1. Introduction

In higher education, there has been a growing shift away from passive learning approaches, such as traditional lectures, towards active learning strategies that promote student engagement and deeper cognitive involvement [

1,

2,

3]. Multiple studies demonstrate that active learning approaches consistently improve knowledge acquisition, skill development, engagement, motivation, and knowledge retention compared to passive methods [

1,

2,

3]. The flipped classroom (FC), in which students interact with content independently before class and apply their understanding collaboratively during in-person sessions, has gained particular traction [

4], as well as, in anatomy learning [

5]. This approach encourages students to engage with core content independently before class, thereby maximizing in-person sessions for applied learning, peer interaction and instructor-led clarification [

6,

7]. This method is effective because it fosters student autonomy, deepens conceptual understanding and enhances academic performance, particularly in subjects requiring strong foundational knowledge and spatial reasoning, such as veterinary anatomy [

7]. Within this pedagogical framework, the integration of digital tools has become increasingly relevant [

8].

Understanding how students engage with digital learning resources provides valuable insights into the effectiveness of instructional design [

4,

9]. Understanding student engagement as the emotional, behavioral, and cognitive involvement a student exhibits during the learning process [

9]. Metrics such as video visualization frequency, time spent on pre-class preparation and classroom attendance reveal behavioral trends and underlying study habits and cognitive engagement. In time-constrained curricula, optimizing learning efficiency depends on aligning the time students spend preparing with the cognitive demands of the course materials. This remains a challenge in FC models, where it is crucial to ensure that students have sufficient time and resources for meaningful engagement before class [

10,

11].

In FC, the time students dedicate to reviewing materials before face-to-face sessions directly affects the depth and quality of their engagement in class [

4,

12]. In flipped and blended learning environments, the connection between pre-session content and in-class activities is a cornerstone of effective instructional design. When students do not adequately engage with preparatory materials—or when those materials are poorly aligned with classroom tasks—the resulting gap can hinder knowledge construction and reduce learning efficacy [

13].

When pre-session resources, such as interactive H5P videos, are designed efficiently and clearly and are aligned with cognitive goals, they maximize the impact of limited preparation time [

11]. This is particularly important in intensive curricula, where students must balance their workload with developing a deep conceptual understanding. Effective pre-class preparation enables learners to participate actively in problem-solving and collaboration. However, if the materials are poorly structured or overly time-consuming, students may either underprepare or rely on passive review strategies, which limits the effectiveness of classroom activities. Conversely, when digital content is concise, engaging and tailored to support specific learning objectives, it promotes timely revision and cognitive priming, making the most of in-person instruction [

14]. Ultimately, aligning the design of pre-session materials with realistic student time constraints ensures that independent study is both manageable and meaningful, creating a strong foundation for successful face-to-face learning experiences. By tracking video visualization, educators can determine which content is revisited, which segments are skipped and how frequently learners interact with materials outside the classroom. A high frequency of views may indicate high motivation, or that the content is complex and requires deeper review. Time spent preparing, particularly when measured across specific intervals before class (e.g. one day versus several days prior), offers clues about self-regulated learning and procrastination patterns. When paired with performance data, this metric can show whether earlier engagement translates into better comprehension and retention outcomes. Although traditional, classroom attendance still holds diagnostic value. Consistent attendance often indicates student accountability and active participation. When these metrics are considered together, educators can assess whether their instructional model — such as flipped learning or blended formats — effectively promotes autonomy, reflection and collaboration. Leveraging these data points enables educators to refine their teaching strategies, adapt their pace and design interventions that better support diverse learning needs in technology-enhanced environments.

This study focuses on the implementation of flipped learning within the respiratory and cardiovascular systems modules of the Anatomy and Embryology I course for first-year Veterinary Medicine students. Conducted during the 2023/24 and 2024/25 academic years, the study aims to evaluate how much time students dedicate to independent study and to explore its impact on learning outcomes. Particular attention is given to attendance patterns, how students access content, and their feedback via integrated digital platforms. Comparing the two academic years also allows us to examine how evaluation models, such as the introduction of continuous assessment in the second year, may influence engagement and performance. Platforms such as H5P and Wooclap offer interactive, trackable content delivery systems that support formative assessment and learner feedback [

15,

16].

3. Results

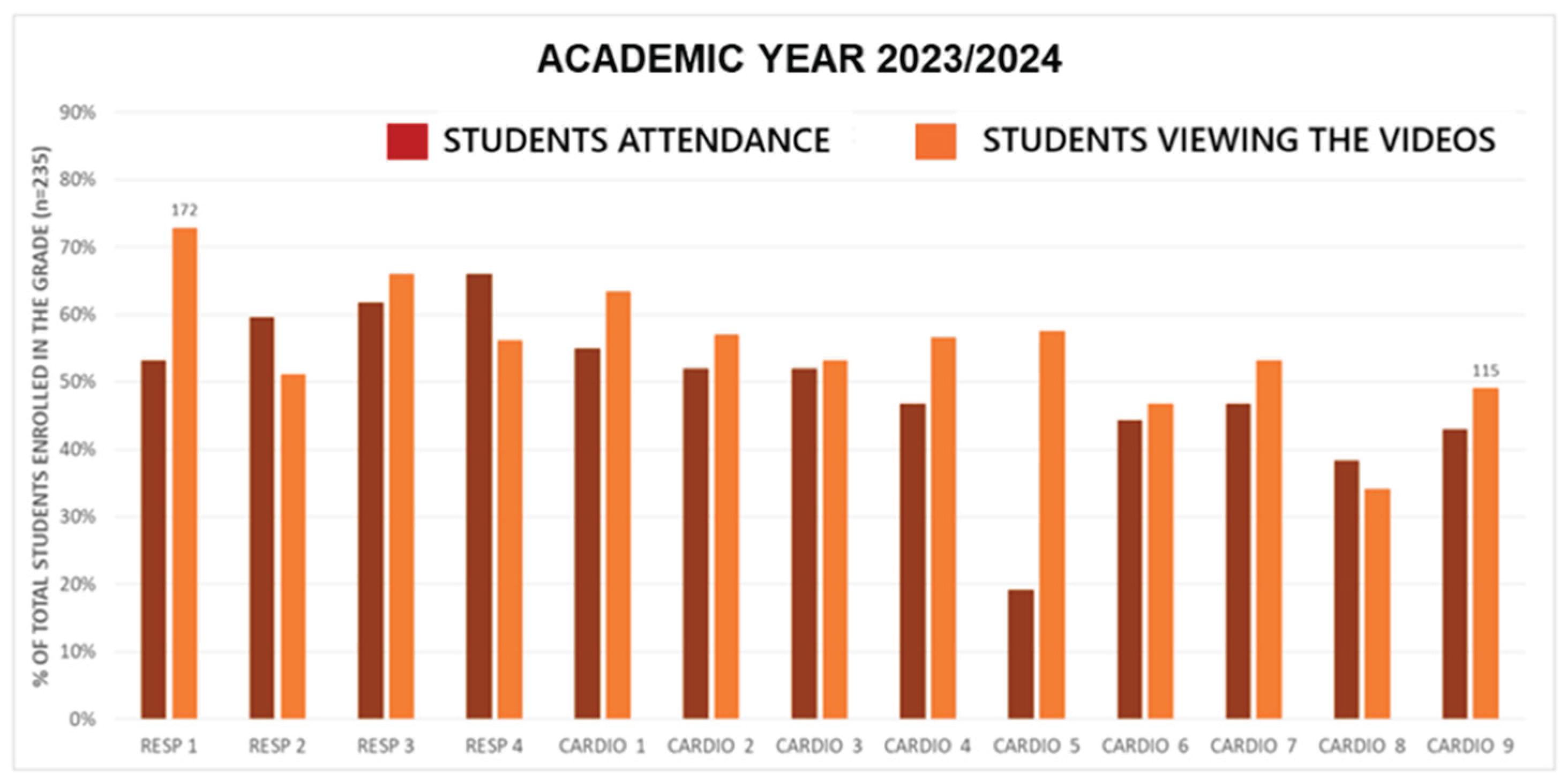

A comparison of student attendance and video viewing in academic years 2023/24 and 2024/25 is presented in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

This figure illustrates student engagement across a series of respiratory (RESP 1–4) and cardiovascular (CARDIO 1–9) sessions during the 2023/24 academic year. Two metrics are compared for each session: student attendance and student video viewing. The y-axis represents the percentage of total enrolled students (n = 235), while the x-axis lists each session chronologically.

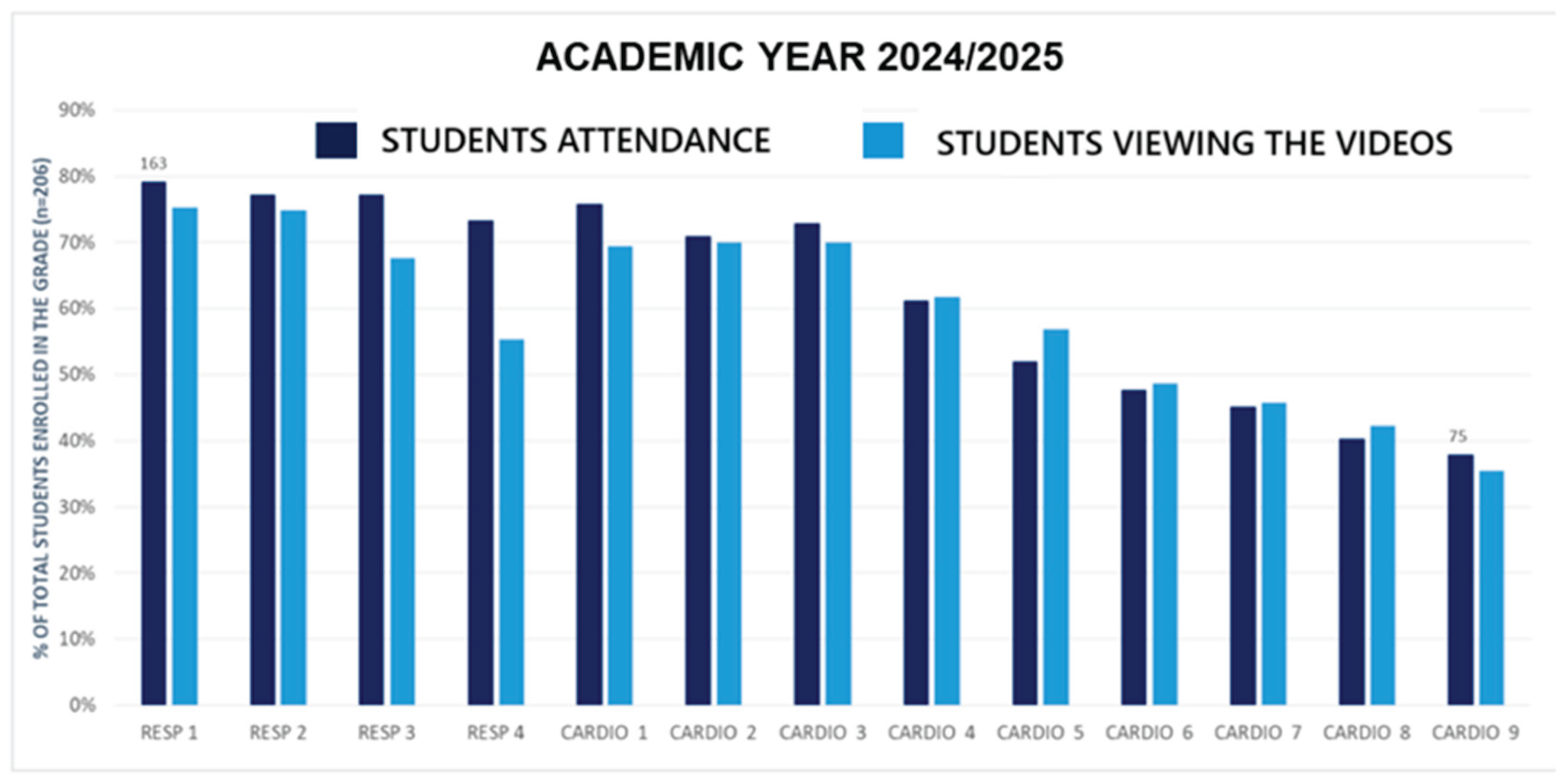

This figure shows how students engaged with respiratory (RESP 1–4) and cardiovascular (CARDIO 1–9) sessions during the 2024/25 academic year. Two metrics are visualized for each session: student attendance and student video viewing. The y-axis shows the percentage of enrolled students (n = 208) and the x-axis lists the sessions in chronological order.

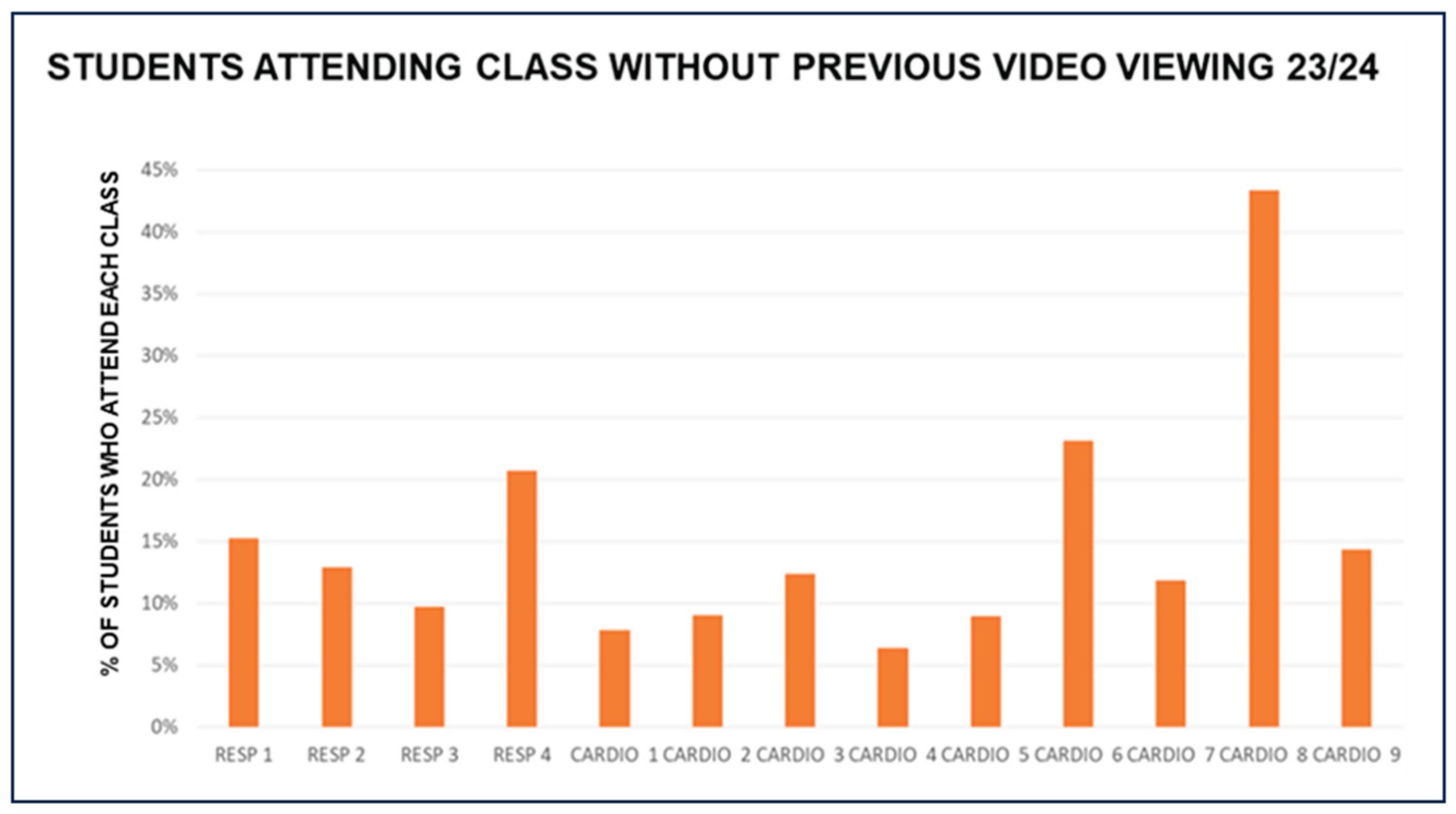

In

Figure 3 and

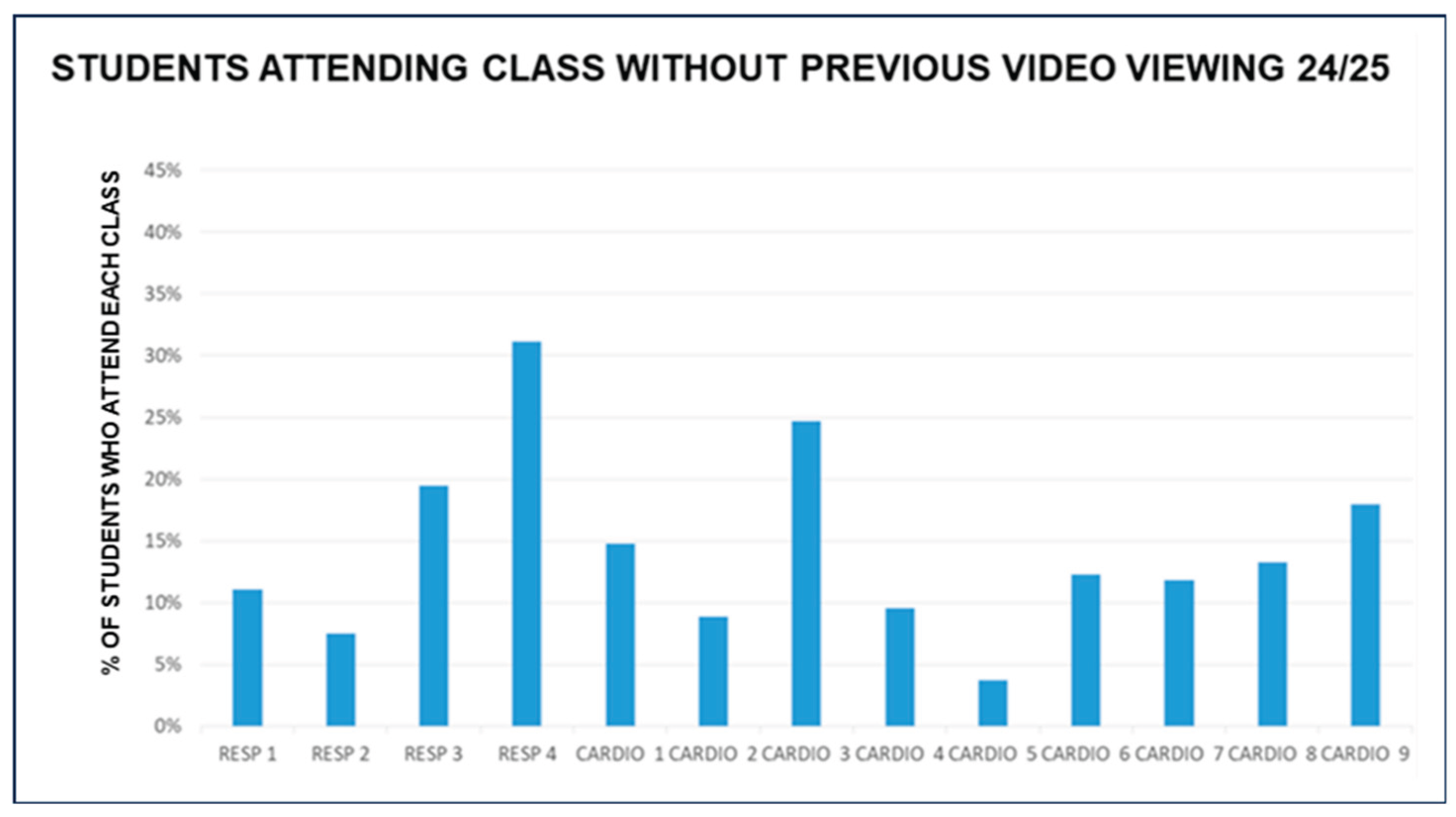

Figure 4, a comparison of student attendance and/or video viewing in academic years 2023/24 and 2024/25 is presented.

This figure shows the percentage of students who attended each face-to-face class without viewing the relevant preparatory video beforehand during the 2023/24 academic year. The sessions are categorized by respiratory (RESP 1–4) and cardiovascular (CARDIO 1–9) topics and are displayed along the x-axis. The y-axis shows the proportion of students who attended each session without having watched the preparatory video beforehand.

This figure shows the percentage of students who attended each face-to-face class without watching the preparatory video beforehand during the 2024/25 academic year. The sessions are organized by topic — respiratory (RESP 1–4) and cardiovascular (CARDIO 1–9) — along the x-axis. The y-axis shows the proportion of students who attended each session without having watched the preparatory video beforehand.

In

Figure 5 and

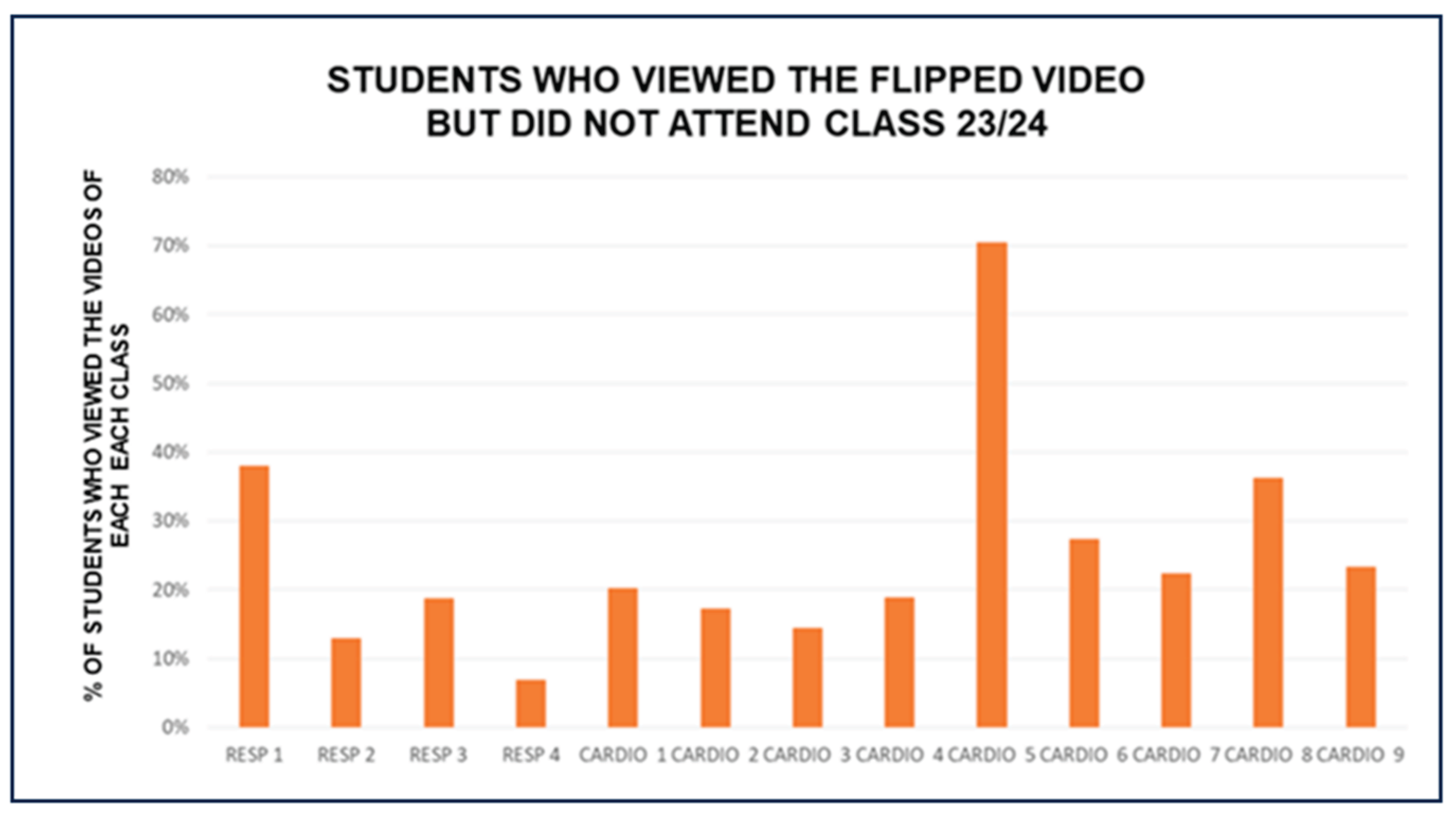

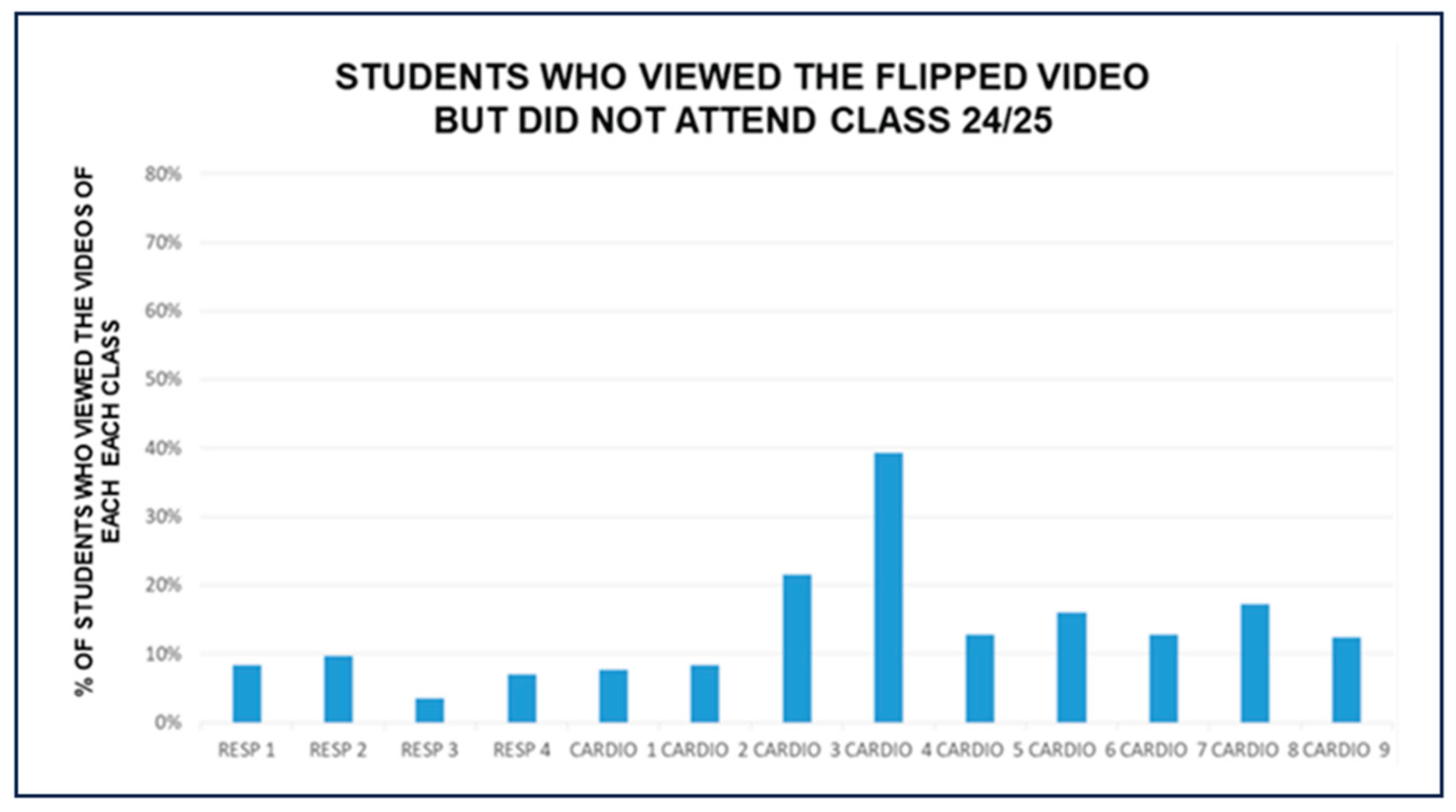

Figure 6, a comparison of student attendance and/or video viewing in academic years 2023/24 and 2024/25 is presented.

This bar graph shows the proportion of students who watched the recorded flipped classroom videos but did not attend the corresponding live sessions for the RESP and CARDIO modules.

This bar chart shows the proportion of students who watched the flipped classroom videos but did not attend the corresponding live sessions for the RESP and CARDIO modules.

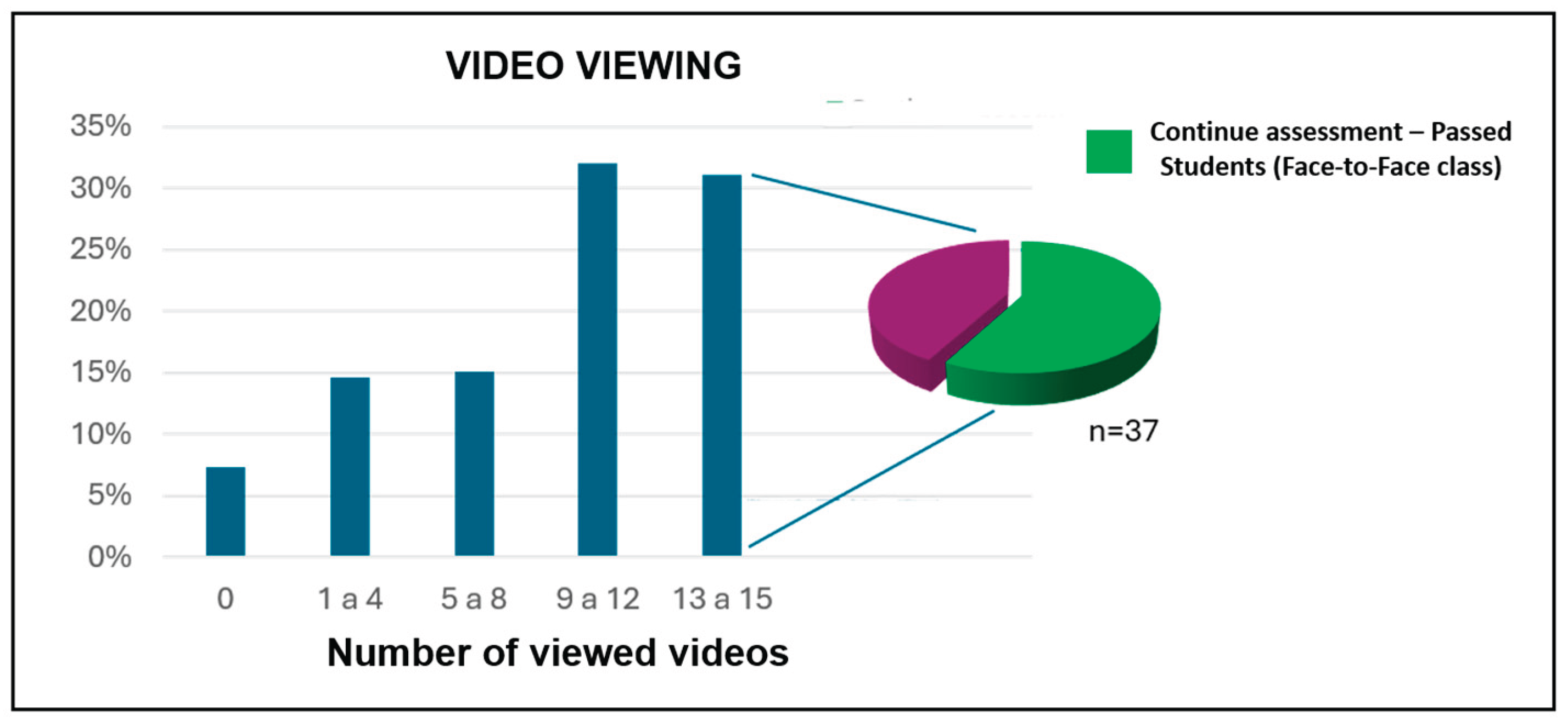

Figure 7.

Number of Videos Viewed by Students in Academic Year 2024/25, (including those who passed continuous assessment).

Figure 7.

Number of Videos Viewed by Students in Academic Year 2024/25, (including those who passed continuous assessment).

The bar chart displays the distribution of students based on the number of flipped classroom videos viewed, categorized into five viewing ranges. The majority of students watched between 9 and 15 videos, with each of the top two categories (9–12 and 13–15 videos) comprising approximately 30% of the cohort. The pie chart illustrates assessment outcomes, showing that a substantial portion of students who continued with the assessment successfully passed the face-to-face class.

Table 1.

Comparison of student video access patterns in academic year 2023/24 and 2024/25.

Table 1.

Comparison of student video access patterns in academic year 2023/24 and 2024/25.

| Student Video Access Patterns Prior to Class |

|---|

| Academic Year |

Accessed 0-1 Days Before Class |

Accessed 2-3 Days Before Class |

Accessed 4-5 Days Before Class |

Number of Students |

| 2023/2024 |

RESP |

29,87% |

8,25% |

12,12% |

153 |

| CARDIO |

38,82% |

6,88% |

4,44% |

122 |

| TOTAL |

36,07% |

7,40% |

6,80% |

132 |

| 2024/2025 |

RESP |

29,37% |

8,75% |

8,5% |

140 |

| CARDIO |

18,27% |

10,27% |

8,33% |

114 |

| TOTAL |

21,69% |

9,80% |

8,38% |

122 |

This table summarizes when students had access to preparatory video materials in the days leading up to face-to-face classes across two academic years (2023/24 and 2024/25). The data is divided by topic — respiratory (resp) and cardiovascular (cardio) — and includes a combined total for each year.

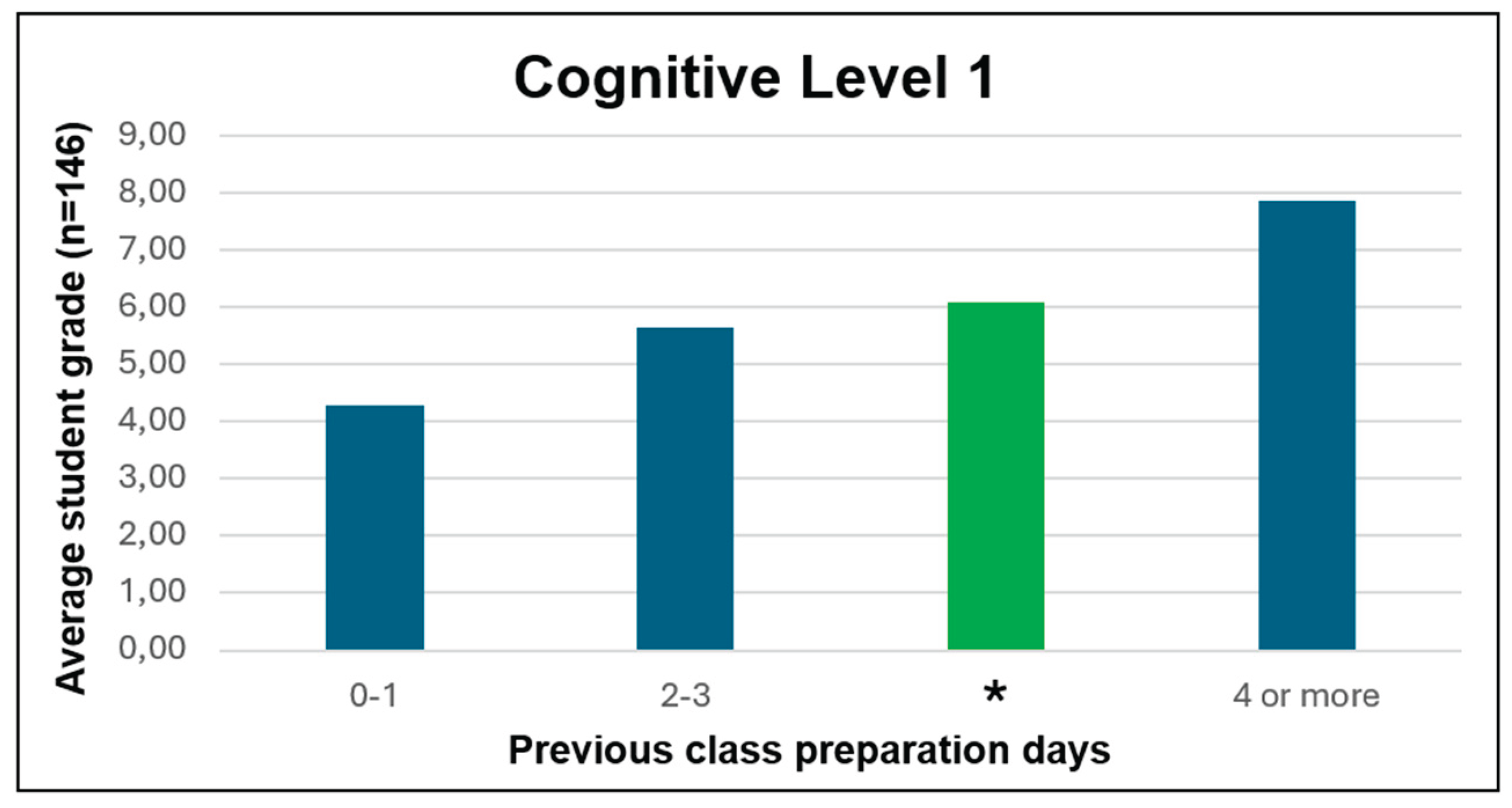

Figure 9.

Correlation Between Preparation Time and Performance on Cognitive Level 1 Questions: Academic Year 2024/25. * Students who passed the continuous assessment.

Figure 9.

Correlation Between Preparation Time and Performance on Cognitive Level 1 Questions: Academic Year 2024/25. * Students who passed the continuous assessment.

This bar chart shows how the number of days that students spent preparing for class correlates with their average grade.

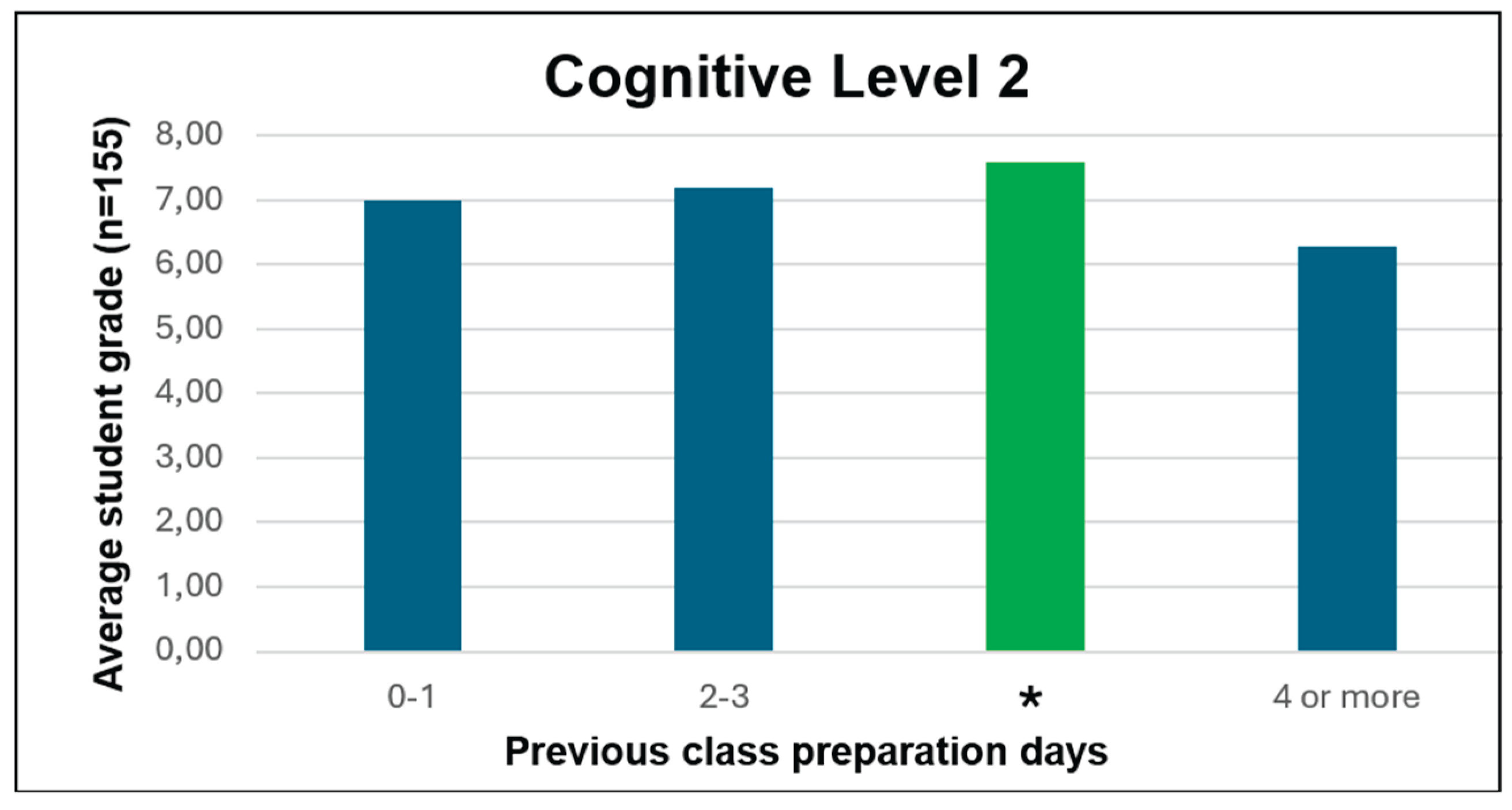

Figure 10.

Correlation Between Preparation Time and Performance on Cognitive Level 2 Questions: Academic Year 2024/25. * Students who passed the continuous assessment.

Figure 10.

Correlation Between Preparation Time and Performance on Cognitive Level 2 Questions: Academic Year 2024/25. * Students who passed the continuous assessment.

This bar graph illustrates the relationship between how many days students spent preparing for class and their average grade at Cognitive Level 2.

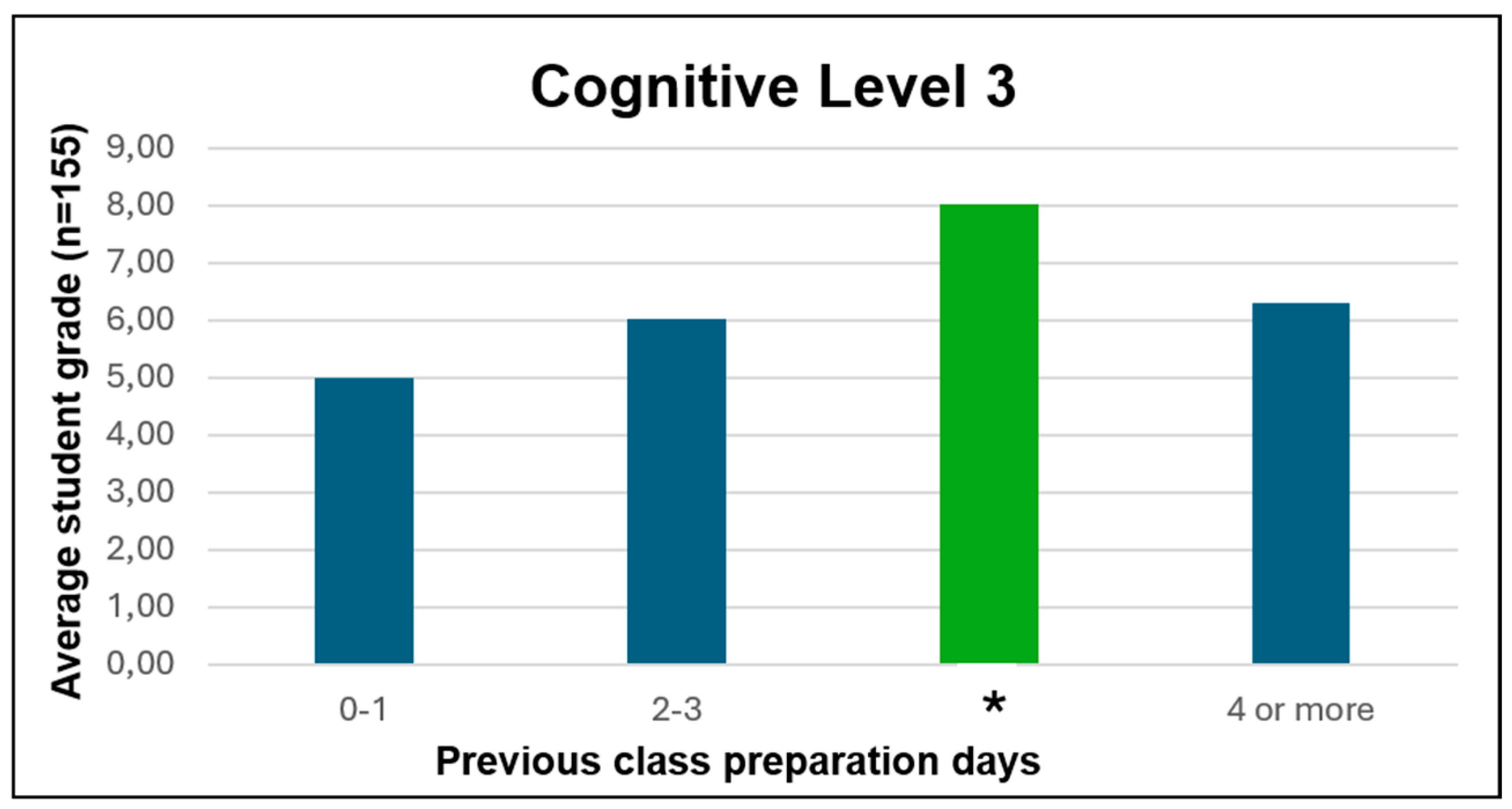

Figure 11.

Correlation Between Preparation Time and Performance on Cognitive Level 3 Questions: Academic Year 2024/25. * Students who passed the continuous assessment.

Figure 11.

Correlation Between Preparation Time and Performance on Cognitive Level 3 Questions: Academic Year 2024/25. * Students who passed the continuous assessment.

This bar graph illustrates how the number of days students prepared before class correlates with their performance at Cognitive Level 3.

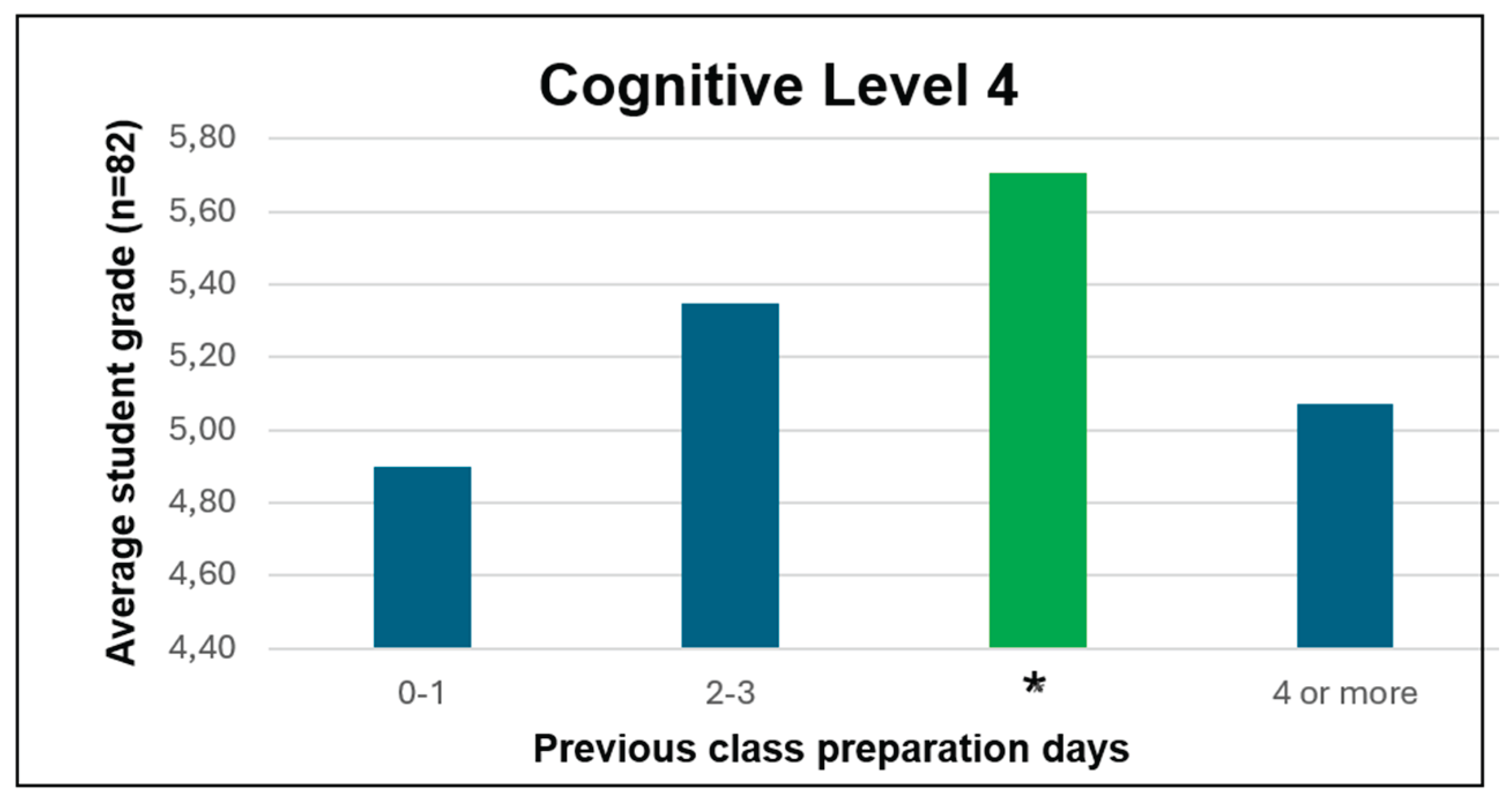

Figure 12.

Correlation Between Preparation Time and Performance on Cognitive Level 4 Questions: Academic Year 2024/25. * Students who passed the continuous assessment.

Figure 12.

Correlation Between Preparation Time and Performance on Cognitive Level 4 Questions: Academic Year 2024/25. * Students who passed the continuous assessment.

This bar graph illustrates the relationship between how many days students spent preparing for class and their average grade at Cognitive Level 4.

The survey investigated students' preparation time for flipped videos and use of extra study time. Key findings include:

These results indicate a shift toward more intensive preparation and active note-taking in 2024/25, likely influenced by the integration of continuous assessment and graded cognitive tasks.

4. Discussion

In the FC model, students are assigned didactic materials to study independently before class. This allows face-to-face sessions to focus on active learning strategies, such as discussions and problem-solving activities [

4,

7,

8,

16]. Active learning methods such as problem-based learning (PBL) and team-based learning (TBL) are also recognized as effective ways of promoting collaboration and critical thinking among students [

4,

15,

18,

19,

20,

21]. The effective implementation of the FC model relies on backward instructional design, beginning with the definition of clear learning objectives, followed by the development of assessments and the selection of appropriate teaching methods [

4,

7]. This study used questions designed at varying cognitive levels to quantify assessment, allowing for a structured evaluation of student learning across a range of competencies [

17]. In this study, the FC model fostered a constructivist learning environment in which students actively constructed knowledge by integrating new information with their prior understanding. This process was facilitated through interactions with peers, digital tools such as H5P® and Wooclap®, and various components of the learning environment. As described by other authors [

22,

23,

24,

25], this dynamic engagement—both inside and outside the classroom—supports deeper cognitive processing and promotes more meaningful learning experiences.

Constructivist teaching emphasizes the importance of engaging students in active learning through meaningful tasks that encourage critical thinking, exploration of ideas, and problem solving, all of which are supported by easily accessible information resources [

26,

27,

28]. Our observations align with these findings, highlighting the potential of flipped learning to enhance student-centered, active learning. Students responded positively to these opportunities, demonstrating increased autonomy and engagement as they tackled problem-solving tasks and reflected on key concepts using the available digital resources. This was evident in the significant increase in class attendance during the CARDIO 8 session, in which Problem-Based Learning (PBL) was the primary study method, despite the absence of prior video viewing. This emphasizes the importance of engagement and interest in problem solving, as well as the role of prior knowledge, high levels of self-direction and motivation [

29,

30].

A key aspect of planning the flipped experience is understanding the time required for independent study [

4]. Educators must accurately estimate and clearly communicate the expected time commitment for engaging with pre-class materials. Providing an online schedule and ensuring that learning resources are easily accessible and user-friendly can support this process. In some institutions, dedicated preparation time is formally reserved in student schedules [

4]. To ensure that students are adequately prepared for active learning in class, it is essential to monitor and manage the time allocated for preparation outside of class. Effective planning and communication are critical to the success of the FC approach, as they help guarantee that students are ready to engage in meaningful, interactive and collaborative learning experiences from the outset [

4].

This study provides a detailed analysis of how instructional strategies and evaluation models influence student engagement and learning in flipped anatomy education, comparing the 2023/24 and 2024/25 academic years. In 2023/24, asynchronous video visualization surpassed in-person attendance, suggesting that students gravitated towards flexible study habits that supported autonomy and schedule management. However, this preference may also have reflected the absence of structured accountability mechanisms in the design of that year. Conversely, in 2024/25, a more balanced dynamic emerged, with in-person attendance surpassing video views in several sessions. This shift is likely due to the introduction of continuous assessment, whereby students were required to complete graded cognitive exercises in class, thereby reinforcing the importance of attendance and participation. Notably, both academic years showed significant drops in attendance around exam periods for other subjects. However, the behavioral responses differed: in 2023/24, students replaced class attendance with video viewing during peak exam times, whereas in 2024/25, they continued to prioritize attendance. This distinction suggests a stronger perception of instructional value when face-to-face sessions are relevant to assessments — a design choice that enhances motivation and reduces disengagement during academically stressful periods.

Engagement data from the H5P platform offers deeper insight into how the timing of video access correlates with cognitive performance. Students were grouped into three preparation categories: viewing 1 day before class, viewing 2–3 days prior, and viewing 4 or more days ahead. For cognitive levels 1 and 2, earlier preparation directly improved performance, consistent with the principles of spaced repetition and memory consolidation. However, at cognitive level 3, performance gains were more uniformly distributed across the 2–3 day and 4+ day ranges, suggesting that analytical tasks rely less on preparation time and more on the ability to transfer and interpret knowledge.

The FC model is presented as a transformative approach to medical education, enabling competency development, interprofessional collaboration, and lifelong learning skills. It requires careful planning, technology integration, and change management to be effective [

4]. One critical behavioral outcome observed when implementing FC methodologies, particularly those incorporating interactive tools such as H5P, is the prevalence and evolution of student procrastination. This phenomenon was monitored across two academic cohorts using two key curricular checkpoints: the respiratory system unit, which marked students' initial exposure to the flipped model, and the cardiovascular system unit, which occurred after students had gained experience with the approach.

During the 2023/24 academic year, flipped instruction was introduced without continuous evaluation during in-person sessions, potentially impacting engagement habits. By the time students reached the cardiovascular unit, 33% of them had watched the preparatory videos on the day before the class session, reflecting a tendency to postpone engagement until the last moment. This figure was significantly higher than the 21.69% observed in the 2024/25 cohort, who had continuous evaluation integrated into face-to-face teaching, suggesting that regular accountability fosters more timely participation.

Trends in procrastination over time within each academic cycle further illuminate behavioral shifts. In 2023/24, the percentage of students demonstrating procrastination behavior increased substantially, rising from 29.87% during the respiratory unit to 47.99% during the cardiovascular unit. This suggests that, in the absence of sustained evaluative reinforcement, procrastination became increasingly normalized. By contrast, in 2024/25, 51.5% of students initially procrastinated, but this figure dramatically declined to 18.28% as the course progressed, indicating a reverse pattern in which familiarity with the flipped model, coupled with continuous feedback, may have helped to reshape study habits. Marshall et al. (2022) [

11] emphasized that procrastinating over pre-session work greatly reduced students' engagement during active learning sessions.

These findings highlight the importance of continuous evaluation and structured follow-up in flipped learning environments. Without regular in-class check-ins or graded incentives tied to video preparation, students — particularly in asynchronous learning settings — appear more prone to delaying engagement. Other authors [

31,

32] suggest that students often access online materials just before classes or exams, reflecting habits from traditional, lecture-based courses. This raises questions about whether this 'just-in-time' learning stems from an intentional strategy or poor time management. This issue may either support the flexibility of the flipped classroom model or reinforce procrastination. Integrating interactive H5P activities with clear expectations and regular assessments may effectively counteract procrastination, encouraging students to adopt more proactive and consistent learning routines. Digital information resources as H5P®, integrating questions enhances interactivity and supports learning within online modules [

33]. The platform also serves as an information resource that extends beyond the timeframe of the course.

Interestingly, level 4 tasks—those requiring deeper reasoning—showed the highest scores among students who accessed content 2–3 days in advance. This timing appears optimal, giving learners sufficient time to internalize material without diluting focus through overextension. These findings support the idea that at advanced cognitive levels, the quality of engagement and strategic study routines play a greater role than duration alone. Students benefit most when content exposure is close enough to the class for recall, yet distant enough to allow for reflection and conceptual integration.

Altogether, the data underscores a fundamental shift in learning behavior when flipped instruction is supported by meaningful evaluation and interactive tools. While asynchronous resources like videos provide flexibility, they achieve their full potential only when paired with structured expectations and opportunities for active learning. In flipped anatomy education—where spatial reasoning and conceptual clarity are essential—designing instructional sequences that incorporate formative assessment, peer dialogue, and reflection is key to fostering higher-level thinking.

The survey results reveal a significant change in students' study habits over the years. While in 2023/24 nearly half of students spent only the duration of the video preparing, in 2024/25 a growing majority dedicated 30+ minutes to preparation, suggesting increased effort and deeper engagement. This transition is consistent with higher rates of note-taking and a reduced reliance on rewatching videos, indicating the adoption of more active learning strategies. The introduction of continuous assessment in the 2024/25 academic year likely played a key role in motivating students to invest more time in preparation, thereby fostering improved cognitive engagement and more meaningful interactions with flipped content.

In this study interactive and visually appealing content is used in H5P, this stimulates interest and enthusiasm [

9]. Active participation is encouraged through structured activities such as online lectures, assignments, discussions, and peer collaboration [

9]. In face to face class features like interactive simulations, problem-solving tasks, and adaptive learning paths promote deeper thinking and understanding [

9]. It is important to balance workload to ensure students had adequate time to prepare [

12]. Additionally, the introduction of continuous assessment in the 2024/25 academic year likely played a key role in motivating students to invest more time in preparation, thereby fostering improved cognitive engagement and more meaningful interactions with flipped content.

Fisher et al. (2023) [

12] observed that at the beginning of the study, students did not necessarily allocate the most study time to the most difficult content. Which indicated inefficiencies in how students prioritized their study efforts. Over time, iterative changes to instructional design helped students allocate more study time to difficult content while spending less time on familiar, easier materials. And the shift occurred without increasing the overall workload [

12]. One interesting finding of this study is the relationship between the complexity of the content and students’ attendance, regardless of prior engagement with the preparatory video. In the 2023/24 academic year, this pattern was evident in the CARDIO 5 session, which covered intracardiac circulation and the distinction between the right and left heart function— topics that may have posed challenges for students when approached independently through the preparatory video. A similar trend was observed in the 2024/25 academic year with CARDIO 4, which focused on the cardiac cycle. This suggests that higher content complexity may discourage students from relying solely on pre-class materials. Conversely, peaks in attendance without video viewing were consistently detected in both years for Resp 4, the simplest session in the respiratory block, and CARDIO 3, which covered the relatively straightforward concepts of pulmonary and systemic circulation. These patterns suggest that students may be more inclined to skip preparatory materials when the in-class content is perceived as less demanding. These findings emphasize the importance of guiding students to allocate their independent study time towards more conceptually challenging topics, ensuring that their preparation efforts are targeted effectively — what could be described as 'prep time well spent' [

12]. Without clear direction, students may prioritize easier content or underestimate the complexity of certain sessions, potentially arriving underprepared for in-depth engagement in class. This emphasizes the importance of instructors providing explicit guidance on which materials require greater attention, helping students to develop more strategic and efficient study habits within the flipped classroom model.

Survey results from the 2023/24 and 2024/25 academic years reveal a notable shift in students' preparation habits for flipped video sessions, particularly with regard to how they utilize additional study time. While nearly half of the students (48%) limited their preparation to the duration of the video in 2023/24, this figure dropped sharply to 9% in 2024/25, with 85% now dedicating an additional 30 minutes. This increase in preparation time coincides with a rise in active learning behaviors, most notably note-taking, which increased from 50% to 67%. This suggests that students are using their additional study time to engage more deeply with the content through structured note-taking, rather than merely rewatching it. This behavior reflects a shift from passive to active processing of information, which is known to enhance comprehension and retention. The decline in rewatching and researching unresolved questions may suggest that students are becoming more efficient and autonomous learners, using notes to consolidate their understanding and reducing their reliance on repeated viewing or external sources. These trends highlight the importance of encouraging intentional study strategies, such as guided note-taking, to maximize the advantages of flipped learning environments. When applied with thoughtful criteria and purpose, handwriting notes can be a highly effective learning tool [

34]. Rather than simply copying information, students who handwrite notes with the intention of organizing, summarizing and reframing content engage in deeper cognitive processing. This approach encourages active interaction with the material, leading to better retention and conceptual understanding. When learners take the time to decide what is important, how to structure their notes and how to express ideas in their own words, handwriting becomes a strategic method of learning rather than a mechanical task. Unlike passive transcription, this deliberate use of handwriting supports reflection, critical thinking and long-term comprehension. The value of handwriting lies not in the act itself, but in how it is employed to promote meaningful engagement with academic content.

The study by Khanova et al. (2015) [

13] highlights the critical importance of understanding students’ pre-existing attitudes and learning preferences when implementing a flipped classroom model. The pre-course survey revealed that a significant majority (72%) of students favoured traditional lecture-based instruction over flipped learning, and many did not consider reading to be an effective way of enhancing their learning. These findings suggest that students entered the course with limited familiarity with, and confidence in, independent, text-based study — an essential component of the flipped approach. Given that the out-of-class modules relied heavily on reading materials, it is unsurprising that students initially struggled to adapt to the format. McLean et al. (2016) [

32] reported that, in their implementation of the FC model, students developed independent learning strategies, dedicated more time to tasks and engaged in deeper, more active learning. According to Marshall et al. (2022) [

11], the survey results on student satisfaction revealed mixed reactions. 53% favoured the flipped classroom (FC) model, 22% preferred the traditional approach and 25% were neutral. Our own experience further supports these observations: prior to the course, students reported no prior exposure to flipped learning; however, by the end of the study, preferences had shifted, with half of the class identifying with the flipped model, while the other half maintained a preference for traditional instruction. This evolution underscores the importance of gradual adaptation and support when introducing innovative pedagogical strategies.

Students who preferred traditional lecture-based learning often perceived the flipped classroom design as less effective, which negatively impacted their learning experience and overall satisfaction [

13]. This perception was further reinforced in environments where instructors emphasized grade-oriented assessment strategies using conventional methods, promoting the 'happy students, good grades' philosophy. The flipped design required students to make a greater individual effort to access pre-class materials, contrasting with the more passive experience offered by traditional teaching, which is often shaped by a focus on student satisfaction, especially in institutional contexts such as UCM

Docentia programme, where teaching quality is primarily evaluated through student satisfaction scores [

7]. Tools for content creation and assessment are essential for successfully implementing the FC model [

4]. In this study, H5P® and Wooclap® were effectively utilized alongside cognitive-level questions to enhance student engagement and learning outcomes. However, implementing the FC model also requires significant administrative coordination and robust change management strategies, particularly within a traditional curriculum such as the one examined in this study. Firsthand experience of introducing these methodologies to students has revealed the challenges posed by a lack of support from colleagues who are resistant to change and prefer to maintain the conventional teaching system. This lack of institutional and peer support poses significant barriers to innovation and pedagogical transformation.