1. Introduction

Reliable and timely information in medicine depends on several key factors: trained users; healthcare professionals who accurately collect data from patients; quality control; and error-free transmission of information across the various software systems used in healthcare institutions—such as electronic health records, laboratory information management systems, pharmacy systems, and other similar systems. These elements together generate reliable databases that enable systematic analysis and diagnosis of epidemiology, production, risk stratification, resource utilization, and opportunities for improvement within healthcare systems.

We must not forget that, to obtain accurate results, trained and qualified users who understand the importance of their performance are essential. In this analysis, we will focus on the laboratory [

1].

Microbiology laboratories have a series of characteristics that have delayed the automation of processes, unlike the fields of hematology or biochemistry [

2,

3,

4]. Ten years ago, the differentiating value proposition of the microbiology laboratory was focused on turnaround time (TAT), and efforts were directed toward optimizing human workflows to improve response times [

5]. Although the first automated systems in microbiology have been in operation for over 30 years, the widespread adoption of automation was significantly delayed, particularly in Latin America. Over the past two decade, and especially since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, microbiology laboratories have increasingly embraced new technologies and processes that enhance quality and efficiency, along with reducing TAT.

Antonios et al. published an article indicating that microbiology laboratory automation can improve standardization, increase laboratory efficiency, enhance workplace safety, and reduce long-term costs. [

4].

However, no technological tool can improve the laboratory workflow without a prior evaluation of the sample processing stream by the technicians and professionals working in the laboratory. Laboratory process automation enhances efficiency by eliminating tasks, reducing redundant steps, removing low-utility techniques from routine workflows, or outsourcing specific processes. An example of this is discussed by

Tregueiros et al., who demonstrated that automated incubators with digital image capture significantly reduce the number of manipulations of culture media plates, and that approximately 97% of samples are suitable for automated processing [

2]. Employees often resist change; it is part of human nature [

6]. Various factors can contribute to this resistance, including workload overload, lack of training provided by healthcare institutions, communication issues with supervisors or hospital management, among others [

2,

6]. Therefore, it is necessary to develop tools and training opportunities, as well as to assess laboratory workflow, to improve laboratory outcomes [

2]. This is what is currently referred to as change management [

2,

3]. To the best of our knowledge, no studies on change management in microbiology laboratories have been documented in Latin America. Nevertheless, there are well-established tools with robust scientific backing, among which the Kaizen methodology is widely recommended [

7].

Latin American microbiology laboratories face the challenge of balancing the high cost of supplies with the difficulty of accessing specialized human resources [

8,

9]. In this context, optimizing workflows to reduce turnaround time has a direct impact on both diagnosis and patient outcomes [

10,

11].

Several studies in Europe, the United States, and Asia have demonstrated that the incorporation of new technologies can be decisive. Tools such as point-of-care testing at the bedside (POC), immunochromatographic and molecular tests for COVID-19 diagnosis, as well as multiplex PCR platforms applied directly to bacterial agar cultures, significantly reduce turnaround times and support the initiation of appropriate antimicrobial therapy [

12,

13,

14]. Tseng

et al. showed that the use of multiplex molecular diagnostics in patients with sepsis had an impact on the early detection of antimicrobial resistance and reduced 28-day hospital mortality [

15].

This methodology has implications beyond the laboratory. Shorter turnaround times facilitate relevant clinical decision-making, such as timely adjustment of antimicrobial therapy, escalation or de-escalation of treatments, and other interventions. These aspects are critical in the management of intensive care units, oncology services, neonatology, and other clinical settings [

14,

16].

This methodology adopts an evidence-based approach to enhancing quality and efficiency, integrating tools from philosophy, process optimization, people management, and work structure design. The objective of this study was to evaluate the reduction in turnaround time for a reliable, digitized clinical result delivered to both patients and healthcare personnel, through the optimization of microbiology laboratory workflow from a change management perspective.

2. Materials and Methods

The microbiology laboratory at Hospital Roberto del Río (HRRIO), a public pediatric institution of the northern area of the Metropolitan Region of Santiago of Chile, has a capacity of 189 beds, 45 are designated for critically ill patients. The laboratory occupies 482 square meters, divided into six functional sections, and is staffed by 36 professionals and technicians working both standard daytime hours and in a 24/7 shift system. The facility operates within an infrastructure that is 86 years old.

The current workflow requires frequent movement and door openings to transfer clinical samples between areas. In response to guidance from the Laboratory Director to improve staff efficiency and reduce TAT, bioMérieux provided workflow consulting and support for better personnel allocation by Kaizen/lean strategy. The LD requested that the analysis be centralized around blood culture sample processing.

The month of July 2022 was designated as the baseline or pre-intervention period. During this month, a total of 961 blood cultures were processed using BACT/ALERT® 3D, in the diagnostic of positive samples VITEK® 2 Compact, MALDI-TOF Vitek® MS Legacy were used. As part of the baseline assessment, the existing workflow was evaluated, which included measuring the distance between the sample reception area and the diagnostic equipment, and the time of each stage of the process.

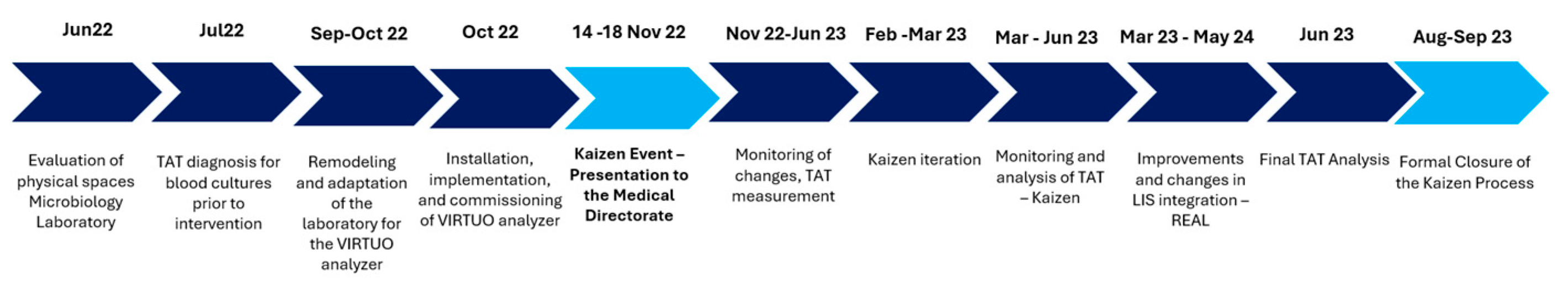

The Kaizen/LEAN intervention and the laboratory workflow optimization strategy for blood culture processing, incorporating a new system and an updated procedural model. A key component of the intervention involved the installation of the new Virtuo® blood culture system, following by the integration into routine practice. A detailed timeline for the intervention was developed in collaboration with the LD (

Figure 1).

This intervention involved the full engagement of both professional and technical microbiology laboratory staff in a five-day Kaizen immersion program, specifically adapted to the healthcare context. This was followed by an eight-month monitoring phase to refine the intervention. The focus was on identifying non–value-adding activities, eliminating redundancies, and redesigning the workflow to ensure a sustainable, efficient, and participatory model.

The replacement of the existing blood culture analyzer with a higher-capacity model, Virtuo® featuring continuous automated loading and enhanced time-to-detection performance, was considered from the outset, as its implementation is supported by published evidence demonstrating improved blood culture workflow efficiency [

8,

9].

The blood culture analyzer was relocated near the laboratory's sample reception area (admission area) in September. Subsequently, the implementation, staff training, and commissioning of the new technology took place in October.

Following a Kaizen event that is a meeting involving laboratory personnel and the laboratory medical director, several workflow optimizations were introduced: enhanced registration of test orders into the laboratory information system (LIS), allowing for increased validation and entry of tests throughout the day; expansion of the number of workstations dedicated to blood culture entry into the LIS; increased frequency of daily evaluations of microbiological cultures to enable real-time detection of bacterial growth; and more efficient use of the Vitek MS® and Vitek 2 Compact® systems. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) validation was also distributed across multiple periods during the day (

Table 1). Altogether, these measures contributed to a significant improvement in sample flow management.

As part of the process, laboratory technical staff were trained in the appropriate handling of blood cultures as critical samples, generating a state of mind of awareness. Estimated manual activity and incubation times are shown, along with expected time savings and percentage gains after Kaizen improvement activity (

Table 2).

To assess the impact of the intervention, June 2023 was selected as the reference period, during which 496 blood culture tests were processed in the laboratory.

The key performance indicators measured during the process included changes in TATs for critical microbiology tests, with a target set to reduce the final report delivery time by 20%. The following equation was used for the calculation:

Improvement (%) = (Time Before − Time After) / Time Before × 100.

This study was designed as a prospective intervention aimed at optimizing workflow in the microbiology laboratory of Hospital Roberto del Río, using a change management approach based on the Kaizen methodology. Due to variability in workflows and the implementation of specific technologies, no formal sample size calculations were performed. The evaluation periods were selected based on clinical and operational criteria established by the laboratory. A non-probabilistic, convenience sample was used, consisting of blood culture tests processed during the pre- and post-intervention periods.

The statistical analysis was performed with an 80% power and a significance level of 5%. Continuous variables were described using medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), as the data did not follow a normal distribution. The Mann–Whitney U test was used for comparison of medians between groups. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages. GraphPad Prism 9® software was used for data analysis, and p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The dataset used for analysis was extracted from REAL®.

3. Results

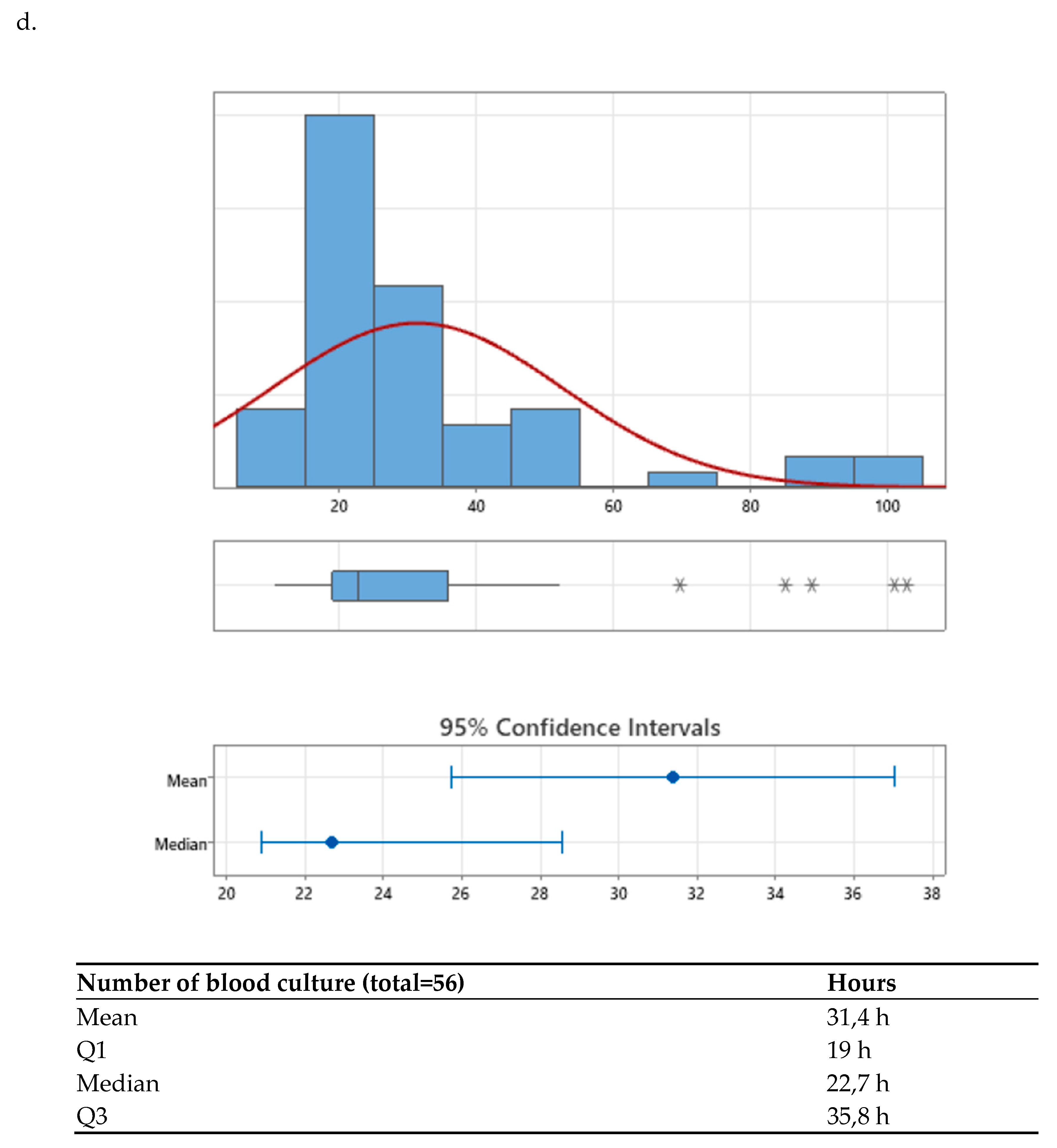

The early diagnosis of positive blood culture bottles is of critical importance, given the significant clinical implications associated with the identification of bacteremia and antimicrobial treatment [

10]. At the HRRIO, approximately 40 blood culture bottles are processed daily, with an average annual positivity rate of 5.8%. During the pre-intervention period, the mean time to preliminary Gram stain reporting, from the moment the bottle entered the laboratory, underwent the initial intra-laboratory checkpoint, and was subsequently cultured using the Virtuo®, was 22.7h (19.0-35.8 h). This variation is primarily explained by differences in microbial growth rates within the incubator. The mean time to final antimicrobial susceptibility reporting was 68.22h (56-188.6 h). In contrast, the average time to a final negative result was 184.1h (154.3–188.6h).

The staff processed positive blood cultures in a single batch per shift for both identification and susceptibility testing. As a result, blood cultures could take up to 12 hours to complete processing, meaning that personnel were not available to validate the culture once it was ready, because this occurred outside regular working hours.

Table 3.

Kaizen proposed strategy.

Table 3.

Kaizen proposed strategy.

| # |

Details strategy |

| 1 |

Elimination of approximately 5 hours from the total processing time per positive blood culture bottle (see Table 2). |

| 2 |

Increased productivity through the addition of a dedicated workstation at the laboratory’s sample admission area. |

| 3 |

Technological improvements in the real® to enable integration with the central LIS, improve sample tracking (e.g., anatomical site, urinary sediment analysis), and enhance dashboard compatibility with the real® environment. |

| 4 |

Full automation of the validation process for negative blood culture vials. |

| 5 |

Implementation of culture plate boxes by time range of incubation, allowing continuous evaluation, maldi-tof identification, and as setup throughout the shift, ending once-daily batch processing. |

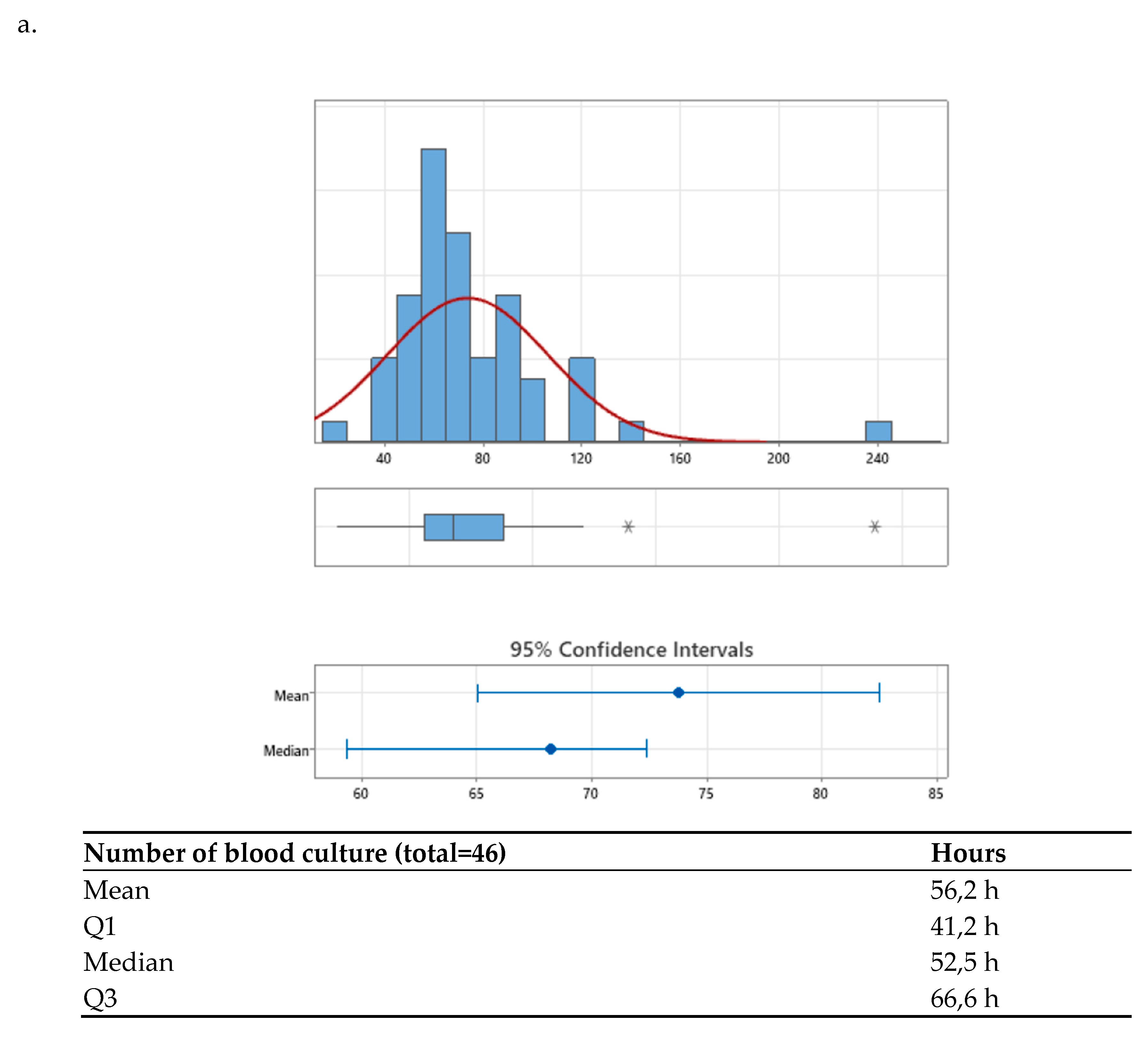

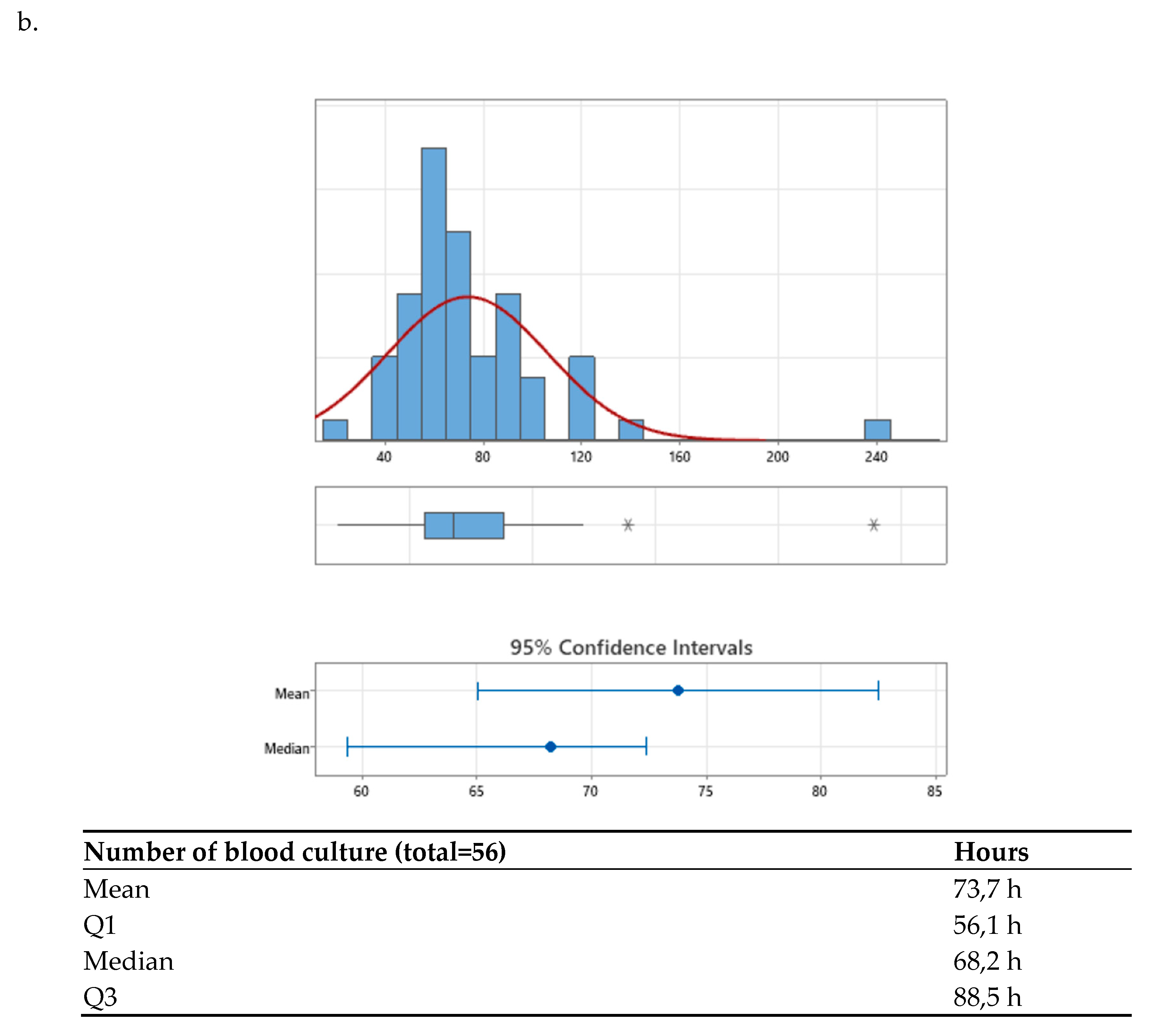

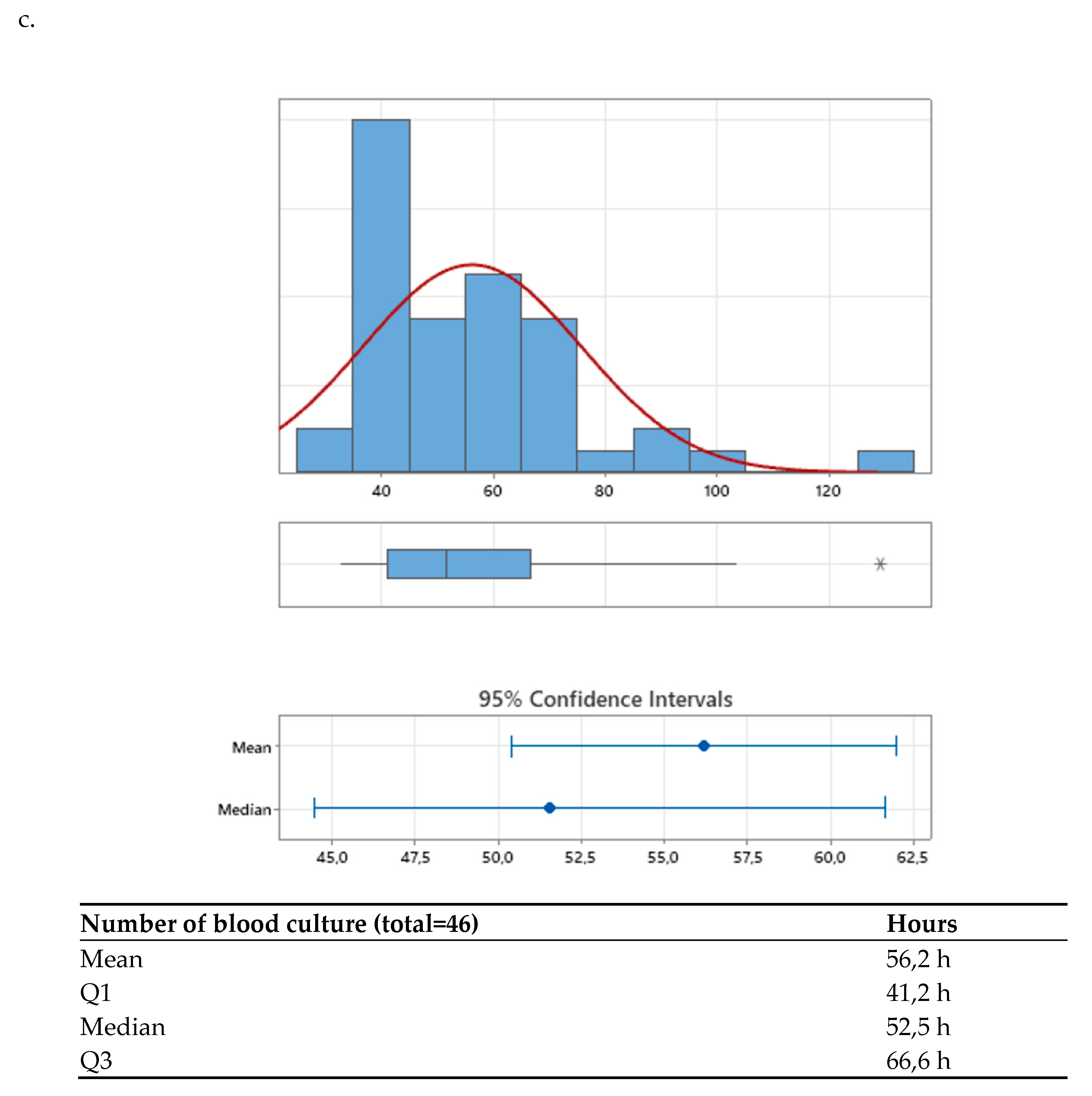

After the agreed interventions were implemented, the median TAT was compared between the pre-intervention period (68.22 hours [56.14–88.59]) and the post-intervention period (51.52 hours [41.17–66.57]) (

Figure 2a,b). A significant difference was observed, with a p-value < 0.001, corresponding to a 24.48% reduction in time to final result, achieving the established goal (>= 20%).

Additionally, when analyzing the distribution graphs of TAT results, it was noted that values below the third quartile decreased from 88.6 hours pre-intervention to 66.5 hours post-intervention, with a p-value < 0.001 (

Figure 2b).

4. Discussion

Our laboratory is a high-complexity laboratory focused on addressing the health problems of the assigned pediatric population, including immunocompromised patients, those undergoing cardiac surgery, polytrauma cases, neurosurgical patients, and individuals with comorbidities. This represents a challenging scenario from the perspective of infectious diseases, especially considering the emerging bacterial resistance observed in recent years.

An initial evaluation of various laboratory characteristics was carried out to focus the measurable objectives of this study, such as the distribution of isolated agents in positive blood cultures and their temporal distribution, as well as the willingness of human resources to participate in an evaluation process of their workflow, openness to change, and readiness for the implementation of improvements. These factors collectively justified the implementation of a Kaizen intervention. This process made it possible to identify improvement opportunities that had not been previously considered and that were feasible to implement without additional costs, within the context of being a public institution.

Among the findings identified and addressed in this study, a substantial improvement was observed in the TAT to the final report, which is clearly beneficial for timely clinical decision-making in bacteriemia. The original goal of reducing turnaround time by 20% was exceeded, achieving a 24.48% reduction. The long-term success of this type of strategy lies in the consistency of the team and in having embraced the Kaizen philosophy. Critical thinking and leadership are essential to sustain these initiatives over time and to extend them to other areas within the same laboratory. Nevertheless, it is important to highlight that the metrics for the objectives should always undergo statistical evaluation.

Trigueiro et al. observed a decrease in process variability among different laboratory operators, attributed to the standardization of processes and alignment with Kaizen evaluations. In our case, we observed a reduction in the team’s average processing time; however, we were unable to quantify differences between individual operators. This aspect could be considered for future interventions in our laboratory [

2].

Despite the partial automation of the laboratory, there were relevant findings that support those reported in other microbiology automation studies, such as those by

Trigueiro et al. and

Bailey et al. These studies showed that the laboratory automation process improved efficiency and TAT for the final clinical report [

2,

20].

Finally, although this was not the initial focus of the research, through the evaluation of processes using the Kaizen/LEAN methodology, the laboratory decided to implement interventions in other areas of microbiological sample processing, including all processed samples that involved cultures (urine cultures, sterile fluids, etc.).

Among the relevant changes, the loading schedule for identification by MALDI-TOF MS® and antimicrobial susceptibility testing by Vitek 2 Compact® for positive blood cultures was adjusted to between 7:30 and 8:30 AM. A dedicated medical technologist was assigned exclusively to Microbiology activities and support for AST V2C® loading. Additionally, plate reading was organized into defined time blocks to enable multiple positive culture identifications throughout the shift.

Optimizing laboratory workflow is a complex process that requires coordination among clinical teams, nursing staff, laboratory personnel, IT systems, supply chains, and external providers to ensure the delivery of reliable, timely, and safe diagnostic results. Specialized consulting serves as an additional resource to support the alignment of operational processes. Achieving this objective depends on personnel training, forward-thinking technical leadership, and up-to-date microbiological knowledge. Any intervention aimed at improving workflow must be planned with careful consideration of current and future operational needs, enabling the laboratory to respond effectively- starting today- to the diagnostic challenges that public health will face over the long period of time.

POC can support the diagnosis of certain specific conditions, such as molecular virological testing performed at the patient’s side in outpatient care, emergency departments, or critical care units, as well as direct diagnosis from positive blood culture bottles [

21,

22,

23,

24]. However, POC does not cover the entire laboratory routine; the use of conventional technologies remains essential for microbiological diagnosis and for the interpretation of the antibiogram [

25,

26]. The use of these POC tools must be strictly overseen by the laboratory, and requires trained personnel outside the laboratory who can both apply the tests and recognize their limitations. This makes implementation challenging for healthcare institutions in Latin America [

27]. Therefore, to ensure therapeutic success and appropriate adjustment to microbiological therapy, laboratories must intensify efforts to reduce turnaround times, from pre-analytical processes to the final report available for clinical staff in healthcare services [

28,

29,

30,

31].

According to Tseng

et al., an optimized microbiological result in a patient with sepsis can reduce hospital stay and the length of stay in the ICU, including a decrease in 28-day mortality [

15]. Therefore, conducting Kaizen studies may represent a low-cost alternative for healthcare institutions, enabling them to adjust their workflows, reorganize healthcare personnel, and even, why not, incorporate new POC technologies monitored by the laboratory, given the greater availability of laboratory human resources.

Limitations It is important to acknowledge that the most effective solution for the laboratory scenario would have been the implementation of a 24/7 professional staffing model. However, public institutions in Chile face significant challenges in creating new positions, especially those requiring 24-hour coverage.

Therefore, the proposed intervention was designed within a conservative scenario from the perspective of human resources.

It is also important to state that no sample size calculation was performed, which introduces a potential bias. Additionally, the selection of July 2022 as the pre-intervention baseline assumed that monthly trends remain relatively stable throughout the year. Regarding the 'time to Gram' metric, it is important to note that measurements were taken from the moment the bottle was loaded into the Virtuo® system. Ideally, this interval should have been measured from the time of bottle positivity in Virtuo®, to reduce the bias introduced by differential growth rates among microbial genera.

5. Conclusions

Laboratory consulting as a strategy to optimize workflow in microbiology laboratories should be considered across Latin America, regardless of the laboratory's level of technological development. The insights gained from understanding the daily routine and workflow are highly valuable when evaluating the implementation of new technologies or when adjusting work processes in settings that do not necessarily operate on a 24/7 workflow.

In our experience, the process implemented in our institution using the Kaizen model was considered successful, achieving measurable optimization of blood culture TAT, which in turn allowed us to transfer this experience to improve other processes within the microbiology laboratory. Most importantly, delivering results to clinical staff within a significantly shorter timeframe enables timely adjustment of antimicrobial therapy, thereby reducing the duration of empirical antimicrobial treatment.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study did not require ethical approval.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (GPT-5, OpenAI) for the purpose of assisting in translation from Spanish to English. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AST |

Antimicrobial susceptibility |

| COVID-19 |

Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| HRRIO |

Hospital Roberto del Río |

| IQR |

Interquartile range |

| IT |

Information technology |

| LIS |

Laboratory information system |

| MALDI-TOF |

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry |

| POC |

Point of Care |

| PCR |

Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PDCA |

Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle |

| TAT |

Turn-arround time |

| V2C |

Vitek 2 Compact® automated identification and susceptibility testing system |

References

- Plebani M. Quality in laboratory medicine: an unfinished journey. J Lab Precis Med. 2017, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Trigueiro G, Oliveira C, Rodrigues A, Seabra S, Pinto R, Bala Y, Gutiérrez Granado M, Vallejo S, Gonzalez V, Cardoso C. Conversion of a classical microbiology laboratory to a total automation laboratory enhanced by the application of lean principles. Microbiol Spectr 2024, 12, e02153–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, C. , Vega C, Rojas C. Implementación del laboratorio clínico moderno. Revista médica Clínica las Condes 2015, 26, 794–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonios K, Croxatto A, Culbreath K, Current State of Laboratory Automation in Clinical Microbiology Laboratory. Clinical Chemistry 2022, 68, 99–114. [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, R. , Laboratory turnaround time. The Clinical biochemist. Reviews 2007, 28, 179–194. [Google Scholar]

- Kotter J, 2013. Choosing Strategies for Change. Available online: https://projects.iq.harvard.edu/files/sdpfellowship/files/day3_2_choosing_strategies_for_change.pdf.

- Alvarado K, Pumisasho V, Continuous improvement practices with Kaizen approach in companies of the metropolitan district of Quito: An exploratory study. Intangible capital 2017, 13. [CrossRef]

- Declerck, B. , Swaak, M., Martin, M., & Kesteloot, K. Activity-based costing analysis of laboratory testing in clinical chemistry. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine 2021, 59, 1369–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, A. , & Emmendoerfer, M. Innovation labs in South American governments: Congruencies and peculiarities. Brazilian Administration Review 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samara, M. N. , & Harry, K. D. Leveraging Kaizen with process mining in healthcare settings: A conceptual framework for data-driven continuous improvement. Healthcare 2025, 13, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senok, A. , Dabal, L. A., Alfaresi, M., Habous, M., Celiloglu, H., Bashiri, S., Almaazmi, N., Ahmed, H., Mohmed, A. A., Bahaaldin, O., Elimam, M. A. E., Rizvi, I. H., Olowoyeye, V., Powell, M., & Salama, B. Clinical impact of the BioFire Blood Culture Identification 2 Panel in adult patients with bloodstream infection: A multicenter observational study in the United Arab Emirates. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, M. , Razavi Bazaz, S., Zhand, S., Sayyadi, N., Jin, D., Stewart, M. P., & Ebrahimi Warkiani, M. Point-of-care diagnostics in the age of COVID-19. Diagnostics 2020, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peri, A. M. , Ling, W., Furuya-Kanamori, L., Harris, P. N. A., & Paterson, D. L. Performance of BioFire Blood Culture Identification 2 Panel (BCID2) for the detection of bloodstream pathogens and their associated resistance markers: A systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies. BMC Infectious Diseases 2022, 22, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reszetnik, G. , Hammond, K., Mahshid, S., et al. Next-generation rapid phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 9719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, H. Y. , Chen, C. L., Chen, W. C., Kuo, Y. C., Liang, S. J., Tu, C. Y., Lin, Y. C., & Hsueh, P. R. Reduced mortality with antimicrobial stewardship guided by BioFire FilmArray Blood Culture Identification 2 panel in critically ill patients with bloodstream infection: A retrospective propensity score-matched study. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 2024, 64, 107300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cintrón, M. , Clark, B., Miranda, E., Delgado, M., & Babady, N. E. Development and evaluation of a direct disk diffusion, rapid antimicrobial susceptibility testing method from blood cultures positive for Gram-negative bacilli using rapid molecular testing and microbiology laboratory automation. Microbiology Spectrum 2025, 13, e0240124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totty, H. , Ullery, M., Spontak, J. et al, A controlled comparison of the BacT/ALERT® 3D and VIRTUO™ microbial detection systems. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2017, 36, 1795–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarbrough, M. L. , Wallace, M. A., & Burnham, C. D.,Comparison of Microorganism Detection and Time to Positivity in Pediatric and Standard Media from Three Major Commercial Continuously Monitored Blood Culture Systems. Journal of clinical microbiology 2021, 59, e0042921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timsit, J. F. , Ruppé, E., Barbier, F., Tabah, A., & Bassetti, M. Bloodstream infections in critically ill patients: an expert statement. Intensive care medicine 2020, 46, 266–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, A. L. , Ledeboer, N., & Burnham, C. D. Clinical Microbiology Is Growing Up: The Total Laboratory Automation Revolution. Clinical chemistry 2019, 65, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W. S. , Ho, C. W., Chan, T. C., Hung, J., To, M. Y., Leung, S. M., Lai, K. C., Wong, C. Y., Leung, C. P., Au, C. H., Wan, T. S., Zee, J. S., Ma, E. S., & Tang, B. S. Clinical Evaluation of the BIOFIRE SPOTFIRE Respiratory Panel. Viruses 2024, 16, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graff, K. E. , Palmer, C., Anarestani, T., Velasquez, D., Hamilton, S., Pretty, K., Parker, S., & Dominguez, S. R. Clinical Impact of the Expanded BioFire Blood Culture Identification 2 Panel in a U.S. Children's Hospital. Microbiology spectrum 2021, 9, e0042921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peri, A. M. , Ling, W., Furuya-Kanamori, L., et al. Performance of BioFire Blood Culture Identification 2 Panel (BCID2) for the detection of bloodstream pathogens and their associated resistance markers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies. BMC Infectious Diseases 2022, 22, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antiochia, R. Paper-Based Biosensors: Frontiers in Point-of-Care Detection of COVID-19 Disease. Biosensors 2021, 11, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, W. R. , Hidayat, L., Bolaris, M. A., Nguyen, L., & Yamaki, J. The antibiogram: key considerations for its development and utilization. JAC-antimicrobial resistance 2021, 3, dlab060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinker, K. P. , Hidayat, L. K., DeRyke, C. A., DePestel, D. D., Motyl, M., & Bauer, K. A. Antimicrobial stewardship and antibiograms: importance of moving beyond traditional antibiograms. Therapeutic advances in infectious disease 2021, 8, 20499361211011373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokkalla, A. K. , Recio, B. D., & Devaraj, S. Best Practices for Effective Management of Point of Care Testing. EJIFCC 2023, 34, 245–249. [Google Scholar]

- Khalifa, M. , & Khalid, P. Improving laboratory results turnaround time by reducing pre analytical phase. Studies in health technology and informatics 2014, 202, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sancho, D. , Rezusta, A., & Acero, R.. Integrating Lean Six Sigma into Microbiology Laboratories: Insights from a Literature Review. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland) 2025, 13, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, B. A. , Baron, J. M., Dighe, A. S., Camargo, C. A., Jr, & Brown, D. F. Applying Lean methodologies reduces ED laboratory turnaround times. The American journal of emergency medicine 2015, 33, 1572–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherie, N. , Berta, D. M., Tamir, M., Yiheyis, Z., Angelo, A. A., Mekuanint Tarekegn, A., Chane, E., Nigus, M., & Teketelew, B. B. Improving laboratory turnaround times in clinical settings: A systematic review of the impact of lean methodology application. PloS one 2024, 19, e0312033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).