Introduction and Purpose

Autism spectrum disorders, due to the complexity and heterogeneity that characterize this clinical condition, could benefit from the use of AI resources through the development and implementation of scientifically oriented integrated clinical models [

8].

From a holistic and integrated perspective, it is essential to examine the individual's functioning across various life contexts [

9].

Three AI applications can support the development of language functions in these patients.

The first derives from the development of AI models that use deep learning algorithms such as Large Language Models (LLMs). LLM technologies, like ChatGPT and GPT-4, can read, summarize, generate texts and, most relevant to our interests, engage in conversation, proving useful in various application fields including psychotherapeutic and habilitative/rehabilitative ones [

10].

The second is based on the work of a research team that developed a convolutional neural network capable of processing audio input at slow and fast rhythms different from those learned during training (SITHCon). The network follows the activity model of a group of hippocampal cells called time cells, fundamental for memory formation [

11].

Currently, the application field for this new voice recognition capability is home assistance for the elderly and individuals with speech impairments [

12].

The third relies on facial recognition algorithms such as SARI, currently applied in rehabilitation and in the adaptation of intelligent environments [

13].

Available technological/scientific data represent an important resource for individuals with autism, thanks to their affinity for the perfect contingencies provided by technological devices [

14].

Current knowledge thus allows the development of a project in which the construction of a domotic tool can develop the language of individuals with autism by working on two levels: the production of the ability to make requests and the improvement of phonological aspects [

15].

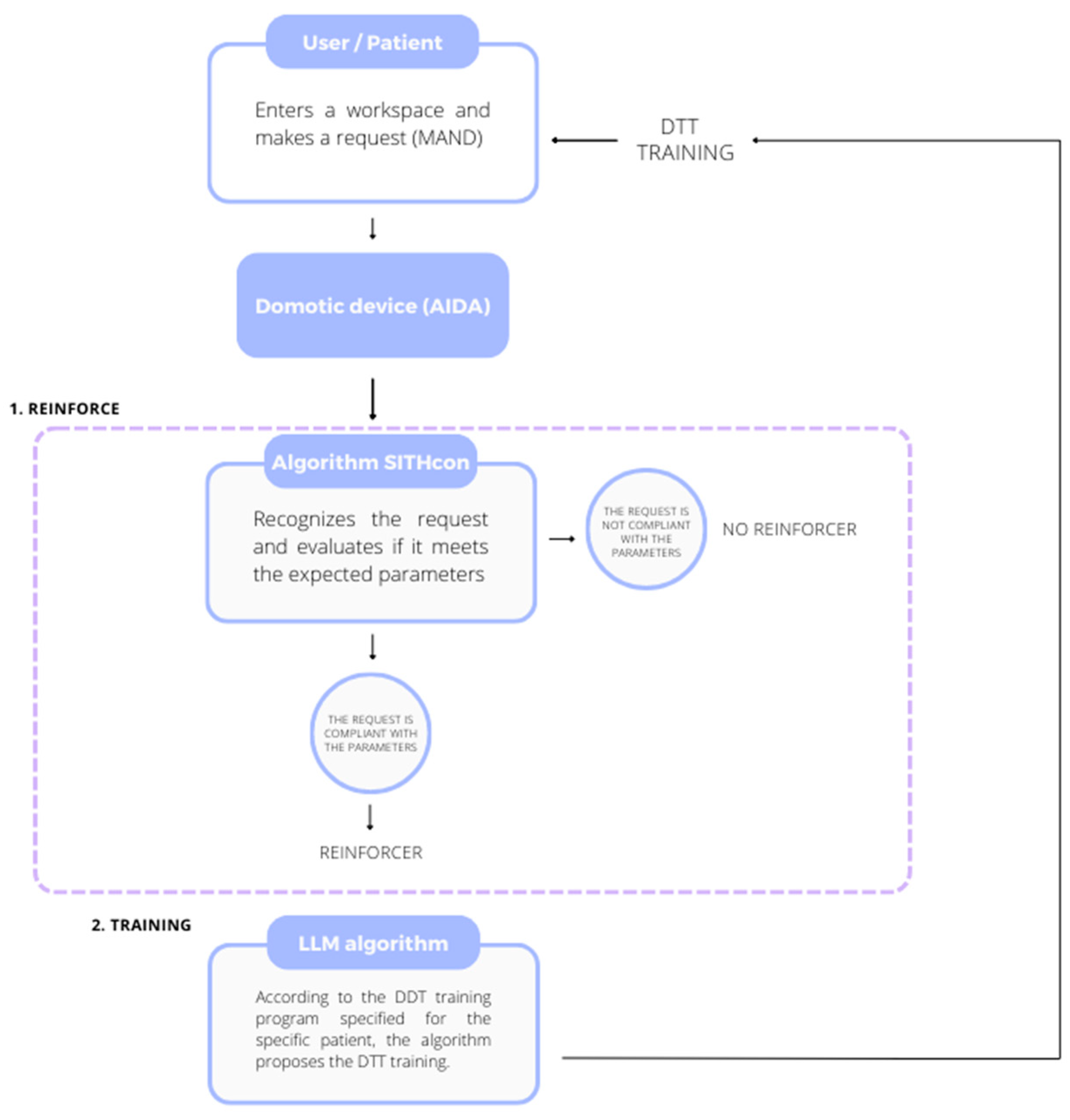

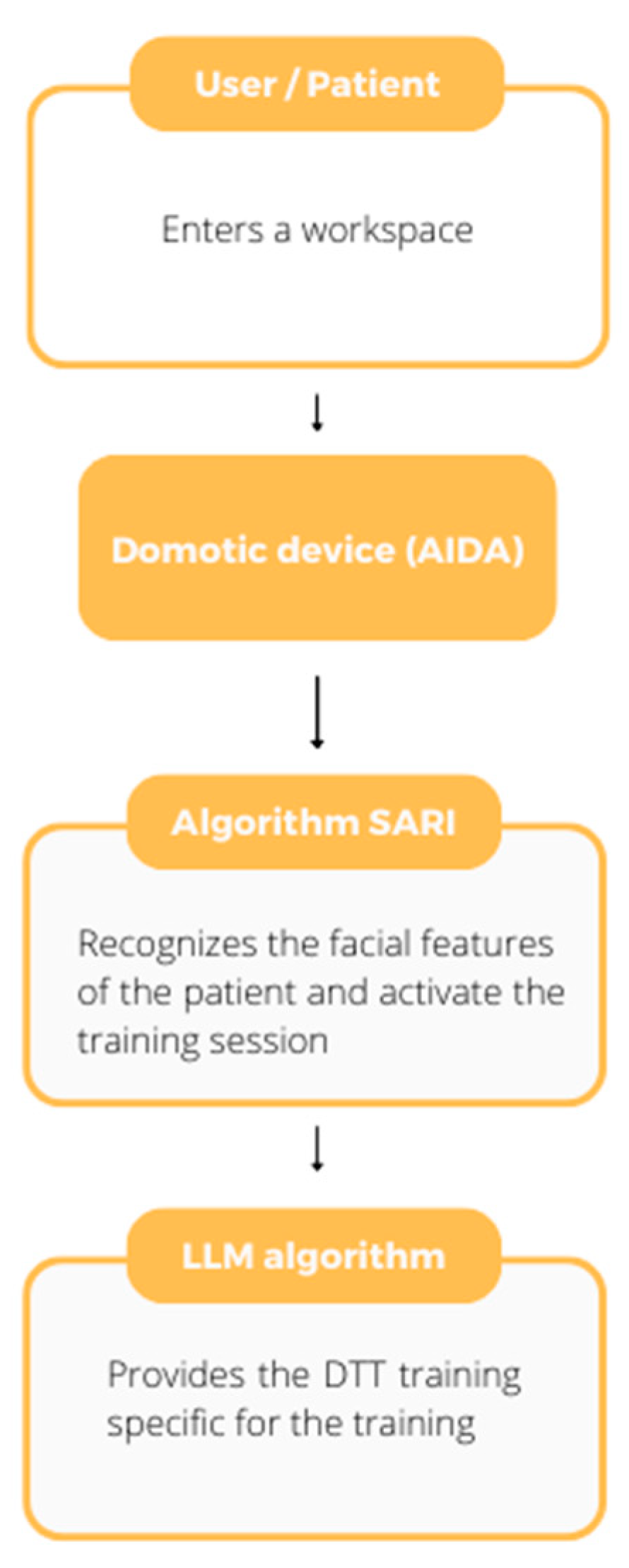

The program we present, AIDA, activates training in DTT without leaving the NET dimension, starting from a request made by the patient or from an interaction initiated by the device based on facial recognition and programmed parameters according to the specific case.

Clinical Procedure: Integration of ABA Principles into AI Devices

The fundamental principles on which applied behavior analysis is based are those of operant conditioning, whereby behavior is shaped by its consequences. This model applies effectively to verbal behavior, which is analyzed according to antecedents and environmental consequences [

16].

Language is classified into verbal operants: mand (request), tact (labeling), echoic (repetition), intraverbal (complex responses) [

17].

To develop language in subjects with ASD, it is necessary to assess prerequisites and reinforcers. Our model targets subjects with ASD up to level 2, with vocal abilities and an intermediate curriculum. It is essential to define the intensity of reinforcers relative to the required effort [

18].

The SITHCon neural network performs assessment of sounds and words pronounced, identifying approximations closest to the adult linguistic model. The shaping procedure, which reinforces increasingly closer responses to the target, is based on this [

19].

The LLM guides the echoic training, asking the user to repeat the target sound/word three times. If correct, a high-magnitude reinforcer follows [

20].

ABA distinguishes two contexts: NET (naturalistic) and DTT (structured). The former develops mand and generalization; the latter aims to refine specific skills such as phonemic accuracy [

21].

The integration of the two contexts in AIDA allows maximum user engagement, respecting spontaneous motivation and programming training based on individual parameters. The device, unlike a technician, does not force collaboration but responds to the internal motivational drive [

22].

Description of AIDA Functioning

When the patient enters the workspace, they can make a request (mand), which is recognized by SITHCon. If valid, the system delivers reinforcement and initiates the DTT training programmed by the LLM algorithm [

23].

Alternatively, training can be automatically initiated by facial recognition (SARI), even in the absence of an explicit request.

Conclusions

The integration between NET and DTT contexts, through an intelligent domotic device, allows intensive yet natural stimulation of language. The internal motivational drive of the user and the controlled environment structure represent a strength for generalization and stable learning [

24].

The limitation of the tool lies in the required prerequisites: it is not suitable for non-vocal subjects or those with severe disabilities. However, the evolution of this project could lead to the concrete realization of the AIDA tool.

References

- Shahamiri, S.R., Thabtah, F., & Abdelhamid, N. (2022). A new classification system for autism based on machine learning. Technology and Health Care, 30(3), 605–622. [CrossRef]

- Supekar, K. et al. (2022). AI-Derived Brain Fingerprints of Autism. Biological Psychiatry, 92(8), 643–653.

- Bowrin, P., & Iqbal, U. (2020). WHOLE trial. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 270, 1399–1400.

- Saleh, M. A., et al. (2021). Robot applications for autism: review. Disability and Rehabilitation. Assistive Technology, 16(6), 580–602.

- Vourganas, I., et al. (2020). Responsible AI for home-based rehabilitation. Sensors, 21(1), 2.

- Dengler, S., et al. (2022). Robots for context recognition. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 293, 232–233.

- Morfini, F. et al. (In publication). Domotics and applied behavior analysis. Springer.

- Morfini, F. (2020). High-functioning autistic disorder. Phenomena Journal.

- Morfini, F. (2023). Autism Open Clinical Model (AOCM). Phenomena Journal.

- Cozzi, P. (2022). AI and voice recognition.

- Suzuki, K. et al. (2017). Deep-Dream Virtual Reality. Scientific Reports. [CrossRef]

- Takuhiro, K. et al. (2019). Cyclegan-VC2: Voice conversion. ICASSP.

- Y. M. M. M. (2018). Face Recognition Accuracy and Eigen-Faces.

- Provenzale, G. (2021). Perceptual dysregulation in autism. Phenomena Journal, 1(3), 29–40.

- Cappiello, M. (2021). Parent training procedures. Phenomena Journal, 1(3), 41–56.

- Skinner, B. F. (2008). Verbal Behavior. Armando Editore.

- Locandro, L. (2020). Autism and family quality of life. Phenomena Journal, 1(2), 35–49.

- Di Leva, A. et al. (2020). GEO-DE: dyspraxia detection. Phenomena Journal, 1(1), 23–34.

- Editorial Board. (2024). Mental Health 4.0. Phenomena Journal, 4(2), 5–7.

- Bonadies, V., & Sasso, E. (2021). Theory of Mind and autism. Phenomena Journal, 1(3), 57–70.

- Trapanese, A. et al. (2023). Predictive processing and autism. Phenomena Journal, 3(1), 15–28.

- Ammendola, A., Cesarano, S.G.D. (2022). Autism and pragmatic language. Phenomena Journal, 2(2), 61–75.

- Durante, S., Avvinto, M.C. (2021). Embodiment and clinical strategies. Phenomena Journal, 1(2), 17–34.

- Sperandeo, R., Giordano, S. (2021). AI and psychotherapy. Phenomena Journal, 1(1), 5–20.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).