Submitted:

04 September 2025

Posted:

04 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

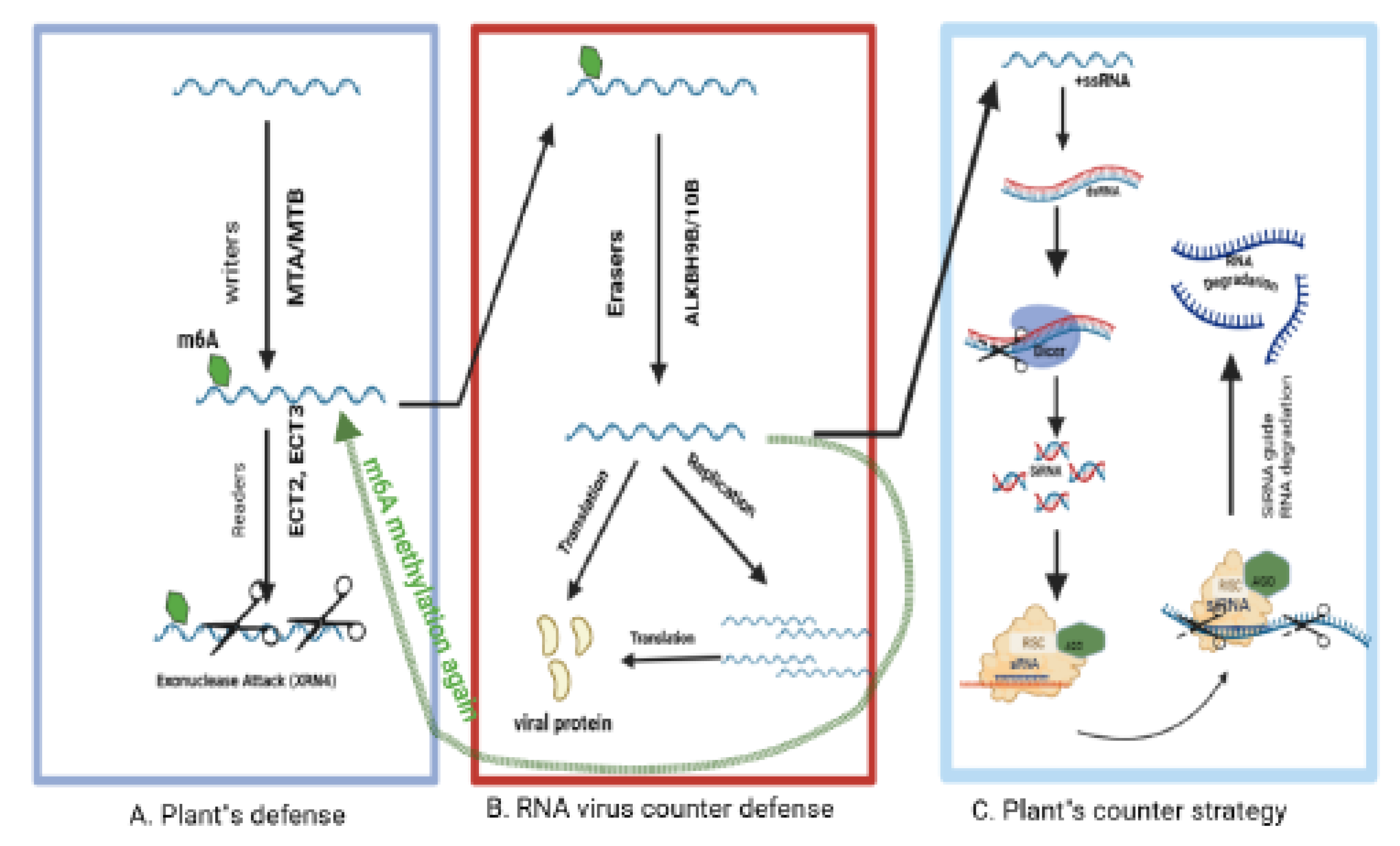

Abstract

Keywords:

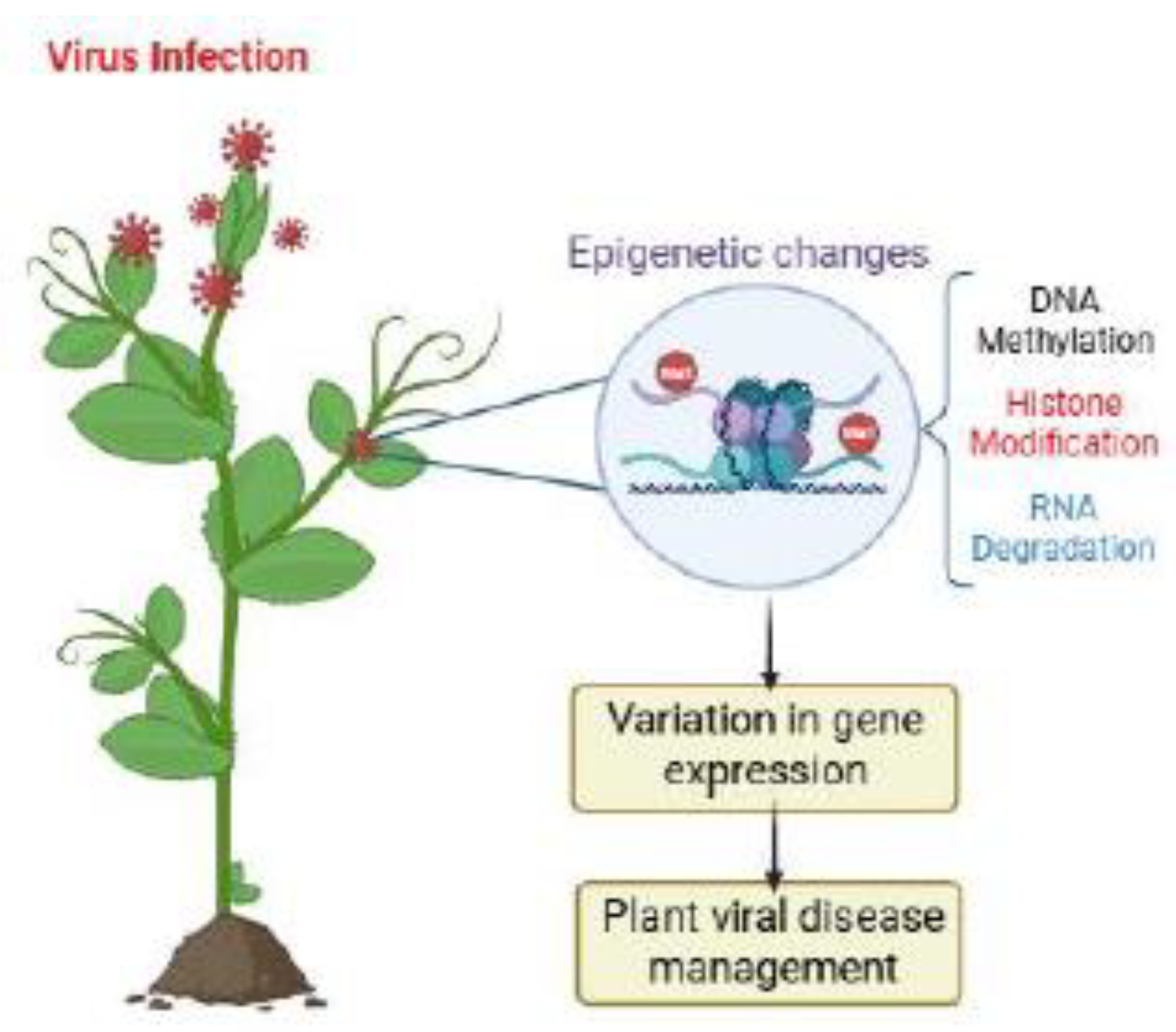

1. Introduction

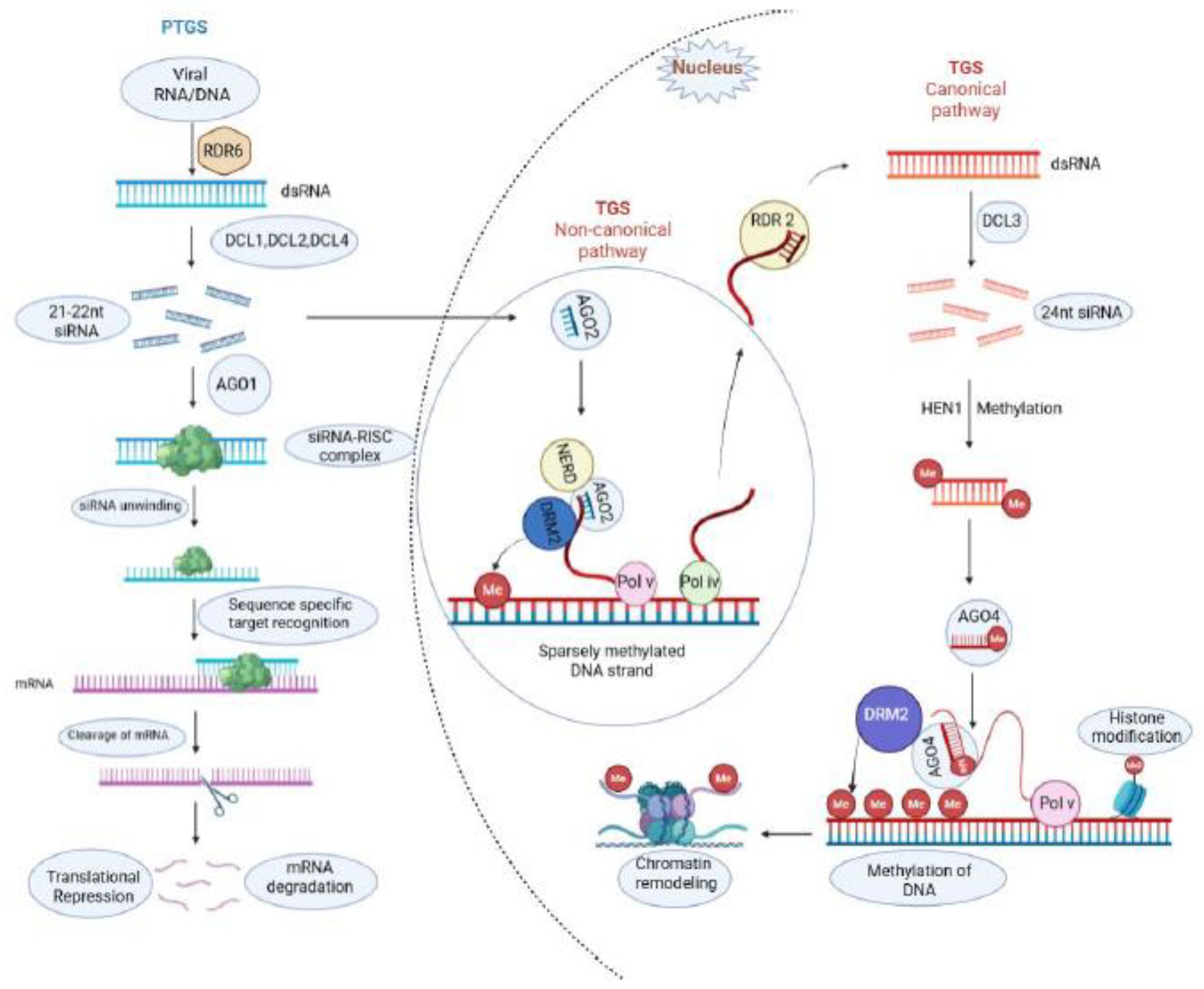

2. Epigenetic Gene Silencing

2.1. Post Transcriptional Gene Silencing

2.2. Transcriptional Gene Silencing

3. Plant Genome Modifications and Epigenetic Silencing

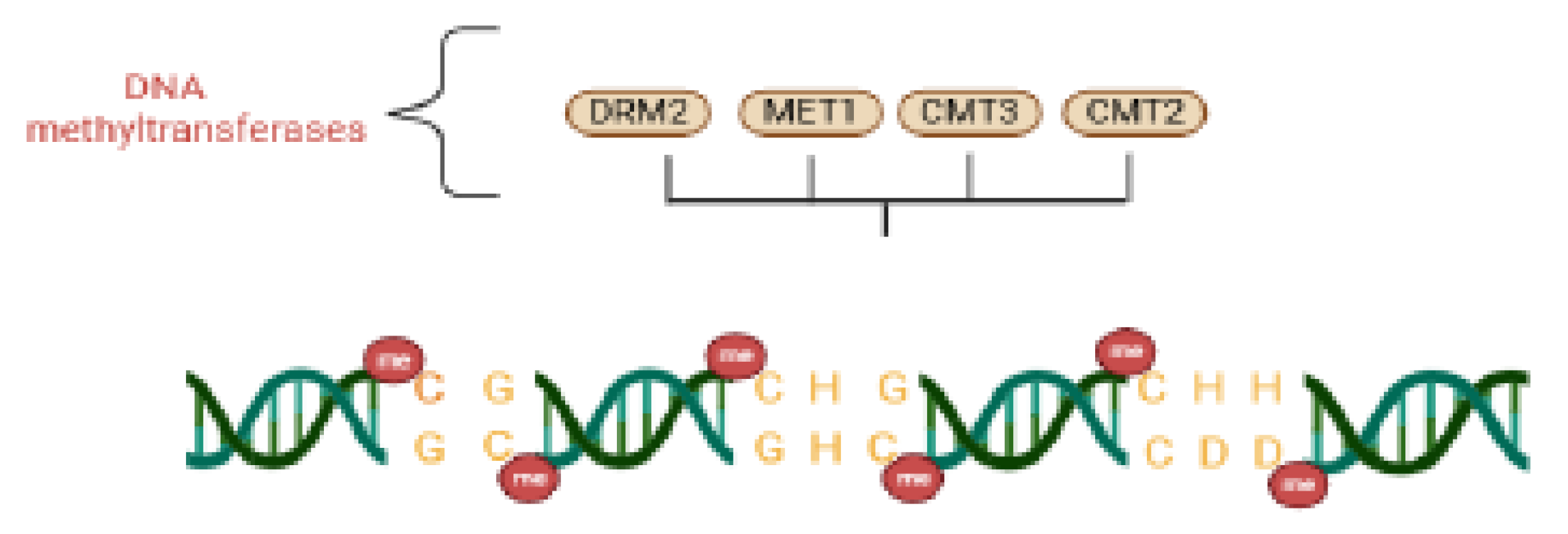

3.1. Plant DNA

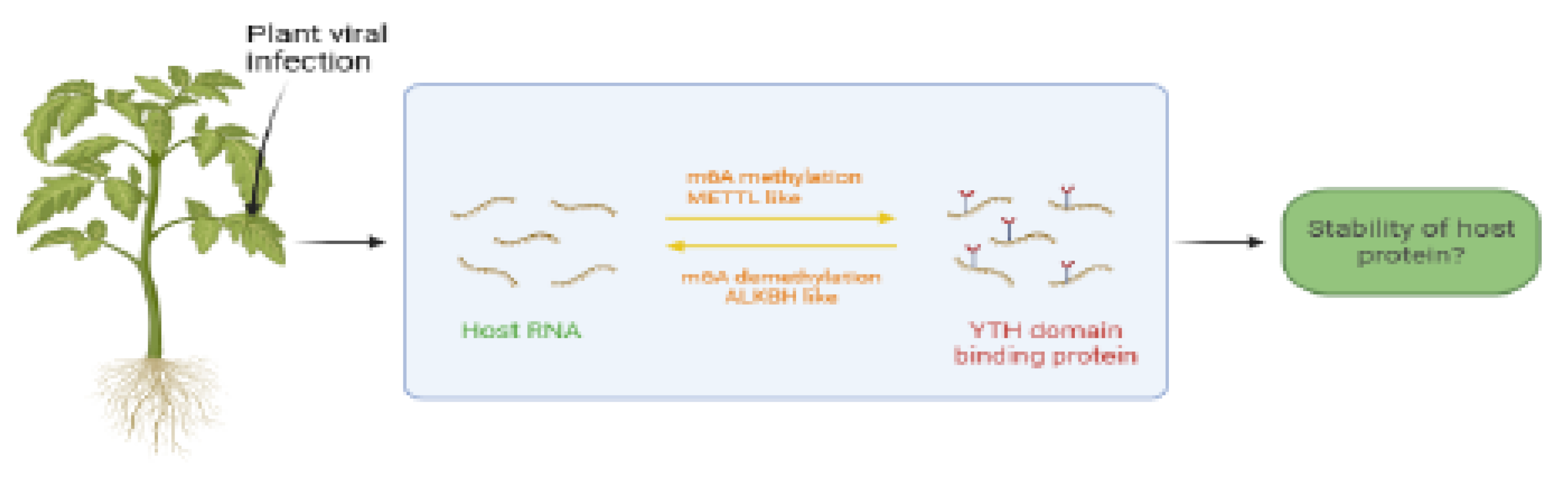

3.2. Plant RNA

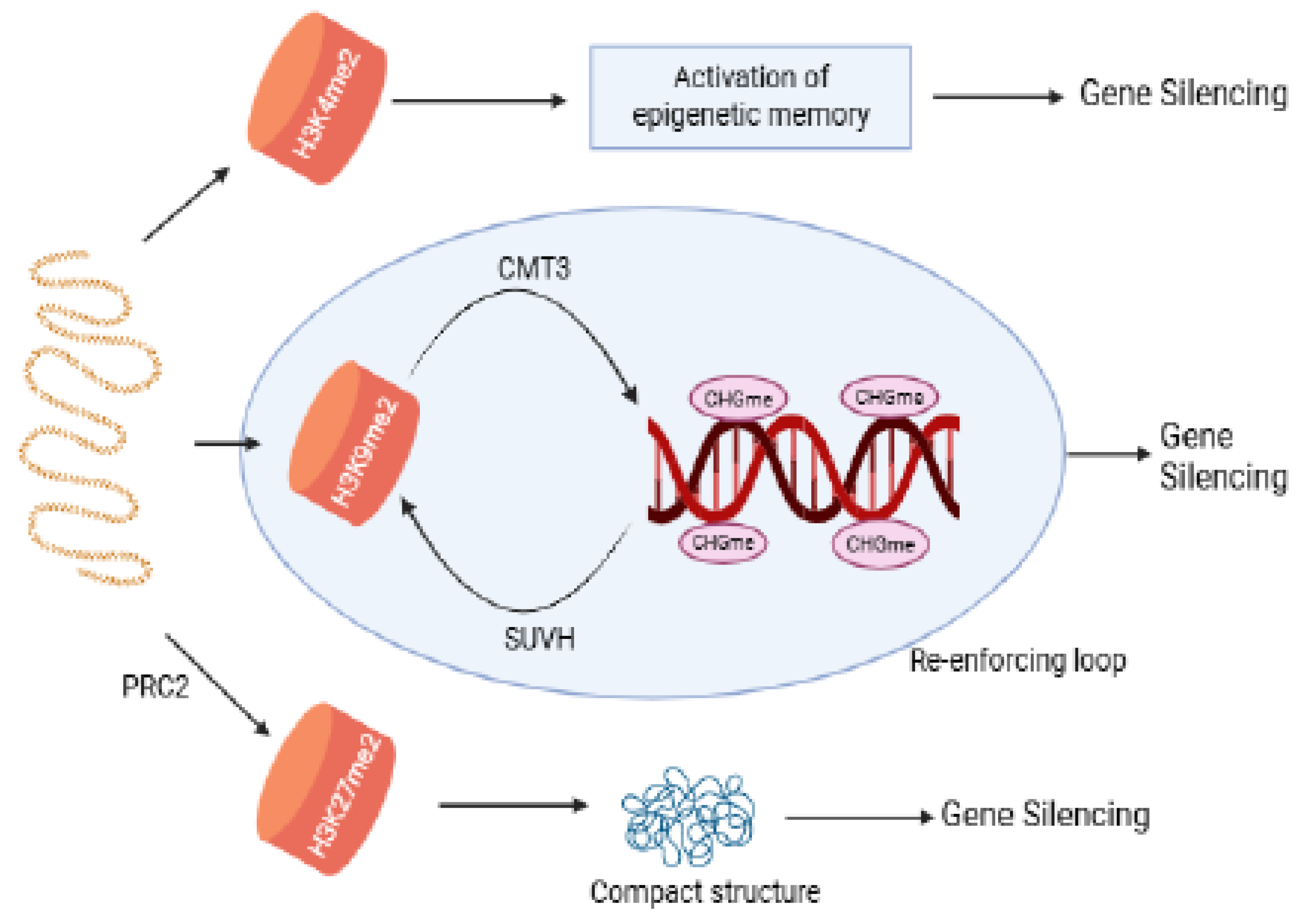

3.3. Plant Histones

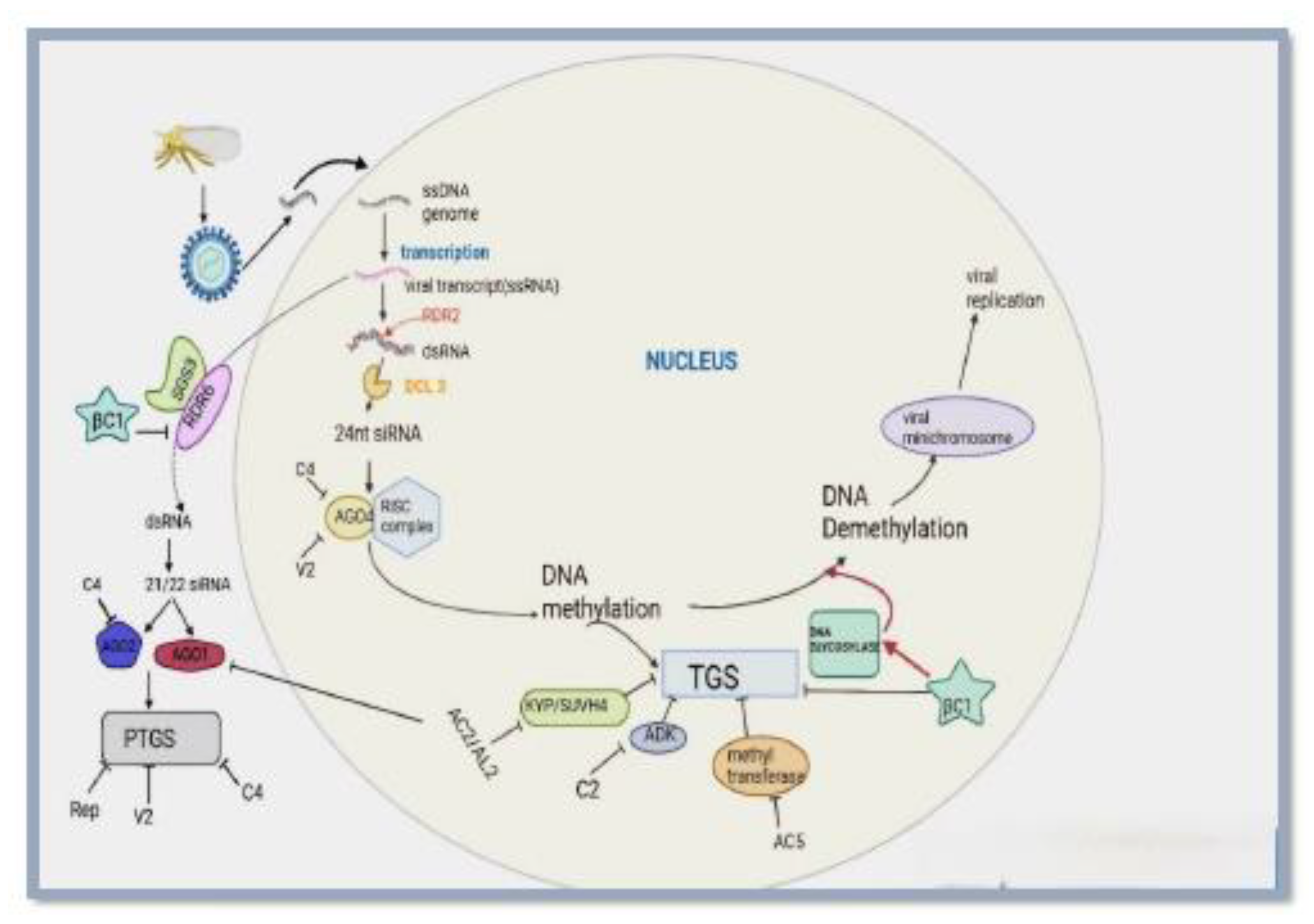

4. Epigenetic Gene Silencing of Plant DNA Viruses

5. Epigenetic Gene Silencing of Plant RNA Viruses

6. Future Perspectives and Potential Applications of Epigenetic Gene Silencing in Plant Virus Management

6.1. Virus Detection and Diagnostic Applications

6.2. Functional Genomics Using Virus-Induced Gene Silencing

6.3. Engineering Viral Resistance Through Epigenetic Modifications

6.4. Exogenous Epigenetic-Based Virucides

| Molecular Component | Category/Type | Associated Pathway (PTGS/RdDM) | Primary Function | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DCL2, DCL4 | Dicer-like RNase III enzymes | PTGS (DCL4/DCL2); RdDM (DCL2) | DCL4 makes 21-nt siRNAs for PTGS; DCL2 makes 22-nt siRNAs for antiviral silencing and non-canonical RdDM | Erdmann & Picard, 2020; Jin et al.; 2022; Wambui Mbichi et al.; 2020 |

| DCL3 | Dicer-like RNase III enzyme | Canonical RdDM | Processes dsRNA into 24-nt siRNAs that guide DNA methylation in the RdDM pathway | Matzke & Mosher, 2014; Stroud et al.; 2013 |

| RDR6 | RNA dependent RNA polymerase | PTGS, Non-canonical RdDM | Converts single-stranded RNAs to double stranded RNAs for processing into21–22nt siRNAs by DCL1, DCL2and DCL4 | Matzke et al.; 2015 |

| RDR2 | RNA dependent RNA polymerase | Canonical RdDM | Converts Pol IV–derived ssRNAs into dsRNAs, which are processed by DCL3 into 24-nt siRNAs. | Blevins et al.; 2015; Matzke et al.; 2015 |

| AGO1 | Argonaut protein | PTGS | Forms RISC with 21–22 nt siRNAs to recognize and cleave complementary mRNAs. | Fang & Qi, 2016; Matzke et al.; 2015; Voinnet, 2008 |

| AGO2 | Argonaute protein | Non canonical RdDM | Loads 21–22 nt siRNAs to target Pol V transcripts and facilitates DRM2 recruitment for DNA methylation. | Erdmann & Picard, 2020 |

| AGO4 | Argonaute protein | Canonical RdDM | Loads 24-nt siRNAs to target Pol V transcripts and recruits DRM2 for DNA methylation. | Erdmann & Picard, 2020 |

| NERD | Plant-specific protein (PHD and zinc-finger domains) | Non-canonical RdDM | Interacts with histone H3 and AGO2–siRNA complexes to promote histone modification and transcriptional repression. | Matzke & Mosher, 2014 |

| DRM 2 | DNA methyltransferase | Canonical & non-canonical RdDM | Catalyzes de novo cytosine DNA methylation guided by AGO–siRNA complexes. | Matzke et al.; 2015 |

| HEN1 | RNA methyltransferase | PTGS, All RdDM | Adds a 2′-O-methyl group to the 3′ end of siRNAs, protecting them from degradation | Yang et al.; 2018 |

| Viral Protein | Virus | Host Target | Effect on Epigenetic Gene Silencing | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rep (Replication-associated protein) | Tomato yellow leaf curl Sardinia virus (TYLCSV) | MET1, CMT3 | Reduces maintenance DNA methylation (CG context), weakening transcriptional gene silencing (TGS) | Rodríguez-Negrete et al.; 2013 |

| AC2 | Tomato golden mosaic virus (TGMV), Cabbage leaf curl virus (CaLCuV) | SUVH4/KYP (H3K9 histone methyltransferase) | Inhibits histone methylation, disrupting chromatin-based TGS | Veluthambi & Sunitha, 2021 |

| C2 | Beet severe curly top virus (BSCTV) | SAMDC1 (S-adenosyl methionine decarboxylase) | Lowers methyl donor availability, reducing DNA and histone methylation for epigenetic silencing | Zhang et al.; 2011 |

| C4 | Tomato leaf curl Yunnan virus (TLCYnV) | DRM2 (Domain Rearranged Methyltransferase 2) | Prevents de novo cytosine methylation on viral DNA, impairing RdDM-mediated TGS | Mei et al.; 2020 |

| TrAP | TGMV, BCTV | ADK (Adenosine Kinase) | Disrupts SAM biosynthesis, interfering with methylation-mediated TGS | Jackel et al.; 2015 |

| V2 | TYLCV, Cotton leaf curl Multan virus (CLCuMuV) | AGO4 | Blocks AGO4 binding to viral DNA, inhibiting RdDM and preventing transcriptional silencing | Wang et al.; 2019 |

| Pre-coat Protein | TYLCV, ToLCNDV | MET1, RDR1, HDA6 | Suppresses maintenance methylation and chromatin silencing, compromising TGS | Basu et al.; 2018; Wang et al.; 2018 |

| C4 | CLCuMuV, ToYLCGDV | SAM synthetase, BAM1 | Reduces SAM availability and inhibits TGS; disrupts epigenetic regulation of defense genes | Ismayil et al.; 2018; Li et al.; 2020; Soto-Burgos & Bassham, 2017 |

| AC5 | MYMIV | CHH cytosine methyltransferase | Suppresses RNA-induced PTGS and reverses TGS of silenced transgenes, impairing epigenetic silencing | Li et al.; 2015 |

| βC1 | Betasatellite of TYLCCNV | SAHH (S-adenosyl homocysteine hydrolase) | Disrupts methyl cycle, suppresses methylation-dependent PTGS and RdDM-mediated TGS via calmodulin-like protein (CaM) | Yang et al.; 2011; Li et al.; 2017 |

Ethical approval

Declaration of competing interest

Author Contributions

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abo, M.E.; Sy, A.A. Rice Virus Diseases: Epidemiology and Management Strategies. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture 1997, 11, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, N.; Dasaradhi, P.V.N.; Mohmmed, A.; Malhotra, P.; Bhatnagar, R.K.; Mukherjee, S.K. RNA Interference: Biology, Mechanism, and Applications. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 2003, 67, 657–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, S.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, M.-Q. RNA Interference: Promising Approach to Combat Plant Viruses. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 5312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado-Marchena, L.; Martínez-Pérez, M.; Úbeda, J.R.; Pallas, V.; Aparicio, F. Impact of the Potential m6A Modification Sites at the 3′UTR of Alfalfa Mosaic Virus RNA3 in the Viral Infection. Viruses 2022, 14, 1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, M.; Atta, S.; Bashir, M.A.; Hussain, A.; Khan, M.I.; Farooq, S.; Hannan, A.; Islam, S.U.; Umar, U.U.D.; Khan, M.; Lin, W.; Hashem, M.; Alamri, S.; Wu, Z. Molecular characterization and RSV Co-infection of Nicotiana benthamiana with three distinct begomoviruses. Methods 2020, 183, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, S.; Kumar Kushwaha, N.; Kumar Singh, A.; Pankaj Sahu, P.; Vinoth Kumar, R.; Chakraborty, S. Dynamics of a geminivirus-encoded pre-coat protein and host RNA-dependent RNA polymerase 1 in regulating symptom recovery in tobacco. Journal of Experimental Botany 2018, 69, 2085–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baulcombe, D. RNA silencing in plants. Nature 2004, 431, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baulcombe, D.C.; Dean, C. Epigenetic Regulation in Plant Responses to the Environment. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2014, 6, a019471–a019471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blevins, T.; Podicheti, R.; Mishra, V.; Marasco, M.; Wang, J.; Rusch, D.; Tang, H.; Pikaard, C.S. Identification of Pol IV and RDR2-dependent precursors of 24 nt siRNAs guiding de novo DNA methylation in Arabidopsis. eLife 2015, 4, e09591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, F.; Martienssen, R.A. The expanding world of small RNAs in plants. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2015, 16, 727–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borges, F.; Martienssen, R.A. The expanding world of small RNAs in plants. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2015, 16, 727–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyko, A.; Kathiria, P.; Zemp, F.J.; Yao, Y.; Pogribny, I.; Kovalchuk, I. Transgenerational changes in the genome stability and methylation in pathogen-infected plants. Nucleic Acids Research 2007, 35, 1714–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterbach, P.; Verlaan, M.G.; Dullemans, A.; Lohuis, D.; Visser, R.G.F.; Bai, Y.; Kormelink, R. Tomato yellow leaf curl virus resistance by Ty-1 involves increased cytosine methylation of viral genomes and is compromised by cucumber mosaic virus infection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111, 12942–12947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, M.; Martinez, G.; Marques, M.C.; Moreno-Romero, J.; Köhler, C.; Pallas, V.; Gomez, G. Changes in the DNA methylation pattern of the host male gametophyte of viroid-infected cucumber plants. Journal of Experimental Botany 2016, 67, 5857–5868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnusamy, V.; Zhu, J.-K. Epigenetic regulation of stress responses in plants. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 2009, 12, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.; Lyons, D.B.; Kim, M.Y.; Moore, J.D.; Zilberman, D. DNA Methylation and Histone H1 Jointly Repress Transposable Elements and Aberrant Intragenic Transcripts. Molecular Cell 2020, 77, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, R.L.; Kutnjak, D.; Ambrós, S.; Bustos, M.; Elena, S.F. Identification of epigenetically regulated genes involved in plant-virus interaction and their role in virus-triggered induced resistance. BMC Plant Biology 2024, 24, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coursey, T.; Regedanz, E.; Bisaro, D.M. Arabidopsis RNA Polymerase V Mediates Enhanced Compaction and Silencing of Geminivirus and Transposon Chromatin during Host Recovery from Infection. Journal of Virology 2018, 92, e01320–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuerda-Gil, D.; Slotkin, R.K. Non-canonical RNA-directed DNA methylation. Nature Plants 2016, 2, 16163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuerda-Gil, D.; Slotkin, R.K. Non-canonical RNA-directed DNA methylation. Nature Plants 2016, 2, 16163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalakouras, A.; Ganopoulos, I. Induction of Promoter DNA Methylation Upon High-Pressure Spraying of Double-Stranded RNA in Plants. Agronomy 2021, 11, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deleris, A.; Halter, T.; Navarro, L. DNA Methylation and Demethylation in Plant Immunity. Annual Review of Phytopathology 2016, 54, 579–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deleris, A.; Halter, T.; Navarro, L. DNA Methylation and Demethylation in Plant Immunity. Annual Review of Phytopathology 2016, 54, 579–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.-W.; Voinnet, O. Antiviral Immunity Directed by Small RNAs. Cell 2007, 130, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodds, P.N.; Rathjen, J.P. Plant immunity: Towards an integrated view of plant–pathogen interactions. Nature Reviews Genetics 2010, 11, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Li, X.; Wang, C.-Z.; Xu, S.; Yuan, G.; Shao, W.; Liu, B.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, H.; Lei, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, B. Roles of the CSE1L-mediated nuclear import pathway in epigenetic silencing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowen, R.H.; Pelizzola, M.; Schmitz, R.J.; Lister, R.; Dowen, J.M.; Nery, J.R.; Dixon, J.E.; Ecker, J.R. Widespread dynamic DNA methylation in response to biotic stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubrovina, A.S.; Kiselev, K.V. Exogenous RNAs for Gene Regulation and Plant Resistance. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20, 2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sappah, A.H.; Yan, K.; Huang, Q.; Islam, Md. M.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Khan, M.S.; Zhao, X.; Mir, R.R.; Li, J.; El-Tarabily, K.A.; Abbas, M. Comprehensive Mechanism of Gene Silencing and Its Role in Plant Growth and Development. Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 12, 705249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdmann, R.M.; Picard, C.L. RNA-directed DNA Methylation. PLOS Genetics 2020, 16, e1009034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.; Qi, Y. RNAi in Plants: An Argonaute-Centered View. The Plant Cell 2016, 28, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Calvino, L.; Martínez-Priego, L.; Szabo, E.Z.; Guzmán-Benito, I.; González, I.; Canto, T.; Lakatos, L.; Llave, C. Tobacco rattle virus 16K silencing suppressor binds ARGONAUTE 4 and inhibits formation of RNA silencing complexes. Journal of General Virology 2016, 97, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Bartolomé, J. DNA methylation in plants: Mechanisms and tools for targeted manipulation. New Phytologist 2020, 227, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Bartolomé, J. DNA methylation in plants: Mechanisms and tools for targeted manipulation. New Phytologist 2020, 227, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glick, E.; Zrachya, A.; Levy, Y.; Mett, A.; Gidoni, D.; Belausov, E.; Citovsky, V.; Gafni, Y. Interaction with host SGS3 is required for suppression of RNA silencing by tomato yellow leaf curl virus V2 protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2008, 105, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Q.; Wang, Y.; Jin, Z.; Hong, Y.; Liu, Y. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of RNAi-related gene expression during plant-virus interactions. Stress Biology 2022, 2, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui, X.; Liu, C.; Qi, Y.; Zhou, X. Geminiviruses employ host DNA glycosylases to subvert DNA methylation-mediated defense. Nature Communications 2022, 13, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui, X.; Liu, C.; Qi, Y.; Zhou, X. Geminiviruses employ host DNA glycosylases to subvert DNA methylation-mediated defense. Nature Communications 2022, 13, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Reddy, K.; Bhattacharyya, D.; Chakraborty, S. Plant responses to geminivirus infection: Guardians of the plant immunity. Virology Journal 2021, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyot, V.; Rajeswaran, R.; Chu, H.C.; Karthikeyan, C.; Laboureau, N.; Galzi, S.; Mukwa, L.F.T.; Krupovic, M.; Kumar, P.L.; Iskra-Caruana, M.-L.; Pooggin, M.M. A newly emerging alphasatellite affects banana bunchy top virus replication, transcription, siRNA production and transmission by aphids. PLOS Pathogens 2022, 18, e1010448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamim, I.; Borth, W.B.; Marquez, J.; Green, J.C.; Melzer, M.J.; Hu, J.S. Transgene-mediated resistance to Papaya ringspot virus: Challenges and solutions. Phytoparasitica 2018, 46, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamim, I.; Borth, W.B.; Melzer, M.J.; Suzuki, J.Y.; Wall, M.M.; Hu, J.S. Occurrence of tomato leaf curl Bangladesh virus and associated subviral DNA molecules in papaya in Bangladesh: Molecular detection and characterization. Archives of Virology 2019, 164, 1661–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamim, I.; Borth, W.B.; Suzuki, J.Y.; Melzer, M.J.; Wall, M.M.; Hu, J.S. Molecular characterization of tomato leaf curl Joydebpur virus and tomato leaf curl New Delhi virus associated with severe leaf curl symptoms of papaya in Bangladesh. European Journal of Plant Pathology 2020, 158, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamim, I.; Green, J.C.; Borth, W.B.; Melzer, M.J.; Wang, Y.N.; Hu, J.S. First Report of Banana bunchy top virus in Heliconia spp. On Hawaii. Plant Disease 2017, 101, 2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamim, I.; Sekine, K.-T.; Komatsu, K. How do emerging long-read sequencing technologies function in transforming the plant pathology research landscape? Plant Molecular Biology 2022, 110, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley-Bowdoin, L.; Bejarano, E.R.; Robertson, D.; Mansoor, S. Geminiviruses: Masters at redirecting and reprogramming plant processes. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2013, 11, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugland, R.A.; Cline, M.G. Post-transcriptional Modifications of Oat Coleoptile Ribonucleic Acids: 5′-Terminal Capping and Methylation of Internal Nucleosides in Poly(A)-Rich RNA. European Journal of Biochemistry 1980, 104, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, H.; Ge, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, S.; Li, Z.; Zhou, X.; Li, F. m6A modification of plant virus enables host recognition by NMD factors in plants. Science China Life Sciences 2024, 67, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Jia, M.; Liu, J.; Zhou, X.; Li, F. Roles of RNA m6A modifications in plant-virus interactions. Stress Biology 2023, 3, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, H.; Jia, M.; Liu, J.; Zhou, X.; Li, F. Roles of RNA m6A modifications in plant-virus interactions. Stress Biology 2023, 3, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Cai, J.; Xu, T.; Kang, H. Epitranscriptomic mRNA modifications governing plant stress responses: Underlying mechanism and potential application. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2022, 20, 2245–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, R.; Centre, J.I. (Eds.). (2014). Plant virology (Fifth edition). Academic Press.

- Ismayil, A.; Haxim, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Qian, L.; Han, T.; Chen, T.; Jia, Q.; Yihao Liu, A.; Zhu, S.; Deng, H.; Gorovits, R.; Hong, Y.; Hanley-Bowdoin, L.; Liu, Y. Cotton Leaf Curl Multan virus C4 protein suppresses both transcriptional and post-transcriptional gene silencing by interacting with SAM synthetase. PLOS Pathogens 2018, 14, e1007282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackel, J.N.; Buchmann, R.C.; Singhal, U.; Bisaro, D.M. Analysis of Geminivirus AL2 and L2 Proteins Reveals a Novel AL2 Silencing Suppressor Activity. Journal of Virology 2015, 89, 3176–3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackel, J.N.; Buchmann, R.C.; Singhal, U.; Bisaro, D.M. Analysis of Geminivirus AL2 and L2 Proteins Reveals a Novel AL2 Silencing Suppressor Activity. Journal of Virology 2015, 89, 3176–3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, L.; Chen, M.; Xiang, M.; Guo, Z. RNAi-Based Antiviral Innate Immunity in Plants. Viruses 2022, 14, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, L.; Hamilton, A.J.; Voinnet, O.; Thomas, C.L.; Maule, A.J.; Baulcombe, D.C. RNA–DNA Interactions and DNA Methylation in Post-Transcriptional Gene Silencing. The Plant Cell 1999, 11, 2291–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Fan, T.; Wu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Shen, W.-H. Histone modification and chromatin remodeling in plant response to pathogens. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 986940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kierzek, E. The thermodynamic stability of RNA duplexes and hairpins containing N6-alkyladenosines and 2-methylthio-N6-alkyladenosines. Nucleic Acids Research 2003, 31, 4472–4480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.-H. Multifaceted Chromatin Structure and Transcription Changes in Plant Stress Response. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouzarides, T. Chromatin Modifications and Their Function. Cell 2007, 128, 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Carroll, B.J. Evolution and Diversification of Small RNA Pathways in Flowering Plants. Plant and Cell Physiology 2018. [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Xu, X.; Huang, C.; Gu, Z.; Cao, L.; Hu, T.; Ding, M.; Li, Z.; Zhou, X. The AC 5 protein encoded by Mungbean yellow mosaic India virus is a pathogenicity determinant that suppresses RNA silencing-based antiviral defenses. New Phytologist 2015, 208, 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhao, N.; Li, Z.; Xu, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, S.-S.; Wang, A.; Zhou, X. A calmodulin-like protein suppresses RNA silencing and promotes geminivirus infection by degrading SGS3 via the autophagy pathway in Nicotiana benthamiana. PLOS Pathogens 2017, 13, e1006213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Sun, Z. N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification: Emerging regulators in plant-virus interactions. Virology 2025, 603, 110373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Du, Z.; Tang, Y.; She, X.; Wang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Yu, L.; Lan, G.; He, Z. C4, the Pathogenic Determinant of Tomato Leaf Curl Guangdong Virus, May Suppress Post-transcriptional Gene Silencing by Interacting With BAM1 Protein. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 11, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Wu, X.; Fang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Bello, E.O.; Li, Y.; Xiong, R.; Li, Y.; Fu, Z.Q.; Wang, A.; Cheng, X. A plant RNA virus inhibits NPR1 sumoylation and subverts NPR1-mediated plant immunity. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucibelli, F.; Valoroso, M.C.; Aceto, S. Plant DNA Methylation: An Epigenetic Mark in Development, Environmental Interactions, and Evolution. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 8299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, L.; Moffett, P. Resistance gene Ty-1 restricts TYLCV infection in tomato by increasing RNA silencing. Virology Journal 2024, 21, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardini, M.; Kazancev, M.; Ivoilova, E.; Utkina, V.; Vlasova, A.; Demurin, Y.; Soloviev, A.; Kirov, I. Advancing virus-induced gene silencing in sunflower: Key factors of VIGS spreading and a novel simple protocol. Plant Methods 2024, 20, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez-Molins, J.; Cheng, J.; Corell-Sierra, J.; Juarez-Gonzalez, V.T.; Villalba-Bermell, P.; Annacondia, M.L.; Gomez, G.; Martinez, G. Hop stunt viroid infection induces heterochromatin reorganization. New Phytologist 2024, 243, 2351–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.; Singh, J.; Hill, J.H.; Whitham, S.A.; Cannon, S.B. Dynamic transcriptome profiling of Bean Common Mosaic Virus (BCMV) infection in Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). BMC Genomics 2016, 17, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez De Alba, A.E.; Elvira-Matelot, E.; Vaucheret, H. Gene silencing in plants: A diversity of pathways. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Regulatory Mechanisms 2013, 1829, 1300–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Pérez, M.; Aparicio, F.; López-Gresa, M.P.; Bellés, J.M.; Sánchez-Navarro, J.A.; Pallás, V. Arabidopsis m6 A demethylase activity modulates viral infection of a plant virus and the m6 A abundance in its genomic RNAs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114, 10755–10760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massart, S.; Chiumenti, M.; De Jonghe, K.; Glover, R.; Haegeman, A.; Koloniuk, I.; Komínek, P.; Kreuze, J.; Kutnjak, D.; Lotos, L.; Maclot, F.; Maliogka, V.; Maree, H.J.; Olivier, T.; Olmos, A.; Pooggin, M.M.; Reynard, J.-S.; Ruiz-García, A.B.; Safarova, D.; Candresse, T. Virus Detection by High-Throughput Sequencing of Small RNAs: Large-Scale Performance Testing of Sequence Analysis Strategies. Phytopathology® 2019, 109, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzke, M.A.; Kanno, T.; Matzke, A.J.M. RNA-Directed DNA Methylation: The Evolution of a Complex Epigenetic Pathway in Flowering Plants. Annual Review of Plant Biology 2015, 66, 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzke, M.A.; Mosher, R.A. RNA-directed DNA methylation: An epigenetic pathway of increasing complexity. Nature Reviews Genetics 2014, 15, 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzke, M.A.; Mosher, R.A. RNA-directed DNA methylation: An epigenetic pathway of increasing complexity. Nature Reviews Genetics 2014, 15, 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzke, M.; Kanno, T.; Daxinger, L.; Huettel, B.; Matzke, A.J. RNA-mediated chromatin-based silencing in plants. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 2009, 21, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzke, M.; Kanno, T.; Daxinger, L.; Huettel, B.; Matzke, A.J. RNA-mediated chromatin-based silencing in plants. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 2009, 21, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, F.; Zhou, X. The C4 protein encoded by tomato leaf curl Yunnan virus reverses transcriptional gene silencing by interacting with NbDRM2 and impairing its DNA-binding ability. PLOS Pathogens 2020, 16, e1008829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, F.; Zhou, X. The C4 protein encoded by tomato leaf curl Yunnan virus reverses transcriptional gene silencing by interacting with NbDRM2 and impairing its DNA-binding ability. PLOS Pathogens 2020, 16, e1008829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, J.L.; Welder, L. A modified nucleotide in the poly(A) tract of maize RNA. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Nucleic Acids and Protein Synthesis 1981, 652, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noris, E.; Catoni, M. (2020). Role of methylation during geminivirus infection. In Applied Plant Biotechnology for Improving Resistance to Biotic Stress (pp. 291–305). Elsevier. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9780128160305000136.

- Norouzitallab, P.; Baruah, K.; Vanrompay, D.; Bossier, P. Can epigenetics translate environmental cues into phenotypes? Science of The Total Environment 2019, 647, 1281–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordon, F.; Habekuss, A.; Kastirr, U.; Rabenstein, F.; Kühne, T. Virus Resistance in Cereals: Sources of Resistance, Genetics and Breeding. Journal of Phytopathology 2009, 157, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paprotka, T.; Deuschle, K.; Metzler, V.; Jeske, H. Conformation-Selective Methylation of Geminivirus DNA. Journal of Virology 2011, 85, 12001–12012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piedra-Aguilera, Á.; Jiao, C.; Luna, A.P.; Villanueva, F.; Dabad, M.; Esteve-Codina, A.; Díaz-Pendón, J.A.; Fei, Z.; Bejarano, E.R.; Castillo, A.G. Integrated single-base resolution maps of transcriptome, sRNAome and methylome of Tomato yellow leaf curl virus (TYLCV) in tomato. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pooggin, M. How Can Plant DNA Viruses Evade siRNA-Directed DNA Methylation and Silencing? International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2013, 14, 15233–15259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raja, P.; Sanville, B.C.; Buchmann, R.C.; Bisaro, D.M. Viral Genome Methylation as an Epigenetic Defense against Geminiviruses. Journal of Virology 2008, 82, 8997–9007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, P.; Sanville, B.C.; Buchmann, R.C.; Bisaro, D.M. Viral Genome Methylation as an Epigenetic Defense against Geminiviruses. Journal of Virology 2008, 82, 8997–9007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeevkumar, S.; Anunanthini, P.; Sathishkumar, R. Epigenetic silencing in transgenic plants. Frontiers in Plant Science 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Prado, J.S.; Abulfaraj, A.A.; Rayapuram, N.; Benhamed, M.; Hirt, H. Plant Immunity: From Signaling to Epigenetic Control of Defense. Trends in Plant Science 2018, 23, 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.-O.; Wang, Y.; Han, C.-G. Molecular Detection of Potato Viruses in Bangladesh and Their Phylogenetic Analysis. Plants 2020, 9, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Negrete, E.A.; Carrillo-Tripp, J.; Rivera-Bustamante, R.F. RNA Silencing against Geminivirus: Complementary Action of Posttranscriptional Gene Silencing and Transcriptional Gene Silencing in Host Recovery. Journal of Virology 2009, 83, 1332–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Negrete, E.; Lozano-Durán, R.; Piedra-Aguilera, A.; Cruzado, L.; Bejarano, E.R.; Castillo, A.G. Geminivirus R ep protein interferes with the plant DNA methylation machinery and suppresses transcriptional gene silencing. New Phytologist 2013, 199, 464–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Rodríguez, B.; Petek, M.; Jiao, C.; Križnik, M.; Zagorščak, M.; Fei, Z.; Bejarano, E.R.; Gruden, K.; Castillo, A.G. Transcriptional and epigenetic changes during tomato yellow leaf curl virus infection in tomato. BMC Plant Biology 2023, 23, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, P.P.; Rai, N.K.; Chakraborty, S.; Singh, M.; Chandrappa, P.H.; Ramesh, B.; Chattopadhyay, D.; Prasad, M. Tomato cultivar tolerant to Tomato leaf curl New Delhi virus infection induces virus-specific short interfering RNA accumulation and defence-associated host gene expression. Molecular Plant Pathology 2010, 11, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sastry, K.S.; Zitter, T.A. (2014). Management of Virus and Viroid Diseases of Crops in the Tropics. In K. S. Sastry & T. A. Zitter, Plant Virus and Viroid Diseases in the Tropics (pp. 149–480). Springer Netherlands. [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Miyashita, S.; Ando, S.; Takahashi, H. Increased cytosine methylation at promoter of the NB-LRR class R gene RCY1 correlated with compromised resistance to cucumber mosaic virus in EMS-generated src mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology 2017, 100, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secco, N.; Sheikh, A.H.; Hirt, H. Insights into the role of N6-methyladenosine (m6A) in plant-virus interactions. Journal of Virology 2025, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Q.; Liu, Z.; Song, F.; Xie, Q.; Hanley-Bowdoin, L.; Zhou, X. Tomato SlSnRK1 Protein Interacts with and Phosphorylates βC1, a Pathogenesis Protein Encoded by a Geminivirus β-Satellite. Plant Physiology 2011, 157, 1394–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Bobay, B.G.; Greeley, L.A.; Reyes, M.I.; Rajabu, C.A.; Blackburn, R.K.; Dallas, M.B.; Goshe, M.B.; Ascencio-Ibáñez, J.T.; Hanley-Bowdoin, L. Sucrose Nonfermenting 1-Related Protein Kinase 1 Phosphorylates a Geminivirus Rep Protein to Impair Viral Replication and Infection. Plant Physiology 2018, 178, 372–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, W.; Dallas, M.B.; Goshe, M.B.; Hanley-Bowdoin, L. SnRK1 Phosphorylation of AL2 Delays Cabbage Leaf Curl Virus Infection in Arabidopsis. Journal of Virology 2014, 88, 10598–10612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinde, H.; Dudhate, A.; Kadam, U.S.; Hong, J.C. RNA methylation in plants: An overview. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14, 1132959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, J.; Mishra, V.; Wang, F.; Huang, H.-Y.; Pikaard, C.S. Reaction Mechanisms of Pol IV, RDR2, and DCL3 Drive RNA Channeling in the siRNA-Directed DNA Methylation Pathway. Molecular Cell 2019, 75, 576–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Burgos, J.; Bassham, D.C. SnRK1 activates autophagy via the TOR signaling pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0182591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stael, S.; Kmiecik, P.; Willems, P.; Van Der Kelen, K.; Coll, N.S.; Teige, M.; Van Breusegem, F. Plant innate immunity – sunny side up? Trends in Plant Science 2015, 20, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroud, H.; Greenberg, M.V.C.; Feng, S.; Bernatavichute, Y.V.; Jacobsen, S.E. Comprehensive Analysis of Silencing Mutants Reveals Complex Regulation of the Arabidopsis Methylome. Cell 2013, 152, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Yan, F.; Hahn, M.; Ma, Z. Regulatory roles of epigenetic modifications in plant-phytopathogen interactions. Crop Health 2023, 1, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, M.; Paszkowski, J. DNA and histone methylation in plants. Trends in Genetics 2004, 20, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatineni, S.; Hein, G.L. Plant Viruses of Agricultural Importance: Current and Future Perspectives of Virus Disease Management Strategies. Phytopathology® 2023, 113, 117–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S.; Bau, H.; Chen, L.; Yeh, S. The ability of Papaya ringspot virusstrains overcoming the transgenic resistance of papaya conferred by the coat protein gene is not correlated with higher degrees of sequence divergence from the transgene. European Journal of Plant Pathology 2004, 110, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatanparast, M.; Merkel, L.; Amari, K. Exogenous Application of dsRNA in Plant Protection: Efficiency, Safety Concerns and Risk Assessment. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 6530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veluthambi, K.; Sunitha, S. Targets and Mechanisms of Geminivirus Silencing Suppressor Protein AC2. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 12, 645419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veluthambi, K.; Sunitha, S. Targets and Mechanisms of Geminivirus Silencing Suppressor Protein AC2. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 12, 645419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voinnet, O. Use, tolerance and avoidance of amplified RNA silencing by plants. Trends in Plant Science 2008, 13, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wale, S.; Platt, B.; D. Cattlin, N. Diseases, Pests and Disorders of Potatoes: A Colour Handbook (0 ed.). CRC Press. [CrossRef]

- Wambui Mbichi, R.; Wang, Q.-F.; Wan, T. (2020). RNA directed DNA methylation and seed plant genome evolution. Plant Cell Reports 2008, 39, 983–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Zhou, X. Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus V2 Interacts with Host Histone Deacetylase 6 To Suppress Methylation-Mediated Transcriptional Gene Silencing in Plants. Journal of Virology 2018, 92, e00036–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, C.; Zou, J.; Yang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhu, S. Epigenetics in the plant–virus interaction. Plant Cell Reports 2019, 38, 1031–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Hao, L.; Shung, C.-Y.; Sunter, G.; Bisaro, D.M. Adenosine Kinase Is Inactivated by Geminivirus AL2 and L2 Proteins. The Plant Cell 2003, 15, 3020–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Gong, Q.; Ismayil, A.; Yuan, Y.; Lian, B.; Jia, Q.; Han, M.; Deng, H.; Hong, Y.; Hanley-Bowdoin, L.; Qi, Y.; Liu, Y. Geminiviral V2 Protein Suppresses Transcriptional Gene Silencing through Interaction with AGO4. Journal of Virology 2019, 93, e01675–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, P.M.; Wang, M.-B.; Lough, T. Gene silencing as an adaptive defence against viruses. Nature 2001, 411, 834–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierzbicki, A.T.; Ream, T.S.; Haag, J.R.; Pikaard, C.S. RNA polymerase V transcription guides ARGONAUTE4 to chromatin. Nature Genetics 2009, 41, 630–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Luo, Y.; Lu, R.; Lau, N.; Lai, E.C.; Li, W.-X.; Ding, S.-W. Virus discovery by deep sequencing and assembly of virus-derived small silencing RNAs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2010, 107, 1606–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Fan, G. The role of epigenetics in plant pathogens interactions under the changing environments: A systematic review. Plant Stress 2025, 15, 100753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.-S.; Duan, C.-G. Epigenetic regulation of plant immunity: From chromatin codes to plant disease resistance. aBIOTECH 2023, 4, 124–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.-S.; Duan, C.-G. Epigenetic regulation of plant immunity: From chromatin codes to plant disease resistance. aBIOTECH 2023, 4, 124–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Liu, Y.; Wu, P.; Bian, Z.; Li, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, B. Identification and virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) analysis of methyltransferase affecting tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) fruit ripening. Planta 2024, 259, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.-L.; Zhang, G.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Xu, D.; Di, C.; Tang, K.; Yang, L.; Zeng, L.; Miki, D.; Duan, C.-G.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, J.-K. Four putative SWI2/SNF2 chromatin remodelers have dual roles in regulating DNA methylation in Arabidopsis. Cell Discovery 2018, 4, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Fang, Y.; An, C.; Dong, L.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, H.; Xie, Q.; Guo, H. C 2-mediated decrease in DNA methylation, accumulation of si RNA s, and increase in expression for genes involved in defense pathways in plants infected with beet severe curly top virus. The Plant Journal 2013, 73, 910–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Lang, C.; Wu, Y.; Meng, D.; Yang, T.; Li, D.; Jin, T.; Zhou, X. ROS1-mediated decrease in DNA methylation and increase in expression of defense genes and stress response genes in Arabidopsis thaliana due to abiotic stresses. BMC Plant Biology 2022, 22, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Xie, Y.; Raja, P.; Li, S.; Wolf, J.N.; Shen, Q.; Bisaro, D.M.; Zhou, X. Suppression of Methylation-Mediated Transcriptional Gene Silencing by βC1-SAHH Protein Interaction during Geminivirus-Betasatellite Infection. PLoS Pathogens 2011, 7, e1002329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.; Wei, Y.; Zhao, M. The Reversible Methylation of m6A Is Involved in Plant Virus Infection. Biology 2022, 11, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbini, F.M.; Briddon, R.W.; Idris, A.; Martin, D.P.; Moriones, E.; Navas-Castillo, J.; Rivera-Bustamante, R.; Roumagnac, P.; Varsani, A.; ICTV Report Consortium. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Geminiviridae. Journal of General Virology 2017, 98, 131–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Lang, Z.; Zhu, J.-K. Dynamics and function of DNA methylation in plants. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2018, 19, 489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Yazaki, J.; Sundaresan, A.; Cokus, S.; Chan, S.W.-L.; Chen, H.; Henderson, I.R.; Shinn, P.; Pellegrini, M.; Jacobsen, S.E.; Ecker, J.R. Genome-wide High-Resolution Mapping and Functional Analysis of DNA Methylation in Arabidopsis. Cell 2006, 126, 1189–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, H.; Huang, X.; Xia, R.; Zhao, Q.; Lai, J.; Teng, K.; Li, Y.; Liang, L.; Du, Q.; Zhou, X.; Guo, H.; Xie, Q. BSCTV C2 Attenuates the Degradation of SAMDC1 to Suppress DNA Methylation-Mediated Gene Silencing in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 2011, 23, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.-H.; Liu, X.-L.; Fang, Y.-Y.; Fang, R.-X.; Guo, H.-S. CMV2b-Dependent Regulation of Host Defense Pathways in the Context of Viral Infection. Viruses 2018, 10, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, P.; Chang, C. Exploiting Epigenetic Variations for Crop Disease Resistance Improvement. Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 12, 692328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.-H.; Shan, W.-X.; Ayliffe, M.A.; Wang, M.-B. Epigenetic Mechanisms: An Emerging Player in Plant-Microbe Interactions. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions® 2016, 29, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, S.; Farooq, M.A.; Zhao, T.; Wang, P.; Tabusam, J.; Wang, Y.; Xuan, S.; Zhao, J.; Chen, X.; Shen, S.; Gu, A. Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS): A Powerful Tool for Crop Improvement and Its Advancement towards Epigenetics. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 5608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region/Country | Crop (s) | Estimated Loss (USD, approx.) | Causative Virus | Reference (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa/South Asia | Cassava | 1.9-2.7 billion | Cassava mosaic begomoviruses | Tatineni & Hein, 2023 |

| USA | Potato | 100-120 million | Potato leafroll Polerovirus | Sastry & Zitter, 2014; Wale et al.; 2008 |

| United Kingdom (UK) | Cereals (Barley,Oats,Rice,Wheat,Maize) | 10-15 million | Barley yellow dwarf virus | Ordon et al.; 2009 |

| South-East Asia | Rice | ~1.0 billion | Rice tungro viruses | Abo & Sy, 1997; Hull & Centre, 2014 |

| USA, Australia, Eastern Europe | Tomato, Lettuce, Eggplant, Pepper | 1.0-1.5 billion | Tomato spotted wilt virus | Tatineni & Hein, 2023 |

| Bangladesh | Potato | 0.5-1.8 billion | Potato leafroll virus, Potato virus X, Potato virus Y, Potato virus S, Potato virus H, Potato aucuba mosaic virus and Potato virus M | Rashid et al.; 2020 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).