1. Introduction

A crash-tolerant system is designed to continue functioning despite a threshold number of crashes occurring and is crucial to maintaining high availability of systems [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Replication techniques have made it possible to create crash-tolerant distributed systems. Through replication, redundant service instances are created on multiple servers, and a given service request is executed on all servers so that even if some servers crash, the rest will ensure that the client receives the response. The set of replicated servers hosting service instances may also be referred to as a replicated group and simply as a group. Typically, a client can send its service to any one of the redundant servers in the group and the server that receives a client request, in turn, disseminates it within the group so all can execute. Thus, different servers can receive client requests in different order, but despite this, all servers must process client requests in the same order [

5,

6]. To accomplish this, a total order mechanism that employs logical clock is utilised to guarantee that replicated servers process client requests or simply messages in the same order [

7]. A logical lock is a mechanism used in distributed systems to assign timestamps to events, enabling processes to establish a consistent order of events occurring. Thus, a total order protocol is a procedure used within distributed systems to achieve agreement on the order in which messages are delivered to all process replicas in the group. This protocol ensures that all replicas receive and process the messages in the same order, irrespective of the order in which they were initially received by individual replicas. While total order protocols play a critical role in maintaining consistency and system reliability, achieving crash tolerance requires implementation of additional mechanisms. One such mechanism, as defined in our work, is the crashproofness policy. Specifically, this policy dictates that a message is deemed crashproof and safe for delivery once it has successfully reached at least f+1 operative processes, where f is the maximum tolerated failures in a group.

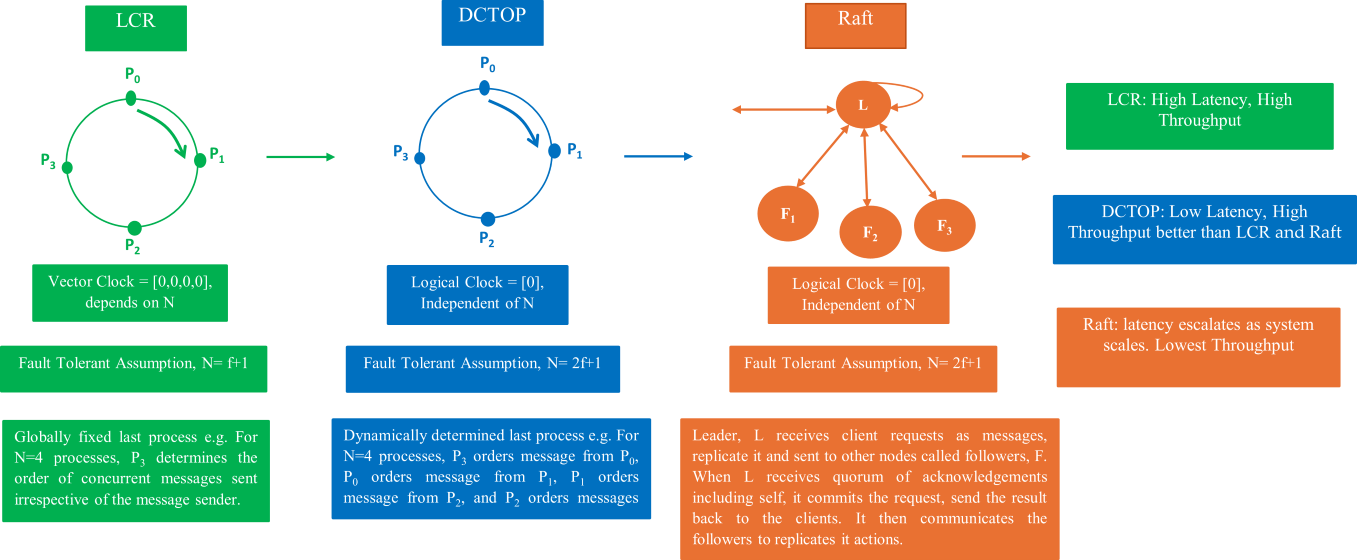

Total order protocols in the literature broadly fall into two categories: Leader-based and leaderless. In the leader-based protocol, every client request is routed through the leader which coordinates the request replication and responds to the clients with the results of execution. Examples include Apache Zookeeper [

10,

11], Chubby [

12,

14], Paxos [

15], View-stamp replication [

25] and Raft [

9,

16,

18]. Ring-based protocols are a class of leaderless protocols whose nodes are arranged in a logical ring. They ensure that all messages are delivered by all processes in the same order, regardless of how they were generated or sent by the sender. An example includes LCR [

19], FSR [

22], E-Paxos [

20], and S-Paxos [

21]. Our study focuses specifically on the ring-based leaderless protocols. Total order protocols are widely applicable to distributed systems, especially in applications requiring strong consistency and high throughput. For instance, they are utilised to coordinate transactions in massive in-memory database systems [

17,

23] where achieving minimal latencies despite heavy load is critical.

However, despite the progress made in ring-based protocols like LCR, certain design choices may lead to increased latency. The Logical Clock and Ring (LCR) protocol utilizes vector clocks where each process, denoted as , maintains its own clock as . A vector clock is a tool used to establish the order of events within a distributed system which can be likened to an array of integers, with each integer corresponding to a unique process in the ring. In the LCR protocol, processes are arranged in a logical ring, and the flow of messages is unidirectional as earlier described. However, LCRs’ design may lead to performance problems, particularly when multiple messages are sent concurrently within the cluster: firstly, it uses a vector timestamp for sequencing messages within replica buffers or queues [28], and secondly, it uses a fixed idea of "last" process to order concurrent messages. Thus, in the LCR protocol, the use of a vector timestamp takes up more space in a message, increasing its size.

Consequently, the globally fixed last process will struggle to rapidly sequence multiple concurrent messages, potentially extending the message-to-delivery average maximum latency. The size of a vector timestamp is directly proportional to the number of process replicas in a distributed cluster. Hence, if there are N processes within a cluster, each vector timestamp will consist of N counters or bits. As the number of processes increases, larger vector timestamps must be transmitted with each message, leading to higher information overhead. Additionally, maintaining these timestamps across all processes requires greater memory resources. These potential drawbacks can become significant in large-scale distributed systems, where both network bandwidth and storage efficiency are critical. Thirdly, in the LCR protocol, the assumption implies that , where f represents the maximum number of failures the system can tolerate. This configuration results in a relatively high f, which can delay the determination of a message as crashproof. While the assumption is practically valid, it is not necessary for f to be set at a high value. Reducing f can enhance performance by lowering the number of processes required to determine the crashproofness of a message.

Prompted by the above potential drawbacks in LCR, a new total order protocol was design with

,

, processes arranged in a unidirectional logical ring where

is the number of processes within the server clusters. Messages are assumed to pass among processes in a clockwise direction as shown in

Figure 1. If a message originates from

, it moves to

until it gets to

which is the last process for

. The study aims to achieve the following objectives: (i) Optimize message timestamping with Lamport logical clocks, which uses a single integer to represent message timestamps. This approach is independent of N, the number of processes in the communication cluster, unlike the vector timestamping used in LCR, which is dependent on N. In LCR, as N increases, the size of the vector timestamp grows, leading to information overhead. By contrast, Lamport's clock maintains a constant timestamp size, reducing complexity and improving efficiency (ii) Dynamically determines the "Last" Process for ordering concurrent messages. Instead of relying on a globally fixed last process for ordering concurrent messages, as in LCR, this study proposes a dynamically determined last process based on proximity to the sender in the opposite direction of message flow. This adaptive mechanism improves ordering flexibility and enhances system responsiveness under high workloads. (iii) Reduce message delivery latency. This study proposes reducing the value of f to (N – 1)/2 as a means to minimize overall message delivery latency and enhance system efficiency. This contrasts with the LCR approach, where f is set to N – 1. Specifically, when

a message must be received by every process in the cluster before it can be delivered. Under high workloads or in the presence of network delays, this requirement introduces significant delays, increasing message delivery latency and impacting system performance. The goal of this study was accomplished using three methods: First, we considered a set of restricted crash assumptions: each process crashes independently of others and at most

processes involved in a group communication can crash. A group is a collection of distributed processes in which a member process communicates with other members only by sending messages to the full membership of the group [

8]. Hence, the number of crashes that can occur in an N process cluster is bounded by

, where

denotes the largest integer

. The parameter

is known as the

degree of fault tolerance as described in Raft [

9]

. As a result, at least two processes are always operational and connected. Thus, an Eventually Perfect Failure Detector (♦P) was assumed in this study’s system model, operating under the assumption that N = 2f + 1 nodes are required to tolerate up to f crash failures. This approach enables the new protocol to manage temporary inaccuracies, such as false suspicions, by waiting for a quorum of at least f + 1 nodes before making decisions. This ensures that the system does not advance based on incorrect failure detections. Secondly, the last process of each sender is designated to determine the stability of messages. It then communicates this stability by sending an acknowledgement message to other processes. When the last process of the sender receives the message, it knows that all the logical clocks within the system have exceeded the timestamp of the message (stable property). Then all the received messages whose timestamp is less than the last process logical clock can then be totally ordered.

In addition, a new concept of "deliverability requirements" was introduced to guarantee the delivery of only crash-proof and stable messages in total order. A message is crashproof if the number of messages

, that is, a message must make at least

number of hops before it is termed crashproof. Thus, the delivery of a message is subject to meeting both deliverability and order requirements. As a result of enhancements made in this regard, a new leaderless ring-based total order protocol was designed, known as the Daisy Chain Total Order Protocol (DCTOP) [

13]. Thirdly, fairness is defined as the condition where every process

has an equal chance of having its sent messages eventually delivered by all processes within the cluster. Every process ensures messages from the predecessor are forwarded in the order they were received before sending their own message. Therefore, no process has priority over another during sending of messages.

1.1. Contributions

The contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows:

- (i)

-

Protocol-Level Innovations Within a Ring-Based Framework: This study introduces DCTOP, a novel improvement to the classical LCR protocol while retaining its ring-based design. It introduces:

Lamport Logical Clock used for message timestamping which achieves efficient concurrent message ordering, reducing latency and improving fairness.

Dynamic Last-Process Identification to replace LCR’s globally fixed last process assumption, accelerating message stabilization and accelerates delivery.

- (ii)

Relaxed Failure Assumption: DCTOP reduces the fault tolerance threshold from N = f + 1 to N = 2f + 1, enabling faster message delivery with fewer failures.

- (iii)

Foundation for Real-World Deployment: While simulations excluded failures and large-scale setups, ongoing work involves a cloud-based, fault-tolerant implementation to validate DCTOP under practical conditions.

This paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 presents the system model, while

Section 3 outlines the design objectives and rationale for DCTOP.

Section 4 details the fairness control primitives.

Section 5 provides performance comparisons of DCTOP, LCR and Raft in terms of latency and throughput under crash-free and high-workload conditions. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper.

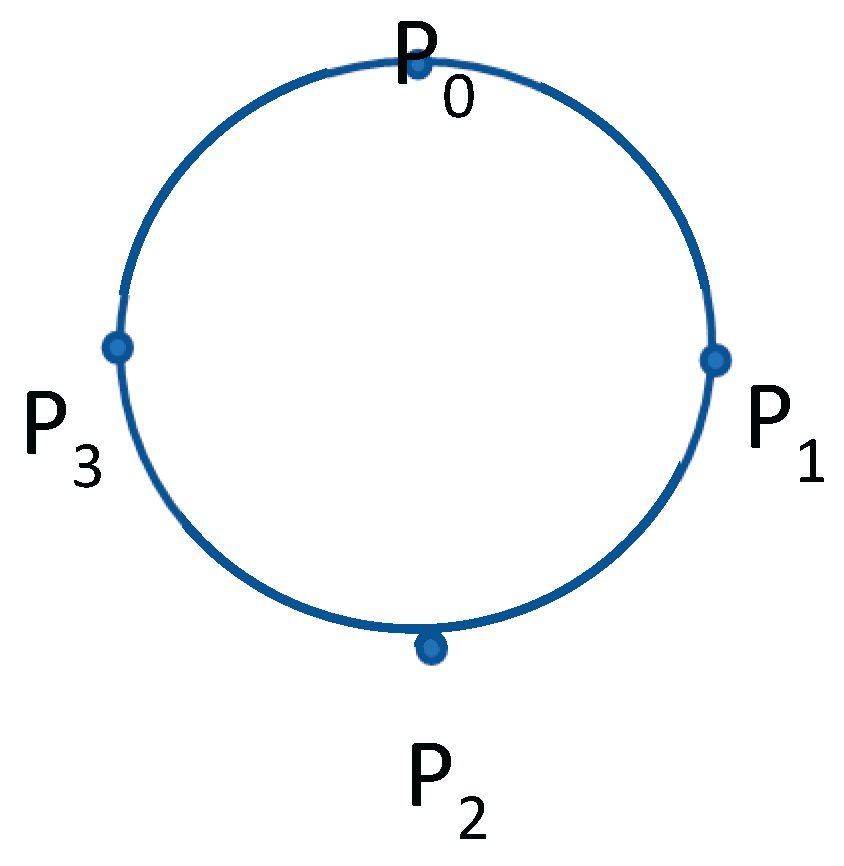

2. System Model

The ring-based protocols are modelled as a group of

processes represented by

which are linked together in a circular structure (see

Figure 1) with varying cluster sizes with an asynchronous-based communication framework, with no constraints on communication delays and exponentially distributed intervals between message transmissions. This model supports first in first out (FIFO), and thus messages sent are received in the order sent. The system model restricts a process,

, to only send messages to its clockwise neighbour and receive from its anticlockwise neighbour.

Thus, for each process , where and is the number of processes in the cluster, the clockwise neighbour is defined as the process immediately following , or if . Conversely, the anticlockwise neighbour of is defined as the process immediately preceding , or if . Therefore, messages are transmitted exclusively in the clockwise direction, with receiving from and transmitting to in a daisy chain framework. We also defined the Stability clock of any process as the largest timestamp, , known to any process as stable. When a message becomes stable, is updated as follows: = max{ , }. Additionally, we introduce the definition of which is defined as the number of hops between any two processes from to in the clockwise direction: (i) , . (ii) , and (iii) .

3. Daisy Chain Total Order Protocol- DCTOP

The DCTOP system employs a group of interconnected process replicas, with a group size of , where is an odd integer, and at most 9, to provide replicated services. The main goals of the system design are threefold:

- (a)

First, to improve the latency of LCR by utilizing Lamport logical clocks for sequencing concurrent messages.

- (b)

Second, to employ a novel concept of the dynamically determined “last” process for ordering concurrent messages, while ensuring optimal achievable throughput.

- (c)

Third, the relaxation of the crash failure assumption in LCR.

3.1. Data Structures

The data structures associated with each process , message m, and the µ message are discussed in this section as used in DCTOP system design and simulation experiment:

Each process has the following data structures:

Logical clock : This is an integer object initialized to zero. It is used to timestamp messages.

Stability clock : This is an integer object that holds the largest timestamp, , known to as stable. Initially, is zero.

Message Buffer (): This field holds the sent or received messages by .

Delivery Queue (: Messages waiting to be delivered are queued in this queue object.

Garbage Collection Queue (: After a message is delivered, the message is transferred to to be garbage collected.

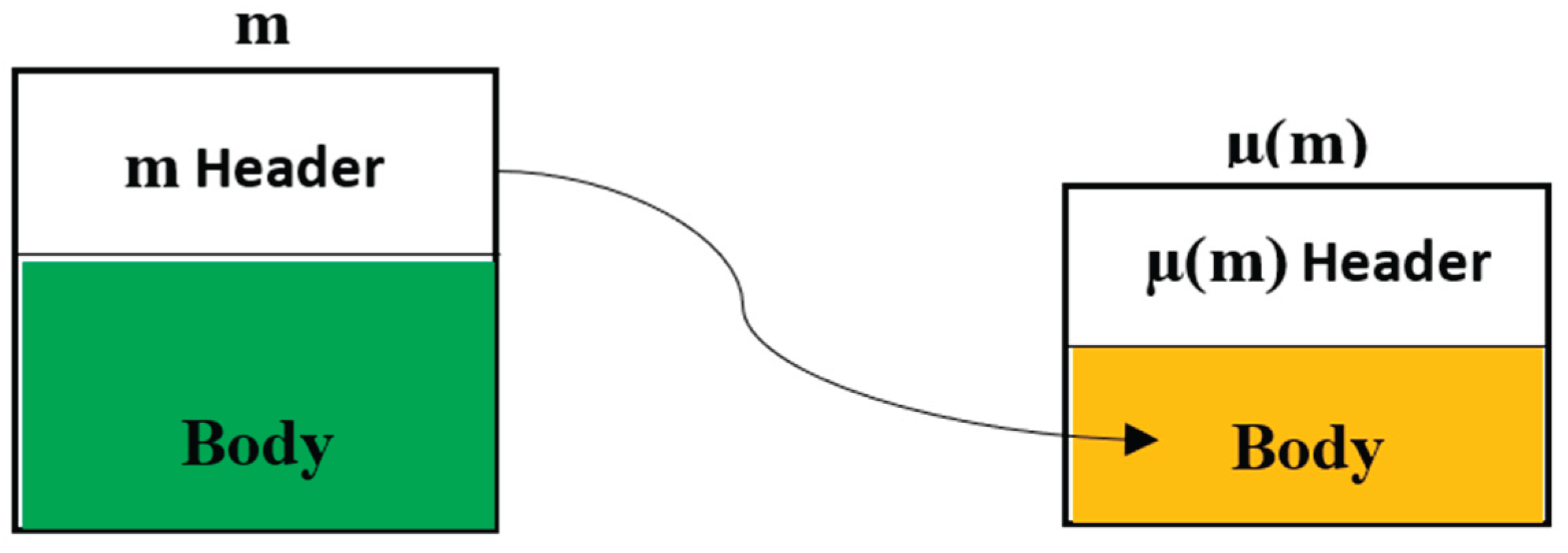

M is used to denote all types of messages used by the protocol. Usually there are two types of M: data message denoted by

m, and an announcement or ack message that is bound to a specific data message. The latter is denoted as µ(m) when it is bound to

m. µ(m) is used to announce that

m has been received by all processes in

. The relationship between

m and its counterpart µ(m) is shown in

Figure 2.

A message,

m, consists of a header and a body, with the body containing the data application information. Every

m has a corresponding µ, denoted as µ

, which contains the information from

m's header. This is why we refer to µ

instead of just µ. µ

has

m header information as its main information and does not contain its own data; therefore, the body of µ

is essentially

m's header (see

Figure 2).

A message M has at least the following data structures:

Message origin field shows the id of the process in that initiated the message multicast.

Message timestampfield holds the timestamp given to M by M_origin.

Message destination field holds the destination of M which is the CN of the process that sends/forwards M.

Message flag (M_flag) it is a Boolean field which can be true or false and is initiated to be false when M is formed.

3.2. DCTOP Principles

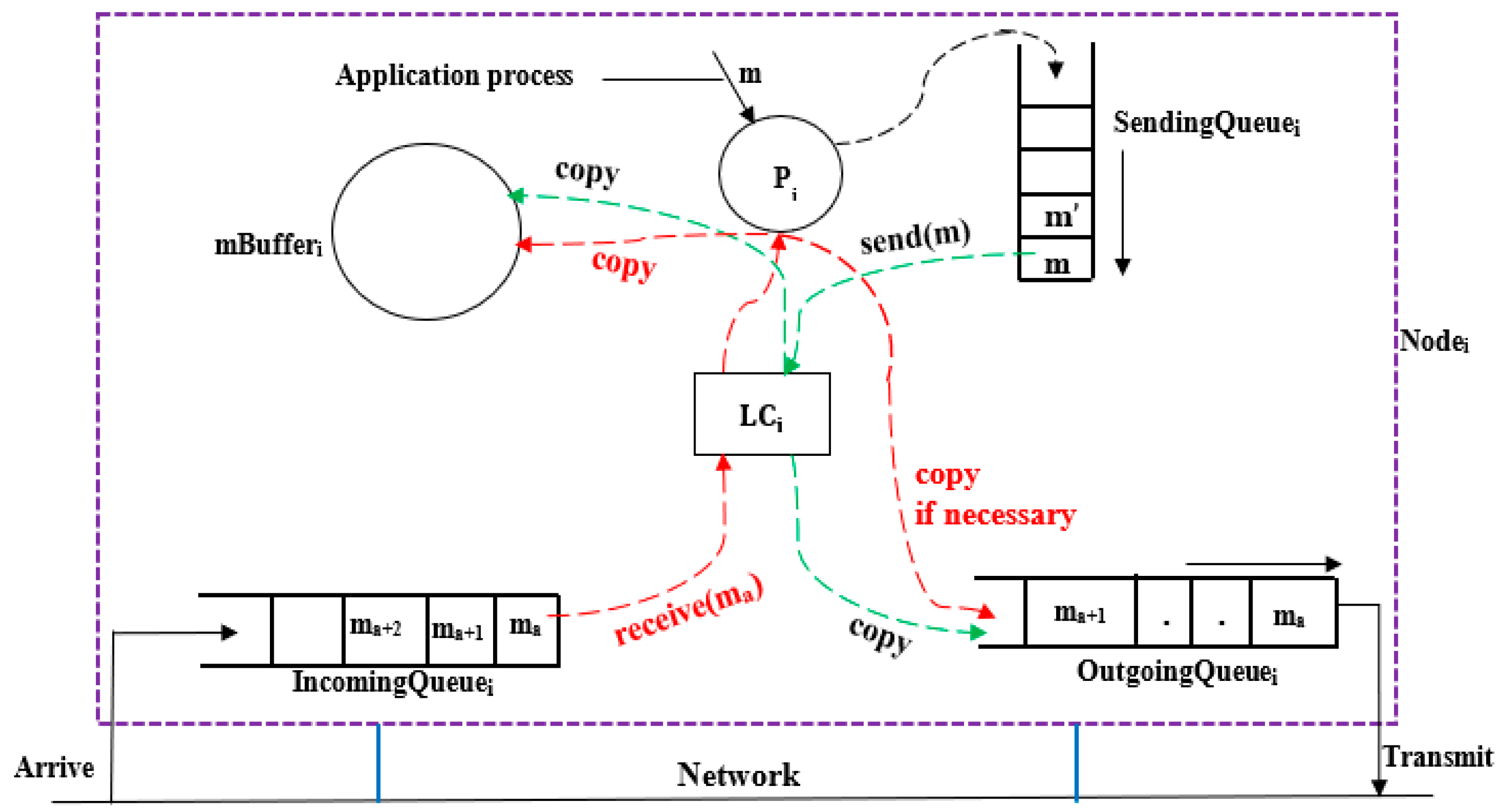

The protocol has three design aspects:(i) message sending, receiving, and forwarding, (ii) timestamp stability, and (iii) crashproofing of messages, which are described in detail one by one in this subsection.

- (1)

Message Sending, Receiving and Forwarding: The Lamport logical clock is used to timestamp a message m within the ring network before m is sent. Therefore, denotes the timestamp for message .

The system as shown in

Figure 3 uses two main threads to handle message transmission and reception in a distributed ring network. The send(m) thread operates by dequeuing a message m from the non-empty SendingQueue

i when allowed by the transmission control policy (see

Section 4). It timestamps the message with the current value of the LC

i as

, increments LC

i by one afterwards, and then places the timestamped message into the OutgoingQueue

i for transmission. A copy of the message is also stored in mBuffer

i for local record.

On the receiving side, the receive(m) thread dequeues a message m from the IncomingQueuei when permitted by the transmission control policy, updates the as , and delivers the message to process Pi for further handling. Typically, m is entered in and may be forwarded if necessary to by entering a copy of m with destination set to into the . If necessary, meaning the message has not yet completed a full cycle around the ring, it may be forwarded to the CNi by placing a copy of it in the OutgoingQueuei with its destination set to . However, once the message has completed a full cycle within the ring network, it is no longer forwarded, and the forwarding process stops.

If two messages are received consecutively, they are sent in the same order but not necessarily immediately after each other, depending on the transmission control policy. As shown in

Figure 3, messages to be received arrive at the

from the network, and a copy of the received message arrives at the

while a copy of the forwarded messages appears in the

according to the order they were received.

- (2)

-

Timestamp Stability: A message timestamp TS, , is said to be stable in a given process if and only if the process is guaranteed not to receive any , any longer.

Observations:

- 1)

A timestamp is also stable in when TS becomes stable in .

- 2)

The term “stable” is used to refer to the fact that once TS becomes stable in

, it remains stable for ever. This usage corresponds to that of “stable” property used by Chandy and Lamport [

24]. Therefore, the earliest instance when a given TS becomes stable in

will be the interest in the later discussions.

- 3)

When TS becomes stable in , the process can potentially total order (TO) deliver all received but undelivered , because stability of TS eliminates the possibility of ever receiving any , , in the future.

- (3)

Crashproofing of Messages: A message m is crashproof if m is in possession of at least () processes. Therefore, a message m is crashproof in when knows that m has been received by at least () processes. The rationale for crashproofing is that when we have at least processes that have received a given message m even if of them crash there will be at least one process that can be relied on in sending m to others and this emphasizes the importance of crashproofness in our system.

3.3. DCTOP Algorithm Main Points

The DCTOP algorithm's main points are outlined as follows:

When forms and sends m, it sets m_flag = false, before it deposits m in its .

-

When receives m and = m_origin

It checks if ≥ f. If this is true then m is crashproofed, it does not deliver m immediately. Moreover, it sets m_flag = true and deposits m in its . if m is not crashproofed, then m_flag remains false.

It then checks if ≠ . if this is true, it sets m destination, m_destn = and deposits m in its ,

Otherwise, m is stable then it updates as = max { , m_ts}, and transfer all m, m_ts ≤ to . Then, it forms µ(m), sets the two header fields, µ(m)_origin=, µ(m)_destn= and deposit µ(m) in

-

When receives µ(m), it knows that every process has received m.

If m in µ(m) does not indicate a higher stabilisation in , that is, m_ts ≤ and ≥ f then ignores µ(m), otherwise, if < f, sets m_flag= true, µ(m)_destn = and deposit µ(m) in

However, if m in µ(m) indicates a higher stabilisation in , that is, m_ts > , updates as = max { , m_ts}, and transfer all m, m_ts ≤ to .

If = , ignores µ(m) otherwise, it sets µ(m)_destn = and deposit µ(m) in

Whenever is non-empty, deques m from the head of and delivers to application process. then enters a copy of into to represent a successful TO delivery. This action is repeated until becomes empty.

It is important to note that the DCTOP maintains total order. Thus, if forms and sends and then : (i) Every process receives and then (ii) µ() will be formed and sent before µ() and (iii) Any process that receives both µ() and µ() will receive µ() and then µ().

3.4. DCTOP Delivery Requirements

Any message m can be delivered to the high-level application process by if satisfies the following two requirements:

- (i)

m_ts must be stable in

- (ii)

m must be crashproof in , and

- (iii)

Any two stable and crashproofed , and are delivered in total order: is delivered before or and

During the delivery of m, if then the messages are ordered according to the origin of the messages, usually a message from are ordered before a message from where .

In summary, the pseudocode representations for total order message delivery, message communication, and membership changes are presented in

Figure 4,

Figure 5, and

Figure 6 respectively.

3.5. Group Membership Changes

The DCTOP protocol is built on top of a group communication system [

26,

27]. Membership of the group of processes executing DCTOP can change due to (i) a crashed member being removed from the ring and/or (ii) a former member recovering and being included in the ring. Let G represent the group of DCTOP processes executing the protocol at any given time. G is initially

and G

is always true. The

membership change procedure is detail in

Figure 6. Note that the local membership is assumed to send an interrupt to the local DCTOP process, say,

when a membership change is imminent. On receiving the interrupt

completes processing of any message it has already started processing and then suspends all DCTOP activities and waits for new G

' to be formed: sending of

m or µ(m) (by enqueueing into

), receiving of

m or µ(m) (from

) and delivering of m (from

) are all suspended. The group membership change work as follows: Each process P

i in the set of Survivors(G) (i.e., survivors of the current group G) exchanges information about the last message they TO-delivered. Once this exchange is complete, additional useful information is derived among all Survivors, which helps identify the Lead Survivor.

Subsequently, each Survivor sends all messages from its respective SendingQueue to the other Survivors. If Pi has any missing messages, they are sent to another Survivor, Ps where Ps represents any Survivor process other than Pi. After sending, Pi transmits a Finishedi message to all Ps processes, signalling that it has completed its sending. Upon receiving messages, Pi stores all non-duplicate messages in its buffer, mBufferi. The receipt of Finisheds messages from all Ps processes confirms that Pi has received all expected messages, with duplicates discarded. Pi then waits to receive Readys from every other Ps, ensuring that every Survivor Ps has received the messages sent by Pi . At this point, all messages in mBufferi are stable and can be totally ordered. If there are Joiners (defined as incoming members of G' that were not part of the previous group (Gprev) but joined G' after recovering from an earlier crash), the Lead Survivor sends its checkpoint state and TO_Queue to each Pj in the set of NewComer(G'), allowing them to catch up with the Survivors(G). Following this, all Survivors(G) resume TO delivery in Gprev. Pi then sends a completedi message to every process in G, indicating that it has finished TO-delivering in Gprev. Each Survivor waits to receive a completedk message from every other Pk in G before resuming DCTOP operations in the new G'. The Joiners, after replicating the Lead Survivor's checkpoint state, also perform TO delivery of messages in Gprev and then resume operations in the new G' of DCTOP. Hence, at the conclusion of the membership change procedure, all buffers and queues are emptied, ensuring that all messages from Gprev have been fully processed.

3.6. Proof of Correctness

Lemma 1 (VALIDITY).

If any correct process utoMulticasts a message m, then it eventually utoDelivers m.

Proof: Let

be a correct process and let m

i be a message sent by

. This message is added to mBuffer

i (Line 15 of

Figure 5) . There are two cases to consider:

Case 1: Presence of membership change

If there is a membership change,

will be in Survivor(G) since

is a correct process. Consequently, the membership changes steps ensure that

will deliver all messages stored in its mBuffer

i , TO_Queue

i or GCQ

i including

mi (Line 32 to 44 of

Figure 5). Thus,

utoDelivers message

mi that it sent.

Case 2: No membership changes

When there is no membership change, all the processes within the DCTOP system including the m

i_origin will eventually deliver m

i after setting m

i stable (Line 28 of

Figure 5)

. This happens because when

timestamp, sets m

i_flag=false and sends m

i to its CN

i, it deposits a copy of m

i to its mBuffer

i and sets LC

i > m

i_ts afterward. The message is forwarded along the ring network until the ACN

i receives m

i. Any process that receives m

i deposits a copy of it into their mBuffer and sets LC > m

i_ts. It also checks if Hops

ij ≥ f, then m

i is crashproof and it sets m

i_flag=true. The ACN

i sets m

i stable (Line 28 of

Figure 5) and crashproof (Line 20 of

Figure 5) at ACN

i, transfers m

i to DQ and then it attempts utoDeliver m

i (Lines 1 to 8 of

Figure 4) if m

i is at the head of DQ. ACN

i generates, timestamp µ(m

i) using its LC and then sends it to its own CN. Similarly, µ(m

i) is forwarded along the ring (Line 31 of

Figure 5) until the ACN of µ(m

i)_origin receives µ(m

i). When any process receives µ(m

i) and Hops

ij <f, it knows that m

i is crash proof and stable but if Hops

ij ≥f, then m

i is only stable because m

i is already known to be crashproof since at least f+1 processes had already received m

i. Any process that receives µ(m

i) transfers m

i from mBuffer to DQ and then attempts to utoDeliver m

i if m

i is at the head of DQ.

Suppose Pk sends mk before receiving mi, . Consequently, ACNi will receive mk before it receives mi and thus before sending µ(mi) for mi. As each process forwards messages in the order in which it receives them, we know that will necessarily receive mk before receiving µ(mi) for message mi.

- (a)

If mi_ts = mk_ts, then orders mk before mi in mBufferi since (This study assumed that when messages have equal timestamp, message from a higher origin is ordered before message from a lower origin.). When receives µ(mi) for message mi it transfers both messages to DQ and can utoDeliver both messages, mk before mi, because TS is already known to be stable because of TS equality.

- (b)

If mi_ts < mk_ts then orders mi before mk in mBufferi. When receives µ(mi) for message mi it transfers both messages to DQ and can utoDeliver mi only since it is stable and is at the head of DQ. will eventually utoDeliver mk when it receives µ(mk) for mk since it is now at the head of DQ after mi delivery.

- (c)

Option (a) or (b) is applicable in any other processes within the DCTOP system since there is no membership changes. Thus, if any correct process sends a message m, then it eventually delivers m.

Note that if f+1 processes receive a message m, then m is crash proof and during concurrent multicast, TS can become stable quickly making m to be delivered even before the ACN of the m_origin receives m.

Lemma 2 (INTEGRITY). For any message m, any process Pk utoDelivers m at most once, and only if m was previously utoMulticast by some process .

Proof. The crash failure assumption in this study ensures that no false message is ever utoDelivered by a process. Thus, only messages that have been utoMulticast are utoDelivered. Moreover, each process maintains an

LC, which is updated to ensure that every message is delivered only once. The sending rule ensures that messages are sent with an increasing timestamp by any process

, and the receive rule ensures that the LC of the receiving process is updated after receiving a message. This means that no process can send any two messages with equal timestamps. Hence, if there is no membership change, Lines 16 and 19 of

Figure 5 guarantee that no message is processed twice by process P

k. In the case of a membership change, Line 3a(ii) of

Figure 6 ensures that process P

k does not deliver messages twice. Additionally, Lines 7(i-iv) of

Figure 6 ensure that P

k’s variables such as logical and stability clock are set to zero, and the buffer and queues are emptied after a membership change. This is done because processes had already delivered all the messages of the old group discarding message duplicates (Line 3a(ii) of

Figure 6) to the application process and no messages in the old group will be delivered in the new group. Thus, after a membership change, the new group is started as a new DCTOP operation. The new group might contain messages with the same timestamp as those in the old group, but these messages are distinct from those in the old group. Since timestamps are primarily used to maintain message order and delivery, they do not hold significant meaning for the application process itself. This strict condition ensures that messages already delivered during the membership change procedure are not delivered again in the future.

Lemma 3 (UNIFORM AGREEMENT).

If any process utoDelivers any message m in the current G, then every correct process in the current G eventually utoDelivers m.

Proof. Let mi be a message sent by process and let be a process that delivered mi in the current G.

Case 1:

delivered mi in the presence of a membership change.

delivered

mi during a membership change. This means that

had

mi in its mBuffer

i, TO_Queue

i, GCQ

i before executing line 6a(ii) of

Figure 6. Since all correct processes exchange their mBuffer

i, TO_Queue

i, GCQ

i during the membership change procedure, we are sure that all correct processes that did not deliver

mi before the membership change will have it in their mBuffer

i, TO_Queue

i or GCQ

i before executing line 1 to 9 of

Figure 6. Consequently, all correct processes in the new G' will deliver

mi.

Case 2:

delivered mi in the absence of a membership change.

The protocol ensures that

mi does a complete cycle around the ring before being delivered by

: indeed,

can only deliver

mi after it knows that

mi is crashproof and stable, which either happens when it is the ACN

i in the ring or when it receives µ(m

i) for message

mi. Remember that processes transfer messages from their mBuffer to DQ when the messages become stable. Consequently, all processes stored

mi in their DQ before

delivered it. If a membership change occurs after

delivered

mi and before all other correct processes delivered it, the protocol ensures that all Survivor(G) that did not yet deliver

mi will do it (Line 6a(ii) of

Figure 6). If there is no membership change after

delivered

mi and before all other processes delivered it, the protocol ensures that µ(m

i) for

mi will be forwarded around the ring, which will cause all processes to set

mi to crashproof and stable. Remember, when any process receives µ(m

i) and Hops

ij < f, it knows that m

i is crash proof and stable but if Hops

ij ≥ f, then m

i is only stable because m

i is already known to be crashproof since at least f+1 processes had already received m

i. Each correct process will thus be able to deliver

mi as soon as

mi is at the head of DQ (Line 3 of

Figure 4). The protocol ensures that

mi will become first eventually. The reasons are the following: (1) the number of messages that are before

mi in DQ of every process P

kis strictly decreasing, and (2) all messages that are before

mi in DQ of a correct process P

kwill become crashproof and stable eventually. The first reason is a consequence of the fact that once a process P

ksets message

mi to crashproof and stable, it can no longer receive any message

m such that

m≺

mi. Indeed, a process P

c can only produce a message

mc ≺

mi before receiving

mi. As each process forwards messages in the order in which it received them, we are sure that the process that will produce an µ(m

i) for m

i will have first received

mc. Consequently, every process setting

mi to crashproof and stable will have first received

mc. The second reason is a consequence of the fact that for every message m that is utoMulticast in the system, the protocol ensures that m and µ(m) will be forwarded around the ring (Lines 25 and 31 of

Figure 5), implying that all correct processes will mark the message as crashproof and stable. Consequently, all correct processes will eventually deliver

mi.

Lemma 4 (TOTAL ORDER).

For any two messages m and if any process utoDelivers m without having delivered , then no process utoDelivers before m.

Suppose that deduces stability of TS, , for the first time by (i) above at, say, time t, that is, by receiving m, and , at time t. cannot have any , in its at time t nor will ever have at any time after t.

Proof (By Contradiction) Assume, contrary to Lemma, that

is to receive

,

, after t as shown

Figure 7a.

Let

. So, imagine that

is the same as

,

, as shown in

Figure 7b. Given that

,

must be true when

. So,

must have sent

first and then

.

Note that

- (a)

The link between any pair of consecutive processes in the ring maintains FIFO, and

- (b)

Processes forward messages in the order they received those messages.

Therefore, it is not possible for to receive after it received m, that is, after t. So case 1 cannot exist.

Imagine that

is from

and

is from

,

, as shown in

Figure 6b. Since

is the last process to receive

m in the system,

must have received

m before t; since

,

could not have sent

after receiving

m. So, the only possibility for

to hold is:

must form and send

before it is received and forwarded

m.

For the cases of (a) and (b) in case 1, must receive before m. Therefore, the assumption made contrary to Lemma 1 cannot be true. Thus, Lemma 1 is proved.

4. Fairness Control Environment

In this section, the DCTOP fairness mechanism was discussed: for a given round k, any process either sends its own message to the or forwards messages from its to the . A round is defined as follows: for any round k, every process sends at most one message, m, to its and also receives at most one message, m, from its in the same round. Every process has an which contains the list of all messages received from the which was sent by other processes, and a . The consist of the messages generated by the process waiting to be transmitted to other processes. When the is empty, the process forwards every message in its but whenever the is not empty, a rule is required to coordinate the sending and forwarding of messages to achieve fairness.

Suppose that process has one or more message(s) to send stored in its , it follows these rules before sending each message in its to the : process sends exactly one message in to the if

- (1)

the is empty, or

- (2)

-

the is not empty and either

- (2.1)

had forwarded exactly one message originating from every other process or

- (2.2)

the message at the head of the originates from a process whose message the process had already forwarded.

To implement these rules and verify rules 2.1 and 2.2, a data structure called forwardlist was introduced. The at any time consists of the list of the origins of the messages that process forwarded ever since it last sent its own message. Obviously by definition, as soon as the process sends a message, the is empty. Therefore, if forwards a message that originates from the process ,, which was initially in its , then process will contain the process in its forward list, and whenever it sends a message the process will be deleted from the .

5. Experiments and Performance Comparison

This section presents a performance comparison of the DCTOP protocol against the LCR [

19] protocol and Raft [

9,

18] a widely implemented, leader-based ordering protocol by evaluating latency and throughput across varying numbers of messages transmitted within the cluster environment. Java (OpenJDK-17, Java version 17.02) framework was used to run a discrete event simulation for the protocols with at most 9 processes,

.

Every simulation method made use of a common PC with a 3.00GHz 11th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-1185G7 Processor and 16GB of RAM. A request is received from the client by each process, which then sends the request as a message to its neighbour on the ring-based network. When a neighbour receives a message, it passes it on to another neighbour until all processes have done so. When the ACN of the message origin receives the message then it knows that it is stable and makes an attempt to deliver it in total order, a process known as TO delivery. This process then notifies all other processes which, up until this point, had no idea of the message's status by using an acknowledgement message known as µ-message to inform them of the message's stability. Other processes that get this acknowledgement are aware that the message is stable and make an effort to deliver it in total sequence. For a Raft cluster, when a client sends a request to the leader, the leader adds the command to its local log, then sends a message to follower processes to replicate the entry. Once a majority (including the leader) confirms replication, the entry is committed. The leader then applies the command to its state machine for execution, notifies followers to do the same, and responds to the client with the output of execution.

The time between successive message transmissions is modelled as an exponential distribution with a mean of 30 milliseconds, reflecting the memoryless property of this distribution, which is well-suited for representing independent transmission events. The delay between the end of one message transmission and the start of the next is also assumed to follow an exponential distribution, with a mean of 3 milliseconds, to realistically capture the stochastic nature of network delays. For the simulation, process replicas are assumed to have 100% uptime, as crash failure scenarios were not considered. Additionally, no message loss is assumed, meaning every message sent between processes is successfully delivered without failure.

The simulations were conducted with varying numbers of process replicas, such as 4, 5, 7, and 9 processes. The arrival rate of messages follows a Poisson distribution with an average of 40 messages per second, modelling the randomness and variability commonly observed in real-world systems. The simulation duration ranges from 40,000 to 1,000,000 seconds. This extended period is chosen to ensure the system reaches a steady state and to collect sufficient data for a 95% confidence interval analysis. The long duration also guarantees that each process sends and delivers between one million (1,000k) and twenty-five million (25,000k) messages.

Latency. These order protocols calculate latency as the time difference between a process's initial transmission of a message m and the point at which all m destinations deliver m in total order, denoted as to the applications process. For example, let and be the time when sends a message to its CN0 and the time when the ACN(ACN0) delivers that message in total order respectively. Then defines the maximum latency delivery for that message. The average of 1000k to 25000k messages of such maximum latencies was computed, and the experiment was repeated 10 times for a confidence interval of 95%. The average maximum latency was plotted against the number of messages sent by each process.

Throughput. The throughput is calculated as the average number of total order messages delivered (aNoMD) by any process during the simulation time calculated, like latencies, with a 95% confidence interval. Similarly, to the latency, we also determined a 95% confidence interval for the average maximum throughput. Additionally, we presented the latency enhancements offered by the proposed protocol in comparison to LCR, as well as the throughput similarities.

All experiments were done independently to prevent any inadvertent consequences of running multiple experiments simultaneously. Nevertheless, the execution ensured each of the experiments was staggered to cover approximately the same amount of simulation time. This was done to sustain a uniform load on the ring-based and leader-based network across all of the experiments.

5.1. Results and Discussion

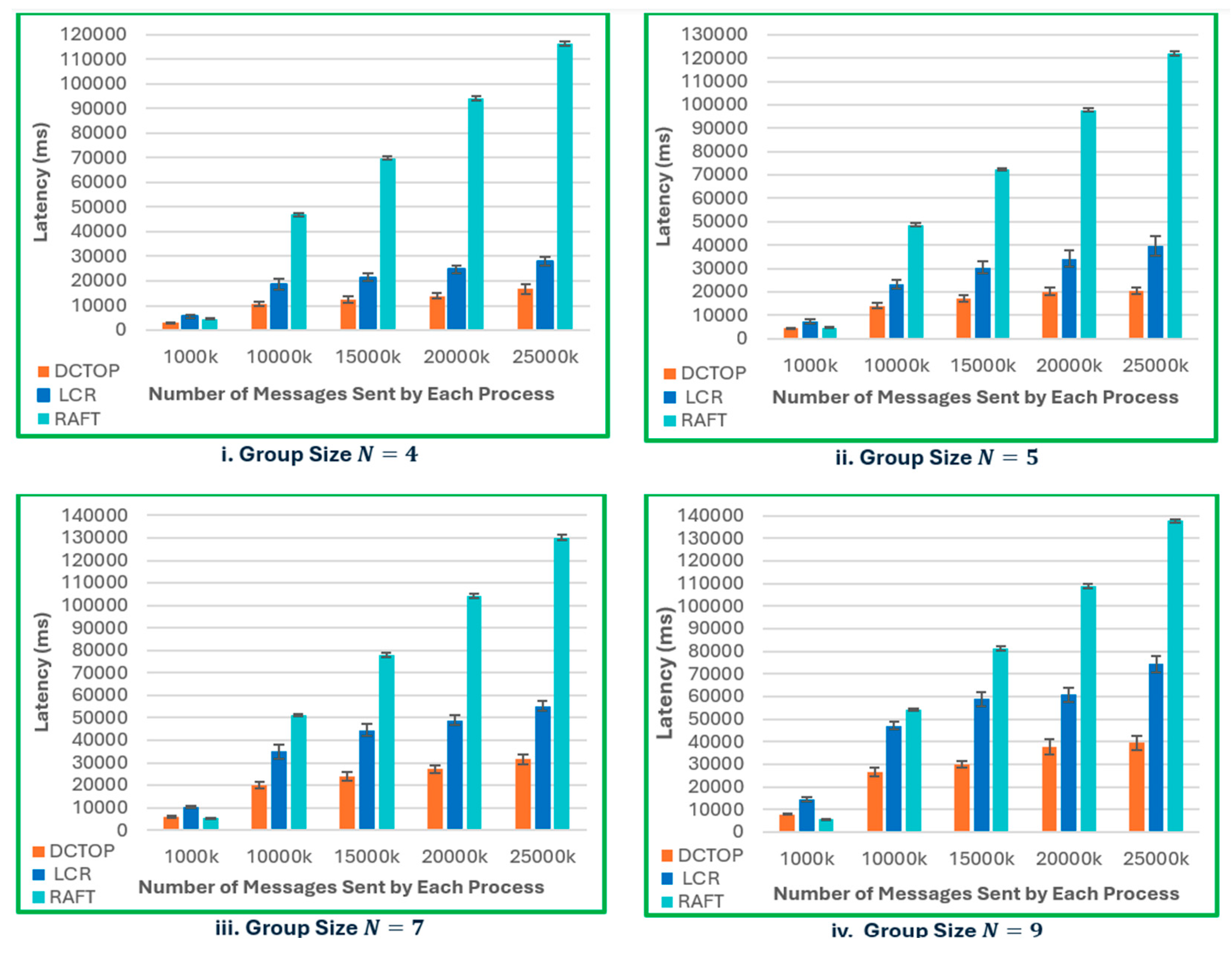

The latency analysis of DCTOP, LCR, and RAFT (see

Figure 8i-iv ) across varying group sizes (N = 4, 5, 7, and 9) and increasing message volumes reveals that DCTOP consistently demonstrates the lowest latency. This performance advantage is likely attributed to its use of Lamport logical clocks for efficient sequencing of concurrent messages, the assignment of a unique last process for each message originator, and a relaxed crash-failure assumption that permits faster message delivery. LCR shows moderately increasing latency with larger group sizes and message volumes, primarily due to its reliance on vector clocks whose size grows with the number of processes and the use of a globally fixed last process for message ordering, both of which contribute to increased message size and coordination cost. RAFT, a leader-based protocol, exhibits the highest latency overall, especially under higher load conditions, underscoring the limitations of centralized coordination. However, under lower traffic conditions (e.g., 1 million messages per process), RAFT performs competitively and, in configurations with N = 7 and N = 9, even outperforms DCTOP and LCR. This suggests that RAFT may remain suitable in low-load or moderately scaled environments.

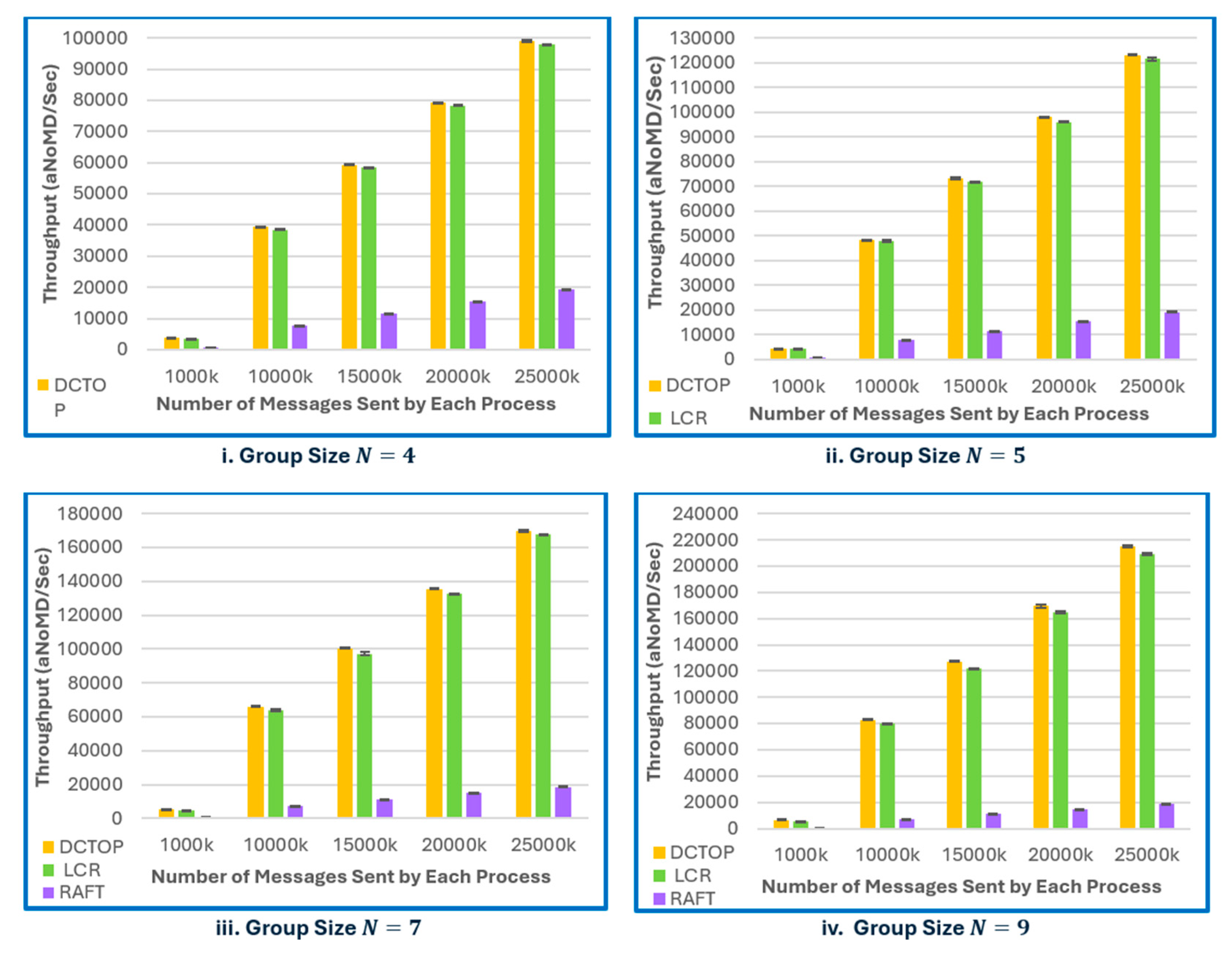

On the other hand, in terms of throughput (

Figure 9i-iv), DCTOP and LCR outperform RAFT across all group sizes and message volumes. Both are leaderless ring-based order protocols that benefit from decentralized execution, enabling all processes to independently receive and process client requests. This results in cumulative throughput, which scales linearly with group size. RAFT, by contrast, centralizes request handling at the leader, thereby limiting throughput to the leader’s processing capacity. The results demonstrate that DCTOP consistently achieves the highest throughput, with LCR following closely despite its minor overhead from vector timestamps and centralized ordering logic. RAFT consistently exhibits the lowest throughput, and its performance plateaus with increasing load, reinforcing the inherent scalability limitations of leader-based protocols in high-throughput environments.

Notably, all three protocols - RAFT, LCR, and DCTOP were implemented from a unified code base, differing only in protocol-specific logic. The experiments were conducted under identical evaluation setups and hardware configurations, ensuring a fair and unbiased comparison.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

In this work, DCTOP, a novel ring-based leaderless total order protocol that extends the traditional LCR approach was introduced through three key innovations: the integration of Lamport logical clocks for concurrent message sequencing, a new mechanism for dynamically identifying the last process per each message sender, and a relaxation of the traditional crash failure assumption. These modifications collectively contributed to significant latency reductions under varying system configurations. To promote fairness among process replicas, our simulation model incorporated control primitives to eliminate message-sending bias. A comparative performance evaluation of DCTOP and LCR using discrete-event simulation across group sizes of N = 4, 5, 7, and 9, and under concurrent message loads was conducted. The results yielded three major insights. First, DCTOP achieved over 43% latency improvement compared to LCR across all configurations, demonstrating the efficacy of Lamport logical clocks in this context. Second, the proposed dynamic last process mechanism proved to be an effective alternative to the globally fixed last process used in LCR, enabling faster message stabilization. Third, by relaxing the LCR crash tolerance condition from N = f + 1 to N = 2f + 1, DCTOP is able to deliver messages more quickly while still tolerating failures, further contributing to latency reduction. While our primary focus was on evaluating DCTOP relative to LCR, we included RAFT, a widely adopted leader-based protocol as a benchmark to contextualize our results. RAFT demonstrated competitive performance under light message loads, but its throughput and latency plateaued with scale due to its centralized coordination model. The goal was not to critique RAFT, but to highlight architectural differences and situate DCTOP within the broader spectrum of total order protocols.

Given that the primary goal of this study was to investigate the initial performance characteristics of DCTOP, we deliberately limited our evaluation to small group sizes (N ≤ 9) to enable controlled experimentation and isolate protocol-level behaviour. While this approach provides useful insight, it also introduces some limitations. The current implementation does not model process or communication failures, which are common in practical distributed systems. Furthermore, larger-scale deployments may exhibit additional performance dynamics not captured in this setting. As part of our ongoing work, we are developing a cloud-based, fault-tolerant implementation of DCTOP to validate these findings in more realistic environments, including under failure conditions and dynamic workloads.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LCR |

Logical Ring and Ring Protocol |

| DCTOP |

Daisy Chain Total Order Protocol |

| VC |

Vector Clock |

| LC |

Logical Clock |

| TO |

Total Order |

| CN |

Clockwise Neigbhour |

| ACN |

Anti-Clockwise Neigbhour |

| SC |

Stability Clock |

| DQ |

Delivery Queue |

| DCQ |

Garbage Collection Queue |

| UTO |

Uniform Total Order (uto) |

References

- Choudhury, G. Garimella, A. Patra, D. Ravi, and P. Sarkar, "Crash-tolerant consensus in directed graph revisited." In International Colloquium on Structural Information and Communication Complexity (pp. 55-71). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- M. Pease, R. Shostak, and L. Lamport, “Reaching agreement in the presence of faults,” Journal of the ACM (JACM), vol. 27, no. 2, 1980, pp. 228-234, . [CrossRef]

- E. W. Vollset, and P. D. Ezhilchelvan, "Design and performance-study of crash-tolerant protocols for broadcasting and reaching consensus in manets." In 24th IEEE Symposium on Reliable Distributed Systems, pp. 166-175.

- M. Correia, D. G. Ferro, F. P. Junqueira, and M. Serafini, "Practical hardening of crash-tolerant systems." In In Proceedings of the 2012 USENIX conference on Annual Technical Conference, pp. 453-466.

- M. Wiesmann, F. Pedone, A. Schiper, B. Kemme, and G. Alonso, "Understanding replication in databases and distributed systems." pp. 464-474. [CrossRef]

- Helal, A. A. Heddaya, and B. B. Bhargava, Replication techniques in distributed systems: Springer Science & Business Media, 2006.

- X. Défago, A. Schiper, and P. Urbán, “Total order broadcast and multicast algorithms: Taxonomy and survey,” ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR), vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 372-421, 2004, . [CrossRef]

- D. Ongaro, and J. Ousterhout, "In search of an understandable consensus algorithm (extended version)," Tech Report. May, 2014. http://ramcloud. stanford. edu/Raft. pdf, (Accessed on June 6, 2024).

- F. Junqueira, and B. Reed, ZooKeeper: distributed process coordination: " O'Reilly Media, Inc.", 2013.

- P. Hunt, M. Konar, F. P. Junqueira, and B. Reed, "{ZooKeeper}: Wait-free Coordination for Internet-scale Systems." In Proceedings of the 2010 USENIX conference on USENIX annual technical conference (USENIXATC'10).

- M. Burrows, "The Chubby lock service for loosely-coupled distributed systems." In Proceedings of the 7th symposium on Operating systems design and implementation (OSDI '06), pp. 335-350.

- Ejem, P. Ezhilchelvan,: Design and Performance Evaluation of High Throughput and Low Latency Total Order Protocol. In: 38th Annual UK Performance Engineering Workshop (2022).

- J. Pu, M. Gao, and H. Qu, “SimpleChubby: a simple distributed lock service.”, https://www.scs.stanford.edu/14au-cs244b/labs/projects/pu_gao_qu.pdf, (Accessed on May 31, 2024).

- L. Lamport, “Paxos made simple,” ACM SIGACT News (Distributed Computing Column) 32, 4 (Whole Number 121, December 2001), pp. 51-58, 2001.

- D. Ongaro, and J. Ousterhout, "In search of an understandable consensus algorithm." In Proceedings of the 2014 USENIX conference on USENIX Annual Technical Conference (USENIX ATC'14), pp. 305-319.

- K. Shvachko, H. Kuang, S. Radia, and R. Chansler, "The hadoop distributed file system." 2010 IEEE 26th Symposium on Mass Storage Systems and Technologies (MSST), 2010, doi: 10.1109/MSST.2010.5496972, pp. 1-10.

- Ejem, P. Ezhilchevan,: Design and performance evaluation of raft variations. In: 39th Annual UK Performance Engineering Workshop (2023).

- R. Guerraoui, R. R. Levy, B. Pochon, and V. Quéma, “Throughput optimal total order broadcast for cluster environments,” ACM Transactions on Computer Systems (TOCS), vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 1-32, 2010, . [CrossRef]

- Moraru, David G. Andersen, and M. Kaminsky. There is more consensus in Egalitarian parliaments. In: Proceedings of the 24th ACM Symposium on Operating Systems Principles, 2013, 358–372. [CrossRef]

- M. Biely, Z. Milosevic, N. Santos, and A. Schiper, "S-paxos: Offloading the leader for high throughput state machine replication." 2012 IEEE 31st Symposium on Reliable Distributed Systems, 2012, pp. 111-120. [CrossRef]

- R. Guerraoui, R. R. Levy, B. Pochon, and V. Quema. (2006). High Throughput Total Order Broadcast for Cluster Environments. In: International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks (DNS'06), 2006, pp. 549-557. [CrossRef]

- Toshniwal, S. Taneja, A. Shukla, K. Ramasamy, J. M. Patel, S. Kulkarni, J. Jackson, K. Gade, M. Fu, and J. Donham, "Storm@ twitter." pp. 147-156, In Proceedings of the 2014 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data (SIGMOD '14). [CrossRef]

- M. Chandy, and L. Lamport, “Distributed snapshots: Determining global states of distributed systems,” ACM Transactions on Computer Systems (TOCS), vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 63-75, 1985, . [CrossRef]

- Liskov, and J. Cowling. (2012). Viewstamped Replication Revisited. MIT Technical Report MIT-CSAIL-TR-2012-021, https://pmg.csail.mit.edu/papers/vr-revisited.pdf, (Acessed online on 07/04/2024).

- Birman, and T. Joseph, "Exploiting virtual synchrony in distributed systems." In Proceedings of the eleventh ACM Symposium on Operating systems principles (SOSP '87), pp. 123–138. [CrossRef]

- Y. Amir, and J. Stanton, The spread wide area group communication system. Johns Hopkins University. Center for Networking and Distributed Systems:[Technical Report: CNDS 98-4]. 1998, (Accessed on April 28, 2024).

- Ejem A., Njoku C. N., Uzoh O. F., Odii J. N, "Queue Control Model in a Clustered Computer Network using M/M/m Approach," International Journal of Computer Trends and Technology (IJCTT), vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 12-20, 2016. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).