Submitted:

02 September 2025

Posted:

03 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Mechanism-Based Classification

2.1. Nature-Based Solutions

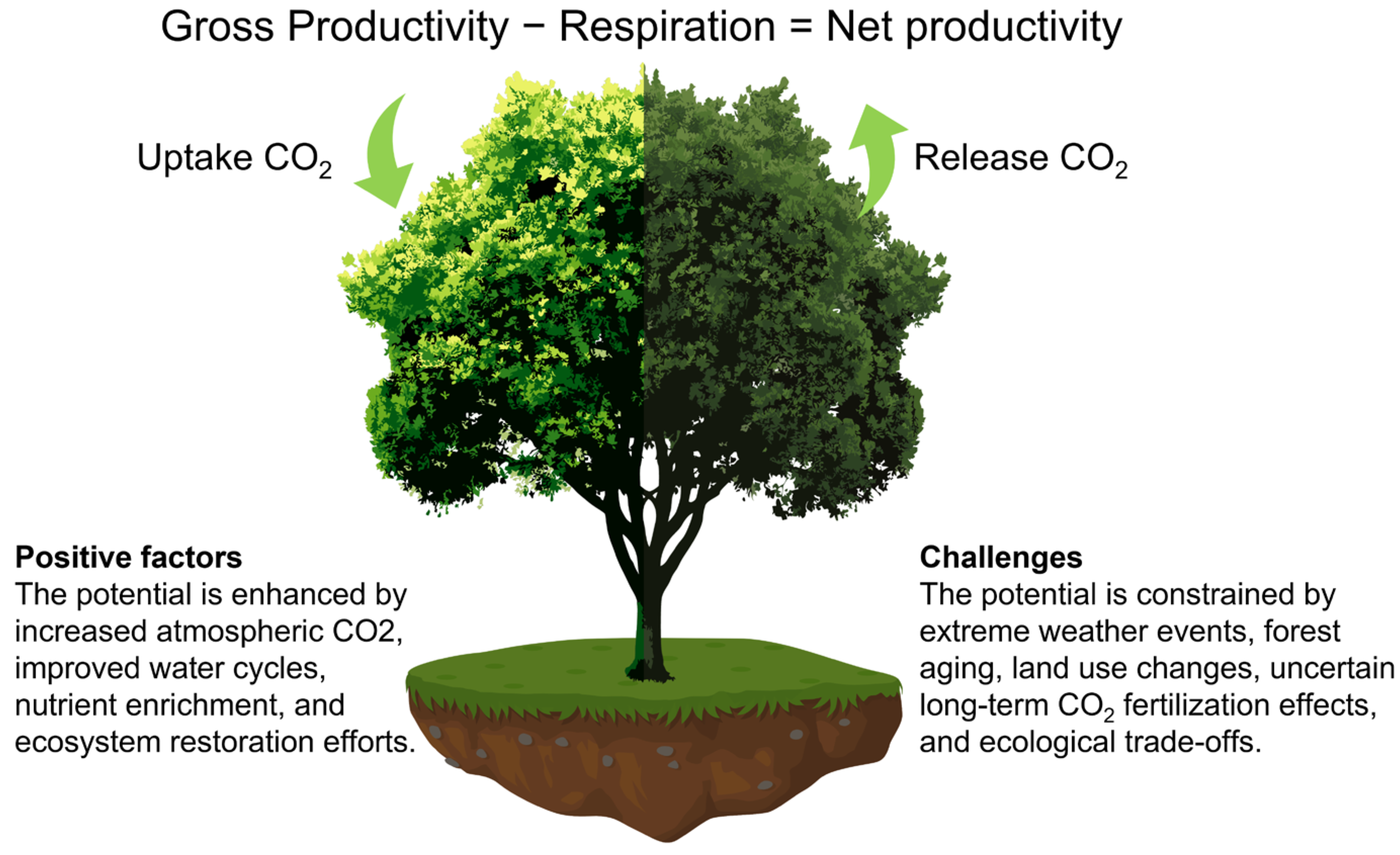

2.1.1. Terrestrial Ecosystems Pathway

2.1.2. Marine Ecosystems

2.2. Artificial Carbon Sequestration Pathways

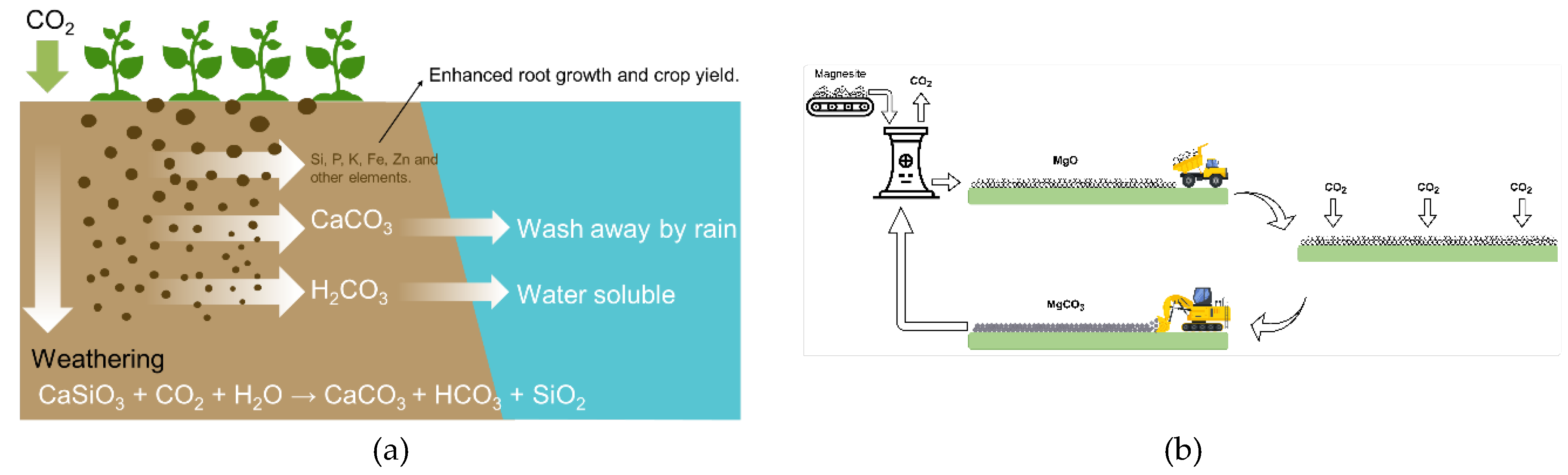

2.2.1. Geological-Mineralogical Pathways

2.2.2. Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage (CCUS)

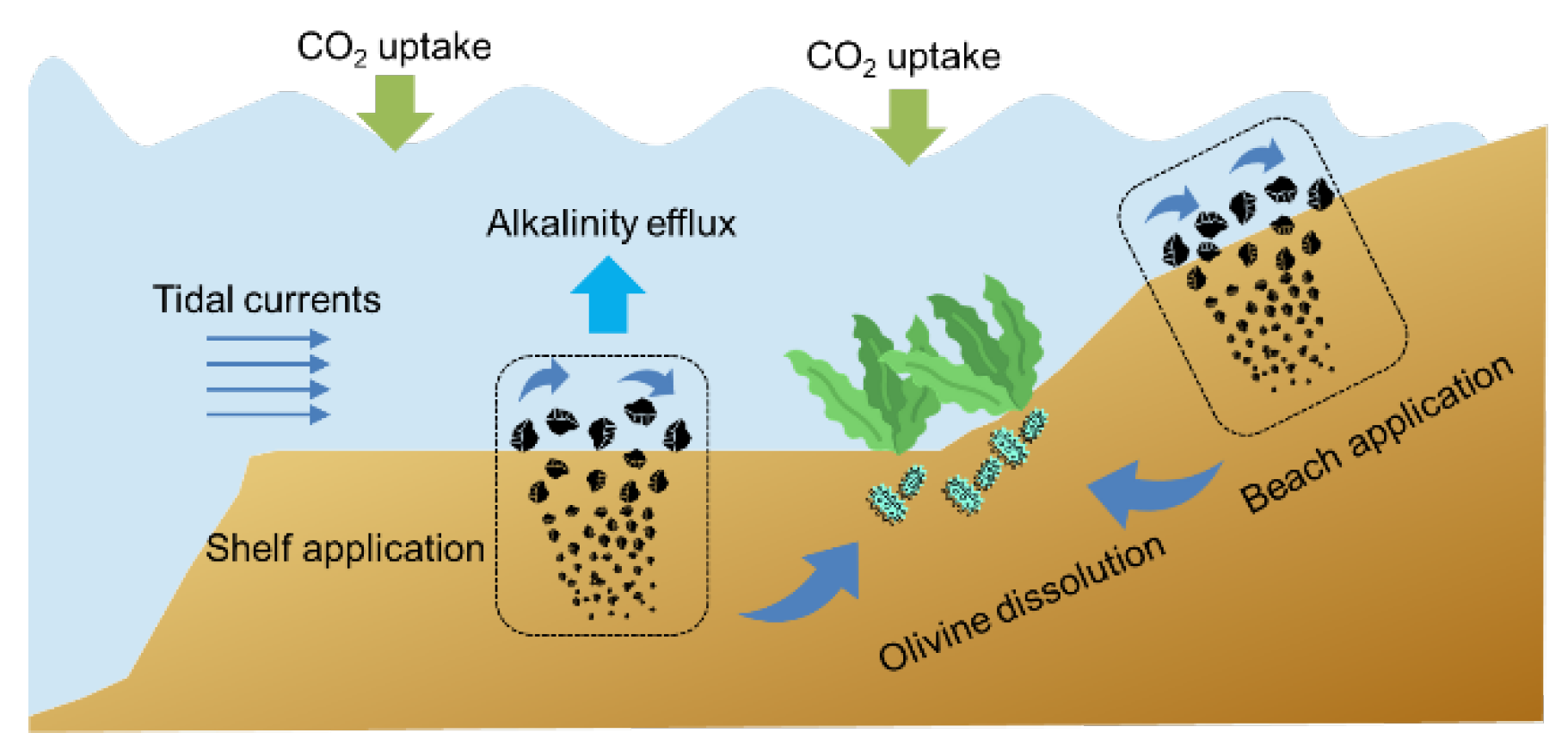

2.2.3. Ocean-Based Engineering Enhancement

3. Quantifying Natural and Anthropogenic Carbon Sinks

3.1. Overview of Carbon Sink Distributions in Natural and Anthropogenic Systems

3.2. Assessment of Terrestrial Ecosystem Carbon Sinks

3.2.1. Forest Ecosystems

3.2.2. Wetland Ecosystems

3.2.3. Cropland Ecosystems

3.2.4. Grassland Ecosystems

3.2.5. Desert Ecosystems

3.2.6. Urban Ecosystems

3.3. Assessment of Carbon Sequestration in Marine Ecosystems

3.3.1. Composition and Reservoir Structure of Marine Carbon Sinks

3.3.2. Evaluation of Ocean Carbon Sink Intensity at Global and Regional Scales

3.3.3. Evolutionary Trends and Future Potential of Ocean Carbon Sinks

3.3.4. Uncertainty in Ocean Carbon Sink Estimation and Comparative Assessment of Emerging Approaches

3.4. Anthropogenic Carbon Dioxide Removal

3.4.1. Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS)

3.4.2. Direct Air Capture and Carbon Storage (DACCS)

3.4.3. Enhanced Weathering & Mineral Carbonation

3.4.4. Biochar Sequestration

3.4.5. Carbon Mineralization & Building Materials

3.4.6. Ocean-Based Engineering Enhancement

3.4.7. Comparison and Synthesis of Artificial CDR Pathways

4. Strategic Governance of Multi-Pathway Carbon Sequestration

4.1. Integrated Deployment Strategy and Boundary Coordination of Multi-Pathway Carbon Sequestration

4.1.1. Pathway Dimension: Structural Differences and Synergistic Potential between Nature-Based and Engineered Carbon Sinks

4.1.2. Regional Dimension: Spatial Suitability and Geo-Resource Coupling in Carbon Sink Deployment

4.1.3. Temporal Dimension: Dynamic Evolution and Phased Deployment of Multimodal Carbon Sink Pathways

4.2. Systemic Evolution and Adaptive Deployment of Carbon Sink Pathways

4.3. The Integrated Platform Mechanism Linking Industry, Region and Carbon Removal Pathways

4.4. Deployment Bottlenecks and Scientific Gaps

4.5. Future Prospects and Strategic Pathways for Multi-Track Carbon Sequestration Deployment

5. Conclusion

Funding

Data Availability

Conflict of Interest

References

- Global CCS Institute, 2023. Global Status of CCS 2023, Global CCS Institute, Melbourne.

- Abdalqadir, M.; Hughes, D.; Gomari, S.R.; Rafiq, U. A state of the art of review on factors affecting the enhanced weathering in agricultural soil: strategies for carbon sequestration and climate mitigation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 19047–19070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.M.; Faure, H.; Faure-Denard, L.; McGlade, J.M.; Woodward, F.I. Increases in terrestrial carbon storage from the Last Glacial Maximum to the present. Nature 1990, 348, 711–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, S.; Moon, E.; Paz-Ferreiro, J.; Timms, W. Comparative analysis of biochar carbon stability methods and implications for carbon credits. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 914, 169607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adun, H.; Ampah, J.D.; Bamisile, O.; Ozsahin, D.U.; Staffell, I. Sustainability implications of different carbon dioxide removal technologies in the context of Europe's climate neutrality goal. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 47, 598–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S. Carbon removal – pathways, technologies and need. Baltic Carbon Forum. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ajtay, G.L.; Ketner, P.; Duvigneaud, P. Terrestrial primary production and phytomass. SCOPE Report 1979, 13, 129–181. [Google Scholar]

- Akhmieva, R.; Vagapova, A.; Gumaev, I.; Riccardo, V.; Petaja, T.; Kukhar, V. Assessing the Impact: Escalating Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Their Effects. E3S Web of Conferences. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sakkari, E.G.; Ragab, A.; Dagdougui, H.; Boffito, D.C.; Amazouz, M. Carbon capture, utilization and sequestration systems design and operation optimization: Assessment and perspectives of artificial intelligence opportunities. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 917, 170085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, R.M.; Peters, G.P. The Global Carbon Project’s fossil CO2 emissions dataset. (No Title). 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, S.C.; Robinson, A.K.; Rodríguez-Quiñones, F. Bacterial iron homeostasis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2003, 27, 215–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Baar, H.J.W.; Gerringa, L.J.A.; Laan, P.; Timmermans, K.R. Efficiency of carbon removal per added iron in ocean iron fertilization. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2008, 364, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, A.; Vaneeckhaute, C.; Iliuta, M.C. Potential and challenges of bioenergy with carbon capture and storage as a carbon-negative energy source: A review. Biomass- Bioenergy 2021, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, L.T.; Tamsitt, V.; Baldry, K.; McGee, J.; Laurenceau-Cornec, E.C.; Strzepek, R.F.; Xie, Y.; Boyd, P.W. Identifying the Most (Cost-)Efficient Regions for CO2 Removal With Iron Fertilization in the Southern Ocean. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2023, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.H.; Kanzaki, Y.; Lora, J.M.; Planavsky, N.; Reinhard, C.T.; Zhang, S. Impact of Climate on the Global Capacity for Enhanced Rock Weathering on Croplands. Earth's Futur. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamiere, L.; et al. A marginal abatement cost curve for greenhouse gases attenuation by additional carbon storage in french agricultural land. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, T.; Jia, G.; Xu, X. Weakening greenhouse gas sink of pristine wetlands under warming. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2023, 13, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barahimi, V.; Ho, M.; Croiset, E. From Lab to Fab: Development and Deployment of Direct Air Capture of CO2. Energies 2023, 16, 6385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchiesi, S. On whether vegetation could contribute to major climate change mitigation efforts: forestry for carbon credits or carbon credits for forestry? A multi-criteria decision support model for forest carbon offsets. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, S.; Mackey, K.R.M. Phytoplankton as Key Mediators of the Biological Carbon Pump: Their Responses to a Changing Climate. Sustainability 2018, 10, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Mackey, K.R.M. Phytoplankton as Key Mediators of the Biological Carbon Pump: Their Responses to a Changing Climate. Sustainability 2018, 10, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerling, D.J.; Leake, J.R.; Long, S.P.; Scholes, J.D.; Ton, J.; Nelson, P.N.; Bird, M.; Kantzas, E.; Taylor, L.L.; Sarkar, B.; et al. Farming with crops and rocks to address global climate, food and soil security. Nat. Plants 2018, 4, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerling, D.J.; Kantzas, E.P.; Lomas, M.R.; Wade, P.; Eufrasio, R.M.; Renforth, P.; Sarkar, B.; Andrews, M.G.; James, R.H.; Pearce, C.R.; et al. Potential for large-scale CO2 removal via enhanced rock weathering with croplands. Nature 2020, 583, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrenfeld, M.J.; O’Malley, R.T.; Siegel, D.A.; McClain, C.R.; Sarmiento, J.L.; Feldman, G.C.; Milligan, A.J.; Falkowski, P.G.; Letelier, R.M.; Boss, E.S. Climate-driven trends in contemporary ocean productivity. Nature 2006, 444, 752–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmonte, B.A.; Aviso, K.B.; Benjamin, M.F.D.; Tan, R.R. A fuzzy optimization model for planning integrated terrestrial carbon management networks. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2021, 24, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmonte, B.A.; Aviso, K.B.; Benjamin, M.F.D.; Tan, R.R. A fuzzy optimization model for planning integrated terrestrial carbon management networks. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2021, 24, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardino, A.F.; Mazzuco, A.C.A.; Costa, R.F.; Souza, F.; Owuor, M.A.; Nobrega, G.N.; Sanders, C.J.; Ferreira, T.O.; Kauffman, J.B. The inclusion of Amazon mangroves in Brazil’s REDD+ program. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berner, R.A.; Kothavala, Z. GEOCARB III: A revised model of atmospheric CO2 over Phanerozoic time. Am. J. Sci. 2001, 301, 182–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, S.; Yao, C.; Xiang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, L.; Fan, F.; Bai, J.; Wang, R. Study on the mechanism of biomass ash in carbonation of magnesium slag and its main mineral phases. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, T.S.; Mayer, L.M.; Amaral, J.H.F.; Arndt, S.; Galy, V.; Kemp, D.B.; Kuehl, S.A.; Murray, N.J.; Regnier, P. Anthropogenic impacts on mud and organic carbon cycling. Nat. Geosci. 2024, 17, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisotti, F.; Hoff, K.A.; Mathisen, A.; Hovland, J. Direct Air capture (DAC) deployment: A review of the industrial deployment. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2023, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blain, S.; Quéguiner, B.; Armand, L.; Belviso, S.; Bombled, B.; Bopp, L.; Bowie, A.; Brunet, C.; Brussaard, C.; Carlotti, F.; et al. Effect of natural iron fertilization on carbon sequestration in the Southern Ocean. Nature 2007, 446, 1070–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolan, N.; Hoang, S.A.; Beiyuan, J.; Gupta, S.; Hou, D.; Karakoti, A.; Joseph, S.; Jung, S.; Kim, K.-H.; Kirkham, M.; et al. Multifunctional applications of biochar beyond carbon storage. Int. Mater. Rev. 2021, 67, 150–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomgardner, M.M., 2018. CarbonCure links with Airgas for concrete. AMER CHEMICAL SOC 1155 16TH ST, NW, WASHINGTON, DC 20036 USA.

- Boyd, P.W.; Watson, A.J.; Law, C.S.; Abraham, E.R.; Trull, T.; Murdoch, R.; Bakker, D.C.E.; Bowie, A.R.; Buesseler, K.O.; Chang, H.; et al. A mesoscale phytoplankton bloom in the polar Southern Ocean stimulated by iron fertilization. Nature 2000, 407, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, P.V. The effect of silicate weathering on global temperature and atmospheric CO2. J. Geophys. Res. 1991, 96, 18101–18106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitburg, D.; Levin, L.A.; Oschlies, A.; Grégoire, M.; Chavez, F.P.; Conley, D.J.; Garçon, V.; Gilbert, D.; Gutiérrez, D.; Isensee, K.; et al. Declining oxygen in the global ocean and coastal waters. Science 2018, 359, eaam7240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broecker, W.S.; Takahashi, T.; Simpson, H.J.; Peng, T.-. .-H. Fate of Fossil Fuel Carbon Dioxide and the Global Carbon Budget. Science 1979, 206, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckingham, F.; Henderson, G. The enhanced weathering potential of a range of silicate and carbonate additions in a UK agricultural soil. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 907, 167701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buesseler, K.O.; Andrews, J.E.; Pike, S.M.; Charette, M.A.; Goldson, L.E.; Brzezinski, M.A.; Lance, V.P. Particle export during the Southern Ocean Iron Experiment (SOFeX). Limnol. Oceanogr. 2005, 50, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bufe, A.; Rugenstein, J.K.C.; Hovius, N. CO 2 drawdown from weathering is maximized at moderate erosion rates. Science 2024, 383, 1075–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, M.; Adjiman, C.S.; Bardow, A.; Anthony, E.J.; Boston, A.; Brown, S.; Fennell, P.S.; Fuss, S.; Galindo, A.; Hackett, L.A.; et al. Carbon capture and storage (CCS): the way forward. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 1062–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdige, D.J. Burial of terrestrial organic matter in marine sediments: A re-assessment. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2005, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, W. Governance of ocean-based carbon dioxide removal research under the United Nations convention on the law of the sea. Me. L. Rev. 2023, 75, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A.D.; Fatoyinbo, T.; Charles, S.P.; Bourgeau-Chavez, L.L.; Goes, J.; Gomes, H.; Halabisky, M.; Holmquist, J.; Lohrenz, S.; Mitchell, C.; et al. A review of carbon monitoring in wet carbon systems using remote sensing. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 025009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; Zhang, J.; Han, J.; Zhang, T.; Yang, S.; Wang, J.; Prodhan, F.A.; Yao, F. Projected Increases in Global Terrestrial Net Primary Productivity Loss Caused by Drought Under Climate Change. Earth's Futur. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Kikkawa, S.; Yamada, H.; Kawasoko, H.; Yamazoe, S. Low-Temperature Desorption of CO2 from Carbamic Acid for CO2 Condensation by Direct Air Capture. ACS omega 2024, 9, 40075–40081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, R.; Huang, G.; Chen, J.; Li, Y. A fractional multi-stage simulation-optimization energy model for carbon emission management of urban agglomeration. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- apková, K. and Řeháková, K., 2023. Microbial Architects of the Cold Deserts: A Comprehensive Research of Biological Soil Crusts in the High-Altitudinal Cold Deserts of the Western Himalayas, ARPHA Conference Abstracts. Pensoft Publishers, pp. e106961.

- Carvalhais, N.; Forkel, M.; Khomik, M.; Bellarby, J.; Jung, M.; Migliavacca, M.; Μu, M.; Saatchi, S.; Santoro, M.; Thurner, M.; et al. Global covariation of carbon turnover times with climate in terrestrial ecosystems. Nature 2014, 514, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalhais, N.; Forkel, M.; Khomik, M.; Bellarby, J.; Jung, M.; Migliavacca, M.; Μu, M.; Saatchi, S.; Santoro, M.; Thurner, M.; et al. Global covariation of carbon turnover times with climate in terrestrial ecosystems. Nature 2014, 514, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, N.; et al. Estimated regional CO 2 flux and uncertainty based on an ensemble of atmospheric CO 2 inversions. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2022, 22, 9215–9243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Ciais, P.; Gasser, T.; Smith, P.; Herrero, M.; Havlík, P.; Obersteiner, M.; Guenet, B.; Goll, D.S.; Li, W.; et al. Climate warming from managed grasslands cancels the cooling effect of carbon sinks in sparsely grazed and natural grasslands. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, S.; Matson, P.A.; Mooney, H.A.; Chapin, M.C. Principles of Terrestrial Ecosystem Ecology. Springer: New York, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, S.; Huang, K.-W. Unrealistic energy and materials requirement for direct air capture in deep mitigation pathways. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zang, R.; An, Y.; Yang, Y.; Fu, G.; Xu, Z.; Wu, D.; Liu, Y. Spatio-Temporal Disparity of Ecosystem Carbon Sequestration Capacity in the Region of Chengde, China. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2024, 34, 6121–6132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Hu, C.; Barnes, B.B.; Wanninkhof, R.; Cai, W.-J.; Barbero, L.; Pierrot, D. A machine learning approach to estimate surface ocean pCO2 from satellite measurements. Remote. Sens. Environ. 2019, 228, 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiquier, S.; Gurgel, A.; Morris, J.; Chen, Y.-H.H.; Paltsev, S. Integrated assessment of carbon dioxide removal portfolios: land, energy, and economic trade-offs for climate policy. Environ. Res. Lett. 2025, 20, 024002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiquier, S.; Gurgel, A.; Morris, J.; Chen, Y.-H.H.; Paltsev, S. Integrated assessment of carbon dioxide removal portfolios: land, energy, and economic trade-offs for climate policy. Environ. Res. Lett. 2025, 20, 024002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiquier, S.; Patrizio, P.; Bui, M.; Sunny, N.; Mac Dowell, N. A comparative analysis of the efficiency, timing, and permanence of CO2 removal pathways. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 4389–4403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiquier, S.; Patrizio, P.; Bui, M.; Sunny, N.; Mac Dowell, N. A comparative analysis of the efficiency, timing, and permanence of CO2 removal pathways. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 4389–4403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiquier, S.; Patrizio, P.; Bui, M.; Sunny, N.; Mac Dowell, N. A comparative analysis of the efficiency, timing, and permanence of CO2 removal pathways. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 4389–4403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christenson, N.; Walters, J. SkyMine Carbon Mineralization Pilot Project. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Churkina, G. Modeling the carbon cycle of urban systems. Ecol. Model. 2008, 216, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churkina, G. The Role of Urbanization in the Global Carbon Cycle. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2016, 3, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churkina, G.; Brown, D.G.; Keoleian, G. Carbon stored in human settlements: the conterminous United States. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2009, 16, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.E.; Oelkers, E.H.; Gunnarsson, I.; Sigfússon, B.; Snæbjörnsdóttir, S.Ó.; Aradóttir, E.S.; Gíslason, S.R. CarbFix2: CO2 and H2S mineralization during 3.5 years of continuous injection into basaltic rocks at more than 250 °C. Geochim. et Cosmochim. Acta 2020, 279, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coale, K.H.; Johnson, K.S.; Fitzwater, S.E.; Gordon, R.M.; Tanner, S.; Chavez, F.P.; Ferioli, L.; Sakamoto, C.; Rogers, P.; Millero, F.; et al. A massive phytoplankton bloom induced by an ecosystem-scale iron fertilization experiment in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. Nature 1996, 383, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.; Shi, Y.; Yang, Z.; Song, X.; Peng, J.; Liu, Q.; Fan, M.; Wang, L. An integrated system of CO2 geological sequestration and aquifer thermal energy storage: Storage characteristics and applicability analysis. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, J.J.; Boyd, P.W. Predicting and verifying the intended and unintended consequences of large-scale ocean iron fertilization. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2008, 364, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, A.W.; Geilert, S.; Diercks, I.; Fuhr, M.; Perner, M.; Scholz, F.; Wallmann, K. Seafloor alkalinity enhancement as a carbon dioxide removal strategy in the Baltic Sea. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davin, É.L. Land–climate interactions. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- de Coninck, H.; Benson, S.M. Carbon dioxide capture and storage: issues and prospects. Annual review of environment and resources 2014, 39, 243–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Coninck, H.; Benson, S.M. Carbon dioxide capture and storage; issues and prospects. Annual review of environment and resources 2014, 39, 243–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lavergne, C.; Palter, J.B.; Galbraith, E.D.; Bernardello, R.; Marinov, I. Cessation of deep convection in the open Southern Ocean under anthropogenic climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2014, 4, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Teng, F.; Zhang, X.; Fan, J.-L.; Forsell, N.; Reiner, D.M. Co-deploying biochar and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage improves cost-effectiveness and sustainability of China’s carbon neutrality. One Earth 2025, 8, 101172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVries, T.; Holzer, M.; Primeau, F. Recent increase in oceanic carbon uptake driven by weaker upper-ocean overturning. Nature 2017, 542, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVries, T.; Holzer, M.; Primeau, F. Recent increase in oceanic carbon uptake driven by weaker upper-ocean overturning. Nature 2017, 542, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVries, T.; Holzer, M.; Primeau, F. Recent increase in oceanic carbon uptake driven by weaker upper-ocean overturning. Nature 2017, 542, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinc, M.; Vatandaslar, C. ANALYZING CARBON STOCKS IN A MEDITERRANEAN FOREST ENTERPRISE: A CASE STUDY FROM KIZILDAG, TURKEY. CERNE 2019, 25, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinca, C.; Slavu, N.; Cormoş, C.-C.; Badea, A. CO2 capture from syngas generated by a biomass gasification power plant with chemical absorption process. Energy 2018, 149, 925–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, R.K.; Solomon, A.M.; Brown, S.; Houghton, R.A.; Trexier, M.C.; Wisniewski, J. Carbon Pools and Flux of Global Forest Ecosystems. Science 1994, 263, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, D.C.; Kauffman, J.B.; Murdiyarso, D.; Kurnianto, S.; Stidham, M.; Kanninen, M. Mangroves among the most carbon-rich forests in the tropics. Nat. Geosci. 2011, 4, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doney, S.C., Fabry, V.J., Feely, R.A. and Kleypas, J.A., 2009. Ocean Acidification: The Other CO2 Problem. Annual Review of Marine Science, 1(Volume 1, 2009): 169-192.

- Dong, L.; Wang, Y.; Ai, L.; Cheng, X.; Luo, Y. A review of research methods for accounting urban green space carbon sinks and exploration of new approaches. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1350185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnison, C.; Holland, R.A.; Hastings, A.; Armstrong, L.; Eigenbrod, F.; Taylor, G. Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS): Finding the win–wins for energy, negative emissions and ecosystem services—size matters. GCB Bioenergy 2020, 12, 586–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnison, C., Holland, R., Harris, Z., Eigenbrod, F. and Taylor, G., 2021. Improved biodiversity from food to energy: Meta-analysis of land-use change to dedicated bioenergy crops, EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts, pp. EGU21-6737.

- Doughty, C.E.; Keany, J.M.; Wiebe, B.C.; Rey-Sanchez, C.; Carter, K.R.; Middleby, K.B.; Cheesman, A.W.; Goulden, M.L.; da Rocha, H.R.; Miller, S.D.; et al. Tropical forests are approaching critical temperature thresholds. Nature 2023, 621, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, A.W.; Conant, R.T.; Marston, L.T.; Choi, E.; Mueller, N.D. Greenhouse gas emissions from US irrigation pumping and implications for climate-smart irrigation policy. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, C.M.; Losada, I.J.; Hendriks, I.E.; Mazarrasa, I.; Marbà, N. The role of coastal plant communities for climate change mitigation and adaptation. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2013, 3, 961–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, C.M.; Losada, I.J.; Hendriks, I.E.; Mazarrasa, I.; Marbà, N. The role of coastal plant communities for climate change mitigation and adaptation. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2013, 3, 961–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, J.P. Physical Mechanisms Driving Enhanced Carbon Sequestration by the Biological Pump Under Climate Warming. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2023, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emenike, O.; Michailos, S.; Finney, K.N.; Hughes, K.J.; Ingham, D.; Pourkashanian, M. Initial techno-economic screening of BECCS technologies in power generation for a range of biomass feedstock. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assessments 2020, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, D.; Sofen, L.E.; Michaud, A.B.; Archer, S.D.; Twining, B.S. A Cost Model for Ocean Iron Fertilization as a Means of Carbon Dioxide Removal That Compares Ship- and Aerial-Based Delivery, and Estimates Verification Costs. Earth's Futur. 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esper, J.; Torbenson, M.; Büntgen, U. 2023 summer warmth unparalleled over the past 2,000 years. Nature 2024, 631, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, H.; Fan, L.; Ciais, P.; Xiao, J.; Fensholt, R.; Chen, J.; Frappart, F.; Ju, W.; Niu, S.; Xiao, X.; et al. Satellite-based monitoring of China's above-ground biomass carbon sink from 2015 to 2021. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2024, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Yu, G.; Liu, L.; Hu, S.; Chapin, F.S., III. Climate change, human impacts, and carbon sequestration in China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 4015–4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Yu, G.; Liu, L.; Hu, S.; Chapin, F.S., III. Climate change, human impacts, and carbon sequestration in China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 4015–4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatichi, S.; Leuzinger, S.; Körner, C. Moving beyond photosynthesis: from carbon source to sink-driven vegetation modeling. New Phytol. 2013, 201, 1086–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatichi, S.; Pappas, C.; Zscheischler, J.; Leuzinger, S. Modelling carbon sources and sinks in terrestrial vegetation. New Phytol. 2018, 221, 652–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawzy, S.; Osman, A.I.; Yang, H.; Doran, J.; Rooney, D.W. Industrial biochar systems for atmospheric carbon removal: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 3023–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fay, A.R.; McKinley, G.A. Global open-ocean biomes: mean and temporal variability. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2014, 6, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Lauvaux, T.; Keller, K.; Davis, K.J.; Rayner, P.; Oda, T.; Gurney, K.R. A Road Map for Improving the Treatment of Uncertainties in High-Resolution Regional Carbon Flux Inverse Estimates. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 13461–13469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finley, R.J. An overview of the Illinois Basin–Decatur project. Greenhouse Gases: Science and Technology 2014, 4, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follingstad, G. Tipping Points for a Seminal New Era of Climate Resilience and Climate Justice. J. Clim. Resil. Justice 2023, 1, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridahl, M.; Bellamy, R.; Hansson, A.; Haikola, S. Mapping Multi-Level Policy Incentives for Bioenergy With Carbon Capture and Storage in Sweden. Front. Clim. 2020, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlingstein, P.; et al. Global Carbon Budget 2020. Earth System Science Data 2020, 12, 3269–3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlingstein, P.; et al. Global carbon budget 2022. Earth system science data 2022, 14, 4811–4900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlingstein, P.; et al. Global Carbon Budget 2023. Earth System Science Data 2023, 15, 5301–5369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlingstein, P.; et al. Global carbon budget 2024. Earth System Science Data Discussions 2024, 2024, 1–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhrman, J.; Clarens, A.; Calvin, K.V.; Doney, S.C.; A Edmonds, J.; O’rOurke, P.; Patel, P.L.; Pradhan, S.; Shobe, W.; McJeon, H.C. The role of direct air capture and negative emissions technologies in the shared socioeconomic pathways towards +1.5 °C and +2 °C futures. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 114012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, I., 1993. Models of oceanic and terrestrial sinks of anthropogenic CO2: A review of the contemporary carbon cycle, Biogeochemistry of Global Change: Radiatively Active Trace Gases Selected Papers from the Tenth International Symposium on Environmental Biogeochemistry, San Francisco, August 19–24, 1991. Springer, pp. 166-189.

- Fuss, S.; Lamb, W.F.; Callaghan, M.W.; Hilaire, J.; Creutzig, F.; Amann, T.; Beringer, T.; Garcia, W.d.O.; Hartmann, J.; Khanna, T.; et al. Negative emissions—Part 2: Costs, potentials and side effects. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 063002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán-Martín, Á.; Vázquez, D.; Cobo, S.; Mac Dowell, N.; Caballero, J.A.; Guillén-Gosálbez, G. Delaying carbon dioxide removal in the European Union puts climate targets at risk. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galina, N.R.; Arce, G.L.A.F.; Maroto-Valer, M.; Ávila, I. Experimental Study on Mineral Dissolution and Carbonation Efficiency Applied to pH-Swing Mineral Carbonation for Improved CO2 Sequestration. Energies 2023, 16, 2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganeshan, P.; S, V.V.; Gowd, S.C.; Mishra, R.; Singh, E.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, S.; Pugazhendhi, A.; Rajendran, K. Bioenergy with carbon capture, storage and utilization: Potential technologies to mitigate climate change. Biomass- Bioenergy 2023, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garza, D.; Dargusch, P.; Wadley, D. A Technological Review of Direct Air Carbon Capture and Storage (DACCS): Global Standing and Potential Application in Australia. Energies 2023, 16, 4090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerts, L.J.J.; Hylén, A.; Meysman, F.J.R. Review and syntheses: Ocean alkalinity enhancement and carbon dioxide removal through marine enhanced rock weathering using olivine. Biogeosciences 2025, 22, 355–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghodake, G.S.; Shinde, S.K.; Kadam, A.A.; Saratale, R.G.; Saratale, G.D.; Kumar, M.; Palem, R.R.; Al-Shwaiman, H.A.; Elgorban, A.M.; Syed, A.; et al. Review on biomass feedstocks, pyrolysis mechanism and physicochemical properties of biochar: State-of-the-art framework to speed up vision of circular bioeconomy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gíslason, S.R.; Sigurdardóttir, H.; Aradóttir, E.S.; Oelkers, E.H. A brief history of CarbFix: Challenges and victories of the project’s pilot phase. Energy Procedia 2018, 146, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Soil Data Task, 2014. Global Soil Data Products CD-ROM Contents (IGBP-DIS). ORNL Distributed Active Archive Center.

- Gloege, L.; McKinley, G.A.; Landschützer, P.; Fay, A.R.; Frölicher, T.L.; Fyfe, J.C.; Ilyina, T.; Jones, S.; Lovenduski, N.S.; Rödenbeck, C.; et al. Quantifying Errors in Observationally Based Estimates of Ocean Carbon Sink Variability. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2021, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D.S.; Nawaz, S.; Lavin, J.; Slagle, A.L. Upscaling DAC Hubs with Wind Energy and CO2 Mineral Storage: Considerations for Large-Scale Carbon Removal from the Atmosphere. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 21527–21534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooya, P.; Swart, N.C.; Hamme, R.C. Time-varying changes and uncertainties in the CMIP6 ocean carbon sink from global to local scale. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2023, 14, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, C.; Garcia-Freites, S.; Jones, C.; Mander, S.; Moore, B.; Pereira, C.; Röder, M.; Vaughan, N.; Welfle, A. Challenges to the use of BECCS as a keystone technology in pursuit of 1.5⁰C. Glob. Sustain. 2018, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, C.; Mander, S. Beyond Social Acceptability: Applying Lessons from CCS Social Science to Support Deployment of BECCS. Curr. Sustain. Energy Rep. 2019, 6, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.K.; Keenan, T.F. The limits of forest carbon sequestration. Science 2022, 376, 692–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griscom, B.W.; et al. Natural climate solutions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114, 11645–11650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruber, N.; et al. The Oceanic Sink for Anthropogenic CO2. Science 2019, 305, 367–371. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, N.; Bakker, D.C.E.; DeVries, T.; Gregor, L.; Hauck, J.; Landschützer, P.; McKinley, G.A.; Müller, J.D. Trends and variability in the ocean carbon sink. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, N.; Landschützer, P.; Lovenduski, N.S. The Variable Southern Ocean Carbon Sink. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2019, 11, 159–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, P.; Ekardt, F. Human Rights and Large-Scale Carbon Dioxide Removal: Potential Limits to BECCS and DACCS Deployment. Land 2022, 11, 2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güssow, K.; Proelss, A.; Oschlies, A.; Rehdanz, K.; Rickels, W. Ocean iron fertilization: Why further research is needed. Mar. Policy 2010, 34, 911–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutsch, M.; Leker, J. Co-assessment of costs and environmental impacts for off-grid direct air carbon capture and storage systems. Commun. Eng. 2024, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halloran, P.R.; Bell, T.G.; Burt, W.J.; Chu, S.N.; Gill, S.; Henderson, C.; Ho, D.T.; Kitidis, V.; La Plante, E.; Larrazabal, M.; et al. Seawater carbonate chemistry based carbon dioxide removal: towards commonly agreed principles for carbon monitoring, reporting, and verification. Front. Clim. 2025, 7, 1487138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hangx, S.J.; Spiers, C.J. Coastal spreading of olivine to control atmospheric CO2 concentrations: A critical analysis of viability. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2009, 3, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansell, D.A.; Carlson, C.A.; Repeta, D.J.; Schlitzer, R. Dissolved Organic Matter in the Ocean: A Controversy Stimulates New Insights. Oceanography 2009, 22, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, F.; Chiang, Y.W.; Santos, R.M. Risk assessment of Ni, Cr, and Si release from alkaline minerals during enhanced weathering. Open Agric. 2020, 5, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, K.G. Role of increased marine silica input on paleo-pCO2 levels. Paleoceanography 2000, 15, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, J.; West, A.J.; Renforth, P.; Köhler, P.; De La Rocha, C.L.; Wolf-Gladrow, D.A.; Dürr, H.H.; Scheffran, J. Enhanced chemical weathering as a geoengineering strategy to reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide, supply nutrients, and mitigate ocean acidification. Rev. Geophys. 2013, 51, 113–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, J.; Suitner, N.; Lim, C.; Schneider, J.; Marín-Samper, L.; Arístegui, J.; Renforth, P.; Taucher, J.; Riebesell, U. Stability of alkalinity in ocean alkalinity enhancement (OAE) approaches – consequences for durability of CO2 storage. Biogeosciences 2023, 20, 781–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasler, N.; Williams, C.A.; Denney, V.C.; Ellis, P.W.; Shrestha, S.; Hart, D.E.T.; Wolff, N.H.; Yeo, S.; Crowther, T.W.; Werden, L.K.; et al. Accounting for albedo change to identify climate-positive tree cover restoration. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauck, J.; Gregor, L.; Nissen, C.; Patara, L.; Hague, M.; Mongwe, P.; Bushinsky, S.; Doney, S.C.; Gruber, N.; Le Quéré, C.; et al. The Southern Ocean Carbon Cycle 1985–2018: Mean, Seasonal Cycle, Trends, and Storage. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2023, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauck, J.; Köhler, P.; Wolf-Gladrow, D.; Völker, C. Iron fertilisation and century-scale effects of open ocean dissolution of olivine in a simulated CO 2 removal experiment. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 024007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Guo, F.; Li, L.; Ding, R. Coupling relationship and development patterns of agricultural emission reduction, carbon sequestration, and food security. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 955, 176810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinze, C.; et al. The quiet crossing of ocean tipping points. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118, e2008478118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henson, S.A.; Sanders, R.; Madsen, E. Global patterns in efficiency of particulate organic carbon export and transfer to the deep ocean. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2012, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepburn, C.; Adlen, E.; Beddington, J.; Carter, E.A.; Fuss, S.; Mac Dowell, N.; Minx, J.C.; Smith, P.; Williams, C.K. The technological and economic prospects for CO2 utilization and removal. Nature 2019, 575, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heřmanská, M.; Voigt, M.J.; Marieni, C.; Declercq, J.; Oelkers, E.H. A comprehensive and consistent mineral dissolution rate database: Part II: Secondary silicate minerals. Chem. Geol. 2023, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirt, H.; Boukcim, H.; Ducousso, M.; Saad, M.M. Engineering carbon sequestration on arid lands. Trends Plant Sci. 2023, 28, 1218–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, H.; Iizuka, A. A Comparative Study of Mineral Carbonation Using Seawater for CO2 Utilization: Magnesium-Based System Versus Calcium-Based System with Low Energy Input. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2025, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, F.; Davies, K.; Beerling, D.; Hume, R.; Bird, M.; Nelson, P. In-field carbon dioxide removal via weathering of crushed basalt applied to acidic tropical agricultural soil. The Science of the total environment 2024, 176568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornbostel, K.; et al. Core-Shell Metal-Organic-Frameworks for Direct Air Capture. Proceedings of the 16th Greenhouse Gas Control Technologies Conference (GHGT-16) 2022, 23–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, R.A.; Hackler, J.L. Sources and sinks of carbon from land-use change in China. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2003, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, R.A.; Nassikas, A.A. Global and regional fluxes of carbon from land use and land cover change 1850–2015. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2017, 31, 456–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, L.; Ren, H.; Liu, J. Potential of CO2 sequestration by olivine addition in offshore waters: A ship-based deck incubation experiment. Mar. Environ. Res. 2024, 201, 106708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X., 2016. Research progress on coupling relationship between carbon and water of ecosystem in arid area, International Conference on Geo-Informatics in Resource Management and Sustainable Ecosystems. Springer, pp. 456-465.

- Huang, X.; Chen, X.; Guo, Y.; Wang, H. Study on Utilization of Biochar Prepared from Crop Straw with Enhanced Carbon Sink Function in Northeast China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, N. How does the carbon market influence the marginal abatement cost? Evidence from China's coal-fired power plants. Appl. Energy 2024, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Gao, G.; Ran, L.; Wang, Y.; Fu, B. Afforestation Reduces Deep Soil Carbon Sequestration in Semiarid Regions: Lessons From Variations of Soil Water and Carbon Along Afforestation Stages in China's Loess Plateau. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 2024, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency, 2024. World Energy Outlook 2024, International Energy Agency, Paris.

- IPCC. Climate change 2022: Mitigation of climate change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom; New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ishaq, H.; Foxall, R.; Crawford, C. Performance assessment of offshore wind energy integrated monoethanolamine synthesis system for post-combustion and potential direct air capture. J. CO2 Util. 2022, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadi, P.; O’rOurke, P.; Fuhrman, J.; McJeon, H.; Doney, S.C.; Shobe, W.; Clarens, A.F. The impact of regional resources and technology availability on carbon dioxide removal potential in the United States. Environ. Res. Energy 2024, 1, 045007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.; Shin, H.C.; Yun, T.K.; Han, W.S.; Jeong, J.; Gwag, J. A Comprehensive Review of Geological CO2 Sequestration in Basalt Formations. Econ. Environ. Geol. 2023, 56, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerden, J.; Mejbel, M.; Filho, A.N.Z.; Carroll, M.; Campe, J. The impact of geochemical and life-cycle variables on carbon dioxide removal by enhanced rock weathering: Development and application of the Stella ERW model. Appl. Geochem. 2024, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeswani, H.K.; Saharudin, D.M.; Azapagic, A. Environmental sustainability of negative emissions technologies: A review. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 33, 608–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.-B.; Hutchins, D.A.; Zhang, H.-R.; Feng, Y.-Y.; Zhang, R.-F.; Sun, W.-W.; Ma, W.; Bai, Y.; Wells, M.; He, D.; et al. Complexities of regulating climate by promoting marine primary production with ocean iron fertilization. Earth-Science Rev. 2024, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.-B.; Hutchins, D.A.; Zhang, H.-R.; Feng, Y.-Y.; Zhang, R.-F.; Sun, W.-W.; Ma, W.; Bai, Y.; Wells, M.; He, D.; et al. Complexities of regulating climate by promoting marine primary production with ocean iron fertilization. Earth-Science Rev. 2024, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.-Q.; Carter, B.R.; Feely, R.A.; Lauvset, S.K.; Olsen, A. Surface ocean pH and buffer capacity: past, present and future. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, N.; Herndl, G.J.; Hansell, D.A.; Benner, R.; Kattner, G.; Wilhelm, S.W.; Kirchman, D.L.; Weinbauer, M.G.; Luo, T.; Chen, F.; et al. Microbial production of recalcitrant dissolved organic matter: long-term carbon storage in the global ocean. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, N.; Liu, J.; Jiao, F.; Chen, Q.; Wang, X. Microbes mediated comprehensive carbon sequestration for negative emissions in the ocean. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2020, 7, 1858–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobbagy, E.G.; Jackson, R.B. The Vertical Distribution of Soil Organic Carbon and Its Relation to Climate and Vegetation. Ecological Applications 2000, 10, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.S.; Plant, J.N.; Coletti, L.J.; Jannasch, H.W.; Sakamoto, C.M.; Riser, S.C.; Swift, D.D.; Williams, N.L.; Boss, E.; Haëntjens, N.; et al. Biogeochemical sensor performance in the SOCCOM profiling float array. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2017, 122, 6416–6436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.S.; Bif, M.B. Constraint on net primary productivity of the global ocean by Argo oxygen measurements. Nat. Geosci. 2021, 14, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.R.; Olfe-Kräutlein, B.; Naims, H.; Armstrong, K. The Social Acceptance of Carbon Dioxide Utilisation: A Review and Research Agenda. Front. Energy Res. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M. Can biomass supply meet the demands of BECCS? 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, H.-C.; Moon, B.-K.; Lee, H.; Choi, J.-H.; Kim, H.-K.; Park, J.-Y.; Byun, Y.-H.; Lim, Y.-J.; Lee, J. Development and Assessment of NEMO(v3.6)-TOPAZ(v2), a Coupled Global Ocean Biogeochemistry Model. Asia-Pacific J. Atmospheric Sci. 2019, 56, 411–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jürchott, M.; Koeve, W.; Oschlies, A. The response of the ocean carbon cycle to artificial upwelling, ocean iron fertilization and the combination of both. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 114088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaipov, Y.; Theuveny, B.; Maurya, A.; Alawagi, A. CO2 Injectivity Test Proves the Concept of CCUS Field Development. ADIPEC. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kämäräinen, M., 2022. Comment on bg-2022-108 Anonymous Referee # 1 Referee comment on " Evaluation of gradient boosting and random forest methods to model subdaily variability of the atmosphere – forest CO 2 exchange.

- Kantzas, E.P.; Martin, M.V.; Lomas, M.R.; Eufrasio, R.M.; Renforth, P.; Lewis, A.L.; Taylor, L.L.; Mecure, J.-F.; Pollitt, H.; Vercoulen, P.V.; et al. Substantial carbon drawdown potential from enhanced rock weathering in the United Kingdom. Nat. Geosci. 2022, 15, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karan, S.K.; Woolf, D.; Azzi, E.S.; Sundberg, C.; Wood, S.A. Potential for biochar carbon sequestration from crop residues: A global spatially explicit assessment. GCB Bioenergy 2023, 15, 1424–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karstens, K.; Bodirsky, B.L.; Dietrich, J.P.; Dondini, M.; Heinke, J.; Kuhnert, M.; Müller, C.; Rolinski, S.; Smith, P.; Weindl, I.; et al. Management-induced changes in soil organic carbon on global croplands. Biogeosciences 2022, 19, 5125–5149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattsov et al., 2001. Contribution of Working Group 1 to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- Keenan, T.F.; Williams, C.A. The Terrestrial Carbon Sink. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 2018, 43, 219–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keerthi, M.M. Innovative Approaches To Carbon Sequestration Emerging Technologies And Global Impacts On Climate Change Mitigation. Environ. Rep. 2024, 6, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelemen, P.; Benson, S.M.; Pilorgé, H.; Psarras, P.; Wilcox, J. An Overview of the Status and Challenges of CO2 Storage in Minerals and Geological Formations. Front. Clim. 2019, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelemen, P.B.; Matter, J.; Streit, E.E.; Rudge, J.F.; Curry, W.B.; Blusztajn, J. Rates and Mechanisms of Mineral Carbonation in Peridotite: Natural Processes and Recipes for Enhanced, in situ CO2 Capture and Storage. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2011, 39, 545–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelemen, P.B.; McQueen, N.; Wilcox, J.; Renforth, P.; Dipple, G.; Vankeuren, A.P. Engineered carbon mineralization in ultramafic rocks for CO2 removal from air: Review and new insights. Chem. Geol. 2020, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemper, J. Biomass and carbon dioxide capture and storage: A review. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2015, 40, 401–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatiwala, S.; Primeau, F.; Hall, T. Reconstruction of the history of anthropogenic CO2 concentrations in the ocean. Nature 2009, 462, 346–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatiwala, S.; Schmittner, A.; Muglia, J. Air-sea disequilibrium enhances ocean carbon storage during glacial periods. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaaw4981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kheshgi, H.S. Sequestering atmospheric carbon dioxide by increasing ocean alkalinity. Energy 1995, 20, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibret, H.A., Ramayya, A.V. and Abunie, B.B., 2016. DESIGN , FABRICATİON AND SENSITVTY TESTING OF AN EFFICIENT BONE PYROLYSİS KILN AND BIOCHAR BASED INDIGENOUS FERTILIZER PELLETIZING MACHINE FOR LINKING RENEWABLE ENERGY WITH CLIMATE SMART AGRICULTURE.

- Kim, S.T.; Conklin, S.D.; Redan, B.W.; Ho, K.K.H.Y. Determination of the Nutrient and Toxic Element Content of Wild-Collected and Cultivated Seaweeds from Hawai‘i. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 4, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, W.J.; Stevenson, E.I.; Renforth, P.; Ascough, P.L.; Knight, A.C.G.; Bridgestock, L.; Bickle, M.J.; Lin, Y.; Riley, A.L.; Mayes, W.M.; et al. Quantifying CO2 Removal at Enhanced Weathering Sites: a Multiproxy Approach. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 9854–9864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komma, R.B.; Dillon, G.P. Development and Characterization of Polyethylenimine-Infiltrated Mesoporous Silica Foam Pellets for CO2 Capture. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 32881–32892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konovalov, I.B.; Golovushkin, N.A.; Mareev, E.A. Using OCO-2 Observations to Constrain Regional CO2 Fluxes Estimated with the Vegetation, Photosynthesis and Respiration Model. Remote Sensing 2025, 17, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotz, M.; Levermann, A.; Wenz, L. The economic commitment of climate change. Nature 2024, 628, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Chung, W.J.; Khan, M.A.; Son, M.; Park, Y.-K.; Lee, S.S.; Jeon, B.-H. Breakthrough innovations in carbon dioxide mineralization for a sustainable future. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technology 2024, 23, 739–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, E.Y.; Dunne, J.P.; Lee, K. Biological export production controls upper ocean calcium carbonate dissolution and CO 2 buffer capacity. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadl0779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird, D.; et al. The Pyrolysis-Bioenergy-Biochar Pathway to Carbon-Negative Energy. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Landschützer, P.; Gruber, N.; Bakker, D.C.E. Decadal variations and trends of the global ocean carbon sink. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2016, 30, 1396–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Quéré, C.; Raupach, M.R.; Canadell, J.G.; Marland, G.; Bopp, L.; Ciais, P.; Conway, T.J.; Doney, S.C.; Feely, R.A.; Foster, P.; et al. Trends in the sources and sinks of carbon dioxide. Nat. Geosci. 2009, 2, 831–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebling, K.; Riedl, D.; Leslie-Bole, H. Measurement, Reporting, and Verification for Novel Carbon Dioxide Removal in US Federal Policy. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.A., Jiang, H., Dasgupta, R. and Torres, M., 2019. A Framework for Understanding Whole-Earth Carbon Cycling. Cambridge University Press, United Kingdom, pp. 313-357.

- Lee, J.W.; Ahn, H.; Kim, S.; Kang, Y.T. Low-concentration CO2 capture system with liquid-like adsorbent based on monoethanolamine for low energy consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefvert, A.; Grönkvist, S. Lost in the scenarios of negative emissions: The role of bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS). Energy Policy 2023, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, L.; Rivkin, R.B.; Weinbauer, M.G.; Guidi, L.; Uitz, J. The microbial carbon pump concept: Potential biogeochemical significance in the globally changing ocean. Prog. Oceanogr. 2015, 134, 432–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtveer, M.; Emanuelsson, A. BECCS and DACCS as Negative Emission Providers in an Intermittent Electricity System: Why Levelized Cost of Carbon May Be a Misleading Measure for Policy Decisions. Front. Clim. 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtveer, M.; Emanuelsson, A. BECCS and DACCS as Negative Emission Providers in an Intermittent Electricity System: Why Levelized Cost of Carbon May Be a Misleading Measure for Policy Decisions. Front. Clim. 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leifeld, J.; Menichetti, L. The underappreciated potential of peatlands in global climate change mitigation strategies. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Guo, X.; Hutchins, D.A.; Ma, J.; Lin, X.; Dai, M. The interactions between olivine dissolution and phytoplankton in seawater: Potential implications for ocean alkalinization. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 912, 168571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.-W.; Huang, J.-L.; Yu, D.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, X.-L. Development of low-carbon technologies in China's integrated hydrogen supply and power system. Adv. Clim. Chang. Res. 2024, 15, 936–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wang, Z.-H.; Wang, C. The potential of urban irrigation for counteracting carbon-climate feedback. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Houghton, R.A.; Tang, L. Hidden carbon sink beneath desert. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42, 5880–5887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Houghton, R.A.; Tang, L. Hidden carbon sink beneath desert. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42, 5880–5887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, R.; Zhang, X.; Xu, L.; Zhu, C. Understanding drivers of the spatial variability of soil organic carbon in China's terrestrial ecosystems. Land Degrad. Dev. 2023, 35, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; England, M.H.; Groeskamp, S. Recent acceleration in global ocean heat accumulation by mode and intermediate waters. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Planavsky, N.J.; Reinhard, C.T. Geospatial assessment of the cost and energy demand of feedstock grinding for enhanced rock weathering in the coterminous United States. Front. Clim. 2024, 6, 1380651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Zhang, W.; Jin, Z.; Yan, J.; Lü, Y.; Wang, S.; Fu, B.; Li, S.; Ji, Q.; Gou, F.; et al. Estimation of Global Grassland Net Ecosystem Carbon Exchange Using a Model Tree Ensemble Approach. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 2020, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wang, T.; Zheng, C.; Gao, X. Technical Perspective of Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage. Engineering 2022, 14, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linke, T.; Oelkers, E.; Dideriksen, K.; Möckel, S.; Nilabh, S.; Grandia, F.; Gislason, S. The geochemical evolution of basalt Enhanced Rock Weathering systems quantified from a natural analogue. Geochim. et Cosmochim. Acta 2024, 370, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liu, G.; Casazza, M.; Yan, N.; Xu, L.; Hao, Y.; Franzese, P.P.; Yang, Z. Current Status and Potential Assessment of China’s Ocean Carbon Sinks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 6584–6595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liu, G.; Casazza, M.; Yan, N.; Xu, L.; Hao, Y.; Franzese, P.P.; Yang, Z. Current Status and Potential Assessment of China’s Ocean Carbon Sinks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 6584–6595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Hu, M.; Huang, W.; Chen, C.X.; Li, J. Future Carbon Sequestration and Timber Yields from Chinese Commercial Forests under Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. Forests 2023, 14, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Song, F. Marginal Abatement Cost of Carbon Emissions under Different Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Song, F. Marginal Abatement Cost of Carbon Emissions under Different Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.S.; Song, J.M.; Li, X.G.; Yuan, H.M.; Duan, L.Q.; Li, S.C.; Wang, Z.B.; Ma, J. Enhancing CO2 storage and marine carbon sink based on seawater mineral carbonation. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 206, 116685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Teng, L.; Rohani, S.; Qin, Z.; Zhao, B.; Xu, C.C.; Ren, S.; Liu, Q.; Liang, B. CO2 mineral carbonation using industrial solid wastes: A review of recent developments. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, S.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Wang, X. Research on Carbon Sequestration Capacity of Urban Park Green Space in the Central Urban Area of Beijing and Driving Factors Thereof. Landsc. Arch. 2025, 32, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xiao, X.; Gao, W.; Fan, Y.; Tao, S.; Ding, Y.; Zhao, M. The magnitude and potential of the sedimentary carbon sink in the Eastern China Marginal Seas. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclim. Palaeoecol. 2024, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Y.; van Dijk, A.I.J.M.; de Jeu, R.A.M.; Canadell, J.G.; McCabe, M.F.; Evans, J.P.; Wang, G. Recent reversal in loss of global terrestrial biomass. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 470–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Guan, D.; Wei, W.; Davis, S.J.; Ciais, P.; Bai, J.; Peng, S.; Zhang, Q.; Hubacek, K.; Marland, G.; et al. Reduced carbon emission estimates from fossil fuel combustion and cement production in China. Nature 2015, 524, 335–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Fagherazzi, S.; He, Q.; Gourgue, O.; Bai, J.; Liu, X.; Miao, C.; Hu, Z.; Cui, B. A global meta-analysis on the drivers of salt marsh planting success and implications for ecosystem services. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Deng, Z.; Davis, S.J.; Ciais, P. Global carbon emissions in 2023. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 2024, 5, 253–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longman, J.; Mills, B.J.W.; Merdith, A.S. Limited long-term cooling effects of Pangaean flood basalt weathering. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, S.; Baum, C.M.; Sovacool, B.K. Rethinking Net-Zero systems, spaces and societies:“Hard” versus “soft” alternatives for nature-based and engineered carbon removal. Global Environmental Change 2022, 75, 102530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.; Tian, H.; Fu, B.; Yu, H.; Piao, S.; Chen, S.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, M.; Li, Z.; et al. Biophysical and economic constraints on China’s natural climate solutions. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2022, 12, 847–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.; Tian, H.; Fu, B.; Yu, H.; Piao, S.; Chen, S.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, M.; Li, Z.; et al. Biophysical and economic constraints on China’s natural climate solutions. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2022, 12, 847–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, P.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Qu, X. The spatiotemporal evolution of agricultural net carbon sink under the dual carbon target in Hebei Province, China. Second International Conference on Sustainable Technology and Management (ICSTM 2023). 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lucie, G.; Karel, K.; Rusín, J.; Pryszcz, A.; Weisheitelová, M. Biochar – Ecological Product and Its Application in Environmental Protection. DEStech Trans. Eng. Technol. Res. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Cheng, F.; Barckholtz, T.A.; Greig, C.; Larson, E.D. Biopower with molten carbonate fuel cell carbon dioxide capture: Performance, cost, and grid-integration evaluations. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Lü, Y.; Guo, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, T. The thresholds of forest-to-grassland ratios can be critical for harmonizing ecosystem service relationships spatiotemporally in dryland regions. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, Y.; He, L.; Wang, H.; Niu, L.; Yu, X.; Cao, W. Advances in Geochemical Monitoring Technologies for CO2 Geological Storage. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J., Zhou, Y., Cao, W. and Jinfeng, L. (eds.), 2024. Research on a CO2 Internet of Things online monitoring system for geotechnical engineering construction .

- Makepa, D.C.; Chihobo, C.H. Sustainable pathways for biomass production and utilization in carbon capture and storage—a review. Biomass- Convers. Biorefinery 2024, 15, 11397–11419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinković, S. Mineral carbonation of industrial wastes for application in cement-based materials. Gradjevinski materijali i Konstr. 2024, 67, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.H. Glacial-interglacial CO2 change: The Iron Hypothesis. Paleoceanography 1990, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieson, A.; Midgely, J.; Wright, I.; Saoula, N.; Ringrose, P. In Salah CO2 Storage JIP: CO2 sequestration monitoring and verification technologies applied at Krechba, Algeria. Energy Procedia 2011, 4, 3596–3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matter, J.M.; Stute, M.; Snæbjörnsdottir, S.Ó.; Oelkers, E.H.; Gislason, S.R.; Aradottir, E.S.; Sigfusson, B.; Gunnarsson, I.; Sigurdardottir, H.; Gunnlaugsson, E.; et al. Rapid carbon mineralization for permanent disposal of anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions. Science 2016, 352, 1312–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A McKinley, G.; Bennington, V.; Meinshausen, M.; Nicholls, Z. Modern air-sea flux distributions reduce uncertainty in the future ocean carbon sink. Environ. Res. Lett. 2023, 18, 044011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQueen, N.; Psarras, P.; Pilorgé, H.; Liguori, S.; He, J.; Yuan, M.; Woodall, C.M.; Kian, K.; Pierpoint, L.; Jurewicz, J.; et al. Cost Analysis of Direct Air Capture and Sequestration Coupled to Low-Carbon Thermal Energy in the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 7542–7551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQueen, N.; Kelemen, P.; Dipple, G.; Renforth, P.; Wilcox, J. Ambient weathering of magnesium oxide for CO2 removal from air. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McTigue, N.; Davis, J.; Rodriguez, A.B.; McKee, B.; Atencio, A.; Currin, C.; Rodriguez, T. Sea Level Rise Explains Changing Carbon Accumulation Rates in a Salt Marsh Over the Past Two Millennia. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 2019, 124, 2945–2957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinshausen, M.; Nicholls, Z.R.J.; Lewis, J.; Gidden, M.J.; Vogel, E.; Freund, M.; Beyerle, U.; Gessner, C.; Nauels, A.; Bauer, N.; et al. The shared socio-economic pathway (SSP) greenhouse gas concentrations and their extensions to 2500. Geosci. Model Dev. 2020, 13, 3571–3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meli, M. and Bruno, L., 2021. Changes in land use in the last two centuries in the Po lowlands (northern Italy), EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts, pp. EGU21-9780 .

- Meng, J.; Liao, W.; Zhang, G. Emerging CO2-Mineralization Technologies for Co-Utilization of Industrial Solid Waste and Carbon Resources in China. Minerals 2021, 11, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Lu, F.; Cheng, B. China’s Climate Change Policy Attention and Forestry Carbon Sequestration Growth. Forests 2023, 14, 2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meybeck, M. Global chemical weathering of surficial rocks estimated from river dissolved loads. Am. J. Sci. 1987, 287, 401–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meysman, F.J.R.; Montserrat, F. Negative CO 2 emissions via enhanced silicate weathering in coastal environments. Biol. Lett. 2017, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millero, F.J. Chemical Oceanography. Chemical Oceanography. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Minx, J.C.; Lamb, W.F.; Callaghan, M.W.; Fuss, S.; Hilaire, J.; Creutzig, F.; Amann, T.; Beringer, T.; Garcia, W.d.O.; Hartmann, J.; et al. Negative emissions—Part 1: Research landscape and synthesis. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 063001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsch, W.J.; et al. Wetlands, carbon and climate change. Landscape Ecology 2013, 28, 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montserrat, F.; Renforth, P.; Hartmann, J.; Leermakers, M.; Knops, P.; Meysman, F.J.R. Olivine Dissolution in Seawater: Implications for CO2 Sequestration through Enhanced Weathering in Coastal Environments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 3960–3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, C.M.; Mills, M.M.; Arrigo, K.R.; Berman-Frank, I.; Bopp, L.; Boyd, P.W.; Galbraith, E.D.; Geider, R.J.; Guieu, C.; Jaccard, S.L.; et al. Processes and patterns of oceanic nutrient limitation. Nat. Geosci. 2013, 6, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.A.; Kovacs, K.F. Marginal Cost of Carbon Abatement through Afforestation of Agricultural Land in the Mississippi Delta. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mulder, I. and Initiative, E.O.L.D., 2021. State of finance for nature: Tripling investments in nature-based solutions by 2030.

- Muri, H. The role of large—scale BECCS in the pursuit of the 1.5°C target: an Earth system model perspective. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 044010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muri, H. and Sathyanadh, A., 2024. Report on carbon cycle interactions and efficacy of land-based CDRs (e.g. BECCS), when combined with oceanic CDRs (individually or in a portfolio) .

- Muri, H. and Sathyanadh, A., 2024. Report on carbon cycle interactions and efficacy of land-based CDRs (eg BECCS), when combined with oceanic CDRs (individually or in a portfolio) .

- Muslemani, H.; Liang, X.; Kaesehage, K.; Wilson, J. Business Models for Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage Technologies in the Steel Sector: A Qualitative Multi-Method Study. Processes 2020, 8, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, G.; He, X.; Ma, L.; Qin, S.; Han, L.; Xu, S. Identify a sustainable afforestation pattern for soil carbon sequestration: Considering both soil water-carbon conversion efficiency and their coupling relationship on the Loess Plateau. Land Degrad. Dev. 2024, 35, 2058–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, H.; Yin, J.; Yang, F.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, L.; Cao, X. Pyrolysis temperature-dependent carbon retention and stability of biochar with participation of calcium: Implications to carbon sequestration. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 287, 117566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, E.A.M. et al., 2021. A Research Strategy for Ocean-based Carbon Dioxide Removal and Sequestration. National Academies Press (US), Washington (DC).

- National Academies Of Sciences, E.A.M., 2021. A research strategy for ocean-based carbon dioxide removal and sequestration.

- Nawaz, S.; Satterfield, T. Towards just, responsible, and socially viable carbon removal: lessons from offshore DACCS research for early-stage carbon removal projects. Environ. Sci. Policy 2023, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehler, T.; Fridahl, M. Regulatory Preconditions for the Deployment of Bioenergy With Carbon Capture and Storage in Europe. Front. Clim. 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nellemann, C. et al., 2009. Blue carbon - A rapid response assessment. Environment, 9.

- Nguyen, T., 2017. Climeworks joins project to trap CO2. Chemical & Engineering News.

- Nisbet, H.; Buscarnera, G.; Carey, J.W.; Chen, M.A.; Detournay, E.; Huang, H.; Hyman, J.D.; Kang, P.K.; Kang, Q.; Labuz, J.F.; et al. Carbon Mineralization in Fractured Mafic and Ultramafic Rocks: A Review. Rev. Geophys. 2024, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisbet, H.; Buscarnera, G.; Carey, J.W.; Chen, M.A.; Detournay, E.; Huang, H.; Hyman, J.D.; Kang, P.K.; Kang, Q.; Labuz, J.F.; et al. Carbon Mineralization in Fractured Mafic and Ultramafic Rocks: A Review. Rev. Geophys. 2024, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, T.; Yu, J.; Yue, D.; Yang, L.; Mao, X.; Hu, Y.; Long, Q. The Temporal and Spatial Evolution of Ecosystem Service Synergy/Trade-Offs Based on Ecological Units. Forests 2021, 12, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odum, E.P. The Strategy of Ecosystem Development. Science 1969, 164, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olafsson, J.; Olafsdottir, S.R.; Takahashi, T.; Danielsen, M.; Arnarson, T.S. Enhancement of the North Atlantic CO2 sink by Arctic Waters. Biogeosciences 2021, 18, 1689–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, J.C.; et al. Anthropogenic ocean acidification over the twenty-first century and its impact on calcifying organisms. Nature 2005, 437, 681–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozkan, M. Atmospheric alchemy: The energy and cost dynamics of direct air carbon capture. MRS Energy Sustain. 2024, 12, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Shrestha, A.; Innes, J.L.; Zhou, G.; Li, N.; Li, J.; He, Y.; Sheng, C.; Niles, J.-O.; Wang, G. Key challenges and approaches to addressing barriers in forest carbon offset projects. J. For. Res. 2022, 33, 1109–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.-Y.; Chen, Y.-H.; Fan, L.-S.; Kim, H.; Gao, X.; Ling, T.-C.; Chiang, P.-C.; Pei, S.-L.; Gu, G. CO2 mineralization and utilization by alkaline solid wastes for potential carbon reduction. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Birdsey, R.A.; Fang, J.; Houghton, R.; Kauppi, P.E.; Kurz, W.A.; Phillips, O.L.; Shvidenko, A.; Lewis, S.L.; Canadell, J.G.; et al. A Large and Persistent Carbon Sink in the World’s Forests. Science 2011, 333, 988–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Swaroopa, V.J.; Kushal; Sahu, P. L.; Parmar, B. A Comprehensive Review on Carbon Sequestration Potential and Addition of Organic Carbon to Soil. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Chang. 2024, 14, 724–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, M.; Petersen, S.; Lozano, E.; Pedersen, T. Techno-economic study of integrated high-temperature direct air capture with hydrogen-based calcination and Fischer–Tropsch synthesis for jet fuel production. Appl. Energy 2024, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, S.; Fang, J.; Ciais, P.; Peylin, P.; Huang, Y.; Sitch, S.; Wang, T. The carbon balance of terrestrial ecosystems in China. Nature 2009, 458, 1009–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, K.; Li, X.; Bastos, A.; Canadell, J.G.; Ciais, P.; Friedlingstein, P.; Sitch, S. Interannual variation of terrestrial carbon cycle: Issues and perspectives. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2019, 26, 300–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, S.; He, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, F. Estimation of China’s terrestrial ecosystem carbon sink: Methods, progress and prospects. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2022, 65, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokrovsky, O.S.; Schott, J. Experimental study of brucite dissolution and precipitation in aqueous solutions: surface speciation and chemical affinity control. Geochim. et Cosmochim. Acta 2004, 68, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, R.T.; Salter, I.; Sanders, R.J.; Lucas, M.I.; Moore, C.M.; Mills, R.A.; Statham, P.J.; Allen, J.T.; Baker, A.R.; Bakker, D.C.E.; et al. Southern Ocean deep-water carbon export enhanced by natural iron fertilization. Nature 2009, 457, 577–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, W.M.; Emanuel, W.R.; Zinke, P.J.; Stangenberger, A.G. Soil carbon pools and world life zones. Nature 1982, 298, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pour, N.M., 2019. Status of bioenergy with carbon capture and storage—potential and challenges. Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage .

- Prado, A.; Chiquier, S.; Fajardy, M.; Mac Dowell, N. Assessing the impact of carbon dioxide removal on the power system. iScience 2023, 26, 106303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prado, A.; Chiquier, S.; Fajardy, M.; Mac Dowell, N. Assessing the impact of carbon dioxide removal on the power system. iScience 2023, 26, 106303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Presty, R.; Massol, O.; Jagu, E.; da Costa, P. Mapping the landscape of carbon dioxide removal research: a bibliometric analysis. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 103004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psarras, P.; Krutka, H.; Fajardy, M.; Zhang, Z.; Liguori, S.; Mac Dowell, N.; Wilcox, J. Slicing the pie: how big could carbon dioxide removal be? WIREs Energy Environ. 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, T.A.M.; Lindeskog, M.; Smith, B.; Poulter, B.; Arneth, A.; Haverd, V.; Calle, L. Role of forest regrowth in global carbon sink dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 4382–4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zhuang, Q. Soil organic carbon sequestration potential of cropland in China. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2013, 27, 711–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quéré, C.L.; et al. Two decades of ocean CO2 sink and variability. Tellus B: Chemical and Physical Meteorology 2003, 55, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, A.; Yadav, A.; Arya, S.; Sirohi, R.; Kumar, S.; Rawat, A.P.; Thakur, R.S.; Patel, D.K.; Bahadur, L.; Pandey, A. Preparation, characterization and agri applications of biochar produced by pyrolysis of sewage sludge at different temperatures. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 795, 148722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratouis, T.M.; Snæbjörnsdóttir, S.Ó.; Voigt, M.J.; Sigfússon, B.; Gunnarsson, G.; Aradóttir, E.S.; Hjörleifsdóttir, V. Carbfix 2: A transport model of long-term CO2 and H2S injection into basaltic rocks at Hellisheidi, SW-Iceland. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2022, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Reiners, W. Terrestrial detritus and the carbon cycle. . 1973, 303–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, H.; Hu, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Mou, L.; Pan, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Li, G.; Jiao, N. Response of a Coastal Microbial Community to Olivine Addition in the Muping Marine Ranch, Yantai. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 805361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, S.; Terrer, C.; Li, J.; Cao, Y.; Yang, S.; Liu, D. Historical impacts of grazing on carbon stocks and climate mitigation opportunities. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2024, 14, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, D.; Zhang, H. Spatial and temporal effects on the value of ecosystem services in arid and semi-arid mountain areas—A case study from Helan Mountain in Ningxia, China. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaud, S.; Ziveri, P.; Broerse, A.T. Geographical and seasonal differences in morphology and dynamics of the coccolithophore Calcidiscus leptoporus. Mar. Micropaleontol. 2002, 46, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renforth, P.; Henderson, G. Assessing ocean alkalinity for carbon sequestration. Rev. Geophys. 2017, 55, 636–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resplandy, L.; Séférian, R.; Bopp, L. Natural variability of CO2 and O2 fluxes: What can we learn from centuries-long climate models simulations? Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 2015, 120, 384–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, K.R. A Brief Overview of Carbon Sequestration Economics and Policy. Environ. Manag. 2004, 33, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickels, W.; Proelß, A.; Geden, O.; Burhenne, J.; Fridahl, M. Integrating Carbon Dioxide Removal Into European Emissions Trading. Front. Clim. 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringrose, P.S.; Furre, A.-K.; Gilfillan, S.M.; Krevor, S.; Landrø, M.; Leslie, R.; Meckel, T.; Nazarian, B.; Zahid, A. Storage of Carbon Dioxide in Saline Aquifers: Physicochemical Processes, Key Constraints, and Scale-Up Potential. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 2021, 12, 471–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rittl, T.F., 2015. Challenging the claims on the potential of biochar to mitigate climate change. Wageningen University and Research .

- Rödenbeck, C.; Bakker, D.C.E.; Gruber, N.; Iida, Y.; Jacobson, A.R.; Jones, S.; Landschützer, P.; Metzl, N.; Nakaoka, S.; Olsen, A.; et al. Data-based estimates of the ocean carbon sink variability – first results of the Surface Ocean pCO2 Mapping intercomparison (SOCOM). Biogeosciences 2015, 12, 7251–7278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rödenbeck, C. et al., 2015. Data-based estimates of the ocean carbon sink variability – first results of the Surface Ocean pCO2 Mapping intercomparison (SOCOM). Biogeosciences, 12(23): 7251-7278.

- Rodosta, T. and Ackiewicz, M., 2014. US DOE/NETL Core R&D Program for Carbon Storage Technology Development. In: Dixon, T., Herzog, H. and Twinning, S. (Dixon, T., Herzog, H. and Twinning, S.(Editors), 12TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON GREENHOUSE GAS CONTROL TECHNOLOGIES, GHGT-12, 12th International Conference on Greenhouse Gas Control Technologies (GHGT), pp. 6368-6378.

- Rodrigues, L.; Budai, A.; Elsgaard, L.; Hardy, B.; Keel, S.G.; Mondini, C.; Plaza, C.; Leifeld, J. The importance of biochar quality and pyrolysis yield for soil carbon sequestration in practice. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2023, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roemmich, D.; Alford, M.H.; Claustre, H.; Johnson, K.; King, B.; Moum, J.; Oke, P.; Owens, W.B.; Pouliquen, S.; Purkey, S.; et al. On the Future of Argo: A Global, Full-Depth, Multi-Disciplinary Array. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohr, T. Southern Ocean Iron Fertilization: An Argument Against Commercialization but for Continued Research Amidst Lingering Uncertainty. J. Sci. Policy Gov. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda, O.; Mogollón, J.; Tukker, A.; Scherer, L. Negative-emissions technology portfolios to meet the 1.5 °C target. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2021, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saari, J.; Peltola, P.; Kuparinen, K.; Kaikko, J.; Sermyagina, E.; Vakkilainen, E. Novel BECCS implementation integrating chemical looping combustion with oxygen uncoupling and a kraft pulp mill cogeneration plant. Mitig. Adapt. Strat. Glob. Chang. 2023, 28, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakib, K.N.; Ahmed, S.N.; Mubdee, A.; Kirtania, K. Biochar Production from Waste Biomass using Modular Pyrolyzer for Soil Amendment. Chem. Eng. Res. Bull. 2021, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salma, A.; Fryda, L.; Djelal, H. Biochar: A Key Player in Carbon Credits and Climate Mitigation. Resources 2024, 13, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, J.L.; et al. Sea-air CO2 fluxes and carbon transport: A comparison of three ocean general circulation models. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 2000, 14, 1267–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, J.L.; Gloor, M.; Gruber, N.; Beaulieu, C.; Jacobson, A.R.; Fletcher, S.E.M.; Pacala, S.; Rodgers, K. Trends and regional distributions of land and ocean carbon sinks. Biogeosciences 2010, 7, 2351–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, J.L.; Gruber, N. Sinks for Anthropogenic Carbon. Phys. Today 2002, 55, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satterfield, T.; Nawaz, S.; St-Laurent, G.P. Exploring public acceptability of direct air carbon capture with storage: climate urgency, moral hazards and perceptions of the ‘whole versus the parts’. Clim. Chang. 2023, 176, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunois, M.; et al. The Global Methane Budget 2000–2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2020, 12, 1561–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger, W.H. An evaluation of abiotic carbon sinks in deserts. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2016, 23, 25–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, P. Carbon storage potential of short rotation tropical tree plantations. For. Ecol. Manag. 1992, 50, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwinger, J.; Bourgeois, T.; Rickels, W. On the emission-path dependency of the efficiency of ocean alkalinity enhancement. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 074067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searchinger, T.D.; Wirsenius, S.; Beringer, T.; Dumas, P. Assessing the efficiency of changes in land use for mitigating climate change. Nature 2018, 564, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddon, N.; Chausson, A.; Berry, P.; Girardin, C.A.J.; Smith, A.; Turner, B. Understanding the value and limits of nature-based solutions to climate change and other global challenges. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2020, 375, 20190120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddon, N.; Smith, A.; Smith, P.; Key, I.; Chausson, A.; Girardin, C.; House, J.; Srivastava, S.; Turner, B. Getting the message right on nature-based solutions to climate change. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2021, 27, 1518–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackley, S.; Reiner, D.; Upham, P.; de Coninck, H.; Sigurthorsson, G.; Anderson, J. The acceptability of CO2 capture and storage (CCS) in Europe: An assessment of the key determining factors. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2009, 3, 344–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, R.; Chen, J.M.; Xu, M.; Lin, X.; Li, P.; Yu, G.; He, N.; Xu, L.; Gong, P.; Liu, L.; et al. China’s current forest age structure will lead to weakened carbon sinks in the near future. Innov. 2023, 4, 100515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, M. Straw Biochar Production and Carbon Emission Reduction Potential in the Yangtze River Economic Belt Region. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2024, 34, 2349–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharrow, S.; Ismail, S. Carbon and nitrogen storage in agroforests, tree plantations, and pastures in western Oregon, USA. Agrofor. Syst. 2004, 60, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Ji, Y.; Zhang, X.; Fang, M.; Wang, T.; Jiang, L. Understandings on design and application for direct air capture: From advanced sorbents to thermal cycles. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, D.A.; DeVries, T.; Cetinić, I.; Bisson, K.M. Quantifying the Ocean's Biological Pump and Its Carbon Cycle Impacts on Global Scales. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2023, 15, 329–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; Davis, S.J.; Creutzig, F.; Fuss, S.; Minx, J.; Gabrielle, B.; Kato, E.; Jackson, R.B.; Cowie, A.; Kriegler, E.; et al. Biophysical and economic limits to negative CO2 emissions. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 6, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; Adams, J.; Beerling, D.J.; Beringer, T.; Calvin, K.V.; Fuss, S.; Griscom, B.; Hagemann, N.; Kammann, C.; Kraxner, F.; et al. Land-Management Options for Greenhouse Gas Removal and Their Impacts on Ecosystem Services and the Sustainable Development Goals. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2019, 44, 255–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snæbjörnsdóttir, S.Ó.; et al. Carbon dioxide storage through mineral carbonation. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 2020, 1, 90–102. [Google Scholar]