Submitted:

03 September 2025

Posted:

03 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background/Objectives: Uptake of remote cochlear implant (CI) services is feasible in clinical studies, but implementation into regular clinical practice is limited. Effective implementation requires demonstration of at least equivalent outcomes to in-person care. Use of outcome measures that are relevant, and sensitive to both modes of service facilitates evidence-based provision of CI services. Following on from our study that developed a core outcome domain set (CODS), this study aimed to 1) review current awareness and use of outcome measures used clinically, in-person or remotely, and 2) provide recommendations for a pragmatic core outcome set (COS) to assess remote technologies for CI users. Methods: Expert Australian/New Zealand clinical CI professionals (n=20) completed an online survey regarding use of, and familiarity with, pre-identified outcome measures mapping to the previously identified CODS. Respondents rated the outcomes’ usefulness, ease of use, trustworthiness, and recommendation for future use. Stakeholder workshops (clinician, n=3, CI users n=4) finalised recommendations. Results: Four of the six most regularly used and familiar measures were speech perception tests: BKB-A sentences, CNC words, CUNY sentences, and AB words. The long- and short-form Speech, Spatial, and Qualities of Hearing Scales (SSQ/SSQ-12) were the top-ranked patient reported outcome measures (PROMs). These outcome measures were also perceived as the most trustworthy, easy to use, and likely to be used if recommended. Conclusions: A pragmatic COS, relevant to both remote and in-person delivery of CI services, including recommendations for measurement of service, clinician-measured and patient-reported outcomes and how these might be developed in future is recommended.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

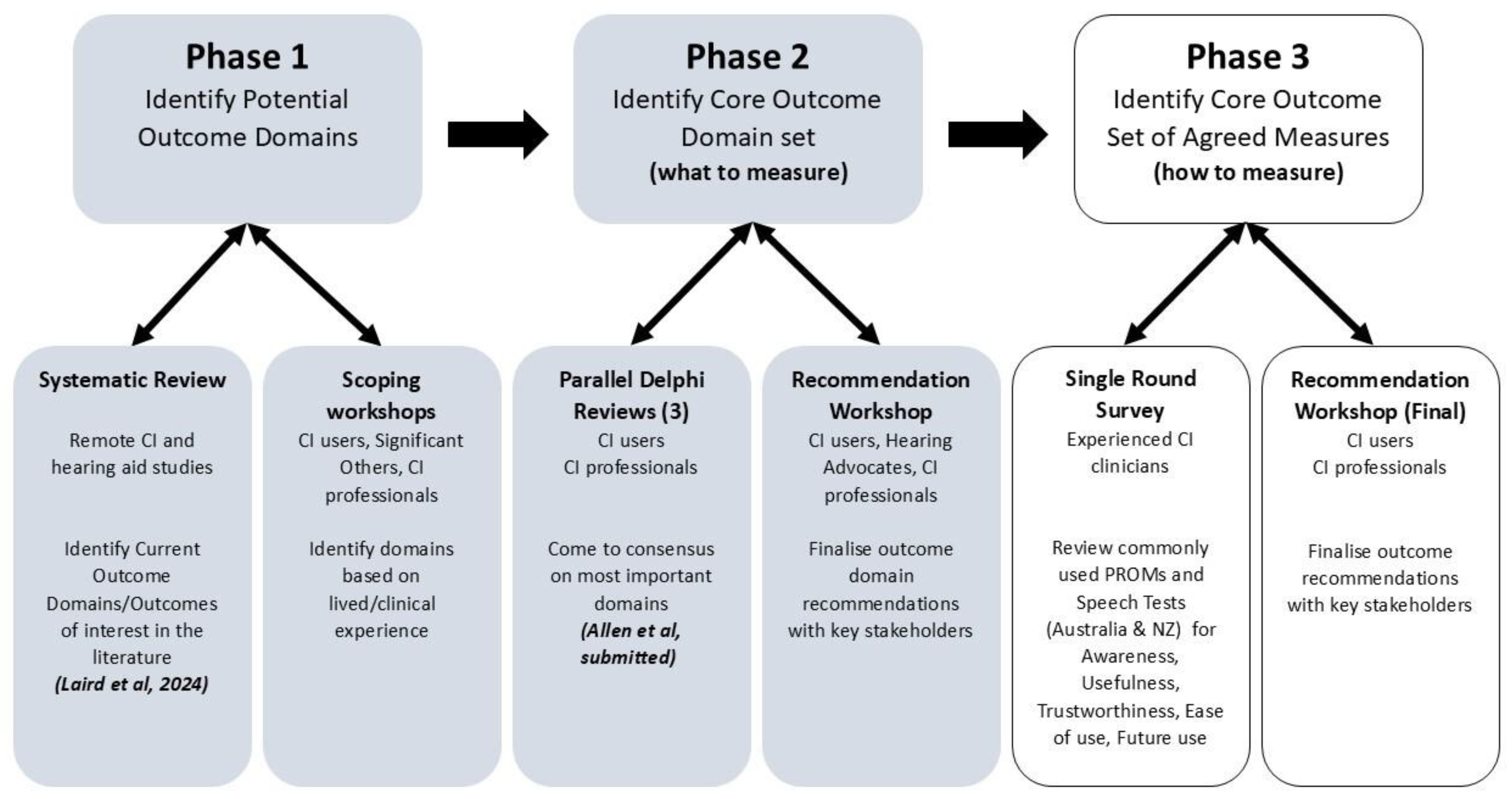

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Single Round Online Survey

- This measure is easy to use in clinical practice (ease of use)

- This measure gives results that are trustworthy/believable

- This measure gives results that are useful in clinical practice

- I would use this measure in clinical practice if it were recommended to me

2.2. Online Final Recommendation Workshops

3. Results

3.1. Single Round Online Survey

3.1.1. Familiarity Ratings (Speech Perception and PROM Measures)

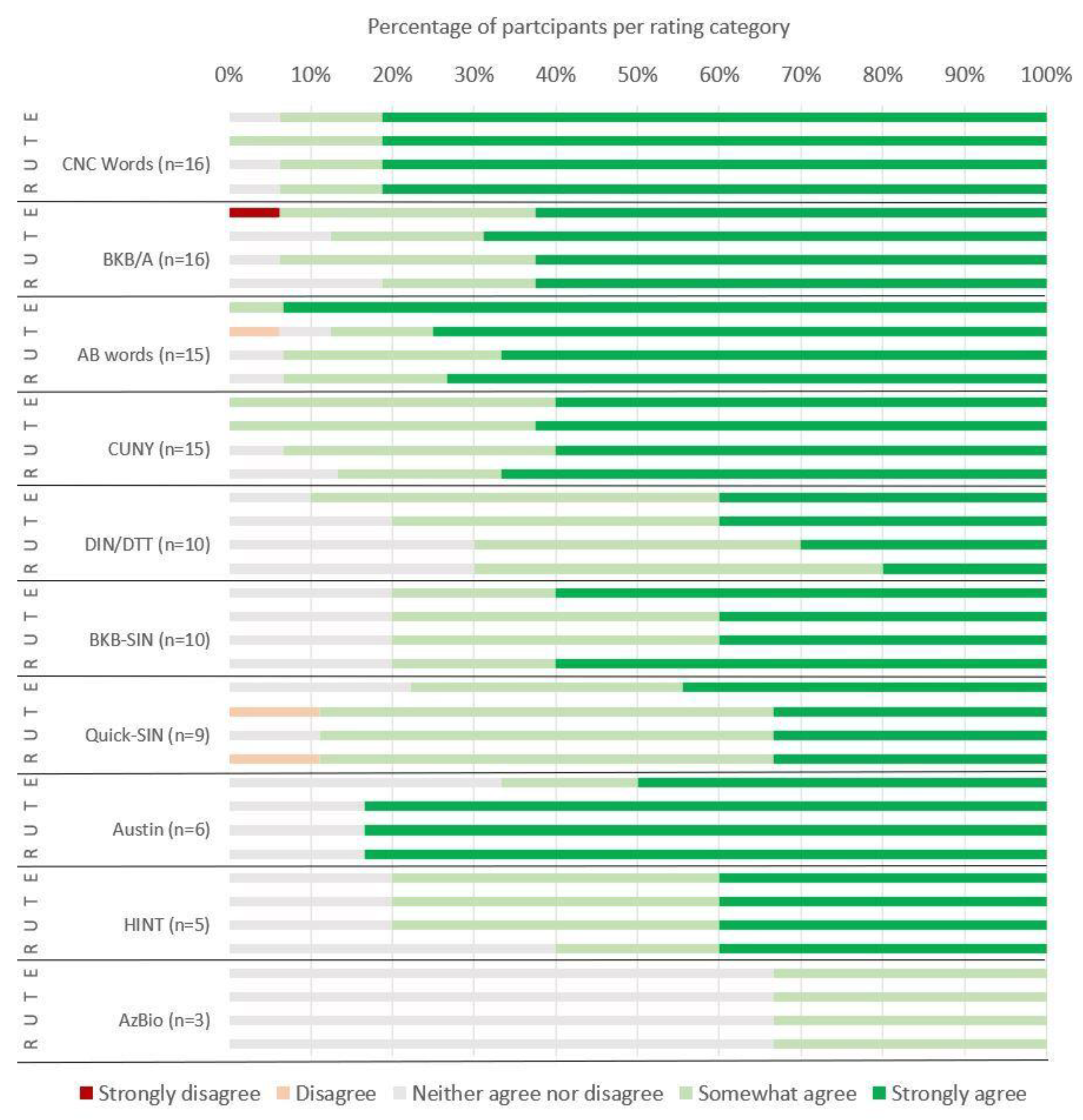

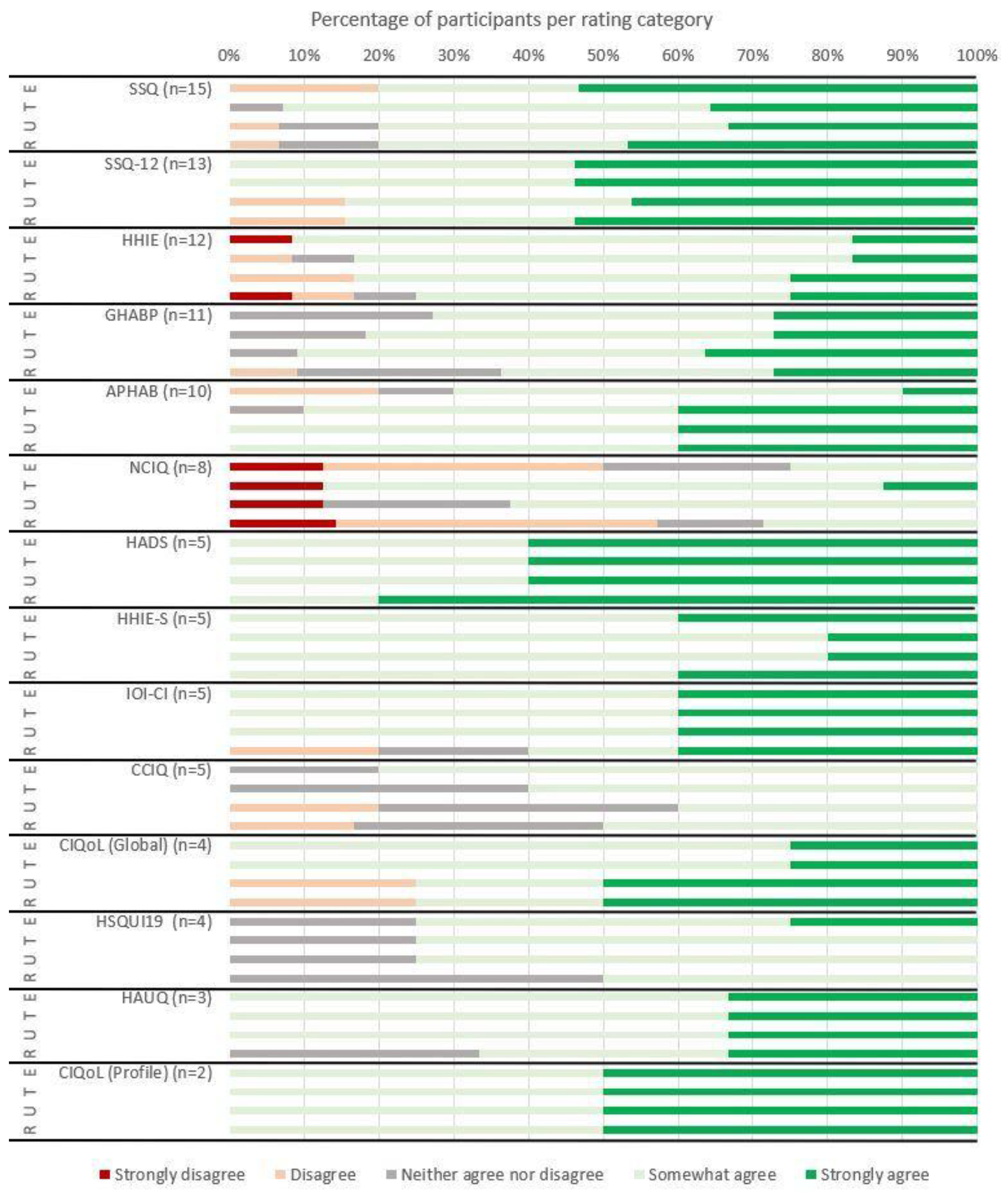

3.1.2. Ease of Use, Trustworthiness, Usefulness and Likely Recommendation to Use Ratings

3.1.3. Free Text Responses

3.2. Final Recommendation Workshops

4. Discussion

Recommended Interim, Pragmatic COS

4.1.1. Service Outcomes

4.1.2. Clinically-Measured Outcomes

4.1.3. Patient Reported Outcome Measures

4.1.4. Future Emerging Domains

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CI | Cochlear Implant |

| CODS | Core Outcome Domain Set |

| COS | Core Outcome Set |

| PROM | Patient Reported Outcome Measure |

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

| ICF | International classification of Functioning, Disability and Health framework |

| COMET | Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials |

References

- Ferguson, M.A., et al., Remote Technologies to Enhance Service Delivery for Adults: Clinical Research Perspectives. Semin Hear, 2023. 44(3): p. 328-350.

- Kim, J., et al., A Review of Contemporary Teleaudiology: Literature Review, Technology, and Considerations for Practicing. J Audiol Otol, 2021. 25(1): p. 1-7.

- Luryi, A.L., et al., Cochlear Implant Mapping Through Telemedicine-A Feasibility Study. Otol Neurotol, 2020. 41(3): p. e330-e333.

- Maruthurkkara, S., et al., Remote check test battery for cochlear implant recipients: proof of concept study. Int J Audiol, 2022. 61(6): p. 443-452.

- Schepers, K., et al., Remote programming of cochlear implants in users of all ages. Acta Otolaryngol, 2019. 139(3): p. 251-257.

- Cullington, H., et al., Feasibility of personalised remote long-term follow-up of people with cochlear implants: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open, 2018. 8(4): p. e019640.

- Maruthurkkara, S., S. Case, and R. Rottier, Evaluation of Remote Check: A Clinical Tool for Asynchronous Monitoring and Triage of Cochlear Implant Recipients. Ear Hear, 2022. 43(2): p. 495-506.

- Philips, B., et al., Empowering Senior Cochlear Implant Users at Home via a Tablet Computer Application. Am J Audiol, 2018. 27(3S): p. 417-430.

- Carner, M., et al., Personal experience with the remote check telehealth in cochlear implant users: from COVID-19 emergency to routine service. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol, 2023. 280(12): p. 5293-5298.

- Nassiri, A.M., et al., Implementation Strategy for Highly-Coordinated Cochlear Implant Care With Remote Programming: The Complete Cochlear Implant Care Model. Otol Neurotol, 2022. 43(8): p. e916-e923.

- Nittari, G., et al., Telemedicine in the COVID-19 Era: A Narrative Review Based on Current Evidence. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2022. 19(9).

- Chong-White, N., et al., Exploring teleaudiology adoption, perceptions and challenges among audiologists before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Digital Health, 2023. 1(24).

- Lilies, A., et al., Independent Evaluation of CHOICE 2021, P. Darnton, Editor. 2021, The Health Foundation: Wessex Academic Health Science Network, Innovation Centre, 2 Venture Road, Southampton Science Park, SO16 7NP. p. 1-53.

- Sucher, C., et al., Patient preferences for Remote cochlear implant management: A discrete choice experiment. PLoS One, 2025. 20(6): p. e0320421.

- Barreira-Nielsen, C.S.C. and L.S. Campos, Implementation of the hybrid teleaudiology model: acceptance, feasibility and satisfaction in a cochlear implant program. Audiol., Commun. Res, 2022. 27.

- Department of Health, V., Virtual Care Operational Framework, V. Department of Health, Editor. 2023.

- Granberg, S., et al., The ICF Core Sets for hearing loss-researcher perspective. Part I: Systematic review of outcome measures identified in audiological research. International Journal of Audiology, 2014. 53(2): p. 65-76.

- Akeroyd, M.A., et al., A comprehensive survey of hearing questionnaires: how many are there, what do they measure, and how have they been validated? Trials, 2015. 16(1): p. 1-1.

- Neal, K., et al., Listening-based communication ability in adults with hearing loss: A scoping review of existing measures. Frontiers in Psychology, 2022. 13: p. 786347.

- Danermark, B., et al., The creation of a comprehensive and a brief core set for hearing loss using the international classification of functioning, disability and health. Am J Audiol, 2013. 22(2): p. 323-8.

- Allen, D., L. Hickson, and M. Ferguson, Defining a Patient-Centred Core Outcome Domain Set for the Assessment of Hearing Rehabilitation With Clients and Professionals. Front Neurosci, 2022. 16: p. 787607.

- Andries, E., et al., Implementation of the international classification of functioning, disability and health model in cochlear implant recipients: a multi-center prospective follow-up cohort study. . Front Audiol Otol, 2023. 1: p. 1257504.

- Boisvert, I., et al., Editorial: Outcome Measures to Assess the Benefit of Interventions for Adults With Hearing Loss: From Research to Clinical Application. Front Neurosci, 2022. 16: p. 955189.

- Clarke, M. and P.R. Williamson, Core outcome sets and systematic reviews. Systematic reviews, 2016. 5(1): p. 1-4.

- COMET. Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials. 2022; Available from: https://www.comet-initiative.org/.

- Allen, D., L. Hickson, and M. Ferguson, Defining a patient-centred core outcome domain set for the assessment of hearing rehabilitation with clients and professionals. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 2022. 16.

- Hall, D.A., et al., Toward a global consensus on outcome measures for clinical trials in tinnitus: report from the first international meeting of the COMiT Initiative, November 14, 2014, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Trends in Hearing, 2015. 19: p. 2331216515580272.

- Dietz, A., et al., The effectiveness of cochlear implantation on performance-based and patient-reported outcome measures in Finnish recipients. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 2022.

- Laird, E., et al., Systematic review of patient and service outcome measures of remote digital technologies for cochlear implant and hearing aid users. Frontiers in Audiology and Otology, 2024. 2.

- Hughes, S.E., et al., Rasch analysis of the listening effort Questionnaire—Cochlear implant. Ear and Hearing, 2021. 42(6): p. 1699-1711.

- McRackan, T.R., et al., Cochlear Implant Quality of Life (CIQOL): development of a profile instrument (CIQOL-35 Profile) and a global measure (CIQOL-10 Global). Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 2019. 62(9): p. 3554-3563.

- Maidment, D., et al., Evaluating a theoretically informed and co-created mHealth educational intervention for first-time hearing aid users: a qualitative interview study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 2020. 8(8): p. e17193.

- Gomez, R., et al., Smartphone-Connected Hearing Aids Enable and Empower Self-Management of Hearing Loss: A Qualitative Interview Study Underpinned by the Behavior Change Wheel. Ear and Hearing, 2022. 43(3): p. 921-932.

- Sucher, C., et al., Patient preferences for remote cochlear implant management: A discrete choice experiment. PLoS One, in review.

- Allen, D., et al., Developing a Core Outcome Domain Set for Remote Cochlear Implant Management. Submitted.

- Foundation., P.S., The Python Language Reference.

- McKinney, W. Data Structures for Statistical Computing in Python. in Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference. 2010.

- Harris, C.R. and et al., Array Programming with NumPy. Nature, 2020. 585(7825): p. 357-362.

- Virtanen, P. and et al., SciPy 1.0: Fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nature Methods, 2020. 17(3): p. 261-272.

- F., P. and et al., Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 2011. 12: p. 2825-2830.

- Team., T.M.D., Matplotlib: Visualisation with Python, Zenodo, Editor. 2025.

- Atkinson, J., et al., NZDep2023 Index of Socioeconomic Deprivation: Research Report. 2024: Wellington.

- Gatehouse, S. and W. Noble, The Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing Scale (SSQ). Int J Audiol, 2004. 43(2): p. 85-99.

- Bench, J. and J. Doyle, The BKB/A (Banford-Kowal-Bench/Australian version) sentence lists for hearing-impaired children. . 1979, La Trobe University: Victoria, Australia.

- Boothroyd A, H.L., & Hnath T., A sentence test of speech perception: reliability, set equivalence, and short term learning. CUNY Academic Works, 1985. 1985.

- Peterson, G.E. and I. Lehiste, Revised CNC lists for auditory tests. J Speech Hear Disord, 1962. 27: p. 62-70.

- Boothroyd, A., Developments in Speech Audiometry. Sound, 1968. 2: p. 3-10.

- Noble, W., et al., A short form of the Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing scale suitable for clinical use: the SSQ12. Int J Audiol, 2013. 52(6): p. 409-12.

- Ventry, I.M. and B.E. Weinstein, The hearing handicap inventory for the elderly: a new tool. Ear Hear, 1982. 3(3): p. 128-34.

- Killion, M.C., et al., Development of a quick speech-in-noise test for measuring signal-to-noise ratio loss in normal-hearing and hearing-impaired listeners. J Acoust Soc Am, 2004. 116(4 Pt 1): p. 2395-405.

- Etymotic Research, Etymotic BKB-SIN Speech-in-Noise Test User Manual. 2005. p. 1-27.

- Smits, C., S. Theo Goverts, and J.M. Festen, The digits-in-noise test: assessing auditory speech recognition abilities in noise. J Acoust Soc Am, 2013. 133(3): p. 1693-706.

- Gatehouse, S., A self-report outcome measure for the evaluation of hearing aid fittings and services. Health Bull (Edinb), 1999. 57(6): p. 424-36.

- Cox, R.M. and G.C. Alexander, The abbreviated profile of hearing aid benefit. Ear Hear, 1995. 16(2): p. 176-86.

- Hinderink, J.B., P.F. Krabbe, and P. Van Den Broek, Development and application of a health-related quality-of-life instrument for adults with cochlear implants: the Nijmegen cochlear implant questionnaire. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 2000. 123(6): p. 756-65.

- King, N., et al., A new comprehensive cochlear implant questionnaire for measuring quality of life after sequential bilateral cochlear implantation. Otol Neurotol, 2014. 35(3): p. 407-13.

- Spitzer, R.L., et al., A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med, 2006. 166(10): p. 1092-7.

- Nilsson, M., S.D. Soli, and J.A. Sullivan, Development of the Hearing in Noise Test for the measurement of speech reception thresholds in quiet and in noise. J Acoust Soc Am, 1994. 95(2): p. 1085-99.

- Cassarly, C., et al., The Revised Hearing Handicap Inventory and Screening Tool Based on Psychometric Reevaluation of the Hearing Handicap Inventories for the Elderly and Adults. Ear Hear, 2020. 41(1): p. 95-105.

- Dawson, P.W., A.A. Hersbach, and B.A. Swanson, An adaptive Australian Sentence Test in Noise (AuSTIN). Ear Hear, 2013. 34(5): p. 592-600.

- Spahr, A.J. and M.F. Dorman, Performance of subjects fit with the Advanced Bionics CII and Nucleus 3G cochlear implant devices. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 2004. 130(5): p. 624-8.

- Cox, R., et al., Optimal outcome measures, research priorities, and international cooperation. Ear Hear, 2000. 21(4 Suppl): p. 106S-115S.

- Dillon, H., G. Birtles, and R. Lovegrove, Measuring the Outcomes of a National Rehabilitation Program: Normative Data for the Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI) and the Hearing Aid User’s Questionnaire (HAUQ). J Am Acad Audiol 1999, 1999. 10(02): p. 67-79.

- McRackan, T.R., et al., Cochlear Implant Quality of Life (CIQOL): Development of a Profile Instrument (CIQOL-35 Profile) and a Global Measure (CIQOL-10 Global). J Speech Lang Hear Res, 2019. 62(9): p. 3554-3563.

- Amann, E. and I. Anderson, Development and validation of a questionnaire for hearing implant users to self-assess their auditory abilities in everyday communication situations: the Hearing Implant Sound Quality Index (HISQUI19). Acta Otolaryngol, 2014. 134(9): p. 915-23.

- The ida Institute. ida Institute Motivational Tools: The Line. [cited 2025 17/03/2024].

- Hawthorne, G. and A. Hogan, Measuring disability-specific patient benefit in cochlear implant programs: developing a short form of the Glasgow Health Status Inventory, the Hearing Participation Scale. Int J Audiol, 2002. 41(8): p. 535-44.

- McBride, W.S., et al., Methods for screening for hearing loss in older adults. Am J Med Sci, 1994. 307(1): p. 40-2.

- Yesavage, J.A., et al., Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res, 1982. 17(1): p. 37-49.

- Luetje, C.M., et al., Phase III clinical trial results with the Vibrant Soundbridge implantable middle ear hearing device: a prospective controlled multicenter study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 2002. 126(2): p. 97-107.

- Beck, A.T., et al., An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 1961. 4: p. 561-71.

- Antony, M.M., et al., Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychological Assessment, 1998. 10(2): p. 176–181.

- Zigmond, A.S. and R.P. Snaith, The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 1983. 67(6): p. 361-70.

- Kompis, M., et al., Factors influencing the decision for Baha in unilateral deafness: the Bern benefit in single-sided deafness questionnaire. Adv Otorhinolaryngol, 2011. 71: p. 103-111.

- Topp, C.W., et al., The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: a systematic review of the literature. Psychother Psychosom, 2015. 84(3): p. 167-76.

- Cox, R.M. and G.C. Alexander, Expectations about hearing aids and their relationship to fitting outcome. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 2000. 11: p. 368-382.

- Billinger-Finke, M., et al., Development and validation of the audio processor satisfaction questionnaire (APSQ) for hearing implant users. Int J Audiol, 2020. 59(5): p. 392-397.

- De Jong Gierveld, J. and F. Kamphuls, The Development of a Rasch-Type Loneliness Scale. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1985. 9(3): p. 289-299.

- De Jong Gierveld, J. and T. Van Tilburg, A 6-Item Scale forOverall, Emotional, and Social Loneliness. Confirmatory Tests on Survey Data. Research on Aging, 2006. 28: p. 582-598.

- Terluin, B., et al., The Four-Dimensional Symptom Questionnaire (4DSQ): a validation study of a multidimensional self-report questionnaire to assess distress, depression, anxiety and somatization. BMC Psychiatry, 2006. 6: p. 34.

- Diener, E., et al., The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 1985. 49: p. 71-75.

- Russell, D., L.A. Peplau, and C.E. Cutrona, The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1980. 39: p. 472-480.

- Davies, A.R. and J.E. Ware Jr, GHAA’s Consumer Satisfaction Survey and User’s Manual. 2nd ed, ed. G.H.A.o. America. 1991, Washington DC.

- McConnaughy, E.A., J.O. Prochaska, and W.F. Velicer, Stages of change in psychotherapy: Measurement and sample profiles. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 1983. 20(3): p. 368–375.

- Levenstein, S., et al., Development of the Perceived Stress Questionnaire: a new tool for psychosomatic research. J Psychosom Res, 1993. 37(1): p. 19-32.

- Heffernan, E., N.S. Coulson, and M.A. Ferguson, Development of the Social Participation Restrictions Questionnaire (SPaRQ) through consultation with adults with hearing loss, researchers, and clinicians: a content evaluation study. Int J Audiol, 2018. 57(10): p. 791-799.

- Sansoni, J., et al., Technical Manual and Instructions for the Revised Incontinence and Patient Satisfaction Tools, ed. C.f.H.S. Development. 2011, Wollongong, NSW: University of Wollongong.

- Cox, R.M. and G.C. Alexander, Measuring Satisfaction with Amplification in Daily Life: the SADL scale. Ear Hear, 1999. 20(4): p. 306-20.

- Reichheld, F.F., The one number you need to grow, in Harvard Business Review. 2003, Harvard Business School Publishing: Massachusetts, US.

- Heffernan, E., A. Habib, and M. Ferguson, Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the social isolation measure (SIM) in adults with hearing loss. Int J Audiol, 2019. 58(1): p. 45-52.

- CI Task Force. Adult Hearing Standards of Care; Living Guidelines. 2022 [cited 2025 24/03/2025]; Available from: https://adulthearing.com/standards-of-care/.

- Mokkink, L.B., E.B.M. Elsman, and C.B. Terwee, COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures version 2.0. Qual Life Res, 2024. 33(11): p. 2929-2939.

- Boisvert, I., et al., Cochlear implantation outcomes in adults: A scoping review. PLoS One, 2020. 15(5).

- Duncan, E.A. and J. Murray, The barriers and facilitators to routine outcome measurement by allied health professionals in practice: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res, 2012. 12: p. 96.

- Hatfield, D.R. and B.M. Ogles, Why some clinicians use outcome measures and others do not. Adm Policy Ment Health, 2007. 34(3): p. 283-91.

- O'Connor, B., et al., Understanding allied health practitioners' use of evidence-based assessments for children with cerebral palsy: a mixed methods study. Disabil Rehabil, 2019. 41(1): p. 53-65.

- Aiyegbusi, O.L., et al., Recommendations to address respondent burden associated with patient-reported outcome assessment. Nat Med, 2024. 30(3): p. 650-659.

- Collaborative., A.H.H. ANZ Hearing Health Collaborative (ANZ HHC): Living Guidelines for Cochlear Implant (CI) Referral, CI Evaluation and Candidacy, and CI Outcome Evaluation in Adults 2025 [cited 2025 10/08/2025]; Available from: https://hhc.anz.adulthearing.com/hhc-2/projects/#follow.

- Sucher, C., et al., Development of the LivCI: a patient-reported outcome measure of personal factors that affect quality of life, use and acceptance of cochlear implants. , in World Congress of Audiology. 2024: Paris.

- Laird, E., C. Sucher, and M. Ferguson, Development of a self-report measure of Living with Cochlear Implants (LivCI): A content evaluation. International Journal of Audiology, submitted.

- Hughes, S., et al., Living with Cochlear Implants (LivCI): Development and validation of a new patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) of personal factors associated with living with cochlear implants (LivCI). submitted.

- Ferguson, M., T. Sahota, and C. Sucher, “Don’t assume I’m too old!”: Assessment of Digital Literacy in a Clinical Sample of Adults with Hearing Loss. Submitted.

- Prusaczyk, B., T. Swindle, and G. Curran, Defining and conceptualizing outcomes for de-implementation: key distinctions from implementation outcomes. Implement Sci Commun, 2020. 1: p. 43.

| SUPRADOMAIN | ||||||

| SERVICE | CLINICAL | PATIENT | ||||

|

Domain Priority |

CI Users |

CI Professionals |

CI Users |

CI Professionals |

CI Users |

CI Professionals |

| 1st |

Reliability of remote technology |

Usability of remote technology |

Speech recognition in noise |

Device integrity & status |

Participation restriction due to HL | Expectations of hearing health outcomes |

| 2nd |

Usability of the remote technology |

Accessibility of the remote service (for CI user) |

Speech recognition in quiet |

Speech discrimination |

Hearing Related Quality of Life AND* Satisfaction with CI |

Motivation & Readiness to Act on hearing difficulties |

| 3rd |

Accessibility of the remote service (for CI user) |

Reliability of remote technology |

Speech discrimination | Device Use | Mental Health & Wellbeing |

Acceptability & Tolerability of the CI (for CI user) |

| Number of Participants (%) | Median (years) |

Range (years) |

|

| Duration of Clinical Audiology Experience | 20 (100%) | 20.0 | 7-41 |

| Duration of CI specific clinical Audiology Experience | 20 (100%) | 19.0 | 4-40 |

| Experience in Audiology-focused research | 12 (60%) | 7.5 | 0-40 |

| Experience in CI-specific research | 14 (70%) | 12 | 0-40 |

|

Clinical Measure/PROM |

Never Heard | Never Used | Occasionally Used | Regularly Used | Median Response |

| Speech and Spatial Qualities Scale (SSQ) [43] | 0 | 2 | 5 | 13 | Regularly Used |

| Bamford-Kowal-Bench Sentence Test, Australian Version (BKB/A) [44] | 0 | 1 | 6 | 10 | Regularly Used |

| City University of New York Sentence Test (CUNY©) [45] | 0 | 2 | 2 | 13 | Regularly Used |

| Consonant-Nucleus-Consonant Words (CNC Words) - [46] | 0 | 1 | 0 | 16 | Regularly Used |

| Arthur Boothroyd Words (AB Words) [47] | 0 | 1 | 1 | 15 | Regularly Used |

| Short Form Speech and Spatial Qualities Scale (SSQ-12) [48] | 4 | 1 | 1 | 14 | Regularly Used |

| Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly (HHIE) [49] | 2 | 6 | 10 | 2 | Occasionally Used |

| Quick Speech In Noise Test (QuickSIN™) [50] | 2 | 4 | 9 | 2 | Occasionally Used |

| Bamford-Kowal-Bench Sentences In Noise Test (BKB-SIN™) [51] | 1 | 5 | 4 | 7 | Occasionally Used |

| Digits-In-Noise/Digit Triplet Test (DIN/DTT) [52] | 2 | 3 | 7 | 5 | Occasionally Used |

| Glasgow Hearing Aid Benefit Profile (GHABP) [53] | 0 | 9 | 8 | 3 | Occasionally Used |

| Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit (APHAB) [54] | 2 | 7 | 4 | 7 | Occasionally Used |

| Nijmegen Cochlear Implant Questionnaire (NCIQ) [55] | 4 | 6 | 9 | 1 | Never Used |

| Comprehensive Cochlear Implant Questionnaire (CCIQ) [56] | 8 | 5 | 7 | 0 | Never Used |

| General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) [57] | 7 | 13 | 0 | 0 | Never Used |

| Hearing In Noise Test (HINT) [58] | 2 | 8 | 6 | 1 | Never Used |

| Revised Hearing Handicap for the Elderly (RHHI) [59] | 7 | 12 | 1 | 0 | Never Used |

| Revised Hearing Handicap for the Elderly - Screening (RHHI-S) [59] | 8 | 11 | 1 | 0 | Never Used |

| Austin Sentence Test (Austin) [60] | 3 | 6 | 4 | 4 | Never Used |

| AzBio Sentence Test (AzBio) [61] | 1 | 12 | 3 | 1 | Never Used |

| International Outcomes Inventory - Cochlear Implants (IOI-CI) [62] | 2 | 11 | 4 | 3 | Never Used |

| Hearing Aid Users Questionnaire (HAUQ) [63] | 9 | 8 | 2 | 1 | Never Used |

| Cochlear Implant Quality of Life Questionnaire - Global (CIQoL-Global) [64] | 9 | 4 | 7 | 0 | Never Used |

| Hearing Implant Sound Quality Index (HISQUI19) [65] | 9 | 7 | 3 | 1 | Never Used |

| IDA Tool - The Line (The Line) [66] | 8 | 8 | 2 | 2 | Never Used |

| Hearing Participation Scale (HPS) [67] | 8 | 11 | 1 | 0 | Never Used |

| Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly - Screening (HHIE-S) [68] | 4 | 9 | 5 | 2 | Never Used |

| Geriatric Depression Scale - Long (GDS-L) [69] | 9 | 11 | 0 | 0 | Never Used |

| Cochlear Implant Quality of Life Questionnaire - Profile (CIQoL-Profile) [64] | 9 | 7 | 4 | 0 | Never Used |

| Hearing Device Satisfaction Scale (HDSS) [70] | 8 | 11 | 1 | 0 | Never Used |

| Beck's Depression Index (BDI) [71] | 9 | 10 | 1 | 0 | Never Used |

| Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (21 Item) (DASS-21) [72] | 8 | 10 | 2 | 0 | Never Used |

| Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (42 Item) (DASS-42) [72] | 7 | 11 | 2 | 0 | Never Used |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [73] | 9 | 5 | 5 | 1 | Never Used |

| Bern Benefit in Single-Sided Deafness (BBSS) [74] | 10 | 9 | 1 | 0 | Never Heard |

| WHO Well-being Index (WHO-S) [75] | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | Never Heard |

| Expected Consequences of Hearing Aid Ownership (ECHO) [76] | 13 | 7 | 0 | 0 | Never Heard |

| Audio Processor Satisfaction Questionnaire (APSQ) [77] | 12 | 7 | 1 | 0 | Never Heard |

| De Jong Gierveld Loneliness scale (11 Item) (DJGLS-11) [78] | 15 | 5 | 0 | 0 | Never Heard |

| De Jong Gierveld Loneliness scale (6 Item) (DJGLS-6) [79] | 15 | 5 | 0 | 0 | Never Heard |

| The Four Dimensional Symptom Questionnaire (4DSQ) [80] | 16 | 4 | 0 | 0 | Never Heard |

| Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) [81] | 16 | 4 | 0 | 0 | Never Heard |

| UCLA Loneliness Index (Revised) (UCLA) [82] | 16 | 4 | 0 | 0 | Never Heard |

| Visit-Specific Satisfaction Questionnaire (VSQ-9) [83] | 19 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Never Heard |

| University of Rhode Island Change Assessment adapted for hearing loss (URICA-HL) [84] | 13 | 7 | 0 | 0 | Never Heard |

| Perceived Stress Questionnaire (PSQ) [85] | 12 | 8 | 0 | 0 | Never Heard |

| Social Participation Restrictions Questionnaire (SPaRQ) [86] | 12 | 8 | 0 | 0 | Never Heard |

| Short Assessment of Patient Satisfaction (SAPS) [87] | 14 | 5 | 0 | 1 | Never Heard |

| Satisfaction with Amplification in Daily Life (SADL) [88] | 11 | 9 | 0 | 0 | Never Heard |

| Net Promoter Score (NPS) [89] | 12 | 6 | 2 | 0 | Never Heard |

| Social Isolation Measure (SIM) [90] | 14 | 6 | 0 | 0 | Never Heard |

| CI Professionals | CI Users | |

| General | Assessment of all 3 supradomains is important |

Assessment of all 3 supradomains is important Asynchronous remote assessments must consider the amount of time required for the user to complete

|

| Service Supra-domain |

Preference for simplicity of measurement

|

Preference for simplicity of measurement

|

Technology for remote services should be accessible for everyone

|

Technology for remote services should be accessible for everyone

|

|

| Clinical Supra-domain |

System checks are essential

|

System checks are essential

|

Preference for a minimalist approach focusing on a few key measures

|

Preference for a minimalist approach focusing on a few key measures

|

|

Speech perception tests

|

Speech perception tests

|

|

Historical testing

|

Historical testing

|

|

Remote test environment

|

||

| Patient Supra-domain |

PROMs (patient reported outcome measures)

|

PROMs (patient reported outcome measures)

|

Mental Health and Well-being

|

Subjective hearing disability

|

|

Satisfaction with CI

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).