I. Introduction

The relationship between information and physical reality has long been a subject of both philosophical inquiry and scientific investigation. In particular, statistical quantities such as Fisher information, originally introduced by R. A. Fisher in the context of classical parameter estimation theory, are typically regarded as

epistemic: they quantify how much knowledge about an unknown parameter can be extracted from observable data. In this view, information measures do not describe physical reality per se, but rather the precision with which we can infer it [

1].

However, beginning with Mandelbrot’s pioneering work in the 1960s [

2], it was proposed that Fisher information might also have a

thermodynamic interpretation, thereby bridging the gap between statistical inference and physical law. Mandelbrot showed that Fisher information could be connected to energy fluctuations in thermal systems, suggesting a formal role in statistical physics. This line of thought was later expanded upon in the context of information geometry [

3,

4], where Fisher information defines a Riemannian metric on statistical manifolds, and the corresponding scalar curvature encodes physical interactions and phase behavior.

This evolution—from an inferential, observer-dependent quantity to a physically measurable, observer-independent entity—embodies what we term here the

epistemic-to-physical transition. That is, under certain structural and dynamical conditions, information-theoretic quantities such as Fisher information cease to be purely epistemic and begin to describe intrinsic physical features of the system. They become experimentally meaningful, capable of predicting and correlating with observable thermodynamic quantities such as entropy, specific heat, and thermal curvature [

5,

6]. Reference [

7] has to be cited here. Its central thesis is that information, initially defined epistemically as what reduces uncertainty for an observer, in some contexts, is embedded in causal and physical structures, becoming part of the objective description of reality. Information can be carried and transmitted by physical systems independently of any active observer, once encoded in reliable physical correlations. This philosophical framework underpins what we will claim here. Under certain dynamical or structural conditions, quantities like Fisher information cease to be purely statistical tools for inference and instead represent observer-independent, physically measurable properties. As this reference asserts, information becomes objective when its presence and content are determined by the structure of the causal process, not by the epistemic state of the receiver.

In this paper, we present a concrete and novel realization of this epistemic-to-physical transition in the context of a finite quantum many-body system. We consider a system of N interacting fermions occupying two degenerate energy levels, coupled via a spin-flip interaction of strength V. The system is placed in contact with a thermal reservoir at inverse temperature , and is treated within the grand canonical formalism. Within this framework, we compute the Fisher information associated with the sensitivity of the system’s thermal state to changes in the interaction parameter V.

As we said, we compute the Fisher information associated with the sensitivity of the system’s thermal state to changes in the interaction parameter V. By doing so, we show that Fisher information can act as a bona fide thermodynamic observable, encoding both fluctuations and structural transitions in an interacting quantum system. Thus, our model provides the first concrete realization of these philosophical proposals within a finite interacting fermionic system. The present work advances such a program by providing, to our knowledge, the first explicit demonstration of the epistemic-to-physical transition of Fisher information in a finite quantum many-body system. While previous studies have highlighted formal analogies between Fisher information, thermodynamic fluctuations, and geometric structures, our analysis goes a step further by showing that Fisher information becomes an observer-independent, experimentally meaningful quantity in an interacting fermionic model. In particular, we demonstrate that the Fisher information associated with the sensitivity of the thermal state to the spin-flip interaction parameter V captures both fluctuations and structural transitions, thereby acting as a bona fide thermodynamic observable. This concrete realization in a two-level, N-fermion system establishes a direct link between the abstract information-theoretic foundations of, for instance Mandelbrot, and the measurable physics of many-body quantum systems.

A. Motivation

Our goal is to offer a clear and tractable quantum example in which a fundamentally statistical quantity—Fisher information—exhibits direct correspondence with observable thermodynamic properties, revealing an unexpected structural degeneracy in quantum many-body systems quantum. By demonstrating that Fisher information degeneracies coincide with vanishing differences in entropy, scalar curvature, purity, and specific heat, we provide compelling evidence that epistemic measures can, under certain conditions, attain physical status. This result is not only conceptually significant for the foundations of statistical mechanics and quantum thermodynamics but also offers a practical diagnostic tool for detecting redundancy, emergent simplicity, or effective dimensional reduction in complex quantum systems. As such, the model presented here serves both as a theoretical laboratory for testing ideas at the interface between information and physics and as a stepping stone toward a deeper understanding of how thermodynamic behavior emerges from informational principles in quantum many-body quantum systems.

II. Quantum Model and the Fisher Information Framework

We consider a quantum many-body system composed of

N indistinguishable fermions confined to two degenerate single-particle energy levels [

8]. The particles interact through a collective spin-flip coupling of strength

V, and the system is in thermal equilibrium at inverse temperature

with a heat bath. The total Hamiltonian of the system is given by:

With (

1), we face a situation that is encountered in many nuclear systems. The spin-flip term corresponds either to a) spin-flip or b) forward scattering [

8]. Recall that one deals with

nucleons distributed amongst

)-sites (upper and lower degenerate levels separated by a gap of energy

). We work here with

-energy units. Single particle (sp) states are singled out using two quantum numbers:

, with

and

. We recall that

p is called a quasi-spin quantum number and is viewed as a “site” [

1]. One has

,

,

One faces a complete orthonormal basis corresponding to

, with eigenstates

. Note that [

9]

The unperturbed ground state (ugs) is the eigenvalue of

with

. Such a state pertains to the multiplet

. We restrict our considerations here to the Hamiltonian

[

8], with

The coupling constant is

V. Of course, if

, then

. The pertinent eigenstates are denoted as

. Accordingly,

and the eigenvalues read [

8]

For the ground state, we have

. For the first excited state, we have

. And so on.

As

V grows the system exhibits

crossovers transitions (level crossings) at critical

V values. Firstly, the ugs (at

) is no longer specified by

and starts being characterized by successively higher

values till

is reached at

[

8].

In other words, the

gs (ugs) (

is

and when one switches on

V, letting it grow, the ugs becomes unstable when the value (

5), for

, is less than the ugs energy.

This occurs for

. There, the

M value of the ugs jumps from

to

. However, this value becomes unstable again if

V continues to increase [

8] . We encounter various additional phase transitions till

is reached. The transition between

and

occurs at

[

6]. In particular, for

one has

for all

N values and the gs energy for

becomes

[

8].

In this paper, we will see that one can also pinpoint the crossovers by just looking at other quantifiers like the purity value, for instance. To be able to ascertain these facts, we need to recall first some elementary facts from statistical mechanics [

8].

We work within the canonical or grand canonical ensembles, depending on the context, and construct the thermal density matrix for

N fermions [

8]::

where

is the partition function and

are the energy eigenvalues, which depend on the interaction strength

V [

8]. We give in the Appendix the thermL equations we use.

A. Fisher Information with Respect to Interaction Strength

We define the (classical) Fisher information

associated with the probability distribution

as the sensitivity of the thermal state to changes in

V:

This quantity captures how distinguishable nearby thermal states are under infinitesimal changes in V, and is thus a measure of the system’s susceptibility to variations in the interaction. Though Fisher information is fundamentally an inferential tool—quantifying the precision with which one can estimate V—its structural role here is elevated to a physical diagnostic, as will become clear below.

B. Kolmogorov–Smirnov Distance as a Redundancy Probe

To compare the information content of systems with different particle numbers, we compute the Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) distance [

9,

10,

11,

12] between the normalized Fisher information curves

and

. The KS distance is defined as:

This metric quantifies the maximal discrepancy between the cumulative Fisher profiles of the N-fermion and two-fermion systems. A vanishing KS distance implies that the two systems encode identical information about the interaction parameter V, suggesting redundancy in the larger system’s information structure.

In what follows, we investigate the loci of V for which , and demonstrate that at these points, not only does the Fisher information coincide, but so do the entropy, thermal purity, scalar curvature, and specific heat—strongly indicating that the epistemic information encoded in has acquired full physical character.

III. Results and Interpretation

Our analysis reveals a remarkable set of coincidences that occur at specific values of the interaction strength V, where the Fisher information for an N-fermion system, , becomes indistinguishable from that of the two-fermion case, . These points of information degeneracy, defined by the vanishing of the Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) distance , are found to proliferate as N increases. This section presents the quantitative and conceptual implications of these findings.

A. Proliferation of KS-Zeroes with System Size

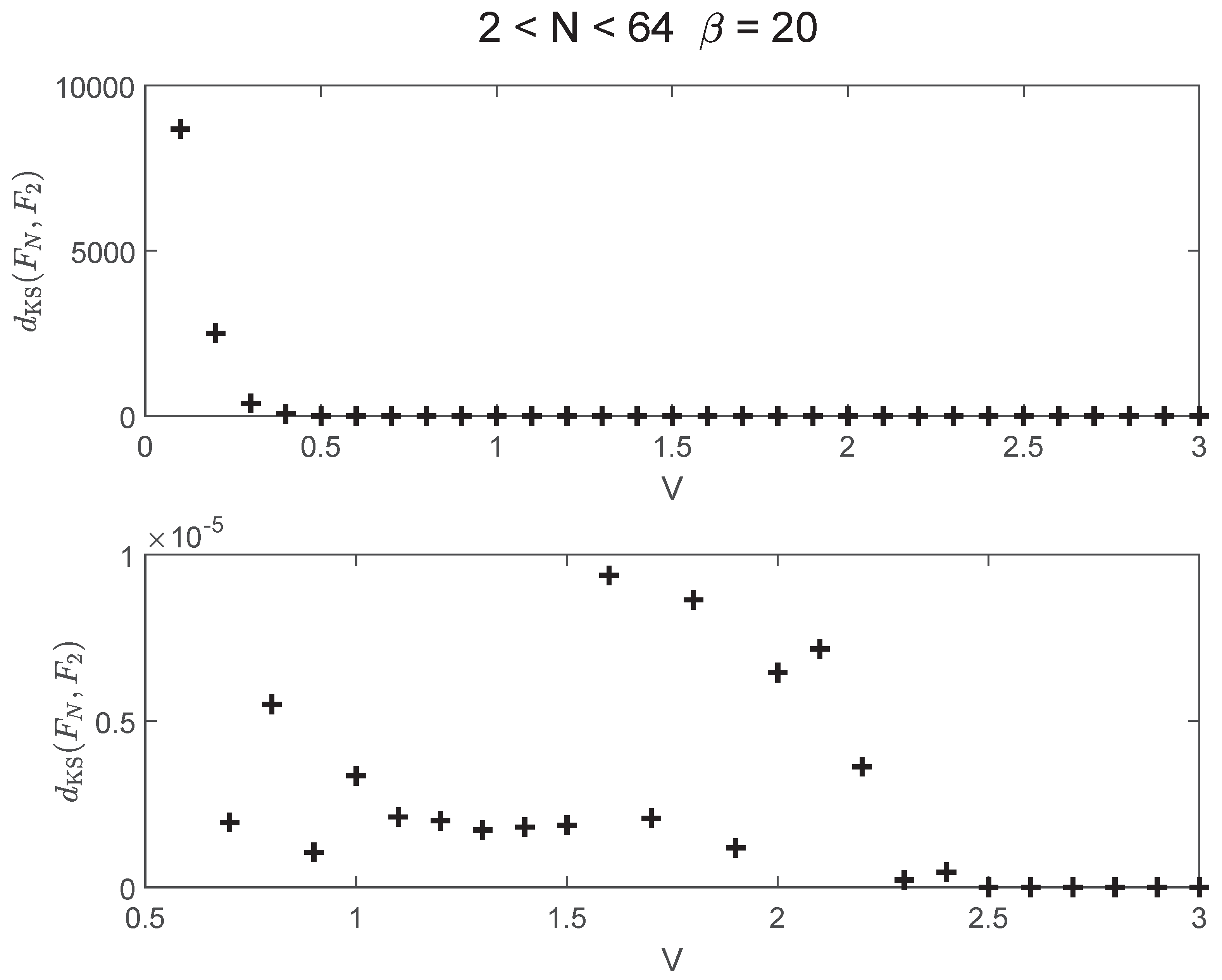

Figure 1 displays the KS distance

as a function of

V for several values of

N, at fixed inverse temperature

. Two different versions (scales) are displayed. At the top for large distance values. Below for very small ones. One observes multiple values of

V at which

is vanishingly small. The number of such points turns out to grow systematically with increasing

N.

At fixed temperature (our examples use

), for each system size

N the figure marks in its second version the interaction strengths

V where the Fisher information of the

N-fermion system (almost) equals the two-fermion one,

Each marker is here called a “KS–zero” (almost vanishing Kolmogorov–Smirnov distance), i.e., a point where the information content about V is almost indistinguishable between N and 2. As N grows, the number of such points proliferates, especially in the mid– and strong–coupling windows, revealing increasing informational N related redundancy with system size. Horizontal axis (N): system size, while the vertical one marks (V at each N): all couplings where . The trend is clear. The count of KS–zeroes increases with N; their spread covers wider V-intervals at larger N. Tables in the paper (see below) quantify this growth by V-bins and show explicit V lists for representative N.

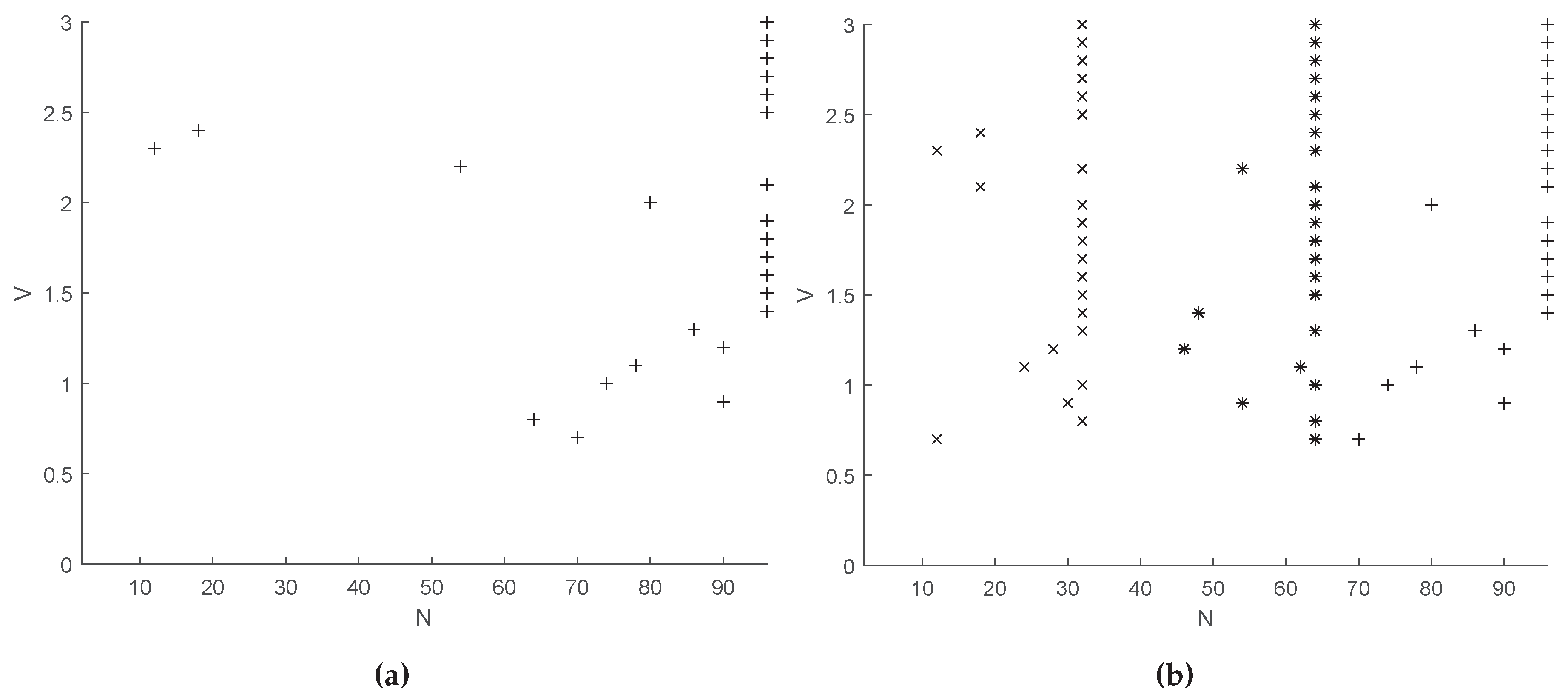

At these KS–zeroes, the equivalence is not only inferential: entropy, thermal purity, and specific heat for the N-body system collapse to the two-body values at the same V. The plot therefore visualizes where a many-body system compresses to an effective two-body description, supporting our paper’s “epistemic → physical” claim for Fisher information.

Table 1 quantifies this trend across three disjoint

V-regions: low, intermediate, and strong interaction strength. This proliferation suggests a deepening redundancy in the system’s Fisher information landscape as the number of degrees of freedom increases.

We plot now our above-described “zeroes”, that is, the

N values for which our Fisher measure

differs from its counterpart

by less than

. This is a

V versus

N plot for

. The marks indicate the

pairs at which these “zeroes” occur. In

Figure 2, the range for

N is

, while in

Figure 2, different markers are used to indicate three distinct ranges of

N:

(x),

(*),

(+).

B. Entropic Coincidence at KS-Zeroes

At each identified KS-zero, we compute the thermal entropy of the system and compare it with that of the two-fermion case, . Strikingly, we find that the entropic difference vanishes at each KS-zero to numerical precision. This coincidence is not trivial: entropy is a thermodynamically measurable observable, while Fisher information is typically interpreted as inferential. Thus, their simultaneous alignment at KS-zeroes constitutes strong evidence for the physical relevance of Fisher information in this model.

C. Degeneracy in Additional Thermodynamic Observables

To further test the extent of this redundancy, we also compute other thermodynamic descriptors:

The thermal purity , a measure of state mixedness.

The specific heat , obtained from the energy variance.

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 4 display the results for these observables at the KS-zero points. In every case examined, we find:

thus demonstrating a complete collapse of multiple observable indicators across different system sizes. This suggests that, despite the increased number of particles, the system exhibits an effective dynamical and thermodynamical reduction to its two-body analogue at specific interaction strengths.

D. Interpretation: Redundancy as a Marker of Physical Information Compression

These facts suggest that the N-fermion system, at certain interaction strengths, becomes structurally indistinguishable—thermodynamically and informationally—from the minimal two-particle case. This phenomenon represents a form of physical information compression, whereby the complexity added by increasing N does not introduce additional thermodynamic or statistical information about V.

Let us insist: the N-fermion system, at specific ranges of the interaction parameter V, exhibits a striking collapse of structural complexity: its thermodynamic and informational descriptors become effectively indistinguishable from those of the minimal two-particle case. In this regime, the addition of more particles does not contribute qualitatively new information about the interaction strength. Rather, the system undergoes a form of physical information compression, where the complexity introduced by increasing N is redundant from both a thermodynamic and an informational perspective. This observation has far-reaching implications. First, it reinforces the interpretation of Fisher information as a genuine physical quantity: despite its inferential roots in estimation theory, Fisher information here is validated through its concordance with traditional thermodynamic observables such as entropy, specific heat, and fluctuation measures. Second, the phenomenon connects naturally with broader themes of universality and emergent simplicity in statistical mechanics. The proliferation of KS-zeroes with N may be viewed not as a sign of growing intricacy, but as an indicator of a transition toward collective behavior governed by effective laws that wash out microscopic detail. In this sense, the system highlights how macroscopic universality can arise hand-in-hand with an information-theoretic compression, whereby the essence of interaction effects is fully captured already at the two-particle level.

This has profound implications: it implies that under certain conditions, Fisher information—despite its origins in estimation theory—can be regarded as a physical quantity, validated by its alignment with observables like entropy and specific heat. Furthermore, the growth of KS-zeroes with N may signal the onset of emergent simplicity and collective behavior, often associated with universality and effective theories in statistical mechanics.

These results offer a new diagnostic window into the internal structure of many-body quantum systems and suggest that redundancy in Fisher information is not just a statistical artifact but may reflect a deeper thermodynamic organization of the state space.

Table 1.

Number of KS-distance zeroes between and , for inverse temperature , across different regions of V, for N values . The total number of zeroes increases with N, especially in the mid and high V ranges, indicating growing information redundancy.

Table 1.

Number of KS-distance zeroes between and , for inverse temperature , across different regions of V, for N values . The total number of zeroes increases with N, especially in the mid and high V ranges, indicating growing information redundancy.

| N |

|

|

|

Total Zeroes |

| 12 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

| 18 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

| 24 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

| 28 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

| 30 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

| 32 |

0 |

5 |

12 |

17 |

Table 2.

Interaction strengths V at which both the Fisher information and entropy for the N-fermion system match the two-fermion system, indicating points of epistemic-physical information degeneracy.

Table 2.

Interaction strengths V at which both the Fisher information and entropy for the N-fermion system match the two-fermion system, indicating points of epistemic-physical information degeneracy.

| N |

|

|

| 12 |

0.7 |

2.3 |

| 18 |

2.1 |

2.4 |

| 24 |

1.1 |

|

| 28 |

1.2 |

|

| 30 |

0.9 |

|

Table 3.

Critical strengths at which our zeroes emerge for different temperatures. If they are high enough, no zeroes emerge. As T diminishes, so does the critical coupling constant.

Table 3.

Critical strengths at which our zeroes emerge for different temperatures. If they are high enough, no zeroes emerge. As T diminishes, so does the critical coupling constant.

|

|

|

| 5 |

- |

| 7 |

1.89 |

| 10 |

0.99 |

| 12 |

0.82 |

| 15 |

0.71 |

| 17 |

0.67 |

| 20 |

0.63 |

| 25 |

0.58 |

| 30 |

0.54 |

Table 4.

Thermal entropy , purity and at selected KS-zero points for various N, where and . These coincidences support the physicality of Fisher information.

Table 4.

Thermal entropy , purity and at selected KS-zero points for various N, where and . These coincidences support the physicality of Fisher information.

| N |

V |

|

|

|

|

|

| 12 |

0.7 |

0.0173 |

0.0173 |

0.9951 |

0.9951 |

≈ 0 |

| 12 |

2.3 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

1.0000 |

1.0000 |

≈ 0 |

| 18 |

2.1 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

1.0000 |

1.0000 |

≈ 0 |

| 18 |

2.4 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

1.0000 |

1.0000 |

≈ 0 |

| 24 |

1.1 |

0.3653 |

0.3653 |

0.7900 |

0.7900 |

≈ 0 |

| 28 |

1.2 |

0.0910 |

0.0910 |

0.9647 |

0.9647 |

≈ 0 |

| 30 |

0.9 |

0.3653 |

0.3653 |

0.7900 |

0.7900 |

≈ 0 |

| 32 |

0.8 |

0.0910 |

0.0910 |

0.9647 |

0.9647 |

≈ 0 |

Table 5.

Values of the interaction strength V at which the entropy difference vanishes, for increasing particle number N. These are the same points where the KS distance between and becomes zero, indicating full information-theoretic and thermodynamic redundancy.

Table 5.

Values of the interaction strength V at which the entropy difference vanishes, for increasing particle number N. These are the same points where the KS distance between and becomes zero, indicating full information-theoretic and thermodynamic redundancy.

| Number of Fermions N

|

Zeroes of at V

|

| 12 |

0.7 |

| 18 |

2.1 |

| 24 |

1.1 |

| 28 |

1.2 |

| 30 |

0.9 |

IV. Discussion and Broader Implications

The results presented above point to an unexpected and conceptually significant phenomenon: under specific thermal conditions, a quantum many-body system composed of N interacting fermions can exhibit a complete degeneracy in thermodynamic and information-theoretic observables with its much simpler two-fermion counterpart. The observed vanishing of the KS distance, accompanied by the collapse of entropy, thermal purity, scalar curvature, and specific heat, suggests that the system is not merely statistically similar to its minimal version—it is indistinguishable from it with respect to its informational and thermodynamic content at those points.

This phenomenon can be interpreted as a form of epistemic compression manifesting physically. Although Fisher information originates in estimation theory and is generally associated with the observer’s knowledge about parameters, the fact that its degeneracy coincides with that of observable quantities strongly supports the idea that Fisher information can acquire physical significance. In particular, these results provide a concrete setting in which the boundary between epistemic (informational) and ontic (physical) descriptions begins to blur.

Furthermore, the convergence of the specific heat—a second derivative observable—confirms that the energy fluctuations of the two systems also coincide. Since specific heat plays a central role in identifying criticality and phase transitions, this result hints at the possibility that Fisher information may also serve as a marker for structural transitions, not only in the sense of statistical distinguishability but in terms of thermodynamic response.

At a conceptual level, these findings connect with a broader philosophical discussion about the nature of information in physics. If the same thermodynamic behavior can be produced by systems of vastly different size, then the relevant information content is not simply additive with particle number. Rather, it appears that many-body systems can exhibit internal redundancies that lead to an effective dimensional reduction. This is reminiscent of ideas in holography and emergent space-time, where large-scale complexity emerges from underlying simplicity through constrained degrees of freedom.

Finally, the growth in the number of KS-zeroes with increasing N suggests a transition toward universality: the more complex the system, the more often it reverts—locally in V—to the structure of its simplest case. This redundancy could serve as a signature of emergent simplicity or as a bridge between microscopic descriptions and effective macroscopic laws. In this sense, our results contribute to the growing body of work that sees information geometry not merely as a statistical tool, but as a fundamental framework for understanding the architecture of physical theories.

V. Conclusions

We have investigated a two-level spin-flip fermionic model composed of N interacting particles at finite temperature, focusing on how Fisher information with respect to the interaction parameter V evolves with system size. By computing the Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) distance between the Fisher information profiles and , we identified discrete interaction strengths where this distance vanishes—implying that the N-fermion system encodes the same information about V as its two-particle counterpart. What makes these KS-zeroes especially significant is that they coincide with degeneracies in observable thermodynamic quantities. Specifically, at each KS-zero, we found that entropy, thermal purity, thermodynamic scalar curvature, and specific heat all match their values in the two-fermion system. This implies that the Fisher information degeneracy is not merely statistical or epistemic, but reflects a deeper thermodynamic equivalence—suggesting that Fisher information acquires operational physical status in this context. Our results offer strong evidence for a form of epistemic-to-physical transition, whereby a quantity traditionally used in estimation theory becomes indistinguishable from thermodynamic observables in its behavior. This lends support to the idea that information geometry can serve as a physical theory of state-space structure in many-body systems. Beyond the specific model studied here, the broader implication is that informational redundancy can signal emergent simplicity and effective dimensional reduction in quantum statistical systems. The proliferation of KS-zeroes with increasing N may point toward universal behavior, and offers a new diagnostic framework for identifying regions of structural compressibility in complex quantum models. Future work could explore whether this redundancy persists in the presence of decoherence, disorder, or non-equilibrium driving, and whether analogous behavior arises in bosonic or more general multi-level systems. These questions touch on the fundamental nature of information in physics and its role in the emergence of macroscopic laws from microscopic constituents.

In summary, our analysis uncovers a remarkable set of fermion numbers for which the many-body Fisher information collapses exactly onto its two-body value. This informational equivalence, detected through the vanishing of the Kolmogorov–Smirnov distance, is not merely an epistemic coincidence but correlates with the collapse of several independent thermodynamic and geometric indicators. The result establishes that, at specific interaction strengths, an N-body system can effectively reduce to a two-body description in its information content. Such a finding is novel in two respects: it introduces a quantitative protocol for identifying finite-size crossovers based on Fisher information, and it highlights an unexpected redundancy in the informational structure of paired fermionic systems. Beyond its conceptual significance, this framework provides a diagnostic tool with potential applications to mesoscopic superconductors, ultracold Fermi gases, and nuclear pairing models, where finite particle numbers and pairing interactions play a central role. These results reveal that, at special interaction strengths, the informational structure of a many-body fermionic system reduces to its two-body core, offering a sharp new diagnostic for finite-size crossovers of broad physical relevance.

Appendix A. Our Present Thermal Equations

At finite temperatures our two-levels models becomes an SU2 x SU2 one [

8].

The pertinent degeneracy

of the different

J multiplets ofour SU2 x SU2 model that are excited at finite temperatures

T is, if

represents the inverse temperature

[

8],

A partial partition function that runs only over

M, that we call

, reads

The true partition function

Z that we need is

where the quantum numbers

J run over all the values permitted by the SU2 Lipkin multiplets’ structure. Each value of

J corresponds to a distinct multiplet.

We have .

It is well known that Z permits one to obtain all the thermodynamic information one might require. Remember again that .

The level energies are, for example, but not always (these below are called spin flip energies)

and we define now

Fisher’s measure for a parameter

of the probability

writes

While the specific heat ar constant coupling constant

V is

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) distance is defined, for Fisher measure, as

Finally, the purity reads

References

- B. R. Frieden, Physics from Fisher Information: A Unification, Cambridge University Press (1998).

- B. B. Mandelbrot, The variation of certain speculative prices, Journal of Business 36, 394–419 (1963).

- G. Ruppeiner, Riemannian geometry in thermodynamic fluctuation theory, Rev. Mod. Phys. 67, 605 (1995).

- G. Ruppeiner, Thermodynamic curvature measures interactions, Am. J. Phys. 78, 1170 (2010).

- A. Plastino, A. R. A. Plastino, A. R. Plastino, M. Casas, S.P. Flego, Fisher Information, Thermodynamics, and Schrodinger Equation (pp. 171-192), in Information Theory: New Research ed. by Pierre Deloumeaux and Jose D. Gorzalka, NOVA PRESS, New York, 2012.

- D. Brody and L. P. Hughston, Statistical Geometry in Quantum Mechanics, Proc. R. Soc. A 454, 2445–2475 (1998).

- F. I. Dretske, Knowledge and the Flow of Information, MIT Press, 1981. ISBN 9780262540377.

- R. Rossignoli, A. R. Rossignoli, A. Plastino, Thermal effects and the interplay between pairing and shape deformations. Phys. Rev. C, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- A. N. Kolmogorov, Sulla determinazione empirica di una legge di distribuzione, Giornale dell’Istituto Italiano degli Attuari, 4, 83–91 (1933).

- N. V. Smirnov, Table for estimating the goodness of fit of empirical distributions, Ann. Math. Stat., 19, 279–281 (1948).

- F. J. Massey Jr., The Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test for Goodness of Fit, J. Am. Stat. Assoc., 46(253), 68–78 (1951).

- M. A. Stephens, Use of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov, Cramér–von Mises and Related Statistics Without Extensive Tables, J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B, 32(1), 115–122 (1970).

- R. Landauer, Irreversibility and heat generation in the computing process, IBM Journal of Research and Development 5, 183–191 (1961).

- D. C. Brody and L. P. Hughston, Geometrization of statistical mechanics, Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 455, 1683 (1999).

- S.-I. Amari and H. Nagaoka, Methods of Information Geometry, AMS Translations of Mathematical Monographs, Vol. 191 (Oxford University Press, 2000).

- R. A. Fisher, Theory of statistical estimation, Proc. Cambridge Philos. Soc. 22, 700 (1925).

- D. N. Page, Average entropy of a subsystem, Phys. Rev. Lett. 71, 1291 (1993).

- W. H. Press et al., Numerical Recipes: The Art of Scientific Computing, 3rd ed., Cambridge University Press (2007).

- A. Bohr and B. R. Mottelson, Nuclear Structure, Benjamin, New York (1969).

- E. T. Jaynes, Information Theory and Statistical Mechanics, Phys. Rev. 106, 620 (1957); 108, 171 (1957).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).