1. Introduction

Soils are fundamental to Earth's sustainability, playing a central role in driving biogeochemical nutrient cycles and delivering critical ecosystem services. These include carbon sequestration, water retention and purification, immobilization of toxic metals and organic pollutants, biodiversity conservation, and landscape stabilization [

1,

2]. Soils serve as essential physical habitats that sustain underground biodiversity and condition the physical environment, thereby enhancing landscape beautification. Consequently, healthy soils are integral to the One Health of all global life forms [

1]. Over the past two decades, global soils have been at risk due to extensive soil degradation, along with climate change, biodiversity loss and environmental pollution [

3]. Addressing multifaceted challenges to achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goals by 2030 and beyond necessitates nature-based solutions. Among these, the safeguarding and sustainable management of the Earth's soils are fundamental to securing global agriculture and food supplies [

4].

Converting organic waste from agriculture into biochar and amending it into agricultural soils has received great attention for the last 15 years. Biochar production and soil amendment are widely recognized as a promising strategy for managing organic waste and enhancing soil health on a global scale. This approach draws inspiration from the historical and scientific rediscovery of Terra Preta—a highly fertile, dark earth found in the Amazon Basin of South America. Originally, soils in the Amazon region are highly impoverished as a result of intense weathering under warm and humid climatic conditions [

5]. They are very acid and have low cation exchange capacity to retain nutrients. In addition, soil organic matter content is extremely low due to the rapid decomposition of organic matter under the warm and wet climate. All of these issues challenge the sustainable management of agriculture in most tropical regions.

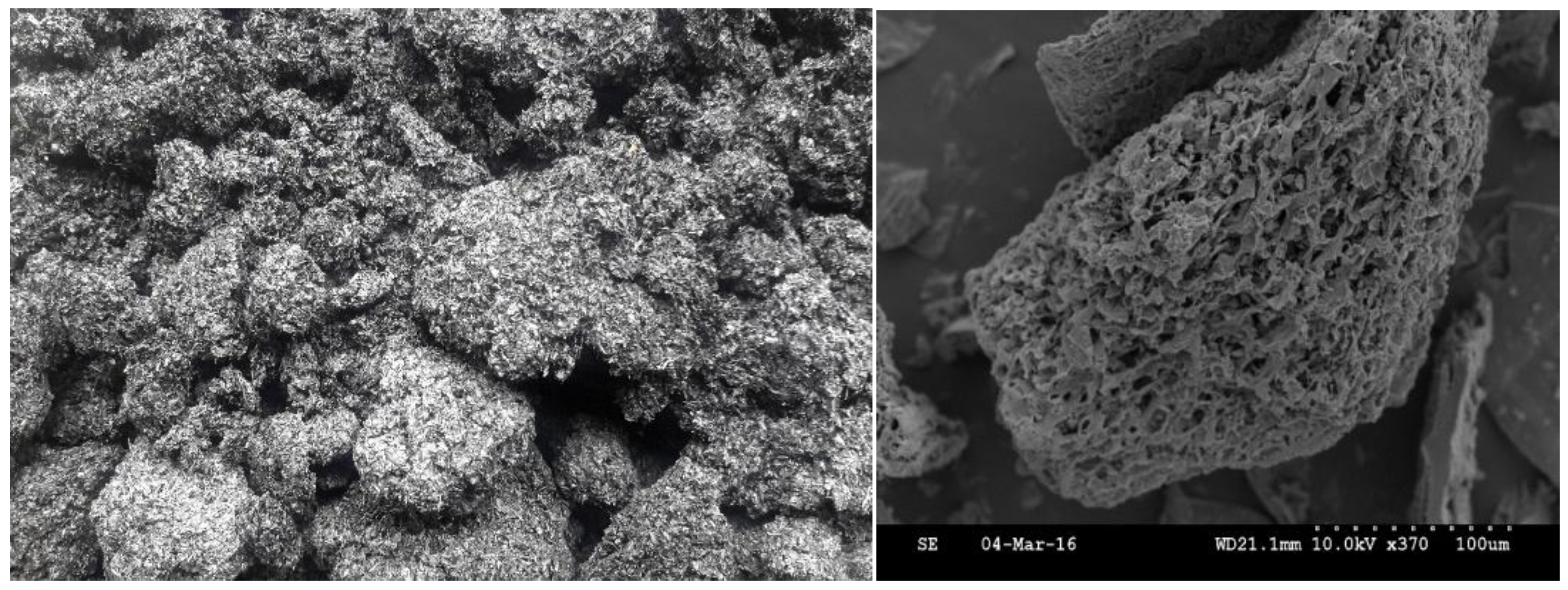

Figure 1.

The spongy biochar mass (Left) from agricultural biomass (cattle manure) pyrolyzed at 550 °C and the porous structure (Right) as shown by scanning electronic microscopy (Photo by Dr Pan, 2016).

Figure 1.

The spongy biochar mass (Left) from agricultural biomass (cattle manure) pyrolyzed at 550 °C and the porous structure (Right) as shown by scanning electronic microscopy (Photo by Dr Pan, 2016).

In the first decade of the twenty-first century, numerous studies were published advocating for the conversion of organic waste into biochar through pyrolysis and its incorporation into soils as a means of sequestering carbon and mitigating climate change. Lehmann [

6] estimated that pyrolyzing forest residues could reduce carbon release by 25% and sequester approximately 10% of the United States' annual fossil-fuel emissions. Compared to burning—which retains only about 3% of carbon—or biological decomposition, converting biomass carbon into biochar enables around 50% of the original carbon to be stored. Furthermore, Lehmann et al. [

7] suggested that replacing slash-and-burn agriculture with slash-and-char techniques could offset up to 12% of global anthropogenic carbon emissions each year through soil sequestration. Beyond its role in carbon storage and climate mitigation, biochar soil amendment was also recognized for its potential to enhance soil productivity and increase crop yields [

8].

In 2009, the book “Biochar for Environmental Management: Science and Technology” was published. It described a very bright future for biochar applications in environmental management based on four complementary and often synergistic objectives. The core content is as follows: biochar production provides a good method of organic waste management; biochar is a good soil amendment; biochar could remain in soil for hundreds to thousands of years, as biochar is composed of quite a lot of poly-aromatic rings, which make it resistant to microbial decomposition; biochar can be used to produce energy.

In the following 10 years, more studies focus on the impact of biochar on plant root growth [

9], plant diseases, including grain diseases and cash crop diseases [

10]and plant heath/food quality [

11,

12,

13]. Nevertheless, a broad range of field experiments has been tested the capacity or possibility of biochar use in soil health improvement to plant health improvement prior to large scale biochar implementation. Based on the individual case studies, this review gives a general conclusion on biochar’s effect on soil fertility, crop yield, crop root growth, plant disease suppression, crop quality (nutrition quality and functional quality). We hope this review will enhance the understanding and awareness of biochar application in the context of One Health.

2. Biochar for Crop Production: Multifaceted Functionality

2.1. Soil Fertility Improvement

Soil amendment of biochar has been well adopted as a promising strategy and practical tool to boost soil fertility in large-scale agricultural production. This pointed mainly to improvement of soil biophysical architecture and thus enhancement of soil porosity and thus water and carbon retention, and to soil adsorption and exchange capacity induced by the porous structure and large surface area in high pH. Therefore, biochar amendment can mitigate soil compaction by improving soil aggregation by 12%–16% [

14]. Soil bulk density decreased by 7.6% to 29%, while soil porosity increased by 7% to 59% across multiple studies [

14,

15,

16,

17]. The positive effect of biochar on soil aggregation was more pronounced in loam-textured, neutral, and acidic soils [

14]. Biochar derived from wood residues pyrolyzed at high temperatures (>600 °C) exhibited a stronger enhancing effect on soil aggregation. These structural improvements contributed to better water retention in the soil. In biochar-amended soils, the available water content was generally higher compared to untreated soils. Specifically, following biochar application, soil water holding capacity increased by 15.1%, 28.5%, 21.0%, and 10.8% in the respective studies [

14,

17,

18].

Biochar significantly influences soil nutrient status, availability, and biogeochemical cycling processes [

19]. Feedstocks such as animal manure and crop residues used for biochar production are inherently rich in nutrients. During pyrolysis, a substantial portion of these nutrients, including phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and silicon, are retained in the resulting biochar. Upon incorporation into soil, these nutrients become available for plant uptake. A meta-analysis by Biederman and Harpole [

20] concluded that biochar amendment significantly enhances the concentrations of phosphorus (P), potassium (K), nitrogen (N), and organic carbon (C) in soil. Furthermore, biochar has been shown to increase soil pH by up to 1.2 units in highly acidic environments [

21]. Numerous studies indicate that biochar alters the dynamics and cycling of soil nutrients, thereby either enhancing or reducing their availability to plants. Nitrogen and phosphorus are among the most frequently affected nutrients. For instance, Gao et al.[

22] and Tesfaye et al. [

23] reported that biochar application increased soil available phosphorus content by 45%-65% on average across individual studies, while plant phosphorus uptake rose by an average of 55%.

For soil, the highest effect was observed in strong acidic and fine-textured soil or in soils with initial low P availability. Biochar amendment in agricultural soils decreases the concentration of inorganic N. The concentration of NO

3− or NH

4+ in biochar amended soil decreased by 10%-12%[

22,

24]. The reduction of soil inorganic N content is probably resulting from N immobilization following a large amount of carbon input with biochar and the higher N use efficiency under biochar amendment. Many studies have shown that biochar addition increases N fertilizer use efficiency although it decreased the N concentration in soils [

25]. Biochar is regarded as slower to capture N and then it is released slowly and taken up by plants. The positive effect for NO

3− and NH

4+ reduction is that biochar could decrease N loss from nitrate leaching and N

2O emission during the processes of nitrification and denitrification [

26]. However, Sha et al. [

27] found that biochar generally had no effect on nitrogen volatilization on average in existing studies. In addition, many other nutrients are applied to soil with biochar. Their availability and cycling will definitely be altered, but this still needs further study. For example, Major et al. [

28] reported a long-lasting yield increase effect of one-time biochar application which they attributed to the increased availability of soil calcium and magnesium. In rice paddies, Liu et al. [

29] found biochar significantly increased the plant-available Si pool and rice shoot Si uptake increased by up to 58%.

2.2. Plant Rooting Promotion

A global meta-analysis by Xiang et al., [

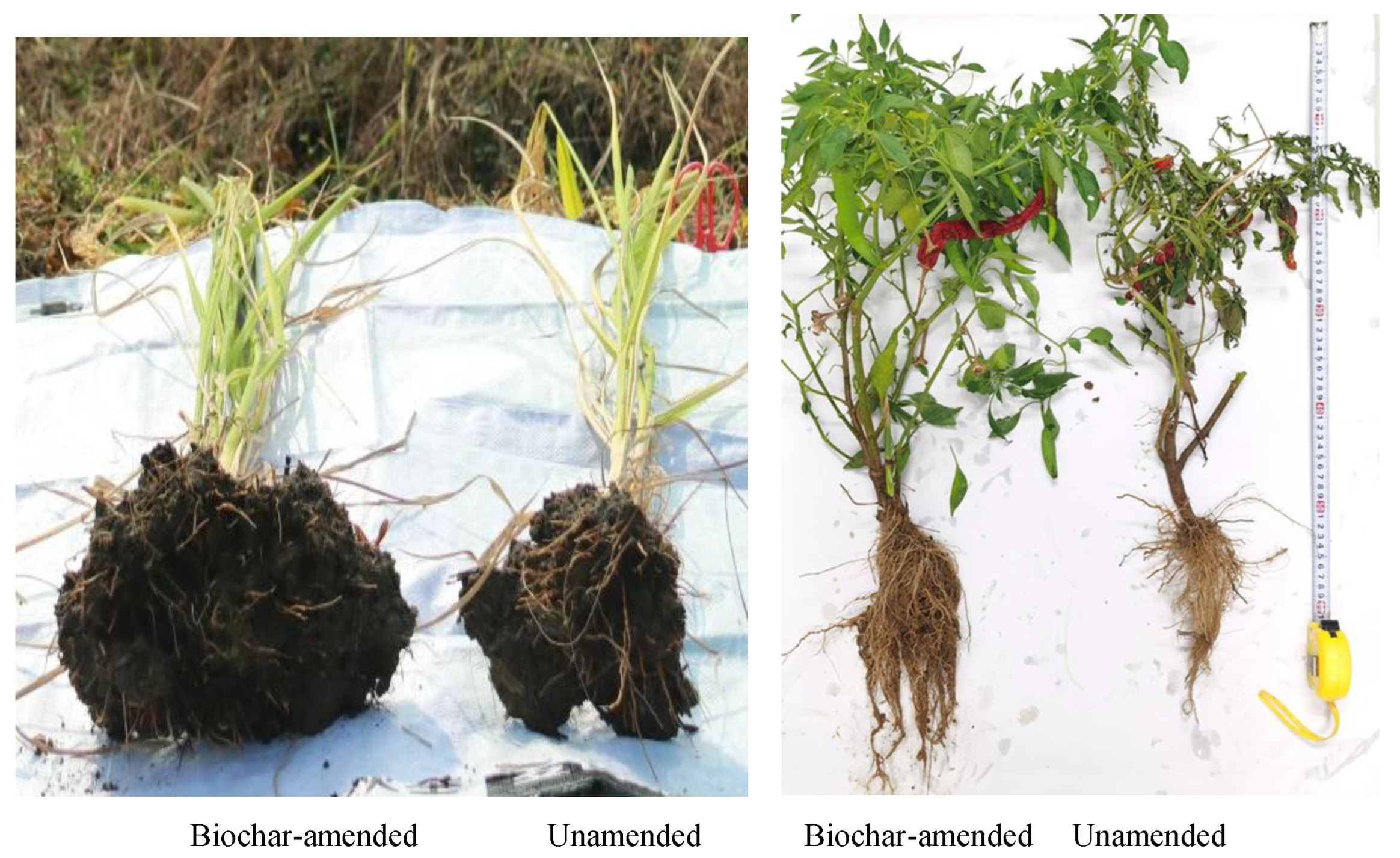

9] revealed a great effect by biochar application on increasing root biomass (+32%), root volume (+29%) and surface area (39%). The biochar-induced increases in root length (+52%) and number of root tips (+17%) were much larger than the increase in root diameter (+9.9%). Indeed, very significant and markedly increase in volume and root lengths have been often observed in field studies using biochar soil amendment for cereals and vegetable crops (

Figure 2). In a pot experiment [

30], the number of fine roots (diameter <0.2 mm) was observed increased with biochar addition. This result suggests that biochar application benefits root morphological development to alleviate plant nutrient and water deficiency rather than to maximize biomass accumulation. We also applied biochar to the maize field and found that biochar increased the biomass of corn roots and improved the root morphology of maize, thereby enhancing the yield [

31]. In the experiment on the effect of biochar on the root growth of perennial crop, we found that ginseng root biomass increased by 25%-27% at 20 t ha

-1 biochar of lingo-cellulose biomass, compared to conventional manure compost [

11]. Moreover, for leguminous crop, biochar can increase the number and weight of root nodules in soybeans and peanuts (

Figure 2), thereby promoting nitrogen fixation in peanuts and enhancing the yield by ca 10% [

12,

13].

These findings may be attributed to differences in root strategies between the two plant life forms. Compared to perennial plants, which typically develop root systems that maximize nutrient conservation, annual plants generally enhance root growth to facilitate greater nutrient acquisition [

9]. Therefore, annual plants are likely to exhibit more efficient root growth compared to perennial plants, owing to the improved soil nutrient conditions resulting from biochar amendment. However, due to the limited number of studies and small sample sizes, it was not possible to draw definitive conclusions regarding the influence of biochar on root traits across different plant life forms. The stronger root biomass response observed in legumes relative to non-legumes may be attributed to enhanced nodulation and more efficient nitrogen fixation in biochar-treated leguminous plants [

12,

32].

2.3. Plant Productivity Boost

Globally, over 200 field and pot experiments have extensively investigated the effects of biochar amendment on plant growth, particularly crop production (

Table 1). These meta-analyses demonstrated that amending agricultural soils with biochar can significantly enhance crop productivity, increasing both shoot biomass and grain yield. The percentage increase ranged from 0% to 32%, with an average of 15% across studies. This considerable variation can be attributed to differences in the target variables used. Early studies often employed the broad term “crop productivity” to encompass as many case studies as possible. This metric referred to grain yield in cereals, biological yield in vegetables, fruit yield in fruit-bearing plants, and shoot or root biomass in most other plants. As the number of case studies grew rapidly, later research shifted its focus specifically to grain yield in field-based investigations.

A number of biotic and abiotic conditions regulate the response of crop productivity to biochar amendment, including crop type, soil acidity and texture, biochar feedstock, climate, and the application rate of N fertilizers. Generally, tuber/root vegetables have the highest yield response to biochar amendment, followed by rapeseed, other vegetables, and the main crops of maize, wheat and rice [

33]. Of the three main crops, maize has the relatively higher grain yield response than the other two; and rice has the lowest response [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. The percent increase for maize, wheat and rice are 14.3%, 8.0% and 3.4% respectively according to the latest study [

37]. Legume crops’ response to biochar amendment varied across studies. Some studies found that significantly higher yield response was observed for legumes than other main crops [

35,

36,

37], while others found biochar had no/little effect on legumes [

33,

34]. Despite, biochar is often recommended for use in dryland crops, especially for soybean, maize and wheat. For the target soils that biochar is going to amend, soil acidity and texture are two key factors that influence the crop yield response to biochar. When adding biochar to acid or coarse textured soils, a greater yield response is expected than when adding it to neutral/alkaline or fine and medium textured soils [

16,

34,

35,

36,

38,

39]. However, in rice paddies, greater rice yield and N use efficiency were observed in alkaline or fine textured soil than in acidic or coarse textured soils [

40].

The properties of biochar are influenced by multiple factors, such as feedstock type, pyrolysis technology, and temperature. Among these, the feedstock source plays a major role in determining crop yield response to biochar amendment. In general, biochar derived from livestock manure tends to exhibit a higher potential for increasing crop yields compared to those from crop straw or wood residues [

33,

34,

35,

40]. However, findings regarding the effectiveness of different plant-based biochars are inconsistent. For instance, Liu et al. [

35] reported that wood residue biochar had a stronger yield-increasing effect than straw-derived biochar, while other studies found the opposite [

34,

35,

36]. In contrast, Bai et al. [

33] and Liu et al. [

40] observed comparable effects between the two. Additionally, biochar produced at pyrolysis temperatures between 350 °C and 450°C appears to have a greater yield-enhancing potential than biochar generated at other temperatures. Jeffery et al. [

39] highlighted the role of climate in moderating crop yield responses to biochar, noting that biochar amendments tend to increase yields in tropical regions but show limited effects in temperate regions. This discrepancy may be attributed to the typically acidic and less fertile soils found in tropical areas, where biochar may help ameliorate soil constraints more effectively.

2.4. Plant Biodefense Manipulation

The direct and indirect changes by biochar of rhizosphere soil, host plant, pathogen and rhizosphere microbiome can have multifactorial impacts on both plant development and disease progress. Due to biochar’s specific chemical properties, abundant nutrients, and porous structure, biochar is capable of recruiting microbes and reshaping the microbial community structure in soils [

41]. An early report on biochar application for plant disease suppression showed that biochar derived from citrus wood induced systemic resistance to Botrytis cinerea and Leveillula taurica on both pepper and tomato [

42]. In the following 10 years, more studies focus on the impact of biochar on plant diseases, including grain diseases and cash crop diseases [

43]. As seen in the picture of

Figure 3 above, the biochar-induced soil health improvement contributed to the increased microbial diversity and activity in the biochar-amended rhizosphere, a potential mechanism of biochar-induced system resistance [

44] with suppression of soil-borne plant diseases [

45]. These effects were shown potentially through reducing colonization of pathogens in soil and enhancing beneficial microorganism growth [

11,

45]. A recent global meta-analysis by Yang et al. [

43] demonstrated that biochar amendment dramatically reduced disease severity by 47.5% on average.

- (1)

The liming effect. Biochar is typically alkaline and has been widely reported to elevate soil pH. As pH plays a critical role in shaping microbial community development, diversity, structure, and pathogen virulence, such alterations can have profound ecological implications. Given that many soil pathogens are adapted to narrow pH ranges [

46], biochar-mediated shifts in rhizosphere pH may significantly influence pathogen survival and activity.

- (2)

The supply of organic compounds varies with the type of biochar feedstock, as different raw materials lead to differences in elemental composition and ash content [

47]. These variations affect the concentrations of active components—such as soluble organic compounds, silicon, and calcium, in the resulting biochars, which likely explains their divergent effectiveness in suppressing plant diseases [

48]. For example, one study confirmed that wood vinegar contains diverse volatile organic compounds that have long been used as pesticides [

49]. However, it should be noted that the introduction of certain toxic compounds through biochar amendment may also increase the incidence and soil persistence of pathogens such as Plasmodiophora brassicae in Brassicaceae cropping systems [

50].

- (3)

Biochar can deactivate toxic compounds released by roots through its strong adsorption capacity, attributed to its high surface area and microporous structure [

51]. For example, activated charcoal has been shown to effectively adsorb various root exudates, such as lactic acid, benzoic acid, vanillic acid, and succinic acid, significantly improving the yield of taro under continuous cropping conditions [

52]. Growing evidence supports the role of biochar in immobilizing allelochemicals derived from root exudates [

45] and suppressing soil-borne pathogens [

44]. In our study on biochar amendment in replanted ginseng (

Panax ginseng), biochar markedly reduced the accumulation of root-derived phenolic allelochemicals, thereby inhibiting soil-borne pathogenic fungi, while simultaneously enhancing microbial diversity and network complexity [

11].

- (4)

Soil microbial manipulation is a critical approach to addressing the challenges posed by continuous cropping, which adversely affects soil health and promotes soil-borne diseases. These conditions further disrupt soil properties, alter microbial community structure, and lead to pathogen accumulation in the rhizosphere [

53,

54]. Biochar amendment has been shown to promote beneficial microorganisms while reducing the abundance and pathogenicity of pathotrophic fungi. Notably, maize biochar outperforms wood biochar in enhancing the abundance of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) and beneficial bacteria [

11]. Additionally, biochar application increases the complexity of microbial co-occurrence networks, particularly within fungal communities [

11,

54]. As a result, the core microbial networks exhibit enhanced resistance even as pathogenic fungi proliferate in biochar-amended soils. Biochar also promotes the enrichment of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) in the rhizosphere via host-mediated recruitment. For instance, Jin et al. [

55] demonstrated that biochar stimulates tomato roots to assemble a protective bacterial community that confers resistance to Fusarium wilt.

- (5)

Biochar induced plant resistance. Biochar soil amendment can directly influence the physiological status of plants, particularly by modifying root exudation, which facilitates the recruitment of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Previous studies have indicated that biochar exerts direct effects on plant growth and physiological processes [

56,

57]. Moreover, biochar shows considerable potential in activating immunity-related gene expression. Transcriptomic analyses in tomato have revealed that biochar primes defense-related pathways, upregulating genes and hormones associated with plant immunity and development—including jasmonic acid, brassinosteroids, cytokinins, auxin, as well as the synthesis of flavonoids, phenylpropanoids, and cell wall components [

58]. In a study by Kong et al. [

59], exogenous application of nanoscale biochar was shown to enhance plant defense responses and confer resistance against the pathogen Phytophthora nicotianae. These findings suggest that biochar, when applied at levels that optimally stimulate plant immunity, could serve as an effective plant protection agent in future agricultural practices.

2.5. Food Quality Enhancement

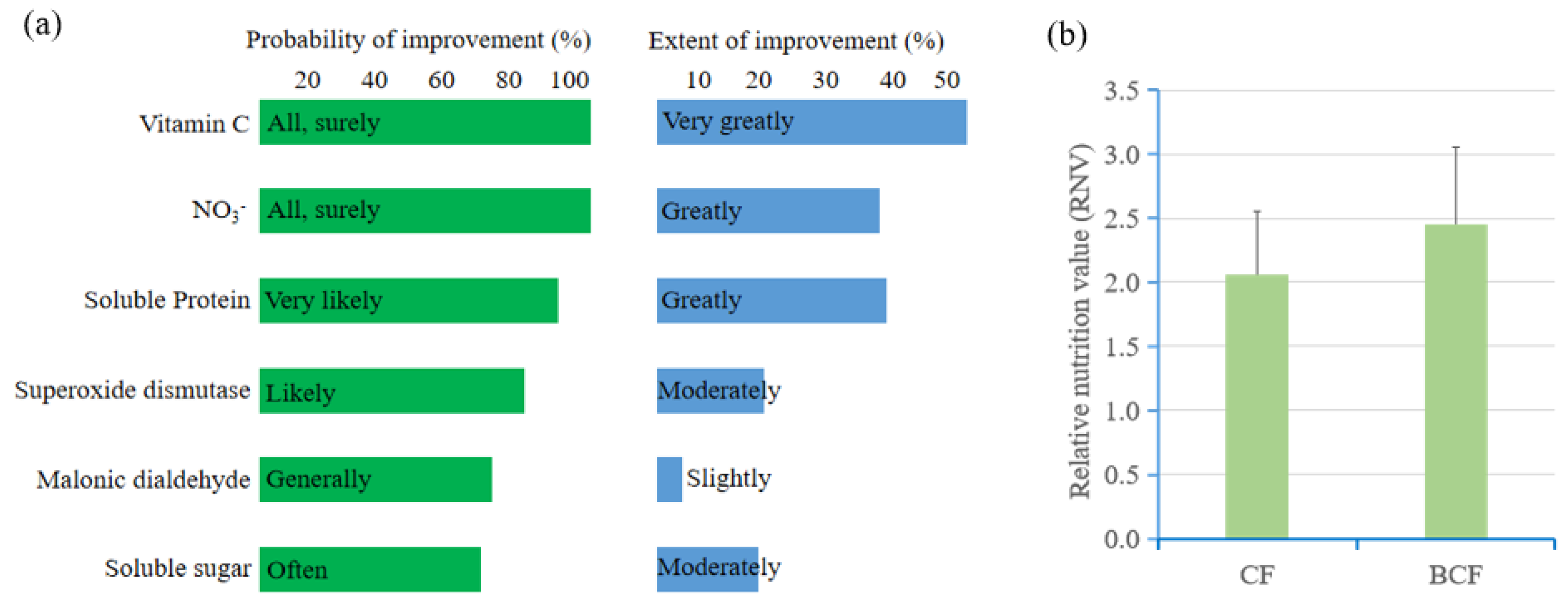

Biochar not only improves soil quality, enhances root growth, and increases crop yield, but in recent years, a growing number of studies has found that biochar can also enhance crop quality. We have found that biochar can increase the vitamin C content reduce nitrate contents, elevate crude protein content, enhance antioxidant capacity, and boost soluble sugar content in fruits and vegetables. Additionally, after normalizing quality-related data from over twenty fruits/vegetables, it was observed that biochar significantly improves the relative nutritional value (RNV) of crops (

Figure 4). These findings indicate that biochar contributes to health from the perspective of both plant development and human nutrition.

Moreover, our study demonstrated that biochar amendment could alter the kernel composition and improve oilseed quality in peanuts [

12,

13]. Despite relatively minor and inconsistent changes in peanut yield across the different amendment treatments, all biochar amendments led to substantial improvements (approximately 10 %) in kernel composition and oilseed quality compared with traditional organic fertilizer. In previous studies, peanut oilseed composition and quality, particularly fatty acid abundance, have been reported to be minimally affected by field conditions, such as climate change simulations [

60] and irrigation performance evaluations [

61]. Biochar amendments induced slight but significant increases in the crude protein content of peanut kernels, which correlated with the ratio of oleic acid to linoleic acid (O/L ratio) and the ratio of oleic acid to palmitic and stearic acid (O/(P + S) ratio). The ratio of oleic acid to linoleic acid, which was crucial for human health [

62,

63], was altered by up to 30% under maize straw biochar compared with control, meeting the Chinese standard for higholeic oilseed [

64]. According to Seleiman et al. [

65], sunflower oil and oleic acid contents decreased by 18% and 26%, respectively, under severe water stress compared to normal conditions. Our findings aligned with those of Khan et al. [

66], who reported a 10% increase in oil and a 12% increase in oleic acid content in rapeseed plants treated with a combination of biochar amendments under severe water stress. In addition, biochar amendments can strongly affect the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites [

67]. For instance, rapeseed treated with wood waste biochar at 10 t ha

-1 exhibited an increase in the ratio of polyunsaturated to saturated fatty acids [

68].

Another study found that biochar increased the health concern of ginseng root quality ginsenosides and reduced residual pesticides [

11]. Compared to control, the total ginsenoside content was unchanged under woodchip biochar but significantly increased by 10% under maize straw biochar, while the cumuli content of Rb1, Re and Rg3, the three key components regulated for ginseng in EU, USA and China, was relatively higher under biochar addition than under control. Furthermore, in the harvested samples of ginseng roots, residual pesticides p,p’-DDE and pentachloro-nitrobenzene were undetected, while the contents of α-666 and δ-666 were unchanged under whipchip biochar but significantly decreased by over 10% under maize straw biochar compared to control. Meanwhile, procymidone content was significantly reduced by 18% and 33% with the application of woodchip biochar and maize straw biochar, respectively.These findings suggested that biochar could significantly improve the quality of crop even under sick soil conditions. Biochar technology may boost high-quality food production in farmlands.

3. Prospectives

Future research directions should also be emphasized. Subsequent studies could focus on the role of biochar as a key component in the transition toward sustainable agriculture, addressing challenges related to climate change, environmental protection, and food security. The function of biochar in fertilizers extends beyond mere adsorption and retention. Exploring the potential benefits of combining biochar with other soil amendments or fertilizers may enhance its capacity to address specific soil deficiencies or problems. This could include investigating formulations that optimize nutrient retention, pH balance, and microbial activity.

It is crucial to conduct thorough studies of the environmental implications related to large-scale biochar production and use. This involves assessing carbon footprint, energy use, and potential emissions to verify that biochar usage aligns with sustainability objectives. For instance, biochar based net zero carbon rice agriculture is under test in Nanjing (

Figure 5, Zero-carbon Field Project, 2025).

Most studies are conducted over short-term periods, and there remains uncertainty about whether biochar’s effectiveness in crop growth persists after prolonged biochar incorporation in the field. Performing extended field research to evaluate the lasting impacts of biochar use on soil characteristics and production would be beneficial. There are some knowledge gap of biochar for health plants:

- (1)

To what extent plant process will be affected by soil changes: abiotic versus biotic?

- (2)

How plant roots respond to biochar material input versus to biochar: habituating versus signaling?

- (3)

What mediate the interplay among plant growth, resistance and biosynthesis following biochar soil application?

- (4)

How will be the legacy of soil-plant system following application of biochar?

Enhancing awareness and understanding of biochar among farmers, land managers, and policymakers is crucial to promoting its broad and sustainable adoption. Outreach efforts should prioritize offering practical guidance on application techniques, appropriate dosages, and context-specific recommendations tailored to different soil types and farming systems. It is also essential to conduct cost–benefit analyses and assess both the internal and external impacts of biochar application in specific regions. Furthermore, performing a meta-analysis of existing biochar research will help integrate and validate findings across studies. Ultimately, without addressing economic feasibility, efforts to encourage farmers to incorporate biochar into their soil management practices are unlikely to succeed.

Author Contributions

C.L. collated documents,drafted papers, and interpreted the results; Shijie Shang.; C.W. and J.M. involved in data, collated documents. Q.Y. collated documents, Writing- review & editing. Shengdao Shan, supervision and resource acquisition; G.P., conceptualization, study designe, Writing- review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by “Pioneer” and “Leading Goose” R&D Program of Zhejiang (2025C02097) and by Basic Operational Funds of Zhejiang University of Science and Technology (2025QN057). This study was also supported by the Innovation Research Project for Youth Scholar of School of Environment and Natural Resources, Zhejiang University of Science and Technology (HZQY202405).

Data Availability Statement

No experiment data were created in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lehmann, J., Bossio, D. A., Kögel- Knabner, I., Rillig, M. C. 2020. The concept and future prospects of soil health. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 544–553. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z., Liu, C., Yan, M., Pan, G. 2023. Understanding and enhancing soil conservation of water and life. Soil Science and Environment 2:9. [CrossRef]

- IPBES. 2019. Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany. 56 pp.

- United Nations Environment Programme. 2022. Nature-based Solutions: Opportunities and Challenges for Scaling Up. Nairobi.

- Glaser, B., Lehmann, J., Zech, W. (2002) Ameliorating physical and chemical properties of highly weathered soils in the tropics with charcoal - a review. Biology and Fertility of Soils 35, 219-230. [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J. (2007) A handful of carbon. Nature 447, 143-144. [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J., Gaunt, J., Rondon, M. (2006) Bio-char Sequestration in Terrestrial Ecosystems – A Review. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 11, 403-427. [CrossRef]

- Sohi, S.P. (2012) Carbon Storage with Benefits. Science 338, 1034-1035. [CrossRef]

- Xiang Y, Deng Q, Duan H, Guo Y (2017) Effects of biochar application on root traits: a meta-analysis. GCB Bioenergy 9:1563–1572. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.H., Chen, T.T., Xiao, R., Chen, X.P., Zhang, T. (2022) A quantitative evaluation of the biochar's influence on plant disease suppress: a global meta-analysis. Biochar 4. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C., Xia, R., Tang, M., Chen, X., Zhong, B., Liu, X.Y., Bian, R.J., Yang, L., Zheng, J.F., Cheng, K., Zhang, X.H., Drosos, M., Li, L.Q., Shan, S.D., Joseph, S., Pan, G.X. (2022a) Improved ginseng production under continuous cropping through soil health reinforcement and rhizosphere microbial manipulation with biochar: a field study of Panax ginseng from Northeast China. Horticulture Research 9. [CrossRef]

- Liu C, Tian J, ..., Pan G. Biochar boosted high oleic peanut production with enhanced root development and biological N fixation by diazotrophs in an alluvic Primisol. Science of the Total Environment, 2024, 932: 173061. [CrossRef]

- Liu C, Shang S, Wang C, ..., Pan G. Biochar amendment increases peanut production through improvement of the extracellular enzyme activities and microbial community composition in replanted field. Plants, 2025, 14, 922. [CrossRef]

- Omondi, M.O., Xia, X., Nahayo, A., Liu, X.Y., Korai, P.K., Pan, G.X. (2016) Quantification of biochar effects on soil hydrological properties using meta-analysis of literature data. Geoderma 274, 28-34. [CrossRef]

- Razzaghi, F., Obour, P.B., Arthur, E. (2020) Does biochar improve soil water retention? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Geoderma 361. [CrossRef]

- Singh, H., Northup, B.K., Rice, C.W., Prasad, P.V.V. (2022) Biochar applications influence soil physical and chemical properties, microbial diversity, and crop productivity: a meta-analysis. Biochar 4. [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.A., Han, J.Y., Gu, Y.N., Li, T., Xu, X.R., Jiang, Y.H., Li, Y.P., Sun, J.F., Pan, G.X., Cheng, K. (2022) Impact of biochar amendment on soil hydrological properties and crop water use efficiency: A global meta-analysis and structural equation model. Global Change Biology Bioenergy 14, 657-668. [CrossRef]

- Edeh, I.G., Masek, O., Buss, W. (2020) A meta-analysis on biochar's effects on soil water properties - New insights and future research challenges. Science of The Total Environment 714. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.H., Hu, Y., Shi, L., Li, G., Pang, Z., Liu, S.Q., Chen, Y.M., Jia, B.B. (2022) Effects of biochar on soil chemical properties: A global meta-analysis of agricultural soil. Plant Soil and Environment 68, 272-289. [CrossRef]

- Biederman, L.A., Harpole, W.S. (2013) Biochar and its effects on plant productivity and nutrient cycling: a meta-analysis. GCB Bioenergy 5, 202-214. [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.Y., Van Zwieten, L., Meszaros, I., Downie, A., Joseph, S. (2007) Agronomic values of greenwaste biochar as a soil amendment. Australian Journal of Soil Research 45, 629-634. [CrossRef]

- Gao, S., DeLuca, T.H., Cleveland, C.C. (2019) Biochar additions alter phosphorus and nitrogen availability in agricultural ecosystems: A meta-analysis. Science of The Total Environment 654, 463-472. [CrossRef]

- Tesfaye, F., Liu, X.Y., Zheng, J.F., Cheng, K., Bian, R.J., Zhang, X.H., Li, L.Q., Drosos, M., Joseph, S., Pan, G.X. (2021) Could biochar amendment be a tool to improve soil availability and plant uptake of phosphorus? A meta-analysis of published experiments. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 28, 34108-34120. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.N., Xu, C.Y., Tahmasbian, I., Che, R.X., Xu, Z.H., Zhou, X.H., Wallace, H.M., Bai, S.H. (2017) Effects of biochar on soil available inorganic nitrogen: A review and meta-analysis. Geoderma 288, 79-96. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q., Zhang, Y.H., Liu, B.J., Amonette, J.E., Lin, Z.B., Liu, G., Ambus, P., Xie, Z.B. (2018) How does biochar influence soil N cycle? A meta-analysis. Plant and Soil 426, 211-225. [CrossRef]

- Borchard, N., Schirrmann, M., Cayuela, M.L., Kammann, C., Wrage-Monnig, N., Estavillo, J.M., Fuertes-Mendizabal, T., Sigua, G., Spokas, K., Ippolito, J.A., Novak, J. (2019) Biochar, soil and land-use interactions that reduce nitrate leaching and N2O emissions: A meta-analysis. Science of The Total Environment 651, 2354-2364. [CrossRef]

- Sha, Z.P., Li, Q.Q., Lv, T.T., Misselbrook, T., Liu, X.J. (2019) Response of ammonia volatilization to biochar addition: A meta-analysis. Science of The Total Environment 655, 1387-1396. [CrossRef]

- Major, J., Rondon, M., Molina, D., Riha, S.J., Lehmann, J. (2010) Maize yield and nutrition during 4 years after biochar application to a Colombian savanna oxisol. Plant and Soil 333, 117-128. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Li, L.Q., Bian, R.J., Chen, D., Qu, J.J., Kibue, G.W., Pan, G.X., Zhang, X.H., Zheng, J.W., Zheng, J.F. (2014) Effect of biochar amendment on soil- silicon availability and rice uptake. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science 177, 91-96. [CrossRef]

- Liu C, Sun B, Zhang X, ..., Pan G. The Water-soluble pool in biochar dominates maize plant growth promotion under biochar amendment. J Plant Growth Regul, 2021a, 40: 1466-1476. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Wang, H.D., Liu, C., Sun, B.B., Zheng, J.F., Bian, R.J., Drosos, M., Zhang, X.H., Li, L.Q., Pan, G.X. (2021b) Biochar increases maize yield by promoting root growth in the rainfed region. Archives of Agronomy and Soil Science 67, 1411-1424. [CrossRef]

- Liu X., Liu C., Gao W., et al. Impact of biochar amendment on the abundance and structure of diazotrophic community in an alkaline soil. The Science of the Total Environment 2019, 688: 944-951. [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.H., Omidvar, N., Gallart, M., Kamper, W., Tahmasbian, I., Farrar, M.B., Singh, K., Zhou, G., Muqadass, B., Xu, C.Y., Koech, R., Li, Y., Nguyen, T.T.N., van Zwieten, L. (2022) Combined effects of biochar and fertilizer applications on yield: A review and meta-analysis. Sci Total Environ 808, 152073. [CrossRef]

- Farhangi-Abriz, S., Torabian, S., Qin, R., Noulas, C., Lu, Y., Gao, S. (2021) Biochar effects on yield of cereal and legume crops using meta-analysis. Science of The Total Environment 775, 145869. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Zhang, A., Ji, C., Joseph, S., Bian, R., Li, L., Pan, G., Paz-Ferreiro, J. (2013) Biochar’s effect on crop productivity and the dependence on experimental conditions—a meta-analysis of literature data. Plant and Soil 373, 583-594. [CrossRef]

- Ye, L., Camps-Arbestain, M., Shen, Q., Lehmann, J., Singh, B., Sabir, M., Condron, L.M. (2019) Biochar effects on crop yields with and without fertilizer: A meta-analysis of field studies using separate controls. Soil Use and Management 36, 2-18. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Wu, Z., Zhou, J., Zhou, L., Lu, Y., Xiang, Y., Zhang, R., Deng, Q., Wu, W. (2022a) Meta-Analysis of the Response of the Productivity of Different Crops to Parameters and Processes in Soil Nitrogen Cycle under Biochar Addition. Agronomy 12, 1857. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y., Zheng, H., Jiang, Z., Xing, B. (2020) Combined effects of biochar properties and soil conditions on plant growth: A meta-analysis. Sci Total Environ 713, 136635. [CrossRef]

- Jeffery, S., Abalos, D., Prodana, M., Bastos, A.C., van Groenigen, J.W., Hungate, B.A., Verheijen, F. (2017) Biochar boosts tropical but not temperate crop yields. Environmental Research Letters 12, 053001. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Li, H., Hu, T., Mahmoud, A., Li, J., Zhu, R., Jiao, X., Jing, P. (2022b) A quantitative review of the effects of biochar application on rice yield and nitrogen use efficiency in paddy fields: A meta-analysis. Sci Total Environ 830, 154792. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.M., Chen, B.L., Zhu, L.Z., Xing, B.S. (2017) Effects and mechanisms of biochar-microbe interactions in soil improvement and pollution remediation: A review. Environ Pollut 227, 98-115. [CrossRef]

- Graber, E.R., Harel, Y.M., Kolton, M., Cytryn, E., Silber, A., David, D.R., Tsechansky, L., Borenshtein, M., Elad, Y. (2010) Biochar impact on development and productivity of pepper and tomato grown in fertigated soilless media. Plant and Soil 337, 481-496. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.H., Chen, T.T., Xiao, R., Chen, X.P., Zhang, T. (2022) A quantitative evaluation of the biochar's influence on plant disease suppress: a global meta-analysis. Biochar 4. [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, A.K., Elad, Y., Paudel, I., Graber, E.R., Cytryn, E., Frenkel, O. (2017) Linking the Belowground Microbial Composition, Diversity and Activity to Soilborne Disease Suppression and Growth Promotion of Tomato Amended with Biochar. Sci Rep 7,44382. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y., Hou, Y.G., Huang, D.P., Hao, Z.X., Wang, X.F., Wei, Z., Jousset, A., Tan, S.Y., Xu, D.B., Shen, Q.R., Xu, Y.C., Friman, V.P. (2017) Application of biochar reduces Ralstonia solanacearum infection via effects on pathogen chemotaxis, swarming motility, and root exudate adsorption. Plant and Soil 415, 269-281. [CrossRef]

- Husson, O. (2013) Redox potential (Eh) and pH as drivers of soil/plant/microorganism systems: a transdisciplinary overview pointing to integrative opportunities for agronomy. Plant and Soil 362, 389-417. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.W., Qin, S.Y., Verma, S., Sar, T., Sarsaiya, S., Ravindran, B., Liu, T., Sindhu, R., Patel, A.K., Binod, P., Varjani, S., Singhnia, R.R., Zhang, Z.Q., Awasthi, M.K. (2021) Production and beneficial impact of biochar for environmental application: A comprehensive review. Bioresource Technology 337. [CrossRef]

- Bian, R., Liu, X., Zheng, J., Cheng, K., Zhang, X., Li, L., et al. (2022) Chemical composition and bioactivity of dissolvable organic matter in biochars. Sci. Agric. Sin. 55, 2174–2186. (In Chinese with English abstract).

- Liu, X., Wang, J.A., Feng, X.H., Yu, J.L. (2021c) Wood vinegar resulting from the pyrolysis of apple tree branches for annual bluegrass control. Industrial Crops and Products 174. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L., Chen, Z., Su, Z. et al. (2023) Soil pH indirectly determines Ralstonia solanacearum colonization through its impacts on microbial networks and specific microbial groups. Plant Soil 482, 73–88. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M., Rajapaksha, A.U., Lim, J.E., Zhang, M., Bolan, N., Mohan, D., Vithanage, M., Lee, S.S., Ok, Y.S. (2014) Biochar as a sorbent for contaminant management in soil and water: A review. Chemosphere 99, 19-33. [CrossRef]

- Asao, T., Hasegawa, K., Sueda, Y., Tomita, K., Taniguchi, K., Hosoki, T., Pramanik, M.H.R., Matsui, Y. (2003) Autotoxicity of root exudates from taro. Scientia Horticulturae 97, 389-396. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Chen, H.L., Gao, J., Guo, J.X., Zhao, X.S., Zhou, Y.F. (2018) Ginsenosides and ginsenosidases in the pathobiology of ginseng-Cylindrocarpon destructans (Zinss) Scholten. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 123, 406-413. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.M., Qin, X.J., Wu, H.M., Li, F., Wu, J.C., Zheng, L., Wang, J.Y., Chen, J., Zhao, Y.L., Lin, S., Lin, W.X. (2020) Biochar mediates microbial communities and their metabolic characteristics under continuous monoculture. Chemosphere 246. [CrossRef]

- Jin, X., Bai, Y., Rahman, M.K., Kang, X., Pan, K., Wu, F., Pommier, T., Zhou, X., Wei, Z. 2022. Biochar stimulates tomato roots to recruit a bacterial assemblage contributing to disease resistance against Fusarium wilt. iMeta e37. [CrossRef]

- Graber, E.R., Tsechansky, L., Mayzlish-Gati, E., Shema, R., Koltai, H. (2015) A humic substances product extracted from biochar reduces Arabidopsis root hair density and length under P-sufficient and P-starvation conditions. Plant and Soil 395, 21-30. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.L., Drosos, M., Mazzei, P., Savy, D., Todisco, D., Vinci, G., Pan, G.X., Piccolo, A. (2017) The molecular properties of biochar carbon released in dilute acidic solution and its effects on maize seed germination. Science of The Total Environment 576, 858-867. [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, A.K., Alkan, N., Elad, Y., Sela, N., Philosoph, A.M., Graber, E.R., Frenkel, O. (2020) Molecular insights into biochar-mediated plant growth promotion and systemic resistance in tomato against Fusarium crown and root rot disease. Sci Rep 10, 13934. [CrossRef]

- Kong, M.M., Liang, J., White, J.C., Elmer, W.H., Wang, Y., Xu, H.L., He, W.X., Shen, Y., Gao, X.W. (2022) Biochar nanoparticle-induced plant immunity and its application with the elicitor methoxyindole in Nicotiana benthamiana. Environmental Science-Nano 9, 3514-3524. [CrossRef]

- Burkey, K.O., Booker, F.L., Pursley, W.A., Heagle, A.S., 2007. Elevated carbon dioxide and ozone effects on peanut: II. Seed yield and quality. Crop Sci. 47 (4), 1488–1497. [CrossRef]

- Ghannadzadeh, A.M., 2015. The Effect of Irrigation Regime and Nitrogen Fertilizer on Seed Yield and Qualitative Characteristics of Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L) (Case Study of Gilan Province, Iran) (Ph D thesis).

- Ibrahim, M.M., Hu, K., Tong, C., Xing, S., Zou, S., Mao, Y., 2020. De-ashed biochar enhances nitrogen retention in manured soil and changes soil microbial dynamics. Geoderma 378, 114589. [CrossRef]

- Barbour, J.A., Howe, P.R.C., Buckley, J.D., Bryan, J., Coates, A.M., 2017. Cerebrovascular and cognitive benefits of high-oleic peanut consumption in healthy overweight middle-aged adults. Nutr. Neurosci. 20 (10), 555–562. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, 2018. Industry Standard of High Oleic Acid Peanut.

- Seleiman, M.F., Refay, Y., Al-Suhaibani, N., AI-Ashkar, I., EI-Hendawy, S., Hafez, E.M., 2019. Integrative effects of rice-straw biochar and silicon on oil and seed quality, yield and physiological traits of Helianthus annuus L. grown under water deficit stress. Agronomy 2019 (10), 637. [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z., Khan, M.N., Zhang, K., Luo, T., Zhu, K., Hu, L., 2021. The application of biochar alleviated the adverse effects of drought on the growth, physiology, yield and quality of rapeseed through regulation of soil status and nutrients availability. Ind. Crop. Prod. 171, 113878. [CrossRef]

- Vigar, M., Hancock, R.D., Miglietta, F., Taylor, G., 2015. More plant growth but less plant defence? First global gene expression data for plants grown in soil amended with biochar. Glob. Chang. Biol. Bioenergy 7, 658–672. [CrossRef]

- Moradi, S., Sajedi, N.A., Madani, H., Gomarian, M., Chavoshi, S., 2023. Integrated effects of nitrogen fertilizer, biochar, and salicylic acid on yield and fatty acid profile of six rapeseed cultivars. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 23 (1), 380–397. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).