Submitted:

31 August 2025

Posted:

01 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. OS Immune Homeostasis

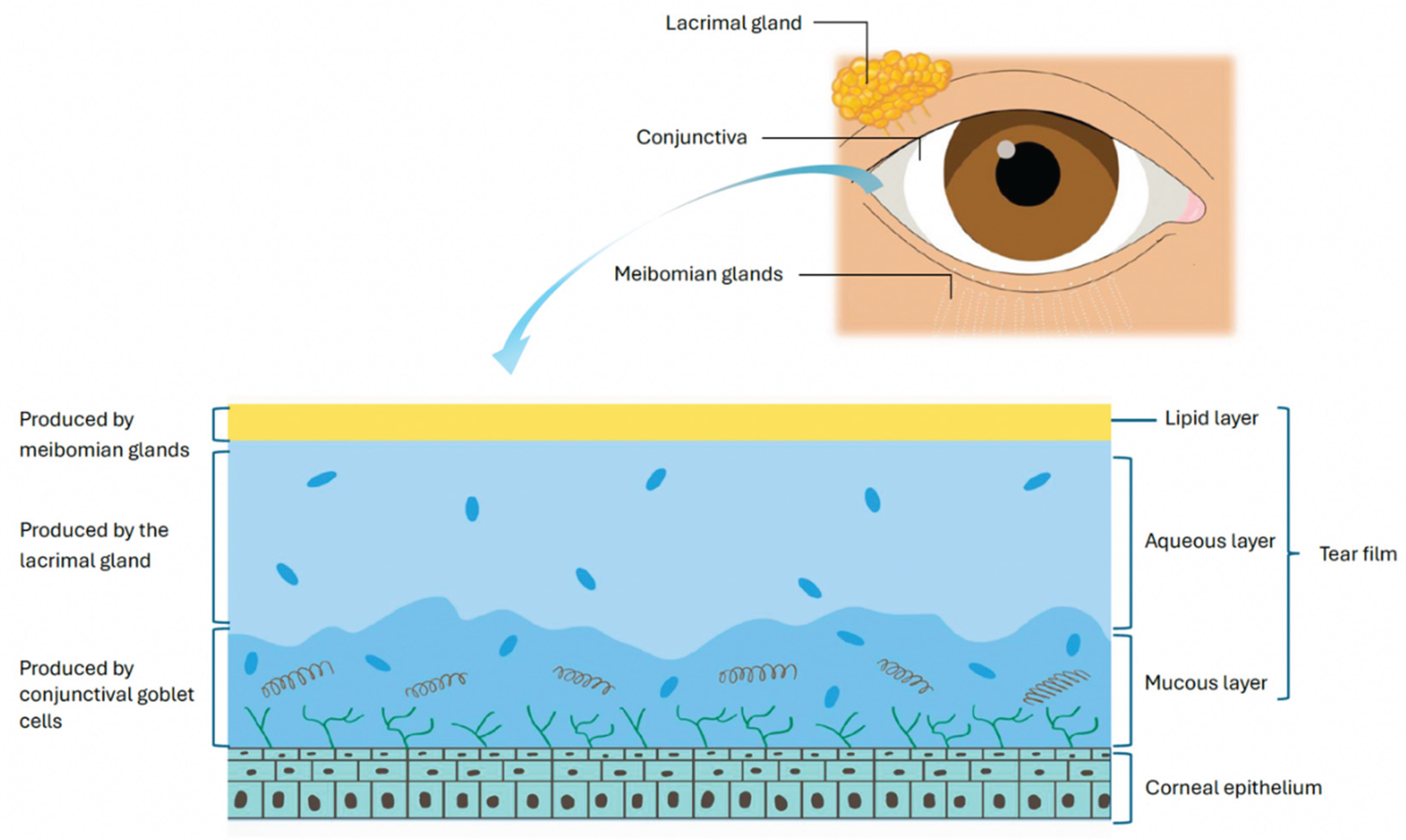

4. Definition and Classification of DED

5. Pathophysiology of DED

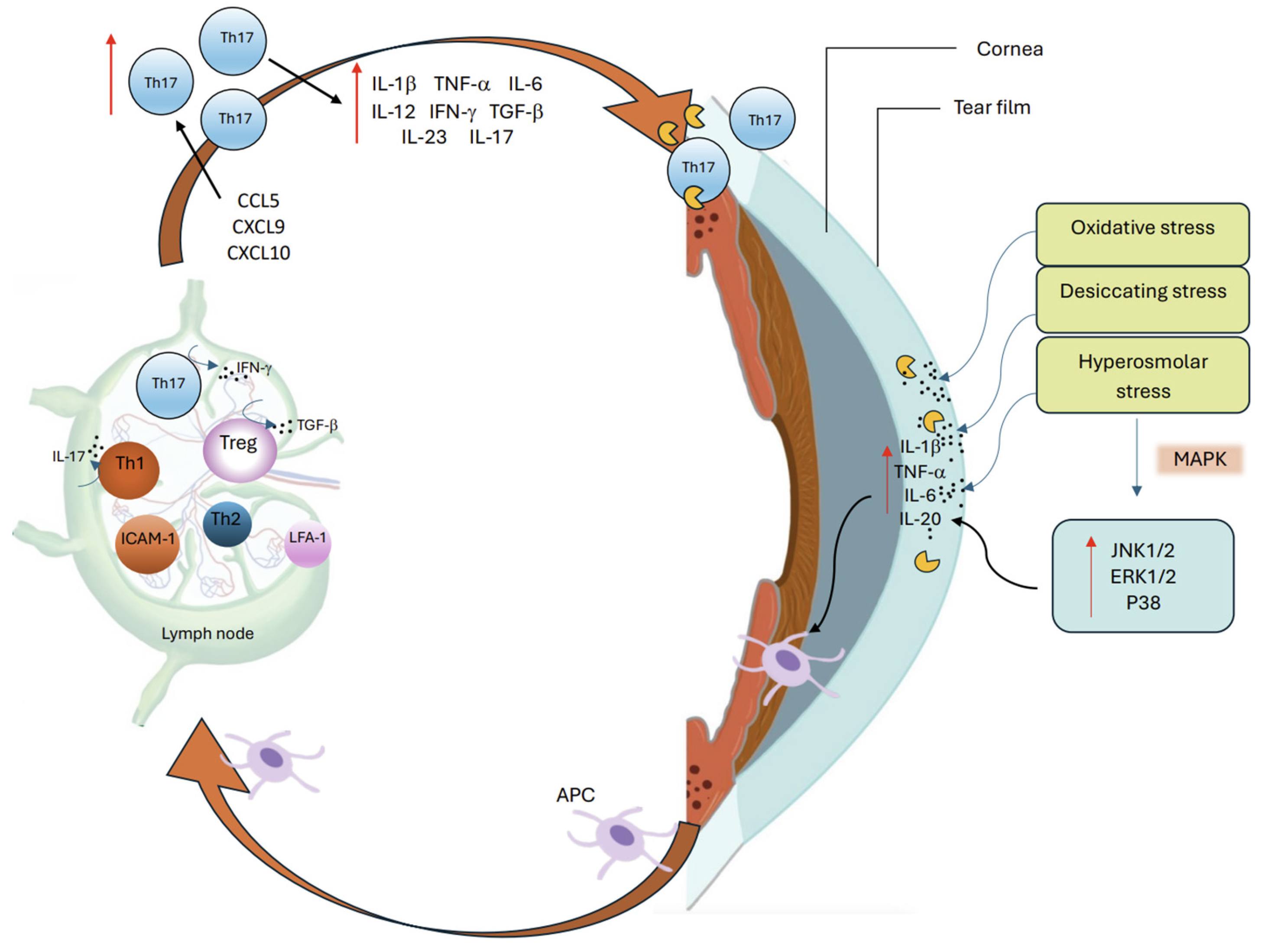

6. Innate Immune System in DED

7. Adaptive Immune System in DED

7.1. Th1 Cells

7.2. Th17 Cells

7.3. Memory T Cells

7.4. Tregs

8. Neuroimmune Mediated Inflammation in DED

9. Tear Biomarkers of DED

10. Therapeutic Implications

11. Conclusions

12. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Term |

| ACPA | Anti-citrullinated protein autoantibodies |

| ADAM17 | A Disintegrin And Metalloproteinase 17 |

| ADDE | Aqueous-deficient dry eye |

| AP-1 | Activator Protein 1 |

| α7nAChR | α7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor |

| BAC | Benzalkonium Chloride |

| BALB/c | BALB/c mouse strain |

| CCL5 | C-C motif chemokine ligand 5 |

| CCR7 | C-C chemokine receptor 7 |

| CGRP | Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide |

| CE-MN | Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)-responsive Microneedle Patch |

| CP-99,994 | N1KR antagonist |

| CXCL9 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 9 |

| DC | Dendritic Cell |

| DAMPs | Danger Associated Molecular Patterns |

| EDE | Evaporative Dry Eye |

| EGCG | Epigallocatechin Gallate |

| FoxP3 | Forkhead Box Protein P3 |

| HMGB1 | High Mobility Group Box 1 |

| HSP-60 | Heat Shock Protein 60 |

| ICAM-1 | Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1 |

| IDO | Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IL-17C | Interleukin 17C |

| IL-17RE | Interleukin 17 Receptor E |

| JNK1/2 | c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1/2 |

| LFA-1 | Lymphocyte Function-Associated Antigen-1 |

| LN | Lymph Nodes |

| MAPKs | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases |

| M1 | Classically activated (pro-inflammatory) macrophage |

| M2 | Alternatively activated (anti-inflammatory) macrophage |

| M2-EVs | M2 Macrophage–Derived Extracellular Vesicles |

| MD2 | Myeloid Differentiation Factor 2 |

| MHC | Major Histocompatibility Complex |

| miR-146a | MicroRNA-146a |

| MSC | Mesenchymal Stem Cell |

| MSC-EVs | MSC-Derived Extracellular Vesicles |

| mADSC-Exos | Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cell Exosomes |

| mRNA | Messenger Ribonucleic Acid |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NFAT5 | Nuclear Factor of Activated T Cells 5 |

| NK | Natural Killer Cells |

| NKT | Natural Killer T Cells |

| NETs | Neutrophil Extracellular Traps |

| NLRP3 | NOD-, LRR- and Pyrin Domain-Containing Protein 3 |

| PAD4 | Peptidylarginine Deiminase 4 |

| PEDF | Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor |

| PI3K-Akt | Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase–Akt |

| Plk1–Cdc25c–Cdk1 | Polo-Like Kinase 1 – Cell Division Cycle 25C – Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 1 |

| PDE4 | Phosphodiesterase Type-4 |

| PD-L1 | Programmed Death Ligand 1 |

| RASγt | Retinoic Acid–Related Orphan Receptor Gamma t |

| RXRα | Retinoid X Receptor Alpha |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RORγt | Retinoic Acid–Related Orphan Receptor Gamma t |

| SDF-1 | Stromal Cell-Derived Factor 1 |

| SP | Substance P |

| STIM1/2 | Stromal Interaction Molecule 1/2 |

| SQSTM1 | Sequestosome 1 |

| STAT3 | Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 |

| Th17GM-CSF | Th-17 Producing Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor |

| TGF | Tumor Growth Factor |

| Tregs | T Regulatory Cells |

| TRPV1 | Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1 |

| ZO-1 | Zonula Occludens-1 |

References

- Britten-Jones, A.C.; Wang, M.T.M.; Samuels, I.; Jennings, C.; Stapleton, F.; Craig, J.P. Epidemiology and Risk Factors of Dry Eye Disease: Considerations for Clinical Management. Medicina (B Aires) 2024, 60, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bron, A.J.; de Paiva, C.S.; Chauhan, S.K.; Bonini, S.; Gabison, E.E.; Jain, S.; Knop, E.; Markoulli, M.; Ogawa, Y.; Perez, V.; et al. TFOS DEWS II Pathophysiology Report. Ocular Surface 2017, 15, 438–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, S.; Alemi, H.; Dohlman, T.; Dana, R. Immune Regulation of the Ocular Surface. Exp Eye Res 2022, 218, 109007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, F.; Argüeso, P.; Argüeso, A.; Asbell, P.; Azar, D.; Bosworth, C.; Chen, W.; Ciolino, J.; Craig, J.P.; Gallar, J.; et al. TFOS DEWS III Digest Report. Am J Ophthalmol 2025, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barabino, S.; Chen, Y.; Chauhan, S.; Dana, R. Ocular Surface Immunity: Homeostatic Mechanisms and Their Disruption in Dry Eye Disease. Prog Retin Eye Res 2012, 31, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periman, L.M.; Perez, V.L.; Saban, D.R.; Lin, M.C.; Neri, P. The Immunological Basis of Dry Eye Disease and Current Topical Treatment Options. Journal of Ocular Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2020, 36, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galletti, J.G.; de Paiva, C.S. Age-related Changes in Ocular Mucosal Tolerance: Lessons Learned from Gut and Respiratory Tract Immunity. Immunology 2021, 164, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, M.E.; Schaumburg, C.S.; Pflugfelder, S.C. Dry Eye as a Mucosal Autoimmune Disease. Int Rev Immunol 2013, 32, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Beuerman, R.W. Tear Analysis in Ocular Surface Diseases. Prog Retin Eye Res 2012, 31, 527–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Paiva, C.S.; St. Leger, A.J.; Caspi, R.R. Mucosal Immunology of the Ocular Surface. Mucosal Immunol 2022, 15, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dua, H.S.; Donoso, L.A.; Laibson, P.R. Conjunctival Instillation of Retinal Antigens Induces Tolerance Does It Invoke Mucosal Tolerance Mediated via Conjunctiva Associated Lymphoid Tissues (CALT)? Ocul Immunol Inflamm 1994, 2, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galletti, J.G.; Guzmán, M.; Giordano, M.N. Mucosal Immune Tolerance at the Ocular Surface in Health and Disease. Immunology 2017, 150, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulsham, W.; Marmalidou, A.; Amouzegar, A.; Coco, G.; Chen, Y.; Dana, R. The Function of Regulatory T Cells at the Ocular Surface: Review. Ocul Surf 2017, 15, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, J. V.; McMenamin, P.G. Evolution of the Ocular Immune System. Eye 2024, 39, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irmina, J.M.; Bartosz, M.; Dorota, W.P.; Adrian, S. The Role of Substance P in Corneal Homeostasis. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, J.P.; Nichols, K.K.; Akpek, E.K.; Caffery, B.; Dua, H.S.; Joo, C.K.; Liu, Z.; Nelson, J.D.; Nichols, J.J.; Tsubota, K.; et al. TFOS DEWS II Definition and Classification Report. Ocular Surface 2017, 15, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemp, M.A.; Baudouin, C.; Baum, J.; Dogru, M.; Foulks, G.N.; Kinoshita, S.; Laibson, P.; McCulley, J.; Murube, J.; Pflugfelder, S.C.; et al. The Definition and Classification of Dry Eye Disease: Report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007). Ocular Surface 2007, 5, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Report of the National Eye Institute/Industry Workshop on Clinical Trials in Dry Eyes - PubMed Available online:. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8565190/ (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Baudouin, C.; Messmer, E.M.; Aragona, P.; Geerling, G.; Akova, Y.A.; Benítez-Del-Castillo, J.; Boboridis, K.G.; Merayo-Lloves, J.; Rolando, M.; Labetoulle, M. Revisiting the Vicious Circle of Dry Eye Disease: A Focus on the Pathophysiology of Meibomian Gland Dysfunction. British Journal of Ophthalmology 2016, 100, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pflugfelder, S.C.; de Paiva, C.S. The Pathophysiology of Dry Eye Disease: What We Know and Future Directions for Research. Ophthalmology 2017, 124, S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolaños-Jiménez, R.; Navas, A.; López-Lizárraga, E.P.; Ribot, F.M. de; Peña, A.; Graue-Hernández, E.O.; Garfias, Y. Ocular Surface as Barrier of Innate Immunity. Open Ophthalmol J 2015, 9, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, J.L.; Vannan, D.T.; Eksteen, B.; Avelar, I.J.; Rodríguez, T.; González, M.I.; Mendoza, A.V. Innate and Adaptive Cell Populations Driving Inflammation in Dry Eye Disease. Mediators Inflamm 2018, 2018, 2532314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, L.; Li, D.Q.; Doshi, A.; Farley, W.; Corrales, R.M.; Pflugfelder, S.C. Experimental Dry Eye Stimulates Production of Inflammatory Cytokines and MMP-9 and Activates MAPK Signaling Pathways on the Ocular Surface. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2004, 45, 4293–4301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.Q.; Luo, L.; Chen, Z.; Kim, H.S.; Song, X.J.; Pflugfelder, S.C. JNK and ERK MAP Kinases Mediate Induction of IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-8 Following Hyperosmolar Stress in Human Limbal Epithelial Cells. Exp Eye Res 2006, 82, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Dana, R. Autoimmunity in Dry Eye Disease – an Updated Review of Evidence on Effector and Memory Th17 Cells in Disease Pathogenicity. Autoimmun Rev 2021, 20, 102933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustardas, P.; Aberdam, D.; Lagali, N. MAPK Pathways in Ocular Pathophysiology: Potential Therapeutic Drugs and Challenges. Cells 2023, 12, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Lu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jin, Q.; Shentu, X.; Ye, J.; Ji, J.; Yao, K.; Han, H. Anti-Oxidative and Anti-Inflammatory Micelles: Break the Dry Eye Vicious Cycle. Advanced Science 2022, 9, 2200435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Paiva, C.S.; Corrales, R.M.; Villarreal, A.L.; Farley, W.J.; Li, D.Q.; Stern, M.E.; Pflugfelder, S.C. Corticosteroid and Doxycycline Suppress MMP-9 and Inflammatory Cytokine Expression, MAPK Activation in the Corneal Epithelium in Experimental Dry Eye. Exp Eye Res 2006, 83, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.Q.; Lokeshwar, B.L.; Solomon, A.; Monroy, D.; Ji, Z.; Pflugfelder, S.C. Regulation of MMP-9 Production by Human Corneal Epithelial Cells. Exp Eye Res 2001, 73, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.H.; Chen, W.Y.; Huang, Y.H.; Hsu, S.M.; Tsao, Y.P.; Hsu, Y.H.; Chang, M.S. Interleukin-20 Is Involved in Dry Eye Disease and Is a Potential Therapeutic Target. J Biomed Sci 2022, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Chen, B. Characterization of T Cells in the Progression of Dry Eye Disease Using Single-Cell RNA Sequencing in Mice. Eur J Med Res 2025, 30, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redfern, R.L.; Barabino, S.; Baxter, J.; Lema, C.; McDermott, A.M. Dry Eye Modulates the Expression of Toll-Like Receptors on the Ocular Surface. Exp Eye Res 2015, 134, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alven, A.; Lema, C.; Redfern, R.L. Impact of Low Humidity on Damage Associated Molecular Patterns at the Ocular Surface during Dry Eye Disease. Optom Vis Sci 2021, 98, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tibrewal, S.; Ivanir, Y.; Sarkar, J.; Nayeb-Hashemi, N.; Bouchard, C.S.; Kim, E.; Jain, S. Hyperosmolar Stress Induces Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Formation: Implications for Dry Eye Disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2014, 55, 7961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonawane, S.; Khanolkar, V.; Namavari, A.; Chaudhary, S.; Gandhi, S.; Tibrewal, S.; Jassim, S.H.; Shaheen, B.; Hallak, J.; Horner, J.H.; et al. Ocular Surface Extracellular DNA and Nuclease Activity Imbalance: A New Paradigm for Inflammation in Dry Eye Disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012, 53, 8253–8263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.; Surenkhuu, B.; Raju, I.; Atassi, N.; Mun, J.; Chen, Y.F.; Sarwar, M.A.; Rosenblatt, M.; Pradeep, A.; An, S.; et al. Pathological Consequences of Anti-Citrullinated Protein Antibodies in Tear Fluid and Therapeutic Potential of Pooled Human Immune Globulin-Eye Drops in Dry Eye Disease. Ocular Surface 2020, 18, 80–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yingming, W.; Jing, G.; Tianhong, W.; Zhenyu, W. M2 Macrophages Mitigate Ocular Surface Inflammation and Promote Recovery in a Mouse Model of Dry Eye. Exp Eye Res 2025, 110439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, J.; Yaman, E.; Silva, G.C.V.; Chen, R.; de Paiva, C.S.; Stepp, M.A.; Pflugfelder, S.C. Single Cell Analysis of Short-Term Dry Eye Induced Changes in Cornea Immune Cell Populations. Front Med (Lausanne) 2024, 11, 1362336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, J.; Yaman, E.; de Paiva, C.S.; Li, D.Q.; Villalba Silva, G.C.; Zuo, Z.; Pflugfelder, S.C. Changes in Conjunctival Mononuclear Phagocytes and Suppressive Activity of Regulatory Macrophages in Desiccation Induced Dry Eye. Ocular Surface 2024, 34, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chauhan, S.K.; Saban, D.R.; Sadrai, Z.; Okanobo, A.; Dana, R. Interferon-γ-Secreting NK Cells Promote Induction of Dry Eye Disease. J Leukoc Biol 2011, 89, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Volpe, E.A.; Gandhi, N.B.; Schaumburg, C.S.; Siemasko, K.F.; Pangelinan, S.B.; Kelly, S.D.; Hayday, A.C.; Li, D.Q.; Stern, M.E.; et al. NK Cells Promote Th-17 Mediated Corneal Barrier Disruption in Dry Eye. PLoS One 2012, 7, e36822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Lee, S.M.; Lee, H.; Amouzegar, A.; Nakao, T.; Chen, Y.; Dana, R. Neurokinin-1 Receptor Antagonism Ameliorates Dry Eye Disease by Inhibiting Antigen-Presenting Cell Maturation and T Helper 17 Cell Activation. American Journal of Pathology 2020, 190, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Li, W.; Cheng, H.; Zhong, L.; Deng, J.; Ling, S. The Important Role of the Chemokine Axis CCR7-CCL19 and CCR7-CCL21 in the Pathophysiology of the Immuno-Inflammatory Response in Dry Eye Disease. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2021, 29, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodati, S.; Chauhan, S.K.; Chen, Y.; Dohlman, T.H.; Karimian, P.; Saban, D.; Dana, R. CCR7 Is Critical for the Induction and Maintenance of Th17 Immunity in Dry Eye Disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2014, 55, 5871–5877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrah, P.; Huq, S.O.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Dana, M.R. Corneal Immunity Is Mediated by Heterogeneous Population of Antigen-Presenting Cells. J Leukoc Biol 2003, 74, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Amouzegar, A.; Dana, R. Kinetics of Corneal Antigen Presenting Cells in Experimental Dry Eye Disease. BMJ Open Ophthalmol 2017, 1, e000078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chauhan, S.K.; Soo Lee, H.; Saban, D.R.; Dana, R. Chronic Dry Eye Disease Is Principally Mediated by Effector Memory Th17 Cells. Mucosal Immunology 2014 7:1 2013, 7, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annan, J. El; Chauhan, S.K.; Ecoiffier, T.; Zhang, Q.; Saban, D.R.; Dana, R. Characterization of Effector T Cells in Dry Eye Disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2009, 50, 3802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pflugfelder, S.C.; Corrales, R.M.; de Paiva, C.S. T Helper Cytokines in Dry Eye Disease. Exp Eye Res 2013, 117, 10.1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.C.; Zeng, W.; Wong, C.Y.; Mifsud, E.J.; Williamson, N.A.; Ang, C.S.; Vingrys, A.J.; Downie, L.E. Tear Interferon-Gamma as a Biomarker for Evaporative Dry Eye Disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2016, 57, 4824–4830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, B.Y.; Xiao, Y.; Barbosa, F.L.; de Paiva, C.S.; Pflugfelder, S.C. Goblet Cell Loss Abrogates Ocular Surface Immune Tolerance. JCI Insight 2018, 3, e98222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, K.H.G. Induction, Function and Regulation of IL-17-Producing T Cells. Eur J Immunol 2008, 38, 2636–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, L.; Wang, C.; Zhou, H. Inflammation Mechanism and Anti-Inflammatory Therapy of Dry Eye. Front Med (Lausanne) 2024, 11, 1307682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; de Paiva, C.S.; Li, D.Q.; Farley, W.J.; Pflugfelder, S.C. Desiccating Stress Promotion of Th17 Differentiation by Ocular Surface Tissues through a Dendritic Cell-Mediated Pathway. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2010, 51, 3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohlman, T.H.; Chauhan, S.K.; Kodati, S.; Hua, J.; Chen, Y.; Omoto, M.; Sadrai, Z.; Dana, R. The CCR6/CCL20 Axis Mediates Th17 Cell Migration to the Ocular Surface in Dry Eye Disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013, 54, 4081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Sun, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, T.; Wang, K.; Ren, T.; Wu, Z.; Xu, H.; Zhu, L. Analysis of Th17-Associated Cytokines in Tears of Patients with Dry Eye Syndrome. Eye (Basingstoke) 2014, 28, 608–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.; Chen, Y.; Inomata, T.; Liu, R.; Dana, R. Potential Role of IL-10-Producing Th17 Cells in Pathogenesis of Dry Eye Disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2017, 58, 1022–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Chauhan, S.K.; Shao, C.; Omoto, M.; Inomata, T.; Dana, R. Interferon-γ-Expressing Th17 Cells Are Required for Development of Severe Ocular Surface Autoimmunity. J Immunol 2017, 199, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dohlman, T.H.; Ding, J.; Dana, R.; Chauhan, S.K. T Cell–Derived Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor Contributes to Dry Eye Disease Pathogenesis by Promoting CD11b+ Myeloid Cell Maturation and Migration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2017, 58, 1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Gong, J.; Yang, Q.; Wang, L.; Jian, Y.; Wang, P. Interleukin-17 Receptor E and C-C Motif Chemokine Receptor 10 Identify Heterogeneous T Helper 17 Subsets in a Mouse Dry Eye Disease Model. American Journal of Pathology 2022, 192, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, J.; Yazdanpanah, G.; Ratnapriya, R.; Borcherding, N.; de Paiva, C.S.; Li, D.Q.; Guimaraes de Souza, R.; Yu, Z.; Pflugfelder, S.C. IL-17 Producing Lymphocytes Cause Dry Eye and Corneal Disease With Aging in RXRα Mutant Mouse. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022, 9, 849990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chauhan, S.K.; Soo Lee, H.; Saban, D.R.; Dana, R. Chronic Dry Eye Disease Is Principally Mediated by Effector Memory Th17 Cells. Mucosal Immunol 2013, 7, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chauhan, S.K.; Tan, X.; Dana, R. Interleukin-7 and -15 Maintain Pathogenic Memory Th17 Cells in Autoimmunity. J Autoimmun 2016, 77, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shao, C.; Fan, N.W.; Nakao, T.; Amouzegar, A.; Chauhan, S.K.; Dana, R. The Functions of IL-23 and IL-2 on Driving Autoimmune Effector T-Helper 17 Cells into the Memory Pool in Dry Eye Disease. Mucosal Immunol 2020, 14, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulsham, W.; Mittal, S.K.; Taketani, Y.; Chen, Y.; Nakao, T.; Chauhan, S.K.; Dana, R. Aged Mice Exhibit Severe Exacerbations of Dry Eye Disease with an Amplified Memory Th17 Cell Response. Am J Pathol 2020, 190, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shevach, E.M.; Thornton, A.M. TTregs, PTregs, and ITregs: Similarities and Differences. Immunol Rev 2014, 259, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi, S.; Ono, M.; Setoguchi, R.; Yagi, H.; Hori, S.; Fehervari, Z.; Shimizu, J.; Takahashi, T.; Nomura, T. Foxp3+CD25+CD4+ Natural Regulatory T Cells in Dominant Self-Tolerance and Autoimmune Disease. Immunol Rev 2006, 212, 8–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niederkorn, J.Y.; Stern, M.E.; Pflugfelder, S.C.; Cintia, ‡; De Paiva, S.; Corrales, R.M.; Gao, J.; Siemasko, K. Desiccating Stress Induces T Cell-Mediated Sjögren’s Syndrome-Like Lacrimal Keratoconjunctivitis. The Journal of Immunology 2006, 176, 3950–3957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siemasko, K.F.; Gao, J.; Calder, V.L.; Hanna, R.; Calonge, M.; Pflugfelder, S.C.; Niederkorn, J.Y.; Stern, M.E. In Vitro Expanded CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Regulatory T Cells Maintain a Normal Phenotype and Suppress Immune-Mediated Ocular Surface Inflammation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2008, 49, 5434–5440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, S.K.; El Annan, J.; Ecoiffier, T.; Goyal, S.; Zhang, Q.; Saban, D.R.; Dana, R. Autoimmunity in Dry Eye Is Due to Resistance of Th17 to Treg Suppression. J Immunol 2009, 182, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, N.W.; Dohlman, T.H.; Foulsham, W.; McSoley, M.; Singh, R.B.; Chen, Y.; Dana, R. The Role of Th17 Immunity in Chronic Ocular Surface Disorders. Ocul Surf 2020, 19, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuklinski, E.J.; Yu, Y.; Ying, G.S.; Asbell, P.A. Association of Ocular Surface Immune Cells With Dry Eye Signs and Symptoms in the Dry Eye Assessment and Management (DREAM) Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2023, 64, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-H.; Li, W.; McDermott, M.; Son, G.-Y.; Maiti, G.; Zhou, F.; Tao, A.Y.; Raphael, D.; Moreira, A.L.; Shen, B.; et al. IFN-γ-Producing Th1 Cells and Dysfunctional Regulatory T Cells Contribute to the Pathogenesis of Sjögren’s Disease. Sci Transl Med 2024, 16, eado4856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, R.G.; de Paiva, C.S.; Alves, M.R. Age-Related Autoimmune Changes in Lacrimal Glands. Immune Netw 2019, 19, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coursey, T.G.; Bian, F.; Zaheer, M.; Pflugfelder, S.C.; Volpe, E.A.; De Paiva, C.S. Age-Related Spontaneous Lacrimal Keratoconjunctivitis Is Accompanied by Dysfunctional T Regulatory Cells. Mucosal Immunol 2016, 10, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.; Li, Z. Multidimensional Immunotherapy for Dry Eye Disease: Current Status and Future Directions. Frontiers in Ophthalmology 2024, 4, 1449283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, H.; Yang, H.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S. Substance P and Neurokinin 1 Receptor Boost the Pathogenicity of Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor-Producing T Helper Cells in Dry Eye Disease. Scand J Immunol 2025, 101, e13434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Im, S.T.; Wu, J.; Cho, C.S.; Jo, D.H.; Chen, Y.; Dana, R.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, S.M. Corneal Lymphangiogenesis in Dry Eye Disease Is Regulated by Substance P/Neurokinin-1 Receptor System through Controlling Expression of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 3. Ocul Surf 2021, 22, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.B.; Naderi, A.; Cho, W.; Ortiz, G.; Musayeva, A.; Dohlman, T.H.; Chen, Y.; Ferrari, G.; Dana, R. Modulating the Tachykinin: Role of Substance P and Neurokinin Receptor Expression in Ocular Surface Disorders. Ocul Surf 2022, 25, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taketani, Y.; Marmalidou, A.; Dohlman, T.H.; Singh, R.B.; Amouzegar, A.; Chauhan, S.K.; Chen, Y.; Dana, R. Restoration of Regulatory T-Cell Function in Dry Eye Disease by Antagonizing Substance P/Neurokinin-1 Receptor. Am J Pathol 2020, 190, 1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Naderi, A.; Kahale, F.; Ortiz, G.; Forouzanfar, K.; Chen, Y.; Dana, R. Substance P Regulates Memory Th17 Cell Generation and Maintenance in Chronic Dry Eye Disease. J Leukoc Biol 2024, 116, 1446–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, X.; Ye, H.; Yang, K.; Zhou, X.; Hong, J. Tear Neuropeptides Are Associated with Clinical Symptoms and Signs of Dry Eye Patients. Ann Med 2025, 57, 2451194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, H.-J.; Jang, W.-H.; An, S.; Ji, Y.S.; Yoon, K.C. Tear Neuromediators in Subjects with and without Dry Eye According to Ocular Sensitivity. Chonnam Med J 2022, 58, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, X.; Ye, H.; Yang, K.; Zhou, X.; Hong, J. Tear Neuropeptides Are Associated with Clinical Symptoms and Signs of Dry Eye Patients. Ann Med 2025, 57, 2451194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambiase, A.; Micera, A.; Sacchetti, M.; Cortes, M.; Mantelli, F.; Bonini, S. Alterations of Tear Neuromediators in Dry Eye Disease. Archives of Ophthalmology 2011, 129, 981–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Vázquez, M.; Vázquez, A.; Fernández, I.; Novo-Diez, A.; Martínez-Plaza, E.; García-Vázquez, C.; González-García, M.J.; Sobas, E.M.; Calonge, M.; Enríquez-de-Salamanca, A. Inflammation-Related Molecules in Tears of Patients with Chronic Ocular Pain and Dry Eye Disease. Exp Eye Res 2022, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzmán, M.; Miglio, M.; Keitelman, I.; Shiromizu, C.M.; Sabbione, F.; Fuentes, F.; Trevani, A.S.; Giordano, M.N.; Galletti, J.G. Transient Tear Hyperosmolarity Disrupts the Neuroimmune Homeostasis of the Ocular Surface and Facilitates Dry Eye Onset. Immunology 2020, 161, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuoka, T.; Yamashita, Y.; Nakano, K.; Takechi, K.; Niimura, T.; Tawa, M.; He, Q.; Ishizawa, K.; Ishibashi, T. Chronic Tear Deficiency Sensitizes Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1-Mediated Responses in Corneal Sensory Nerves. Front Cell Neurosci 2020, 14, 598678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, J.; Shen Lee, B.; Periman, L.M. Dry Eye Disease: Identification and Therapeutic Strategies for Primary Care Clinicians and Clinical Specialists. Ann Med 2022, 55, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.; Downie, L.E.; Korb, D.; Benitez-del-Castillo, J.M.; Dana, R.; Deng, S.X.; Dong, P.N.; Geerling, G.; Hida, R.Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. TFOS DEWS II Management and Therapy Report. Ocul Surf 2017, 15, 575–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Gao, Q.; Liu, J.; Wu, Y.; Hou, X.; Sun, L.; Zhang, X.; Lu, Y.; Yang, Y. M2 Macrophage-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Ameliorate Benzalkonium Chloride-Induced Dry Eye. Exp Eye Res 2024, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chu, B.; Yang, K.; Hong, J.; He, Y. Targeting A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor for Modulating the Neuroinflammation of Dry Eye Disease Via Macrophages. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2025, 66, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, R.; Zhang, K.; Yang, T.; Hu, C.; Gao, Y.; Lan, Q.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; et al. Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor (PEDF) Plays Anti-Inflammatory Roles in the Pathogenesis of Dry Eye Disease. Ocular Surface 2021, 20, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, J.; Ding, X.; Song, Y.; Mi, B.; Fang, X.; Chen, B.; Yao, B.; Sun, X.; Yuan, X.; Guo, S.; et al. ROS-Responsive Microneedle Patches Enable Peri-Lacrimal Gland Therapeutic Administration for Long-Acting Therapy of Sjögren’s Syndrome-Related Dry Eye. Advanced Science 2025, 12, 2409562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadrai, Z.; Stevenson, W.; Okanobo, A.; Chen, Y.; Dohlman, T.H.; Hua, J.; Amparo, F.; Chauhan, S.K.; Dana, R. PDE4 Inhibition Suppresses IL-17–Associated Immunity in Dry Eye Disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012, 53, 3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosskreutz, C.L.; Hockey, H.U.; Serra, D.; Dryja, T.P. Dry Eye Signs and Symptoms Persist during Systemic Neutralization of IL-1b by Canakinumab or IL-17A by Secukinumab. Cornea 2015, 34, 1551–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Study Details | A Study to Evaluate the Safety, Tolerability, and Efficacy of A197 in Subjects With Dry Eye Disease | ClinicalTrials. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05238597 (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Ratay, M.L.; Glowacki, A.J.; Balmert, S.C.; Acharya, A.P.; Polat, J.; Andrews, L.P.; Fedorchak, M. V.; Schuman, J.S.; Vignali, D.A.A.; Little, S.R. Treg-Recruiting Microspheres Prevent Inflammation in a Murine Model of Dry Eye Disease. J Control Release 2017, 258, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Zou, Y.; Li, H.; Li, D.; Liu, Y.; Gong, B.; Yu, M. NK1R Antagonist, CP-99,994 Ameliorates Dry Eye Disease via Inhibiting the Plk1-Cdc25c-Cdk1 Axis. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 2025, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surico, P.L.; Barone, V.; Singh, R.B.; Coassin, M.; Blanco, T.; Dohlman, T.H.; Basu, S.; Chauhan, S.K.; Dana, R.; Zazzo, A. Di Potential Applications of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Ocular Surface Immune-Mediated Disorders. Surv Ophthalmol 2025, 70, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joung Lee, M.; Young Ko, A.; Hwa Ko, J.; Ju Lee, H.; Kum Kim, M.; Ryang Wee, W.; In Khwarg, S.; Youn Oh, J. Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells Protect the Ocular Surface by Suppressing Inflammation in an Experimental Dry Eye. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Aluri, H.S.; Samizadeh, M.; Edman, M.C.; Hawley, D.R.; Armaos, H.L.; Janga, S.R.; Meng, Z.; Sendra, V.G.; Hamrah, P.; Kublin, C.L.; et al. Delivery of Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Improves Tear Production in a Mouse Model of Sjögren’s Syndrome. Stem Cells Int 2017, 2017, 3134543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Chen, Q.; Wei, Z.; Xu, X.; Han, D.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Liang, Q. MicroRNAs of Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Alleviate Inflammation in Dry Eye Disease by Targeting the IRAK1/TAB2/NF-ΚB Pathway. Ocul Surf 2023, 28, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, H.; Long, H.; Gong, X.; Hu, S.; Gong, C. Exosomes Derived from Mouse Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Alleviate Benzalkonium Chloride-Induced Mouse Dry Eye Model via Inhibiting NLRP3 Inflammasome. Ophthalmic Res 2022, 65, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Gu, C.; Yang, Y.; He, T.; Zhang, Q. Exosomal MiR-146a Derived from Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells Alleviates Inflammation and Apoptosis in Dry Eye Disease by Targeting SQSTM1. Exp Eye Res 2025, 110490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Biomarker | Response in DED | Role | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACPA | ↑ | Generated during neutrophil NETosis, induces OS inflammation in murine models | [36] |

| ADAM17 | ↑ | Contributes to ocular pain and epithelial barrier disruption | [38] |

| CCL2 | ↑ | Drives basal epithelial cells in acting as ‘non-professional APCs’ in further activating immune response | [31] |

| CCL20 | ↑ | Aids migration of Th17 cells back to OS, specifically the conjunctiva | [55] |

| CCL5 | ↑ | Promotes T cell recruitment | [6,13] |

| CCR5 | ↑ | Facilitates Th1 targeted migration from lymph nodes back to inflamed OS | [48] |

| CCR6 | ↑ | Aids migration of Th17 cells back to OS, specifically the conjunctiva | [55] |

| CGRP | ↑ and ↓ | Exhibits both an immunosuppressive and proinflammatory role depending on the microenvironment; Inhibits APCs through suppression of mast cell-derived TNF; Upregulated in response to inflammatory stimulation or nerve sensitization. | [76,82,83,86] |

| CTLA-4 | ↑ | Impairs suppressive capacity against effector T cells | [79,80] |

| CXCL1 | ↑ | Activates TRPV1 and ADAM17 which contributes to ocular pain and epithelial barrier disruption | [38] |

| CXCL10 | ↑ | Recruits Th1 cells to the OS through CXCR3 signaling, amplifying local inflammation | [6,13] |

| CXCL9 | ↑ | Activates T cells and sustains chronic inflammatory responses via CXCR3 | [6,13] |

| CXCR3 | ↑ | Facilitates migration of DED-primed Th1 cells from lymph nodes back to inflamed OS | [48] |

| GM-CSF | ↑ | Stimulates monocytic cells to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-23 with IL-6 and IL-23 further perpetuating Th17 differentiation | [59] |

| HMGB1 | ↑ | Activates TLR pathways and induces proinflammatory cytokine and MMP-9 release | [33] |

| HSP-60 | ↑ | Activates TLR pathways, leading to cytokine release and immune cell recruitment | [33] |

|

IFN-γ |

↑ in early DED ↓ in later disease progression |

Induces epithelial damage and disrupts homeostasis of OS NK activation promotes IFN- γ-mediated inflammation and drives APC maturation which primes adaptive immune response; Induces GC loss and reduces mucin production |

[40,47,50] |

| IL-1 | ↑ | Allows Th17 cells to undergo further differentiation at the conjunctiva. | [55] |

| IL-10 | ↓ | Exacerbates goblet cell loss and Th17 mediated pathology contribute to impaired suppressive capacity against effector T cells. | [39,79,80] |

| IL-12 | ↑ | Leads to further Th1 polarization | [51] |

| IL-15 | ↑ | Maintains Th17 memory cells and promotes continued survival | [63] |

| IL-17 | ↑ | Disrupts corneal epithelium barrier integrity, stimulates MMP production and promotes inflammation and apoptosis, | [49,56] |

| IL-17C | ↑ | Enhances JNK and p38 MAPK signaling though IL-17C/IL17RE interaction therefore reinforces and perpetuates Th17 phenotype | [60] |

| IL-1β | ↑ | Promotes epithelial damage, upregulates proinflammatory mediators, and enhances immune cell activation | [25,27,29] |

| IL-2 | - | Inhibits differentiation of Th17 effector cells into memory cells | [64] |

| IL-20 | ↑ | Promotes macrophage recruitment and increases inflammatory signaling in OS | [30] |

| IL-23 | ↑ | Allows Th17 cells to undergo further differentiation at the conjunctiva and promotes transition into memory cells | [6,13,41,55,64] |

| IL-6 | ↑ | Activates DCs and enhances Th17 responses; Initiates Th-17 cell differentiation via STAT3 signaling pathways; Exhibits inhibitory effect on Treg differentiation. | [6,13,41,52,53,71] |

| IL-7 | ↑ | Helps maintain Th17 memory cells and promotes continued survival | [63] |

| IL17A | ↑ | Promotes neutrophil recruitment, epithelial barrier disruption, and proinflammatory cytokine production at OS | [61,70] |

| IL17F | ↑ | Stimulates epithelial cells and immune cells to release inflammatory mediators and chemokines | [61] |

| MMP-9 | ↑ | Degrades epithelial basement membrane components and disrupts tight junction proteins | [25,27,29] |

| NF-κB | ↑ | Drives early upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines, promoting immune cell activation | [25,30] |

| NFAT5 | ↑ | Promotes early cytokine upregulation and immune cell activation | [25,30] |

| PD-1 | ↑ | Impairs suppressive capacity against effector T cells | [79,80] |

| RORγt | ↑ | Regulates and promotes Th-17 cell differentiation | [54] |

| RXRa | ↓ | Exacerbates goblet cell loss and Th17 mediated pathology. | [39] |

| TGF-β | ↑ | Induces Th17 cells and contributes to impaired suppressive capacity against effector T cells. | [6,13,79,80] |

| TLR4 | ITLR mRNA ↑ TLR protein levels ↓ |

Recognizes DAMPs (like HMGB1) and microbial products, activating NF-κB and driving cytokine/chemokine release | [21] |

| TLR9 | TLR9 mRNA ↓ TLR9 protein ↓ |

Impairs local immune regulatory function at OS | [32] |

| TNF-β | ↑ | Initiates Th-17 cell differentiation via STAT3 signaling pathways. | [52,53] |

| TNF-α | ↑ | upregulates proinflammatory cytokines, disrupting epithelial barrier integrity, and amplifying immune cell infiltration | [25,27,29] |

| TRPV1 | ↑ | Contributes to ocular pain and epithelial barrier disruption | [38] |

| VEGF, VEGF-D, VEGFR-3 | ↑ | Promotes lymphatic vessel growth and facilitates APC trafficking to draining lymph nodes. | [78] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).