Submitted:

04 July 2025

Posted:

04 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Socioeconomic Environment

2.2. Quantification of Long COVID Syndrome Prevalence

2.3. Survey: Persistent Symptoms

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

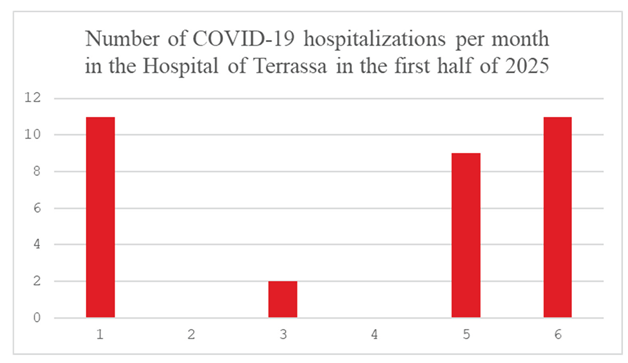

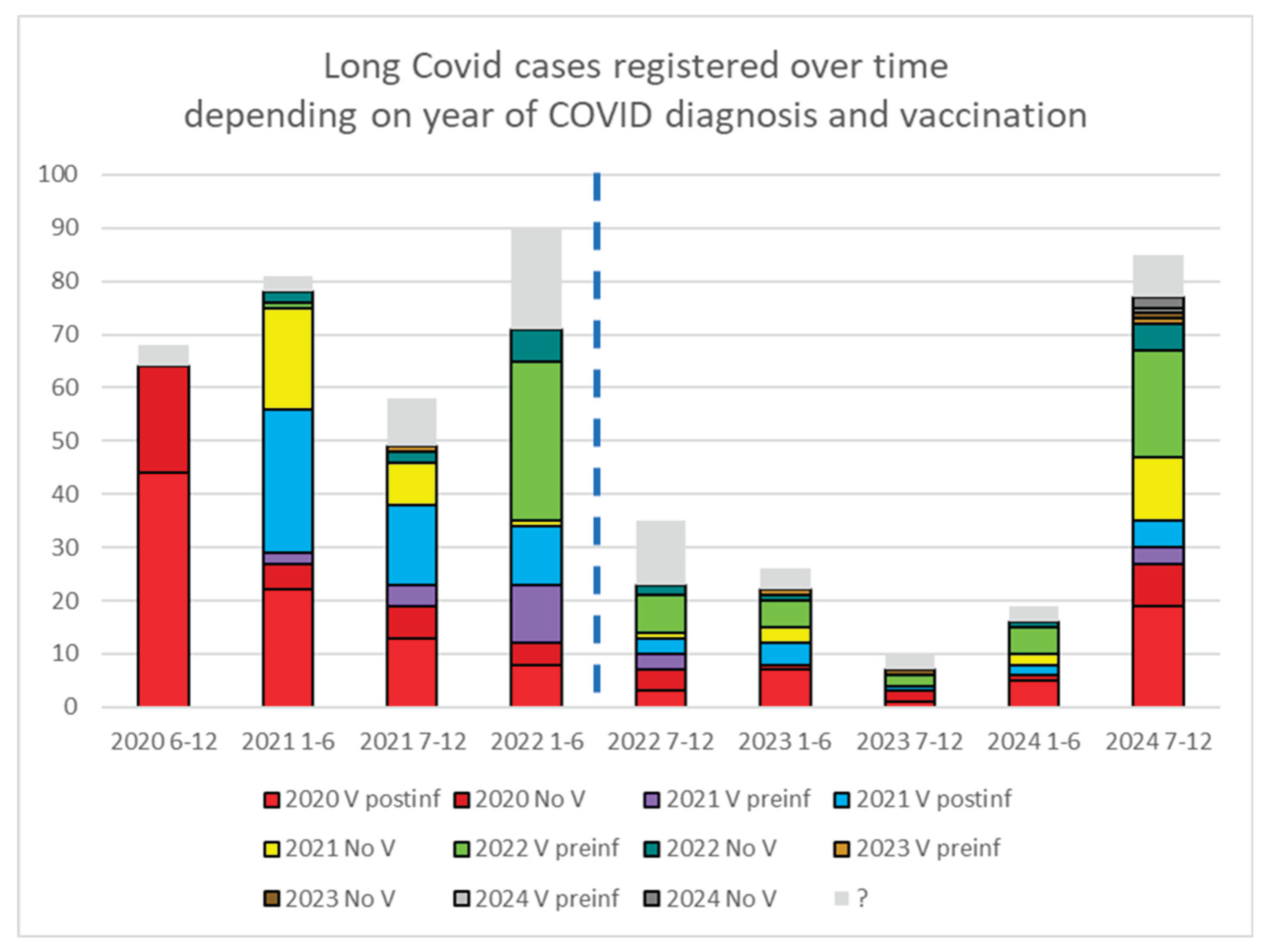

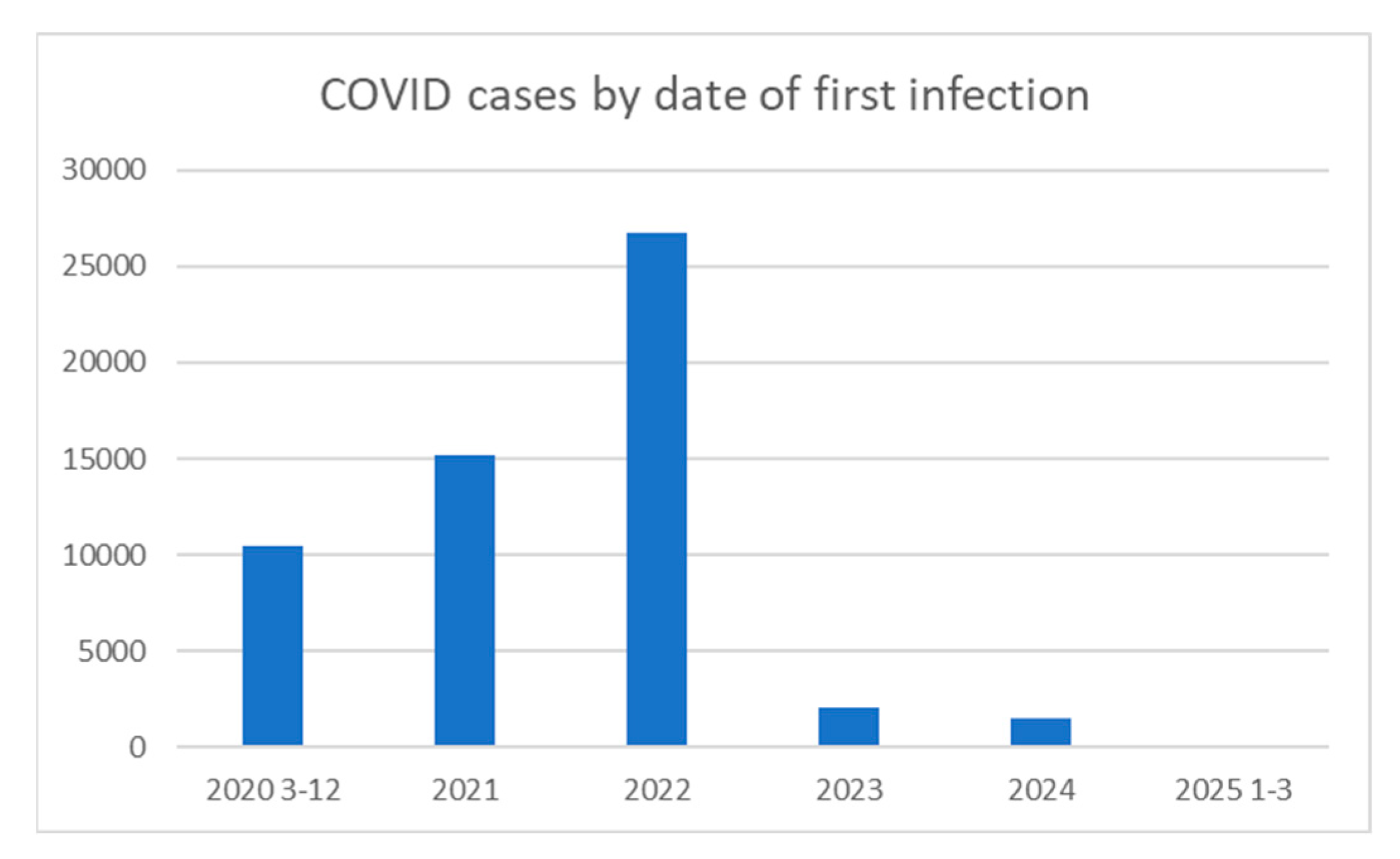

3.1. Prevalence of Long Covid and Number of Infections

3.2. Survey: Reported Persistent and Transient Symptoms

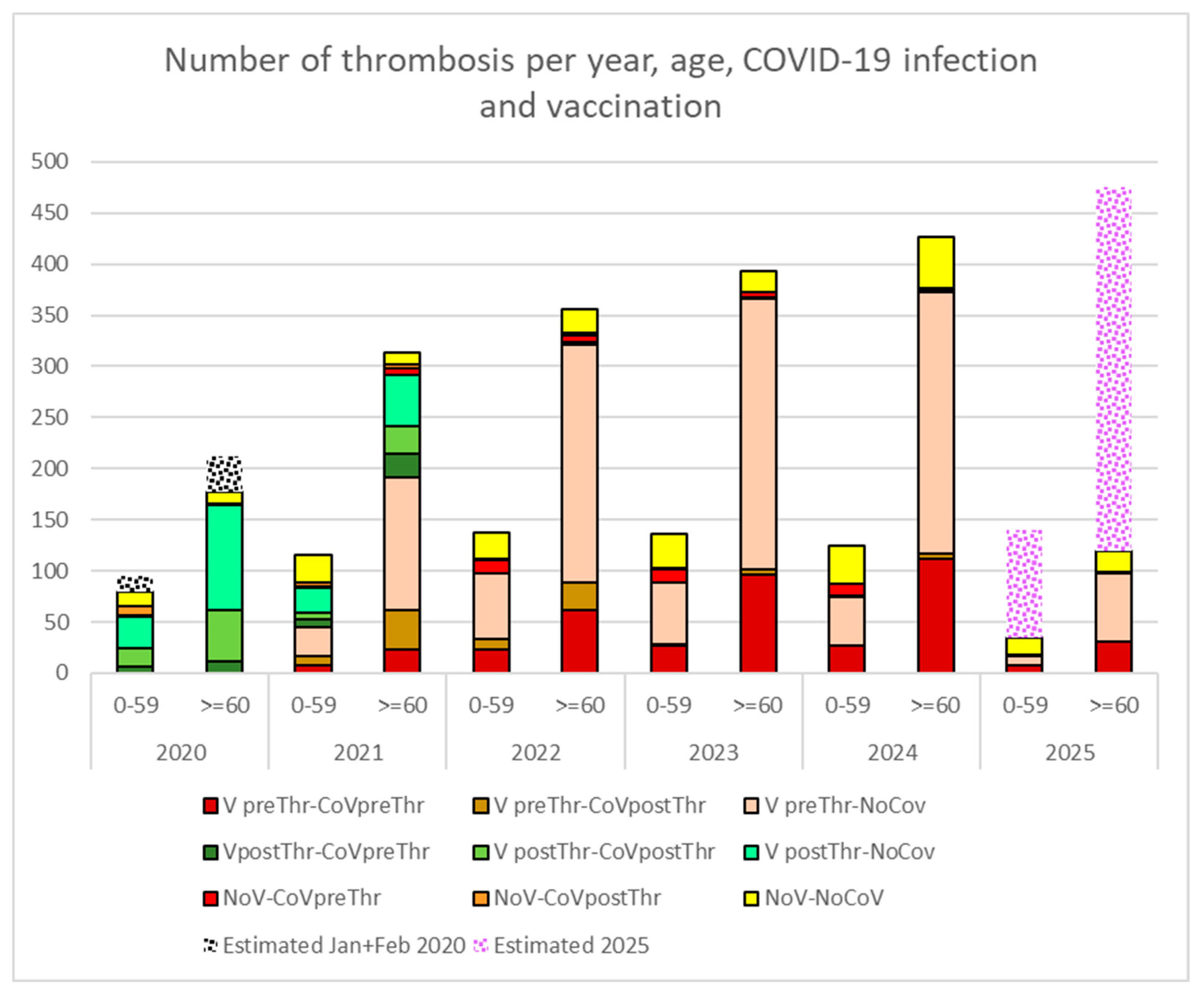

3.3. Thrombotic Events

4. Discussion

4.1. Increased Prevalence with Multiple Infections

4.2. Increase in Thrombotic Events

4.3. Persistent and Transient Symptoms-Functional Affectation

4.4. Long COVID and Future

4.5. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LC | Long Covid |

| No V | Non vaccinated |

| Preinf | Previously to the COVID-19 infection |

| Postinf | Posterior to the COVID-19 infection |

| PreThr | Previously to the thrombosis |

| PostThr | Posterior to the thrombosis |

| CoV | COVID-19 infection |

| CST | Consorci Sanitari de Terrassa |

Appendix A

- 5.

- How was the diagnosis made?

- ∙

- I had a rapid test

- ∙

- I had a PCR test

- ∙

- I had a blood test

- ∙

- No test was done. Diagnosis based only on symptoms

- ∙

- I did the test myself

- 6.

- >6. Have you been diagnosed with "Long COVID" or had symptoms attributed to COVID that lasted more than 2 or 3 months?

- ∙

- Yes. I still have symptoms

- ∙

- Yes, but I am now recovered

- ∙

- No

- ∙

- I don’t know

- 7.

- Overall rating of your current health status (on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 is the worst possible health status and 10 is excellent health)

- ∙

- 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

- 8.

- Overall rating of the worsening of your health compared to before COVID (on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 is no change and 10 is maximum worsening)

- ∙

- 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

- 9.

- Do you have functional limitations in your daily life (personal hygiene, household tasks, work activity, relationships with friends and/or close family)?

- ∙

- Yes

- ∙

- No

- 10.

- If you answered yes, please indicate which of the following apply:

- ∙

- Personal hygiene

- ∙

- Household tasks

- ∙

- Work activity

- ∙

- Relationships with friends and/or close family

- 11.

- Are your symptoms mainly physical or psychological?

- ∙

- Physical symptoms

- Psychological symptoms

- Both physical and psychological symptoms

- Have you had to take sick leave for more than a month due to persistent COVID-related symptoms?

- Yes

- No

- If you answered yes to the previous question, how long were you on sick leave?

- Between 1 and 3 months

- 3 to 6 months

- 6 to 12 months

- More than a year

- Do you consent to being contacted by your health center (CAP) in case there is any treatment or intervention that could benefit you?

- Yes

- No

Appendix B

Appendix C

Appendix C.1

| nV | p | No V | p | ||||||||||

| n infection | n V preinf | 1 | 2 | 3 | >=3 | 1 vs >=3 doses | vs >=3 doses | ||||||

| ? | COV | 5811 | 21171 | 12447 | 21556 | 75685 | |||||||

| LC | 7 | 13 | 10 | 15 | 21 | ||||||||

| 1 | COV | 1342 | 7272 | 3778 | 5992 | 21608 | |||||||

| LC | 2 (0.1%) | 22 (0.3%) | 11 (0.3%) | 13 (0.2%) | 92 (0.42%) | ||||||||

| 2 | COV | 601 | 934 | 578 | 835 | 1833 | |||||||

| LC | 14 (2.3%) | 12 (1.3%) | 5 (0.9%) | 12 (1.4%) | 18 (0.97%) | ||||||||

| >=3 | COV | 70 | 106 | 87 | 94 | 136 | |||||||

| LC | 2 (2.8%) | 2 (1.9%) | 2 (2.2%) | 2 (2.1%) | 10 (6.8%) | ||||||||

| OR vs 1 dose | 2,03 | 1,95 | 1,45 | 0.61 | 1,96 | 0.02* | |||||||

| OR vs 1 dose | 0,56 | 0,38 | 0,62 | 0.22 | 0,69 | 0.30 | |||||||

| OR vs 1 dose | 0,67 | 0,81 | 0,75 | 0.77 | 3,29 | 0.047* | |||||||

| n infection | nV postinf | 1 | 2 | 3 | >=3 | ||||||||

| 1 | COV | 3854 | 2523 | 1314 | 2193 | ||||||||

| LC | 55 (1.4%) | 42 (1.16%) | 25 (1.9%) | 49(2.2%) | |||||||||

| 2 | COV | 113 | 72 | 47 | 103 | ||||||||

| LC | 4 (3.4%) | 4 (5.3%) | 5(4.6%) | ||||||||||

| >=3 | COV | 7 | 7 | 5 | 23 | ||||||||

| LC | 4 (36.4%) | 1(16.7%) | 1 (4.2%) | ||||||||||

| OR vs 1 dose | 1,1638 | 1,327 | 1,5533 | 0.02* | |||||||||

| OR vs 1 dose | 1,5395 | 0 | 1,3542 | 0.64 | |||||||||

| OR vs 1 dose | 0 | 0,4583 | 0,1146 | 0.01* | |||||||||

References

- Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, Madhavan MV, McGroder C, Stevens JS, Cook JR, Nordvig AS, Shalev D, Sehrawat TS, Ahluwalia N, Bikdeli B, Dietz D, Der-Nigoghossian C, Liyanage-Don N, Rosner GF, Bernstein EJ, Mohan S, Beckley AA, Seres DS, Choueiri TK, Uriel N, Ausiello JC, Accili D, Freedberg DE, Baldwin M, Schwartz A, Brodie D, Garcia CK, Elkind MSV, Connors JM, Bilezikian JP, Landry DW, Wan EY. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med. 2021 Apr;27(4):601-615.

- Davis HE, McCorkell L, Vogel JM, Topol EJ. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023 Mar;21(3):133-146. Epub 2023 Jan 13. Erratum in: Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023 Jun;21(6):408. [CrossRef]

- O'Mahoney LL, Routen A, Gillies C, Jenkins SA, Almaqhawi A, Ayoubkhani D, Banerjee A, Brightling C, Calvert M, Cassambai S, Ekezie W, Funnell MP, Welford A, Peace A, Evans RA, Jeffers S, Kingsnorth AP, Pareek M, Seidu S, Wilkinson TJ, Willis A, Shafran R, Stephenson T, Sterne J, Ward H, Ward T, Khunti K. The risk of Long Covid symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled studies. Nat Commun. 2025 May 7;16(1):4249. [CrossRef]

- Ceban, F.; et al. Fatigue and cognitive impairment in post-COVID-19 syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 101, 93–135 (2022).

- Ariza, M.; Cano, N.; Segura, B.; Adan, A.; Bargalló, N.; Caldú, X.; Campabadal, A.; Jurado, M.A.; Mataró, M.; Pueyo, R.; et al. Neuropsychological impairment in post-COVID condition individuals with and without cognitive complaents. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 1029842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doskas T, Vavougios GD, Kormas C, Kokkotis C, Tsiptsios D, Spiliopoulos KC, Tsiakiri A, Christidi F, Aravidou T, Dekavallas L, Kazis D, Dardiotis E, Vadikolias K. Neurocognitive Impairment After COVID-19: Mechanisms, Phenotypes, and Links to Alzheimer's Disease. Brain Sci. 2025 May 25;15(6):564.

- Zayet S, Zahra H, Royer PY, Tipirdamaz C, Mercier J, Gendrin V, Lepiller Q, Marty-Quinternet S, Osman M, Belfeki N, Toko L, Garnier P, Pierron A, Plantin J, Messin L, Villemain M, Bouiller K, Klopfenstein T. Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: Nine Months after SARS-CoV-2 Infection in a Cohort of 354 Patients: Data from the First Wave of COVID-19 in Nord Franche-Comté Hospital, France. Microorganisms. 2021 Aug 12;9(8):1719. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massey D, Saydah S, Adamson B, Lincoln A, Aukerman DF, Berke EM, Sikka R, Krumholz HM. Prevalence of covid-19 and long covid in collegiate student athletes from spring 2020 to fall 2021: a retrospective survey. BMC Infect Dis. 2023 Dec 13;23(1):876.

- Rajpal S, Tong MS, Borchers J, Zareba KM, Obarski TP, Simonetti OP, Daniels CJ. Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Findings in Competitive Athletes Recovering From COVID-19 Infection. JAMA Cardiol. 2021 Jan 1;6(1):116-118. Erratum in: JAMA Cardiol. 2021 Jan 1;6(1):123.

- Koutsiaris AG, Karakousis K. Long COVID Mechanisms, Microvascular Effects, and Evaluation Based on Incidence. Life (Basel). 2025 May 30;15(6):887.

- Eltayeb A, Adilović M, Golzardi M, Hromić-Jahjefendić A, Rubio-Casillas A, Uversky VN, Redwan EM. Intrinsic factors behind long COVID: exploring the role of nucleocapsid protein in thrombosis. PeerJ. 2025 May 20;13:e19429.

- Polack, F.P.; Thomas, S.J.; Kitchin, N.; Absalon, J.; Gurtman, A.; Lockhart, S.; Perez, J.L.; Pérez Marc, G.; Moreira, E.D. ; Zerbini,C. ; et al. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2603–2615. [Google Scholar]

- Baden, L.R.; El Sahly, H.M.; Essink, B.; Kotloff, K.; Frey, S.; Novak, R.; Diemert, D.; Spector, S.A.; Rouphael, N.; Creech, C.B.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramasamy, M.N.; Minassian, A.M.; Ewer, K.J.; Flaxman, A.L.; Folegatti, P.M.; Owens, D.R.; Voysey, M.; Aley, P.K.; Angus, B.; Babbage, G.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine administered in a prime-boost regimen in young and old adults (COV002): A single-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet 2021, 396, 1979–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephenson, K.E.; Le Gars, M.; Sadoff, J.; de Groot, A.M.; Heerwegh, D.; Truyers, C.; Atyeo, C.; Loos, C.; Chandrashekar, A.; McMahan, K. Immunogenicity of the Ad26. COV2.S Vaccine for COVID-19. JAMA 2021, 325, 1535–1544. [Google Scholar]

- Faksova, K.; Walsh, D.; Jiang, Y.; Griffin, J.; Phillips, A.; Gentile, A.; Kwong, J.C.; Macartney, K.; Naus, M.; Grange, Z.; et al. COVID-19 vaccines and adverse events of special interest: A multinational Global Vaccine Data Network (GVDN) cohort study of 99 million vaccinated individuals. Vaccine 2024, 42, 2200–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yardibi F, Demirci S. Global trends and hot spots in cerebral venous sinus thrombosis research over the past 50 years: a bibliometric analysis. Neurol Res. 2025 Jan;47(1):23-34.

- Nitz JN, Ruprecht KK, Henjum LJ, Matta AY, Shiferaw BT, Weber ZL, Jones JM, May R, Baio CJ, Fiala KJ, Abd-Elsayed AA. Cardiovascular Sequelae of the COVID-19 Vaccines. Cureus. 2025;17(4):e82041.

- Satyam SM, El-Tanani M, Bairy LK, Rehman A, Srivastava A, Kenneth JM, Prem SM. Unraveling Cardiovascular Risks and Benefits of COVID-19 Vaccines: A Systematic Review. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2025 Feb;25(2):306-323.

- Taher MK, Salzman T, Banal A, Morissette K, Domingo FR, Cheung AM, Cooper CL, Boland L, Zuckermann AM, Mullah MA, Laprise C, Colonna R, Hashi A, Rahman P, Collins E, Corrin T, Waddell LA, Pagaduan JE, Ahmad R, Jaramillo Garcia AP. Global prevalence of post-COVID-19 condition: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective evidence. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2025 Mar;45(3):112-138. Erratum in: Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2025 Jun;45(6):307-308. [CrossRef]

- Sk Abd Razak R, Ismail A, Abdul Aziz AF, Suddin LS, Azzeri A, Sha'ari NI, Post-COVID syndrome prevalence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2024 Jul 4;24(1):1785. [CrossRef]

- Obeidat M, Abu Zahra A, Alsattari F. Prevalence and characteristics of long COVID-19 in Jordan: A cross sectional survey. PLoS One. 2024 Jan 26;19(1):e0295969. PMCID: PMC10817197. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puigdellívol-Sánchez, A.; Juanes-González, M.; Calderón-Valdiviezo, A.; Valls-Foix, R.; González-Salvador, M.; Lozano-Paz, C.; Vidal-Alaball, J. COVID-19 in Relation to Chronic Antihistamine Prescription. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puigdellívol-Sánchez A, Juanes-González M, Calderón-Valdiviezo AI, Losa-Puig H, González-Salvador M, León-Pérez M, Pueyo-Antón L, Franco-Romero M, Lozano-Paz C, Cortés-Borra A, Valls-Foix R. COVID-19 Pandemic Waves and 2024-2025 Winter Season in Relation to Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors, Angiotensin Receptor Blockers and Amantadine. Healthcare (Basel). 2025 May 27;13(11):1270.

- Puigdellívol-Sánchez A, Juanes-González M, Calderón-Valdiviezo A, Valls-Foix R, González-Salvador M, Lozano-Paz C, Vidal-Alaball J. COVID-19 in Relation to Polypharmacy and Immunization (2020-2024). Viruses. 2024 Sep 27;16(10):1533.

- Dean, A.G.; Sullivan, K.M.; Soe, M.M. OpenEpi: Open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health, Versión. Available online: https://www.openepi.com/Menu/OE_Menu.htm (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Chen YC, Chiu CH, Chen CJ. Neurological and psychiatric aspects of long COVID among vaccinated healthcare workers: An assessment of prevalence and reporting biases. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2025 Jun 23:S1684-1182(25)00125-2.

- Cameli M, Pastore MC, Mandoli GE, D'Ascenzi F, Focardi M, Biagioni G, Cameli P, Patti G, Franchi F, Mondillo S, Valente S. COVID-19 and Acute Coronary Syndromes: Current Data and Future Implications. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021 Jan 28;7:593496.

- Nair AS, Tauro L, Joshi HB, Makhal A, Sobczak T, Goret J, Dewitte A, Kaveri S, Chakrapani H, Matsuda MM, Joshi MB. Influence of homocysteine on regulating immunothrombosis: mechanisms and therapeutic potential in management of infections. Inflamm Res. 2025;74(1):86.

- Carrera Morodoa M, Pérez Orcerob A, Ruiz Moreno J, Altemir Vidal A, Larrañaga Cabrerab A, Fernández San Martín MI, Prevalencia de la COVID persistente: seguimiento al año de una cohorte poblacional ambulatoria, Rev Clin Med Fam. 2023; 16( 2 ): 94-97. [CrossRef]

- Pisaturo M, Russo A, Grimaldi P, Monari C, Imbriani S, Gjeloshi K, Ricozzi C, Astorri R, Curatolo C, Palladino R, Caruso F, Ambrisi F, Onorato L, Coppola N. Prevalence, Evolution and Prognostic Factors of PASC in a Cohort of Patients Discharged from a COVID Unit. Biomedicines. 2025 Jun 9;13(6):1414. PMCID: PMC12191248. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomasa-Irriguible TM, Monfà R, Miranda-Jiménez C, Morros R, Robert N, Bordejé-Laguna L, Vidal S, Torán-Monserrat P, Barriocanal AM. Preventive Intake of a Multiple Micronutrient Supplement during Mild, Acute SARS-CoV-2 Infection to Reduce the Post-Acute COVID-19 Condition: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Randomized Clinical Trial. Nutrients. 2024 May 26;16(11):1631.

- Gordon, D.E.; Jang, G.M.; Bouhaddou, M.; Xu, J.; Obernier, K.; White, K.M.; O’Meara, M.J.; Rezelj, V.V.; Guo, J.Z.; Swaney, D.L. A SARS-CoV-2 Protein Interaction Map Reveals Targets for Drug-Repurposing. Nature 2020, 583, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morán Blanco, J.I.; Alvarenga Bonilla, J.A.; Fremont-Smith, P.; Villar Gómez de Las Heras, K. Antihistamines as an early treatment for COVID-19. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harandi, A.A.; Pakdaman, H.; Medghalchi, A.; Kimia, N.; Kazemian, A.; Siavoshi, F.; Barough, S.S.; Esfandani, A.

- M. H.; Sobhanian, S.A. A randomized open-label clinical trial on the effect of Amantadine on post COVID 19 fatigue. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1343.

- Rejdak, K.; Fiedor, P.; Bonek, R.; Łukasiak, J.; Chełstowski, W.; Kiciak, S.; Dąbrowski, P.; Gala-Błądzińska, A.; Dec, M.; Papuć,E.; et al. Amantadine in unvaccinated patients with early, mild to moderate COVID-19: A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Eur. J. Neurol. 2024.

- Bramante CT, Beckman KB, Mehta T, Karger AB, Odde DJ, Tignanelli CJ, Buse JB, Johnson DM, Watson RHB, Daniel JJ, Liebovitz DM, Nicklas JM, Cohen K, Puskarich MA, Belani HK, Siegel LK, Klatt NR, Anderson B, Hartman KM, Rao V, Hagen AA, Patel B, Fenno SL, Avula N, Reddy NV, Erickson SM, Fricton RD, Lee S, Griffiths G, Pullen MF, Thompson JL, Sherwood NE, Murray TA, Rose MR, Boulware DR, Huling JD; COVID-OUT Study Team. Favorable Antiviral Effect of Metformin on SARS-CoV-2 Viral Load in a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial of COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2024 Aug 16;79(2):354-363.

- Bramante CT, Buse JB, Liebovitz DM, Nicklas JM, Puskarich MA, Cohen K, Belani HK, Anderson BJ, Huling JD, Tignanelli CJ, Thompson JL, Pullen M, Wirtz EL, Siegel LK, Proper JL, Odde DJ, Klatt NR, Sherwood NE, Lindberg SM, Karger AB, Beckman KB, Erickson SM, Fenno SL, Hartman KM, Rose MR, Mehta T, Patel B, Griffiths G, Bhat NS, Murray TA, Boulware DR; COVID-OUT Study Team. Outpatient treatment of COVID-19 and incidence of post-COVID-19 condition over 10 months (COVID-OUT): a multicentre, randomised, quadruple-blind, parallel-group, phase 3 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023 Oct;23(10):1119-1129.. Erratum in: Lancet Infect Dis. 2023 Oct;23(10):e400. [CrossRef]

- Assessment of the Impact of RNase in Patients With Severe Fatigue Related to Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Randomized Phase 2 Trial of RSLV-132. Clin Infect Dis. 2024 Sep 26;79(3):635-642.

- Yotsuyanagi H, Ohmagari N, Doi Y, Yamato M, Fukushi A, Imamura T, Sakaguchi H, Sonoyama T, Sanaki T, Ichihashi G, Tsuge Y, Uehara T, Mukae H. Prevention of post COVID-19 condition by early treatment with ensitrelvir in the phase 3 SCORPIO-SR trial. Antiviral Res. 2024 Sep;229:105958.

- Geng LN, Bonilla H, Hedlin H, Jacobson KB, Tian L, Jagannathan P, Yang PC, Subramanian AK, Liang JW, Shen S, Deng Y, Shaw BJ, Botzheim B, Desai M, Pathak D, Jazayeri Y, Thai D, O'Donnell A, Mohaptra S, Leang Z, Reynolds GZM, Brooks EF, Bhatt AS, Shafer RW, Miglis MG, Quach T, Tiwari A, Banerjee A, Lopez RN, De Jesus M, Charnas LR, Utz PJ, Singh U. Nirmatrelvir-Ritonavir and Symptoms in Adults With Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection: The STOP-PASC Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2024 Sep 1;184(9):1024-1034.. Erratum in: JAMA Intern Med. 2024 Sep 1;184(9):1137.

- Yasacı Z, Mustafaoglu R, Ozgur O, Kuveloglu B, Esen Y, Ozmen O, Yalcinkaya EY. Virtual recovery: efficacy of telerehabilitation on dyspnea, pain, and functional capacity in post-COVID-19 syndrome. Ir J Med Sci. 2025.

- Carpallo-Porcar B, Calvo S, Pérez-Palomares S, Blázquez-Pérez L, Brandín-de la Cruz N, Jiménez-Sánchez C. Perceptions and Experiences of a Multimodal Rehabilitation Program for People With Post-Acute COVID-19: A Qualitative Study. Health Expect. e: 2025 Jun;28(3), 2025.

- Daynes E, Evans RA, Greening NJ, Bishop NC, Yates T, Lozano-Rojas D, Ntotsis K, Richardson M, Baldwin MM, Hamrouni M, Hume E, McAuley H, Mills G, Megaritis D, Roberts M, Bolton CE, Chalmers JD, Chalder T, Docherty AB, Elneima O, Harrison EM, Harris VC, Ho LP, Horsley A, Houchen-Wolloff L, Leavy OC, Marks M, Poinasamy K, Quint JK, Raman B, Saunders RM, Shikotra A, Singapuri A, Sereno M, Terry S, Wain LV, Man WD, Echevarria C, Vogiatzis I, Brightling C, Singh SJ; PHOSP-COVID Study Collaborative Group. Post-Hospitalisation COVID-19 Rehabilitation (PHOSP-R): a randomised controlled trial of exercise-based rehabilitation. Eur Respir J. 2: 2025 ;65(5), 22 May 2025.

- Seers K, Nichols VP, Bruce J, Ennis S, Heine P, Patel S, Sandhu HK, Underwood M, McGregor G; our REGAIN collaborators.; REGAIN collaborators.. Qualitative evaluation of the Rehabilitation Exercise and psycholoGical support After COVID-19 InfectioN (REGAIN) randomised controlled trial (RCT): 'you are not alone'. BMJ Open. e: 2025 Jan 29;15(1), 2025.

- Weix NM, Shake HM, Duran Saavedra AF, Clingan HE, Hernandez VC, Johnson GM, Hansen AD, Collins DM, Pryor LE, Kitchens R, Armstead A, Hilton C. Cognitive Interventions and Rehabilitation to Address Long-COVID Symptoms: A Systematic Review. OTJR (Thorofare N J). 2025 May 19:15394492251328310.

- Generalitat de Catalunya. Sistema d’Informació per a la Vigilància d’Infeccions a Catalunya. Available online: https://sivic.salut. gencat.cat/ (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Dinnes, J.; Deeks, J.J.; Berhane, S.; Taylor, M.; Adriano, A.; Davenport, C.; Dittrich, S.; Emperador, D.; Takwoingi, Y. ; Cunningham,J. ; et al. Cochrane COVID-19 Diagnostic Test Accuracy Group 2. Rapid point-of-care antigen and molecular-based tests for diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 3, CD013705. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/360580/WHO-2019-nCoVSurveillanceGuidance-2022.2-eng.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Ford ND, Baca S, Dalton AF, Koumans EH, Raykin J, Patel PR, Saydah S. Use and Characteristics of Clinical Coding for Post-COVID Conditions in a Retrospective US Cohort. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2025 Mar 5. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrix N, Parikh RV, Taskier M, Walter G, Rochlin I, Saydah S, Koumans EH, Rincón-Guevara O, Rehkopf DH, Phillips RL. Heterogeneity of diagnosis and documentation of post-COVID conditions in primary care: A machine learning analysis. PLoS One. 2025 May 16;20(5):e0324017. PMCID: PMC12083802. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Carballa, A.; Bello, X.; Pardo-Seco, J.; Pérez del Molino, M.L.; Martiñón-Torres, F.; Salas, A. Phylogeography of SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in Spain: A story of multiple introductions, micro-geographic stratification, founder effects, and super-spreaders. Zool. Res. 2020, 41, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Longcovid | Total | |||||

| Post survey | Pre survey | Long covid | No long COVID | Population | ||

| Women/age | 80 | 242 | 322 (3.3‰) | 96676 | 96998 | |

| 0-29 | 2 | 19 | 21 (0.7‰) | 30907 | 30928 | |

| 30-59 | 63 | 171 | 234 (5.6‰) | 41530 | 41764 | |

| ≥60 | 15 | 52 | 67 (2.7‰) | 24239 | 24306 | |

| Men/age | 19 | 134 | 153 (1.6‰) | 95500 | 95653 | |

| 0-29 | 1 | 16 | 17 (0.5‰) | 32850 | 32867 | |

| 30-59 | 11 | 90 | 101(2.3‰) | 43054 | 43155 | |

| ≥60 | 7 | 28 | 35 (1.7‰) | 19596 | 19631 | |

| Total general | 99 | 376 | 475 (2.4‰) | 192176 | 192651 | |

| n infection | V | CoV | LC | (%) | OR vs 1inf | p | vs V preinf | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ? | V | 60985 | 45 | 0.07% | ||||

| ? | No V | 75664 | 21 | 0.03% | ||||

| 1 | V preinf | 18386 | 46 | 0.25% | ||||

| 1 | V postinf | 9889 | 168 | 1.67% | ||||

| 1 | No V | 21608 | 94 | 0.43% | ||||

| 2 | V preinf | 2948 | 43 | 1.44% | 5.8 | <0.0001 | ||

| 2 | V postinf | 335 | 14 | 4.01% | 2.4 | 0.001 | ||

| 2 | No V | 1833 | 18 | 0.97% | 2.2 | 0.001 | ||

| >=3 | V preinf | 355 | 10 | 2.74% | 11.0 | <0.0001 | ||

| >=3 | V postinf | 37 | 8 | 17.78% | 10.6 | <0.0001 | 6.49 | <0.0001 |

| >=3 | No V | 136 | 8 | 5.56% | 12.8 | <0.0001 | 2.03 | 0.06 |

| Responders with Long covid diagnosis: |

Yes 368 |

Yes, and I'm still symptomatic | Yes, but I already feel good |

Unsure 281 | No 1222 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical complains | ||||||

| Anosmia or dysgeusia | 23.4% | 86 | 20 | 18.9% | 40 | 39 |

| Shortness of breath | 27.2% | 100 | 28 | 21.9% | 74 | 66 |

| Headache | 22.3% | 82 | 23 | 21.9% | 75 | 79 |

| Joint pain | 32.9% | 121 | 58 | 32.4% | 135 | 160 |

| Persistent Fatigue | 41.6% | 153 | 68 | 30.8% | 159 | 209 |

| Psychological complains | ||||||

| Memory complains | 30.7% | 113 | 35 | 23.6% | 91 | 104 |

| Lack of concentration | 31.0% | 114 | 37 | 24.5% | 86 | 131 |

| Depression | 16.6% | 61 | 20 | 24.7% | 52 | 69 |

| Anxiety | 31.3% | 115 | 48 | 29.4% | 101 | 147 |

| Sleep complains | 26.6% | 98 | 34 | 25.8% | 98 | 151 |

| Functional impairment | ||||||

| Home task | 20.4% | 75 | 19 | 20.2% | 55 | 52 |

| With friends or relatives | 17.4% | 64 | 14 | 17.9% | 42 | 62 |

| Impaired personal hygiene | 4.1% | 15 | 5 | 25.0% | 11 | 16 |

| Work interference | 25.8% | 95 | 35 | 26.9% | 69 | 79 |

| COVID-19 related sick leave | 37.5% | 138 | 75 | 35.2% | 127 | 541 |

| No V | V | OR | V | |||||||||

| NoV vs V | 1 | 2 | 3 | >=3 | ||||||||

| 1 COVID-19 infection | 50 | 1008 | 75 | 394 | 364 | 175 | ||||||

| No | 38 | 717 | 49 | 266 | 269 | 133 | ||||||

| Unsure | 6 | 143 | 6 | 58 | 59 | 20 | ||||||

| Long CoV still symptomatic | 5 | 10.0% | 89 | 8.8% | 10 | 13.3% | 47 | 11.9% | 20 | 5.5% | 12 | 6.9% |

| Transient Long Cov | 1 | 59 | OR 1.13 | 10 | 23 | 16 | 10 | |||||

|

2 COVID 19 infections |

21 | 574 | 57 | 231 | 217 | 69 | ||||||

| No | 12 | 343 | 28 | 132 | 141 | 42 | ||||||

| Unsure | 2 | 95 | 9 | 42 | 32 | 12 | ||||||

| Long CoV still symptomatic | 4 | 19.0% | 84 | 14.6% | 15 | 26.3% | 36 | 15.6% | 26 | 12.0% | 7 | 10.1% |

| Transient Long Cov | 3 | 52 | OR 1.30 | 5 | 21 | 18 | 8 | |||||

|

3 COVID 19 infections |

6 | 173 | 29 | 75 | 55 | 14 | ||||||

| No | 2 | 78 | 11 | 37 | 23 | 7 | ||||||

| Unsure | 30 | 6 | 13 | 9 | 2 | |||||||

| Long CoV still symptomatic | 2 | 33.3% | 43 | 24.9% | 11 | 37.9% | 15 | 20.0% | 14 | 25.5% | 3 | 21.4% |

| Transient Long Cov | 2 | 22 | OR 1.34 | 1 | 10 | 9 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).