1. Introduction

The high value of big data systems is that they play a vital role in the operation of all industries today in the digitalized world, including healthcare, financial oriented, telecommunications, and e-commerce. These systems are designed to manage gigantic amount of structured and unstructured data, where the volume, velocity, and variety are typically defined by the famous 3Vs: Volume, Velocity, and Variety. This classification has over time witnessed the addition of other dimensions that have included Veracity, Value, and Variability as data ecosystems continue to grow in complexity and dynamism (ScienceDirect, 2024; Hussain et al., 2024). The analyzing possibilities of big data have empowered companies to innovate, streamline their operations, and develop closer understanding of the customer behaviour. Nevertheless, big data has most of the same qualities that make it interesting: it is large, sensitive, and works in real-time, which makes it of increased interest to cyber threats.

Figure 1.

he “Vs” characteristics of big data — including Volume, Velocity, Variety, Veracity, Value, and Variability.

Figure 1.

he “Vs” characteristics of big data — including Volume, Velocity, Variety, Veracity, Value, and Variability.

Conventional perimeter-security approaches have since proven weak with the transformation towards the cloud-native and hybrid data structures. Introduction of distributed systems, remote work, and third-party integrations has broadened the attack surface with vital data resources at risk of complex attackers. Access control defines the interaction between sensitive information and its users and systems and is one of the fundamental security mechanisms. However, in most organizations even now, traditional Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) or Attribute-Based Access Control (ABAC) mechanisms are used which limit access and contain over exclusive policies of access control. Being organized and readily applied, these systems are not attentive enough to the changing risks and cannot be modified to capture such contextual variables as user behaviour, access time, device state, and geolocation (Ferraiolo & Kuhn, 1992; Hu et al., 2014).

The recent high profile data breaches have served as an illustration of how these limitations may be exploited. In 2024, Snowflake breach and in 2019, Capital one breach proved the power of weak authentication, static credentialing and misconfigured roles policy in allowing attackers to access high volumes of sensitive data without authorization (Mandiant, 2024; Muscat, 2019). In both instances, multi-factor authentication (MFA) and a real-time anomaly detection were not put in place; this added remarkably to the time taken to identify and fix the breaches. Such attacks prove the necessity of evolution of access control models, i.e. the evolution to dynamic context-sensitive rather than fixed and identity-based policy-based approach that can assess the risk on an ongoing basis.

To overcome these drawbacks, this report introduces the Adaptive Context-Aware Security Framework (ACASF) that is a new model of access control based on the Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA) concepts (Brohi et al., 2020). In contrast to legacy models, ACASF is ready to analyse the contextual information and user behaviour continuously and make risk-based decisions in real-time. It functions on the assumption that no user and device can be trusted automatically, whether they are inside or outside the network. The combination of the risk scoring engines, geolocation tracking, and behavioural analysis tools should help ACASF achieve a scalable, smart, and responsive security position that would be relevant to the requirements of the contemporary big data infrastructure (Rose et al., 2020; Jun et al., 2024).

2. Problem Identification

Contrary to the conventional access control functions such as RBAC and ABAC, they can no longer be relied upon to help protect an advanced and rapidly changing threat that big data platforms bear. Such models are naturally static. RBAC always grants permission with respect to the fixed roles in an organization whereas ABAC makes access decisions considering a set of predefined attributes. Despite the structured and rule-based access control that is present in both the models, they do not have the capability to dynamically determine risk or react to behavioural anomalies in real time. Because of this, such systems most likely do not even identify and stop insider attacks, adversary pivoting, or privileged single-use accounts hijacking (Hu et al., 2014; Ferraiolo & Kuhn, 1992; Kiyani et al., 2024).

The first and fundamental shortcoming of these fixed models is the inability to consider the contextual data when being assessed access requests. They fail to consider that some form of dynamic environment is involved like the time of logging, geolocation, IP address irregularities, device fingerprint, and the rate of access. Attackers can use this blind spot to leverage legitimate credentials that they acquire and use such credentials to breeze past the authentication controls. A good example is the 2024 Snowflake attack. In this situation, the attackers managed to use the stored and unencrypted credentials on the employee devices and because of the absence of enforced MFA and contextual authentication got unauthorized access into several customer databases (Bleeping Computer, 2024; Mandiant, 2024; Krishnan et al., 2021). And in a like manner, the 2019 Capital One event was able to exfiltrate sensitive data over a long-term period by taking advantage of permissive IAM roles and inadequate real-time monitoring (Abbas & al-Talak, 2021; Muscat, 2019; Hanif et al., 2022).

There are common underlying causes of these incidents: excess reliance on credential-based authentication, the absence of granular access policies, low-quality or non-existent MFA use, and a lack of behavioural analytics. In both instances adversaries utilized the valid credentials by means that evaded conventional detection mechanisms. Both RBAC and ABAC only leverage access upon roles or attributes created at the time of logging in hence cannot react on the emerging risks even when a user is already logged in. In addition, these models are not dynamic but rather system rights are not altered in real-time and not applicable to organizations where rights of users and needs tend to change a lot.

These vulnerabilities have been worsened by increase in cases of cloud consumption as well as remote working (Linqiang et al., 2024; Humayun et al., 2022). Due to the complexity of security management, many cloud-based, or hybrid infrastructures run on old security settings that lack the ability to perform adaptive control or access modern threat intelligence solutions. This usually leads to over privileged accounts, breach detection slow, and non-compliant with some regulations.

These gaps should be filled with a more flexible, real-time access control approach in which dynamic contextual analysis and continuous risk assessment are being incorporated. To address these issues, The Adaptive Context-Aware Security Framework (ACASF) is offered. ACASF is built on principles of Zero Trust and constantly evaluates availability requests through user actions and environmental indications, including device status, geography and date of the day. Instead of the static permissions, it introduces risk-based and just-in time access decisions where permissions are granted when all contextual checks have been met (Manchuri et al., 2024; Jabeen et al., 2023). The proposed ACASF will become a more effective and extendable protection system of contemporary data-focused business by overcoming the limitations of conventional models and allowing predictive threat hunting.

3. Case Study Analysis

3.1. Case I (Snowflake Data Breach 2024)

3.1.1. Background

In April and June 2024, the data breach occurred when several organizations were accessed through their Snowflake customer instances by an unauthorized person. Affected companies are companies such as AT&T, Santander Bank and Ticketmaster. It was found in the study that the credentials of the attackers were due to most of the non-Snowflake computers that have been infected with malware that steals information. Attackers could access consumer accounts with their login and password because multi factor authentication (MFA) was not turned on these credentials (Ravichandran et al., 2024; Khan et al., 2021). According to Mandiant, it confirmed that all these incidents were tied to the leakage of credentials of the clients but not some system flaw of Snowflake (Bleeping Computer, 2024; Muzafar & Jhanjhi, 2019). To summarize, The Snowflake breach in 2024 was caused using usernames and passwords that were not encrypted and existed on the computers of the employees besides being located on a project tool called JIRA. Such credentials were used to access accounts of various Snowflake clients, such as Ticketmaster and Santander (1Kosmos2024; Muzammal et al., 2020).

3.1.2. Root Cause Analysis

Hackers stole static credentials from Snowflake customers using information-stealing malware, some dating back to 2020, where these credentials were never changed, allowing them to access client environments and steal sensitive data. Sensitive information including payment and personal identification information stolen as a result (Mandiant, 2024; Riza et al., 2025). According to CISA (2023), multifactor authentication (MFA) is an important security approach where it requires a user to verify their identity by providing a combination of two or more authenticators, before service grants user access. In this case, since many customers do not use MFA, attackers able to enter Snowflake easily, using only stolen accounts and passwords, they can even download data without any resistance. Moreover, the account linked to the credentials does not have strict permission management. Role inheritance and unreviewed permissions allowed attacker broad access to several Snowflake database when they log in illegally. This over-authorization significantly increased breach impact. Because attackers used valid but stolen credentials, their activities blended in with normal usage, where demonstrates the absence of real-time behavioral analysis brings such drawbacks, delayed breach detection for weeks.

3.1.3. Security Countermeasures

To prevent such credentials breach, company should disable static credentials, instead, they should use dynamic token-based authentication like OAuth 2.0 with short-term access tokens and automatic key rotation (Authentication Methods at Google, n.d; Saeed et al., 2022). MFA should be enforced across all accounts, especially administrative as it protects against unauthorized access even if credentials are stolen (CISA, 2023). Deploying real-time monitoring and anomaly detection mechanism would help in this case where alarms can be sent out instantly when unfamiliar behaviour is detected. Alerts based on geolocation anomalies, login velocity, or unusual access frequency can reduce breach duration.

3.2. Case II (Capital One Data Breach 2019)

3.2.1. Background

In March 2019, a former Amazon Web Services (AWS) engineer, Paige A. Thompson, used the configuration issue in Capital One Web Application Firewall (WAF) to attack the company in a SSRF (Server-Side Request Forgery) manner. The intruder has gained access to an EC2 instance metadata, stolen temporary AWS IAM credentials, and exfiltrated sensitive data of AWS S3 storage buckets. The breach remained unnoticed until July of 2019 when one of the researchers discovered data stolen placed on the internet. More than 100 million U.S. and 6 millions of Canadian customer records have been breached, referring to credit scores, bank account information, and other confidential information (Muscat, 2019; Seng et al., 2024).

3.2.2. Root Cause Analysis

The attacker abused an SSRF vulnerability to access EC2 metadata and retrieve temporary IAM credentials. Since these credentials provided over-permissive access to AWS S3 resources due to broad, static IAM roles, it enables downloading of massive datasets (Abbas & Al-talak, 2021; Khan et al., 2022; Sindiramutty, Jhanjhi, Tan, Lau, et al., 2024). Attackers able to steal IAM role credentials to commit illegal acts, showed that IAM Role uses static permission control, cannot organize and respond to abnormal behaviour in a timely manner, and static authorization is too broad, allowing attackers to easily access sensitive information through credentials. What’s more surprisingly, the attackers conducted extensive data extraction activities for several months without setting off any alarms or interceptions. Although AWS CloudTrail logged all access activities, there were no behaviour analytics tools like AWS GuardDuty or Macie enabled. Again, MFA is not required (Sindiramutty et al., 2024; Shah et al., 2022). The attacker used IAM credentials without triggering any MFA verification. Even though Capital One had IAM roles in place, MFA was not enforced for temporary credentials, allowing attacker full access when they obtained tokens.

3.2.3. Security Countermeasures

As mentioned, all privileged IAM roles should require MFA and use short-lived credentials via AWS STS (Security Token Service) and setting token expiration limitations (Token Expiry), to reduce the attack window in case of theft. AWS IAM Access Analyzer should also be used to determine whether resources like S3 are publicly accessible and to find unexpected access permissions in IAM policies. (AWS, 2023; Sindiramutty et al., 2024). Furthermore, enabling comprehensive log monitoring and behaviour analysis system is important as well since it could deliver early alerts through permission scanning or impossible trips. Such abuses could have been detected and dealt with automatically if GuardDuty had been set up and activated in time to monitor long-term, systematic, and large-scale operations. Limiting IAM users to read things under specified routes and using tag-based access controls to separate permissions for various environments or user roles are two ways to stop this behaviour AWS. (2023).

4. Proposed Secure System

4.1. Overview

In this section, we will focus on interpreting the overarching architecture of the proposed solution, emphasizing its structural composition, functional modules and implementation mechanism. As stated, the limitations of traditional access control models have been indicated due to these days widespread phenomenon of cyberattacks, credential exposure, and data theft in large-scale systems such as cloud data platforms. To be more specified, the Snowflake data breach in 2024 have showcased that reliance on static permissions can lead to massive data leaks. Hence, to address these vulnerabilities, this paper proposes the Adaptive Context-Aware Security Framework (ACASF), a dynamic, adaptive, and context-aware security model grounded in the principles of Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA). Basically, Zero Trust is about assuming that no user, device, or network should be absolutely trusted, even those within the organizational boundary, to get rid of the traditional perimeter-based security method. Instead, every requested access must be evaluated continuously based on contextual and behavioural signals and permit explicitly according to dynamic risk assessments (Rose et al., 2020; Sindiramutty, Prabagaran, Jhanjhi, Ghazanfar, et al., 2024).

In accordance with this, ACASF employs a dynamic, context-driven decision-making process by incorporating real-time contextual data such as device identity, IP address origin, time of access, geolocation, and sensitivity level of requested resources. By integrating such contextual information into access pipeline, this infrastructure shift away from static identity-based control to flexible and real-time model, where enables risk-aware, fine-grained control that evolves with user’s behaviour and environmental conditions. This strategy, inspired by Zero Trust, ensures that access decisions are evaluated continuously, not just at login, but also the procedure after it, ensuring a more resilient and intelligent security posture.

4.2. Core Components

The proposed ACASF provides authorization capabilities, which embody the important security purpose of Defence in Depth. In general, Defense in Depth means applying multiple layers of security defence where various techniques and controls are implemented and deployed to mitigate the security risks (Alsaqour et al., 2021; Sindiramutty et al., 2024). Furthermore, Ridha Khedri et al., (2017) discuss implementing Defense in Depth principles with dynamic access control, underscoring the relevance of multi-layered decision-making logic, where this paper will talk about later. There are five key components included in the proposed ACSF to collect, analyse, an=d enforce access decisions. It consists of context collector, risk engine policy decision point (PDP), policy enforcement point (PEP), and audit and feedback system, where each contributing to a dynamic, risk-informed access control process.

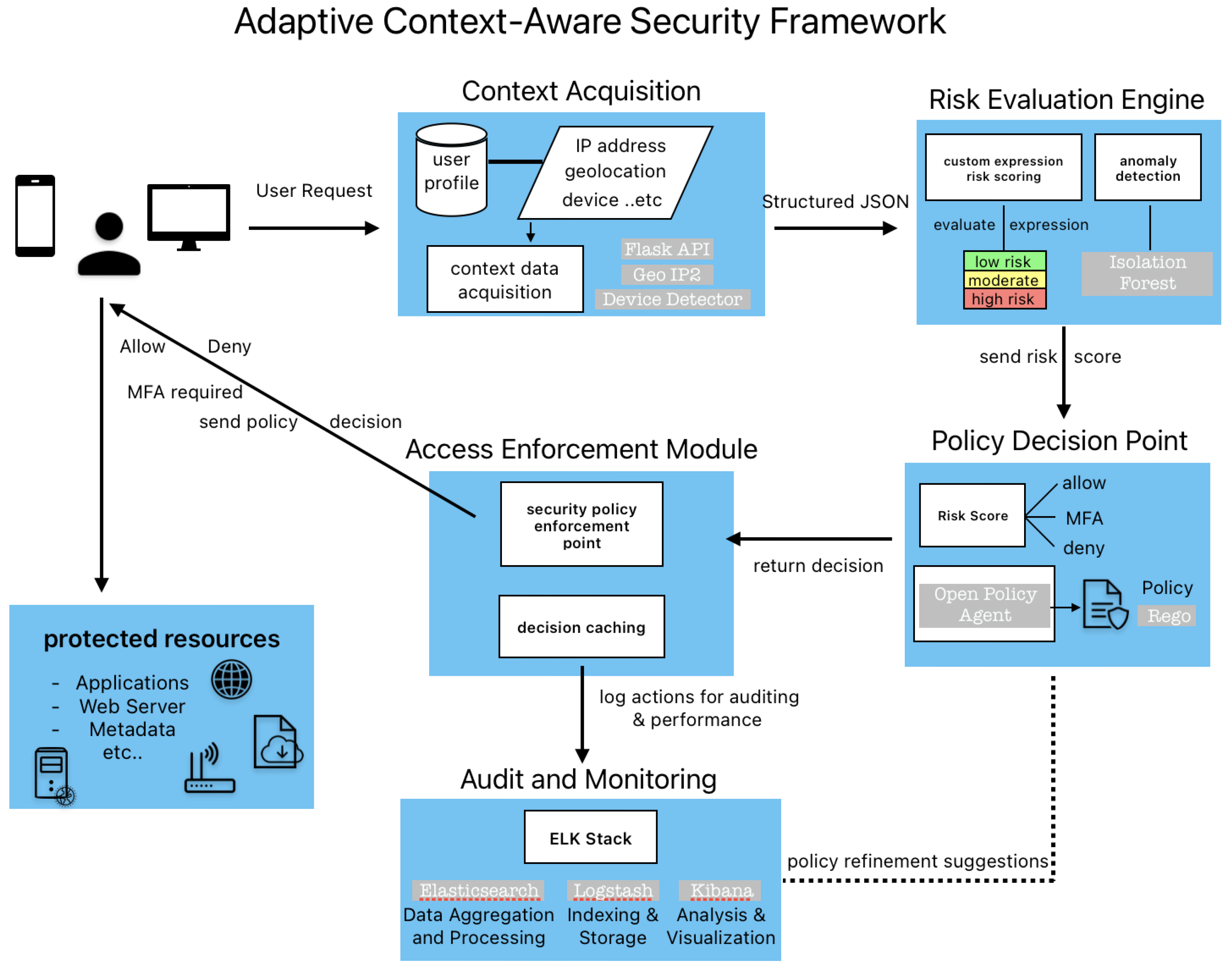

Figure 1 indicates a brief architecture of the proposed ACASF.

Figure 2.

The ACSAF architecture.

Figure 2.

The ACSAF architecture.

4.2.1. Context Collector

The first layer, context collector, which acts as a tool that aggregates and prepares information, particularly contextual data such as user, IP address, geolocation, device fingerprints, and so on. Before proposing this architecture, the problems and questions are stated: how confident is the subject’s identity for this peculiar request? Does it allow to grant access of resources, or information based on the level of confidence in the subject’s identity? Is the device used for requesting having the legit security status? Will there be a change of confidence level due to other factors that should be considered (e.g., time, location of subject)? Generally, to develop and maintain the risk-based policies for resources access is the purpose of collecting metadata, which will be discuss in this section. In this layer, environmental behavioural attributes such as user ID, geolocation, device type and fingerprint, origin of IP address, browser agent, and time of access will be collected as they are the key points in determining whether the access request is aligned with typical user behaviour and organization policies. Upon receiving a request, this component intercepts it through a Flask-based API intermediate and extracts critical metadata immediately. Flask is a lightweight Python web framework used to construct RESTful APIs that act as the gateway for user access requests. (Kunal Relan & Springerlink (Online Service, 2019)) Device characteristics are analysed using the Device Detector, a client-side parsing library where extracts information about the operating system, browser, and device type from user-agent strings, whilst request headers and network attributes may be collected for further fingerprinting. To be more specific, this layer will be utilizing GeoIP2, developed by MaxMind, to detect geolocation from IP addresses, capturing information such as country, city, and Internet Service Provider (ISP). At the same time, there will be a sensitivity tagging where the target resource (e.g., file, database table, service) is tagged based on its level of sensitivity, which play a vital role on influencing the later risk decision at the downstream. The Context Collector complies these details into a structed JSON object, where it is a underlying text-based format for present as structed data based on JavaScript object syntax (Working with JSON - Learn Web Development | MDN (2024)), after collecting and forwards them to the Risk Engine, which then discuss below, for analysis.

4.2.2. Risk Engine

Coming to the analytical core of ACASF, Risk Engine, is responsible for evaluating the access context and generating a real-time risk score. This layer applies a scoring algorithm that assigns weighted values to a range of contextual indicators when it received the structed context JSON from the Context Collector. For instance, a suspicious device or login from a foreign location will lead to positively to the risk score, while familiar access patterns reduce it. Specifically, the score is calculated regarding the configurable risk matrix and compared against pre-defined scoring, where 0-30 considered as low, 31-60 counted as moderate, and high range from 61 to 100. Thus, access attempts falling within these categories contributed to different actions, with moderate risks are called to authenticate deepen, while high-score risk attempts would be blocked outright. The Risk Engine can be enhanced with anomaly detection capabilities as well. To achieve this, we can integrate unsupervised machine learning techniques that isolates anomalies by randomly choosing features and splitting data like Isolation Forest (Fei et al., 2008; Sindiramutty, Tan, & Wei, 2024), or clustering algorithms as they enable the identification of behavioural deviations from the historical access profile of a user. Again, this continuous evaluation of access context symbolizes the Zero Trust principle of ‘never trust, always verify’ by assessing each request independently of user location or device. At last, the output of this layer consists of the computed risk score, justification of metadata, and a contextual label, where are passed to the next section, Policy Decision Point.

4.2.3. Policy Decision Point

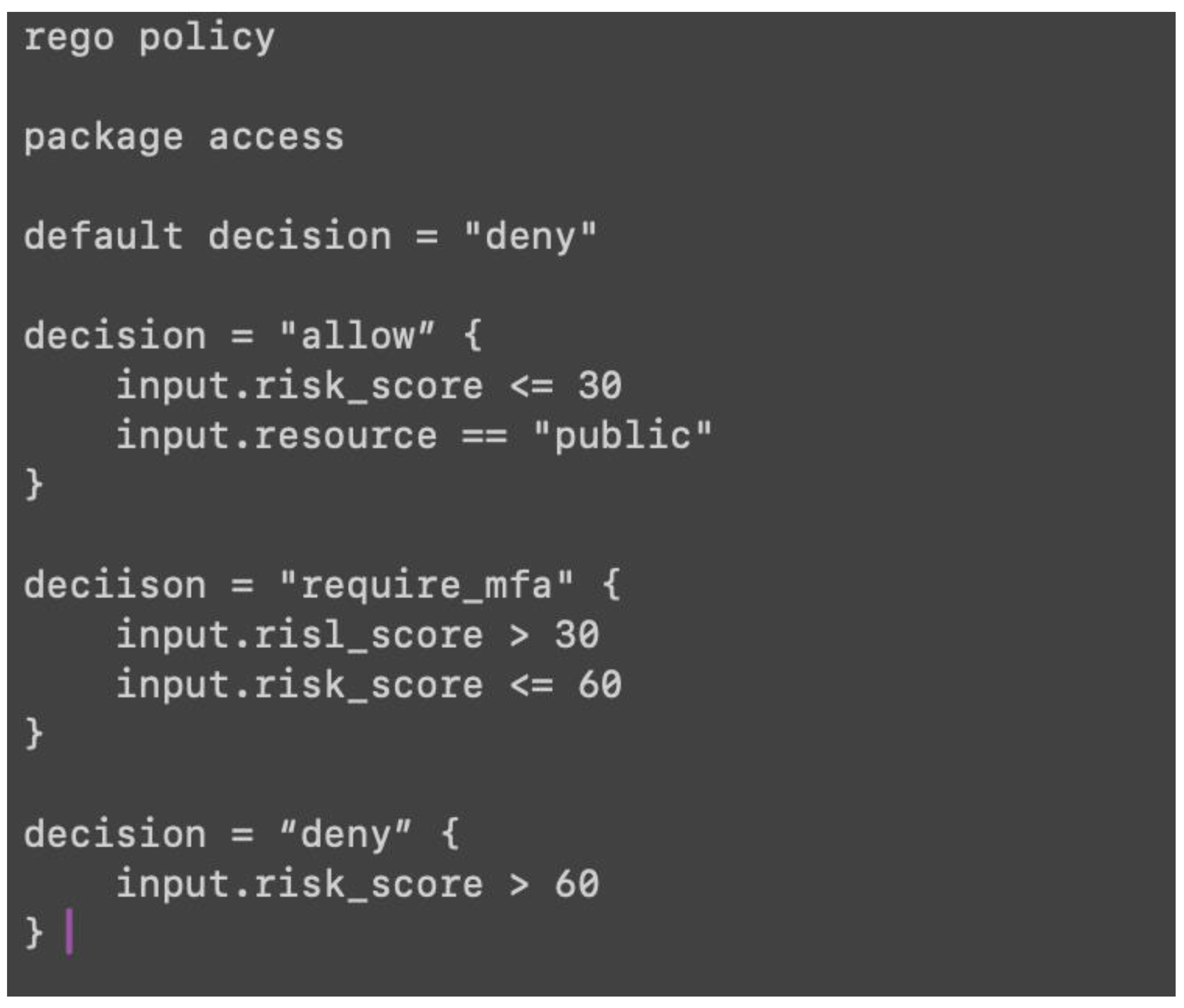

Based on the defined security policies, and the score of risk-level provided by previous layer, the access decisions are made within this Policy Decision Point section. In order to express complex access rules in a flexible and readable format, the architecture uses Open Policy Agent (OPA), a public source policy engine designed for cloud-native systems in here, leveraging its declarative policy language, Rego, which evaluates incoming input data against specified rules. These policies may include various conditions, for example, “allow access if the user is internal and the requested risk score is below minimum of scoring.”, or “deny access if the request come from unfamiliar IP address and a new device.”. Upon determined the policy logic in real-time, Policy Decision Point will return a token (e.g., allow, deny, required MFA) to the Policy Enforcement Point. Furthermore, OPA supports explanation features, allowing it to return metadata on which policy conditions were met or failed, which provide auditability and transparency in decisions making. (Introduction | Open Policy Agent, 2025; Waheed et al., 2024). In short, the use of Rego policies aligns with Zero Trust’s emphasis on strict access enforcement based on granular contextual criteria.

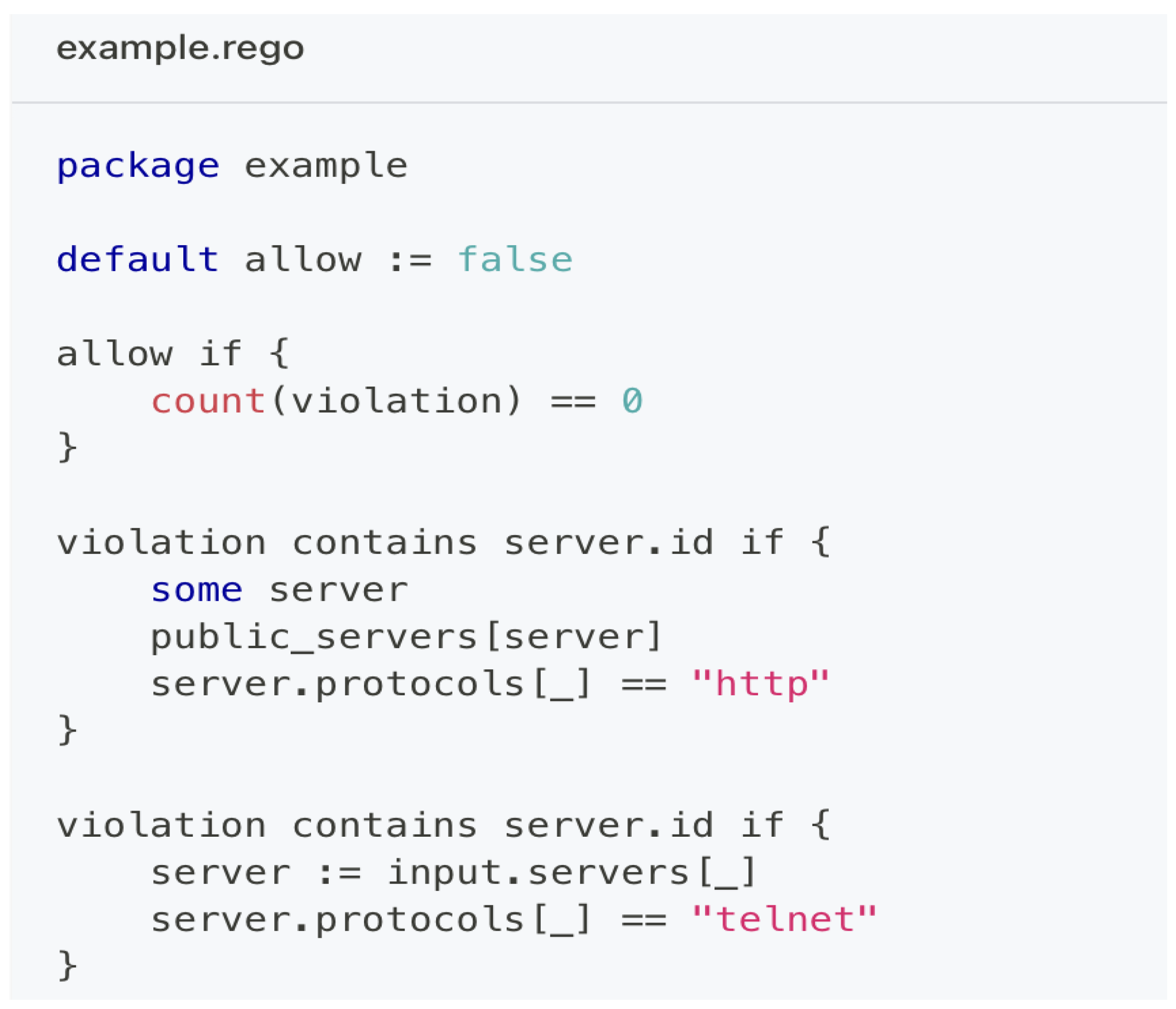

Figure 2 showed a simplified Rego policy which used to evaluate access.

Figure 3.

A Simplified Rego Policy.

Figure 3.

A Simplified Rego Policy.

4.2.4. Policy Enforcement Point

The purpose of Policy Enforcement Point is to apply, or act on the decision made by the preceding layer an-d enforce access control within the system. It is typically embedded within Flask-based application or API gateway. This layer intercepts the access request by querying the Policy Decision Point with contextual data and carries out the actions of outcome. To be more precise, it grants access to the requested resources when the Policy Decision Point returned “allow”, if “deny” is received, it blocks the user and may redirect to a logging or notification module alternately. In certain cases where additional authentication is required, like multi-factor authentication (MFA), the Policy Enforcement Point initiates the step as well. For instance, in high-risk scenarios, the Policy Enforcement Point can redirect the user to OTP page or trigger authentication. To make sure of scalability and performance, this architecture employs a Redis-backed TTL cache for repeated Policy Decision Point decisions and logs all enforcement actions to the audit system. A quick reference to the idea that enforcing real-time decisions reflects ZTA’s need for enforcement close to the resource.

4.2.5. Audit and Monitoring System

The Audit and Monitoring System as the last layer of our suggested architecture, which gives continuous visibility throughout the access control ecosystem, enabling security management as well as forensic analysis. The ELK Stack, composed of Elasticsearch, Logstash, and Kibana, is a powerful open-source platform designed for real-time log collection, search, and visualization. (Elastic, 2025; Weiqi et al., 2024) Hence, here we use the ELK Stack to gather, store and display logs produced by the Context Collector, Risk Engine, Policy Decision Point, and Policy Enforcement Point. All requests or tries, policy resolutions, and enforcement activities are indexed with related metadata to allow traceability. Helps identify repeat events, policy violations as well as the identification of possible insider threats. What we imply here is that Logstash deals with the processing and formatting of the log data that is incoming, Elasticsearch indexes the data so that it can be referred to fast, and lastly, Kibana provides dashboards and visual analytics to perform real-time monitoring (Wen et al., 2023). Moreover, the alerts in this system will have pre-defined security events, i.e., increase risk score of a particular user, or successive access rejections by unusual IP range. The Audit and Monitoring System not just reinforces the security position but also helps in reporting on compliance with regulations like ISO 27001, where the ability to generate real-time alerts, historical reports, and tamper-resistant audit trails reinforces both operational security and regulatory readiness. (Watkins, 2022)

4.3. Critical Evaluation

As we mentioned in the previous section, overview, ACASF unlike the classic examples of the traditional static-role or identity-based (identity-based access control) access control models, offer dynamic, just in time risk scoring decision making capabilities which makes it much harder to attack with modern threat mechanisms like credential compromise and abuse of insider people. Whereas the previous designs of the AC granted access based on their logon credentials after a one-time assessment, the designed proposal assesses every request of access based on the contextual information/signals like location, time, device fingerprint, IP address etc. Our proposal combined with the real-time scoring, the rule-based enforcement, through the Open Policy Agent allows us to achieve fine-grained and adaptive control, and at the same time meets the Done Right as well as the Zero Trust design principle, which is never trust but always verify. Moreover, it can be easily integrated into microservice-based clouds as it is modular in nature which enhances the flexibility to scale it and maintain.

Integrating Zero Trust Architecture with the concepts of Defense in Depth and incorporating observability with ELK stack would enable ACASF to achieve better detection, accuracy in decision-making, and accountability compared to the traditional systems based on perimeter.

5. Implementation Challenges and Feasibility

Although the implementation of Adaptive Context-Aware Security Framework (ACASF) offers a robust and intelligent access control mechanism for security purpose, there are some practical challenges and drawbacks. This section will be covering the challenges the proposed system may face when implemented and deployed into the company. We will be discussing about the potential challenges faced, limitations of the system when integrated, and the regulatory and ethical concerns that may arise. While not every challenge mentioned will be applicable to the company, this section offers a comprehensive evaluation based on wide range experiences and known implementation difficulty.

5.1. Challenges and Limitations

Despite being essential for protecting the facilities from an attack, deploying the ACASF may have various challenges that arise(Jhanjhi et al., 2025). This part will be discussing challenges and limitations such as integration complexity and compatibility, scalability, real-time processing overhead, financial limitations, user adoption, and so forth.

5.1.1. Integration Compatibility and Complexity

One of the first few faults that may occur is a compatibility issue. While in theory, the system would adjust quickly and effectively due to its adaptive nature. However, we may be overestimating the capabilities of the existing infrastructure’s equipment, where it requires significant changes or custom APIs when incorporating the proposed architecture into existing or legacy systems, especially if those systems were not designed for real-time context aware or Zero Trust access(Gill et. Al, 2022). Thus, a rise of compatibility issues may occur. Some compatibility issues including, legacy databases or applications that may not support dynamic context validation will lead to prevention failure, limited API support in older systems to plug into context collectors or policy enforcement mechanisms(Jhanjhi et al, 2023).

Such a problem of compatibility will be knowingly experienced during the usage and operation of the system once installed; and this might lead to various anomalies and errors after the first week of installation. The effects are not only those leading to the extension of the development, but also that of retrofitting, or to an incomplete implementation where certain systems are left not guarded. In fighting this challenge, we shall have a system wide calibre of audit of the existing systems to be undertaken. This is to check on any possible compatibility problems that would reflect our system so that we are able to detect the problem in advance. We can then improvise and identify an appropriate means of deploying the system and we will be able to have a Centralized and smooth implementation on the actual day. Moreover, standardization of APIs and the adoption of the modular approach is also of importance because it allows flexibility and scalability, integration with third-party tools and continuous development of the architecture and addresses the requirements of the Zero Trust principles visibility, control, and isolation.

5.1.2. Financial Challenges

Another challenge would be high implementation and operational cost due to the system is having 5 separate and different system components, which involves various advanced technologies (e.g., real-time risk engines, ELK Stack, OPA integration, Flask APIs), the overall cost of the ACASF may be costly when implemented. Each system will have different needs to maintain it. An example of this is where the system requires a large database to store the company’s user data. Setting up and maintaining large databases may lead to higher cost value. Stored in the databases are the logs of access of data, the scores from the Risk Engine. Additionally, majority of the cost is contributed by the power needed to supply the ACASF. This is due to the system constantly running in the background. The system forces a constant analytical reading per data it is fed, thus requiring a steady amount of power to generate risk costs. This increases the funds needed to support the system, as it is always needed on standby. Moreover, hiring or training personnel skilled in OPA/Rego, Flask, and security analytics is one of the funds spendings, which make it an extra expense. Managing cloud-based deployments and secure configurations is one of the examples as well which could not underestimate.

5.1.3. Scalability Concerns

In the Adaptive Context-Aware Security Framework, the system is expected to be dynamic, and intelligent, and adapt all the time to the behavior of the users and contextual information. Nevertheless, as with any other adaptive and resource-consuming architecture, ACASF can possibly experience issues with scalability upon startup, and generate errors, especially within the first month of bowing down. In this initial period, we might find some performance setbacks, higher rates of errors, or lag time in decision making as the system learns and controls itself on the basis of data and behavioral patterns received by it within users.

Nevertheless, the individual parts of the ACASF, like the Context Collector, Risk Engine, Policy Decision Point and Policy Enforcement Point are designed in such a manner that they have the capacity to scale independently in response to its ability to receive data about what the user is doing. Specifically, the Risk Engine can be scaled horizontally to process an increasing amount of concurrent access evaluations, whereas caching popular policies can also save a large amount of latency at both PDP and PEP layers.

5.1.4. User Adoption

There are users that will not be able to use the new system. Since the ACASF is an invasive system, the first-time users can get uncomfortable during the process of testing out the system. That is, the transition to dynamic and context-based systems of access control such as replacing RBAC or fixed ACLs with dynamic ACLs can initially confound or frustrate users. The users will have a higher chance of continuous awareness of their choices and its potential consequences. This may cause the user to hesitate more often when working during the initial deployment of the system. Thus, the system may not be as accurate during the first phase of deployment (apty, 2025). For instance, users may push back due to frequent re-authentication like MFA attempts, access being denied for unfamiliar but legitimate situations, or gaining experiences to understand new security practices. Consequently, it will bring to efficiency disruption where slow down the productivity when users are not familiar with new environment. Not only this, but it may also lead to helpdesk load where the support is increased, lower user satisfaction and cooperation as well.

Despite these challenges, the company will not need to add or remove anything manually. The system will automatically run, not needing any human interventions. The ACASF would be easy to use, as there are no extra steps needed to contribute more to the system (Kalaria, 2024). Instead, the user would continue working as usual. The lack of explicit orders about the system may bother the employees of the company when it is first implemented.

5.2. Regulatory and Ethical Considerations

Regarding the regulatory and ethical concerns, there are several things need to be considered when introducing a system like the ACASF, particularly due to its reliance on the personal, contextual, and behavioural data taken from the user that is requesting for access to the data. The main ethical concern lies in the extent of data collection, such as geolocation, device fingerprint, IP origin, access time, and user activity patterns. Although this kind of information is important for risk-based access control, on the other hand, it may also raise issues of user privacy and surveillance. One of the main concerns of the Context Collector would be the transparency between the user and the system during the system process. Since this module gathers continuously sensitive metadata from users during access requests, but without sufficient transparency, this process may be perceived as intrusive, creating a feel of being monitored and surveilled towards the users. A common concern is the potential misuse of the data, abuse of the collected information (Gomez, 2024; Xun et al., 2025). This is one of the prime worries that occurs especially in a workplace where one might develop a sense that someone is always following his movements as well as his behaviours walking around and this can lead to stress, loss of morale or the feeling that they are not to be trusted by the system. Moreover, it poses a danger regarding the abuse or excessive use in that the gathered information may also serve other purposes other than security enforcement, including employee performance evaluation, profiling, or even disciplining. Therefore, such possibilities can be unethical in terms of purpose limitation and go against the requirements of data minimization in numerous privacy frameworks.

Although these are popular concerns, the ACASF will be able to guarantee the security of the data because the Risk Engine will give a risk score to every access based on the context obtained. Nonetheless, this may create more uneasiness in the minds of workers at the company because it makes them feel that they are being stalked wherever they go. Thus, the architecture should be in line with existing data protection regulations like the ISO/IEC 27001 which stress on the importance of control information security and ability to audit to allow responsible use of sensitive information.

6. Evaluation and Discussion

Access Control is a significant defense model that deployed to satisfy the need of modern cybersecurity and legal compliance with data privacy. According to Nieles et al. (2017), AC is defined as: An array of automatic procedures or processes that grant access to a specific location or information being controlled, in combination with pre-established policies and rules. The main purpose of AC is to prevent unauthorized users and system from accessing secured information (Golightly et al., 2023; Ying et al., 2024). According to what has been mentioned above, among the traditional access control systems, we have a discretionary access model (DAC), mandatory access model (MAC), role-based access model (RBAC), and an attribute-based access model (ABAC). This is where we shall be talking about our proposed solution, the Adaptive Context-Aware Security Framework along with the two typical and standard baseline traditional access control models, which are the RBAC and the ABAC.

6.1. ACASF Overview

As stated above, ACASF can flexibly make access decisions based on real-time contextual information, such as access time, geographic location, and device used. It combines the user's behaviour pattern and the current environment, dynamically adjusts the permissions and policies, and is more suitable for the actual situation. The system also introduces risk scoring and anomaly detection mechanism, which can find potential risks in time and improve the overall security response speed. At the same time, it supports more fine-grained access control and combines multi-factor authentication (MFA) to enhance security. The system also has built-in audit and monitoring functions of continuously track access behaviour via ELK stack and help to optimize policies and manage risks through the Open Policy Agent (OPA). In short, it is an intelligent, flexible and adaptable security framework, where aligns with Zero Trust principles which no user or device is inherently trusted, and each access request must be evaluated based on dynamic risk scoring, anomaly detection, and contextual awareness.

6.2. Comparison with Role-Based Access Control (RBAC)

RBAC is an access control model where permissions are assigned based on user roles within an organization (Ferraiolo & Kuhn, 1992; Ahmed et al., 2022). A role is typically tied to a job function such as admin, manager, employee where each role has a specific and predefined set of access rights. In other words, users inherit permissions by being assigned to one or more roles. Hence, RBAC is stable and easy to understand. By assigning roles to different types of users, it makes permission management easier, clearer, and more organized. Take an e-commerce platform for example, the two roles like buyer and seller are well separated. Such separation makes the body of the whole system more obvious as well. The advantages to the buyers when it comes to RBAC are to ensure that all users are being limited to what they require, like their account details, their order history, their shipping details etc. This discourages any misuse or abuse that could happen to use it where it is not to be used and minimizes chances of data leakage. Under the seller component, the system will only grant the access they require including management of products, order processing, and inventory access. Others and they do not concern any of the content, and the system will automatically help them block, also acting in a protective role. All in all, this configuration does not only increase the safeness of the platform but also ensures the permission management process is more proficient and comprehensible. However, RBAC is not flexible in a dynamic or contemporary environment where change on user access may be required most of the time. This is because it does not consider contextual factors like time, location, or device status, and all access decisions are made statically at login. For example, when an employee's responsibilities change frequently, or someone temporarily needs permissions beyond the scope of their original role, RBAC's fixed role setting is not very flexible. Moreover, it is not able to dynamically adjust the permissions according to the actual situation such as time and place and lacks the context-aware ability.

In large organizations, RBAC often suffers from a problem called "role explosion." This means that as more people and responsibilities become more detailed, more roles are divided, and as a result, authority management becomes more complex and difficult to maintain, which affects the efficiency of the system (Elliott & Knight, n.d; Attaullah et al., 2022). For example, in multinational companies, different departments and different regions may have different requirements for authority. Relying on RBAC alone is not flexible enough to handle frequent responsibility changes or temporary authorization requests. Moreover, RBAC as a concept is less capable of adjusting itself dynamically to reality, which is expressed through changing shifts of employees. In the event of permissions that do not automatically adjust on a time-basis or geographical-basis, then this can result in security concerns or cause the employee to not be able to perform their job due to lack of enough permissions. Due to this reason, RBAC is not always suitable to describe more complex and fine-grained organizations. Although it is handy in the context of various use cases, it should be known to have limitations in the case of organizations, which require greater flexibility in accommodating their needs regarding permission assignment. RBAC is sometimes not fine, usually using some relatively broad roles to assign permissions, which is easy to give permissions to too many or too few cases. To illustrate, one can give such a case as an interdisciplinary research project, where there might be nothing wrong with the word researcher, but in fact the data and the instruments, utilized by biologists and chemists, can be totally different. Consequently, certain individuals might end up viewing sensitive information they are not supposed to, whereas individuals, who require certain authorizations, are limited. These issues demonstrate that RBAC is slightly not sufficient to handle professional and complicated surroundings. It is due to this reason that more flexible, fine-grained access control that lets the permissions be modified as required are needed, examples include context-aware models.

In comparison, our proposed solution framework designed with this function, offering significant improvements. As mentioned, ACASF able to evaluates access requests dynamically based on real-time context such as fingerprint, IP origin, geolocation, and behavioural patterns (see 4.2.1). It also integrates a Risk Engine where scores each request and determine whether it should be allowed, denied, or required MFA, escalating access requirements based on current risk. Unlike RBAC, which only provides one-time validation based on static roles, ACASF continuously monitors users’ access behaviour and adapts to change instantly. By this, it avoids role explosion issues by using centralized, policy logic through tools like Open Policy Agent, making the system more scalable and resilient.

6.3. Comparison with Attribute-Based Access Control (ABAC)

ABAC is particularly good at handling some of the more variable access requirements. It considers many aspects, such as who the user is, what the resource is, the current environmental conditions, and so on, to adjust the permissions (Hu et al., 2014; Azeem et al., 2021). By taking into consideration all the dynamic properties of a user, location, and the sensitivity of the data, unlike RBAC, ABAC allows fine-grained control. As an example, a surgeon might require getting the data on a patient in a hospital during surgery. ABAC can give him a temporary permission according to the actual situation, and the permission will be automatically withdrawn after the operation. This mechanism not only guarantees security, but also does not delay important operations, and improves work efficiency. Similarly, in finance, ABAC can enforce transaction approvals only during business hours and from verified corporate devices, enhancing both practicality and security.

Although Attribute-based access Control (ABAC) is powerful, it also brings many technical problems in practical applications, especially in the design and management of policies. As the number of attributes increases, policy definitions become harder to manage, prone to conflicts and difficult to manage, especially across massive systems with varying attribute standards. In the healthcare industry, for example, accessing a patient's records may require consideration of the doctor's position, the sensitivity level of the patient's data, the period of access, and even the location of the doctor at the time. This seems reasonable, but it makes policies hard to write and easy to break. Furthermore, same as RBAC, ABAC lacks built-in mechanisms for real-time risk evaluation or anomaly detection. It statically evaluates predefined rules, making it less responsive to emerging threats or behavioural deviations. Moreover, deploying ABAC in a diverse and rapidly changing environment requires not only technical preparation, but also strategic planning, and a clear set of ideas and methodologies, due to it has to deal with attribute mapping, data format conversion, policy language parsing, and so forth, when implemented into a variety of systems. In short, ABAC itself faces the problem of inconsistent syntax and attribute definition.

In contrast, our proposed architecture enhances ABAC’s foundation by integrating real-time contextual analysis, dynamic risk scoring, and anomaly detection into the decision process. ACASF not only considers environmental attributes but also actively analyses user behaviour and contextual trends, where allowing it to detect and respond to suspicious behaviour immediately. Additionally, while ABAC has the characteristics of resource-intensive due to constant attribute evaluation and complex rule-matching, ACASF optimizes enforcement through modular components like the Risk Engine and Open Policy Agent, which make it able to make decision efficiently and scalable. Therefore, even though ABAC provides a flexible alternative to static models, ACASF offers a more robust, adaptive, and secure approach suitable for high-risk, dynamic environments like modern big data systems.

7. Conclusions

In this report, we explored the ongoing and critical security challenge of static and not enough access control in big data systems. We found out that, since organizations increasingly rely on scalable cloud platforms and distributed data infrastructure, the limitations of traditional access models such as Role-Based Access Control and Attribute-Based Access Control have become more apparent. These models, while effective in more static environments, however, lack of adaptability, context sensitivity, and real-time threat response capabilities required to defend against today’s complex cyber threats.

This problem puts sensitive company data at risk. We studied real cases like the 2024 Snowflake data breach and the Capital One incident. These cases showed how mismanagement of access controls can lead to severe consequences. Both cases revealed a pattern of common weakness, including long-term reliance on static credentials, lack of enforced multi-factor authentication (MFA), over-privileged user roles, and insufficient behavioural monitoring. In the Snowflake case, because of the absence of MFA security approach and ineffective access governance, attackers are given the opportunity to exploit stolen static credentials and bypass security layers. Similarly, the Capital One breach indicated the risk of configuration flaws and lack of real-time anomaly detection in cloud-native environments. These real-world examples underlie the urgent need for a more dynamic, risk-aware, and context-sensitive model to access control, as weak password management, no multi-factor authentication, and limited checking systems can be used by attackers to get unauthorized access.

To address these risks, we suggested the Adaptive Context-Aware Security Framework (ACASF). This is an advanced security architecture designed to overcome the limitations of static models, where built upon Zero Trust Architecture. ACASF incorporates real-time contextual analysis, risk-based decisions, and continuous policy evaluation through its modular components, including a Context Collector, Risk Engine, Policy Decision Point, Policy Enforcement Point, and an integrated Audit and Monitoring System. This framework does not rely solely on predefined roles or static attributes sets, instead, it dynamically evaluates access requests based on multiple contextual signals such as geolocation, device footprint, IP origin, time of access, and user behaviour patterns. We utilize tools like OPA for flexible policy enforcement, GEOIP2 for geolocation checks and others to ensure ACASF delivers a scalable and modular security posture.

In conclusion, this architecture we proposed, ACASF, represents a forward-thinking solution to modern access control challenges. Not only aligning with current best practices in cybersecurity, but it also addressing the specific operational needs for large-scale, data-driven systems. We believe by adopting a dynamic, context-aware approach to data protection, instead of static credentials and rigid access policies, organizations can strengthen their defense against unauthorized access and insider threats.

Appendix A. Technology Stack Table

| Component |

Tool/ Framework |

Description |

| Context Collector |

Flask, GeoIP2, Device Detector |

Gathers contextual metadata |

| Risk Engine |

Python, Isolation Forest |

Calculates risk score |

| PDP |

Open Policy Agent |

Evaluates access policies |

| PEP |

Flask Middleware, Redis |

Enforces access decisions |

| Audit and Monitoring System |

ELK Stack |

Logs and visualizes events |

Appendix B. Case Study Summary Table

| Case |

Date |

Cause |

Security Failures |

Proposed Mitigation |

| Snowflake |

2024 |

Stolen credentials |

No MFA, static credentials |

Risk Engine, Context-aware decisions |

| Capital One |

2019 |

SSRF to get IAM tokens |

No anomaly detection, static IAM |

Dynamic access control, real-time monitoring |

Appendix C. Glossary of Terms

| ACASF |

Adaptive Context-Awareness Security Framework |

| OPA |

Open Policy Agent |

| ELK Stack |

Elasticsearch, Logstash, Kibana |

| MFA |

Multi-Factor Authentication |

| RBAC |

Role-Based Access Control |

| ABAC |

Attribute-Based Access Control |

Appendix D. Reference Frameworks and Visual Inspirations

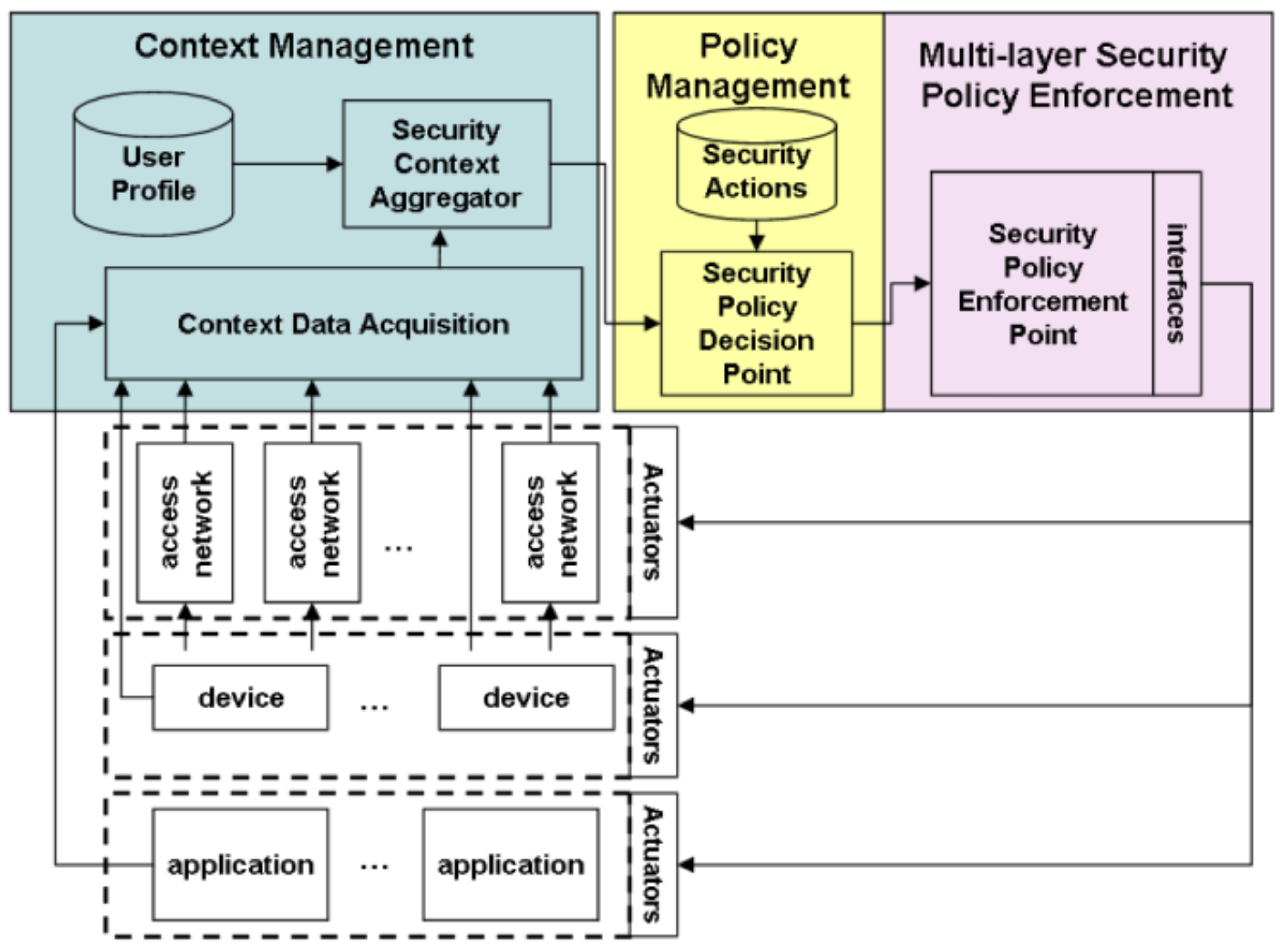

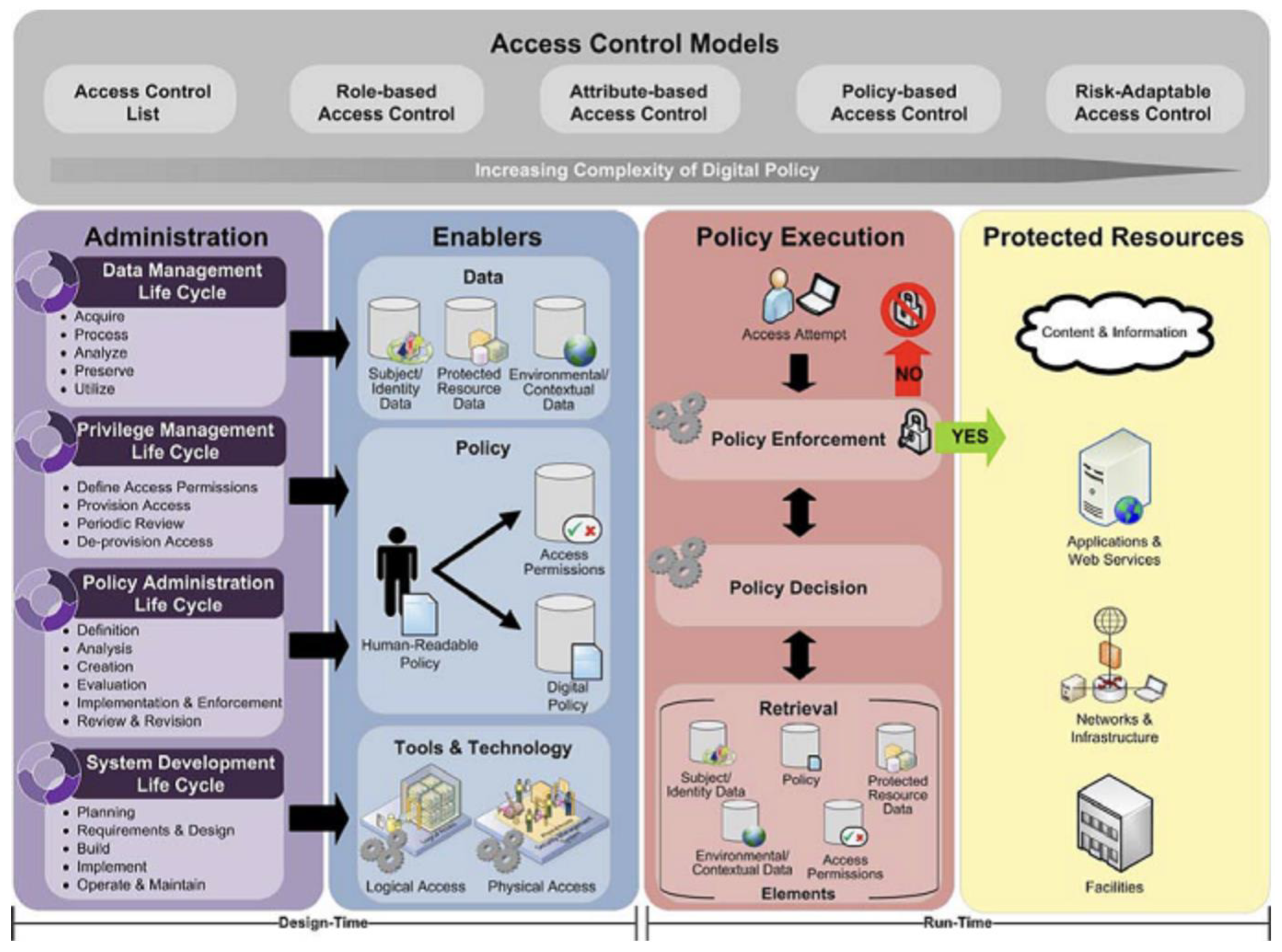

Figure D1.

Reference Model for ACASF Architecture.

Figure D1.

Reference Model for ACASF Architecture.

Figure D2.

Reference Model for ACASF Architecture.

Figure D2.

Reference Model for ACASF Architecture.

Figure D1, D2 Conceptual architecture of basic access control framework, illustrating various mechanisms including data lifecycle, policy enablers, decision making, and enforcement, as well as a multi-layered security enforcement architecture using context data acquisition and policy decision points. This reference inspired the structural layout of our ACASF architecture.

Figure D3.

Rego Policy Example.

Figure D3.

Rego Policy Example.

Figure D3 A Rego Policy Example, defines a rule that denies access (default allow := false) if any violation exists. It flags violations when public-facing servers use insecure protocols such as http or telnet. This policy is an example of how security rules can be enforced in ACASF using OPA to ensure protocol compliance and reduce risk surface.

8. Cybersecurity Awareness Video

References

- Ahmed, Q. W. , Garg, S., Rai, A., Ramachandran, M., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Masud, M., & Baz, M. (2022). AI-Based Resource Allocation Techniques in Wireless Sensor Internet of Things Networks in Energy Efficiency with Data Optimization. Electronics, 11, 13, 2071. [CrossRef]

- Alsaqour, R. , Majrashi, A., Alreedi, M., Alomar, K., & Abdelhaq, M. (2021). Defense in Depth: Multilayer of security. International Journal of Communication Networks and Information Security (IJCNIS), 13, 2. [CrossRef]

- apty. (24 February, 2025). Top 7 Digital Adoption Challenges & How to Solve Them (2025). Retrieved from apty: https://apty.ai/digital-adoption/digital-adoption-challenges/.

- Attaullah, M. , Ali, M., Almufareh, M. F., Ahmad, M., Hussain, L., Jhanjhi, N., & Humayun, M. (2022). Initial stage COVID-19 detection system based on patients’ symptoms and chest X-Ray images. Applied Artificial Intelligence, 36, 1. [CrossRef]

- Authentication methods at Google. (n.d.). Google Cloud. https://cloud.google.

- AWS. (2023). IAM Best Practices.https://docs.aws.amazon.com/IAM/latest/UserGuide/best-practices.html.

- AWS. (2023). Using Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) in AWS.https://docs.aws.amazon.com/IAM/latest/UserGuide/id_credentials_mfa.html.

- Azeem, M. , Ullah, A., Ashraf, H., Jhanjhi, N., Humayun, M., Aljahdali, S., & Tabbakh, T. A. (2021). FOG-Oriented secure and lightweight data aggregation in IOMT. IEEE Access, 9, 111072–111082. [CrossRef]

- Bleeping Computer. (2024). Snowflake account hacks linked to Santander, Ticketmaster breaches. https://www.bleepingcomputer.com/news/security/snowflake-account-hacks-linked-to-santander-ticketmaster-breaches/.

- Brohi, S. N. , Jhanjhi, N., Brohi, N. N., & Brohi, M. N. (2020). Key Applications of State-of-the-Art Technologies to Mitigate and Eliminate COVID-19.pdf. Authorea Preprints. [CrossRef]

- CISA. (2023). Multi-Factor Authentication | CISA. Www.cisa.gov. https://www.cisa.gov/mfa.

- Elastic. (2025). Elastic Stack: Elasticsearch, Kibana, Beats & Logstash. Elastic. https://www.elastic.co/elastic-stack/.

- Elliott, A. , & Knight, G. (n.d.). Role Explosion: Acknowledging the Problem. Retrieved June 25, 2025, from https://knight.segfaults.net/papers/20100502%20-%20Aaron%20Elliott%20-%20WOLRDCOMP%202010%20Paper.pdf.

- Golightly, L. , Modesti, P., Garcia, R., & Chang, V. (2023). Securing Distributed Systems: A Survey on Access Control Techniques for Cloud, Blockchain, IoT and SDN. Cyber Security and Applications, 1, 100015. [CrossRef]

- Gomez, A. (25 April, 2024). Cybersecurity Ethics: Everything You Need To Know. Retrieved from OLLU: https://www.ollusa.edu/blog/cybersecurity-ethics.html.

- Hanif, M. , Ashraf, H., Jalil, Z., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Humayun, M., Saeed, S., & Almuhaideb, A. M. (2022). AI-Based wormhole attack detection techniques in wireless sensor networks. Electronics, 11, 15, 2324. [CrossRef]

- Hu, V. C. , Ferraiolo, D., Kuhn, R., Schnitzer, A., Sandlin, K., Miller, R., & Scarfone, K. (2014). Guide to Attribute Based Access Control (ABAC) Definition and Considerations. Guide to Attribute Based Access Control (ABAC) Definition and Considerations. [CrossRef]

- Humayun, M. , Jhanjhi, N. Z., Niazi, M., Amsaad, F., & Masood, I. (2022). Securing Drug Distribution Systems from Tampering Using Blockchain. Electronics 11(8), 1195. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, K. , Rahmatyar, A. R., Riskhan, B., Sheikh, M. a. U., & Sindiramutty, S. R. (2024). Threats and Vulnerabilities of Wireless Networks in the Internet of Things (IoT). 2024 IEEE 1st Karachi Section Humanitarian Technology Conference (KHI-HTC), 2, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Introduction | Open Policy Agent. (2025). Openpolicyagent.org. https://www.openpolicyagent.org/docs.

- Jabeen, T. , Jabeen, I., Ashraf, H., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Yassine, A., & Hossain, M. S. (2023). An intelligent healthcare system using IoT in wireless sensor network. Sensors 23(11), 5055. [CrossRef]

- Jun, A. Y. M. , Jinu, B. A., Seng, L. K., Maharaiq, M. H. F. B. Z., Khongsuwan, W., Junn, B. T. K., Hao, A. a. W., & Sindiramutty, S. R. (2024). Exploring the Impact of Crypto-Ransomware on Critical Industries: Case Studies and Solutions. Preprint.org. [CrossRef]

- Kalaria, R. (8 July, 2024). Adaptive context-aware access control for IoT environments leveraging fog computing. Retrieved from Springer: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10207-024-00866-4.

- Gill, S. H. , Razzaq, M. A., Ahmad, M., Almansour, F. M., Haq, I. U., Jhanjhi, N. Z.,... & Masud, M. (2022). Security and privacy aspects of cloud computing: a smart campus case study. Intelligent Automation & Soft Computing, 31, 1, 117–128.

- 9.

- Khan, S. , Kabanov, I., Hua, Y., & Madnick, S. (2022). A systematic analysis of the Capital One data breach: Critical lessons learned, ACM Transactions on Privacy and Security, 26(1), Article 3. [CrossRef]

- Kiyani, F. F. , Hamid, B., Humayun, M., Sindiramutty, S. R. a. L., & Chowdhury, S. (2024). Discovery of Influential Publications Using Research Article’s Usage Context. 2024 International Conference on Emerging Trends in Networks and Computer Communications (ETNCC), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Kosmos. (2024). Understanding the Snowflake Data Breach and Its Implications. Retrieved June 9, 2025, from https://www.1kosmos.com/authentication/understanding-the-snowflake-data-breach-and-its-implications/.

- Krishnan, S. , Thangaveloo, R., Rahman, S. B. A., & Sindiramutty, S. R. (2021). Smart Ambulance Traffic Control system. Trends in Undergraduate Research 4(1), c28–34. [CrossRef]

- Kunal Relan, & Springerlink (Online Service. (2019). Building REST APIs with Flask : Create Python Web Services with MySQL. Apress.

- Linqiang, Y. , Sindiramutty, S. R. a. L., Ashraf, H., Muzammal, S. M., Balakrishnan, S. a. P., Gupta, S., & Kavita, N. (2024). Intelligent Household Waste Classification System Based on Machine Learning. 2024 International Conference on Emerging Trends in Networks and Computer Communications (ETNCC), 760–768. [CrossRef]

- Manchuri, A. , Kakera, A., Saleh, A., & Raja, S. (2024). pplication of Supervised Machine Learning Models in Biodiesel Production Research - A Short Review. Borneo Journal of Sciences and Technology. [CrossRef]

- Mandiant. (2024, ). UNC5537 Targets Snowflake Customer Instances for Data Theft and Extortion. Retrieved fromhttps://cloud.google.com/blog/topics/threat-intelligence/unc5537-snowflake-data-theft-extortion.

- Muscat, M. (2019, July 31). How an SSRF misconfiguration led to a leak of 100 million financial records. Acunetix.https://www.acunetix.com/blog/web-security-zone/ssrf-misconfiguration-leak-one-hundred-million-financial-records/?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Aldughayfiq, B. , Ashfaq, F., Jhanjhi, N. Z., & Humayun, M. (2023, April). Yolo-based deep learning model for pressure ulcer detection and classification. In Healthcare (Vol. 11, No. 9, p. 1222). MDPI.

- Muzammal, S. M. , Murugesan, R. K., Jhanjhi, N. Z., & Jung, L. T. (2020). SMTrust: Proposing Trust-Based Secure Routing Protocol for RPL Attacks for IoT Applications. 2020 International Conference on Computational Intelligence (ICCI), 305–310. [CrossRef]

- Nieles, M. , Dempsey, K., & Pillitteri, V. Y. (2017). An introduction to information security. An Introduction to Information Security 1(1), 81. [CrossRef]

- Ravichandran, N. , Tewaraja, T., Rajasegaran, V., Kumar, S. S., Gunasekar, S. K. L., & Sindiramutty, S. R. (2024). Comprehensive Review Analysis and Countermeasures for Cybersecurity Threats: DDoS, Ransomware, and Trojan Horse Attacks. preprint.org. [CrossRef]

- Ridha Khedri, Jones, O., & Alabbad, M. (2017). Defense in Depth Formulation and Usage in Dynamic Access Control. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 253–274. [CrossRef]

- Riza, A. Z. B. M. , Jennsen, L., Anggani, P., Rafeen, A. I., Ruth, P. N. J., Sookun, D., Sookun, V., Yusri, N. a. Z. B. M., Sern, L. J., Luximon, L., Omer, M. L., & Sindiramutty, S. R. (2025). Leveraging Machine Learning and AI to Combat Modern Cyber Threats. Preprints.org. [CrossRef]

- Rose, S. , Borchert, O., Mitchell, S., & Connelly, S. (2020). Zero trust architecture. NIST Special Publication 800-207, 800-207. [CrossRef]

- Saeed, S. , Abdullah, A., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Naqvi, M., & Nayyar, A. (2022). New techniques for efficiently k-NN algorithm for brain tumor detection. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 81, 13, 18595–18616. [CrossRef]

- ScienceDirect. (2024). Big Data System. Retrieved June 9, 2025, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/computer-science/big-data-system.

- Seng, Y. J. , Cen, T. Y., Raslan, M. a. H. B. M., Subramaniam, M. R., Xin, L. Y., Kin, S. J., Long, M. S., & Sindiramutty, S. R. (2024). In-Depth Analysis and Countermeasures for Ransomware Attacks: Case Studies and Recommendations. Preprints.org. [CrossRef]

- Shah, I. A. , Jhanjhi, N. Z., & Laraib, A. (2022). Cybersecurity and blockchain usage in contemporary business. In Advances in information security, privacy, and ethics book series (pp. 49–64). [CrossRef]

- Sindiramutty, S. R. , Jhanjhi, N. Z., Tan, C. E., Tee, W. J., Lau, S. P., Jazri, H., Ray, S. K., & Zaheer, M. A. (2024). IoT and AI-Based Smart Solutions for the Agriculture Industry. In Advances in computational intelligence and robotics book series (pp. 317–351). [CrossRef]

- Sindiramutty, S. R. , Jhanjhi, N. Z., Tan, C. E., Yun, K. J., Manchuri, A. R., Ashraf, H., Murugesan, R. K., Tee, W. J., & Hussain, M. (2024). Data security and privacy concerns in drone operations. In Advances in information security, privacy, and ethics book series (pp. 236–290). [CrossRef]

- Sindiramutty, S. R. , Jhanjhi, N., Tan, C. E., Lau, S. P., Muniandy, L., Gharib, A. H., Ashraf, H., & Murugesan, R. K. (2024). Industry 4.0. In Advances in logistics, operations, and management science book series (pp. 342–405). [CrossRef]

- Sindiramutty, S. R. , Prabagaran, K. R. V., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Ghazanfar, M. A., Malik, N. A., & Soomro, T. R. (2024). Security Considerations in Generative AI for web Applications. In Advances in information security, privacy, and ethics book series (pp. 281–332). [CrossRef]

- Sindiramutty, S. R. , Prabagaran, K. R. V., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Murugesan, R. K., Brohi, S. N., & Masud, M. (2024). Generative AI in network security and intrusion detection. In Advances in information security, privacy, and ethics book series (pp. 77–124). [CrossRef]

- Sindiramutty, S. R. , Tan, C. E., & Wei, G. W. (2024). Eyes in the sky. In Advances in information security, privacy, and ethics book series (pp. 405–451). [CrossRef]

- Waheed, A. , Seegolam, B., Jowaheer, M. F., Sze, C. L. X., Hua, E. T. F., & Sindiramutty, S. R. (2024). Zero-Day Exploits in Cybersecurity: Case Studies and Countermeasure. Preprints.org. [CrossRef]

- Watkins, S. G. (2022). Iso/Iec 27001: 2022: An Introduction to Information Security and the ISMS Standard. It Governance Limited.

- Weiqi, X. , Hooi, S. T. C., Sindiramutty, S. R. a. L., Asirvatham, D. a. L., Kumar, D., & Verma, S. (2024). Surface Anomaly Detection Using Machine Learning Technique. 2024 International Conference on Emerging Trends in Networks and Computer Communications (ETNCC), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Wen, B. O. T. , Syahriza, N., Xian, N. C. W., Wei, N. G., Shen, T. Z., Hin, Y. Z., Sindiramutty, S. R., & Nicole, T. Y. F. (2023). Detecting cyber threats with a Graph-Based NIDPS. In Advances in logistics, operations, and management science book series (pp. 36–74). [CrossRef]

- Working with JSON - Learn web development | MDN. (2024, December 19). MDN Web Docs. https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Learn_web_development/Core/Scripting/JSON.

- Xun, A. T. , En, L. a. Z., Shen, L. T., Xin, A. N., Soon, W. H., Jun, W. Z., Ramachandra, H., Xinghao, G., Khant, N. M., Weitao, F., & Sindiramutty, S. R. (2025). Building Trust in Cloud Computing:Strategies for Resilient Security. Preprints.org. [CrossRef]

- Ying, X. , Murugesan, R. K., Sindiramutty, S. R., Wei, G. W., Balakrishnan, S., Kumar, D., & Verma, S. (2024). Scene Text Recognition using Deep Learning Techniques. 024 International Conference on Emerging Trends in Networks and Computer Communications (ETNCC), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Jhanjhi, N. (2024). Comparative analysis of frequent pattern mining algorithms on healthcare data. In 2024 IEEE 9th International Conference on Engineering Technologies and Applied Sciences (ICETAS) (pp. 1-10). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Jhanjhi, N. Z. (2025). Investigating the influence of loss functions on the performance and interpretability of machine learning models. In S. Pal & Á. Rocha (Eds.), Proceedings of 4th International Conference on Mathematical Modeling and Computational Science. ICMMCS 2025. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol 1399 (pp. 100-110). Springer. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).