Submitted:

01 September 2025

Posted:

02 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Summary

2. Data Description

2.1. Prompt Description of the Study Case

2.1.1 Context

- Purpose: Provide the professional and technical framework within which all subsequent instructions must be interpreted.

2.1.2 Instructions

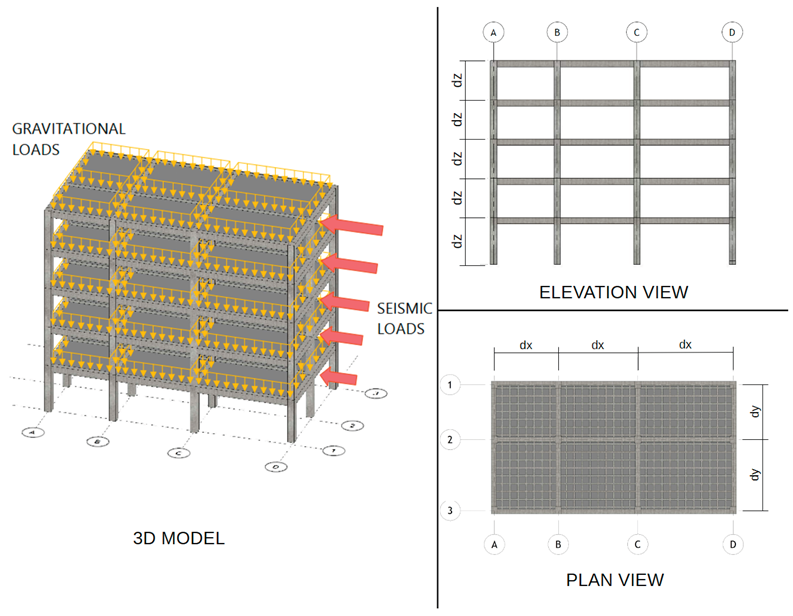

- Analyse a three-dimensional reinforced concrete frame.

- Verify code compliance for inter-story drift.

- Apply structural optimisation if necessary.

- Purpose: Define the general workflow of the analysis.

2.1.3 Details

- Material properties: modulus of elasticity.

- Geometry: spans in X and Y directions; storey heights.

- Cross-sections: beams and columns dimensions.

- Cracking factors: beams (0.7), columns (0.8).

- Loads: dead load (4.9 kN/m²), live load (1.9 kN/m²).

- Coefficients: load factors, base shear coefficient, torsion factor, drift amplification, maximum allowable drift.

- Purpose: These values serve as tabular input data to be read directly by the solver. Each line corresponds to a parameter category, and their interpretation is straightforward (e.g., geometric dimensions in meters, load intensities in kN/m²).

2.1.4 Tasks

- Iterate through all inelastic drift values.

- Compare against maximum allowable drift (0.02).

- If one or more values exceed the limit, report the story number, direction, and drift value.

- Only if all drifts are ≤ 0.02, compliance may be confirmed.

- Present results in tabular format with numerical precision.

- If non-compliance occurs, generate 10 alternatives by modifying materials and section dimensions.

- Re-evaluate drifts for each configuration.

- Compare alternatives in tabular form.

- Highlight compliant and efficient options.

2.1.5 Intent

- Generate an automated technical report.

- Include detailed structural analysis, code validation, and optimisation proposals when required.

- Use technical language with clear tables.

- Ensure suitability for professional and academic environments.

2.2. Dataset Significance

- -

- Storey Drift: Storey drift values are reported for each storey in both the X and Y directions (Table 3). These tables allow readers to observe the vertical distribution of drift across cases and computational methods. Storey drift quantifies the relative displacement between consecutive levels and is a key parameter for NEC-15 compliance, which establishes a 2% upper limit. Reading guide: Table 3 display raw drift values per storey and direction, enabling direct verification of inter-storey deformation patterns.

- -

- Maximum Displacement: The maximum story displacements in the X and Y directions summarised numerically in Table 4. This dataset provides insight into global deformation profiles, which are essential for evaluating the likelihood of structural interaction with neighboring buildings. Reading guide: Table 4 reports the corresponding numerical values of the displacement in meters for each computational method.

- -

- Base Shear: Table 5 presents the base shear (kN) values for the studied cases. These results quantify the seismic demand transmitted to the foundation and reflect the combined influence of structural weight and stiffness. Reading guide: Table 5 provides total base shear per case and method, facilitating cross-model comparison.

- -

- Building Period. The fundamental period of vibration for each case is shown in Table 6. As an indirect measure of stiffness, the building period is critical for understanding overall structural dynamics, where shorter periods generally correspond to reduced displacements. Reading guide: Figure 4 presents the variation of the fundamental period across study cases, while Table 11 provides the tabulated values per method.

2.3. Relative Error as a Measure of Accuracy

- ○

- Benchmarking performance: It provides a direct comparison of novel AI-assisted methods (GPT and GPT+MCP) against a widely validated standard (ETABS).

- ○

- Cross-parameter evaluation: Since relative error is unitless, it permits consistent assessment across storey drift (%), displacements (m), base shear (kN), and period (s).

- ○

- Reproducibility and extension: Researchers can employ the provided error tables to reproduce the evaluation, extend the analysis to new structural typologies, or integrate the metric into broader model validation frameworks.

3. Methods

3.1. Architecture Workflow

3.2. Data Collection and Processing

3.3. Validation and Curation

3.5. Data Quality and Noise Control

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| GPT | Generative Pre-trained Transformer |

| MCP | Model Context Protocol |

| BIM | Building Information Modeling |

| HVAC | Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning |

| NEC-15 | Norma Ecuatoriana de la Construcción 2015 |

| ASCE 7-22 | American Society of Civil Engineers Standard 7-2022 |

| ETABS | Extended Three-dimensional Analysis of Building Systems |

| OpenSees | Open System for Earthquake Engineering Simulation |

| OpenSeesPy | Python interface to OpenSees |

| JSON | JavaScript Object Notation |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| FastAPI | Fast Application Programming Interface (Python framework) |

| CIDI | Context–Instruction–Details–Intent |

References

- Avila C, Ilbay D, Rivera D. Human-AI Teaming in Structural Analysis: A Model Context Protocol Approach for Explainable and Accurate Generative AI 2025. [CrossRef]

- Garza Morales GA, Nizamis K, Bonnema GM. Engineering complexity beyond the surface: discerning the viewpoints, the drivers, and the challenges. Res Eng Des 2023;34:367–400. [CrossRef]

- Morales GAG, Nizamis K, Bonnema GM. Why is there complexity in engineering? A scoping review on complexity origins. 2023 IEEE International Systems Conference (SysCon), IEEE; 2023, p. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Suh, NP. Complexity in Engineering. CIRP Annals 2005;54:46–63. [CrossRef]

- Oladele Junior Adeyeye, Ibrahim Akanbi. ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE FOR SYSTEMS ENGINEERING COMPLEXITY: A REVIEW ON THE USE OF AI AND MACHINE LEARNING ALGORITHMS. Computer Science & IT Research Journal 2024;5:787–808. [CrossRef]

- Liang H, Kalaleh MT, Mei Q. Integrating Large Language Models for Automated Structural Analysis 2025. [CrossRef]

- Cha Y-J, Ali R, Lewis J, Büyükӧztürk O. Deep learning-based structural health monitoring. Autom Constr 2024;161:105328. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Le B, Akhtar N, Lam S-K, Ngo T. Large Language Models for Computer-Aided Design: A Survey. ACM Comput Surv 2025;37:31. [CrossRef]

- Salehi H, Burgueño R. Emerging artificial intelligence methods in structural engineering. Eng Struct 2018;171:170–89. [CrossRef]

- Cáceres M, Avila C, Rivera E. Thermodynamics-Informed Neural Networks for the Design of Solar Collectors: An Application on Water Heating in the Highland Areas of the Andes. Energies (Basel) 2024;17. [CrossRef]

- Lu J, Tian X, Zhang C, Zhao Y, Zhang J, Zhang W, et al. Evaluation of large language models (LLMs) on the mastery of knowledge and skills in the heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) industry. Energy and Built Environment 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yang X, Chen B, Tam Y-C. Arithmetic Reasoning with LLM: Prolog Generation & Permutation. 2024 Annual Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Mexico: 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ismayilzada M, Paul D, Montariol S, Geva M, Bosselut A. CRoW: Benchmarking Commonsense Reasoning in Real-World Tasks. The 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ghimire P, Kim K, Acharya M. Opportunities and Challenges of Generative AI in Construction Industry: Focusing on Adoption of Text-Based Models. Buildings 2024;14. [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, N. Advancing Multi-Agent Systems Through Model Context Protocol: Architecture, Implementation, and Applications 2025. [CrossRef]

- Hou X, Zhao Y. Model Context Protocol (MCP): Landscape, Security Threats, and Future Research Directions 2025;1. [CrossRef]

- Ray PP, Pratim PR. A Survey on Model Context Protocol: Architecture, State-of-the-art, Challenges and Future Directions 2025. [CrossRef]

- Anthropic. Introducing the Model Context Protocol 2024. https://www.anthropic.com/news/model-context-protocol (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Mavroudis V. LangChain. HAL Open Science 2024. [CrossRef]

- CAMICON, MIDUVI. Norma ecuatoriana de la construcción - NEC: NEC-SE-MP - Mamposteria estructural. Quito: 2014.

- American Society of Civil Engineers. Minimum Design Loads and Associated Criteria for Buildings and Other Structures, ASCE/SEI 7-22. Reston: 2022. [CrossRef]

- Jiang G, Chen J. Efficient fine-tuning of large language models for automated building energy modeling in complex cases. Autom Constr 2025;175:106223. [CrossRef]

- Jurišević N, Kowalik R, Gordić D, Novaković A, Vukašinović V, Rakić N, et al. Large Language Models as Tools for Public Building Energy Management: An Assessment of Possibilities and Barriers. International Journal for Quality Research 2025;19. [CrossRef]

(a) |

| prompt = ( "Context:" "You are an expert in structural analysis using natural language and numerical simulation with OpenSeesPy. " "The implemented system is capable of interpreting technical prompts and generating automated structural simulations " "based on international seismic-resistant design standards." "Instructions:" "Analyse a three-dimensional reinforced concrete frame, verify code compliance for inter-story drift, " "and apply structural optimization if necessary." "Details:" "The modulus of elasticity for concrete is 21,458,890.83 kN/m². " "The structural system has spans of 4.0 and 4.0 meters in the X direction, and spans of 4.0 and 4.0 meters in the Y direction. " "The structure has 2 stories, with story heights of: 3.0 and 3.0 meters respectively. " "Beams have a cross-sectional dimension of 0.25 x 0.30 meters, and columns are 0.30 x 0.30 meters. " "Cracking factors are 0.7 for beams and 0.8 for columns. " "Dead load is 4.9 Kn/m² and live load is 1.9 kN/m². " "The weight coefficients are: 1.0 for dead load, 0.15 for live load, 0.1488 for base shear coefficient, " "1.0 for vertical distribution of base shear, 0.05 for accidental torsion, " "and a drift amplification factor of 6.0 is applied to estimate inelastic drift. The maximum allowable drift is 0.02." "Tasks:" "1. Perform linear static seismic analysis using the equivalent lateral force method with OpenSeesPy. " "2. Compute maximum displacements and story drifts per level and direction (X and Y). " "3. Perform strict numerical validation:" " - Iterate through all obtained inelastic drift values. " " - For each value, compare it against the allowable maximum (0.02). " " - If *at least one value* exceeds 0.02, *you must not state that all values are compliant*. " " - Report precisely: story number, direction (X or Y), and the drift value that exceeds the limit. " " - Only if *all drifts* are ≤ 0.02, the code compliance can be confirmed. " " - Present results in tabular format and be rigorous with numerical precision." "4. Also determine floor-by-floor shear forces and vibration modes." "5. Structural optimization:" " - If any drift exceeds the limit, propose a structural optimisation based on displacements, " " storey drifts, shear forces, and vibration modes. " " - Generate 10 alternatives by modifying material properties and section dimensions. " " - Evaluate drift for each alternative and present the comparison in tabular format. " " - Highlight the configurations that meet code requirements and provide better structural efficiency." "Intent:" "Generate an automated technical report, including detailed structural analysis, code validation, " "and optimisation in case of non-compliance. The output must be expressed in technical language and clear tables, " "suitable for professional and academic environments." ) |

| (b) |

| Category | Parameter | Magnitude |

|---|---|---|

| Geometry | Number of Stories | 2 |

| Story Heights | 3.0, 3.0 m (from bottom to top) | |

| Spans in X Direction | 4.0 m, 4.0 m | |

| Spans in Y Direction | 4.0 m, 4.0 m | |

| Sections | Beam Cross-Section | 0.25 m × 0.30 m |

| Column Cross-Section | 0.30 m × 0.30 m | |

| Cracking Factor (Beams) | 0.7 | |

| Cracking Factor (Columns) | 0.8 | |

| Material | Concrete Young’s Modulus | 21,458,890.83 kN/m² |

| Loads | Dead Load | 4.9 kN/m² |

| Live Load | 1.9 kN/m² | |

| Dead Load Weight Coefficient | 1.0 | |

| Live Load Weight Coefficient | 0.15 | |

| Seismic Parameters | Base Shear Coefficient | 0.1488 |

| Vertical Distribution Coefficient | 1.0 | |

| Accidental Torsion Coefficient | 0.05 | |

| Drift Amplification Factor (for Inelastic Drift) | 6.0 | |

| Maximum Allowable Drift | 0.02 |

| Inter-Story Drift X | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Story | GPT | GPT+MCP | OPENSEES | ETABS | |

| A | 2 | 0.009 | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.013 | |

| 1 | 0.007 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.012 | ||

| Storey | GPT | GPT+MCP | OPENSEES | ETABS |

| A | 0.047 | 0.01264 | 0.01264 | 0.01282 |

| Case | GPT | GPT+MCP | OPENSEES | ETABS |

| A | 10.09 | 13.969 | 13.969 | 13.97 |

| Case | GPT | GPT+MCP | OPENSEES | ETABS |

| A | 0.38 | 0.485 | 0.485 | 0.489 |

| GPT | GPT+MCP | OPENSEES | ||||

| Case | X | Y | X | Y | X | Y |

| A | 266.529 | 235.335 | 1.427 | 1.427 | 1.427 | 1.427 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).