Submitted:

16 October 2025

Posted:

17 October 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Setting the Stage

| COVID | Long COVID | |

| Date of First Paper | February 3, 2020 Nature – 19,000+ citations Lancet – 12,000+ citations |

November 3, 2020 JAMA – 446 citations |

| What is it? | A disease caused by a virus | The multiple, diverse consequences of a disease |

| Contagious | Yes, very | No |

|

Test |

Yes – PCR and rapid antigen | No |

| % of US afflicted population | ~90% | ~7% of those who had COVID |

|

Length of illness |

Typically, 5-10 days |

Months to years or perhaps permanent |

| Sex prevalence | Male | Female |

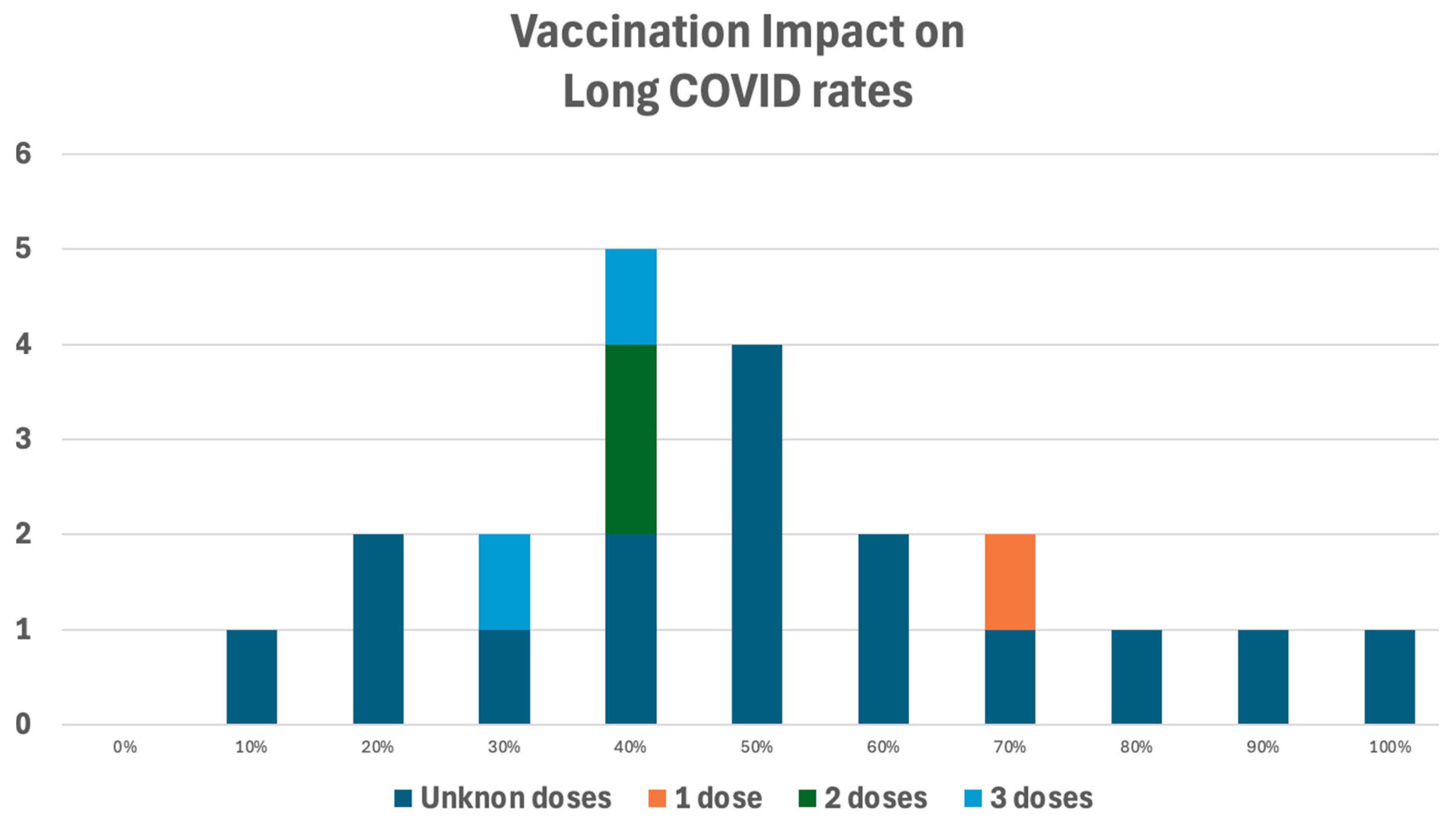

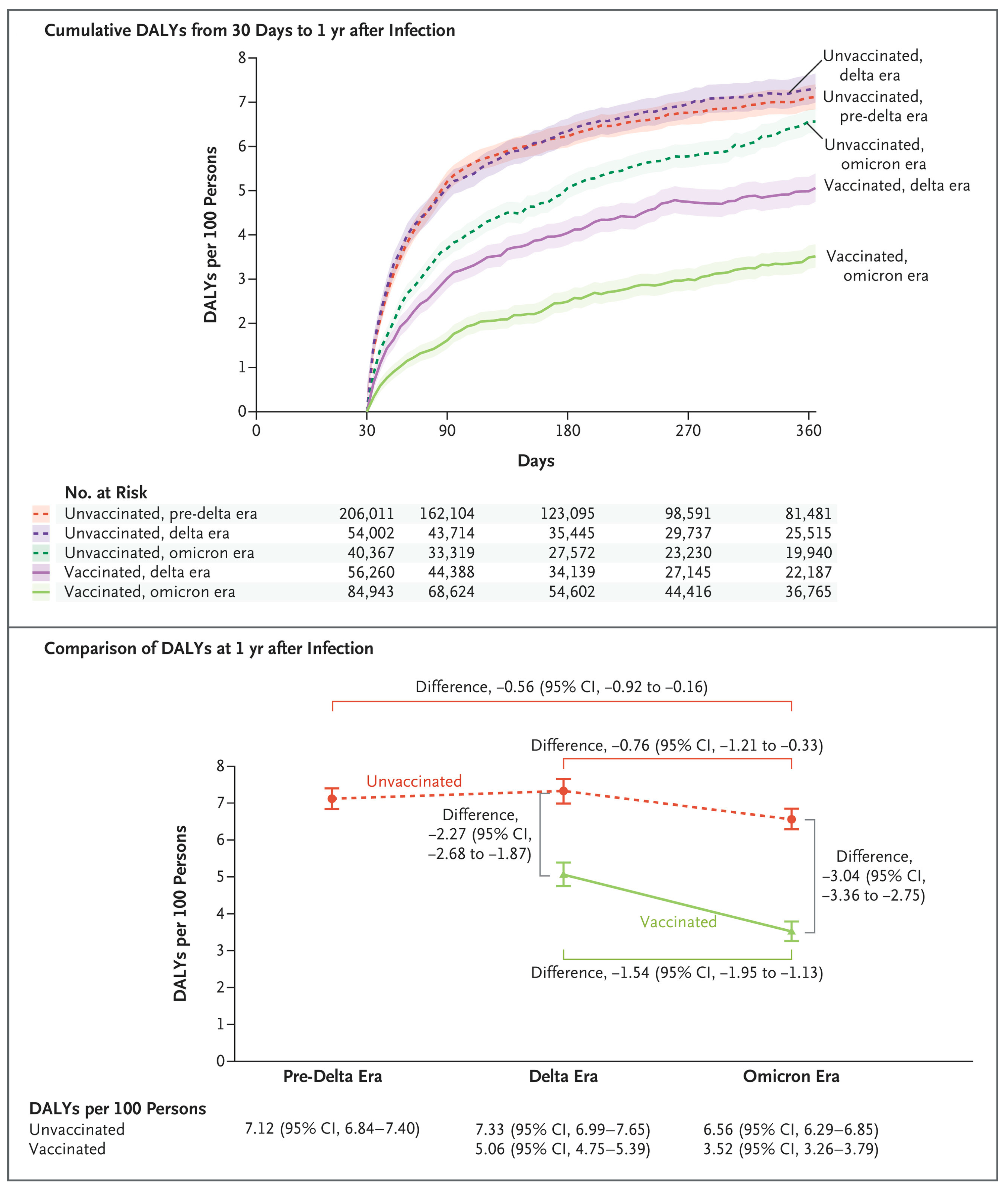

| Vaccination Impact | Significant reduction | No Long COVID vaccine and none is likely. However, pre-COVID vaccination helps. Post-COVID vaccination does not help. |

| Therapeutic objective | Avoid severe disease | Repair COVID damage |

| Therapeutic effectiveness tests | Biochemical tests based on the therapeutic type, i.e., antiviral, anti-inflammatory, oxygenation, and blood clots. |

Human trials and highly qualitative studies |

| Therapeutic placebo effect | Some | Can be significant |

| Disease / Virus | Common Long-Term Symptoms | Organs/Systems Affected | Duration | Percent Affected |

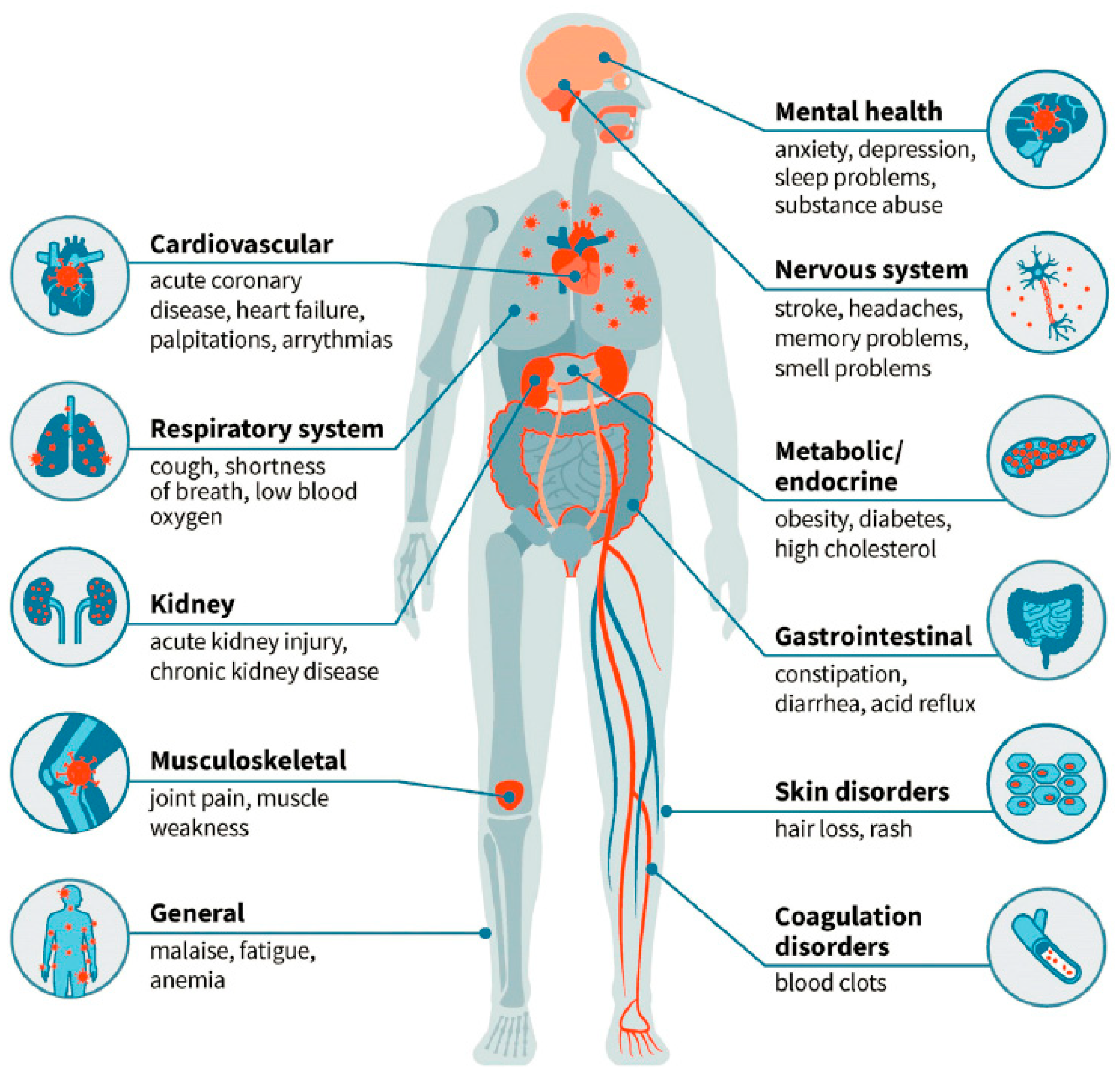

| COVID-19 | Fatigue, brain fog, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, heart palpitations, gastrointestinal issues | Brain, nerves, lungs, heart, kidney, liver, pancreas, genitals, musculoskeletal, immune system | Months to years |

~5 –15% higher after severe cases |

| Epstein-Barr | Chronic fatigue, memory issues, muscle pain | Brain, immune system, liver | Months to years | ~10–15% chronic fatigue syndrome |

| Influenza | Fatigue, weakness, rare Guillain-Barré syndrome or encephalitis | Nervous system, lungs | Weeks to months | ~1–2% mostly severe cases |

| Coxsackievirus B | Myocarditis, fatigue, chronic inflammation | Heart, muscles | Weeks to lifelong | ~5–10% |

| Zika Virus | Guillain-Barré syndrome, neuropathy, fetal defects if pregnant | Nerves, brain (fetal/adult) | Weeks to lifelong |

<1% Guillain-Barré syndrome, neuropathy ~5–10% mild neurological symptoms |

| SARS / MERS | Lung damage, post-traumatic stress disorder, fatigue | Lungs, nervous system | Months to years | ~25–40% |

| RSV | Wheezing, asthma in kids, chronic cough | Lungs, airway | Months to years | ~30–50% of children with severe RSV |

| Measles | subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (very rare), immune suppression | Brain, immune system | Years later | Rare |

| Chickenpox | Shingles, nerve pain (post theraputic neuralgia) | Nerves, skin | Weeks to years |

20–30% get shingles; ~10–15% of those get postherpetic neuralgia |

Long COVID

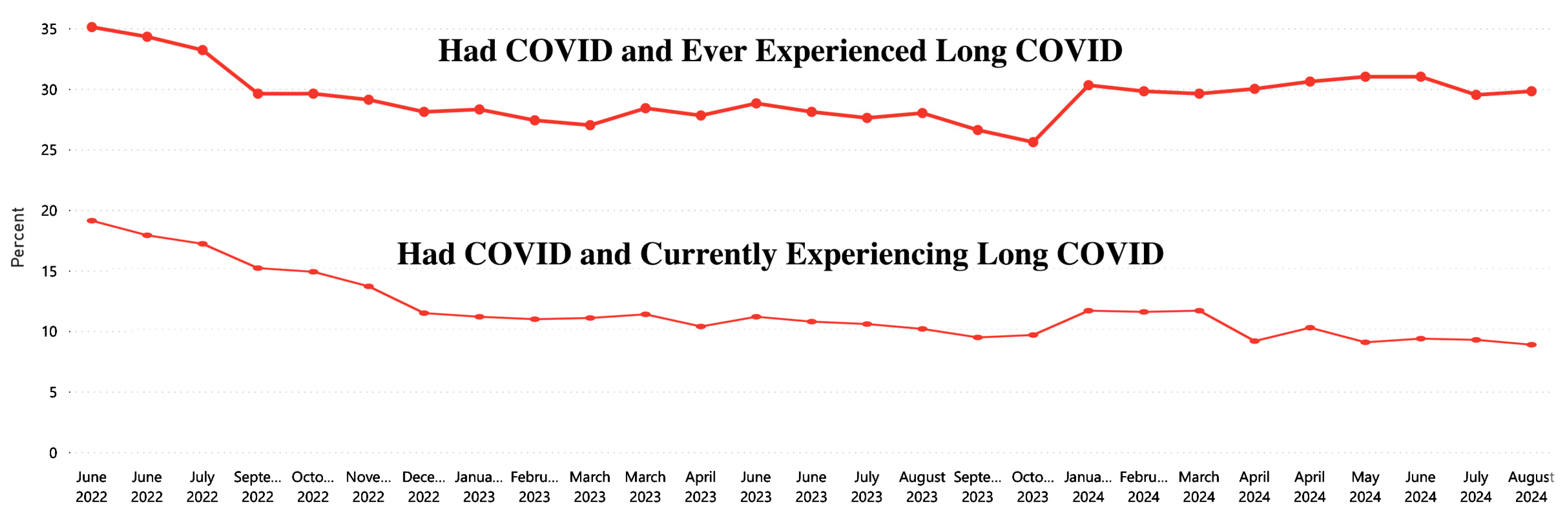

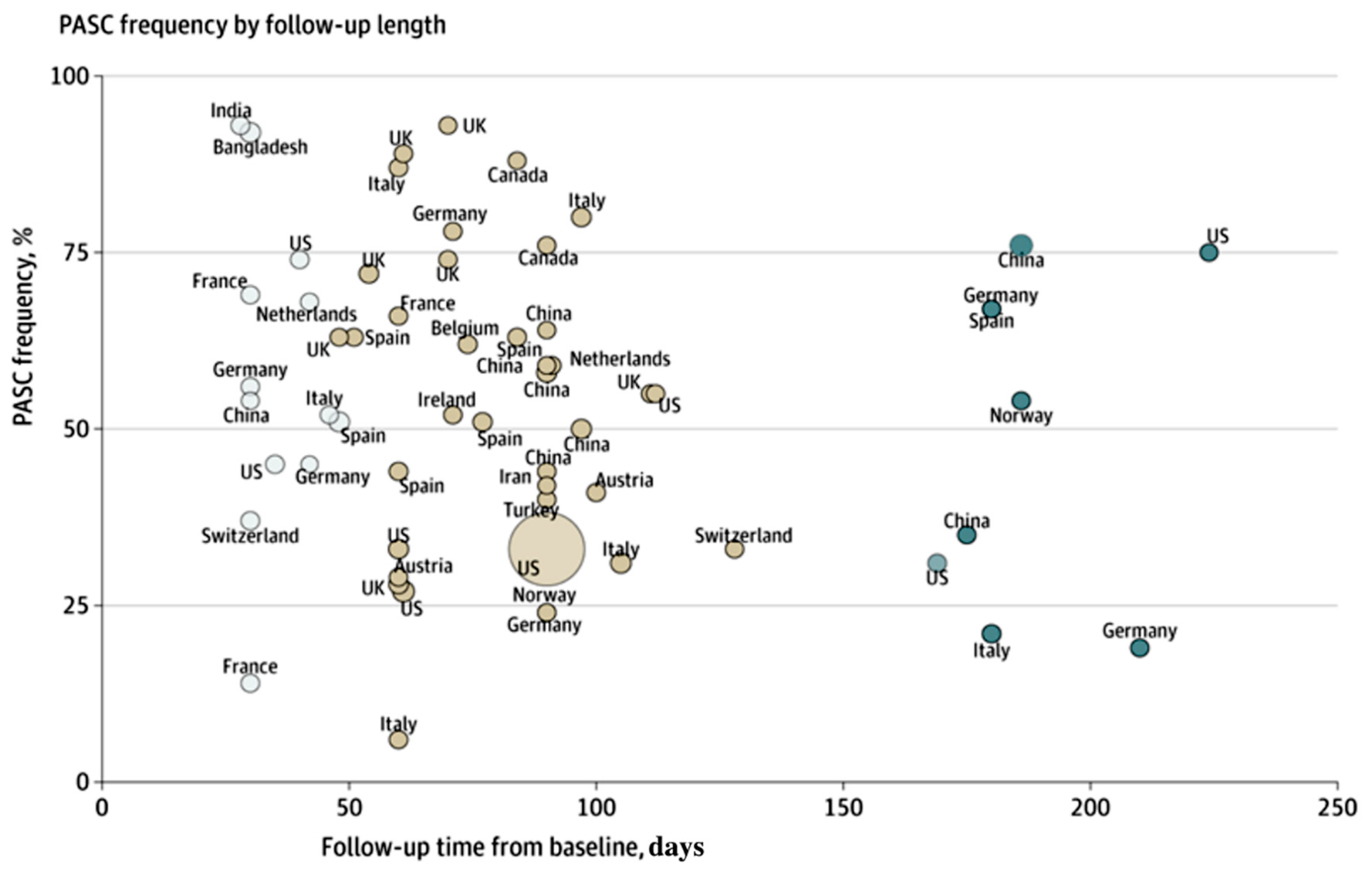

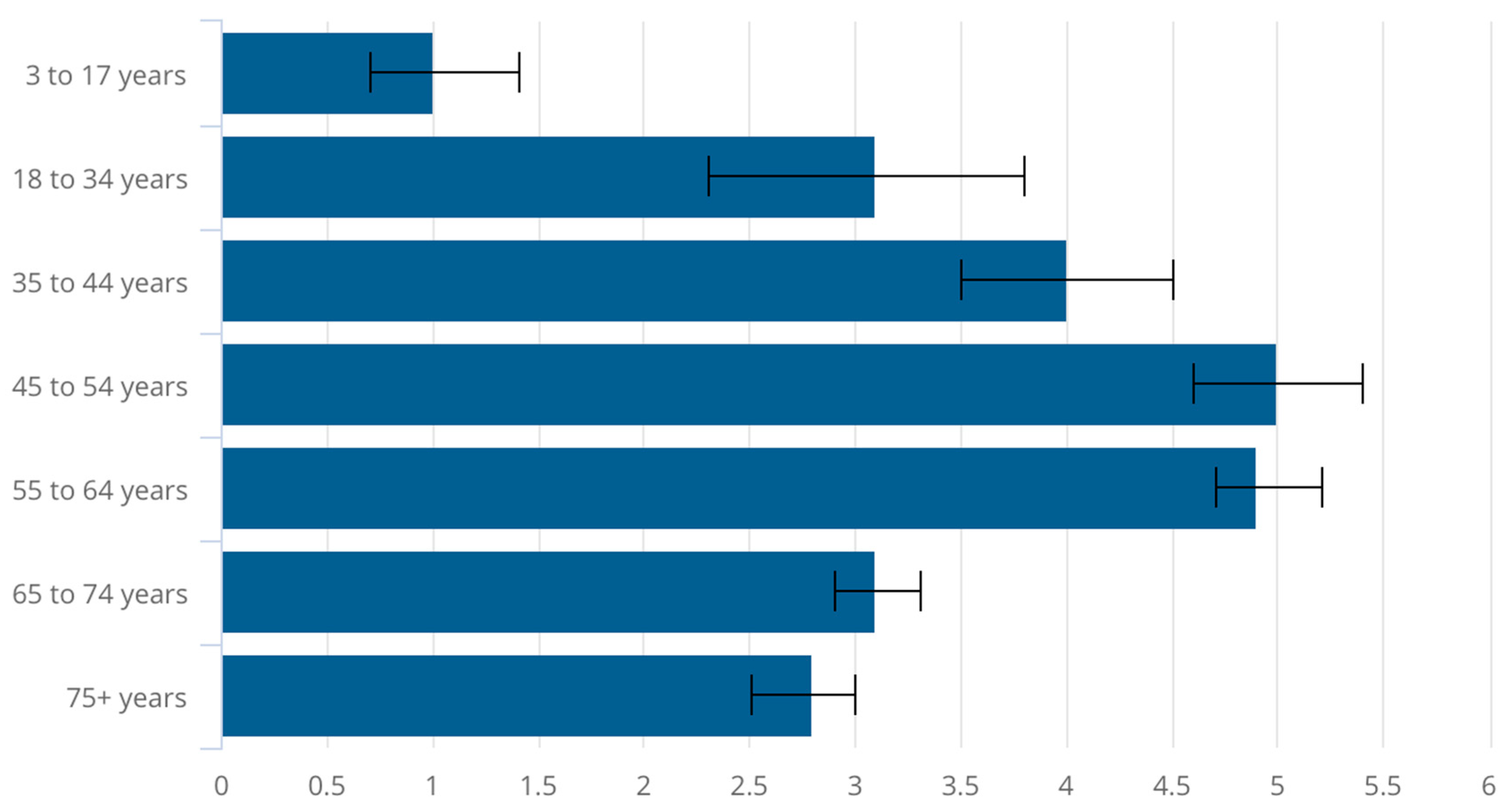

Long COVID Prevalence

- i.

- There are self-assessments with different criteria, e.g., walk test or how are you feeling?

- i.

- ii. Frequently there are not controls who also could have Long COVID symptoms, e.g., fatigue or depression.

- i.

- iii. There are mail surveys, on-line forms, phone calls, all of which have low response rates. Someone who doesn’t feel well is more likely to respond than someone who feels great which bias results.

- i.

- iv. There are different measures such as rate, risk ratios, and fully recovered.

- i.

- v. While there is a large symptom base, only a few symptoms are usually measured, usually fatigue or brain fog.

- i.

- Pandemic medical impacts, e.g., depression which can overlap with and can exacerbate Long COVID symptoms.

- i.

- ii. Age, sex, BMI, diseases, frailty, genetics

- i.

- iii. Variants

- i.

- iv. Therapeutics

- i.

- v. COVID Vaccination

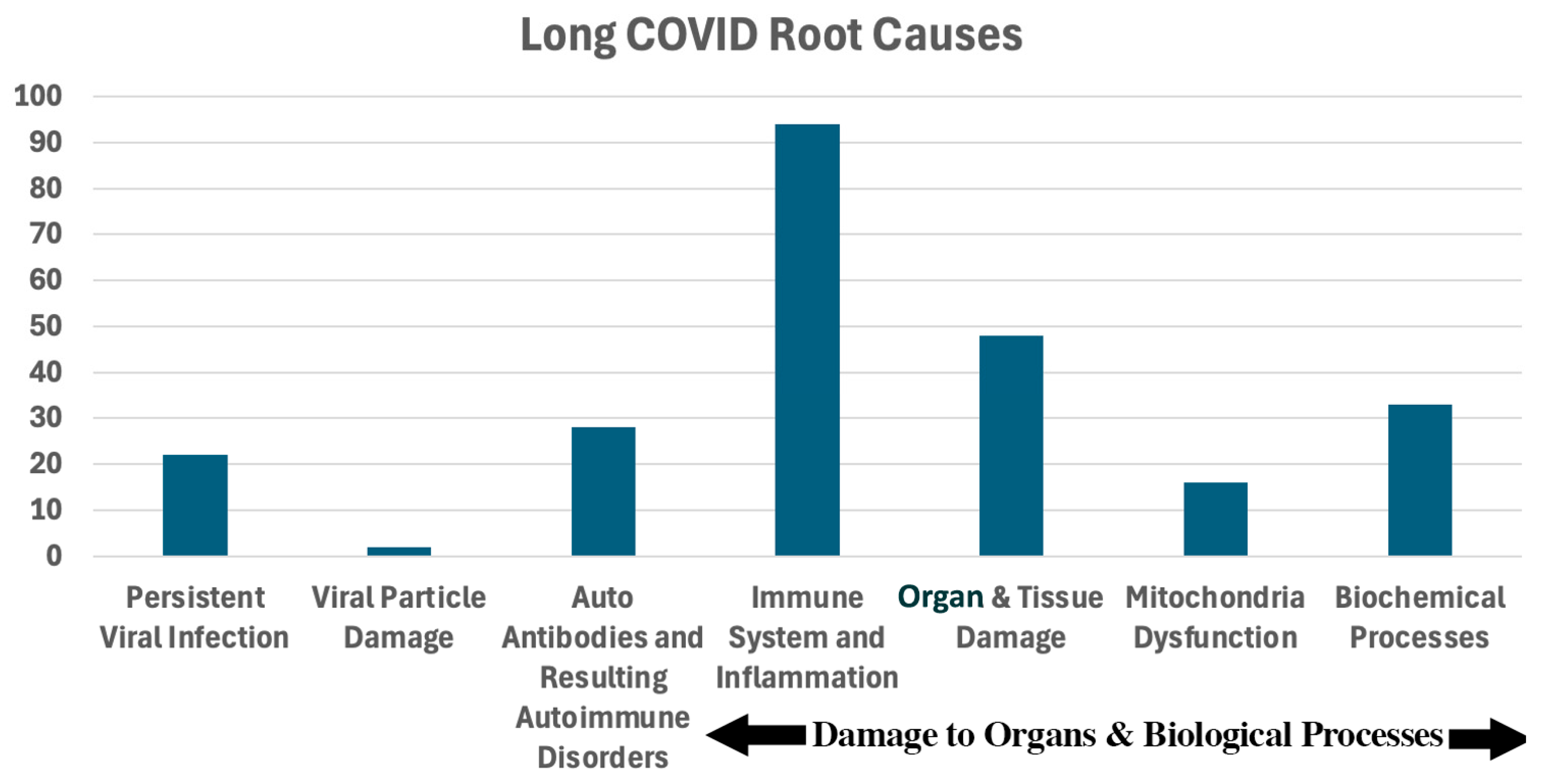

- Inflammation: Inflammation is probably Long COVID’s major root cause. Inflammation includes recruiting white blood cells and the release of cytokines that initiate tissue swelling and injury.

- Persistent viral infection: viral antigens, RNA, and SARS-CoV-2 proteins remain present and active in the body’s tissues following acute infection and continue to damage it.

- Viral particle damage to organs. A COVID case results in 1-30 trillion viral particles in the body. Some proteins, particularly the spike, the nucleocapsid, and the nonstructural protein 1 (nsp1) directly damage organs.

- Autoantibodies: Infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus can trigger autoimmune diseases.

- Biological processes and organs are damaged.

- a. All our organs are damaged.

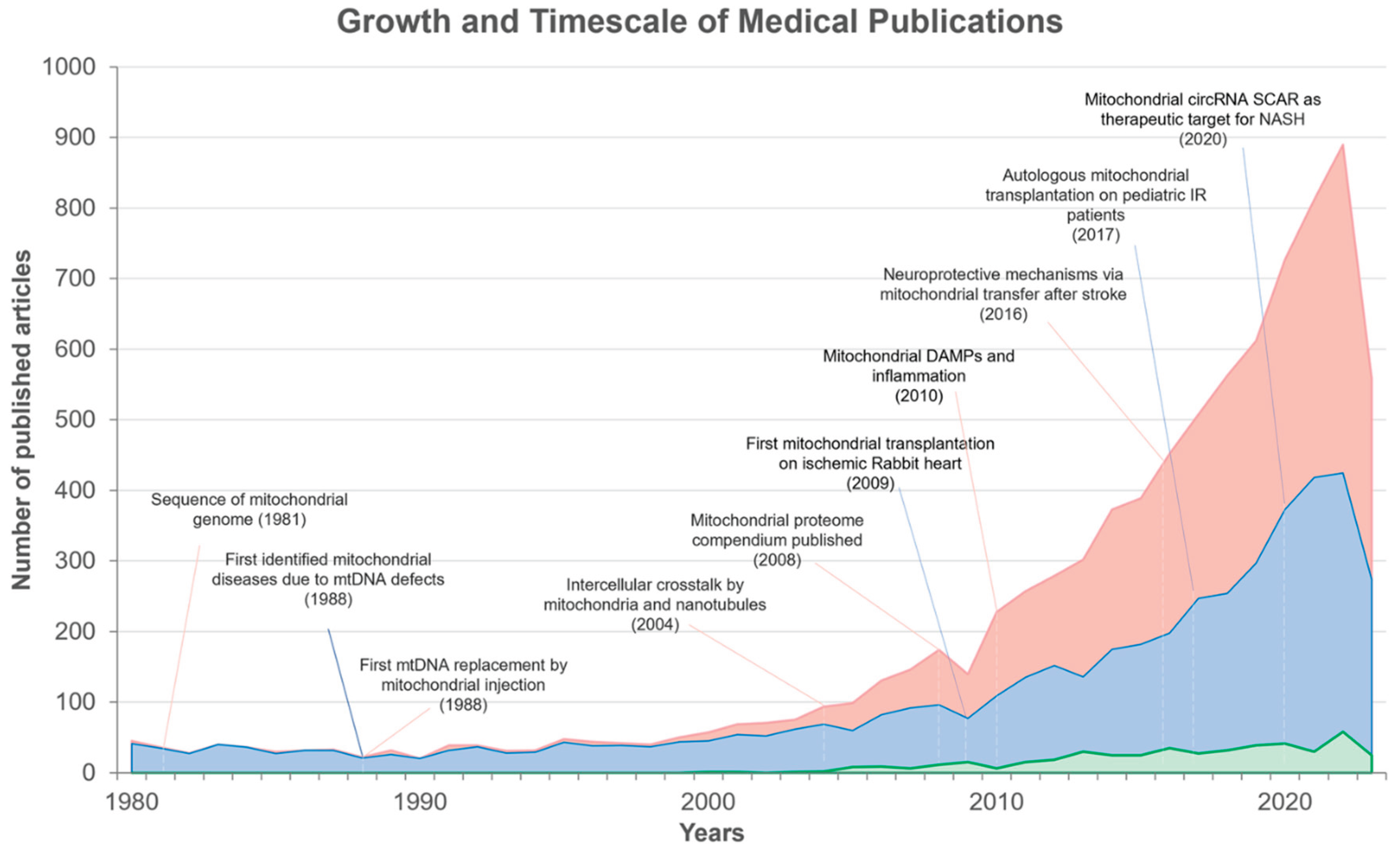

- b. Mitochondria, our energy workhorses, are greatly damaged by COVID. This results in fewer oxygen carrying molecules called ATP being generated for our bodies. This is a significant contributor to fatigue and brain fog.

- c. The proteins that are involved in healing are dysregulated.

Reducing the Chances of Long COVID

|

COVID Treatments |

Long COVID Treatments |

|

| FDA clinical treatment trials | 6,000 | 545 |

| PubMed published papersa | 198,000 | 17,000b |

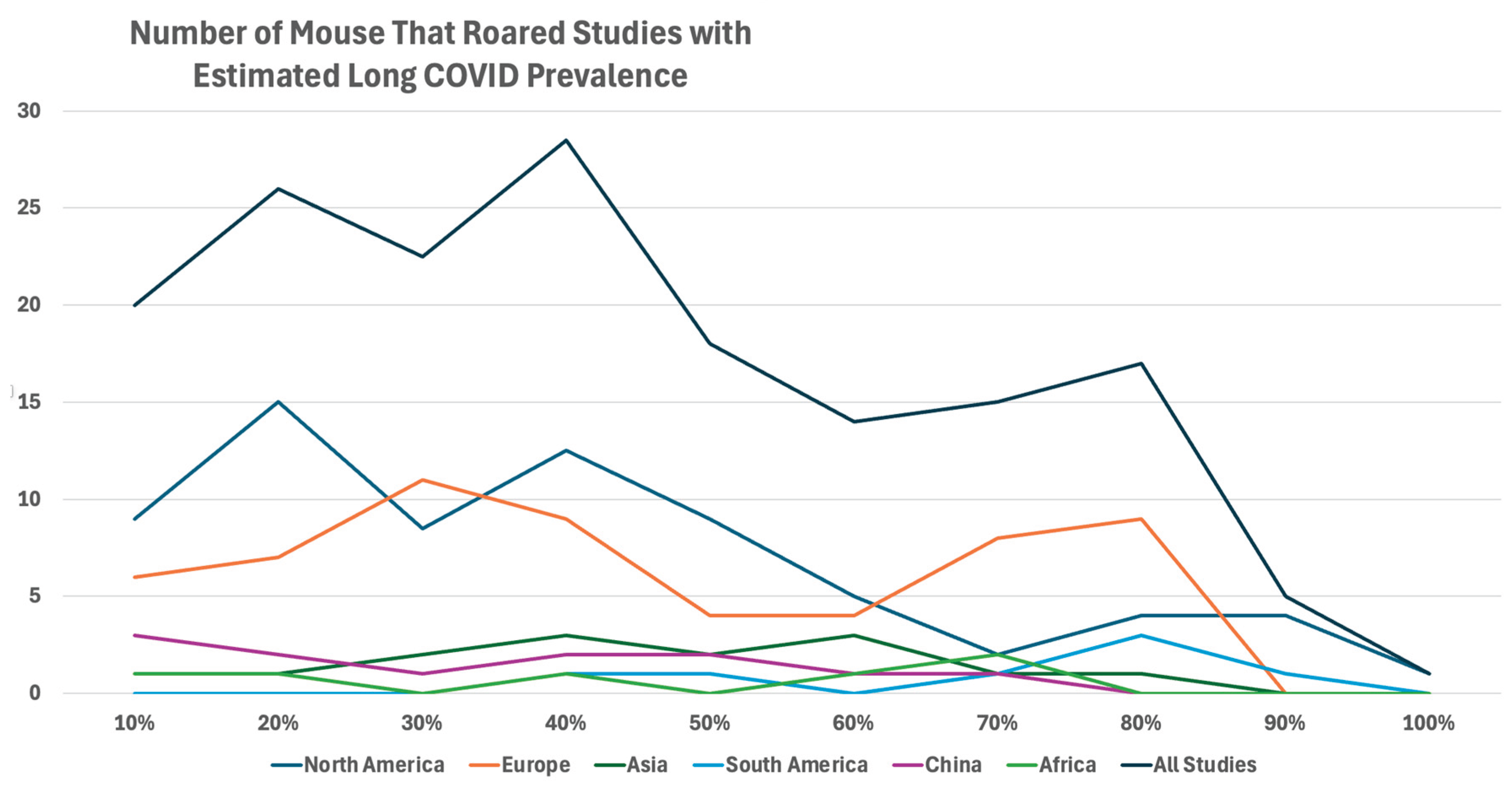

| The Mouse the Roared papersa | 3,800c | 269d |

| Symptom | FDA Clinical Trial |

| Fatigue | 279 |

| Mental Health | 138 |

| Persistent Infection | 106 |

| Inflammation | 66 |

| Brain Fog | 63 |

| Antiviral | 51 |

| Gut Micro biodome | 16 |

| Microclotting | 14 |

| Cognitive Behavioral Therapy to Treat It | 12 |

| SSRI Antidepressants to Treat It | 12 |

| Auto Immune Diseases | 12 |

| Mitochondrial | 11 |

| Dementia | 10 |

| Year |

Long COVID Trials Started |

| Pre 2020 | 2a |

| 2020 | 43 |

| 2021 | 120 |

| 2022 | 142 |

| 2023 | 155 |

| 2024 | 83 |

| 2025 - through 8/31 | 57 |

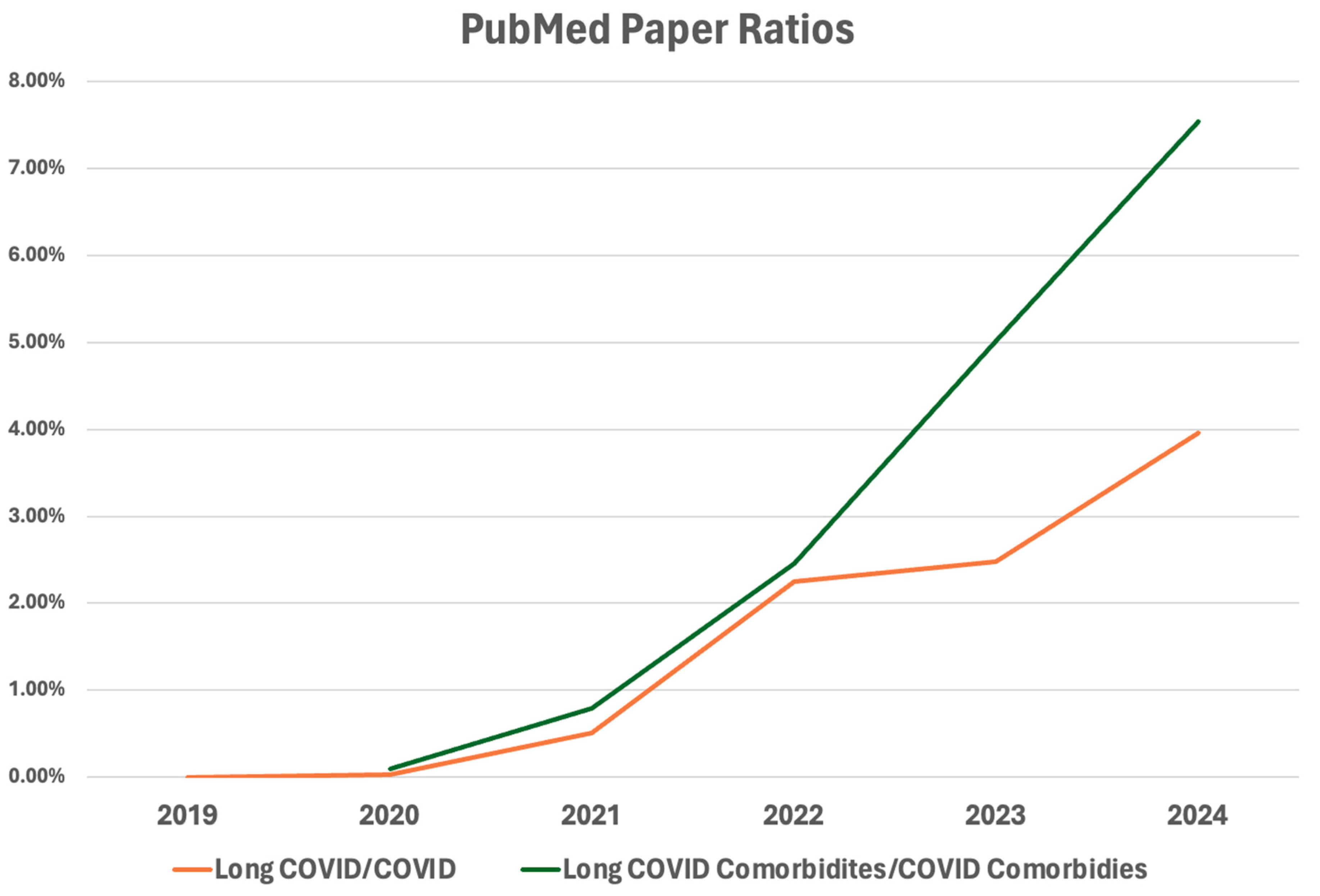

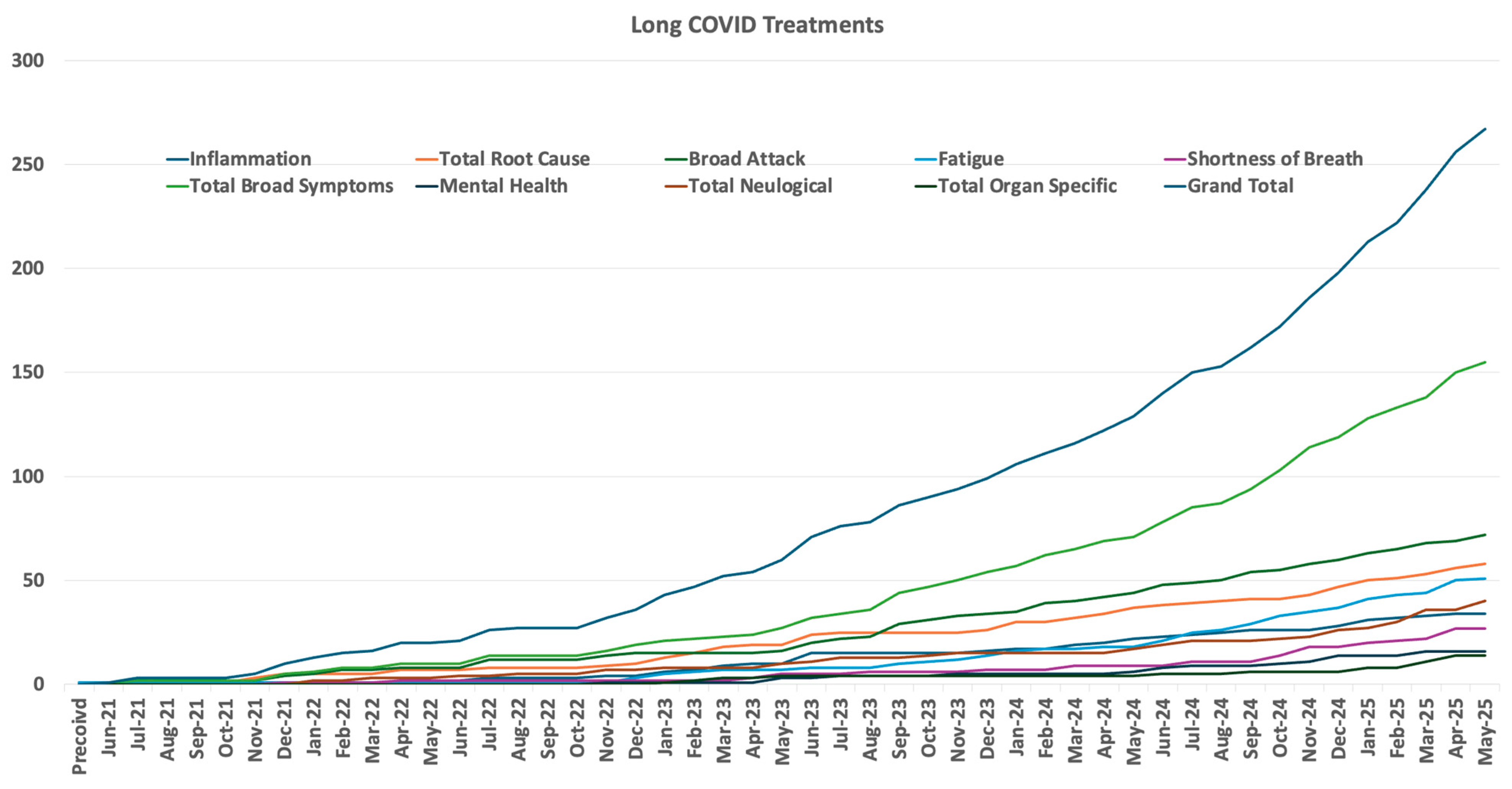

- The scientific community is early in focusing on Long COVID, so clearly other treatments will be discovered.

- The huge, order of $2.3 billion, US Long COVID project called Recover Project is just gathering momentum. This will be a long term, well-funded project if for no other reason than the order of 20 million Americans suffer from Long COVID. This website lists its published papers Recover Project Published Papers.

- Though not as large as the US Recover Project, many countries have large Long COVID projects including, but not limited to the UK, Canada, Australia, China, Japan, South Korea, the European Union, and the Word Health Organization.

- That is, the number of Long COVID treatment papers in The Mouse That Roared dropped precipitously in July and august 2025.

- Persistent Inflammation The main test for inflammation is for the IL-6 cytokine. Persistent Inflammation Test describes the test. Inflammation is probably the most important test as hyperinflammation is a leading cause of severe COVID which leads to the most severe cases of Long COVID.

- 2. Mitochondrial Dysfunction This is probably the second most important test. Initial laboratory tests such as lactate, pyruvate, urine organic acids, and plasma amino acids can inform the clinician about possible mitochondrial dysfunction.

- Persistent Infection The main tests are:

- 4.

- Autoantibodies Testing for autoantibodies triggered by COVID-19 involves specialized laboratory assays that detect the presence of antibodies targeting the body's own tissues. They are several types.

- Pre-existing health issues being sure to include any autoimmune disease and other COVID comorbidities such as diabetes, active cancer treatment, etc. This is important because as noted above, organ-specific comorbidities can increase the risk of COVID-caused organ damage.

- COVID case data, including COVID dates, tests, severity, and therapeutics.

- COVID vaccination history.

- Long COVID history - start date, symptom trends, and treatments. The Cleveland Clinic’s table is an excellent way to summarize Long COVID symptom data.

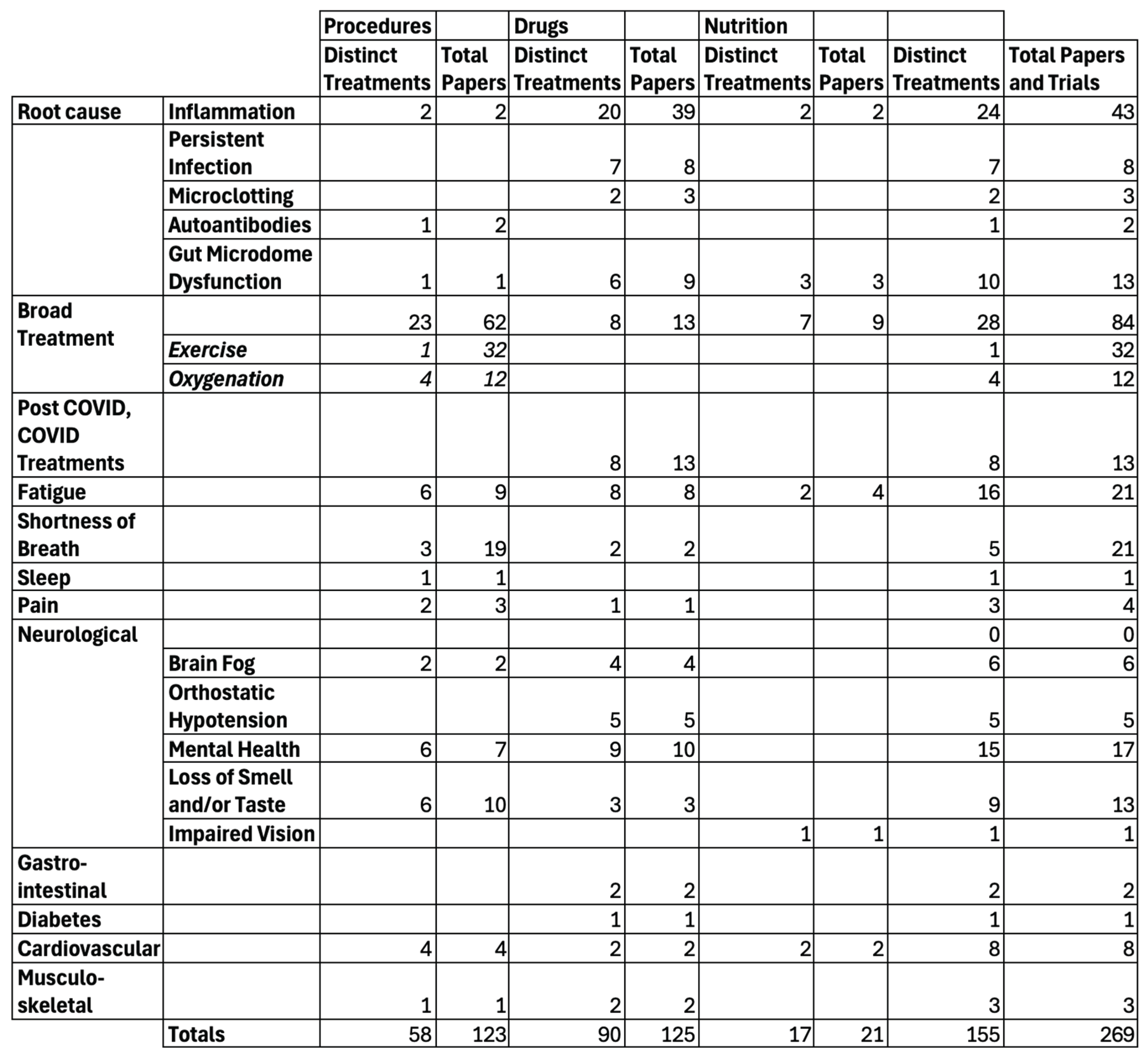

- Most of the root cause papers address inflammation.

- The choice of assigning a paper to Broad Symptoms or Root Cause/Inflammation was a bit arbitrary and was often based on the way the paper’s data was presented.

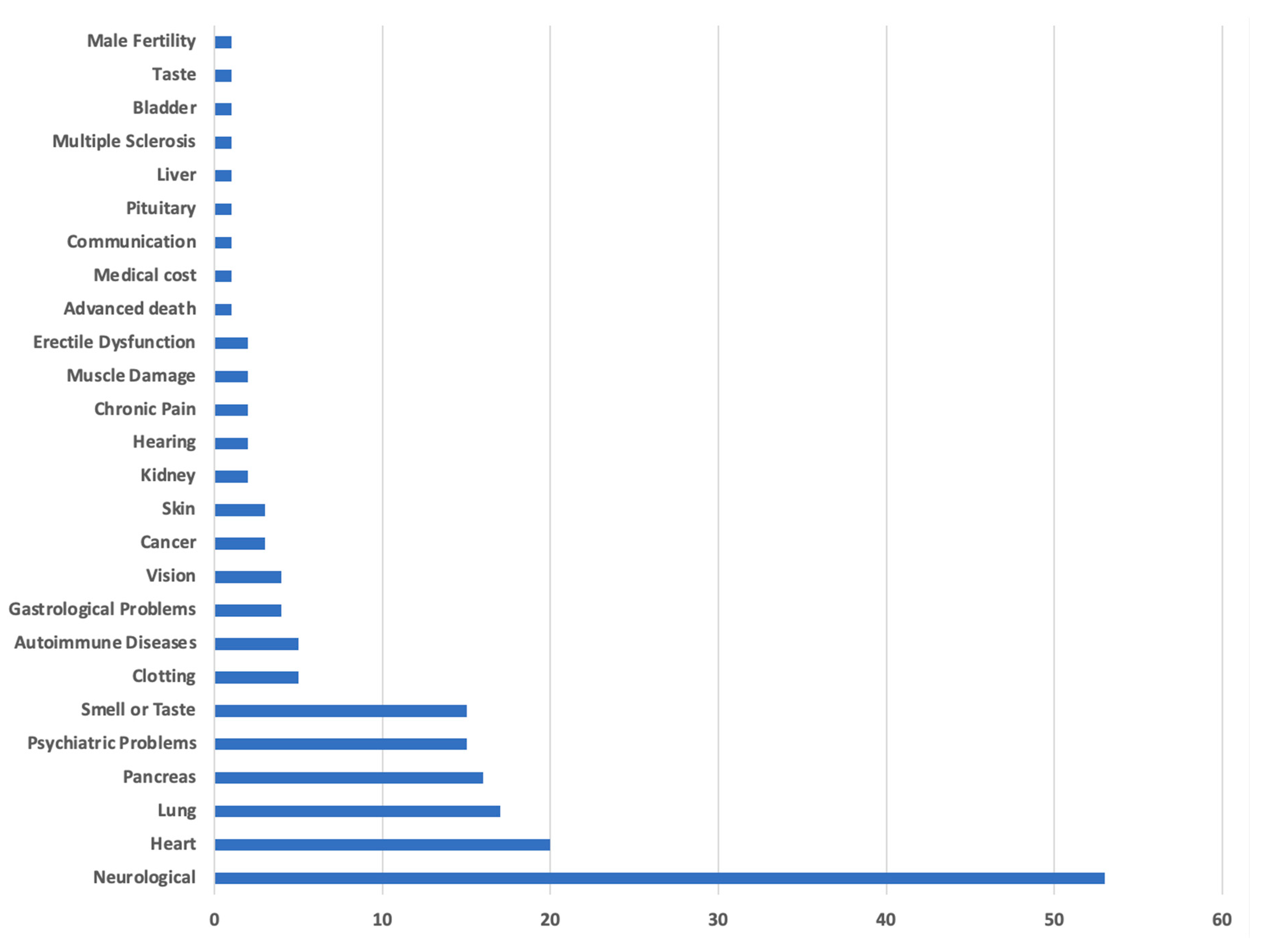

- Notice how few organ-specific papers were written. This is not surprising as treating arrythmia, for example, induced by Long COVID is likely little different than treating non-COVID arrythmias.

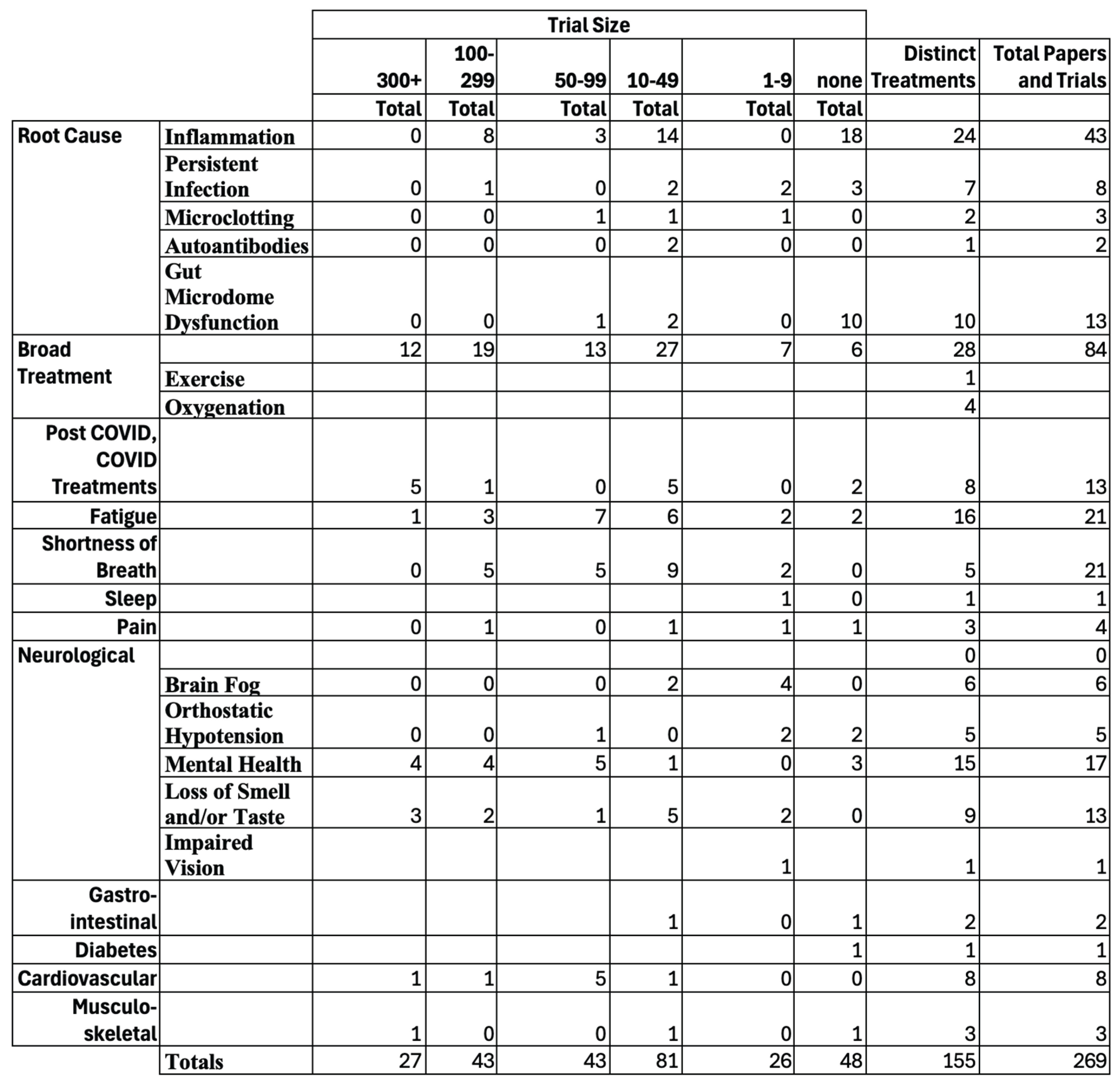

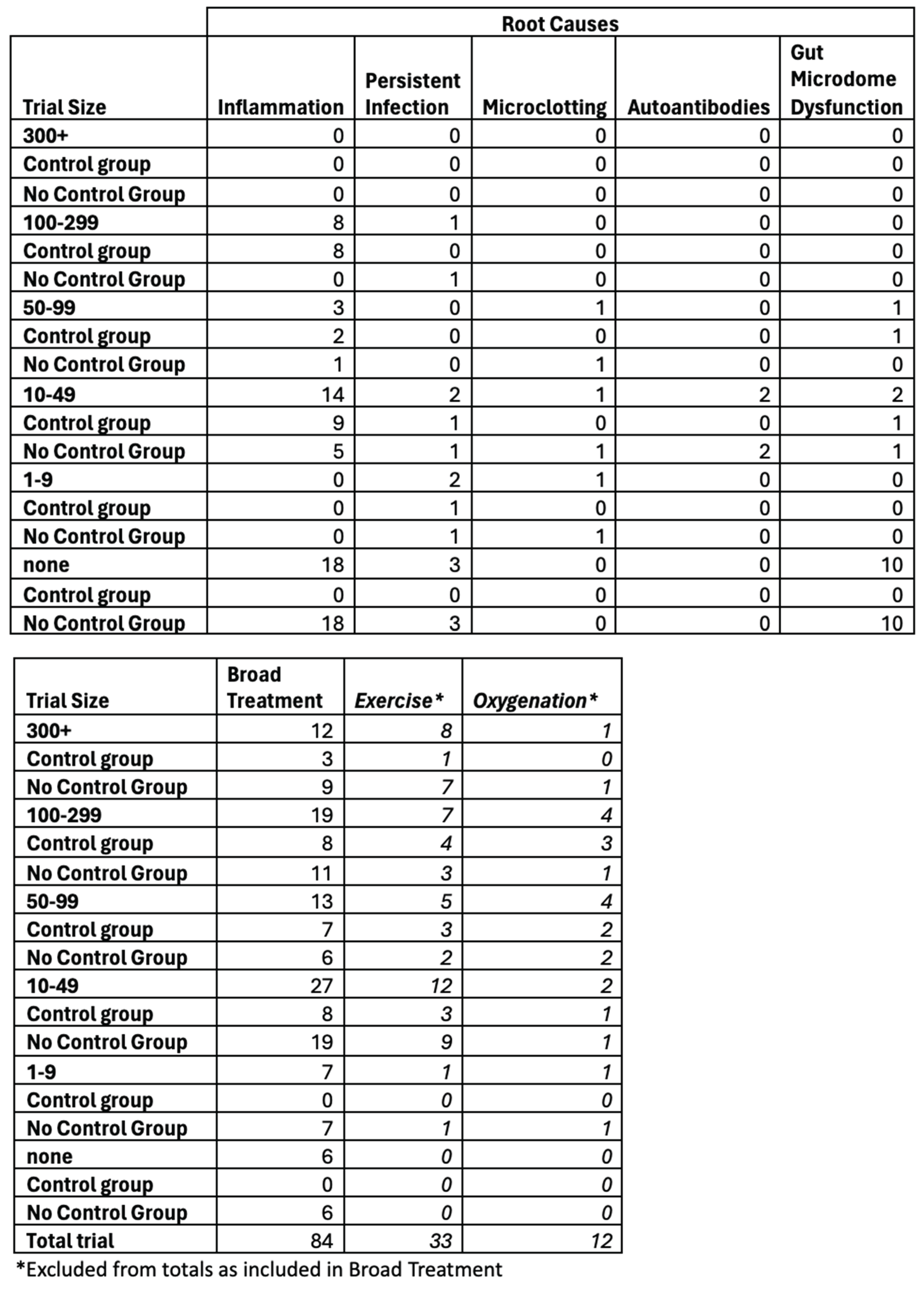

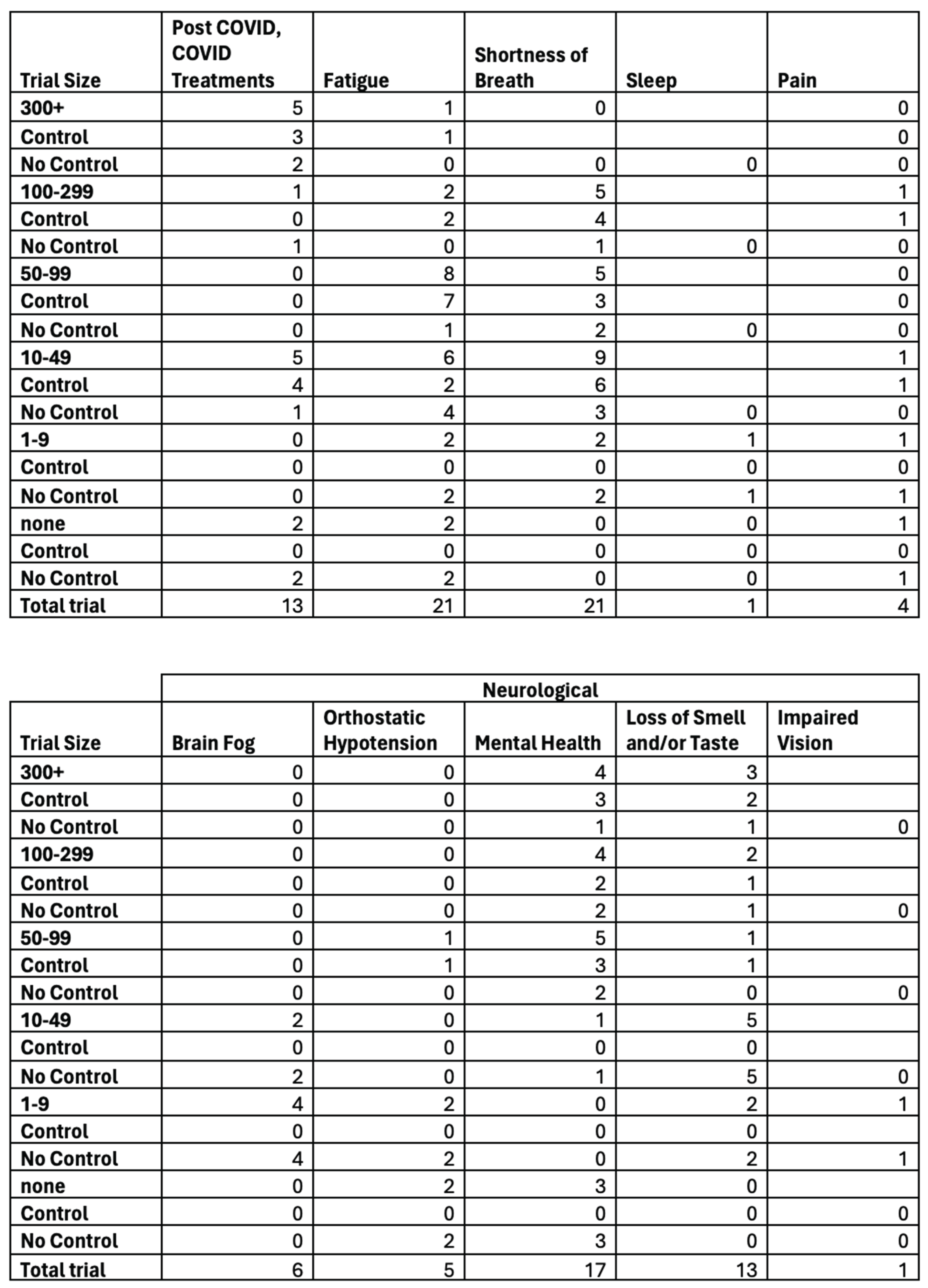

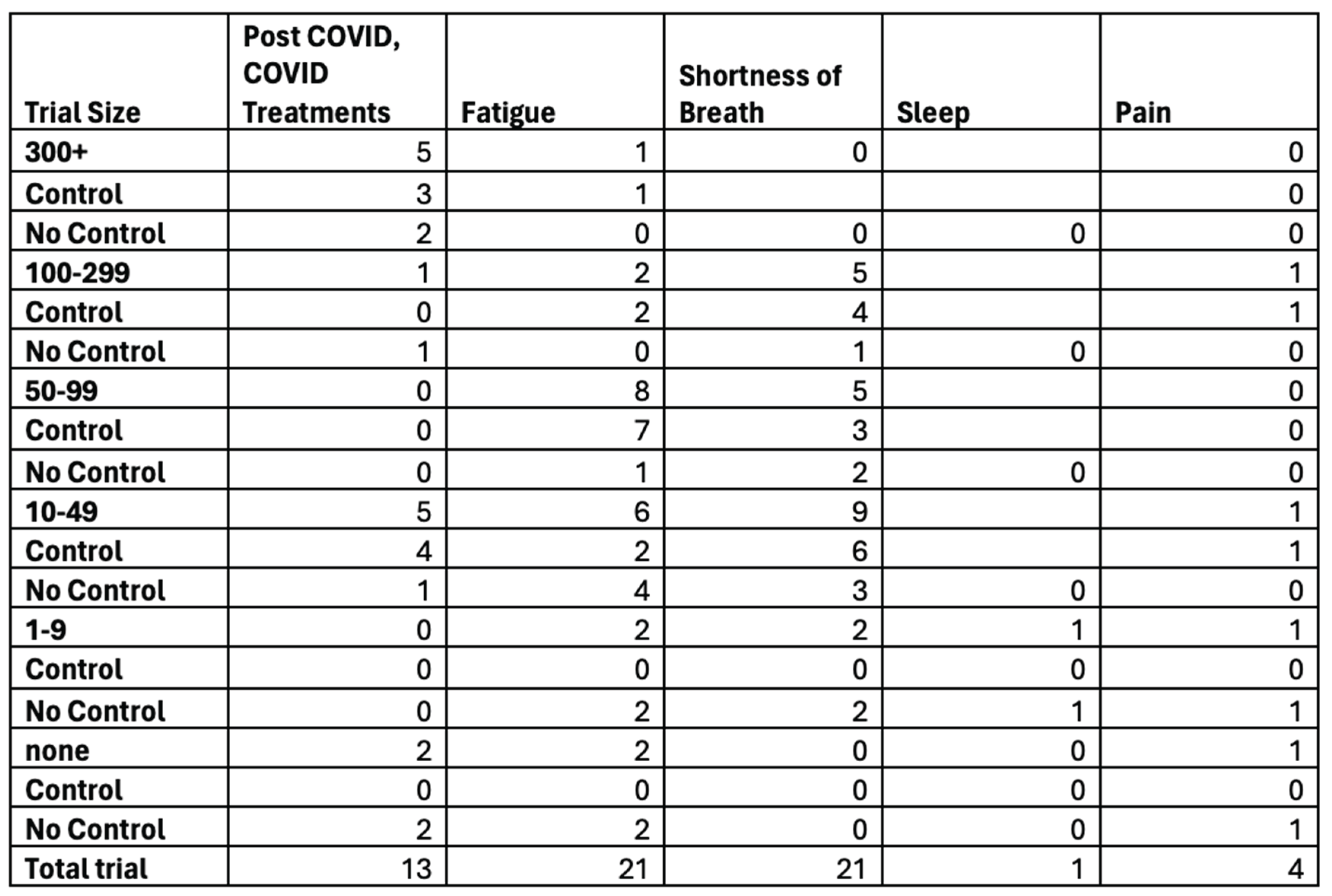

- Only 70 papers reported total human trial sizes of 100 or more. This would be the minimum size for an FDA phase 2 trial which determines a treatment’s effectiveness. Only 27 papers reported studies of 300 or more humans in their trials.

- If one combines trials into the group that had the largest number of people in one trial, then exercise studies accounted for more than 10% of the papers.

- Corticosteroids - prednisone or dexamethasone

- Colchicine

- 3. Low-Dose Naltrexone

- Antihistamines and Mast Cell Stabilizers

- Statins - atorvastatin, rosuvastatin

- Omega-3 fatty acids

- Palmitoylethanolamide

- Curcumin

- Resveratrol

- Q10

| Number of papers describing a treatment | Number of treatments |

| 6 | 1 |

| 5 | 1 |

| 4 | 1 |

| 3 | 6 |

| 2 | 18 |

| 1 | 107 |

- Reducing inflammation.

- Stimulating mitochondrial biogenesis and improve ATP production, which can reduce fatigue.

- Improving vascular tone, oxygen delivery, and tissue perfusion, potentially easing symptoms like brain fog or muscle aches.

- Rebalancing the autonomic nervous system through designed recumbent or supine exercise (e.g., rowing, swimming, recumbent cycling) which may help recondition the cardiovascular system and reduce orthostatic symptoms.

- Promoting neuroplasticity, potentially helping with cognitive symptoms (e.g., brain fog).

- Promoting lymphatic flow and helping clear cellular debris and immune complexes.

- Support fluid and waste clearance in the brain, helping with cognitive symptoms and sleep quality.

- Significantly increasing the amount of oxygen dissolved in the blood plasma, allowing more oxygen to reach tissues that may be oxygen-deprived or poorly cleared of fluids.

- Helping to reduce inflammation immune response.

- Promoting a more balanced immune function.

- Improving mitochondrial function, potentially increasing ATP production, reducing mitochondrial apoptosis signaling, and reducing oxidative stress. This leads to a boost in energy production and reduced fatigue.

- Stimulating the growth of new neurons and improved neuroplasticity thereby potentially improving cognitive function.

- Reducing chronic stress which increases inflammatory cytokines which are already elevated in Long COVID.

- Improving mood and symptom perception which may help people feel better, even if the underlying pathology remains.

- Improving sleep quality which can significantly reduce daily symptom burden and improve mitochondrial function.

- Regulating the autonomic nervous system which is linked to fatigue, and breathlessness.

- Improving cognitive function which can help cope with brain fog and develop compensatory strategies, even if they don't reverse the cause.

| Procedures | |||

| Trial Size | Treatment | Improvement | |

| 50-99 | Fecal Transplant [146] Enhanced External Counter Pulsation [147] Spinal Cord Transcutaneous Stimulation & Respiratory Training [148] Digital Cognitive Training [149] Unified Phycological Protocol [150] Wearable Brain Activity Sensing Device [151] Trained With Orange, Lavender, Clove And Peppermint Oils [152]- [3] Contracting And Relaxing Pneumatic Cuffs 0n The Calves, Thighs, And Lower Hip [154] |

Sleep Broad Lung Fatigue And Concentration Broad Broad Broad Impact Broad Impact |

|

| 25-49 | Immunoadsorption [155] Vagus Nerve Stimulation [156]- [158] Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation [159]- [161] Tragus Nerve Stimulation [162]- [163] Matt Pilates [164] Photobiomodulation [165]- [166] Stellate Ganglion Block [167]- [171] Ropinirole [172] Acupuncture [173] Expectation Management [174] |

Broad Broad Neurological Pain And Fatigue Broad Fatigue Pain And Fatigue Smell And Broad Restless Leg Syndrome Well Tolerated, No Measures On Outcomes Minor Broad |

|

| 10-24 | Dance [175] Aripiprazole [176] Continuous Positive Airway Pressure [177] Olfactory Training With Vitamin A [178] Functional Septorhinoplasty [179] Virtual Reality Training [180] Neuromodulation [181] |

Broad Reduced sleep duration Cognition No Impact Smell No Impact No Apparent Impact |

|

| 1-9 | Oronasal Drainage [182] Plasmapheresis [183]- [184] Light To Restore Circadian Rhythm [185] Neural Feedback [186] Plasma Exchange Therapy [187] |

Broad Cognition Sleep More Alert No Impact |

|

| Drugs | |||

| Trial Size | Treatment | Improvement | |

| 50-99 | Leronlimab [188] Sea Urchin Eggs [189] Co-UltraPEALut [190] Naltrexone [191]- [193] Antihistamines [194]- [195] Amantadine [196] Propranolol [197] Lithium [198] Metoprolol [199] Rintatolimod [200] Gabapentin [201] |

Inflammation Pain Memory & Fatigue Broad & Tremors Broad But Uneven Fatigue Orthostatic Hypotension No Improvement Cardiovascular No Impact No Impact |

|

| 25-49 | Valtrex + Celecoxib [202] AXA1125 [203] Plasma [204]- [205] Treamid [206] Palmitoylethanolamide Co-Ultramicronized With Luteolin [207]- [208] Phosphatidylcholine [209] Aripiprazole [210] Hochuekkito [211] |

Broad Fatigue Smell Improved Lung Capacity Improved Smell Improved Inconclusive Reduced Sleep Needs Reduced Fatigue |

|

| 10-24 | Creatine [212] | Fatigue | |

| 1-9 | Casirivimab/Imdevimab [213] Nicotine Patch [214] Bupropion [215] Methylphenidate [216] Guanfacine [217] Intravascular Immunoglobulin Therapy [218] Ivabradine [219] Minocycline [220] Epipharyngeal Abrasive Therapy [221] |

Complete Remission Broad And Major Broad Broad Cognition Orthostatic Hypotension Orthostatic Hypotension Orthostatic Hypotension Cleared Viral RNA |

|

| Nutrients | |||

| Trial Size | Treatment | Improvement | |

| 50-99 | Nutritional Supplements Plus Exercise222 Ayurveda System Of Medicine [223] Astragalus Root Extract [224] Marine Oils [225] Endocalyx [226] Glycocalyx Dietary Supplement [227] |

Broad Diarrhea And Broad Fatigue Fatigue Cardiovascular Cardiovascular |

|

| 25-49 | Beet Juice [228]- [229] Probiotics [230]- [231] Maraviroc And Pravastatin [232] |

Fatigue And Sleep Inflammation Broad |

|

| 10-24 | Salmon Oil [233] Tinospora Cordifolia [234] |

Inflammation Inflammation |

|

| Procedures | ||

| Infrared light [235] | Cell cultures | Two ten minute exposures led to 80% IL-6 reduction in gene assay. |

| Hyperthermia [236] | Review/ hypothosis | Modulates necroinflammation. |

| Drugs | ||

| Tocilizumab [237] | Trial underway | Reduce inflammation |

| Baricitinib [238] | Trial underway | Reduce inflammation |

| Peptide LTI-2355 [239] | Cell cultures | Mitigated inflammation in the respiratory tract. |

| CB2R agonists [240] | Hypothosis | Reduce inflammation |

| Ginkgolide B-loaded lubosomes And vesicular LNPS [241] | Human cell cultures | May protect against cell death |

| SPIKENET, SPK [242] |

Mice | Reversed the development of severe inflammation, oxidative stress, tissue edema, and animal death. Recall, vaccines in humans didn’t help. |

| Fermentable fiber [243] | Hypothesis | Reduce autoantibodies |

| Polyphenols [244] | Hypothesis | Reduce autoantibodies |

| Resveratrol [245] | Hypothesis | Reduce gut microdome dysfunction |

| Boost nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) [246] | Hypothesis | Reduce gut microdome dysfunction |

| Gamunex-C [247] | Proposed trial | Broad relief |

| Paracetamol and Dexketoprofen Trometamol [248] | Analytic technique | Broad relief when administered with rivaroxaban |

| Modafinil [249] | Literature search | Broad relief |

| Kyungok-go [250] | Proposed trial | Broad relief |

| Cyclobenzapring Hydochloride [251] |

Company annoucement | Reduce pain and improved sleep |

| Ivabradine and midodrine [252] | Review of 32 studies | Reduced brain fog |

| Omega-3 fatty acids [252] | Review | Improve mental health |

| Aspartate or Asparagine [253]- [254] | Hypothosis | Improve vision |

| Macitentan [255] | Hamsters | Restored bone loss |

| Tanshinone IIA [256] | Chemical evaluation | Inflammation |

| Epigallocatechin-3-gallate-palmitate [257] | Cell culture |

Neurological |

| Tuning Organelle Balance In Human Mesenchymal Stem Cell [258] | Cell Study | Major mitochondrial production |

| L-carnitine [259] | Theory | Fatigue |

| Niclosamide [260] | Review | Broad |

| Larazotide [261] | Proposed trial | Broad |

| Ecstasy [262] | FDA Vote | Too risky |

| Sodium Pyruvate Nasal Spray [263] | Proposed trial of drug useful in flu | Broad |

| Nutrients | ||

| Korean Herbs [264] | Mice cell cultures | Decreased nitrous oxide levels in some cell types. |

| Melatonin [265]- [268] | Hypothesis -3, Literature search | Reduce inflammation |

| Flavonoids Nobiletin & Eriodictyol [269] | Human cells | Reduced pathogen-stimulated release of inflammatory mediators. |

| Herbs [270] | Safety test | Broad improvements |

| Vitamin B12 [271] | Hypothesis | Improve vision |

- I believe I have Long COVID.

- I have the typical broad symptoms such as brain fog and fatigue.

- I have a fine GP who is not expert in Long COVID.

- I can’t get root cause diagnostic tests.

- Exercise – I would get a script to get physical therapy or use the Pace Me application

- Oxygenation – I would try to get to a hyperbaric chamber but if I couldn’t, I would do home oxygenation.

- Improve Mental Health – I would get Cognitive Behavioral therapy

- Spa & Hot Spring Bathing – Sure, why not! Fun and relaxing

- Mediterranean Diet – It has been shown to be good for one’s health, so why not?

- Fasting diet, no sugar – I would try it as it would be good for my general health

- Weight Loss - If I was overweight, definitely as it is good for one’s health

- Yoga – if I am healthy, I would pursue as part of my exercise program

- Contracting and Relaxing Pneumatic Cuffs on The Calves, Thighs, and Lower Hip – I would consider it even though it was a small trial

- SSRI Inhibitors

- Traditional Chinese Medicine

- SIM01 - Gut Microbiota-Derived Formula

- Transcutaneous Nicotine

- P2Y12 Inhibitor

- Prospekta

- Cyclobenzaprine Hydrochloride

- Vortioxetine

- Donepezil

- Bufei Huoxue

- Apportal

- L-carnitine - mitochondrial dysfunction though not reported in the papers discussed here.

- Q10 – though the trials were uneven, it has been shown to be good for mitochondrial dysfunction.

Conclusions

Acknowledgements

Appendix 1 – Summary of Long COVID Treatment Papers, Including Trial Sizes

Appendix 2 – Summary of Long COVID Treatments and Control Groups

References

- Ka Chun Chong, Yuchen Wei, Katherine Min Jia, Christopher Boyer, Guozhang Lin, Huwen Wang et al, SARS-CoV-2 rebound and post-acute mortality and hospitalization among patients admitted with COVID-19: cohort study (2025) https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-61737-7.

- Washington University School of Medicine in, St. Louis, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2024. Long-Term Health Effects of COVID-19: Disability and Function Following SARS-CoV-2 Infection Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [CrossRef]

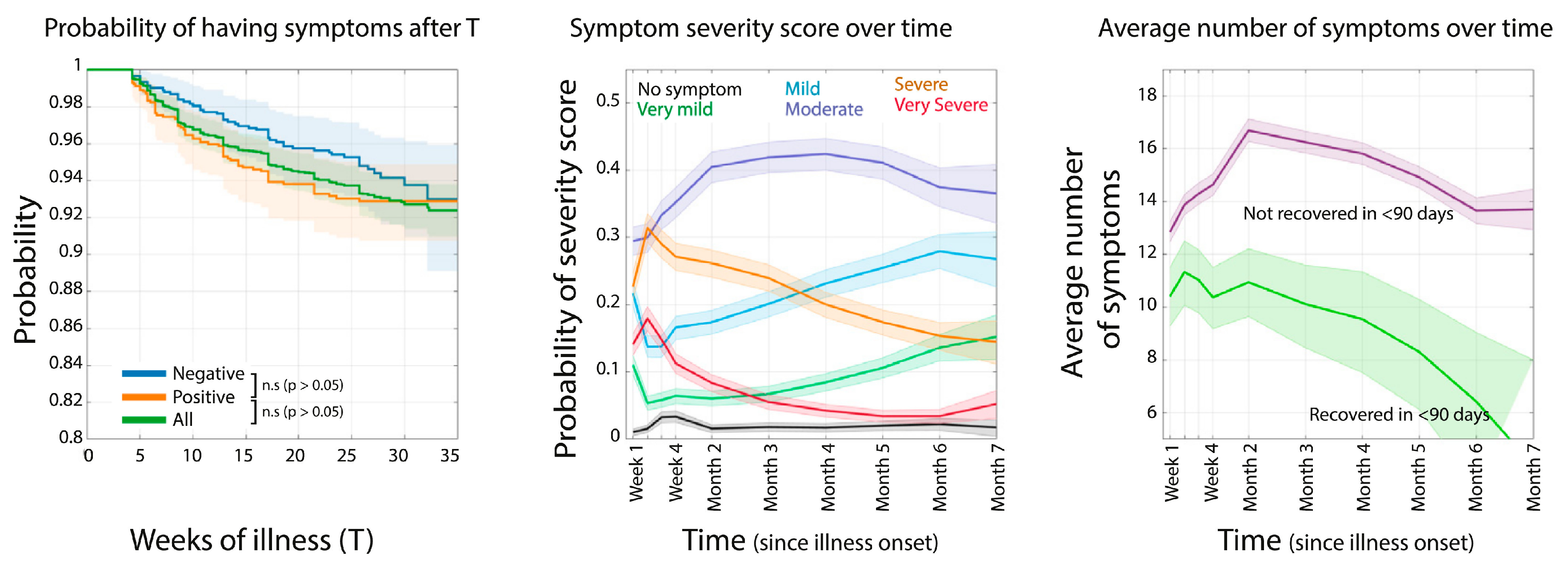

- Sudre, C.H.; Murray, B.; Varsavsky, T.; Graham, M.S.; Penfold, R.S.; Bowyer, R.C.; Pujol, J.C.; Klaser, K.; Antonelli, M.; Canas, L.S.; et al. Attributes and Predictors of Long COVID. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.E.; Assaf, G.S.; McCorkell, L.; Wei, H.; Low, R.J.; Re'Em, Y.; Redfield, S.; Austin, J.P.; Akrami, A. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. eClinicalMedicine 2021, 38, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasserie, T.; Hittle, M.; Goodman, S.N. Assessment of the Frequency and Variety of Persistent Symptoms Among Patients With COVID-19. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2111417–e2111417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC, Long COVID Signs and Symptoms, CDC (2025). https://www.cdc.gov/long-covid/signs-symptoms/index.

- Taquet, M.; Geddes, J.R.; Husain, M.; Luciano, S.; Harrison, P.J. 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert N, Survivor Corps. (2021). COVID-19 “Long Hauler” Symptoms Survey Report. Preprint. [CrossRef]

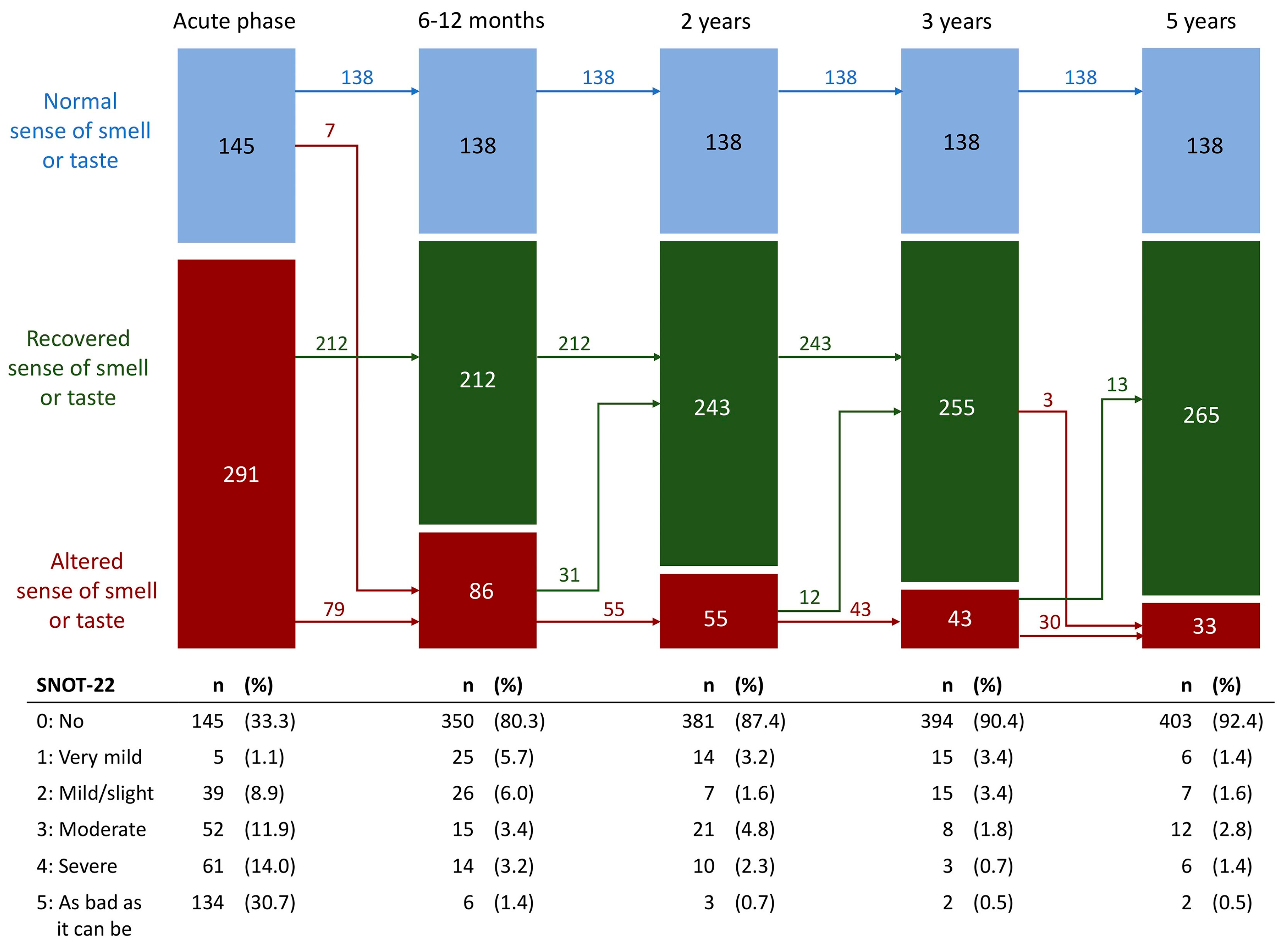

- Paolo Boscolo-Rizzo, Giacomo Spinato, Rebecca De Colle, Antonino Maniaci, Luigi Angelo Vaira, Enzo Emanuelli et al (2025) Five-Year Longitudinal Assessment of Self-reported COVID-19–Related Chemosensory Dysfunction, clinical Infectious Diseases https://academic.oup.com/cid/advance-article/doi/10. 1093.

- Ewing, A.G.; Salamon, S.; Pretorius, E.; Joffe, D.; Fox, G.; Bilodeau, S.; Bar-Yam, Y. Review of organ damage from COVID and Long COVID: a disease with a spectrum of pathology. Med Rev. 2024, 5, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC National Center for Health Statistics, Long COVID Pulse Study, (2024), https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/pulse/long-covid.

- Groff D, Sun A, Ssentongo AE, et al. (2021) Short-term and Long-term Rates of Post Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Systematic Review. JAMA Network Open. Volume 4, Issue 10: e2128568. https://jamanetwork. 2784.

- Winter COVID Analysis Team, (2024) Self-reported coronavirus (COVID-19) infections and associated symptoms, England and Scotland: 23 to March 2024, Office for National Statistics, https://www.ons.gov. 20 November 2023.

- Xie, Y.; Choi, T.; Al-Aly, Z. Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in the Pre-Delta, Delta, and Omicron Eras. New Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sara Carazo, Manale Ouakki, Nektaria Nicolakakis, Emilia Liana Falcone, Danuta M Skowronski, Marie-José Durand, Marie-France Coutu, Simon Décary et. A. 20 May; 25. [CrossRef]

- Bosworth, M.L.; Shenhuy, B.; Walker, A.S.; Nafilyan, V.; A Alwan, N.; E O’hara, M.; Ayoubkhani, D. Risk of New-Onset Long COVID Following Reinfection With Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2: A Community-Based Cohort Study. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, A.; Prasad, V. Long COVID clinics and services offered by top US hospitals: an empirical analysis of clinical options as of May 2023. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, D.P.; Bast, E.; Trinh, H.; Fox, A.; Berkowitz, T.S.Z.; Palacio, A.; Wander, P.L.; O’hAre, A.M.; Boyko, E.J.; Ioannou, G.N.; et al. Use of Long COVID Clinics in the Veterans Health Administration: Implications for the path forward. Heal. Aff. Sch. 2025, 3, qxaf080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, Clinical Management of COVID-19: living guilders https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/381920/B09467-eng.pdf?

- Raffaele Sarnataro, Cecilia D. Velasco, Nicholas Monaco, Anissa Kempf & Gero Miesenböck (2025) Mitochondrial origins of the pressure to sleep, Nature https://www.nature. 4158.

- T cells require mitochondria to proliferate, function and generate memory, Nature https://www.nature. 4159.

- Zong, Y.; Li, H.; Liao, P.; Chen, L.; Pan, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, D.; Zheng, M.; Gao, J. Mitochondrial dysfunction: mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, K.B.; Weng, Z.; Graham, Z.A.; Lavin, K.; McAdam, J.; Tuggle, S.C.; Peoples, B.; Seay, R.; Yang, S.; Bamman, M.M.; et al. Exercise intensity and training alter the innate immune cell type and chromosomal origins of circulating cell-free DNA in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2025, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corna, S. , Arcolin, I., Giardini, M., Bellotti, L., Godi, M., & Corna, M. Effects of adding an online exercise program on physical function in individuals hospitalized by COVID 19: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), 16619. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/19/24/16619 (2022, December 10).

- Kim, K.-H.; Kim, D.-H. Effects of Maitland Thoracic Joint Mobilization and Lumbar Stabilization Exercise on Diaphragm Thickness and Respiratory Function in Patients with a History of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 17044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupferschmitt, A. , Langheim, E., Tüter, H., Etzrodt, F., Loew, T. H., & Köllner, V. First results from post COVID inpatient rehabilitation: An observational study comparing post COVID, psychosomatic, and psychocardiological patients. Frontiers in Rehabilitation Science. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fresc.2022.1093871/full (2023, ). 23 January.

- Feng, B. , Li, H., Wang, X., Zhao, Y., Guo, S., & Zhang, J. et al. Post-hospitalization rehabilitation alleviates long-term immune repertoire alteration in COVID-19 convalescent patients. Cell Proliferation, 56(3), e13450. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36938980/ (2023, March).

- Zhou, L. , Jamshidi, N., Huang, Q., Li, Y., Chen, X., et al. Correction of immune repertoire alteration by post hospital rehabilitation in convalescent COVID 19 patients. Cell Proliferation, 57(2), e13345. [CrossRef]

- Romanet, C. , Wormser, J., Fels, A., Lucas, P., Prudat, C., Sacco, E., et al. Effectiveness of exercise training rehabilitation on dyspnoea in individuals with long COVID following COVID 19 related acute respiratory distress syndrome: A multicentre randomized controlled trial. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 66(5), 101765. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37271020/ (2023, June).

- Al Zaabi, E. , Balushi, W., Al-Falahi, E., Al Balushi, Y., & Singh, R. Effects of a 6 week telerehabilitation program on functional capacity and pulmonary function in individuals with Long COVID. medRxiv. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.09.27. 2329. [Google Scholar]

- (2023).

- Dubey, A. , Desvaux, G., Sahuquillo-Arce, I., Bonnet, G., Fartoukh, M., et al. Endurance training versus standard physiotherapy for breathlessness after COVID 19 acute respiratory distress syndrome: assessor blinded randomized controlled trial. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 66(6), 101280. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10237688/ (2023).

- Gravina, F. , Zampogna, E., Hu, C., Camicioli, F., Turano, I., et al. Continuous versus interval aerobic endurance training improves physical capacity and wellbeing in post COVID syndrome patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(10), 3478. https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/12/21/6739 (2023).

- François-Michel Boisvert, André M Cantin, Hugues Allard-Chamard Mohammad, Mobarak H Chowdhury, Isabelle J Dionne Marie-Noelle Fontaine, Marc-André Limoges, et al Impact of a tailored exercise regimen on physical capacity and plasma proteome profile in post-COVID-19 condition. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih. 20 August 1137.

- REGAIN collaborators, S. Rehabilitation Exercise and psychological support After covid-19 Infection (REGAIN): randomized trial of home based rehabilitation. BMJ, 382, 070742 https://bmjopen.bmj. 0859. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Ma, H.; He, X.; Gu, X.; Ren, Y.; Yang, H.; Tong, Z. Efficacy of early pulmonary rehabilitation in severe and critically ill COVID-19 patients: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pulm. Med. 2025, 25, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serena Cerfoglio, Federica Verme, Paolo Capodaglio, Paolo Rossi, Viktoria Cvetkova, Gabriele Boldini et al Home based tele rehabilitation enhances respiratory and motor function post COVID: 3 week program evaluation. Preprints.org. https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202406. 0424.

- Giulia Di Martino, Marco Centorbi, Andrea Buonsenso, Giovanni Fiorilli, Carlo Della Valle, Giuseppe Calcagno et al Post Traumatic Stress Disorder 4 Years after the COVID 19 Pandemic in Children and Adolescents – Is an Active Lifestyle Protective? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 21(8):975. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih. 3920.

- Binabaji B, et al. Effects of physical training on coagulation parameters, interleukin-6 and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in COVID 19 survivors. Nat Sci Rep. 8:67522. https://www.nature. 4159.

- Rasmussen, I.E.; Løk, M.; Durrer, C.G.; Lytzen, A.A.; Foged, F.; Schelde, V.G.; Budde, J.B.; Rasmussen, R.S.; Høvighoff, E.F.; Rasmussen, V.; et al. Impact of a 12-week high-intensity interval training intervention on cardiac structure and function after COVID-19 at 12-month follow-up. Exp. Physiol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoe Sirotiak, Duck-Chul Lee, Angelique G Brellenthin Associations between physical activity, long COVID symptom intensity, and perceived health among individuals with long COVID. Front Psychol. 15:1498900. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih. 3950.

- Kieffer, S.; Krüger, A.-L.; Haiduk, B.; Grau, M. Individualized and Controlled Exercise Training Improves Fatigue and Exercise Capacity in Patients with Long-COVID. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Herrera, S.; Oliván-Blázquez, B.; Sánchez-Recio, R.; Méndez-López, F.; Magallón-Botaya, R.; Sánchez-Arizcuren, R. Effectiveness of an online multimodal rehabilitation program in long COVID patients: a randomized clinical trial. Arch. Public Heal. 2024, 82, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez, García; et al. “Increased physical performance and reduced fatigue after personalised physiotherapy and nutritional counselling in Long COVID.” Research Square. Preprint. https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-4914245/v1 (Dec 2024).

- Barz A, Berger J, Speicher M, et al. “Effects of a symptom titrated exercise program on fatigue and quality of life in people with post COVID condition – a randomized controlled trial.” Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):82584. https://www.nature. 4159.

- Tania Janaudis-Ferreira, Marla K. Beauchamp, Amanda Rizk, Catherine M. Tansey, Maria Sedeno, Laura Barreto et al “Virtual rehabilitation for individuals with Long COVID: a randomized controlled trial.” fullhttps://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.11.24. 2431.

- Belinda Godfrey, Jenna Shardha, Sharon Witton, Rochelle Bodey, Fachel Tarrant, Darren C. Greenwood et al. “A Personalised Pacing and Active Rest Rehabilitation Programme using an 8 week WHO Borg CR 10 protocol in long COVID.” J Clin Med. 2024;13(1):97. https://www.mdpi. 2077.

- PoCoRe Study Group (Kerling A, et al.). “Neuropsychological outcome of indoor rehabilitation in post COVID condition.” Front Neurol. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neurology/articles/10.3389/fneur.2024.1486751/full (2025).

- Bileviciute-Ljungar, I.; Apelman, A.; Braconier, L.; Östhols, S.; Norrefalk, J.-R.; Borg, K. A First Randomized Eight-Week Multidisciplinary Telerehabilitation Study for the Post-COVID-19 Condition: Improvements in Health- and Pain-Related Parameters. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colin Berry, Gemma McKinley, Hannah Bayes, David Anderson, Chim Lang, Adam Gill, Andrew Morrow, et al. “Resistance Exercise Therapy for Long COVID: a Randomized, Controlled Trial.” Research Square. https://www.researchgate. 20 March 3903.

- Stijn Roggeman, Berenice Jimenez Garcia, Lynn Leemans, Elisabeth De Waele, et al. Faster functional performance recovery after individualized nutrition therapy combined with a patient-tailored physical rehabilitation program versus standard physiotherapy in patients with long COVID: a pilot study for a randomized, controlled single-center tria https://www.researchgate.net/publication/370149175_Faster_functional_performance_recovery_after_individualized_nutrition_therapy_combined_with_a_patient-tailored_physical_rehabilitation_program_versus_standard_physiotherapy_in_patients_with_long_COVID (22). 20 December.

- Yakpogoro, N.; Huskey, A.; Kennedy, K.; Grandner, M.; Green, S.; Killgore, W. 1409 Exercise Modality and Sleep-Related Interference of Daily Functioning in COVID-19: Comparative Effects of Cardio and Strength Training. Sleep 2025, 48, A606–A606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, S.; Gürbüz, A. Investigation of respiratory muscle strength, exercise capacity and sleep quality level in post-COVID-19 Individuals: case-control study. Adv. Rehabilitation 2025, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison Maher, Michelle Bennett, Hsin-Chia Carol Huang, Philip Gaughwin, Mary Johnson, Madeleine Brady et al Personalized Exercise Prescription in Long COVID: A Practical Toolbox for a Multidisciplinary Approach URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC11330745/ (24). 20 August.

- FDS Clinical Trial Nutrition and LOComotoric Rehabilitation in Long COVID-19). URL: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05254301 (Registered Feb 24, 2022).

- Grzegorz Onik, Katarzyna Knapik, Dariusz Górka & Karolina Sieroń Health Resort Treatment Mitigates Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Long COVID Patients: A Retrospective Study. Healthcare, 13(2), 52. https://www.mdpi. 2227.

- Carpallo-Porcar, B.; Beamonte, E.d.C.; Jiménez-Sánchez, C.; Córdova-Alegre, P.; la Cruz, N.B.-D.; Calvo, S. Multimodal Telerehabilitation in Post COVID-19 Condition Recovery: A Series of 12 Cases. Reports 2025, 8, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Herrera, S.; Samper-Pardo, M.; Oliván-Blázquez, B.; Magallón-Botaya, R.; Casado-Vicente, V.; Sánchez-Recio, R.; Sánchez-Arizcuren, R. Effectiveness of ReCOVery APP to Improve the Quality of Life of Long COVID Patients: A 6-Month Follow-Up Randomized Clinical Trial. Int. J. Clin. Pr. 2025, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanal-Hayes, N. E. M., Hayes, L. D., Mair, J. L., Dello Iacono, A., Ingram, J., Ormerod, J., et al. A digital platform with activity tracking for energy management support in long COVID: A randomised controlled trial. SSRN. Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5122498 (2025, February).

- Maccarone, M.C.; Contessa, P.; Passarotto, E.; Regazzo, G.; Masiero, S. Balance rehabilitation and Long Covid syndrome: effectiveness of thermal water treatment vs. home-based program. Front. Rehabilitation Sci. 2025, 6, 1588940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullan, C.; Haroon, S.; Turner, G.; Aiyegbusi, O.L.; Hughes, S.E.; Flanagan, S.; Subramanian, A.; Nirantharakumar, K.; Davies, E.H.; Frost, C.; et al. Mixed methods study of views and experience of non-hospitalised individuals with long COVID of using pacing interventions. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, C.; Vincent, T.; Bherer, L.; Gayda, M.; Cloutier, S.-O.; Nozza, A.; Guertin, M.-C.; Blaise, P.; Cloutier, I.; Kamada, A.; et al. Oxygen supplementation and cognitive function in long-COVID. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0312735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doehner, W.; Fischer, A.; Alimi, B.; Muhar, J.; Springer, J.; Altmann, C.; Schueller, P.O. Intermittent Hypoxic–Hyperoxic Training During Inpatient Rehabilitation Improves Exercise Capacity and Functional Outcome in Patients With Long Covid: Results of a Controlled Clinical Pilot Trial. J. Cachex- Sarcopenia Muscle 2024, 15, 2781–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapel, J.S.; Stokholm, R.; Elmengaard, B.; Nochi, Z.; Olsen, R.J.; Foldager, C.B. Individualized Algorithm-Based Intermittent Hypoxia Improves Quality of Life in Patients Suffering from Long-Term Sequelae After COVID-19 Infection. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilberman-Itskovich, S.; Catalogna, M.; Sasson, E.; Elman-Shina, K.; Hadanny, A.; Lang, E.; Finci, S.; Polak, N.; Fishlev, G.; Korin, C.; et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy improves neurocognitive functions and symptoms of post-COVID condition: randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitman, M.; Fuchs, S.; Tyomkin, V.; Hadanny, A.; Zilberman-Itskovich, S.; Efrati, S. The effect of hyperbaric oxygen therapy on myocardial function in post-COVID-19 syndrome patients: a randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadanny, A.; Zilberman-Itskovich, S.; Catalogna, M.; Elman-Shina, K.; Lang, E.; Finci, S.; Polak, N.; Shorer, R.; Parag, Y.; Efrati, S. Long term outcomes of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in post covid condition: longitudinal follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, K.E.J.; Owles, H.; McVey, S.; Pagnuco, T.; Bruce, K.; Brunjes, H.; Banya, W.; Mollica, J.; Lound, A.; Zumpe, S.; et al. An online breathing and wellbeing programme (ENO Breathe) for people with persistent symptoms following COVID-19: a parallel-group, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022, 10, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- del Corral, T. , Fabero-Garrido, R., Plaza Manzano, G., Fernández de las Peñas, C., Navarro Santana, M. J., & López de Uralde Villanueva, I. Minimal clinically important differences in inspiratory muscle function variables after a respiratory muscle training programme in individuals with long term post COVID 19 symptoms. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(7), Article 2720. https://www.mdpi. 2077. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.-J. Thoracic Mobilization and Respiratory Muscle Endurance Training Improve Diaphragm Thickness and Respiratory Function in Patients with a History of COVID-19. Medicina 2023, 59, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo Muñoz-Cofré, María Fernanda del Valle, Gabriel Nasri Marzuca-Nassr, Jorge Valenzuela, Mariano del Sol, Constanza Díaz Canales et al A pulmonary rehabilitation program is an effective strategy to improve forced vital capacity, muscle strength and functional exercise capacity similarly in adults and older people with post severe COVID 19 who required mechanical ventilation. Research Square (preprint). https://www.researchgate. 3795.

- Elyazed, T.I.A.; Alsharawy, L.A.; Salem, S.E.; Helmy, N.A.; El-Hakim, A.A.E.-M.A. Effect of home-based pulmonary rehabilitation on exercise capacity in post COVID-19 patients: a randomized controlled trail. J. Neuroeng. Rehabilitation 2024, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauro, M.; Zulian, E.; Bestiaco, N.; Polano, M.; Filon, F.L. Slow-Paced Breathing Intervention in Healthcare Workers Affected by Long COVID: Effects on Systemic and Dysfunctional Breathing Symptoms, Manual Dexterity and HRV. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parisi, M.C.; Di Corrado, D.; Mingrino, O.; Crescimanno, C.; Longo, F.; Pegreffi, F.; Francavilla, V.C. SpiroTiger and KS Brief Stimulator: Specific Devices for Breathing and Well-Being in Post-COVID-19 Patients. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2024, 9, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Cofré, R.; del Valle, M.F.; Marzuca-Nassr, G.N.; Valenzuela, J.; del Sol, M.; Canales, C.D.; Lizana, P.A.; Valenzuela-Aedo, F.; Lizama-Pérez, R.; Escobar-Cabello, M. A pulmonary rehabilitation program is an effective strategy to improve forced vital capacity, muscle strength, and functional exercise capacity similarly in adults and older people with post-severe COVID-19 who required mechanical ventilation. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Páez-Mora, C.D.; Zona, D.C.; Angarita-Sierra, T.; E Rojas-Paredes, M.; Cano-Trejos, D. Changes in lung function and dyspnea perception in Colombian Covid-19 patients after a 12-week pulmonary rehabilitation program. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0300826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandao-Rangel, M.A.R.; Brill, B.; Furtado, G.E.; Freitas-Rolim, C.C.L.; Silva-Reis, A.; Souza-Palmeira, V.H.; Moraes-Ferreira, R.; Lopes-Silva, V.; Albertini, R.; Fernandes, W.S.; et al. Exercise-Driven Comprehensive Recovery: Pulmonary Rehabilitation’s Impact on Lung Function, Mechanics, and Immune Response in Post-COVID-19 Patients. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2025, 17, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P, R.; Saravanan, A.; Maheshkumar, K.; ThamaraiSelvi, K.; Praba, P.K.; Prabhu, V. Effects of Bhramari and Sheetali Pranayama on Cardio Respiratory Function in Post-COVID Patients: A Randomised Controlled Study. Ann. Neurosci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casciaro, M. , Di Micco, P., Tonacci, A., Vatrano, M., Russo, V., & Siniscalchi, C. Non invasive ventilation improves lung function and exercise capacity in adults after COVID 19 infection. Clinical Practice, 15(4), Article 72. https://www.mdpi. 2039. [Google Scholar]

- Promsrisuk, T.; Srithawong, A.; Kongsui, R.; Sriraksa, N.; Thongrong, S.; Kloypan, C.; Muangritdech, N.; Khunkitti, K.; Thanawat, T.; Chachvarat, P. Therapeutic Effects of Slow Deep Breathing on Cardiopulmonary Function, Physical Performance, Biochemical Parameters, and Stress in Older Adult Patients with Long COVID in Phayao, Thailand. Ann. Geriatr. Med. Res. 2025, 29, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Kuut, T.; Müller, F.; Csorba, I.; Braamse, A.; Aldenkamp, A.; Appelman, B.; Assmann-Schuilwerve, E.; E Geerlings, S.; Gibney, K.B.; A A Kanaan, R.; et al. Efficacy of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Targeting Severe Fatigue Following Coronavirus Disease 2019: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 77, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nerli, T.F. , Selvakumar, J., Cvejic, E., Heier, I., Pedersen, M., Johnsen, T.L., & Wyller, V.B. Brief outpatient rehabilitation program for post–COVID 19 condition: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Network Open, 7(12), e2450744. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39699896/ (2024).

- Aghaei, A.; Qiao, S.; Tam, C.C.; Yuan, G.; Li, X. Role of self-esteem and personal mastery on the association between social support and resilience among COVID-19 long haulers. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovejero, D.; Ribes, A.; Villar-García, J.; Trenchs-Rodriguez, M.; Lopez, D.; Nogués, X.; Güerri-Fernandez, R.; Garcia-Giralt, N. Balneotherapy for the treatment of post-COVID syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2025, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, E.; Scaramuzzino, M.; Murmura, G.; D’addazio, G.; Sinjari, B. Emerging Evidence on Balneotherapy and Thermal Interventions in Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbsch, R.; Kotewitsch, M.; Schäfer, H.; Teschler, M.; Mooren, F.C.; Schmitz, B. Use of speleotherapy in patients with post-COVID-19 syndrome. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1566235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornazieri, M.A.; Cunha, B.M.; Nicácio, S.P.; Anzolin, L.K.; da Silva, J.L.B.; Neto, A.F.; Neto, D.B.; Voegels, R.L.; Pinna, F.D.R. Effect of drug therapies on self-reported chemosensory outcomes after COVID-19. World J. Otorhinolaryngol. - Head Neck Surg. 2024, 10, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pretorius, E. , Venter, C., Laubscher, G., Kell, D. B., & et al. Treatment of Long COVID symptoms with triple anticoagulant therapy: Dual antiplatelet therapy (clopidogrel + aspirin) and apixaban resolved persistent symptoms by reducing microclot burden and platelet hyperactivation. Research Square (Preprint). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/369427800_Treatment_of_Long_COVID_symptoms_with_triple_anticoagulant_therapy (2023, March).

- Pretorius, E.; Venter, C.; Laubscher, G.J.; Kotze, M.J.; Oladejo, S.O.; Watson, L.R.; Rajaratnam, K.; Watson, B.W.; Kell, D.B. Prevalence of symptoms, comorbidities, fibrin amyloid microclots and platelet pathology in individuals with Long COVID/Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC). Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2022, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idelette Nutma, Carla Rus, J. J. Sandra Kooij, Bert de Vries & Ingmar E.J. de Vries. Treatment and outcomes of 95 post-Covid patients with an antidepressant and neurobiological explanations. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/372334231_Treatment_and_outcomes_of_95_post-Covid_patients_with_an_antidepressant_and_neurobiological_explanations (2023).

- Treatment of 95 post-Covid patients with SSRIs: exploratory questionnaire study of post-COVID syndrome patients. Nature. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37919310/ (2023, November).

- Bradley, J.; Tang, F.; Tosi, D.; Resendes, N.; Hammel, I.S. The Effects of SSRIs and Antipsychotics on Long COVID Development in a Large Veteran Population. COVID 2024, 4, 1694–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, L. L., Behl, S., Lee, D., Zeng, H., Skubiak, T., Weaver, S. et al. Brexpiprazole and sertraline for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 332(21), 2144–2154. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapsychiatry/fullarticle/2827796 (2024).

- Augustin, M.; Stecher, M.; Wüstenberg, H.; Di Cristanziano, V.; de Silva, U.S.; Picard, L.K.; Pracht, E.; Rauschning, D.; Gruell, H.; Klein, F.; et al. 15-month post-COVID syndrome in outpatients: Attributes, risk factors, outcomes, and vaccination status - longitudinal, observational, case-control study. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1226622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, L.; Motloch, L.J.; Dieplinger, A.-M.; Jirak, P.; Davtyan, P.; Gareeva, D.; Badykova, E.; Badykov, M.; Lakman, I.; Agapitov, A.; et al. Prophylactic rivaroxaban in the early post-discharge period reduces the rates of hospitalization for atrial fibrillation and incidence of sudden cardiac death during long-term follow-up in hospitalized COVID-19 survivors. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1093396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahid, L.; Hade, E.M.; Cushman, M.; Gong, M.N.; Renard, V.; Ko, E.R.; Der, T.; Kornblith, L.Z.; Lawler, P.R.; Reynolds, H.; et al. Abstract 14153: P2Y12 Inhibitors and Quality of Life Outcomes in Critically Ill Patients Hospitalized for COVID-19: A Pre-Specified Secondary Analysis of the ACTIV4a Randomized Clinical Trial. Circulation 2023, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- linical Trial of Efficacy and Safety of Prospekta in the Treatment of Post-COVID-19 Asthenia. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39599626/ (2023).

- Ohmagari, N. , Yotsuyanagi, H., Doi, Y., Yamato, M., Imamura, T., Sakaguchi, H., Yamanaka, H., Imaoka, R., Fukushi, A., Ichihashi, G., Sanaki, T., Tsuge, Y., Uehara, T., & Mukae, H. Efficacy and safety of ensitrelvir for asymptomatic or mild COVID 19: An exploratory phase 2b/3 multicenter randomized clinical trial. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses, 18(6), e13338. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/irv.1333 (2024, June).

- Li, X. , Wu, L., Sun, S., Dong, H., & Luo, J. Association between electrolyte supplementation and cardiac injury in Long COVID 19: A retrospective cohort study. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine. https://www.s4me.info/threads/association-between-electrolyte-supplementation-and-cardiac-injury-in-long-covid-19.43008/ (2025, March 8).

- Li, X. , Wu, L., Sun, S., Dong, H., & Luo, J. Association between electrolyte supplementation and cardiac injury in Long COVID 19: A retrospective cohort study. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine. https://www.s4me.info/threads/association-between-electrolyte-supplementation-and-cardiac-injury-in-long-covid-19.43008/ (2025, March 8).

- Fornazieri, M.A.; Cunha, B.M.; Nicácio, S.P.; Anzolin, L.K.; da Silva, J.L.B.; Neto, A.F.; Neto, D.B.; Voegels, R.L.; Pinna, F.D.R. Effect of drug therapies on self-reported chemosensory outcomes after COVID-19. World J. Otorhinolaryngol. - Head Neck Surg. 2024, 10, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis A Kazal Jr, Karen L Huyck & Brendan Kelly 3. Classical Chinese Medicine (CCM) for Long COVID: Case series and treatment rationale. Encinitas. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40171061/ (2025).

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Hui, H.; Yang, D. Efficacy and safety of traditional Chinese medicine for post-COVID-19 syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonix Pharmaceuticals. Tonix Pharmaceuticals announces highly statistically significant and clinically meaningful topline results in second positive Phase 3 clinical trial of TNX-102 SL for fibromyalgia. Press release. https://ir.tonixpharma.com/news-events/press-releases/detail/1443/tonix-pharmaceuticals-announces-highly-statistically(2023, December 20).

- Lau, R. I., Su, Q., Lau, I. S. F., Ching, J. Y. L., Wong, M. C. S., & Lau, et al A synbiotic preparation (SIM01) for post acute COVID 19 syndrome in Hong Kong (RECOVERY): A randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 24(3), 256–265 (2024) https://www.thelancet. 1473. [Google Scholar]

- Leitzke, M. Is the post-COVID-19 syndrome a severe impairment of acetylcholine-orchestrated neuromodulation that responds to nicotine administration? Bioelectron. Med. 2023, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor B Grady, Bornali Bhattacharjee, Julio Silva,Jillian Jaycox, Lik Wee Lee, Valter Silva Monteiro et al Impact of COVID-19 vaccination on symptoms and immune phenotypes in vaccine-naïve individuals with Long COVID; Nature https://www.nature. 4385.

- Crawford Currie, Tor Age Myklebust, Christian Bjerknes & Bomi FramroxeAssessing the Potential of an Enzymatically Liberated Salmon Oil to Support Immune Health Recovery from Acute SARS-CoV-2 Infection via Change in the Expression of Cytokine, Chemokine and Interferon-Related Genes, International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(13) https://www.mdpi. 1422.

- Mørk, T. Å., Blomhoff, C., Fredriksen, B., Cuda, C., Kiecolt Glaser, D. A., Wilson, M. C., et al. Assessing the potential of an enzymatically liberated salmon oil for immunomodulation in adults with mild to moderate COVID 19: A pilot randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(13), 691. https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/25/13/6917 (2024, June 15).

- Nuria Suárez-Moreno, Leticia Gómez-Sánchez, Alicia Navarro-Caceres, Silvia Arroyo-Romero, Andrea Domínguez-Martín, Cristina Lugones-Sánchez et al Association of Mediterranean Diet with Cardiovascular Risk Factors and with Metabolic Syndrome in Subjects with Long COVID: BioICOPER Study Nutrients, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40004984/ (2025).

- Aroca, J.P.; Cardoso, P.M.d.F.; Favarão, J.; Zanini, M.M.; Camilotti, V.; Busato, M.C.A.; Mendonça, M.J.; Alanis, L.R.A. Auricular acupuncture in TMD — A sham-controlled, randomized, clinical trial. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pr. 2022, 48, 101569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takacs, M.; Frass, M.; Pohl-Schickinger, A.; Fibert, P.; Lechleitner, P.; Oberbaum, M.; Leisser, I.; Panhofer, P.; Chandak, K.; Weiermayer, P. Use of Homeopathy in Patients Suffering from Long COVID-19 (LONGCOVIHOM): A Case Series. OBM Integr. Complement. Med. 2024, 09, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combet, E.; Haag, L.; Richardson, J.; Haig, C.E.; Cunningham, Y.; Fraser, H.L.; Brosnahan, N.; Ibbotson, T.; Ormerod, J.; White, C.; et al. Remotely delivered weight management for people with long COVID and overweight: the randomized wait-list-controlled ReDIRECT trial. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhargav, H.; Raghavan, V.; Rao, N.P.; Gulati, K.; Binumon, K.V.; Anu, K.N.; Ravi, S.; Jasti, N.; Holla, B.; Varambally, S.; et al. Validation and efficacy of a tele-yoga intervention for improving psychological stress, mental health and sleep difficulties of stressed adults diagnosed with long COVID: a prospective, multi-center, open-label single-arm study. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1436691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheshire, A. & Cartwright, T. Perceptions, acceptability and experiences of yoga to support long COVID: A survey of people living with long COVID. BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies, 25, 123. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/393046575_Perceptions_acceptability_and_experiences_of_yoga_to_support_long-COVID_A_survey_of_people_living_with_long-COVID (2025).

- Liang, R.; Tang, L.; Li, L.; Zhao, N.; Yu, X.; Li, J.; Wang, Q.; Cun, H.; Gao, X.; Yang, W. The effect of pressing needle therapy on depression, anxiety, and sleep for patients in convalescence from COVID-19. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1481557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.; Sakurai, T.; Kanaya, T.; Iwasaki, T.; Oshima, H.; Furukawa, T.; Yoshikawa, T.; Nakahashi, S. Impact of Frailty on the Duration and Type of Speech-Language-Hearing Therapy for Patients With COVID-19. Cureus 2025, 17, e81976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Lima, A.H.; Bouhaben, J.; Delgado-Losada, M.L. Maximizing Participation in Olfactory Training in a Sample with Post-COVID-19 Olfactory Loss. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarpour, M. H., Zandi, M., Sedighi, L., & Ghanbari Ghalesar, M. Evaluating the effect of olfactory training on improving the sense of smell in patients with COVID 19 with olfactory disorders: A randomized clinical trial study. BMC Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 21(1), 215. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9510568/ (2023).

- Pendolino, A. L., Scarpa, B., & Andrews, P. J. The effectiveness of functional septorhinoplasty in improving COVID 19-related olfactory dysfunction: a prospective controlled study. Facial Plastic Surgery, 41(1), 1–9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39929248/ (2025).

- Thiago, L. I. Serrano, Marcelo A. Antonio, Lorena T. Giacomin, et al. Effect of olfactory training with essential versus odor free placebo oils in COVID 19 induced smell loss: A randomized controlled trial. The Laryngoscope, 135(5), 325–333. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40371997 (2025).

- Paranhos, A. C. M., Dias, A. R. N., Koury, G. V. H., Domingues, M. M., dos Santos, L. P. M., da Silva, L. M., Oliveira, F. L. R. V., Lima, W. T. A., Quaresma, J., Magno Falcão, L. F., & Souza, G. S. Olfactory Training in Long COVID: A Randomized Clinical Trial. SSRN. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5186634 (2025, March 26).

- Mogensen, D. G., Aanaes, K., Andersen, I. B., & Jarden, M. Effect of olfactory training in COVID 19-related olfactory dysfunction: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. The Laryngoscope, 135(5), 325–333. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40371997/ (2025).

- Blagova, O.; Yuliya, L.; Savina, P.; Kogan, E. Corticosteroids are effective in the treatment of viruspositive post-COVID myoendocarditis with high autoimmune activity. Clin. Cardiol. 2023, 46, 352–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, A.; Maskell, S.; Sharp, C.; Hamilton, F.W.; Arnold, D.T. Impact of dexamethasone on persistent symptoms of COVID-19: an observational study. Wellcome Open Res. 2023, 8, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-Q.; Wu, M.; Wang, Y.-J.; Zhang, Y.-X.; Lu, J.; Zhao, Y.-N.; Ji, B.-F.; Chen, Z.-Q.; Tang, R.-N.; Liu, B.-C. The analysis of low-dose glucocorticoid maintenance therapy in patients with primary nephrotic syndrome suffering from COVID-19. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2024, 10, 1326111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.-P.; Zhang, Y.; Niu, W.-K.; Tu, B.; Yang, N.; Fang, Y.; Shi, Y.-H.; Wang, F.-S.; Yuan, X. Clinical characteristics and effects of inhaled corticosteroid in patients with post-COVID-19 chronic cough during the Omicron variant outbreak. BMC Pulm. Med. 2024, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannakopoulos, S.; Pak, J.; Bakse, J.; A Ward, M.; Nerurkar, V.R.; Tallquist, M.D.; Verma, S. SARS-CoV-2-induced cytokine storm drives prolonged testicular injury and functional impairment in mice that are mitigated by dexamethasone. PLOS Pathog. 2025, 21, e1012804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, A.T.H. , Teopiz, C.M., West, J., & McIntyre, R.S. The impact of cognitive function on health related quality of life in persons with post COVID 19 condition and the moderating role of vortioxetine: A randomized controlled trial. medRxiv. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.03.18.24304375v1 (2024, ). 18 March.

- Nakamura, K. , Kondo, K., Oka, N., Yamakawa, K., Ie, K., Goto, T., & Fujitani, S. Donepezil for fatigue and psychological symptoms in post–COVID 19 condition: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Network Open, 8(3), e250728. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40094666/ (2025).

- Mohammad Fakhrolmobasheri, Mahnaz-Sadat Hosseini, Seyedeh-Ghazal Shahrokh, Zahra Mohammadi, Mohammad-Javad Kahlani, Seyed-Erfan Majidi et al. Coenzyme Q10 and Its Therapeutic Potencies Against COVID 19: A Molecular Review. Advanced Pharmaceutical Bulletin, 13(2), 235–244. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37342382/ (2023).

- Hansen, K.S.; Mogensen, T.H.; Agergaard, J.; Schiøttz-Christensen, B.; Østergaard, L.; Vibholm, L.K.; Leth, S. High-dose coenzyme Q10 therapy versus placebo in patients with post COVID-19 condition: a randomized, phase 2, crossover trial. Lancet Reg. Heal. - Eur. 2022, 24, 100539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barletta, M.A.; Marino, G.; Spagnolo, B.; Bianchi, F.P.; Falappone, P.C.F.; Spagnolo, L.; Gatti, P. Coenzyme Q10 + alpha lipoic acid for chronic COVID syndrome. Clin. Exp. Med. 2022, 23, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, K.S.; Mogensen, T.H.; Agergaard, J.; Schiøttz-Christensen, B.; Østergaard, L.; Vibholm, L.K.; Leth, S. High-dose coenzyme Q10 therapy versus placebo in patients with post COVID-19 condition: a randomized, phase 2, crossover trial. Lancet Reg. Heal. - Eur. 2022, 24, 100539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews JS, Boonyaratanakornkit JB, Krusinska E, Allen S, Posada JA. Assessment of the Impact of RNase in Patients With Severe Fatigue Related to PASC: A Randomized Phase 2 Trial (RSLV-132). Clinincal Infectious Diseases.79(3):635-642. https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/79/3/635/7668392? 2025.

- Tejaswini Kulkarni, Joel Santiaguel, Raminder Aul, Mark Harnett, Julie Krop, Michael C. Chen et al, double-blind RCT; antifibrotic deupirfenidone in PASC with respiratory involvement. ERJ Open Research (2025) https://publications.ersnet.org/content/erjor/11/4/01142-2024. 2025.

- Wiegand, C.; Hipler, U.-C.; Elsner, P.; Tittelbach, J. Keratinocyte and Fibroblast Wound Healing In Vitro Is Repressed by Non-Optimal Conditions but the Reparative Potential Can Be Improved by Water-Filtered Infrared A. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.-Q.; Song, L.; Wang, Z.-R.; Zhang, Z.-Y.; Shi, M.; He, J.; Mo, Q.; Zheng, N.; Yao, W.-Q.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Long-term outcomes of mesenchymal stem cell therapy in severe COVID-19 patients: 3-year follow-up of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, F.; Wang, W.; Ke, J.; Huang, T.; Jiang, B.; Qiu, Q.; Huang, J.; Zhan, S.; Zhang, W.; Wu, H.; et al. Fuzheng Huayu tablets for treating pulmonary fibrosis in post-COVID-19 patients: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1508276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GeNeuro, SA. Top-line Phase 2 results of GNC 501 (temelimab) in post COVID neuropsychiatric syndromes show no clinically meaningful benefit. GeNeuro Press Release. https://geneuro.ch/en/geneuro-news/geneuro-announces-the-results-of-the-gnc-501-in-post-covid-19-syndrome/ (2024, ). 28 June.

- Hou, C.; Xing, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, T.; Qi, J.; Jia, X.; Zeng, X.; Bai, J.; Lu, W.; Deng, Y.; et al. A Subgroup Reanalysis of the Efficacy of Bufei Huoxue Capsules in Patients With “Long-Covid-19”. Pulm. Circ. 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonda, K.; Hai, T.; Suzuki, K.; Ozaki, A.; Shibusa, T.; Takenoshita, S.; Maejima, Y.; Shimomura, K. Effect of Ficus pumila L. on Improving Insulin Secretory Capacity and Resistance in Elderly Patients Aged 80 Years Old or Older Who Develop Diabetes After COVID-19 Infection. Nutrients 2025, 17, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efficacy of Apportal® nutritional supplement in reducing post COVID fatigue: A study of 232 patients. Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34857243/ (2021).

- Atieh, O.; Daher, J.; Durieux, J.C.; Abboud, M.; Labbato, D.; Baissary, J.; Koberssy, Z.; Ailstock, K.; Cummings, M.; Funderburg, N.T.; et al. Vitamins K2 and D3 Improve Long COVID, Fungal Translocation, and Inflammation: Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2025, 17, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopp, J. , Kuenzi, L., Rueegg, S., Braun, J., Rasi, M., Anagnostopoulos, A., Puhan, M. A., Fehr, J. S., & Radtke, T. Effects of Pycnogenol® in post COVID 19 condition (PYCNOVID): A single center, placebo controlled, quadruple blind, randomized trial. medRxiv. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.06.12.25329489v1 (2025, June 12).

- Noce, A.; Marrone, G.; Di Lauro, M.; Vita, C.; Montalto, G.; Giorgino, G.; Chiaramonte, C.; D’agostini, C.; Bernardini, S.; Pieri, M. Potential Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Fatigue Effects of an Oral Food Supplement in Long COVID Patients. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, R.I.; Su, Q.; Ching, J.Y.; Lui, R.N.; Chan, T.T.; Wong, M.T.; Lau, L.H.; Wing, Y.K.; Chan, R.N.; Kwok, H.Y.; et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Sleep Disturbance in Post-acute COVID-19 Syndrome. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 22, 2487–2496.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, J.; Ali, F.; Lopez, M.; Shah, S.A.; Schmidt, C.W.; Quesada, O.; Henry, T.D.; Verduzco-Gutierrez, M. Enhanced External Counterpulsation Improves Dyspnea, Fatigue, and Functional Capacity in Patients with Long COVID. COVID 2024, 4, 1379–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovechkin, A.; Moshonkina, T.; Shamantseva, N.; Lyakhovetskii, V.; Suthar, A.; Tharu, N.; Ng, A.; Gerasimenko, Y. Spinal Neuromodulation for Respiratory Rehabilitation in Patients with Post-Acute COVID-19 Syndrome. Life 2024, 14, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victoria, L.W.; Oberlin, L.E.; Ilieva, I.P.; Jaywant, A.; Kanellopoulos, D.; Mercaldi, C.; Stamatis, C.A.; Farlow, D.N.; Kollins, S.H.; Tisor, O.; et al. A digital intervention for cognitive deficits following COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 2024, 50, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Borba, V.; Peris-Baquero, Ó.; Prieto-Rollán, I.; Osma, J.; del Corral-Beamonte, E. Preliminary feasibility and clinical utility of the Unified Protocol for the transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders in people with long COVID-19 condition: A single case pilot study. PLOS ONE 2025, 20, e0329595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurt, R.T.; Ganesh, R.; Schroeder, D.R.; Hanson, J.L.; Fokken, S.C.; Overgaard, J.D.; Bauer, B.A.; Thilagar, B.P.; Aakre, C.A.; Pruthi, S.; et al. Using a Wearable Brain Activity Sensing Device in the Treatment of Long COVID Symptoms in an Open-Label Clinical Trial. J. Prim. Care Community Heal. 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, J.; Hires, C.; Keenan, L.; Dunne, E. Aromatherapy blend of thyme, orange, clove bud, and frankincense boosts energy levels in post-COVID-19 female patients: A randomized, double-blinded, placebo controlled clinical trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2022, 67, 102823–102823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavda, V.P.; Balar, P.C.; Jogi, G.; Marwadi, S.; Patel, A.; Doshi, A.; Ajabiya, J.; Vora, L. The potential role of essential oils in boosting immunity and easing COVID-19 symptoms. Clin. Tradit. Med. Pharmacol. 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S. A., Varanasi, S., Sathyamoorthy, M., Teal, A., Verduzco-Gutierrez, M., & Cabrera, J. Enhanced external counterpulsation offers potential treatment option for Long COVID patients. American College of Cardiology Press Release. https://www.acc.org/About-ACC/Press-Releases/2022/02/14/14/25/Enhanced-External-Counterpulsation-Offers-Potential-Treatment-Option-for-Long-COVID-Patients (2022, February 14).

- Stein, E.; Heindrich, C.; Wittke, K.; Kedor, C.; Kim, L.; Freitag, H.; Krüger, A.; Tölle, M.; Scheibenbogen, C. Observational Study of Repeat Immunoadsorption (RIA) in Post-COVID ME/CFS Patients with Elevated ß2-Adrenergic Receptor Autoantibodies—An Interim Report. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badran, B.W.; Huffman, S.M.; Dancy, M.; Austelle, C.W.; Bikson, M.; Kautz, S.A.; George, M.S. A pilot randomized controlled trial of supervised, at-home, self-administered transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) to manage long COVID symptoms. Bioelectron. Med. 2022, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natelson, B.H.; Blate, M.; Soto, T. Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation in the Treatment of Long Covid- Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Arch. Clin. Biomed. Res. 2023, 07, 239–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.S.; Simonian, N.; Wang, J.; Rosario, E.R. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation improves Long COVID symptoms in a female cohort: a pilot study. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1393371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestito, L.; Ponzano, M.; Mori, L.; Trompetto, C.; Bandini, F.; Canta, R.; De Giovanni, A.; Strano, S.; Pagani, A. A randomized controlled trial of anodal transcranial direct current stimulation (A-tDCS) and olfactory training in persistent COVID-19 anosmia. Brain Stimul. 2025, 18, 1106–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulbaran-Rojas, A.; Bara, R.O.; Lee, M.; Bargas-Ochoa, M.; Phan, T.; Pacheco, M.; Camargo, A.F.; Kazmi, S.M.; Rouzi, M.D.; Modi, D.; et al. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for fibromyalgia-like syndrome in patients with Long-COVID: a pilot randomized clinical trial. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabel, B. A., Zhou, W., Huber, F., Schmidt, F., Sabel, K., Gonschorek, A., & Bilc, M. Non invasive brain microcurrent stimulation therapy of Long COVID 19 reduces vascular dysregulation and improves visual and cognitive impairment: Two case studies. Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience, 39(6), 393–408. (2021, December). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih. 3492. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zhu, T.; Li, X.; Lai, X.; Chen, M. Tragus Nerve Stimulation Attenuates Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome in Post COVID-19 Infection. Clin. Cardiol. 2025, 48, e70110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosmo, C.; Zandvakili, A.; Petrosino, N.J.; Berlow, Y.A.; Philip, N.S. Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for Treatment-Resistant Depression: Recent Critical Advances in Patient Care. Curr. Treat. Options Psychiatry 2021, 8, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, A.C.R.; Silva, J.C.; Garcês, C.P.; Sisconeto, T.M.; Nascimento, J.L.R.; Amaral, A.L.; Cunha, T.M.; Mariano, I.M.; Puga, G.M. Online and Face-to-Face Mat Pilates Training for Long COVID-19 Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial on Health Outcomes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2024, 21, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira PC, de Lima CJ, Villaverde AB, Fernandes AB, Zângaro RA, et al. Photobiomodulation in the treatment of pulmonary fibrosis after COVID-19: a prospective study. Research Square (preprint). https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-5483003/v1(2024, ). 25 November.

- Campos, M.C.V.; Schuler, S.S.V.; Lacerda, A.J.; Mazzoni, A.C.; Silva, T.; Rosa, F.C.S.; Martins, M.D.; Fernandes, K.P.S.; Fonseca, E.S.; Mesquita-Ferrari, R.A.; et al. Evaluation of vascular photobiomodulation for orofacial pain and tension type headache following COVID 19 in a pragmatic randomized clinical trial. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi B., Zulbaran A., Lee M., Bara R. O. et al. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for fibromyalgia like syndrome in patients with Long COVID: a pilot randomized clinical trial. Nature Scientific Reports. (2024). https://www.nature. 4159.

- Chauhan, G.; Upadhyay, A.; Khanduja, S.; Emerick, T. Stellate Ganglion Block for Anosmia and Dysgeusia Due to Long COVID. Cureus 2022, 14, e27779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.D.; Duricka, D.L. Stellate ganglion block reduces symptoms of Long COVID: A case series. J. Neuroimmunol. 2021, 362, 577784–577784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisa Pearson, Alfred Maina, Taylor Compratt, Sherri Harden, Abbey Aaroe, Whitney Copas & Leah Thompson R. Stellate Ganglion Block Relieves Long COVID-19 Symptoms in 86% of Patients: A Retrospective Cohort Study Cureus (2023). https://www.cureus.com/articles/184194-stellate-ganglion-block-relieves-long-covid-19-symptoms-in-86-of-patients-a-retrospective-cohort-study?fbclid=IwAR3Wo1cdeheoLLMCrM8ht2SvoxElieU44VIEmJy-LFA3shdbOcmKqmA22nw#!

- Duricka, D.; Liu, L. Reduction of long COVID symptoms after stellate ganglion block: A retrospective chart review study. Auton. Neurosci. 2024, 254, 103195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R. , Kumar, A., Mehra, S., Sharma, V., & Verma, P. Evaluation of usefulness of ropinirole in the treatment of post COVID 19 restless legs syndrome: A quasi experimental study. Journal of Pharmaceutical Negative Results, 13, 2603–2606. (2022, June). https://www.pnrjournal.com/index. 4336. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, M.F.; O’bYrne, T.J.; Calva, J.J.; Mallory, M.J.; Bublitz, S.E.; Do, A.; Neto, C.D.P.; Choby, G.W.; O’bRien, E.K.; Bauer, B.A.; et al. The Feasibility of Investigating Acupuncture in Patients With COVID-19 Related Olfactory Dysfunction. Glob. Adv. Integr. Med. Heal. 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, M.; Reinke, M.; Löwe, B.; Engelmann, P. Development of an expectation management intervention for patients with Long COVID: A focus group study with affected patients. PLOS ONE 2025, 20, e0317905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, K.E.J.; Burton, A.; Lewis, A.; Buttery, S.C.; Williams, P.J.; I Polkey, M.; Fancourt, D.; Hopkinson, N. Participant experience of Scottish Ballet’s online dance based long COVID support programme: A mixed methods study. ERS Congress 2024 abstracts. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; p. OA2766.

- Yamaguchi K, Saito Y, Tanaka H, et al. Aripiprazole for treating post-COVID-19 hypersomnolence in adolescents: A case series. Sleep, 48(Suppl 1): A365. (2025, May). https://academic.oup. 8135.

- Krishnamurthy, V.; Wilckens, K.; Garbioglu, P.; Vaidya, S.; Swanger, S.; Whitehead, A.; Patel, S. 1410 Effect of CPAP on Cognitive Fog in Post COVID Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Sleep 2025, 48, A606–A606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, T. W.-H., Zhang, H., Wong, F. K.-C., Sridhar, S., Lee, T. M.-C., Leung, G. K.-K. et al. Short course oral vitamin A and aerosolised diffuser olfactory training for the treatment of smell loss in long COVID: A pilot study. Brain Sciences, 13(7), 1014. (2023). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. 1037. [Google Scholar]

- Pendolino, A. L., Scarpa, B., & Andrews, P. J. The effectiveness of functional septorhinoplasty in improving COVID 19 related olfactory dysfunction: Prospective controlled study. Facial Plastic Surgery. (2025, February 24). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih. 3992. [Google Scholar]

- Cano, N.; Casas, O.; Ariza, M.; Gelonch, O.; Plana, Y.; Porras-Garcia, B.; Garolera, M. Effects of a Multimodal Immersive Virtual Reality Intervention on Heart Rate Variability in Adults with Post-COVID-19 Syndrome. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melián-Ortíz, A.; Zurdo-Sayalero, E.; Perpiñá-Martínez, S.; Delgado-Lacosta, A.; Jiménez-Antona, C.; Fernández-Carnero, J.; Laguarta-Val, S. Superficial Neuromodulation in Dysautonomia in Women with Post-COVID-19 Condition: A Pilot Study. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claudia Loren and Roland Frankenberger Oronasal drainage (OND): A novel treatment approach for Long COVID symptoms. Viruses (2025) https://www.mdpi. 1999.

- Oesch Régeni, B. , Germann, N., Hafer, G., Schmid, D., & Arn, N. Effect on quality of life of therapeutic plasmapheresis in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome patients with elevated β adrenergic and M3 muscarinic receptor antibodies – a pilot study. Preprints.org. (2025)https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202504. 0228. [Google Scholar]

- Kamel, T.; Toppen, W.; Salahmand, Y. Successful Treatment of Post-coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Autoimmune Encephalitis With Plasmapheresis After a Failed Trial of Steroids. Cureus 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, G.L.; Endo, T.; Sakoda, S. Circadian re-set repairs long-COVID in a prodromal Parkinson’s parallel: a case series. J. Med Case Rep. 2024, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbouAssaly JR, Masuko T, Sasai-Masuko H, Strale FJ Jr (2025). Neurofeedback for COVID-19 brain fog: a secondary analysis. Cureus, 17(2): e79222. (2025) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih. 4011.

- España-Cueto, S.; Loste, C.; Lladós, G.; López, C.; Santos, J.R.; Dulsat, G.; García, A.; Carmezim, J.; Carabia, J.; Ancochea, Á.; et al. Plasma exchange therapy for the post COVID-19 condition: a phase II, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaylis, N.B.; Ritter, A.; A Kelly, S.; Pourhassan, N.Z.; Tiwary, M.; Sacha, J.B.; Hansen, S.G.; Recknor, C.; O Yang, O. Reduced Cell Surface Levels of C-C Chemokine Receptor 5 and Immunosuppression in Long Coronavirus Disease 2019 Syndrome. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, 1232–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akanchise, T.; Angelov, B.; Angelova, A. Nanomedicine-mediated recovery of antioxidant glutathione peroxidase activity after oxidative-stress cellular damage: Insights for neurological long COVID. J. Med Virol. 2024, 96, e29680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentina Cenacchi, Giovanni Furlanis, Alina Menichelli, Alberta Lunardelli, Valentina Pesavento, Paolo Manganotti Co-ultraPEALut in Subjective Cognitive Impairment Following SARS-CoV-2 Infection: An Exploratory Retrospective Study. Brain Sciences (2024) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih. 3853.

- Sasso, E.M.; Muraki, K.; Eaton-Fitch, N.; Smith, P.; Jeremijenko, A.; Griffin, P.; Marshall-Gradisnik, S. Investigation into the restoration of TRPM3 ion channel activity in post-COVID-19 condition: a potential pharmacotherapeutic target. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1264702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasso, E.M.; Eaton-Fitch, N.; Smith, P.; Muraki, K.; Marshall-Gradisnik, S. Low-Dose naltrexone restored TRPM3 ion channel function in natural killer cells from long COVID patients. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2025, 12, 1582967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hector Bonilla, Lu Tian, Vincent C. Marconi, Robert Shafer, Grace A. McComsey, Mitchel Miglis et al Low dose naltrexone for post acute sequelae of SARS CoV 2 infection: A retrospective clinical cohort study. medRxiv (2023) https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.06.08. 2329.

- Glynne, P.; Tahmasebi, N.; Gant, V.; Gupta, R. Long COVID following Mild SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Characteristic T Cell Alterations and Response to Antihistamines. J. Investig. Med. 2021, 70, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul Glynne, Natasha Tahmasebi, Vanya Gant, Rajeev Gupta Long COVID following mild SARS-CoV-2 infection: characteristic T cell alterations and response to antihistamines Journal of Investigated Medicine (2022) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih. 3461.

- Harandi, A.A.; Pakdaman, H.; Medghalchi, A.; Kimia, N.; Kazemian, A.; Siavoshi, F.; Barough, S.S.; Esfandani, A.; Hosseini, M.H.; Sobhanian, S.A. A randomized open-label clinical trial on the effect of Amantadine on post Covid 19 fatigue. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, S.R.; Black, B.K.; Biaggioni, I.; Paranjape, S.Y.; Ramirez, M.; Dupont, W.D.; Robertson, D. Propranolol Decreases Tachycardia and Improves Symptoms in the Postural Tachycardia Syndrome. Circulation 2009, 120, 725–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttuso, T. , Zhu, J., & Wilding, G. E. (2024). Lithium aspartate for long COVID fatigue and cognitive dysfunction: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Network Open, 7(10), e2436874 (2024) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih. 3935. [Google Scholar]

- Landers, D.B.; Yousafzai, O.K.; Klinkhammer, B.; Tancredi, J.; Turi, Z.; Jamal, S.; Glotzer, T.V.; Hollenberg, S.M.; Rockett, G.; Cofini, N.; et al. BETA-BLOCKER THERAPY IMPROVES CARDIOVASCULAR SYMPTOMS IN PATIENTS WITH REFRACTORY POST-ACUTE SEQUELAE OF COVID-19 (PASC OR LONG COVID). Circ. 2024, 83, 2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strayer, D.R.; Young, D.; Mitchell, W.M. Effect of disease duration in a randomized Phase III trial of rintatolimod, an immune modulator for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0240403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadev, A.; Hentati, F.; Miller, B.; Bao, J.; Perrin, A.; Kallogjeri, D.; Piccirillo, J.F. Efficacy of Gabapentin For Post–COVID-19 Olfactory Dysfunction. Arch. Otolaryngol. Neck Surg. 2023, 149, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendreau, R. M. , Bateman, L., Duncan, G., Vernon, S., Sullivan, K., & Gendreau, R., et al. Low-dose IMC 2 (valacyclovir 750 mg + celecoxib 200 mg BID) improves fatigue and sleep disruption in long COVID: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled investigator-initiated study. BioSpace. (2024) https://www.biospace.

- Finnigan, L.E.; Cassar, M.P.; Koziel, M.J.; Pradines, J.; Lamlum, H.; Azer, K.; Kirby, D.; Montgomery, H.; Neubauer, S.; Valkovič, L.; et al. Efficacy and tolerability of an endogenous metabolic modulator (AXA1125) in fatigue-predominant long COVID: a single-centre, double-blind, randomised controlled phase 2a pilot study. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 59, 101946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, D. Thomas Jefferson University explores platelet rich plasma to restore smell after COVID 19. ABC News. (2022) https://6abc. 1163. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, C. H., Jang, S. S., Lin, H. C. F., et al. Use of platelet rich plasma for COVID 19–related olfactory loss: A randomized controlled trial. International Forum of Allergy and Rhinology, 13(6), 989–997 (2022) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih. 3650. [Google Scholar]

- Bazdyrev, E.; Panova, M.; Brachs, M.; Smolyarchuk, E.; Tsygankova, D.; Gofman, L.; Abdyusheva, Y.; Novikov, F. Efficacy and safety of Treamid in the rehabilitation of patients after COVID-19 pneumonia: a phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]