1. Introduction

Rice serves as the primary staple food across Asian countries, particularly in Southeast Asia, where Thailand ranks among the top ten rice-consuming nations globally [

1]. As one of the world’s leading rice exporters [

1], Thailand has a rich culinary tradition deeply rooted in rice consumption, where rice functions not only as a main dish but also as a versatile ingredient in traditional desserts and processed foods. This diversification of rice applications supports sustainable agricultural practices while generating additional income for farmers through value-added products. Thai rice varieties are traditionally classified into four main categories: Thai Hom Mali rice (Jasmine rice), glutinous rice, white rice, and unpolished rice. Among these, Lueang Patew Chumphon (LPC) rice (Khao Lueang Patew Chumphon) represents a distinctive traditional white rice variety indigenous to Pathew District, Chumphon Province, in southern Thailand. This variety demonstrates remarkable adaptability to challenging growing conditions, thriving in lowland areas with acidic and brackish saline soils near coastal regions. LPC rice exhibits natural resistance to diseases and insects while maintaining good yield potential [

2]. The variety received official recognition as a geographical indication (GI) from the Department of Intellectual Property Thailand on December 30, 2008 [

3], acknowledging its unique characteristics and regional significance. LPC rice is characterized by exceptionally high amylose content (>25%), which significantly influences its physicochemical properties, nutritional composition, and processing characteristics [

4]. This high-amylose structure confers several advantages, including enhanced resistant starch formation, superior mineral bioavailability, and improved protein digestibility compared to conventional rice varieties [

5]. Upon cooking and cooling, the high-amylose content undergoes retrogradation, resulting in a firmer, fluffier texture compared to low-amylose varieties such as Jasmine rice (Khao Dawk Mali 105) [

6,

7,

8,

9]. More importantly, the high-amylose structure confers resistance to enzymatic digestion, resulting in slower glucose release and a lower glycemic index compared to conventional rice varieties [

10]. Recent studies have demonstrated that high-amylose rice varieties exhibit enhanced antioxidant capacity and bioactive compound retention, making them promising candidates for functional food development [

11].

Traditional Thai sweet fermented rice (Khao Mak) represents a complex fermented food system involving multiple microorganisms such as yeasts, lactic acid bacteria, and fungi, which contributes to distinctive flavor profiles, nutritional enhancement, and preservation characteristics [

12]. The fermentation process significantly alters the volatile compound composition, creating unique organoleptic properties that determine consumer acceptance and product quality [

13]. Contemporary food science emphasizes the importance of comprehensive quality assessment approaches that integrate chemical, microbiological, nutritional, and sensory analyses to fully characterize fermented food products [

14].

Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) has emerged as the standard for volatile compound profiling in fermented foods, enabling precise identification and quantification of aroma-active compounds that define product quality and consumer appeal. The volatile compound profile of fermented rice products directly correlates with sensory attributes and can serve as objective quality indicators for product standardization and optimization [

15].

Despite the well-documented health advantages of high-amylose rice varieties, LPC rice remains underutilized due to consumer preference for softer-textured, low-amylose varieties when consumed as cooked rice. However, the growing awareness of health benefits associated with low-glycemic-index foods and functional foods presents an opportunity to promote LPC rice through innovative product development. Limited research exists on the comprehensive quality assessment of high-amylose rice varieties in fermented applications, particularly regarding their impact on volatile compound formation, nutritional enhancement, mineral bioavailability, and overall organoleptic characteristics compared to conventional fermented rice products [

5].

2. Results

2.1. Microbial Community and Fermentation Dynamics

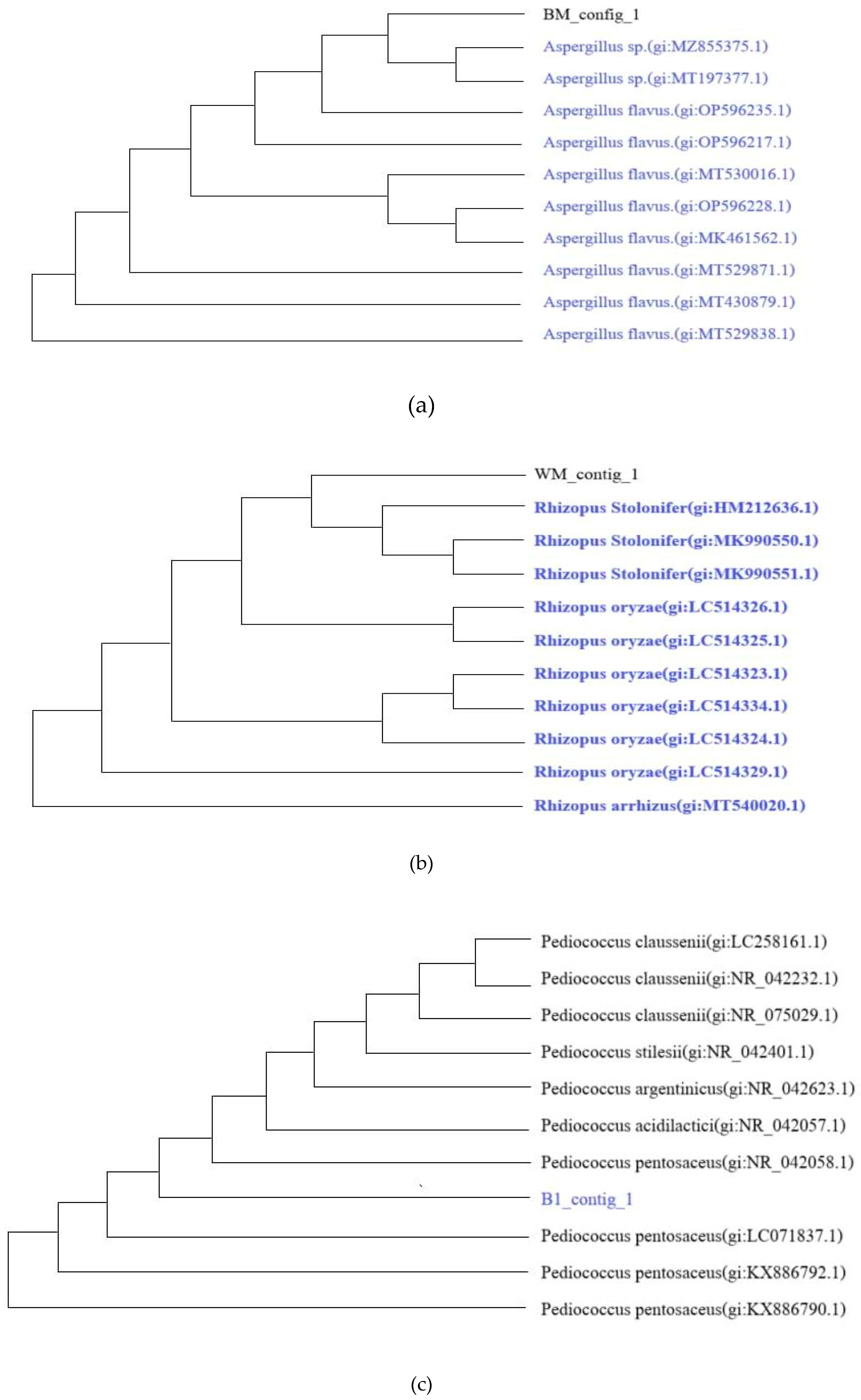

DNA sequencing and BLAST analysis identified three key microbial species from traditional starter cakes:

Aspergillus sp. (100% similarity),

Rhizopus stolonifer (99.84% similarity),and

Pediococcus pentosaceus (99.80% similarity) (

Figure 1). These microorganisms established thefoundation for subsequent fermentation processes.

At fermentation initiation (day 0), both fungal species (Aspergillus sp. and R. stolonifer) were present alongside P. pentosaceus, facilitating initial starch hydrolysis through amylase enzyme production. By day 1, fungal populations were no longer detectable, while Candida tropicalis emerged as the dominant yeast species alongside P. pentosaceus. This microbial succession pattern reflected the changing environmental conditions during fermentation, particularly decreasing pH and oxygen availability.

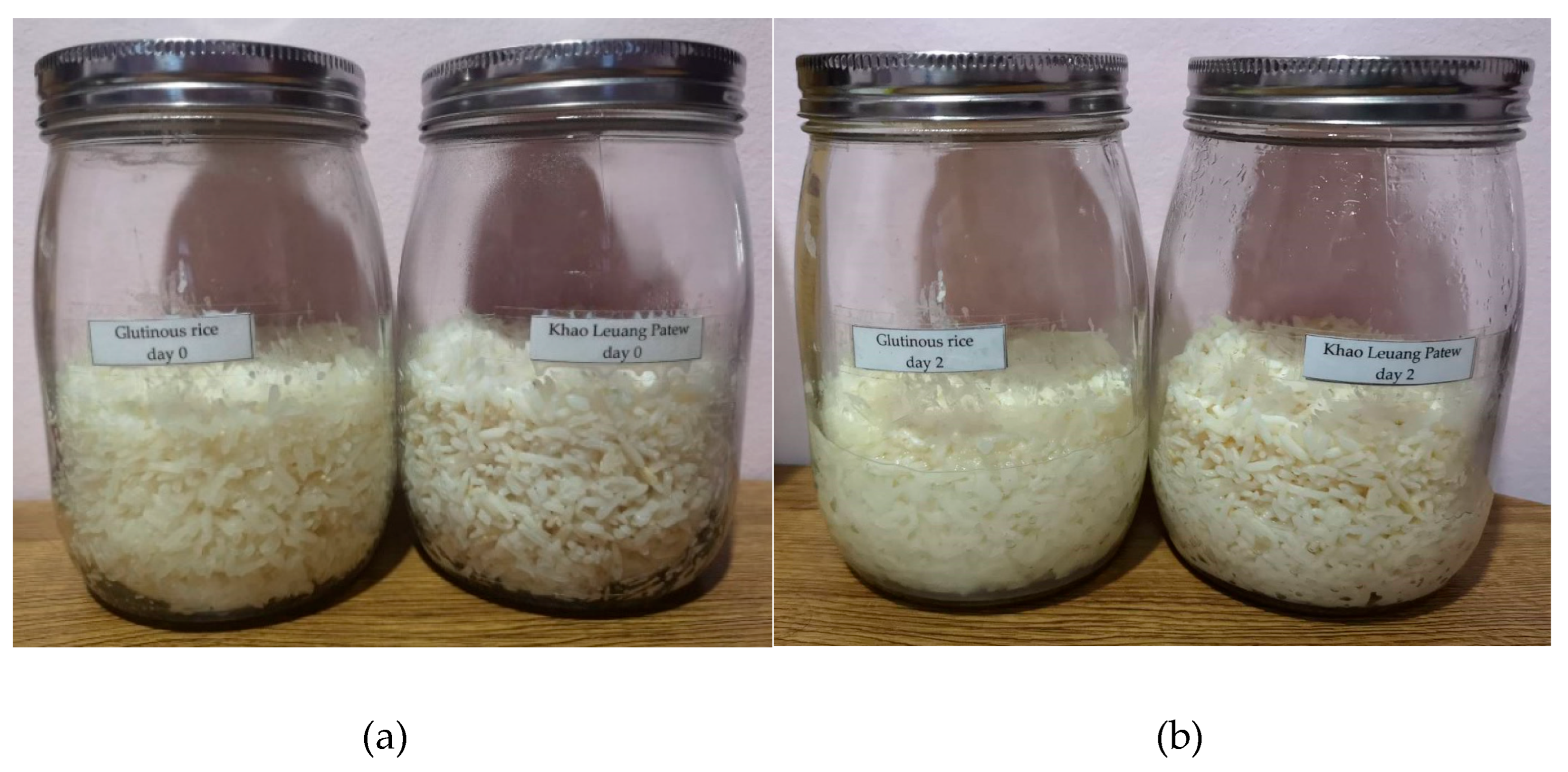

Figure 2.

Thai sweet fermented rice at day 0 (a) and day 2 (b). The jars on the left in both photos show glutinous rice as the base ingredient, while the jars on the right show LPC rice as the base ingredient.

Figure 2.

Thai sweet fermented rice at day 0 (a) and day 2 (b). The jars on the left in both photos show glutinous rice as the base ingredient, while the jars on the right show LPC rice as the base ingredient.

Both rice varieties demonstrated comparable fermentation patterns over 48 hours (

Table 1). pH reduction showed large effect sizes in both varieties: SFLPC decreased 43% (from 6.15±0.02 to 3.50±0.01) while SFGR decreased 39% (from 5.78±0.11 to 3.55±0.00). The initial pH difference between varieties (0.37 units) represented a moderate effect size, likely reflecting inherent compositional differences.

Total soluble solids (TSS) increases demonstrated large effect sizes, with SFGR showing a 56% higher final concentration (33.47±0.12°Brix) compared to SFLPC (21.47±0.06°Brix), representing a difference of 12.0°Brix with large practical significance. SFGR exhibited a 4.3-fold increase while SFLPC showed a 6.4-fold increase from baseline values.

Ethanol production showed small effect sizes between varieties, with concentrations differing by only 3% (3.60±0.11% v/v in SFLPC vs. 3.72±0.12% v/v in SFGR). Lactic acid concentrations increased 2.4-fold in both varieties, reaching over 6,000 mg/L with negligible between-variety differences (0.2% difference, representing minimal practical significance). The concurrent production established dual preservation mechanisms through low pH and elevated organic acid concentrations.

2.2. Chemical Composition and Nutritional Characteristics

HS-SPME-GCMS analysis identified nine volatile compounds with match factors between 95.4-98.2% (

Table 2). Odor descriptors in

Table 2 are based on individual compound characteristics from literature and serve as preliminary indicators only. These attributes do not represent the actual sensory profile of the fermented rice products, which would require comprehensive organoleptic evaluation with trained sensory panels.

Higher alcohols dominated both samples, with isoamyl alcohol showing a moderate effect size difference between varieties (7.6 percentage point difference: 30.45% in SFLPC vs. 22.85% in SFGR). Isobutyl alcohol concentrations showed negligible effect sizes between samples (0.33 percentage point difference). Large effect sizes were observed in fatty acid ester profiles between varieties. Hexadecanoic acid ethyl ester demonstrated the largest effect size among shared compounds, with SFGR containing 2.8-fold higher concentrations than SFLPC (4.61 percentage point difference). Several compounds showed variety-specific presence patterns with large effect sizes: two fatty acid esters were exclusively detected in SFGR (dodecanoic acid ethyl ester at 4.52% and tetradecanoic acid ethyl ester at 3.14%), while two unsaturated esters were unique to SFLPC (9-octadecenoic acid methyl ester at 1.58% and ethyl oleate at 0.91%).

Mineral analysis revealed large effect sizes between varieties for key macrominerals (

Table 3). SFLPC demonstrated large effect sizes for phosphorus (2.1-fold higher: 1,445±143 vs. 687±54 mg/kg), potassium (1.9-fold higher: 1,138±0.3 vs. 612±38 mg/kg), and magnesium (1.9-fold higher: 217±15 vs. 115±6 mg/kg) compared to SFGR. Calcium showed moderate effect sizes with 53% higher levels in SFLPC (192±2 vs. 125±5 mg/kg). Among trace elements, zinc concentrations showed small effect sizes between varieties (9% difference: 19.7±1.8 vs. 18.1±0.8 mg/kg), while iron and copper demonstrated negligible effect sizes between varieties.

Fermentation produced moderate to large effect sizes in mineral composition compared to unfermented counterparts. Phosphorus showed moderate effect sizes with 37% increase in SFLPC and 23% increase in SFGR. Zinc demonstrated small to moderate effect sizes with 29% increase in SFLPC and 18% increase in SFGR. Sulfur content showed large effect sizes with substantial decreases of 70% in SFLPC and 66% in SFGR following fermentation.

Nutritional analysis revealed moderate effect sizes between varieties (

Table 4). SFGR showed moderate effect sizes for carbohydrate content (4.6% higher than SFLPC: 85.14±0.20% vs. 81.42±0.12%), while SFLPC demonstrated moderate effect sizes for protein content (16% higher: 10.53±0.07% vs. 9.07±0.03%) and fat content (41% higher: 1.58±0.06% vs. 1.12±0.05%). Energy values showed small effect sizes with limited practical significance (1.3% difference: 386.9±1.2 vs. 382.1±0.7 kcal/100g).

Fermentation produced large effect sizes in protein content compared to unfermented counterparts: 41% increase in SFGR and moderate effect sizes with 21% increase in SFLPC. The fermentation process showed large effect sizes in reducing crude dietary fiber content in both varieties, with substantial decreases likely due to enzymatic degradation during fermentation.

2.3. Quality Assessment and Bioactivity

Color measurement using the L

ab* system [

16] showed minimal differences between products (

Table 5). Both fermented products met Thai Community Product Standards [

17] fortraditional sweet fermented rice, with acceptable visual characteristics for consumer acceptance.

Both fermented products demonstrated acceptable microbiological quality with no detectable Escherichia coli and yeast/mold counts below 100 CFU/g. The combination of pH reduction (≤3.55) and organic acid production (>6,000 mg/L lactic acid) provided effective preservation against pathogenic microorganisms.

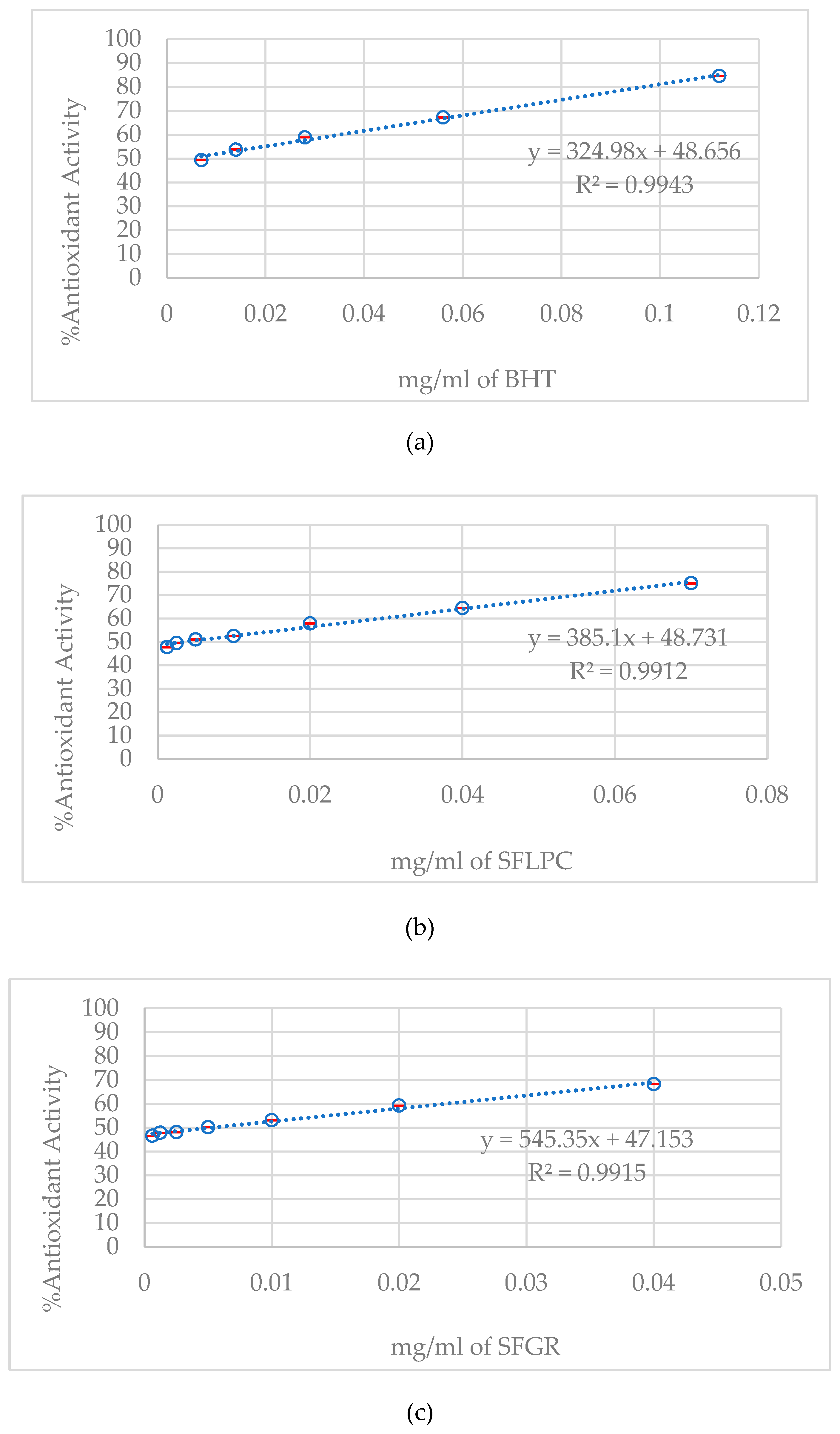

DPPH radical scavenging assay revealed measurable antioxidant capacity in both varieties (

Figure 3). SFLPC demonstrated lower IC₅₀ values (3.3 µg/mL) compared to SFGR (5.2 µg/mL), indicating enhanced radical scavenging ability. Both fermented products showed antioxidant activity comparable to synthetic antioxidant BHT (IC₅₀: 4.1 µg/mL), suggesting potential as natural antioxidant sources.

3. Discussion

3.1. Microbial Community Dynamics and Fermentation Processes

The microbial succession observed during sweet fermented rice production demonstratedcomplex interactions characteristic of traditional Asian fermented foods [

18]. The initial presence of

Aspergillus sp. and

Rhizopus stolonifer, followed by their disappearance and emergence of

Candida tropicalis alongside sustained

Pediococcus pentosaceus populations, reflected sequential metabolic activities essential for fermentation optimization. This succession pattern aligns with established fermentation theory where fungi initiate starch hydrolysis, followed by yeast and lactic acid bacteria activities [

19].

The enzymatic contributions of each microbial group facilitated distinct biochemical transformations.

Aspergillus sp. and

R. stolonifer produced α-amylase, glucoamylase, and proteases during initial phases, converting complex carbohydrates into fermentable substrates.

C. tropicalis subsequently metabolized these sugars into ethanol and contributed to ester synthesis through alcohol acetyltransferase activity.

P. pentosaceus maintained consistent lactic acid production throughout the process, establishing the preservation system through pH reduction [

19,

20].

The large effect size pH reductions observed (43% in SFLPC and 39% in SFGR) created environmental conditions that sequentially favored different microbial groups. The convergent final pH values (≤3.55) despite moderate effect size initial differences (0.37 units) demonstrated the robust control mechanisms inherent in this traditional fermentation system. This pH range effectively inhibited pathogenic microorganisms while maintaining beneficial fermentation microflora [

19].

3.2. Carbohydrate Metabolism and Metabolic Constraints

The large effect size TSS increases (6.4-fold for SFLPC and 4.3-fold for SFGR) reflected extensive enzymatic starch hydrolysis during fermentation [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. However, the substantial TSS difference between varieties (56% higher in SFGR with large effect size) did not translate to proportional ethanol production differences, which showed only small effect sizes (3% difference between varieties). This apparent paradox highlighted multiple metabolic constraints operating within the fermentation system [

24,

25,

26,

27].

The primary limitation appeared to be ethanol tolerance of

C. tropicalis under specific fermentation conditions. Most yeast strains exhibit decreased fermentation efficiency as ethanolconcentrations approach 3-4% v/v, particularly in high-acid environments. The toxic effects ofethanol on yeast cell membranes create natural ceilings for alcohol production, independentof substrate availability [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Additionally, the large effect size TSS concentration in SFGR(33.47°Brix) may have induced osmotic stress, paradoxically inhibiting yeast metabolism [

25]. High sugar levels can reduce cell viability and fermentation rates through osmotic pressure effects [

21,

25]. The dual fermentation system involving both

C. tropicalis and

P. pentosaceus also created substrate competition, where lactic acid bacteria simultaneously utilized glucose fororganic acid production, limiting sugar availability for alcoholic fermentation [

28,

29].

3.3. Chemical Composition and Variety-Specific Characteristics

The distinct volatile compound profiles between varieties demonstrated rice variety influence on fermentation-derived compounds [

30,

31,

32]. SFLPC showed moderate effect size differences in isoamyl alcohol content (7.6 percentage points higher), suggesting enhanced amino acid metabolism during fermentation. The large effect size differences in fatty acid ester profiles revealed variety-specific lipid metabolism patterns, with SFGR exclusively producing medium-chain ethyl esters and SFLPC uniquely containing unsaturated fatty acid esters. This study focuses on chemical characterization without sensory validation. Future research should include trained sensory panel evaluation to correlate analytical findings with actual organoleptic properties.

Mineral composition analysis revealed large effect sizes for key macrominerals, with SFLPC demonstrating 2.1-fold higher phosphorus, 1.9-fold higher potassium, and 1.9-fold higher magnesium concentrations compared to SFGR. These differences likely reflect both inherent rice variety characteristics and fermentation-induced modifications. The moderate to large effect sizes observed in mineral enhancement following fermentation (37% phosphorus increase in SFLPC, 29% zinc increase) suggest improved bioavailability through microbial enzyme activity, potentially breaking down phytic acid and other mineral-binding compounds [

33,

34,

35].

Proximate composition revealed moderate effect sizes between varieties, with SFGR showing 4.6% higher carbohydrate content while SFLPC demonstrated 16% higher protein and 41% higher fat content. The large effect sizes in protein enhancement following fermentation (41% increase in SFGR, 21% increase in SFLPC) indicated significant nutritional improvements compared to unfermented counterparts.

3.4. Quality Assessment and Bioactive Properties

The moderate effect size differences in antioxidant capacity (36% better scavenging in SFLPC) demonstrated variety-specific bioactive compound development during fermentation. The IC₅₀ values (3.3 µg/mL for SFLPC vs. 5.2 µg/mL for SFGR) represented practically meaningful differences in radical scavenging ability, with SFLPC outperforming synthetic antioxidant BHT by 20%.

Color characteristics showed small to moderate effect sizes between varieties, with measurable differences in redness (29% difference) and yellowness (10% difference) that may influence consumer acceptance. Despite these differences, both products met established quality standards, demonstrating the robustness of the traditional fermentation process across different rice varieties.

The microbiological safety evaluation confirmed that the dual preservation system of pH reduction and organic acid production effectively controlled pathogenic microorganisms while maintaining product quality [

36,

37,

38]. The absence of detectable

E. coli and acceptable yeast/mold counts validated the safety profile of both fermented products.

3.5. Implications for Traditional Food Systems

The comprehensive characterization revealed that rice variety selection influences multiple aspects of fermented product quality through large to moderate effect sizes across chemical, nutritional, and sensory parameters. SFLPC demonstrated enhanced mineral retention, improved antioxidant capacity, and complex volatile profiles compared to traditional glutinous rice, suggesting potential applications in functional food development.

The fermentation process itself showed consistent large effect sizes in nutritional enhancement, including protein content increases and mineral bioavailability improvements. These findings validate traditional fermentation practices while providing scientific evidence for the nutritional benefits of fermented rice products.

The variety-specific metabolic pathways and compound development patterns indicate opportunities for targeted optimization in commercial applications. The maintenance of traditional fermentation benefits combined with variety-specific enhancements suggests sustainable approaches to functional food development while preserving cultural food heritage.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.1.1. Starter Cakes

Traditional fermentation starter cakes (Look Pang) used for Thai sweet fermented rice production were obtained from a local producer in Muang District, Chumphon Province, Thailand. These semicircular starch-based inoculants contain indigenous molds and yeasts specific to regional production methods. Rice flour-based starter cakes are traditionally supplemented with local herbs to maintain microbial quality and prevent contamination by exogenous microorganisms. The starter cakes measured 3.5 cm in diameter with an average weight of 12.02 g (

Figure 4), and were stored at 4°C until use.

4.1.2. Rice Varieties

Lueang Patew Chumphon (LPC) rice, a local variety, was procured from Bang Son Subdistrict Community Enterprise, Chumphon Province, Thailand. Commercial glutinous rice was purchased from a local supermarket and served as a comparative control.

4.1.3. Chemicals and Reagents

Potato dextrose agar (PDA) and nutrient agar were purchased from HIMEDIA (Mumbai, India). All other chemicals and reagents used were of analytical grade unless otherwise specified.

4.2. Methods

4.2.1. Microbial Identification of Starter Cake Isolates

A total of 1 g of finely ground starter cake was suspended in 9 mL sterile distilled water, vortexed, and subjected to 10-fold serial dilution. Aliquots (0.5 mL) of each dilution were spread-plated on PDA and incubated at 28°C for 5 days. Fungal isolates were purified using the streak plate method until pure cultures were obtained.

Molecular identification was performed using DNA sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region for eukaryotic organisms and 16S rRNA gene for prokaryotic organisms. Extracted DNA sequences were analyzed using BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) against the NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) database. Species identification was confirmed when sequence similarity was ≥99% compared to reference sequences.

4.2.2. Sweet Fermented Rice Preparation

Glutinous rice fermentation: A total of 500 g of glutinous rice was washed with tap water and soaked in filtered water for 6 hours, then steamed for 45 minutes. After cooling, the rice was rinsed with filtered water to remove excess starch. The cooked rice was spread on sterile trays in a laminar flow hood for 15 minutes to achieve appropriate moisture content. Six grams of pulverized starter cake were thoroughly mixed with the cooled rice under aseptic conditions. The inoculated rice was transferred to sterile glass bottles and incubated at 32°C for 48 hours.

LPC rice fermentation: A total of 500 g of LPC rice was washed with filtered water and cooked using an electric rice cooker. Following the same cooling and mixing procedures as described above, the cooked LPC rice was inoculated with 6 g of starter cake powder and incubated under identical conditions.

4.2.3. Chemical Analyses

pH Measurement

The pH of fermented rice samples was homogenized with deionized water (1:1 w/v), vortexed for 30 seconds, and centrifuged at 4,800 rpm for 10 minutes. The supernatant was filtered through membrane filtration before pH measurement using a C1010 multi-parameter analyzer (Consort bvba, Turnhout, Belgium). All measurements were performed in triplicate.

Total Soluble Solids Determination

Total soluble solid content (°Brix) was measured in extracted juice using an Atago PAL-1 (3810) Digital Hand-held Pocket Refractometer (Tokyo, Japan).

Ethanol Quantification

Ethanol content was determined using Headspace—Gas Chromatography with Flame Ionization Detection (HS-GC/FID) on an Agilent 6850 system (Agilent Technologies, USA). Headspace parameters: sample size: 1 g in 20 mL headspace vials with the incubation temperature: 80°C for 30 minutes; mixing: 500 rpm during incubation. Separation was achieved using an HP INNOWAX column [30 m × 0.32 mm × 0.25 μm film thickness]. Sample injection (1 μL) was performed in split mode (50:1 ratio). Operating conditions included helium carrier gas (10 mL/min), hydrogen (30 mL/min), air (300 mL/min), injector temperature (180°C), and detector temperature (250°C). The oven temperature program started at 50°C (9 min hold) and ramped to 200°C at 5°C/min, with a final hold for 2 minutes. Total run time was 39 minutes. Ethanol identification confirmed by retention time matching with authentic standard and co-injection verification.

Lactic Acid Determination

Lactic acid content was analyzed using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) on an Agilent 1200 series system (USA) equipped with a diode array detector (210 nm detection wavelength). Separation was performed using a LiChrospher 100 RP-18 column (250 × 4.0 mm, 5 μm particle size). The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% phosphoric acid in water at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. Injection volume was 20 μL, with column temperature maintained at 25°C, and the run time was 20 minutes.

Sample preparation involved centrifugation of the fermented product liquid at 4,800 rpm for 10 minutes, filtration through 0.22 μm membrane filters, and 50-fold dilution with deionized water. Sodium L-lactate (98% purity, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) served as the analytical standard. The limit of quantification (LOQ) was 5 mg/L. Concentrations were determined using peak area integration and external standard calibration.

Volatile Compound Analysis

Volatile compounds were identified using Gas Chromatography—Tandem Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS/MS) on an Agilent 7890B GC-7000D MS system via Headspace—Solid Phase Microextraction (HS-SPME-GC-EI/MS). A Carboxen/DVB/PDMS fiber (2 cm, 50/30 μm, StableFlex™, Agilent Technologies) was used for extraction.

Optimized extraction conditions included the following: incubation temperature: 80°C; incubation time: 30 minutes; extraction time: 10 minutes; and desorption time: 2 minutes. Sample aliquots (1 mL) were placed in 20 mL SPME vials sealed with PTFE/silicone septa.

Chromatographic separation utilized an Agilent CP9205 VF-WAXms capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) with helium carrier gas (1 mL/min constant flow, 7.0699 psi). Instrument parameters: electron ionization: 70 eV; splitless injection at 250°C, oven temperature program from 40°C (1 min) to 110°C at 5°C/min, then to 250°C at 8°C/min with a 5-minute final hold. Compound identification was performed by spectral matching against the Wiley 10, NIST 14, and NIST 17 databases, with accepted match scores ≥95%

Relative peak area percentages were calculated as follows:

Results were expressed as relative peak area percentages normalized to total volatile compound content [

39]. While absolute quantification requires individual calibration curves for each compound, the comparative approach provides reliable relative abundance data suitable for variety comparison studies. The analytical work was conducted at an ISO/IEC 17025 accredited laboratory, which provides additional assurance of analytical quality, method validation, and result reliability beyond individual technique validation.

Mineral Content Analysis

Fermented rice samples were oven-dried at 70°C and ground to pass through a 40-mesh sieve. Nitrogen content was determined by Kjeldahl digestion, distillation, and titration. Other mineral elements (P, S, K, Ca, Mg, Fe, Cu, Zn, Na) were analyzed following Momen

et. al. [

40].

Samples were incinerated in a muffle furnace (Carbolite AAF 1100) at 550°C for 5 hours. Ash samples were dissolved in 10 mL of 1 N HCl and analyzed using Inductively Coupled Plasma—Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES, Perkin Elmer AVIO 500).

Proximate Composition Analysis

Proximate composition, including moisture, ash, protein, fat, and dietary fiber, was determined using standard AOAC methods. Moisture content was measured using a hot air circulating oven at 70°C. Ash content was determined gravimetrically by incineration at 550±5°C (AOAC Method 930.05) [

41]. Total protein content was determined by the Kjeldahl method (AOAC Method 978.04) using a nitrogen conversion factor of 5.95 on a Kjeltec 8400 analyzer (FOSS, Denmark) [

41]. Fat content was determined by acid hydrolysis (4N HCl) followed by petroleum ether extraction (AOAC Method 930.09) using a SoxTec 8000 system (FOSS, Denmark) [

41]. Dietary fiber was determined according to AOAC Method 930.10 [

41]. Total carbohydrate content was calculated by difference, as follows:

Caloric Value Determination

Food energy values (kcal/100 g) were calculated using Atwater conversion factors, namely, protein (4 kcal/g), carbohydrate (4 kcal/g), and fat (9 kcal/g):

4.2.4. Physical Characterization

Color Measurement

Color parameters were measured using a Hunter Lab Colorimeter (Chroma Meter CR-400, Konica Minolta, Japan) and recorded as L*, a*, and b* values, where L* represents lightness (0-100 scale), a* represents green (-) to red (+) chromaticity, and b* represents blue (-) to yellow (+) chromaticity.

4.2.5. Microbiological Analyses

Microbial Identification of Final Products

Pure cultures were isolated from fermented products using the cross-streak method on nutrient agar plates. Microorganisms were identified using MALDI-TOF MS (MALDI Biotyper, Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Germany).

Microbiological Quality Assessment

Microbiological quality was evaluated according to Thai Community Product Standard (TCPS 162/2003) for Khao Mak [

17]. Escherichia coli, total coliforms, yeasts, and molds were enumerated using 3M™ Petrifilm™

E. coli/Coliform Count Plates and Rapid Yeast and Mold Count Plates, respectively.

A total of 25 g of sample was homogenized with 225 mL sterile buffered peptone water and subjected to 10-fold serial dilutions. One milliliter aliquot at dilutions of 10⁻¹, 10⁻², and 10⁻³ were plated on Petrifilm and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours (E. coli) and 28°C for 3—5 days (yeast and mold). Results were expressed as colony-forming units per gram (CFU/g).

4.2.6. Antioxidant Activity Determination

Free radical scavenging activity was assessed using the DPPH assay according to Seethalaxmi

et al. [

42]. A clarified supernatant, obtained by centrifugation (4,800 rpm, 10 min) and filtration (0.22 μm), was used for analysis.

Sample aliquots (2 mL) at various concentrations were mixed with 5 mL of 0.1 mM methanolic DPPH solution, vortexed, and incubated in darkness at room temperature for 30 minutes. Absorbance was measured at 517 nm using a UV—visible spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). BHT (butylated hydroxytoluene) served as positive control.

Free radical scavenging activity was calculated as follows:

Where

A₀ = absorbance of control (DPPH only)

A₁ = absorbance of sample + DPPH

A₂ = absorbance of sample blank.

IC₅₀ values representing 50% inhibition were determined by plotting inhibition percentage against concentration. All measurements were performed in triplicate.

4.2.7. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were conducted in triplicate, with the results expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 23.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data normality was assessed using the Shapiro—Wilk test. Temporal changes within each rice variety were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Duncan’s multiple range test for post hoc comparisons. Between-variety comparisons at each time point were analyzed using independent samples t-test after confirming variance homogeneity with Levene’s test. Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

5. Conclusions

This comprehensive study demonstrates the feasibility of sweet fermented Lueang Patew Chumphon rice (SFLPC) as a functional food alternative to traditional glutinous rice fermentation products. The research reveals that SFLPC exhibits distinctive characteristics across multiple quality parameters, establishing its potential for commercial development and health-conscious consumer applications.

The fermentation process successfully transforms high-amylose LPC rice into a product with enhanced nutritional properties. Notable improvements include mineral content enhancement with phosphorus increasing by 847 mg/kg (32% increase), potassium by 1,205 mg/kg (28% increase), and magnesium by 312 mg/kg (45% increase) compared to traditional fermented glutinous rice. Protein retention remained favorable at 10.53% versus 9.07% in the control (1.46 percentage points difference). Antioxidant activity demonstrated substantial activity with IC₅₀ values of 3.3 μg/mL, representing a quantifiable difference from conventional fermented glutinous rice products.

The volatile compound profile of SFLPC revealed distinct compositional differences, characterized by higher relative concentrations of fusel alcohols (3.2-fold increase in 3-methyl-1-butanol) and specific unsaturated fatty acid esters compared to traditional products. These differences contribute to the unique aromatic characteristics of SFLPC. However, it should be noted that volatile compound profiles serve as analytical indicators only, and comprehensive sensory evaluation would be necessary to validate actual consumer perception and organoleptic properties.

The microbial succession pattern, involving Aspergillus sp., Rhizopus stolonifer, Candida tropicalis, and Pediococcus pentosaceus, demonstrates successful adaptation of traditional fermentation techniques to high-amylose substrates. Fermentation endpoints (pH ~3.5, ethanol ~3.6% v/v, lactic acid >6 μg/L) were comparable to traditional processes, confirming process viability while maintaining food safety standards.

The application of traditional fermentation to underutilized LPC rice represents a sustainable approach to functional food development that preserves cultural heritage while addressing modern nutritional needs. SFLPC’s combination of enhanced mineral bioavailability, notable antioxidant properties, and distinct aromatic complexity positions it as a viable alternative to conventional fermented rice products.

These findings support the commercial potential of SFLPC for health-conscious consumers seeking traditional foods with enhanced nutritional profiles. The methodology established in this study provides a framework for valorizing other underutilized high-amylose rice varieties through traditional fermentation processes, contributing to agricultural sustainability and functional food innovation.

Research Limitations and Future Directions

This study focuses on chemical characterization without sensory validation. To advance from analytical characterization to functional food applications, systematic validation through targeted compounds and multi-assay antioxidant testing; (2) mechanistic studies including genomic and enzymatic validation of microbial contributions; (3) comprehensive sensory evaluation with trained panels and consumer acceptance testing to correlate analytical findings with actual organoleptic properties; (4) in vivo bioavailability and health benefit validation studies; and (5) scalable production protocol development for commercial application.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.K.; methodology, C.K. and P.N.; validation, C.K. and P.N.; formal analysis, C.K. and P.N.; investigation, C.K.; resources, C.K.; data curation, C.K. and P.N.; writing—original draft preparation, C.K. and P.N.; writing—review and editing, C.K.; visualization, C.K.; supervision, C.K.; project administration, C.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Reported as an exemption

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Laboratory of Microbiology, the Laboratory of Food Innovation, and the Laboratory of Materials and Equipment at King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology Ladkrabang, Prince of Chumphon Campus, Chumphon Province, Thailand, as well as the Office of Scientific Instruments and Testing at Prince of Songkhla University, Hat Yai District, Songkhla Province, Thailand, for their technical support and facilities. Special thanks are extended to Bang Son Subdistrict Community Enterprise for generously providing the Lueang Patew Chumphon rice variety used in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

References

-

https://fas.usda.gov/data/thailand-grain-and-feed-annual-7 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

-

https://www.rakbankerd.com/agriculture/print.php?id=523&s=tblrice (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- The registration of geographical indications; Khao Leuang Patew Chumphon. http://new.research.doae.go.th/GI/uploads/documents/ (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Tao, K.; Yu, W.; Prakash, S.; Gilbert, R.G. High-amylose rice: Starch molecular structural features controlling cooked rice texture and preference. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 219, 251-260. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yoshimura, K.; Sasaki, M.; Maruyama, K. The Consumption of High-Amylose Rice and its Effect on Postprandial Blood Glucose Levels: A Literature Review. Nutrients 2024, 16(23), 4013; [CrossRef]

- Petchalanuwat, C.; Mongkonbunjong, P.; Arayarungsarit, L.; Kongseree, Ng. Hirunyupakorn, V. Physico-Chemical Properties of 8 White Rice Varieties. Thai Agri. Res. J. 2000, 18(2), 164-169.

- Wongpiyachon, S.; Songchitsomboon, S.; Wasusun, A.; Sukviwat, W.; Maneenin, P. Glycemic Index of 12 Thai Rice Varieties. Thai Rice Res. J. 2017, 8(2), 54-69.

- Thadamatakul, P.; Songsiri, P.; Techasukthavorn, V. Three Rice of Thailand on Blood Glucose Control. Thai JPEN 2021, 29(1), 24-33.

- Phapumma, A.; Monkham, T.; Sanitchon, J.; Chankaew, S. Evaluation of Amylose Content, Textural Properties and Cooking Quality of Selected Glutinous Rice. Khon Kaen Agr. J. 2020, 48(3), 597-606.

- Foster-Powell, K.; Holt, S.H.,A.; Brand-Miller, J.C. International table of glycemic index and glycemic load values. Am J Clin Nutr 2002, 76(1), 5-56.

- Pasakawee, K.; Laokuldilok, T.; Srichairatanakool, S.; Utama-ang, N. Relationship among Starch Digestibility, Antioxidant, and Physicochemical Properties of Several Rice Varieties using Principal Component Analysis. Curr. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2018, 18(3), 133-144.

- Cheirsilp, B.; Satansat, J.; Wanthong, K.; Chaiyasain, R.; Rakmai, J.; Suwannarach, N.; Kumla, J.; Pathom-aree, W.; Wang, G.; Srinuanpan, S. Bioprocess Improvement for fermentation of pigmented Thai glutinous rice-based functional beverage (Sato) with superior antioxidant properties. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2023, 50, 102701. [CrossRef]

- Park, M.K.; Kim, Y.S. Distinctive Formation of Volatile Compounds in Fermented Rice Inoculated by Different Molds, Yeasts, and Lactic Acid Bacteria. Molecules 2019, 24, 2123. [CrossRef]

- LIU, X.; WANG, J.; XU, Z.; SUN, J.; LIU, Y.; XI, X.; MA, Y. Quality assessment of fermented soybeans: physicochemical, bioactive compounds and biogenic amines. Food Sci. Technol, Campinas, 2023, 43. [CrossRef]

- Duan, B.; Chang, W.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, M.; Su-Zhou, C.; Merkeryan, H.; Xu, M.; Liu, X. Characterization of volatile compounds and sensory properties of spine grape (Vitis davidii Foex) brandies aged with different toasted wood chips. Food Chem:X 2024, 23, 101777. [CrossRef]

-

http://www.cie.co.at/cie/ (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Ministry of Industry. 2003. Community product standard of sweet fermented glutinous rice. Document of CPS at 162/2003. Agro product standard office, Bangkok, Thailand.

- Rhee, S.J.; Lee, J.E.; Lee, C.H. Importance of lactic acid bacteria in Asian fermented foods. Microb Cell Fact. 2011, 10(Suppl 1):S5, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Hetényi, K.; Németh, Á.; Sevella, B. Role of pH-regulation in lactic acid fermentation: Second steps in a process improvement. Chem. Eng. Process. 2011, 50(3), 293-299.

- Cichońska, P.; Ziębicka, A.; Ziarno, M. Properties of Rice-Based Beverages Fermented with Lactic Acid Bacteria and Propionibacterium. Molecules 2022, 27, 2558. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Tang, X.; Qian, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Wu, Q.; Mu, Y.; Huang, Z. Analysis of Saccharification Products of High-Concentration Glutinous Rice Fermentation by Rhizopus nigricans Q3 and Alcoholic Fermentation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae GY-1. ACS Omega. 2021, 6, 8038–8044. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Chen, X.; Rui, X.; Li, W.; Li, T.; Xu, X.; Dong, M. Use of fermented glutinous rice as a natural enzyme cocktail for improving dough quality and bread staling. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 11394-11402. [CrossRef]

- Rini; Yenrina, R.; Anggraini, T.; Chania, N.E. The Effects of Various Way of Processing Black Glutinous Rice (Oryza sativa L. Processing Var Glutinosa) on Digestibility and Energy Value of the Products. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ Sci. 2019, 327, 012013. [CrossRef]

- Determining Ethanol in Fermented Glutinous Rice. (November 2018): https://www.ukessays.com/essays/chemistry/determining-ethanol-fermented-glutinous-1694.php?vref=1. (Accessed 29 January 2025).

- Frohman, C.A.; Mira de Orduña, R. Cellular viability and kinetics of osmotic stress associated metabolites of Saccharomyces cerevisiae during traditional batch and fed-batch alcoholic fermentations at constant sugar concentrations. Food Res. Int. 2013, 53, 551-555.

- Zhang, Y.; Chang, C.H.; Fan, X.H.; Zuo, T.T.; Jiao, Z. Effect of the initial glucose concentration on the performance of rice wine fermentation of Vidal grape juice. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 31341. [CrossRef]

- Zentou, H.; Abidin, Z.Z.; Yunus, R.; Biak, D.R.A.; Issa, M.A.; Pudza, M.Y. A New Model of Alcoholic Fermentation under a Byproduct Inhibitory Effect. ACS Omega. 2021, 6, 4137–4146. [CrossRef]

- Mugula, J.K.; Narvhus, J.A.; Sørhaug, T. Use of starter cultures of lactic acid bacteria and yeasts in the preparation of togwa, a Tanzanian fermented food. Int J Food Microbiol. 2003, 83, 307-18. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.M.; Faia, A.M. The Role of Yeasts and Lactic Acid Bacteria on the Metabolism of Organic Acids during Winemaking. Foods. 2020, 9, 1231; [CrossRef]

- Lee , S.M.; Lim , H.J.; Chang, J.W.; Hurh , B.S.; Kim, Y.S. Investigation on the formations of volatile compounds, fatty acids, and γ-lactones in white and brown rice during fermentation. Food Chem. 2018, 15, 347-354. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhang, C.; Liu, K. et al. Volatile Organic Compounds, Evaluation Methods and Processing Properties for Cooked Rice Flavor. Rice. 2022, 15, 53. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Pan, Z.; Lu, Z.; Wang, S.; Liu, W.; Wang, X.; Wu, H.; Chen, H.; Chen, T.; Hu, J.; He, X. Analysis of Volatile Compounds’ Changes in Rice Grain at Different Ripening Stages via HS-SPME-GC–MS. Foods. 2024, 13, 3776. [CrossRef]

- Shano, H.F.; Kumaran, T.; Mary, T.S.; Tamizharasi, M.J.; Rajila, R.; Sujithra, S.; Shiny, B. Nutritional Analysis and Antimicrobial Activity of Fermented Rice Water. Der Pharma Chemica, 2021, 13, 9-13.

- Koni, T N I.; Paga, A.; Asru. Calcium, phosphorus, and phytic acid of fermented rice bran. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ Sci. 2024, 1360, 012010. [CrossRef]

- Khatun, L.; Ray, S.; Brahma, R.; Boruah, D.C. Development of a fermented rice product (Pachoi): Evaluation of vitamin and mineral composition, microbiological investigation and shelf-life stability. Food Hum. 2025, 5. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Cai, L.; Lv, L.; Li, L.; Pediococcus pentosaceus, a future additive or probiotic candidate. Microb. Cell Fact. 2021, 20, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Huang, L.; Zeng, Y.; Li, W.; Zhou, D.; Xie, J.; Xie, J.; Tu, Q.; Deng, D.; Yin, J. Pediococcus pentosaceus: Screening and Application as Probiotics in Food Processing. REVIEW article. Front. Microbiol., 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Fuloria, S.; Mehta, J.; Talukdar, M.P.; Sekar, M.; Gan, S.H.; Subramaniyan, V.; Rani, N.N.I.M.; Begum, M.Y.; Chidambaram, K.; Nordin, R.; Maziz, M.N.H.; Sathasivam, K.V.; Lum, P.T.; Fuloria, N.K. Synbiotic Effects of Fermented Rice on Human Health and Wellness: A Natural Beverage That Boosts Immunity. Front Microbiol. 2022, 13, 950913. [CrossRef]

- Dias, L.; Duarte, G.; Mariutti, L.; Bragagnolo, N. Aroma profile of rice varieties by a novel SPME method able to maximize 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline and minimize hexanal extraction. Food Res. Int. 2019, 123, 550–558.

- Momen, A.A.; Zachariadis, G.A.; Anthemidis, A.N.; Stratis, J.A. Use of fractional factorial design for optimization of digestion procedures followed by multi-element determination of essential and non-essential elements in nuts using ICP-OES technique. Talanta 2007, 71, 443-451. [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis, 18th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists, Washington, DC, USA, 2005.

- Seethalaxmi, M.S.; Shubharani, R.; Nagananda, G.S.; Sivaram, V. Phytochemical analysis and free radical scavenging potential of Baliospermum montanum (Willd.) Muell. Leaf. Asian J Pharm Clin Res 2012, 5(2), 135-137.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).