Submitted:

02 September 2025

Posted:

03 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Construction of the SGVI

2.2. Subnational Indicators

2.3. Addressing Missing Data

2.4. Standardization Around National Values

2.5. Constructing the SGVI

3. Results

3.1. Contribution of Indicators

3.2. SGVI Level and Changes

3.3. Decomposing Variation in GVI

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Birkmann, J. et al. (2013). Framing vulnerability, risk and societal responses: the MOVE framework. Natural Hazards 67, 193-211. [CrossRef]

- Parsons, M. et al. (2016). Top-down assessment of disaster resilience: A conceptual framework using coping and adaptive capacities. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 19, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- IPCC, Field, C.B. et al. (eds.). (2014). Summary for Policy Makers, in: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability (Cambridge University Press, 1–34).

- IPCC, Pörtner, H.-O. et al. (eds.) (2022). Summary for Policymakers, in: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge University Press, 3–33).

- Simpson, N. P., Mach, K. J., Constable, A., Hess, J., Hogarth, R., Howden, M., Lawrence, J., Lempert, R. J., Muccione, V., Mackey, B., et al. A framework for complex climate change risk assessment. One Earth 4(4), 489–501. (2021). [CrossRef]

- Ara Begum, R., Lempert, R., Ali, E. et al. in Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds. Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M. et al.) Point of Departure and Key Concepts, 121–196 (Cambridge University Press) (2023). [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, B., Van Aalst, M., Zaiton Ibrahim, Z., et al. in Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Chang (eds. Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M. et al.) Key Risks across Sectors and Regions, 2411–2538 (Cambridge University Press) (2023). [CrossRef]

- Ruane, A. C., Vautard, R., Ranasinghe, R., et al. The Climatic Impact-Driver Framework for Assessment of Risk-Relevant Climate Information. Earth’s Future 10(11), e2022EF002803. (2022). [CrossRef]

- Muttarak, R. & Lutz, W. (2014). Is education a key to reducing vulnerability to natural disasters and hence unavoidable climate change?. Ecology and Society 19. [CrossRef]

- Kocur-Bera, K.; Czyza, S., 2023, Socio-Economic Vulnerability to Climate Change in Rural Areas in the Context of Green Energy Development—A Study of the Great Masurian Lakes Mesoregion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2689. [CrossRef]

- Hallegatte, S., Fay, M. & Barbier, E. B. (2018). Poverty and climate change: Introduction. Environment and Development Economics 23, 217-233. [CrossRef]

- Ebi, K. et al. (2021). Extreme weather and climate change: population health and health system implications. Annual Review of Public Health 42, 293-315. [CrossRef]

- Atwii, F. et al. (2022). World Risk Report 2022 (Bündnis Entwicklung Hilft. https://www.worldriskreport.org/).

- Cutter, S., Boruff, B. & Lynn Shirley, W. (2003). Social vulnerability to environmental hazards. Social Science Quarterly 84, 42–61. [CrossRef]

- Ayanlade, A., Smucker, Th., Nyasimi, M., et al. Complex climate change risk and emerging directions for vulnerability research in Africa. Climate Risk Management 40, 100497. (2023). [CrossRef]

- Birkmann, J. et al. (2022). Understanding human vulnerability to climate change: A global perspective on index validation for adaptation planning. Science of the Total Environment 803. [CrossRef]

- UNDP. HDR technical note https://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2021-22_HDR/hdr2021-22_technical_notes.pdf (2022).

- Miola, A. (2015). Climate resilient development: theoretical framework, selection criteria and fit for purpose indicators. Institute for Environment and Sustainability, European Commission – Joint Research Centre, JRC94771. [CrossRef]

- Marin-Ferrer, M., Vernaccini, L. & Poljansek, K. (2017). INFORM Index for Risk Management. Concept and Methodology (https://drmkc.jrc.ec.europa.eu/inform-index).

- Welle, T. & Birkmann, J. (2015). The world risk index—an approach to assess risk and vulnerability on a global scale. J Extreme Events 02. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C., Noble, I., Hellmann, J., Coffee, J., Murillo, M. & Chawla, N. (2015). University of Notre Dame Global Adaptation Index: Country Index Technical Report (https://gain.nd.edu/assets/254377/nd_gain_technical_document_2015.pdf).

- Smits, J. & Huisman, J. (2024). The GDL Vulnerability Index (GVI). Social Indicators Research, 174, 721-741. [CrossRef]

- Feldmeyer, D., Wilden, D., Jamshed, A. & Birkmann, J. (2020). Regional climate resilience index: A novel multimethod comparative approach for indicator development, empirical validation and implementation. Ecological Indicators 119, 106861. [CrossRef]

- Garschagen, M., Doshi, D., Reith, J. & Hagenlocher, M. (2021). Global patterns of disaster and climate risk-an analysis of the consistency of leading index-based assessments and their results. Climatic Change 169. [CrossRef]

- Becker, W., Saisana, M., Paruolo, P. & Vandecasteele, I. (2017). Weights and importance in composite indicators: Closing the gap. Ecological Indicators 80, 12-22. [CrossRef]

- Füssel, H.-M. (2006). Vulnerability: a general applicable conceptual framework for climate change research. Global Environmental Change 17, 155-167. [CrossRef]

- Grimm, M., Harttgen, K., Klasen, S., Misselhorn, M. A Human Development Index by Income Groups, World Development, Volume 36, Issue 12, 2008, Pages 2527-2546, ISSN 0305-750X. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305750X0800106X). [CrossRef]

- Grimm, M., Harttgen, K., Klasen, S. et al. Inequality in Human Development: An Empirical Assessment of 32 Countries. Soc Indic Res 97, 191–211 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Graetz, N., Friedman, J., Osgood-Zimmerman, A. et al. Mapping local variation in educational attainment across Africa. Nature 555, 48–53 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Milanovic, B. (2016). Global inequality: A new approach for the age of globalization. Harvard University Press.

- Permanyer, I. & J. Smits. (2020). Inequality in human development across the globe. Population and Development Review. 46(3), 583-601. Online version available here. [CrossRef]

- Harttgen, Kenneth; Klasen, Stephan (2011) : A Human Development Index at the Household Level, Discussion Papers, No. 75, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Courant Research Centre - Poverty, Equity and Growth (CRC-PEG), Göttingen.

- Harttgen, K., & Klasen, S. (2012). Do Fragile Countries Experience Worse MDG Progress? The Journal of Development Studies, 49(1), 134–159. [CrossRef]

- Crombach, L & J. Smits. (2024a). Understanding the Urban-Rural Fertility Divide in sub-Saharan Africa: The Critical Role of Social Isolation. Population, Space and Place, 30, e2801. [CrossRef]

- Huisman, J. & J. Smits (2015). Keeping children in school: Household and district-level determinants of school dropout in 322 districts of 30 developing countries. Sage Open, October-December, 1-15. Paper available here. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Dan & Jiajun Xian (2018). The correlations among the World Development Indicators. IEEE-Xplore. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?arnumber=8632595.

- Kraemer, G., M. Reichstein, G. Camps-Valls, J. Smits & M. Mahecha (2020). The Low Dimensionality of Development. Social Indicators Research 150, 999–1020.

- Ghislandi, S., Sanderson, W. C., & Scherbov, S. (2019). A simple measure of human development: The human life indicator. Population and Development Review, 45(1), 219. [CrossRef]

- Huisman, J, Rosanne Martyr, René Rott & J. Smits (forthcoming). Projections of climate change vulnerability along the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways, 2020-2100. Nature Scientific Data. [CrossRef]

- WDI (2024). The World Bank, World Development Indicators https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

- Human Development Index Database (HDID) of the UNDP (2024).

- UNDP, 2021.

- Crombach, L & J. Smits (2021). The demographic window of opportunity and economic growth at sub-national level in 91 developing countries. Social Indicators Research, 161, pages 171–189. Online version available here. [CrossRef]

- WGI (2024). The World Bank, Worldwide Governance Indicators https://databank.worldbank.org/source/worldwide-governance-indicators.

- Vyas, S., & Kumaranayake, L. (2006). Constructing Socio-Economic Status indices: How to use principal components analysis. Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Global Data Lab, www.globaldatalab.org.

- Huisman, J. & J. Smits. (2009). Effects of household and district-level factors on primary school enrollment in 30 developing countries. World Development, 37(1), 179-193. [CrossRef]

- Smits, J. (2016). GDL Area Database: Sub-national development indicators for research and policy-making. GDL Working paper 16-101.

- Smits, J & I. Permanyer (2019). The Subnational Human Development Database. (Nature) Scientific Data, 6, 190038. Online version available here.

- Crombach, L & J. Smits (2024b). The Subnational Corruption Database: Grand and petty corruption in 1,473 regions of 178 countries, 1995-2022. (Nature) Scientific Data, 11, 686. [CrossRef]

- Demographic and Health Surveys.

- UNICEF Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS. https://mics.unicef.org).

- IPUMS International (https://international.ipums.org).

- Afrobarometers (www.afrobarometer.org).

- Lapop Surveys (www.vanderbilt.edu/lapop/).

- Asian Barometers (www.asianbarometer.org/).

- Smits, J. & R. Steendijk (2015). The International Wealth Index (IWI). Social Indicators Research, 122(1), 65-85. [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, D. & Kraay, A. C. The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and 2024 Update (English) (Policy Research working paper; Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group). http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/099005210162424110 (2024).

- Gbohoui, W., Lam, W. R. & Lledo, V. D. (2019). The Great Divide: Regional Inequality and Fiscal Policy. IMF Working Paper WP/19/88.

- Kummu, M., Taka, M. & Guillaume, J. H. (2018). A. Gridded global datasets for Gross Domestic Product and Human Development Index over 1990-2015. Scientific Data 5 (180004), 1–15 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Snijders, Tom A.B., and Bosker, Roel J. Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling, second edition. London etc.: Sage Publishers, 2012.

- Jenkins, Stephen, and Philippe Van Kerm. 2011. “The Measurement of Economic Inequality.” In The Oxford Handbook of Economic Inequality, edited by Brian Nolan, Wiemer Salverda, and Timothy Smeeding. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Cowell, F.A. Measuring Inequality, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011.

| Indicators | Coefficients |

|---|---|

| GDP per capita (GDPc) | -0.00010686 |

| Poverty headcount at $3.65 | 0.09081646 |

| Years of schooling | -0.71308829 |

| Gender Development Index | -25.59264906 |

| Life expectancy at birth | -0.31492412 |

| Access to clean water | -0.1565931 |

| Access to electricity | -0.08874772 |

| Phone subscriptions | -0.07288862 |

| World Governance Index | -2.32477119 |

| Dependency Ratio | 0.13230595 |

| Urbanization | -0.08628689 |

| Constant | -22.63157686 |

| ALL | SSA | LAC | MENAS | CSAP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 54.88 | 53.71 | 54.84 | 55.03 | 54.98 |

| GDPc | -1.11 | -1.65 | -0.85 | -0.87 | -0.79 |

| Poverty365 | 3.28 | 4.08 | 2.76 | 2.38 | 2.88 |

| Education | -2.10 | -1.99 | -2.03 | -2.02 | -2.07 |

| GDI | -1.54 | -1.20 | -2.07 | -2.15 | -2.05 |

| Life expectancy | -2.21 | -2.39 | -2.10 | -2.29 | -2.18 |

| Clean water | -2.70 | -2.50 | -2.83 | -2.91 | -2.85 |

| Electricity | -2.48 | -2.25 | -2.91 | -3.32 | -2.99 |

| Phones | -1.62 | -1.26 | -2.20 | -2.16 | -2.16 |

| Governance | -1.66 | -1.71 | -1.58 | -1.58 | -1.58 |

| Dependency ratio | 2.97 | 3.31 | 2.52 | 2.46 | 2.53 |

| Urbanization | -2.51 | -2.35 | -2.59 | -2.59 | -2.55 |

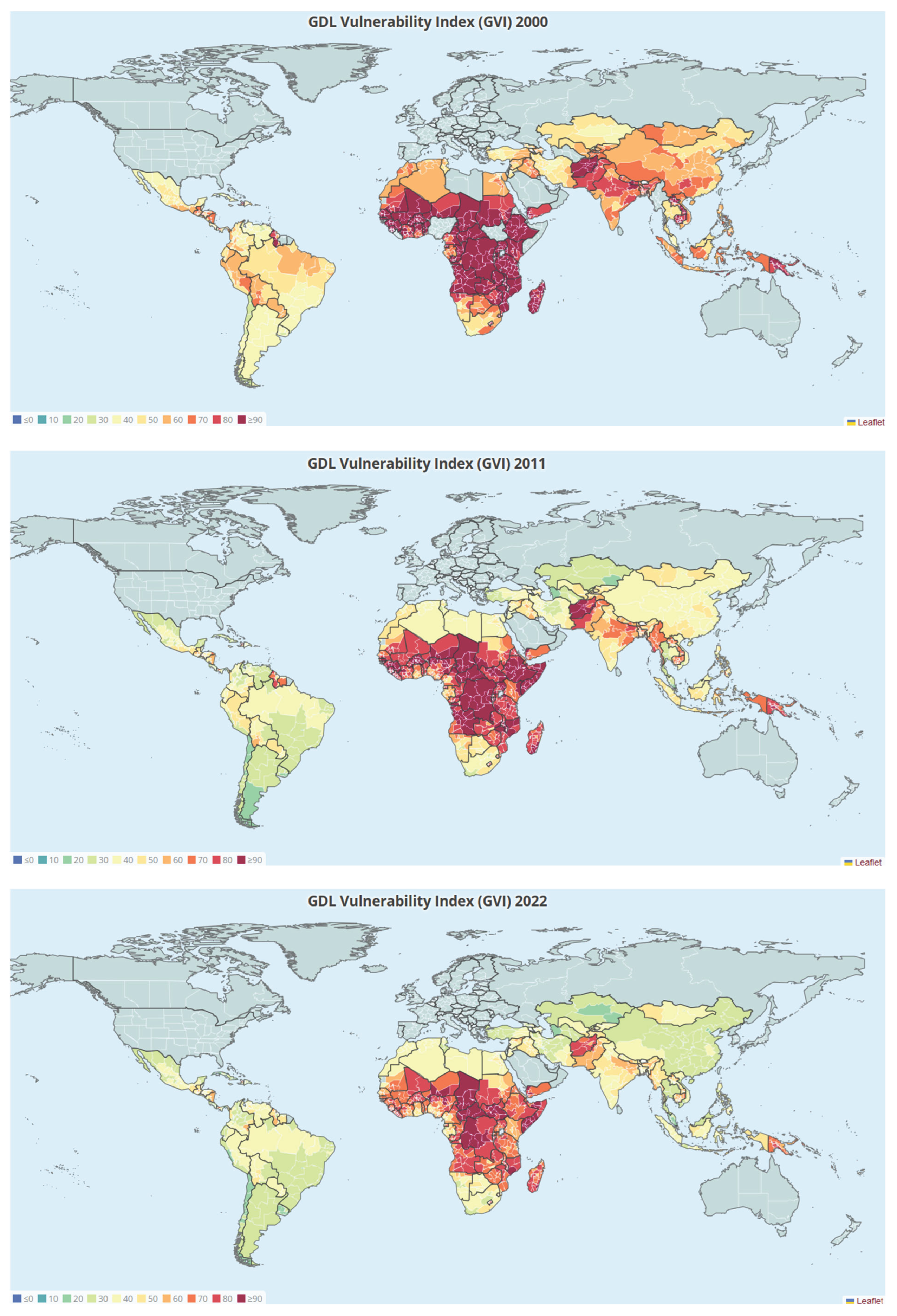

| All | LAC | SSA | MENAS | CSAP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean SGVI | |||||

| 2000 | 71.7 | 54.4 | 89.2 | 60.9 | 71.8 |

| 2011 | 61.3 | 43.0 | 79.7 | 47.0 | 59.3 |

| 2022 | 54.7 | 40.2 | 71.5 | 44.5 | 49.4 |

| Percentual change in mean SGVI | |||||

| 2000-2011 | 14.6 | 21.0 | 10.6 | 22.8 | 17.4 |

| 2012-2022 | 9.3 | 5.3 | 9.2 | 4.2 | 14.7 |

| 2000-2022 | 23.7 | 26.1 | 19.9 | 27.0 | 31.2 |

| GINI | Increase in GINI when including subnational level | |||||

| Region | 2000 | 2011 | 2022 | 2000 | 2011 | 2022 |

| All | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 17.8 | 18.9 | 19.9 |

| SSA | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 89.4 | 82.1 | 72.8 |

| LAC | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 31.1 | 40.4 | 52.5 |

| MENAS | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 40.4 | 37.2 | 24.2 |

| CSAP | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 40.3 | 38.8 | 30.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).