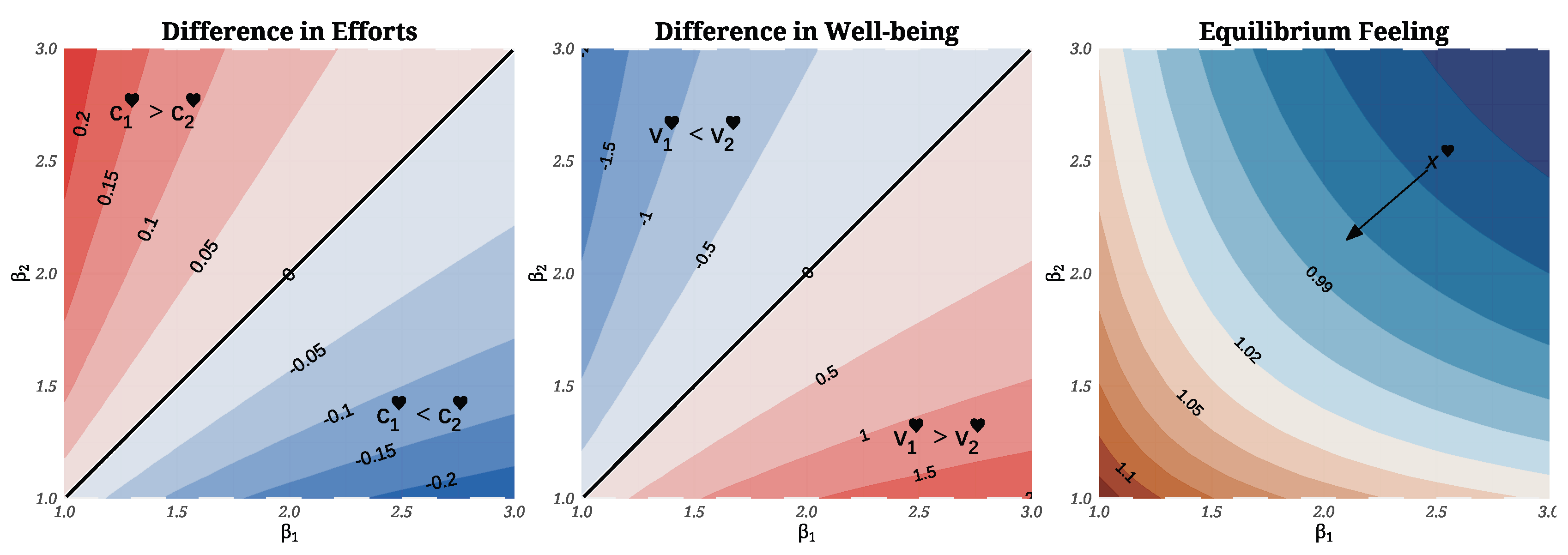

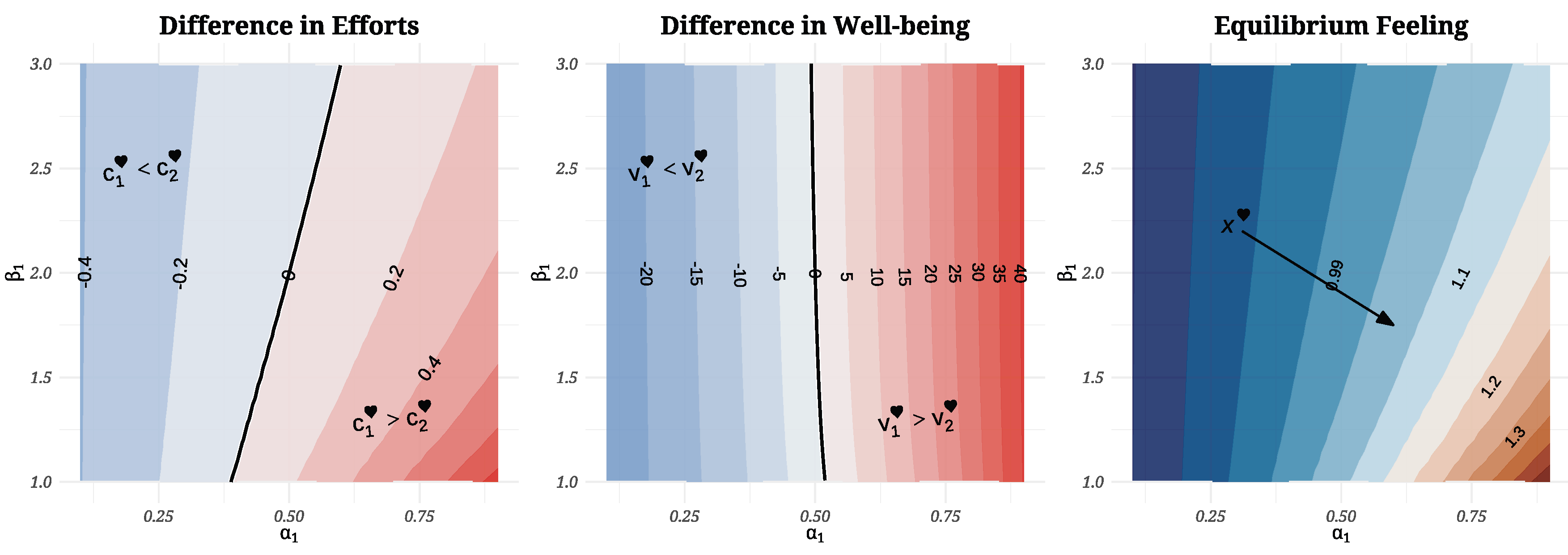

Emotional Parameter Sensitivity at Equilibrium: A Control-Theoretic Analysis.

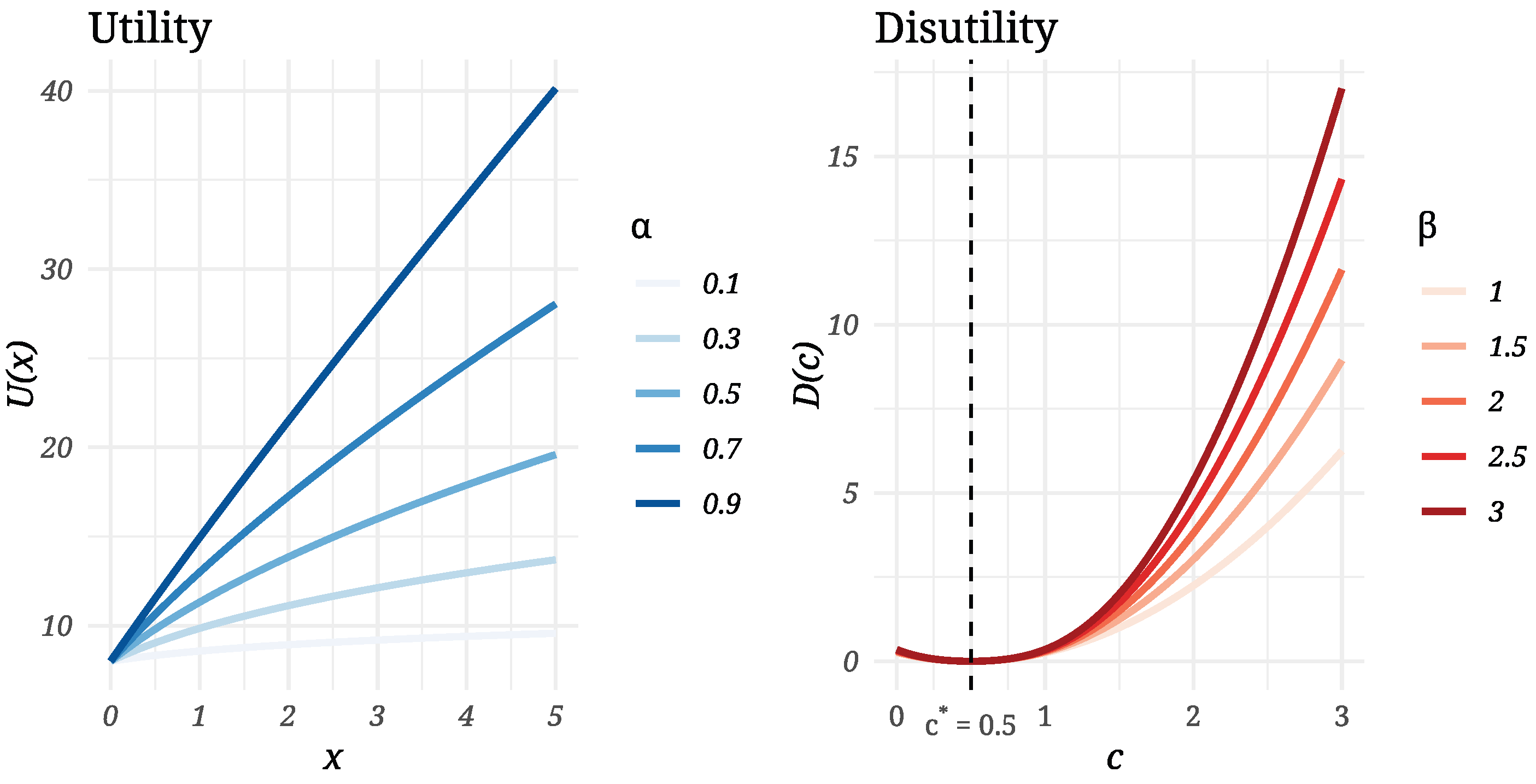

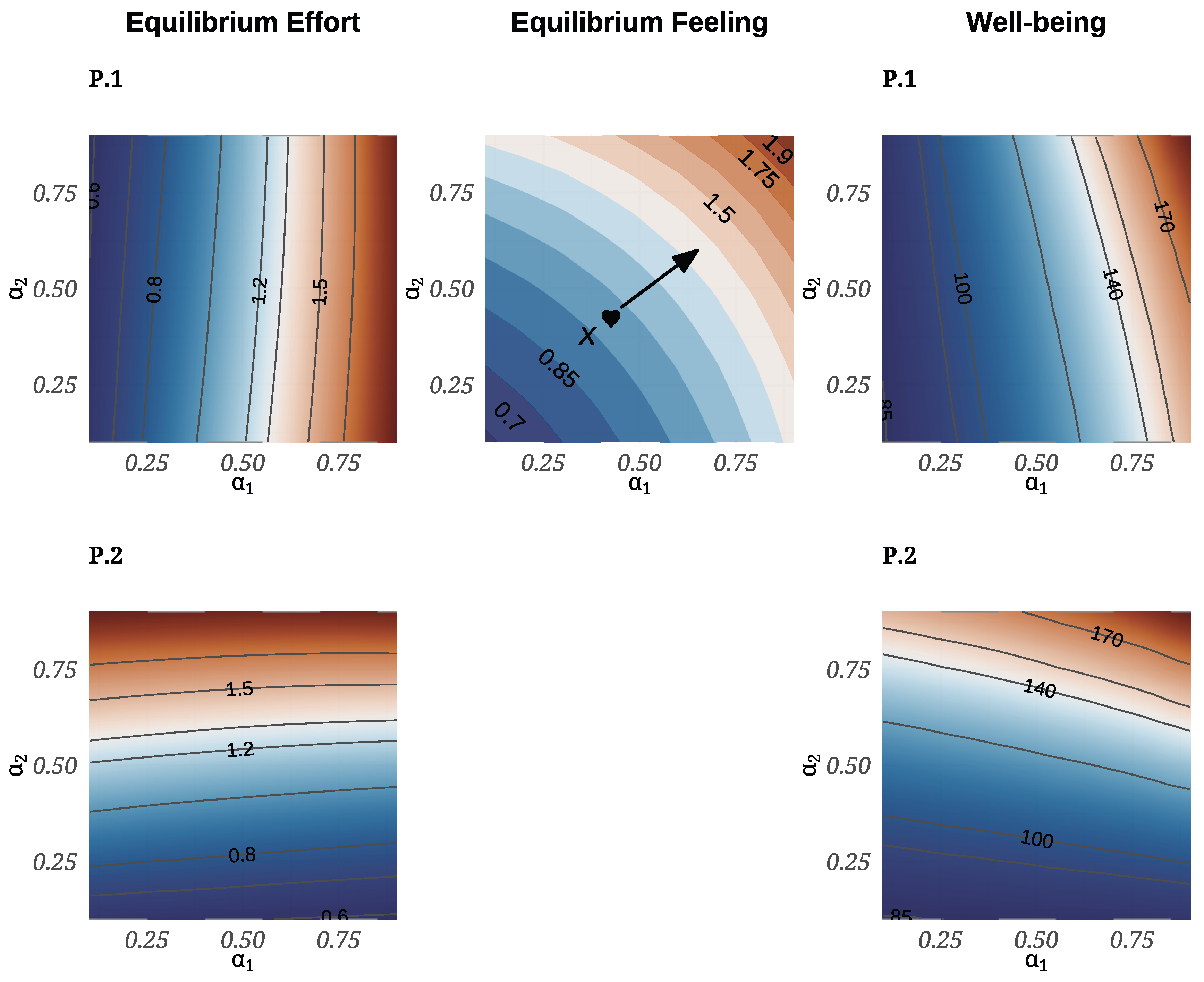

Emotional Contour Maps at Equilibrium: Computational Feedback Analysis

| Algorithm 1:Equilibrium Solution Computation |

|

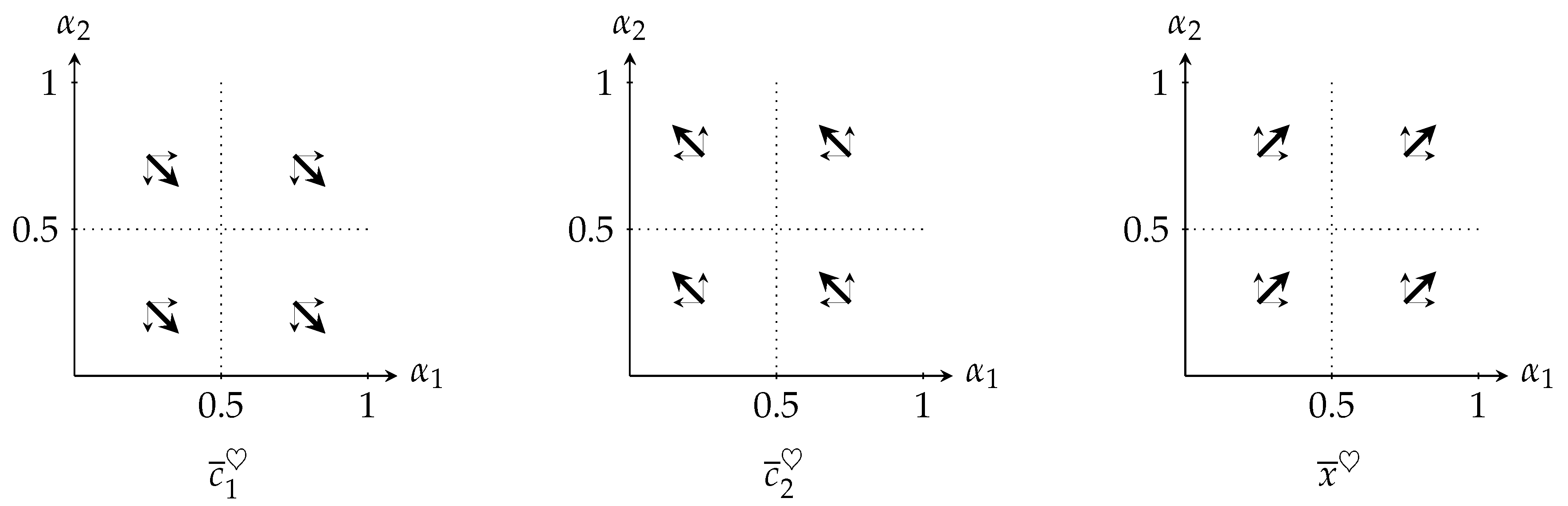

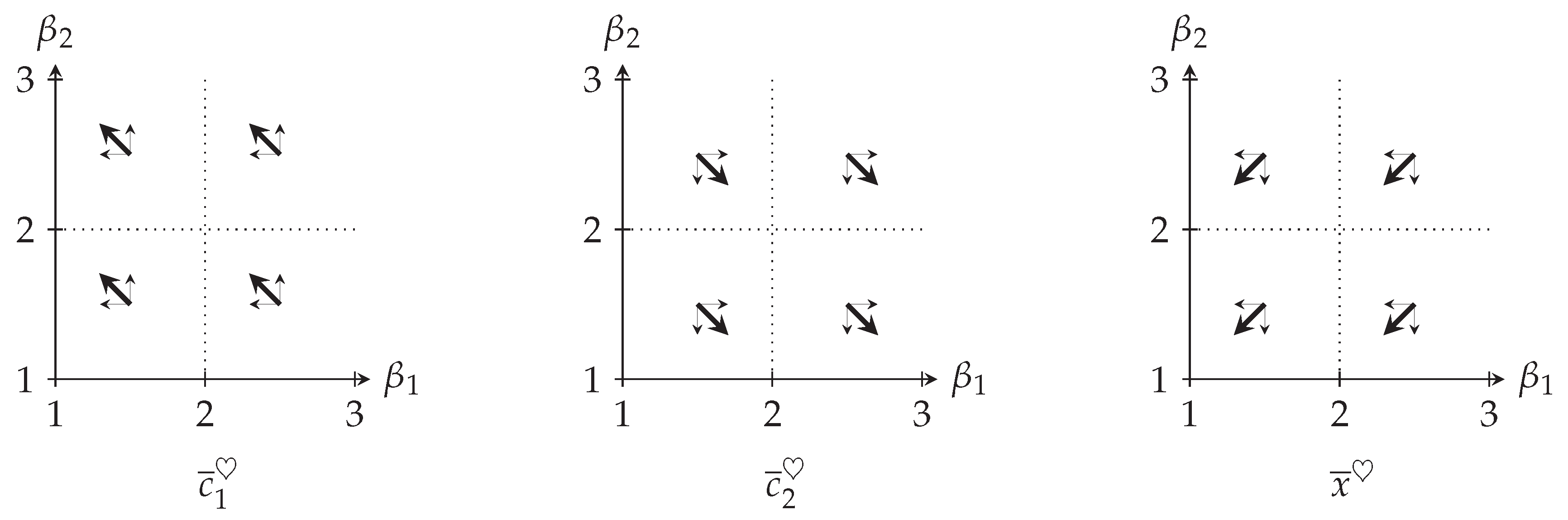

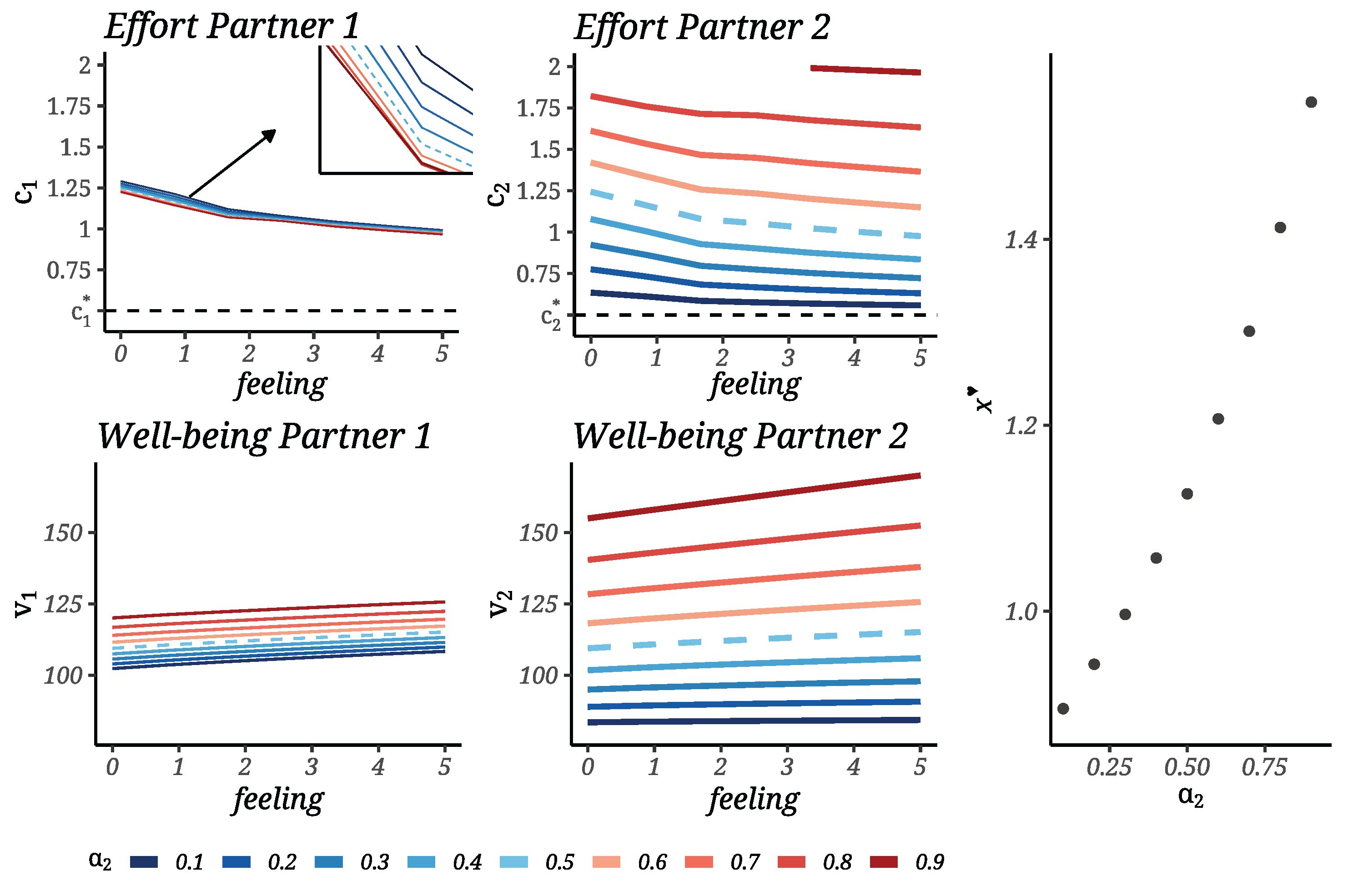

Emotional Reward Sensitivity

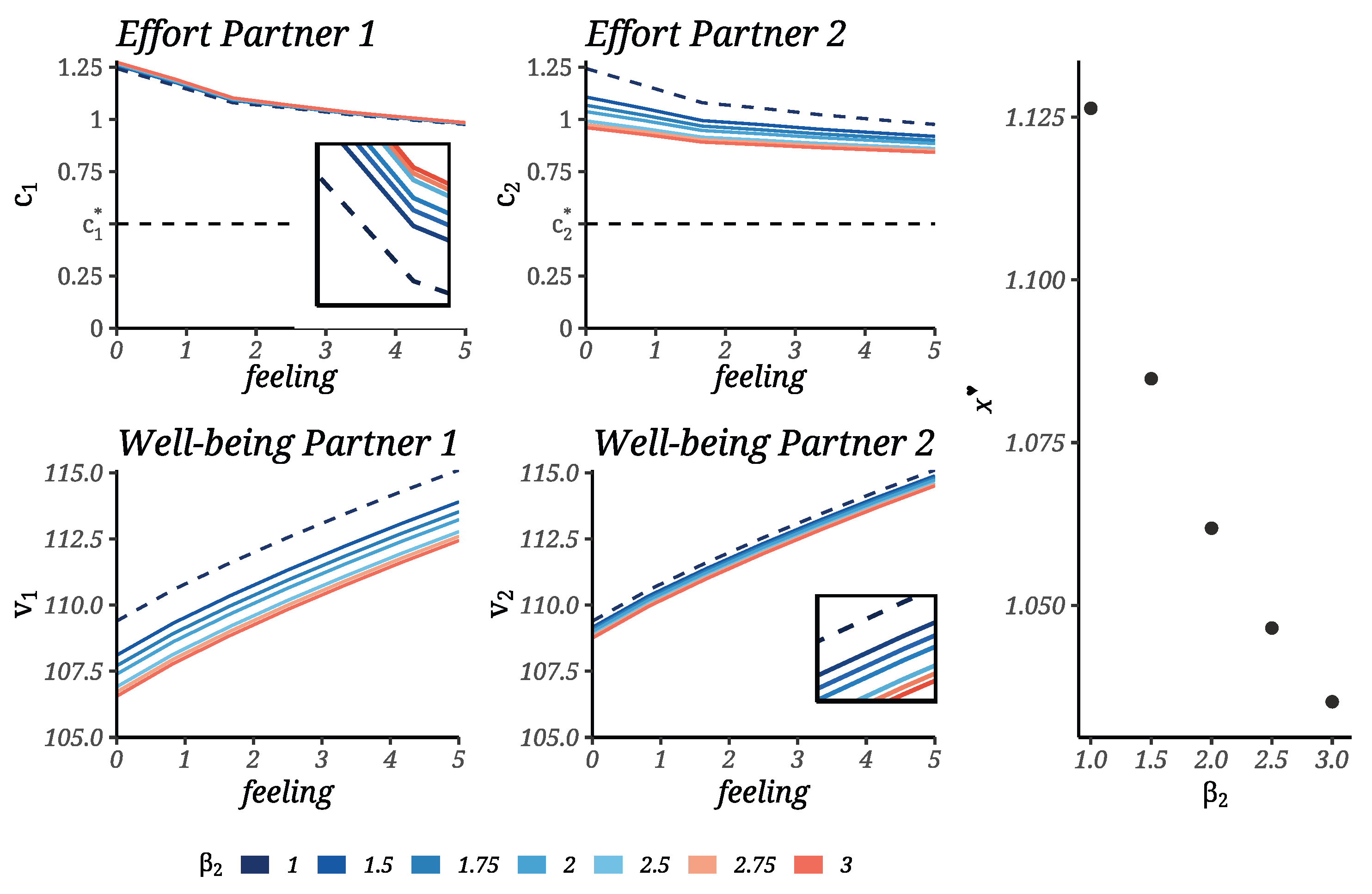

Emotional Cost Sensitivity

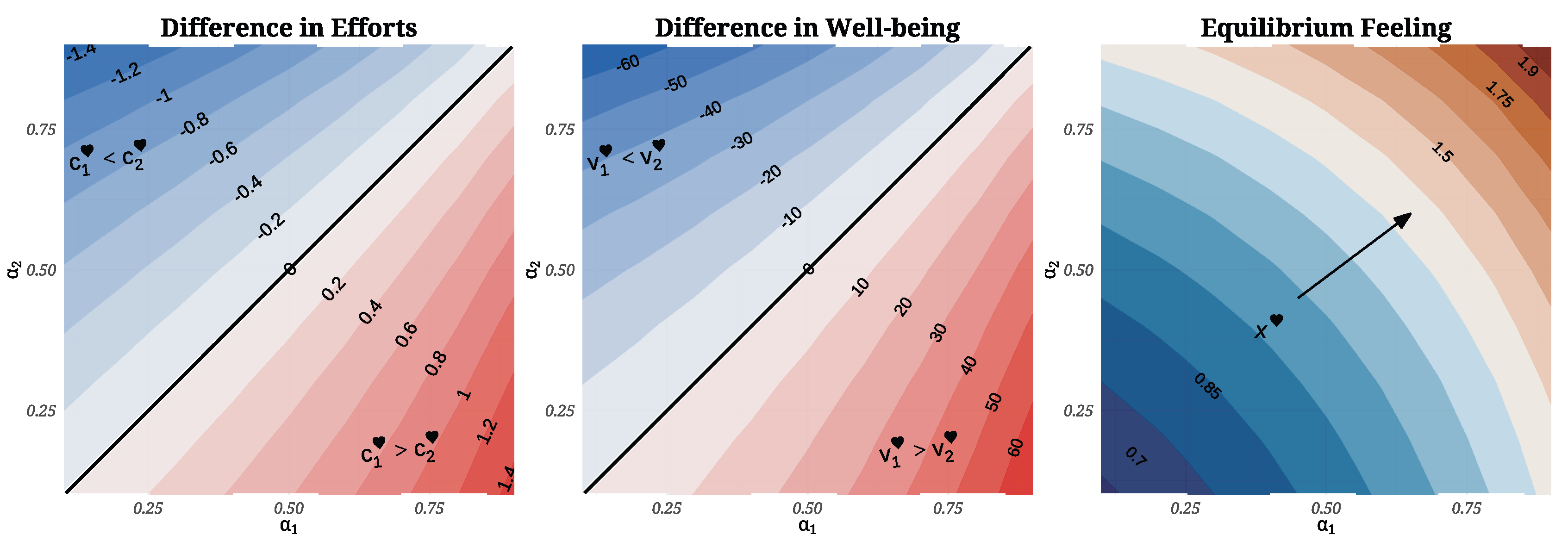

Dyadic disparity assessment

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coontz, S. Marriage, a history; New York, Viking, 2005.

- Finkel, E.J. Romantic relationships. The Handbook of Social Psychology (6th ed.) Gilbert, D.T., Fiske, S.T., Finkel, E.J., and Mendes, W.B. (Eds.).

- Weimann, J.; Knabe, A.; Schöb, R. Measuring Happiness: The Economics of Well-Being; The MIT Press., 2015.

- Schoen, R.; Canudas-Romo, V. Timing effects on divorce: 20th century experience in the United States. Journal of Marriage and Family 2006, 68, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottman, J.M.; Murray, J.D.; Swanson, C.C.; Tyson, R.; Swanson, K.R. The mathematics of marriage: Dynamic nonlinear models; MIT Press, 2005.

- Amato, P.R.; James, S.L. Changes in Spousal Relationships over the Marital Life Course. Alwin, Duane F.; Felmlee, Diane H.; and Kreager, Derek A. Editors (2018) Social Networks and the Life Course. Integrating the Development of Human Lives and Social Relational Networks.

- Strogatz, S.H. Love affairs and differential equations. Mathematics Magazine 1988, 61, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, S.; Della Rossa, F.; Dercole, F.; Gragnani, A.; Landi, P. Modeling love dynamics; Vol. 89, World Scientific, 2015.

- Rey, J.M. A mathematical model of sentimental dynamics accounting for marital dissolution. PloS one 2010, 5, e9881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pujo-Menjouet, L. Le jeu de l’amour sans le hasard. Mathématiques du couple; Éditions des Équaters, 2019.

- Herrera de la Cruz, J.; Rey, J.M. Controlling forever love. PloS one 2021, 16, e0260529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera de la Cruz, J.; Rey, J.M. A computational stochastic dynamic model to assess the rise of breakup in a romantic relationship. Mathematical Methods in the Applied Sciences 2025, 48, 7727–7744. [Google Scholar]

- Dockner, E.J.; Jorgensen, S.; Van Long, N.; Sorger, G. Differential games in economics and management science; Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Kreuzer, M.; Gollwitzer, M. Neuroticism and satisfaction in romantic relationships: A systematic investigation of intra- and interpersonal processes with a longitudinal approach. European Journal of Personality 2021, 36, 149–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D.A.; Kashy, D.A.; Cook, W.L. Dyadic Data Analysis; The Guilford Press., 20096.

- Herrera de la Cruz, J.; Ivorra, B.; Ramos, Á.M. An Algorithm for Solving a Class of Multiplayer Feedback-Nash Differential Games. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottman, J.M.; Silver, N. The Seven Principles for Making Marriage Work; Harmony Books, NY, 2015.

- Rey, J.M. Sentimental equilibria with optimal control. Mathematical and Computer Modelling 2013, 57, 1965–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, M.K. Dating, mating, and marriage; Routledge, 2018.

- Basar, T.; Olsder, G.J. Dynamic noncooperative game theory; Vol. 23, Siam, 1999.

- Bardi, M.; Capuzzo-Dolcetta, I. Optimal control and viscosity solutions of Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman equations; Springer Science & Business Media, 2008.

- Falcone, M.; Ferretti, R. Semi-Lagrangian approximation schemes for linear and Hamilton-Jacobi equations; Vol. 133, SIAM, 2013.

- Herrera de la Cruz, J. Numerical resolution of deterministic and stochastic differential games in feedback Nash equilibria; Complutense University of Madrid, Spain, 2020.

- Mai-Duy, N.; Tran-Cong, T. Approximation of function and its derivatives using radial basis function networks. Applied Mathematical Modelling 2003, 27, 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudon, T.; Lafitte, P. The lovebirds problem: why solve Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman equations matters in love affairs. Acta Applicandae Mathematicae 2015, 136, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, K.; Koch, M.; Spinath, F.M. Relationship satisfaction and The Big Five – Utilizing longitudinal data covering 9 years. Personality and Individual Differences 2025, 233, 112887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | The computations were run on an Apple M4 processor (10-core CPU: 4 performance + 6 efficiency cores; second-generation 3 nm process; 16-core Neural Engine, ). This work required 775 RaBVIt-G runs (parameterizations), each using 16 CPU seconds, with a tolerance . |

| i | r | x | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Values | 1 | 8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).