Submitted:

01 September 2025

Posted:

01 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

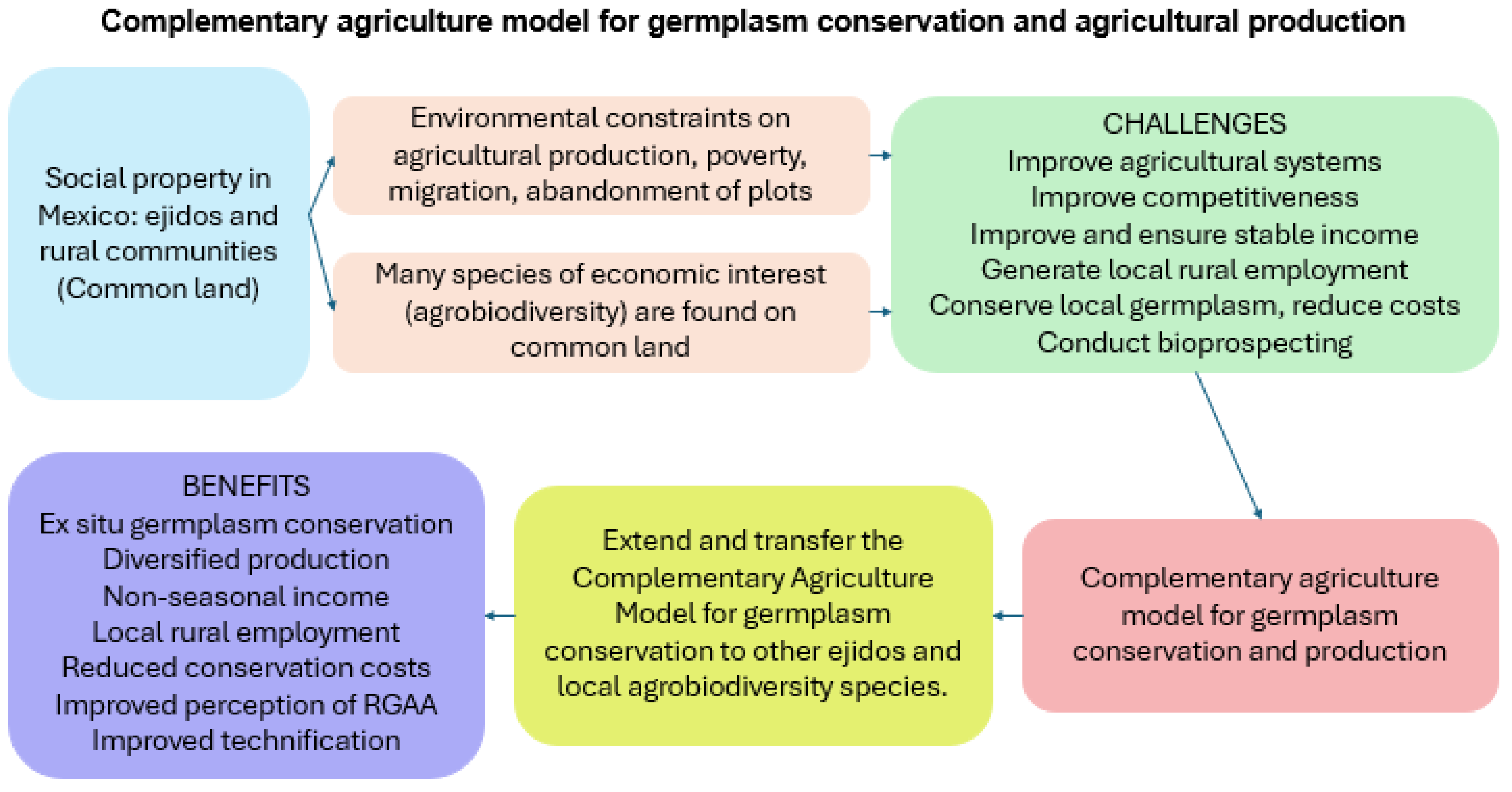

The rural population in areas of the Mexican semi-desert experiences poverty levels that limit a life free from socioeconomic deprivation, and they migrate, abandoning their assets. This is exacerbated by climate change (drought, temperatures), which affects crops. Although farmers try to cope with this, their strategies are insufficient. A low-cost Complementary Agriculture (AgriCom) model was designed using local resources to produce prickly pear cactus (Opuntia ficus-indica Mill.) known as “nopal” and corn (Zea mays L.), and to conserve regional germplasm of Opuntia spp. Yield, profitability, and Equivalent Land Use (ELU) were evaluated on seven varieties of prickly pear cactus. The Verdura, Atlixco, and Rojo Liso varieties showed higher cladode yield (vegetable), internal rate of return, and net present value; and their cost-benefit ratios were 7.97, 6.35, and 6.82, respectively. The ELU was greater than 1.0 when combining cactus varieties. The agroclimatic conditions did not allow corn to reach its phenological cycle and its ELU was zero. A total of 70 nopal genotypes were collected, with three replicates (N=210 conserved plants) integrated into the production module of eight Opuntia species. This model has been accepted in the Bank of Low-Cost Technological Solutions and/or Based on Local Resources, in the Platform for Climate Action in Agriculture in Latin America and the Caribbean (PLACA), to be installed in other communities in Latin America.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Geographical Area of Intervention

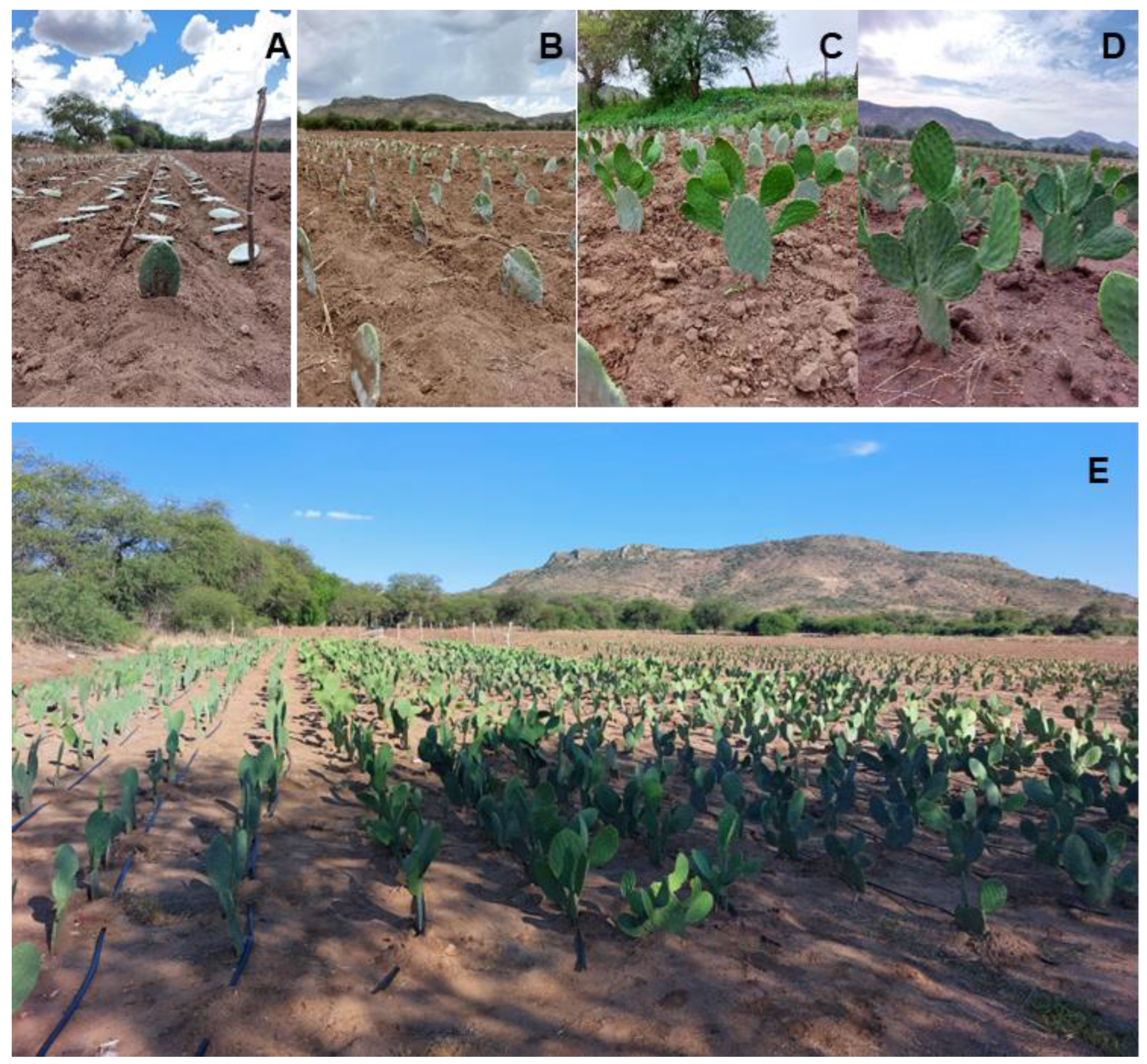

2.2. Research Phases

2.3. Plant Yield Variables

2.4. Equivalent Land Use (ELU)

2.5. Conservation Strategies

2.6. Collection, Uses and Geographical Origins

2.7. Production Yields and Costs

2.8. Minimum Infrastructure

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

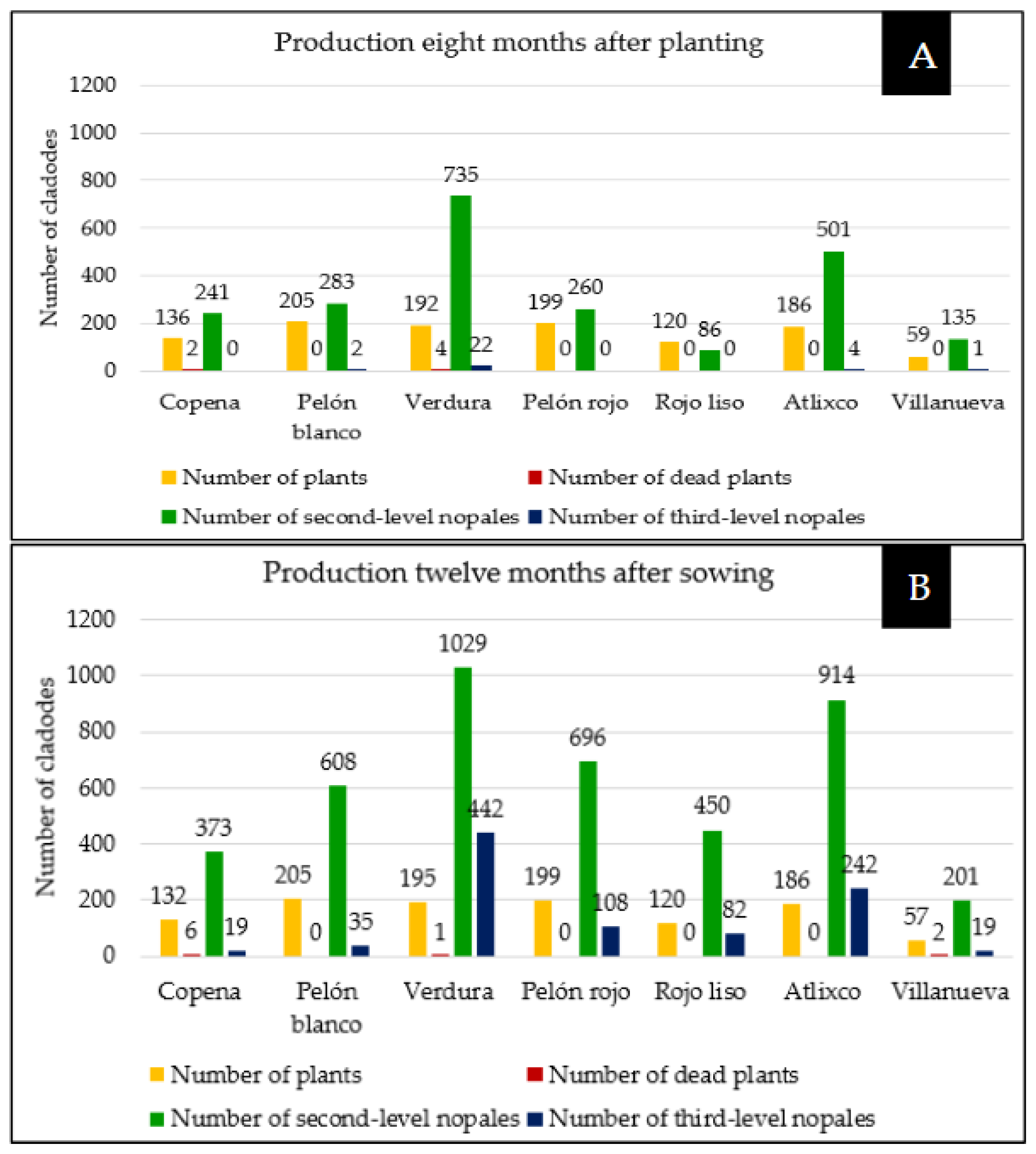

3.1. First Phase: Survival After Sowing and Emission of the Second and Third Levels of Cladodes

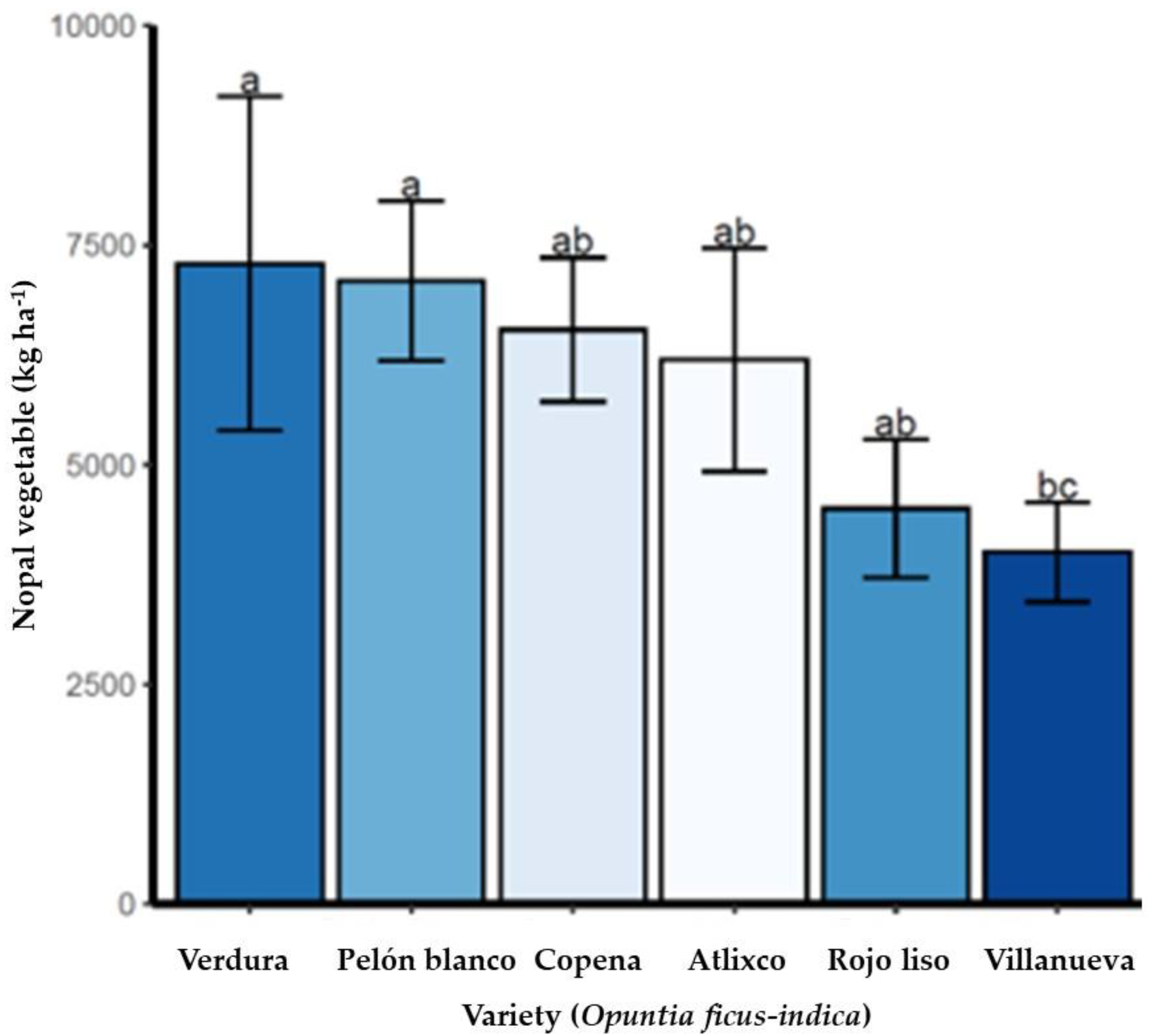

3.2. Yields and ELU

3.3. General Costs and Profitability Indices

3.4. Structuring of the Rainwater Harvesting System, Emergency Irrigation System

3.5. Conservation of Genotypes Collected

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGRICOM | Complementary Agriculture |

| ELU | Equivalent Land Use |

| RTR | Relative Total Yield |

| GRFA | Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture |

| NPV | Net Present Value |

| IRR | Internal Rate of Return |

References

- García-Sandoval, J. R. , Aldape-Ballesteros, L. A., & Esquivel, F.A. Perspectivas del desarrollo social y rural en México. Revista de Ciencias Sociales (Ve) 2020, 26, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez Juárez, J. Seguridad alimentaria y la agricultura familiar en México. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas 2022, 13, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino Pérez, L. (2019). Crisis Ambiental en México: Ruta para el cambio. 1–282.

- CDB. (1992). Convenio sobre la diversidad biológica. Programa de Las Nacionaes Unidas Para El Medio Ambiente.

- Sánchez-Galán, E.A. Pobreza rural y agricultura familiar: Reflexiones en el contexto de América Latina. Revista Especializada en Ciencias Agropecuarias 2021, 1, 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J. S. , Gutiérrez, A. G., & Chávez, C.C. (2019). Medición Multidimensional de la Pobreza Rural en México: acceso efectivo y nuevas dimensiones. (265.a ed., Vol. 39). Instituto de Estudios Peruanos. https://repositorio.iep.org.pe/server/api/core/bitstreams/a876d7f6-4246-4edc-ad1d-bf4e16cf260f/content.

- Lorenzen, M. Nueva ruralidad y migración en la Mixteca Alta, México. Perfiles Latinoamericanos 2021, 29, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yúnez Naude, A. , & González Andrade, S. Efectos multiplicadores de las actividades productivas en el ingreso y pobreza rural en México. El trimestre económico 2008, 75, 349–377. [Google Scholar]

- Pedro-Valencia, G. , López-García, A., Rodiles-Hernández, S., & Camacho-Vera, J. Incidencia de las políticas públicas en la reconfiguración del sector agrario en México. SUMMA. Revista Disciplinaria En Ciencias Económicas y Sociales 2022, 4, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. (2019). The State of the World’s Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture. In FAO Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture Assesments. [CrossRef]

- Hernández Sánchez, M. I. , & Travieso Bello, A. C. Medidas de adaptación al cambio climático en Organizaciones cafetaleras de la zona centro de Veracruz, México. Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems 2021, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, C. I. , & Altieri, M.A. Bases agroecológicas para la adaptación de la agricultura al cambio climático. UNED Research Journal 2019, 11, 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Tamayo Ortiz, C. V. , & Alegre Orihuela, J. C. Asociación de cultivos, alternativa para el desarrollo de una agricultura sustentable. Siembra 2022, 9, 23–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gliessman, S.R. (2002). Agroecología: Procesos ecológicos en agricultura sostenible. In Diversidad y estabilidad del agroecosistema.

- Gutiérrez Alzate, F. (2020). Práctica tradicional de agricultura: Los policultivos como estrategia de sustento económico y conservación de los recursos naturales in situ en el corregimiento de Santa Cecilia - Pueblo Rico. Universidad Católica de Pereira. https://repositorio.ucp.edu.co/entities/publication/92d4bff8-54ca-4f31-9ea7-c8bce4662381.

- Gallardo-Milanés, O. A. Agricultura Familiar Y La Adaptación Al Cambio Climático En Coaprocor- Paraná, Brasil. Agroecologia: Métodos e Técnicas Para Uma Agricultura Sustentável 2021, 1, 379–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, A. P. Reflexión sobre la pobreza rural en la región planicie huasteca del Estado de San Luis Potosí, México. CIBA Revista Iberoamericana de las Ciencias Biológicas y Agropecuarias 2016, 5, 68–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Sánchez, F. , Cadena-Iñiguez, J., Gómez-González, A., Ruiz-Vera, V. M., Morales Flores, F. J., & Bustamante-Lara, T.I. Modelo de producción y conservación de germoplasma (AgriCom) en una comunidad rural del semidesierto mexicano. Agro-Divulgación 2022, 2, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Sánchez, F. , Cadena-Iñiguez, J., Gómez-González, A., Ruiz-Vera, V. M., & Morales-Flores, F.J. Soluciones tecnológicas de bajo costo con recursos locales en un modelo de agricultura complementaria. AEIPRO 2023, 2019–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Zongua, D. M. , & Lizárraga-Mendiola, L. Cosecha de lluvia para reducir la escasez hídrica en una zona rural de Puebla. Pädi Boletín Científico de Ciencias Básicas e Ingenierías Del ICBI, 2022; 10, 161–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceves-Navarro, E. , Reyes-Montero, J. A., & Vera-Espinoza, J. Abastecimiento con agua de lluvia a comunidades rurales del Estado de Campeche, México. Agro-Divulgación 2021, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Osorio, A. , Ortiz Przychodzka, S., & Ortiz Pinilla, J.E. Aportes De La Agrobiodiversidad a La Sustentabilidad De La Agricultura Familiar En Colombia. Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems 2020, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerer, K. S. , de Haan, S., Jones, A. D., Creed-Kanashiro, H., Tello, M., Carrasco, M., Meza, K., Plasencia Amaya, F., Cruz-Garcia, G. S., Tubbeh, R., & Jiménez Olivencia, Y. The biodiversity of food and agriculture (Agrobiodiversity) in the anthropocene: Research advances and conceptual framework. Anthropocene 2019, 25, 100192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEGI. (2020). Panorama sociodemográfico de San Luis Potosí. In Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020. https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/productos/prod_serv/contenidos/espanol/bvinegi/productos/nueva_estruc/702825197858.pdf.

- Cadena-Iñiguez, J. , Ruiz-Posadas, L. del M., Trejo-Téllez, B. I., Morales-Flores, F. J., & Talavera-Magaña, D. Red doméstica de producción de nopal (Nopalea sp.) para exportación. Agro Productividad 2019, 12, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, R. , & Willey, R.W. The concept of a “land equivalent ratio” and advantages in yields from intercropping. Experimental Agriculture 1980, 16, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. (2012). Segundo Plan de Acción Mundial para los Recursos Fitogenéticos para la Alimentación y la Agricultura. In Informes De Organizaciones Internacionales Sobre Sus Políticas, Programas Y Actividades En Relación Con La Diversidad Biológica Agrícola.

- SADER. Programa de trabajo multianual del comité sectorial de recursos genéticos para la alimentación y la agricultura 2022–2024. Diversidad Genética Para La Producción Sostenible. La Adaptación Al Cambio Climático y El Bienestar, 2022; 1–135.

- FAO. (2007). Bosques y biodiversidad agrícola para la seguridad alimentaria en América Central. In Biodiversidad agrícola.

- DOF. Acuerdo por el que se crea el Comité Sectorial de Recursos Genéticos para la Alimentación y la Agricultura. Diario Oficial de La Federación.

- Hernández Bonilla, B. E. , Ruiz Reynoso, A. M., Ramírez Cortés, V., Sandoval Trujillo, S. J., & Dávila Hernández, M. (2020). Análisis económico de productores y comercializadores de nopal en el Valle de Teotihuacán. In RICEA Revista Iberoamericana de Contaduría, Economía y Administración (Vol. 9, Issue 17). [CrossRef]

- Domínguez García, M. V. , Flores Merino, M. V., Flores Estrada, J., Montenegro Morales, L. P., Morales Ávila, E., & Santillán Benítez, J.G. (2023). Principios activos de las plantas usadas en la medicina tradicional mexicana.

- SNICS. 2018. El Sistema de Información de Bancos de Germoplasma Mexicano (BanGERMEX) https://www.gob.mx/snics/articulos/que-es-el-bangermex?idiom=es. 2024.

- SNICS. 2020. Programa Nacional de Semillas 2020-2024 https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle_popup.php?codigo=5608920 Consultado 03 abril 2024.

- Román-Montes de Oca, E. , Licea-Resendiz, J. E., & Romero-Torres, F. Diversificación de ingresos de los productores como estrategias de desarrollo rural. Entramado 2020, 16, 126–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadena-Iñiguez, J. , Ruiz-Posadas, L. del M. , Trejo-Téllez, B. I., Morales-Flores, F. J., & Talavera-Magaña, D. Red doméstica de producción de nopal (Nopalea sp.) para exportación. Agro Productividad 2019, 12, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lluch-Cota, S. E. , Velázquez Zapata, J. A., & Nieto Delgado, C. Agricultura, agua y cambio climático en zonas áridas de México. Recursos Naturales Y Sociedad 2022, 8, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COP25. (2019). Conferencia de las Naciones Unidas sobre el Cambio Climático de 2019. https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conferencia_de_las_Naciones_Unidas_sobre_el_Cambio_Clim%C3%A1tico_de_2019. Accesado 10 jun 2025.

- PLACA (2025). Plataforma de Acción Climática en Agricultura de Latinoamérica y el Caribe https://accionclimaticaplaca.org/es/sobre-placa/. Accesado 22 jun 2025.

- Casas, A. , Caballero, J., Mapes, C., & Zárate, S. Manejo de la vegetación, domesticación de plantas y origen de la agricultura en Mesoamérica. Botanical Sciences 2017, 61, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Moreno, D.E. (2023). Análisis de la agricultura regenerativa como práctica sostenible para la gestión y uso del suelo en Colombia. Agricultura Regenerativa Como Práctica Sostenible.

- Vázquez, J. , Alvarez-Vera, M., Iglesias-Abad, S., & Castillo, J. La incorporación de enmiendas orgánicas en forma de compost y vermicompost reduce los efectos negativos del monocultivo en suelos. Scientia Agropecuaria 2020, 11, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carranza-Cárdenas, C.C. (2021). Eficiencia agronómica de la asociación de cultivo maíz (Zea mays) vs leguminosas fréjol cuarentón, (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) - maní (Arachis hypogaea) y su efecto en el rendimiento. 36–38. https://repositorio.uteq.edu.ec/handle/43000/6509.

- Arteaga-Rodríguez, O. , Espinosa Aguilera, W., Bernal-Carraza, Y., & Hernández-Rodríguez, C. Implantación de algunas prácticas del manejo sostenible de tierras en una finca agropecuaria en Cienfuegos, Cuba. Revista Científica Agroecosistemas 2020, 8, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Betancur, L. M. , Márquez-Girón, S. M., & Restrepo-Betancur, L. F. La milpa como alternativa de conversión agroecológica de sistemas agrícolas convencionales de frijol (Phaseolus vulgaris), en el municipio El Carmen de Viboral, Colombia. Idesia 2018, 36, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez González, A. Y. , Chávez Mejía, C., Herrera Tapia, F., & Carreño Meléndez, F. Milpa y seguridad alimentaria: El caso de San Pedro El Alto, México. Revista de Ciencias Sociales 2018, 24, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa Lozano, J.B. (2018). Farmer crop variety mixtures to cope with disease epidemics in the common bean cropping system of the Ecuadorian highlands. 1–23. https://hdl.handle.net/11573/1077355.

- Magra, G. C. , Saperdi, A. J., & Ferreras, L.A. Diagnosticar las reservas de agua útil: Una herramienta para la toma de decisiones y potenciar la rentabilidad económica del cultivo de trigo. Revista Americana de Empreendedorismo e Inovação /American Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation 2021, 3, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge, A. O. S. , Costa, A. S. G., & Oliveira, M. B. P. P. Adapting to climate change with Opuntia. Plants 2023, 12, 2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licerán-Fuentes, D. Tolerancia de Opuntia spp. a diferentes tipos de estreses abióticos relacionados con el cambio climático. Facultad de Ciencias Experimentales 2021, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- González Alfredo, N. , Rivera Martínez, J. G., Vela Correa, G., Silva Torres, B., Puebla Torres, H., Sánchez Martínez, M., & Reséndiz de la Rosa, G. (2015). Evaluación del contenido de carbono orgánico en suelos del cultivo intensivo de nopal (Opuntia ficus-indica L.) en la delegación de Milpa Alta, México D.F. [PDF]. Recuperado de https://sedici.unlp.edu.ar/bitstream/handle/10915/52510/Documento_completo.pdf-PDFA.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Cordova-Quispe, D.M. Uso Equivalente de la Tierra y características biométricas del cultivo asociado de lechuga (Lactuca sativa L.) y cebolla (Allium cepa L.) bajo riego por goteo. Repositorio Institucional - UNH 2021, 80. http://repositorio.unh.edu.pe/handle/UNH/2755.

- Mola Fines, B. , Bonet Pérez, C., Rodríguez Correa, D., Guerrero Posada, P., Avilés Martínez, G., & Martínez Der, C. Tecnologías para el uso eficiente de los recursos hídricos en fincas ganaderas. Revista Ingeniería Agrícola 2021, 11, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gordillo-Bartolo, F. I. Diseño del tamaño óptimo del tanque para sistema de captación de agua de lluvia en la Universidad de Santader, Bucaramanga, Colombia. Facultad de Ingeniería. Universidad Autónoma Del Estado de México, 2022; 1–80. [Google Scholar]

| Species | Variety | Use | Density (plants ha-1) |

| Opuntia ficus-indica Mill. | Copena | Vegetable | 20,952 |

| Opuntia ficus-indica Mill. | Pelón blanco | Forage | 20,952 |

| Opuntia ficus-indica Mill. | Verdura | Vegetable | 20,952 |

| Opuntia ficus-indica Mill. | Pelón rojo | Forage | 20,952 |

| Opuntia ficus-indica Mill. | Rojo liso | Vegetable | 20,952 |

| Opuntia ficus-indica Mill. | Atlixco | Vegetable | 20,952 |

| Opuntia ficus-indica Mill. | Villanueva | Vegetable | 20,952 |

| Zea mays L. | Criollo local | Grain | 20,000 |

| Variety (Opuntia ficus-indica |

Second level emission (t ha-1) |

Third level emission (t ha-1) |

Emission ratio between second and third level (%) |

| Verdura | 10.83 | 4.653 | 42.96 |

| Atlixco | 10.38 | 2.750 | 26.49 |

| Rojo liso | 8.33 | 1.519 | 18.24 |

| Pelón rojo | 7.40 | 1.149 | 15.53 |

| Villanueva | 6.70 | 0.633 | 9.45 |

| Pelón Blanco | 6.40 | 0.368 | 5.75 |

| Copena | 5.921 | 0.302 | 5.10 |

| Variety | Yield (kg ha-1) | Income $ ha-1 ($10.00 kg) |

Yield (kg ha-1) |

Income $ ha-1 ($10.00 kg) |

Yield (kg ha-1) |

Income $ ha-1 ($10.00 kg) |

ELU (nopal variety versus corn) |

| R1 | R2 | R3 | |||||

| Verdura | 5276.92 | 52,769.23 | 7543.59 | 75,435.90 | 9052.31 | 90,523.08 | >1.0 |

| Atlixco | 6400.00 | 64,000.00 | 6768.42 | 67,684.21 | 8122.11 | 81,221.05 | >1.0 |

| Rojo liso | 5920.63 | 59,206.35 | 6222.22 | 62,222.22 | 7466.67 | 74,666.67 | >1.0 |

| Pelón rojo | 4913.98 | 49,139.78 | 6215.05 | 62,150.54 | 7458.06 | 74,580.65 | >1.0 |

| Villanueva | 3750.00 | 37,500.00 | 4433.33 | 44,333.33 | 5320.00 | 53,200.00 | >1.0 |

| Pelón Blanco | 3497.49 | 34,974.87 | 4040.20 | 40,402.01 | 4848.24 | 48,482.41 | >1.0 |

| Copena | 3526.32 | 35,263.16 | 3859.65 | 38,596.49 | 4631.58 | 46,315.79 | >1.0 |

| Corn | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.0 |

| Variety (Opuntia ficus-indica) | Net Present Value (NPV) | Internal Rate of Return (IRR %) | Benefit /Cost Ratio (B/CR) |

| Verdura | 231,077.73 | 67 | 7.97 |

| Atlixco | 143,831.02 | 70 | 6.35 |

| Rojo liso | 139,288.51 | 51 | 6.82 |

| Pelón rojo | 99,715.71 | 48 | 6.28 |

| Villanueva | 88,646.13 | 42 | 5.67 |

| Pelón Blanco | 51,580.62 | 26 | 5.40 |

| Copena | 38,630.41 | 21 | 4.93 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).