1. Introduction

Hydrothermal fluid migration and subsequent alteration of Paleozoic age strata are an important part of the complex diagenetic history on the North American Midcontinent. The fluid sources and drivers are mainly related to tectonic (Marathon-Ouachita, Ancestral Rocky Mountains, Sevier, and Laramide orogenies), and non-tectonic drivers (post-orogenic hydrothermal fluid flow) [

1,

2]. The results presented here align with those reported in previous studies in Kansas as well as Oklahoma and Missouri [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. For the purposes of this study, hydrothermal fluid refers to fluid interpreted to be at temperature exceeding ambient burial temperature of the surrounding host rock (Machel and Lonnee, 2002) [

13].

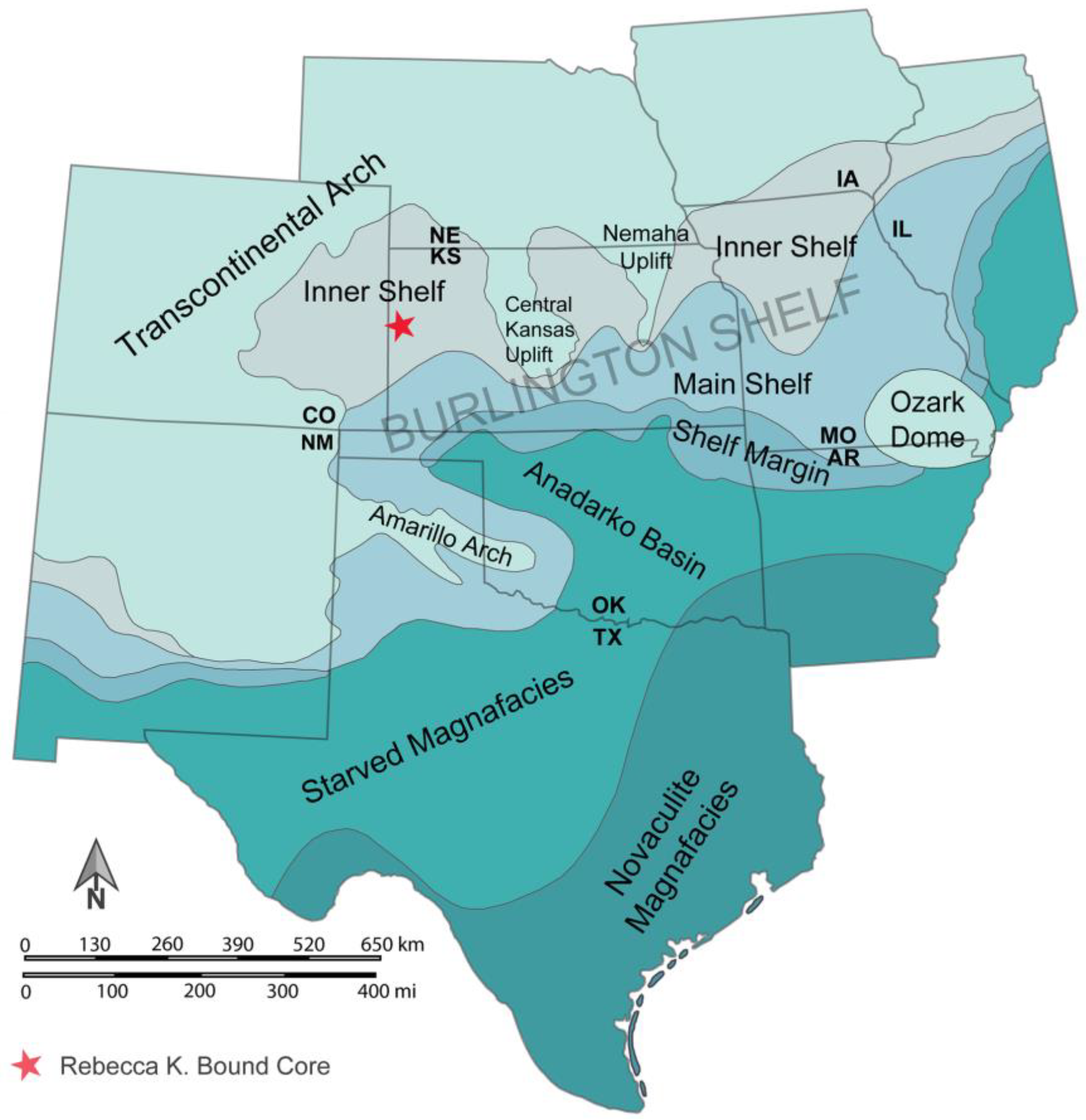

This study specifically investigates vug, fracture, channel, and breccia filling carbonate cements in Mississippian (Osagian) limestone in the Rebecca K. Bounds (RKB) core (API: 15-071-20446), Greeley County, Kansas (

Figure 1), which is located in a complex geologic setting. The research helps in understanding of the late-stage diagenetic history of the Mississippian strata of the western High Plains (west Kansas). This study builds on new data and previous comprehensive studies that examined Paleozoic rocks in south-central and eastern Kansas. Mississippian rocks of the midcontinent not only have produced significant oil and gas [

14] but also host economically important metals such as lead, zinc, and copper as well as other critical minerals in the Tri-State Mississippi valley-type (MVT) mineral district (Missouri-Oklahoma, and Kansas) [

15]. Data collected for this study are compared with the data collected in the underlying Arbuckle Group (Lower Ordovician) as observed in the nearby Patterson core (

Figure 1) [

16].

The questions that are addressed in this research are: (a) what are the origins and pathways of the hydrothermal fluids responsible for late diagenetic cementation in the Mississippian of western Kansas, (b) what is the relative and absolute timing of fluid flow and cementation, (c) what is the likelihood of economic MVT sulfide mineralization associated with these late diagenetic fluids To address these problems several methods are applied including thin section petrography, cathodoluminescence (CL) petrography, isotope geochemistry, and fluid inclusion microthermometry.

2. Geological Setting

2.1. Stratigraphy

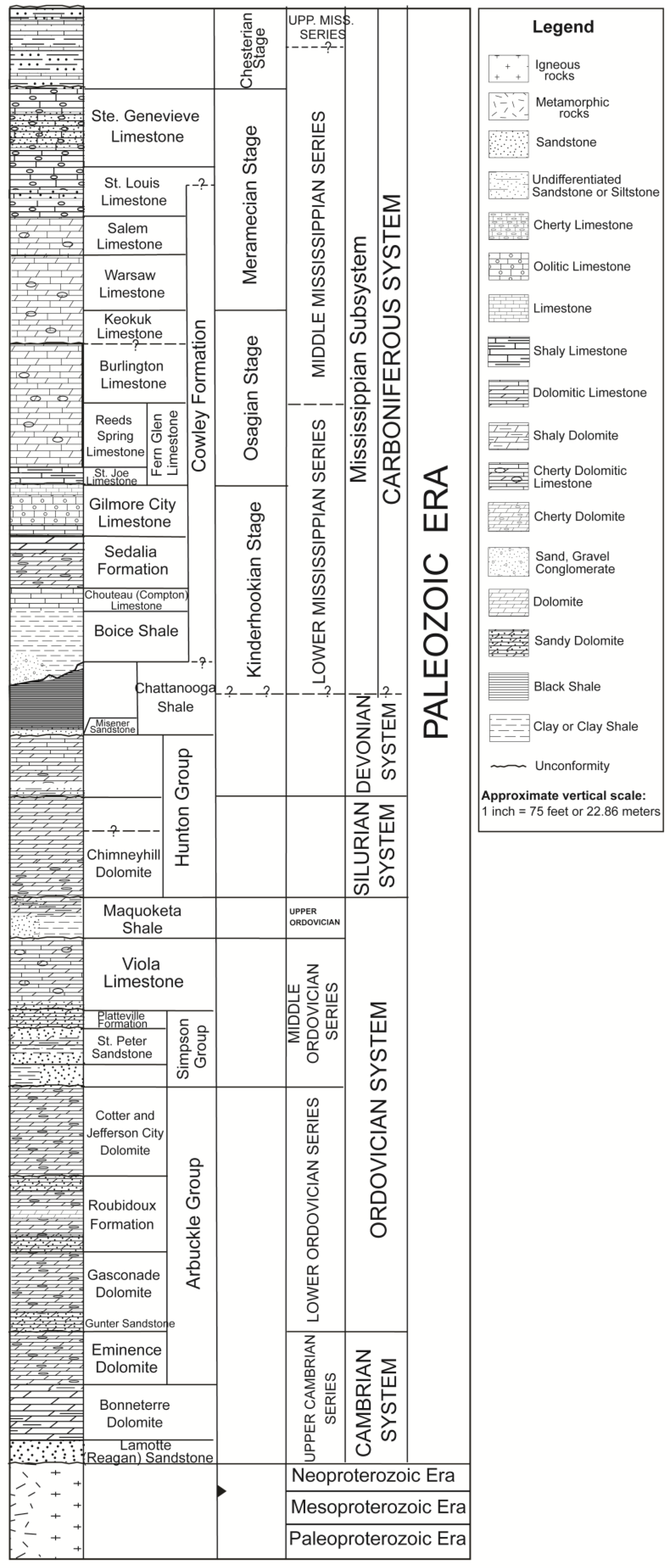

Precambrian erosion shaped a highly irregular surface across the region. On this uneven topography, Cambrian-Ordovician strata, including the Arbuckle Group, were deposited [

17]. The Arbuckle Group (

Figure 3) is mainly composed of carbonate rocks in Kansas; however, it is absent in northeastern and northwestern Kansas [

17,

18]. The thickness of the Arbuckle in Kansas increases from north to south up to 423.67 m (1,390 ft) [

19]. By the end of the Early Ordovician, a major sea-level drop exposed the mid-continent. This resulted in intense weathering and erosion, forming a regional unconformity overlying the carbonate platforms [

20]. The Middle Ordovician section in Kansas includes the Simpson Group and Viola limestone consisting of sandstone, shale and carbonates [

21,

22]. In the Hugoton embayment the Simpson becomes thinner toward the north and west [

22]. The Viola limestone is absent on uplifts and arches but thickens to over 60.96 m (200 ft) near the Oklahoma border [

22]. Upper Ordovician rocks include the Maquoketa Shale, which is mostly confined to the northern Kansas basin It is up to 47.24 m (155 ft) thick in the northeast and thins less than 12.19 m (40 ft) southward, but absent in the southwest of Kansas [

22].

In central Kansas the Silurian and Devonian intervals include the Hunton limestone and overlying Misener Sandstone (

Figure 3). Silurian strata dominate the intervals while the Devonian sequence is more restricted toward northeast [

23]. The Hunton Group consist of dolomitic limestone with interbedded chert becoming thinner toward the southwest due to both overlap and erosion. The Misener is a thin sandstone that includes shale and limestone, and was likely deposited on an irregular surface shaped by erosion before Mississippian deposition [

23].

The Mississippian Subsystem include rocks deposited approximately 359 to 323 million years ago throughout Kansas. During the Mississippian Subperiod, Kansas was located in low latitudes and covered by a shallow tropical to subtropical epeiric sea [

24,

25] (

Figure 2). These rocks are exposed at the surface only in the southeastern part of the state [

14]. From east to west, Mississippian rocks lie deeper in the subsurface, reaching depths of more than a thousand meters in central and western Kansas [

14]. Structural highs of the Central Kansas and Nemaha uplifts are largely missing Mississippian rocks due to erosion, but hydrocarbon production is common on their flanks [

14]. Mississippian rocks are also thinned or absent over anticlines and thickened in synclines and basins [

14].

During deposition, Kansas was located near 20° south latitude in a tropical to subtropical belt [

14,

25]. Repeated sea level changes led to alternating layers of partially silicified marine mudstones, skeletal wackestones, packstones and grainstones [

14]. By the end of the period, only the southern region remained submerged. In south-central Kansas, limestone underwent weathering and dissolution during low sea levels, leaving behind a porous chert-rich zone (

Figure 1). Mississippian rocks in Kansas are unconformably overlain by Pennsylvanian cyclothems, including basal conglomerates, shales, sandstones, and minor carbonates. This contact is marked by truncation, erosion, and the development of a cherty zone, which grades upward into Pennsylvanian deposits [

14].

2.2. Structure

The local structural geology is affected by regional tectonics. The 1.1Ga Midcontinent Rift System runs from south to southwest Kansas and it is parallel to the Nemaha Uplift on the east Humboldt fault zone [

26,

27]. The Nemaha uplift itself is a series of transpressional structures, extending from southeastern Nebraska through eastern Kansas into north-central Oklahoma [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. A series of northwest-southeast trending faults in west-central Kansas, form the structurally elevated Central Kansas uplift [

27].

Additional tectonic influence is exerted by the Late Paleozoic formation of the Southern Oklahoma Aulacogen to the south [

32,

33]. Similarly, the local structure in Western Kansas is affected by the Pennsylvanian formation of the Anadarko Basin, a foreland “super basin” to uplifts in the Southern Oklahoma Aulacogen (Amarillo Arch), with southward migrating depocenters, and a southern fold-thrust belt which trends NW-SE [

34,

35,

36]. The Anadarko basin sediments thin to the NW into the Hugoton Embayment, which contains NW striking normal faults that downthrow to the SW [

37,

38]. Lastly, the study area is affected by Mesozoic and Cenozoic tectonics of the Laramide Orogeny to the west [

39].

Figure 2.

Regional map of shelf deposits in early Mississippian age, modified from Lane and Dekyser [

40].

Figure 2.

Regional map of shelf deposits in early Mississippian age, modified from Lane and Dekyser [

40].

Figure 3.

Stratigraphic column of Kansas, modified from Zeller [

41].

Figure 3.

Stratigraphic column of Kansas, modified from Zeller [

41].

3. Methods

The RKB subsurface core, Greeley Co, Kansas, studied here spans depths of 487.68 m to 1036.32 m (1600 ft to 3400 ft) [

42]. The targeted interval analyzed for this study is from Mississippian (Osagian), between 1659.63 m to 1686.76 m (5,445 ft to 5,534 ft) [

16] (

Figure 1). Petrographic studies were conducted using an Olympus-BX53 microscope. Cathodoluminescence (CL) imaging was conducted using a cold cathode CITL MK5-1 apparatus mounted on an Olympus-BX51 microscope equipped with 4X and 10X long focal distance objective lenses, and a low-light, digital camera system. Limestone fabrics and textures are classified according to Dunham [

43] and dolomite according to Sibley and Gregg [

44]. Porosity types are described according to the classification of Choquette and Pray [

45]. Fluid inclusion (FI) microthermometry was conducted using a U.S. Geological Survey gas-flow heating/freezing stage to obtain homogenization temperature (T

h) and salinity of fluids included in calcite and dolomite cements. No pressure corrections were made on T

h values, thus these represent minimum trapping temperatures and not filling temperatures of the included fluids. Ultraviolet (UV) epifluorescence petrography was used to assess the existence of petroleum inclusions. Fluid inclusion assemblages (FIA) were identified using the criteria of Goldstein & Reynolds [

46]. Salinity, in weight % NaCl equivalent (eq), of included fluids were calculated from final melting temperature (T

mice) using the Bodnar equation [

47]. Carbon and oxygen, (δ

13C, δ

18O), isotope analyses were obtained on calcite and dolomite samples at the W. M. Keck Paleoenvironmental and Environmental Stable Isotope Laboratory at the University of Kansas using an isotope ratio mass spectrometer. All C and O isotope values are expressed relative to the VPDB standard and have standard errors less than ±0.05‰. Calculations for calcite-water and dolomite-water fractionation (δ

18O

water) were made by using O’Neil et al. [

48] and Friedman and O’Neil [

40] fractionation equations [

50]. Radiogenic strontium (Sr) isotope ratios (

87Sr/

86Sr) were determined using a thermal ionization mass spectrometer also at the University of Kansas.

4. Results

4.1. Petrography

Examples of the RKB core, described for this study are shown in

Figure 4a. The core study focused on targeted intervals containing late-stage carbonate cements, including calcites and dolomites filling vugs, channels, fractures, and breccias (

Figure 4b). The targeted intervals span the Osagian stage (Mississippian), from the top at 1659.9 m (5,446 ft) to its base at 1685.5 m (5,530 ft).

Host limestone in the core interval studied here include bioturbated mudstone-wackestone, echinoderm-rich packstone-grainstone, and bryozoan-rich wackestone-packstone to grainstone. Skeletal fragments include primarily crinoids with lesser amounts of bryozoans, bivalves, and ostricods for full petrographic descriptions of the limestones see Mohammadi et al. [

16]. Other features were observed, including chert replaced burrows, cross bedding, and abraded clasts, indicating variable energy conditions such as deposition in a shallow subtidal marine setting ranging from low to high energy (

Figure 4). Crinoidal grainstones are characterized by syntaxial calcite cement filling intergrain and small vug porosity (

Figure 5a,b). Syntaxial and other early diagenetic calcite cements in Mississippian limestones on the Midcontinent are discussed by Mohammadi et al. [

9]. Additionally, very fine planar dolomite crystals frequently replace mudstone (

Figure 5 a,b). The origin of similar Mississippian replacement dolomite is discussed by Mohammadi et al. [

10].

Occasionally skeletal fragments are partially or completely replaced by chert and occasionally contain authigenic quartz filling intraparticle porosity (

Figure 5c). Fractures and channels frequently are filled by chert, authigenic quartz, and calcite cements (

Figure 5d,e). Type 1b stylolites, solution seams, and fitted fabrics [

51] (

Figure 5e) are observed throughout the limestone in the cored section and are observed to cross-cut chert and calcite filled fractures, channels (

Figure 5e) and breccias.

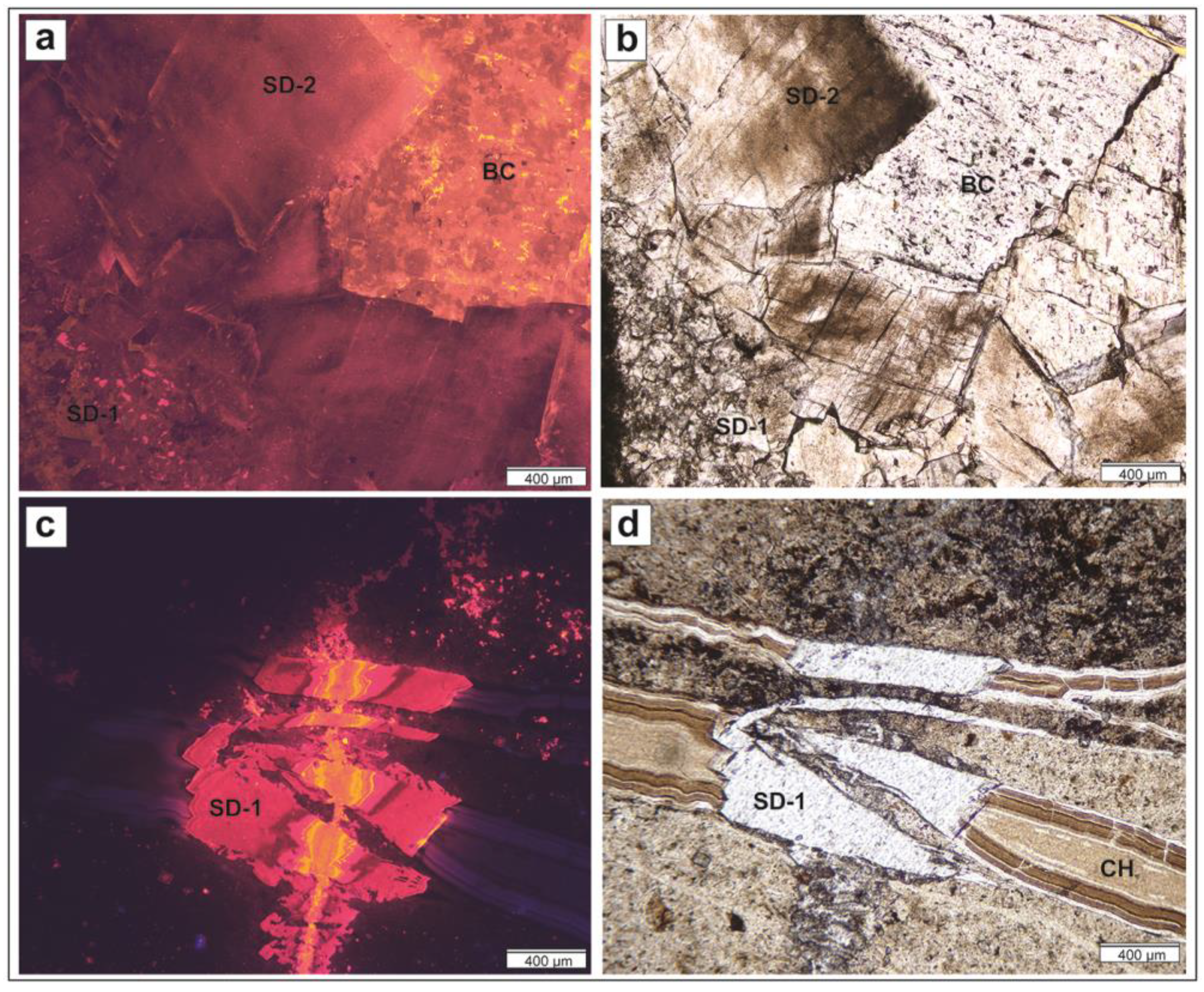

Three different generations of dolomite are identified, associated with large vugs (

Figure 4b), fractures, channels (

Figure 4b;

Figure 5c), and breccias (

Figure 5f). These include: (1) Medium to coarse crystalline planar dolomite replacing host limestone (

Figure 5f). This dolomite is not to be confused with finer crystalline dolomite replacing mudstone that is described above. (2) 1st stage saddle dolomite exhibiting bright-red to dull compositional zonation under CL. And (3) 2nd stage saddle dolomite displaying several diffuse dull to dark red zones under CL (

Figure 6a). Saddle dolomite cement is followed paragenetically by blocky calcite cement displaying bright orange to orange-yellow CL and lacking zonation (

Figure 6). Fractures and channels filled by 1st stage saddle dolomite cement occasionally cross-cut fractures and channels filled by chert and authigenic quartz (

Figure 5d and

Figure 6c,d).

4.2. Fluid Inclusions

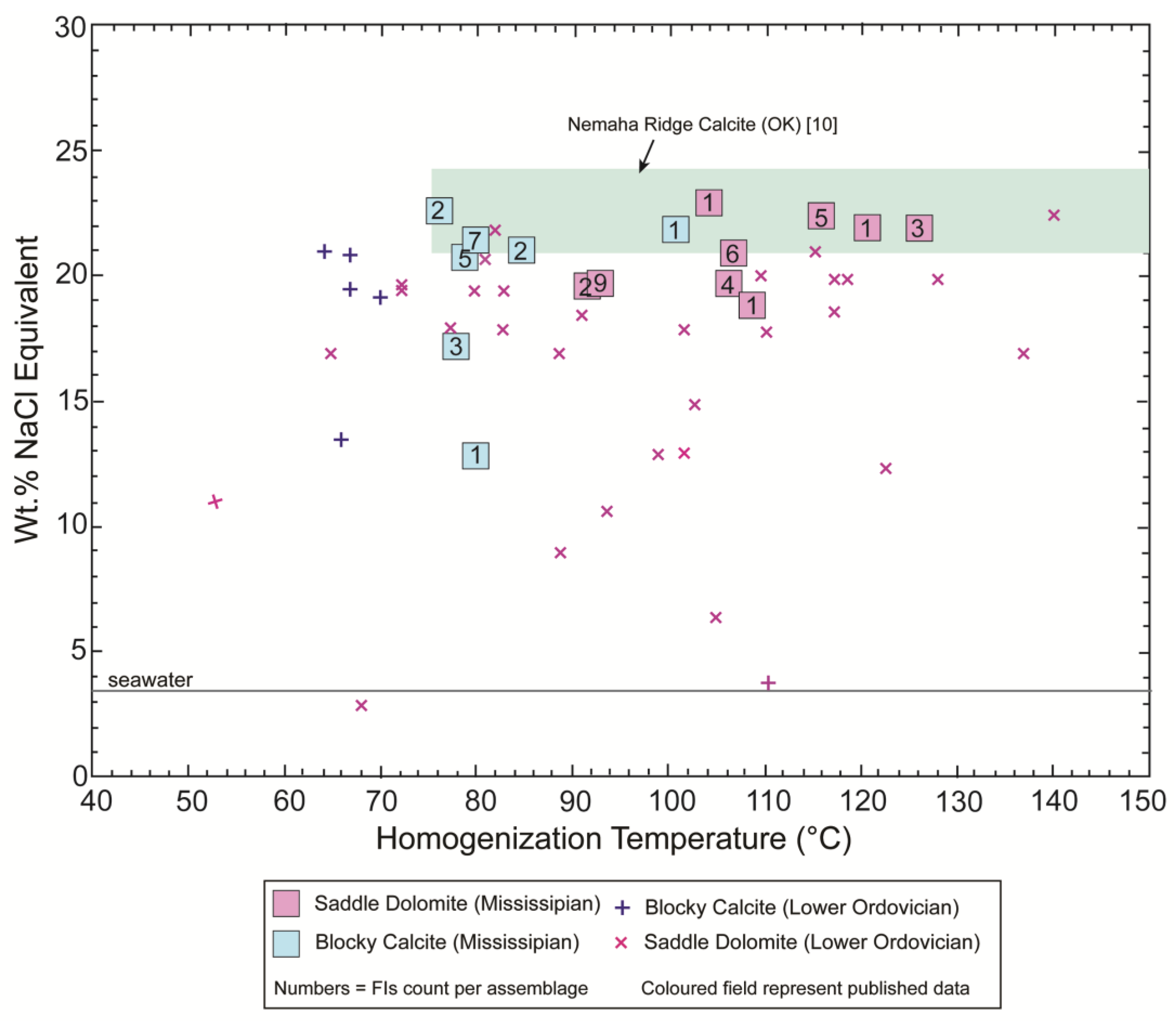

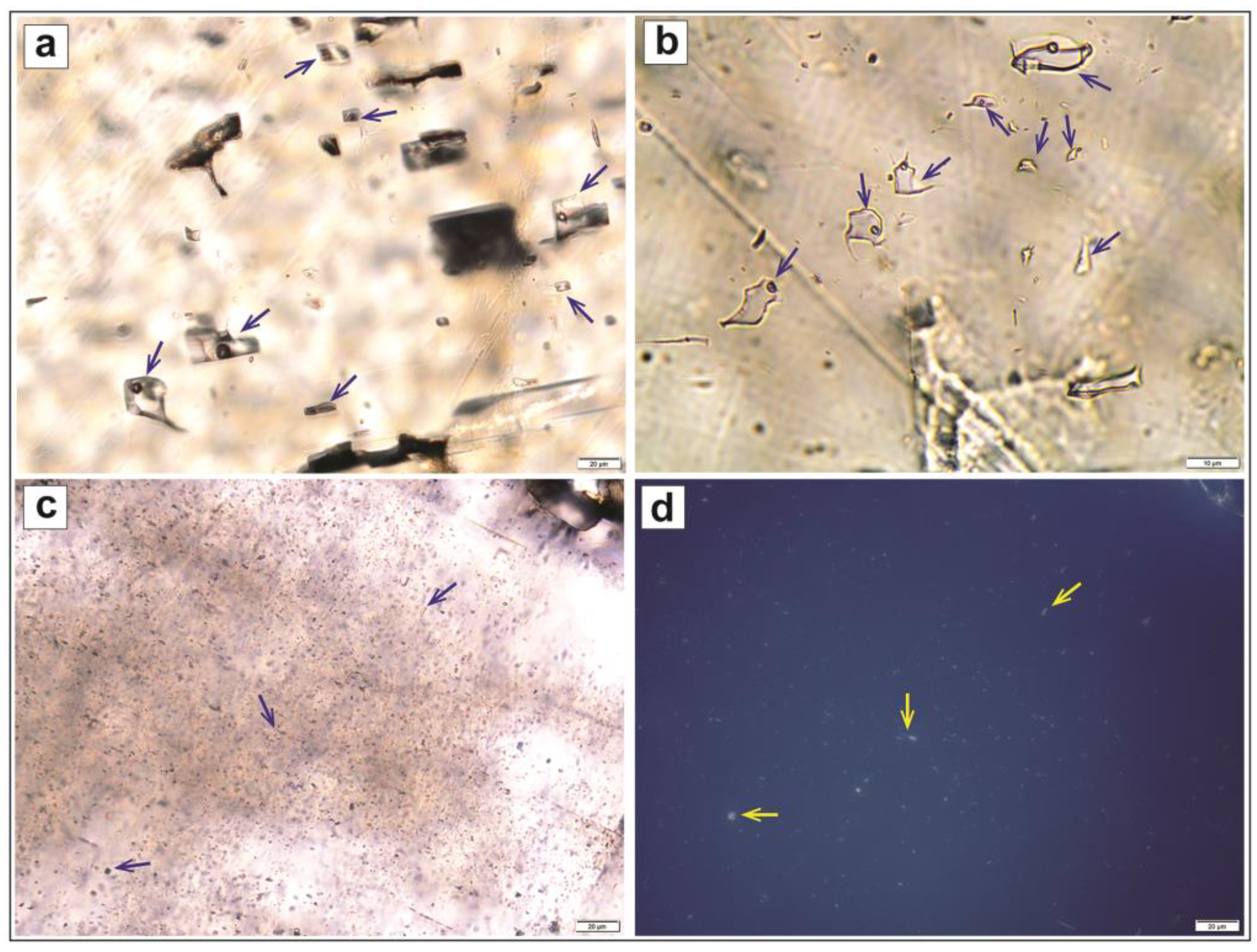

One and two phase (liquid and vapor) fluid inclusions were observed in 2nd stage saddle dolomite and calcite cements filling vugs, fractures, channels, and breccia in the core intervals studied (

Figure 7). In addition, one phase secondary liquid petroleum (oil) inclusions were observed in 2nd stage saddle dolomite cement under UV epifluorescence (

Figure 7c,d). Homogenization temperature (T

h) (minimum trapping temperature) and last ice melting temperature (T

mice) were measured from primary inclusions in carbonate cements in the RKB core samples (

Table 1). Saddle dolomite cements (2nd stage) have T

h assemblages value ranging from 65 to 126°C and salinity ranging from 18.4 to 23 wt. % NaCl eq. Fluid inclusions in calcite cements display T

h assemblage value that range from 67 to 101°C and salinity from 13.2 to 22.4 wt. % NaCl eq (

Table 1). Some of 2nd stage saddle dolomite assemblage values slightly overlap with calcite cement, however, they typically have higher T

h values than calcite. These T

h values are similar to those measured in saddle dolomites in the underlying Arbuckle Group (Lower Ordovician) in the Patterson core [

16]. However, calcite temperatures observed in the Arbuckle section in the underlying Patterson core have lower T

h values than calcites in the overlying Mississippian rocks. Possible primary and secondary oil inclusion were also observed in blocky calcite cements.

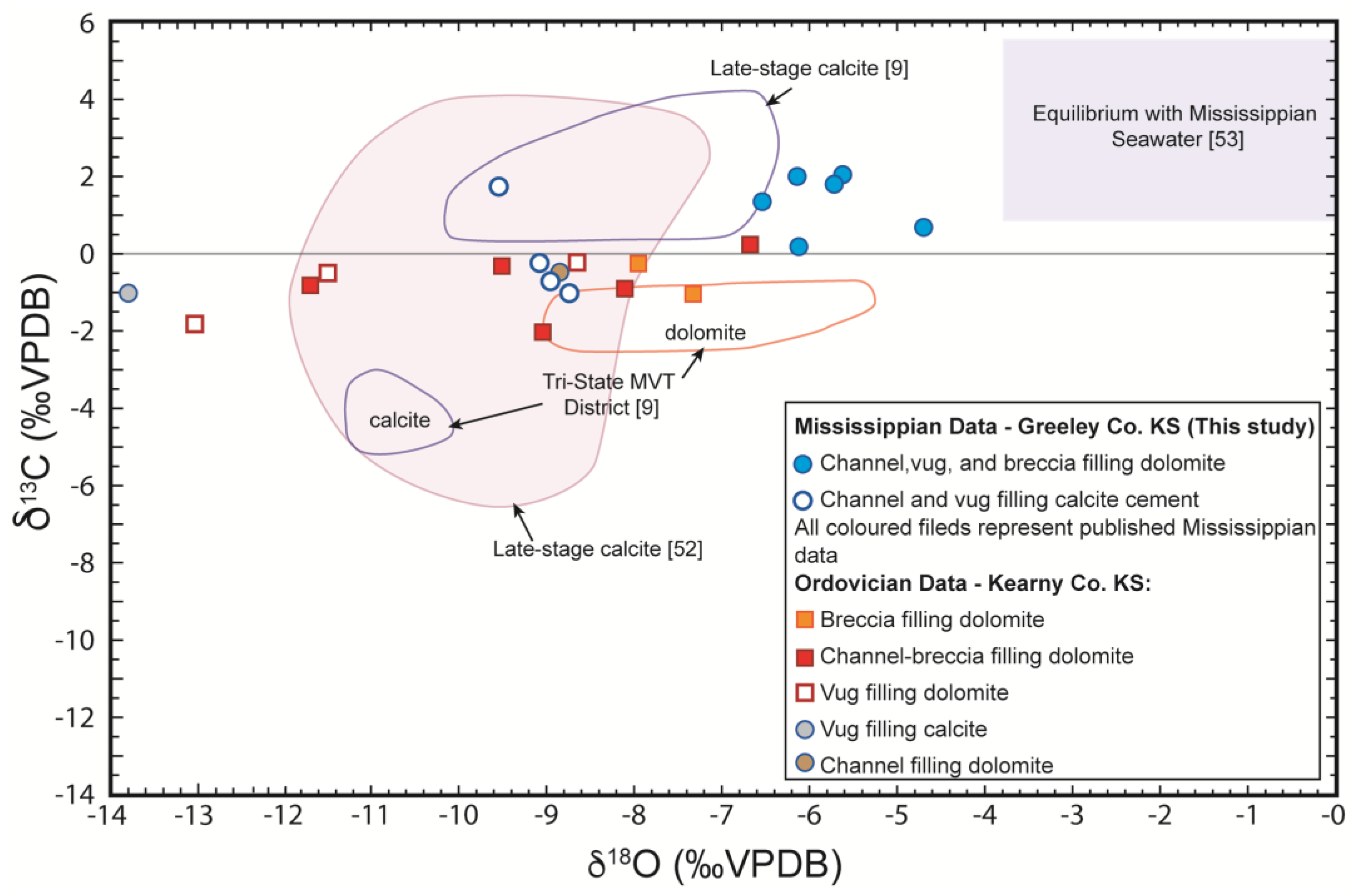

4.3. Isotope Geochemistry

Stable δ

18O and δ

13C isotope analyses were obtained on dolomite and calcite cements filling vugs, channels, and breccias in the RKB core. Most of the saddle dolomite used for isotope analysis probably were 2nd stage as it is volumetrically more common, in the large vugs, channels, and breccias that were sampled, than 1st stage saddle dolomite. Saddle dolomite cements have δ

18O and δ

13C ranges from -6.44 to -4.66

‰ and 0.15 to 2.08

‰, respectively. Ranges for δ

18O and δ

13C in calcite cements were -9.44 to -8.69

‰ and -1.01 to 1.79‰, respectively (

Table 2,

Figure 9). These values display a similar trend as observed in the underlying Patterson core in the Arbuckle [

16] and Mississippian calcite cements studied by Ritter and Goldstein [

52] (

Figure 9).

Figure 8.

Fluid inclusion data for the RKB core (Greeley County Kansas) and the Arbuckle Patterson core (Kearny County Kansas. Homogenization temperatures (T

h) are plotted against weight percent NaCl equivalent calculated [

47] from last ice melting temperatures (T

mice).

Figure 8.

Fluid inclusion data for the RKB core (Greeley County Kansas) and the Arbuckle Patterson core (Kearny County Kansas. Homogenization temperatures (T

h) are plotted against weight percent NaCl equivalent calculated [

47] from last ice melting temperatures (T

mice).

Figure 9.

Stable δ

18O and δ

13C isotope data for carbonate cements from the RKB core and the Patterson Arbuckle core (Kearny County) modified from Mohammadi et al. [

16]. Previous published data are shown as fields [

9,

52,

53].

Figure 9.

Stable δ

18O and δ

13C isotope data for carbonate cements from the RKB core and the Patterson Arbuckle core (Kearny County) modified from Mohammadi et al. [

16]. Previous published data are shown as fields [

9,

52,

53].

Figure 10.

Strontium and oxygen isotope plot for the RKB core and the Patterson Arbuckle Core (Kearny County), modified from Mohammadi et al. [

16]. The fields are from previously published studies [

9,

10,

53].

Figure 10.

Strontium and oxygen isotope plot for the RKB core and the Patterson Arbuckle Core (Kearny County), modified from Mohammadi et al. [

16]. The fields are from previously published studies [

9,

10,

53].

Radiogenic Sr ratios (

87Sr/

86Sr) for channel, vug, and breccia filling saddle dolomite range from 0.7088812 to 0.7094432 and for calcite range from 0.7089503 to 0.7111501 (

Table 3,

Figure 10). Mississippian Sr values measured for this study are largely less radiogenic compared to the values observed in underlying Arbuckle rocks in the Patterson core [

16]. In addition, Mississippian values in this study overlap the Mississippian values measured by Mohammadi et al. [

9,

10] in the Mississippian section on the Ozark-Cherokee Platform and north-central Oklahoma.

5. Discussion

5.1. Paragenesis in the Mississippian of Western Kansas

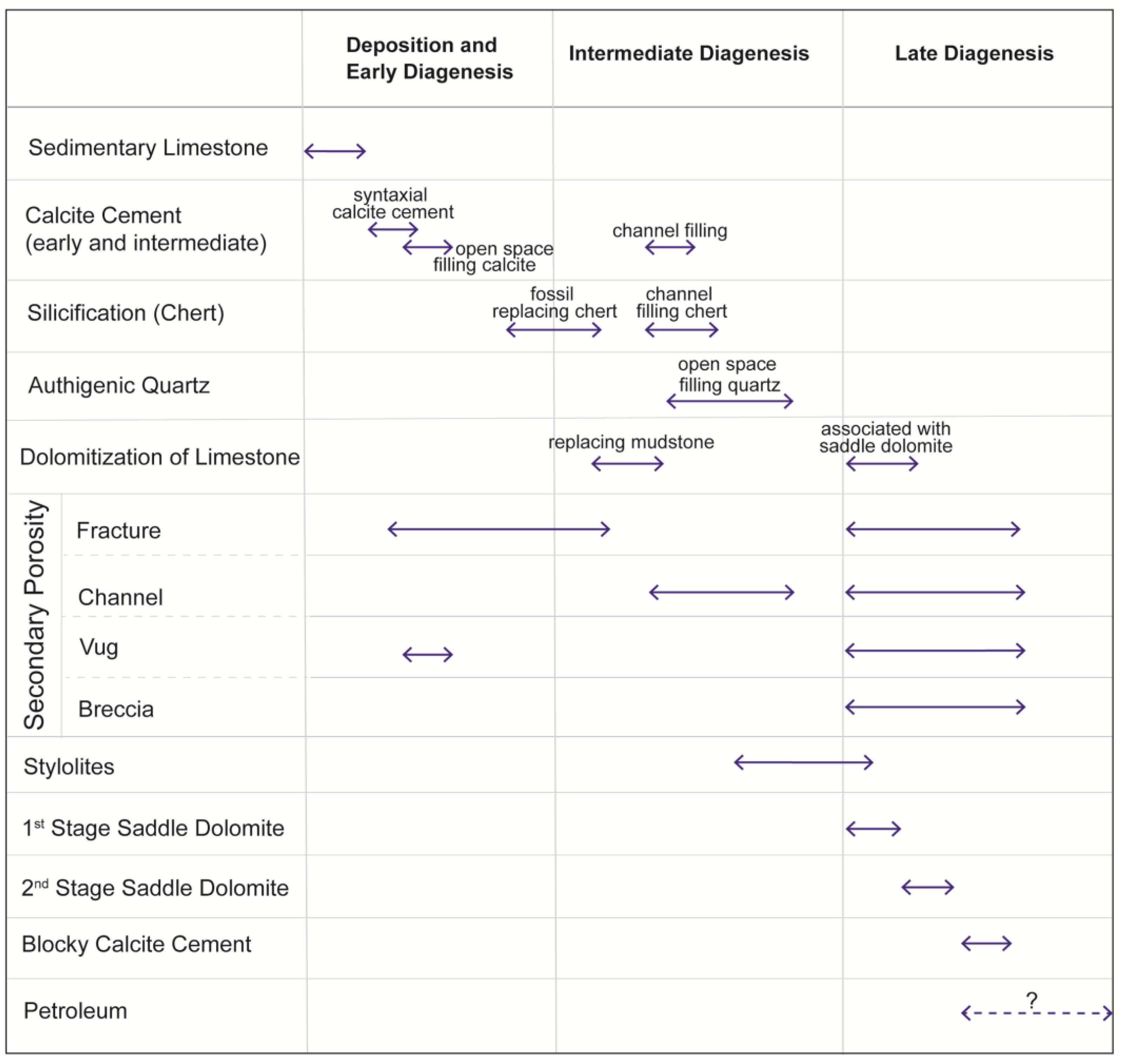

A hypothesis for the relative timing of diagenetic event observed in the RKB core is shown in

Figure 9. The early diagenetic features observed in this study involves early stabilization and lithification of the hosting limestone, composed primarily of skeletal grainstones, wackestones and mudstones, soon after deposition. This includes growth of early intergrain, syntaxial, and vug filling calcite cements (

Figure 5a). Early secondary porosity filled by this cementation includes fractures and vugs. Early diagenetic cementation in Mississippian strata is discussed in detail by Mohammadi et al. [9.10] and is not the focus of this paper. Early to intermediate diagenetic fracture and channel filling include calcite, chert, and authigenic quartz, with the quartz likely precipitated during intermediate diagenesis as the fractures postdate early syntaxial, and vug filling calcite cementation (

Figure 5c,d,e and

Figure 11).

The replacement of skeletal fragments by chert likely occurred at the same time as, or prior to, filling of channels by chert and quartz during intermediate stage of diagenesis (

Figure 5c and 9). Thick accumulation of silicious sponge deposits have been observed in shelf margin in Mississippian (Osagian) strata in Kansas [

54,

55,

56]. Franseen [

25] suggested that a regional upwelling of silica rich water sourced by sponge spicules are a likely source of silica in the Mississippian carbonates.

Dolomite replacing mudstone observed in this study is similar to Mississippian replacement dolomite described by Mohammadi et al. [

10]. They suggested, based on petrography and isotope geochemistry, that the replacement dolomites formed under marine phreatic condition associated with deep circulation of Mississippian seawater.

Formation of fractures and vugs began during the early stages of diagenesis and persisted through to the late stage (

Figure 11). Channels, likely resulting from solution widening of fractures, developed during intermediate to late diagenesis. The timing of the development of this secondary porosity is indicated by their filling by intermediate diagenetic chert, calcite, and authigenic quartz, as well as late diagenetic saddle dolomite. Breccias formed only during the final stage of diagenesis and are observed to be filled only by saddle dolomite and late blocky calcite cements. Early small vug porosity is filled by early calcite cement whereas late diagenetic vugs are filled by saddle dolomite and blocky calcite cement. Development of stylolites, resulting from pressure solution [

57], occurred during intermediate extending to late diagenesis as evidenced by solution of skeletal grains and mud matrix as well as cross cutting relationships observed with fractures, channels (

Figure 5e) and breccias (

Figure 11).

Continued development of fractures, vugs, channels and breccia during late diagenesis are associated with hydrothermal fluid migration through the Mississippian rocks (

Figure 8;

Table 1). The large open spaces likely developed as a result of dissolution by hydrothermal fluids alternating with dolomite and calcite precipitating fluids. The late diagenetic open spaces were filled by saddle dolomites, both 1st and 2nd stage, followed by late calcite cements (

Figure 5f, 6). Saddle dolomite cements are believed to precipitate from warm to hot aqueous fluids after burial [

58,

59] (

Figure 6a,b). Fluid inclusion data (

Figure 8;

Table 1) also indicate that the saddle dolomites precipitated from hot and saline fluids. A second stage of replacement dolomitization (RD-2) of limestone occurred along with possible recrystallization of earlier dolomite and is associated with saddle dolomites late diagenetic open space (

Figure 5f). Following the precipitation of saddle dolomite, blocky calcite cement filled remaining vug, channel, and breccia open space (

Figure 5c and

Figure 6a,b).

Petroleum migration through the section is evidenced by secondary oil inclusions observed in 2nd stage saddle dolomite (

Figure 7c,d). Observation of possible primary and secondary oil inclusion in blocky calcite cements add further evidence for the timing of petroleum migration. The paragenetic timing of petroleum migration observed in this study is consistent with the timing observed in Mississippian strata on the Cherokee – Ozark Platform and in North-Central Oklahoma [

9,

10].

5.2. Composition of Late Diagenetic Fluids

Fluid inclusion homogenization temperature recorded in the Cambrian-Ordovician (Arbuckle Group) of south-central Kansas range approximately between 90 to 131°C [

60]. These temperatures are similar to the temperatures recorded in saddle dolomite cement in the Mississippian of western Kansas (this study) where homogenization temperatures of fluid inclusion assemblages range from 65 to 126°C with salinities ranging from ~18-23 wt.% NaCl eq. These are also similar to fluid inclusions measured in saddle dolomites in Mississippian strata on the Cherokee-Ozark Platform [

9]. Blocky calcite cement assemblages measured in the Mississippian of western Kansas, on the other hand, are cooler (~67 to 100°C) than those measured in late diagenetic calcite cement on the Cherokee-Ozark Platform and overlap with Mississippian calcites cements measured on the Cherokee-Ozark Platform and in north-central Oklahoma. None of the salinities of fluid inclusions measured in this study in calcite (13-23 wt.% NaCl eq.) indicate the presence of dilute fluids such as were observed in Mississippian rocks in north-central Oklahoma or on the Cherokee-Ozark Platform [

9,

10].

In the Mississippian (Osagian) in western Kansas, fluid inclusion temperatures measured in open-space-filling saddle dolomites (92 to 126°C) overlap with the lower range of temperatures measured in the underlying Ordovician (Arbuckle Group) in the nearby Patterson core (53 to 266°C) (

Figure 1 and

Figure 8). Hydrothermal fluids that precipitated saddle dolomite in the Mississippian RKB core have higher salinity compared with the underlying Ordovician rocks (

Figure 8). This suggests a different fluid origin with different pulses of advective fluids in the Mississippian and Ordovician strata. Alternately, and more likely, higher salinities, as well as lower temperatures in the Mississippian fluid inclusions may be due to mixing of upwelling fluids sourced in the Ordovician with descending, cooler, evaporitic fluids sourced from overlying Permian evaporites [

8].

Open space filling calcite cement δ

18O values from the RKB core range from -9.44 to -8.69‰ with δ

13C values ranging from -1.01 to 1.79‰ (

Table 2;

Figure 9) consistent with warm basinal fluids and possible sulfate reduction. These values are comparable with the late-stage of calcite cementation in eastern Kansas [

52], on the Cherakee-Ozark platform [

61], and in the Tri-State MVT district [

9]. Calcite and dolomite carbon and oxygen isotope values from the underlying Arbuckle Group, in the nearby Patterson core, are consistent with precipitation by hot fluids undergoing sulfate reduction (

Figure 9) [

16].

Sr isotope ratios measured in late-stage saddle dolomite and blocky calcite cement in the RKB core overlap with radiogenic Sr ratios measured in late diagenetic calcite cements in Mississippian rocks on the Cherokee-Ozark Platform [

9] and are significantly higher than the Sr ratios measured for calcite cements in the Mississippian of north-central Oklahoma [

10]. These values are more radiogenic than what would expected for carbonates precipitated in equilibrium with the Mississippian seawater (

Table 3,

Figure 10). Although the Sr isotope ratios measured in this study do not reach the highest values of those measured in carbonate cements in Lower Ordovician (Arbuckle Group) carbonates in the nearby Patterson Core (

Figure 1), they fall at the higher end of what would be expected for a system influenced by Arbuckle seawater and overlap with values that would be imparted by fluids that have been modified by granitic basement rocks or sedimentary rocks derived from granitic basement.

Taken together these observations suggest that the fluid responsible for precipitating the saddle dolomite and blocky calcite cement in the Mississippian section in the RKB core were not derived from Mississippian seawater, but rather were introduced from an external source. Based on the fluid inclusion and isotope data obtained for late diagenetic carbonate cements studied in the RKB core, it is evident that the conduit of hydrothermal fluids was not localized in place, but involved upward migration of fluids along faults and fractures, or lateral migration of fluids from the basin to the south and/or west, or a combination of both. The higher salinities and lower temperature of included fluids observed in saddle dolomite and blocky calcite cement are consistent with mixing of these fluids with cooler and more saline fluids descending from overlying Permian strata.

5.3. Fluid Sources and Timing

Multiple pulses of basinal fluids likely affected Phanerozoic rocks on the Midcontinent of North America, including the Mississippian of western Kansas [2,62.63]. Possibly a gravity-driven northward fluid flow system transported hot basinal brines northward out of the Anadarko Basin during late Paleozoic tectonic activity to the south [

60]. Goldstein et al. [

8] suggest that the basinal fluids migrated through the entire stratigraphic package, and are associated with the uplift of the Ouachita and Ancestral Rocky Mountains during late Pennsylvanian and Permian time. Mohammadi et al. [

2] using U-Pb analysis on calcite cements in the same core studied by Goldstein et al. [

8] observed two different pulses of fluid, the first related to the late Pennsylvanian-Permian tectonic events and a second dated to the late Miocene to Pliocene. Published radiometric dates suggest that in addition to the late Pennsylvanian, Permian, and Neogene events, basinal brine migration on the Midcontinent can be dated to rifting in the Gulf of Mexico to the south, during the Early Jurassic and to the Sevier and Laramide Orogenies during the Cretaceous to Paleocene [

2].

It is speculated here that the complex late diagenetic carbonate cement history observed in this study are the result of multiple pulses and a variety of sources of non-resident fluids that influenced Mississippian rocks in western Kansas. We further speculate that hydrothermal fluid flow in the study area may also have involved vertical fluid pumping from lower Ordovician into Mississippian strata, related to fault reactivation and post orogenic events [

2].

5.4. Implications for MVT-Style Mineralization in Western Kansas

Although galena, sphalerite, and other metal sulfides were not found in the examined Mississippian samples of western KS, this study shows that the open-space-filling carbonate cements were precipitated by basinal fluids that are very similar to fluids associated with known MVT mineralization, such as the large Tri-State MVT district, in Mississippian rocks on the Cherokee-Ozark Platform [

9]. Evans [

3] observed sphalerite mineralization in the Ordovician (Arbuckle Group) of western Kansas and suggested the possibility of economic MVT mineralization in the region. Coveney [

4,

64] reported fluid inclusion homogenization temperatures about 80 to >150°C in Ordovician sphalerites in three oil wells in western Kansas, which he attributed to regional advective fluid flow. Further research is certainly warranted, including examination of additional cores and/or well cutting, may identify sulfide mineralization in the Mississippian of western Kansas.

6. Conclusion

This study investigates the origin and timing of dolomite and calcite cementation resulting precipitated by hydrothermal fluids during late diagenesis in Mississippian carbonates in the Rebecca K. Bounds (RKB) core, Greeley County, western Kansas, U.S.A.

Fluid inclusion homogenization temperatures and salinities are comparable with those measured in the Arbuckle Group and in the Mississippian on the Cherokee-Ozark Platform, in north-central Oklahoma, and south-central Kansas. These data, along with radiogenic strontium isotope signatures, indicate that the fluids were not locally sourced and had interacted with granitic basement or basement derived siliciclastic. The evidence suggests possible mixing of upwelling Ordovician-derived fluids with descending Permian evaporitic brines. Fluid movement involved upward migration along faults and fractures, lateral migration from the basin, or a combination of both.

Saddle dolomite, precipitated by warm saline fluids, predate blocky calcite cements precipitated by cooler saline brines. Petroleum migration occurred following saddle dolomite precipitation, and is recorded by secondary oil inclusions in saddle dolomite and (possibly) primary and secondary oil inclusions in blocky calcite cement. Isotopic evidence (C, O, Sr) and previously published radiometric dating indicate that fluid flow affecting the RKB core is likely associated with post orogenic and fault reactivation events.

Although galena, sphalerite, or other sulfide minerals were not identified in the studied Mississippian rocks, the hydrothermal fluids that precipitated saddle dolomite and blocky calcite share similar temperature, salinity, and isotopic characteristics with basinal fluids responsible for MVT mineralization in the Tri-State district on the Cherokee-Ozark Platform. Previous studies identified sphalerite in the underlying Arbuckle Group with fluid inclusions characteristics of MVT mineralization. The absence of sulfides in the RKB core does not preclude their occurrence in Mississippian strata elsewhere in western Kansas. Additional subsurface sampling is required to evaluate this potential more fully.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

More information can be found in Kansas Geological Survey Open-File Report no. 2024-15, 12 and Kansas Geological Survey Open-File Report no. 2024-44, 20.

Acknowledgments

I thank the Kansas Geological Survey for funding the project above. I am further indebted to Joseph Andrew, Research Isotope Geochemistry Lab Manager at KU, and to Greg Ludvigson and Robert Goldstein for their assistance and for granting me access to the CL laboratory used in this study. I would also like to thank Cara Burberry for her valuable insights on tectonics, which strengthened the interpretation of this work. I am grateful to Kolbe Andrzejewski for his assistance with the map. I am deeply grateful to Jay M. Gregg for his insightful comments, thorough review, and guidance, which significantly improved the quality of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

No conflict of interest

References

- Mohammadi, S.; Hollenbach, A.; Goldstein, R.; Moller, A. Timing of Hydrothermal Fluid Flow Events in Kansas and Tri-State Mineral District. In Midcontinent Carbonate Research Virtual Symposium Extended Abstracts, Ortega-Ariza, E., Bode-Omoleye, I., Hasiuk, F.J., Mohammadi, S., Franseen, E.K., Eds.; Kansas Geological Survey Lawrence, 2021; Technical Series 24, pp. 34-36.

- Mohammadi, S.; Hollenbach, A.M.; Goldstein, R.H.; Möller, A.; Burberry, C.M. Controls on timing of hydrothermal fluid flow in south-central Kansas, north-central Oklahoma, and the Tri-State Mineral District. Midcontinent Geoscience 2022, 3, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.L.C. Sphalerite mineralization in deep lying dolomites of Upper Arbuckle age, west central Kansas. Economic Geology 1962, 57, 548–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coveney, R.M., Jr.; Goebel, E.D. New fluid inclusion homogenization temperatures for sphalerite from minor occurrences in the midcontinent area. In International Conference on Mississippi Valley-type Lead Zinc Deposits: Proceedings Volume, Kisvarsanyi, G., Grant, S.K., Pratt, W.P., Koenig, J.W., Eds.; University of Missouri-Rolla: Rolla, MO, 1983; pp. 234-242.

- Shelton, K.L.; Bauer, R.M.; Gregg, J.M. Fluid inclusion studies of regionally extensive epigenetic dolomites, Bonneterre Dolomite (Cambrian), southeast Missouri: Evidence of multiple fluids during dolomitization and lead-zinc mineralization. Geological Society of America Bulletin 1992, 104, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, J.M.; Shelton, K.L. Mississippi Valley-type mineralization and ore deposits in the Cambrian-Ordovician Great American Carbonate Bank. In The Great American Carbonate Bank: The Geology and Economic Resources of the Cambrian-Ordovician Sauk Megasequence of Laurentia, Derby, J.R., Fritz, R.D., Longacre, S.A., Morgan, W.A., Sternach, C.A., Eds.; AAPG: 2012; Memoir 98, pp. 163–186.

- Ramaker, E.M.; Goldstein1, R.H.; Franseen, E.K.; L., W.W. What controls porosity in cherty fine-grained carbonate reservoir rocks? Impact of stratigraphy, unconformities, structural setting and hydrothermal fluid flow: Mississippian, SE Kansas. In Fundamental Controls on Fluid Flow in Carbonates: Current Workflows to Emerging Technologies, Agar, S.M.G., S. (eds) 2015. Fundamental Controls on Fluid Flow in Carbonates: Current, Workflows to Emerging Technologies. Geological Society, L., Special Publications, 406, 179–208, Eds.; Geological Society, London: London, 2015; Special Publication 406, pp. 179–208.

- Goldstein, R.H.; King, D.B.; Watney, W.L.; Pugliano, T.M. Drivers and history of late fluid flow: Impact on midcontinent reservoir rocks. In Mississippian Reservoirs of the Mid-Continent, U.S.A., Grammer, G.M., Gregg, J.M., Puckette, J.O., Jaiswal, P., Pranter, M., Mazzullo, S.J., Goldstein, R.H., Eds.; AAPG: Tulsa, 2019; Memoir 122, pp. 417–450.

- Mohammadi, S.; Gregg, J.M.; Shelton, K.L.; Appold, M.S.; Puckette, J.O. Influence of late diagenetic fluids on Mississippian carbonate rocks on the Cherokee – Ozark Platform, NE Oklahoma, NW Arkansas, SW Missouri, and SE Kansas. In Mississippian Reservoirs of the Mid-Continent, U.S.A., Grammer, G.M., M., G.J., Puckette, J.O., Jaiswal, P., Pranter, M., Mazzullo, S.J., Goldstein, R.H., Eds.; AAPG: Tulsa, 2019a; Memoir 122, pp. 325-352.

- Mohammadi, S.; Ewald, T.; Gregg, J.M.; Shelton, K.L. Diagenetic history of Mississippian carbonate rocks in the Nemaha Ridge area, north-central Oklahoma, USA. In Mississippian Reservoirs of the Mid-Continent, U.S.A., Grammer, G.M., M., G.J., Puckette, J.O., Jaiswal, P., Pranter, M., Mazzullo, S.J., Goldstein, R.H., Eds.; AAPG: Tulsa, 2019b; Memoir 122, pp. 353-378.

- Temple, B.J.; Bailey, P.A.; Gregg, J.M. Carbonate diagenesis of the Arbuckle Group north central Oklahoma to southeastern Missouri:. Shale Shaker 2020, 71, 10–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hollenbach, A.M.; Mohammadi, S.; Goldstein, R.H.; Möller, A. Hydrothermal fluid flow and burial history in the STACK play of north-central Oklahoma. In Midcontinent Carbonate Research Virtual Symposium Extended Abstracts, Ortega-Ariza, E., Bode-Omoleye, I., Hasiuk, F.J., Mohammadi, S., Franseen, E.K., Eds.; Kansas Geological Survey: Lawrence, 2021; Technical Series 24, pp. 28–30.

- Machel, H.G.; Lonnee, J. Hydrothermal dolomite—a product of poor definition and imagination. Sedimentary Geology 2002, 152, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.S.; Newell, D.K. The Mississippian Limestone Play in Kansas: Oil and gas in a complex geologic setting. 2013, Public Information Circular 33, 1-6.

- Hagni, R.D.; Grawe, O.R. Mineral paragenesis in the Tri-state district Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma. Economic Geology 1964, 59, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, S.; Ortega-Ariza, D.; Khameiss, B. Preliminary data on the diagenesis of Mississippian (Osagian) strata: A study of the Rebecca K. Bounds core, Greeley County, Kansas. 2024, Kansas Geological Survey Open-File Report no. 2024-15, 1-12.

- Walters, R.F. Buried Precambrian hills in northeastern Barton County, central Kansas. AAPG Bulletin 1946, 30, 660–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam, D.F. The geologic history of Kansas; Kansas Geological Survey: Lawrence, 1963; Kansas Geological Survey Bulletin 162. [CrossRef]

- Cole, V.B. Subsurface Ordovician-Cambrian rocks in Kansas. 1975, Subsurface Geology Series 2, 18.

- Franseen, E.K.; Byrnes, A.P.; Cansler, J.R.; Steinhauff, D.M.; Carr, T.R.; Dubois, M.K. Geologic controls on variable character of Arbuckle reservoirs in Kansas—An emerging picture. 2003, Kansas Geological Survey Open-file Report 2003-59, 30.

- Lee, W. Stratigraphy and Structural Development of the Forest City Basin in Kansas; Kansas Geological Survey: Lawrence, 1956; Kansas Geological Survey Bulletin 121. [CrossRef]

- Goebel, E.D. Stratigraphic succession in Kansas (Kansas Geological Survey Bulletin 189, pp. 39–53). Ordovician System in Kansas. In Stratigraphic succession in Kansas, Merriam, D.F., Ed.; Kansas Geological Survey: Lawrence, 1968; Kansas Geological Survey Bulletin 189, pp. 39–53.

- Taylor, H. Siluro-Devonian strata in central Kansas. AAPG Bulletin 1946, 30, 1221–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutschick, R.C.; Sandberg, C.A. Mississippian continental margins of the conterminous United States. In The Shelfbreak, Stanley, D.J., Moore, G.T., Eds.; SEPM: Tulsa, OK, 1983; Volume 33, pp. 79-96.

- Franseen, E.K. Mississippian (Osagean) shallow-water, mid-latitude siliceous sponge spicule and heterozoan carbonate facies: An example from Kansas with implications for regional controls and distribution of potential reservoir facies. Current Research in Earth Sciences, Kansas Geological Survey Bulletin 2006, 252, part 1, 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Van Schmus, W.R.; Hinze, W.J. The midcontinent rift system. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 1985, 13, 345–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baars, D.L. Basement tectonic configuration in Kansas. Kansas Geological Survey Bulletin 1995, 237, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendsen, P.; Blair, K.P. Subsurface structural maps over the Central North American rift system (CNARS), central Kansas, with discussion. 1986, Subsurface Geology Series 8, 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Dolton, G.L.; Finn, T.M., Petroleum geology of Nemaha uplift, central midcontinent. 1989, US Geological Survey, Open-file-Report 88-450D, 39 p.

- Gay, S.P. The Nemaha Trend - A system of compressional thrust-fold, strike-slip structural features in Kansas and Oklahoma, Part 2. Shale Shaker 2003, 54, 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Gay, S.P. The Nemaha Trend - A system of compressional thrust-fold, strike-slip structural features in Kansas and Oklahoma, Part 1. Shale Shaker 2003, 54, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Baars, D.L.; Stevenson, G.M. Subtle stratigraphic traps in Paleozoic rocks of Paradox Basin. In The Deliberate Search for the Subtle Trap, Halbouty, M.T., Ed.; AAPG: Tulsa, 1982; Volume Memoir 32, pp. 131-158. (accessed on null).

- Hanson, R.E.; Puckett, R.E., Jr.; Keller, G.R.; Brueseke, M.E.; Bulen, C.L.; Mertzman, S.A.; Finegan, S.A.; McCleery, D.A.; et al. (2013). Intraplate magmatism related to opening of the southern Iapetus Ocean: Cambrian Wichita igneous province in the Southern Oklahoma rift zone. Lithos, 57–70. Intraplate magmatism related to opening of the southern Iapetus Ocean: Cambrian Wichita igneous province in the Southern Oklahoma rift zone. Lithos 2013, 174, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turko, M.; Mitra, S. Structural geometry and evolution of the Carter-Knox structure, Anadarko Basin, Oklahoma. AAPG Bulletin 2021, 105, 1993–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turko, M.; Mitra, S. Macroscopic structural styles in the southeastern Anadarko Basin, southern Oklahoma. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2021, 125, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, N.F.; van Wijk, J.W.; Leary, R.; Axen, G.J. Late Paleozoic Evolution of the Anadarko Basin: Implications for Laurentian Tectonics and the Assembly of Pangea. Tectonics 2022, 41, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, D.A. Stratigraphy of lower Pennsylvanian rocks in northeastern Hugoton Embayment. In South-Central Kansas: Guidebook, 24th Field Conference in Cooperation with the Kansas Geological Survey; Kansas Geological Society: 1959; pp. 107-115.

- Fritz, R.D.; Mitchell, J.R. The Anadarko “Super” Basin: 10 key characteristics to understand its productivity. AAPG Bulletin 2021, 105, 1199–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Well, A.B.; Yonkee, A. The Laramide orogeny: Current understanding of the structural style, timing, and spatial distribution of the classic foreland thick-skinned tectonic system. In Laurentia: Turning points in the evolution of a continent, Whitmeyer, S.J., Williams, M.L., Kellett, D.A., Tikoff, B., Eds.; Geological Society of America: Boulder, 2023; Geological Society of America Memoir 220, pp. 707–771.

- Lane, H.R.; De Keyser, T.L. Paleogeography of the Late Early Mississippian (Tournaisian 3) in the central and southwestern United States. In Paleozoic Paleogeography of the West-Central United States, Fouch, T.D., Megathan, E.R., Eds.; SEPM Rocky Mountain Section: Denver, 1980; Symposium 1, pp. 149-162.

- Zeller, D.E. The Stratigraphic Succession in Kansas. 1968, Kansas Geological Survey Bulletin 189, 81. https://doi.org/10.17161/kgsbulletin.no.i189.22214. [CrossRef]

- Zambito, J.J.; Benison, K.C.; Foster, T.M.; Soreghan, G.S.; Kane, M. Lithostratigraphy of Permian Red Beds and Evaporites in the Rebecca K. Bounds Core, Greeley County, Kansas. 2012, Open-file-Report 2012-15, 46.

- Dunham, R.J. Classification of carbonate rocks according to depositional texture. In Classification of carbonate rocks, Ham, W.E., Ed.; AAPG: Tulsa, 1962; Volume Memoir 1, pp. 108-121.

- Sibley, D.F.; Gregg, J.M. Classification of dolomite rock textures. Journal of Sedimentary Petrology 1987, 57, 967–975. [Google Scholar]

- Choquette, P.W.; Pray, L.C. Geologic nomenclature and classification of porosity in sedimentary carbonates. AAPG Bulletin 1970, 54, 207–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, R.H.; Reynolds, T.J. Systematics of fluid inclusions in diagenetic minerals; SEPM: Tulsa, OK, 1994; Short Course 31.

- Bodnar, R.J. Revised equation and table for determining the freezing point depression of H20-NaCl solutions. Geochima et Cosmochimica Acta 1993, 57, 683–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, J.R.; Clayton, R.N.; Mayeda, T.K. Oxygen isotope fractionation in divalent metal carbonates. Journal of Chemical Physics 1969, 51, 5547–5558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, I.; O’Neil, J.R. Compilation of stable isotope fractionation factors of geochemical interest. US Geological Survey Professional Paper 1977, 440–KK. [Google Scholar]

- Shelton, K.L.; Beasley, J.M.; Gregg, J.M.; Appold, M.S.; Crowley, S.F.; Hendry, J.P. Evolution of a carboniferous carbonate-hosted sphalerite breccia deposit, Isle of Man. Mineralium Deposita 2011, 46, 859–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxton, T.M.; Sibley, D.F. Pressure solution features in shallow burried limestone. 1981, 51, 19-26. [CrossRef]

- Ritter, M.E.; Goldstein, R.H. Diagenetic controls on porosity preservation in lowstand oolitic andcrinoidal carbonates, Mississippian, Kansas and Missouri, USA. In Linking Diagenesis to Sequence Stratigraphy, Morad, S., Ketzer, M., de Ros, L.F., Eds.; International Association of Sedimentologists: London, 2012; Special Publication 45, pp. 379–406.

- Mii, H.; Grossman, E.L.; Yancey, T.E. Carboniferous isotope stratigraphies of North America: Implications for Carboniferous paleoceanography and Mississippian glaciation. Geological Society of America Bulletin 1999, 111, 960-973. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.P.; Longman, M.W.; Lloyd, R.M. Spiculitic chert reservoir in Glick field, south-central Kansas. The Mountain Geologist 1995, 32, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, S.L.; Mullarkey, J.C.; Longman, M.W.; Colleary, W.M.; Rogers, J.P. Mississippian “chat” reservoirs, South Kansas: Low-Resistivity pay in a complex chert reservoir. AAPG Bulletin 1998, 82, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watney, W.L.; Guy, W.J.; Byrnes, A.P. Characterization of the Mississippian chat in south-central Kansas. AAPG Bulletin 2001, 85, 85–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, W.C.; Schot, E.H. Stylolites: their nature and origin. Journal of Sedimentary Petrology 1968, 38, 175–191. [Google Scholar]

- Radke, B.M.; Mathis, R.L. On the formation and occurrence of saddle dolomite. Journal of Sedimentary Petrology 1980, 50, 1149–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, J.M.; Sibley, D.F. Epigenetic dolomitization and the origin of xenotopic dolomite texture. Journal of Sedimentary Petrology 1984, 54, 908–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.D.; Goldstein, R.H. History of hydrothermal fluid flow in the midcontinent, USA: the relationship between inverted thermal structure, unconformities and porosity distribution. In Reservoir Quality of Clastic and Carbonate Rocks: Analysis, Modelling and Prediction, Armitage, P.J., Butcher, A.R., Churchill, J.M., Csoma, A.E., Hollis, C., Lander, R.H., Omma, J.E., Worden, R.H., Eds.; The Geological Society of London: London, 2018; Special Publication 435, pp. 283-320. [CrossRef]

- Morris, B.T.; Mazzullo, S.J.; Wilhite, B.W. Sedimentology, biota, and diagenesis of ‘reefs’ in Lower Mississippian (Kinderhookian To Basal Osagean: Lower Carboniferous) strata in the St. Joe Group in the western Ozark Area. Shale Shaker 2013, 64, 194–227. [Google Scholar]

- Garven, G.; Ge, S.; Person, M.A.; Sverjensky, D.A. Genesis of stratabound ore deposits in the Midcontinent basins of North America. 1. The role of regional groundwater flow. American Journal of Science 1993, 293, 497–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coveney, R.M., Jr.; Ragan, V.M.; Brannon, J.C. Temporal benchmarks for modeling Phanerozoic flow of basinal brines and hydrocarbons in the southern Midcontinent based on radiometrically dated calcite. Geology 2000, 28, 795–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coveney, R.M., Jr.; Goebel, E.D.; Ragan, V.M. Pressures and temperatures from aqueous fluid inclusions in sphalerite from midcontinent country rocks. Economic Geology 1987, 82, 740–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).