Submitted:

01 September 2025

Posted:

03 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Sampling Strategy

2.2. Data Collection Procedure

2.3. Measures

- Ethical Leadership: Measured with the 10-item unidimensional scale by Brown et al. (2005). Cronbach’s alpha in this study: 0.92.

- Principle-Based Ethical Climate: Assessed with the 11-item scale developed by Victor and Cullen (1988), comprising three dimensions: personal morality, rules and procedures, and professional codes and laws. Cronbach’s alpha: 0.74.

- Affective Commitment: Measured with the Meyer and Allen (1993). Cronbach’s alpha: 0.86.

- Burnout: Evaluated using the Maslach Burnout Inventory–General Survey (Schaufeli et al., 1996). Emotional exhaustion (5 items, α = 0.90) and depersonalization (5 items; α = 0.90; item 13 removed due to low factor loading).

- Telework Intensity: Operationalized as the self-reported number of telework days per week (1–5), following Vander Elst et al. (2017) and Virick et al. (2010).

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Analytical Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Ethical Leadership and Affective Commitment

3.2. Affective Commitment and Emotional Exhaustion

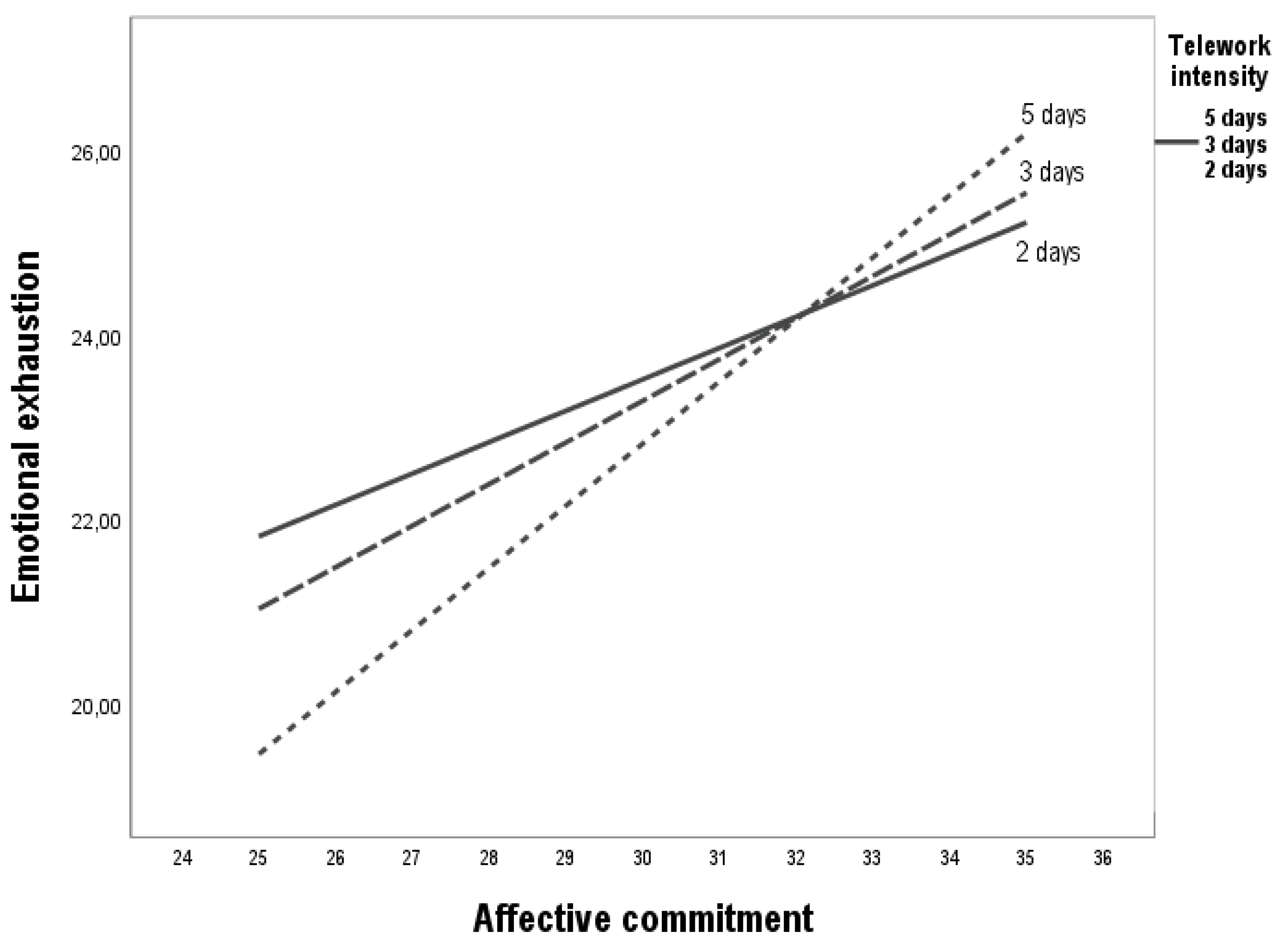

3.3. Ethical Climate and Emotional Exhaustion

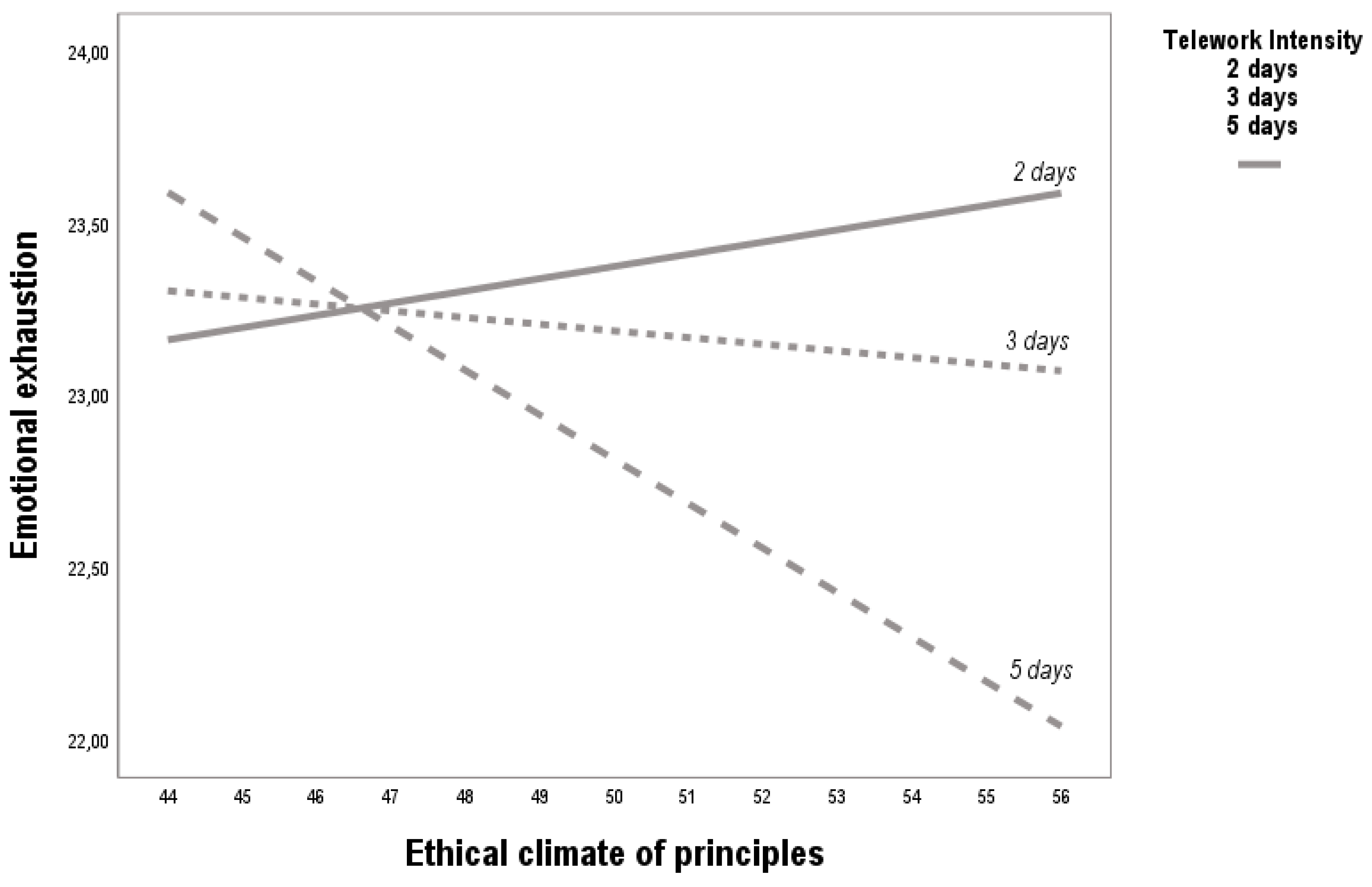

3.4. Ethical Climate and Depersonalization

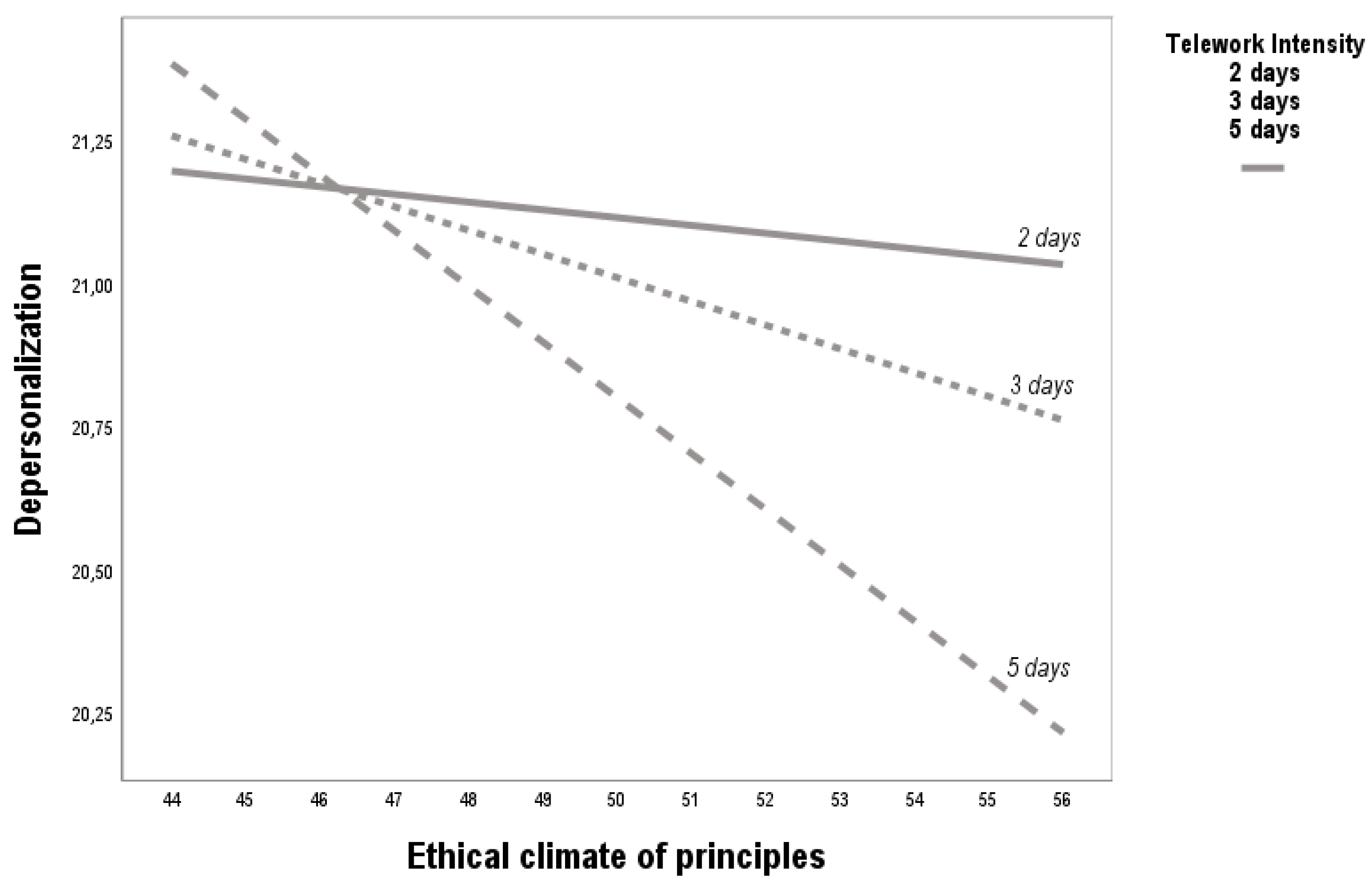

3.5. Synthesis of Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Practical Implications

4.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Asif, Qing, Hwang, & Shi. (2019). Ethical Leadership, Affective Commitment, Work Engagement, and Creativity: Testing a Multiple Mediation Approach. Sustainability, 11(16), 4489. [CrossRef]

- Atabay, G., Çangarli, B. G., & Penbek, Ş. (2015). Impact of ethical climate on moral distress revisited: multidimensional view. Nursing ethics, 22(1), 103-116. [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, I., Rossi, M. F., Melcore, G., Perrotta, A., Santoro, P. E., Gualano, M. R., & Moscato, U. (2023). Workplace ethical climate and workers’ burnout: A systematic review. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 20(5), 405-414. [CrossRef]

- Bouraoui, K., Bensemmane, S., Ohana, M., & Russo, M. (2019a). Corporate social responsibility and employees’ affective commitment. Management Decision, 57(1), 152–167. [CrossRef]

- Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 595–616. [CrossRef]

- Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 117–134. [CrossRef]

- Chung, H., & van der Lippe, T. (2020). Flexible working, work–life balance, and gender equality: Introduction. Social Indicators Research, 151(2), 365–381. [CrossRef]

- Cook, K. S., Cheshire, C., Rice, E. R., & Nakagawa, S. (2013). Social exchange theory. In Handbook of social psychology (pp. 61-88). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication monographs, 85(1), 4-40. [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, A., Sengupta, S., Panda, M., Hati, L., Prikshat, V., Patel, P., & Mohyuddin, S. (2024). Teleworking: role of psychological well-being and technostress in the relationship between trust in management and employee performance. International Journal of Manpower, 45(1), 49–71. [CrossRef]

- Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., Simon, L. S., & Judge, T. A. (2016). A Head Start or a Step Behind? Understanding How Dispositional and Motivational Resources Influence Emotional Exhaustion. Journal of Management, 42(3), 561–581. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., So, K. K. F., & Wirtz, J. (2022). Service robots: Applying social exchange theory to better understand human–robot interactions. Tourism Management, 92(1), 104537. [CrossRef]

- Kniffin, K. M., Narayanan, J., Anseel, F., Antonakis, J., Ashford, S. P., Bakker, A. B., Bamberger, P., Bapuji, H., Bhave, D. P., Choi, V. K., Creary, S. J., Demerouti, E., Flynn, F. J., Gelfand, M. J., Greer, L. L., Johns, G., Kesebir, S., Klein, P. G., Lee, S. Y., ... Vugt, M. V. (2021). COVID-19 and the workplace: Implications, issues, and insights for future research and action. American Psychologist, 76(1), 63–77. [CrossRef]

- Lazauskaitė-Zabielskė, J., Urbanavičiūtė, I., & Žiedelis, A. (2023). Pressed to overwork to exhaustion? The role of psychological detachment and exhaustion in the context of teleworking. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 44(3), 875–892. [CrossRef]

- Lazauskaite-Zabielske, J., Ziedelis, A., & Urbanaviciute, I. (2022). When working from home might come at a cost: the relationship between family boundary permeability, overwork climate and exhaustion. Baltic Journal of Management, 17(5), 705–721. [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397–422. [CrossRef]

- Mercurio, Z. A. (2015). Affective Commitment as a Core Essence of Organizational Commitment. Human Resource Development Review, 14(4), 389–414. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1(1), 61–89. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., & Smith, C. A. (1993). Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(4), 538–551. [CrossRef]

- Molino, M., Ingusci, E., Signore, F., Manuti, A., Giancaspro, M. L., Russo, V., Zito, M., & Cortese, C. G. (2020). Wellbeing costs of technology use during remote working: An investigation using the Italian translation of the technostress creators scale. Sustainability, 12(15), 5911. [CrossRef]

- Neubert, M. J., Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. M., Roberts, J. A., & Chonko, L. B. (2009). The virtuous influence of ethical leadership behavior: Evidence from the field. Journal of Business Ethics, 90(2), 157–170. [CrossRef]

- Park, J. G., Zhu, W., Kwon, B., & Bang, H. (2023). Ethical leadership and follower unethical pro-organizational behavior: examining the dual influence mechanisms of affective and continuance commitments. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 34(22), 4313–4343. [CrossRef]

- Rivaz, M., Asadi, F., & Mansouri, P. (2020). Assessment of the Relationship between Nurses’ Perception of Ethical Climate and Job Burnout in Intensive Care Units. Investigación y Educación En Enfermería, 38(3), e12. [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, C. W., Allan, B., Clark, M., Hertel, G., Hirschi, A., Kunze, F., Shockley, K., Shoss, M., Sonnentag, S., & Zacher, H. (2021). Pandemics: Implications for research and practice in industrial and organizational psychology. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 14(1-2), 1–35. [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. (2023). Teleworking and emotional exhaustion in the Colombian electricity sector: The mediating role of affective commitment and the moderating role of creativity. Intangible Capital, 19(2), 207-258. [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. (2025). ¿El liderazgo y los climas éticos amortiguan o promueven el burnout en el Sector Eléctrico Colombiano? [Tesis doctoral, Universitat de Girona]. TDX (Tesis Doctorals en Xarxa). https://www.tdx.cat/handle/10803/694925.

- Santiago-Torner, C., Corral-Marfil, J. A., Jiménez-Pérez, Y., & Tarrats-Pons, E. (2025a). Impact of ethical leadership on autonomy and self-efficacy in virtual work environments: The disintegrating effect of an egoistic climate. Behavioral Sciences, 15(1), 95. [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C., Corral-Marfil, J.-A., & Tarrats-Pons, E. (2024). Relationship between Personal Ethics and Burnout: The Unexpected Influence of Affective Commitment. Administrative Sciences, 14(6), 123. [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C., González-Carrasco, M., & Miranda-Ayala, R. (2025b). Relationship between ethical climate and burnout: A new approach through work autonomy. Behavioral Sciences, 15(2), 121. [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1996). Maslach Burnout Inventory–General Survey. In C. Maslach, S. E. Jackson, & M. P. Leiter (Eds.), MBI manual (3rd ed.). Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Schaufeli, W., & Salanova, M. (2011). Work engagement: On how to better catch a slippery concept. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 20(1), 39–46. [CrossRef]

- Stankevičienė, A., Grincevičienė, N., Diskienė, D., & Drūteikienė, G. (2024). The Influence of personal skills for telework on organisational commitment: The mediating effect of the perceived intensity of telework. JEEMS Journal of East European Management Studies, 28(4), 606-629. [CrossRef]

- Teresi, M., Pietroni, D., Barattucci, M., Giannella, V. A., & Pagliaro, S. (2019). Ethical climate(s), organizational identification, and employees’ behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(1), 1356. [CrossRef]

- Vander Elst, T., Verhoogen, R., Sercu, M., Van den Broeck, A., Baillien, E., & Godderis, L. (2017). Not extent of telecommuting, but job characteristics as proximal predictors of work-related well-being. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 59(10), e180–e186. [CrossRef]

- Victor, B., & Cullen, J. B. (1988). The organizational bases of ethical work climates. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33(1), 101–125. [CrossRef]

- Virick, M., DaSilva, N., & Arrington, K. (2010). Moderators of the curvilinear relation between extent of telecommuting and job and life satisfaction: The role of performance outcome orientation and worker type. Human Relations, 63(1), 137–154. [CrossRef]

| Model Summary | R | R² | ΔR² | F (df1, df2) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variable: | Affective commitment (Y) | ||||

| Overall model | 0.29 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 14.01 (3. 443) | < 0.01 |

| Predictor | b | SE | t | p | 95% CI [LLCI, ULCI] |

| Constant | 22.50 | 3.17 | 7.01 | 0.01 | [16.27, 28.74] |

| Ethical Leadership (X) | 0.25 | 0.06 | 3.42 | 0.01 | [0.11, 0.39] |

| Telework Intensity (W) | −0.59 | 1.01 | −0.56 | 0.57 | [−1.60, 3.21] |

| Interaction (X × W) | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.43 | 0.67 | [−0.07, 0.05] |

| Model Summary | R | R² | ΔR² | F (df1, df2) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variable: | Emotional Exhaustion (Y) | ||||

| Overall model | 0.46 | 0.21 | 0.08 | 39.09 (3. 444) | < 0.01 |

| Predictor | b | SE | t | p | 95% CI [LLCI, ULCI] |

| Constant | 15.46 | 3.65 | 4.23 | 0.01 | [8.29, 22.64] |

| Affective Commitment (X) | 0.27 | 0.12 | 2.25 | 0.02 | [0.04, 0.51] |

| Telework Intensity (W) | −2.49 | 1.08 | −2.29 | 0.02 | [−4.62, −0.35] |

| Interaction (X × W) | 0.08 | 0.04 | 2.14 | 0.03 | [0.06, 0.15] |

| Model Summary | R | R² | ΔR² | F (df1, df2) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variable: | Emotional Exhaustion (Y) | ||||

| Overall model | 0.46 | 0.22 | 0.09 | 24.58 (5. 442) | < 0.01 |

| Predictor | b | SE | t | p | 95% CI [LLCI, ULCI] |

| Constant | 24.53 | 4.30 | 4.13 | 0.01 | [4.32, 23.69] |

| Climate of principles (X) | 0.20 | 0.07 | 3.42 | 0.01 | [0.11, 0.39] |

| Telework Intensity (W) | −2.72 | 1.46 | −3.66 | 0.02 | [−1.60, −0.21] |

| Interaction (X × W) | −0.06 | 0.03 | −3.95 | 0.02 | [−0.11, −0.02] |

| Model Summary | R | R² | ΔR² | F (df1, df2) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variable: | Depersonalization (Y) | ||||

| Overall model | 0.58 | 0.34 | 0.12 | 35.79 (5. 442) | < 0.01 |

| Predictor | b | SE | t | p | 95% CI [LLCI, ULCI] |

| Constant | 24.41 | 4.17 | 4.28 | 0.01 | [4.10, 23.01] |

| Climate of principles (X) | 0.26 | 0.07 | 4.32 | 0.01 | [0.21, 0.79] |

| Telework Intensity (W) | −2.12 | 1.66 | −3.26 | 0.02 | [−1.16, −0.31] |

| Interaction (X × W) | −0.05 | 0.02 | −3.25 | 0.02 | [−0.42, −0.12] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).