Submitted:

25 July 2025

Posted:

30 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Baseline Assessments

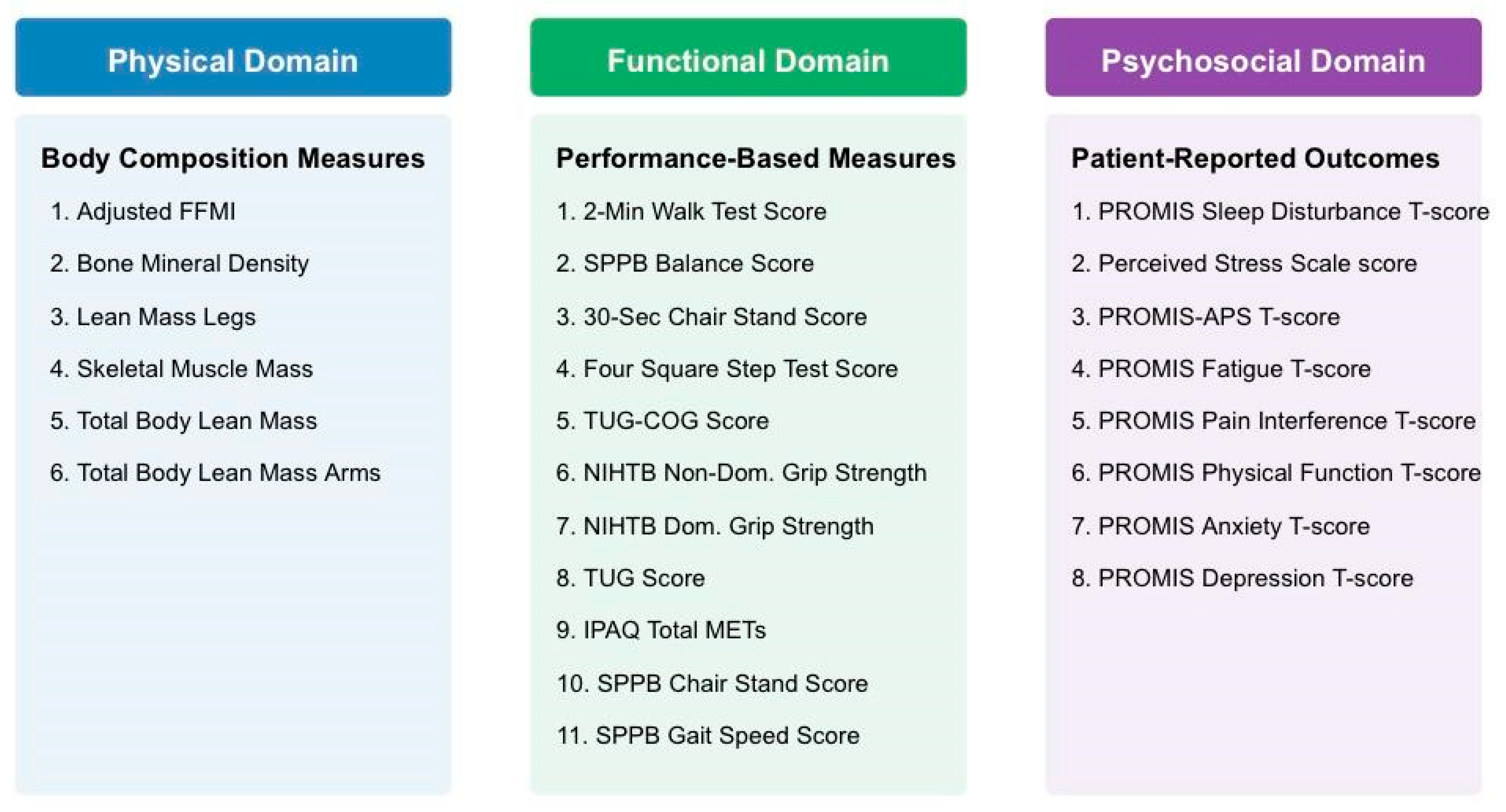

2.3. Frailty Domains and Variable Selection

2.4. Imaging Measures

2.5. Cognitive Measures

2.6. Sample Size Considerations

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Factor Analysis

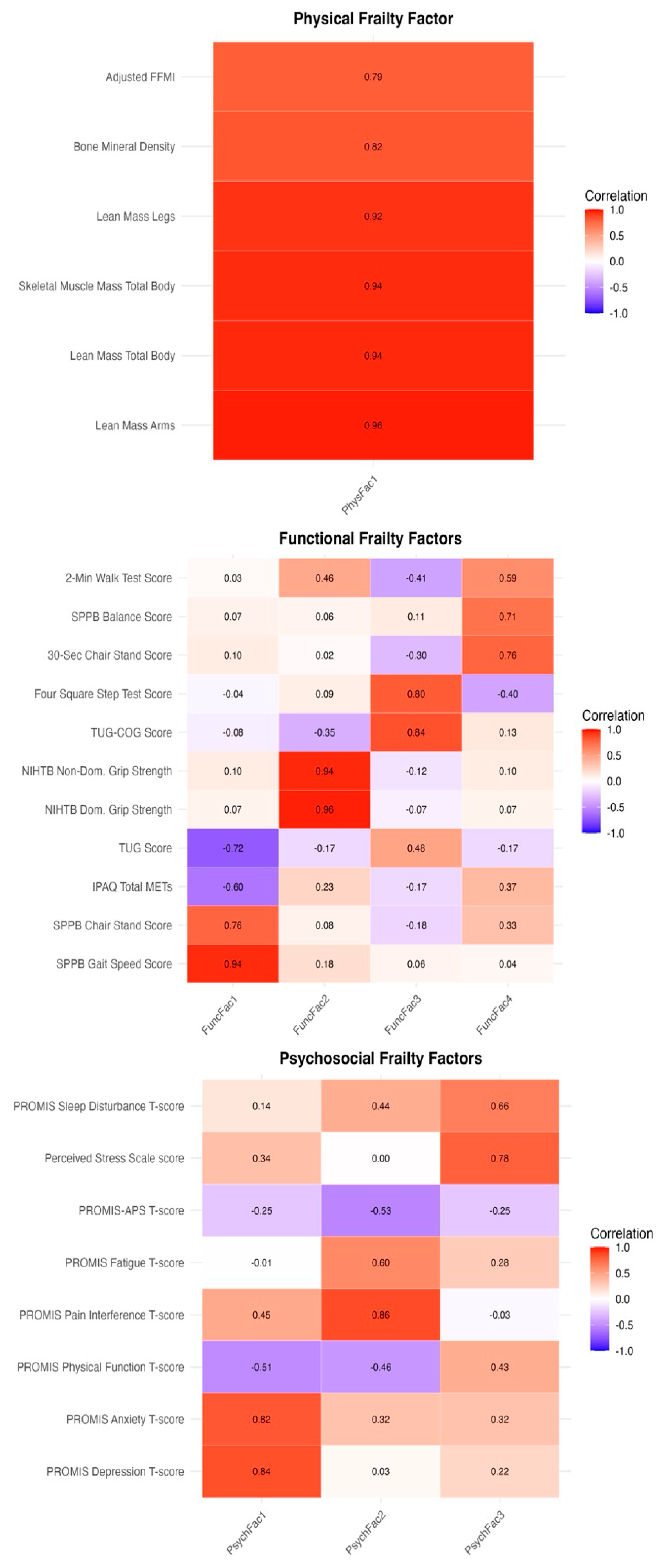

3.2.1. Physical Frailty Domain

3.2.2. Functional Frailty Domain

3.2.3. Psychosocial Frailty Domain

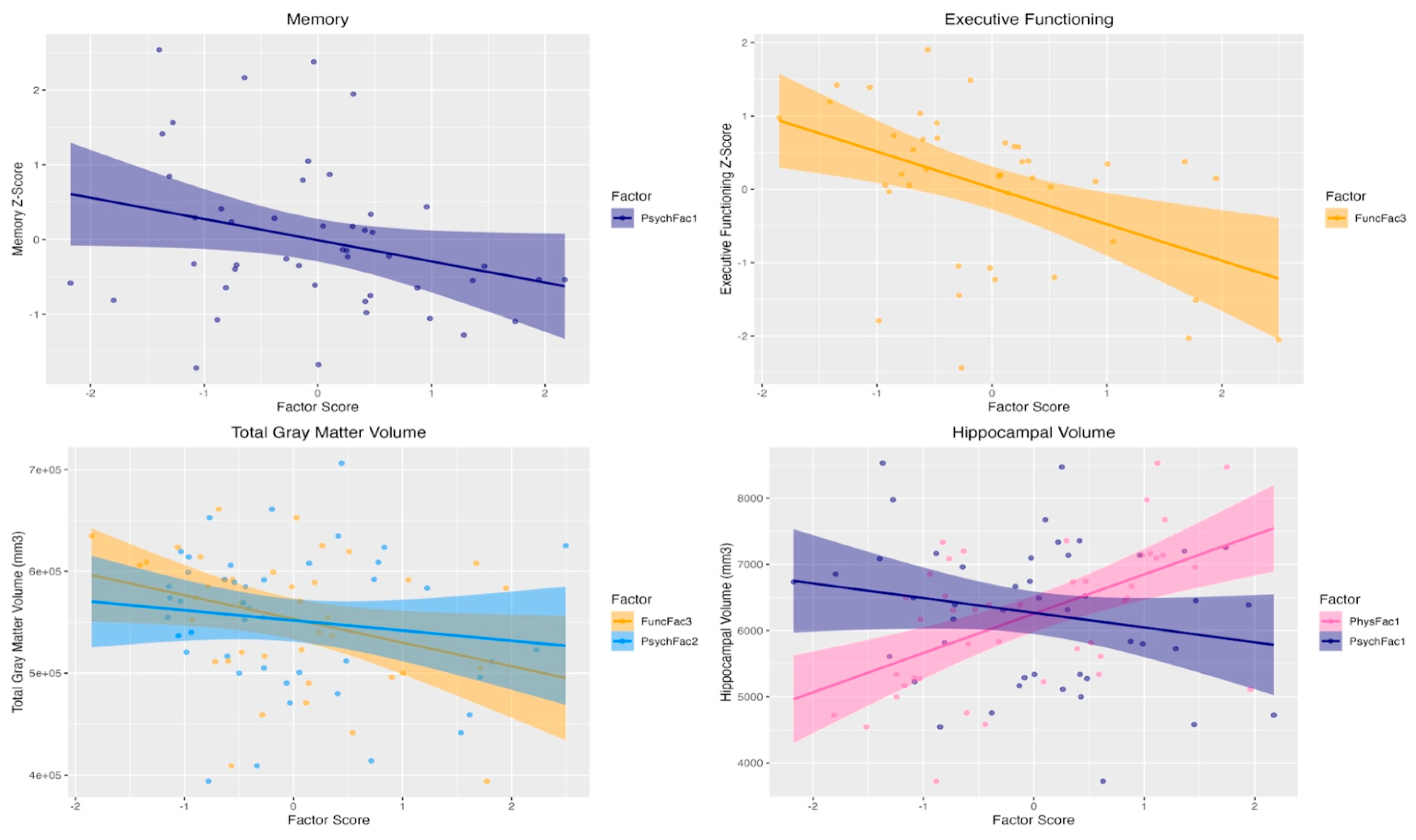

3.3. Associations with Cognition and Brain Volumes

4. Discussion

4.1. Physical Frailty

4.2. Functional Frailty

4.3. Psychosocial Frailty

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| APOE | Apolipoprotein E |

| Aβ | Amyloid-β (amyloid-beta) |

| BDNF | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| CA1 | Cornu Ammonis 1 (hippocampal subfield) |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| DXA | Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry |

| EFA | Exploratory factor analysis |

| FFMI | Fat-free mass index |

| FSST | Four Square Step Test |

| HIPAA | Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IPAQ | International Physical Activity Questionnaire |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| MCI | Mild cognitive impairment |

| MET | Metabolic equivalent of task |

| miR | microRNA |

| MoCA | Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| NCT | National Clinical Trial (ClinicalTrials.gov) identifier |

| NGF | Nerve growth factor |

| NIH | National Institutes of Health |

| NIHTB | NIH Toolbox |

| NIHTB-CB | NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery |

| NIA-AA | National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer’s Association |

| PET | Positron emission tomography |

| PREVENTION | Precision Recommendations for Environmental Variables, Exercise, Nutrition and Training Interventions to Optimize Neurocognition (trial) |

| PRO | Patient-reported outcome |

| PROMIS | Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System |

| PSS-4 | Perceived Stress Scale-4 |

| SAS | Statistical Analysis System |

| SCD | Subjective cognitive decline |

| SMART | Study of Mental and Resistance Training (trial) |

| SPPB | Short Physical Performance Battery |

| TDP-43 | Transactive response DNA-binding protein 43 |

| TIV | Total intracranial volume |

| TMT | Trail Making Test |

| TUG | Timed Up and Go |

| TUG-COG | Timed Up and Go with cognitive dual-task |

| VPA | Verbal Paired Associates |

| VR | Visual Reproduction |

| WCG | Western Copernicus Group |

| WMS | Wechsler Memory Scale |

References

- Comas-Herrera, A.; International, A.D.; Aguzzoli, E.; Farina, N.; Read, S.; Evans-Lacko, S. World Alzheimer Report 2024: Global Changes in Attitudes to Dementia. 2024.

- Gustavsson, A.; Norton, N.; Fast, T.; Frölich, L.; Georges, J.; Holzapfel, D.; Kirabali, T.; Krolak-Salmon, P.; Rossini, P.M.; Ferretti, M.T.; et al. Global Estimates on the Number of Persons across the Alzheimer’s Disease Continuum. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2023, 19, 658–670, . [CrossRef]

- Grundke-Iqbal, I.; Iqbal, K.; Tung, Y.C.; Quinlan, M.; Wisniewski, H.M.; Binder, L.I. Abnormal Phosphorylation of the Microtubule-Associated Protein Tau (Tau) in Alzheimer Cytoskeletal Pathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1986, 83, 4913–4917, . [CrossRef]

- Glenner, G.G.; Wong, C.W. Alzheimer’s Disease: Initial Report of the Purification and Characterization of a Novel Cerebrovascular Amyloid Protein. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 1984, 120, 885–890, . [CrossRef]

- Jack, C.R.; Bennett, D.A.; Blennow, K.; Carrillo, M.C.; Dunn, B.; Haeberlein, S.B.; Holtzman, D.M.; Jagust, W.; Jessen, F.; Karlawish, J.; et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a Biological Definition of Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Dement 2018, 14, 535–562, . [CrossRef]

- Bateman, R.J.; Xiong, C.; Benzinger, T.L.S.; Fagan, A.M.; Goate, A.; Fox, N.C.; Marcus, D.S.; Cairns, N.J.; Xie, X.; Blazey, T.M.; et al. Clinical and Biomarker Changes in Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer’s Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2012, 367, 795–804, . [CrossRef]

- Young-Pearse, T.L.; Lee, H.; Hsieh, Y.-C.; Chou, V.; Selkoe, D.J. Moving beyond Amyloid and Tau to Capture the Biological Heterogeneity of Alzheimer’s Disease. Trends in Neurosciences 2023, 46, 426–444, . [CrossRef]

- Verdi, S.; Kia, S.M.; Yong, K.X.X.; Tosun, D.; Schott, J.M.; Marquand, A.F.; Cole, J.H. Revealing Individual Neuroanatomical Heterogeneity in Alzheimer Disease Using Neuroanatomical Normative Modeling. Neurology 2023, 100, e2442–e2453, . [CrossRef]

- Duara, R.; Barker, W. Heterogeneity in Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnosis and Progression Rates: Implications for Therapeutic Trials. Neurotherapeutics 2022, 19, 8–25, . [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.A.; Arvanitakis, Z.; Bang, W.; Bennett, D.A. Mixed Brain Pathologies Account for Most Dementia Cases in Community-Dwelling Older Persons. Neurology 2007, 69, 2197–2204, . [CrossRef]

- Boyle, P.A.; Yu, L.; Wilson, R.S.; Leurgans, S.E.; Schneider, J.A.; Bennett, D.A. Person-Specific Contribution of Neuropathologies to Cognitive Loss in Old Age. Ann Neurol 2018, 83, 74–83, . [CrossRef]

- Nelson, P.T.; Alafuzoff, I.; Bigio, E.H.; Bouras, C.; Braak, H.; Cairns, N.J.; Castellani, R.J.; Crain, B.J.; Davies, P.; Del Tredici, K.; et al. Correlation of Alzheimer Disease Neuropathologic Changes with Cognitive Status: A Review of the Literature. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2012, 71, 362–381, . [CrossRef]

- Tosun, D.; Demir, Z.; Veitch, D.P.; Weintraub, D.; Aisen, P.; Jack, C.R.; Jagust, W.J.; Petersen, R.C.; Saykin, A.J.; Shaw, L.M.; et al. Contribution of Alzheimer’s Biomarkers and Risk Factors to Cognitive Impairment and Decline across the Alzheimer’s Disease Continuum. Alzheimers Dement 2022, 18, 1370–1382, . [CrossRef]

- Bohn, L.; Zheng, Y.; McFall, G.P.; Andrew, M.K.; Dixon, R.A. Frailty in Motion: Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease Cohorts Display Heterogeneity in Multimorbidity Classification and Longitudinal Transitions. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2025, 104, 732–750, . [CrossRef]

- Fried, L.P.; Tangen, C.M.; Walston, J.; Newman, A.B.; Hirsch, C.; Gottdiener, J.; Seeman, T.; Tracy, R.; Kop, W.J.; Burke, G.; et al. Frailty in Older Adults: Evidence for a Phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001, 56, M146-156, . [CrossRef]

- Clegg, A.; Young, J.; Iliffe, S.; Rikkert, M.O.; Rockwood, K. Frailty in Elderly People. Lancet 2013, 381, 752–762, . [CrossRef]

- Vermeiren, S.; Vella-Azzopardi, R.; Beckwée, D.; Habbig, A.-K.; Scafoglieri, A.; Jansen, B.; Bautmans, I.; Gerontopole Brussels Study group Frailty and the Prediction of Negative Health Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2016, 17, 1163.e1-1163.e17, . [CrossRef]

- Kojima, G.; Iliffe, S.; Walters, K. Frailty Index as a Predictor of Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Age Ageing 2018, 47, 193–200, . [CrossRef]

- Buchman, A.S.; Boyle, P.A.; Wilson, R.S.; Tang, Y.; Bennett, D.A. Frailty Is Associated with Incident Alzheimer’s Disease and Cognitive Decline in the Elderly. Psychosom Med 2007, 69, 483–489, . [CrossRef]

- Buchman, A.S.; Schneider, J.A.; Leurgans, S.; Bennett, D.A. Physical Frailty in Older Persons Is Associated with Alzheimer Disease Pathology. Neurology 2008, 71, 499–504, . [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, C.; Garagnani, P.; Morsiani, C.; Conte, M.; Santoro, A.; Grignolio, A.; Monti, D.; Capri, M.; Salvioli, S. The Continuum of Aging and Age-Related Diseases: Common Mechanisms but Different Rates. Front Med (Lausanne) 2018, 5, 61, . [CrossRef]

- Walston, J.; Hadley, E.C.; Ferrucci, L.; Guralnik, J.M.; Newman, A.B.; Studenski, S.A.; Ershler, W.B.; Harris, T.; Fried, L.P. Research Agenda for Frailty in Older Adults: Toward a Better Understanding of Physiology and Etiology: Summary from the American Geriatrics Society/National Institute on Aging Research Conference on Frailty in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006, 54, 991–1001, . [CrossRef]

- Wallace, L.M.K.; Theou, O.; Godin, J.; Andrew, M.K.; Bennett, D.A.; Rockwood, K. Investigation of Frailty as a Moderator of the Relationship between Neuropathology and Dementia in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Data from the Rush Memory and Aging Project. The Lancet Neurology 2019, 18, 177–184, . [CrossRef]

- Koch, G.; Belli, L.; Giudice, T.L.; Lorenzo, F.D.; Sancesario, G.M.; Sorge, R.; Bernardini, S.; Martorana, A. Frailty among Alzheimer’s Disease Patients. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2013, 12, 507–511, . [CrossRef]

- Gabelle, A.; Schraen, S.; Gutierrez, L.-A.; Pays, C.; Rouaud, O.; Buée, L.; Touchon, J.; Helmer, C.; Lambert, J.-C.; Berr, C. Plasma β-Amyloid 40 Levels Are Positively Associated with Mortality Risks in the Elderly. Alzheimers Dement 2015, 11, 672–680, . [CrossRef]

- Mitnitski, A.B.; Mogilner, A.J.; Rockwood, K. Accumulation of Deficits as a Proxy Measure of Aging. ScientificWorldJournal 2001, 1, 323–336, . [CrossRef]

- Rockwood, K.; Mitnitski, A. Frailty in Relation to the Accumulation of Deficits. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2007, 62, 722–727, . [CrossRef]

- Vella Azzopardi, R.; Beyer, I.; Vermeiren, S.; Petrovic, M.; Van Den Noortgate, N.; Bautmans, I.; Gorus, E. Increasing Use of Cognitive Measures in the Operational Definition of Frailty—A Systematic Review. Ageing Research Reviews 2018, 43, 10–16, . [CrossRef]

- Dent, E.; Kowal, P.; Hoogendijk, E.O. Frailty Measurement in Research and Clinical Practice: A Review. Eur J Intern Med 2016, 31, 3–10, . [CrossRef]

- Panza, F.; Lozupone, M.; Solfrizzi, V.; Sardone, R.; Dibello, V.; Di Lena, L.; D’Urso, F.; Stallone, R.; Petruzzi, M.; Giannelli, G.; et al. Different Cognitive Frailty Models and Health- and Cognitive-Related Outcomes in Older Age: From Epidemiology to Prevention. J Alzheimers Dis 2018, 62, 993–1012, . [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Mitnitski, A.; Rockwood, K. Age-Related Deficit Accumulation and the Risk of Late-Life Dementia. Alzheimers Res Ther 2014, 6, 54, . [CrossRef]

- Searle, S.D.; Rockwood, K. Frailty and the Risk of Cognitive Impairment. Alzheimers Res Ther 2015, 7, 54, . [CrossRef]

- De Witte, N.; Gobbens, R.; De Donder, L.; Dury, S.; Buffel, T.; Schols, J.; Verté, D. The Comprehensive Frailty Assessment Instrument: Development, Validity and Reliability. Geriatr Nurs 2013, 34, 274–281, . [CrossRef]

- Gobbens, R.J.; Luijkx, K.G.; Wijnen-Sponselee, M.T.; Schols, J.M. Toward a Conceptual Definition of Frail Community Dwelling Older People. Nurs Outlook 2010, 58, 76–86, . [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. Hallmarks of Aging: An Expanding Universe. Cell 2023, 186, 243–278, . [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood, T.B.L. Understanding the Odd Science of Aging. Cell 2005, 120, 437–447, . [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci, L.; Gonzalez-Freire, M.; Fabbri, E.; Simonsick, E.; Tanaka, T.; Moore, Z.; Salimi, S.; Sierra, F.; de Cabo, R. Measuring Biological Aging in Humans: A Quest. Aging Cell 2020, 19, e13080, . [CrossRef]

- Brigola, A.G.; Rossetti, E.S.; Santos, B.R. dos; Neri, A.L.; Zazzetta, M.S.; Inouye, K.; Pavarini, S.C.I. Relationship between Cognition and Frailty in Elderly: A Systematic Review. Dement. neuropsychol. 2015, 9, 110–119, . [CrossRef]

- Grande, G.; Haaksma, M.L.; Rizzuto, D.; Melis, R.J.F.; Marengoni, A.; Onder, G.; Welmer, A.-K.; Fratiglioni, L.; Vetrano, D.L. Co-Occurrence of Cognitive Impairment and Physical Frailty, and Incidence of Dementia: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2019, 107, 96–103, . [CrossRef]

- Franz, C.E.; Buchholz, E.; Reynolds, C.A.; Hunt, J.F.V.; Schroeder, A.; Cortes, I.; Kremen, W.S. Frailty, Brain Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease Brain Signatures: Longitudinal Associations from Middle to Old Age. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2023, 19, e080643, . [CrossRef]

- McEwen, S.C.; Merrill, D.A.; Bramen, J.; Porter, V.; Panos, S.; Kaiser, S.; Hodes, J.; Ganapathi, A.; Bell, L.; Bookheimer, T.; et al. A Systems-Biology Clinical Trial of a Personalized Multimodal Lifestyle Intervention for Early Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2021, 7, e12191, . [CrossRef]

- Jessen, F.; Amariglio, R.E.; van Boxtel, M.; Breteler, M.; Ceccaldi, M.; Chételat, G.; Dubois, B.; Dufouil, C.; Ellis, K.A.; van der Flier, W.M.; et al. A Conceptual Framework for Research on Subjective Cognitive Decline in Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Dement 2014, 10, 844–852, . [CrossRef]

- Petersen, R.C.; Doody, R.; Kurz, A.; Mohs, R.C.; Morris, J.C.; Rabins, P.V.; Ritchie, K.; Rossor, M.; Thal, L.; Winblad, B. Current Concepts in Mild Cognitive Impairment. Archives of Neurology 2001, 58, 1985–1992, . [CrossRef]

- Petersen, R.C.; Caracciolo, B.; Brayne, C.; Gauthier, S.; Jelic, V.; Fratiglioni, L. Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Concept in Evolution. J Intern Med 2014, 275, 214–228, . [CrossRef]

- McKhann, G.M.; Knopman, D.S.; Chertkow, H.; Hyman, B.T.; Jack Jr., C.R.; Kawas, C.H.; Klunk, W.E.; Koroshetz, W.J.; Manly, J.J.; Mayeux, R.; et al. The Diagnosis of Dementia Due to Alzheimer’s Disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association Workgroups on Diagnostic Guidelines for Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2011, 7, 263–269, . [CrossRef]

- Cella, D.; Riley, W.; Stone, A.; Rothrock, N.; Reeve, B.; Yount, S.; Amtmann, D.; Bode, R.; Buysse, D.; Choi, S.; et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Developed and Tested Its First Wave of Adult Self-Reported Health Outcome Item Banks: 2005-2008. J Clin Epidemiol 2010, 63, 1179–1194, . [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. J Health Soc Behav 1983, 24, 385–396.

- Hagströmer, M.; Oja, P.; Sjöström, M. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ): A Study of Concurrent and Construct Validity. Public Health Nutr 2006, 9, 755–762, . [CrossRef]

- Reuben, D.B.; Magasi, S.; McCreath, H.E.; Bohannon, R.W.; Wang, Y.-C.; Bubela, D.J.; Rymer, W.Z.; Beaumont, J.; Rine, R.M.; Lai, J.-S.; et al. Motor Assessment Using the NIH Toolbox. Neurology 2013, 80, S65-75, . [CrossRef]

- Guralnik, J.M.; Simonsick, E.M.; Ferrucci, L.; Glynn, R.J.; Berkman, L.F.; Blazer, D.G.; Scherr, P.A.; Wallace, R.B. A Short Physical Performance Battery Assessing Lower Extremity Function: Association with Self-Reported Disability and Prediction of Mortality and Nursing Home Admission. J Gerontol 1994, 49, M85-94, . [CrossRef]

- Podsiadlo, D.; Richardson, S. The Timed “Up & Go”: A Test of Basic Functional Mobility for Frail Elderly Persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1991, 39, 142–148, . [CrossRef]

- Shumway-Cook, A.; Brauer, S.; Woollacott, M. Predicting the Probability for Falls in Community-Dwelling Older Adults Using the Timed Up & Go Test. Phys Ther 2000, 80, 896–903.

- Jones, C.J.; Rikli, R.E.; Beam, W.C. A 30-s Chair-Stand Test as a Measure of Lower Body Strength in Community-Residing Older Adults. Res Q Exerc Sport 1999, 70, 113–119, . [CrossRef]

- Dite, W.; Temple, V.A. A Clinical Test of Stepping and Change of Direction to Identify Multiple Falling Older Adults. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2002, 83, 1566–1571, . [CrossRef]

- Salamone, L.M.; Fuerst, T.; Visser, M.; Kern, M.; Lang, T.; Dockrell, M.; Cauley, J.A.; Nevitt, M.; Tylavsky, F.; Lohman, T.G. Measurement of Fat Mass Using DEXA: A Validation Study in Elderly Adults. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2000, 89, 345–352, . [CrossRef]

- Visser, M.; Fuerst, T.; Lang, T.; Salamone, L.; Harris, T.B. Validity of Fan-Beam Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry for Measuring Fat-Free Mass and Leg Muscle Mass. Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study--Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry and Body Composition Working Group. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1999, 87, 1513–1520, . [CrossRef]

- Kyle, U.G.; Schutz, Y.; Dupertuis, Y.M.; Pichard, C. Body Composition Interpretation. Contributions of the Fat-Free Mass Index and the Body Fat Mass Index. Nutrition 2003, 19, 597–604, . [CrossRef]

- Dale, A.; Fischl, B.; Sereno, M.I. Cortical Surface-Based Analysis: I. Segmentation and Surface Reconstruction. NeuroImage 1999, 9, 179–194.

- Fischl, B.; Dale, A.M. Measuring the Thickness of the Human Cerebral Cortex from Magnetic Resonance Images. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2000, 97, 11050–11055.

- Reuter, M.; Rosas, H.D.; Fischl, B. Highly Accurate Inverse Consistent Registration: A Robust Approach. NeuroImage 2010, 53, 1181–1196, . [CrossRef]

- Segonne, F.; Dale, A.M.; Busa, E.; Glessner, M.; Salat, D.; Hahn, H.K.; Fischl, B. A Hybrid Approach to the Skull Stripping Problem in MRI. NeuroImage 2004, 22, 1060–1075, . [CrossRef]

- Fischl, B.; Salat, D.H.; Busa, E.; Albert, M.; Dieterich, M.; Haselgrove, C.; van der Kouwe, A.; Killiany, R.; Kennedy, D.; Klaveness, S.; et al. Whole Brain Segmentation: Automated Labeling of Neuroanatomical Structures in the Human Brain. Neuron 2002, 33, 341–355.

- Fischl, B.; van der Kouwe, A.; Destrieux, C.; Halgren, E.; Ségonne, F.; Salat, D.H.; Busa, E.; Seidman, L.J.; Goldstein, J.; Kennedy, D.; et al. Automatically Parcellating the Human Cerebral Cortex. Cerebral Cortex 2004, 14, 11–22, . [CrossRef]

- Sled, J.G.; Zijdenbos, A.P.; Evans, A.C. A Nonparametric Method for Automatic Correction of Intensity Nonuniformity in MRI Data. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 1998, 17, 87–97.

- Fischl, B.; Liu, A.; Dale, A.M. Automated Manifold Surgery: Constructing Geometrically Accurate and Topologically Correct Models of the Human Cerebral Cortex. IEEE Medical Imaging 2001, 20, 70–80.

- Segonne, F.; Pacheco, J.; Fischl, B. Geometrically Accurate Topology-Correction of Cortical Surfaces Using Nonseparating Loops. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2007, 26, 518–529.

- Dale, A.M.; Sereno, M.I. Improved Localization of Cortical Activity by Combining EEG and MEG with MRI Cortical Surface Reconstruction: A Linear Approach. J Cogn Neurosci 1993, 5, 162–176, . [CrossRef]

- Whitwell, J.L.; Crum, W.R.; Watt, H.C.; Fox, N.C. Normalization of Cerebral Volumes by Use of Intracranial Volume: Implications for Longitudinal Quantitative MR Imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2001, 22, 1483–1489.

- Guadagnoli, E.; Velicer, W.F. Relation of Sample Size to the Stability of Component Patterns. Psychological Bulletin 1988, 103, 265–275, . [CrossRef]

- de Winter*, J.C.F.; Dodou*, D.; Wieringa, P.A. Exploratory Factor Analysis With Small Sample Sizes. Multivariate Behavioral Research 2009, 44, 147–181, . [CrossRef]

- Burns, J.M.; Johnson, D.K.; Watts, A.; Swerdlow, R.H.; Brooks, W.M. Reduced Lean Mass in Early Alzheimer Disease and Its Association with Brain Atrophy. Arch Neurol 2010, 67, 428–433, . [CrossRef]

- Carson, R.G. Get a Grip: Individual Variations in Grip Strength Are a Marker of Brain Health. Neurobiol Aging 2018, 71, 189–222, . [CrossRef]

- Firth, J.A.; Smith, L.; Sarris, J.; Vancampfort, D.; Schuch, F.; Carvalho, A.F.; Solmi, M.; Yung, A.R.; Stubbs, B.; Firth, J. Handgrip Strength Is Associated With Hippocampal Volume and White Matter Hyperintensities in Major Depression and Healthy Controls: A UK Biobank Study. Psychosom Med 2020, 82, 39–46, . [CrossRef]

- Meysami, S.; Raji, C.A.; Glatt, R.M.; Popa, E.S.; Ganapathi, A.S.; Bookheimer, T.; Slyapich, C.B.; Pierce, K.P.; Richards, C.J.; Lampa, M.G.; et al. Handgrip Strength Is Related to Hippocampal and Lobar Brain Volumes in a Cohort of Cognitively Impaired Older Adults with Confirmed Amyloid Burden. J Alzheimers Dis 2023, 91, 999–1006, . [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-X.; Tian, Y.; Wang, Z.-T.; Ma, Y.-H.; Tan, L.; Yu, J.-T. The Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s Disease Modifiable Risk Factors and Prevention. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 2021, 8, 313–321, . [CrossRef]

- Feter, N.; Penny, J.C.; Freitas, M.P.; Rombaldi, A.J. Effect of Physical Exercise on Hippocampal Volume in Adults: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Science & Sports 2018, 33, 327–338, . [CrossRef]

- Isaac, A.R.; Lima-Filho, R.A.S.; Lourenco, M.V. How Does the Skeletal Muscle Communicate with the Brain in Health and Disease? Neuropharmacology 2021, 197, 108744, . [CrossRef]

- Lam, N.T.; Gartz, M.; Thomas, L.; Haberman, M.; Strande, J.L. Influence of microRNAs and Exosomes in Muscle Health and Diseases. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 2020, 41, 269–284, . [CrossRef]

- El Hayek, L.; Khalifeh, M.; Zibara, V.; Abi Assaad, R.; Emmanuel, N.; Karnib, N.; El-Ghandour, R.; Nasrallah, P.; Bilen, M.; Ibrahim, P.; et al. Lactate Mediates the Effects of Exercise on Learning and Memory through SIRT1-Dependent Activation of Hippocampal Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF). J Neurosci 2019, 39, 2369–2382, . [CrossRef]

- Safdar, A.; Saleem, A.; Tarnopolsky, M.A. The Potential of Endurance Exercise-Derived Exosomes to Treat Metabolic Diseases. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2016, 12, 504–517, . [CrossRef]

- Matthews, V.B.; Aström, M.-B.; Chan, M.H.S.; Bruce, C.R.; Krabbe, K.S.; Prelovsek, O.; Akerström, T.; Yfanti, C.; Broholm, C.; Mortensen, O.H.; et al. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Is Produced by Skeletal Muscle Cells in Response to Contraction and Enhances Fat Oxidation via Activation of AMP-Activated Protein Kinase. Diabetologia 2009, 52, 1409–1418, . [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, B.K.; Febbraio, M.A. Muscles, Exercise and Obesity: Skeletal Muscle as a Secretory Organ. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2012, 8, 457–465, . [CrossRef]

- Wrann, C.D.; White, J.P.; Salogiannnis, J.; Laznik-Bogoslavski, D.; Wu, J.; Ma, D.; Lin, J.D.; Greenberg, M.E.; Spiegelman, B.M. Exercise Induces Hippocampal BDNF through a PGC-1α/FNDC5 Pathway. Cell Metab 2013, 18, 649–659, . [CrossRef]

- Di Liegro, C.M.; Schiera, G.; Proia, P.; Di Liegro, I. Physical Activity and Brain Health. Genes (Basel) 2019, 10, 720, . [CrossRef]

- Di Liegro, C.M.; Schiera, G.; Proia, P.; Di Liegro, I. Physical Activity and Brain Health. Genes (Basel) 2019, 10, 720, . [CrossRef]

- Delezie, J.; Handschin, C. Endocrine Crosstalk Between Skeletal Muscle and the Brain. Front Neurol 2018, 9, 698, . [CrossRef]

- de Aquino, M.P.M.; de Oliveira Cirino, N.T.; Lima, C.A.; de Miranda Ventura, M.; Hill, K.; Perracini, M.R. The Four Square Step Test Is a Useful Mobility Tool for Discriminating Older Persons with Frailty Syndrome. Experimental Gerontology 2022, 161, 111699, . [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.-F.; Yang, H.-J.; Peng, Y.-C.; Chen, H.-Y. Motor Dual-Task Timed Up & Go Test Better Identifies Prefrailty Individuals than Single-Task Timed Up & Go Test. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2015, 15, 204–210, . [CrossRef]

- Woollacott, M.; Shumway-Cook, A. Attention and the Control of Posture and Gait: A Review of an Emerging Area of Research. Gait & Posture 2002, 16, 1–14, . [CrossRef]

- Lacour, M.; Bernard-Demanze, L.; Dumitrescu, M. Posture Control, Aging, and Attention Resources: Models and Posture-Analysis Methods. Neurophysiologie Clinique/Clinical Neurophysiology 2008, 38, 411–421, . [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Chastan, N.; Bair, W.-N.; Resnick, S.M.; Ferrucci, L.; Studenski, S.A. The Brain Map of Gait Variability in Aging, Cognitive Impairment and Dementia-A Systematic Review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2017, 74, 149–162, . [CrossRef]

- Beauchet, O.; Annweiler, C.; Montero-Odasso, M.; Fantino, B.; Herrmann, F.R.; Allali, G. Gait Control: A Specific Subdomain of Executive Function? Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation 2012, 9, 12, . [CrossRef]

- McKee, K.E.; Hackney, M.E. The Four Square Step Test in Individuals with Parkinson’s Disease: Association with Executive Function and Comparison with Older Adults. NRE 2014, 35, 279–289, . [CrossRef]

- Amboni, M.; Barone, P.; Hausdorff, J.M. Cognitive Contributions to Gait and Falls: Evidence and Implications. Mov Disord 2013, 28, 1520–1533, . [CrossRef]

- Yogev, G.; Hausdorff, J.M.; Giladi, N. The Role of Executive Function and Attention in Gait. Mov Disord 2008, 23, 329–472, . [CrossRef]

- Doi, T.; Blumen, H.M.; Verghese, J.; Shimada, H.; Makizako, H.; Tsutsumimoto, K.; Hotta, R.; Nakakubo, S.; Suzuki, T. Gray Matter Volume and Dual-Task Gait Performance in Mild Cognitive Impairment. Brain Imaging Behav 2017, 11, 887–898, . [CrossRef]

- Hupfeld, K.E.; Geraghty, J.M.; McGregor, H.R.; Hass, C.J.; Pasternak, O.; Seidler, R.D. Differential Relationships Between Brain Structure and Dual Task Walking in Young and Older Adults. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 2022, 14.

- Parvin, E.; Mohammadian, F.; Amani-Shalamzari, S.; Bayati, M.; Tazesh, B. Dual-Task Training Affect Cognitive and Physical Performances and Brain Oscillation Ratio of Patients With Alzheimer’s Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 2020, 12.

- Kuo, H.-T.; Yeh, N.-C.; Yang, Y.-R.; Hsu, W.-C.; Liao, Y.-Y.; Wang, R.-Y. Effects of Different Dual Task Training on Dual Task Walking and Responding Brain Activation in Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 8490, . [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.-Y.; Huang, Y.-C.; Zhou, J.-H.; Cheng, S.-J.; Yang, Y.-R. Effects of Exergame-Based Dual-Task Training on Executive Function and Dual-Task Performance in Community-Dwelling Older People: A Randomized-Controlled Trial. Games for Health Journal 2021, 10, 347–354, . [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.-M.; Kim, S. Dual-Task Training Effect on Cognitive and Body Function, β-Amyloid Levels in Alzheimer’s Dementia Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Kor Phys Ther 2021, 33, 136–141, . [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.; Tian, H.; Thabane, L.; Ma, J.; Wu, H.; Zhong, Q.; Gao, Y.; Sun, C.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, T. The Effects of Dual-Task Training on Cognitive and Physical Functions in Older Adults with Cognitive Impairment; A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 2022, 9, 359–370, . [CrossRef]

- Insel, T.R.; Cuthbert, B.N. Medicine. Brain Disorders? Precisely. Science 2015, 348, 499–500, . [CrossRef]

- Cuthbert, B.N. Research Domain Criteria: Toward Future Psychiatric Nosologies. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2015, 17, 89–97, . [CrossRef]

- Elsman, E.B.M.; Roorda, L.D.; Smidt, N.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Terwee, C.B. Measurement Properties of the Dutch PROMIS-29 v2.1 Profile in People with and without Chronic Conditions. Qual Life Res 2022, 31, 3447–3458, . [CrossRef]

- Hays, R.D.; Spritzer, K.L.; Schalet, B.D.; Cella, D. PROMIS®-29 v2.0 Profile Physical and Mental Health Summary Scores. Qual Life Res 2018, 27, 1885–1891, . [CrossRef]

- Szu-Ting Fu, T.; Koutstaal, W.; Poon, L.; Cleare, A.J. Confidence Judgment in Depression and Dysphoria: The Depressive Realism vs. Negativity Hypotheses. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 2012, 43, 699–704, . [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, M.E.; Freiheit, E.A.; Faris, P.; Hogan, D.B.; Patten, S.B.; Anderson, T.; Ghali, W.A.; Knudtson, M.; Demchuk, A.; Maxwell, C.J. Depressive Symptoms and Functional Decline Following Coronary Interventions in Older Patients with Coronary Artery Disease: A Prospective Cohort Study. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 277, . [CrossRef]

- Ormel, J.; Rijsdijk, F.V.; Sullivan, M.; van Sonderen, E.; Kempen, G.I.J.M. Temporal and Reciprocal Relationship between IADL/ADL Disability and Depressive Symptoms in Late Life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2002, 57, P338-347, . [CrossRef]

- Russo, S.J.; Nestler, E.J. The Brain Reward Circuitry in Mood Disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci 2013, 14, 609–625, . [CrossRef]

- Price, J.L.; Drevets, W.C. Neural Circuits Underlying the Pathophysiology of Mood Disorders. Trends Cogn Sci 2012, 16, 61–71, . [CrossRef]

- Price, J.L.; Drevets, W.C. Neurocircuitry of Mood Disorders. Neuropsychopharmacol 2010, 35, 192–216, . [CrossRef]

- Kales, H.C.; Gitlin, L.N.; Lyketsos, C.G. Management of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms of Dementia in Clinical Settings: Recommendations from a Multidisciplinary Expert Panel. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014, 62, 762–769, . [CrossRef]

- Ruthirakuhan, M.; Ismail, Z.; Herrmann, N.; Gallagher, D.; Lanctôt, K.L. Mild Behavioral Impairment Is Associated with Progression to Alzheimer’s Disease: A Clinicopathological Study. Alzheimers Dement 2022, 18, 2199–2208, . [CrossRef]

- Ismail, Z.; Smith, E.E.; Geda, Y.; Sultzer, D.; Brodaty, H.; Smith, G.; Agüera-Ortiz, L.; Sweet, R.; Miller, D.; Lyketsos, C.G. Neuropsychiatric Symptoms as Early Manifestations of Emergent Dementia: Provisional Diagnostic Criteria for Mild Behavioral Impairment. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2016, 12, 195–202, . [CrossRef]

- Devanand, D.P.; Lee, S.; Huey, E.D.; Goldberg, T.E. Associations Between Neuropsychiatric Symptoms and Neuropathological Diagnoses of Alzheimer Disease and Related Dementias. JAMA Psychiatry 2022, 79, 359–367, . [CrossRef]

- Gibson, L.L.; Grinberg, L.T.; ffytche, D.; Leite, R.E.P.; Rodriguez, R.D.; Ferretti-Rebustini, R.E.L.; Pasqualucci, C.A.; Nitrini, R.; Jacob-Filho, W.; Aarsland, D.; et al. Neuropathological Correlates of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Dementia. Alzheimers Dement 2023, 19, 1372–1382, . [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Yoon, K.S. Stress: Metaplastic Effects in the Hippocampus. Trends Neurosci 1998, 21, 505–509, . [CrossRef]

- Conrad, C.D. Chronic Stress-Induced Hippocampal Vulnerability: The Glucocorticoid Vulnerability Hypothesis. Rev Neurosci 2008, 19, 395–411, . [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.A.O.; Bezerra, L.S.; Carvalho, A.R.M.R.; Brainer-Lima, A.M. Global Hippocampal Atrophy in Major Depressive Disorder: A Meta-Analysis of Magnetic Resonance Imaging Studies. Trends Psychiatry Psychother 2018, 40, 369–378, . [CrossRef]

- McKinnon, M.C.; Yucel, K.; Nazarov, A.; MacQueen, G.M. A Meta-Analysis Examining Clinical Predictors of Hippocampal Volume in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience 2009, 34, 41–54.

- Geerlings, M.I.; Gerritsen, L. Late-Life Depression, Hippocampal Volumes, and Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Regulation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biological Psychiatry 2017, 82, 339–350, . [CrossRef]

- Cha, J.; Greenberg, T.; Song, I.; Blair Simpson, H.; Posner, J.; Mujica-Parodi, L.R. Abnormal Hippocampal Structure and Function in Clinical Anxiety and Comorbid Depression. Hippocampus 2016, 26, 545–553, . [CrossRef]

- Videbech, P.; Ravnkilde, B. Hippocampal Volume and Depression: A Meta-Analysis of MRI Studies. AJP 2004, 161, 1957–1966, . [CrossRef]

- Gorbach, T.; Pudas, S.; Lundquist, A.; Orädd, G.; Josefsson, M.; Salami, A.; de Luna, X.; Nyberg, L. Longitudinal Association between Hippocampus Atrophy and Episodic-Memory Decline. Neurobiology of Aging 2017, 51, 167–176, . [CrossRef]

- Fjell, A.M.; Walhovd, K.B.; Amlien, I.; Bjørnerud, A.; Reinvang, I.; Gjerstad, L.; Cappelen, T.; Willoch, F.; Due-Tønnessen, P.; Grambaite, R.; et al. Morphometric Changes in the Episodic Memory Network and Tau Pathologic Features Correlate with Memory Performance in Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment. American Journal of Neuroradiology 2008, 29, 1183–1189, . [CrossRef]

- Sexton, C.E.; Mackay, C.E.; Lonie, J.A.; Bastin, M.E.; Terrière, E.; O’Carroll, R.E.; Ebmeier, K.P. MRI Correlates of Episodic Memory in Alzheimer’s Disease, Mild Cognitive Impairment, and Healthy Aging. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging 2010, 184, 57–62, . [CrossRef]

- James, T.A.; Weiss-Cowie, S.; Hopton, Z.; Verhaeghen, P.; Dotson, V.M.; Duarte, A. Depression and Episodic Memory across the Adult Lifespan: A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychol Bull 2021, 147, 1184–1214, . [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Rolls, E.T.; Cheng, W.; Kang, J.; Dong, G.; Xie, C.; Zhao, X.-M.; Sahakian, B.J.; Feng, J. Associations of Social Isolation and Loneliness With Later Dementia. Neurology 2022, 99, e164–e175, . [CrossRef]

- van Kooten, J.; Smalbrugge, M.; van der Wouden, J.C.; Stek, M.L.; Hertogh, C.M.P.M. Prevalence of Pain in Nursing Home Residents: The Role of Dementia Stage and Dementia Subtypes. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017, 18, 522–527, . [CrossRef]

- Powell, V.D.; Abedini, N.C.; Galecki, A.T.; Kabeto, M.; Kumar, N.; Silveira, M.J. Unwelcome Companions: Loneliness Associates with the Cluster of Pain, Fatigue, and Depression in Older Adults. Gerontol Geriatr Med 2021, 7, 2333721421997620, . [CrossRef]

- Angioni, D.; Raffin, J.; Ousset, P.-J.; Delrieu, J.; de Souto Barreto, P. Fatigue in Alzheimer’s Disease: Biological Basis and Clinical Management-a Narrative Review. Aging Clin Exp Res 2023, 35, 1981–1989, . [CrossRef]

- Bannon, S.; Greenberg, J.; Mace, R.A.; Locascio, J.J.; Vranceanu, A.-M. The Role of Social Isolation in Physical and Emotional Outcomes among Patients with Chronic Pain. General Hospital Psychiatry 2021, 69, 50–54, . [CrossRef]

- Stijovic, A.; Forbes, P.A.G.; Tomova, L.; Skoluda, N.; Feneberg, A.C.; Piperno, G.; Pronizius, E.; Nater, U.M.; Lamm, C.; Silani, G. Homeostatic Regulation of Energetic Arousal During Acute Social Isolation: Evidence From the Lab and the Field. Psychol Sci 2023, 34, 537–551, . [CrossRef]

- 2024 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimers Dement 2024, 20, 3708–3821, . [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Raecke, R.; Niemeier, A.; Ihle, K.; Ruether, W.; May, A. Structural Brain Changes in Chronic Pain Reflect Probably Neither Damage nor Atrophy. PLoS One 2013, 8, e54475, . [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Almeida, Y.; Fillingim, R.B.; Riley, J.L.; Woods, A.J.; Porges, E.; Cohen, R.; Cole, J. Chronic Pain Is Associated with a Brain Aging Biomarker in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Pain 2019, 160, 1119–1130, . [CrossRef]

- Apkarian, A.V.; Sosa, Y.; Sonty, S.; Levy, R.M.; Harden, R.N.; Parrish, T.B.; Gitelman, D.R. Chronic Back Pain Is Associated with Decreased Prefrontal and Thalamic Gray Matter Density. J Neurosci 2004, 24, 10410–10415, . [CrossRef]

- Neumann, N.; Domin, M.; Schmidt, C.-O.; Lotze, M. Chronic Pain Is Associated with Less Grey Matter Volume in the Anterior Cingulum, Anterior and Posterior Insula and Hippocampus across Three Different Chronic Pain Conditions. European Journal of Pain 2023, 27, 1239–1248, . [CrossRef]

- Putra, H.A.; Park, K.; Yamashita, F.; Mizuno, K.; Watanabe, Y. Regional Gray Matter Volume Correlates to Physical and Mental Fatigue in Healthy Middle-Aged Adults. Neuroimage: Reports 2022, 2, 100128, . [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Rolls, E.T.; Cheng, W.; Kang, J.; Dong, G.; Xie, C.; Zhao, X.-M.; Sahakian, B.J.; Feng, J. Associations of Social Isolation and Loneliness With Later Dementia. Neurology 2022, 99, e164–e175, . [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Value |

| Age (years) | 71.8 ± 7.2 |

| Biological Sex (F/M) | (24/24) |

| Years of Education | 16.8 ± 2.6 |

| Race | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (2.1%) |

| Asian | 5 (10.4%) |

| Black or African American | 1 (2.1%) |

| White | 40 (83.3%) |

| Other | 1 (2.1%) |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic) | 2 (4.2%) |

| Handedness (Right/Left/Ambidextrous) | (42/4/2) |

| APOE-ε4 carriers, n (%)# | 35 (73.9%) |

| MoCA (total score, 0-30) | 21.4 ± 3.8 |

| Memory Test Scores | |

| Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (words recalled) | 14.5 ± 6.2 |

| WMS-IV Verbal Paired Associates I (scaled score) | 6.5 ± 3.3 |

| WMS-IV Verbal Paired Associates II (total scaled score) | 7.4 ± 3.8 |

| WMS-IV Verbal Paired Associates II (scaled score) | 6.6 ± 3.6 |

| WMS-IV Verbal Paired Associates I (scaled score) | 5.7 ± 3.6 |

| Executive Functioning Test Scores | |

| Trail Making Test – Part B (seconds) | 138 ± 64 |

| NIH Toolbox Oral Symbol Digit Test (correct responses) | 45.4 ± 18.4 |

| Imaging Measures$ | |

| Total Gray Matter Volume (mm³) | 551943 ± 69353 |

| Hippocampal Volume (mm³) | 6263 ± 1083 |

| Outcome | Model Statistics* | Predictor | β (95%CI); r (p-value) |

| Memory z-score | F(5, 41) = 2.98, p = 0.02; adj R2 = 0.27 | Psychosocial Factor 1 (Psychological Distress) | -0.35 (-0.64, -0.07); -0.36 (0.02) |

| Executive functioning z-score | F(5, 41) = 2.78, p = 0.03; adj R2 = 0.28 | Functional Factor 3 (Dual-task Performance) |

-0.55 (-0.89, -0.21); -0.48 (0.002) |

| Total Gray Matter Volume (mm³) | F(7, 37) = 19.09, p < 0.0001; adj R2 = 0.81 | Functional Factor 3 (Dual-task Performance) |

-15676.8 (-28142.1,-3211.4); -0.42 (0.01) |

| Psychosocial Factor 2 (Physical & Social Limitations) |

-8619.3 (-19106.2,-1867.5); -0.33 (0.05) | ||

| Hippocampal Volume (mm³) | F(7, 37) = 14.54, p < 0.0001; adj R2 = 0.73 | Physical Factor 1 (Lean Mass) |

781.5 (371.8, 1191.2); 0.54 (0.0004) |

| Psychosocial Factor 1 (Psychological Distress) |

-206.2 (-408.6, -3.8); -0.32 (0.05) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).