1. Introduction and the Historical Context of Artery of Desproges-Gotteron

In the 1950s, Robert Desproges-Gotteron, a French physician at the Lariboisière teaching hospital in Paris, studied 91 patients with sciatica and motor loss from a large cohort of rheumatology, neurology and neurosurgery cases [

1] The study found that the degree of disc herniation was not necessarily associated with motor loss, raising concerns about potential vascular problems. Cadaveric examination revealed that in three out of twelve individuals, a vessel (the Artery of Desproges-Gotteron (ADG)) supplied the L-5 and S-1 nerve roots and extended to the ventral surface of the conus [

1] Desproges-Gotteron also discovered that in about 15% of cases the Adamkiewicz artery (AKA) was absent or started higher than usual, and that in such circumstances an artery following a lower lumbar nerve invariably resulted in reduced spinal cord supply. The 1955 paper "Contribution à l'étude de la sciatique paralysante" (Study of the paralysing sciatica) highlighted his extensive research, which revealed previously unreported knowledge in the field [

1,

2]. Beyond these achievements, Desproges-Gotteron's commitment to innovation has left an indelible mark on medicine, inspiring future generations to push the boundaries of knowledge and practice. His discovery of the ADG provided a fundamental understanding of the intricate vascular network of the conus medullaris and cauda equina, both of which have significant implications for contemporary clinical medicine.

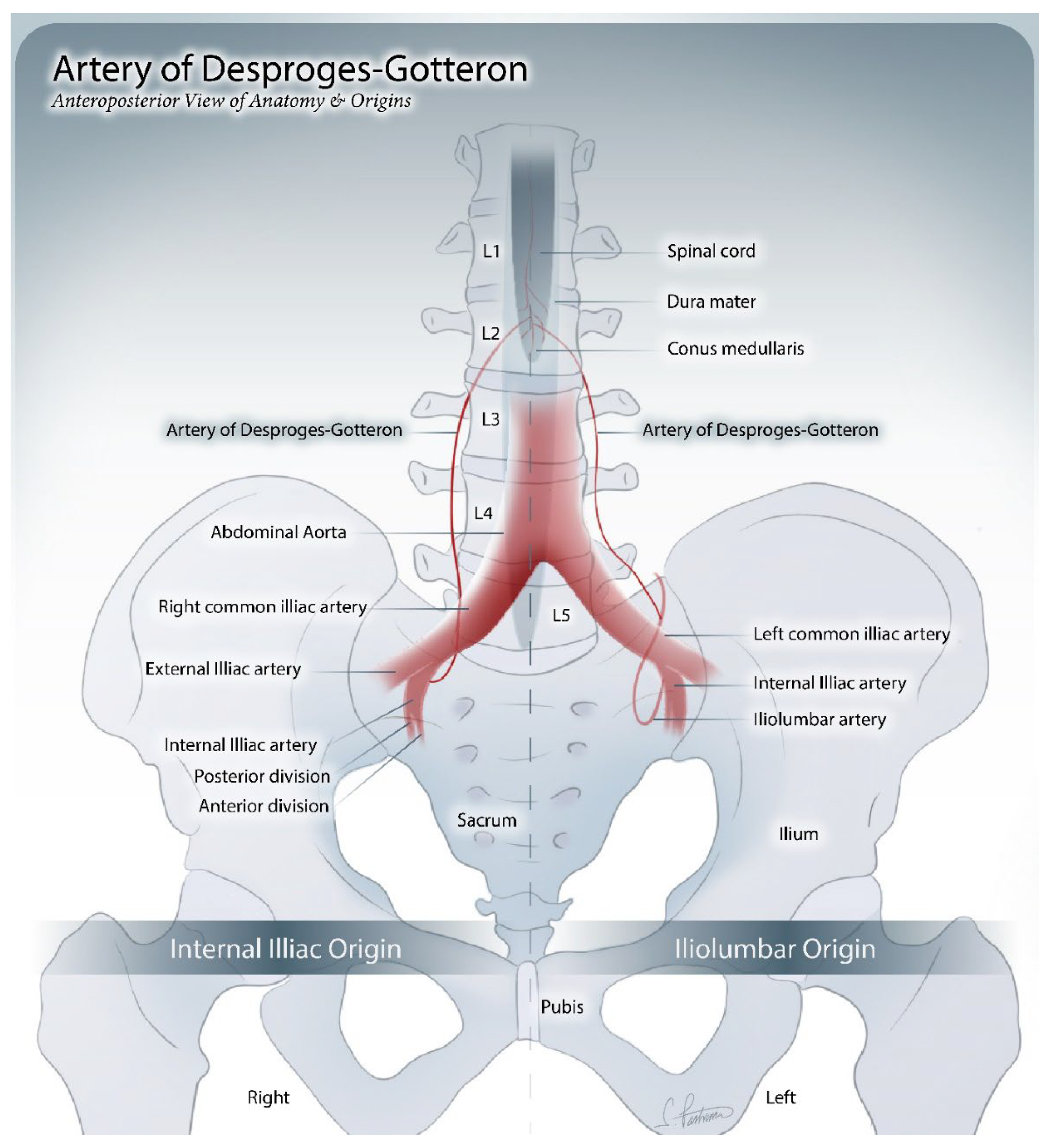

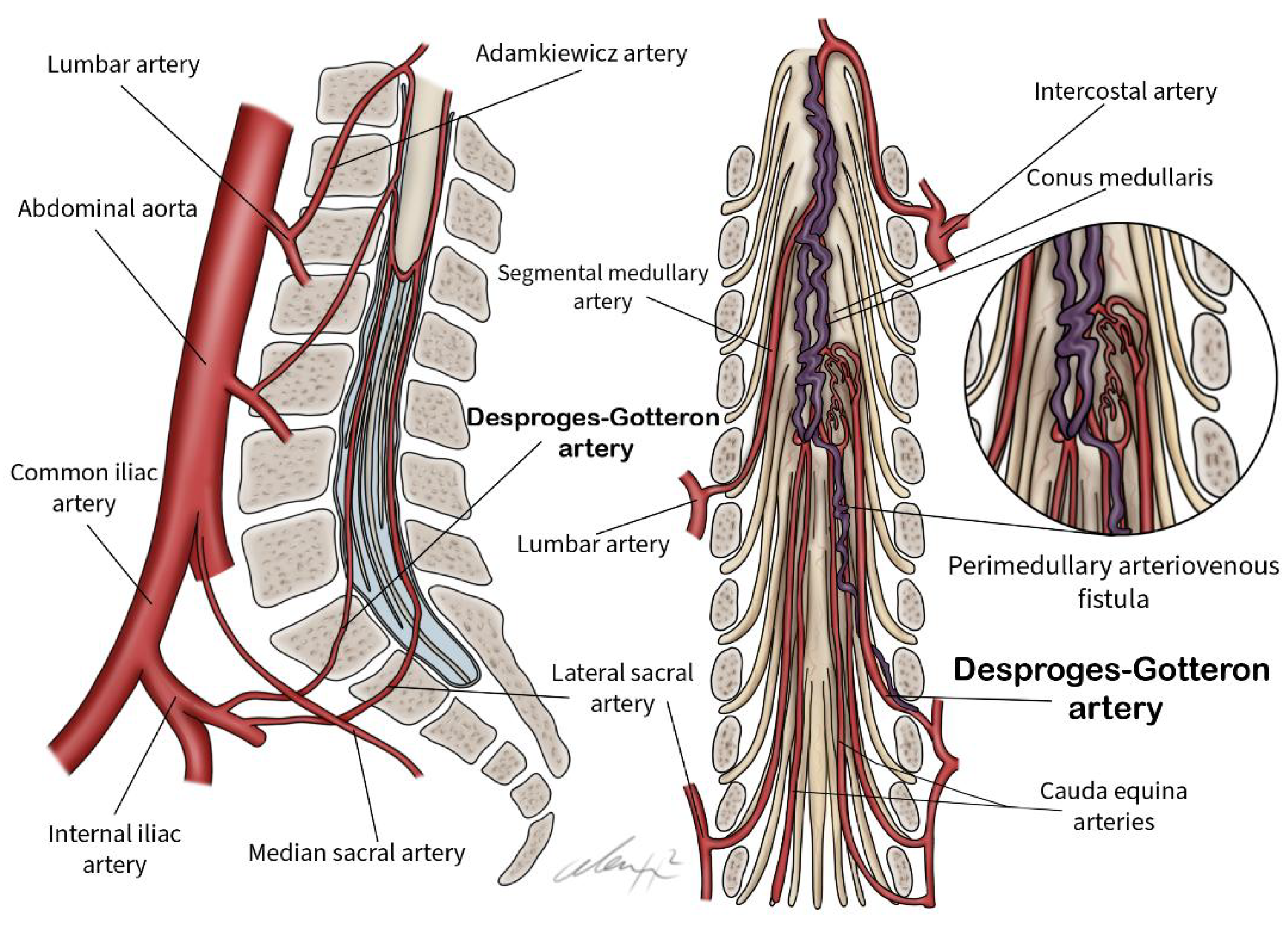

The ADG originates from the internal iliac or iliolumbar arteries and extends to the conus medullaris, providing a critical vascular link within the complex anatomical landscape of the conus medullaris and cauda equina [

3]. Rarely, the ADG may serve as a feeding artery for spinal perimedullary arteriovenous fistulas (PAVFs), which are uncommon arteriovenous shunts [

3]. Typically, the thoracolumbar radiculomedullary artery predominantly supplies PAVFs in this region. The ADG is often missed in the absence of spinal angiography, particularly when it is in close proximity to the contralateral iliac artery. A thorough understanding of the anatomical branches of the common iliac artery and the incidental finding of the ADG is essential for its preservation and prevention of complications such as conus medullaris syndrome.

The aim of this review is to examine the ADG, including its anatomy, variations and clinical significance.

2. Methodology

This narrative review used a comprehensive approach to evaluate the available literature on ADG. Relevant resources were retrieved from PubMed, ScienceDirect and Web of Science databases. Inclusion criteria required that the full text of the studies was publicly available. Non-full text components were excluded. The terminologies used in the study were 'Desproges-Gotteron artery', 'cone artery' and 'radiculomedullary arteries'.

During the preliminary screening phase, we reviewed the titles and abstracts of the studies to determine eligibility based on predefined criteria. Two separate authors conducted a thorough review after removing duplicates and determining whether publications met the criteria. Full articles were retrieved. In areas of controversy, we sought the final judgement of the third review author. After an extensive screening process, eight articles were identified as eligible. We identified eight publications that discussed the anatomical variations and neurosurgical applications of the ADG. This review considered the anatomical location, association with conus medullaris syndrome and functional anatomy of the ADG. The importance of these arteries in neurosurgical procedures such as tumour removal and arteriovenous malformations was explored, particularly the need to sacrifice them during surgery. We found 43 articles by searching three databases. Based on titles and abstracts that suggested apparent ineligibility, 35 of the publications were deemed ineligible and were therefore excluded. After independently assessing each of the remaining 8 publications, two researchers decided which were eligible for inclusion in the study. Eight articles met the inclusion criteria and examined the clinical significance of the ADG in relation to associated spinal pathologies. We identified 8 case reports and reported the clinical significance of the cases identified. The articles included were published between 1955 and 2025.

3. Anatomy and Anatomical Significance

The vascular supply to the spinal cord is derived from three major arteries: the anterior spinal artery and two posterior spinal arteries, which collectively ensure perfusion to the spinal cord. Specifically, the posterior spinal arteries supply the posterior third of the spinal cord, while the anterior spinal artery supplies the anterior two-thirds of the spinal cord [

4,

5].

3.1. Segmental Medullary Arteries

The segmental medullary arteries (or radiculomedullary arteries) function as critical feeders that originate from the radicular arteries. These vessels are particularly prominent in the lower cervical, lower thoracic, and upper lumbar regions, ensuring adequate perfusion to corresponding sections of the spinal cord. Among these, the AKA is the most significant radiculomedullary artery. It is predominantly located in the thoracolumbar region (between T8 and L2) in approximately 75% of individuals [

4]. The posterior segmental medullary arteries, numbering between 10 and 23, cross medially through the intervertebral foramina to supply the posterior roots of the spinal cord [

5].

3.2. Posterior Segmental Medullary Artery

The posterior segmental medullary artery contributes to the vascular supply by anastomosing with the posterior spinal arteries at the posterolateral sulcus of the spinal cord [

6]. It has no direct branches and primarily supplies the posterior roots, rootlets, and spinal ganglia. Notably, this artery has been implicated in the pathophysiology of ischemic nerve injury [

7,

8].

Both the segmental medullary arteries and the posterior segmental medullary arteries serve critical functions in supplying blood to the spinal cord. The ADG enhances this vascular supply, particularly to the distal regions of the spinal cord. Through the anastomosis of the posterior segmental medullary arteries with the posterior spinal arteries, the ADG's role in the vascularization of the conus medullaris is further amplified.

3.3. The Artery of Desproges-Gotteron

The ADG, also referred to as the “cone artery”, is a posterior radiculomedullary (radiculopial) artery. It arises from the internal iliac artery or one of its branches, such as the iliolumbar artery, at the L2 to L5 level (

Figure 1). However, in certain individuals, it may be absent [

9,

10]. The ADG has a diameter ranging from 0.5 to 1.2 mm and ascends along the L5 or S1 nerve root.

Although rare, the ADG plays a critical role in contributing to the perimedullary vascular network, also known as the “conal basket”, which supplies the conus medullaris and surrounding dura. It achieves this by forming branches that connect to the pial plexus via the L5 or S1 nerve root. Despite its clinical relevance, particularly in vascularizing the distal spinal cord, the ADG’s unique branching patterns have been infrequently studied [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

Understanding the basic vascular architecture of the spinal cord is essential for imaging interpretation, as well as endovascular and surgical treatment of spinal cord vascular disorders. Diagnostic and treatment approaches have evolved, demanding a more thorough and detailed understanding of the spinal cord's microvasculature. Attention to the anatomical features of the spinal cord's circulatory supply, in particular, enables more personalized patient care.

4. Pathology

In this study, the primary pathologies associated with ADG were identified as arteriovenous fistula (AVFs), which were present in 62.5% of the patients, and lumbar disc prolapse, impacting 25% of individuals (

Figure 2). Notably, three patients, representing 37.5% of the study population, exhibited symptoms indicative of cauda equina syndrome. In contrast, the remaining patients presented with a combination of motor weakness and sphincter dysfunction. These findings underscore the diverse clinical manifestations linked to these conditions and highlight the critical importance of early detection and intervention, particularly among patients exhibiting overlapping symptoms. A thorough understanding of the prevalence and clinical implications of AVFs will be instrumental in developing targeted therapeutic strategies, ultimately enhancing patient outcomes.

5. Neurosurgical Relevance

Advanced diagnostic imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography angiography are fundamental to the preoperative evaluation of vascular structures, including the ADG. These modalities provide detailed insight into the arterial architecture and facilitate precise surgical planning. Although intraoperative imaging modalities such as fluoroscopy, computed tomography and contrast-enhanced radiography have been used to guide injections and minimise the risk of complications such as ischaemia or fibrocartilaginous embolism, their use does not guarantee the avoidance of ischaemic complications [

16]. Understanding the architecture of the common iliac artery and its branches is essential to reduce complications such as haematoma, arterial dissection or ischaemia. This anatomical knowledge is particularly important in distinguishing arterial haemorrhage caused by ADG injury from other causes, especially in cases such as conus medullaris syndrome. Despite these precautions, Meyer et al. suggested that fibrocartilaginous embolism, which could result from disc rupture by injection needles, remains a potential risk of anterior spinal artery occlusion [

17]. Although pre-injection imaging is an important safety measure, it cannot completely eliminate this risk.

Surgical interventions are tailored to the underlying pathology, with endovascular techniques used in 50% of cases in our study, demonstrating their efficacy in treating vascular anomalies and malformations. These minimally invasive approaches reduce perioperative risks and improve recovery. In the 25% of patients with acute disc prolapse that compromises vascular supply, surgical discectomy effectively relieves compression and restores vascular integrity. Management of tumours and arteriovenous malformations often involves preoperative embolization or intraoperative occlusion of feeding arteries, such as an enlarged ADG, to minimise intraoperative blood loss and facilitate safer excision or closure. Microsurgical disconnection or endovascular devascularisation further enhances the safety and efficacy of these procedures [

3,

11,

12,

18,

19]. Complex cases involving malignancy and vascular anomalies in the lumbosacral region may require extended posterior or combined approaches where strategic or occlusion of the ADG limits blood supply to tumours or lesions. Pre-operative imaging and neuronavigation are essential to minimise risks such as arterial puncture or injury during surgery, although anatomical variations as described by Desproges-Gotteron [

1] may still lead to ischaemic events despite meticulous planning [

20]. Maintaining a clear surgical path and avoiding displacement of disc material into vascular structures are essential measures to further reduce complications.

Table 1 highlights eight studies that provide comprehensive information on ADG.

6. Study Limitations

Due to the extremely rare incidence of ADG, the sample size of available case reports of lesions involving this artery is extremely small. The analysis was further limited by the small sample size and the variable data, making the statistical robustness questionable. A more thorough analysis would be possible with a larger sample. Our review findings were further limited by the paucity of reported outcomes and individualised data from the included literature. Extensive cadaveric dissections should be performed to improve the understanding of ADG and its clinical significance.

7. Conclusions

In conclusion, the ADG appears to be an intriguing vascular structure with specific neurosurgical implications, offering possible routes for numerous therapies, particularly in the area of the conus medullaris. The ADG has received attention for its function in supplying the conus medullaris, thanks to thorough anatomical research and dissection techniques. Understanding the differences and clinical implications of the ADG is fascinating for neurosurgeons and highlights the importance of assessment and specific knowledge in microvascular anastomosis. As we continue to explore the complexities of surgical anatomy, a thorough understanding of the architecture of the ADG may aid in the effective management of conus medullaris lesions.

Ethical Approval

There was no ethical approval required for this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

All the authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Abbreviations

AKA: Adamkiewicz Artery, ADG: Artery of Desproges-Gotteron, AVF: Arteriovenous Fistula, PAVF: Perimedullary Arteriovenous Fistula

References

- Desproges-Gotteron R. Contribution to the study of paralytic sciatica.Paris: University of Paris; 1955.

- Tubbs RS, Mortazavi MM, Denardo A, Cohen-Gadol AA. Arteriovenous malformation of the conus supplied by the artery of Desproges-Gotteron. J Neurosurg. 2011.

- Wang Y, Yu J. Spinal perimedullary arteriovenous fistula supplied by the artery of Desproges-Gotteron: A case report with literature review. Medicine International. 2021;2(1):1. [CrossRef]

- Perez VH, Hernesniemi J, Small JE. Anatomy of the great posterior radiculomedullary artery. Am J Neuroradiol. 2019;40(11):2010-5.

- Duarte Armindo R, Vilela P. What the musculoskeletal radiologist needs to know about the vascular anatomy of the spine and spinal cord. Semin MusculoskeletRadiol. 2023;27:580-7.

- Williams PL, Bannister LH, Berry MM, Collins P, Dyson M, Dussek JE, Ferguson MWJ. Gray’s anatomy: the anatomical basis of medicine and surgery. 38th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1995. p. 1560.

- Jones HR, Burns T, Aminoff MJ, Pomeroy S. The Netter collection of medical illustrations: nervous system. Vol. 7, Part 1 - Brain e-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2013.

- Etz CD, Kari FA, Mueller CS. The collateral network concept: a reassessment of the anatomy of spinal cord perfusion. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141(4):1020-8. [CrossRef]

- Santillan A, Nacarino V, Greenberg E, Riina HA, Gobin YP, Patsalides A. Vascular anatomy of the spinal cord. J Neurointerv Surg. 2012;4:67-74. [CrossRef]

- Vargas MI, Gariani J, Sztajzel R, Barnaure I, Delattre BM, Gascho D, et al. Spinal cord ischemia: practical imaging tips, pearls, and pitfalls. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36:825-30. [CrossRef]

- Bishwas S, Islam MS, Shiplu MH, Rana MS, Ashfaq M, Rashid M, Alam F. Arteriovenous malformation of conus medullaris fed by the artery of Desproges-Gotteron. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2022;13(3):550-553. [CrossRef]

- Munich SA, Krishna C, Cress MC, Dhillon GS, Pollina J, Levy EI. Diagnosis and endovascular embolization of a sacral spinal arteriovenous fistula with “holo-spinal” venous drainage. World Neurosurg. 2019;128:328-332. [CrossRef]

- Reis C, Rocha JA, Chamadoira C, Pereira P, Fonseca J. Foraminal L5-S1 disc herniation and conus medullaris syndrome: a vascular etiology? Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2007;149(5):533-535. [CrossRef]

- Balblanc JC, Pretot C, Ziegler F. Vascular complication involving the conus medullaris or cauda equina after vertebral manipulation for an L4-L5 disk herniation. Rev Rhum Engl Ed. 1998;65(4):279-282.

- Zinchenko AP, Kaplan IB. K klinikediskogennykhishemicheskikhinsul’tov v basseĭnenizhneĭdopolnitel’noiradikulomedulliarnoiarterii (arteriiDeprozh-Gotterona [The clinical picture of diskogenic ischemic strokes in the bassin of the inferior accessory radiculo-medullary (Desproges-Gotteron)]. ZhNevropatolPsikhiatrIm S SKorsakova. 1973;73(1):8-11.

- Wybier M. Transforaminal epidural corticosteroid injections and spinal cord infarction. Joint Bone Spine. 2008;75(5):523-525. [CrossRef]

- Meyer HJ, Monticelli F, Kiesslich J. Fatal embolism of the anterior spinal artery after local cervical analgetic infiltration. Forensic Sci Int. 2005 May 10;149(2-3):115-9. PMID: 15749350. [CrossRef]

- Cohen JE, Constantini S, Gomori JM, Benifla M, Itshayek E. Pediatricperimedullary arteriovenous fistula of the conus medullaris supplied by the artery of Desproges-Gotteron. J NeurosurgPediatr. 2013;11(4):426-430. [CrossRef]

- Patchana T, Savla P, Taka TM, Ghanchi H, Wiginton J 4th, Schiraldi M, Cortez V. Spinal arteriovenous malformation: Case report and review of the literature. Cureus. 2020;12(11):e11614. [CrossRef]

- Huntoon MA. Anatomy of the cervical intervertebral foramina: vulnerable arteries and ischemic neurologic injuries after transforaminal epidural injections. Pain. 2005;117:104-11.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).