Submitted:

02 September 2025

Posted:

03 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

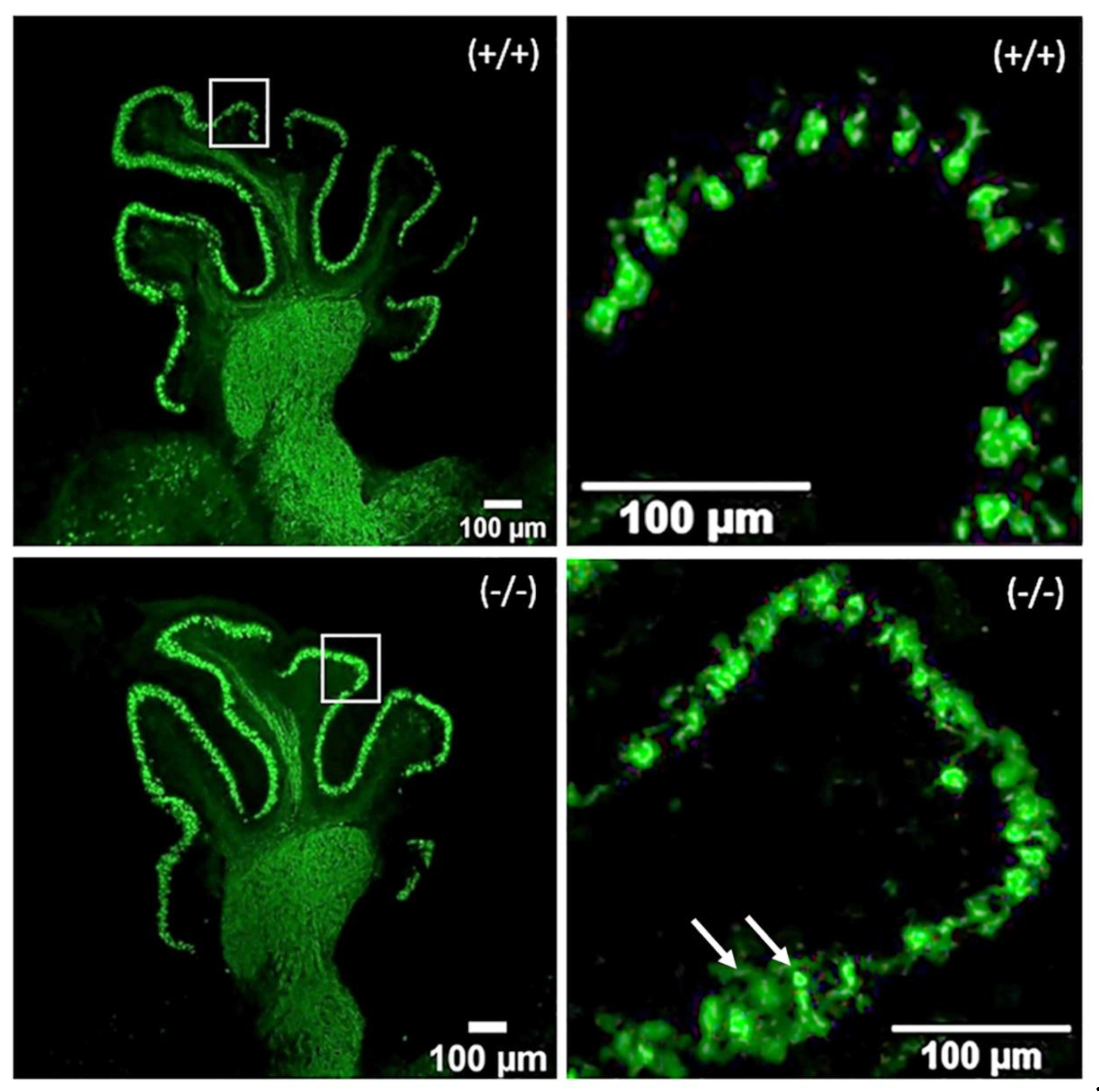

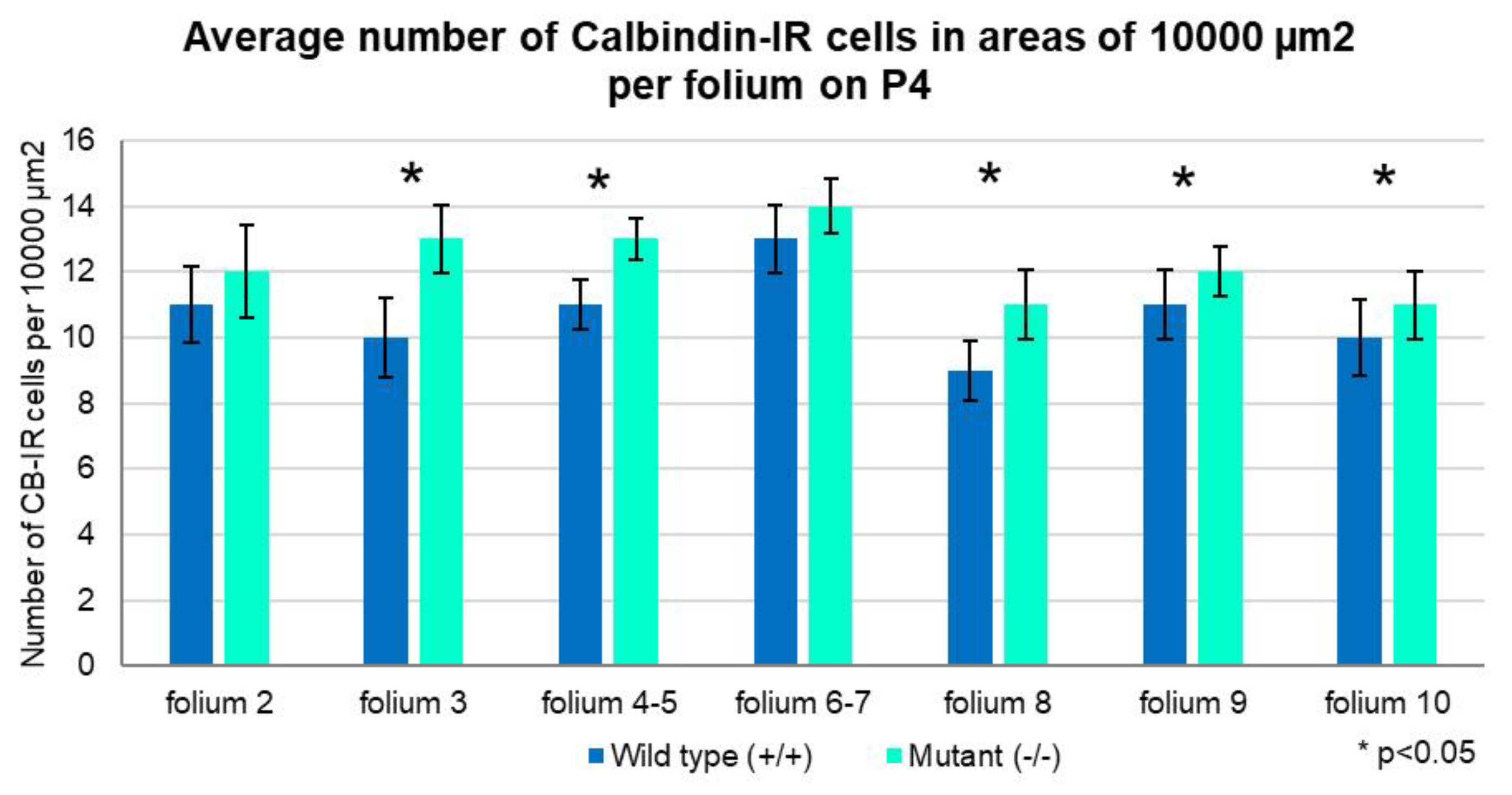

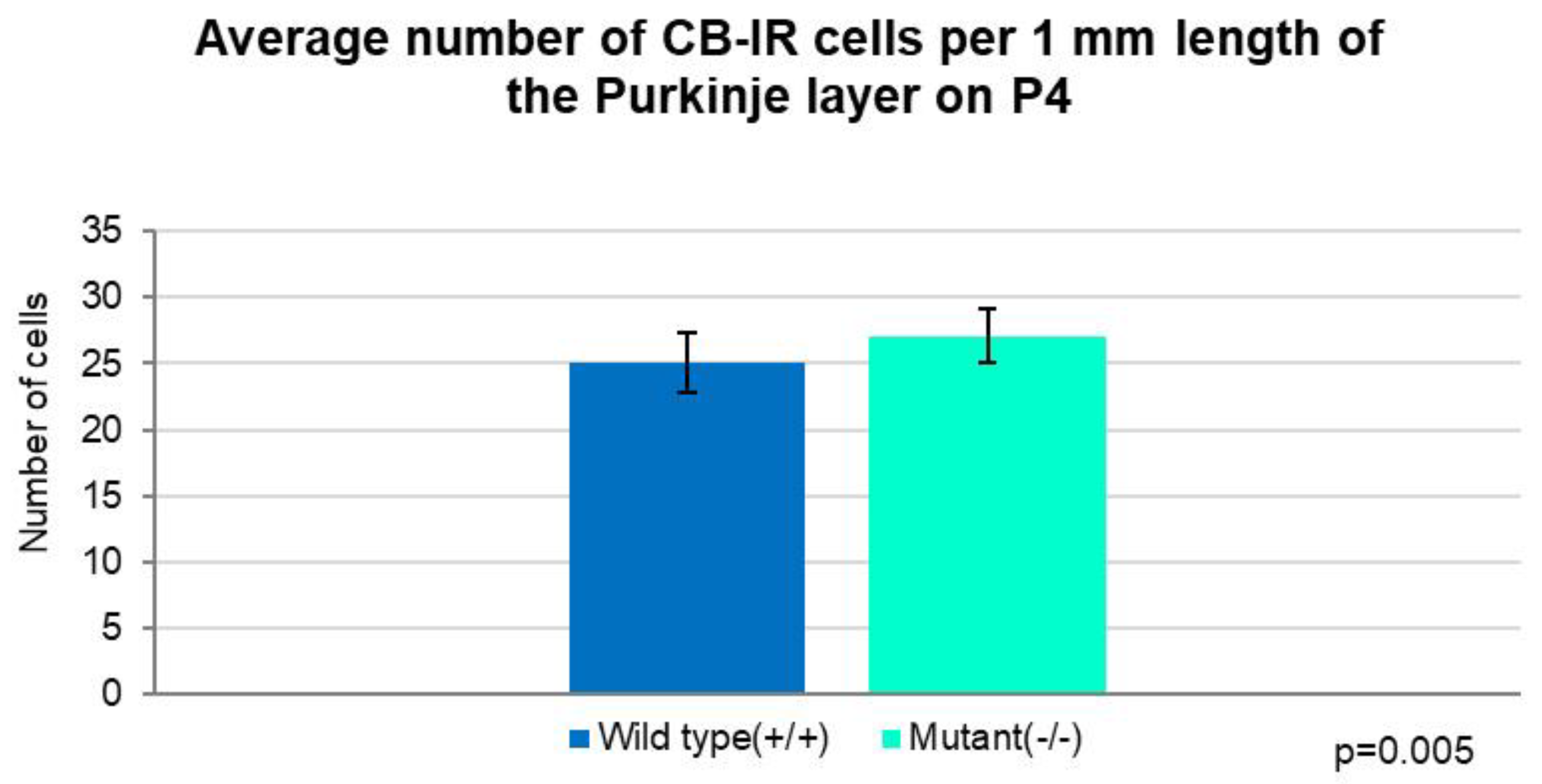

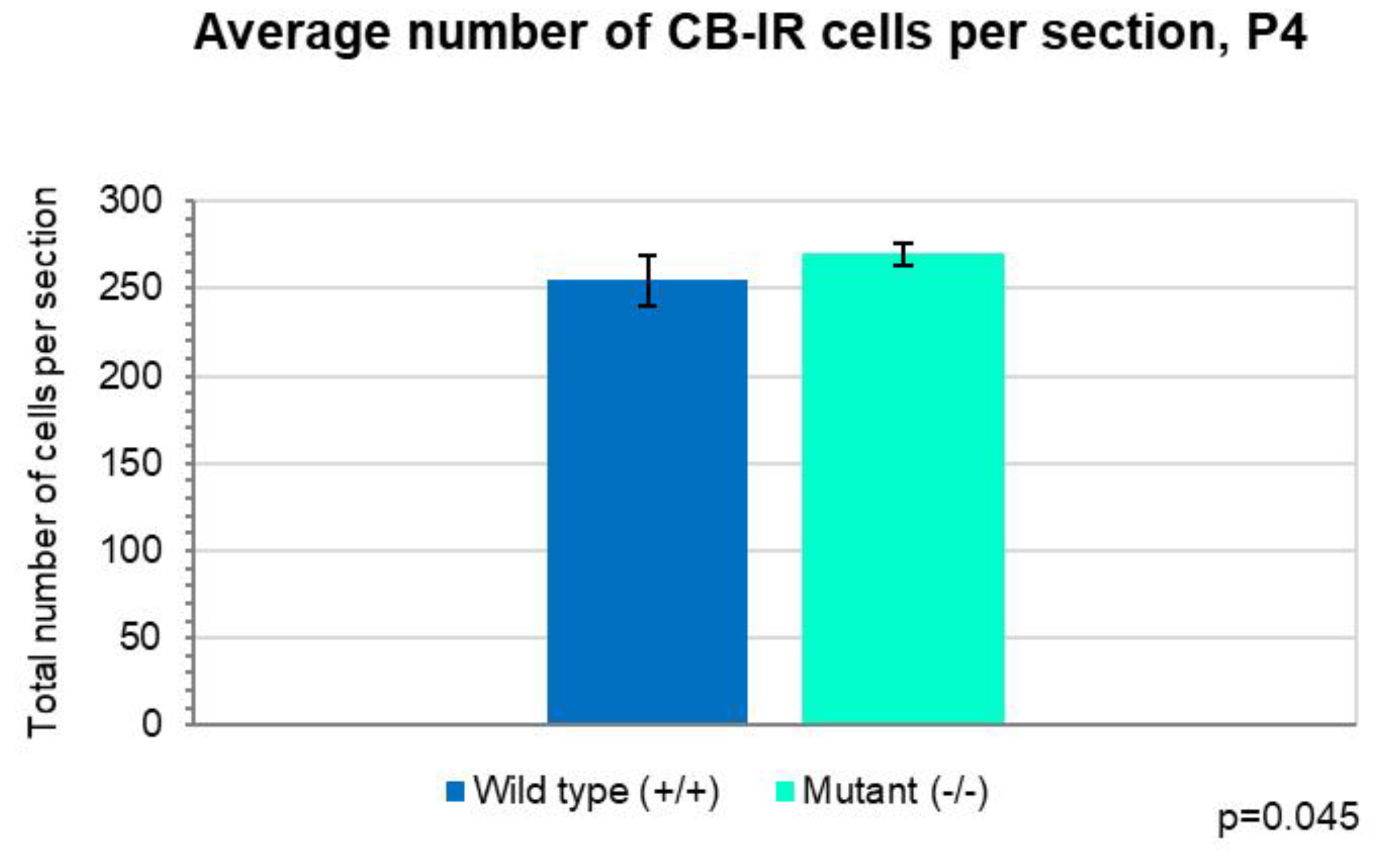

2.1. Development of PCs at Postnatal Day 4

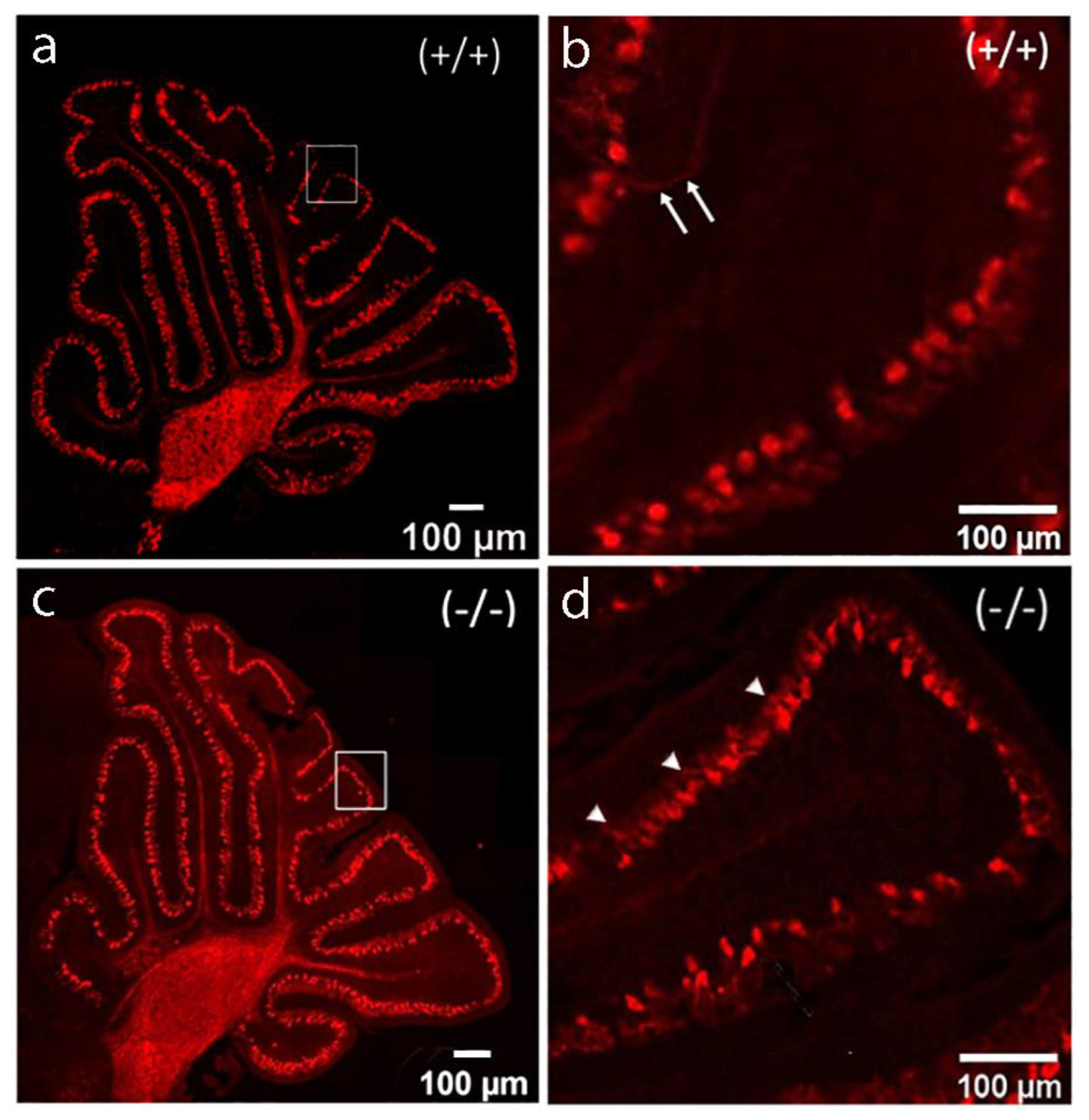

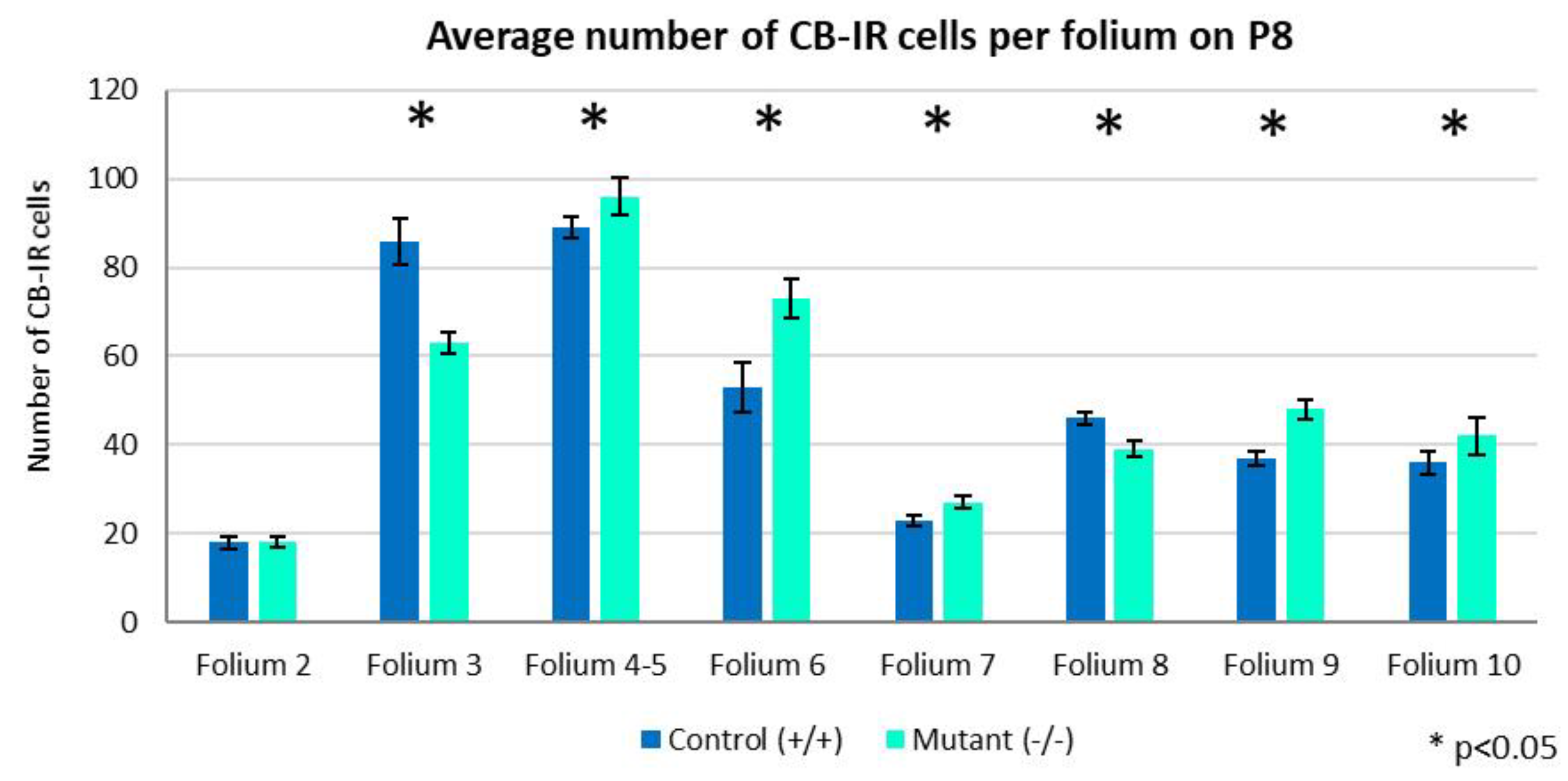

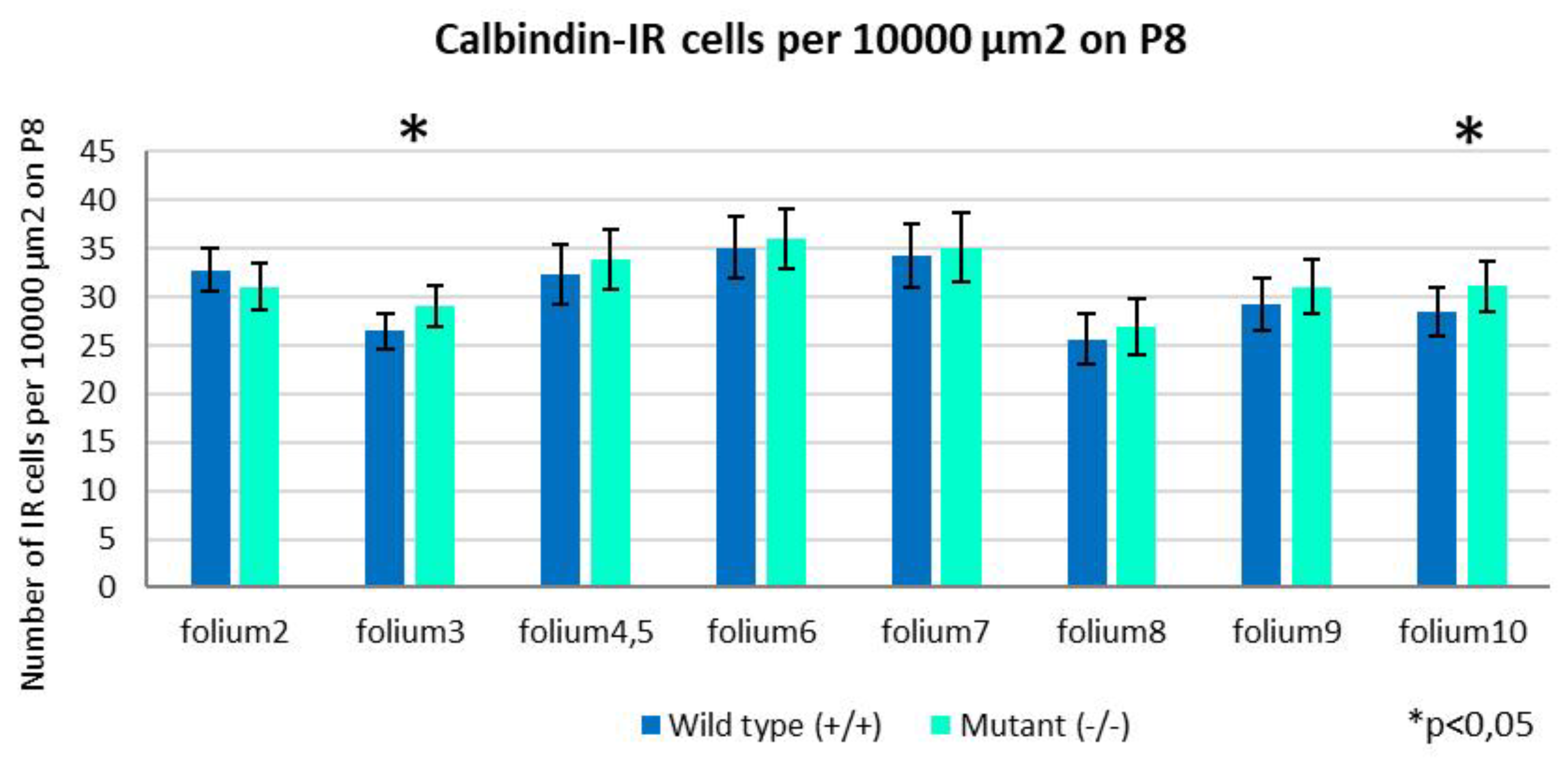

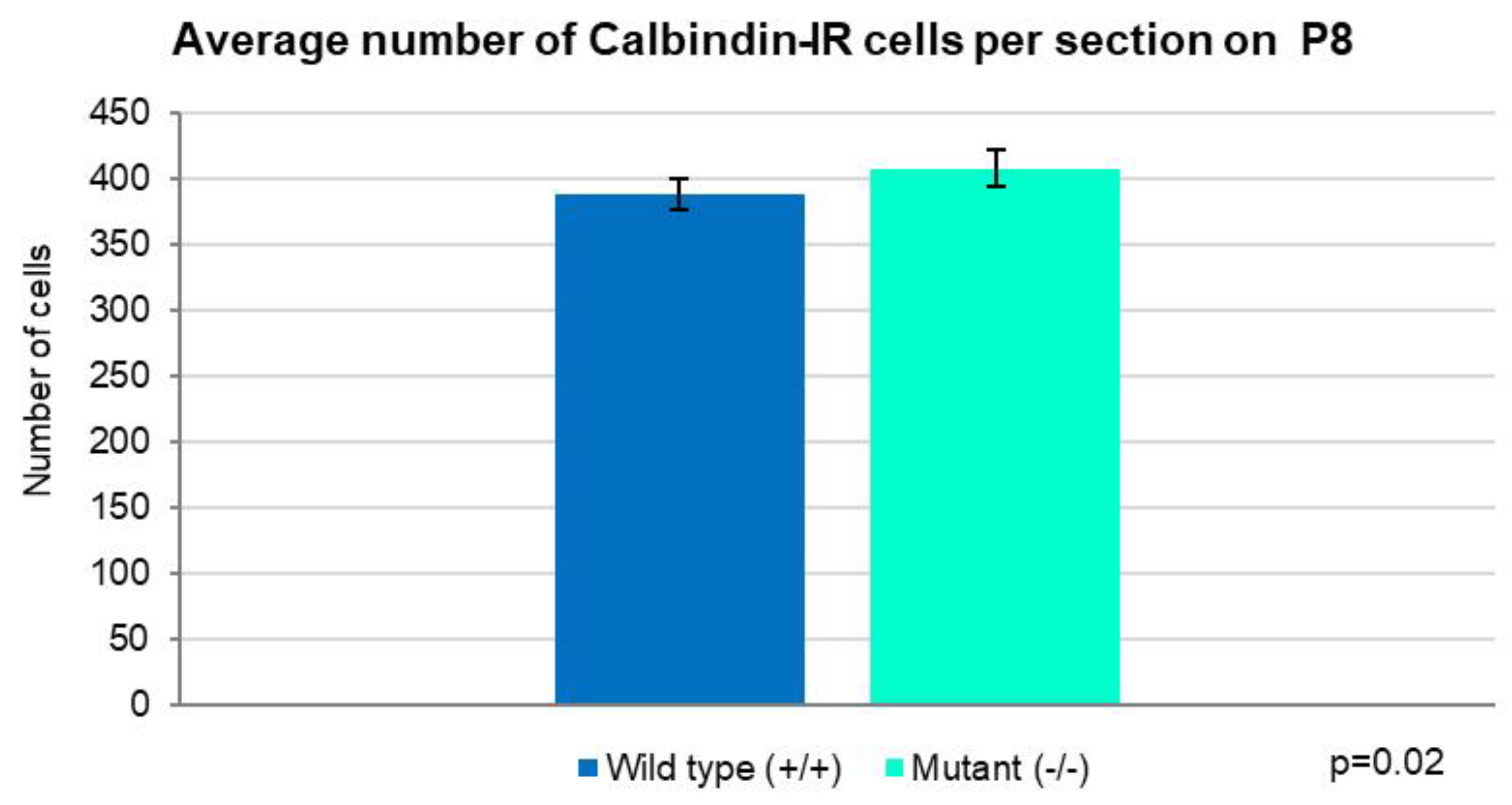

2.2. Development of PCs at Postnatal Day 8

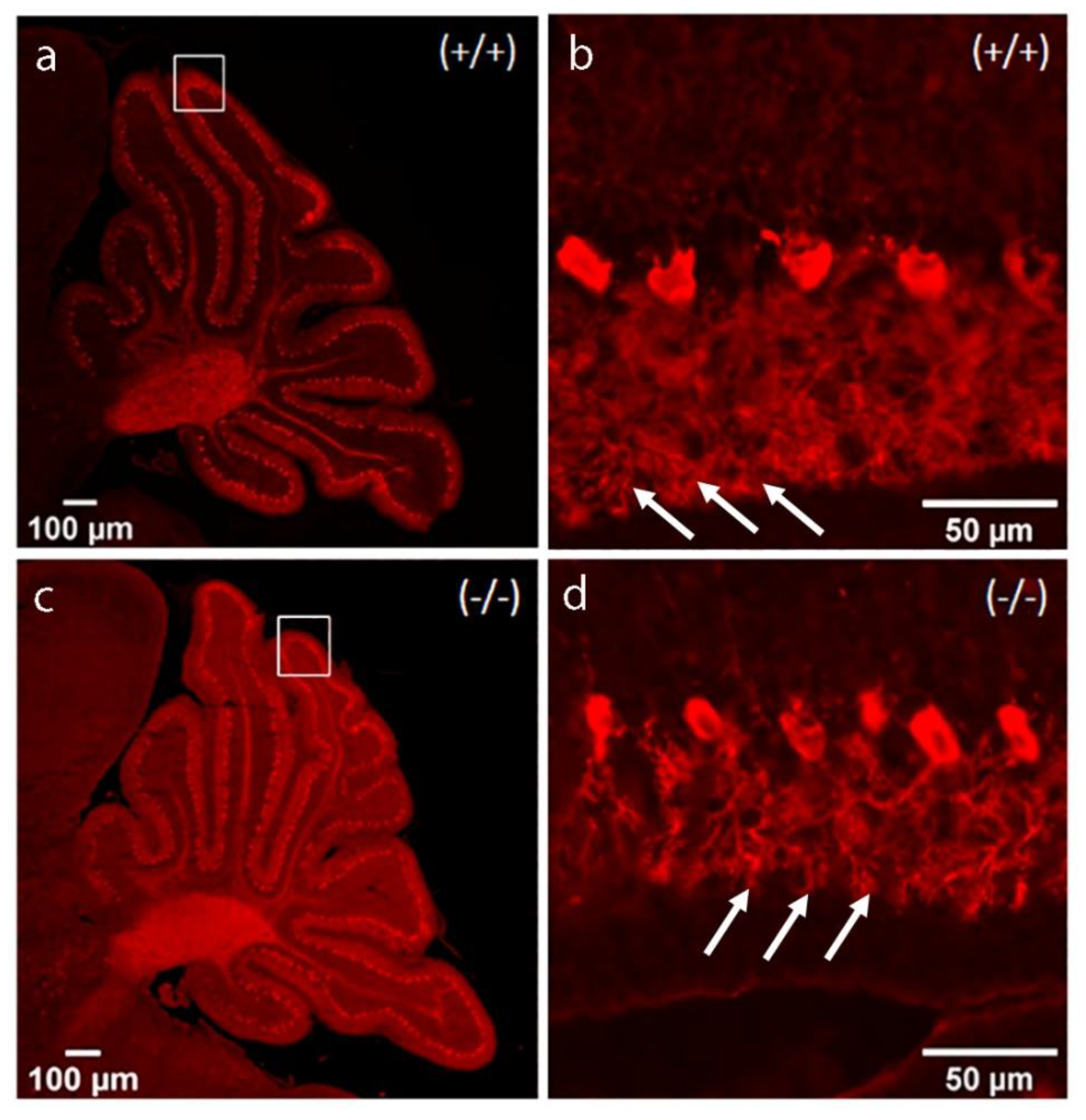

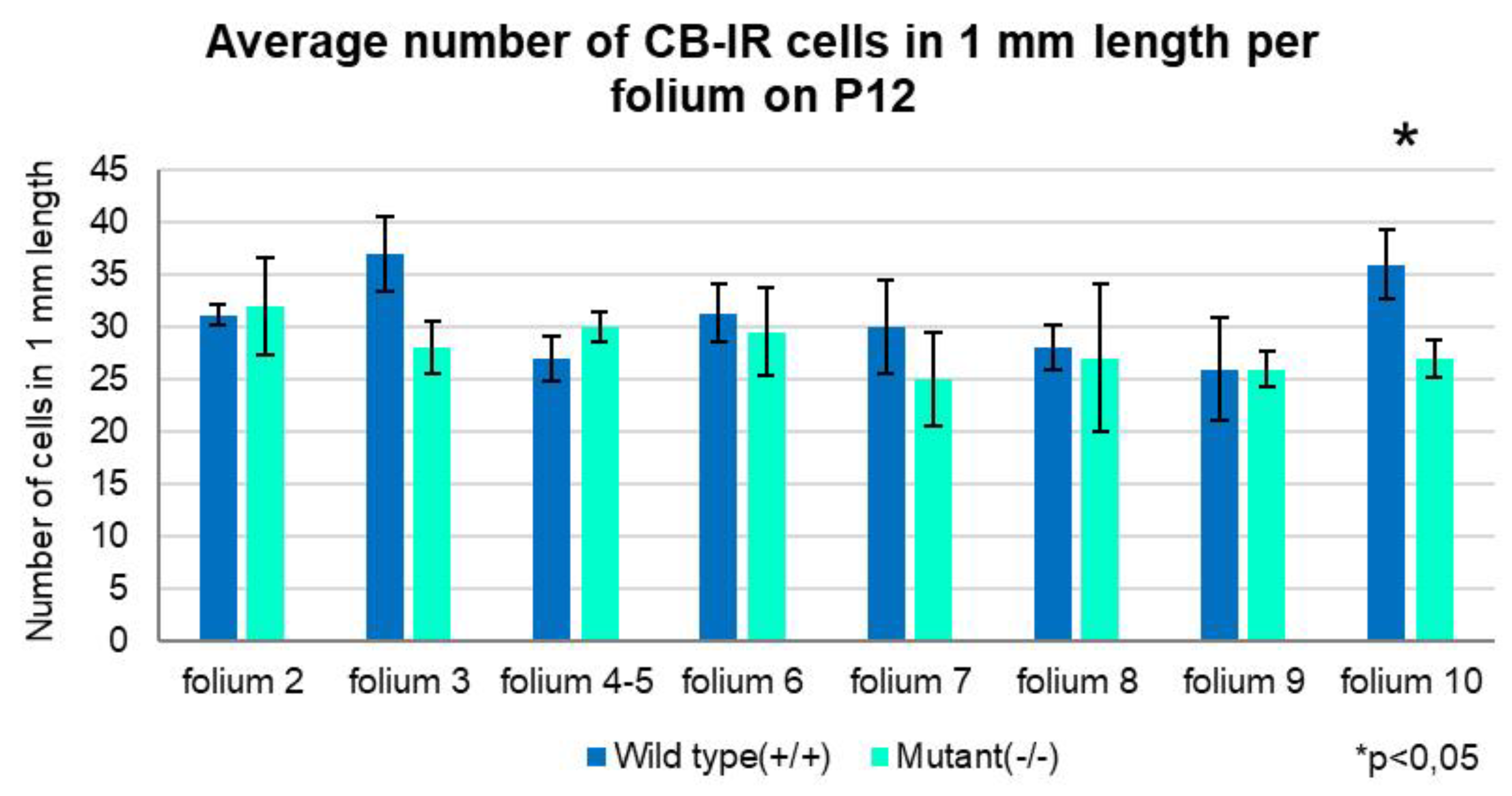

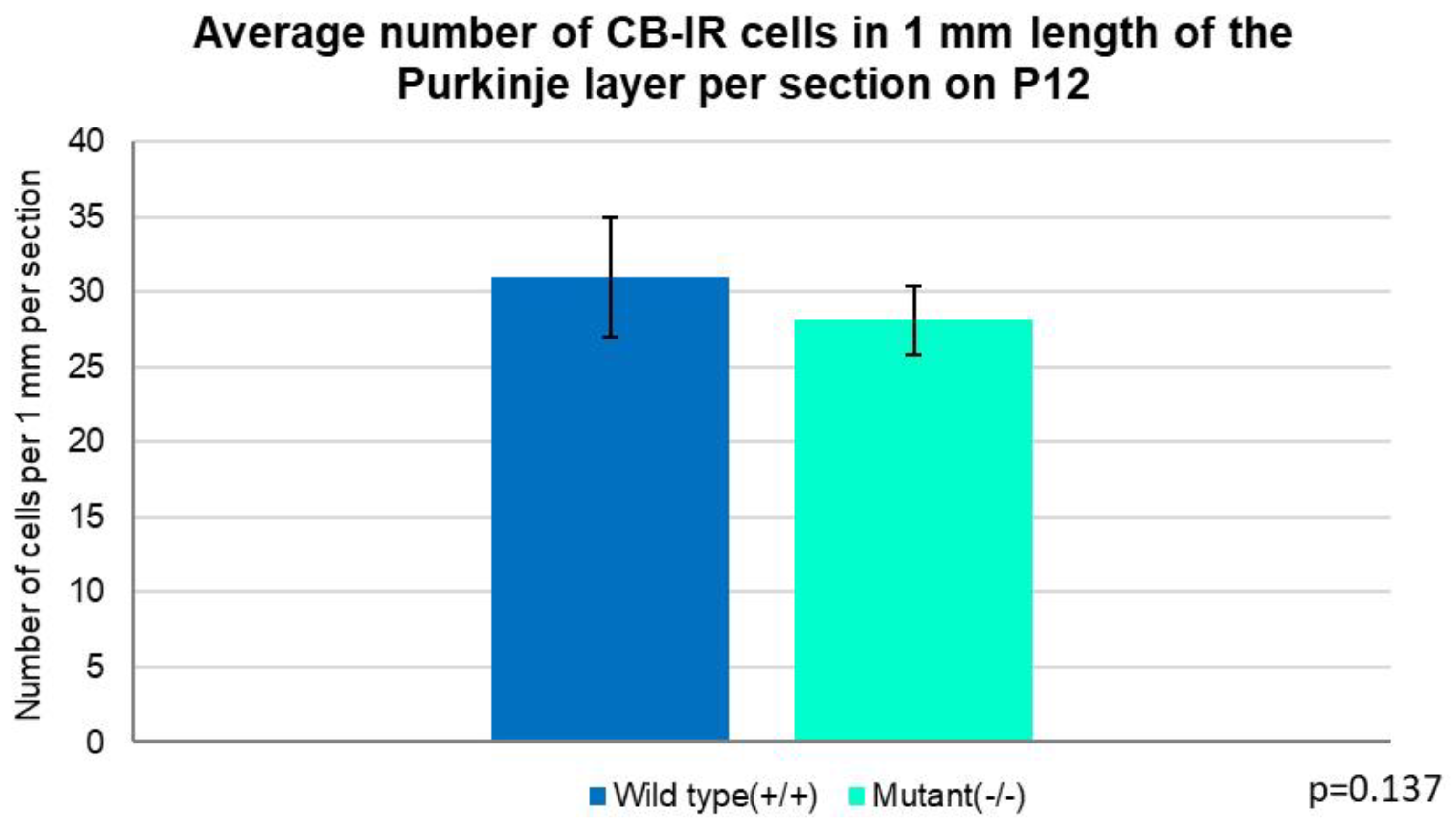

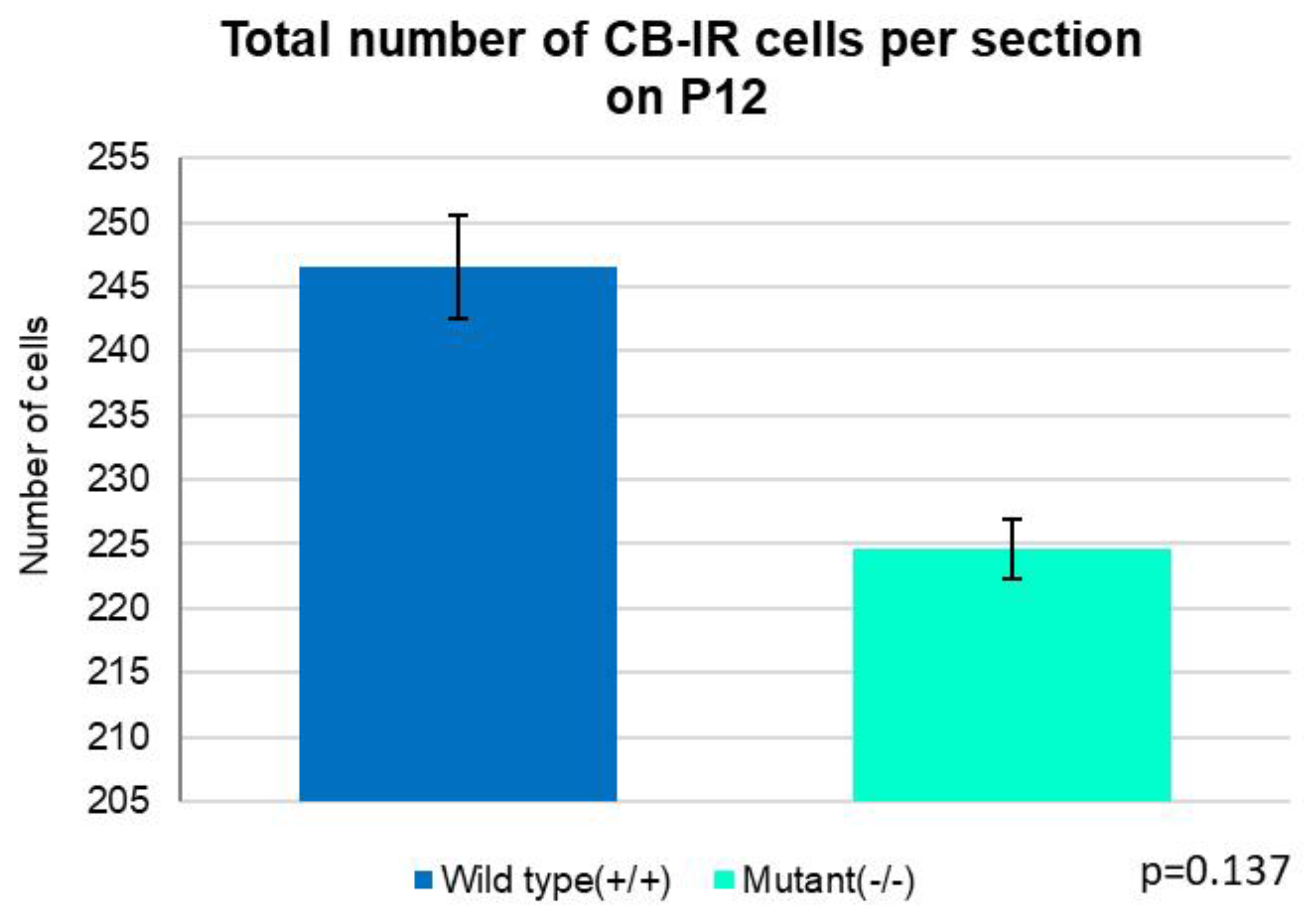

2.3. Development of PCs at Postnatal Day 8

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Animals and Tissues Preparation

4.2. Immunofluorescent Staining

4.3. Imaging and Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Zbtb20 | Zink finger and BTB domain-containing protein 20 |

| PCs | Purkinje cells |

| CB | Calbindin |

| IR | Immunoreactive |

References

- Schmahmann, J.D. and D. Caplan, Cognition, emotion and the cerebellum. Brain 2006, 129, 290–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmahmann, J.D. ; The cerebellum and cognition. Neurosci Lett 2019, 688, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- y Cajal, S.R. ; Estructura de los centros nerviosos de las aves. 1888.

- Cajal, S.R. ; Recuerdos de mi vida, Vol. 2, Historia de mi labor científica. Madrid: Moya, 1917.

- Sultan, F. and J.M. Bower, Quantitative Golgi study of the rat cerebellar molecular layer interneurons using principal component analysis. Journal of Comparative Neurology 1998, 393, 353–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leto, K.; et al. Different types of cerebellar GABAergic interneurons originate from a common pool of multipotent progenitor cells. Journal of Neuroscience 2006, 26, 11682–11694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgaier, S.K.; et al. Morphogenetic and cellular movements that shape the mouse cerebellum; insights from genetic fate mapping. Neuron 2005, 45, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, K. ; Moving into shape: cell migration during the development and histogenesis of the cerebellum. Histochem Cell Biol 2018, 150, 13–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrup, K. and B. Kuemerle, The compartmentalization of the cerebellum. Annu Rev Neurosci 1997, 20, 61–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashida, R.; et al. Principles of organization of the human cerebellum: macro- and microanatomy. Handb Clin Neurol 2018, 154, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Geurts, F.J. E. De Schutter, and S. Dieudonné, Unraveling the cerebellar cortex: cytology and cellular physiology of large-sized interneurons in the granular layer. Cerebellum 2003, 2, 290–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvez, M.S.A. and G. Ohtsuki, Acute Cerebellar Inflammation and Related Ataxia: Mechanisms and Pathophysiology. 2022, 12.

- Tsai, P.T.; et al. Autistic-like behaviour and cerebellar dysfunction in Purkinje cell Tsc1 mutant mice. Nature 2012, 488, 647–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardi, S. F. Gemignani, and M. Marchese, The involvement of Purkinje cells in progressive myoclonic epilepsy: Focus on neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Neurobiol Dis 2023, 185, 106258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pilar, C.; et al. The Selective Loss of Purkinje Cells Induces Specific Peripheral Immune Alterations. Front Cell Neurosci 2021, 15, 773696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; et al. Structures and biological functions of zinc finger proteins and their roles in hepatocellular carcinoma. 2022. 10, 2.

- Kelly, K.F. and J.M. Daniel, POZ for effect--POZ-ZF transcription factors in cancer and development. Trends Cell Biol 2006, 16, 578–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albagli, O.; et al. The BTB/POZ domain: a new protein-protein interaction motif common to DNA- and actin-binding proteins. Cell Growth Differ 1995, 6, 1193–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Arie, N.; et al. Math1 is essential for genesis of cerebellar granule neurons. Nature 1997, 390, 169–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberdick, J.; et al. A promoter that drives transgene expression in cerebellar Purkinje and retinal bipolar neurons. Science 1990, 248, 223–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonchev, A.B.; et al. Zbtb20 modulates the sequential generation of neuronal layers in developing cortex. Mol Brain 2016, 9, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, G.; et al. Zbtb20 regulates the terminal differentiation of hypertrophic chondrocytes via repression of Sox9. Development 2015, 142, 385–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doeppner, T.R.; et al. Zbtb20 Regulates Developmental Neurogenesis in the Olfactory Bulb and Gliogenesis After Adult Brain Injury. Mol Neurobiol 2019, 56, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros de Araújo, J.A.; et al. ZBTB20 is crucial for the specification of a subset of callosal projection neurons and astrocytes in the mammalian neocortex. 2021, 148.

- Wang, Q.; et al. Zinc finger protein ZBTB20 expression is increased in hepatocellular carcinoma and associated with poor prognosis. BMC Cancer 2011, 11, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- To, J.C.; et al. ZBTB20 regulates WNT/CTNNB1 signalling pathway by suppressing PPARG during hepatocellular carcinoma tumourigenesis. JHEP Rep 2021, 3, 100223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, M. and E. De Schutter, Models of Purkinje cell dendritic tree selection during early cerebellar development. 2023; 19, e1011320. [Google Scholar]

- Kapfhammer, J.P. ; Cellular and molecular control of dendritic growth and development of cerebellar Purkinje cells. Prog Histochem Cytochem 2004, 39, 131–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuntz, H.; et al. One rule to grow them all: a general theory of neuronal branching and its practical application. PLoS Comput Biol 2010, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armengol, J.A. and C. Sotelo, Early dendritic development of Purkinje cells in the rat cerebellum. A light and electron microscopic study using axonal tracing in ‘in vitro’ slices. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 1991, 64, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; et al. Dendritic morphogenesis of cerebellar Purkinje cells through extension and retraction revealed by long-term tracking of living cells in vitro. Neuroscience 2006, 141, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeo, Y.H.; et al. GluD2- and Cbln1-mediated competitive interactions shape the dendritic arbors of cerebellar Purkinje cells. Neuron 2021, 109, 629–644.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, J.E.; C. K. Henrikson, and J.A. Grieshaber, A quantitative study of synapses on motor neuron dendritic growth cones in developing mouse spinal cord. J Cell Biol 1974, 60, 664–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosman, L.W. and A. Konnerth, Activity-dependent plasticity of developing climbing fiber-Purkinje cell synapses. Neuroscience 2009, 162, 612–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cline, H. and K. Haas, The regulation of dendritic arbor development and plasticity by glutamatergic synaptic input: a review of the synaptotrophic hypothesis. J Physiol 2008, 586, 1509–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, K.; et al. Cbln1 is a ligand for an orphan glutamate receptor delta2, a bidirectional synapse organizer. Science 2010, 328, 363–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uemura, T.; et al. Trans-synaptic interaction of GluRdelta2 and Neurexin through Cbln1 mediates synapse formation in the cerebellum. Cell 2010, 141, 1068–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, V. and A.J. Baines, Spectrin and ankyrin-based pathways: metazoan inventions for integrating cells into tissues. Physiol Rev 2001, 81, 1353–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; et al. β-III spectrin is critical for development of purkinje cell dendritic tree and spine morphogenesis. J Neurosci 2011, 31, 16581–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, E.M.; et al. Loss of beta-III spectrin leads to Purkinje cell dysfunction recapitulating the behavior and neuropathology of spinocerebellar ataxia type 5 in humans. J Neurosci 2010, 30, 4857–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; et al. Reduction of fetuin-A levels contributes to impairment of Purkinje cells in cerebella of patients with Parkinson’s disease. BMB Rep 2023, 56, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekol Abebe, E.; et al. The structure, biosynthesis, and biological roles of fetuin-A: A review. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 945287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsas, J.; et al. Fetuin-a in the developing brain. Dev Neurobiol 2013, 73, 354–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; et al. Peripheral administration of fetuin-A attenuates early cerebral ischemic injury in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2010, 30, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Z. and X.H. Ma, ZBTB20 is essential for cochlear maturation and hearing in mice. 2023; 120, e2220867120. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, A.J.; et al. ZBTB20 regulates nociception and pain sensation by modulating TRP channel expression in nociceptive sensory neurons. Nat Commun 2014, 5, 4984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.A.; et al. Neurodevelopmental disorder-associated ZBTB20 gene variants affect dendritic and synaptic structure. 2018, 13, e0203760.

- Nielsen, J.V.; et al. Zbtb20-induced CA1 pyramidal neuron development and area enlargement in the cerebral midline cortex of mice. Cereb Cortex 2010, 20, 1904–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alby, C.; et al. Novel de novo ZBTB20 mutations in three cases with Primrose syndrome and constant corpus callosum anomalies. 2018, 176, 1091–1098.

- Wang, Y.; et al. ZBTB20-AS1 promoted Alzheimer’s disease progression through ZBTB20/GSK-3β/Tau pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2023, 640, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulbranson, D.R.; et al. Phenotypic Differences between the Alzheimer’s Disease-Related hAPP-J20 Model and Heterozygous Zbtb20 Knock-Out Mice. 2021, 8.

- Lee, S. and S.H. Kim, Genetic Diagnosis in Neonatal Encephalopathy With Hypoxic Brain Damage Using Targeted Gene Panel Sequencing. 2024; 20, 519–528. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, E.H.; et al. Regulation of archicortical arealization by the transcription factor Zbtb20. Hippocampus 2012, 22, 2144–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).