1. Introduction

The primary pathological feature of carotid artery stenosis (CAS) is the formation and progressive development of atherosclerotic plaques, with resulting luminal narrowing and plaque instability being key mechanisms that lead to ischemic cerebrovascular events. Hemodynamic impairment may cause hypoperfusion-related cerebral infarction, while plaque rupture can result in distal thromboembolism . The risk posed by atherosclerotic plaque rupture is often more severe than the luminal narrowing caused by the plaque itself, with approximately 20–30% of strokes attributed to the rupture of vulnerable plaques [1,2]. Vulnerable plaques are compositionally complex, including necrotic cores, thin fibrous caps, inflammatory cell infiltration, and calcification [3], and represent one of the most potentially dangerous forms of atherosclerotic lesions [4]. Therefore, timely identification of vulnerable plaques is of great importance for the prevention of stroke.

It is noteworthy that carotid artery stenosis is also an important risk factor for vascular cognitive impairment (VCI). With the aging of the population and the increasing number of patients with cerebrovascular diseases in China, the prevalence of VCI has shown a year-by-year upward trend. VCI is a preventable and treatable cognitive disorder, and early intervention can reduce the occurrence of related symptoms and significantly improve quality of life.

Inflammation is a significant contributor to atherosclerotic plaque formation [5], and assessing the progression of atherosclerosis through inflammation-related markers is becoming a growing focus of research. The neutrophil count plus monocyte count to lymphocyte count ratio (NMLR) is a novel inflammatory marker, defined as the ratio of the sum of peripheral blood neutrophil and monocyte counts to lymphocyte count. It can be used to predict the prognosis of inflammatory diseases [6]. Studies have found that patients with sepsis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or heart failure who exhibit elevated NMLR have higher all-cause mortality rates[7,8,9]. Meanwhile, in patients with schizophrenia, NLR and MLR are negatively correlated with cognitive function [10]. In this study, data from CAS patients in our hospital were collected and analyzed, and a mediation model was applied to examine the potential mediating effect of plaque stability in the association between NMLR and cognitive function, to preliminarily explore the underlying mechanism and provide a scientific basis for the prevention and intervention of VCI.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population

Inclusion criteria: (1) patients who underwent head and neck CTA after admission and were diagnosed with CAS according to the Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Carotid Artery Stenosis; (2) first-time CEA treatment, with carotid plaque specimens obtained intraoperatively and subjected to pathological examination; (4) ≥6 years of education, able to complete the MoCA test; (5) complete clinical data available.

Exclusion criteria: (1) presence of benign or malignant tumors (benign tumors were excluded only if intervention was required); (2) concurrent infection; (3) history of trauma or surgery within the past month; (4) concomitant autoimmune disease; (5) use of anti-inflammatory drugs (such as glucocorticoids or immunosuppressants) or use of antibiotics within 1 month before enrollment.

This study retrospectively included 211 CAS patients who were hospitalized and treated in the Department of Vascular Surgery, Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, the Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University Medical School, from January 2024 to June 2025. According to carotid plaque specimens obtained during CEA, patients were divided into the plaque-stable group (n=104) and the vulnerable plaque group (n=107).

2.2. Data Collection

General data collection: Patient information such as sex, age, hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg or use of antihypertensive drugs), diabetes (fasting blood glucose ≥7.0 mmol/L or use of hypoglycemic agents or insulin), and history of coronary heart disease were recorded, along with preoperative laboratory data including triglycerides, total cholesterol, serum albumin, low-density lipoprotein (LDL), C-reactive protein, neutrophil count, monocyte count, and lymphocyte count.

Calculation of NMLR: (neutrophil count + monocyte count)/lymphocyte count = NMLR; calculation of NLR: neutrophil count/lymphocyte count = NLR.

2.3. Cognitive Function Assessment

Cognitive function assessment: In this study, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) scale was used, which covers seven domains, including visuospatial/executive function, naming, attention, language, abstraction, delayed recall, and orientation [11].

The total score of the scale is 30 points.

For patients with 12 years of education or less, 1 point is added to the total score.

Patients with a total score of 26 or higher are considered to have normal cognitive function; those scoring below 26 are considered to have mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using R version 4.3.3 statistical software. Quantitative data with normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (±s), and comparisons between groups were performed using independent-sample t-tests; skewed quantitative data were expressed as M (Q1, Q3), and between-group comparisons were conducted using the Mann-Whitney U test; categorical data were expressed as counts, and comparisons between groups were made using the χ2 test. Multivariate logistic regression was used to analyze the factors associated with plaque stability in CAS patients. The predictive value of NMLR for plaque stability was assessed using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, calculating the area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity, and specificity. A two-tailed test was performed, with a significance level of α=0.05.

3. Result

3.1. Comparison of Baseline Characteristics Between Stable and Vulnerable Plaque Groups

According to plaque stability, patients were divided into the stable plaque group (n=104) and the vulnerable plaque group (n=107). There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of sex, hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease, or fasting plasma glucose (all P > 0.05).

Compared with the stable plaque group, patients in the vulnerable plaque group had lower age, history of stroke, triglycerides, serum albumin, hemoglobin, NMLR, and MoCA scores, and these differences were statistically significant (all P < 0.05); detailed results are shown in

Table 1.

3.2. Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis of the Association Between Plaque Vulnerability and NMLR

In all patients, groups were classified according to plaque stability, and risk factors for carotid plaque vulnerability were analyzed. The analysis revealed that a history of stroke, NMLR, and MoCA scores were independent risk factors for plaque stability. Plaque vulnerability was significantly positively correlated with a history of stroke and NMLR, and negatively correlated with MoCA scores.

Table 2.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of factors associated with carotid plaque stability.

Table 2.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of factors associated with carotid plaque stability.

| Variable |

P |

OR (95%CI) |

| Stroke |

0.014 |

2.50 (1.20 ~ 5.21) |

| Smoking |

0.992 |

0.99 (0.35 ~ 2.86) |

| Age |

0.234 |

0.97 (0.92 ~ 1.02) |

| TC |

0.070 |

0.60 (0.34 ~ 1.04) |

| Albumin |

0.443 |

0.94 (0.81 ~ 1.10) |

| Hemoglobin |

0.253 |

1.02 (0.99 ~ 1.04) |

| NMLR |

<.001 |

4.51 (2.43 ~ 8.38) |

| MoCA |

0.015 |

0.84 (0.73 ~ 0.97) |

3.3. Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis of the Association Between Cognitive Function and NMLR

In all patients, groups were classified based on MoCA scores, with MoCA ≥26 indicating the normal cognition group and MoCA ≤25 as the mild cognitive impairment (MCI) group.

Risk factors for cognitive function were analyzed. The analysis showed that a history of stroke, age, and NMLR were independent risk factors for cognitive function, each exhibiting a significant positive correlation.

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of the association between NMLR and cognitive function.

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of the association between NMLR and cognitive function.

| Variable |

P |

OR (95%CI) |

| Stroke |

0.034 |

2.59 (1.08 ~ 6.23) |

| Smoking |

0.603 |

0.78 (0.32 ~ 1.95) |

| Age |

<.001 |

1.18 (1.10 ~ 1.25) |

| Albumin |

0.766 |

1.03 (0.86 ~ 1.23) |

| LDL |

0.712 |

1.09 (0.68 ~ 1.77) |

| NMLR |

<.001 |

4.22 (1.98 ~ 8.96) |

3.4. Mediation Effect of Plaque Vulnerability in the Association Between NMLR and Cognitive Function

Table 4.

Path analysis results of NMLR, plaque stability, and cognitive function.

Table 4.

Path analysis results of NMLR, plaque stability, and cognitive function.

| Path |

Relationship |

P |

β(95%CI) |

| NMLR→Vulnerability |

Exposure→ Mediator |

<.001 |

1.31(0.77~1.86) |

| NMLR→MoCA |

Exposure→ Outcome |

<.001 |

-1.18(-1.68~-0.67) |

| Vulnerability→MoCA |

Mediator→Outcome |

<.001 |

-1.44(-2.33~-0.64) |

Table 5.

Mediation effect estimates of NMLR, plaque stability, and cognitive function.

Table 5.

Mediation effect estimates of NMLR, plaque stability, and cognitive function.

| Effect |

β(95%CI) |

P |

Mediation(%) |

| Indirect |

-0.14(-0.28~-0.03) |

<.001 |

10.58 |

| Direct |

-1.19(-1.68~-0.70) |

<.001 |

89.42 |

| Total |

-1.33(-1.83~-0.83) |

<.001 |

100 |

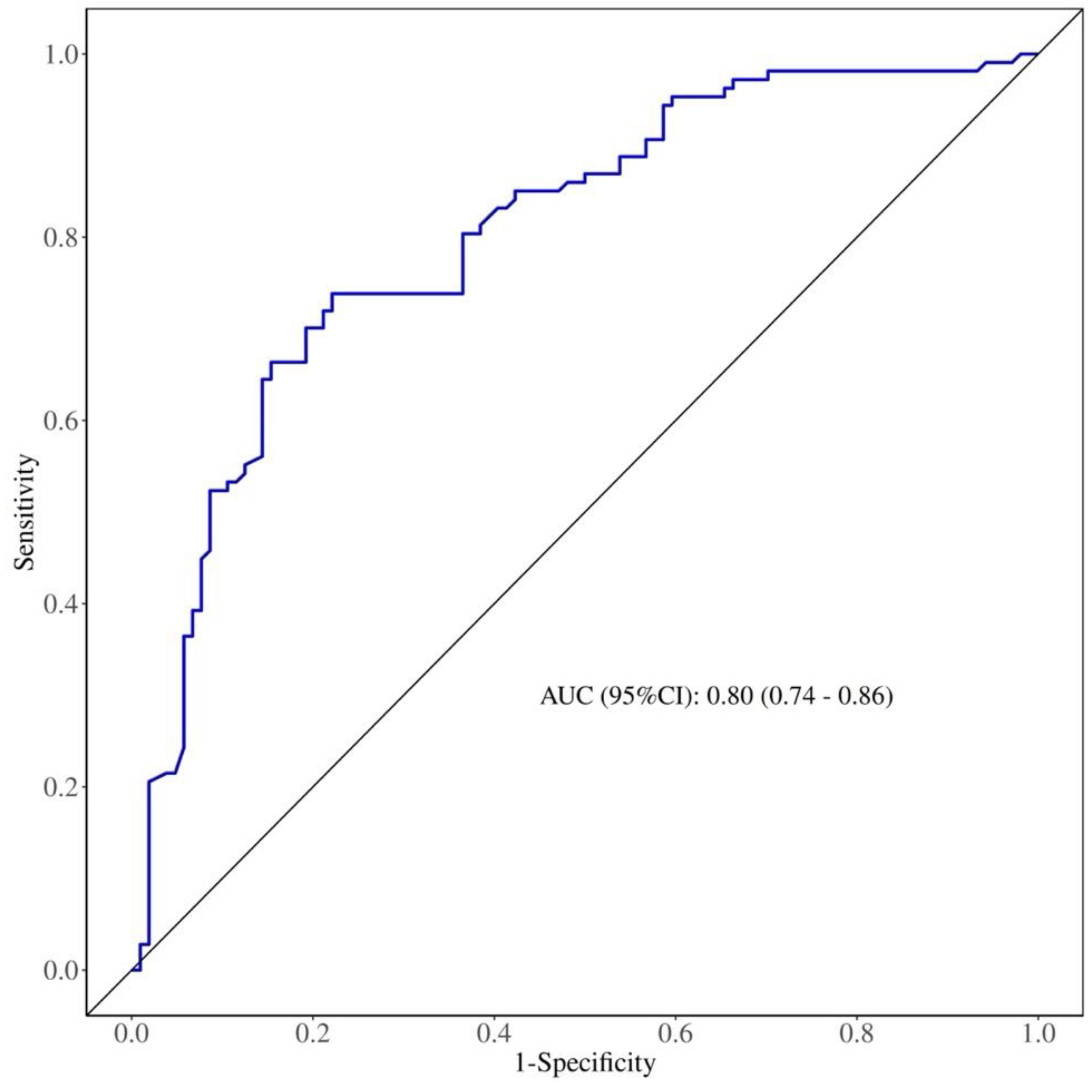

3.5. Predictive Value of NMLR for Carotid Plaque Stability in Patients with CAS.

| |

AUC |

Cutoff |

Sensitivity |

Specificity |

P |

| NMLR |

0.80 |

2.525 |

77.9% |

73.8% |

<0.001 |

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of NMLR for predicting carotid plaque stability in patients with CAS.

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of NMLR for predicting carotid plaque stability in patients with CAS.

4. Discussion

This retrospective study analyzed clinical data from patients with carotid artery stenosis (CAS) to explore the mediating role of carotid atherosclerotic plaque stability in the connection between the neutrophil-plus-monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (NMLR) and cognitive function.

The results indicated that NMLR was significantly associated with plaque stability, and plaque vulnerability mediated the association between NMLR and cognitive function.

The stability of atherosclerotic plaques is regulated by multiple mechanisms, among which the inflammatory response is a key driving factor. Circulating inflammatory cells, mainly neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes, were found in this study to be closely associated with plaque vulnerability, with elevated neutrophil and monocyte counts and decreased lymphocyte counts. This finding is consistent with previous basic research, both domestically and internationally, which proposed mechanisms such as “neutrophil infiltration accelerating plaque rupture” and “monocyte-mediated endothelial injury” [12,13]. Neutrophils directly exacerbate plaque instability by releasing neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). On one hand, NETs induce vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) death, resulting in an enlarged necrotic core and thinning of the fibrous cap, thereby increasing plaque instability; on the other hand, they activate macrophages, promote the expression of the pro-inflammatory factor pro-IL-1β, and recruit monocytes to infiltrate plaques, forming a vicious inflammatory cycle [14–16]. Pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages secrete IL-1β and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which degrade the fibrous cap structure, whereas M4 macrophages further amplify the inflammatory cascade by recruiting neutrophils and inducing NET formation[17]–[19] . In immune cell regulation, lymphocytes differentiate into T and B cells. Regulatory T cells (Treg) derived from CD4+ T cells suppress inflammatory responses by secreting IL-10 and TGF-β, thereby slowing the progression of atherosclerosis[20],[21].

Meanwhile, CD8+ T cells exhibit activated and cytotoxic phenotypes within plaques, but certain subtypes (e.g., CD8+ Treg) can exert protective effects by suppressing Th1 responses[22],[23] . Additionally, B1 cells secrete IgM antibodies with antioxidant properties, directly neutralizing oxidized lipids and enhancing plaque stability [24].

Additionally, previous studies have shown that plaque stability is also associated with C-reactive protein (CRP), LDL, and smoking[25]–[27] . Therefore, in this study, CRP, smoking, and LDL—commonly used clinically to assess systemic inflammation—were analyzed as potential risk factors. However, they did not retain independent predictive value in the multivariate analysis. This finding suggests that, compared with single inflammatory or lipid markers, NMLR integrates information from multiple immune cell types and can more accurately reflect plaque inflammatory burden.

This observation is consistent with Ruan et al.'s findings regarding the predictive value of NLR[28] , but by incorporating monocyte information, NMLR may more sensitively reflect macrophage infiltration and oxidative stress within plaques (e.g., monocyte counts were significantly elevated in the vulnerable plaque group)[29] .

In this study, patients were classified into the NC group and the MCI group based on whether their MoCA score was ≥26. Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that NMLR was an independent risk factor for cognitive function. Mediation analysis indicated that carotid plaque vulnerability mediated the association between NMLR and cognitive function, accounting for 10.58% of the effect. This suggests that vulnerable carotid plaques may be a potential risk factor through which NMLR affects cognitive decline. Inflammation not only acts through the immune system but also interacts with traditional cerebrovascular risk factors, amplifying their harmful effects [30]. Inflammation is also considered to play an important role in cognitive impairment associated with vascular CI [31]or Alzheimer's disease [32]. During vascular diseases such as atherosclerosis or ischemic stroke, neutrophils exacerbate tissue damage by increasing reactive oxygen species (ROS) release, leading to neuronal dysfunction, cognitive impairment, or endothelial dysfunction and increased permeability [33],[34]. However, cognitive decline may also result from a reduction in lymphocyte counts. Firstly, Hou et al. demonstrated that increased neutrophil counts are associated with high ROS generation, which leads to lymphocyte DNA damage and lymphocyte death [35]. Because lymphocytes in patients are more sensitive to ROS than those in healthy individuals, peripheral lymphocyte counts decrease[36] . On the other hand, studies have suggested that microemboli may underlie MCI in patients with carotid artery stenosis [37]. This is similar to the mediation effect observed in this study, where carotid plaque vulnerability mediates the relationship between NMLR and cognitive decline. Plaque vulnerability increases due to intraplaque hemorrhage, necrotic core enlargement, and fibrous cap thinning, leading to plaque rupture and microembolus formation.

Therefore, NMLR levels may directly or indirectly reflect the extent of cognitive decline.

NMLR integrates the pro-inflammatory effects of neutrophils and monocytes with the protective effects of lymphocytes, more sensitively reflecting macrophage infiltration and oxidative stress within plaques. NMLR can not only directly contribute to cognitive decline but also indirectly affect cognition by promoting plaque vulnerability, providing a novel inflammatory target for the prevention and management of stroke and VCI. NMLR may serve as a noninvasive biomarker for screening the risk of carotid plaque rupture to prevent ischemic stroke and for assessing the risk of vascular cognitive impairment (VCI), offering a basis for early intervention.

References

- Pelisek J, Eckstein HH, Zernecke A. Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Carotid Plaque Vulnerability: Impact on Ischemic Stroke. Arch Immunol Ther Exp. 2012;60(6):431-442. [CrossRef]

- Willey JZ, Pasterkamp G. The Role of the Vulnerable Carotid Plaque in Embolic Stroke of Unknown Source. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2022;79(22):2200-2202. [CrossRef]

- Barrett HE, Van Der Heiden K, Farrell E, Gijsen FJH, Akyildiz AC. Calcifications in atherosclerotic plaques and impact on plaque biomechanics. Journal of Biomechanics. 2019;87:1-12. [CrossRef]

- Cires-Drouet RS, Mozafarian M, Ali A, Sikdar S, Lal BK. Imaging of high-risk carotid plaques: Ultrasound. Seminars in Vascular Surgery. 2017;30(1):44-53. [CrossRef]

- Geovanini GR, Libby P. Atherosclerosis and inflammation: Overview and updates. Clinical Science. 2018;132(12):1243-1252. [CrossRef]

- Pang Y, Shao H, Yang Z, et al. The (Neutrophils + Monocyte)/Lymphocyte Ratio Is an Independent Prognostic Factor for Progression-Free Survival in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma Patients Treated With BCD Regimen. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1617. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Yuan M, Ma Y, et al. The Admission (Neutrophil+Monocyte)/Lymphocyte Ratio Is an Independent Predictor for In-Hospital Mortality in Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:870176. [CrossRef]

- Guo M, He W, Mao X, Luo Y, Zeng M. Association between ICU admission (neutrophil + monocyte)/lymphocyte ratio and 30-day mortality in patients with sepsis: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2023;23(1):697. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Ge S, Liu J, et al. Peripheral Blood NMLR Can Predict 5-Year All-Cause Mortality in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. COPD. 2025;Volume 20:95-105. [CrossRef]

- Syahna R, Amin MM, Camellia V, Effendy E, Yamamoto Z. Cognitive impairment and elevated neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio in schizophrenia. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. 2025;35(1):16-20. [CrossRef]

- Yu J, Li J, Huang X. The beijing version of the montreal cognitive assessment as a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment: A community-based study. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12(1):156. [CrossRef]

- Kounis NG, Koniari I, Plotas P, et al. Inflammation, Thrombosis, and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Acute Coronary Syndromes. Angiology. 2021;72(1):6-8. [CrossRef]

- Drechsler M, Megens RTA, Van Zandvoort M, Weber C, Soehnlein O. Hyperlipidemia-Triggered Neutrophilia Promotes Early Atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2010;122(18):1837-1845. [CrossRef]

- Schumski A, Ortega-Gómez A, Wichapong K, et al. Endotoxinemia Accelerates Atherosclerosis Through Electrostatic Charge–Mediated Monocyte Adhesion. Circulation. 2021;143(3):254-266. [CrossRef]

- Pieterse E, Rother N, Yanginlar C, Hilbrands LB, Van Der Vlag J. Neutrophils Discriminate between Lipopolysaccharides of Different Bacterial Sources and Selectively Release Neutrophil Extracellular Traps. Front Immunol. 2016;7. [CrossRef]

- Döring Y, Libby P, Soehnlein O. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Participate in Cardiovascular Diseases: Recent Experimental and Clinical Insights. Circulation Research. 2020;126(9):1228-1241. [CrossRef]

- Maretti-Mira AC, Golden-Mason L, Salomon MP, Kaplan MJ, Rosen HR. Cholesterol-Induced M4-Like Macrophages Recruit Neutrophils and Induce NETosis. Front Immunol. 2021;12:671073. [CrossRef]

- Barrett TJ. Macrophages in Atherosclerosis Regression. ATVB. 2020;40(1):20-33. [CrossRef]

- Khoury MK, Yang H, Liu B. Macrophage Biology in Cardiovascular Diseases. ATVB. 2021;41(2). [CrossRef]

- Bäck M, Yurdagul A, Tabas I, Öörni K, Kovanen PT. Inflammation and its resolution in atherosclerosis: mediators and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Cardiol. Published online March 7, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Ley K. Role of the adaptive immune system in atherosclerosis. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2020;48(5):2273-2281. [CrossRef]

- Van Duijn J, Kritikou E, Benne N, et al. CD8+ T-cells contribute to lesion stabilization in advanced atherosclerosis by limiting macrophage content and CD4+ T-cell responses. Cardiovascular Research. 2019;115(4):729-738. [CrossRef]

- Schäfer S, Zernecke A. CD8+ T Cells in Atherosclerosis. Cells. 2020;10(1):37. [CrossRef]

- Mangge H, Prüller F, Schnedl W, Renner W, Almer G. Beyond Macrophages and T Cells: B Cells and Immunoglobulins Determine the Fate of the Atherosclerotic Plaque. IJMS. 2020;21(11):4082. [CrossRef]

- Kumagai S, Amano T, Takashima H, et al. Impact of cigarette smoking on coronary plaque composition. Coronary Artery Disease. 2015;26(1):60-65. [CrossRef]

- Pan Z, Guo H, Wang Q, et al. Relationship between subclasses low-density lipoprotein and carotid plaque. Translational Neuroscience. 2022;13(1):30-37. [CrossRef]

- Scimeca M, Montanaro M, Cardellini M, et al. High sensitivity C-reactive protein increases the risk of carotid plaque instability in male dyslipidemic patients. Diagnostics. 2021;11(11):2117. [CrossRef]

- Ruan W, Wang M, Sun C, et al. Correlation between neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and stability of carotid plaques. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 2022;212:107055. [CrossRef]

- Gisterå A, Hansson GK. The immunology of atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017;13(6):368-380. [CrossRef]

- Li T, Huang Y, Cai W, et al. Age-related cerebral small vessel disease and inflammaging. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(10):932. [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg GA. Inflammation and white matter damage in vascular cognitive impairment. Stroke. 2009;40(3_suppl_1). [CrossRef]

- Krstic D, Knuesel I. Deciphering the mechanism underlying late-onset alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9(1):25-34. [CrossRef]

- Aries ML, Hensley-McBain T. Neutrophils as a potential therapeutic target in alzheimer’s disease. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1123149. [CrossRef]

- Lee NT, Ong LK, Gyawali P, et al. Role of purinergic signalling in endothelial dysfunction and thrombo-inflammation in ischaemic stroke and cerebral small vessel disease. Biomolecules. 2021;11(7):994. [CrossRef]

- Hou JH, Ou YN, Xu W, et al. Association of peripheral immunity with cognition, neuroimaging, and alzheimer’s pathology. Alz Res Therapy. 2022;14(1):29. [CrossRef]

- Ponce DP, Salech F, SanMartin CD, et al. Increased susceptibility to oxidative death of lymphocytes from alzheimer patients correlates with dementia severity. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2014;11(9):892-898.

- Takasugi J, Miwa K, Watanabe Y, et al. Cortical cerebral microinfarcts on 3T magnetic resonance imaging in patients with carotid artery stenosis. Stroke. 2019;50(3):639-644. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).