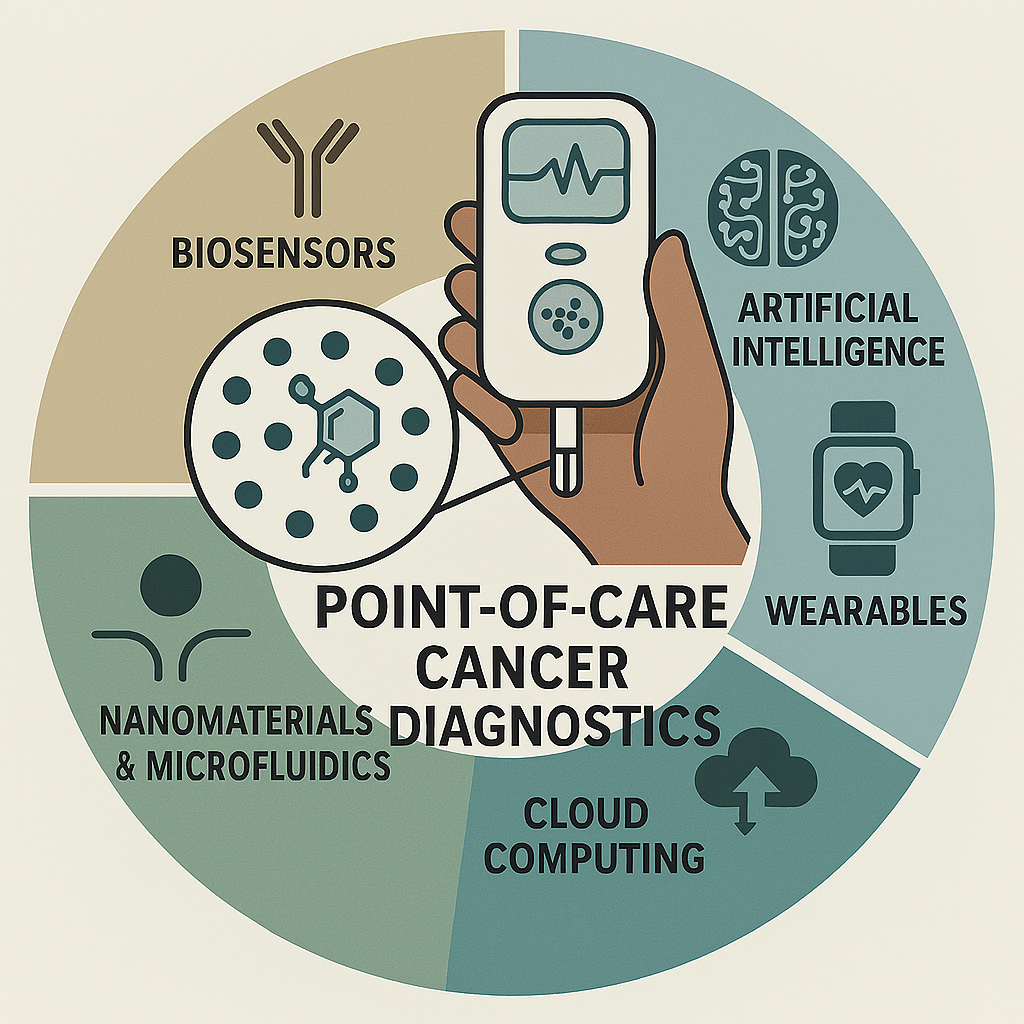

INTRODUCTION

Early detection remains a cornerstone in the effective management of cancer, with timely diagnosis correlating strongly with enhanced survival rates and improved therapeutic outcomes [

1,

2]. When malignancies are identified at an initial stage, treatment regimens tend to be less invasive, more cost-effective, and more successful in arresting disease progression [

3]. This paradigm underscores the clinical value of diagnostic tools that can reliably identify cancer biomarkers before symptomatic onset or metastatic spread.

Despite this clinical imperative, conventional diagnostic approaches such as imaging, histopathological examinations, and molecular assays often present considerable limitations [

4,

5]. These methods typically require centralised laboratory infrastructure, trained personnel, and complex instrumentation, which collectively contribute to high operational costs and extended processing times. As a result, diagnostic access remains unevenly distributed, particularly in low-resource or decentralised settings [

6,

7]. In such contexts, delays in diagnosis can lead to missed therapeutic windows, poorer prognoses, and increased healthcare burdens.

These challenges underscore the need for more agile, affordable, and patient-centric diagnostic models [

8]. The ideal solution would combine clinical accuracy with operational simplicity, enabling timely decision-making at or near the point of care. Such models must also be scalable, adaptable to diverse healthcare environments, and capable of integrating with digital health ecosystems to support longitudinal monitoring and data-driven interventions [

9,

10].

In this context, point-of-care (POC) diagnostic technologies have gained substantial traction, offering decentralised testing capabilities that reduce turnaround times and extend diagnostic reach beyond traditional laboratory confines [

11,

12]. By enabling real-time analysis of biological samples, often with minimal sample preparation, POC systems embody the potential to bring diagnostics closer to the patient, fostering early intervention and more equitable healthcare delivery [

13,

14]. POC utility is especially relevant in rural, remote, and underserved populations, where conventional diagnostics can present logistical or economic challenges [

15,

16].

Advances in next-generation biosensor platforms are instrumental to this shift. Through the integration of nanomaterials, microfluidics, and bio-recognition elements, these technologies are redefining the performance benchmarks of POC diagnostics [

17,

18]. Nanostructured surfaces and engineered transducers have enabled unprecedented sensitivity and specificity, while innovations in device miniaturisation and wireless connectivity have enhanced portability and user-friendliness [

19,

20]. Moreover, the ability to multiplex, detecting multiple biomarkers simultaneously, offers a powerful avenue for comprehensive cancer profiling in a single test.

Enhanced sensitivity, portability, and multiplexing capabilities position these biosensors at the forefront of future-facing cancer diagnostic strategies, paving the way for broader clinical adoption and improved patient outcomes [

21,

22]. As digital health platforms continue to evolve, the convergence of biosensing technologies with mobile interfaces, cloud-based analytics, and AI-driven decision support systems promises to further decentralise cancer diagnostics and transform the landscape of personalised oncology [

23,

24].

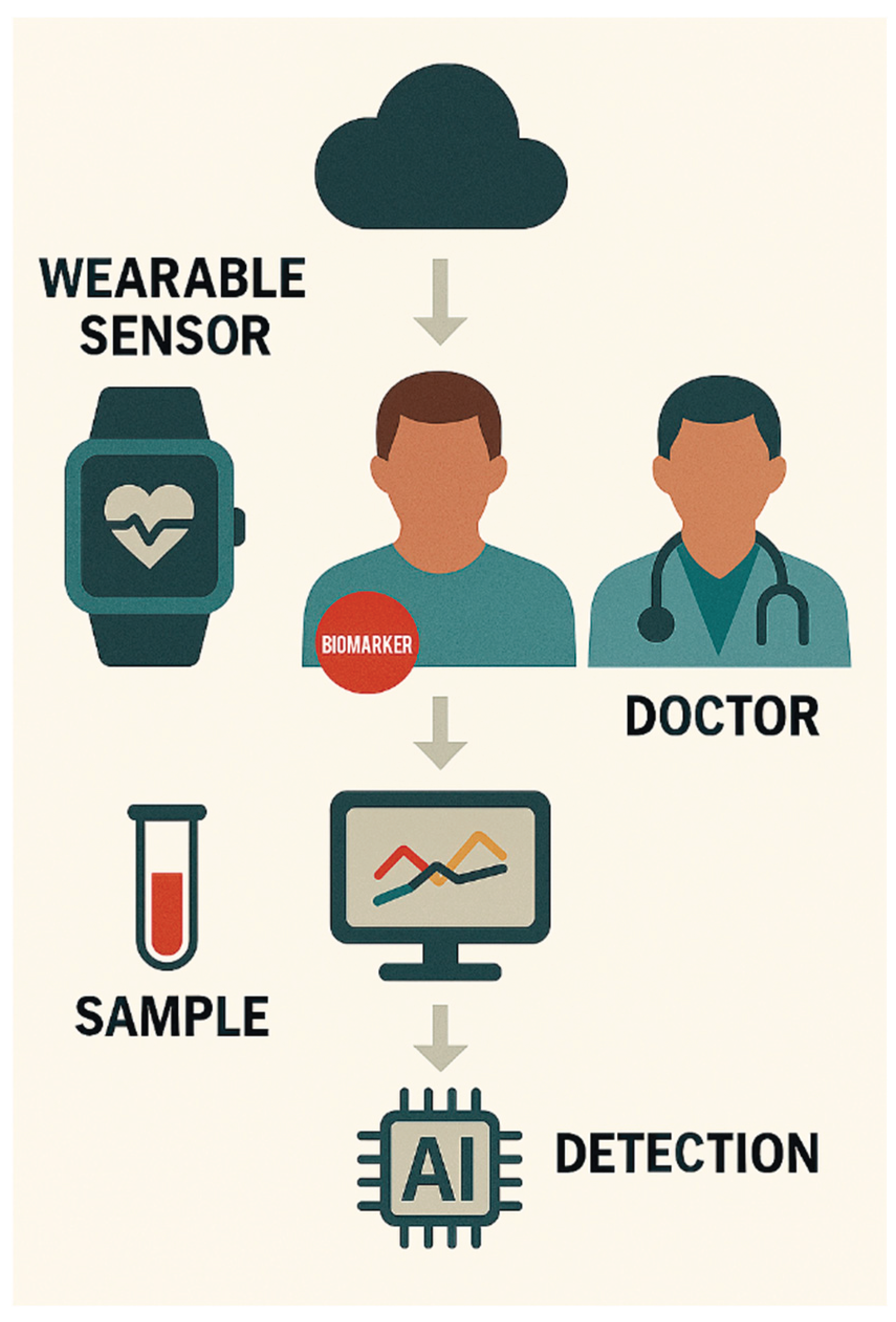

DIGITAL HEALTH INTEGRATION AND DATA-DRIVEN ONCOLOGY DIAGMOSTICS

The integration of biosensor platforms with digital health technologies marks a transformative leap in decentralised cancer diagnostics [

25]. By coupling point-of-care (POC) biosensors with mobile health (mHealth) applications, cloud-based data storage, and artificial intelligence (AI)-driven analytics, clinicians can access real-time diagnostic insights, facilitate remote monitoring, and support longitudinal patient management [

26].

Digital interfaces enable seamless data transmission from biosensor devices to electronic health records (EHRs), enhancing clinical decision-making and enabling population-level surveillance of cancer biomarkers [

27]. This interoperability is particularly valuable in resource-limited settings, where specialist access may be constrained and diagnostic delays can compromise outcomes [

28].

AI algorithms trained on large datasets can assist in pattern recognition, risk stratification, and predictive modelling, thereby augmenting the diagnostic value of biosensor outputs [

29]. Machine learning techniques have demonstrated promise in distinguishing malignant from benign profiles, identifying early-stage disease, and even forecasting treatment response based on biomarker dynamics [

30].

Furthermore, digital dashboards and mobile platforms empower patients with greater agency over their health data, fostering engagement and adherence to follow-up protocols [

31]. This patient-centric model aligns with the broader goals of precision oncology, where timely, tailored interventions are guided by continuous data streams rather than episodic clinical encounters [

32].

As biosensor technologies evolve, their integration with secure, scalable digital ecosystems will be critical to ensuring diagnostic equity, clinical utility, and sustainable implementation across diverse healthcare landscapes [

25].

MICROFABRICATION AND DEVICE MINIATURISATION FOR DEPLOYABLE CANCER DIAGNOSTICS

The integration of nanomaterials into biosensor platforms has catalysed a parallel evolution in device architecture, particularly in the realm of microfabrication and miniaturisation. These engineering advances are critical to translating laboratory-grade diagnostics into portable, user-friendly formats suitable for POC deployment [

17]. By reducing device footprint while preserving analytical performance, microfabricated biosensors enable decentralised cancer screening in both clinical and non-clinical environments [

33].

Microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) and lab-on-a-chip (LOC) technologies exemplify this shift. These platforms incorporate fluidic channels, sensing modules, and signal processors into compact substrates, often fabricated using photolithography, soft lithography, or 3D printing techniques [

34]. Such integration supports automated sample handling, multiplexed detection, and rapid readouts, thereby streamlining workflows and reducing operator dependency [

35].

Miniaturised biosensors also benefit from reduced reagent consumption and enhanced thermal and chemical stability, which are advantageous for field-based diagnostics and resource-limited settings [

36]. When paired with low-power electronics and wireless communication modules, these devices can transmit diagnostic data to cloud-based platforms or mobile interfaces, facilitating remote consultation and longitudinal patient tracking [

37].

Importantly, the convergence of microfabrication with wearable formats, such as epidermal patches, microneedle arrays, and flexible substrates, opens new avenues for continuous cancer biomarker monitoring [

38]. These innovations allow for non-invasive sampling of interstitial fluid, sweat, or saliva, expanding the diagnostic repertoire beyond blood-based assays [

39].

As biosensor miniaturisation continues to advance, emphasis must be placed on ensuring robustness, reproducibility, and regulatory compliance. Standardisation of fabrication protocols and validation across diverse patient cohorts will be essential to support clinical adoption and scale-up for global health applications [

40].

CONNECTED DIAGNOSTICS AND INTELLIGENT DECISION SUPPORT IN PRECISION ONCOLOGY

The convergence of biosensor innovation with digital health infrastructure has opened new avenues for real-time, connected cancer diagnostics [

25]. By embedding wireless communication modules, data analytics, and cloud-based platforms into point-of-care (POC) biosensing devices, developers are redefining how diagnostic information is captured, transmitted, and interpreted across clinical and remote settings [

37,

41]. This shift from isolated testing to integrated diagnostic ecosystems marks a pivotal advancement in decentralised oncology care.

Wireless-enabled biosensors facilitate seamless data transfer to electronic health records (EHRs), enabling timely clinical decisions whilst reducing the dependency on physical reporting or laboratory-based verification [

42]. This interoperability enhances the continuity of care, particularly for patients requiring longitudinal monitoring or telemedicine support [

43]. In rural or underserved regions, such connectivity can bridge diagnostic gaps and reduce delays in treatment initiation [

44].

Moreover, mobile applications interfacing with biosensors offer user-centric dashboards and instant feedback, empowering patients to participate more actively in their health management [

45]. These platforms often include alert systems, trend visualisation, and personalised recommendations, fostering a more engaged and informed patient population [

46]. Such features are especially valuable in chronic cancer surveillance, where frequent biomarker tracking is essential.

Machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms are increasingly employed to interpret biosensor outputs, improving diagnostic precision by identifying complex patterns or subtle biomarker fluctuations that might elude manual interpretation [

29,

47]. These tools support risk stratification, predictive modelling, and even automated triage, all of which are invaluable in cancer care pathways [

48]. For example, AI-enhanced biosensors can differentiate between benign and malignant signatures with high accuracy, reducing false positives and streamlining referral processes [

49,

50].

Importantly, digital integration also supports data aggregation for epidemiological surveillance and population-level analytics [

51]. Trends in biomarker prevalence, regional incidence, and diagnostic performance can be monitored in near real-time, thereby informing public health strategies and resource allocation [

52,

53]. This capability is particularly relevant in outbreak scenarios or screening campaigns, where rapid data synthesis can guide targeted interventions [

54,

55].

Collectively, the pairing of next-generation biosensors with digital health platforms holds the potential to create a closed-loop diagnostic network that is not only faster and more accessible, but also adaptive, intelligent, and aligned with the evolving demands of precision oncology [

56]. As these systems mature, emphasis must be placed on data security, regulatory compliance, and equitable access to ensure that technological innovation translates into meaningful clinical impact [

57,

58].

PATHWAYS TO SCALABLE IMPLEMENTATION AND GLOBAL HEALTH INTEGRATION

While the barriers to clinical translation of POC biosensors are multifaceted, emerging strategies across research, policy, and industry sectors offer promising avenues for scalable deployment in cancer diagnostics. Addressing these challenges requires a systems-level approach that harmonises technological innovation with regulatory foresight, economic feasibility, and infrastructure development.

One critical enabler is the development of standardised validation protocols tailored to hybrid biosensor platforms [

27]. These frameworks must account for the unique characteristics of nanomaterial-enhanced, digitally integrated devices, including their modularity, disposability, and software dependencies. International regulatory bodies such as the FDA, EMA, and WHO are increasingly recognising the need for adaptive guidelines that support rapid yet rigorous evaluation of POC technologies [

60].

Public–private partnerships and innovation accelerators have also emerged as key drivers of biosensor scale-up [

61]. By fostering collaboration between academic institutions, biotech startups, and global health organisations, these initiatives help bridge the gap between bench science and bedside application [

62]. Funding mechanisms that support pilot deployment in low-resource settings can further catalyse adoption, especially when paired with local capacity-building efforts [

63].

To address manufacturing scalability, researchers are exploring low-cost fabrication techniques such as roll-to-roll printing, inkjet deposition, and biodegradable substrates [

64]. These methods reduce reliance on cleanroom infrastructure and enable distributed production models, which are particularly advantageous for decentralised healthcare systems [

65].

Infrastructure readiness can be bolstered through mobile health units, solar-powered diagnostic kiosks, and offline-compatible biosensor interfaces. These adaptations ensure functionality in settings with intermittent power or connectivity, thereby expanding the reach of cancer diagnostics to underserved populations [

66]. Training programs for frontline health workers and community-based screening initiatives further enhance operational sustainability [

67].

Finally, the integration of AI-driven decision support and cloud-based analytics must be accompanied by robust data governance frameworks. Ensuring patient privacy, data interoperability, and ethical use of predictive algorithms is essential to building trust and enabling widespread adoption [

68].

By aligning biosensor innovation with scalable implementation strategies, the vision of decentralised, equitable cancer diagnostics becomes increasingly attainable. These efforts not only advance precision oncology but also contribute to broader goals of global health equity and digital transformation in medicine.

IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGIES FOR LOW-RESOURCE AND DECENTRALISED SETTINGS

The promise of POC biosensors in cancer diagnostics hinges not only on technological innovation but also on their practical deployment in diverse healthcare ecosystems. In low-resource and decentralised settings, where conventional diagnostic infrastructure is limited or absent, tailored implementation strategies are essential to ensure equitable access and sustained impact [

69].

One foundational strategy involves the development of context-sensitive design principles. Biosensors intended for rural clinics, mobile health units, or community outreach programs must be rugged, battery-efficient, and operable without continuous internet connectivity [

70]. Environmental resilience, such as tolerance to humidity, temperature fluctuations, and dust, is critical for maintaining diagnostic fidelity in field conditions [

71].

Task-shifting and decentralised training models also play a pivotal role. By equipping community health workers and non-specialist personnel with intuitive biosensor interfaces and decision-support tools, diagnostic capacity can be expanded without overburdening tertiary care centres [

72]. Training modules should be culturally adapted, language-accessible, and reinforced through digital platforms or peer networks [

73].

To overcome logistical barriers, mobile diagnostic hubs and telepathology integration have shown promise. These models allow biosensor data to be collected locally and interpreted remotely by specialists, bridging geographic gaps in oncology expertise [

74]. In some pilot programs, biosensor-equipped vans or drones have been used to reach remote populations, demonstrating feasibility for mass screening campaigns [

75].

Public health partnerships and community engagement are equally vital. Co-designing deployment strategies with local stakeholders ensures alignment with cultural norms, healthcare priorities, and trust-building efforts [

76]. Such participatory approaches can improve adoption rates and foster long-term sustainability, especially when paired with government support or NGO-led initiatives [

77].

Finally, cost-sharing models, such as tiered pricing, donor subsidies, or integration into national insurance schemes, can help mitigate affordability constraints [

78]. These financial mechanisms are particularly important for scaling biosensor access in low- and middle-income countries, where out-of-pocket diagnostic expenses often deter early cancer detection [

79].

By embedding biosensor technologies within adaptive, community-driven frameworks, the decentralisation of cancer diagnostics becomes not only technically feasible but socially and economically viable. These strategies lay the groundwork for a more inclusive diagnostic landscape, especially one that transcends geographic boundaries and empowers frontline healthcare delivery.

ETHICAL, LEGAL, AND DATA COVERNANCE CONSIDERATIONS IN DECEMTRALISED CANCER DIAGMOSTICS

The decentralisation of cancer diagnostics through biosensor technologies and digital health platforms introduces a complex web of ethical, legal, and data governance challenges. These considerations are not peripheral, they are foundational to ensuring trust, equity, and accountability in the deployment of POC systems across diverse populations and jurisdictions.

ETHICAL IMPERATIVES: EQUITY, AUTONOMY, AND CONSENT

At the heart of ethical deployment lies the principle of health equity. Decentralised diagnostics must not exacerbate existing disparities in cancer outcomes; rather, they should be designed to reduce diagnostic latency and improve access for historically underserved populations [

80]. This includes ensuring that biosensor algorithms are trained on diverse datasets to avoid racial, gender, or socioeconomic bias in diagnostic outputs [

81].

Informed consent becomes more nuanced in decentralised settings. Patients may interact with biosensors outside traditional clinical environments via mobile apps, kiosks, or community health workers, raising questions about how consent is obtained, documented, and understood [

82]. Simplified, multilingual consent protocols and digital literacy support are essential to uphold patient autonomy [

83].

LEGAL AND REGULATORY FRAMEWORKS

The legal landscape for POC biosensors is rapidly evolving. Devices that generate diagnostic outputs must comply with medical device regulations, which vary across regions (e.g., FDA in the U.S., TGA in Australia, CE marking in Europe) [

60,

84]. The classification of biosensors, whether as Class I, II, or III devices, determines the rigor of pre-market evaluation, post-market surveillance, and clinical validation requirements [

84].

Cross-border deployment introduces additional complexity. Biosensors integrated with cloud-based analytics or telemedicine platforms may transmit patient data across jurisdictions, triggering data sovereignty concerns and necessitating compliance with frameworks like GDPR, HIPAA, or Australia’s Privacy Act [

85]. Legal harmonisation and interoperability standards are needed to facilitate safe and lawful global deployment [

86].

DATA GOVERNANCE AND CYBERSECURITY

Decentralised diagnostics generate vast amounts of real-time health data, often stored or processed on mobile devices, edge servers, or cloud platforms. Robust data governance protocols must address data ownership, access rights, and secondary use for research or algorithm refinement [

87]. Patients should retain control over their data, with transparent opt-in mechanisms for data sharing [

88].

Cybersecurity is paramount. Biosensors and associated apps are vulnerable to hacking, spoofing, and data breaches, which could compromise patient privacy or lead to erroneous clinical decisions [

89]. End-to-end encryption, biometric authentication, and regular security audits are essential safeguards, especially in remote or low-connectivity environments [

90].

ETHICAL AI and ALGORITHMETIC TRANSPARENCY

As biosensors increasingly rely on AI-driven analytics, ethical scrutiny of algorithmic decision-making becomes critical. Black-box models that lack explainability may undermine clinician trust or patient understanding [

91]. Regulatory bodies and developers must prioritise algorithmic transparency, bias auditing, and human-in-the-loop systems to ensure responsible AI integration [

92].

Moreover, the use of predictive analytics, such as risk stratification or early warning scores, raises ethical questions about psychological impact, false positives, and clinical accountability. Clear guidelines are needed to delineate the role of AI in diagnostic decision-making and to ensure that biosensor outputs are interpreted within appropriate clinical contexts [

93].

AI-ENHANCED BIOSENSING AND PREDICTIVE ANALYTICS

AI integration into biosensor platforms is transforming raw signal acquisition into actionable clinical intelligence. Machine learning algorithms can be trained to detect subtle biomarker fluctuations, classify cancer subtypes, and even predict disease progression based on longitudinal biosensor data [

95]. Deep learning models have shown promise in enhancing signal-to-noise ratios, compensating for environmental variability, and improving diagnostic accuracy in real-world settings [

96].

Moreover, AI-powered biosensors can support adaptive calibration, where the device self-adjusts based on patient-specific parameters or ambient conditions. This capability is particularly valuable in decentralised environments, where standardisation is difficult and variability is high [

29,

97,

98].

WEARABLE BIOSENSORS FOR CONTINOUS CANCER MONITORING

Wearable biosensors, such as epidermal patches, smart textiles, and microneedle arrays, are redefining the temporal dimension of cancer diagnostics. Unlike episodic testing [

99], these platforms enable continuous monitoring of biomarkers such as circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA), cytokines, or metabolic signatures [

100]. This real-time data stream supports early relapse detection, treatment response assessment, and dynamic risk stratification [

101].

Recent advances in flexible electronics, biocompatible substrates, and wireless telemetry have made wearable biosensors more comfortable, discreet, and clinically robust. Integration with smartphones or cloud dashboards allows patients and clinicians to visualise trends, receive alerts, and coordinate care remotely [

102,

103].

MODULAR AND RECONFIGURABLE BIOSENSOR ARCHITECTURES

To support scalability and adaptability, researchers are exploring modular biosensor designs that allow components, such as transducers, recognition elements, or readout interfaces to be swapped or upgraded without redesigning the entire system [

108]. This approach facilitates rapid prototyping, customisation for different cancer types, and integration with emerging technologies [

74].

Reconfigurable platforms also support multi-use diagnostics, where a single biosensor can be repurposed for different biomarkers or diseases by changing cartridges or software modules. Such versatility is particularly valuable in low-resource settings, where device redundancy must be minimised [

109].

CLINICAL VALIDATION AND TRANSLATIONAL READINESS OF BIOSENSOR TECHNOLOGIES

The successful integration of POC biosensors into cancer diagnostics hinges on rigorous clinical validation and translational alignment. While many platforms demonstrate promising analytical performance in preclinical studies, their journey to clinical utility requires systematic evaluation across diverse patient populations, biological matrices, and healthcare settings [

110].

MULTI-PHASE VALIDATION FRAMEWORKS

Clinical validation of biosensors typically follows a multi-phase trajectory, beginning with analytical validation, assessing sensitivity, specificity, reproducibility, and limit of detection under controlled conditions. This is followed by clinical performance validation, where biosensor outputs are benchmarked against gold-standard diagnostics such as immunoassays, PCR, or imaging modalities [

111]. Comparative studies must account for disease heterogeneity, comorbidities, and demographic variability to ensure generalisability [

112].

Prospective cohort studies and randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are increasingly employed to evaluate biosensor efficacy in real-world workflows. These trials assess not only diagnostic accuracy but also clinical impact, such as time-to-treatment, patient outcomes, and cost-effectiveness [

113]. Inclusion of diverse clinical endpoints strengthens the case for regulatory approval and reimbursement eligibility [

110].

BIOLOGICAL MATRIX CHALLENGES AND SAMPLE DIVERSITY

Cancer biomarkers are often present in low concentrations and distributed across varied biological fluids, blood, saliva, urine, interstitial fluid, each with unique physicochemical properties. Biosensors must demonstrate matrix compatibility, maintaining performance across these sample types without interference from endogenous substances or environmental contaminants [

114]. Validation protocols should include stress testing under different pH, temperature, and viscosity conditions [

115].

Moreover, biosensors designed for liquid biopsy applications, such as (ctDNA), exosomes, or circulating tumour cells (CTCs), require ultra-sensitive detection thresholds and robust signal discrimination to avoid false positives or negatives [

116]. These platforms must be validated using clinically annotated biobanks and longitudinal sample sets to capture disease dynamics [

110].

CLINICAL WORKFLOW INTEGRATION AND USER ACCEPTANCE

Beyond analytical metrics, biosensors must integrate seamlessly into clinical workflows. This includes ease of use, turnaround time, data interoperability, and user training requirements [

117]. Devices that require minimal calibration, offer intuitive interfaces, and provide automated result interpretation are more likely to be adopted by frontline clinicians and community health workers [

118].

Human factors engineering plays a pivotal role in biosensor design. Usability studies should assess cognitive load, error rates, and user satisfaction across different operator profiles, from oncologists to nurses to lay users [

119]. Feedback loops between developers and end-users can accelerate iterative refinement and improve translational fit [

120].

REGULATORY ALIGNMENT AND POST-MARKET SURVEILLANCE

Regulatory approval is a critical milestone in biosensor translation. Agencies such as the FDA, EMA, and TGA require comprehensive documentation of device safety, efficacy, and manufacturing quality [

121]. Biosensors that incorporate software components, such as AI algorithms or cloud analytics, must also comply with software as a medical device (SaMD) regulations and cybersecurity standards [

122].

Post-market surveillance mechanisms, including real-world evidence (RWE) collection and adverse event reporting, are essential to monitor biosensor performance over time. These data streams can inform device updates, support label expansion, and guide clinical guidelines for biosensor use in oncology care [

123].

GLOBAL HEALTH EQUITY AND POLICY ALIGNMENT IN BIOSENSOR DEPLOYMENT

The POC biosensors in cancer diagnostics is not merely technological, it is profoundly humanitarian. To realise the full impact, biosensor platforms must be designed and deployed with a clear commitment to global health equity, ensuring accessibility, affordability, and cultural relevance across low-resource and underserved settings.

BRIDGING THE URBAN-RURAL DIAGNOSTIC DIVIDE

Cancer outcomes are often dictated by geography. In many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), rural populations face significant barriers to early diagnosis due to limited laboratory infrastructure, specialist availability, and transportation logistics [

124]. POC biosensors offer a transformative solution by enabling on-site testing, reducing diagnostic delays, and facilitating task-shifting to community health workers.

However, successful deployment requires contextual adaptation. Devices must be ruggedised for harsh environments, operate on battery or solar power, and support offline functionality where internet access is intermittent [

125]. Local manufacturing and supply chain integration can further reduce costs and improve sustainability [

126].

POLICY FRAMEWORKS AND HEALTH SYSTEM INTEGRATION

For biosensors to scale equitably, they must be embedded within national cancer control strategies and supported by regulatory harmonisation. Ministries of health and global agencies such as WHO, PATH, and FIND play a pivotal role in establishing technical standards, procurement guidelines, and training protocols [

127].

Public-private partnerships (PPPs) can accelerate biosensor adoption by aligning commercial innovation with public health goals. These collaborations may include subsidised pricing models, shared data platforms, and co-development of culturally tailored diagnostic algorithms [

128].

Moreover, biosensor data must be interoperable with EHRs and national cancer registries, enabling real-time surveillance, epidemiological mapping, and policy feedback loops [

128]. Privacy safeguards and ethical governance are essential to protect patient data and maintain public trust [

129,

130].

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT AND PATIENT-CENTRIC DESIGN

Equity is not achieved through technology alone; it requires community ownership. Biosensor initiatives must engage local stakeholders from the outset, including patients, caregivers, traditional healers, and civil society organisations [

131]. Participatory design workshops, pilot studies, and feedback sessions can surface latent needs and foster trust.

Health literacy campaigns are critical to ensure informed use and interpretation of biosensor results. These campaigns should leverage local languages, visual aids, and culturally resonant narratives to demystify cancer diagnostics and reduce stigma [

132]. Mobile health (mHealth) platforms and SMS-based reminders can reinforce adherence and follow-up care [

133].

FINANCING MODELS AND SUSTAINABLE ACCESS

Affordability remains a key barrier to biosensor uptake. Innovative financing models, such as microinsurance, results-based financing, and tiered pricing strategies can expand access among marginalised populations [

134]. Donor agencies, philanthropic foundations, and impact investors have a role to play in de-risking early deployment and catalysing market entry [

135].

Cost-effectiveness analyses should be embedded in biosensor development pipelines to demonstrate value-for-money and inform reimbursement decisions. These analyses must account for indirect benefits such as reduced travel costs, earlier treatment initiation, and improved survival outcomes [

136].

PATIENT-CENTRIC DESIGN AND DIGITAL HEALTH INTEGRATION

The decentralisation of cancer diagnostics must be anchored in human-centred innovation. Biosensor technologies that prioritise patient experience, usability, and digital connectivity are more likely to achieve sustained adoption and meaningful health outcomes. This section explores how design principles and digital ecosystems converge to empower patients and personalise care.

USER EXPERIENCE (UX) AND HUMAN-CENTRED DESIGN

Effective biosensor deployment begins with understanding the lived experience of patients. Devices must be intuitive, non-invasive, and emotionally reassuring, especially in oncology, where anxiety and uncertainty are prevalent [

137]. Form factor, interface design, and feedback mechanisms should be co-developed with patients through iterative prototyping and usability testing.

Key design features include:

Minimal sample requirements (e.g., finger-prick blood, saliva swabs)

Real-time feedback with visual cues or haptic alerts

Multilingual interfaces and accessibility features for vision or motor impairments

Privacy-first architecture to protect sensitive health data

Empathy mapping and journey modelling can help developers anticipate pain points and tailor biosensor interactions to diverse patient profiles from tech-savvy urban dwellers to digitally naïve rural users [

138].

DIGITAL CONNECTIVITY AND CLOUD-BASED ANALYTICS

Modern biosensors increasingly integrate with mobile health (mHealth) platforms, enabling remote monitoring, data visualisation, and clinician-patient communication. These platforms can support:

Automated result interpretation using embedded AI algorithms

Longitudinal tracking of biomarker trends and treatment response

Teleconsultation triggers based on abnormal readings

Integration with wearables for multimodal health insights

Cloud-based analytics allow for real-time aggregation of biosensor data across populations, supporting epidemiological surveillance and predictive modelling. However, this requires robust cybersecurity protocols, data governance frameworks, and interoperability standards to ensure safe and seamless data flow [

139].

AI-DRIVEN DECISION SUPPORT AND PERSONALISATION

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a powerful enabler of personalised oncology care. Biosensors equipped with AI can:

Distinguish signal from noise in complex biological matrices

Predict disease progression using machine learning models trained on historical data

Recommend tailored interventions based on patient phenotype and biomarker profile

Flag anomalies for clinician review, reducing diagnostic burden

Explainable AI (XAI) is critical to ensure transparency and trust. Patients and clinicians must understand how decisions are made, especially when biosensor outputs influence treatment pathways or clinical triage [

140].

CONTINUITY OF CARE AND BEHAVIOURAL ENGAGEMENT

Biosensors not necessarily have to be isolated tools, but they can however be embedded in longitudinal care pathways. This includes:

Integration with EMRs for seamless documentation

Alerts and reminders to promote adherence and follow-up

Gamification elements to encourage regular use and health engagement

Peer support features to foster community and reduce isolation

Behavioural science can inform biosensor deployment strategies, leveraging nudges, incentives, and social proof to drive sustained engagement. For example, biosensors that provide positive reinforcement or progress tracking can motivate patients to stay proactive in their care journey [

141].

FUTURE DIRECTIONS AND CONVERGENCE TRENDS IN BIOSENSOR-ENABLED ONCOLOGY

As biosensor technologies mature, their convergence with adjacent fields, such as nanomedicine, organoid modeling, and precision therapeutics is reshaping the landscape of cancer diagnostics. This final section explores key trajectories that will define the next decade of decentralised oncology care.

NANOTECHNOLOGY AND MULTIMODAL BIOSENSING

Nanomaterials offer unprecedented control over biosensor sensitivity, selectivity, and miniaturisation. Innovations in quantum dots, carbon nanotubes, graphene, and plasmonic nanoparticles are enabling:

Multiplexed detection of cancer biomarkers within a single assay

Enhanced signal amplification for ultra-low concentration targets

Targeted delivery and theranostics, where diagnostic and therapeutic functions are combined

Hybrid biosensors that integrate optical, electrochemical, and magnetic modalities are emerging as powerful tools for real-time, in vivo cancer monitoring [

142]. These platforms can be embedded in wearable devices or implantable systems, offering continuous surveillance of tumour dynamics [

56].

ORGANOID-BASED VALIDATION AND PERSONALISED MODELS

Three-dimensional (3D) cell culture models, such as patient-derived organoids (PDOs) and tumour spheroids are revolutionising biosensor validation. These models better mimic the tumour microenvironment, enabling:

Functional testing of biosensor performance in physiologically relevant conditions

Personalised calibration based on individual tumour biology

Drug response prediction and biomarker discovery in tandem with biosensor readouts

Organoid-integrated biosensors may serve as ex vivo diagnostic platforms, allowing clinicians to test multiple therapeutic options and monitor biomarker evolution before initiating treatment.

PRECISION ONCOLOGY AND OMICS INTEGRATION

The future of biosensing lies in its ability to interface with multi-omics data streams, including, genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and transcriptomics. Biosensors that can detect and interpret these layers will enable:

Dynamic risk stratification and early detection of aggressive subtypes

Real-time monitoring of treatment efficacy and resistance mechanisms

Adaptive treatment algorithms powered by AI and systems biology

Integration with liquid biopsy platforms and single-cell analytics will further enhance resolution, allowing for granular insights into tumour heterogeneity and clonal evolution [

143].

INTEROPERABLE ECOSYSTEMS AND GLOBAL COLLABORATION

To scale impact, biosensor innovation must be embedded in interoperable digital ecosystems. This includes:

Open-source diagnostic frameworks for rapid deployment in LMICs

Federated learning models that protect patient privacy while enabling global AI training

Cross-border regulatory harmonisation to accelerate approval and distribution

Global consortia, such as the Cancer Moonshot, Grand Challenges Canada, and AI4Health are increasingly investing in biosensor-enabled solutions that align with universal health coverage and sustainable development goals [

144].

FUTURE DIRECTIONS AND REFERENCE FRAMEWORK

To fully realize the clinical and global potential of biosensor-enabled cancer diagnostics, the following strategic directions are proposed. Each is grounded in emerging research and practical implementation pathways.

1. Precision Engineering of Biosensors

Next-generation biosensors must evolve beyond conventional antibody-based recognition to incorporate CRISPR-Cas systems, quantum dot labeling, and synthetic biology circuits for ultra-specific detection of rare cancer biomarkers.

Example: CRISPR-based biosensors have been developed for rapid detection of EGFR mutations in lung cancer, enabling real-time monitoring of therapy resistance [

152]. This study demonstrates the use of CRISPR/Cas9 to engineer lung cancer cell lines with the EGFR T790M resistance mutation. It validates CRISPR as a precise tool for modeling therapy resistance and lays the groundwork for biosensor platforms capable of real-time mutation tracking and therapeutic response monitoring.

2. 3D Culture Validation for Biosensor Testing

Traditional 2D cell models fail to replicate tumor microenvironments. 3D spheroids, organoids, and bioprinted tissues offer physiologically relevant platforms for biosensor calibration and drug response prediction.

Published Work: Biju et al. [

153] reviewed the superiority of 3D culture models in drug screening and biosensor validation, highlighting their role in mimicking in vivo tumor architecture.

Example: Patient-derived breast cancer spheroids have been used to test biosensor sensitivity to HER2 expression gradients [

154].

3. Regulatory Alignment and Digital Compliance

To transition biosensors from lab to clinic, alignment with FDA, EMA, and TGA digital health frameworks is essential. This includes validation under Software as a Medical Device (SaMD) and Good Machine Learning Practice (GMLP) guidelines.

Example: The FDA-approved wearable biosensor for cardiac arrhythmia detection (e.g., Zio Patch) sets a precedent for oncology-focused devices [

155].

4. Global Health Pilots and Equity Models

Decentralized biosensor platforms must be tailored for low-resource settings, integrating mobile diagnostics, cloud analytics, and community health workers.

Published Frameworks: WHO’s Essential Diagnostics List and PATH’s digital health toolkits advocate for biosensor deployment in rural oncology care [

156,

157].

Example: Pilot studies in Uganda and India have tested biosensor kits for cervical cancer screening via smartphone-linked fluorescence readers [

158,

159].

5. AI-Driven Clinical Decision Support

AI must be embedded not just in signal processing but in clinical reasoning, integrating biosensor data with EHRs, genomics, and imaging to guide oncologic decisions.

Example: Deep learning models trained on biosensor outputs have predicted chemotherapy response in colorectal cancer with >85% accuracy [

160].

CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

The decentralisation of cancer diagnostics through POC biosensor technologies represents a transformative shift in how malignancies are detected, monitored, and managed across diverse healthcare landscapes. This review has highlighted the convergence of biosensor innovation with nanomaterials, microfluidics, and digital health infrastructure; each contributing to enhanced sensitivity, portability, and connectivity in diagnostic workflows.

By integrating artificial intelligence, wearable formats, and cloud-based analytics, next-generation biosensors are evolving into intelligent, patient-centric platforms capable of supporting precision oncology and longitudinal care. Their potential to bridge diagnostic gaps in low-resource settings, empower community health workers, and enable real-time clinical decision-making underscores their value not only as technological tools but as instruments of health equity.

Yet, the path to widespread adoption is not without challenges. Regulatory ambiguity, manufacturing scalability, infrastructure limitations, and ethical considerations must be addressed through interdisciplinary collaboration, policy alignment, and inclusive design. Strategic implementation frameworks, grounded in usability, affordability, and cultural relevance will be essential to ensure that biosensor technologies reach the populations who need them most.

Looking ahead, the fusion of biosensing with organoid modeling, multi-omics analytics, and AI-driven decision support promises to redefine the diagnostic paradigm. As these innovations mature, they will not only decentralise cancer diagnostics but also democratise access to early detection, personalised treatment, and data-informed care.

In sum, biosensor-enabled diagnostics are poised to become a cornerstone of future oncology, adaptive, accessible, and aligned with the global imperative for equitable health innovation.

Author Information

Corresponding Author: Victor Akpe, School of Environment and Science, Griffith University, Nathan Campus, Australia *E-mail:

v.akpe@scholarflow.co.site

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the insightful discussions and collegial support provided by peers throughout the development of this manuscript. This work was conducted without external funding or institutional support and was driven solely by a shared commitment to academic inquiry and pedagogical advancement.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aguiar-Ibáñez, R.; Mbous, Y.P.V.; Sharma, S.; Chawla, E. Assessing the Clinical, Humanistic, and Economic Impact of Early Cancer Diagnosis: A Systematic Literature Review. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1546447. [CrossRef]

- Zafar, S.; Hafeez, A.; Shah, H.; Mutiullah, I.; Ali, A.; Khan, K.; et al. Emerging Biomarkers for Early Cancer Detection and Diagnosis: Challenges, Innovations, and Clinical Perspectives.Eur. J. Med. Res. 2025, 30, 760. [CrossRef]

- Hajjar, A.; Ergun, M.A.; Alagoz, O.; Rampurwala, M. Cost-effectiveness of adjuvant paclitaxel and trastuzumab for early-stage node-negative, HER2-positive breast cancer.PLOS ONE 2019, 14(6): e0217778. [CrossRef]

- Siravegna, G.; Marsoni, S.; Siena, S.; Bardelli, A. Integrating liquid biopsies into the management of cancer. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 2019, 16, 409–418.

- Savas, I.N.; Coskun, A.The Future of Tumor Markers: Advancing Early Malignancy Detection Through Omics Technologies, Continuous Monitoring, and Personalized Reference Intervals.Biomolecules 2025, 15(7), 1011. [CrossRef]

- Bamodu, O.A.; Chung, C.-C.Cancer Care Disparities: Overcoming Barriers to Cancer Control in Low- and Middle-Income Countries.JCO Glob. Oncol. 2024, 10, e2300439. [CrossRef]

- Weigl, B.H.; Neogi, T.; McGuire, H. Point-of-Care Diagnostics in Low-Resource Settings and Their Impact on Care in the Age of the Noncommunicable and Chronic Disease Epidemic.J. Lab. Autom. 2014, 19(3), 248–257. [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.K.S.; Hossain, M.D.; Hassan, K.M.R.; Rahman, M.H.Breaking Boundaries: Revolutionizing Healthcare with Agile Methodology.World Journal of Advanced Engineering Technology and Sciences 2024, 13(2), 346–354. [CrossRef]

- Moetlhoa, B.; Nxele, S.R.; Maluleke, K.; Mathebula, E.; Marange, M.; Chilufya, M.; et al.Barriers and Enablers for Implementation of Digital-Linked Diagnostics Models at Point-of-Care in South Africa: Stakeholder Engagement. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 216. [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Manning, J.C.; Devaraj, K.; Richards-Kortum, R.R.; McFall, S.M.; Murphy, R.L.; et al. Emerging Trends in Point-of-Care Technology Development for Oncology in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2025, 11, e2500142.

- Bayuomi, M.M.; Siraj, M.M.; AlHassani, A.T.; Abunar, A.A.H.; Alahmadi, R.F.; et al.Point-of-Care Testing (POCT) and Its Impact on Turnaround Time and Patient Care: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Biomed J Sci & Tech Res. 2025, 61(5), BJSTR.MS.ID.009665.

- Applegate, T.L.; Causer, L.M.; Gowa, I.; Alternetti, N.; Anderson, L.; et al. Paving the Way for Quality Assured, Decentralised Point-of-Care Testing for Infectious Disease in Primary Care: Real World Lessons from Remote Australia. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2024, 24(3), 2403091. [CrossRef]

- Yammouri, G.; Ait Lahcen, A.AI-Reinforced Wearable Sensors and Intelligent Point-of-Care Tests.J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14(11), 1088. [CrossRef]

- Parihar, M.; Niharika, W.N.; Sahana; Biswas, R.; Dehury, B.; Mazumder, N. Point-of-Care Biosensors for Infectious Disease Diagnosis: Recent Updates and Prospects.RSC Adv. 2025, 36, D5RA03897A.

- Shephard, M.; Shephard, A.; Matthews, S.; Andrewartha, K. The Benefits and Challenges of Point-of-Care Testing in Rural and Remote Primary Care Settings in Australia. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2020, 144(11), 1372–1380. [CrossRef]

- Ofori, B.; Twum, S.; Nkansah Yeboah, S.; Ansah, F.; Amofa Nketia Sarpong, K. Towards the Development of Cost-Effective Point-of-Care Diagnostic Tools for Poverty-Related Infectious Diseases in Sub-Saharan Africa. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17198. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, F.; Guo, Y.; Xu, W. Recent Trends in Nanomaterial-Based Biosensors for Point-of-Care Testing. Front.Chem. 2020, 8, 586702. [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Kumar, R.; Acooli, A.; Chatterjee, A.; Tripathy, S.K.; et al. Transforming Nanomaterial Synthesis through Advanced Microfluidic Approaches: A Review on Accessing Unrestricted Possibilities. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8(10), 386. [CrossRef]

- Naresh, V.; Lee, N. A Review on Biosensors and Recent Development of Nanostructured Materials-Enabled Biosensors. Sensors 2021, 21(4), 1109. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Jiang, H.; Wang, X. Engineered Intelligent Electrochemical Biosensors for Portable Point-of-Care Diagnostics. Chemosensors 2025, 13(4), 146. [CrossRef]

- Saylan, Y.; Özgür, E.; Denizli, A. Recent Advances of Medical Biosensors for Clinical Applications. Med Devices Sens. 2021, 4, e10129. [CrossRef]

- Ghazizadeh, E.; Naseri, Z.; Deigner, H.-P.; Rahimi, H.; Altintas, Z. Approaches of Wearable and Implantable Biosensors Towards Developing Precision Medicine. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1390634. [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Washington, P. Non-Invasive Biosensing for Healthcare Using Artificial Intelligence: A Semi-Systematic Review. Biosensors 2024, 14(4), 183. [CrossRef]

- Flynn, C.D.; Chang, D. Artificial Intelligence in Point-of-Care Biosensing: Challenges and Opportunities. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1100. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Singh, P.K.; Chauhan, N.; Roy, S.; Tiwari, A.; Gupta, S.; et al. Emergence of Integrated Biosensing-Enabled Digital Healthcare Devices. Sensors & Diagnostics 2024, 3, D4SD00017J. [CrossRef]

- Parihar, M.; Niharika, W.N.; Sahana; Biswas, R.; Dehury, B.; Mazumder, N. Point-of-care biosensors for infectious disease diagnosis: recent updates and prospects. RSC Advances 2025, Issue 36, Article D5RA03897A. [CrossRef]

- Gruson, D.; Cobbaert, C.; Dabla, P.K.; Stankovic, S.; Homsak, E.; Kotani, K.; Assaad, R.S.; Nichols, J.H.; Gouget, B.Validation and Verification Framework and Data Integration of Biosensors and In Vitro Diagnostic Devices: A Position Statement of the IFCC Committee on Mobile Health and Bioengineering in Laboratory Medicine.Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2024, 62(5), e20231455. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Yang, W.; Zhu, W.; Yu, D.Innovative Applications and Research Advances of Bacterial Biosensors in Medicine.Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1507491. [CrossRef]

- Mpofu, K.T.; Mthunzi-Kufa, P. Recent Advances in Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Based Biosensing Technologies. IntechOpen 2025. [CrossRef]

- Al-Tashi, Q.; Saad, M.B.; Muneer, A.; et al. Machine Learning Models for the Identification of Prognostic and Predictive Cancer Biomarkers: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24(9), 7781. [CrossRef]

- Rawlings, J.; Kufuor, J. Evaluating the Impact of Mobile Health Applications on Patient Engagement and Health Management. Int. J. Med. Info. & Knowledge Insights 2025, 1(1), 4. [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.M.; Meric-Bernstam, F. The Present and Future of Precision Oncology and Tumor-Agnostic Therapeutic Approaches. The Oncologist 2025, 30(6), oyaf152. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, M.B.; Ayachit, N.H.; Aminabhavi, T.M. Biosensors and Microfluidic Biosensors: From Fabrication to Application. Biosensors 2022, 12(7), 543. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, Y.; Singh, S.P. Recent Advances in Bio-MEMS and Future Possibilities: An Overview. J. Inst. Eng. India Ser. B 2023, 104, 1377–1388. [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Hu, J.; Liu, T.; et al. A Sample-to-Answer Digital Microfluidic Multiplexed PCR System for Syndromic Pathogen Detection. Lab Chip 2025, 25(6), D4LC00704B. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wang, J.; Wu, L.; et al. Trends in Miniaturized Biosensors for Point-of-Care Testing. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2020, 122, 115701. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Hao, Y.; Luo, A.; Jiang, Y. Technologies and Applications in Wireless Biosensors for Real-Time Health Monitoring. Med-X 2024, 2, 24. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Ouaskioud, O.; Yin, X.; et al. Epidermal Wearable Biosensors for Continuous Monitoring of Biomarkers in Interstitial Fluid. Micromachines 2023, 14(7), 1452. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Fang, Y.; Chen, J. Wearable Biosensors for Non-Invasive Sweat Diagnostics. Biosensors 2021, 11(8), 245. [CrossRef]

- Docherty, N.; Macdonald, D.; Gordon, A.; et al. Maximising the Translation Potential of Electrochemical Biosensors. Chem. Commun. 2025, DOI: . [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, C.R.; Sarkar, J.L.; Pati, B.; Buyya, R.; Mohapatra, P.; Majumder, A. Mobile Cloud Computing and Wireless Sensor Networks: A Review, Integration Architecture, and Future Directions. IET Netw. 2021, 10, 141–161. [CrossRef]

- Dinh-Le, C.; Chuang, R.; Chokshi, S.; Mann, D. Wearable Health Technology and Electronic Health Record Integration: Scoping Review and Future Directions. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019, 7(9), e12861. [CrossRef]

- Alzghaibi, H. Nurses’ Perspectives on AI-Enabled Wearable Health Technologies: Opportunities and Challenges in Clinical Practice. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 799. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, B. Advanced Applications in Chronic Disease Monitoring Using IoT Mobile Sensing Device Data, Machine Learning Algorithms and Frame Theory: A Systematic Review. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1510456. [CrossRef]

- Madrid, R.E.; Ramallo, F.A.; Barraza, D.E.; Chaile, R.E. Smartphone-Based Biosensor Devices for Healthcare: Technologies, Trends, and Adoption by End-Users. Bioengineering 2022, 9(3), 101. [CrossRef]

- Munos, B.; Baker, P.C.; Bot, B.M.; et al. Mobile Health: The Power of Wearables, Sensors, and Apps to Transform Clinical Trials. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2025, doi: . [CrossRef]

- Wasilewski, T.; Kamysz, W.; Gębicki, J. AI-Assisted Detection of Biomarkers by Sensors and Biosensors for Early Diagnosis and Monitoring. Biosensors 2024, 14(7), 356. [CrossRef]

- Raji, H.; Tayyab, M.; Sui, J.; Mahmoodi, S.R.; Javanmard, M. Biosensors and Machine Learning for Enhanced Detection, Stratification, and Classification of Cells. Biomed. Microdevices 2022, 24, 26. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Liu, S.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Pu, X.; Yu, J. Accurate Classification of Benign and Malignant Breast Tumors in Ultrasound Imaging with an Enhanced Deep Learning Model.Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1526260. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zang, B.; Kong, C.; Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Yu, Y. Intelligent and Precise Auxiliary Diagnosis of Breast Tumors Using Deep Learning and Radiomics. PLOS ONE 2025, 20(6), e0320732. [CrossRef]

- Idrees, A.K.; Alhussein, D.A.; Harb, H. Energy-Efficient Multisensor Adaptive Sampling and Aggregation for Patient Monitoring in Edge Computing-Based IoHT Networks. Appl. Inform. Sci. 2023, 13(4), 610. [CrossRef]

- Magnano San Lio, R.; Barchitta, M.; Maugeri, A.; et al. Updates on Developing and Applying Biosensors for the Detection of Microorganisms, Antimicrobial Resistance Genes and Antibiotics.Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1240584. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Min, J.; Gao, W. Wearable and Implantable Electronics: Moving toward Precision Therapy. ACS Nano 2019, 13(12), 12280–12286. [CrossRef]

- Tellechea-Luzardo, J.; Stiebritz, M.T.; Carbonell, P. Transcription Factor-Based Biosensors for Screening and Dynamic Regulation. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1118702. [CrossRef]

- Tellechea-Luzardo, J.; Martín Lázaro, H.; Moreno López, R.; Carbonell, P. Sensbio: An Online Server for Biosensor Design. BMC Bioinformatics 2023, 24, 71. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhu, R.; Peng, I.; Xu, Z.; Jiang, Y. Wearable and Implantable Biosensors: Mechanisms and Applications in Closed-Loop Therapeutic Systems. J. Mater. Chem. B 2024, 12, 8577–8604. [CrossRef]

- Jaime, F.J.; Muñoz, A.; Rodríguez-Gómez, F.; Jerez-Calero, A. Strengthening Privacy and Data Security in Biomedical Microelectromechanical Systems.Sensors 2023, 23(21), 8944. [CrossRef]

- Karim, M.E. Biosensors: Ethical, Regulatory, and Legal Issues. Handbook of Cell Biosensors 2020, Springer. [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.R.; Hussain, W.L.; Shum, H.C.; Hassan, S.U. Point-of-Care Testing: A Critical Analysis of the Market and Future Trends. Front. Lab Chip Technol. 2024, 3, 1394752. [CrossRef]

- Prestedge, J.; Kaufman, C.; Williamson, D.A. Regulation and Governance for the Implementation and Management of Point-of-Care Testing in Australia: A Scoping Review. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 758. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.X.; Clegg, S.; Pollack, J. The Effect of Public–Private Partnerships on Innovation in Infrastructure Delivery. Project Manag. J. 2024, 55, 31–49. [CrossRef]

- Srivastav, A.K.; Das, P.; Srivastava, A.K. Future Trends, Innovations, and Global Collaboration. In Biotech and IoT; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 309–398. [CrossRef]

- Tumuhimbise, W.; Theuring, S.; Kaggwa, F.; Musiimenta, A. Enhancing the Implementation and Integration of mHealth Interventions in Resource-Limited Settings: A Scoping Review. Implement. Sci. 2024, 19, 72. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Abbas, N.; Ali, A. Inkjet Printing: A Viable Technology for Biosensor Fabrication. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 103. [CrossRef]

- Cagnani, G.R.; Ibáñez-Redín, G. Application of Large-Scale Fabrication Techniques for Development of Electrochemical Biosensors. In Advances in Bioelectrochemistry; Springer: Cham, 2022; pp. 91–111. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt Batista, A. Empowering Remote Healthcare with On-Premises Solar-Powered AI Units: Design and Implementation. J. Next-Gen Res. 2025, 1, 4. [CrossRef]

- Power, R.; Ussher, J.M.; Hawkey, A.; et al. Co-Designed, Culturally Tailored Cervical Screening Education with Migrant and Refugee Women in Australia: A Feasibility Study. BMC Women's Health 2022, 22, 353. [CrossRef]

- Mills, D.K.; Nestorova, G.G. Biosensor Development and Innovation in Healthcare and Medical Applications. Sensors 2023, 23, 2717. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodpour, M.; Kiasari, B.A.; Karimi, M.; et al. Paper-Based Biosensors as Point-of-Care Diagnostic Devices for the Detection of Cancers: A Review of Innovative Techniques and Clinical Applications. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1131435. [CrossRef]

- Beks, H.; Ewing, G.; Charles, J.A.; et al. Mobile Primary Health Care Clinics for Indigenous Populations: A Systematic Scoping Review. Int. J. Equity Health 2020, 19, 201. [CrossRef]

- Justino, C.I.L.; Duarte, A.C.; Rocha-Santos, T.A.P. Recent Progress in Biosensors for Environmental Monitoring: A Review. Sensors 2017, 17, 2918. [CrossRef]

- Toffner, G.; Koff, D.A.; Drossos, A.; et al. A Community-Based Task Shifting Program in 25 Remote Indigenous Communities in Nunavut, Canada. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2025, 84, 2439119. [CrossRef]

- Farsangi, S.N.; Shahraki, S.K.; Cruz, J.P.; Farokhzadian, J. Designing, Implementing, and Evaluating a Mobile App-Based Cultural Care Training Program.BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 979. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.J.; Javed, Z.; Herrera-Bravo, J.; et al. Biosensing Chips for Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment: A New Wave Towards Clinical Innovation. Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22, 354. [CrossRef]

- Warfade, T.S.; Dhoke, A.P.; Kitukale, M.D. Biosensors in Healthcare: Overcoming Challenges and Pioneering Innovations for Disease Management. World J. Biol. Pharm. Health Sci. 2025, 21, 350–358. [CrossRef]

- Brunton, G.; Thomas, J.; O’Mara-Eves, A.; et al. Narratives of Community Engagement: A Systematic Review-Derived Conceptual Framework for Public Health Interventions. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 944. [CrossRef]

- Akintobi, T.H.; Bailey, R.E.; Michener, J.L. Harnessing the Power of Community Engagement for Population Health.Prev. Chronic Dis. 2025, 22, 250189. [CrossRef]

- Feldhaus, I.; Mathauer, I.Effects of Mixed Provider Payment Systems and Aligned Cost Sharing Practices: A Structured Review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 996. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.L. The Enduring Debate Over Cost Sharing for Essential Public Health Tools. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e199810. [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois, A.; Horrill, T.; Mollison, A.; et al. Barriers to Cancer Treatment for People Experiencing Socioeconomic Disadvantage in High-Income Countries: A Scoping Review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 670. [CrossRef]

- Dankwa-Mullan, I.; Ndoh, K.; Akogo, D.; et al. Artificial Intelligence and Cancer Health Equity: Bridging the Divide or Widening the Gap. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2025, 27, 95–111. [CrossRef]

- Adesoye, T.; Katz, M.H.G.; Offodile II, A.C. Meeting Trial Participants Where They Are: Decentralized Clinical Trials as a Patient-Centered Paradigm. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2023, 19, 317. [CrossRef]

- Goldschmitt, M.; Gleim, P.; Mandelartz, S.; et al. Digitalizing Informed Consent in Healthcare: A Scoping Review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 893. [CrossRef]

- Tsyganova, I.Medical Devices: Pre-market Authorisation. TGA Medical Devices Branch, Presentation, March 2018. TGA Pre-market Guidelines.

- Bassan, S. Data Privacy Considerations for Telehealth Consumers Amid COVID-19. J. Law Biosci. 2020, 7(1), lsaa075. [CrossRef]

- Bernasconi, L.; Şen, S.; Angerame, L.; et al. Legal and Ethical Framework for Global Health Information and Biospecimen Exchange: An International Perspective. BMC Med. Ethics 2020, 21, 8. [CrossRef]

- Piasecki, J.; Dranseika, V.; Vermeulen, E. Ownership of Individual-Level Health Data, Data Sharing, and Data Governance. BMC Med. Ethics 2022, 23, 8. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, H.; Bell, E.; et al. Patient Perspectives About Decisions to Share Medical Data and Biospecimens for Research. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2(8), e199550. [CrossRef]

- Ewoh, P.; Vartiainen, T. Vulnerability to Cyberattacks and Sociotechnical Solutions for Health Care Systems: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e46904. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, S.; Cui, H.; et al. A Review of Homomorphic Encryption for Privacy-Preserving Biometrics. Sensors 2023, 23(7), 3566. [CrossRef]

- Afrihyiav, E.; Chianumba, E.C.; Forkuo, A.Y.; et al. Explainable AI in Healthcare: Visualizing Black-Box Models for Better Decision-Making. Multidiscip. Glob. Eng. 2025, 3(1), 1113–1125.

- Bouderhem, R. A Comprehensive Framework for Transparent and Explainable AI Sensors in Healthcare. Eng. Proc. 2024, 82(1), 49. [CrossRef]

- Andreoletti, M.; Haller, L.; Vayena, E.; Blasimme, A. Mapping the Ethical Landscape of Digital Biomarkers: A Scoping Review. PLOS Digit. Health 2024, 3(5), e0000519. [CrossRef]

- Yammouri, G.; Lahcen, A. A. AI-Reinforced Wearable Sensors and Intelligent Point-of-Care Tests. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14(11), 1088. [CrossRef]

- Al-Tashi, Q.; Saad, M.B.; Muneer, A.; et al. Machine Learning Models for the Identification of Prognostic and Predictive Cancer Biomarkers: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24(9), 7781. [CrossRef]

- Porr, B.; Daryanavard, S.; Bohollo, L.M.; et al. Real-Time Noise Cancellation with Deep Learning. PLoS ONE 2022, 17(11), e0277974. [CrossRef]

- Mikhail, T.J.; El Shamy, R.; Swillam, M.A.; Li, X. Enhanced Performance of On-Chip Integrated Biosensor Using Deep Learning. Opt. Quant. Electron. 2023, 55, 967. [CrossRef]

- Heikenfeld, J.; Jajack, A.; Rogers, J.; et al. Wearable sensors: modalities, challenges, and prospects. Lab on a Chip 2019, 19(2), 217–248.

- Rabiee, N.; Ahmadi, S.; Fatahi, Y.; et al. Revolutionizing Biosensing with Wearable Microneedle Patches: Innovations and Applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2025, 13(18), 251–268. [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Sun, T.; Wang, M.; et al. Multiple Time Points for Detecting Circulating Tumor DNA to Monitor the Response to Neoadjuvant Therapy in Breast Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 115. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yu, B.; Su, M.; et al. Construction of a Risk Stratification Model Integrating ctDNA to Predict Response and Survival in Neoadjuvant-Treated Breast Cancer. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 493. [CrossRef]

- Nan, X.; Wang, X.; Kang, T.; et al. Review of Flexible Wearable Sensor Devices for Biomedical Application. Micromachines 2022, 13(9), 1395. [CrossRef]

- Low, C.A. Harnessing Consumer Smartphone and Wearable Sensors for Clinical Cancer Research. npj Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 140. [CrossRef]

- Jarockyte, G.; Karabanovas, V.; Rotomskis, R.; Mobasheri, A. Multiplexed Nanobiosensors: Current Trends in Early Diagnostics. Sensors 2020, 20(23), 6890. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Islam, M.; Gupta, A. Paper-Based Multiplex Biosensors for Inexpensive Healthcare Diagnostics: A Comprehensive Review. Biomed. Microdevices 2023, 25, 17. [CrossRef]

- Shanmugasundaram, K. B.; Li, J.; Sina, A. I.; Wuethrich, A.; Trau, M. Toward Precision Oncology: SERS Microfluidic Systems for Multiplex Biomarker Analysis in Liquid Biopsy. Mater. Adv. 2022, 3(4), 1459–1471. [CrossRef]

- Shirgir, B.; Dimililer, K.; Asir, S. Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Biosensors. In Intelligent Informatics, Springer, 2024, pp. 299–315. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Xie, T.; Kang, B.; Yu, X.; Schaffter, S. W.; Schulman, R. Plug-and-Play Protein Biosensors Using Aptamer-Regulated In Vitro Transcription. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 51907. [CrossRef]

- Syed, Z. Q.; Samaraweera, S.; Wang, Z.; Krishnan, S. Colorimetric Nano-Biosensor for Low-Resource Settings: Insulin as a Model Biomarker. Sens. Diagn. 2024, 3(8), 1659–1671. [CrossRef]

- D'Alton, L.; Souto, D. E. P.; Punyadeera, C.; Abbey, B.; Voelcker, N. H.; Hogan, C.; Silva, S. M. A holistic pathway to biosensor translation. Sens. Diagn. 2024, 3, 1234–1246. https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlehtml/2024/sd/d4sd00088a.

- Karadurmus, L.; Kaya, S. I.; Ozcelikay, G.; Gumustas, M.; Uslu, B.; Ozkan, S. A. Validation Requirements in Biosensors. In Biosensors, 1st ed.; CRC Press, 2022; pp. 353–382. [CrossRef]

- Gagnier, J. J.; Morgenstern, H.; Altman, D. G.; Berlin, J.; Chang, S.; McCulloch, P.; Sun, X.; Moher, D. Consensus-Based Recommendations for Investigating Clinical Heterogeneity in Systematic Reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 106. [CrossRef]

- Rodger, M.; Ramsay, T.; Fergusson, D. Diagnostic Randomized Controlled Trials: The Final Frontier. Trials 2012, 13, 137. [CrossRef]

- Chicea, D.; Nicolae-Maranciuc, A. Metal Nanocomposites as Biosensors for Biological Fluids Analysis. Materials 2025, 18(8), 1809. [CrossRef]

- Salvo, P.; Tedeschi, L. pH Sensors, Biosensors and Systems. Chemosensors 2025, 13(3), 90. [CrossRef]

- Lyu, N.; Hassanzadeh-Barforoushi, A.; Rey Gomez, L. M.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y. SERS Biosensors for Liquid Biopsy Towards Cancer Diagnosis. Nano Convergence 2024, 11, 22. [CrossRef]

- Samson, S. Biosensors and Bioelectronics: Integrating Biomedical Technologies for Point-of-Care Diagnostics. J. Biomed. Syst. Emerg. Technol. 2023, 10(3), 170.

- Mills, D. K.; Nestorova, G. G. Biosensor Development and Innovation in Healthcare and Medical Applications. Sensors 2023, 23(5), 2717. [CrossRef]

- Or, C. K.; Holden, R. J.; Valdez, R. S. Human Factors Engineering and User-Centered Design for Mobile Health Technology. In Human-Automation Interaction, Springer, 2022, pp. 97–118. [CrossRef]

- Aw, R.; Polizzi, K. Enhancing the Performance of an In Vitro RNA Biosensor Through Iterative Design of Experiments. Biotechnol. Prog. 2025, e70005. [CrossRef]

- Makrani, M. F.; Goyal, A.; Sayeed, S. Y. A Comparative Overview of Global Regulatory Authorities: Ensuring Quality, Safety, and Efficacy in Medicines. Int. Res. J. Pharm. Med. Sci. 2025, 8(2), 150. http://irjpms.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/IRJPMS-V8N2P150Y25.pdf.

- Williams, T.; Duffy, T. Regulatory Requirements for Software, AI and Medical Devices. Flinders Digital Health Research Centre, 2024. https://blogs.flinders.edu.au/mdri-news/wp-content/uploads/sites/35/2024/12/click-here-to-view-the-slides.pdf.

- Beltran, N. Real-World Evidence in Post-Marketing Drug Surveillance. Walsh Med. Media 2025, 13(4), 508. https://www.walshmedicalmedia.com/open-access/realworld-evidence-in-postmarketing-drug-surveillance.pdf.

- Brand, N. R.; Qu, L. G.; Chao, A.; Ilbawi, A. M. Delays and Barriers to Cancer Care in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. The Oncologist 2019, 24(12), e1371–e1380. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Pérez, G. Z.; Adetunji, T. A.; Salas Noriega, F. J. L.; et al. Point-of-Care Biochemistry for Primary Healthcare in Low-Middle Income Countries: A Qualitative Inquiry. BMC Prim. Care 2024, 25, 362. [CrossRef]

- PATH Diagnostics Program. Boosting the Local Supply Security of Diagnostics in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. PATH Diagnostics Initiative, 2023. https://www.path.org/who-we-are/programs/diagnostics/boosting-local-supply-security-diagnostics.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Controlling Cancer: A Global Strategy for National Cancer Control Programmes. WHO Technical Report Series, 2023. https://www.who.int/activities/controlling-cancer.

- Davis, A. M.; Engkvist, O.; Fairclough, R. J.; Feierberg, I.; Freeman, A.; Iyer, P. Public-Private Partnerships: Compound and Data Sharing in Drug Discovery and Development. SLAS Discov. 2021, 26(5), 604–619. [CrossRef]

- Conderino, S.; Bendik, S.; Richards, T. B.; et al. The Use of Electronic Health Records to Inform Cancer Surveillance Efforts: A Scoping Review. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2022, 22, 91. [CrossRef]

- Loscalzo, J.Biosensors and Privacy: Navigating Ethical Challenges in Health Monitoring. J. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2024, 15(5), 464.

- Tembo, D.; et al. Effective Engagement and Involvement with Community Stakeholders in the Co-Production of Global Health Research. BMJ 2021, 372, n178. https://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/372/bmj.n178.full.pdf.

- Whitehead, L.; Kirk, D.; Chejor, P.; et al. Interventions, Programmes and Resources That Address Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Consumer and Carers’ Cancer Information Needs: A Mixed Methods Systematic Review. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 599. [CrossRef]

- Wiil, U. K. Editorial: mHealth and Smartphone Apps in Patient Follow-Up. Front. Med. Technol. 2025, 7, 1644384. [CrossRef]

- Chow, Q.; Ng, J. M.; Biese, K.; McCord, M. J. Technology in Microinsurance: How New Developments Affect the Work of Actuaries. Society of Actuaries, 2019. https://www.soa.org/globalassets/assets/files/resources/research-report/2019/2019-technology-microinsurance.pdf.

- Ball, R. Beyond Capital: How Philanthropy Can Advance Impact Investing. Reichstein Foundation, 2024. https://reichstein.org.au/beyond-capital-how-philanthropy-can-advance-impact-investing.

- Hawkins, N.; Grieve, R. Extrapolation of Survival Data in Cost-Effectiveness Analyses: The Need for Causal Clarity. Med. Decis. Mak. 2017, 37(3), 337–339. [CrossRef]

- Mullaney, T.; Pettersson, H.; Nyholm, T.; Stolterman, E. Thinking Beyond the Cure: A Case for Human-Centered Design in Cancer Care. Int. J. Des. 2012, 6(3), 27–39. https://www.ijdesign.org/index.php/IJDesign/article/view/1076/525.

- Ly, S.; Runacres, F.; Poon, P. Journey Mapping as a Novel Approach to Healthcare: A Qualitative Mixed Methods Study in Palliative Care. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 915. [CrossRef]

- Sarani, M.; Jahangiri, K.; Karami, M.; Honarvar, M. Enhancing Epidemic Preparedness: A Data-Driven System for Managing Respiratory Infections. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 159. [CrossRef]

- Eke, C. I.; Shuib, L. The Role of Explainability and Transparency in Fostering Trust in AI Healthcare Systems: A Systematic Literature Review, Open Issues and Potential Solutions. Neural Comput. Appl. 2025, 37, 1999–2034. [CrossRef]

- Venema, T. A. G.; Kroese, F. M.; Benjamins, J. S.; de Ridder, D. T. D. When in Doubt, Follow the Crowd? Responsiveness to Social Proof Nudges in the Absence of Clear Preferences. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1385. [CrossRef]

- Son, M. H.; Park, S. W.; Sagong, H. Y.; Jung, Y. K. Recent Advances in Electrochemical and Optical Biosensors for Cancer Biomarker Detection. BioChip J. 2023, 17, 44–67. [CrossRef]

- Mögele, T.; Hildebrand, K.; Sultan, A.; Sommer, S.; Rentschler, L.; Kling, M.; Sax, I.; Schlesner, M.; Märkl, B.; Trepel, M.; Schmutz, M.; Claus, R. Dissecting Tumor Heterogeneity by Liquid Biopsy—A Comparative Analysis of Post-Mortem Tissue and Pre-Mortem Liquid Biopsies in Solid Neoplasias. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26(15), 7614. [CrossRef]

- Bertagnolli, M. M.; Carnival, D.; Jaffee, E. M. Achieving the Goals of the Cancer Moonshot Requires Progress Against All Cancers. Cancer Discov. 2023, 13(5), 1049–1052. [CrossRef]

- Alix-Panabières, C.; Pantel, K. From Discovery to Diagnosis: A Perspective for Circulating Tumor Cells in Personalized Oncology. Cancer Discov. 2025, 15(8), OF1–OF17. [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, R.; Zhu, Y.; de Barros, N. R. Microfluidics and Organ-on-a-Chip for Disease Modeling and Drug Screening. Biosensors 2024, 14(2), 86. [CrossRef]

- Parent, C.; Melayil, K. R.; Zhou, Y.; Aubert, V.; Surdez, D.; Delattre, O.; Wilhelm, C.; Viovy, J.-L. Simple Droplet Microfluidics Platform for Drug Screening on Cancer Spheroids. Lab Chip 2023, 23(24), 4567–4579. [CrossRef]

- Althobiti, M.; Nhung, T. T. T.; Verma, S. K.; Albugami, R. R. Artificial Intelligence and Biosensors: Transforming Cancer Diagnostics. Med. Novel Technol. Devices 2025, 27, 100378. [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Niraula, D.; Gates, E. D. H.; Fu, J.; Luo, Y.; Nyflot, M. J.; Bowen, S. R.; El Naqa, I. M.; Cui, S. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Precision Oncology: Enhancing Discoverability Through Multiomics Integration. Br. J. Radiol. 2023, 96(1150), 20230211. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Vishnu, A. G. K.; Sakorikar, T.; Kamal, A. M.; Vaidya, J. S.; Pandya, H. J. Recent Advances in Biosensing Approaches for Point-of-Care Breast Cancer Diagnostics: Challenges and Future Prospects. Nanoscale Adv. 2021, 3(14), 5542–5564. [CrossRef]

- Wyatt, A.; Sartor, O.; Lozada, J.; Perrin, D. M. Circulating Tumor DNA Biomarkers in the TheraP Trial: Cabazitaxel vs Lutetium-PSMA Comparison. ASCO GU 2025 Presentation & Post Hoc Analysis. https://www.urotoday.com/video-lectures/mcrpc-treatment/video/mediaitem/4980-ctdna-biomarkers-in-therap-trial-cabazitaxel-vs-lutetium-psma-comparison-alexander-wyatt.html.

- Park, M.-Y.; Jung, M. H.; Eo, E. Y.; Kim, S.; Lee, S. H.; Lee, Y. J.; Park, J. S.; Cho, Y. J.; Chung, J. H.; Kim, C. H.; Yoon, H. I.; Lee, J. H.; Lee, C.-T. Generation of Lung Cancer Cell Lines Harboring EGFR T790M Mutation by CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Genome Editing. Oncotarget 2017, 8(22), 36331–36338. [CrossRef]

- Biju, V.; Sreenivasan, S.; Nair, R. V.; Thomas, S. Three-Dimensional Cell Culture Models in Cancer Drug Screening and Biosensor Validation: Bridging the Gap Between In Vitro and In Vivo. Biomaterials Science 2024, 12(3), 678–695.

- Huang, Y.; Burns, D. J.; Rich, B. E.; MacNeil, I. A.; Dandapat, A.; Soltani, S. M.; Myhre, S.; Sullivan, B. F.; Lange, C. A.; Furcht, L. T.; Laing, L. G. Development of a Test That Measures Real-Time HER2 Signaling Function in Live Breast Cancer Cell Lines and Primary Cells. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 199. [CrossRef]

- iRhythm Technologies, Inc. FDA 510(k) Clearance for Zio AT Wearable Cardiac Monitoring System. MedTech Dive, 2024. https://www.medtechdive.com/news/iRhythm-FDA-510k-clearance-Zio-cardiac-monitor/730680/.

- WHO Publishes New Essential Diagnostics List and Urges Countries to Prioritize Investments in Testing. WHO News Release, 2021. WHO Essential Diagnostics List Overview.

-

Boosting the Local Supply Security of Diagnostics in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. PATH, 2023. PATH’s Diagnostic Innovation Initiative.

- Kadama-Makanga, P.; Semeere, A.; Laker-Oketta, M.; et al. Usability of a Smartphone-Compatible, Confocal Micro-Endoscope for Cervical Cancer Screening in Resource-Limited Settings. BMC Women's Health 2024, 24, 483. [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, A.; Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Kanpur. Pilot-Scale Testing of Smartphone-Based Fluorescence Spectroscopic Device for Point-of-Care Diagnosis of Early Cervical Cancer. India Science, Technology & Innovation Portal, DST Project, 2022. https://www.indiascienceandtechnology.gov.in/research/pilot-scale-testing-smartphone-based-fluorescence-spectroscopic-device-point-care-diagnosis-early.

- Kumarganesh, S.; Murugesan, M.; Ganesh, C.; Santhiyakumari, N.; Thangavel, M.; Jayaram, K.; Sagayam, K. M.; Pandey, B. K.; Pandey, D. Hybrid Plasmonic Biosensors with Deep Learning for Colorectal Cancer Detection. Plasmonics 2025, 20, 4895–4909. [CrossRef]

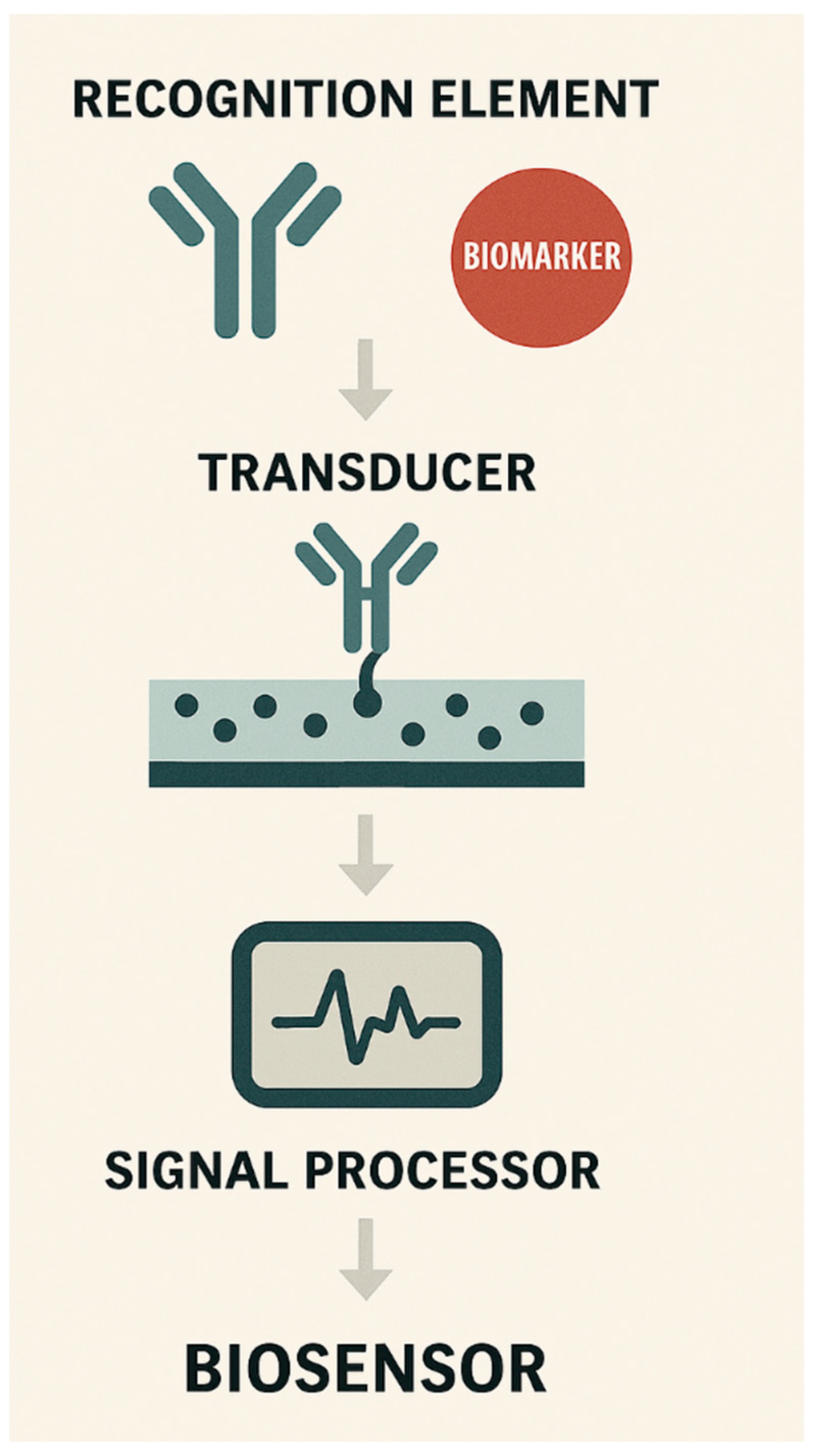

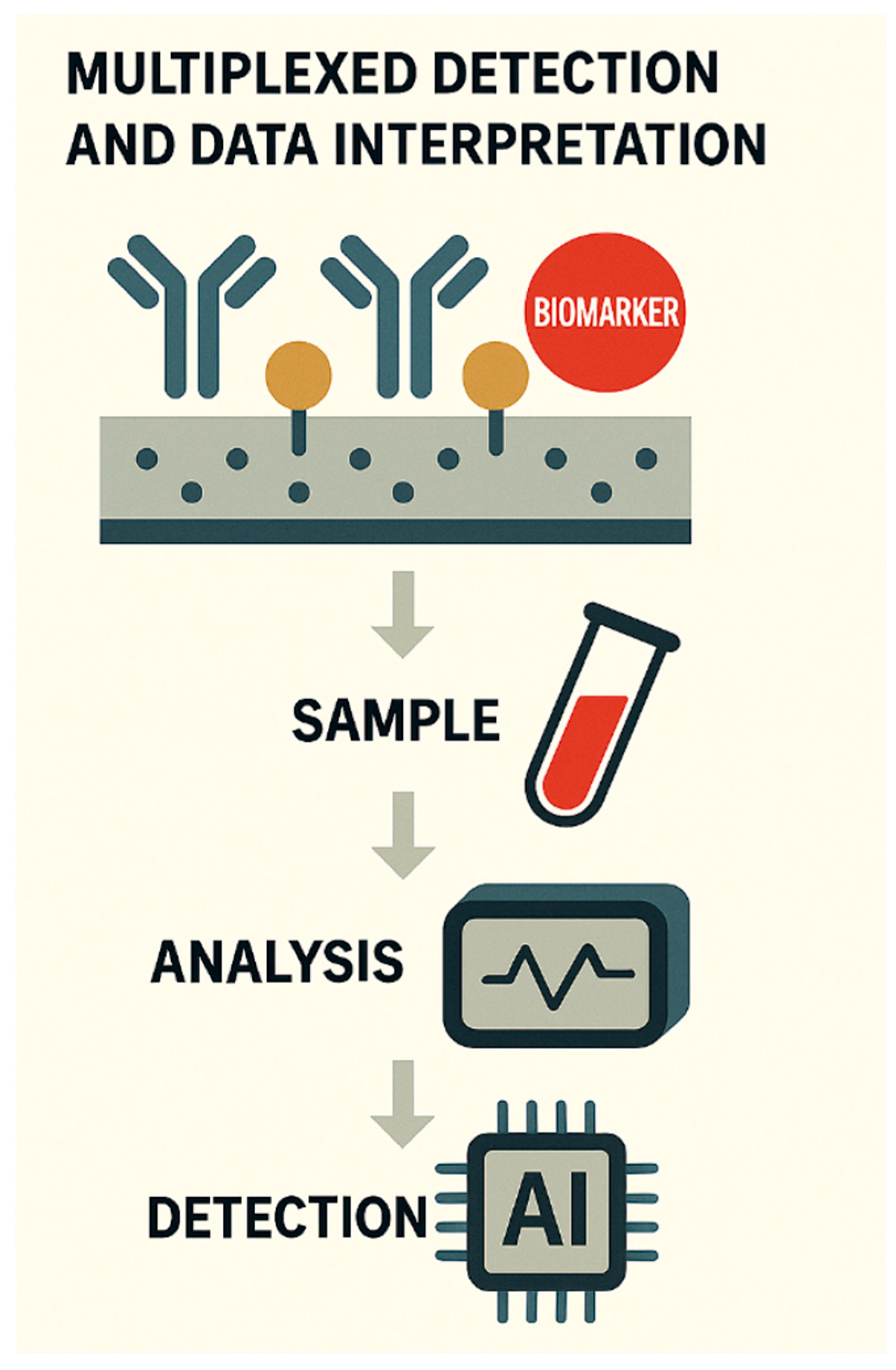

Figure 1.

Schematic of biosensor architecture for cancer diagnostics. This illustration outlines the core components of a biosensor system tailored for cancer biomarker detection. The top segment features the recognition element-typically antibodies or aptamers, designed to selectively bind cancer-specific biomarkers. These interactions occur on the transducer surface, which converts the biochemical signal into a measurable output via electrochemical or optical means. The signal processor then interprets and displays the data, enabling real-time diagnostic feedback. The schematic reflects modular integration with microfluidic channels and wearable formats, underscoring the biosensor’s adaptability for point-of-care applications.

Figure 1.

Schematic of biosensor architecture for cancer diagnostics. This illustration outlines the core components of a biosensor system tailored for cancer biomarker detection. The top segment features the recognition element-typically antibodies or aptamers, designed to selectively bind cancer-specific biomarkers. These interactions occur on the transducer surface, which converts the biochemical signal into a measurable output via electrochemical or optical means. The signal processor then interprets and displays the data, enabling real-time diagnostic feedback. The schematic reflects modular integration with microfluidic channels and wearable formats, underscoring the biosensor’s adaptability for point-of-care applications.

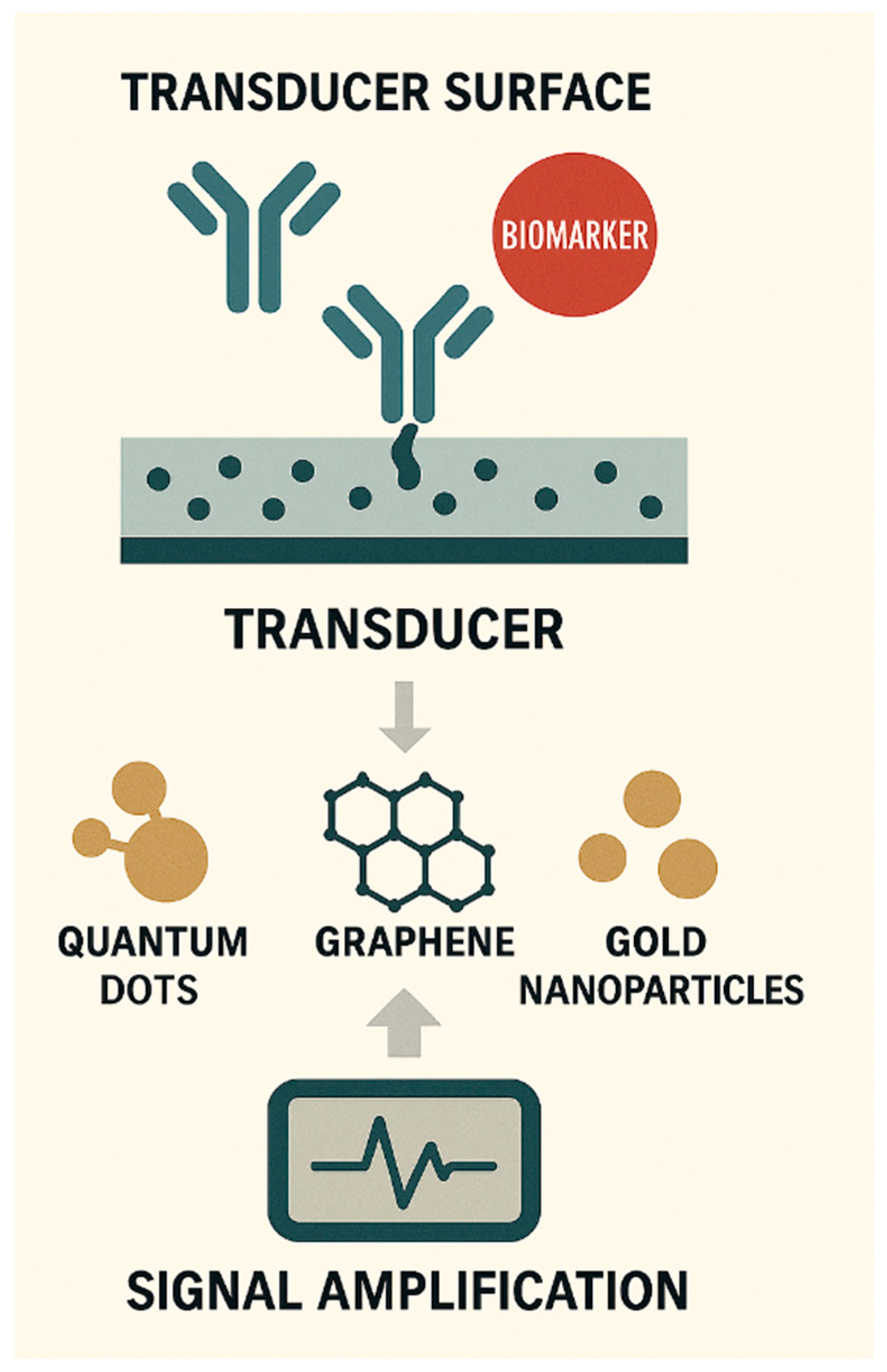

Figure 2.

Schematic of nanomaterial-enhanced biosensing for cancer diagnostics. This illustration highlights the integration of nanomaterials-quantum dots, graphene, and gold nanoparticles, into biosensor transducer surfaces to improve signal amplification and biorecognition efficiency. Antibody molecules immobilised on the transducer bind to cancer-specific biomarkers, while nanomaterials enhance electron transfer, fluorescence, and surface conductivity. The schematic underscores the role of nanoscale engineering in achieving high sensitivity and multiplexed detection, essential for early-stage cancer diagnostics in point-of-care settings.

Figure 2.

Schematic of nanomaterial-enhanced biosensing for cancer diagnostics. This illustration highlights the integration of nanomaterials-quantum dots, graphene, and gold nanoparticles, into biosensor transducer surfaces to improve signal amplification and biorecognition efficiency. Antibody molecules immobilised on the transducer bind to cancer-specific biomarkers, while nanomaterials enhance electron transfer, fluorescence, and surface conductivity. The schematic underscores the role of nanoscale engineering in achieving high sensitivity and multiplexed detection, essential for early-stage cancer diagnostics in point-of-care settings.

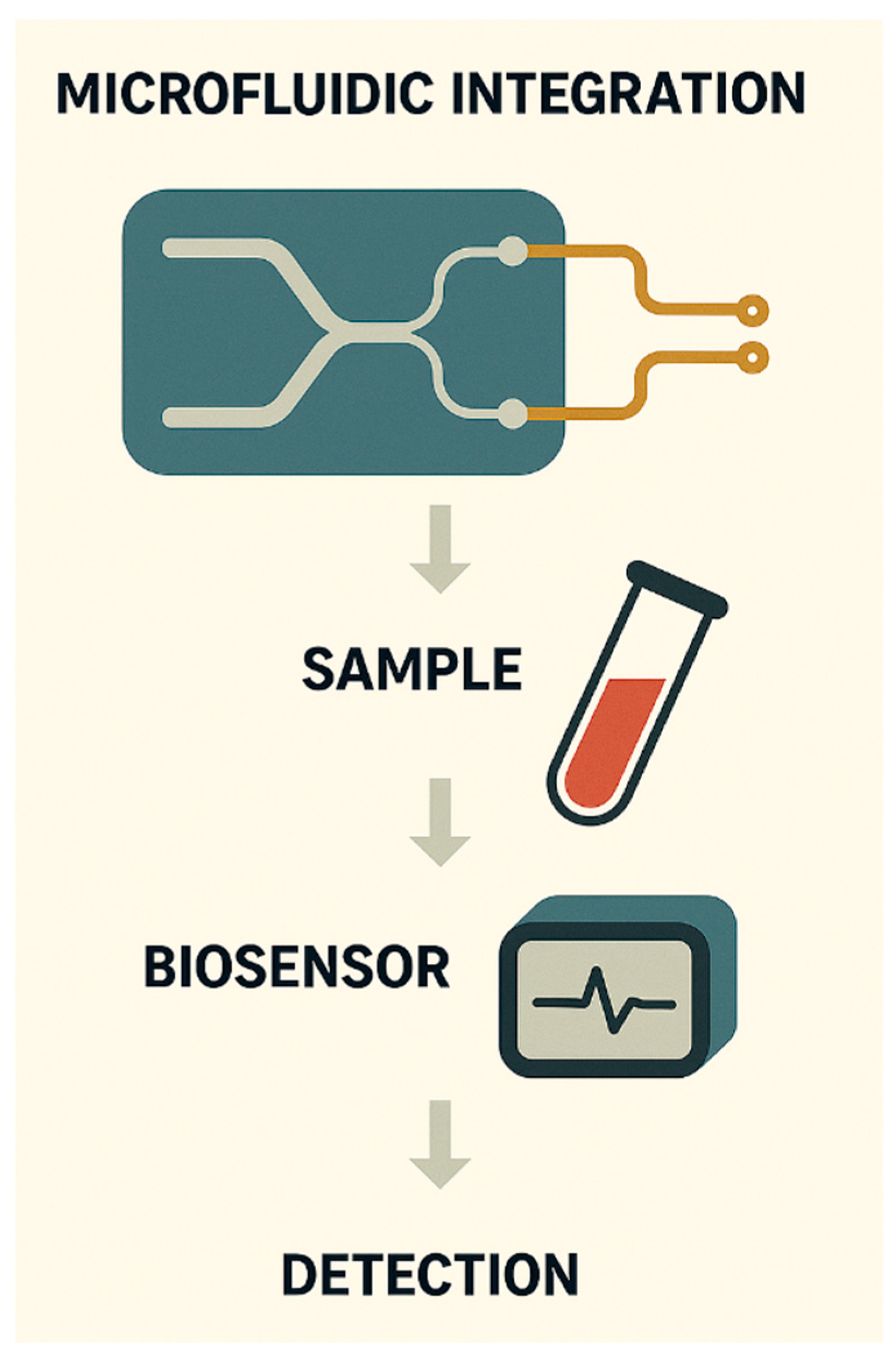

Figure 3.