1. Introduction

THE healthcare reimbursement landscape isn't transforming overnight, but the shift is happening—gradually, almost quietly. With each wave of digital innovation, systems are becoming a bit more open, a touch more efficient, and, frankly, easier to trust [

1]. These aren't just lofty ideas anymore; the changes are happening on the ground, in real systems, and people are starting to notice. Among the newer technologies being talked about, distributed ledger technology (blockchain)-based automated clinical decision systems (smart contracts) keep cropping up as more than just a buzzword [

2,

3]. In this study, smart contracts are conceptualized as automated clinical decision systems for reimbursement workflows. What makes them stand out isn't just the tech itself—it's the promise of a structure that's nearly tamper-proof, which matters a great deal in areas like claims adjudication, data sharing, and billing processes, where even small errors can carry big consequences. Because they keep transactions permanent and easy to verify. They can reduce paperwork, catch fraud, and build trust among users [

4,

5]. For instance, consider the reimbursement process for a chronic patient receiving treatment at different clinics. The verification of critical data by the insurance company, such as the patient's treatment history, specialist reports, and lab results, is often based on manual processes and can take weeks. These data silos and manual verification steps not only delay the patient's access to treatment but also create opportunities for administrative errors and fraud, which this framework aims to address. Recent studies highlight how clinician resistance remains a critical barrier to blockchain adoption in healthcare settings [

6,

7]. Adoption has been uneven. Many studies focus on technical challenges, regulations, or user trust, but health data exchange systems are complex and interconnected. These factors are connected. For example blockchain's unchangeable records help make things more transparent. They can also clash with laws that require data to be changed or deleted. Legacy EHR systems might struggle to work with newer, decentralized setups, and clinical staff might resist automation [

3,

8]. This tension is particularly acute where GDPR's 'right to erasure' directly conflicts with blockchain's immutability in patient reimbursement workflows [

9].

This paper develops a Blockchain-Based Trust Framework that integrates regulatory compliance, system design, and trust-building into a single model. Drawing on Institutional Theory [

10] Human-Centered Design Principles [

11], and Trust Theory [

12], it treats blockchain smart contracts as part of dynamic institutional contexts rather than isolated tech. The framework specifically addresses HIPAA-compliant data governance for health insurance-provider interactions.

Using a mixed-methods approach—systematic literature review, participatory action research, focus groups, and interviews—the paper balances theory and practice. It aims to guide health IT administrators, clinical data stewards, and tech developers toward compliant, scalable, and trustworthy blockchain adoption. Ultimately, this study provides not just a technical roadmap, but a strategic asset for policymakers aiming to foster digital health innovation responsibly, and for industry leaders seeking to build next-generation, value-based healthcare services on a foundation of trust.

Research question:

How can blockchain-based smart contracts be effectively integrated into healthcare reimbursement systems while ensuring regulatory compliance, fostering clinician trust, and achieving interoperability with existing processes? Our framework responds to the dual challenges of health system adoption barriers [

6,

13] and regulatory-technical conflicts [

9] identified in recent literature.

2. Literature

- A.

Blockchain-Based Smart Contracts in Healthcare Reimbursement

Blockchain technology is exerting a significant impact on several industries, including health insurance, because it is decentralized and cryptographically secure. Smart contracts are self-executing digital protocols that run on their own and follow rules that have been defined [

14,

15].

Fundamentally, smart contracts can be defined as code-based automation tools designed to automatically execute predetermined actions once specific conditions are fulfilled [

16]. The fact that claims processing requires less effort highlights their potential to play a leading role particularly in the field of health insurance operations [

17]. In fact, smart contracts offer protection against bureaucratic obstacles and fraud through their robust structure and ability to generate easily verifiable records [

3,

18,

19].

By automating and streamlining intricate processes, smart contracts are positioned to play a transformative role in health insurance, reducing the need for human intervention while enhancing both operational efficiency and systemic transparency [

20,

21]. Their practical utility becomes particularly clear in routine operations; tasks such as processing health insurance claims, renewing coverage, and securely transferring data between providers and payers benefit considerably from their use [

20]. This automation is underpinned by a robust security architecture designed for handling protected health information (PHI), where privacy and precision are paramount.

Operating on cryptographically secure, decentralized networks, smart contracts inherently safeguard data integrity. Beyond mere protection, they introduce a level of auditable traceability often absent in traditional systems. Every transaction leaves a verifiable digital trail—detailing precisely who accessed what information and when. This built-in accountability fosters more responsible health data governance, a crucial advantage in a sector where oversight is frequently fragmented [

22,

23].

Despite these potential benefits, the literature reveals considerable debate regarding the readiness of smart contracts for widespread clinical adoption. A primary impediment is interoperability; Li et al. 2020 [

24] identify the inherent complexity of achieving semantic interoperability between decentralized protocols and disparate legacy systems. Scalability remains a critical concern, with recent studies focusing on novel solutions to enhance performance [

25,

26]. It is another critical concern highlighted by Griggs et al. [

27] and Sadath et al. [

25] referring to the potential inability of existing blockchain platforms to maintain performance under the high transactional throughput required by large-scale healthcare systems. Furthermore, Geng et al. [

23] argue that persistent data silos stall progress, as a lack of seamless data exchange negates the promised efficiencies of automation. Consequently, despite their theoretical advantages, substantial implementation barriers hinder the real-world deployment of these technologies. While these studies identify key technical and infrastructural barriers, a framework that integrates these challenges with the equally critical sociotechnical factors of clinician trust and regulatory compliance remains a significant gap in the literature.

- B.

Healthcare Data Governance and Regulatory Compliance Challenges

Healthcare payers are under constant pressure to comply with complex regulations governing the use of protected health information (PHI) [

21]. In the European context, this typically involves adherence to the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), while in the United States, covered entities must meet the requirements set out by HIPAA. But these aren't just formal checkboxes—they demand cryptographic safeguards to be in place [

27,

28]. Part of that involves respecting patient autonomy rights—such as the ability to request the erasure of clinical records—and upholding consistently high data governance standards [

29]. These expectations form the baseline, not the end goal, making compliance both a legal obligation and a health informatics necessity.

Blockchain, by design, is built to create immutable audit trails. That's one of its biggest selling points, and it's why some see it as a game-changer. Yet, as Corte-Real et al. [

9] and others point out that same cryptographic permanence could actually clash with health data privacy regulations [

30,

31,

32]. If EHR-derived data can't be altered or removed, how do you comply with rules that say people have a right to erasure? It's a real problem—and one that could slow down or even block wider adoption of blockchain in health insurance.

To address this inherent tension between immutability and regulatory compliance, the literature proposes several distinct yet complementary strategies. These can be broadly categorized into architectural and cryptographic approaches. On the architectural front, researchers are exploring hybrid models; for instance, Xu et al. 2024 [

33] have tested on/off-chain architectures where sensitive PHI is stored off-chain in a mutable database, while an immutable, verifiable hash of that data is recorded on-chain. This approach aims to preserve data integrity without sacrificing the ability to erase records as required by regulations. In parallel, cryptographic solutions offer another layer of protection. Barnes, 2024 [

34] considers techniques like privacy-preserving cryptography, which allow for data integrity verification without revealing the underlying PHI, thus mitigating privacy risks. A practical application demonstrating the synthesis of such principles is reported by Al [

16]. Their smart contract-based health information exchange platform successfully enhanced end-to-end security and prevented unauthorized data access, showcasing how these theoretical solutions can be operationalized to create robust and compliant health data governance systems.

- C.

Clinical Workflow Integration Perspectives

Health insurance, in addition to technical and regulatory aspects, are in fact part of complex health information ecosystems. According to human-technology interaction theory [

11,

35], technology and organizational processes mutually influence one another. Indeed, this point is emphasized with examples in the relevant literature by Orlikowski 1992 [

36]. When evaluating Orlikowski's [

36] study, it is suggested that if claims processing workflows remain largely paper-based or if there is a lack of clinician training in digital systems, these factors may pose significant challenges to the adoption of blockchain technology.

However, a review of recent studies in the relevant literature, such as Li et al. 2020 [

24] and Geng et al. 2024 [

23], highlights that the transition to blockchain technology and its integration with existing clinical IT infrastructure may eliminate health data silos and streamline patient revenue cycles [

23,

24]. Indeed, the clinical informatics literature consistently demonstrates that such data silos disrupt care coordination, particularly for chronic patients receiving services from multiple providers, leading to inefficiencies like duplicate testing and even preventable medical errors [

1,

37,

38]. From the perspective of Institutional Theory, Scott , 2005 [

10] states that hospital culture and professional norms play a role in shaping individuals' decisions on whether or not to adopt and use technology.

However, a significant structural tension emerges from the incongruity between blockchain's decentralized architecture and the predominantly centralized governance of the health insurance environment. Most reimbursement systems are built upon clear hierarchies, formal oversight, and well-defined clinical data stewardship, which create predictable structures of accountability [

39,

40]. This fundamental misalignment creates significant institutional friction. As Institutional Theory suggests, established professional norms and hospital cultures shape technology adoption [

10], and the removal of a central intermediary—a core feature of blockchain—can introduce ambiguity regarding responsibility and oversight. Trust emerges as a pivotal factor, manifesting in two distinct forms. While technical trust is derived from the technology's inherent features like cryptographic audit trails and immutability, institutional trust is cultivated through adherence to health data regulations and transparent decision-making protocols [

41,

42]. Ultimately, user trust in such a system depends on a synthesis of both: the perceived reliability of automated clinical decisions and the auditable, compliant nature of the underlying governance model [

43,

6].

- D.

Trust in Blockchain-Enabled Health Systems

Trust plays a pivotal role in whether blockchain can genuinely find its footing within health insurance ecosystems [

18,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49]. What earns that trust, especially on the technical front, is the technology's cryptographic data integrity and the use of healthcare-grade encryption methods. These elements work quietly in the background to limit claims fraud and make secure PHI exchange not just possible, but practical [

22,

23].

However, technical robustness alone is insufficient to guarantee adoption. From a health informatics standpoint, the critical adoption barrier for smart contracts is not a question of technical feasibility, but of sociotechnical integration. The technology's cryptographic capacity to secure health records is well-established [

29]; however, this potential is consistently undermined by pragmatic, human-centered challenges. Chief among them is a pervasive lack of provider awareness, which fosters the very skepticism and active resistance that can halt implementation [

6,

7]. This "institutional trust deficit"—a critical barrier examined by Geng et al. [

23] and Sai et al. [

50]—can derail entire implementation efforts. The literature points to a clear strategy to counter this: making the system observable. This is not an abstract goal; it is achieved through tangible tools. Immutable audit logs and clinician-facing transparency dashboards, for example, are proposed as mechanisms to make the "black box" transparent. This level of transparency serves a critical function: it replaces ambiguity with verifiability. By enabling clinicians to audit the system's logic and outcomes, such tools directly address the root of skepticism and begin to cultivate the evidence-based trust required for clinical adoption.

- E.

Synthesis and Identification of the Research Gap

A significant chasm exists between the theoretical promise and the practical application of blockchain in healthcare, a gap largely perpetuated by the fragmented nature of the academic literature. On one side of this chasm, a robust body of technical literature explores protocol feasibility [

3,

18] yet these studies often propose solutions in a vacuum, underestimating the powerful sociotechnical forces of regulatory compliance and provider trust.

On the other side, regulatory analyses frequently lack deep technical grounding, failing to address the immense practical challenges of EHR integration [

51,

52]. The human element is similarly isolated; studies on clinician acceptance, while valuable, often examine user attitudes without grappling with the systemic requirements of interorganizational data exchange [

6,

7,

43].The result is a disjointed body of knowledge that fails to offer the integrated, actionable roadmap that practitioners actually need. Beyond this academic fragmentation, our synthesis reveals a more profound, practical gap: a striking scarcity of published real-world case studies detailing the successful, scaled implementation of blockchain systems in healthcare reimbursement. This theory-practice gap is not accidental; it is a direct consequence of the siloed approaches mentioned above. Technical frameworks proposed in isolation often fail when faced with the complex regulatory and human-centered realities of clinical practice, leading to pilot projects that stall or fail to publish their outcomes. Therefore, the critical research gap is not only the lack of an integrated model, but the lack of a validated, practical blueprint that can guide organizations across this implementation chasm.

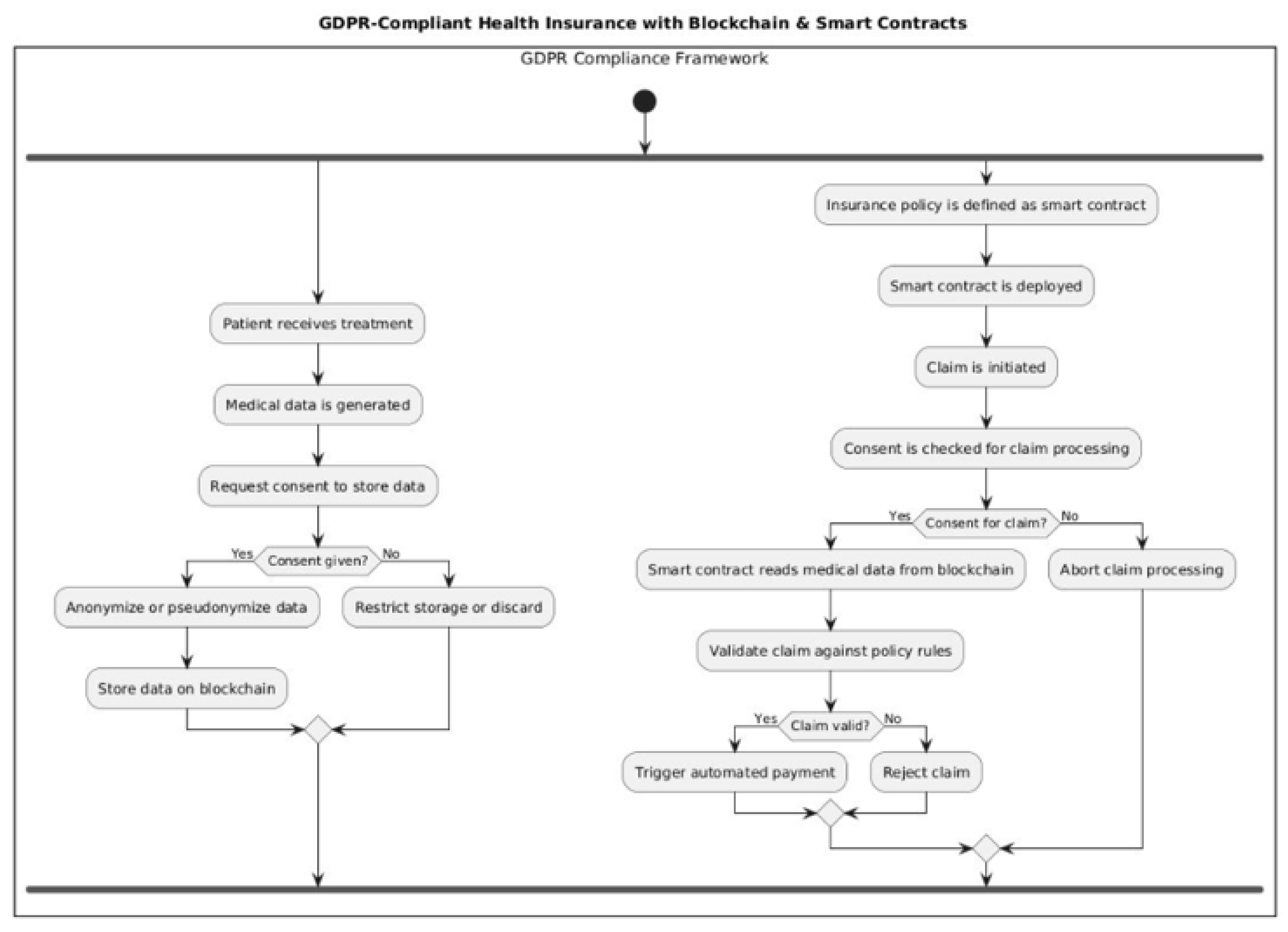

The direct consequence of this pervasive academic siloing is a critical research gap, leaving the field without a holistic implementation model. To systematically illustrate this fragmentation,

Table 1 categorizes the dominant research streams by their primary focus and maps their corresponding limitations.

- F.

The Blockchain-Based Trust Framework: A Proposed Solution

This study introduces the Blockchain-Based Trust Framework, an integrated model designed to synthesize three critical domains: FHIR-compatible technical architecture, modular regulatory compliance, and clinician trust-building protocols. By offering evidence-based implementation blueprints, our framework provides a unified approach for stakeholders navigating the complexities of blockchain adoption in health insurance. We contend that this work contributes directly to both health informatics theory and clinical implementation science, particularly where auditable trust and regulatory adherence are non-negotiable.

Designed for adaptability, the framework's architecture is not confined to a single regulatory environment. While initially informed by the European GDPR, its configurable compliance modules can be readily tailored to meet U.S. HIPAA requirements, and its regional policy adapters can facilitate localization for emerging privacy regulations across the Asia-Pacific.

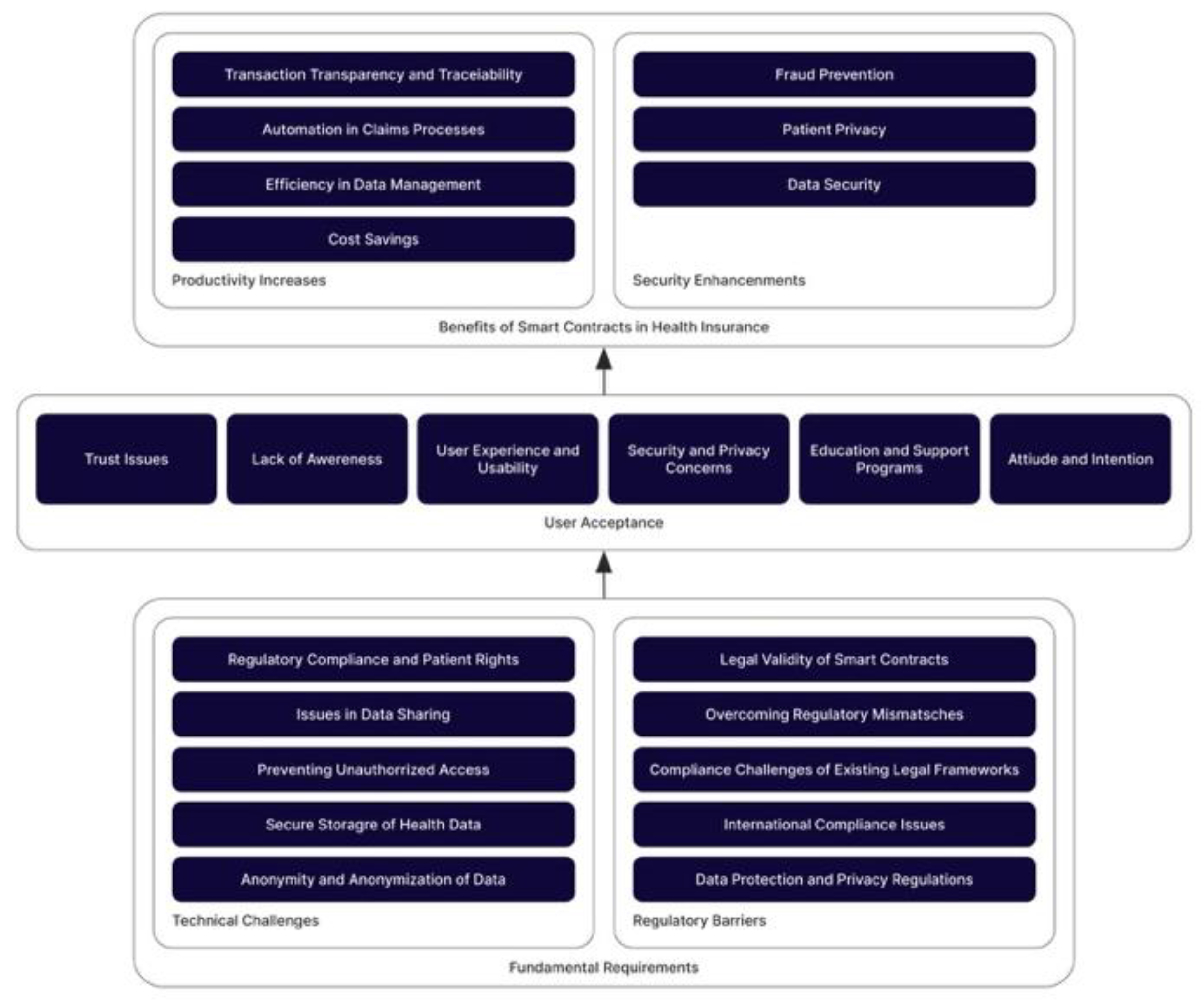

Beyond its immediate utility, the framework opens a critical avenue for future research: extending the model to accommodate not just legal-technical alignments but also crucial variations in clinical culture and patient data stewardship norms. Investigating these sociocultural factors would significantly enhance the framework’s adaptability, moving it toward true cross-jurisdictional interoperability while respecting sovereign compliance standards. The thematic analysis from our systematic literature review, which forms the foundation of this framework, is detailed in

Appendix A with the concepts and selected sentences from the articles in Table VII, and the conceptual framework in Figure 5.

3. Methodology

We developed the Blockchain-Based Trust Framework using a rigorous mixed-methods approach, necessitated by the multidimensional nature of trust within complex health information ecosystems. Our methodology integrated four distinct forms of inquiry: (1) A systematic literature review to anchor the framework in established theories of human-technology interaction. (2) Participatory action research (PAR) to ensure our findings were grounded in the realities of existing health insurance operations. (3,4) Targeted focus groups and semi-structured interviews with providers and administrators to capture stakeholder-specific insights and identify practical barriers.

This synthesis of theoretical review and empirical fieldwork produced a framework that is both conceptually robust and directly attuned to the regulatory and health IT integration challenges of real-world implementation. This work thus represents a critical step toward operationalizing abstract constructs—like cryptographic audit trails and transparent decision-making—within functioning provider networks.

- A.

Research design

Exploratory phase:

To ground the research in current scholarship, a structured literature review was conducted, guided by the PRISMA protocol [

53]. The scope of this review was intentionally focused, targeting peer-reviewed publications from 2018 to 2025. Following the screening and selection of the most relevant studies, a thematic content analysis was systematically performed. This analysis enabled the identification of several recurring conceptual themes that were foundational to our framework's development, namely: the role of trust, the interaction between human and technological factors, and the complexities of regulatory compliance in health insurance innovation. Patterns didn't emerge all at once—they took shape gradually, as key themes were coded and grouped to make sense of what the studies were really saying. This systematic analysis was instrumental in mapping the critical interdependencies and recurring conflicts between the identified themes, a process that directly informed the conceptual architecture of our framework. Interestingly, while the PRISMA framework is often seen as a rigid tool, in this case, it functioned more like a flexible scaffold. It offered structure without boxing the researchers in, which proved essential for a topic as layered and evolving as this one. Rather than casting too wide a net, the team kept the search deliberately focused. Keywords like “blockchain,” “health insurance,” “smart contracts,” “data privacy,” and “trust in e-health” weren't just chosen at random—they were the product of careful reflection on what mattered most to the study. These terms helped cut through irrelevant material and home in on sources that actually spoke to the research questions. To back this up with credibility, databases like IEEE Xplore, PubMed, and Scopus were used, ensuring that the evidence came from respected, peer-reviewed channels.

Framework development phase: The framework didn't appear fully formed—it developed gradually, starting with ideas drawn from the literature. From that foundation, the study shaped an early draft of what's now called the Blockchain-Based Trust Framework. At its core, the model looks at how clinician trust concerns, health IT infrastructure factors, and data governance requirements all overlap, and how that overlap plays a role in whether automated clinical decisions actually get used in health insurance environments. This wasn't a one-shot design. Researchers went through multiple rounds, using participatory action research, focus groups, and semi-structured interviews to tweak and adjust as needed. What came out of that process was a framework that managed to stay true to the theory, while also making space for the messy, on-the-ground challenges that health insurance organizations actually deal with.

Validation phase:

At that point, the draft framework was taken a step further and tested in clinical environments to see how well it held up beyond theory. The approach used here draws on design science principles, first outlined by Hevner et al. [

54], and unfolds in three parts. The first phase focused on an exploratory review—not just to gather existing findings, but to uncover recurring themes and concepts that seemed central to the field. From there, the second phase aimed to build a working framework by blending academic insight with practical considerations drawn from the health insurance sector. The final phase involved empirical testing, where feedback from clinical stakeholders played a key role. Based on their input, the framework was revised, refined, and better aligned with clinical implementation needs.

- B.

Data collection

Participatory action research (PAR):

A leading health insurance organization in Turkey participated in the research. PAR workshops were conducted with cross-functional teams—including health IT administrators, compliance specialists, and claims processing managers—to evaluate existing clinical workflows, regulatory compliance challenges, and institutional readiness for blockchain implementation. A total of three workshops, each lasting approximately three hours, were organized. These workshops included structured activities such as process mapping of existing workflows, brainstorming on identified pain-points, and feedback sessions on early-stage framework prototypes.

Focus groups: Four focus groups (n=16) were conducted, with participants representing health IT, legal, compliance, and patient services departments. Discussion guides were co-developed with department heads to address clinical operations challenges, health data governance concerns, and clinician trust factors.

Table 2 presents the Focus Group Discussion Guide used in this study.

All sessions were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed using computational qualitative methods in Python.

Semi-structured interviews: Eight in-depth interviews were conducted with healthcare executives (including Chief Medical Information Officers and Data Stewardship Officers) to gather strategic insights on blockchain adoption, including capital expenditure considerations, risk mitigation strategies, and integration with existing clinical information systems.

Table 3 summarizes key findings from these interviews.

- C.

Data analysis

Transcripts from focus groups and interviews were thematically analyzed using a hybrid deductive-inductive approach [

55]. Initially, a deductive approach was used to apply a preliminary set of codes derived from the literature. Subsequently, an open coding technique was applied to capture emergent themes inductively from the data. For computational support, a widely used NLP library was utilized to perform frequency analysis of key concepts and to help visualize thematic clusters. The coding framework was iteratively refined to identify emergent themes related to health data compliance, human-technology integration, and clinician trust establishment.

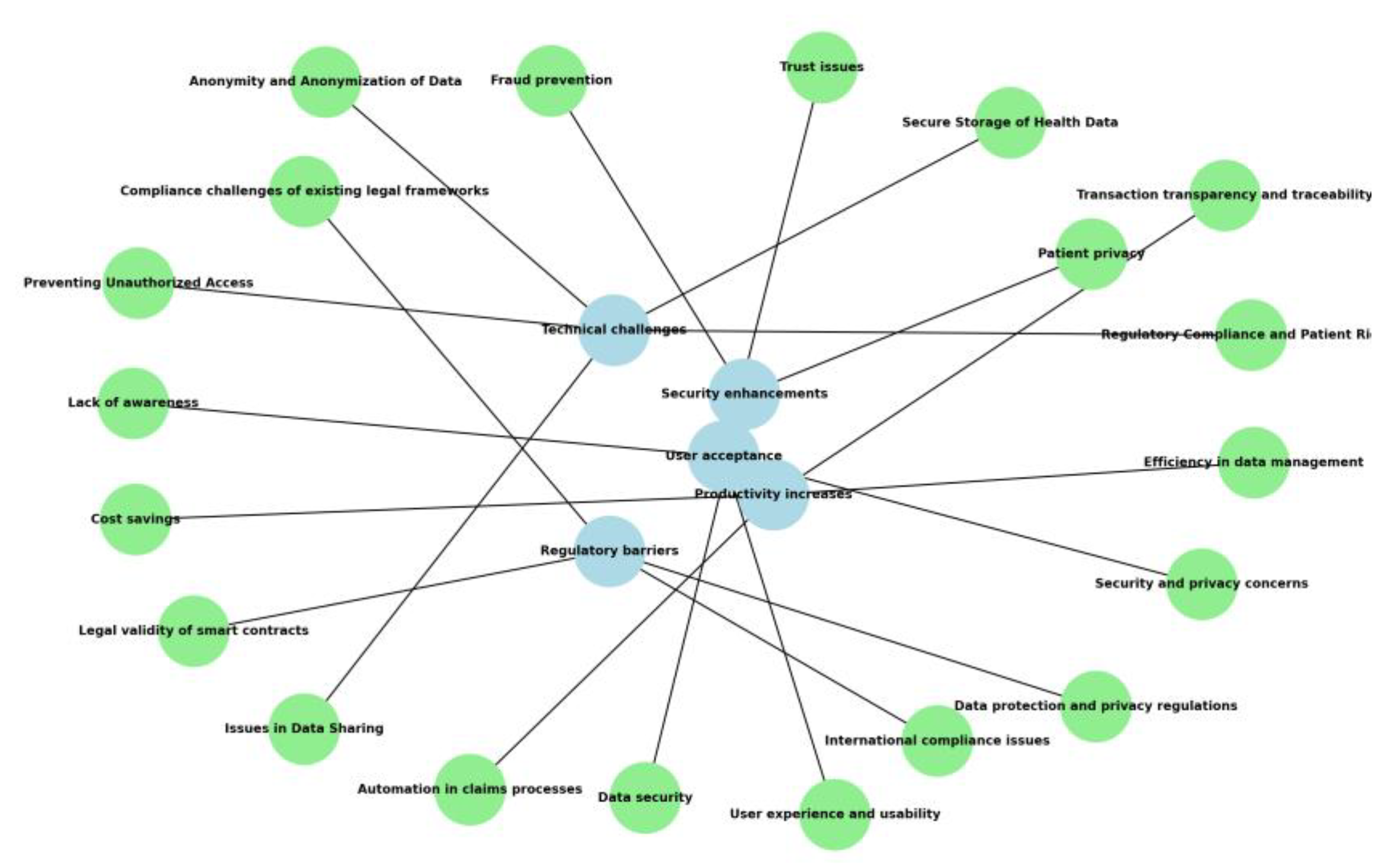

Figure 1 and

Table 4 present the analytical schema.

Inter-rater reliability was validated using Cohen's Kappa (κ = 0.86), demonstrating strong consensus between analysts [

56]. This rigorous approach ensured robust categorization of both technical and organizational factors affecting health insurance system adoption.

- D.

Validity and reliability

To strengthen internal validity, participant validation was performed by circulating preliminary results to study contributors for verification and refinement. To assess the framework’s external validity, we conducted a multi-site evaluation with additional health insurance organizations to test its generalizability across diverse clinical settings. In line with rigorous research practice, we have also explicitly documented the study's limitations—notably the potential for selection bias and a primarily EU-centric regulatory focus—to define the scope for subsequent investigations.

Ultimately, this mixed-methods approach was intentionally chosen to ensure the resulting framework possesses both theoretical rigor and direct clinical relevance. It enabled our analysis to account for the complex interplay between Health IT infrastructure requirements, data governance regulations, and the crucial institutional adoption factors that determine the success of smart contract implementation in healthcare.

4. Results

Our mixed-methods analysis yielded findings across the three core dimensions of the Blockchain-Based Trust Framework. This section presents our synthesis of these findings, examining the interplay between prospective gains in Health IT operational efficiency, the pragmatic barriers of regulatory compliance, and the sociotechnical dynamics of clinician trust.

- A.

Health IT Operational Efficiency Gains

Across our participatory design sessions and focus groups, stakeholders consistently identified delays and manual claims processing as primary sources of administrative friction within the current health insurance system. Consequently, they perceived smart contracts as a viable mechanism for mitigating these inefficiencies, pointing to their potential to enforce payer-agnostic business rules, reduce administrative overhead, and ultimately accelerate the reimbursement cycle through real-time health data exchange. Insights from the focus groups also revealed that automating claims adjudication could help streamline the process and give clinical staff more time to focus on other important responsibilities. One health IT administrator emphasized:

"We waste the most time on manual verification. For example, a reimbursement request for supportive therapy (e.g., a neutropenia drug) for an oncology patient between chemotherapy cycles required an insurance specialist to manually compare lab results containing the patient's blood values, the previous treatment protocol, and the drug's current indication. Participants noted that this process could take hours for a single patient, leading to significant delays in payments.”

A smart contract-enabled system that could instantly verify patient eligibility and coverage scope would be revolutionary. As the primary goal of this exploratory study was to develop a trust framework based on stakeholder perceptions rather than to measure return on investment, the findings are intentionally qualitative. However, the strong consensus among participants regarding potential administrative savings provides a clear, testable hypothesis for future quantitative research, where metrics such as claim processing time and error reduction rates can be empirically measured.

- B.

Health Data Governance Compliance Challenges

Participants consistently emphasized that regulatory adherence is a key factor in whether health insurance organizations adopt distributed ledger-based automated decision systems. In focus groups and interviews, healthcare compliance officers expressed concern about the tension between blockchain's cryptographic permanence and health data privacy regulations—particularly the "right to erasure" under GDPR and similar laws. One data stewardship officer noted:

"Our job is to establish a compromise between the right to change or erase data and the fact that it can't be changed. From a legal point of view, that's not up for debate."

As a practical reflection of this, one participant shared a scenario where they faced a patient's request to have test results for a genetic disease deleted from their records to avoid potential impacts on future insurance policies. This illustrates that the 'right to erasure' is not merely a theoretical legal requirement but a tangible and critical need for patients in sensitive clinical situations

On-chain/off-chain architectures, which store cryptographic hashes on-chain and protected health information (PHI) off-chain, have become a potential way to meet these two needs.

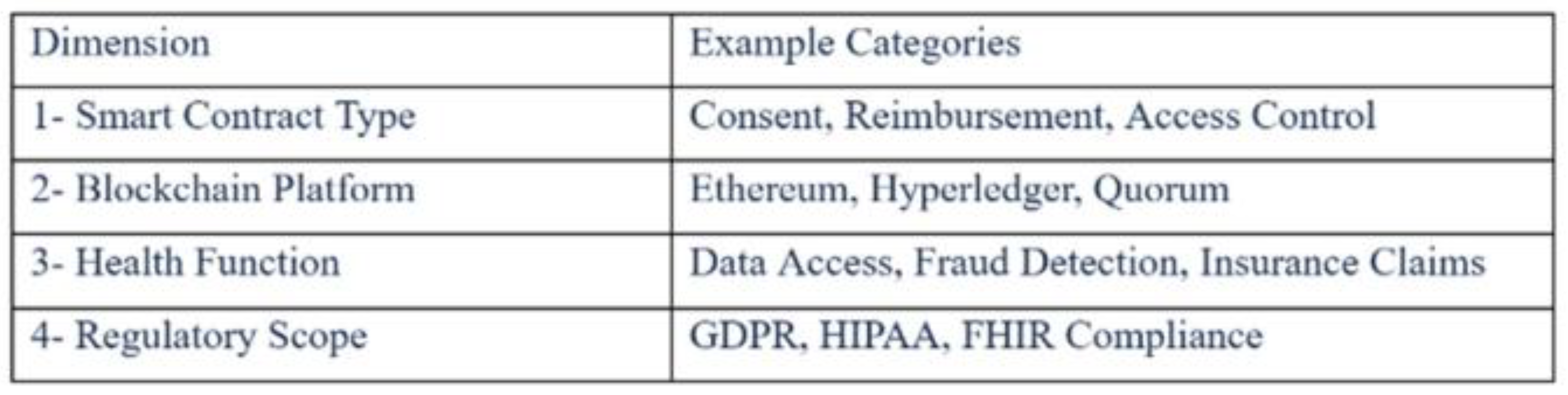

Figure 2 shows the GDPR-Aligned Compliance Model that was suggested for integrating blockchain into health insurance operations. It outlines the critical procedures to ensure both regulatory compliance and system interoperability.

Interviewees stressed that even with technical solutions, they require coordinated management between clinical IT teams and health data governance committees to be effective. When implementing blockchain solutions in health insurance environments, regulatory challenges emerge as documented in

Table 5.

- C.

Clinician Trust-Building Dynamics

Institutional trust played a significant role in how healthcare stakeholders reacted to smart contracts. Initial focus groups revealed widespread clinician skepticism, with participants expressing uncertainty about trusting algorithmic adjudication and concerns about losing oversight of coverage determinations. One physician articulated this concern by asking, 'If the system automatically rejects a non-standard but life-saving treatment protocol for a rare type of cancer, what will be our mechanism to appeal that decision instantly and effectively?' This highlights that clinicians' need for trust extends beyond mere technical accuracy to include a flexible and auditable system capable of managing exceptional cases. Some feared even minor code vulnerabilities could create unintended patient revenue cycle disruptions. However, through clinician training programs and participatory design sessions, confidence gradually increased. A patient services representative noted:

"Once we understood the contract logic validation process, most concerns were mitigated. We developed confidence in the system's ability to process claims with auditable transparency."

Participants responded favorably to compliance visualization tools, which allowed clinical end-users to monitor blockchain-executed transactions and verify outcomes. They emphasized that successful implementation requires not just technical robustness, but also perceived fairness, regulatory transparency, and user-centric design in health insurance-agnostic solutions.

- D.

Framework Validation

The Blockchain-Based Trust Framework was examined through a mix of focus groups and individual interviews with key clinical stakeholders. Participants broadly agreed that its three main layers—Regulatory Governance, Human-Technology Integration, and Clinician Trust-Building—reflected the kinds of challenges they regularly face in their work.

Regulatory Governance Layer: Health data stewardship teams were especially vocal, insisting that elements like dynamic consent protocols and full compliance with GDPR/HIPAA data sovereignty requirements aren't optional—they're fundamental to any future deployment.

Human-Technology Integration Layer: Patient-facing staff emphasized that institutional trust must be earned through transparent claim adjudication, clinician education initiatives, and continuous stakeholder engagement.

Clinician Trust-Building Layer: Healthcare administrators stressed the need for workflow-embedded training and real-time audit trail accessibility to foster adoption.

The validation showed the framework's clinical implementation value for blockchain solutions in health insurance environments.

Figure 3 illustrates the integrated model combining regulatory, technical, and human factors.

The framework's layers exhibit dynamic interdependence: Health data regulations shape technical architecture, while clinician adoption depends on both system usability and regulatory confidence. This synergy enables blockchain-enabled health informatics solutions that are compliant, clinically viable, and institutionally trusted.

- E.

Roadmap for adoption

We propose a five-phase smart contracts adoption pathway:

Rules-based automation (predefined insurance logic).

Using past claims patterns to figure out risk

Detecting anomalies in real time to stop fraud

Adaptive contracts that use reinforcement-based learning

Insurance protocols that are completely independent and easy to understand

Figure 4 shows the plan for adding blockchain-based smart contracts to health insurance systems. It shows a gradual and flexible path towards health insurance solutions that put patients first and are relevant to policy.

This roadmap operationalizes the Blockchain-Based Trust Framework, guiding health insurance organizations from basic algorithmic adjudication to advanced minimizing reliance on bilateral trust via auditable automation.

5. Discussion

This paper examines how blockchain-based smart contracts can best be utilised in health insurance systems, ensuring they adhere to rules, build user trust and integrate with existing processes. The results show that to be effective, you need to have a deep understanding of how technological, regulatory, and organisational elements all work together. This is a link that is typically ignored in the literature.

- A.

Advancing the understanding of blockchain adoption

Our study adds to the conversation about blockchain in health insurance operations by showing that just proving that a technology works isn't enough to bring about real, lasting change. Smart contracts have been shown to have benefits in the past [

3,

18] but our research shows that we need to think about how these technologies fit into the bigger picture of clinical ecosystems, health IT infrastructure, and data governance regulations. The clash between blockchain's cryptographic permanence and the GDPR's "right to be forgotten" is a clear example of this. It became a major issue, just like the ones Khan et al. [

52] and Corte-Real et al. [

9] found.

This paper backs up the idea that adopting new technology is a recursive process in which health data compliance requirements affect technical architecture decisions and vice versa. It does this by combining ideas from Institutional Theory [

10], Human-Technology Interaction Theory [

11,

35], and Trust Theory [

12]. This perspective fits health system transformation together. This idea fits with Orlikowski's [

36] idea of the duality of technology, which focuses on how technology and healthcare organizational structures change together.

The Blockchain-Based Trust Framework isn't just theoretical—it's designed to offer something practical to professionals working with blockchain in health insurance ecosystems. Whether it's payers, health IT developers, or regulatory authorities, the model organizes key considerations into three interconnected dimensions: Regulatory Governance, Human-Technology Integration, and Clinician Trust-Building. By breaking it down this way, it helps connect the dots between the health IT infrastructure being built and the data governance regulations it must comply with—while also maintaining clinician confidence.

The study suggests that regulators have to walk a fine line—protecting people’s data without totally shutting down innovation. Ideas like editable immutability or hybrid systems don’t always fit cleanly into the laws we have now, so regulators may need to think a little differently [

57]. On the development side, the research really stresses the value of putting users first. Simple dashboards, clear instructions—small things like that can actually make a big difference in how people trust and interact with systems that use automation to make decisions. The direct clinical impact of this increased trust and efficiency is significant. For patients, it can mean faster approval and access to critical treatments, such as an expensive cancer drug, thereby reducing the anxiety and financial uncertainty associated with reimbursement delays. For clinicians and staff, a transparent and auditable system minimizes time-consuming disputes arising from billing errors. This allows clinical teams to redirect their focus from administrative burdens back to what matters most: patient care.

The proposed roadmap builds on the Blockchain-Based Trust Framework by linking each stage of the process to its corresponding layer within the framework. The Regulatory Governance layer is strengthened through risk-adjusted compliance protocols and privacy-by-design approaches. The Human-Technology Integration layer is operationalized through FHIR-aligned interoperability solutions. The Clinician Trust-Building layer is strengthened through self-optimizing contracts and transparency dashboards. This integration ensures that the roadmap is not a standalone tool, but rather an implementation blueprint of the entire framework.

- B.

Reconciling Divergences in Existing Research

The findings of this research help to resolve some of the conflicts that have been noted in the literature. First, many people say that the main benefit of blockchain is that it makes things more efficient [

18], but our research shows that these gains must be balanced with regulatory compliance and building clinician trust. Second, whereas some studies only look at health data governance issues [

52] or end-user adoption [

43] our study shows that these issues are linked and should be dealt with together using integrated frameworks (

Table 6).

Moreover, the paper provides empirical evidence supporting the feasibility of on-chain/off-chain architectures and data stewardship mechanisms that can resolve the cryptographic permanence vs. right-to-erasure tension—a challenge that has been highlighted but not sufficiently operationalized in previous research [

9,

33,

58].

6. Conclusions and Limitations

This paper developed and validated the Blockchain-Based Trust Framework to address the fragmented approaches that often isolate technical, regulatory, and trust dimensions in blockchain adoption within health insurance. This study shows that the effective use of smart contracts depends on the dynamic interaction between health IT innovation, data governance compliance (such as GDPR and HIPAA), and clinician trust-building efforts. It used a mixed-methods approach that included a systematic evidence synthesis, participatory design research, focus groups, and semi-structured interviews.

To reconcile GDPR's requirements (e.g., right to erasure under Article 17) with blockchain's cryptographic permanence, policymakers should recognize on-chain/off-chain architectures (e.g., off-chain PHI storage with on-chain hashes) and auditable immutability mechanisms. Additionally, dynamic consent protocols via smart contracts could bridge compliance gaps, while interoperability standards (e.g., FHIR-blockchain integration) must be formalized to enable cross-border health data exchange. These adaptations would align regulatory frameworks with technological capabilities without compromising data subject rights. Beyond these policy considerations, the framework is presented not as a mere theoretical construct, but as a testable blueprint for real-world application. The next logical step is its operationalization within a controlled pilot study, conducted in partnership with a healthcare provider or payer organization. Such a pilot would enable the empirical measurement of key performance indicators—including claims processing time, error reduction rates, and clinician trust scores—thereby transitioning the framework from a validated model to an evidence-based, scalable solution.

This study is mostly about the European GDPR regulatory environment, but more research should be done to adapt and test the framework in other important areas, such as the US (HIPAA) and the Asia Pacific markets. This expansion would enhance the framework's global applicability. The proposed framework offers a holistic implementation roadmap for payers, health IT developers, and regulators to navigate these complexities effectively. For the healthcare industry, the framework offers a tangible pathway to develop competitive, patient-centric insurance products, while for policymakers, it presents a balanced model to encourage technological advancement without compromising on fundamental data protection rights.

Future research should explore the framework's generalizability across different regulatory contexts and investigate emerging trends, such as AI-augmented smart contracts. In particular, AI-enhanced decision systems could be integrated into the proposed framework by automating claims fraud analytics, risk-adjusted pricing, and personalized coverage algorithms based on real-time clinical data insights. These integrations could further improve operational efficiency and user trust.

Overall, this paper contributes to advancing digital health transformation in health insurance ecosystems. It bridges technological, regulatory, and user adoption considerations in a coherent and actionable manner.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Concepts and Quotes from Articles.

Table A1.

Concepts and Quotes from Articles.

| Concept |

Author(s) |

Sentence from article |

| Technical challenges |

|---|

| Regulatory Compliance and Patient Rights |

[22] Arbabi et al. (2023) |

"The use of blockchain solutions in healthcare necessitates a comprehensive discussion of compliance with privacy-related regulations, such as the general data protection regulation (GDPR) and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)." |

| Issues in Data Sharing |

[24] Li et al. (2020) |

"In this article, we address the challenges of data interoperability and regulatory compliance when designing and deploying healthcare applications in a heterogeneous home-edge-cloud environment." |

| Issues in Data Sharing |

[22] Arbabi et al. (2023) |

"The existing data storage and exchange solutions in the healthcare domain exhibit several challenges related to, e.g., data security, patient privacy, and interoperability." |

| Issues in Data Sharing |

[23] Geng et al. (2024) |

"The existence of discrete platforms for different services has cultivated data silos among healthcare service providers, creating an impediment to service quality." |

| Preventing Unauthorized Access |

[29] Al Omar et al. (2021) |

"Smart contracts can prevent unauthorized access and enhance data privacy." |

| Secure Storage of Health Data |

[22] Arbabi et al. (2023) |

"Blockchain technology is considered a salient facilitator for secure and efficient health data sharing." |

| Anonymity and Anonymization of Data |

[29] Al Omar et al. (2021) |

"We propose a transparent and privacy-preserving healthcare platform." |

| Scalability |

[50] Sai et al. (2023) |

"Blockchain (BC) and artificial intelligence (AI) technologies have significant potential for secure and scalable healthcare solutions." |

| Regulatory barriers |

| Legal validity of smart contracts |

[22] Arbabi et al. (2023) |

"The early stages of smart contracts’ use and the legal validity of these contracts pose significant challenges that lead to debate and regulatory uncertainty." |

| Compliance challenges of existing legal frameworks |

[22] Arbabi et al. (2023) |

"Compliance with existing legal frameworks is a major challenge for blockchain-based healthcare solutions." |

| International compliance issues |

[22] Arbabi et al. (2023) |

"Patients’ interactions with each other and with healthcare providers may cause violation of specific privacy requirements." |

| Data protection and privacy regulations |

[22] Arbabi et al. (2023) |

"The existing data storage and exchange solutions in the healthcare domain exhibit several challenges related to, e.g., data security, patient privacy, and interoperability." |

| Data protection and privacy regulations |

[29] Al Omar et al. (2021) |

"Data security and patient privacy are critically important in the healthcare sector." |

| User acceptance |

| Trust issues |

[23] Geng et al. (2024) |

"An integrated healthcare service system grounded in blockchain technology... aims to establish a seamless and trustworthy environment for data sharing among diverse participants within the healthcare community." |

| Trust issues |

[22] Arbabi et al. (2023) |

"Because of blockchain’s unique characteristics such as decentralization and trustlessness, it is envisioned that health data sharing can be facilitated in a secure and efficient manner." |

| Trust issues |

[23] Geng et al. (2024) |

"This article introduces an integrated healthcare service system grounded in blockchain technology, which aims to establish a seamless and trustworthy environment for data sharing among diverse participants within the healthcare community." |

| Lack of awareness |

[6]

Khatri et al. (2021) |

"It is mentioned that blockchain is still in its early stages of use in the healthcare sector, with a lack of awareness." |

| User experience and usability |

[23] Geng et al. (2024) |

"The proposed system accommodates an array of ancillary services, contributing to an enriched experience for both patients and healthcare providers." |

| Security and privacy concerns |

[22] Arbabi et al. (2023) |

"The existing data storage and exchange solutions in the healthcare domain exhibit several challenges related to, e.g., data security, patient privacy, and interoperability." |

| Productivity increases |

| Transaction transparency and traceability |

[22] Arbabi et al. (2023) |

"Blockchain technology, due to its unique features such as decentralization, trustlessness, immutability, traceability, and transparency, is considered a salient facilitator for secure and efficient health data sharing." |

| Transaction transparency and traceability |

[6]

Khatri et al. (2021) |

"explored the use of blockchain and aimed to provide a DSCSA (Drug Supply Chain Security Act) compliant solution for increasing interoperability in the market. Khatri et al. (2021)

aimed to increase the traceability of blockchain-based pharmaceutical industries." |

| Automation in claims processes |

[43] Alnuaımi et al. (2022) |

"The current legacy system used in processing health insurance claims causes a huge amount of financial loss every year due to fraud claims." (While not directly stating automation, it implies the benefit of a blockchain-based system in reducing fraud, which is often a goal of automation.) |

| Automation in claims processes |

[59] Elhence et al. (2023) |

“Blockchain may eliminate any third-party organizations and make the complete process safer, easier, and more efficient." |

| Automation in claims processes / Efficiency in data management |

[59] Elhence et al. (2023) |

"We focus on establishing a rapid and cost-effective framework for the health insurance market, based on machine learning and blockchain technology. By developing a smart contract, blockchain may eliminate any third-party organizations and make the complete process safer, easier, and more efficient." |

| Efficiency in data management |

[22] Arbabi et al. (2023) |

"Blockchain offers solutions to the challenges of data collection, storage, and sharing within the healthcare domain." |

| Efficiency in data management |

[24] Li et al. (2020) |

"The ChainSDI framework leverages the blockchain technique along with abundant edge computing resources to manage secure data sharing and computing on sensitive patient data." |

| Cost savings |

[59] Elhence et al. (2023) |

"The current insurance system is very expensive... in this article, we focus on establishing a rapid and cost-effective framework for the health insurance market, based on machine learning and blockchain technology." |

| Cost savings |

[60] Kapadiya et al. (2022) |

"The detection of health insurance fraud is crucial to prevent huge financial losses caused by fraudulent activities." (Preventing fraud indirectly leads to cost savings.) |

| Security enhancements |

| Fraud prevention |

[43] Alnuaımi et al. (2022) |

"The current legacy system used in processing health insurance claims causes a huge amount of financial loss every year due to fraud claims." |

| Fraud prevention |

[60] Kapadiya et al. (2022) |

"The detection of health insurance fraud..." |

| Patient privacy |

[22] Arbabi et al. (2023) |

"The existing data storage and exchange solutions... exhibit several challenges related to... patient privacy..." |

| Patient privacy |

[29] Al Omar et al. (2021) |

"In this paper, we propose a transparent and privacy-preserving healthcare platform for smart cities." |

| Patient privacy |

[23] Geng et al. (2024) |

"The intrinsic attributes of blockchain... safeguard patient privacy." |

| Data security |

[22] Arbabi et al. (2023) |

"Blockchain technology is considered a salient facilitator for secure and efficient health data sharing." |

| Data security |

[23] Geng et al. (2024) |

"The intrinsic attributes of blockchain, such as data immutability and traceability, serve to mitigate the risk of data tampering and leakage, thereby ensuring data security." |

| Data security |

[50] Sai et al. (2023) |

"The confluence of Blockchain and Artificial Intelligence technologies has multiple use cases for secure and scalable healthcare solutions." |

Figure A1.

Conceptual Roadmap.

Figure A1.

Conceptual Roadmap.

References

Serkan Türkeli received the bachelor’s degree in computer engineering from Bahçeşehir University, and the master’s and Ph.D. degrees in management engineering from Istanbul Technical University. He received his associate professorship in health informatics from Marmara University. His research interests include object-oriented programming, biodesign, optimization, health informatics and management information system.

- Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC, USA: National Academies Press, 2001.

- A. A. Deshmukh, P. A. A. Deshmukh, P. Patel, P. Singh, and R. Sharma, “Event-based smart contracts for automated claims processing and payouts in smart insurance,” Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl., vol. 15, no. 4, 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Pham, T. H. L. Pham, T. H. Tran, Y. Nakashima, 2018. “A secure remote healthcare system for hospital using blockchain smart contract,” In 2018 IEEE Globecom Workshops (GC Wkshps), 1–6. IEEE, 2018.

- R. Zhang, R. Xue, and L. Liu, “Security and privacy for healthcare blockchains,” IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput., vol. 15, no. 6, pp. 3668–3686, 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Dhiman, A. Bonkra, A. Kaur, and M. Singh, “Exploring the terrain: mapping keyword co-occurrence in blockchain and smart contracts for healthcare,” in Proc. 2023 IEEE 5th Int. Conf. Adv. Electron., Comput. Commun. Technol. (ICAECC), pp. 1–5, IEEE, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Khatri, F. A. Alzahrani, M. T. J. Ansari, A. Agrawal, R. Kumar, and R. A. Khan, “A systematic analysis on blockchain integration with healthcare domain: scope and challenges,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 84666–84687, 2021. [CrossRef]

- V. Venkatesh, M. G. Morris, G. B. Davis, and F. D. Davis, “User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view,” MIS Q., vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 425–478, 2003. [CrossRef]

- S. P. Novikov, O. D. Kazakov, N. A. Kulagina, and A. I. Ivanov, “Blockchain and smart contracts in a decentralized health infrastructure,” in Proc. 2018 IEEE Int. Conf. Qual. Manag., Transport Inf. Secur., and Inf. Technol. (IT&QM&IS), pp. 697–703, IEEE, 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Corte-Real, T. Nunes, and P. R. Da Cunha, “Reflections about blockchain in health data sharing: navigating a disruptive technology,” Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, vol. 21, no. 2, p. 230, 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. R. Scott, “Institutional theory: contributing to a theoretical research program,” in Great Minds in Management: The Process of Theory Development, K. G. Smith and M. A. Hitt, Eds. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford Univ. Press, 2005, pp. 460–484.

- A. Norman, The Design of Everyday Things. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press, 2013.

- N. Luhmann, Trust and Power. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, 2018.

- M. M. Salim and J. H. Park, “Federated learning-based secure electronic health record sharing scheme in medical informatics,” IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform., vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 617–624, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Saini, Q. Zhu, N. Singh, and G. Srivastava, “A smart-contract-based access control framework for cloud smart healthcare system,” IEEE Internet Things J., vol. 8, no. 7, pp. 5914–5925, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Shah, C. Patel, J. Patel, and R. Sharma, “Utilizing blockchain technology for healthcare and biomedical research: a review,” Cureus, Oct. 2024, Art. no. e72040. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Omar, A. Shaheen, M. Khan, and S. Tariq, “A transparent and privacy-preserving healthcare platform with novel smart contract for smart cities,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 90738–90749, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Chondrogiannis, V. Andronikou, E. Karanastasis, and N. Karacapilidis, “Using blockchain and semantic web technologies for the implementation of smart contracts between individuals and health insurance organizations,” Blockchain: Res. Appl., vol. 3, no. 2, p. 100049, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Q. Zhang, S. Khan, S. U. Khan, and M. Ahmad, “Understanding blockchain technology adoption in operation and supply chain management of Pakistan: extending UTAUT model with technology readiness, technology affinity and trust,” SAGE Open, vol. 13, no. 4, p. 21582440231199320, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. S. S. Mishra, “Study on blockchain-based healthcare insurance claim system,” in Proc. 2021 Asian Conf. Innov. Technol. (ASIANCON), pp. 1–4, IEEE, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Kaafarani, L. Ismail, and O. Zahwe, “Automatic recommender system of development platforms for smart contract–based health care insurance fraud detection solutions: taxonomy and performance evaluation,” J. Med. Internet Res., vol. 26, p. e50730, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Amin, R. Shah, H. Tummala, M. Alotaibi, M. H. Rehman, and E. Ahmed, “Utilizing blockchain and smart contracts for enhanced fraud prevention and minimization in health insurance through multi-signature claim processing,” in Proc. 2024 Int. Conf. Emerg. Trends Netw., Comput. Commun. (ETNCC), pp. 1–9, IEEE, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Arbabi, C. Lal, N. R. Veeraragavan, D. Marijan, J. F. Nygård, and R. Vitenberg, “A survey on blockchain for healthcare: challenges, benefits, and future directions,” IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 386–424, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Q. Geng, Z. Chuai, and J. Jin, “An integrated healthcare service system based on blockchain technologies,” IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst., vol. 11, no. 5, pp. 6278–6290, 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. Li, X. Liu, F. R. Yu, J. Chen, Y. Zhang, and V. C. M. Leung, “ChainSDI: a software-defined infrastructure for regulation-compliant home-based healthcare services secured by blockchains,” IEEE Syst. J., vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 2042–2053, 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Sadath, D. Mehrotra, and A. Kumar, “Scalability performance analysis of blockchain using hierarchical model in healthcare,” Blockchain Healthc. Today, vol. 7, p. 10-30953, 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. Tarannum and S. Abidin, “A patient-centric blockchain-based framework with layer-2 integration for secure and scalable healthcare data management,” in Proc. 2025 3rd Int. Conf. Intell. Syst., Adv. Comput. Commun. (ISACC), pp. 1220–1225, IEEE, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- K. N. Griggs, O. Ossipova, C. P. Kohlios, A. N. Baccarini, E. A. Howson, and T. Hayajneh, “Healthcare Blockchain system using smart contracts for secure automated remote patient monitoring,” J. Med. Syst., vol. 42, no. 7, p. 130, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Bazel, F. Mohammed, M. Ahmad, et al., “Blockchain technology adoption in healthcare: an integrated model,” Sci. Rep., vol. 15, p. 14111, 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Al Omar, M. Z. A. Bhuiyan, A. Basu, S. Kiyomoto, and M. A. Rahman, “Privacy-friendly platform for healthcare data in cloud based on blockchain environment,” Future Gener. Comput. Syst., vol. 114, pp. 643–654, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Sahu, S. Choudhari, and S. Chakole, “The use of blockchain technology in public health: lessons learned,” Cureus, Jun. 2024, Art. no. e63198. [CrossRef]

- G. De Moraes Rossetto, C. Sega, and V. R. Q. Leithardt, “An architecture for managing data privacy in healthcare with blockchain,” Sensors (Basel), vol. 22, no. 21, p. 8292, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Müller-Bloch and Ø. Sæbø, “The ‘hijacking’ of the Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems: journal hijacking and the dark side of digitalization in academia,” Inf. Syst. J., vol. 33, no. 6, pp. 1251–1261, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. Xu, E. Zheng, H. Han, and T. Wang, “A secure healthcare data sharing scheme based on two- dimensional chaotic mapping and blockchain,” Sci. Rep., vol. 14, no. 1, p. 23470, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Barnes, “A meta-analysis of blockchain acceptance research and new theory directions,” in Proc. 2024 IEEE ANDESCON, pp. 1–6, IEEE, 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Trist and K. W. Bamforth, “Some social and psychological consequences of the longwall method of coal-getting,” Hum. Relat., vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 3–38, 1951. [CrossRef]

- W. J. Orlikowski, “The duality of technology: rethinking the concept of technology in organizations,” Organ. Sci., vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 398–427, 1992. [CrossRef]

- M. B. Buntin, M. F. Burke, M. C. Hoaglin, and D. Blumenthal, “The benefits of health information technology: a review of the recent literature shows predominantly positive results,” Health Aff., vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 464–471, 2011. [CrossRef]

- R. Vest and L. D. Gamm, “Health information exchange: persistent challenges and new strategies,” J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc., vol. 17, no. 3, p. 288, 2010. [CrossRef]

- P. Esmaeilzadeh and T. Mirzaei, “The potential of blockchain technology for health information exchange: experimental study from patients’ perspectives,” J. Med. Internet Res., vol. 21, no. 6, p. e14184, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. E. Chang and Y. Chen, “Blockchain in health care innovation: literature review and case study from a business ecosystem perspective,” J. Med. Internet Res., vol. 22, no. 8, p. e19480, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Negri-Ribalta, R. Noel, O. Pastor, and C. Salinesi, “An empirical study on socio-technical modeling for interdisciplinary privacy requirements,” in Cooperative Information Systems: CoopIS 2023 (Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 14353), M. Sellami, M.-E. Vidal, B. van Dongen, W. Gaaloul, and H. Panetto, Eds. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2024, pp. 137–156. [CrossRef]

- M. Koscina, D. Manset, C. Negri-Ribalta, and O. Perez, “Enabling trust in healthcare data exchange with a federated blockchain-based architecture,” in Proc. IEEE/WIC/ACM Int. Conf. Web Intell. – Companion Volume, pp. 231–237, 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Alnuaimi, A. Alshehhi, K. Salah, R. Jayaraman, I. Yaqoob, and M. Omar, “Blockchain-based processing of health insurance claims for prescription drugs,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 118093–118107, 2022. [CrossRef]

- D.-C. Toader, C. M. Rădulescu, and C. Toader, “Investigating the adoption of blockchain technology in agri-food supply chains: analysis of an extended UTAUT model,” Agriculture (Basel), vol. 14, no. 4, p. 614, 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Khazaei, “Integrating cognitive antecedents to UTAUT model to explain adoption of blockchain technology among Malaysian SMEs,” JOIV: Int. J. Inform. Vis., vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 85–90, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Saurabh and K. Dey, “Blockchain technology adoption, architecture, and sustainable agri-food supply chains,” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 284, p. 124731, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Queiroz, S. Fosso Wamba, M. De Bourmont, and A. Gunasekaran, “Blockchain adoption in operations And supply chain management: empirical evidence from an emerging economy,” Int. J. Prod. Res., vol. 59, no. 20, pp. 6087–6103, 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Liu and Z. Ye, “Empirical research on the blockchain adoption – based on TAM,” Appl. Econ., vol. 53, no. 37, pp. 4263–4275, 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Ullah, M. Usman, H. A. Khattak, and N. Tariq, “Hybridizing cost saving with trust for blockchain technology adoption by financial institutions,” Telemat. Inform. Rep., vol. 6, p. 100008, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Sai, V. Chamola, K.-K. R. Choo, B. Sikdar, and J. J. P. C. Rodrigues, “Confluence of blockchain and artificial intelligence technologies for secure and scalable healthcare solutions: a review,” IEEE Internet Things J., vol. 10, no. 7, pp. 5873–5897, 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. Gatteschi, F. Lamberti, C. Demartini, and C. Pranteda, “Blockchain and smart contracts for insurance: is the technology mature enough?,” Future Internet, vol. 10, no. 2, p. 20, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. N. Khan, F. Loukil, C. Ghedira-Guegan, K. Boukadi, and D. Benslimane, “Blockchain smart contracts: applications, challenges, and future trends,” Peer-to- Peer Netw. Appl., vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 2901–2925, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Page, J. E. McKenzie, P. M. Bossuyt, I. Boutron, T. C. Hoffmann, C. D. Mulrow, et al., “Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: development of the PRISMA 2020 statement,” J. Clin. Epidemiol., vol. 134, pp. 103–112, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. R. Hevner, S. T. March, J. Park, and S. Ram, “Design science in information systems research,” MIS Q., vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 75–105, 2004. [CrossRef]

- V. Braun and V. Clarke, “Using thematic analysis in psychology,” Qual. Res. Psychol., vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 77– 101, 2006. [CrossRef]

- M. L. McHugh, “Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic,” Biochem. Medica, vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 276–282, 2012, PMID: 23092060; PMCID: PMC3900052.

- Magri, D. Venturi, and E. Andrade, “Redactable blockchain–or–rewriting history in bitcoin and friends,” in Proc. 2017 IEEE Eur. Symp. Secur. Privacy (EuroS&P), pp. 111–126, IEEE, Apr. [CrossRef]

- M. Khatun, R. A. Islam, and S. Islam, “B-SAHIC: a blockchain-based secured and automated health insurance claim processing system,” J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst., 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Elhence, A. Goyal, V. Chamola, and B. Sikdar, “A blockchain and ML-based framework for fast and cost- effective health insurance industry operations,” IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst., vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 1642– 1654, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kapadiya, U. Patel, R. Gupta, M. D. Alshehri, S. Tanwar, G. Sharma, and P. N. Bokoro, “Blockchain and AI-empowered healthcare insurance fraud detection: an analysis, architecture, and future prospects,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 79606–79629, 2022. [CrossRef]

Short Biography of Authors

|

Kenan K. Kurt received the bachelor’s degree in control and automation engineering from Istanbul Technical University and the master’s degree in biomedical engineering from Boğaziçi University. He is currently PhD candidate in Health Management from Marmara University, Faculty of Health Sciences and the CEO of TESODEV company. His research interests include cloud computing, biodesign, engineering management, health informatics and management information system. |

|

Meral Timurtaş PhD, received her undergraduate (2014), Master’s (2018), and Ph.D. (2024) degrees in Health Management from Marmara University, Faculty of Health Sciences. She is currently affiliated with the same faculty as a Research Asst. Dr. at Marmara University, Faculty of Health Sciences. Her research interests focus on health management, healthcare quality, management information system, health informatics and strategic planning in health systems. |

|

Sevcan Pınar PhD, graduated from Istanbul University, Faculty of Business Administration, completed her Master’s degree, Faculty of Business, at the same university. She received her Ph.D. at Marmara University, in Management and Organization Department. Currently, she is an Assistant Professor of Business Administration, Istanbul Galata University Faculty of Art and Social Sciences and a part-time lecturer at Bahçesehir University Faculty of Postgraduate Education. Her fields of study are management, management information system, technology and innovation management. |

|

Fatih Ozaydin completed his B.S. in Computer Science and Engineering with Minor in Physics in 2003, and M.S. in Electronics Engineering in 2005 at Isik University, Turkey. As a Japanese Government (MEXT) scholarship recipient, he completed his Ph.D. in Quantum Information and Quantum Optics Lab. at Osaka University, Japan in 2010. During his M.S. studies, he worked as a Research and Teaching Assistant in Department of Physics, Isik University. He worked as a Software Engineer at YALTES Inc. in the Integrated Maritime Surveillance Systems Project for the Turkish Navy; as an Assistant Professor in Department of Computer Engineering, Okan University; as an Assistant and Associated Professor in Department of Information Technologies, Isik University; and as the Vice Director of Technology Transfer Office of Isik University. As a Visiting Professor, he worked at Micro/Nano Photonics Lab., Washington University in St. Louis, USA; and at Photon Science Center, The University of Tokyo. He worked as the Manager of IT Department of Has-Nihon Trading Co. Ltd. Currently, he is a Professor of Quantum Technologies and Data Management at Tokyo International University; a Senior Scientist and Board Member at Nanoelectronics Research Center in Istanbul, Turkey; an Associate Editor of Quantum Information Processing journal; and an official collaborator of Future Circular Collider (FCC) Project of CERN. His research interests focus on Quantum Science and Technologies, Blockchain and AI. |

|

Serkan Türkeli received the bachelor’s degree in computer engineering from Bahçeşehir University, and the master’s and Ph.D. degrees in management engineering from Istanbul Technical University. He received his associate professorship in health informatics from Marmara University. His research interests include object-oriented programming, biodesign, optimization, health informatics and management information system. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).