Introduction

Ischemia with no obstructive coronary artery disease (INOCA) refers to a clinical condition characterized by myocardial ischemia in the absence of significant coronary artery stenosis. INOCA represents a challenge, as patients frequently present with typical symptoms such as chest pain and dyspnoea, but conventional diagnostic tests do not reveal significant lesions in the coronary arteries.

These patients often exhibit signs of myocardial ischemia, despite the absence of obstructive coronary disease. These can be caused by underlying pathophysiological mechanisms, such as microvascular dysfunction, coronary vasospasm or endothelial dysfunction. These contribute to a reduced blood supply to the myocardium and can lead to both acute and chronic symptoms of ischemia [

1].

Studies suggest the prevalence of INOCA is significant and it may affect 10-20% of patients presenting with angina and chest pain and up to 50% of patients with no epicardial disease on coronary angiograms. While traditionally overshadowed by obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD), the recognition of INOCA has been increasing, particularly with advancements in diagnostic imaging techniques that can assess coronary microcirculation and myocardial perfusion. Patients with INOCA may remain undiagnosed leading to significant work days lost, healthcare costs of further investigations and clinic/ hospital attendance for unresolved symptoms. However, managing INOCA remains difficult: conventional treatments such as pharmacological therapy, lifestyle modifications, and medical management alone often fail to provide adequate relief for many patients [

2].

Medical therapies typically include anti-anginal agents as well as statins and anti-platelet agents that aim at stabilizing microvascular dysfunction and reducing ischemic events. It is recognised that a subgroup of patients experiences persistent, debilitating symptoms that do not resolve with medical management alone [

3].

While surgical treatment options are rarely employed in INOCA due to the absence of obstructive lesions, there are emerging strategies being explored in clinical practice and research [

4].

This systematic review aims to critically evaluate the available evidence on surgical treatment options for INOCA and provide an overview of the current role of surgery in managing this complex condition. This may help refine surgical indications and improve patient outcomes in the management of INOCA.

Material and Methods

A thorough search strategy was developed to locate all relevant studies. The review adhered to the PRISMA guidelines, ensuring transparency and replicability in methodology. The following electronic databases were explored for articles published between 2000 and 2024: PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Google Scholar. The search terms included various combinations of keywords such as “Ischemia with No Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease,” “INOCA,” “Microvascular Dysfunction,” “Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting,” “Percutaneous Coronary Intervention,” “Transmyocardial Revascularization,” “Stem Cell Therapy,” “Sympathectomy,” and “Surgical Treatment in INOCA.” We aimed to identify studies that examined surgical treatment interventions, outcomes and pathophysiology in INOCA. No limitations were applied regarding the study type, but only studies meeting the inclusion criteria were selected for further analysis. Inclusion criteria encompassed studies published in peer-reviewed journals that focused on surgical procedures or interventions for INOCA patients. A narrative synthesis was performed from the included studies (

Table 1) due to heterogeneity in study designs and outcomes.

Pathophysiology of INOCA

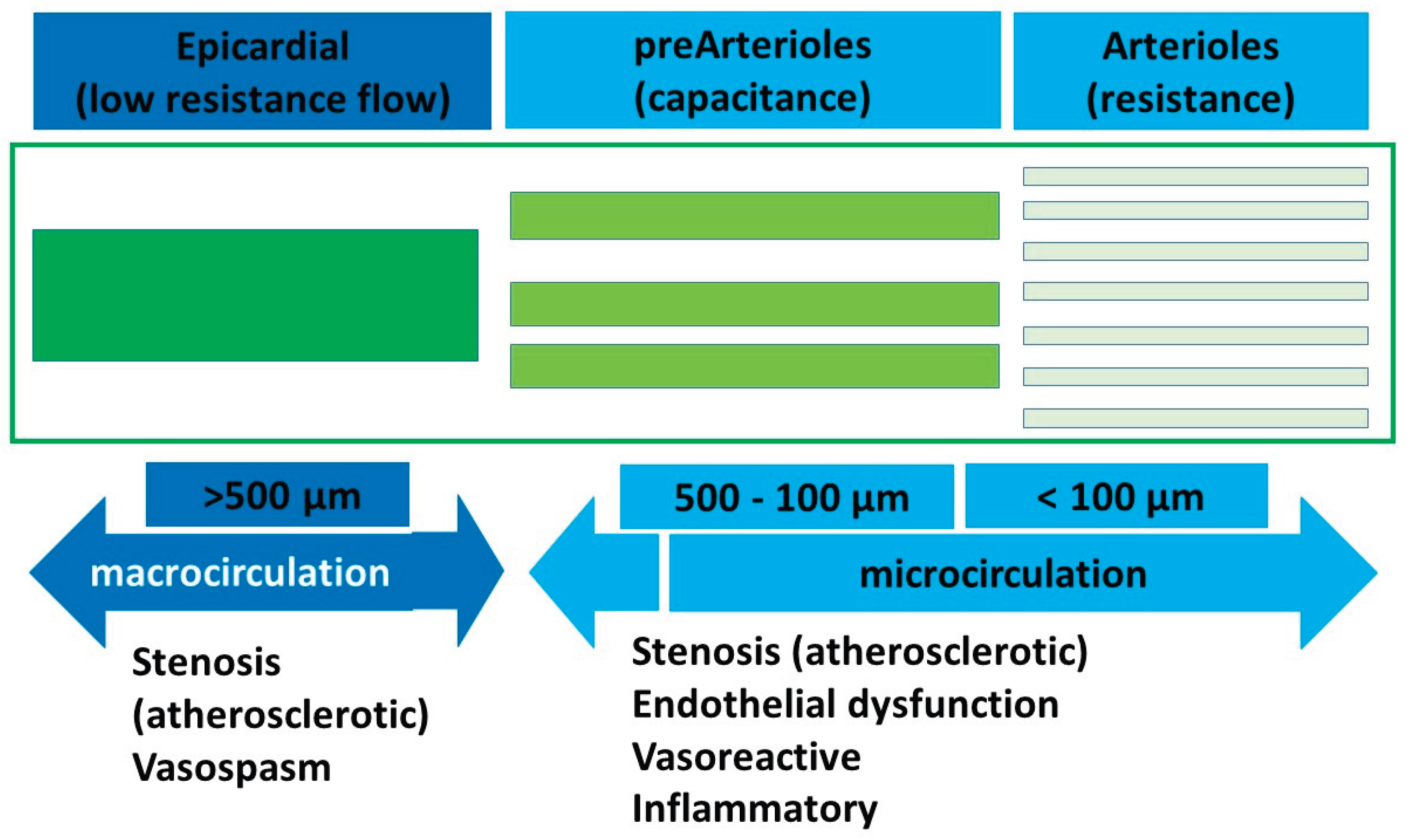

Microvasculature typically involves the pre-arteriolar vessels (< 500 µm) and arterioles (<100 µm). The pre-arteriolar vessels are conductance vessels and the arteriolar vessels are the resistance vessels in the coronary circulation. The pathophysiology and endotypes of INOCA can be largely divided into the putative mechanisms affecting these two groups of microvessels as either obstruction or vasospasm or a combination of the two (

Figure 1). Microvascular dysfunction, coronary vasospasm, endothelial dysfunction and inflammation are the main recognised underlying pathophysiology causes of INOCA, among other mechanisms.

Coronary microvascular dysfunction has been identified as the most common mechanism underlying INOCA. The coronary microcirculation includes small vessels (arterioles and capillaries) for regulating blood flow to the myocardium. Microvascular dysfunction can lead to reduced coronary blood flow and oxygen supply to the heart muscle, even in the absence of large vessel obstructive disease.

Several factors contribute to CMD:

Increased vasoconstriction: the small vessels may experience excessive constriction, often linked to abnormal responses to vasodilators, further limiting blood flow and leading to a mismatch between oxygen supply and demand.

Impaired vasodilation: In CMD, due to endothelial dysfunction, vasodilation is impaired during periods of increased myocardial demand, such as exercise or stress.

Increased vascular stiffness: blood flow regulation can be impaired by loss of elasticity in the microvessels and this can lead to ischemic episodes in patients with INOCA [

5,

6].

Endothelial dysfunction is considered another key factor in the pathogenesis of INOCA and it seems to be led by a reduction in the bioavailability of nitric oxide, generally released by the endothelium.

The endothelial cells may produce a reduced amount of nitric oxide or the body may have impaired responses to this molecule, leading to a decreased relaxation of smooth muscle cells in the coronary.

Endothelial dysfunction is known to be associated with increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress, which may contribute to microvascular damage.

Furthermore, in patients with INOCA, the shear stress, which is the ability of endothelial cells to respond to mechanical forces, is often impaired, and that further contributes to the dysfunction of the microcirculation [

6].

Coronary vasospasm is a transient, reversible constriction of the coronary arteries, which can significantly reduce blood flow to the myocardium.

Vasospasm can occur in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease and may intermittently reduce coronary blood flow, mimicking the symptoms of a myocardial infarct or angina.

Endothelial dysfunction can lead to vasospasm, as it causes an imbalance between vasoconstrictor and vasodilator substances, predisposing the coronary arteries to spasms [

7].

Subclinical atherosclerosis and inflammation may contribute into INOCA’ pathophysiology.

Small plaques or fatty streaks may form within the coronary microcirculation and can compromise the blood flow.

Also, elevated levels of inflammatory markers such as interleukins and C-reactive protein (CRP) have been observed in patients with INOCA, suggesting that ongoing inflammation within the microvasculature may affect their function [

8].

The onset and course of INOCA can be influenced by hormonal imbalances, particularly those affecting oestrogen and other sex hormones. These hormonal changes may make women more susceptible to INOCA, especially those in their late reproductive years or post-menopausal.

It’s also known that the autonomic nervous system (ANS) regulates coronary vasomotion; sympathetic and parasympathetic branches imbalance can contribute to vasospasm or microvascular abnormalities [

8].

It’s believed that genetic factors may predispose individuals to INOCA, despite the exact genetic mechanisms are yet unknown. Furthermore, environmental such as obesity, smoking, stress and low physical activity are well-established risk factors of endothelial dysfunction and microvascular disease [

1].

The pathophysiology of INOCA is multifactorial; understanding these underlying mechanisms is essential for improving diagnostic accuracy and developing effective therapeutic strategies [

5].

Diagnostic Approach to INOCA

The diagnosis of INOCA is challenging due to the lack of visible obstruction on traditional tests. Advanced diagnostic strategies are needed to assess the functionality of the coronary microcirculation, as well as detecting other possible causes of ischemia such as endothelial dysfunction or vasospasm [

3].

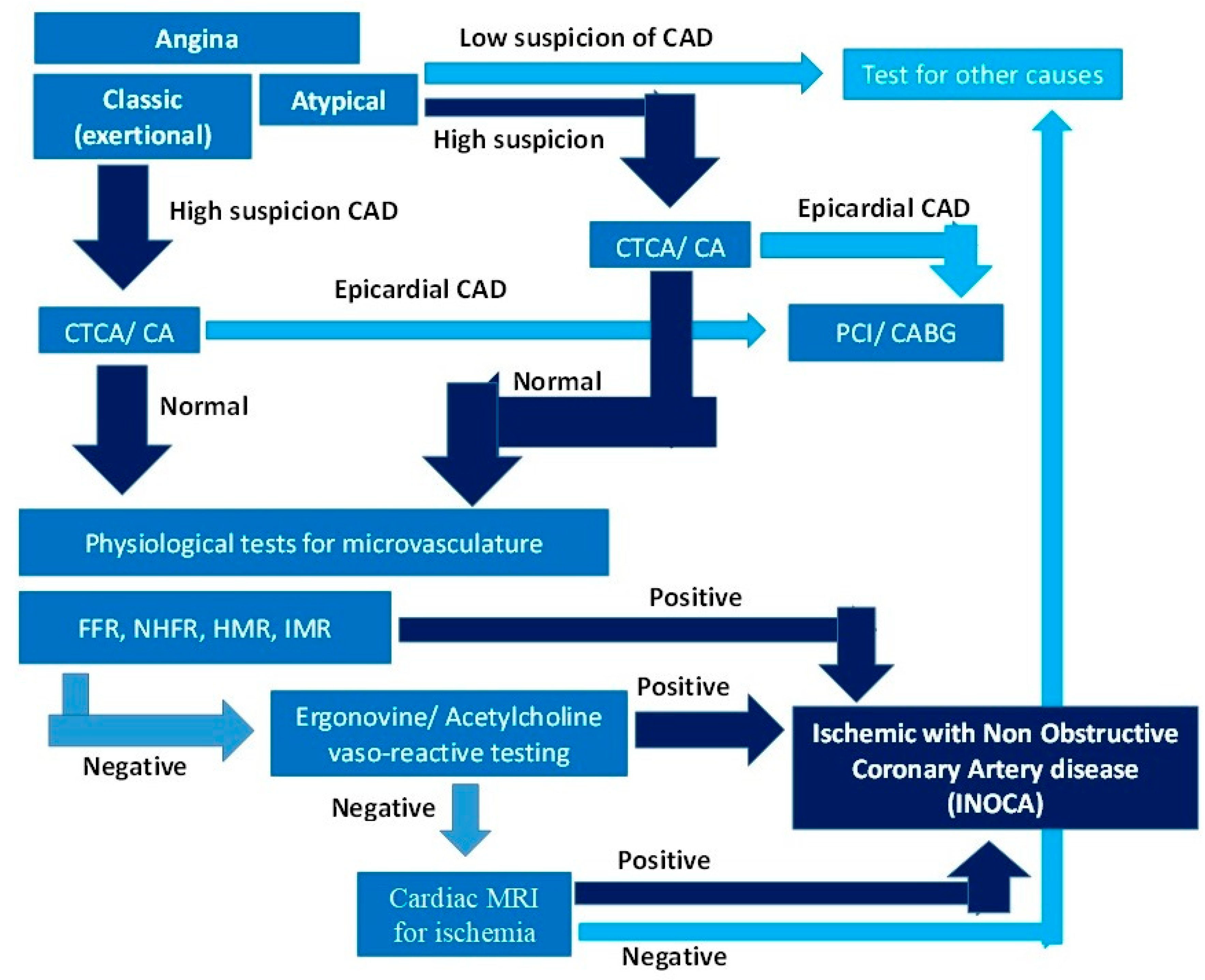

The salient differentiating features of micro and macrovascular coronary artery disease are summarized in

Table 2. The diagnostic tools and approaches currently used to diagnose INOCA include imaging modalities and physiological tests of flow and resistance in the microcirculation, which are the mainstay for diagnosis. A diagnostic algorithm is provided in

Figure 2.

A. Imaging modalities;

A1. Coronary Angiography (CA): Invasive coronary angiography is the gold standard imaging technique for detecting obstructive focal and diffuse epicardial coronary artery disease. It cannot adequately image the microvasculature at a typical spatial resolution of 0.1-0.2 mm. A Computed Tomography Coronary Angiogram (CTCA) has an inferior resolution of 0.3-0.4 mm but can approach that of an invasive angiogram with a ultrahigh resolution scan (UHR-CTCA). These imaging modalities are insensitive in diagnosing INOCA.

The main role of CA/CTCA in INOCA diagnosis is to rule out epicardial obstructive coronary artery disease, as cause of ischemia. It is the first step in the diagnostic algorithm for INOCA (

Figure 1).

A2. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Cardiac MRI is a non-invasive imaging tool that provides detailed information about myocardial structure, perfusion and function.

Cardiac MRI with stress imaging can assess myocardial perfusion and identify areas of ischemia; also it may show areas of reduced perfusion, even in the absence of significant stenosis and so the role of Cardiac MRI in INOCA diagnosis is important.

Using late Gadolinium Enhancement (LGE) it’s possible to identify areas of myocardial injury or fibrosis, which may be observed in patients with chronic ischemia from microvascular dysfunction.

Also, MRI is helpful in excluding other potential causes of chest pain or symptoms, such as myocardial infarction or structural heart disease [

7].

A3. Positron Emission Tomography (PET): with this advanced imaging technique it’s possible to evaluate myocardial perfusion, coronary blood flow and metabolic activity. It is highly sensitive in detecting subclinical myocardial ischemia.

PET is a valuable tool in INOCA diagnosis because it can detect regional ischemia, even in the absence of significant coronary artery disease.

A4. Intravascular Ultrasound (IVUS) and Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT): Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) and optical coherence tomography (OCT) are advanced adjunct imaging modalities that provide detailed microscopic pictures of the epicardial coronary arteries to exclude obstructive focal disease as the primary cause of ischemia.

IVUS provides detailed cross-sectional images of the coronary arteries using high-frequency sound waves. Its main application is to assess the extent of plaque burden but it can identify signs of microvascular illness in the surrounding tissue.

OCT provides high-resolution images of the coronary arteries using near-infrared light, which enables a more detailed evaluation of endothelial and microvascular abnormalities in addition to plaque appearance.

These tests can provide valuable information on the presence of subclinical atherosclerosis [

9].

B. Physiological tests

B1.

Fractional Flow Reserve (FFR): FFR is a diagnostic technique used to assess the functional significance of both epicardial and microcirculatory coronary stenosis. It represents the pressure drop across the circulation. It can be measured with invasive (using a pressure catheter during invasive CA) or with CTCA. It can also provide insight into microvascular dysfunction in INOCA: FFR can be abnormal even in the absence of large vessel obstruction [

3]. Typically values less than 0.80 are considered significant (indexed FFR < 0.89).

In cases of INOCA, a normal CA is seen with a decreased FFR, indicating that the microcirculation is not adequately compensating for increased myocardial demand and it may indicate microvascular dysfunction.

FFR measurements may also help guide the selection of appropriate medical therapies, particularly those aimed at improving coronary flow and reducing ischemia.

Measures of microvascular flow and resistance

Nonhyperemic pressure ratio (NHPR)

Coronary Flow Reserve (CFR): Coronary flow reserve (CFR) is the measure of the capacity of coronary vessels to increase blood flow in response to metabolic demand. It is calculated by assessing blood flow under baseline conditions and then during stress. Microvascular dysfunction can significantly reduce CFR.

A CFR value less than 2.0 is considered indicative of impaired coronary flow reserve, often reflecting microvascular dysfunction, and it’s one of the key markers of INOCA.

CFR is a useful diagnostic and prognostic tool, as it has been shown to correlate with clinical outcomes [

8].

Index of microcirculatory resistance (IMR)

Stress Testing: Stress testing is commonly used in the evaluation of patients with suspected INOCA. It involves monitoring the patient’s heart during physical exercise or pharmacologic stress to assess the heart’s response to increased demand. Stress testing can help identify ischemic changes that may not be visible at rest.

The Exercise Treadmill Testing, pharmacologic Stress Testing with medications and stress echocardiography are the most common stress testing utilised.

Also, nuclear stress tests (e.g., SPECT or PET) can show myocardial perfusion defects, even in the absence of coronary artery disease.

Stress tests are useful tools in identifying myocardial ischemia in patients with INOCA, helping to confirm the diagnosis and to assess the severity of ischemia [

10].

Non-Surgical Treatment of INOCA

Medical therapy is the mainstay in the treatment of INOCA and aims to reduce symptoms and improve quality of life.

Pharmacologic Therapy

Pharmacological management of INOCA focuses to improve endothelial function, optimize coronary blood flow and manage ischemic symptoms (

Table 3). The treatment aims to increase myocardial blood supply by reducing spasm and vasodilatory effects and reduce myocardial oxygen demand by reducing rate/contractility. Preventative therapies aim to reduce progression of atherosclerotic burden of the obstructive disease.

Lifestyle Modifications

Lifestyle changes are crucial in managing INOCA’ patients symptoms; they can help reducing the overall burden on the cardiovascular system and improve coronary microcirculation.

Exercise and Physical Activity: Cardiovascular exercise has been shown to reduce oxidative stress, improve endothelial function and enhance coronary blood flow.

Weight Management and Healthy Diet: Managing risk factors such as hyperlipidaemia, hypertension and obesity through maintaining healthy weight and following a balanced diet can help controlling INOCA symptoms.

Stress Management and Mental Health: symptoms of INOCA can be exacerbated by chronic stress and anxiety, possibly through sympathetic nervous system activation and increased myocardial oxygen demand.

Smoking Cessation and Alcohol Moderation: Smoking and excessive alcohol consumption are considered significant risk factors for endothelial dysfunction and may exacerbate coronary microvascular disease [

11].

Surgical Treatment Options for INOCA

Surgical treatment options can be considered in specific circumstances, in which pharmacological therapy cannot control the symptoms or when microvascular dysfunction is accompanied by other coronary pathology, such as small vessel disease or epicardial vasospasm.

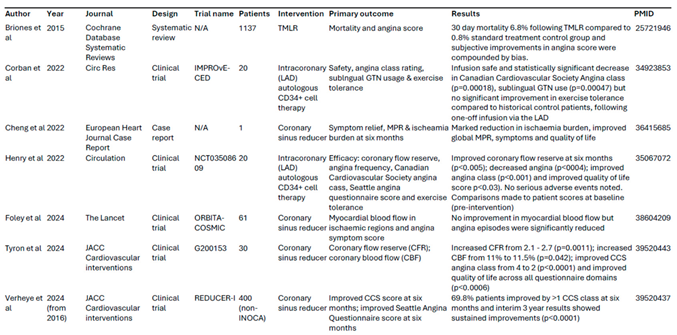

We explored potential surgical treatment options for INOCA, although it is important to note that they are still used rarely compared to medical management. Key studies of surgical treatments were summarised in

Table 1.

Transmyocardial revascularization (TMR) is a surgical technique designed to improve myocardial perfusion, using a laser (usually a carbon dioxide (CO2) laser) to create small channels in the heart muscle facilitating blood flow from the epicardial coronary vessels directly into the myocardium. Over time, the heart may develop collateral circulation, which can help to relieve symptoms of angina and improve heart function.

TMR is typically performed with minimally invasive surgery, though it can also be done with traditional cardiac surgery approach.

TMR has been primarily utilised for patients with advanced obstructive coronary artery disease, where traditional options like PCI or CABG were not possible; however, there is some growing interest in exploring its potential for treating INOCA [

12].

While TMR holds promise for the treatment of INOCA, it is important to mention that, currently, its use has been studied in patients with obstructive coronary artery disease, there is only limited research specifically investigating its efficacy in INOCA. More research is needed to determine whether TMR has beneficial short and long term benefits in patients with microvascular dysfunction or endothelial dysfunction associated with INOCA.

Some studies have suggested that the improvement in perfusion may be temporary: while it may improve myocardial perfusion by creating collateral circulation, it is unclear whether it can reverse the microvascular abnormalities that are central to INOCA.

Like any surgical procedure, TMR carries risks and for INOCA patients those risks must be carefully considered and balanced with the uncertain durability of the benefits of TMR [

13].

Sympathetic denervation is a surgical procedure that targets the sympathetic pathway of the autonomic nervous system, to treat specific cardiovascular diseases.

In the context of INOCA, sympathetic denervation has been explored as a potential treatment for patients experiencing coronary vasospasm.

The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) plays a crucial role in regulating vascular tone, and excessive activation or dysregulation of sympathetic pathways can contribute to the development of vasospasm [

14].

Sympathetic denervation consist in blocking the sympathetic nerves that innervate the coronary arteries, which can reduce coronary artery spasm and improve myocardial perfusion.

Sympathetic denervation can be achieved through percutaneous sympathetic nerve ablation technique or with surgical sympathectomy.

Percutaneous Sympathetic Nerve Ablation

This minimally invasive procedure targets sympathetic nerve fibres near the coronary arteries using radiofrequency ablation or chemical neurolysis. The procedure is typically performed during coronary angiography; that allows the physician to localize the sympathetic nerve clusters and apply targeted energy or chemical agents to ablate the nerve fibres.

Radiofrequency Ablation involves applying heat to selectively destroy the sympathetic nerve fibres, while chemical neurolysis uses agents such as phenol or ethanol to remove the nerves.

Surgical Sympathectomy

Thoracic sympathectomy involves surgically cutting down sympathetic nerve pathways in the chest. While this approach has been more commonly used in other areas (e.g., for hyperhidrosis or Raynaud’s disease), it has been proposed for refractory vasospastic angina, where vasospasm is a major contributor to ischemia.

This procedure is more invasive and typically considered for patients with severe, intractable symptoms that do not respond to medical treatment or percutaneous interventions [

15].

In some cases, an endoscopic approach may be used to perform sympathetic nerve blockade around the coronary arteries.

Sympathetic denervation can be considered as treatment option in selective patients with INOCA: although, percutaneous approaches are minimally invasive, sympathetic denervation still carries procedural risks. Removing or reducing sympathetic tone may result in an imbalance in autonomic regulation, potentially leading to unwanted side effects such as bradycardia, hypotension or decreased contractility in some cases. The long-term effectiveness of sympathetic denervation in INOCA patients remains unclear. For those reasons, sympathetic denervation for INOCA is still considered experimental and is not yet widely adopted in clinical practice. More studies are needed to validate its efficacy and safety [

16].

The coronary sinus reducer is an interventional device that’s being explored as a possible treatment option for patients with INOCA. The coronary sinus reducer is a stainless steel, hourglass shaped endoluminal device, which is percutaneously implanted into the coronary sinus through an expandable balloon, to increase coronary venous pressure in order to mitigate coronary microvascular resistance.

The concept behind this new therapy is that elevating pressure in the coronary venous system can cause dilatation of the subendocardial arterioles, resulting in a significant reduction of vascular resistance in this area and a possible redistribution of blood flow.

A double-blind sham-controlled trial (COSIRA trial) conducted in patients with refractory angina and obstructive coronary artery disease demonstrated that the implantation of the coronary sinus reducer helped alleviating refractory angina symptoms and improved quality of life [

17]. These findings appear to be longstanding, as the multi-centre observational REDUCER-I trial reported sustained improvement in angina symptoms and quality of life three years after coronary sinus reducer implants in participants from the COSIRA trial [

18].

Recent studies have specifically evaluated the coronary sinus reducer implants as possible treatment for INOCA patients. A case study reported a marked reduction in angina symptoms, as well as improved global myocardial perfusion and overall quality of life in one INOCA patient six months following coronary sinus reducer implantation [

19].Furthermore, a phase II trial published by Tryon D at al reported significant improvement in coronary blood flow, coronary flow reserve and angina symptoms in 30 patients with INOCA following coronary sinus reducer [

20]. Interestingly, the recent ORBITA-COSMIC trial assessed coronary sinus reducer implants for patients with stable coronary artery disease, ischaemia and no further options for antianginal therapy. This double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-centre study found no improvement in myocardial blood flow six months after implantation, but did report significantly reduced daily angina episodes, as reported via the designated smartphone ORBITA-app [

20]. These findings are promising for coronary sinus reducer implants as an antianginal option for INOCA patients.

Emerging therapies, as the use of stem cells to treat coronary microvascular dysfunction, have been investigated as potential interventions for INOCA. The main goal would be to use the patient’s own stem cells to promote the repair and regeneration of damaged blood vessels.

Corban.; et al. (2022) reported promising improvement in coronary flow reserve, angina symptoms and quality of life with intracoronary infusion of autologous CD34+ cells in patients with INOCA [

21]. Outcomes from the IMPROvE-CED trial also demonstrated safety and efficacy, with marked improvements in angina classification and sublingual GTN usage six months following a single infusion of CD34+ cells into the left anterior descending coronary artery of 20 INOCA patients, compared to 51 historic INOCA patients on maximal medical therapy [

22].

Ongoing studies such as the ESCaPE-CMD Trial and FREEDOM Trial are currently investigating the therapeutic potential, efficacy and safety of CD34+ cell therapy.

Although the concept is promising, stem cell therapy remains experimental and is not yet used in clinical practice. It is still unclear whether stem cell therapy will provide long-term benefits for patients with microvascular dysfunction or endothelial dysfunction [

3].

Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) are rarely indicated in the case of INOCA, as there is no significant epicardial coronary artery stenosis [

9].

In rare cases, if epicardial coronary vasospasm is identified as a contributor to INOCA and is resistant to pharmacological treatment those treatments can be considered [

4].

Conclusions

INOCA is a complex condition which primarily involves microvascular dysfunction, which impairs the normal regulation of blood vessel tone.

Medical management still remains the cornerstone of treatment for patients with INOCA, but when symptoms are refractory to pharmacological therapy, selected surgical treatments are emerging as possible options.

Among these, the coronary sinus reducer has shown improvement of symptoms and quality of life in promising early trials and may represent a minimally invasive strategy for enhancing microvascular perfusion. Transmyocardial revascularization offers potential symptomatic relief by promoting collateral circulation but currently lacks strong evidence for INOCA. Sympathetic denervation might be considered to relieve symptoms in patients with vasospastic angina but remains experimental with concerns about long-term efficacy. Targeted stem cell therapies are also emerging as potential therapies for this treatment refractory cohort.

Further research and clinical trials are needed to better understand the potential benefits and limitations of those surgical techniques.Given the complexity of INOCA, the most effective management strategy would likely involve a multidisciplinary approach that combines both non-surgical and surgical treatments, when indicated.

References

- Hochman, J. S.; et al. Ischemia and No Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease (INOCA): A New Paradigm for Cardiovascular Risk. European Heart Journal 2016, 37, 2345–2350. [Google Scholar]

- Bairey Merz, C. N.; et al. Ischemia with No Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease: A Review. JAMA Cardiology 2017, 2, 650–660. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, J.W.; Jneid, H. Ischemia with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries: A Review of Diagnosis and Management. Current Cardiology Reports 2020, 22, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Bavishi, C.; et al. Percutaneous Coronary Interventions in Patients with Angina and No Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease: A Systematic Review. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions 2018, 11, 766–774. [Google Scholar]

- Pepine, C.J.; Anderson, R.D. The Role of Microvascular Dysfunction in Ischemia with No Obstructive Coronary Arteries (INOCA). Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2017, 69, 211–212. [Google Scholar]

- Kaski, J. C.; et al. Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction and Ischemia with No Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease. European Heart Journal 2018, 39, 2963–2972. [Google Scholar]

- Taqueti, V.R.; Di Carli, M.F. Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction and Non-Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease: The Need for Better Diagnostic Tools and Therapeutic Options. JAMA Cardiology 2016, 1, 55–56. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; et al. Pathophysiology and Management of Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction in Patients with Angina and No Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease. Cardiovascular Research 2020, 116, 1373–1385. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, B.D.; et al. Ischemia with No Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease: A Summary of Pathophysiology and Potential Treatment Approaches. Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions 2018, 11, e007124. [Google Scholar]

- Crea, F.; Kaski, J.C. Microvascular Angina: Pathophysiology and Treatment. Nature Reviews Cardiology 2014, 11, 277–286. [Google Scholar]

- Her, A.Y.; Yoon, H.M. The Role of Lifestyle Modifications in the Management of INOCA: A Review of Current Evidence. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine 2020, 14, 123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Lazar, H.L.; McCabe, C.H. Transmyocardial Laser Revascularization: A New Technique for Revascularization of Myocardium in the Absence of Coronary Artery Disease. Circulation 1997, 96, 2667–2674. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, A.M.; Danchin, N. Microvascular Dysfunction in Ischemia with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries (INOCA): Mechanisms and Future Treatment Strategies. European Heart Journal 2016, 37, 2875–2883. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.; et al. Sympathetic Nerve Activity and its Impact on Coronary Microvascular Function in Ischemia with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries (INOCA). Circulation 2021, 144, 92–101. [Google Scholar]

- Dewire, D.W.; Chou, T.C. Autonomic Nervous System Modulation in Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction: Clinical Implications and Future Therapies. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology 2020, 75, 207–214. [Google Scholar]

- Farb, M.G.; Dorn, J.T. Neuromodulation Therapies for Cardiac Ischemia: Emerging Technologies and Potential Roles in INOCA. Cardiovascular Therapeutics 2022, 40, 1013–1025. [Google Scholar]

- Verheye, S.; et al. Efficacy of a Device to Narrow the Coronary Sinus in Refractory Angina. N Engl J Med 2015, 372, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verheye, S.; et al. Coronary sinus narrowing for the treatment of refractory angina: a multicentre prospective open-label clinical study (the REDUCER-I study). EuroIntervention. 2021, 17, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; et al. Implantation of the coronary sinus reducer for refractory angina due to coronary microvascular dysfunction in the context of apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy – a case report. Eur. Heart J Case Rep. 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tryon, D.; et al. Coronary Sinus Reducer Improves Angina, Quality of Life, and Coronary Flow Reserve in Microvascular Dysfunction. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions 2024, 17, 2893–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corban, M.T.; et al. IMPROvE-CED Trial: Intracoronary Autologous CD34+ cell therapy for treatment of coronary endothelial dysfunction in patients with angina and nonobstructive coronary arteries. Circ Res 2022, 130, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, D.T.; et al. Autologous CD34+ Stem Cell Therapy Increases Coronary Flow Reserve and Reduces Angina in Patients With Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction. Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).