Submitted:

31 August 2025

Posted:

01 September 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

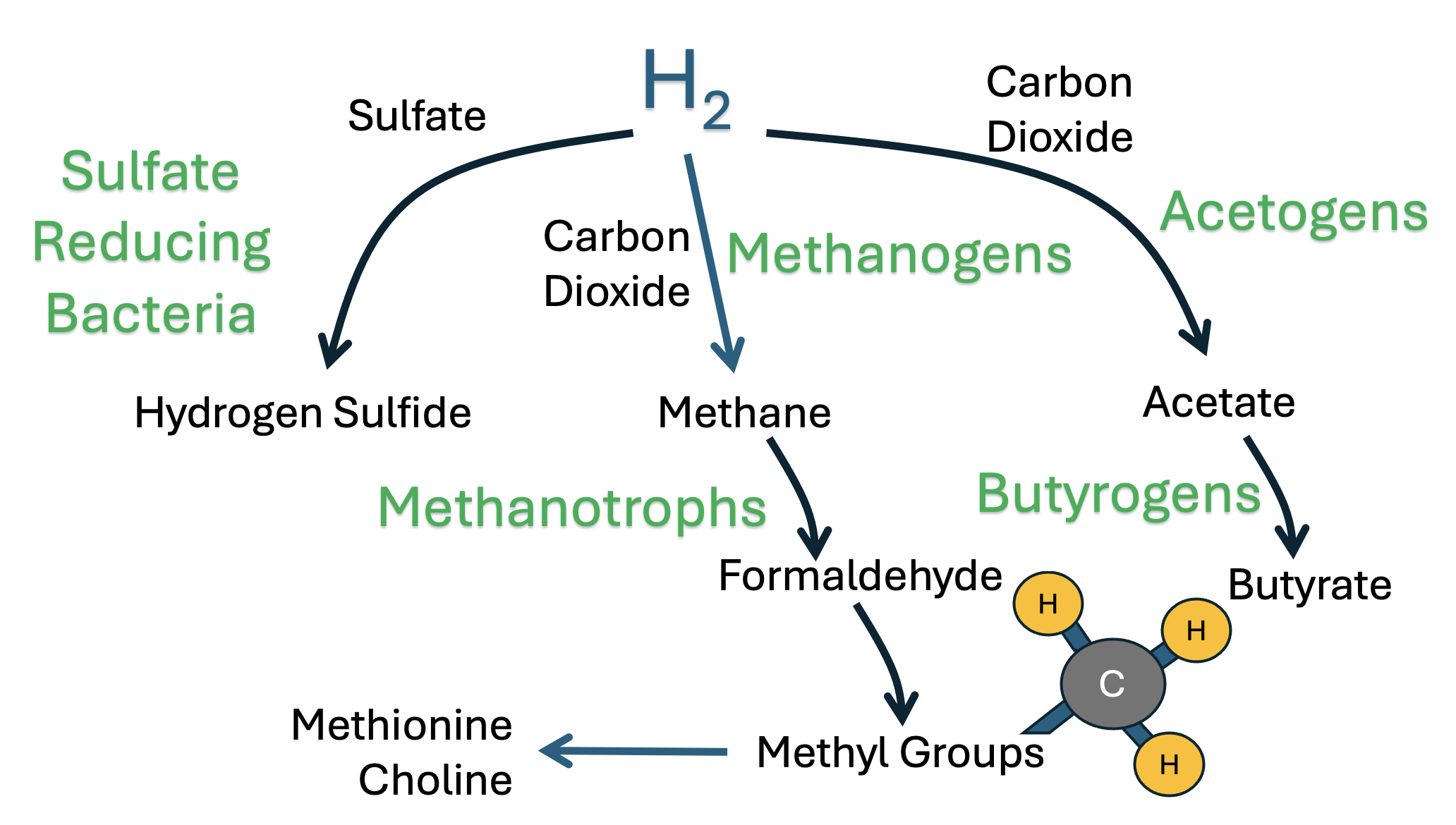

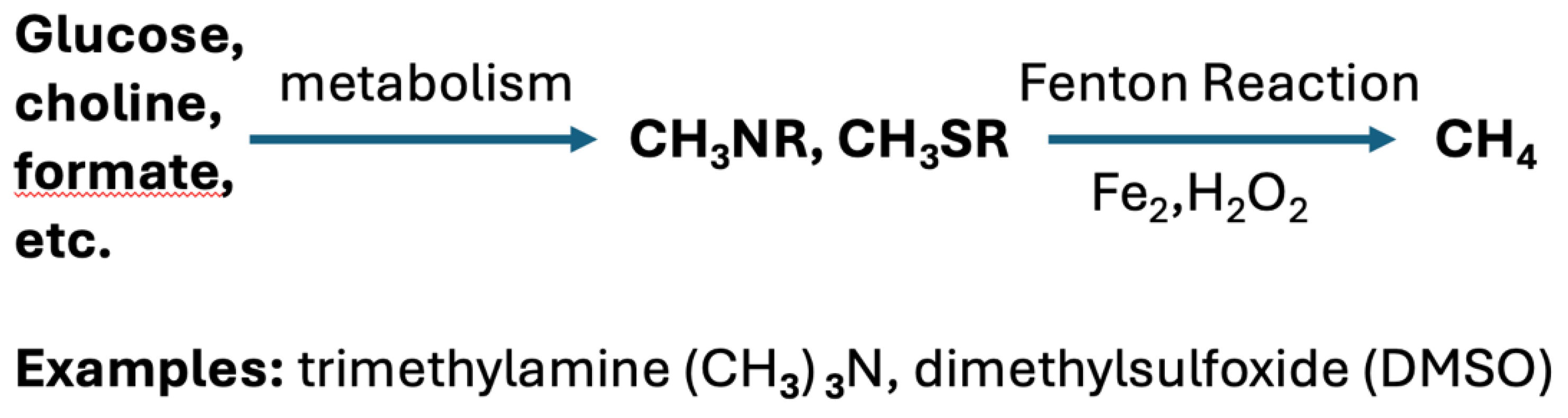

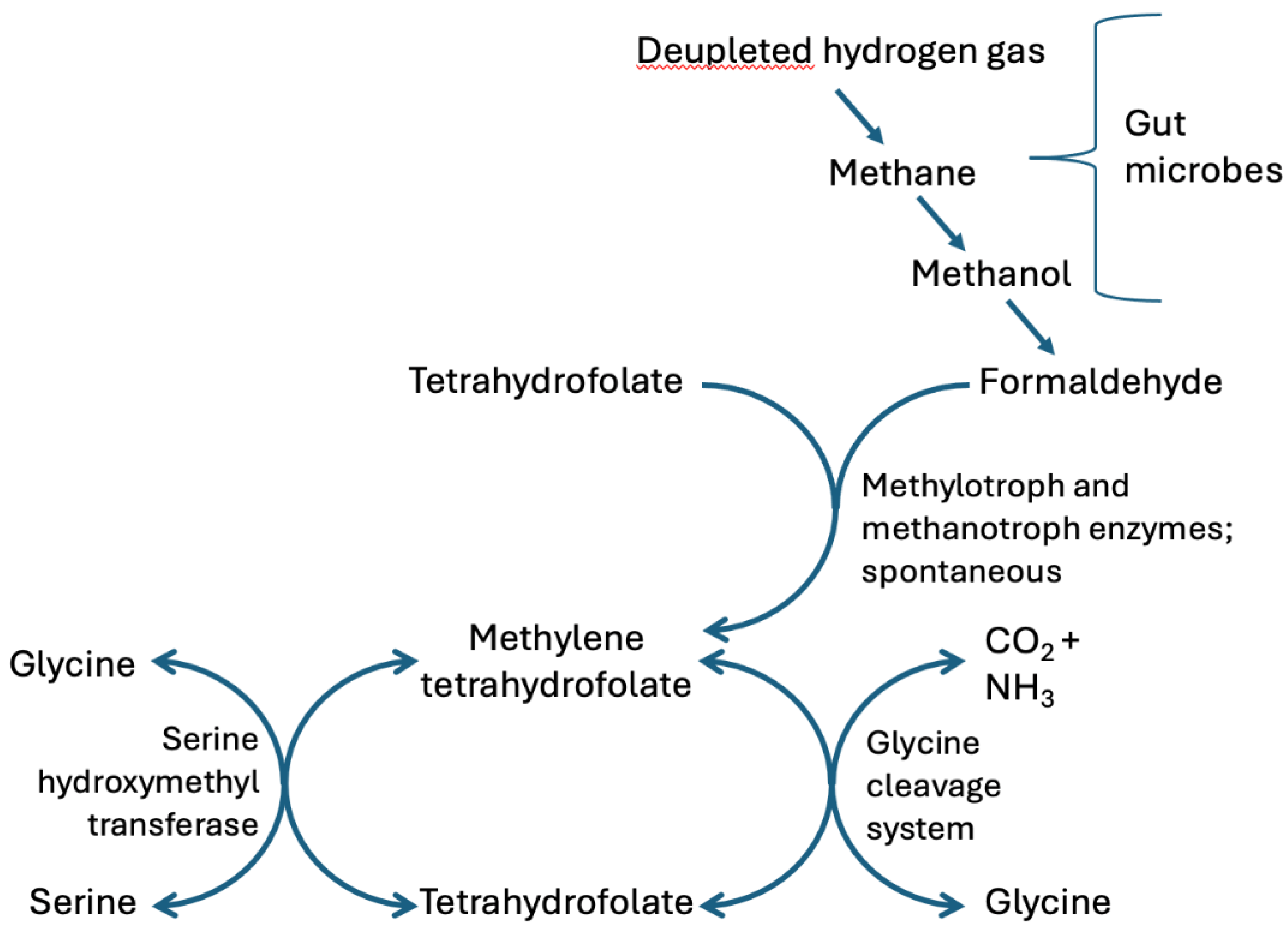

2. Hydrogen Gas Recycling by Gut Microbes: A Critical Role for Formaldehyde

2.1. Production of Methane Gas by Archaea and the Recycling Between Methane and CO2

2.2. Synthesis of Deupleted Hydrogen Gas Through Fermentation

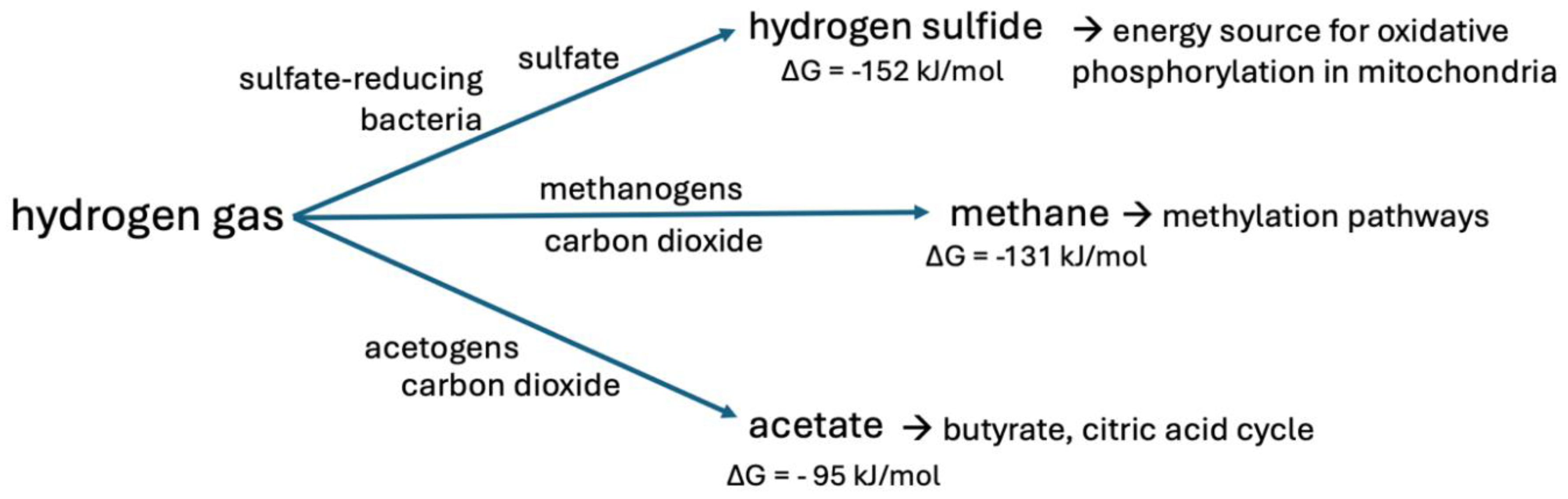

2.3. Other Pathways Besides Methane Production for H2 Consumption

2.4. An Important Role for Methylotrophs

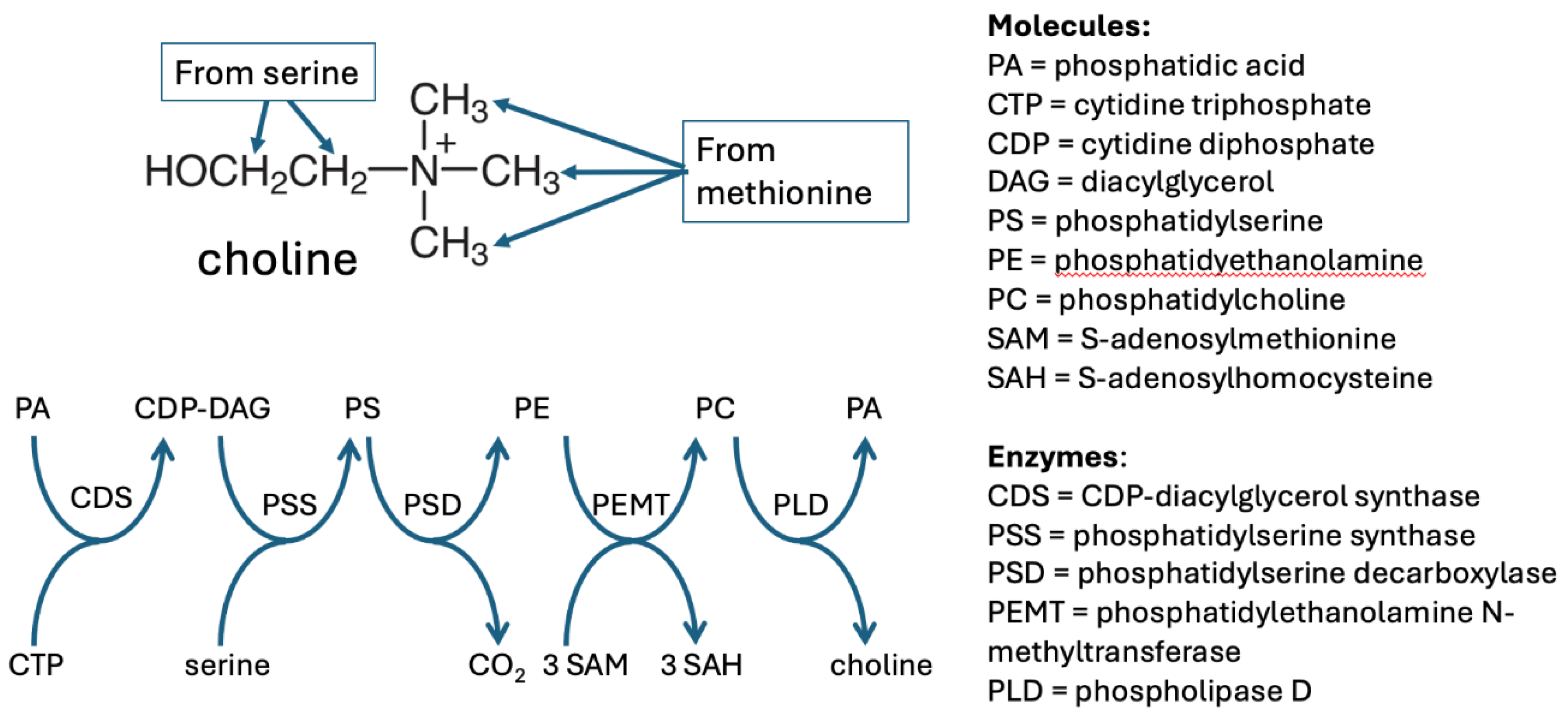

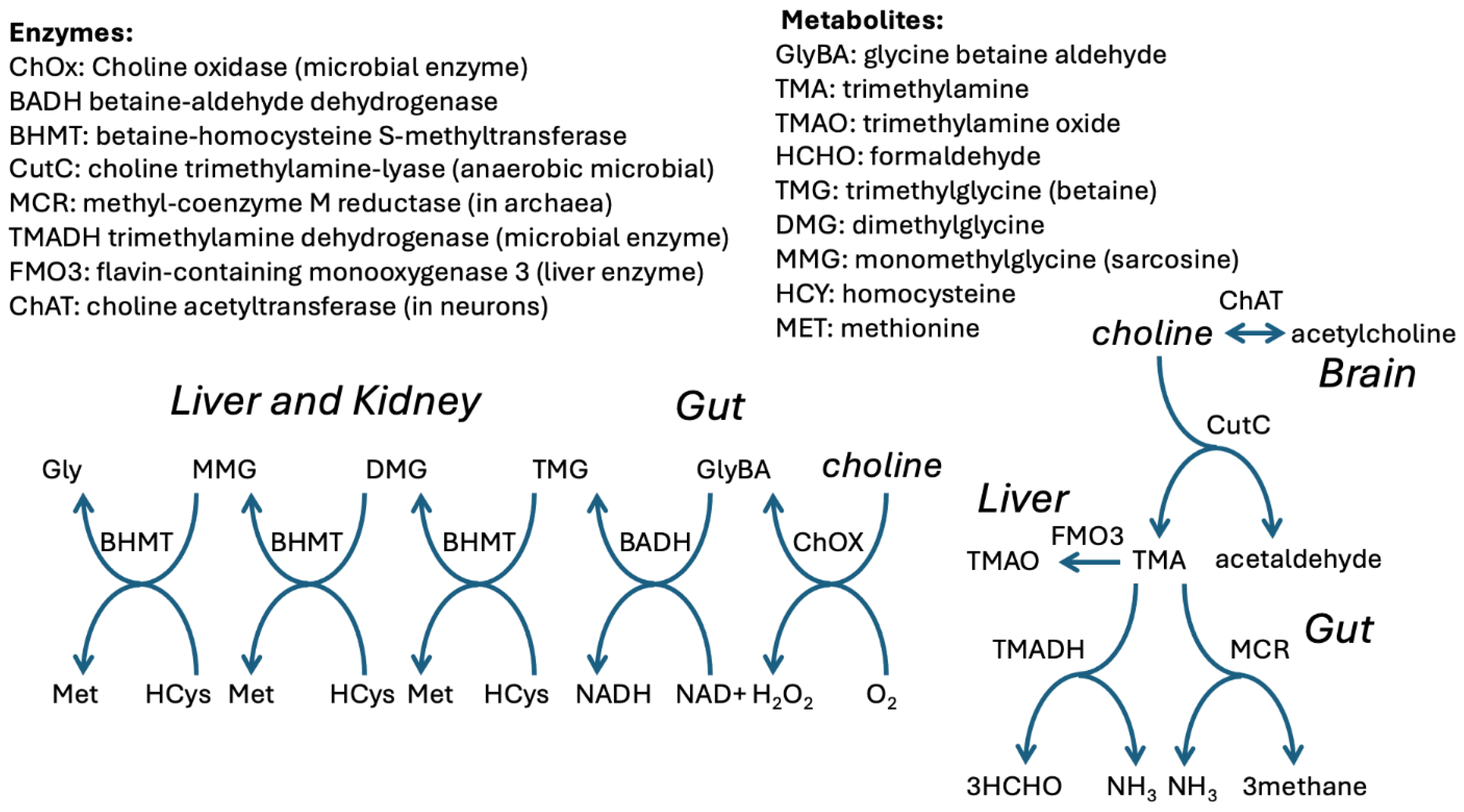

3. Choline Plays a Central Role in Methylation Pathways

3.1. Choline Synthesis

3.2. Choline Metabolism

3.3. Dietary Versus Synthetic Supplemental Choline

3.4. The Pathogenic Mechanisms of TMAO that Induce Tissue Damage and Disease

4. Metabolism of Methyl Groups Supports Mitochondrial Health

4.1. Histone Methylation and Demethylation

4.2. DNA Methylation and Demethylation

4.3. Methionine Metabolism to Methanethiol and Beyond

4.4. Dietary Methionine Restriction and Longevity

5. Does Acetylcholine Provide Acetate to Synaptic Mitochondria?

6. Benefits of a High Fiber Diet

7. Butyrate Is a Universal Protective/Essential Nutrient for the Human Organism

8. Creatinine Is a Waste Product, but Is It Really?

8.1. Creatine Synthesis Is a Major Pathway by Which One-Carbon Units Are Lost

8.2. Can the Imidazolidinone Ring in Creatinine Sequester Deuterium?

9. Conclusions

Disclosure of Interest

Funding

References

- Fukuda K, Straus SE, Hickie I, Sharpe MC, Dobbins JG, Komaroff A. The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1994 Dec 15;121(12):953-9. [CrossRef]

- Wood E, Hall KH, Tate W. Role of mitochondria, oxidative stress and the response to antioxidants in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: A possible approach to SARS-CoV-2 ’long-haulers’? Chronic Dis Transl Med. 2021 Mar;7(1):14-26. [CrossRef]

- Syed AM, Karius AK, Ma J, Wang P-Y, Hwang PM. Mitochondrial dysfunction in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Physiology 2025; 40: 319-328. [CrossRef]

- Molnar T, Lehoczki A, Fekete M, Varnai R, Zavori L, Erdo-Bonyar S, Simon D, Berki T, Csecsei P, Ezer E. Mitochondrial dysfunction in long COVID: mechanisms, consequences, and potential therapeutic approaches. Geroscience. 2024 Oct;46(5):5267-5286. [CrossRef]

- Crost EH, Tailford LE, Monestier M, Swarbreck D, Henrissat B, Crossman LC, and Juge N. (). The mucin-degradation strategy of Ruminococcus gnavus: the importance of intramolecular trans-sialidases. Gut Microbes 7, 302312. 10.1080/19490976.2016.1186334.

- Guo C, Che X, Briese T, Ranjan A, Allicock O, Yates RA, Cheng A, March D, Hornig M, Komaroff AL, Levine S, Bateman L, Vernon SD, Klimas NG, Montoya JG, Peterson DL, Lipkin WI, Williams BL. Deficient butyrate-producing capacity in the gut microbiome is associated with bacterial network disturbances and fatigue symptoms in ME/CFS. Cell Host Microbe. 2023 Feb 8;31(2):288-304.e8. [CrossRef]

- Henke MT, Kenny DJ, Cassilly CD, Vlamakis H, Xavier RJ, Clardy J. Ruminococcus gnavus, a member of the human gut microbiome associated with Crohn’s disease, produces an inflammatory polysaccharide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019 Jun 25;116(26):12672-12677. [CrossRef]

- Li L, Hu J, Qin C, Cai J, Zou X, Tian G, Seeberger PH, Yin J. Immunological evaluation of the autism-related bacterium Enterocloster bolteae capsular polysaccharide driven by chemical synthesis. Chinese Chemical Letters 2025; 36(9): 110797. [CrossRef]

- Plichta DR, Somani J, Pichaud M, Wallace ZS, Fernandes AD, Perugino CA, Lhdesmki H, Stone JH, Vlamakis H, Chung DC, Khanna D, Pillai S, Xavier RJ. Congruent microbiome signatures in fibrosis-prone autoimmune diseases: IgG4-related disease and systemic sclerosis. Genome Med. 2021 Feb 28;13(1):35. [CrossRef]

- Ruuskanen MO, berg F, Mnnist V, Havulinna AS, Mric G, Liu Y, Loomba R, Vzquez-Baeza Y, Tripathi A, Valsta LM, Inouye M, Jousilahti P, Salomaa V, Jain M, Knight R, Lahti L, Niiranen TJ. Links between gut microbiome composition and fatty liver disease in a large population sample. Gut Microbes. 2021 Jan-Dec;13(1):1-22. [CrossRef]

- Mbaye B, Magdy Wasfy R, Borentain P, Tidjani Alou M, Mottola G, Bossi V, Caputo A, Gerolami R, Million M. Increased fecal ethanol and enriched ethanol-producing gut bacteria Limosilactobacillus fermentum, Enterocloster bolteae, Mediterraneibacter gnavus and Streptococcus mutans in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023 Nov 16;13:1279354. [CrossRef]

- Seneff S, Kyriakopoulos A. Cancer, deuterium, and gut microbes: A novel perspective. Endocrine and Metabolic Science 2025; 17: 100215. [CrossRef]

- Olgun, A., 2007. Biological effects of deuteronation: ATP synthase as an example. Theor. Biol. Med. Model. 4, 9. [CrossRef]

- Krichevsky MI, Friedman I,Newell MF, Sisler FD. Deuterium fractionation during molecular hydrogen formation in marine pseudomonad. J Biol Chem 1961; 236: 2520-2525.

- Kane DA. Lactate oxidation at the mitochondria: a lactate-malate-aspartate shuttle at work. Front Neurosci. 2014 Nov 25;8:366. [CrossRef]

- Sutcliffe MJ, Masgrau L, Roujeinikova A, Johannissen LO, Hothi P, Basran J, Ranaghan KE, Mulholland AJ, Leys D, Scrutton NS. Hydrogen tunnelling in enzyme-catalysed H-transfer reactions: flavoprotein and quinoprotein systems. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2006 Aug 29;361(1472):1375-86. [CrossRef]

- Yagi T, Matsuno-Yagi A. The proton-translocating NADH-quinone oxidoreductase in the respiratory chain: the secret unlocked. Biochemistry. 2003 Mar 4;42(8):2266-74. [CrossRef]

- Waddell J, McKenna MC, Kristian T. Brain ethanol metabolism and mitochondria. Curr Top Biochem Res. 2022;23:1-13.

- Yan T, Zhao Y, Jiang Z, Chen J. Acetaldehyde induces cytotoxicity via triggering mitochondrial dysfunction and overactive mitophagy. Mol Neurobiol. 2022 Jun;59(6):3933-3946. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Halder CV, Faria AVS, Andrade SS. Action and function of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in health and disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2017 Dec;31(6):643-648. [CrossRef]

- Khan MT, van Dijl JM, Harmsen HJM. Antioxidants keep the potentially probiotic but highly oxygen-sensitive human gut bacterium Faecalibacterium prausnitzii alive at ambient air. PLoS ONE 2014; 9(5): e96097. [CrossRef]

- Zeng MY, Inohara N, Nuez G. Mechanisms of inflammation-driven bacterial dysbiosis in the gut. Mucosal Immunol. 2017 Jan;10(1):18-26. [CrossRef]

- Soto-Martin EC, Warnke I, Farquharson FM, Christodoulou M, Horgan G, Derrien M, Faurie JM, Flint HJ, Duncan SH, Louis P. Vitamin biosynthesis by human gut butyrate-producing bacteria and cross-feeding in synthetic microbial communities. mBio. 2020 Jul 14;11(4):e00886-20. [CrossRef]

- Jacobson W, Saich T, Borysiewicz LK, Behan WM, Behan PO, Wreghitt TG. Serum folate and chronic fatigue syndrome. Neurology. 1993 Dec;43(12):2645-7. [CrossRef]

- Hoffbrand AV, Stewart JS, Booth CC, Mollin DL. Folate deficiency in Crohn’s disease: incidence, pathogenesis, and treatment. Br Med J. 1968 Apr 13;2(5597):71-5. [CrossRef]

- Yakut M, Ustün Y, Kabaçam G, Soykan I. Serum vitamin B12 and folate status in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Eur J Intern Med. 2010 Aug;21(4):320-3. [CrossRef]

- Christensen KE, Mikael LG, Leung KY, Lévesque N, Deng L, Wu Q, Malysheva OV, Best A, Caudill MA, Greene ND, Rozen R. High folic acid consumption leads to pseudo-MTHFR deficiency, altered lipid metabolism, and liver injury in mice. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015 Mar;101(3):646-58. [CrossRef]

- Patanwala I, King MJ, Barrett DA, Rose J, Jackson R, Hudson M, Philo M, Dainty JR, Wright AJ, Finglas PM, Jones DE. Folic acid handling by the human gut: implications for food fortification and supplementation. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014 Aug;100(2):593-9. [CrossRef]

- Madhogaria B, Bhowmik P, Kundu A. Correlation between human gut microbiome and diseases. Infect Med (Beijing). 2022 Aug 24;1(3):180-191. [CrossRef]

- Xie X, Zubarev RA. Effects of low-level deuterium enrichment on bacterial growth. PLoS One. 2014 Jul 17;9(7):e102071. [CrossRef]

- Paliy O, Bloor D, Brockwell D, Gilbert P, Barber J. Improved methods of cultivation and production of deuterated proteins from E. coli strains grown on fully deuterated minimal medium. J Appl Microbiol. 2003;94(4):580-6. [CrossRef]

- Trchounian K, Trchounian A. Escherichia coli hydrogen gas production from glycerol: Effects of external formate. Renewable Energy, 2015; 83: 345-351.

- Li C, Sessions AL, Kinnaman FS, Valentine DL. Hydrogen-isotopic variability in lipids from Santa Barbara Basin sediments. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 2009; 73: 4803-4823. [CrossRef]

- Gaci N, Borrel G, Tottey W, O’Toole PW, Brugre JF. Archaea and the human gut: new beginning of an old story. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 Nov 21;20(43):16062-78. [CrossRef]

- Thauer RK. Methyl (alkyl)-Coenzyme M reductases: Nickel F-430-containing enzymes involved in anaerobic methane formation and in anaerobic pxidation of methane or of short chain alkanes. Biochemistry. 2019 Dec 31;58(52):5198-5220. [CrossRef]

- Thauer RK, Kaster AK, Seedorf H, Buckel W, Hedderich R. Methanogenic archaea: ecologically relevant differences in energy conservation. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008 Aug;6(8):579-91. [CrossRef]

- Liao Y, Chen S, Wang D, Zhang W, Wang S, Ding J, Wang Y, Cai L, Ran X, Wang X, Zhu H. Structure of formaldehyde dehydrogenase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: the binary complex with the cofactor NAD+. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2013 Sep;69(Pt 9):967-72. [CrossRef]

- Keltjens JT, Pol A, Reimann J, Op den Camp HJ. PQQ-dependent methanol dehydrogenases: rare-earth elements make a difference. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98(14):6163-83. [CrossRef]

- McDowall JS, Murphy BJ, Haumann M, Palmer T, Armstrong FA, Sargent F. Bacterial formate hydrogenlyase complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014 Sep 23;111(38):E3948-56. [CrossRef]

- Chen NH, Djoko KY, Veyrier FJ, McEwan AG. Formaldehyde stress responses in bacterial pathogens. Front Microbiol. 2016 Mar 3;7:257. [CrossRef]

- Ichikawa Y, Yamamoto H, Hirano SI, Sato B, Takefuji Y, Satoh F. The overlooked benefits of hydrogen-producing bacteria. Med Gas Res. 2023 Jul-Sep;13(3):108-111. [CrossRef]

- Smith NW, Shorten PR, Altermann EH, Roy NC, McNabb WC. Hydrogen cross- feeders of the human gastrointestinal tract. Gut Microbes. 2019;10(3):270-288. [CrossRef]

- Hay S, Pudney CR, Scrutton NS. Structural and mechanistic aspects of flavoproteins: probes of hydrogen tunnelling. FEBS J. 2009 Aug;276(15):3930-41. [CrossRef]

- Greene BL, Wu CH, McTernan PM, Adams MW, Dyer RB. Proton-coupled electron transfer dynamics in the catalytic mechanism of a [NiFe]-hydrogenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015; 137(13): 45584566. [CrossRef]

- Frolov EN, Elcheninov AG, Gololobova AV, Toshchakov SV, Novikov AA, Lebedinsky AV, Kublanov IV. Obligate autotrophy at the thermodynamic limit of life in a new acetogenic bacterium. Front Microbiol. 2023 May 12;14:1185739. [CrossRef]

- Fu M, Zhang W, Wu L, Yang G, Li H, Wang R. Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) metabolism in mitochondria and its regulatory role in energy production. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 Feb 21;109(8):2943-8. [CrossRef]

- Gasaly N, Hermoso MA, Gotteland M. Butyrate and the fine-tuning of colonic homeostasis: Implication for inflammatory bowel diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Mar 17;22(6):3061. [CrossRef]

- Froese DS, Fowler B, Baumgartner MR. Vitamin B12, folate, and the methionine remethylation cycle-biochemistry, pathways, and regulation. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2019 Jul;42(4):673-685. [CrossRef]

- Borrel G, Brugre JF, Gribaldo S, Schmitz RA, Moissl-Eichinger C. The host-associated archaeome. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2020 Nov;18(11):622-636. [CrossRef]

- Lang K, Schuldes J, Klingl A, Poehlein A, Daniel R, Brunea A. New mode of energy metabolism in the seventh order of methanogens as revealed by comparative genome analysis of Candidatus methanoplasma termitum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015 Feb;81(4):1338-52. [CrossRef]

- Bueno de Mesquita CP, Wu D, Tringe SG. Methyl-based methanogenesis: an eco- logical and genomic review. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2023 Mar 21;87(1):e0002422. [CrossRef]

- de la Cuesta-Zuluaga J, Spector TD, Youngblut ND, Ley RE. Genomic insights into adaptations of trimethylamine-utilizing methanogens to diverse habitats, including the human gut. mSystems. 2021 Feb 9;6(1):e00939-20. [CrossRef]

- Chen YR, Chen LD, Zheng LJ. Exploring the trimethylamine-degrading genes in the human gut microbiome. AMB Express. 2025 Jun 12;15(1):91. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh R, Mahnert A, Shinde T, Kumpitsch C, Weinberger V, Schmidt H, Moissl-Eichinger C. Age-related dynamics of predominant methanogenic archaea in the human gut microbiome. BMC Microbiol. 2025 Apr 4;25(1):193. [CrossRef]

- Chen YM, Liu Y, Zhou RF, Chen XL, Wang C, Tan XY, Wang LJ, Zheng RD, Zhang HW, Ling WH, Zhu HL. Associations of gut-flora-dependent metabolite trimethylamine- N-oxide, betaine and choline with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in adults. Sci Rep. 2016 Jan 8;6:19076. [CrossRef]

- Ernst L, Steinfeld B, Barayeu U, Klintzsch T, Kurth M, Grimm D, Dick TP, Rebelein JG, Bischofs IB, Keppler F. Methane formation driven by reactive oxygen species across all living organisms. Nature. 2022 Mar;603(7901):482-487. [CrossRef]

- Keppler F, Ernst L, Polag D, Zhang J, Boros M. ROS-driven cellular methane formation: Potential implications for health sciences. Clin Transl Med. 2022 Jul;12(7):e905. [CrossRef]

- Gibellini F, Smith TK. The Kennedy pathway – De novo synthesis of phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylcholine. IUBMB Life. 2010 Jun;62(6):414-28. [CrossRef]

- Corbin KD, Zeisel SH. Choline metabolism provides novel insights into nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and its progression. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2012 Mar;28(2):159-65. [CrossRef]

- Wan S, Kuipers F, Havinga R, Ando H, Vance DE, Jacobs RL, van der Veen JN. Impaired hepatic phosphatidylcholine synthesis leads to cholestasis in mice challenged with a high-fat diet. Hepatol Commun. 2019 Jan 2;3(2):262-276. [CrossRef]

- McNeil SD, Nuccio ML, Ziemak MJ, Hanson AD. Enhanced synthesis of choline and glycine betaine in transgenic tobacco plants that overexpress phosphoethanolamine N-methyltransferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001 Aug 14;98(17):10001-5. [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi G, Motokawa Y, Yoshida T, Hiraga K. Glycine cleavage system: reaction mechanism, physiological significance, and hyperglycinemia. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2008;84(7):246-63. [CrossRef]

- Niculescu MD, Zeisel SH. Diet, methyl donors and DNA methylation: interactions between dietary folate, methionine and choline. J Nutr. 2002 Aug;132(8 Suppl):2333S-2335S. [CrossRef]

- Craciun S, Balskus EP. Microbial conversion of choline to trimethylamine requires a glycyl radical enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 Dec 26;109(52):21307-12. [CrossRef]

- Ramezani A, Nolin TD, Barrows IR, Serrano MG, Buck GA, Regunathan-Shenk R, West RE 3rd, Latham PS, Amdur R, Raj DS. Gut colonization with methanogenic archaea lowers plasma trimethylamine N-oxide concentrations in apolipoprotein e-/- mice. Sci Rep. 2018 Oct 3;8(1):14752. [CrossRef]

- Basran J, Sutcliffe MJ, Scrutton NS. Deuterium isotope effects during carbon-hydrogen bond cleavage by trimethylamine dehydrogenase. Implications for mechanism and vibrationally assisted hydrogen tunneling in wild-type and mutant enzymes. J Biol Chem. 2001 Jul 6;276(27):24581-7. [CrossRef]

- Wanninayake US, Subedi B, Fitzpatrick PF. pH and deuterium isotope effects on the reaction of trimethylamine dehydrogenase with dimethylamine. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2019 Nov 15;676:108136. [CrossRef]

- Growdon JH, Hirsch MJ, Wurtman RJ, Wiener W. Oral choline administration to patients with tardive dyskinesia. N Engl J Med. 1977 Sep 8;297(10):524-7. [CrossRef]

- Kansakar U, Trimarco V, Mone P, Varzideh F, Lombardi A, Santulli G. Choline supplements: An update. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023 Mar 7;14:1148166. [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 1998. [CrossRef]

- Grand View Research, Inc. Nootropics Market Size, Share and Trends Report, 2030. 2025. [last accessed August 15,2025]. https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/nootropics-market.

- Zhao J, Wei S, Liu F, Liu D. Separation and characterization of acetone-soluble phosphatidylcholine from Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba) oil. Eur Food Res Technol 2014; 238: 1023–1028. [CrossRef]

- Blackett EG, Soliday AJ. Preparation of choline base and choline salts. US Patent #US2774759A. 1955. [last accessed August 15, 2025]. https://patents.google.com/patent/US2774759A/en.

- Wilcox J, Skye SM, Graham B, Zabell A, Li XS, Li L, Shelkay S, Fu X, Neale S, O'Laughlin C, Peterson K, Hazen SL, Tang WHW. Dietary choline supplements, but not eggs, raise fasting TMAO levels in participants with normal renal function: A randomized clinical trial. Am J Med. 2021 Sep;134(9):1160-1169.e3. [CrossRef]

- Zhu W, Wang Z, Tang WHW, Hazen SL. Gut microbe-generated trimethylamine N-oxide from dietary choline is prothrombotic in subjects. Circulation. 2017 Apr 25;135(17):1671-1673. [CrossRef]

- Arias N, Arboleya S, Allison J, Kaliszewska A, Higarza SG, Gueimonde M, Arias JL. The relationship between choline bioavailability from diet, intestinal microbiota composition, and its modulation of human diseases. Nutrients. 2020 Aug 5;12(8):2340. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Y, Zhang Y, Jin S, Lv J, Li M, Feng N. The gut microbiota derived metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide: Its important role in cancer and other diseases. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024 Aug;177:117031. [CrossRef]

- Alharbi YM, Bima AI, Elsamanoudy AZ. An overview of the perspective of cellular autophagy: mechanism, regulation, and the role of autophagy dysregulation in the pathogenesis of diseases. J Microsc Ultrastruct. 2021 Jan 9;9(2):47-54. [CrossRef]

- Bhutia SK, Mukhopadhyay S, Sinha N, Das DN, Panda PK, Patra SK, Maiti TK, Mandal M, Dent P, Wang XY, Das SK, Sarkar D, Fisher PB. Autophagy: cancer's friend or foe? Adv Cancer Res. 2013;118:61-95. [CrossRef]

- Su JQ, Wu XQ, Wang Q, Xie BY, Xiao CY, Su HY, Tang JX, Yao CW. The microbial metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide and the kidney diseases. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2025 Mar 11;15:1488264. [CrossRef]

- Praharaj PP, Singh A, Patil S, Dhiman R, Bhutia SK. Mitochondrial dysfunction as a driver of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and its modulation through mitophagy for potential therapeutics. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2021 Jul;136:106013. [CrossRef]

- Dong F, Jiang S, Tang C, Wang X, Ren X, Wei Q, Tian J, Hu W, Guo J, Fu X, Liu L, Patzak A, Persson PB, Gao F, Lai EY, Zhao L. Trimethylamine N-oxide promotes hyperoxaluria-induced calcium oxalate deposition and kidney injury by activating autophagy. Free Radic Biol Med. 2022 Feb 1;179:288-300. [CrossRef]

- Atherosclerosis by regulating low-density lipoprotein-induced autophagy in vascular smooth muscle cells through PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Int Heart J. 2023;64(3):462-469. [CrossRef]

- Davies MJ, Gordon JL, Gearing AJ, Pigott R, Woolf N, Katz D, Kyriakopoulos A. The expression of the adhesion molecules ICAM-1, VCAM-1, PECAM, and E-selectin in human atherosclerosis. J Pathol. 1993 Nov;171(3):223-9. [CrossRef]

- Saaoud F, Liu L, Xu K, Cueto R, Shao Y, Lu Y, Sun Y, Snyder NW, Wu S, Yang L, Zhou Y, Williams DL, Li C, Martinez L, Vazquez-Padron RI, Zhao H, Jiang X, Wang H, Yang X. Aorta- and liver-generated TMAO enhances trained immunity for increased inflammation via ER stress/mitochondrial ROS/glycolysis pathways. JCI Insight. 2023 Jan 10;8(1):e158183. [CrossRef]

- Lei D, Liu Y, Liu Y, Jiang Y, Lei Y, Zhao F, Li W, Ouyang Z, Chen L, Tang S, Ouyang D, Li X, Li Y. The gut microbiota metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide promotes cardiac hypertrophy by activating the autophagic degradation of SERCA2a. Commun Biol. 2025 Apr 10;8(1):596. [CrossRef]

- Fiorillo C, Astrea G, Savarese M, Cassandrini D, Brisca G, Trucco F, Pedemonte M, Trovato R, Ruggiero L, Vercelli L, D'Amico A, Tasca G, Pane M, Fanin M, Bello L, Broda P, Musumeci O, Rodolico C, Messina S, Vita GL, Sframeli M, Gibertini S, Morandi L, Mora M, Maggi L, Petrucci A, Massa R, Grandis M, Toscano A, Pegoraro E, Mercuri E, Bertini E, Mongini T, Santoro L, Nigro V, Minetti C, Santorelli FM, Bruno C; Italian Network on Congenital Myopathies. MYH7-related myopathies: clinical, histopathological and imaging findings in a cohort of Italian patients. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2016 Jul 7;11(1):91. [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa Y, Nishikimi T, Kuwahara K. Atrial and brain natriuretic peptides: Hormones secreted from the heart. Peptides. 2019 Jan;111:18-25. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh R, Fatahian AN, Rouzbehani OMT, Hathaway MA, Mosleh T, Vinod V, Vowles S, Stephens SL, Chung SD, Cao ID, Jonnavithula A, Symons JD, Boudina S. Sequestosome 1 (p62) mitigates hypoxia-induced cardiac dysfunction by stabilizing hypoxia-inducible factor 1α and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2. Cardiovasc Res. 2024 Apr 30;120(5):531-547. [CrossRef]

- Zixin Y, Lulu C, Xiangchang Z, Qing F, Binjie Z, Chunyang L, Tai R, Dongsheng O. TMAO as a potential biomarker and therapeutic target for chronic kidney disease: A review. Front Pharmacol. 2022 Aug 12;13:929262. [CrossRef]

- Varzideh F, Farroni E, Kaunsakar U, Eiwaz M, Jankauskas SS, Santulli G. TMAO accelerates cellular aging by disrupting endoplasmic reticulum integrity and mitochondrial unfolded protein response. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2025 Jan 21;82(1):53. [CrossRef]

- Makrecka-Kuka M, Volska K, Antone U, Vilskersts R, Grinberga S, Bandere D, Liepinsh E, Dambrova M. Trimethylamine N-oxide impairs pyruvate and fatty acid oxidation in cardiac mitochondria. Toxicol Lett. 2017 Feb 5;267:32-38. [CrossRef]

- García-Miranda A, Montes-Alvarado JB, Sarmiento-Salinas,FL, Vallejo-Ruiz V, Castañeda-Saucedo E, Navarro-Tito N, Maycotte P. Regulation of mitochondrial metabolism by autophagy supports leptin-induced cell migration. Sci Rep 2024; 14: 1408. [CrossRef]

- Greer EL, Shi Y. Histone methylation: a dynamic mark in health, disease and inheritance. Nat Rev Genet. 2012 Apr 3;13(5):343-57. [CrossRef]

- Li T, Wei Y, Qu M, Mou L, Miao J, Xi M, Liu Y, He R. Formaldehyde and de/methylation in age-related cognitive impairment. Genes (Basel). 2021 Jun 13;12(6):913. [CrossRef]

- Bae S, Chon J, Field MS, Stover PJ. Alcohol dehydrogenase 5 is a source of formate for de novo purine biosynthesis in HepG2 cells. J Nutr. 2017 Apr;147(4):499-505. [CrossRef]

- Yin Y, Morgunova E, Jolma A, Kaasinen E, Sahu B, Khund-Sayeed S, Das PK, Kivioja T, Dave K, Zhong F, Nitta KR, Taipale M, Popov A, Ginno PA, Domcke S, Yan J, Schbeler D, Vinson C, Taipale J. Impact of cytosine methylation on DNA binding specificities of human transcription factors. Science. 2017 May 5;356(6337):eaaj2239. [CrossRef]

- Jang HS, Shin WJ, Lee JE, Do JT. CpG and non-CpG methylation in epigenetic gene regulation and brain function. Genes (Basel). 2017 May 23;8(6):148. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Lu X, Lu J, Liang H, Dai Q, Xu GL, Luo C, Jiang H, He C. Thymine DNA glycosylase specifically recognizes 5-carboxylcytosine-modified DNA. Nat Chem Biol. 2012 Feb 12;8(4):328-30. [CrossRef]

- Scourzic L, Mouly E, Bernard OA. TET proteins and the control of cytosine demethylation in cancer. Genome Med. 2015 Jan 29;7(1):9. [CrossRef]

- Feng Y, Chen JJ, Xie NB, Ding JH, You XJ, Tao WB, Zhang X, Yi C, Zhou X, Yuan BF, Feng YQ. Direct decarboxylation of ten-eleven translocation-produced 5-carboxylcytosine in mammalian genomes forms a new mechanism for active DNA demethylation. Chem Sci. 2021 Jul 21;12(34):11322-11329. [CrossRef]

- Jonasson NSW, Daumann LJ. 5-Methylcytosine is oxidized to the natural metabolites of TET enzymes by a biomimetic iron(IV)-oxo complex. Chemistry. 2019 Sep 18;25(52):12091-12097. doi: 10.1002/chem.201902340. Erratum in: Chemistry. 2019 Nov 22;25(65):15004. [CrossRef]

- Ji F, Zhao C, Wang B, Tang Y, Miao Z, Wang Y. The role of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mitochondria after ischemic stroke. J Neurosci Res. 2018 Oct;96(10):1717-1726. [CrossRef]

- Gao Q, Shen K, Xiao M. TET2 mutation in acute myeloid leukemia: biology, clinical significance, and therapeutic insights. Clin Epigenetics. 2024 Nov 9;16(1):155. [CrossRef]

- Huang F, Sun J, Chen W, Zhang L, He X, Dong H, Wu Y, Wang H, Li Z, Ball B, Khaled S, Marcucci G, Li L. TET2 deficiency promotes MDS-associated leukemogenesis. Blood Cancer J. 2022 Oct 4;12(10):141. doi: 10.1038/s41408-022-00739-w. Erratum in: Blood Cancer J. 2023 Nov 28;13(1):174. [CrossRef]

- Oliphant K, Allen-Vercoe E. Macronutrient metabolism by the human gut microbiome: major fermentation by-products and their impact on host health. Microbiome. 2019 Jun 13;7(1):91. [CrossRef]

- Tangerman A. Measurement and biological significance of the volatile sulfur compounds hydrogen sulfide, methanethiol and dimethyl sulfide in various biological matrices. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2009 Oct 15;877(28):3366-77. Epub 2009 May 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philipp TM, Gernoth L, Will A, Schwarz M, Ohse VA, Kipp AP, Steinbrenner H, Klotz LO. Selenium-binding protein 1 (SELENBP1) is a copper-dependent thiol oxidase. Redox Biol. 2023 Sep;65:102807. [CrossRef]

- Seneff S, Kyriakopoulos AM. Deuterium trafficking, mitochondrial dysfunction, copper homeostasis, and neurodegenerative disease. Front Mol Biosci. 2025 Jul 22;12:1639327. [CrossRef]

- Schott M, de Jel MM, Engelmann JC, Renner P, Geissler EK, Bosserhoff AK, Kuphal S. Selenium-binding protein 1 is down-regulated in malignant melanoma. Oncotarget. 2018 Jan 2;9(12):10445-10456. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, Li F, Younes M, Liu H, Chen C, Yao Q. Reduced selenium-binding protein 1 in breast cancer correlates with poor survival and resistance to the anti-proliferative effects of selenium. PLoS One. 2013 May 21;8(5):e63702. [CrossRef]

- Wu X, Han Z, Liu B, Yu D, Sun J, Ge L, Tang W, Liu S. Gut microbiota contributes to the methionine metabolism in host. Front Microbiol. 2022 Dec 22;13:1065668. [CrossRef]

- McHugh D, Gil J. Senescence and aging: Causes, consequences, and therapeutic avenues. J Cell Biol. 2018 Jan 2;217(1):65-77. [CrossRef]

- Lee WS, Monaghan P, Metcalfe NB. Experimental demonstration of the growth rate--lifespan trade-off. Proc Biol Sci. 2012 Dec 12;280(1752):20122370. [CrossRef]

- Haigis MC, Yankner BA. The aging stress response. Mol Cell. 2010 Oct 22;40(2):333-44. [CrossRef]

- Orentreich N, Matias JR, DeFelice A, Zimmerman JA. Low methionine ingestion by rats extends life span. J Nutr. 1993 Feb;123(2):269-74. [CrossRef]

- Caro P, Gomez J, Sanchez I, Naudi A, Ayala V, Lpez-Torres M, Pamplona R, Barja G. Forty percent methionine restriction decreases mitochondrial oxygen radical production and leak at complex I during forward electron flow and lowers oxidative damage to proteins and mitochondrial DNA in rat kidney and brain mitochondria. Rejuvenation Res. 2009 Dec;12(6):421-34. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Zhang Y, Xu Y, Luo T, Ge Y, Jiang Y, Shi Y, Sun J, Le G. Dietary methionine restriction improves the gut microbiota and reduces intestinal permeability and inflammation in high-fat-fed mice. Food Funct. 2019 Sep 1;10(9):5952-5968. [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan A, Lasher AT, Morrow CD, Sun LY. Long term methionine restriction: Influence on gut microbiome and metabolic characteristics. Aging Cell. 2024 Mar;23(3):e14051. [CrossRef]

- Brown-Borg, H. M., Rakoczy, S. G., Wonderlich, J. A., Rojanathammanee, L., Kopchick, J. J., Armstrong, V., Raasakka, D. Growth hormone signaling is necessary for lifespan extension by dietary methionine. Aging Cell 2014; 13: 10191027. [CrossRef]

- Kim YT, Kwon JG, O’Sullivan DJ, Lee JH. Regulatory mechanism of cysteine-dependent methionine biosynthesis in Bifidobacterium longum: insights into sulfur metabolism in gut microbiota. Gut Microbes. 2024 Jan-Dec;16(1):2419565. [CrossRef]

- Ferla MP, Patrick WM. Bacterial methionine biosynthesis. Microbiology (Reading). 2014 Aug;160(Pt 8):1571-1584. [CrossRef]

- Lu M, Yang Y, Xu Y, Wang X, Li B, Le G, Xie Y. Dietary methionine restriction alleviates choline-induced tri-methylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) elevation by manipulating gut microbiota in mice. Nutrients. 2023 Jan 1;15(1):206. [CrossRef]

- Hogg RC, Raggenbass M, Bertrand D. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: from structure to brain function. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;147:1-46. [CrossRef]

- Santiago LJ, Abrol R. Understanding G protein selectivity of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors using computational methods. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Oct 24;20(21):5290. [CrossRef]

- Kruse AC, Kobilka BK, Gautam D, Sexton PM, Christopoulos A, Wess J. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors: novel opportunities for drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014 Jul;13(7):549-60. Epub 2014 Jun 6. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Arduini A, Zammit V. Acetate transport into mitochondria does not require a carnitine shuttle mechanism. Magn Reson Med. 2017 Jan;77(1):11. [CrossRef]

- Moffett JR, Puthillathu N, Vengilote R, Jaworski DM, Namboodiri AM. Acetate revisited: a key biomolecule at the nexus of metabolism, epigenetics and oncogenesis-part 1: acetyl-CoA, acetogenesis and acyl-CoA short-chain synthetases. Front Physiol. 2020 Nov 12;11:580167. [CrossRef]

- Hlavaty SI, Salcido KN, Pniewski KA, Mukha D, Ma W, Kannan T, Cassel J, Srikanth YVV, Liu Q, Kossenkov A, Salvino JM, Chen Q, Schug ZT. ACSS1-dependent acetate utilization rewires mitochondrial metabolism to support AML and melanoma tumor growth and metastasis. Cell Rep. 2024 Dec 24;43(12):114988. [CrossRef]

- Du H, Guo L, Yan S, Sosunov AA, McKhann GM, Yan SS. Early deficits in synaptic mitochondria in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Oct 26;107(43):18670-5. [CrossRef]

- Waniewski RA, Martin DL. Preferential utilization of acetate by astrocytes is attributable to transport. J Neurosci. 1998 Jul 15;18(14):5225-33. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Szutowicz A, Bielarczyk H, Jankowska-Kulawy A, Paweczyk T, Ronowska A. Acetyl-CoA the key factor for survival or death of cholinergic neurons in course of neurodegenerative diseases. Neurochem Res. 2013 Aug;38(8):1523-42. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Vieira TH, Guimaraes IM, Silva FR, Ribeiro FM. Alzheimer's disease: Targeting the cholinergic system. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2016;14(1):101-15. [CrossRef]

- Aroniadou-Anderjaska V, Figueiredo TH, de Araujo Furtado M, Pidoplichko VI, Braga MFM. Mechanisms of organophosphate toxicity and the role of acetylcholinesterase inhibition. Toxics. 2023 Oct 18;11(10):866. [CrossRef]

- Ngoula F, Watcho P, Dongmo MC, Kenfack A, Kamtchouing P, Tchoumboué J. Effects of pirimiphos-methyl (an organophosphate insecticide) on the fertility of adult male rats. Afr Health Sci. 2007 Mar;7(1):3-9. [CrossRef]

- Bourassa MW, Alim I, Bultman SJ, Ratan RR. Butyrate, neuroepigenetics and the gut microbiome: Can a high fiber diet improve brain health? Neurosci Lett. 2016 Jun 20;625:56-63. [CrossRef]

- Dalile B, Van Oudenhove L, Vervliet B, Verbeke K. The role of short-chain fatty acids in microbiota-gut-brain communication. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019. Aug;16(8):461-478. [CrossRef]

- Benítez-Páez A, Kjølbæk L, Gómez Del Pulgar EM, Brahe LK, Astrup A, Matysik S, Schött HF, Krautbauer S, Liebisch G, Boberska J, Claus S, Rampelli S, Brigidi P, Larsen LH, Sanz Y. A Multi-omics approach to unraveling the microbiome-mediated effects of arabinoxylan oligosaccharides in overweight humans. mSystems. 2019 May 28;4(4):e00209-19. [CrossRef]

- Hodgkinson K, El Abbar F, Dobranowski P, Manoogian J, Butcher J, Figeys D, Mack D, Stintzi A. Butyrate's role in human health and the current progress towards its clinical application to treat gastrointestinal disease. Clin Nutr. 2023 Feb;42(2):61-75. [CrossRef]

- Guilloteau P, Martin L, Eeckhaut V, Ducatelle R, Zabielski R, Van Immerseel F. From the gut to the peripheral tissues: the multiple effects of butyrate. Nutr Res Rev. 2010 Dec;23(2):366-84. [CrossRef]

- Anshory M, Effendi RMRA, Kalim H, Dwiyana RF, Suwarsa O, Nijsten TEC, Nouwen JL, Thio HB. Butyrate properties in immune-related diseases: Friend or foe? Fermentation 2023; 9: 205. [CrossRef]

- Bachmann C, Colombo JP, Berüter J. Short chain fatty acids in plasma and brain: quantitative determination by gas chromatography. Clin Chim Acta. 1979 Mar 1;92(2):153-9. [CrossRef]

- Liu H, Wang J, He T, Becker S, Zhang G, Li D, Ma X. Butyrate: A double-edged sword for health? Adv Nutr. 2018 Jan 1;9(1):21-29. [CrossRef]

- Recharla N, Geesala R, Shi XZ. Gut microbial metabolite butyrate and its therapeutic role in inflammatory bowel disease: A literature review. Nutrients. 2023 May 11;15(10):2275. [CrossRef]

- Coccia C, Bonomi F, Lo Cricchio A, Russo E, Peretti S, Bandini G, Lepri G, Bartoli F, Moggi-Pignone A, Guiducci S, Del Galdo F, Furst DE, Matucci Cerinic M, Bellando-Randone S. The potential role of butyrate in the pathogenesis and treatment of autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Biomedicines. 2024 Aug 5;12(8):1760. [CrossRef]

- Yip W, Hughes MR, Li Y, Cait A, Hirst M, Mohn WW, McNagny KM. Butyrate shapes immune cell fate and function in allergic asthma. Front Immunol. 2021 Feb 15;12:628453. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Liu C, Jiang Q, Yin Y. Butyrate in energy metabolism: There is still more to learn. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2021 Mar;32(3):159-169. [CrossRef]

- Milani C, Duranti S, Bottacini F, Casey E, Turroni F, Mahony J, Belzer C, Delgado Palacio S, Arboleya Montes S, Mancabelli L, Lugli GA, Rodriguez JM, Bode L, de Vos W, Gueimonde M, Margolles A, van Sinderen D, Ventura M. The first microbial colonizers of the human gut: Composition, activities, and health implications of the infant gut microbiota. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2017 Nov 8;81(4):e00036-17. [CrossRef]

- Fujimura KE, Sitarik AR, Havstad S, Lin DL, Levan S, Fadrosh D, Panzer AR, LaMere B, Rackaityte E, Lukacs NW, Wegienka G, Boushey HA, Ownby DR, Zoratti EM, Levin AM, Johnson CC, Lynch SV. Neonatal gut microbiota associates with childhood multisensitized atopy and T cell differentiation. Nat Med. 2016 Oct;22(10):1187-1191. [CrossRef]

- Stilling RM, van de Wouw M, Clarke G, Stanton C, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. The neuropharmacology of butyrate: The bread and butter of the microbiota-gut-brain axis? Neurochem Int. 2016 Oct;99:110-132. [CrossRef]

- Coppola S, Avagliano C, Sacchi A, Laneri S, Calignano A, Voto L, Luzzetti A, Berni Canani R. Potential clinical applications of the postbiotic butyrate in human skin diseases. Molecules. 2022 Mar 12;27(6):1849. [CrossRef]

- Bachar-Wikstrom E, Manchanda M, Bansal R, Karlsson M, Kelly-Pettersson P, Sköldenberg O, Wikstrom JD. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in human chronic wound healing: Rescue by 4-phenylbutyrate. Int Wound J. 2021 Feb;18(1):49-61. [CrossRef]

- Rose S, Bennuri SC, Davis JE, Wynne R, Slattery JC, Tippett M, Delhey L, Melnyk S, Kahler SG, MacFabe DF, Frye RE. Butyrate enhances mitochondrial function during oxidative stress in cell lines from boys with autism. Transl Psychiatry. 2018 Feb 2;8(1):42. [CrossRef]

- Walsh ME, Bhattacharya A, Sataranatarajan K, Qaisar R, Sloane L, Rahman MM, Kinter M, Van Remmen H. The histone deacetylase inhibitor butyrate improves metabolism and reduces muscle atrophy during aging. Aging Cell. 2015 Dec;14(6):957-70. [CrossRef]

- He L, Zhong Z, Wen S, Li P, Jiang Q, Liu F. Gut microbiota-derived butyrate restores impaired regulatory T cells in patients with AChR myasthenia gravis via mTOR-mediated autophagy. Cell Commun Signal. 2024 Apr 3;22(1):215. [CrossRef]

- Kalkan AE, BinMowyna MN, Raposo A, Ahmad MF, Ahmed F, Otayf AY, Carrascosa C, Saraiva A, Karav S. Beyond the gut: Unveiling butyrate's global health impact through gut health and dysbiosis-related conditions: a narrative review. Nutrients. 2025 Apr 9;17(8):1305. [CrossRef]

- Casper D, Davies P. Stimulation of choline acetyltransferase activity by retinoic acid and sodium butyrate in a cultured human neuroblastoma. Brain Res. 1989 Jan 23;478(1):74-84. [CrossRef]

- Wu SH, Chen KL, Hsu C, Chen HC, Chen JY, Yu SY, Shiu YJ. Creatine supplementation for muscle growth: A scoping review of randomized clinical trials from 2012 to 2021. Nutrients. 2022 Mar 16;14(6):1255. [CrossRef]

- Bonilla DA, Kreider RB, Stout JR, Forero DA, Kerksick CM, Roberts MD, Rawson ES. Metabolic basis of creatine in health and disease: A bioinformatics-assisted review. Nutrients. 2021 Apr 9;13(4):1238. [CrossRef]

- Brosnan JT, da Silva RP, Brosnan ME. The metabolic burden of creatine synthesis. Amino Acids. 2011 May;40(5):1325-31. Epub 2011 Mar 9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostojic SM. Creatine synthesis in the skeletal muscle: The times they are a-changin. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2021 Feb 1;320(2):E390E391. [CrossRef]

- Seneff S, Nigh G, Kyriakopoulos AM. Is deuterium sequestering by reactive carbon atoms an important mechanism to reduce deuterium content in biological water? FASEB Bioadv. 2025 May 14;7(6):e70019. [CrossRef]

- Sletten MR, Schoenheimer R. The metabolism of 1(-)-proline studied with the aid of deuterium and isotopicnitrogen. J Biol Chem 1944; 153: 113-13.

- Dewangan S, Rawat V, Thakur AS. Imidazolidinones derivatives as pioneering anti-cancer agents: Unraveling insights through synthesis and structure-activity exploration. Chemistry Europe 2024; 9(23): e202401379. [CrossRef]

- Bąchor R, Konieczny A, Szewczuk Z. Preparation of isotopically labelled standards of creatinine via H/D exchange and their application in quantitative analysis by LC-MS. Molecules. 2020 Mar 26;25(7):1514. [CrossRef]

- Marshall RP, Droste JN, Giessing J, Kreider RB. Role of creatine supplementation in conditions involving mitochondrial dysfunction: A narrative review. Nutrients. 2022 Jan 26;14(3):529. [CrossRef]

- Sun Y, Rahbani JF, Jedrychowski MP, Riley CL, Vidoni S, Bogoslavski D, Hu B, Dumesic PA, Zeng X, Wang AB, Knudsen NH, Kim CR, Marasciullo A, Milln JL, Chouchani ET, Kazak L, Spiegelman BM. Mitochondrial TNAP controls thermogenesis by hydrolysis of phosphocreatine. Nature. 2021 May;593(7860):580-585. [CrossRef]

- Kupriyanov VV, Steinschneider AYa, Ruuge EK, Smirnov VN, Saks VA. 31P-NMR spectrum of phosphocreatine: Deuterium-induced splitting of the signal. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1983 Aug 12;114(3):1117-25. [CrossRef]

| Reaction | Enzymes involved |

|---|---|

| 4H2 + CO2 → CH4 + 2H2O | Methanogenesis by archaea |

| CH4 + O2 + NADH + H+ → CH3OH + NAD+ + H2O | Methane monooxygenase |

| CH3OH + NAD+ → HCHO + NADH + H+ | Methanol dehydrogenase |

| HCHO + NAD+ + H2O → HCOOH + NADH + H+ | Formaldehyde dehydrogenase |

| HCOOH + NAD+ → CO2 + NADH + H+ | Formate dehydrogenase |

| 4H2 + 2NAD+ + O2→ 2NADH + 2H+ + 2H2O | Overall Reaction |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).