Submitted:

01 September 2025

Posted:

01 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

2.1.1. Acquisition and Hatching of the Fertilized Eggs

2.1.2. Factory Cultivation of the Larvae

2.2. Sampling and Observation

2.3. Statistics

3. Results

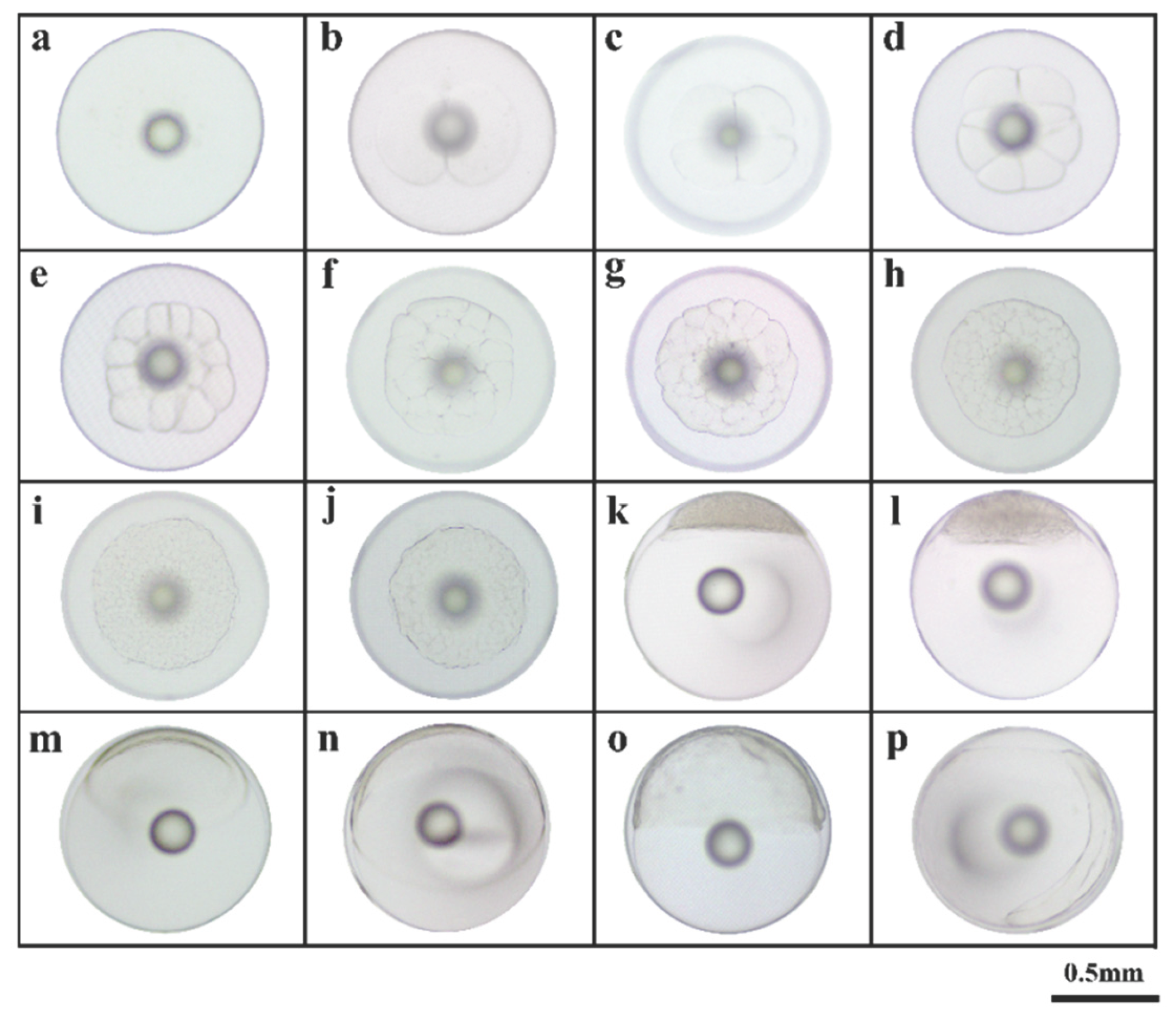

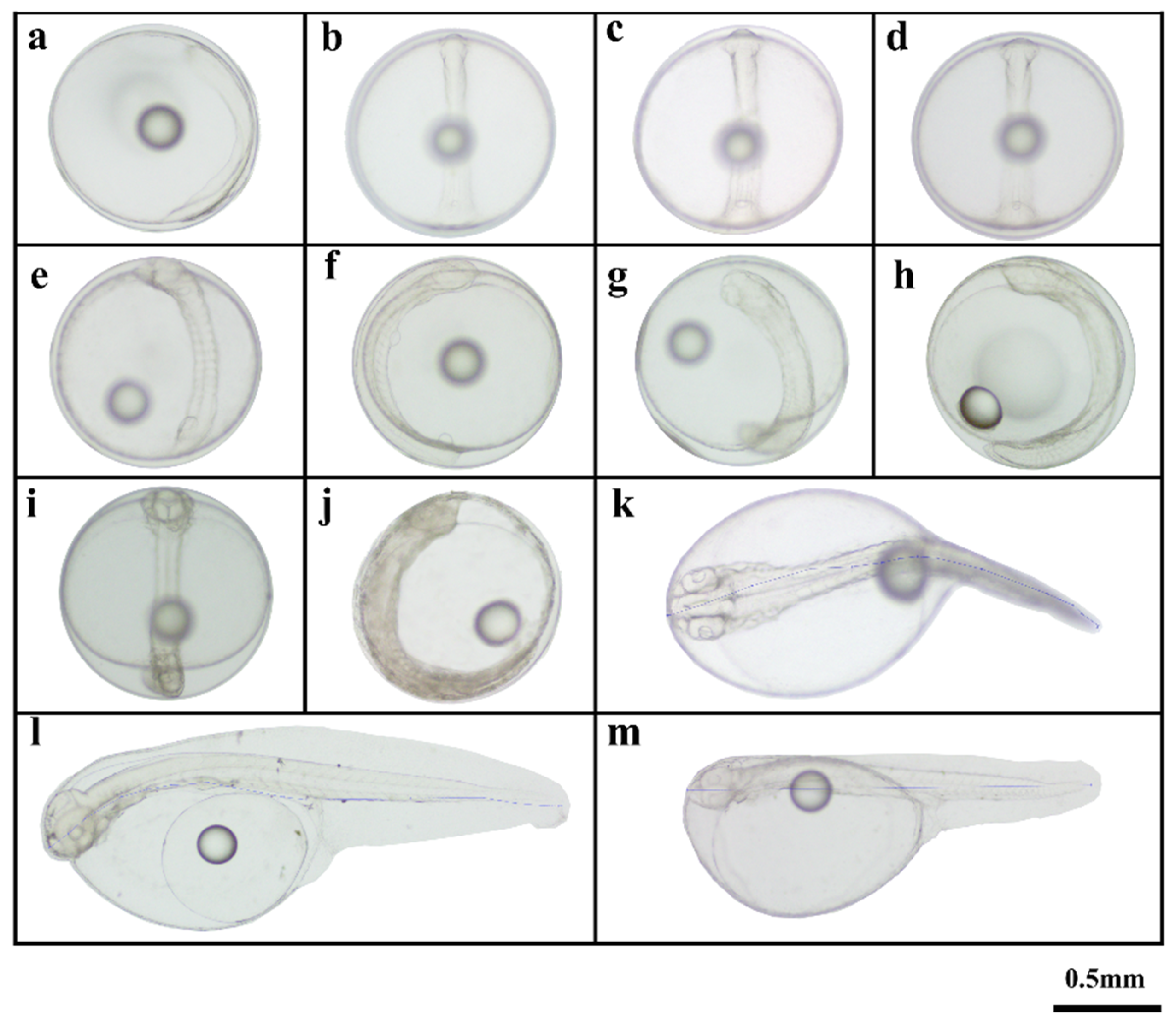

3.1. Development of the Fertilized Eggs

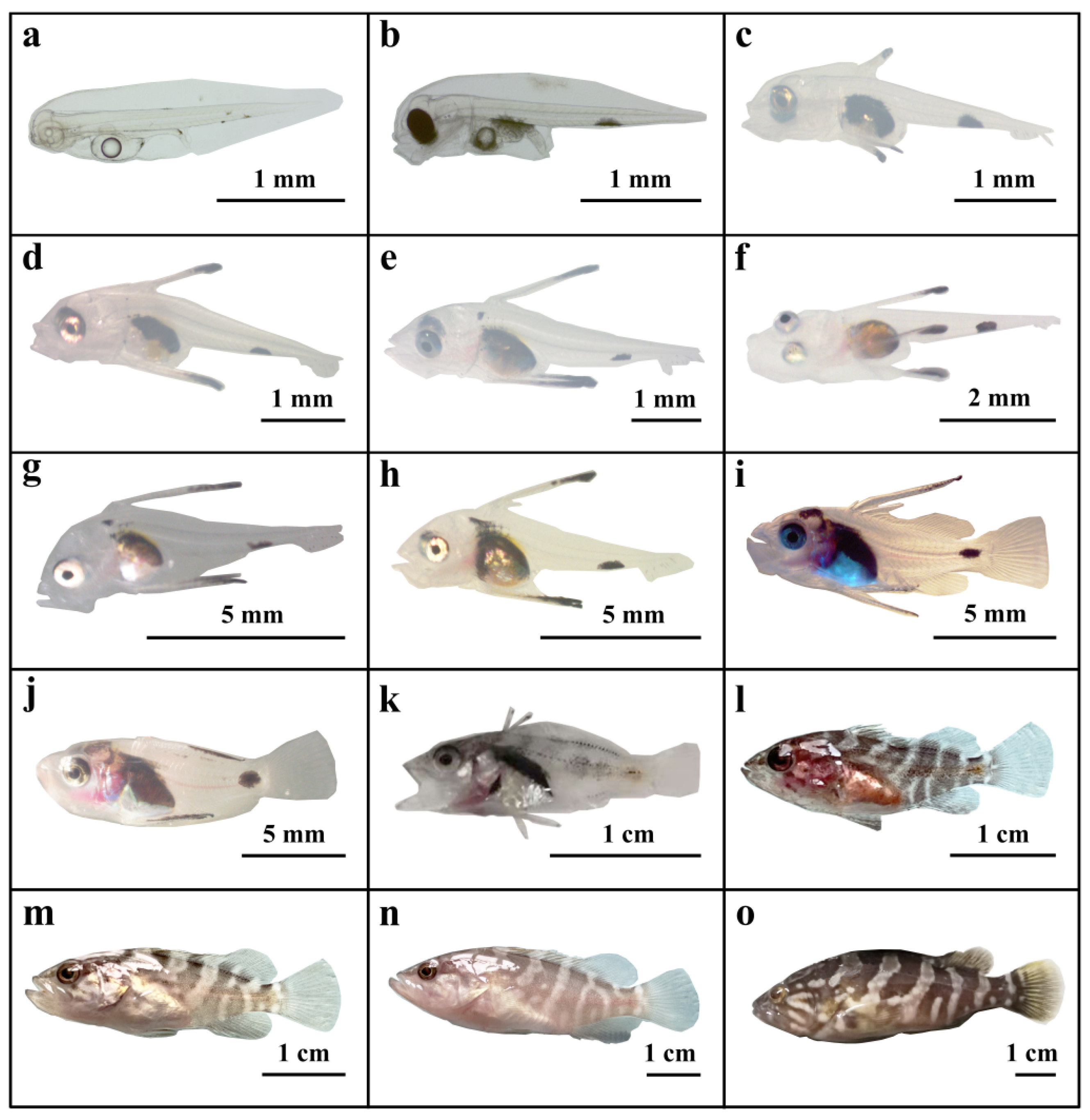

3.2. Characteristics of the Hatched Larvae

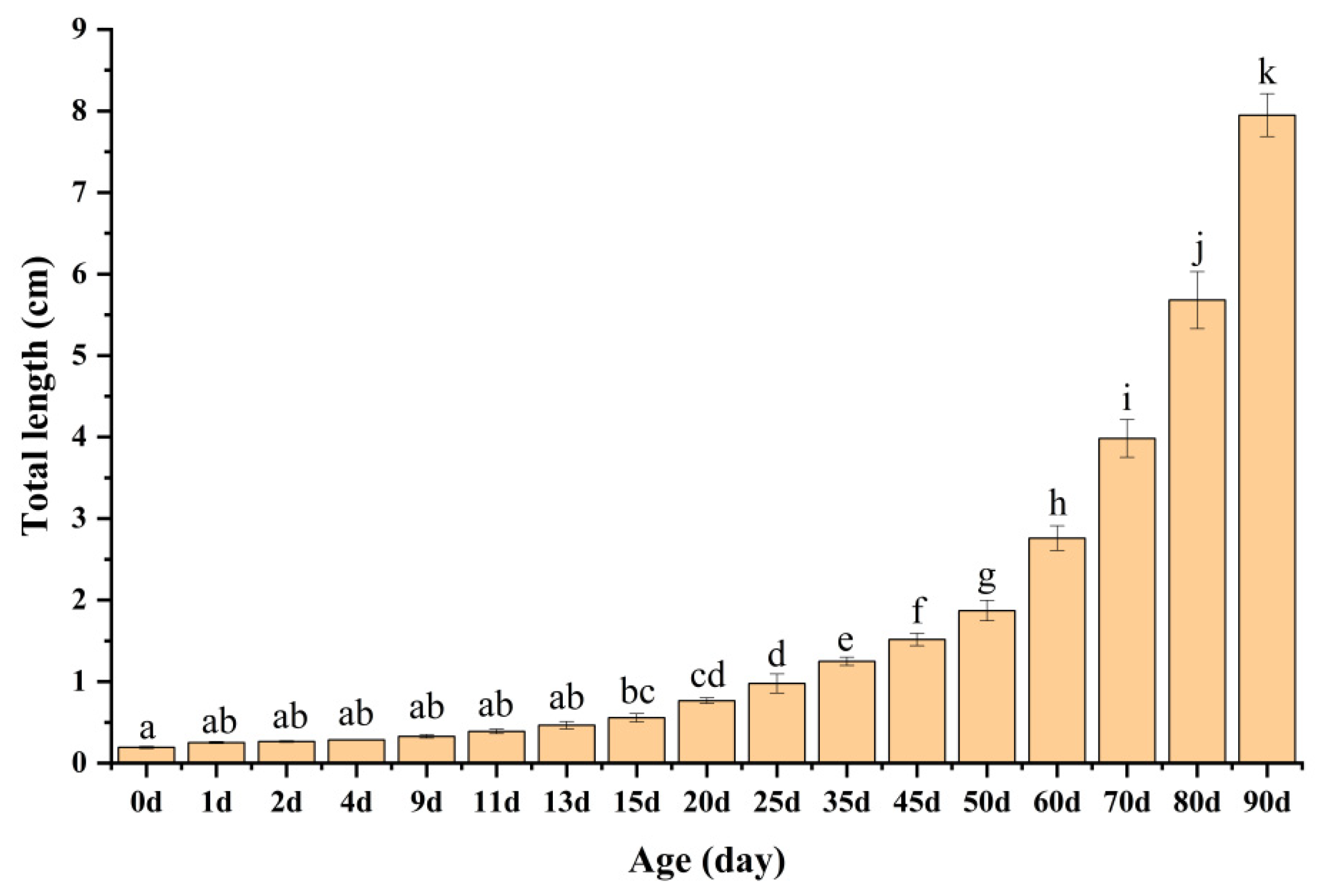

3.3. Growth Changes in the Larvae

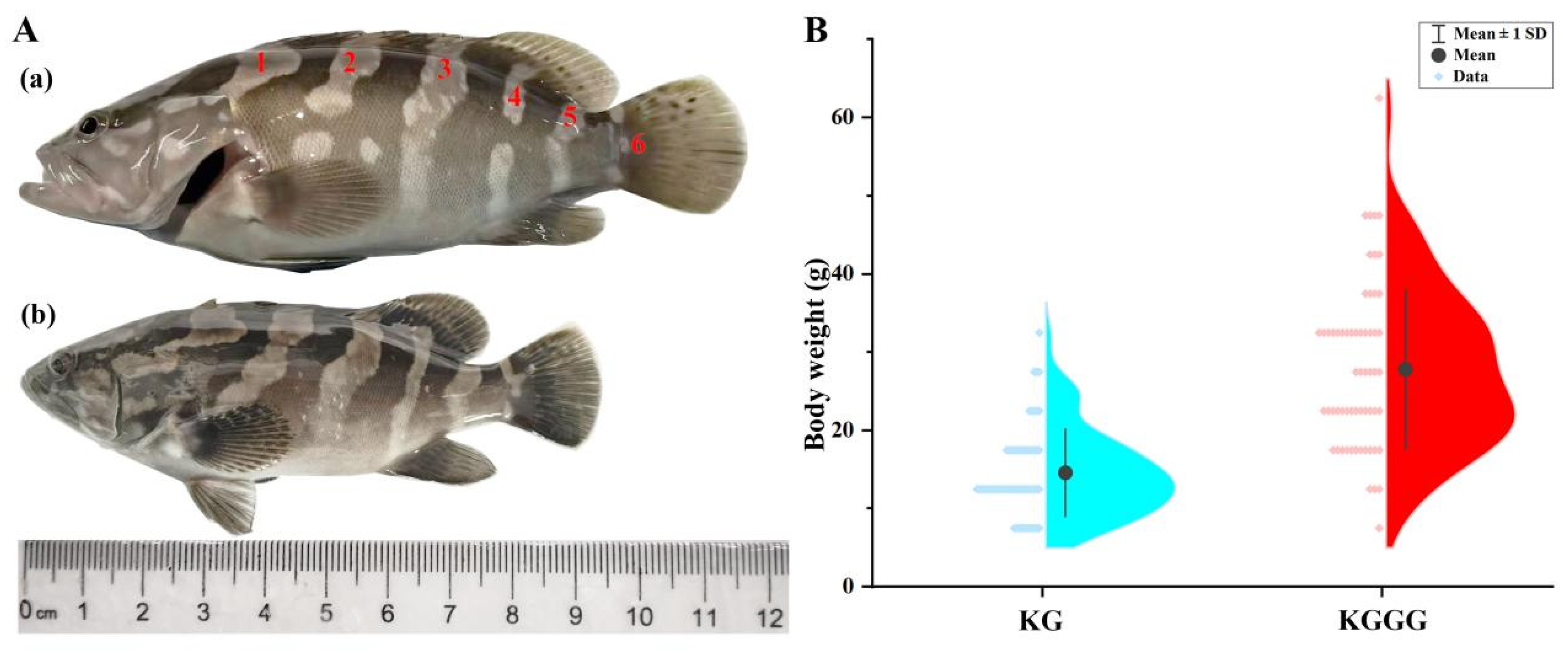

3.4. Comparison Between the Development of the Offspring and Maternal Groupers

4. Discussion

4.1. Fertilization and Hatching Rates

4.2. Egg Development and Hatching Time

4.3. Growth

4.4. Comparative Analysis with the Maternal Broodstock Grouper

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| KG | Epinephelus moara |

| KGGG | Epinephelus moara ♀ × Epinephelus lanceolatus ♂ |

| dAH | days after hatching |

| hAF | hours after fertilization |

| GG | Epinepheluslanceolatus |

| OGGG | Epinephelus coioides ♀ × Epinephelus lanceolatus ♂ |

| TG | Epinephelusfuscoguttatus |

| TGGG | Epinephelus fuscoguttatus ♀ × Epinephelus lanceolatus ♂ |

| LGGG | Epinephelus bruneus ♀ × Epinephelus lanceolatus ♂ |

| OGTG | Epinephelus coioides ♀ × Epinephelus fuscoguttatus ♂ |

| CGTG | Epinephelus corallicola ♀ × Epinephelus fuscoguttatus ♂ |

References

- Yang, Y.; Wang, T.; Chen, J.; Wu, X.; Wu, L.; Zhang, W.; Luo, J.; Xia, J.; Meng, Z.; Liu, X. First construction of interspecific backcross grouper and genome-wide identification of their genetic variants associated with early growth. Aquaculture 2021, 545, 737221. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Guo, C.-Y.; Wang, D.-D.; Li, X. F.; Xiao, L.; Zhang, X.; You, X.; Shi, Q.; Hu, G.-J.; Fang, C. Transcriptome analysis reveals the molecular mechanisms underlying growth superiority in a novel grouper hybrid (Epinephelus fuscogutatus♀× E. lanceolatus♂). BMC genetics 2016, 17 (1), 24. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ye, Z.; Yu, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, P.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y. The complete mitochondrial genome of the hybrid grouper (Cromileptes altivelis♀× Epinephelus lanceolatus♂) with phylogenetic consideration. Mitochondrial Dna Part B 2017, 2 (1), 171-172. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, P.; Wei, R.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, L. The complete mitochondrial genome of the hybrid grouper Epinephelus akaara ♀× Epinephelus lanceolatus ♂. Mitochondrial DNA Part B 2018, 3 (2), 599-600.

- Cheng, M.; Tian, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Pang, Z.; Ma, W.; Zhai, J. The complete mitochondrial genome of the hybrid offspring Epinephelus fuscoguttatus♀× Epinephelus tukula♂. Mitochondrial DNA Part B 2019, 4 (2), 2717-2718.

- Lu LiJun, L. L.; Chen Chao, C. C.; Ma AiJun, M. A.; Zhai JieMing, Z. J.; Wang XinAn, W. X.; Li WeiYe, L. W. Studies on the feeding behavior and morphological developments of Epinephelus moara in early development stages. 2011.

- Chan, N. W. W.; Johnston, B. Applying the triangle taste test to wild and cultured humpback grouper (Cromileptes altivelis) in the Hong Kong market. SPC Live Reef Fish Information Bulletin 2007, 17, 31-35.

- Chen, Z. F.; Tian, Y. S.; Wang, P. F.; Tang, J.; Liu, J. C.; Ma, W. H.; Li, W. S.; Wang, X. M.; Zhai, J. M. Embryonic and larval development of a hybrid between kelp grouper Epinephelus moara♀× giant grouper E. lanceolatus♂ using cryopreserved sperm. Aquaculture Research 2018, 49 (4), 1407-1413.

- Bhandari, R. K.; Komuro, H.; Nakamura, S.; Higa, M.; Nakamura, M. Gonadal restructuring and correlative steroid hormone profiles during natural sex change in protogynous honeycomb grouper (Epinephelus merra). Zoological science 2003, 20 (11), 1399-1404. [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.Y.; Li, Z. T.; Duan, P.F.; Qiu Y.S.; Wang, X.Y.; Li, L.L.; Wang, L.N.; Liu,Y.; Li, W.S.; Wang, Q.B.; Zhao, X.; Tian, Y.S.; Li, Z.T. Effects of long-term cryopreservation on ultrastructure and enzyme activity of Epinephelus lanceolatus sperm. Journal of Fisheries of China 2023, 47(7): 079605.

- Sariat, S. A.; Ching, F. F.; Faudzi, N. M.; Senoo, S. Embryonic and larval development of backcrossed hybrid grouper between TGGG (Epinephelus fuscoguttatus × E. lanceolatus) and giant grouper (E. lanceolatus). Aquaculture 2023, 576, 739833.

- Tan, J. Backcross breeding between TGGG hybrid grouper (Epinephelus fuscoguttatus × E. lanceolatus) and giant grouper (E. lanceolatus). Journal of Survey in Fisheries Sciences 2021, 7 (2), 49-62. [CrossRef]

- Aoki, R.; Matsumasa, T.; Kumada, T.; Jin, N.; Masuma, S. Hatchability and growth performance of F1, F2, and backcross progenies of Epinephelus bruneus and Epinephelus lanceolatus. Aquaculture International 2025, 33 (4), 291. [CrossRef]

- Ching, F. F.; Othman, N.; Anuar, A.; Shapawi, R.; Senoo, S. Natural spawning, embryonic and larval development of F2 hybrid grouper, tiger grouper Epinephelus fuscoguttatus × giant grouper E. lanceolatus. International Aquatic Research 2018, 10 (4), 391-402. [CrossRef]

- Luan, G. H.; Luin, M.; Shapawi, R.; Fui Fui, C.; Senoo, S. Egg development of backcrossed hybrid grouper between OGGG (Epinephelus coioides × Epinephelus lanceolatus) and giant grouper (Epinephelus lanceolatus). Int. J. of Aquatic Science 2016, 7 (1), 13-18.

- Ch’ng, C. L.; Senoo, S. Egg and larval development of a new hybrid grouper, tiger grouper Epinephelus fuscoguttatus × giant grouper E. lanceolatus. Aquaculture Science 2008, 56 (4), 505-512.

- Zhou, L.; Weng, W.; Li, J.; Lai, Q. Studies on embryonic development, morphological development and feed changeover of Epinephelus lanceolatus larva. Chinese Agricultural Science Bulletin 2010, 26 (1), 293-302.

- Addin, A.; Senoo, S. Production of hybrid groupers: spotted grouper, Epinephelus polyphekadion × tiger grouper, E. fuscoguttatus and coral grouper, E. Corallicola × tiger grouper. In 2011 International symposium on grouper culture—technological innovation and industrial development, Taiwan, 2011.

- Koh, I. C. C.; Shaleh, S. R. M.; Senoo, S. Egg and larval development of a new hybrid orange-spotted grouper Epinephelus coioides × tiger grouper E. fuscoguttatus. Aquaculture Science 2008, 56 (3), 441-451.

- Song, Z.; Chen, C.; Zhai, J.; Li, Y.; Ma, W.; Wang, L.; Wu, L. Embryonic development and morphological characteristics of larval, juvenile and young kelp bass, Epinephelus moara. Progress in Fishery Sciences 2012, 33 (3), 26-34.

- Mandić, M.; Regner, S. Variation in fish egg size in several pelagic fish species. Studia Marina 2014, 27 (1), 31-46.

- Yoseda, K.; Dan, S.; Sugaya, T.; Yokogi, K.; Tanaka, M.; Tawada, S. Effects of temperature and delayed initial feeding on the growth of Malabar grouper (Epinephelus malabaricus) larvae. Aquaculture 2006a, 256 (1-4), 192-200. [CrossRef]

- Yoseda, K.; Teruya, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Asami, K. Effects of different temperature and delayed initial feeding on larval feeding, early survival, and the growth of coral trout grouper, Plectropomus leopardus larvae. Aquaculture Science 2006b, 54 (1), 43-50.

- Song, Y.B.; Lee, C.H.; Kang, H.C.; Kim, H.B.; Lee, Y.D. Effect of water temperature and salinity on the fertilized egg development and larval development of sevenband grouper, Epinephelus septemfasciatus. Development & reproduction 2013, 17 (4), 369. [CrossRef]

- Hart, P. J.; Reynolds, J. D.; Hart, P. J.; Reynolds, J. D. Handbook of fish biology and fisheries; Wiley Online Library, 2002.

- Franz, G. P.; Lewerentz, L.; Grunow, B. Observations of growth changes during the embryonic-larval-transition of pikeperch (Sander lucioperca) under near-natural conditions. Journal of Fish Biology 2021, 99 (2), 425-436.

- Rombough, P. The energetics of embryonic growth. Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology 2011, 178 (1), 22-29.

- Wei, L.; Zhu, S.Q.; Liu, W.; Zhao, J.L.; Qian, Y.Z.; Wu, C.; Qian, D. Comparison on morphology and body spots characteristics between backcross progenies and their parents of mandarin fish. South China Fisheries Science 2020, 16 (2): 1-7.

- J. Marshall, D.; Uller, T. When is a maternal effect adaptive? Oikos 2007, 116 (12), 1957-1963.

- de Assis Lago, A.; Rezende, T. T.; Dias, M. A. D.; de Freitas, R. T. F.; Hilsdorf, A. W. S. The development of genetically improved red tilapia lines through the backcross breeding of two Oreochromis niloticus strains. Aquaculture 2017, 472, 17-22. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, Z.; Li, L.; Chen, S.; Duan, P.; Wang, X.; Qiu, Y.; Ding, X.; Su, J. DNA Methylation and Subgenome Dominance Reveal the Role of Lipid Metabolism in Jinhu Grouper Heterosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25 (17), 9740. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Q.; Cheng, M.L.; Wu, Y.P.; Zhang, J.J.; Li, Z.T.; Ma,W.H.; Pang, Z.F.; Zhai J.M.; Tian, Y.S. Early development of hybrids of Epinephelus lanceolatus(♀) × Epinephelus moara(♂) and growth characteristics of reciprocal crosses. Journal of Fisheries of China 2020, 44(3), 436-446.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).