1. Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB), caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, continues to pose a serious global health challenge, especially in low and middle-income countries such as India, where both pulmonary and extra-pulmonary forms of the disease are widespread [

1]. Prompt and precise diagnosis remains crucial for curbing transmission and initiating treatment effectively [

2]. Traditional diagnostic approaches, like microscopy and culture, have long been used but come with limitations particularly in sensitivity (especially for cases with low bacterial counts) and turnaround time [

3]. While smear microscopy is central to pulmonary TB detection, its efficacy diminishes with paucibacillary or extra-pulmonary samples.

Recently, molecular diagnostics such as the TrueNat MTB/RIF assay a portable chip based nucleic acid amplication and real-time PCR-based test have emerged. This method amplifies TB DNA and simultaneously detects rifampicin resistance, delivering results much faster than standard methods [

4]. With the combined advantages of affordability, simple to operate with good diagnostic sensitivity and portability, these devices are widely used among the peripheral laboratories of India and other countries of South-East Asia which account for 50% of the global burden of MTB [

5]. In July 2020, the Indian Council of Medical Research announced that the WHO recommended the TrueNat platform as the frontline test for the early diagnosis of TB and detection of Rifampicin resistance [

6].

This study investigates how well the TrueNat MTB/RIF test performs compared to smear microscopy in diagnosing both pulmonary and extra-pulmonary TB at a tertiary care hospital in Eastern Uttar Pradesh. The goal is to evaluate sensitivity, specificity, and agreement between these two methods to understand how they might complement each other in improving diagnostic accuracy in this region.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design & Setting

A retrospective study was carried out at a tertiary care hospital in Eastern Uttar Pradesh. It focused on comparing TrueNat MTB/RIF with Ziehl–Neelsen (ZN) microscopy for diagnosing pulmonary and extra-pulmonary TB.

2.2. Sample Collection

During the specified study period, clinical specimens’ sputum for pulmonary TB and fluids/tissue aspirates (pleural, pus, gastric aspirate, FNAC) for extrapulmonary TB were obtained from patients presenting with symptoms or radiographic findings suggestive of TB.

2.3. Laboratory Procedures

Microscopy: ZN-stained smears were examined under light microscopy following RNTCP guidelines for the presence of acid-fast bacilli.

TrueNat MTB/RIF: Samples were processed using the manufacturer’s instructions, involving lysis, DNA extraction, and amplification via a portable PCR device. The assay identifies M. tuberculosis and checks for rifampicin resistance.

2.4. Data Handling

Results from both methods were compiled, and a confusion matrix was constructed. We computed sensitivity, specificity, and Cohen’s kappa coefficient, supplemented by descriptive statistics.

2.5. Ethics

The study received approval from the institutional ethics committee, and patient data were anonymized.

3. Result

A total of 4249 clinical samples were received in the Mycobacteriology section of the Department of Microbiology during the study period. The majority of patients belonged to the 18-40 years age group (37.6%), followed by the 41–60 years group (28.0%). Males accounted for 2353 (55%) outnumbering the females 1896 (44.6%). The detailed characteristics of the patient is represented in

Table 1.

Clinically, the most commonly reported symptom was cough 3038 (71.5%), followed by fever 1730(40.7%). A history of contact with known tuberculosis (TB) cases was reported in 08 patients. HIV testing showed 4214 (99.2%) of patients were non-reactive whereas 35 (0.8%) were reactive. Diabetes mellitus was observed in 20 (1.68) of the patients (

Table 1).

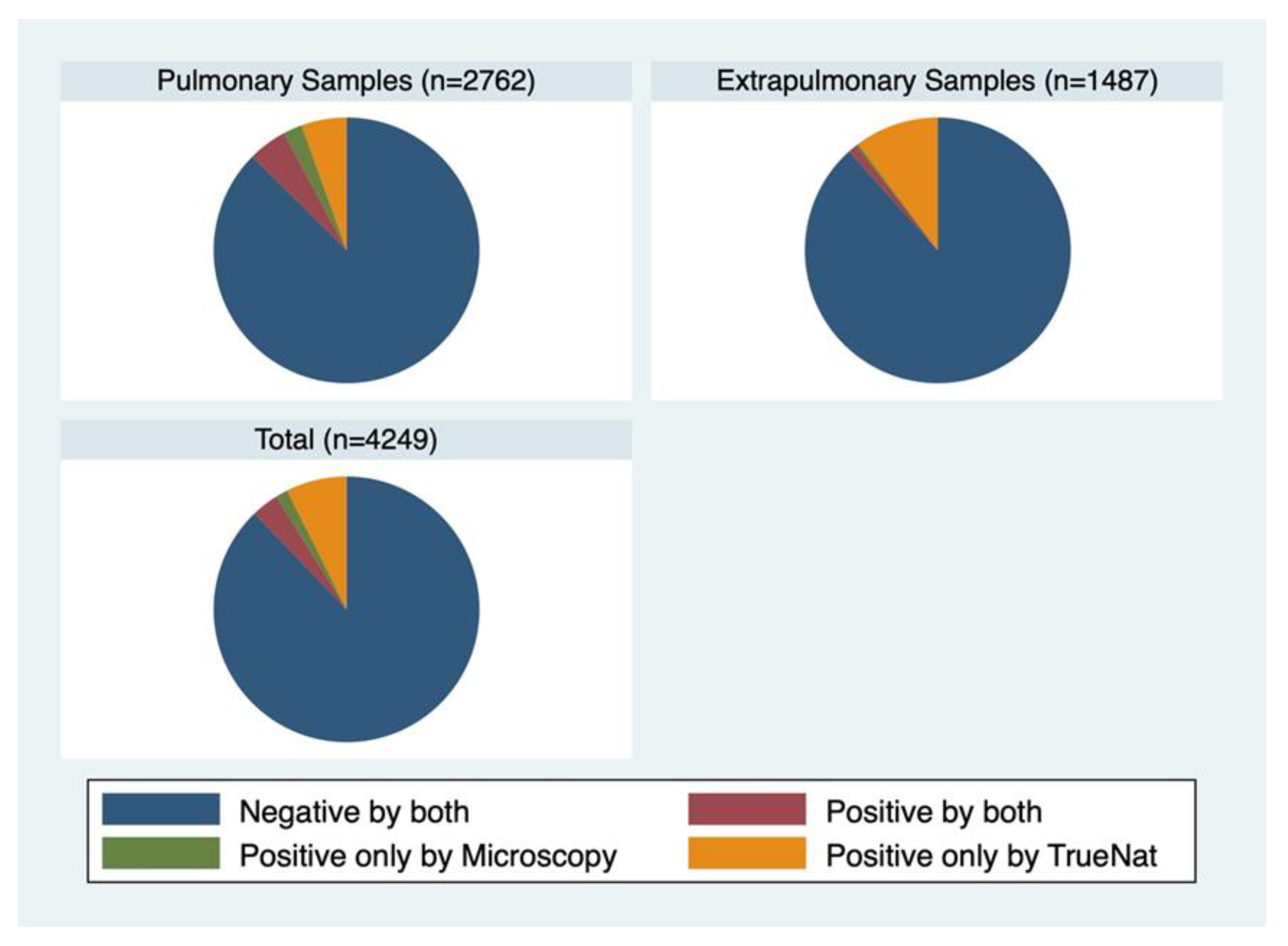

Pulmonary specimens constituted 65.0% (2762) of the total, while extra-pulmonary samples accounted for 35.0% (1487) (

Figure 1). Around 85.8% of the samples were tested negative in both the tests. 22 (0.5%) of the samples tested positive by microscopy only, 400 (9.4%) samples tested positive by TrueNat. 182 (4.3%) samples were tested positive by both (

Figure 1).

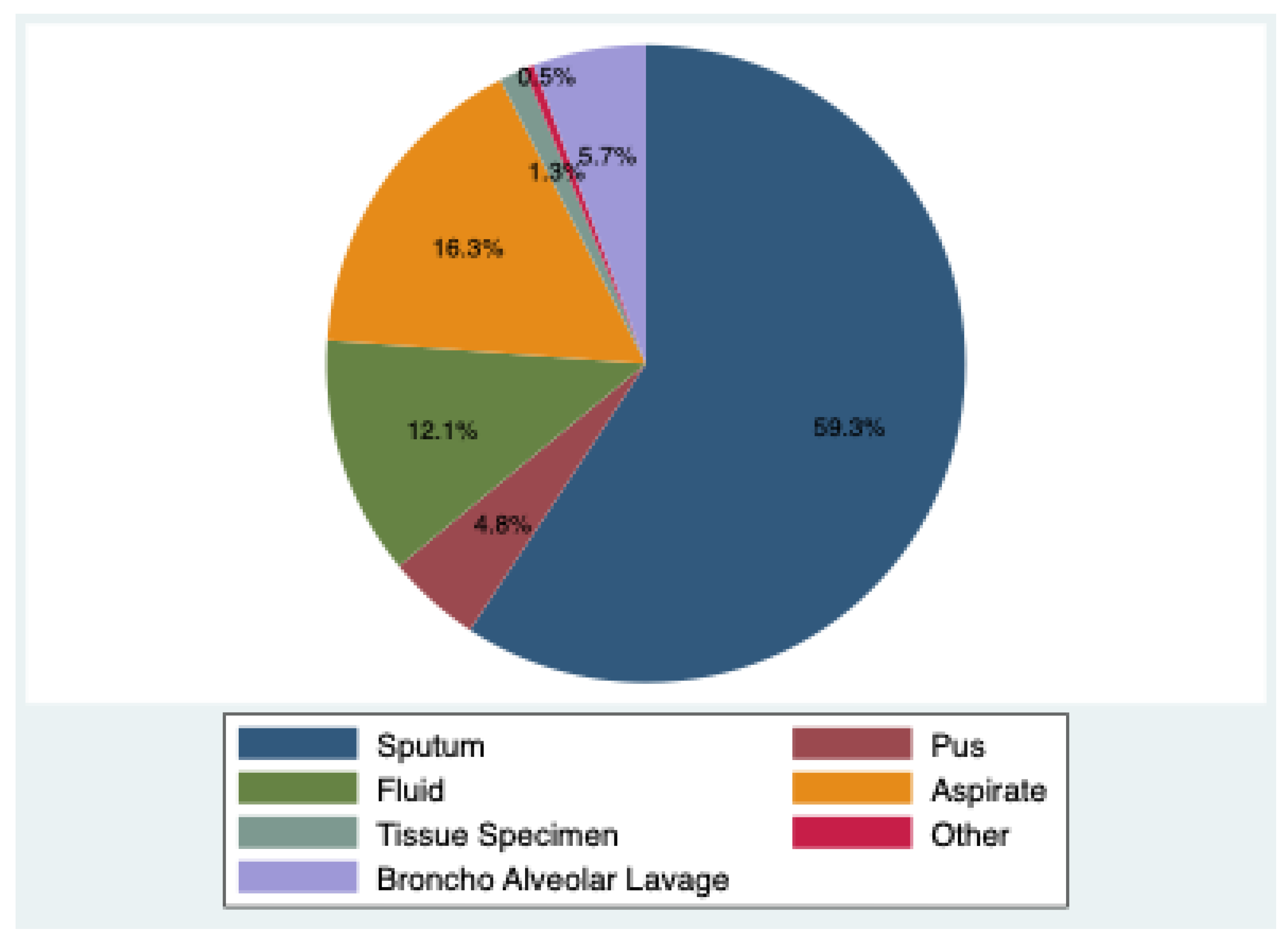

Sputum was the most common 59.3% (2519), followed by bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples 5.7% (243). Extrapulmonary specimens included pus 4.8% (203), fluid 12.1% (515), aspirates 16.3% (692), tissue specimen 1.3% (56) and other parts 0.5% (21).

Figure 2.

Various categories of Clinical Samples.

Figure 2.

Various categories of Clinical Samples.

Among the pulmonary samples, 85.6% were tested negative by both, 0.6% were tested positive by microscopy, 7.5% tested positive by TrueNat and 6.3% tested positive by both. Among extrapulmonary samples 86.2% were tested negative by both, 0.3% tested positive by microscopy, 13.1% tested positive by TrueNat only and 0.5% tested positive by both.

Microscopy (Ziehl-Neelsen staining) revealed acid-fast bacilli (AFB) positivity in 4.3% (185) of samples. Among these, 3+ grading was seen in 28.6% (53), followed by 2+ in 25.4% (47) 1+ in 26.4% (49) and scanty bacilli in 19.4% (36). Mycobacterium tuberculosis was detected by Truenat MTB in 13.7% (583) of the samples with variable bacterial load. Rifampicin resistance was found in 5.6% (33) of cases; 26.4% (154) had indeterminate results, while 67.9% (396) showed no resistance.

The agreement between the microscopy and TrueNat is 42%. The agreement is higher in the pulmonary samples (57%) than the extra-pulmonary samples (6%). Among the samples the highest agreement is observed in sputum (60.5%) followed by tissue specimens (26.3%). Among HIV-reactive (78.4%) and diabetic patients (58.3%), the agreement is found to be higher compared to their counterparts.

Table 2.

Agreement among various sample categories.

Table 2.

Agreement among various sample categories.

| Domain |

Subdomain |

Agreement (p value) |

| Total |

0.4220 (0.000) |

| Sample category |

Pulmonary |

0.5685 (0.000) |

| Sputum |

0.6048 (0.000) |

| Broncho-alveolar Lavage |

0.2107 (0.000) |

| Extrapulmonary |

0.0605 (0.000) |

| Pus |

0.0000 (0.769) |

| Fluid |

0.1123 (0.000) |

| Aspirate |

0.0597 (0.000) |

| Tissue Specimen |

0.2632 (0.000) |

| Others |

0.0000 (no p value) |

| HIV status |

Positive |

0.7843 (0.000) |

| Negative |

0.4197 (0.000) |

| Diabetes |

Positive |

0.5833 (0.021) |

| Negative |

0.4199 (0.000) |

4. Discussion

Tuberculosis (TB) continues to be a major public health problem, particularly in high-burden countries like India. Both pulmonary and extra-pulmonary forms contribute significantly to illness and death [

7]. Our study, carried out in the Mycobacteriology section of a tertiary care hospital in Eastern Uttar Pradesh, provides an updated picture of the demographic distribution, clinical features and diagnostic yields using both smear microscopy and the TrueNat MTB/RIF assay.In our cohort, males accounted for 55.4% of cases, reflecting a male preponderance seen in other TB studies. Rohin Sanjeevani et al. reported a similar pattern with 50.8% males, attributing this to higher outdoor exposure, health-seeking behavior, and cultural barriers for women [

8]. The majority of patients were young to middle-aged adults, with the highest proportion in the 18–40 years group (37.6%), followed by the 41–60 years group (28.0%). This age pattern is consistent with reports by Piyush Ranjan et al. [

9] and Willy Ssengooba et al. [

10] and has major socio-economic implications since this is the most productive age group.

Cough (71.5%) and fever (40.7%) were the most common presenting symptoms, followed by cervical lymphadenopathy (19.6%) and weight loss (12.9%). These findings are in line with the study by Sheetal Sharma et al., who reported cough in 72.2% and fever in 69.4% of TB patients [

11]. Only eight patients reported a history of TB contact, possibly due to poor awareness or reluctance to disclose exposure.

Pulmonary specimens formed the majority (65.0%), with sputum being the most common (59.3%), followed by BAL (5.7%). Extrapulmonary samples constituted 35.0%, including pus, fluids, aspirates, and tissues. This highlights that a substantial burden of TB in our setting arises from extrapulmonary sites, consistent with earlier reports [

12,

13].

Ziehl–Neelsen microscopy detected AFB in only 4.3% of samples, reflecting its low sensitivity, particularly for paucibacillary extrapulmonary samples. Among positive smears, 3+ grading was most frequent (28.6%), followed by 1+ (26.4%), 2+ (25.4%), and scanty (19.4%). In contrast, TrueNat detected TB in 13.7% of samples, more than three times higher than microscopy, corroborating earlier reports of its superior sensitivity [

8,

11]. TrueNat’s ability to detect small amounts of bacterial DNA provides a clear diagnostic advantage.

Among TrueNat-positive samples, rifampicin resistance was found in 5.6%, consistent with national MDR-TB prevalence. However, 26.4% of results were indeterminate, likely due to low bacterial load or genetic variation, while 67.9% were susceptible. This emphasizes the need for confirmatory testing in indeterminate cases.

The overall agreement was 42.2%, indicating significant discordance between the two methods. Agreement was much higher for pulmonary (56.8%) compared to extra-pulmonary samples (6.1%), in line with prior studies showing higher bacillary loads in pulmonary TB [

12,

13]. Within pulmonary specimens, sputum had the highest agreement (60.5%), while BAL showed lower concordance (21.0%). Among extrapulmonary samples, tissue specimens showed moderate agreement (26.3%), while pus and fluid samples showed negligible agreement. This pattern underscores the challenge of extrapulmonary TB diagnosis and supports the superiority of molecular methods in paucibacillary samples [

14].

Interestingly, agreement was higher among HIV-positive (78.4%) and diabetic (58.3%) patients compared to HIV-negative and non-diabetic patients. In HIV infection, advanced immunosuppression may cause disseminated TB with higher bacillary burden, improving concordance between microscopy and molecular assays [

15,

16]. Similarly, diabetes is a known TB risk factor and may lead to higher bacillary loads and delayed clearance, explaining the better agreement [

17].

Our findings reinforce the role of molecular diagnostics in TB control. TrueNat offers rapid detection, higher sensitivity than smear, and simultaneous rifampicin resistance testing, making it highly valuable in high-burden settings. The large proportion of extrapulmonary TB further underscores the need for molecular testing in diverse sample types. However, the retrospective design limited clinical outcome assessment, and the high rate of indeterminate rifampicin resistance warrants further research. Direct comparison with culture and other molecular assays would strengthen diagnostic insights in future studies.

5. Conclusions

TrueNat MTB testing clearly outperforms smear microscopy in detecting TB, especially in extrapulmonary and paucibacillary cases. Our results reflect the ongoing TB burden in Eastern Uttar Pradesh, primarily affecting adults in their working years and with a notable presence of drug resistance. Strengthening molecular diagnostic capacity, alongside screening for comorbidities such as diabetes and HIV, will be crucial to improving TB detection and control in similar high-burden regions.

References

- World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report. 2001;201.

- Abayneh M, HaileMariam S, Asres A. Low Tuberculosis (TB) Case Detection: A Health Facility-Based Study of Possible Obstacles in Kaffa Zone, Southwest District of Ethiopia. Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases and Medical Microbiology. 2020;2020(1):7029458. [CrossRef]

- Boehme CC, Nabeta P, Hillemann D, Nicol MP, Shenai S, Krapp F, Allen J, Tahirli R, Blakemore R, Rustomjee R, Milovic A. Rapid molecular detection of tuberculosis and rifampin resistance. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010 Sep 9;363(11):1005-15. [CrossRef]

- Samatha NV, Choudhari S, Bavaliya S, Ali MM. Diagnostic Role of Truenat in The Rapid Detection of Tuberculosis: A Cross-Sectional Hospital-Based Study. Journal of Contemporary Clinical Practice. 2024 Aug 30; 10:481-6.

- Mathema B, Kurepina NE, Bifani PJ, Kreiswirth BN. Molecular epidemiology of tuberculosis: current insights. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2006 Oct;19(4):658-85. [CrossRef]

- Indian Council of Medical Research World Health Organization endorses truenat tests for initial diagnosis of tuberculosis and detection of rifampicin resistance.

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. biometrics. 1977 Mar 1:159-74.

- Rohin Sanjeevani, Shama Tomar, Harman Multani, (2025) A Microbiological Analysis of Smear Microscopy and Truenat Pcr Method In The Diagnosis Of Pulmonary Tuberculosis In A Tertiary Care Centre. Journal of Neonatal Surgery, 14 (19s), 199-204.

- Ranjan P, Rukadikar AR, Hada V, Mohanty A, Singh P. Diagnostic evaluation of Tru-Nat MTB/Rif test in comparison with microscopy for diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis at tertiary care hospital of eastern Uttar Pradesh. Iran J Microbiol. 2024 Aug;16(4):470-476. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ssengooba W, Katamba A, Sserubiri J, Semugenze D, Nyombi A, Byaruhanga R, Turyahabwe S, Joloba ML. Performance evaluation of Truenat MTB and Truenat MTB-RIF DX assays in comparison to gene XPERT MTB/RIF ultra for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in Uganda. BMC Infect Dis. 2024 Feb 13;24(1):190. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sheetal Sharma et al. Rapid Diagnostic tool in detection of Pulmonary tuberculosis from rural district of RajouriJ&K 2021. Paripex Indian Journal of research: Volume 10, Issue 02: 2021.

- 12. Singh, Meenu; Bhatia, Ragini1; Devaraju, Madhuri2; Ghuman, Malkeet Singh3; Muniyandi, Malaisamy4; Chauhan, Anil5; Kaur, Kulbir1; Rana, Monika1; Pradhan, Pranita1; Saini, Shivani1. Cost-Effectiveness of TrueNat as Compared to GeneXpert as a Diagnostic Tool for Diagnosis of Pediatric Tuberculosis/MDR Tuberculosis under the National Tuberculosis Elimination Program of India. Journal of Pediatric Pulmonology 2(1):p 12-18, Jan–Apr 2023. [CrossRef]

- Sharma K, Sharma M, Sharma V, Sharma M, Samanta J, Sharma A, Kochhar R, Sinha SK. Evaluating diagnostic performance of Truenat MTB Plus for gastrointestinal tuberculosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Aug;37(8):1571-1578. Epub 2022 May 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngangue YR, Mbuli C, Neh A, Nshom E, Koudjou A, Palmer D, Ndi NN, Qin ZZ, Creswell J, Mbassa V, Vuchas C, Sander M. Diagnostic Accuracy of the Truenat MTB Plus Assay and Comparison with the Xpert MTB/RIF Assay to Detect Tuberculosis among Hospital Outpatients in Cameroon. J Clin Microbiol. 2022 Aug 17;60(8):e0015522. Epub 2022 Jul 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gupta A, Swindells S, Kim S, Hughes MD, Naini L, Wu X, et al. Feasibility of identifying household contacts of Rifampin-and multidrug-resistant tuberculosis cases at high risk of progression to tuberculosis disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70:425–35. [CrossRef]

- Lawn, S.D., Kerkhoff, A.D., Burton, R. et al. Diagnostic accuracy, incremental yield and prognostic value of Determine TB-LAM for routine diagnostic testing for tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients requiring acute hospital admission in South Africa: a prospective cohort. BMC Med 15, 67 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Restrepo MI, Sibila O, Anzueto A. Pneumonia in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul). 2018 Jul;81(3):187-197. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).