1. Introduction

Oropharyngeal dysphagia (OD) is a highly prevalent condition among the older people, particularly those residing in long-term care facilities. Its prevalence ranges from 13% among functionally independent older adults to over 50% in institutionalized populations [

1]. OD significantly increases the risk of malnutrition, dehydration, aspiration pneumonia, and mortality [

2,

3]. These complications not only compromise patient quality of life but also place a substantial burden on healthcare systems, both clinically and economically [

14]. This underdiagnosed condition significantly worsens outcomes in frail older people, warranting structured and evidence-based interventions.[

1]

The pathophysiology of oropharyngeal dysphagia (OD) is multifactorial and primarily involves progressive neurodegenerative and structural changes that impair the complex coordination required for safe swallowing. Key mechanisms include lingual sarcopenia, reduced pharyngeal sensitivity, and neuromuscular dysfunction, which collectively delay laryngeal elevation and closure, impair hyoid bone excursion, and increase the risk of aspiration. These deficits are further exacerbated in frail or institutionalized older adults, where diminished muscle mass and reduced connective tissue elasticity compromise swallowing efficiency [

1,

5]. In stroke-related dysphagia, damage to cortical and subcortical swallowing centers disrupts the sensory-motor integration necessary for initiating and executing swallowing reflexes, with dysarthria and lower-limb motor deficits emerging as strong clinical indicators of impaired deglutition. Chronic microaspiration, a common consequence of dysphagia, is closely linked to pulmonary inflammation and recurrent respiratory infections, significantly elevating morbidity and mortality in this population [

15]. As such, early recognition and structured nutritional interventions are essential to prevent deterioration in both physiological and functional domains, particularly as chronic aspiration contributes to systemic inflammation and infection in vulnerable populations [

5].

To mitigate these risks, modified texture diets (MTDs) have become a standard intervention for OD, aiming to reduce aspiration risk while maintaining adequate nutritional intake [

3,

4]. However, traditional methods—typically involving manual pureeing of cooked meals—are limited by low caloric and protein density, poor palatability, limited variety, and inconsistent texture, which together lead to reduced food consumption and compromised nutritional adequacy [

6,

14]. These shortcomings often necessitate the use of oral nutritional supplements (ONS), thereby increasing healthcare costs and complicating care delivery [

7]. In response to these clinical and operational challenges, the International Dysphagia Diet Standardisation Initiative (IDDSI) introduced a globally recognized framework that classifies foods and fluids into standardized texture and thickness levels, from Level 0 (thin liquids) to Level 7 (regular, easy-to-chew foods) [

8]. While this system has improved safety and communication, its practical implementation remains uneven across settings due to the labor-intensive and subjective nature of manual texture modification [

1,

3]. Traditional blended meals frequently result in non-homogeneous textures characterized by inconsistent particle sizes and phase separation (e.g., solid-liquid stratification), which can be particularly dangerous for individuals with dysphagia. The presence of multiple consistencies within a single food item further elevates the risk of aspiration and diminishes the efficacy of the modified diet, ultimately compromising both nutritional intake and patient safety [

3,

6].

In recent years, technological innovations have advanced the field of dysphagia nutrition by enabling the development of industrially produced, standardized meals tailored to the specific needs of dysphagic patients. A notable example is the Dysphameal® system, which employs freeze-dried or dehydrated food matrices reconstituted on demand using an automated dispensing unit. This process ensures precise texture conformity with the International Dysphagia Diet Standardisation Initiative (IDDSI) levels—primarily Levels 3 (liquidized) and 4 (pureed)—while maintaining consistent nutrient composition and long-term stability [

9]. By removing variability from food preparation, the system aligns with food-first, patient-centered care models, supporting the dignity and autonomy of patients who rely on texture-modified diets [

6]. Within institutional care contexts, the WeanCare protocol integrates this technology into a structured clinical and operational framework, facilitating its application in long-term and post-acute care facilities [

11]. A mini-HTA (Health Technology Assessment) conducted by the Department of Health Sciences at the University of Genoa, with collaboration from multiple residential care institutions, identified several key advantages of Dysphameal® over conventional modified texture diets (MTDs). Among these are a significantly higher nutritional density—ranging from 1.2 to 1.3 kcal/g compared to 0.6 to 0.7 kcal/g in traditional blended meals [

9]—and enhanced palatability and visual appeal, which improve voluntary oral intake and mealtime satisfaction [

10]. The automation of meal preparation eliminates the need for manual blending, reducing the burden on kitchen and clinical staff and minimizing risks associated with texture inconsistency such as grittiness or phase separation [

9]. Moreover, the meals’ ability to be stored at room temperature and dispensed in modular portions optimizes logistical management and supports rapid, hygienic service delivery in institutional settings [

9]. Importantly, the HTA findings also highlight how Dysphameal® can reduce dependence on oral nutritional supplements (ONS), mitigate nutrition-related complications such as dehydration and constipation, and enhance patient satisfaction and nutritional autonomy. These outcomes are further substantiated by recent real-world observational data from facilities employing the WeanCare-Dysphameal® system, where patients demonstrated measurable improvements in muscle mass, hydration status, resting metabolic rate, and immunological biomarkers, alongside substantial time and cost savings in both kitchen operations and ward-level care delivery [

11,

12].Despite the growing body of evidence supporting texture-modified nutritional interventions, few studies have simultaneously addressed the clinical efficacy and the economic-organizational impact of such technologies. The present study aims to fill this gap by evaluating the WeanCare-Dysphameal® system across two Italian residential care facilities, focusing on improvements in nutritional status, care delivery efficiency, and cost-effectiveness.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This was a quasi-experimental, pre-post observational study conducted over six months in two Italian residential care facilities (Residenze Sanitarie Assistenziali, RSA).

The primary objective was to evaluate the organizational impact of a standardized, texture-modified nutritional protocol based on the Dysphameal® system, applied to institutionalized patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia (OD). The study was conducted in real-world conditions to reflect typical operational and patient care dynamics. Patients were involved due to clinical, nutritional, confirmation as in previous research of the effectiveness of the protocol on their side and no control group was included, because each patient served as their own baseline comparator.

2.2. Study Population

A total of 13 elder residents (≥75 years) were enrolled based on the following inclusion criteria:

Clinical diagnosis of oropharyngeal dysphagia, categorized as IDDSI level 3 (Liquidised) or level 4 (Pureed);

Documented risk or evidence of malnutrition (via weight loss, reduced food intake, or clinical indicators);

Continuous residence in the facility for at least three months prior to enrollment;

-

Provision of informed consent by the patient or their representative.

Exclusion criteria included:

End-of-life status or palliative care indication;

Need for enteral nutrition (PEG or nasogastric tube);

Severe acute infections at baseline.

2.3. Intervention and Data Collection Procedures

The intervention has been promoted by the istitution involved, the study had to observe output and outcome of the modification in food preparation and administration. Activities reported were based on the exclusive administration of meals and hydration products prepared using the Dysphameal® system in some of the guest of the residential facilities. This technology involves dehydrated or freeze-dried food matrices that are reconstituted and emulsified via a semi-automated dispenser, precisely calibrated to deliver consistencies aligned with the International Dysphagia Diet Standardisation Initiative (IDDSI), specifically Levels 3 and 4. Patients received all main meals (breakfast, lunch, dinner) as well as snacks and hydration products, including Level 3 IDDSI-compliant gelled water or thickeners. The system allows controlled incorporation of water and vegetable oil to meet defined rheological and caloric specifications, ensuring a high nutritional density (approximately 1.2–1.3 kcal/g), texture stability without phase separation, and minimal infrastructure requirements due to its modular and hygienic design. Prior to the intervention, multidisciplinary training sessions were conducted for all involved personnel—including nurses, dietitians, speech-language pathologists, and food service staff—to ensure consistent protocol adherence and compliance with IDDSI guidelines.

Data were collected at two time points: baseline (T0) and after six months (T6). Measurements were grouped into four domains. First, anthropometric and body composition parameters were assessed using bioelectrical impedance vector analysis (BIVA), capturing data on body weight, fat-free mass (FFM), skeletal muscle mass (ASMM), fat mass, fat-free mass index (FFMI), total body water (TBW), and basal metabolic rate (BMR). Second, biochemical parameters were obtained through routine blood tests, including albumin, total proteins, lymphocyte count, cholesterol, transferrin, C-reactive protein (CRP), and micronutrients such as vitamin D, vitamin B12, folate, iron, and creatinine. Third, functional and clinical indicators were evaluated using tools such as the EdFed Scale for feeding difficulties in dementia, the number of enemas administered per patient, level of autonomy during meals (e.g., spoon-feeding needs), and food intake assessed by quartiles of portion consumption. Lastly, organizational and economic parameters included kitchen and ward-level meal preparation time per patient, use of oral nutritional supplements (ONS), staff workload per shift, and monthly patient-level cost metrics related to supplementation, labor, and food waste.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were reported as means and standard deviations. Changes from baseline to follow-up were evaluated using paired t-tests (α = 0.05).

Pearson correlation analysis was used to explore associations between:

ASMM and BMR;

TBW and ASMM;

FFMI and weight.

Multiple linear regression models were constructed to identify the strongest predictors of improvement in skeletal muscle mass (ASMM), with explanatory variables including FFM, FM, BMR, FFMI, and TBW.

Regression model diagnostics included R2 and p-values. Significance was defined as p < 0.05, and all analyses were performed using standard statistical packages (e.g., SPSS or R).

3. Results

The results are organized into three domains: clinical-nutritional outcomes, functional and autonomy-related measures, and organizational-economic outcomes. All 13 patients completed the 6-month follow-up, and no adverse events were reported.

3.1. Clinical and Nutritional Improvements

3.1.1. Anthropometric and Body Composition Outcomes

All patients exhibited improvements in key indicators of nutritional status:

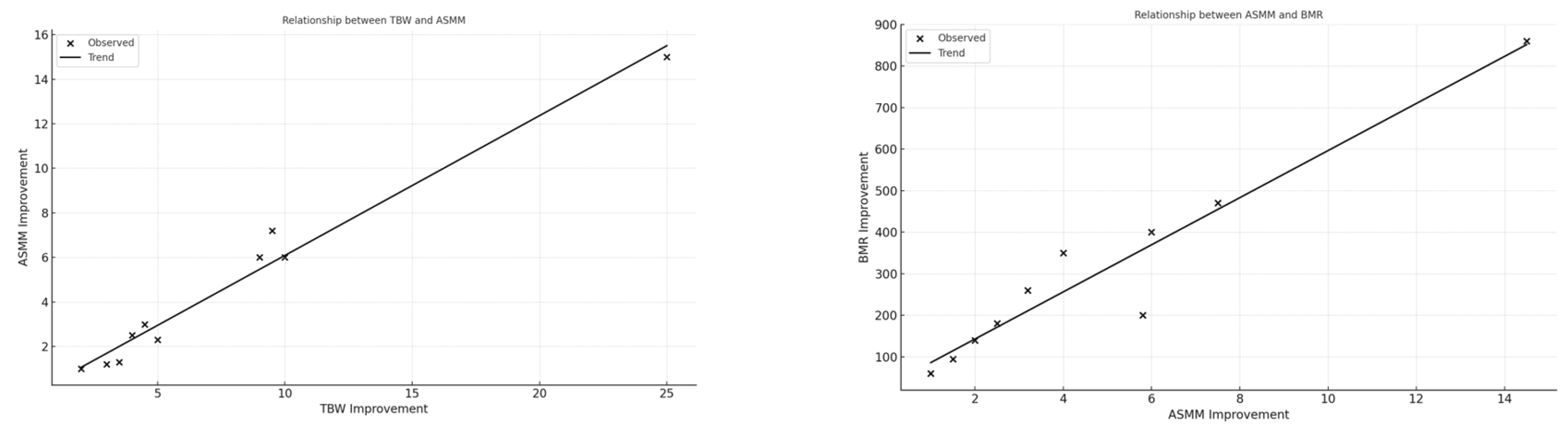

Fat-Free Mass (FFM) increased in 100% of patients (mean FFM = 14.7 kg, SD = 1.85 kg). Skeletal Muscle Mass (ASMM) improved in all patients (mean ASMM = 6.5 kg, SD = 1.2 kg). Fat-Free Mass Index (FFMI) and Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR) showed positive trends in 13/13 cases. Significant correlations were observed: ASMM strongly correlated with BMR (r = 0.94) and TBW (r = 0.98); FFM and ASMM correlated strongly with final weight (r = 0.83); Linear regression between TBW and ASMM showed an adjusted R2 = 0.96 (p < 0.001).

3.1.2. Biochemical Markers

Biochemical improvements were documented (

Table 1):

Albumin increased in 63.6% of patients (mean from 3.14 g/dL to 3.42 g/dL);

Lymphocyte count increased in 40% of patients, indicating enhanced immunological function;

Total cholesterol improved lowering in 70% of patients;

Mild improvements were noted in transferrin and CRP levels.

These trends suggest reduced inflammatory status and improved nutritional homeostasis, supporting previous findings on the impact of texture-modified, high-density diets.

3.2. Functional and Autonomy-Related Outcomes

The intervention also impacted functional indicators of nutritional well-being:

The average number of enemas per patient/month decreased from 1.25 to 0.43 (−66%) (

Table 2);

Feeding autonomy improved: 13 patients no longer required assisted spoon-feeding;

EdFed scores declined across the cohort, reflecting reduced feeding difficulties;

Average meal intake increased (assessed via quartile analysis), with over 80% of daily portions consumed spontaneously.

3.3. Functional and Autonomy-Related Outcomes

3.3.1. Time Savings in Kitchen and Ward

In the kitchen, the average meal preparation time per patient decreased from 6.24 to 3.58 minutes—a reduction of 44.83%. On the wards, approximately 7 minutes per patient per day were saved during breakfast and hydration routines, primarily due to replacing manual thickener mixing with pre-set gelled water. The total daily time savings are detailed in

Table 3.

3.3.2. Supplement and Cost Reductions

All patients discontinued oral nutritional supplements, resulting in an average reduction of 386 kcal and 21.3 grams of protein per patient per day. We used the following estimated labor costs: €0.2955 per minute for a nurse (ARAN, 2022), €0.2695 per minute for a kitchen chef, and €0.2270 per minute for a sous-chef (FIPE, 2024). For fresh food preparation, we assumed that 33% of the workload is handled by the kitchen chef and 67% by the sous-chef. In contrast, for the Dysphameal® system, we assumed 20% of the workload is managed by the kitchen chef and 80% by the sous-chef. A comparative table of the costs and preparation times for both fresh food and Dysphameal® is provided in

Table 4. All cost estimates are expressed in 2025 euros, adjusted for inflation based on the appropriate price indices for values originally calculated before 2025 (ISTAT, 2025).

We assumed that the cost of fresh food and Dysphameal® meals is equivalent, based on meal cost estimates from a previous study (Sebastiano, 2017). While the actual price of Dysphameal® is not currently available, it is expected to be similar to the manufacturer's quoted price. Due to this uncertainty, we conducted a sensitivity analysis comparing the prices of fresh food and Dysphameal® to better understand the potential cost savings of the intervention relative to the comparator. Electricity and equipment usage costs were derived from WeanCare study. Food thickener is required only for fresh food to ensure appropriate consistency and texture for patients. We assumed enema usage to be the same for both Dysphameal® and fresh food, with a daily cost of €0.05 per patient (Weancare).

The results show a total daily cost of €19.05713 (or €6,955.85 annually) for the fresh food and €13.93640 per day (or €5,086.79 annually) for Dysphameal®. This represents a daily saving of €5.12073, amounting to €1,869.06 annually with the use of Dysphameal®.

These findings underscore the multifaceted impact of the Dysphameal® system within the WeanCare protocol. As illustrated in

Section 3.1, improvements in nutritional biomarkers such as albumin and lymphocyte count suggest a systemic enhancement of nutritional and immune status, consistent with increased intake of protein and energy-dense meals. The scatter plots in Figure 1 and Figure 2 reveal strong physiological interdependencies, particularly between skeletal muscle mass and hydration (TBW), as well as between muscle accretion and metabolic rate (BMR), confirming the protocol’s metabolic efficacy. Notably, these correlations reinforce the hypothesis that optimized hydration and nutrient intake are foundational to improving musculoskeletal and functional health in frail older adults.

Beyond individual physiology, the intervention also yielded pronounced effects on daily care routines. As detailed in

Table 2, the frequency of enemas—a proxy for gastrointestinal function and fiber intake—dropped significantly, paralleling gains in muscle mass and TBW. The bar chart in Figure 3 visually supports this trend, emphasizing the association between improved body composition and reduced dependency on symptomatic interventions. The enhancement in feeding autonomy, shown by the decline in patients requiring spoon-feeding, further highlights the intervention’s capacity to restore dignity and reduce nursing burden.

From an organizational standpoint,

Table 3 and

Table 4 quantify the time and cost savings derived from streamlining meal preparation and eliminating oral nutritional supplements. These metrics reveal not only operational efficiency but also opportunities for reallocating clinical resources toward more complex care needs. Taken together, the integrated clinical, functional, and economic data affirm the Dysphameal® system as a viable and scalable innovation in dysphagia care.

3.3.3. Sensitivity Analysis on Disphameal® and Fresh Food Costs

As mentioned above, the absence of precise pricing information for Dysphameal® introduces uncertainty into the estimation of potential cost savings from adopting the intervention. To address this, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate how variations in the daily cost difference between Dysphameal® and fresh food affect overall savings for feeding a single patient.

| Cost difference between Disphameal® and fresh food |

Daily Cost savings (euros) |

Yearly Cost savings (euros) |

Cost saving product |

| -5 euros |

10,12072503 |

3694,064635 |

Disphameal® |

| -4 euros |

9,120725027 |

3329,064635 |

Disphameal® |

| -3 euros |

8,120725027 |

2964,064635 |

Disphameal® |

| -2 euros |

7,120725027 |

2599,064635 |

Disphameal® |

| -1 euro |

6,120725027 |

2234,064635 |

Disphameal® |

| 0 euro |

5,120725027 |

1869,064635 |

Disphameal® |

| 1 euro |

4,120725027 |

1504,064635 |

Disphameal® |

| 2 euros |

3,120725027 |

1139,064635 |

Disphameal® |

| 3 euros |

2,120725027 |

774,0646347 |

Disphameal® |

| 4 euros |

1,120725027 |

409,0646347 |

Disphameal® |

| 5 euros |

0,120725027 |

44,06463473 |

Disphameal® |

| 6 euros |

-0,879274973 |

-320,9353653 |

Fresh food |

| 7 euros |

-1,879274973 |

-685,9353653 |

Fresh food |

The table shows that Dysphameal® remains a cost-saving option as long as its price does not exceed that of fresh food by more than €5.12 per patient per day. At a cost difference of exactly €5.12, both options result in equivalent total costs. If the cost of Dysphameal® exceeds fresh food by more than €5.12 per day, then fresh food becomes the more economical choice. This sensitivity analysis helps quantify the financial threshold at which Dysphameal® transitions from a cost-saving to a cost-incurring intervention.

4. Discussion

The findings from this study confirm the significant clinical, functional, and organizational benefits of implementing the WeanCare protocol using Dysphameal® technology in long-term care settings for older patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia (OD). By aligning with the IDDSI framework and leveraging a standardized, high-nutrient meal delivery system, the intervention addressed key limitations of traditional modified texture diets (MTDs), including poor consistency, inadequate nutrient density, and labor-intensive preparation.

4.1. Nutritional and Clinical Improvements

As anticipated, the nutritional outcomes reflect the central tenets of the intervention’s rationale: improved intake leads to improved body composition and metabolic recovery. Consistent with the pathophysiological understanding that OD patients are at high risk of malnutrition and sarcopenia [

1,

2,

3], we observed significant improvements in fat-free mass (FFM), skeletal muscle mass (ASMM), and basal metabolic rate (BMR). The strong correlations between ASMM and both total body water (TBW) and BMR support existing evidence that muscular recovery is linked not only to macronutrient intake but also to adequate hydration status and metabolic stimulation [

4,

5,

6].

Importantly, these improvements were achieved without the use of external oral nutritional supplements (ONS), which were completely discontinued. This is a clinically relevant finding: not only does it reflect the efficacy of the Dysphameal® meals in delivering caloric and protein needs (up to 1.3 kcal/g), but it also aligns with recent literature advocating for integrated, food-first approaches over supplemental nutrition in institutionalized older adults [

7,

8]. This supports growing evidence that integrated, non-supplement-based interventions can effectively meet protein-energy needs [

6]

Biochemical markers corroborated the anthropometric improvements. Albumin levels increased in nearly two-thirds of patients, while lymphocyte counts and cholesterol values improved in substantial proportions. Though not all biochemical parameters improved universally—iron and folate levels remained low in several patients—these findings may reflect underlying comorbidities, absorption issues, or long-standing deficiencies that require targeted interventions beyond nutritional texture standardization alone. These gains mirror outcomes from recent studies demonstrating improved muscle strength and metabolism in dysphagic patients receiving nutrient-dense, care-optimized meals [

10].

4.2. Functional Recovery and Patient Autonomy

Feeding autonomy is a critical quality-of-life indicator in dysphagic populations, particularly among individuals with cognitive impairment or physical frailty. The WeanCare-Dysphameal® protocol notably reduced the number of patients requiring spoon-feeding, an outcome with both clinical and ethical implications. This change, supported by improved EdFed scores, reflects the role of sensory recognition, palatability, and standard texture in enhancing spontaneous food intake and promoting independence [

9].

Moreover, the significant reduction in enema use suggests improved gastrointestinal motility, likely attributable to better hydration and fiber intake inherent in the standardized, rehydrated meals and gelled water systems. This outcome is not trivial: constipation is a common and often overlooked burden in older adults, frequently leading to discomfort, polypharmacy, and nursing intervention time [

10].

4.3. Organizational and Economic Impact

One of the most compelling findings of this study lies in its implications for operational efficiency. Preparation time for dysphagic meals in the kitchen decreased by 44%, with a further 7 minutes/day/patient saved in the ward, primarily in hydration and breakfast routines. In facilities with limited staffing and increasing demands, such time savings—amounting to nearly 3 hours/day for 20 dysphagic patients—translate into tangible organizational benefits. Time reduction in foodservice tasks aligns with reports from other care homes adopting semi-automated dysphagia protocols [

9,

11]

Furthermore, the ability to delegate preparation tasks to non-specialized staff—after minimal training—represents a shift in workforce strategy, especially valuable in contexts where experienced culinary or clinical personnel are scarce during certain shifts. This aspect enhances the system’s scalability across various residential care settings.

From an economic standpoint, the intervention eliminated the need for ONS and reduced nursing time dedicated to feeding and symptom management, reinforcing that the clinical gains of Dysphameal® are effective, considering health outcomes and cost-saving as it reduces the overall costs with respect to the manual preparation of the meals using fresh ingredients. This represent an interesting and crucial consideration in healthcare systems facing resource constraints.

4.4. Integration with Existing Literature

These findings build upon previous studies highlighting the limitations of traditional blended diets and the value of standardized texture-modified meals [

11,

12,

13]. Raheem et al. (2021) and Ballesteros-Pomar et al. (2020) emphasized that conventional MTDs often fail to meet both safety and nutritional adequacy criteria, especially when prepared manually. Our results directly confirm and expand upon these concerns by demonstrating measurable improvements across nutritional, functional, and organizational domains when standardized, IDDSI-compliant meals are implemented.

Moreover, the observed improvements in ASMM and hydration (TBW) parallel the findings of Vucea et al. (2018), who associated better nutritional profiles with decreased reliance on symptomatic interventions like enemas and ONS. Our study adds a pragmatic dimension to these associations by quantifying operational and cost reductions in real-world settings.

Our findings corroborate those of prior WeanCare implementations, which also reported improved caregiver efficiency and nutritional outcomes. [

12,

13]

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

While the present findings are operationally significant and support the clinical utility of the WeanCare-Dysphameal® system, certain limitations should be acknowledged. The relatively small sample size and the lack of a control group may constrain statistical power and limit the generalizability of results, particularly regarding clinical endpoints. However, it is important to contextualize this study within its primary aim: to evaluate the organizational and economic implications of transitioning from traditional blended texture-modified foods (TMFs) to a standardized, industrially prepared alternative. The focus of this investigation was not to re-establish the clinical efficacy of the Dysphameal® protocol—which has been rigorously documented in earlier research, including our previously published study—but rather to monitor implementation fidelity and confirm that clinical and nutritional outcomes remain consistent with those prior findings. The current cohort was followed to verify alignment with those established quality of life and health-related benefits. Nonetheless, additional large-scale, multi-center studies—preferably randomized controlled trials—are warranted to explore long-term sustainability, patient-reported outcomes (e.g., satisfaction, sensory acceptance), and broader applicability across diverse institutional settings.

5. Conclusions

The implementation of the WeanCare protocol using Dysphameal® technology offers a comprehensive and effective approach to managing oropharyngeal dysphagia in institutionalized older populations. This intervention significantly improved patients’ nutritional status, muscle mass, and functional autonomy while reducing the reliance on oral nutritional supplements and the incidence of constipation.

Beyond its clinical benefits, the protocol demonstrated substantial organizational and economic advantages. Time savings in both kitchen and ward settings, reduced need for specialized staff, and enhanced workflow flexibility illustrate its strong potential for integration into diverse care environments.

By delivering standardized, IDDSI-compliant meals with high nutritional density, the WeanCare-Dysphameal® system addresses critical gaps in traditional modified texture diets, offering a scalable, safe, and economically sustainable solution. These results support the adoption of texture-modified nutritional technologies as part of a broader strategy to improve geriatric care quality and operational efficiency in long-term care settings.

Future research should focus on larger-scale studies and include quality-of-life outcomes, long-term cost-effectiveness, and satisfaction metrics to further validate and optimize this approach.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, CM; MZ; And ARR.; methodology, PL and MZ.; software, MZ MDN.; validation, PL; GC. and MZ.; formal analysis, MD.; investigation, CM; AT.; resources, AT.; data curation, AT; SR.; writing—original draft preparation, MDN; PL; MZ.; writing—review and editing, ARR; MZ.; visualization, AB; GC; ARR; MZ.; supervision, AB; MZ.; project administration, ARR.; funding acquisition, CM. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a unconditional contribution by HARG SB srl; Via Cefalonia, 70 25124 Brescia (BS)—Italia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was aquired from Ligurian Territorial Ethical Committee (CET Liguria)with protocol 16/2020 (Study number 677/2020) 16/12/2020, for the Weancare project.

Informed Consent Statement

The observational design was referred to routine nutritional care procedures improved from the Residential facilities involved. Informed consent was obtained from all patients or their legal guardians

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation |

Full Term |

| OD |

Oropharyngeal Dysphagia |

| MTD |

Modified Texture Diet |

| IDDSI |

International Dysphagia Diet Standardisation Initiative |

| FFM |

Fat-Free Mass |

| ASMM |

Appendicular Skeletal Muscle Mass |

| BMR |

Basal Metabolic Rate |

| FFMI |

Fat-Free Mass Index |

| TBW |

Total Body Water |

| FM |

Fat Mass |

| CRP |

C-Reactive Protein |

| ONS |

Oral Nutritional Supplements |

| RSA |

Residential Care Facility |

| BIVA |

Bioelectrical Impedance Vector Analysis |

| EdFED |

Edinburgh Feeding Evaluation in Dementia Scale |

| CET Liguria |

Ligurian Territorial Ethical Committee |

| HTA |

Health Technology Assessment |

References

- Yang S, Park JW, Min K, Lee YS, Song YJ, Choi SH, Kim DY, Lee SH, Yang HS, Cha W, Kim JW, Oh BM, Seo HG, Kim MW, Woo HS, Park SJ, Jee S, Oh JS, Park KD, Jin YJ, Han S, Yoo D, Kim BH, Lee HH, Kim YH, Kang MG, Chung EJ, Kim BR, Kim TW, Ko EJ, Park YM, Park H, Kim MS, Seok J, Im S, Ko SH, Lim SH, Jung KW, Lee TH, Hong BY, Kim W, Shin WS, Lee YC, Park SJ, Lim J, Kim Y, Lee JH, Ahn KM, Paeng JY, Park J, Song YA, Seo KC, Ryu CH, Cho JK, Lee JH, Choi KH. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Oropharyngeal Dysphagia. Ann Rehabil Med. 2023 Jul;47(Suppl 1):S1-S26. doi: 10.5535/arm.23069. Epub 2023 Jul 30. PMID: 37501570; PMCID: PMC10405672.

- Hansen T, Beck AM, Kjaersgaard A, Poulsen I. Second update of a systematic review and evidence-based recommendations on texture modified foods and thickened liquids for adults (above 17 years) with oropharyngeal dysphagia. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2022 Jun;49:551-555. doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2022.03.039. Epub 2022 Apr 6. PMID: 35623866.

- Ballesteros-Pomar MD, Cherubini A, Keller H, Lam P, Rolland Y, Simmons SF. Texture-Modified Diet for Improving the Management of Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Nursing Home Residents: An Expert Review. J Nutr Health Aging. 2020;24(6):576-581. doi: 10.1007/s12603-020-1377-5. PMID: 32510109.

- Wu XS, Yousif L, Miles A, Braakhuis A. A Comparison of Dietary Intake and Nutritional Status between Aged Care Residents Consuming Texture-Modified Diets with and without Oral Nutritional Supplements. Nutrients. 2022 Feb 5;14(3):669. doi: 10.3390/nu14030669. PMID: 35277028; PMCID: PMC8839380.

- Smithard DG, Yoshimatsu Y. Pneumonia, Aspiration Pneumonia, or Frailty-Associated Pneumonia? Geriatrics (Basel). 2022 Oct 18;7(5):115. doi: 10.3390/geriatrics7050115. PMID: 36286218; PMCID: PMC9602119.

- Wu X, Yousif L, Miles A, Braakhuis A. Exploring Meal Provision and Mealtime Challenges for Aged Care Residents Consuming Texture-Modified Diets: A Mixed Methods Study. Geriatrics (Basel). 2022 Jun 15;7(3):67. doi: 10.3390/geriatrics7030067. PMID: 35735772; PMCID: PMC9222299.

- Vucea V, Keller HH, Morrison JM, Duizer LM, Duncan AM, Carrier N, Lengyel CO, Slaughter SE, Steele CM. Modified Texture Food Use is Associated with Malnutrition in Long Term Care: An Analysis of Making the Most of Mealtimes (M3) Project. J Nutr Health Aging. 2018;22(8):916-922. doi: 10.1007/s12603-018-1016-6. PMID: 30272093.

- Okkels SL, Saxosen M, Bügel S, Olsen A, Klausen TW, Beck AM. Acceptance of texture-modified in-between-meals among old adults with dysphagia. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2018 Jun;25:126-132. doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2018.03.119. Epub 2018 Mar 31. PMID: 29779807.

- Crippa C, Matteucci S, Pastore M, Morenghi E, Starace E, De Pasquale G, Pieri G, Soekeland F, Gibbi SM, Lo Cricchio G, Zorloni A, Mazzoleni B, Mancin S. A Comparative Evaluation of the Caloric Intake and Economic Efficiency of Two Types of Homogenized Diets in a Hospital Setting. Nutrients. 2023 Nov 9;15(22):4731. doi: 10.3390/nu15224731. PMID: 38004125; PMCID: PMC10675474.

- Han H, Park Y, Kwon H, Jeong Y, Joo S, Cho MS, Park JY, Jung HW, Kim Y. Newly developed care food enhances grip strength in older adults with dysphagia: a preliminary study. Nutr Res Pract. 2023 Oct;17(5):934-944. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2023.17.5.934. Epub 2023 Jul 18. PMID: 37780213; PMCID: PMC10522817.

- Zanini, M., Catania, G., Ripamonti, S., Watson, R., Romano, A., Aleo, G., Timmins, F., & Sasso, L. (2021). The WeanCare nutritional intervention in institutionalized dysphagic older people and its impact on nursing workload and costs: A quasi-experimental study. Journal of Nursing Management, 29(8), 2620-2629. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13435.

- Zanini, M., Simonini, M., Giusti, A., Aleo, G., Ripamonti, S., Delbene, L., Musio, M.E., Sasso, L., Catania, G., & Bagnasco, A. (2024). Improvement of Quality of Life in Parkinson's Disease through Nutritional Intervention: A Case Study. Geriatrics, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.3390/xxxxx.

- Zanini M, Catania G, Di Nitto M, Delbene L, Ripamonti S, Musio ME, Bagnasco A. Healthcare Workers' Attitudes Toward Older Adults' Nutrition: A Descriptive Cross-Sectional Study in Italian Nursing Homes. Geriatrics (Basel). 2025 Jan 16;10(1):13. doi: 10.3390/geriatrics10010013. PMID: 39846583; PMCID: PMC11755615.

- Donaldson, A. I. C., Johnstone, A. M., & Myint, P. K. (2019). Optimising Nutrition and Hydration in Care Homes—Getting It Right in Person Rather than in Policy. Geriatrics, 4(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics4010001.

- Lu, C., Zhou, Y., Shen, Y., Wang, Y., & Qian, S. (2025). Establishment and validation of early prediction model for post-stroke dysphagia. Aging clinical and experimental research, 37(1), 145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-025-03060-1.

- Sebastiano, A.—Costi e modelli organizzativi del servizio di ristorazione: evidenze empiriche dall'osservatiorio settoriale sulle RSA.LIUC University, Osservatiorio settoriale sulle RSA. Castellanza (Italy), May 4th, 2017—Available at https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://www.casalendinara.it/documenti/laboratori-seminariali-2017/laboratorio-del-05-05-17%3Fdownload%3D66:dr-antonio-sebastiano&ved=2ahUKEwiEwM6P8K-OAxUmgf0HHQdSCdYQFnoECCQQAQ&usg=AOvVaw2V5FM7oA-OPIWQUGXjDZir (last access on July 3rd, 2025).

- FIPE (Federazione Italiana Pubblici Esercizi)- 2024 Accordo integrativo all'ipotesi d'accordo di rinnovo del contratto collettivo nazionale di lavoro per i dipendenti da aziende di settori pubblici esercizi, ristorazione collettiva, e commerciale e turismo del 5 giugno 2024—https://www.fipe.it/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Rinnovo-Contratto-CCNL-2024.pdf (last access on July 3rd, 2025).

- ARAN 2022—Contratto Collettivo Nazionale di Lavoro relativo al personale del comparto sanità trienno 2019-2021—https://www.aranagenzia.it/documento_pubblico/contratto-collettivo-nazionale-di-lavoro-relativo-al-personale-del-comparto-sanita-triennio-2019-2021/ (last access on last access on July 3rd, 2025).

- ISTAT—Istituto Nazionale di Statistica—Indice dei prezzi per le rivalutazioni monetarie—https://www.istat.it/notizia/indice-dei-prezzi-per-le-rivalutazioni-monetarie/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).