Submitted:

29 August 2025

Posted:

01 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fungal Strains and Culture Conditions

2.2. Vev and Aev Preparation

2.3. EV Preparation from Vpb18 Under Sublethal Stress Conditions

2.4. Estimation of EV Size, Sterol and Peptide Content

2.5. Physicochemical Characterization of EVs

2.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.7. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

2.8. Sample Preparation for Proteomic Analysis

2.9. LC-MS/MS Analysis

2.10. Proteomic Data Processing

2.11. Protein Abundance Analysis, Functional Annotation, and PTM Profiling

3. Results

3.1. Vev and Aev Morphological and Physicochemical Aspects

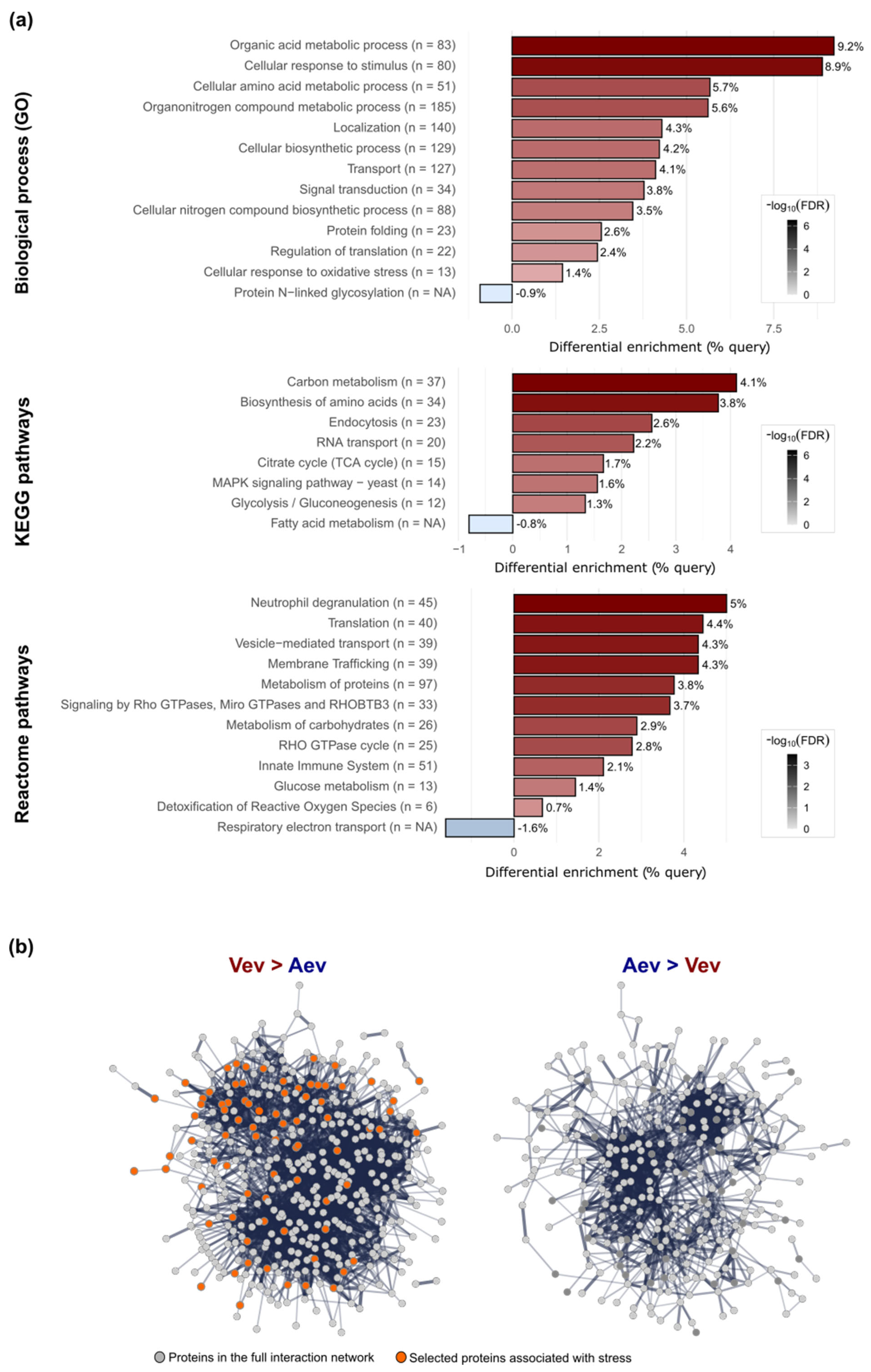

3.2. P. brasiliensis Vev and Aev Proteomes Differ in Cargo Profile

3.3. Protein Nt-Acetylation and Phosphorylation Vary with the Sample

3.4. Sublethal Stress Conditions Induce Altered Vev Proteome

| Protein accession no. |

Protein description | FC* VevOxi |

FC* VevNO | FC Vev/Aev | VirReg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrate metabolism | |||||

| C1G8R5 | 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, decarboxylating | 2.97 | 1.51 | 8.41 | |

| C1G0C5 | Carbonic anhydrase | 2.43 | 0.87 | 4.62 | Yes |

| C1G1C8 | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase | 2.25 | 2.75 | 1.82 | Yes |

| C1G0R1 | Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase | 2.51 | 1.14 | 7.29 | Yes |

| C1G5F6 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 5.31 | 3.12 | 1.97 | Yes |

| C1G8V5 | Glycosidase | 1.81 | 5.1 | Unique | Yes |

| A0A0A0HX82 | Phosphoglucomutase (alpha-D-glucose-1,6-bisphosphate-dependent) | 2.41 | 1.9 | 8.9 | |

| C1G4N0 | Phosphoglycerate kinase | 2.53 | 1.63 | 1.84 | Yes |

| C1GJI4 | Transaldolase | 1.72 | 0.84 | Unique | |

| C1GC82 | Transketolase | 3.81 | 2.85 | 3.08 | |

| Tricarboxylic acid (TCA) and glyoxylate cycles | |||||

| C1GLZ6 | Citrate synthase | 5.74 | 2 | Unique | |

| C1GLB8 | Malate dehydrogenase | 2.3 | 1.21 | 1.59 | |

| C1GCI0 | Malate synthase | 1.44 | 1.5 | 1.58 | Yes |

| Lipid and phospholipid metabolism | |||||

| C1G421 | Acetyl-CoA C-acyltransferase | 1.79 | 1.3 | 1.35 | |

| C1G2P3 | Enoyl-CoA hydratase | 5.58 | 2.1 | 4.55 | Yes |

| C1GHR9 | Short-chain 2-methylacyl-CoA dehydrogenase | 2.48 | 1.18 | 3.43 | |

| C1GKG2 | Very-long-chain 3-oxoacyl-CoA reductase | 2.13 | 1.57 | 1.31 | |

| Energy metabolism and biosynthesis | |||||

| C1GIX7 | Acetyltransferase component of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex | 2.77 | 2.01 | 1.49 | |

| C1G0P4 | AMP-dependent synthetase/ligase domain-containing protein | 2.28 | 3.07 | 2.03 | |

| C1G5X3 | ATP synthase subunit 4 | 1.95 | 1.13 | Unique | |

| C1GCK7 | ATP synthase subunit d, mitochondrial | 3.03 | 1.88 | 2.75 | |

| C1GN84 | FAD-binding FR-type domain-containing protein | 1.5 | 1.67 | 3.14 | |

| C1GKG3 | NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase, type IV | 3.63 | 3.81 | 1.61 | |

| C1GJT8 | Nucleoside diphosphate kinase | 1.47 | 1.67 | 1.86 | Yes |

| C1GML7 | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (ATP) | 1.67 | 1.59 | 1.88 | Yes |

| Amino acid and nucleotide metabolism | |||||

| C1GLT7 | 5-methyltetrahydropteroyltriglutamate--homocysteine S-methyltransferase | 4.92 | 5.43 | 1.91 | |

| C1G025 | Aromatic-L-amino-acid decarboxylase | 3.76 | 6.77 | Unique | |

| C1G388 | Aspartate aminotransferase | 4.63 | 4.35 | 1.7 | Yes |

| C1G9D5 | Urease | 1.84 | 1.14 | 2.38 | Yes |

| Transport and secretion | |||||

| C1GEX3 | ABC metal ion transporter | 2.22 | 1.52 | 2.19 | |

| C1G2Y7 | ABC transporter domain-containing protein | 2.69 | 2.89 | 2.92 | Yes |

| C1G8S5 | Amino acid permease/ SLC12A domain-containing protein | 1.53 | 1.64 | 4.56 | Yes |

| C1GA14 | Clathrin heavy chain | 0.84 | 1.74 | 1.93 | Yes |

| C1GBT3 | Copper transport protein | 2.43 | 2.39 | 4.54 | Yes |

| C1GK98 | Chromate ion transporter | 1.62 | 0.92 | 2.96 | |

| C1FZR3 | Leptomycin B resistance protein pmd1 | 1.83 | 2.39 | Unique | Yes |

| C1GL34 | Major facilitator superfamily (MFS) profile domain-containing protein | 1.7 | 2.08 | 4.98 | Yes |

| C1GJY9 | Major facilitator superfamily (MFS) profile domain-containing protein | 3.86 | 4.59 | 4.65 | Yes |

| C1G1D9 | Major facilitator superfamily (MFS) profile domain-containing protein | 2.13 | 2.22 | 2.12 | Yes |

| C1G7G9 | Major facilitator superfamily (MFS) profile domain-containing protein | 5.06 | 5.7 | 1.91 | Yes |

| C1GM00 | Plasma membrane ATPase | 1.35 | 1.75 | 1.86 | Yes |

| C1GGI0 | Zinc/iron transporter | 1.31 | 1.96 | 1.96 | Yes |

| C1G7B3 | YeeE/YedE family integral membrane protein | 4.35 | 3.97 | 2.03 | |

| Protein synthesis, processing and degradation | |||||

| C1G5J0 | 40S ribosomal protein S15 | 1.87 | 1.62 | 1.33 | |

| C1GGR5 | 40S ribosomal protein S20 | 3.34 | 4.29 | 1.69 | |

| C1G9U4 | 60S acidic ribosomal protein P0 | 1.87 | 1.52 | 2.16 | |

| C1GKL7 | 60S ribosomal protein L12 | 2.87 | 2.62 | Unique | |

| C1GC66 | 60S ribosomal protein L22 | 5.5 | 2.62 | 4.67 | |

| A0A0A0HVH2 | 60S ribosomal protein L31 | 1.13 | 1.75 | 1.42 | |

| A0A0A0HV09 | ATP-dependent RNA helicase eIF4A | 1.64 | 1.73 | 1.36 | |

| C1GIV4 | Proteasome subunit alpha type-2 | 2.2 | 1.17 | Unique | |

| C1G9A5 | Protein disulfide-isomerase | 1.34 | 1.5 | 5.38 | |

| Genetic information processing and regulation | |||||

| C1GF71 | Histone H2B | 2.57 | 2.03 | 1.31 | Yes |

| A0A0A0HU09 | K Homology domain-containing protein | 2.81 | 2.17 | 1.9 | |

| C1GEW2 | SsDNA binding protein | 2.27 | 3.81 | 2.97 | |

| Stress response and antioxidant defense | |||||

| C1GC65 | Glutathione peroxidase | 2.48 | 1.84 | 2.84 | Yes |

| C1GLX8 | Hsp60-like protein | 3.32 | 2.16 | 2.54 | Yes |

| C1GKC9 | Hsp90-like protein | 2.45 | 1.81 | 1.83 | Yes |

| C1G4T8 | Superoxide dismutase | 5.17 | 2.3 | Unique | Yes |

| C1G7E0 | Thioredoxin domain-containing protein | 2.17 | 1.06 | 7.96 | Yes |

| Cell wall biogenesis and remodeling | |||||

| C1GGK1 | Chitin synthase | 4.11 | 4.23 | 4.35 | Yes |

| C1GBY7 | GPI-anchored cell wall protein | 2.31 | 2.08 | Unique | Yes |

| Signal transduction and cellular communication | |||||

| C1G1C6 | CSC1/OSCA1-like 7TM region domain-containing protein | 1.11 | 1.36 | 4.27 | |

| C1GCT8 | GTP-binding nuclear protein | 1.55 | 1.36 | 1.45 | |

| C1GLU6 | GTP-binding protein rhoA | 1.46 | 1.46 | 1.4 | Yes |

| C1GE03 | Ras-like protein | 1.31 | 1.21 | 1.65 | Yes |

| C1GMU5 | t-SNARE coiled-coil homology domain-containing protein | 1.44 | 1.51 | 1.39 | |

| Uncharacterized / unknown function | |||||

| C1GKF2 | FAR-17a/AIG1-like protein | 7.89 | 8.06 | Unique | |

| C1GMY9 | DUF1774-domain-containing protein | 1.48 | 0.91 | Unique | |

| C1G9G6 | Uncharacterized protein | 1.09 | 2.23 | Unique | |

| *FC: Fold change in reference to the control condition. | |||||

3.5. Vev-Enriched Fungal Virulence Regulators Tend to be Nt-Acetylated and More Abundant upon Sublethal Stress

| Protein accession no. |

Protein description | FC* Vev/Aev | HAP** | Nt-Ac*** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VevOxi | VevNO | Vev | Aev | Vpb18 | |||

| Carbohydrate metabolism | |||||||

| C1G0C5 | Carbonic anhydrase | 4.62 | HAP | Nt-Ac | - | x | |

| C1G1C8 | Fructosexbisphosphate aldolase | 1.82 | HAP | HAP | Nt-Ac | Nt-Ac | Nt-Ac |

| C1G0R1 | Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase | 7.29 | HAP | - | - | Nt-Ac | |

| C1G0I9 | Glucosidase 2 subunit beta | 1.48 | - | - | - | ||

| C1GL11 | Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase [-D(+)] | Unique | x | x | - | x | x |

| C1G5F6 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 1.97 | HAP | HAP | Nt-Ac | Nt-Ac | Nt-Ac |

| C1G8V5 | Glycosidase | Unique | HAP | HAP | - | x | - |

| C1G801 | Glycosyltransferase family 62 protein | Unique | - | - | - | ||

| C1G4N0 | Phosphoglycerate kinase | 1.84 | HAP | HAP | Nt-Ac | Nt-Ac | Nt-Ac |

| C1GCX3 | Phosphoglycerate mutase (2 3-diphosphoglycerate-independent) | Unique | x | x | - | x | - |

| C1GI20 | Triosephosphate isomerase | 2.83 | - | - | Nt-Ac | ||

| Tricarboxylic acid (TCA) and glyoxylate cycles | |||||||

| C1GCI7 | Isocitrate lyase | 6.89 | x | x | - | - | - |

| C1GCI0 | Malate synthase | 1.58 | HAP | HAP | Nt-Ac | Nt-Ac | - |

| C1G294 | Succinate--CoA ligase [ADP-forming] subunit alpha mitochondrial | Unique | x | x | - | x | - |

| C1G0C7 | Succinate--CoA ligase [ADP-forming] subunit beta mitochondrial | 2.87 | x | x | - | - | Nt-Ac |

| Lipid and phospholipid metabolism | |||||||

| C1G2P3 | Enoyl-CoA hydratase | 4.55 | HAP | HAP | - | - | - |

| C1GFA5 | Phospholipase D | 6.14 | x | x | - | - | x |

| C1GA36 | Phospholipase D/nuclease | Unique | x | x | - | x | x |

| C1G7F7 | Lysophospholipase | Unique | x | x | - | x | x |

| Energy metabolism and biosynthesis | |||||||

| C1G5E8 | Acid phosphatase | 4.74 | - | - | x | ||

| C1GMH9 | Fumarylacetoacetase | Unique | x | x | - | x | Nt-Ac |

| C1GJT8 | Nucleoside diphosphate kinase | 1.86 | HAP | Nt-Ac | Nt-Ac | Nt-Ac | |

| C1GML7 | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (ATP) | 1.88 | HAP | HAP | Nt-Ac | - | Nt-Ac |

| C1GM00 | Plasma membrane ATPase | 1.86 | HAP | HAP | Nt-Ac | Nt-Ac | Nt-Ac |

| Amino acid and nucleotide metabolism | |||||||

| C1GD55 | 5-oxoprolinase | 26.74 | x | x | Nt-Ac | - | - |

| C1G388 | Aspartate aminotransferase | 1.7 | HAP | HAP | - | - | Nt-Ac |

| C1G3V5 | Aspartate aminotransferase | 2.31 | x | x | Nt-Ac | - | Nt-Ac |

| C1GJM4 | Aspartyl aminopeptidase | Unique | x | x | - | x | - |

| C1G022 | Hydantoinase | Unique | x | x | - | x | x |

| C1G4J8 | Kynurenine formamidase | Unique | x | x | - | x | - |

| C1G312 | Ornithine aminotransferase | Unique | x | x | - | x | - |

| C1G9D5 | Urease | 2.38 | HAP | - | - | - | |

| Transport and secretion | |||||||

| C1FZR3 | ABC multidrug transporter SidT | Unique | HAP | HAP | Nt-Ac | x | x |

| C1G2Y7 | ABC transporter domain-containing protein | 2.92 | HAP | HAP | - | - | x |

| C1G8S5 | Amino acid permease/ SLC12A domain-containing protein | 4.56 | HAP | HAP | Nt-Ac | - | x |

| C1GA14 | Clathrin heavy chain | 1.93 | HAP | Nt-Ac | - | - | |

| C1GBT3 | Copper transport protein | 4.54 | HAP | HAP | - | - | x |

| C1GL34 | Major facilitator superfamily (MFS) profile domain-containing protein | 4.98 | HAP | HAP | Nt-Ac | - | - |

| C1GJY9 | Major facilitator superfamily (MFS) profile domain-containing protein | 4.65 | HAP | HAP | Nt-Ac | - | x |

| C1G1D9 | Major facilitator superfamily (MFS) profile domain-containing protein | 2.12 | HAP | HAP | - | - | x |

| C1G7G9 | Major facilitator superfamily (MFS) profile domain-containing protein | 1.91 | HAP | HAP | - | - | x |

| C1GIS2 | Zinc/iron permease | Unique | x | x | - | x | x |

| C1GGI0 | Zinc/iron permease | 1.96 | HAP | HAP | Nt-Ac | - | - |

| Protein synthesis, processing and degradation | |||||||

| C1G4T3 | Elongation factor Tu | Unique | x | x | - | x | Nt-Ac |

| C1GJI6 | Peptidase S8/S53 domainxcontaining protein | 1.93 | x | x | - | - | x |

| C1G3B6 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase | Unique | x | x | - | x | x |

| C1GA06 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase | 15.4 | x | x | - | - | - |

| C1GD67 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase | Unique | x | x | - | x | - |

| C1GKU6 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase | 1.45 | x | x | - | - | - |

| C1GGQ1 | Peptidylprolyl isomerase | 1.68 | - | Nt-Ac | Nt-Ac | ||

| C1FYT6 | Zinc metalloproteinase | 14.88 | x | x | - | - | x |

| Genetic information processing and regulation | |||||||

| C1G092 | GTP-binding protein ypt2 | 3.93 | x | x | - | - | - |

| C1GF71 | Histone H2B | 1.31 | HAP | HAP | Nt-Ac | Nt-Ac | - |

| C1FYR1 | Rab family other | 2.66 | x | x | Nt-Ac | Nt-Ac | Nt-Ac |

| C1FZK1 | Ran GTPase-activating protein 1 | 1.52 | x | x | - | - | - |

| Stress response and antioxidant defense | |||||||

| C1G445 | Aha1_N domain-containing protein | 1.57 | x | x | - | - | - |

| C1G035 | Catalase | 3.53 | - | - | Nt-Ac | ||

| C1G2G2 | Glutaredoxin domain-containing protein | Unique | x | x | - | x | x |

| C1GC65 | Glutathione peroxidase | 2.84 | HAP | HAP | Nt-Ac | Nt-Ac | - |

| C1GAU3 | Heat shock protein STI1 | 2.77 | x | x | - | - | - |

| C1GLX8 | Hsp60-like protein | 2.54 | HAP | HAP | Nt-Ac | Nt-Ac | Nt-Ac |

| C1G0P0 | Hsp7-like protein | 1.74 | - | - | Nt-Ac | ||

| C1GLI2 | Hsp72-like protein | 2.13 | Nt-Ac | Nt-Ac | Nt-Ac | ||

| C1G6F6 | Hsp75-like protein | 2.6 | x | x | Nt-Ac | Nt-Ac | Nt-Ac |

| C1GKC9 | Hsp90-like protein | 1.83 | HAP | HAP | Nt-Ac | Nt-Ac | Nt-Ac |

| C1G1M5 | Hsp98-like protein | 1.44 | x | x | - | - | - |

| C1G532 | Nitroreductase domainxcontaining protein | 3.2 | x | x | - | - | x |

| C1GBB1 | Redoxin domain-containing protein | Unique | x | x | - | x | - |

| C1G9M7 | SHSP domain-containing protein | Unique | x | x | - | x | - |

| C1G4T8 | Superoxide dismutase | Unique | HAP | HAP | - | x | Nt-Ac |

| C1GJI2 | Superoxide dismutase [Cu-Zn] | 1.7 | x | x | - | - | - |

| C1GE86 | Survival factor 1 | 1.46 | x | x | - | - | - |

| C1GKT9 | Thioredoxin domain-containing protein | Unique | x | x | - | x | - |

| C1G6F9 | Thioredoxin-like fold domain-containing protein | 12.26 | Nt-Ac | Nt-Ac | - | ||

| C1GDK8 | Thioredoxin domain-containing protein | 8.44 | x | x | - | - | - |

| C1G7E0 | Thioredoxin domain-containing protein | 7.96 | HAP | Nt-Ac | - | Nt-Ac | |

| Cell wall biogenesis and remodeling | |||||||

| C1GGK1 | Chitin synthase | 4.35 | HAP | HAP | Nt-Ac | - | x |

| C1GKQ4 | Chitin synthase | 1.9 | - | - | - | ||

| A0A0A0HU35 | Chitin synthase C | Unique | x | x | - | x | x |

| C1GBY7 | GPI-anchored cell wall protein | Unique | HAP | HAP | - | x | x |

| Cellular organization | |||||||

| C1FZC6 | Actin cytoskeleton-regulatory complex protein PAN1 | 4.21 | x | x | - | - | x |

| C1GII4 | Septin-type G domain-containing protein | 1.63 | Nt-Ac | Nt-Ac | Nt-Ac | ||

| Signal transduction and cellular communication | |||||||

| C1GBU2 | CK1/CK1/CK1-G protein kinase | 2.02 | x | x | Nt-Ac | Nt-Ac | x |

| C1GFK5 | GTPxbinding protein rho3 | Unique | x | x | - | x | x |

| C1GLU6 | GTPxbinding protein rhoA | 1.4 | HAP | HAP | Nt-Ac | Nt-Ac | Nt-Ac |

| C1GJ63 | High osmolarity signaling protein SHO1 | Unique | x | x | - | x | x |

| C1GET1 | Non-specific serine/threonine protein kinase | 5.6 | x | x | - | - | - |

| C1G6S5 | Non-specific serine/threonine protein kinase | 3.66 | x | x | - | - | - |

| C1FYN4 | Non-specific serine/threonine protein kinase | 2.38 | x | x | Nt-Ac | - | - |

| C1GBG9 | Non-specific serine/threonine protein kinase | 2.19 | x | x | - | - | - |

| C1GM91 | Ras-GAP domainxcontaining protein | 3.44 | x | x | - | - | - |

| C1GE03 | Ras-like protein | 1.65 | HAP | - | - | - | |

| C1GEC2 | Ras-like protein Rab7 | Unique | x | x | - | x | - |

| * FC: Fold change. | |||||||

| ** "x" indicates that the protein was not detcted or validated. | |||||||

| *** "-" indicates that Nt-Ac modification was not detected. | |||||||

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Aev | Extracellular vesicles isolated from the Pb18 attenuated variant |

| Apb18 | Paracoccidioides brasiliensis Pb18 attenuated variant |

| CFU | Colony forming units |

| DLS | Dynamic Light Scattering |

| EVs | Extracellular vesicles |

| FDR | false discovery rate |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| HAP | High-abundance proteins |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| Nt-Ac | Protein Nt-acetylation |

| NTA | Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PCM | Paracoccidioidomycosis |

| PdI | olydispersity index |

| PdI | polydispersity index |

| Pho | Phosphorylation |

| PTMs | Post-translational modifications |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| SERS | Surface-enhanced Raman scattering |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| Vev | Extracellular vesicles isolated from the Pb18 virulent variant |

| VevNO | Vev derived from yeast cells cultivated under sublethal nitrosative stress |

| VevOxi | Vev derived from yeast cells cultivated under sublethal oxidative stress |

| Vpb18 | Paracoccidioides brasiliensis Pb18 virulent variant |

| ZP | zeta potential |

References

- Welsh, J.A.; Goberdhan, D.C.I.; O’Driscoll, L.; Buzas, E.I.; Blenkiron, C.; Bussolati, B.; Cai, H.; Di Vizio, D.; Driedonks, T.A.P.; Erdbrügger, U.; et al. Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles (MISEV2023): From Basic to Advanced Approaches. J Extracell Vesicles 2024, 13, 1–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, H.; Drummen, G.P.C.; Mathivanan, S. Focus on Extracellular Vesicles: Introducing the next Small Big Thing. Int J Mol Sci 2016, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, M.L.; Janbon, G.; O’Connell, R.J.; Chu, T.T.H.; May, R.C.; Jin, H.; Reis, F.C.G.; Alves, L.R.; Puccia, R.; Fill, T.P.; et al. Characterizing Extracellular Vesicles of Human Fungal Pathogens. Nat Microbiol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, Y.; Jiang, B.; Hou, F.; Huang, X.; Ling, B.; Lu, H.; Zhong, T.; Huang, J. The Emerging Role of Extracellular Vesicles in Fungi: A Double-Edged Sword. Front Microbiol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamith-Miranda, D.; Peres da Silva, R.; Couvillion, S.P.; Bredeweg, E.L.; Burnet, M.C.; Coelho, C.; Camacho, E.; Nimrichter, L.; Puccia, R.; Almeida, I.C.; et al. Omics Approaches for Understanding Biogenesis, Composition and Functions of Fungal Extracellular Vesicles. Front Genet 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, M.C.; Matsuo, A.L.; Ganiko, L.; Medeiros, L.C.S.; Miranda, K.; Silva, L.S.; Freymüller-Haapalainen, E.; Sinigaglia-Coimbra, R.; Almeida, I.C.; Puccia, R. The Pathogenic Fungus Paracoccidioides Brasiliensis Exports Extracellular Vesicles Containing Highly Immunogenic α-Galactosyl Epitopes. Eukaryot Cell 2011, 10, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, M.C.; Nakayasu, E.S.; Matsuo, A.L.; Sobreira, T.J.P.; Longo, L.V.G.; Ganiko, L.; Almeida, I.C.; Puccia, R. Vesicle and Vesicle-Free Extracellular Proteome of Paracoccidioides Brasiliensis: Comparative Analysis with Other Pathogenic Fungi. J Proteome Res. 2012 March 2; 11(3): 1676–1685. [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, M.C.; Nakayasu, E.S.; Longo, L.V.G.; Ganiko, L.; Lopes, F.G.; Matsuo, A.L.; Almeida, I.C.; Puccia, R. Lipidomic Analysis of Extracellular Vesicles from the Pathogenic Phase of Paracoccidioides Brasiliensis. PLoS One 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, L.V.G.; da Cunha, J.P.C.; Sobreira, T.J.P.; Puccia, R. Proteome of Cell Wall-Extracts from Pathogenic Paracoccidioides Brasiliensis: Comparison among Morphological Phases, Isolates, and Reported Fungal Extracellular Vesicle Proteins. EuPA Open Proteom 2014, 3, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, R.P.; Puccia, R.; Rodrigues, M.L.; Oliveira, D.L.; Joffe, L.S.; César, G. V.; Nimrichter, L.; Goldenberg, S.; Alves, L.R. Extracellular Vesicle-Mediated Export of Fungal RNA. Sci Rep 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, R.P.; Heiss, C.; Black, I.; Azadi, P.; Gerlach, J.Q.; Travassos, L.R.; Joshi, L.; Kilcoyne, M.; Puccia, R. Extracellular Vesicles from Paracoccidioides Pathogenic Species Transport Polysaccharide and Expose Ligands for DC-SIGN Receptors. Sci Rep 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres da Silva, R.; Longo, L.G. V.; Cunha, J.P.C. da; Sobreira, T.J.P.; Rodrigues, M.L.; Faoro, H.; Goldenberg, S.; Alves, L.R.; Puccia, R. Comparison of the RNA Content of Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Paracoccidioides Brasiliensis and Paracoccidioides Lutzii. Cells 2019, 8, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puccia, R. Current Status on Extracellular Vesicles from the Dimorphic Pathogenic Species of Paracoccidioides. In Fungal Extracellular Vesicles - Biological Roles; Rodrigues, M., Janbon, G., Eds.; Springer, 2021; Vol. 432, pp. 19–33. ISBN 978-3-030-83391-6.

- Martinez, R. New Trends in Paracoccidioidomycosis Epidemiology. J. Fungi 2017, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, A.M.; Hagen, F.; Puccia, R.; Hahn, R.C.; de Camargo, Z.P. Paracoccidioides and Paracoccidioidomycosis in the 21st Century. Mycopathologia 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, E. Paracoccidioidomycosis Protective Immunity J. Fungi 2021, 7, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-García, O.A.; Cuellar-Rodríguez, J.M. Immunology of Fungal Infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2021, 35, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, E.; Niño-Vega, G.A. Paracoccidioides Spp.: Virulence Factors and Immune-Evasion Strategies. Mediators Inflamm 2017. [CrossRef]

- Calich, V.L.; Singer-Vermes, L.M.; Siqueira, A.M.; Burger, E. Susceptibility and Resistance of Inbred Mice to Paracoccidioides Brasiliensis. Br J Exp Pathol 1985, 66, 585–594. [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva, T.A.; Roque-Barreira, M.C.; Casadevall, A.; Almeida, F. Extracellular Vesicles from Paracoccidioides Brasiliensis Induced M1 Polarization in Vitro. Sci Rep 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Octaviano, C.E.; Abrantes, N.E.; Puccia, R. Extracellular Vesicles From Paracoccidioides Brasiliensis Can Induce the Expression of Fungal Virulence Traits In Vitro and Enhance Infection in Mice. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baltazar, L.M.; Ribeiro, G.F.; Freitas, G.J.; Queiroz-Junior, C.M.; Fagundes, C.T.; Chaves-Olórtegui, C.; Teixeira, M.M.; Souza, D.G. Protective Response in Experimental Paracoccidioidomycosis Elicited by Extracellular Vesicles Containing Antigens of Paracoccidioides Brasiliensis. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanari Borges, B.; Gama de Santana, M.; Willian Preite, N.; de Lima Kaminski, V.; Trentin, G.; Almeida, F.; Vieira Loures, F. Extracellular Vesicles from Virulent P. Brasiliensis Induce TLR4 and Dectin-1 Expression in Innate Cells and Promote Enhanced Th1/Th17 Response. Virulence 2024, 15, 2329573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, A.F.A.; Navarro, M.V.; de Barros, Y.N.; Silva, R.S.; Xander, P.; Batista, W.L. Updates in Paracoccidioides Biology and Genetic Advances in Fungus Manipulation. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilho, D.G.; Chaves, A.F.A.; Xander, P.; Zelanis, A.; Kitano, E.S.; Serrano, S.M.T.; Tashima, A.K.; Batista, W.L. Exploring Potential Virulence Regulators in Paracoccidioides Brasiliensis Isolates of Varying Virulence through Quantitative Proteomics. J Proteome Res 2014, 13, 4259–4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilho, D.G.; Navarro, M. V; Chaves, A.F.A.; Xander, P.; Batista, W.L. Recovery of the Paracoccidioides Brasiliensis Virulence after Animal Passage Promotes Changes in the Antioxidant Repertoire of the Fungus. FEMS Yeast Res 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, F.C.G.; Borges, B.S.; Jozefowicz, L.J.; Sena, B.A.G.; Garcia, A.W.A.; Medeiros, L.C.; Martins, S.T.; Honorato, L.; Schrank, A.; Vainstein, M.H.; et al. A Novel Protocol for the Isolation of Fungal Extracellular Vesicles Reveals the Participation of a Putative Scramblase in Polysaccharide Export and Capsule Construction in Cryptococcus Gattii. mSphere 2019, 4, 80–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayat, M.Arif. Principles and Techniques of Electron Microscopy : Biological Applications; Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1978. ISBN 0442256701.

- Rodrigues, M.L.; Nakayasu, E.S.; Oliveira, D.L.; Nimrichter, L.; Nosanchuk, J.D.; Almeida, I.C.; Casadevall, A. Extracellular Vesicles Produced by Cryptococcus Neoformans Contain Protein Components Associated with Virulence. Eukaryot Cell 2008, 7, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, G.; Rocha, J.D.B.; Oliveira, D.L.; Albuquerque, P.C.; Frases, S.; Santos, S.S.; Nosanchuk, J.D.; Gomes, A.M.O.; Medeiros, L.C.A.S.; Miranda, K.; et al. Compositional and Immunobiological Analyses of Extracellular Vesicles Released by Candida Albicans. Cell Microbiol 2015, 17, 389–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, J.A.M.; Baltazar, L. de M.; Carregal, V.M.; Gouveia-Eufrasio, L.; de Oliveira, A.G.; Dias, W.G.; Rocha de Miranda, K.; Malavazi, I.; Santos, D. de A.; Frézard, F.J.G.; et al. Characterization of Aspergillus Fumigatus Extracellular Vesicles and Their Effects on Macrophages and Neutrophils Functions. Front Microbiol 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, N.M.K.; McCumber, A.W.; McMillan, H.M.; McNamara, R.P.; Dittmer, D.P.; Kuehn, M.J.; Hendren, C.O.; Wiesner, M.R. Comparative Electrokinetic Properties of Extracellular Vesicles Produced by Yeast and Bacteria. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2023, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stetefeld, J.; McKenna, S.A.; Patel, T.R. Dynamic Light Scattering: A Practical Guide and Applications in Biomedical Sciences. Biophys Rev 2016, 8, 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midekessa, G.; Godakumara, K.; Ord, J.; Viil, J.; Lättekivi, F.; Dissanayake, K.; Kopanchuk, S.; Rinken, A.; Andronowska, A.; Bhattacharjee, S.; et al. Zeta Potential of Extracellular Vesicles: Toward Understanding the Attributes That Determine Colloidal Stability. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 16701–16710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaddour, H.; Panzner, T.D.; Welch, J.L.; Shouman, N.; Mohan, M.; Stapleton, J.T.; Okeoma, C.M. Electrostatic Surface Properties of Blood and Semen Extracellular Vesicles: Implications of Sialylation and HIV-Induced Changes on EV Internalization. Viruses 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Retanal, C.; Ball, B.; Geddes-Mcalister, J. Post-Translational Modifications Drive Success and Failure of Fungal–Host Interactions. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McTiernan, N.; Kjosås, I.; Arnesen, T. Illuminating the Impact of N-Terminal Acetylation: From Protein to Physiology. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16:703. [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Chen, B.; Li, M.; Zhou, Y.; Ren, S.; Xu, Q.; Chen, M.; Wang, S. FPD: A Comprehensive Phosphorylation Database in Fungi. Fungal Biol 2017, 121, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksnes, H.; Hole, K.; Arnesen, T. Molecular, Cellular, and Physiological Significance of N-Terminal Acetylation. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol 2015, 316, 267–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dephoure, N.; Gould, K.L.; Gygi, S.P.; Kellogg, D.R. Mapping and Analysis of Phosphorylation Sites: A Quick Guide for Cell Biologists. Mol Biol Cell 2013, 24, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardozo, G.C.; Duarte, E.L.; da Cunha, A.R.; Soga, D.; de Almeida Rizzutto, M.; Lamy, M.T.; Milán-Garcés, E.A. Label-Free Detection of π-Stacking Interactions During Tryptophan Self-Assembling Into Amyloid-Like Structures Using Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A.; Kumar, V.; Garnaik, U.C.; Dada, R.; Qamar, I.; Goel, V.K.; Agarwal, S. Unveiling the Molecular Secrets: A Comprehensive Review of Raman Spectroscopy in Biological Research. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 50049–50063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalapathi, D.; Padmanabhan, S.; Manjithaya, R.; Narayana, C. Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy as a Tool for Distinguishing Extracellular Vesicles under Autophagic Conditions: A Marker for Disease Diagnostics. J Phys Chem B 2020, 124, 10952–10960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleackley, M.R.; Dawson, C.S.; Anderson, M.A. Fungal Extracellular Vesicles with a Focus on Proteomic Analysis. Proteomics 2019 Apr;19(8):e1800232. [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, A.; Ma, Q.; de Assis, L.J.; Leaves, I.; Larcombe, D.E.; Rodriguez Rondon, A. V.; Nev, O.A.; Brown, A.J.P. Anticipatory Stress Responses and Immune Evasion in Fungal Pathogens. Trends Microbiol 2021, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamayo, D.; Muñoz, J.F.; Almeida, A.J.; Puerta, J.D.; Restrepo, Á.; Cuomo, C.A.; McEwen, J.G.; Hernández, O. Paracoccidioides Spp. Catalases and Their Role in Antioxidant Defense against Host Defense Responses. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2017, 100, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Chávez, M.J.; Pérez-García, L.A.; Niño-Vega, G.A.; Mora-Montes, H.M. Fungal Strategies to Evade the Host Immune Recognition. J. Fungi 2017, 3(4), 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S. de M.; Echeverri, C.R.; Mendes-Giannine, M.J.S.; Fusco-Almeida, A.M.; Gonzalez, A. Common Virulence Factors between Histoplasma and Paracoccidioides: Recognition of Hsp60 and Enolase by CR3 and Plasmin Receptors in Host Cells. Curr Res Microb Sci 2024, 100246. [CrossRef]

- Arvizu-Rubio, V.J.; García-Carnero, L.C.; Mora-Montes, H.M. Moonlighting Proteins in Medically Relevant Fungi. PeerJ, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos, C.M.; de Oliveira, H.C.; da Silva, J. de F.; Assato, P.A.; Fusco-Almeida, A.M.; Mendes-Giannini, M.J.S. The Multifaceted Roles of Metabolic Enzymes in the Paracoccidioides Species Complex. Front Microbiol 2014, 5, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, N.; Roncero, C. Chitin Synthesis in Yeast: A Matter of Trafficking. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 12251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, L.; Sorais, F.; Salazar, V.; San-Blas, G.; Niño-Vega, G.A. Expression of Paracoccidioides Brasiliensis CHS3 in a Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Chs3 Null Mutant Demonstrates Its Functionality as a Chitin Synthase Gene. Yeast 2010, 27, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nino-Vega, G.A.; Munro, C.A.; San-Blas, G.; Gooday, G.W.; Gow, N.A.R. Differential Expression of Chitin Synthase Genes during Temperature-Induced Dimorphic Transitions in Paracoccidioides Brasiliensis. Med Mycol 2000, 38, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langemeyer, L.; Borchers, A.C.; Herrmann, E.; Füllbrunn, N.; Han, Y.; Perz, A.; Auffarth, K.; Kümmel, D.; Ungermann, C. A Conserved and Regulated Mechanism Drives Endosomal Rab Transition. Elife 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarnowski, R.; Noll, A.; Chevrette, M.G.; Sanchez, H.; Jones, R.; Anhalt, H.; Fossen, J.; Jaromin, A.; Currie, C.; Nett, J.E.; et al. Coordination of Fungal Biofilm Development by Extracellular Vesicle Cargo. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 6235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitencourt, T.A.; Hatanaka, O.; Pessoni, A.M.; Freitas, M.S.; Trentin, G.; Santos, P.; Rossi, A.; Martinez-Rossi, N.M.; Alves, L.L.; Casadevall, A.; et al. Fungal Extracellular Vesicles Are Involved in Intraspecies Intracellular Communication. mBio 2022; 13, 1, e03272-21. [CrossRef]

- Bielska, E.; Sisquella, M.A.; Aldeieg, M.; Birch, C.; O’Donoghue, E.J.; May, R.C. Pathogen-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Mediate Virulence in the Fatal Human Pathogen Cryptococcus Gattii. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishi, K.; Yoshida, M.; Nishimura, M.; Nishikawa, M.; Nishiyama, M.; Horinouchi, S.; Beppu, T. A leptomycin B resistance gene of Schizosaccharomyces pombe encodes a protein similar to the mammalian P-glycoproteins. Mol. Microbiol. 1992, 6, pp. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipos, G.; Kuchler, K. Fungal ATP-Binding Cassette (ABC) Transporters in Drug Resistance & Detoxification. Curr. Drug Targets 2006, 7, 471–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, S.; Kumar, M.; Gaur, N.A.; Prasad, R. Multiple Roles of ABC Transporters in Yeast. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2021, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.L.; Wang, C.H.T.; Chiang, E.P.I.; Huang, C.C.; Li, W.H. Tryptophan Plays an Important Role in Yeast’s Tolerance to Isobutanol. Biotechnol Biofuels 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Xu, W.; Jiang, W.; Yu, W.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, T.; Yao, J.; Zhou, L.; Zeng, Y.; Li, H.; et al. Regulation of Cellular Metabolism by Protein Lysine Acetylation. Science 2010, 327, 5968 1000–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, C.S.; Garcia-Ceron, D.; Rajapaksha, H.; Faou, P.; Bleackley, M.R.; Anderson, M.A. Protein Markers for Candida Albicans EVs Include Claudin-like Sur7 Family Proteins. J Extracell Vesicles 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gow, N.A.R. Fungal Cell Wall Biogenesis: Structural Complexity, Regulation and Inhibition. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2025, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimrichter, L.; De Souza, M.M.; Del Poeta, M.; Nosanchuk, J.D.; Joffe, L.; Tavares, P.D.M.; Rodrigues, M.L. Extracellular Vesicle-Associated Transitory Cell Wall Components and Their Impact on the Interaction of Fungi with Host Cells. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7:1034. [CrossRef]

- Herkert, P.F.; Amatuzzi, R.F.; Alves, L.R.; Rodrigues, M.L. Extracellular Vesicles as Vehicles for the Delivery of Biologically Active Fungal Molecules. Curr Protein Pept Sci 2019, 20, 1027–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamith-Miranda, D.; Heyman, H.M.; Couvillion, S.P.; Cordero, R.J.B.; Rodrigues, M.L.; Nimrichter, L.; Casadevall, A.; Amatuzzi, R.F.; Alves, L.R.; Nakayasu, E.S.; et al. Comparative Molecular and Immunoregulatory Analysis of Extracellular Vesicles from Candida Albicans and Candida Auris. mSystems 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Bleackley, M.; Chisanga, D.; Gangoda, L.; Fonseka, P.; Liem, M.; Kalra, H.; Al Saffar, H.; Keerthikumar, S.; Ang, C.S.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles Secreted by Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Are Involved in Cell Wall Remodelling. Commun Biol 2019, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, J.; Ramos, C.L.; Frases, S.; Godinho, R.M. da C.; Fonseca, F.L.; Rodrigues, M.L. Lack of Chitin Synthase Genes Impacts Capsular Architecture and Cellular Physiology in Cryptococcus Neoformans. Cell Surface 2018, 2, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, A.F.; de Souza, T.N.; Bonilla, J.J.A.; Zamith-Miranda, D.; Piffer, A.C.; Araujo, G.R.S.; Guimarães, A.J.; Frases, S.; Pereira, A.K.; Fill, T.P.; et al. Traversing the Cell Wall: The Chitinolytic Activity of Histoplasma Capsulatum Extracellular Vesicles Facilitates Their Release. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puccia, R.; Taborda, C.P. The Story of Paracoccidiodes Gp43. Braz J Microbiol. 2023 Apr 13, 54(4), 2543–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, I.; Hernandez, O.; Tamayo, D.; Muñoz, J.F.; Leitão, N.P.; García, A.M.; Restrepo, A.; Puccia, R.; McEwen, J.G. Inhibition of PbGP43 Expression May Suggest That Gp43 Is a Virulence Factor in Paracoccidioides Brasiliensis. PLoS One 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleare, L.G.; Zamith, D.; Heyman, H.M.; Couvillion, S.P.; Nimrichter, L.; Rodrigues, M.L.; Nakayasu, E.S.; Nosanchuk, J.D. Media Matters! Alterations in the Loading and Release of Histoplasma Capsulatum Extracellular Vesicles in Response to Different Nutritional Milieus. Cell Microbiol 2020, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marina, C.L.; Bürgel, P.H.; Agostinho, D.P.; Zamith-Miranda, D.; Las-Casas, L. de O. ; Tavares, A.H.; Nosanchuk, J.D.; Bocca, A.L. Nutritional Conditions Modulate C. neoformans Extracellular Vesicles’ Capacity to Elicit Host Immune Response. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos Baltazar, L.; Nakayasu, E.S.; Sobreira, T.J.P.; Choi, H.; Casadevall, A.; Nimrichter, L.; Nosanchuk, J.D. Antibody Binding Alters the Characteristics and Contents of Extracellular Vesicles Released by Histoplasma Capsulatum. mSphere 2016, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarnowski, R.; Sanchez, H.; Covelli, A.S.; Dominguez, E.; Jaromin, A.; Bernhardt, J.; Mitchell, K.F.; Heiss, C.; Azadi, P.; Mitchell, A.; et al. Candida albicans Biofilm–Induced Vesicles Confer Drug Resistance through Matrix Biogenesis. PLoS Biol 2018, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarnowski, R.; Sanchez, H.; Jaromin, A.; Zarnowska, U.J.; Nett, J.E.; Mitchell, A.P.; Andes, D.; by Joseph Heitman, E. A Common Vesicle Proteome Drives Fungal Biofilm Development. PNAS 2022, 119 (38) e2211424119. [CrossRef]

- Huete-Acevedo, J.; Mas-Bargues, C.; Arnal-Forné, M.; Atencia-Rabadán, S.; Sanz-Ros, J.; Borrás, C. Role of Redox Homeostasis in the Communication Between Brain and Liver Through Extracellular Vesicles. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).