Submitted:

03 September 2025

Posted:

03 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Extraction

2.3. Treatment Regimens

2.4. Evaluation of Outcomes

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

3.2. Characterization of Potential “Driver” Mutation Profile

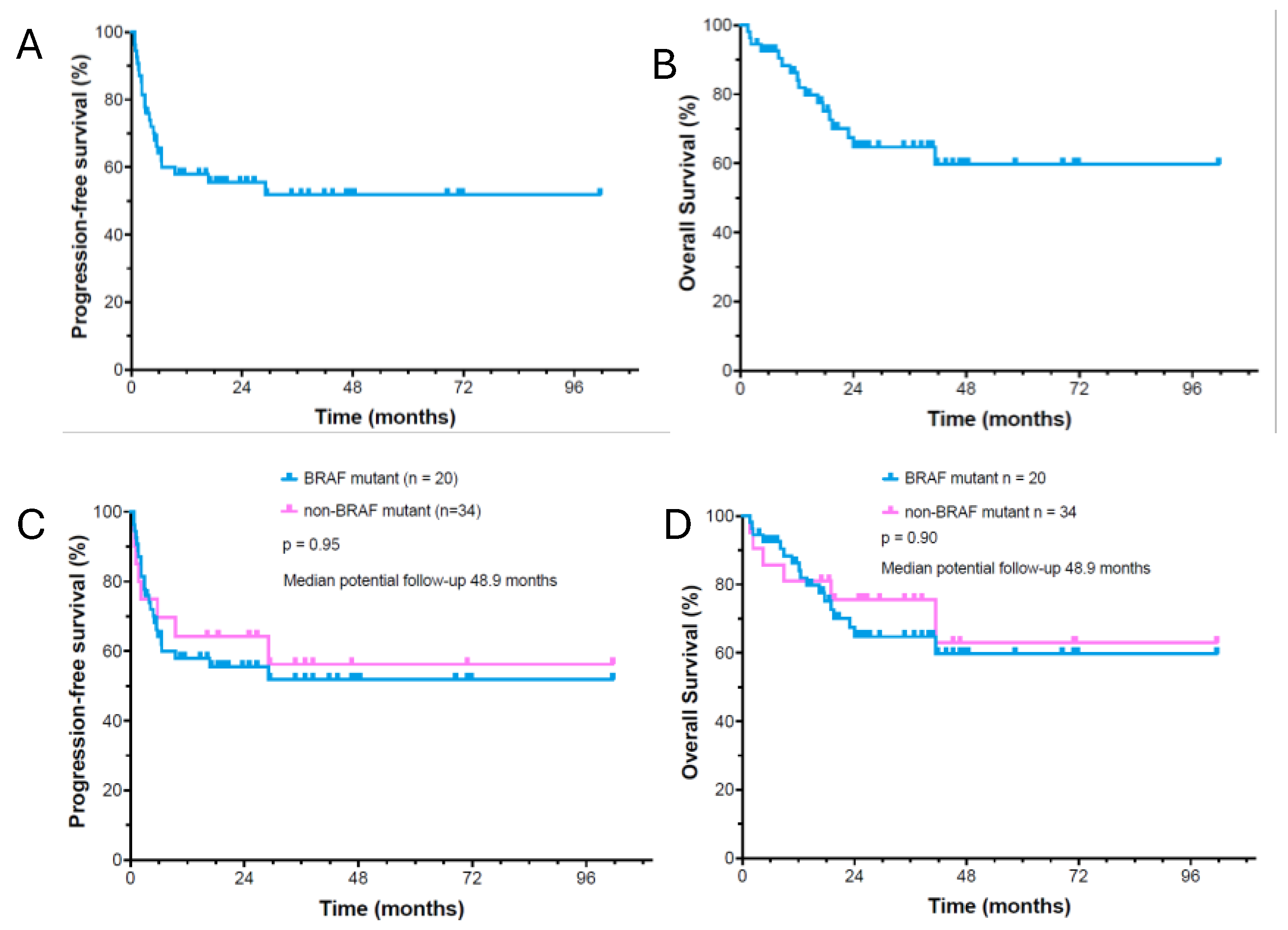

3.3. Treatment Outcome

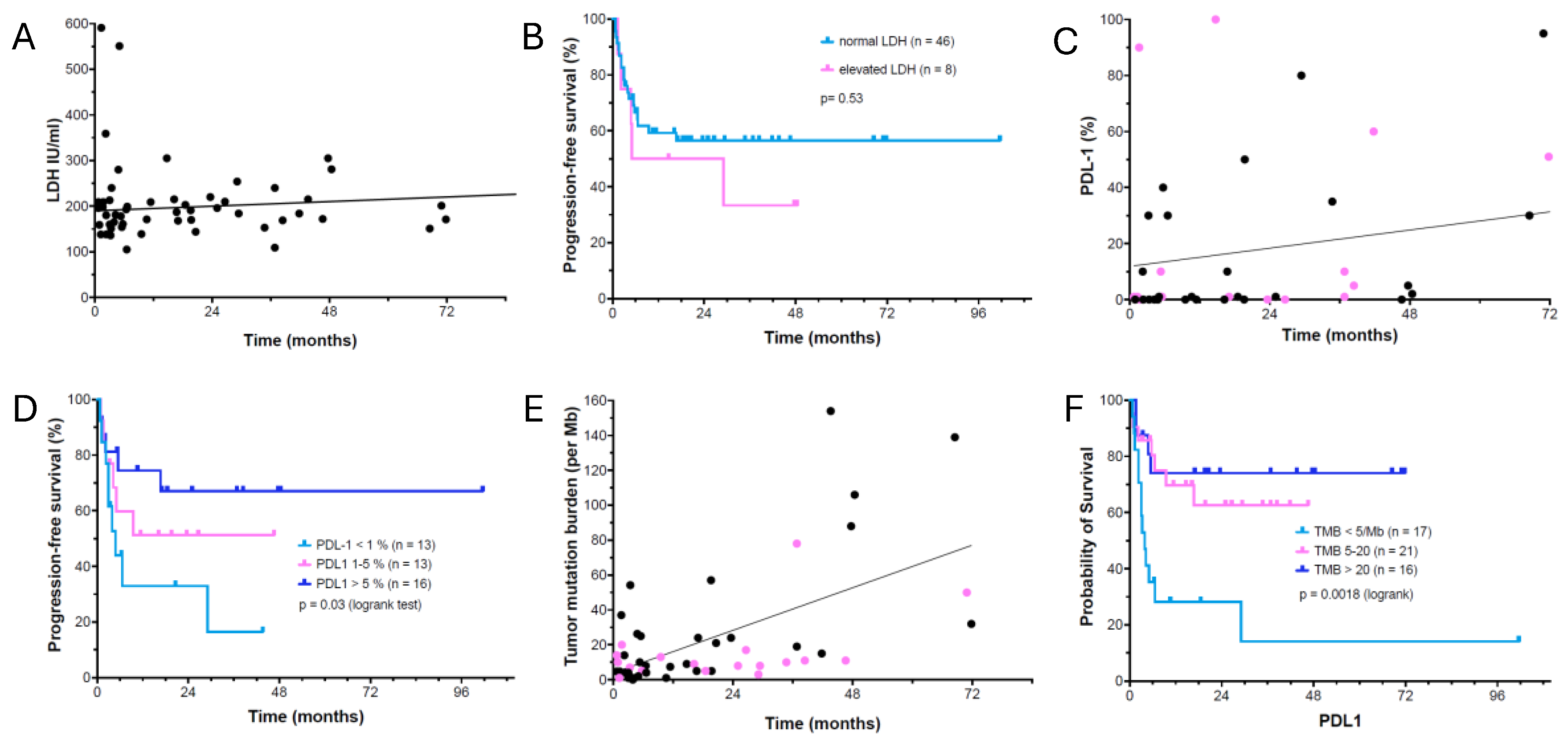

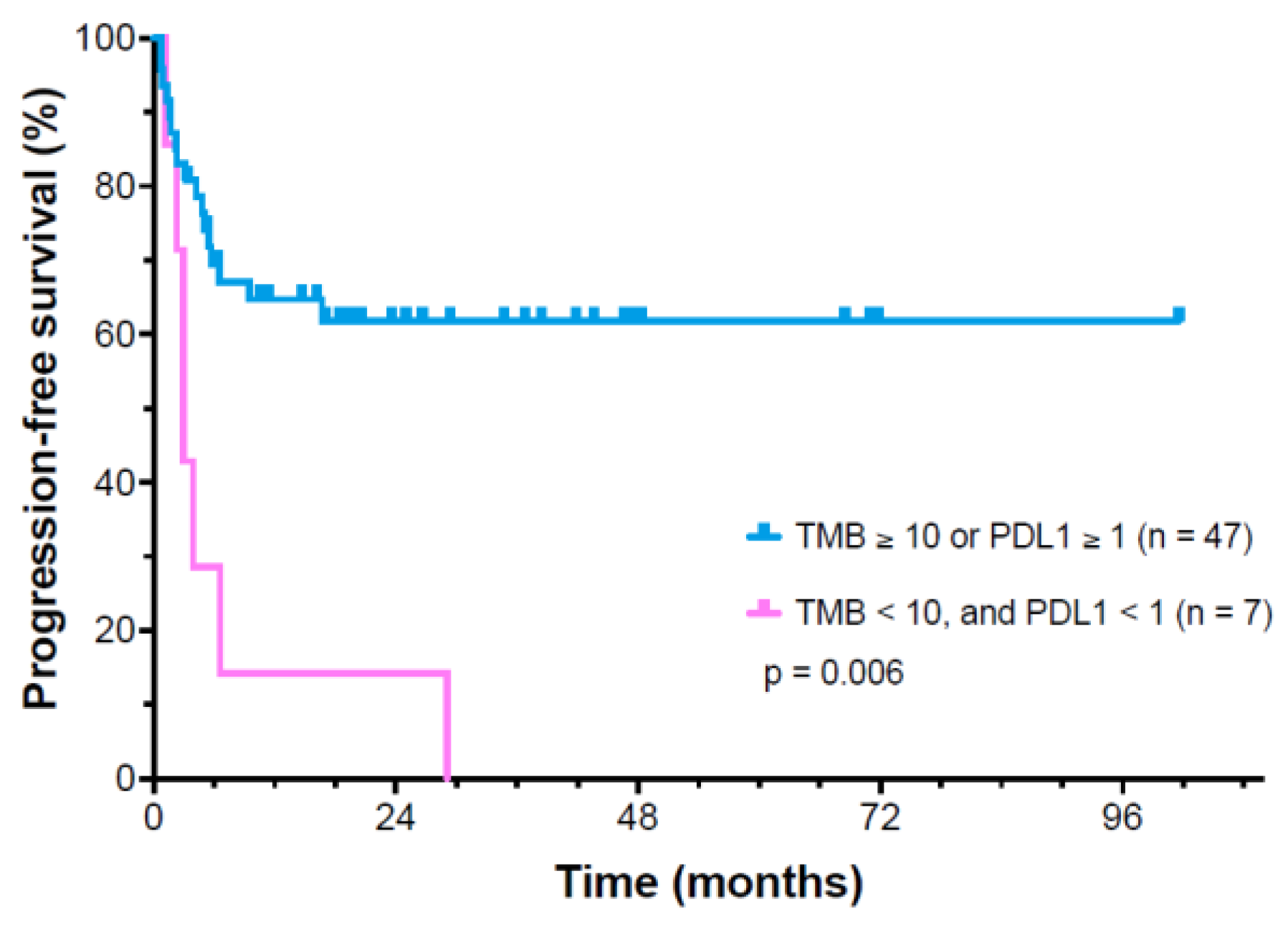

3.4. Analysis of Potential Predictive Markers for Ipilimumab/Nivolumab Response

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

| PD-L1 | PD-1 ligand |

| ICI | Immune checkpoint inhibitor |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| OS | Overall survival |

| irAE | Immune-related adverse event |

| TMB | Tumor mutation burden (per megabase) |

| BOR | Best objective response |

| CR | Complete remission |

| PR | Partial response |

| SD | Stable disease |

| PD | Progressive disease |

| SD | Standard deviation |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J Clin 2025, 75, 10–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutros, A.; Croce, E.; Ferrari, M.; Gili, R.; Massaro, G.; Marconcini, R.; Arecco, L.; Tanda, E.T.; Spagnolo, F. The treatment of advanced melanoma: Current approaches and new challenges. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2024, 196, 104276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Didier, A.J.; Nandwani, S.V.; Watkins, D.; Fahoury, A.M.; Campbell, A.; Craig, D.J.; Vijendra, D.; Parquet, N. Patterns and trends in melanoma mortality in the United States, 1999-2020. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, M.B.; Lee, S.J.; Chmielowski, B.; Tarhini, A.A.; Cohen, G.I.; Truong, T.G.; Moon, H.H.; Davar, D.; O'Rourke, M.; Stephenson, J.J.; et al. Combination Dabrafenib and Trametinib Versus Combination Nivolumab and Ipilimumab for Patients With Advanced BRAF-Mutant Melanoma: The DREAMseq Trial-ECOG-ACRIN EA6134. J Clin Oncol 2022, JCO2201763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolchok, J.D.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Rutkowski, P.; Cowey, C.L.; Schadendorf, D.; Wagstaff, J.; Queirolo, P.; Dummer, R.; Butler, M.O.; Hill, A.G.; et al. Final, 10-Year Outcomes with Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N Engl J Med 2025, 392, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, J.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; Grob, J.J.; Cowey, C.L.; Lao, C.D.; Schadendorf, D.; Dummer, R.; Smylie, M.; Rutkowski, P.; et al. Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab or Monotherapy in Untreated Melanoma. N Engl J Med 2015, 373, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michot, J.M.; Bigenwald, C.; Champiat, S.; Collins, M.; Carbonnel, F.; Postel-Vinay, S.; Berdelou, A.; Varga, A.; Bahleda, R.; Hollebecque, A.; et al. Immune-related adverse events with immune checkpoint blockade: a comprehensive review. Eur J Cancer 2016, 54, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson-Brown, A.; Jain, A.; Frazer, R.; Farrugia, D.; Carser, J.; Houghton, J.; Lewis, R.D.; D'Mello, S.; Emanuel, G. Clinical Management and Outcomes of Immune-Related Adverse Events During Treatment with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapies in Melanoma and Renal Cell Carcinoma: A UK Real-World Evidence Study. Oncol Ther 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keam, S.; Turner, N.; Kugeratski, F.G.; Rico, R.; Colunga-Minutti, J.; Poojary, R.; Alekseev, S.; Patel, A.B.; Li, Y.J.; Sheshadri, A.; et al. Toxicity in the era of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1447021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmer, J.R.; Abu-Sbeih, H.; Ascierto, P.A.; Brufsky, J.; Cappelli, L.C.; Cortazar, F.B.; Gerber, D.E.; Hamad, L.; Hansen, E.; Johnson, D.B.; et al. Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) clinical practice guideline on immune checkpoint inhibitor-related adverse events. J Immunother Cancer 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisoni, E.; Wicky, A.; Bouchaab, H.; Imbimbo, M.; Delyon, J.; Gautron Moura, B.; Gerard, C.L.; Latifyan, S.; Ozdemir, B.C.; Caikovski, M.; et al. Late-onset and long-lasting immune-related adverse events from immune checkpoint-inhibitors: An overlooked aspect in immunotherapy. Eur J Cancer 2021, 149, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dorst, D.C.H.; Uyl, T.J.J.; Van der Veldt, A.A.M.; Andrawes, T.; Joosse, A.; Oomen-De Hoop, E.; Danser, A.H.; Mathijssen, R.H.J.; Bos, D.; Versmissen, J. Onset and progression of atherosclerosis in patients with melanoma treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Immunother Cancer 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, G.V.; Larkin, J.; Schadendorf, D.; Grob, J.J.; Lao, C.D.; Marquez-Rodas, I.; Wagstaff, J.; Lebbe, C.; Pigozzo, J.; Robert, C.; et al. Pooled Long-Term Outcomes With Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab or Nivolumab Alone in Patients With Advanced Melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2025, 43, 938–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbour, A.P.; Tang, Y.H.; Armour, N.; Dutton-Regester, K.; Krause, L.; Loffler, K.A.; Lambie, D.; Burmeister, B.; Thomas, J.; Smithers, B.M.; et al. BRAF mutation status is an independent prognostic factor for resected stage IIIB and IIIC melanoma: implications for melanoma staging and adjuvant therapy. Eur J Cancer 2014, 50, 2668–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wilpe, S.; Koornstra, R.; Den Brok, M.; De Groot, J.W.; Blank, C.; De Vries, J.; Gerritsen, W.; Mehra, N. Lactate dehydrogenase: a marker of diminished antitumor immunity. Oncoimmunology 2020, 9, 1731942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donia, M.; Prasad, V. Dual Checkpoint Inhibition in Melanoma With >/=1% PD-L1-Time to Reassess the Evidence. JAMA Oncol 2024, 10, 860–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marabelle, A.; Fakih, M.; Lopez, J.; Shah, M.; Shapira-Frommer, R.; Nakagawa, K.; Chung, H.C.; Kindler, H.L.; Lopez-Martin, J.A.; Miller, W.H., Jr.; et al. Association of tumour mutational burden with outcomes in patients with advanced solid tumours treated with pembrolizumab: prospective biomarker analysis of the multicohort, open-label, phase 2 KEYNOTE-158 study. Lancet Oncol 2020, 21, 1353–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebbe, C.; Meyer, N.; Mortier, L.; Marquez-Rodas, I.; Robert, C.; Rutkowski, P.; Menzies, A.M.; Eigentler, T.; Ascierto, P.A.; Smylie, M.; et al. Evaluation of Two Dosing Regimens for Nivolumab in Combination With Ipilimumab in Patients With Advanced Melanoma: Results From the Phase IIIb/IV CheckMate 511 Trial. J Clin Oncol 2019, 37, 867–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, L.; Samlowski, W.; Lopez-Flores, R. Outcome of Elective Checkpoint Inhibitor Discontinuation in Patients with Metastatic Melanoma Who Achieved a Complete Remission: Real-World Data. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, E.A.; Therasse, P.; Bogaerts, J.; Schwartz, L.H.; Sargent, D.; Ford, R.; Dancey, J.; Arbuck, S.; Gwyther, S.; Mooney, M.; et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009, 45, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, E.L.; Meier, P. Nonparametric Estimation from Incomplete Observations. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1958, 53, 457–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, J.M.; Altman, D.G. The logrank test. BMJ 2004, 328, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diem, S.; Kasenda, B.; Spain, L.; Martin-Liberal, J.; Marconcini, R.; Gore, M.; Larkin, J. Serum lactate dehydrogenase as an early marker for outcome in patients treated with anti-PD-1 therapy in metastatic melanoma. Br J Cancer 2016, 114, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarchoan, M.; Albacker, L.A.; Hopkins, A.C.; Montesion, M.; Murugesan, K.; Vithayathil, T.T.; Zaidi, N.; Azad, N.S.; Laheru, D.A.; Frampton, G.M.; et al. PD-L1 expression and tumor mutational burden are independent biomarkers in most cancers. JCI Insight 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.A.; Zhao, F.; Letrero, R.; D'Andrea, K.; Rimm, D.L.; Kirkwood, J.M.; Kluger, H.M.; Lee, S.J.; Schuchter, L.M.; Flaherty, K.T.; et al. Correlation of somatic mutations and clinical outcome in melanoma patients treated with Carboplatin, Paclitaxel, and sorafenib. Clin Cancer Res 2014, 20, 3328–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eton, O.; Legha, S.S.; Moon, T.E.; Buzaid, A.C.; Papadopoulos, N.E.; Plager, C.; Burgess, A.M.; Bedikian, A.Y.; Ring, S.; Dong, Q.; et al. Prognostic factors for survival of patients treated systemically for disseminated melanoma. J Clin Oncol 1998, 16, 1103–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershenwald, J.E.; Scolyer, R.A.; Hess, K.R.; Sondak, V.K.; Long, G.V.; Ross, M.I.; Lazar, A.J.; Faries, M.B.; Kirkwood, J.M.; McArthur, G.A.; et al. Melanoma staging: Evidence-based changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin 2017, 67, 472–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariam, A.; Kamath, S.; Schveder, K.; McLeod, H.L.; Rotroff, D.M. Biomarkers for Response to Anti-PD-1/Anti-PD-L1 Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Large Meta-Analysis. Oncology (Williston Park) 2023, 37, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluger, H.M.; Zito, C.R.; Turcu, G.; Baine, M.K.; Zhang, H.; Adeniran, A.; Sznol, M.; Rimm, D.L.; Kluger, Y.; Chen, L.; et al. PD-L1 Studies Across Tumor Types, Its Differential Expression and Predictive Value in Patients Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res 2017, 23, 4270–4279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeone, E.; Grimaldi, A.M.; Ascierto, P.A. Anti-PD1 and anti-PD-L1 in the treatment of metastatic melanoma. Melanoma Manag 2015, 2, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, A.M.; Larkin, J.; Patel, S.P. Dual Immune Checkpoint Inhibition in Melanoma and PD-L1 Expression: The Jury Is Still Out. J Clin Oncol 2025, 43, 122–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandara, D.R.; Agarwal, N.; Gupta, S.; Klempner, S.J.; Andrews, M.C.; Mahipal, A.; Subbiah, V.; Eskander, R.N.; Carbone, D.P.; Riess, J.W.; et al. Tumor mutational burden and survival on immune checkpoint inhibition in >8000 patients across 24 cancer types. J Immunother Cancer 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodi, F.S.; Wolchok, J.D.; Schadendorf, D.; Larkin, J.; Long, G.V.; Qian, X.; Saci, A.; Young, T.C.; Srinivasan, S.; Chang, H.; et al. TMB and Inflammatory Gene Expression Associated With Clinical Outcomes Following Immunotherapy in Advanced Melanoma. Cancer Immunol Res 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, M.C.; Li, G.; Graf, R.P.; Fisher, V.A.; Mitchell, J.; Aboosaiedi, A.; O'Rourke, H.; Shackleton, M.; Iddawela, M.; Oxnard, G.R.; et al. Predictive Impact of Tumor Mutational Burden on Real-World Outcomes of First-Line Immune Checkpoint Inhibition in Metastatic Melanoma. JCO Precis Oncol 2024, 8, e2300640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugh, A.M.; Osorio, R.C.; Francois, R.A.; Tawil, M.E.; Tsai, K.K.; Tetzlaff, M.; Daud, A.; Vasudevan, H.N. Targeted DNA Sequencing of Cutaneous Melanoma Identifies Prognostic and Predictive Alterations. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forschner, A.; Battke, F.; Hadaschik, D.; Schulze, M.; Weissgraeber, S.; Han, C.T.; Kopp, M.; Frick, M.; Klumpp, B.; Tietze, N.; et al. Tumor mutation burden and circulating tumor DNA in combined CTLA-4 and PD-1 antibody therapy in metastatic melanoma - results of a prospective biomarker study. J Immunother Cancer 2019, 7, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, B.; Liu, Y.; Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Xu, T.; Wei, Y. The Predictive Value of Tumor Mutation Burden on Clinical Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Melanoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 748674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M. Tumor mutation burden for predicting immune checkpoint blockade response: the more, the better. J Immunother Cancer 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).